Abstract

Society in Northern Ireland can be characterised as being underpinned by an enduring cultural, religious and political divide between two dominant communities: Catholics and Protestants. The educational system largely reflects and contributes to the reproduction of this separation. Teachers are generally deployed in schools that are consistent with their community identity. Teaching is a very heavily unionised profession, but there has been very little research conducted into the manner in which the community divide has affected the character and composition of the unions that represent teachers in NI. This mixed method investigation addresses that gap in knowledge. It is revealed that although sectoral separation is a significant feature of the profile of union membership, there is considerable consensus with regard to the unions’ stance on the policies that maintain the pattern of teacher deployment. The composition of two unions in particular is ideogrammatic of the community division in education. It is noted however that a combination of economic, political and social factors has contributed to a pragmatic re-configuration of old alliances and rivalries. This realignment has the potential to ensure that teacher unions remain relevant and serve the needs of their members in a post-conflict society.

Introduction

The membership of teaching unions has remained resolutely strong in an era during which trade union membership has declined significantly elsewhere (Topping Citation2017). The atypical density of unionisation amongst teachers throughout the United Kingdom has been explained as being the combined product of distrust in the bodies in charge of education, and teachers’ sense of vulnerability should allegations of misconduct be made against them (Coughlan Citation2015). It has also been recognised that by mobilising the collective power of teachers, unions can challenge educational structures, they can therefore play an important role in supporting the application of professional agency (Quinn and Carl Citation2015).

Campbell (Citation1996) highlighted the importance of teachers electing to join a union that matches their personal values; thereby avoiding potential tension from a moral and ethical mismatch. In the United States, ethnic division has been recorded in the historical patterns of unionisation (Hirsch Citation1990). Nikolai, Eriken, and Niernann (Citation2017) observed that the membership profile of the various unions available to post primary teachers in Germany reflected the sectoral separation within the educational system between Gymnasia (grammar schools), Realschule (comprehensive schools) and Hauptschule (vocational/technical schools). In Belgium the application of consociational political principles has produced an education system within which schools are aligned to either Flemish or Wallon linguistic and cultural traditions – this separation is reflected in the configuration of teacher unions (De Rynck Citation2005).

In Northern Ireland (NI) teachers have a choice of unions but it has been noted that, in a society where ‘people are born into physically and structurally divided communities’, union choice may ‘act as a mirror to that division’ (Mapstone Citation1986, 90).

NI was afflicted by violence from the late sixties until the shortly before the turn of the century: a period known as ‘the Troubles’. The minority Catholic-Irish-Nationalist population challenged state discrimination against them and sought the unification of NI and the Republic of Ireland, whilst the larger, politically dominant, Protestant-British-Unionist community defended NI’s constitutional place within the United Kingdom. The deep, enduring social, cultural, historical, political and religious dimensions of division between these two communities in NI has been observed to be so pervasive that it has been defined as ethnic (Wright Citation1987; Jarrett Citation2017; Morrow Citation2017). Wright (Citation1996) identified that the separation of schools by faith was a key component of the ‘crisis of assimilation’ between the two ethnic communities.

The conflict was ended (but not resolved) by the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The agreement contained commitments to support the development of a more integrated system of education. Nevertheless, more than 20 years later, the pupil-profile of the vast majority of NI schools remains strongly indicative of the Catholic-Protestant separation that defined the conflict. Only 7% of pupils attend consciously cross-community Integrated schools (Department of Education NI Citation2019).

Recent research showed that the community-identity profile of teaching staff employed in these divided school sectors generally reflects the composition of the student body (Milliken, Bates, and Smith Citation2020a). However, nothing has been known about how the membership profile of the various teaching unions reflects this divide or how their perspectives vary on the range of policy issues that act to preserve the enduring community division apparent in teachers’ career paths.

Historical context

The pre-cursors of the trade unions, the professional guilds, emerged in the skilled trades in Belfast in the early nineteenth century. The guilds inevitably reflected the population of a city that was, at the time, predominantly Protestant. That demographic profile changed dramatically in the middle of the century when potato blight precipitated an influx of Catholic workers from the famine-affected countryside to the city. Those already in employment sought to protect themselves against the incursion of new arrivals offering cheap labour. The nascent unions were at the forefront of this quasi-sectarian resistance (Munck Citation1985).

The complex configuration of teaching unions in Northern Ireland can be identified as being rooted in the same historical division. In 1831 a national system of education was established in Ireland to replace an ad-hoc configuration of church-run schools – including those that had been set-up by the Anglican Church, and clandestine ‘hedge schools’ run by Catholic churches and non-conformist Protestant denominations. This system aspired to educate children of different faiths together in schools that would be jointly managed by Catholics and Protestants. The churches effectively resisted this secular model and, by the middle of the nineteenth century, only 4% of schools were under mixed management (Cohen Citation2000).

The advent of these new, connected, educational structures enabled groups of teachers to organise collectively. In August 1868, the first congress of the Irish National Teachers Association (later, Organisation) (INTO) took place. A fundamental rule of INTO at its foundation was that ‘no political or sectarian topics shall be introduced at meetings’; teachers would work together to achieve reforms that reflected their common interest, whilst, as far as possible, keeping clear of those things which were divisive (Puirséil Citation2017, 8).

