Abstract

When pupils learn geography they are extending their world view and reshaping it. This paper analyses representations of Africa and African countries and cultures in Irish primary geography textbooks and assesses to what extent these textbook portrayals facilitate or repress multicultural education, specifically critical multicultural education (CMCE). Here, this paper argues that primary geography can and should play a critical role in challenging societal issues of inequality, racism, prejudice and stereotypes, particularly pertaining to perspectives of the ‘Other’. This paper devises a framework for critical multicultural geography education (CMCGE) and applies this to Irish primary geography textbooks. While some textbooks can demonstrate capacity in fostering multiple perspectives, appreciation for diversity, development of critical thinking and enquiry, and making connections; in the main, textbooks present stereotypical, oversimplified accounts of issues, peoples and places which can result in feelings of superiority amongst dominant groups and more entrenched feelings of ‘Otherness’ amongst minority groups.

Introduction

This paper analyses representations of Africa and African countries and cultures in Irish primary geography textbooks and assesses to what extent these textbook portrayals facilitate or repress multicultural education (MCE), specifically critical multicultural education (CMCE). Here, this paper argues that the Irish Primary Geography Curriculum (PGC) can and should play a critical role in challenging societal issues of inequality, racism, prejudice and stereotypes, particularly pertaining to perspectives of ‘the other’ (i.e. minority groups within Irish society and people living in ‘Other’ places), however, this potential is inhibited by an overreliance on textbooks

The paper is divided into three sections, firstly exploring the various tenets and criticisms of MCE, before locating this paper within the CMCE frame. Next, the commonalities and complimentary relationship between geography and CMCE will be examined while a background to Irish primary geography education and the PGC will be presented. Following this, a framework pertaining to CMCE will be established. Finally, this framework will be applied to Irish primary school geography textbooks with regard to how they promote or suppress CMCE in how they portray and advocate the teaching of the ‘Other’. As it was beyond the scope of this research to provide a detailed analysis of the portrayal of all ‘Other’ places in all primary geography textbooks; it was decided to focus on the portrayal of Africa and African countries/cultures across the entire range of textbooks. This decision was also taken due to researcher’s observations of student primary teachers’ misconceptions about Africa in his position as teacher educator. It should also be noted that for the purpose of this study, the term ‘textbooks’ is used to refer to ‘course books’ (Lambert Citation1999) which effectively are the main source of information and guidance for the teaching of geography in primary schools (Irish National Teachers’ Organisation Citation2005).

Multicultural education

There are many approaches or levels to MCE and various experts have attempted to define and group these such as Sleeter and Grant’s (Citation2003) widely cited model identifying five major approaches to MCE; (a) education for the exceptional and culturally different, (b) human relations approaches, (c) single-group studies, (d) multicultural education, and (e) social reconstructionist education; or Jenks et al.’s (Citation2001) three categories of ‘conservative, ‘liberal’ and ‘critical’; or Kincheloe and Steinberg’s (Citation1997) ‘conservative’, liberal’, ‘pluralist’, ‘left essentialist’ and ‘critical’ groupings (see also Banks Citation2004; Nieto Citation2004). While there are differences between these approaches (Gorski Citation2008), this paper argues that general criticisms of MCE apply to each, in that they each include approaches that range from tokenistic, superficial, ‘soft’ MCE which focusses on aspects such as fairs, festivals, food and folktales (the ‘Four F’s’ –Grant and Sleeter, 2003), to more critical, transformative, ‘hard’ MCE approaches which empower pupils to critique and challenge social norms, issues and decisions that benefit one group to the detriment of others (Banks Citation2006; Kincheloe and Steinberg Citation1997; May and Sleeter Citation2010; Nieto Citation2004). This paper advocates for ‘hard’, critical MCE approaches and argues that, in its most complete form, MCE is aimed at attaining educational equity, understanding and respecting ethnic groups and cultural diversity, and recognising and combatting oppression, stereotyping and prejudice (Acar-Ciftci Citation2014; Banks, Citation2006; Sleeter and Grant, Citation2003).