This policy ambition was prescient. Political and religious tensions between the industrialised, largely pro-British, predominantly Protestant, north-eastern province of Ulster and the three provinces with a significant Catholic majority (Leinster, Connacht and Munster) were galvanising around the devolution of powers from Westminster to Dublin as proposed in the Home Rule Bills. On the whole, Protestants feared the consequences of a political assembly that they believed would be dominated by anti-British Catholics, whilst Catholics generally welcomed the prospect of increased Irish political self-determination.

Teachers were far from exempted from this gathering storm. INTO’s leadership became increasingly aligned with Irish nationalism. Protestant members felt marginalised and established a series of short-lived splinter groups. In July 1919, INTO’s affiliation with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (which was closely connected with the 1916 Easter Rising), their explicit backing of Sinn Féin candidates in the 1918 election and their support for a proposed national strike in opposition to the prospect of military conscription in Ireland finally proved too much. Four northern branches (Coleraine, Lisburn, Londonderry and Newtownards) severed their connections with INTO and the Ulster Teachers’ Union (UTU) was formed (Mapstone Citation1986).

INTO was not the only teaching union to have originated in the nineteenth century. The 1870 Education Act established a framework for the elementary schooling of all children over five years old in England and Wales; in June that same year, the National Union of Elementary Teachers (NUET) was founded with the twin aims of improving teachers’ conditions (principally pay and status) and lobbying for the extension and improvement of the state educational system. In 1888, in response to an expansion in its membership, NUT became the National Union of Teachers (NUT).

DeGruchy (Citation2013) records that, at the start of the twentieth century, women teachers received only 80% of the salaries that were paid to their male equivalents and that, as the wider campaign for feminism and women’s suffrage gained prominence NUT responded to pressure from an internal faction (the National Federation of Women Teachers) and began to champion the cause of equal pay.

After the Great War many of the male teachers who had joined the army returned to find the teaching posts that they had vacated were now filled by women. They formed their own pressure group within the NUT, the National Association of Men Teachers. Internal wrangling and tension between these factions and the NUT leadership ultimately led to the withdrawal of both and the setting up of two new unions: the National Union of Women Teachers (NAWT) in 1920 and the National Association of Schoolmasters (NAS) in 1922. Ironically, given the mutual antagonism and acrimony surrounding their formation, these two unions found common ground over the succeeding decades and eventually amalgamated as National Association of Schoolmasters/Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT) in 1976 – a decision that was, to some extent, a response to the requirements of the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act.

The Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) traced its history in NI through a line that led back to a minute book of the Association of Intermediate and University Teachers (AIUT) dating to 5th September 1898. AIUT was later absorbed into the larger, more powerful Incorporated Association of Assistant Masters, Irish Branch. The union experienced numerous subsequent mergers and name changes throughout the twentieth century. On 1st September 2017, following a protracted period of negotiation and speculation, ATL (which had a UK-wide presence) embarked on an amalgamation with the NUT (who had never previously organised on the island of Ireland) to create the National Education Union (NEU).Footnote1

Teaching unions in Northern Ireland

The division of Ireland in 1922 necessitated the establishing of new educational structures within the northern state. A common management system for schools attended by both Protestant and Catholic pupils was proposed. This was resisted by the churches on both sides – concessions were eventually made which brought the Protestant churches on-board, but the Catholic church and the Grammar schools remained unmoved. Thus, three sectors of education emerged, and the interests of the teachers employed were, on the whole, served by a different union in each:

State Controlled schools – UTU,

Catholic Maintained schools – INTO,

Voluntary (Grammar) schools – the forerunners of ATL/NEU.

This landscape changed again with the creation of secondary modern (post primary) schools in 1947. A fourth union emerged to represent the particular interests of teachers in these schools.

At the start of 1961 NAS had recorded eight members in NI – all of whom were returnees from other parts of the UK where they had joined the Association. The founding meeting of the NI Local Association declared that it would seek members irrespective of religion, political affinity or school type. By the end of 1961 membership had grown to 161 (DeGruchy Citation2013). The 1976 merger between NAS and UWT further increased recruitment. NASUWT grew to become the largest teaching union in NI.

Just as rank-and-file teachers had felt the need to organise, so Head Teachers were moved to set up organisations that reflected and protected their particular professional interests and concerns. The Association of Headmistresses (AHM), founded in England in 1874, was the first of these. The Headmasters’ Association (HMA) followed in 1890. AHM and HMA amalgamated in 1977 to form the Secondary Heads Association (SHA). In January 2006, members voted to change the name to the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL). In NI ASCL attracted members predominantly from voluntary grammar schools.

Primary school heads in England came together in 1897 at a conference held in Nottingham and established the National Federation of Head Teachers’ Associations, that same year also saw the formation of the London Association of Head Teachers; these two bodies came together as the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT). The organisation grew noticeably in the wake of the Second World War and spread throughout GB but only became established in NI in the late 1960s. Although membership of the NAHT was initially reserved for those who held principal posts the Association was expanded to include Deputy Head teachers in 1985 and, in 2000, Assistant Head teachers.