Criticisms of ‘Soft’ MCE

While it is both commendable and important to recognise and celebrate cultural differences, many criticise tokenistic, superficial forms of MCE such as the ‘heroes and holidays’ inconsistent approach to celebrating and acknowledging ethnic diversity while widespread inequalities and prejudices go unchallenged (Banks Citation2007; Gorski Citation2008; Lewis Citation2003; Nieto Citation2010; Leistyna Citation2002; Sleeter and Grant, 2003). Indeed, Moland (Citation2015) warns against this faux version of MCE in which groups are reduced to mere superficial representations of themselves, re-emphasising differences. Pollock (Citation2005) and Nieto (Citation2010) also support this view, purporting that celebrating the ‘Other’ can actually increase a sense of ‘Otherness’, reifying boundaries and reinforcing stereotypes. Strikingly, Banks (Citation2006, 182) refers to how some critics of this form of MCE see it as a tool to keep minority oppressed groups from rebelling against a system that ‘promotes structural inequality and institutionalised racism’. Conversely, those in favour of this ‘soft’ form of MCE argue that acknowledging societal prejudices and inequalities would only serve to exacerbate tensions and hostilities and therefore, an affective approach which focusses on attitudes and feelings towards the ‘Other’ is more appropriate (Sleeter and Grant, Citation2003, 1988; Leistyna Citation2002). Here, ‘Other’ groups are presented by authors in a ‘safe’ manner that emphasises harmonious relations among diverse groups, rendering institutional inequalities and prejudices as invisible ‘leading to the belief that injustices will disappear if people simply learn to get along’ (Berlak and Moyenda Citation2001, 94; Gay Citation2010; Banks Citation2009; Nieto Citation2004, Citation2002; Sleeter and Grant Citation1991). A superficial, ‘tourism’, approach is adopted whereby lessons about other cultures outside the dominant group are often taught through a historical, Eurocentric lens, with the ‘Other’ being reduced to stereotypical symbols and items such as boomerangs, traditional clothing and dances, thus presenting certain cultures as primitive and uncivilised (Acuff Citation2016; Acar-Ciftci Citation2014;; Rasheed Ali and Ancis Citation2005; Leistyna Citation2002; Kincheloe and Steinberg Citation1997). Hopkins-Gillespie (Citation2011) argues that this form of MCE is centred on the idea that ‘the world is at it is’; and thus the existing social order should be maintained whereby all minority groups are encouraged to accept the world view of the majority and assimilate (Banks and Banks Citation2007; Gorski Citation2008).

‘Hard’ critical MCE

Critical MCE (CMCE) is informed by such educational theorists as Paolo Friere, Henry Giroux and Peter McLaren (Leistyna Citation2002). This paper argues that CMCE is crucial if education is to move beyond mere recognition and celebration of cultural difference; beyond what Troyna and Williams (Citation1986, 24) term the ‘Three S’s’ (saris, samosas and steel bands). Here, the argument is that without critical engagement and questioning, sensitivity alone cannot adequately address societal issues of inequality, power relations and prejudice (Acuff Citation2016; Banks Citation2007; Leistyna Citation2002; Nieto Citation2004). Gamage (Citation2008) maintains that CMCE combines multicultural and antiracial theoretical streams. The core goals of CMCE comprise helping pupils become aware of issues and problems associated with injustice and inequality, fostering pupils’ commitment to becoming active local and global citizens wanting to make a difference in the world, and enhancing and developing pupils’ skills for enacting change through the use of communication, listening, critical thinking and enquiry (Nieto Citation2004; Sleeter and Grant, 2006; Rasheed Ali and Ancis Citation2005). The education system’s mirroring of dominant values at the exclusion of ‘Others’ is often referred to as the ‘hidden curriculum’ (Apple Citation1990; Giroux Citation1983 Leistyna Citation2002). Non-critical approaches to MCE maintain this status quo, recreating hierarchies and reifying inequalities and power relations (Berlak and Moyenda Citation2001; Devine Citation2011). Therefore, this paper purports that there is a distinct need for CMCE to be delivered in schools to empower and encourage pupils to ask ‘deeper questions’ concerning equality, power relations and the representation of various groups (Grant and Sleeter, 2006; Jenks, Lee, and Kanpol Citation2001). ‘Our schools should be aiming to produce critical and creative thinkers who are knowledgeable about and sensitive to other cultural perspectives’ (Cummins Citation2010, 14).

Locating CMCE within geography

Wellens et al. (Citation2006) argue that geography is well-placed to play a pivotal role in social transformation, thus lending itself to CMCE. Indeed, Bigelow et al. (Citation1994) outlined key characteristics for education in their vision for social justice and transformation including that it be: grounded in the lives of pupils; critical and linked to real-world problems; multicultural and anti-racist (therefore critical multiculturalism – Gamage Citation2008); participatory and experiential; culturally sensitive; academically rigorous; and concerned with issues beyond the classroom walls. These are all key characteristics of geography education (Catling Citation2005; Catling and Willy, Citation2018; Dolan Citation2020; Martin Citation2008; Pike Citation2016, Citation2011; Roberts Citation2013, Citation2003). Moreover, ‘geographical thinking’, developed through concepts such as space, place, scale, movement and human–environmental interaction, enables pupils to develop critical thinking skills, to analyse and form opinions about real-world problems and to understand and challenge ‘how the world works’ (Machon and Walkington, Citation2000; Young and Lambert Citation2014). Here, geographical perspectives encourage a deeper concept of how phenomena are interrelated, locating private, local actions, in a wider, public, global scale (e.g. climate change is a global process but concurrently plays out locally), thus enabling pupils to identify power relations and to envisage alternatives (Machon Citation1998; Young and Lambert Citation2014). Young and Lambert’s (Citation2014) idea of geography’s ‘powerful disciplinary knowledge’ is informed by CMCE.