Relations between the unions in NI deteriorated in the late sixties as the community tensions that ultimately led to the Troubles escalated. UTU shared ‘the prevailing Unionist orthodoxy that labour movements were nationalist in sympathy and existed as a threat to the unionist position’, they had the ear of government in Belfast and ‘made no attempt to cut the sectarian divide within which it was spawned’ (Mapstone Citation1986, 100). In marked contrast, INTO was an avowedly all-Ireland union. In NI they represented the concerns of a predominantly Catholic membership who largely shared the aspirations of the Nationalist cause.

By 1969, NAS had attracted both Catholic and Protestant teachers to their fold. As the conflict developed, the union endeavoured to retain unity among this mixed membership by adopting an approach of ‘neither condone nor condemn’ (DeGruchy Citation2013, 247). Meanwhile, the Association of Assistant Masters (an earlier incarnation of ATL/NEU) sought to distance themselves from the overtly political by foregrounding their role as an apolitical professional association.

A number of issues and disputes served to define the divisions between the UTU and INTO, and to test the neutrality of NASUWT and the forerunners of ATL/NEU. These included:

The internment without trail of several Catholic teachers (INTO members).

The occupation of a number of schools in Nationalist areas by the British Army.

The sectarian imbalance in the schools’ inspectorate.

The Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch that all teachers in publicly funded schools were obliged to take (until its removal in 1979)

The Queen’s Jubilee in 1977 and the visit of the Pope to Ireland in 1979 – a school holiday was granted for the former but not the latter (DeGruchy Citation2013; Mapstone Citation1986; Puirséil Citation2017).

The advent of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 did not immediately remove the impact of community tensions on teachers and the teaching unions. In 2002, following Loyalist protests outside a Catholic school, a dissident paramilitary group (Red Hand Defenders) announced that they considered Catholic teachers to be ‘legitimate targets’ and the INTO offices in Belfast were attacked (McDonald and Cusack Citation2004).

Today the NEU, UTU, INTO, NASUWT and NAHT sit together on a joint body that represents the teachers’ side of the Teachers’ Negotiating Committee for salaries terms and conditions the NI Teachers’ Council (NITC). In marked contrast, ASCL functions in NI primarily as a professional association rather than a union and is not represented on the Irish Congress of Trade Unions.

Mainstream education in NI can be characterised as being constructed around five sectors.Footnote2

Controlled schools; primary and post primary schools (including non-selective and Grammar); serving a pupil population of 110,719–9% of whom are Catholic.

Catholic Maintained primary and post primary schools; serving a pupil population of 116,839–95% of whom are Catholic.

Catholic Voluntary Grammar schools; serving a pupil population of 28,414–96% of whom are Catholic.

Non-denominational Voluntary Grammar schools; serving a pupil population of 20,433–14% of whom are Catholic.

Integrated primary and post primary schools; serving a pupil population of 22,926–35% of whom are Catholic (DENI 2019).

Prior to this research there had been limited information available on the profile of union membership across these sectors and there was a lacuna in knowledge with regard to the positions taken by teaching unions with regard to the community-consistent deployment pattern of teachers. The project therefore addressed two research questions:

How does the membership profile of the five unions in the NITC vary between the ethnically separated school sectors in NI?

What positions does each union take on policies and practices that limit teachers’ opportunities to cross between these sectors?

Materials and methods

The philosphical school of pragmatism emerged in USA in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and is principally associated with the work of the educationalist, John Dewey. For pragmatists, arguments between those who believe in the existence of an objective, external, ‘reality’ or proponents of a world view that is subjective, internal and ‘interpretative’ are redundant. They proposed that ‘the only world we have, the only world that really matters … is our common intersubjective world in which we live and act and for which we have a shared responsibility’ (Biesta and Burbules Citation2003, 108).

For pragmatists every situation is unique and reality is forever dynamic and changing; every act affects both our environment and ourselves. Thus matters such as education and industrial relations cannot be studied in isolation – they are processes that only exist because of the interaction between natural and social elements. There is therefore no single way of conducting an investigation that can ensure indisputable knowledge. Denscombe (Citation2010, 148) acknowledged that ‘pragmatism is generally regarded as the philosophical partner of the mixed methods approach’.

The research questions above lend themselves to a mixed method approach. To determine the membership profile of the various unions, a quantitative approach is required. In contrast, in order to gain an insight into the policy positions adopted by each union, qualitative methods are appropriate.

The quantitative element of the research was conducted first. A series of questions relating to participants’ past and present union affiliation were included within a larger project that explored the pattern of teacher deployment across the whole of the NI education system (Milliken, Bates, and Smith Citation2020a). Lauer, McLeod, and Blythe (Citation2013) identified that in order to ensure a representative cohort completing an on-line survey, participants needed: unique email addresses, access to the internet and the capacity to give informed consent. All teachers in NI have email addresses and access to the internet (through an initiative known as C2K) it was also reasonable to assume that teachers have capacity to give informed consent. A survey was therefore developed using Qualtrics software within which bespoke questions relating to union membership were included. A draft was prepared and tested with final year Initial Teacher Education students and refined accordingly.

Although all teachers do have email addresses, concerns about data protection and the possibility of on-line abuse mean that they are not readily available outside the internal networks of individual schools. A link to the survey was emailed to the in-boxes of all mainstream primary and post-primary schools in NI together with information on the research and a request that the link be shared with all teaching staff.