This idea of synergy between geography and CMCE is further supported and advocated for by Dolan (Citation2014, Citation2020) who argues that pupils need to understand the relationships which exist between cultures, including differences and similarities. Moreover, Machon and Walkington (Citation2000, 185) state that, together, CMCE and geography can be viewed as ‘a structured values education entitlement … within which the simple transition of values from teacher to learner is avoided and where students are encouraged to think and then behave independently and critically’. Harrington (Citation1998, 46) notes that ‘geography is uniquely placed to challenge stereotypes and help children build up accurate and unbiased images’; a view shared by Picton (Citation2008). However, while geography education does indeed offer significant opportunities for challenging stereotypes; the very notion that there are ‘accurate’ and ‘unbiased images’ wrongly assumes that there is a singular ‘true’ or ‘real’ idea about a place/an ‘authentic place’. Indeed prejudice itself ‘is based on an egocentric judgement that only one way of experiencing the world is the correct way’ (Aboud Citation1988, 132). Instead, it is better to think from multiple perspectives; of multiple places, of places within places, local and global, similar and different, independent and interdependent (Leistyna Citation2002; Picton, 2008).

In light of the above, it is clear that geography and MCE share many common concepts, skills and goals. Of particular note are values and attitudes, and critical thinking and decision-making (see ). Therefore this paper puts forward the concept of CMCE through geography, arguing that geography education is a space in which CMCE can be delivered and developed effectively. The next section will present a CMCE framework with which geography textbook portrayals of the ‘Other’ will be analysed.

Table 1. The values, concepts and skills shared by MCE and Geography (adapted from Machon and Walkington Citation2000).

Developing a CMCE framework for geography

This paper presents CMCE through geography as a method for teaching pupils to be critical; to ask questions of systems, sources and society; to be enquirers and investigators; to recognise and value similarities and differences between peoples; to explore power relations between groups; and to see things from multiple perspectives. ‘The world we know and attempt to understand is shaped by our own individual experiences of places, by what we hear from others, and by the images, maps and text provided by books and the media’ (Roberts, Citation1998, 46). Grant and Sleeter (Citation2009, 260) argue that both teachers and pupils need to be critical of the world around them and the way things are, asking such questions as ‘Is it true? … Who says so? Who benefits most … ? … What alternative ways of looking at a problem can we see?’. This is further supported by Dolan et al. (Citation2014) and Acuff (Citation2016). This notion of critical thinking and enquiry skills being intrinsically linked to CMCE and geography education is widely accepted (Acuff Citation2016; Banks Citation2007, Citation2006; Graves and Murphy Citation2000; Machon and Walkington, 2010; Rasheed Ali and Ancis Citation2005; Young and Lambert Citation2014). This paper puts forward the idea of Critical Multicultural Geography Education (CMCGE) as a means of helping pupils examine the world critically using problem-posing, problem-solving, enquiry and investigative methods which reflect on the issues being covered by exploring the power dichotomies between groups/stakeholders, and by relating these issues to their own lives, experiences, and locations (Grant and Sleeter, 2006; May and Sleeter Citation2010; Nieto Citation2004). Therefore, in developing the framework for CMCGE, the textbooks must make efforts to encourage the pupils to think critically about issues, information, inter-group power relations and places, and to relate the issue/places/people under study back to their own everyday lives and contexts (Acar-Ciftci Citation2016; Machon and Walkington Citation2000; Sleeter and Grant Citation1987). Additionally, CMCGE should encompass developing empathy and respect among pupils for people of different cultures in different places, challenging stereotypes and broadening horizons (Banks Citation2009, 2008; Dolan Citation2020; Lewis Citation2003; Nieto Citation2004; Pike Citation2016; Ozturgut Citation2011).

Synthesising the literature pertaining to both geography education and CMCE, the framework for CMCGE (see ) with which this paper analyses geography textbooks’ portrayals of ‘Africa’ will ask the following questions:

Table 2. Framework for Critical Multicultural Geography Education (CMCGE) (Source: After Author).

CMCE and primary geography Education in Ireland

The Irish PGC is a menu curriculum (NCCA Citation1999a; Citation1999b, Citation2016) which allows teachers the autonomy to select two places; one in Europe and one elsewhere, to study. Here, pupils should be enabled to investigate and explore a broad range of themes and topics pertaining to these places such as valuing and respecting the variety of people and communities that live there, ethnicity, economics, trade, culture, customs and diversities, similarities and differences (NCCA Citation1999a). illustrates the PGC’s layout for teaching about distant places. Furthermore, the teacher guidelines for the PGC emphasise ‘the fostering of a sense of shared global citizenship and an understanding and appreciation of human diversity and interdependence’ (NCCA Citation1999b, 12). Thus it can be said that the overarching aims of the PGC, together with the curriculum content, largely correlate with the broad aims and objectives of CMCE such as developing and promoting cross-cultural understanding, respecting different cultures, recognising and combatting unfairness, oppression and prejudice (Banks Citation2009, 2008; Banks and Banks Citation2001; Grant and Sleeter, 2003; Lewis Citation2003; Nieto Citation1996; Ozturgut Citation2011).

Table 3. Primary Geography Curriculum Strand Unit ‘People and Other Lands’ (NCCA Citation1999a).

Schools are the primary vehicle through which the dominant ‘messages’ pertaining to society are communicated. What is taught, how it is taught and to whom, are heavily politically and sociologically weighted considerations as well as being educational (Apple Citation1979, Citation1986; Lambert Citation2015; Paxton Citation2002; Sleeter Citation2004; Waldron Citation2013). Indeed Devine (Citation2011, 84) argues that ‘both the nature of the message (curriculum) as well as the manner of transmission (pedagogies) has important consequences’. The PGC’s menu format offers vast independence to teachers in selecting content for classrooms. Textbooks are a manifestation of publishers’ interpretations of curricula (Ball Citation1994). Therefore the following section explores the dependency of Irish primary teachers on textbooks in their teaching, thus justifying the textbook analysis contained within this paper.

Textbooks and the delivery of the Irish PGC

Research pertaining to the teaching of primary geography in Ireland is limited and somewhat dated. No large-scale review of the PGC has been undertaken since its introduction in 1999 (Usher Citation2020). In her qualitative research study into primary school pupils’ definitions and descriptions of geography (N = 186), Pike (Citation2006) found that limited pedagogical approaches including rote-learning and textbook-based teaching dominated pupils’ learning experiences pertaining to the current PGC. This is despite the fact that the PGC warns that: ‘textbooks, of their very nature, cannot adequately cover geography and should therefore be regarded as one source among many for the teaching of geography’ (NCCA Citation1999b, 44). Moreover, a survey of Irish primary school teachers (N = 717) by the INTO (Citation2005) found that 88% of respondents used textbooks as a main component in the delivery of the PGC. Here, the content of textbooks, and sequence of said content, was found to be a key determining factor in the planning and preparation of geography lessons (INTO Citation2005), thus surrendering their autonomy in selecting from the menu curriculum to the textbook publishers. Indeed, a large-scale, all-island Irish study (N = 1114) of student primary teachers’ memories of school geography found evidence of traditional, didactic, rote-learning and textbook-dependent approaches dominating the teaching of geography (Dolan et al. Citation2014). Student primary teachers’ memories as pupils comprised spending large amounts of time reading textbooks, listening to teachers read textbooks and rote-learning geographical facts and locations of features (Dolan et al. Citation2014). Waddington (Citation2017) undertook a similar study into student primary teachers’ memories of primary school geography (N = 166) and found rote-learning and textbook, fact-based approaches to dominate. Waldron et al. (Citation2009) allude to a long-established culture of Irish primary teachers relying on textbooks pertaining to the teaching of geography, history and science. Reasons for this reliance on textbooks within Irish primary school classrooms include teachers’ lack of pedagogical knowledge and lack of confidence pertaining to teaching the subject (Eivers, Shiel, and Cheevers Citation2006; NCCA Citation2008; Varley, Murphy, and Veale Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Waldron et al. Citation2009). Banks (Citation2006) also points to a lack of teacher confidence and subsequent avoidance regarding the teaching of controversial issues. Hung (Citation2002) found teachers used textbooks due to the sequential simplistic manner in which they present the content, their perceived encompassment of the facts and skills outlined in the curriculum frameworks, and pressure from peers, administrators and parents to complete the textbooks. Pike (Citation2015, 2006) and Cummins (Citation2010) argue that the use of and reliance upon textbooks in Irish primary geography became widespread practice with the inception of the 1971 primary curriculum; resulting in pupils learning too much content without developing critical thinking and investigative skills. This reliance on textbooks due to lack of teacher confidence regarding the subject was further exacerbated with the launch of the 1999 Primary School Curriculum with only one ‘in-service’ training day being provided to teachers on curriculum content and associated methodologies (Usher, 2019; Pike Citation2015).

Content selection to guide instruction and pedagogy are ‘important value choices’ (Banks Citation2007, 36). As these choices have been abdicated by teachers in favour of textbook publishers with regard to the delivery of the Irish PGC (Cummins Citation2010; INTO Citation2005; Pike Citation2015, Citation2006; Waldron et al. Citation2009), it was decided that a textbook analysis was urgently needed.

Textbooks and CMCE

The dangers of bias and the presentation of stereotypes (both conscious and unconsciously woven) from the part of the authors and publishers who predominantly frame issues in textbooks from a Eurocentric perspective is widely accepted (Acar-Ciftci, Citation2014; Apple Citation2000, Citation1996; Hopkin Citation2011; Marsden Citation2001; Waldron Citation2013). This amounts to ‘soft’ MCE resulting in oversimplification and one-sided narrow view of issues, leading to feelings of superiority from dominant groups’ perspectives, and the alienation of ‘Other’ groups (Bryan Citation2012; Bryan and Bracken Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Bryan and Vavrus Citation2005). Marsden (Citation2001) argues that these stereotypes and biases are an unintentional by-product of the summarisation of key issues to an attainable level for pupils to grasp, at times resorting to ‘convenient caricatures’ to make specific points and generalisations. Others argue that there is a more sinister motive behind these portrayals (Apple, Citation2000; Banks Citation2007, 2001; Waldron Citation2013; Wineburg Citation2001). In any case, both teachers and pupils have been found to view textbooks as comprising accurate and irrefutable facts (Gay Citation2010; Nieto Citation2004; Sleeter and Grant, 1999; Wineburg Citation2001) in which issues pertaining to socioeconomic, political or gender bias are assumed to have been addressed by the authors/publishers (Sleeter Citation2005). Therein lies a critical danger as regards the reifying and reinforcing stereotypes and viewpoints. Simplifying and stereotyping cultures and countries for the sake of making content ‘accessible’ are dangerous because ‘the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story … show a people as one thing, and only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become’ (Adichie Citation2009, 3). Moreover, this notion of irrefutable facts feeds into what Friere (Citation1970) disputes as the ‘banking’ concept of education whereby assessment merely entails pupils regurgitating these ‘facts’ without developing any critical thinking skills. The anonymity surrounding many class textbooks also further adds to their perceived authoritativeness (Paxton Citation2002; Sleeter Citation2004; Waldron Citation2013). Indeed, no author details are provided for any of the textbooks which were analysed for this study. Lee and Catling (Citation2016) found English geography textbook authors to be influenced and constrained by geography national curricula and publishers’ requirements. The same cannot be said for Irish textbook authors. This is exemplified by fact that such activities as rote learning locations of physical features of Ireland are presented in Irish geography textbooks despite the strong renunciation of rote learning in the PGC.