Survey uptake was monitored to identify any emerging bias against key criteria (gender, community background, school sector, location) and, as required, the focus of survey promotion was directed towards ‘missing’ sectors and/or stepped-back in over-subscribed areas. By the time that the survey was closed it had been completed by a total of 1,015 teachers employed in mainstream grant-aided schools in NI i.e. more than 5% of the total number of registered teachers (GTCNI Citation2018). Uptake was within an acceptable range with regard to: location, religious/community balance, gender balance and the proportion of teachers employed in primary, post primary and voluntary grammar schools. Teachers employed in Integrated schools were however disproportionately over-represented (see ). A binomial sample size confidence level calculation determined that the results could be considered to be 95% reliable, within a tolerance range of 3%.

Table 1. Identification of potential bias – profile of survey respondents.

This quantitative data was augmented by data drawn from a series of structured, policy-focused interviews that were conducted with the designated principal officers of each of the five unions i.e. the ATL/NEU Regional Secretary, the INTO Northern Secretary, the NASUWT Regional Secretary, the NAHT Regional President and the UTU General Secretary. Initial interviews were conducted in August 2019. Each of the interviews lasted between 40minutes and one hour, they were all were digitally recorded and fully transcribed. Participant consent was obtained from all participants. The questions posed in the interview schedule were structured to align directly with the research questions (see Appendix 1) – given the relatively small sample further data analysis techniques were not employed.

Both the qualitative interview schedule and the quantitative on-line survey were reviewed by a Research Governance panel. They noted that the questions contained nothing of a contentious nature, that those being surveyed could not be identified from the answers that they provided, that they could not be considered as being ‘vulnerable’ and that all those involved in the research could reasonably be expected to have provided consent for the material they provide to be used in the research – either explicitly by the signing of a consent form or implicitly by completing and submitting their responses to a questionnaire (the purpose of which was clearly stated).

Results

In 2019 the membership figures recorded by the NI Certification Officer for the five teaching unions in NI exceeded the number of teachers registered with the NI General Teaching Council.Footnote3 Each union has a different character and serves (and targets) a different teacher demographic ().

Table 2. Teaching Unions in NI.

Union membership profile: sectoral strength

The membership profiles of INTO and UTU remain strongly reflective of the community divide; this separation is most pronounced in primary schools. ATL/NEU’s members are most frequently employed in grammar schools, particularly, but not exclusively, in non-denominational grammars. All NAHT members will have previously been members of other unions who have chosen to move when they gained promotion. NASUWT has the most evident cross-sectoral reach; they are notably strong among post primary teachers and those employed in Integrated schools ().

Table 3. Teaching Union membership by sector.

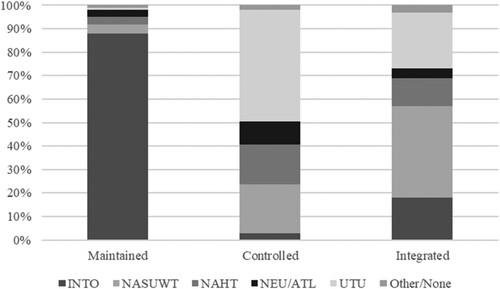

Primary schools ()

Ninety eight percent of primary school teachers are union members. INTO is by far and away the largest union in Maintained primary schools (87%) but accounts for only 3% of teachers in Controlled primaries. The profile of UTU membership presents a mirror image – dominant in Controlled primaries (48%) but with very limited reach in Maintained primary schools (1%). NASUWT membership in primary schools is strongest in the Integrated sector – where it is the largest union (39%) – it also has a significant presence in Controlled primaries (21%) but is much less popular among teachers in Maintained schools (4%). There are ATL/NEU members in all three primary school types with more in Controlled schools (10%) than in Integrated (4%) or Maintained (3%).

NAHT was notably popular among leaders in Controlled (17%) and Integrated (12%) primaries the union had only a very small representation in Maintained schools (3%).

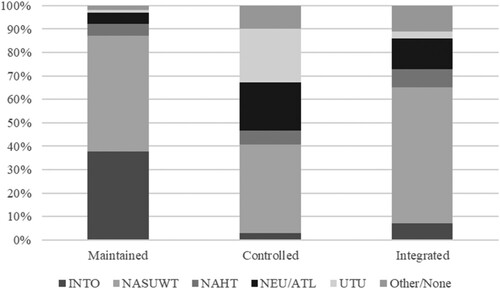

Post primary schools ()

Around 3% of post primary teachers had elected not to join a union, among those who were unionised, NASUWT was the most popular choice across all sectors (Maintained 49%, Integrated 58%, Controlled 38%). As had been observed in primary sectors, UTU membership was strongest in Controlled schools (23%) but negligible among their Maintained counterparts (1%). INTO represented 38% of teachers in Maintained post primaries but only 3% of those on the Controlled side. ATL/NEU was more popular among post primary teachers in all school types than had been observed in primary schools – more so in Controlled schools (21%) than in Integrated (13%) or Maintained (5%).

Membership of the school leadership organisations in Controlled and Integrated schools was relatively evenly split between NAHT and ASCL (6–8%). Five percent of respondents employed in Maintained post primaries were identified as being NAHT members.