Methodology

Content analysis was the primary research method employed by this study. The purpose of this study is to analyse both written text and visual images which accompany them in order to gather an in-depth understanding of how textbooks represent the lives, values and beliefs of the ‘Other’ – in this case Africa and African cultures. Therefore, while quantitative analysis is critical in terms of the initial capturing of places covered by all primary geography textbooks (see ) and applying the CMCE framework; qualitative content analysis is employed in referring to direct quotations as well as recording the overall impression of textbook accounts, and in the interpretation these data with regards to the relevant literature. All primary geography textbooks available to primary teachers (N = 28) were checked for their inclusion of content related to Africa or African countries, of which seven were found (see ). The content of the seven textbooks pertaining to Africa was systematically analysed once and then repeated for each question in the GMCGE framework.

Table 4. List of places covered by all available Irish Primary Geography textbooks (Source: After Author)

Textbook analysis

The seven textbooks were analysed regarding their portrayal of Africa and African cultures/countries. As can be seen (), all seven textbooks place a large emphasis on issues and hardship in Africa, thus underlining Africa as a mecca for disaster and eternal dependence (Myers Citation2001). The following are results from the textbook analysis; applying the CMCGE framework to the textbooks. These will be discussed in the following sections under each characteristic of the CMCGE framework.

Table 5. Results from applying the CMCGE Framework to the Textbooks (Source: After Author).

Different perspectives

The first question from the CMCGE framework pertains to whether the textbook provides different perspectives of the place and/or issue being presented to the pupils? It is clear from that only two of the seven textbooks presented different perspectives on the place/issue/topic. Overall, a Eurocentric viewpoint (Apple Citation2000, Citation1996; Hopkin Citation2011; Waldron Citation2013) is taken by textbooks, with African countries being identified in accordance with natural resources and the products they produce (see ). Here, Africa is presented as an underdeveloped place, overwhelmed with supposedly internal (Andreotti Citation2006; Bryan and Bracken Citation2011a) issues such as widespread poverty, famine, war, death and ‘poor government’ (Small World: 5th Class pp. 95). No indication is given of instances of extreme wealth which also exists in these places. Here, pupils are informed in a factual manner of the many natural resources in Africa but no explanation is given as to how or why these places are so poor, with such vast array of resources, not to mention the exploitation (past and present) that enshrouds these industries. Even more striking is the positioning of Ireland as the humane, generous giver to a needy and dependent people via ‘missionaries’ and ‘aid agencies’ educating these lesser-able people to be ‘successful farmers … keeping their crops alive’ and ‘sharing’ the ‘skills of reading and writing’ (Small World: 5th Class pp.97) (Bryan and Bracken Citation2011b). No mention is made here to Ireland’s historical links to Africa pre 100 years ago as part of an exploitative and abusive British Empire. There is also a danger here that this portrayal of issues falsely suggests that they are easily solved by charitable donations and volunteering (Bryan and Bracken Citation2011a). Moreover, similarly to Myers (Citation2001), none of the issues are presented from a local African perspective nor are any examples of African initiative in dealing with these issues, thus cementing the notion of Africa as a dependent burden on the rest of the world.

Diversity

The second characteristic from the CMCGE framework concerns whether the textbook acknowledges different cultures and groups within the ‘other’ place? Only one of the seven textbooks was found to do so (see ). The Small World: 3rd Class textbook was found to provide different accounts on life, and growing up in Egypt from Jamilia (girl), Karim (boy) and the Bedoiun nomadic peoples, therefore covering multiple perspectives of Egypt (Aboud Citation1988; Banks Citation2009; Friere Citation1970; Leistyna Citation2002; Picton, 2008; Rasheed Ali and Ancis Citation2005). However, this, along with Window on the World: 3rd Class (see ), also presents a superficial, touristic, Four F’s approach, recognising and celebrating ‘cultural difference’, while realistically portraying these places in a tokenistic manner (Acuff Citation2016, 2013; Bryan Citation2012; Grant and Sleeter, 2003; Kincheloe and Steinberg Citation1997; May, 2009; Moland, 2015; Troyna and Williams Citation1986). Moreover, this lack of diversity and stereotypical representation of an entire country (in cases; Zambia and Ethiopia) is seen in the picture of ‘Rhodi’ cooking on a fire outside a mud-hut with reference to the ‘hot’ weather in Africa, suggesting that this image is reflective of life in all of Africa. Pupils are then ask to look at the pictures and outline how we all ‘help each other’, therefore portraying Africa as a poor, primitive place in need of intervention from ‘Western’ civilisation. Furthermore, the focus on differences in Small World: 2nd Class can be seen as ‘Othering’ those people (Nieto Citation2010; Pollock Citation2005).