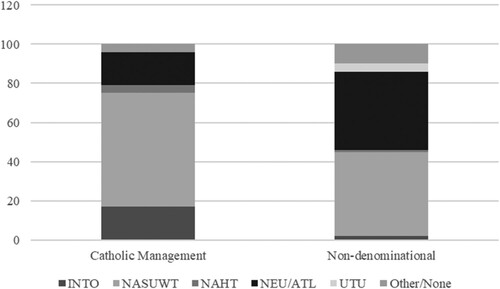

Voluntary grammar schools ()

The dominance of NASUWT in post primary schools was also a feature in voluntary grammars – 58% of those teaching in Catholic grammars and 43% in non-denominational grammars were members. This position was rivalled only by ATL/NEU who were much more strongly represented in non-denominational grammars (40%) than in any other sector; 17% of those teaching in Catholic grammars were also ATL/NEU members. UTU members were found in small numbers in non-denominational grammars (4%), but the union was absent in Catholic grammar schools. INTO had a lower proportion of members in voluntary grammars (17%) than in the other two Catholic school sectors. Only 2% of teachers in non-denominational grammars were INTO members. For school leaders, NAHT had a slightly greater presence in Catholic grammars than non-denominational (4%:1%).

Union positions on teacher separation

Research undertaken by the UNESCO centre at Ulster University (Hansson and Smith Citation2015) drew attention to three distinctive elements of the NI system that contribute to the separation of teachers:

The structure of Teacher Education.

The Certificate in Catholic Education (hereafter referred to as ‘The Certificate’) which is an occupational requirement for those teaching in Catholic Maintained primary schools.

The exception of teachers from the Fair Employment and Treatment Order 1998.

Subsequent fieldwork (Milliken, Bates, and Smith Citation2020b) identified that these factors acted synchronously to build significant barriers that affected teachers’ capacity to consider employment options that involved crossing between the traditional sectors The three elements were therefore applied to frame the questions posed in the interviews with the union officials.

Structure of teacher education

Four institutions currently provide teacher education in NI: Stranmillis University College, St Mary’s University College, Queens University Belfast and Ulster University. Whilst Queens and Ulster are essentially secular institutions, St Mary’s has a Catholic ethos and Stranmillis has been historically associated with providing teachers for Controlled schools (Nelson Citation2010). These latter two institutions supply the majority of primary school teachers. INTO and UTU acknowledged that they had close connections with these respective colleges.

[INTO has] a very strong affiliation as a trade union with one college in particular – St Mary’s.

Of course, most of our [UTU] members will have attended Stranmillis.

We do need to ask a question about the separate nature of them. What effect that has on teachers who then go into schools without having had that proper cross-community mixing and experience?

There was consensus that the current configuration of colleges was in need of rationalisation and could potentially be contributing to a surfeit of teachers entering the career.

[INTO] will accept that we are training too many teachers … We will accept that so many providers in a place the size of the North of Ireland is frankly totally ridiculous.

[NAHT] believe that the profession needs unity in ITE – the colleges shouldn’t be separated.

[NASUWT] are open to a review of teacher training … demand and supply aren’t meeting.

[The ATL/NEU] position is dead simple. There are four providers now – I think it was five a few years ago – it’s too many.

[UTU] are supportive of bringing all teachers together … that would be our ethos at all times, to unite rather than cause divisions.

Option A: A collaborative partnership between the existing ITE institutions

Option B: A Two-Centre Model within a Belfast Institute of Education

Option C: An ITE Federation

Option D: A single Institute of Education

The report was met with protests and political acrimony (Young Citation2015) and was shelved in spite of the panel’s assertion that the status quo ‘is simply not robust enough to deliver the change that is required’ (Sahlberg et al. Citation2014, 2).

Clear waters emerged between the unions at the mention of Sahlberg. Although INTO recognised that a review of teacher education was necessary, they emphasised that it needed to be handled with great sensitivity ‘by someone with more political acumen than the last person who attempted to undertake the task’. Mindful of the sensitivities that the Sahlberg review had raised, UTU avoided taking a formal stance on the issue whilst NASUWT who opposed all of the proposed reforms saw finance as a key driver.

Looking at it from a financial point of view we do have to ask are there better ways of spending money?

A recognised expert led an expert panel … it was based on very thorough international research and international best practice. He proposed 4 options; I think what we would say to the politicians ‘if you can’t make up your minds – there’s two. Pick one. Toss a coin.’

The certificate

Those teachers wishing to teach in primary schools in the Maintained sector are required to demonstrate that they can do so in line with Catholic principles. This takes the form of the Certificate in (Catholic) Religious Education. The Certificate is provided routinely for all students at St Mary’s and to those students endeavouring to become primary school teachers at Ulster – Queen’s only prepares post primary teachers. Prior to September 2019 the Certificate had only been available to students at Stranmillis as a correspondence course. New entrants to the college are now able to complete the award in-house; endorsed by St Mary’s. There is no equivalent occupational requirement for teachers in Controlled schools. ATL/NEU saw this an equality issue.

Having schools of ethos is one thing but does it require 100% of the teachers to be signed up to that? We say ‘No’ … Teachers with a faith certificate have an unfair advantage … [those without it] are deprived of half the opportunities.

The criticism is fairly legitimate in our view.

The Certificate is ‘a load of nonsense’ there should be no discrimination and no barriers to the movement of professionals between sectors.

Welcome its disappearance, because it would open up a whole load of other doors as well.

The Certificate … doesn’t appear to have the currency it once had … There are an increasing number of teachers of faiths other than Catholic, teaching in Catholic schools and particularly in post primary schools. Some of whom don’t have it at all, and nobody is making any big deal about it.

No amount of PR work by the Catholic church or their agents in [the Catholic Council for Maintained Schools] can really deflect the criticism … the Certificate [is] the tool, if you like, to allow the overcoming of the barrier.

It is a minor move but, in our glacial world, it meant that instead of not having a job you had a job.

Teacher exception from fair employment and treatment order (FETO) 1998

The Civil Rights demonstrations that preceded the Troubles demanded legislation to outlaw religious discrimination in the workplace. Fair employment laws were duly introduced – but teachers were specifically excluded from these. It is wholly lawful under current legislation (FETO, 1998) for schools to discriminate between candidates on the grounds of religion when appointing or promoting teachers. This ‘teacher exception’ is also protected by European Law – Article 15(2) of the 1999 Treaty of Amsterdam states:

In order to maintain equality of opportunity in employment for teachers in Northern Ireland and reconcile the historical divisions between the two main religious communities, the provisions on religion and convictions in this [fair employment] Directive shall not apply to the recruitment of teachers in any school in Northern Ireland.

We’ve always been against [it].

I think that the days of the exemption are probably numbered … We would welcome it disappearing.

In March 2019, at their annual NI conference, NASUWT passed a motion calling for the repeal of the exception and committing the union to lobby to achieve that outcome. The NASUWT official was unequivocal:

We are opposed to it … get rid of it.

That is one that [UTU] have not debated for many years … I would imagine if we were to debate it again now … we probably would not support the exemption.

If we are committed to shared education and integrated education and we are going to actively make that work, to develop and flourish, then we are going to have to remove any barrier that is real or perceived.

Discussion

Legislation relating to education in NI has always diverged in some important respects from that passed in Great Britain. The region has developed its own unique pattern of schools and subsequently many of the issues facing teachers in NI are discrete from those encountered by their counterparts elsewhere in the UK and Ireland. It has been proposed that the fragmentation between teaching unions in England and their bickering over trivia is not in the best interests of the teachers that they represent and serve (Beauvallet Citation2014). In NI the potential for this would appear to be even greater; instead of two powerful unions representing around 500,000 teachers (as is the case in England) there are four unions looking after the interests of the just over 20,000 employed in grant aided schools in NI (GTCNI Citation2018). The capacity of four unions to lobby effectively and act collectively in the interests of their members is constrained by their capacity to come together with one voice.

In 2017 and 2018, in response to an on-going pay dispute, the four unions forged an unprecedented alliance to initially take action short of strike action before progressing to co-ordinate a series of half-day and one-day strikes. The banners of all four unions were visible on many picket lines.

Behind the scenes a deeper and closer working relationship had already been developing between three of the unions. Since 2009, UTU and INTO have been working to a common partnership board (INTO & UTU Citation2009). They now recruit together and use a shared application form. In 2011 these two unions forged a pact with NUT and the Educational Institute in Scotland to ‘allow our respective members to benefit from support from the appropriate union should they move between the countries of the UK’ (NUT et al Citation2011). NUT has now merged with ATL to create NEU. Undy (Citation2008) observed such union mergers have the potential to produce a variety of benefits: they can extend unions’ political reach, improve their bargaining power, reduce the potential for damaging inter-union conflict and, thereby, provide better support to members. Whilst UTU and INTO are now firmly under the NEU banner, a formal merger seems highly improbable in the light of the Nationalist/Unionist political schism at the heart of their origins – this is evidenced by the aversion documented here on the part of even teachers who have crossed the traditional divide in schools to transfer between the two unions.

It is not uncommon for teachers to change their union during their career – around a third of teachers who took part in the research indicated that they had done so. Such a change is often precipitated when a teacher moves to a school where a different union is dominant. This research has identified that although INTO represents 63% of all of those teaching in Maintained primary and post primary schools, only 12% of the Protestant teachers in these schools had chosen to join INTO. Similarly, although UTU has a 48% membership reach across all Controlled primaries and 23% in Controlled post primaries; only 9% of the Catholic teachers employed in these sectors had become UTU members. The research also revealed that, where there are UTU members in Maintained schools and INTO members in Controlled schools, this aligns with the location of Protestant and Catholic teachers who have crossed out of their own community to teach on the other side.

Undy (Citation2008) cautioned, that union mergers are destined to fail if they lack support from their rank and file members. Similarly, Williams (Citation2015) noted that union mergers can be particularly difficult when each side has their own specific and distinct political identity. Irrespective of the close strategic alliance evident between UTU and INTO, it appears that their members may be unwilling to transfer their loyalty.