Critical thinking and enquiry

The third characteristic of CMCGE framework is whether the textbook encourages enquiry and critical thinking on ‘why things are as they are’ in relation to the issue and or ‘other’ place? Two of the seven textbooks were found to do so to some extent (see ). For instance, Window on the World: 5th Class () encourages pupils to explore the building of the Aswan High Dam on the River Nile from multiple perspectives of the various stakeholders, thus allowing for development of critical thinking and enquiry skills (Picton, 2008; Young and Lambert Citation2014). However, this is an optional drama activity and does not form any part of the formal assessment. Indeed, all seven textbooks focus their assessment on the regurgitation of ‘facts’ and information (Friere Citation1970; Gay Citation2010; Nieto Citation2004; Paxton Citation2002). Many of these facts and assessments focus on what famine is or where/how palm oil is produced, and predominantly the location of key landmarks and so on, but none of them encourage pupils to explore and investigate possible reasons behind issues such as famine, fair trade and war, therefore, subtly indicating to pupils that these aspects are of less importance.

Power relations

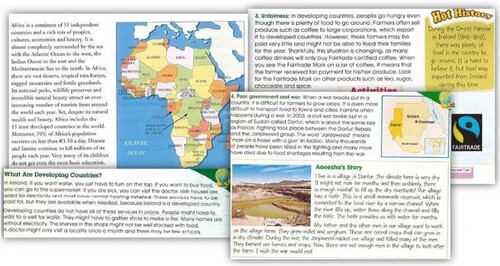

The fourth characteristic of CMCGE concerns if the textbook explores power relations between groups within the ‘other’ place and/or between that place and the pupils’ own locations. While Small World: 5th Class () does appear to explore power relations (the only textbook found to do so) in the sense that it alludes to how many farmers grow coffee for large corporations for very little income at the expense of growing other foods, it, along with all the other textbooks, fails to highlight the true power relations between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ places. As previously alluded to, disasters and human tragedy such as famine, war and poverty are explained as internal problems (Andreotti Citation2006; Bryan and Bracken Citation2011b). Geography Quest: 6th Class () describes Africa as ‘a continent of 53 independent countries’ with much ‘natural wealth’, therefore omitting any mention of its colonial, oppressed past or the devastating impact of global trade and multinational corporations on these places today.

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, ‘secondly.” … Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story. Adichie (Citation2009)

Connections

The fifth characteristic of the CMCGE framework pertains to whether the textbook allows for links to be made between the ‘Other’ cultures/places/issues and the pupils’ locality, experiences and local/national contexts. While Small World: 5th Class does make links to products, fair trade and famine in Africa with a reference to the Great Irish Famine (see ); in general, links made in the textbooks are of aid and charity given by ‘developed’ countries such as Ireland to the ‘underdeveloped’ African countries with no tangible connection between the issues/cultures/places under study and pupils’ own everyday lives and contexts (Acar-Ciftci Citation2016; Machon and Walkington Citation2000; Sleeter and Grant Citation1987). An example of this is Small World: 3rd Class (see ) in which the core focus for assessment on the topic of ‘Egypt’ is very much based ‘facts’ and on the ‘othering’ of Islam, without any mention of Muslims living in Ireland, some of whom could be reading the actual text in primary school classrooms.

Conclusion

This paper has discussed CMCE and argued for the role of geography as a space in which CMCE can be delivered and developed effectively; CMCGE. Here a framework for CMCGE was developed and applied to analyse Irish primary school geography textbooks with regard to how they promote or suppress CMCE in how they portray and advocate the teaching of the ‘Other’ (in this case, Africa). The findings support previous research which found textbooks ineffective as aids in the teaching of CMCE (Bryan Citation2012; Bryan and Bracken Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Bryan and Vavrus Citation2005). While some textbooks were found to have some capacity in fostering multiple perspectives, appreciation for diversity, development of critical thinking and enquiry, and making connections; in the main, they present stereotypical, oversimplified accounts of these issues, peoples and places which can result in feelings of superiority amongst dominant groups and more entrenched feelings of ‘otherness’ amongst minority groups (Acuff Citation2016; Banks Citation2006; Lea, 2001; Lewis Citation2003; Nieto Citation2010; Sleeter and Grant, 2003). Each of the textbooks presented a bleak image of Africa in the context of disaster, famine, poverty, suffering and dependency, and as primitive, uneducated and ‘undeveloped’ with assessment and questioning focused on the regurgitation of oversimplified, stereotypical ‘facts’. Little to no focus is placed on positive stories from Africa, instead positioning Africa as homogenous entity and as the ‘epicentre of the world’s human crises: AIDs, overpopulation, desertification, refugees … malnutrition, etc. (Myers Citation2001, 529). The lack of positive representations of Africa and presentations of those places from African people’s own perspectives results in a one-dimensional, narrow, Eurocentric account of an entire continent; suggesting that these representations are indicative of life there – that there is only one ‘accurate’ idea about what Africa is like (Aboud Citation1988; Leistyna Citation2002; Myers Citation2001; Picton, 2008). Furthermore, none of the textbooks refer to Africa’s colonial past or the fact that many cultures and groups transcend national borders. Indeed Leistyna (Citation2002, 2) warns against ‘reducing the idea of culture to national origin’ as this results in a myriad of cultural identities within a country being stereotyped as one homogenous group, as is the case in this study.