Conclusion

The research presented here has identified commonalities in unions’ approaches to a particular range of policy issues that restrict teachers’ capacity to cross out of career paths that are shaped by community identity – there is potential to investigate where-else such shared purpose exists between apparent rivals. At the outset of this paper a link between union affiliation and professional agency was identified – there may be opportunities for researchers to explore hiw union affiliation may affects the capacity for agency of teachers those who cross between the traditionally divided school types in NI. There has been little or no quantitative research undertaken into the ethnic separation apparent in the membership of teacher unions in other similarly politically contested regions with ethnically divided school systems.

Political stability in NI and the need for economic pragmatism has created a climate within which a degree of détente has been achieved between unions that had previously been in fundamental opposition to one another. It has been identified that two of the four unions (UTU and INTO) are now working with a common partnership board and effectively recruiting as one body. They have both also formally associated themselves with the NEU. Thus, from four of the unions, two blocs have emerged – NASUWT and NEU – just as is the case in England.

It would appear likely that, in spite of an ever-closer working relationship, an amalgamation of UTU and INTO is not on the cards. As has been shown, the community affiliation of their membership remains central to the identity of each. In addition, the history, community-profile of members and INTO’s all-Ireland coverage makes a formal, cross-border merger with a British union (such as the NEU) unthinkable – particularly in the context of UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

The pattern of membership of the four teacher unions is a historical legacy, yet their policy directions indicate movement towards ever greater collaboration. It seems possible that the teacher unions in NI may be moving towards a future less defined and dictated by the parameters of sectarian division; where teachers’ shared interests are represented by unions in a climate of industrial relations where the welfare of teachers is promoted by organisations characterised less by antagonistic opposition and more by co-operative rivalry. Such a future is in the interests of all teachers and not just those who share the same community identity.

Teachers share many common concerns and are affected by many of the same issues irrespective of their community identity or the school sector within which they are employed. Unions are in a stronger position when they act collectively – union disunity can only be in the interests of those who wish to disrupt teacher solidarity.

In the particular case of Northern Ireland, ethnic separation permeates multiple dimensions of education. By acting collectively, teaching unions have the potential to disrupt this pattern of division. By cooperating to challenge the factors that contribute to the separation of teachers into sectors according to their community identity, unions can ensure that pupils in every type of school benefit from being taught by a more diverse, integrated workforce.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to place on record his thanks to the teaching unions that assisted with this research so willingly and openly.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthew Milliken

Dr. Matthew Milliken has extensive experience of working with children and young people in Northern Ireland. He has a professional track record of developing innovative, award-winning educational approaches to support the building of relationships across contested spaces and between divided communities in regions as diverse as Ireland, the Caucasus, Southern Africa, the Basque region, Poland and Germany. His current research interests lie in the policies, practices and perceptions that preserve educational segregation and militate against the establishment of a common system of schooling in Northern Ireland.

Notes

1 ATL retained its identity as a separate ‘section’ within NEU as until 1st January 2019 – all of the research detailed here took place before this date. I have therefore identified all results as relating to the ATL union.

2 A proportion of mainstream pupils attend Irish Medium schools (4272 or 1.3% of the total), or preparatory departments attached to non-denominational grammar schools (1660 or 0.5% of the total) – quantitative research data relating to those teaching in these sectors involved too few teachers to be considered statistically robust.

3 The 2017–18 report by the Certification Officer records that the teacher unions have, in combination, over thirty-two thousand members in NI. The GTCNI indicated that for the same period twenty-seven thousand teachers were registered. The membership of teacher unions therefore exceeds the number of registered teachers in NI by more than five thousand!

4 The ‘petition of concern’ is a veto that allows the political representatives of one community to vote down legislation that could disproportionately favour the other community.

References

- Beauvallet, A. 2014. “English Teachers’ Unions in the Early 21st Century: What Role in a Fragmented World?” Revue LISA/LISA e-journal vol. XII n°8. Accessed April 5, 2019. http://journals.openedition.org/lisa/7108.

- Biesta, G., and N. Burbules. 2003. Pragmatism and Educational Research. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Campbell, E. 1996. “Ethical Implications of Collegial Loyalty as One View of Teacher Professionalism.” Teachers and Teaching 2 (2): 191–208.

- Cohen, M. 2000. “Drifting with Denominationalism: A Situated Examination of Irish National Schools in Nineteenth Century Tullylish, Co. Down.” History of Education Quarterly 40 (1) 49–70.

- Coughlan, S. 2015. “Why is Teaching the Most Unionised Job?” 3/5/2015 BBC Website. Accessed April 4, 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-32116168.

- DeGruchy, N. 2013. History of the NASUWT 1919–2002: The Story of a Battling Minority. Bury St Edmunds: Abramis, Bury St Edmunds.

- Denscombe, M. 2010. The Good Research Guide. 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Department of Education NI. 2019. Statistical Bulletin 2/2019 Annual Enrolments at Schools and in Funded Preschool Education in Northern Ireland, 2018/19. Accessed August 21, 2019. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/education/Revised%2029%20April%202019%20-%20Annual%20enrolments%20at%20schools%20and%20in%20pre-school%20education%20in%20Northern%20Ireland%2C%20201819_0.pdf.

- De Rynck, S. 2005. “Regional Autonomy and Education Policy in Belgium.” Regional & Federal Studies 15 (4): 485–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560500230664.