Overall, in an Irish context, these findings are concerning. A 2009 study on the experiences of migrant pupils in the Irish education system found Irish pupils to know very little about other cultures, especially non-European countries. Here, migrant pupils highlighted their Irish peers as having stereotypical understandings of their countries of origin (Smyth et al. Citation2009). The findings of this textbook analysis correlate to this. The portrayals of the ‘Other’ within these textbooks are both superficial, ‘soft’ reflections of the Irish PGC and CMCE, focussing on dependence of the ‘Other’ rather than interdependence, thus reinforcing the ‘us’/‘them’ dichotomy.

Alas, while this paper has shown geography textbooks to be ineffective in the delivery of CMCE, little is known pertaining to how in fact teachers use these textbooks in classrooms. Graves and Murphy (Citation2000, 229) maintain that, while ‘there is no such thing as a perfect textbook’, it is up to the teacher ‘to make his own selection from the material offered. He must use it, according to his conception of the lesson; and he must supplement it, as he thinks necessary’. Therefore, a key recommendation from this study is to undertake research on teachers’ use of textbooks as we know teachers are highly dependent on textbooks in their delivery of the PGC, however how teachers use these textbooks and whether they critically scrutinise the content with their pupils etc. (as advocated by Marsden Citation2001) is unknown. Ball (Citation1994) argues textbooks and curriculum are one and the same. This paper contends that these primary geography textbooks are a ‘soft’, conservative and somewhat inaccurate interpretations of the PGC and thus strongly recommends that; the new PGC (currently being proposed – NCCA Citation2016) be more explicit in advocating for CMCGE within its content objectives and aims, and; as teachers are so dependent on textbooks in the selection, planning and delivery of content that it is incumbent on textbook publishers to promote opportunities for CMCE in their publications.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joe Usher

Dr Joe Usher is a Lecturer in Primary Geography Education at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. He has a wide range of research interests including; using the locality in the teaching of primary geography, using digital resources in the teaching of primary geography, enquiry-based teaching and learning in primary geography, outdoor learning, children’s rights and participation in local decision-making, and the general development of educational resources for primary geography education.

References

- Aboud, F. 1988. Children and Prejudice. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Acar-Ciftci, Y. 2014. “A Conceptual Framework Regarding the Multicultural Education Competencies of Teachers.” Journal of Education 30 (1): 1–14.

- Acar-Ciftci, Y. 2016. “Critical Multicultural Education Competencies Scale: A Scale Development Study.” Journal of Education and Learning 5 (3): 51–63.

- Acuff, J. B. 2016. “Being a Critical Multicultural Pedagogue in the Art Education Classroom.” Critical Studies in Education 1: 1–19.

- Adichie, C.N. [TED Talks]. 2009. The Danger of a Single Story -Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg.

- Andreotti, V. 2006. “Soft Versus Critical Global Citizenship Education.” Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review 3 (1): 83–98.

- Apple, M. W. 1979. Ideology and the Curriculum. London: Routledge.

- Apple, M. W. 1986. Teachers and Texts: A Political Economy of Class and Gender Relations in Education. London: Routledge.

- Apple, M. 1990. Ideology and Curriculum. New York: Routledge.

- Apple, M. W. 1996. Cultural Politics and Education. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

- Apple, M. 2000. Official Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. 1994. Education Reform: A Critical and Post-structural Approach. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Banks, J. A. 2004. “Historical Development: Dimensions and Practice.” In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, edited by J. A. Banks, 3–30. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Banks, J. A. 2006. Race, Culture and Education. New York: Routledge.

- Banks, J. A. 2007. Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

- Banks, J. A. 2009. Teaching Strategies for Ethnic Studies. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Banks, J. A., and C. A. M. Banks. 2001. Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives. 4th ed. London: Wiley.

- Banks, J. A., and C. A. M. Banks. 2007. Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives. 6th ed. London: Wiley.

- Berlak, A., and S. Moyenda. 2001. Taking it Personally. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bigelow, B., L. Christensen, S. Karp, B. Miner, and B. Peterson. 1994. Creating Classrooms for Equity and Social Justice: Rethinking our Classrooms. Milwaukee: Rethinking Schools.

- Bryan, A. 2012. “‘You’ve got to Teach People That Racism is Wrong and Then They Won’t be Racist’: Curricular Representations and Young People’s Understandings of ‘Race’ and Racism.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 44 (5): 599–629.

- Bryan, A., and M. Bracken. 2011a. Learning to Read the World. Dublin: Irish Aid.