- GTCNI. 2018. Digest of Statistics. Belfast: General Teaching Council of Northern Ireland. https://www.gtcni.org.uk//publications/uploads/document/DgstStats_2018.pdf (accessed 21 October 2019).

- Hansson, U., and A. Smith. 2015. A Review of Policy Areas Affecting Integration of the Education System in Northern Ireland. Belfast: UNESCO Centre, Ulster University and the Integrated Education Fund. Accessed April 5, 2019. https://www.ief.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Integrated-Education-Scoping-Paper.pdf.

- Hirsch, E. 1990. Urban Revolt: Ethnic Politics in the Nineteenth-century Chicago Labor Movement. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Irish National Teachers Organisation and Ulster Teachers Union. 2009. Joint Flyer. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.into.ie/NI/AboutINTO/NIOrganisationStructure/External/INTO-UTUFederation/INTO_UTU_Flyer.pdf.

- Jarrett, H. 2017. Peace and Ethnic Identity in Northern Ireland; Consociational Power Sharing and Conflict Management. London: Routledge.

- Lauer, C., M. McLeod, and S. Blythe. 2013. “On-line Survey Design and Development: A Janus-Faced Approach.” Written Communication 30 (3): 330–357.

- Mapstone, R. 1986. The Ulster Teachers Union: An Historical Perspective. Coleraine: University of Ulster.

- McDonald, H., and J. Cusack. 2004. UDA – Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror. Dublin: Penguin Ireland.

- Milliken, M., J. Bates, and A. Smith. 2020a. “Education Policies and Teacher Deployment in Northern Ireland: Ethnic Separation, Cultural Encapsulation and Community Cross-Over.” British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (2): 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2019.1666083.

- Milliken, M., J. Bates, and A. Smith. 2020b. “Teaching Across the Divide: Perceived Barriers to the Movement of Teachers Across the Traditional Sectors in Northern Ireland.” British Journal of Educational Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1791796.

- Morrow, D. 2017. “Reconciliation and After in Northern Ireland: The Search for a Political Order in an Ethnically Divided Society.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 23 (1): 98–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2017.1273688.

- Munck, R. 1985. “Class and Religion in Belfast — A Historical Perspective.” Journal of Contemporary History 20 (2): Working-Class and Left-Wing Politics 241–259.

- National Union of Teachers, Education Institute of Scotland, Irish National Teachers Organisation and Ulster Teachers Union. 2011. UK Teacher Unions Working Together. https://www.into.ie/NI/AboutINTO/NIOrganisationStructure/External/INTO-UTU-NEU-EISPartnership/4_UnionPaternership_PressRelease_Sept_2011.pdf (accessed 5 April 2019).

- Nelson, J. 2010. “Religious Segregation and Teacher Education in Northern Ireland.” Research Papers in Education 25 (1): 1–20.

- Nikolai, R., K. Eriken, and D. Niernann. 2017. “Teacher Unionism in Germany: Fragmented Competitors.” In The Comparative Politics of Education Teachers Unions and Education Systems Around the World, edited by T. Moe and S. Wiborg, 114–143. Cambridge,UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Puirséil, N. 2017. Kindling the Flame: 150 Years of the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation. Dublin: Gill Books.

- Quinn, R., and N. M. Carl. 2015. “Teacher Activist Organizations and the Development of Professional Agency.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 745–758.

- Sahlberg, P., P. Broadfoot, J. Coolahan, J. Furlong, and G. Kirk. 2014. Aspiring to Excellence: Final Report of the International Review Panel on the Structure of Initial Teacher Education in Northern Ireland. Belfast: DEL. Accessed April 5, 2019. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/20454/1/aspiring-to-excellence-review-panel-final-report.pdf.

- Topping, A. 2017. “Union Membership Has Plunged to an All-time Low, says DBEIS.” The Guardian, June 1. Accessed August 17, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/jun/01/union-membership-has-plunged-to-an-all-time-low-says-ons.

- Undy, R. 2008. Trade Union Merger Strategies: Purpose, Process, and Performance. Oxford University Press. Oxford

- Williams, S. 2015. “What Would Be the Benefits (And Problems) of a Teacher Union Merger?” Schoolsweek, April 7.

- Wright, F. 1987. Northern Ireland: A Comparative Analysis. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

- Wright, F. 1996. Two Lands on One Soil. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- Young, D. 2015. Fight to Save St Mary’s Teacher Training College Pitches Up at Stormont 28/01/2015 Belfast Telegraph. Accessed April 4, 2019. https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/fight-to-save-st-marys-teacher-training-college-pitches-up-at-stormont-30944011.html.

1

Interview Schedule

Background

Tell me about your Union and its origins.

Teachers in NI have a choice of a number of unions; in what way does your union differ from the rest?

Membership

3. How many members does your union have?

4. From which sector(s) do your members generally come – primary, post primary, controlled, maintained, other?

Policy on the Three Key Elements

5. What is your union’s position on:

The current composition of Initial Teacher Education in NI?

The Certificate requirement for all teachers in Catholic Maintained Schools?

The exception of teachers from protection under the Fair Employment and Treatment Order?

Casework etc.

6. Are you aware of any issues/casework relating to those teachers who have crossed between the traditional sectors?