- Bryan, A., and M. Bracken. 2011b. “They Think the Book is Right and I am Wrong’: Intercultural Education and the Positioning of Ethnic Minority Students in the Formal and Informal Curriculum.” In The Changing Faces of Ireland: Exploring the Lives of Immigrant and Ethnic Minority Children, edited by M. Darmody, N. Tyrrell, and S. Song, 121–186. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Bryan, A., and F. Vavrus. 2005. “The Promise and Peril of Education: The Teaching of In/tolerance in an Era of Globalisation.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 3 (2): 183–202.

- Catling, S. 2005. “Seeking Younger Children’s ‘Voices’ in Geographical Education Research.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 14 (4): 297–304.

- Catling, S., and Willy T. 2020. Understanding and Teaching Primary Geography. London: Sage.

- Cummins, M. 2010. Eleven Years On: A Case Study of Geography Practices and Perspectives within an Irish Primary School. Unpublished M.Ed thesis. Dublin City University.

- Devine, D. 2011. Immigration and Schooling in the Republic of Ireland: Making a Difference? Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Dolan, A. 2014. You, Me and Diversity: Picturebooks for Teaching Development and Intercultural Education. London: Trentham Books and IOE Press.

- Dolan, A. 2020. Powerful Primary Geography: A Toolkit for 21st Century Learning. New York: Routledge.

- Dolan, A. M., F. Waldron, S. Pike, and R. Greenwood. 2014. “Student Teachers’ Reflections on Prior Experiences of Learning Geography.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (4): 314–330.

- Eivers, E., G. Shiel, and C. Cheevers. 2006. Implementing the Revised Junior Certificate Syllabus: What Teachers Said. Dublin: Department of Education and Science.

- Friere, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Gamage, S. 2008. “‘Current Thinking About Critical Multicultural and Critical Race Theory in Education.” In Interrogating Common Sense: Teaching for Social Justice, edited by I. Soliman, 11–131. Sydney: Pearson Education.

- Gay, G. 2010. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research and Practice. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

- Giroux, H. 1983. Critical Theory and Educational Practice. Victoria: Deakin University Press.

- Gorski, P. C. 2008. “‘What We’re Teaching Teachers: An Analysis of Multicultural Teacher Education Courses’.” International Journal of Research and Studies 25 (2): 309–318.

- Grant, C. A., and C. E. Sleeter. 2009. Turning on Learning: Five Approaches to Multicultural Teaching Plans for Race, Class, Gender, and Disability. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

- Graves, N., and B. Murphy. 2000. “‘Research Into Geography Textbooks’.” In Reflective Practice in Geography Teaching, edited by A. Kent, 108–146. London: Paul Chapman.

- Harrington, V. 1998. “‘Teaching About Distant Places’.” In Primary Sources: Research Findings in Primary Geography, edited by S. Scoffham, 46–49. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Hopkins-Gillespie. 2011. “Curriculum and Schooling: Multiculturalism, Critical Multiculturalism and Critical Pedagogy.” The South Shore Journal 4 (1): 1–10.

- Hung, J. L. 2002. “Types of and Reasons for Teacher Modification of Textbook Materials, and a Comparison Between the Prescribed and Modified Methods of Teaching Democratic Citizenship Education Based on Student Performance” (Doctoral Dissertation). Seattle: University of Washington.

- Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO). 2005. The Primary School Curriculum: INTO Survey. Dublin: INTO.

- Jenks, C., J. O. Lee, and B. Kanpol. 2001. “Approaches to Multicultural Education in Pre-service Teacher Education: Philosophical Frameworks and Models for Teaching.” The Urban Review 33 (2): 87–105.

- Kincheloe, J., and S. Steinberg. 1997. Changing Multiculturalism. London: Open University Press.

- Lambert, D. 1999. “Exploring the Use of Textbooks in Key Stage 3 Geography Classrooms: a Small-scale Study.” The Curriculum Journal 10 (1): 85–105.

- Lambert, D. 2015. ‘Teachers as Leaders: Who are the Children We Teach and What Shall We Teach Them?’ Astana: Keynote address at NIS Conference, 2015.

- Lee, J., and S. Catling. 2016. “Some Perceptions of English Geography Textbook Authors on Writing Textbooks.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 25 (1): 50–67.

- Leistyna, P. 2002. Defining and Designing Multiculturalism. Albany: University of New York Press.

- Lewis, A. 2003. Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the Colour Line in Classrooms and Communities. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Machon, P. 1998. “Citizenship and Geography Education.” Teaching Geography 23 (3): 115–117.

- Machon, P., and H. Walkington. 2000. “‘Citizenship: the Role of Geography?’.” In Reflective Practice in Geography Teaching, edited by A. Kent, 53–105. London: SAGE.

- Marsden, W. E. 2001. The School Textbook: Geography, History and Social Studies. London: Routledge.

- Martin, F. 2008. “Ethnogeography: Towards Liberatory Geography Education.” Children's Geographies 6 (4): 437–450.

- May, S., and C. E. Sleeter. 2010. Critical Multiculturalism: Theory and Praxis. New York: Routledge.

- Moland, N. A. 2020. “Can multiculuralism be exported: dilemmas of diversity on Nigeria's Sesame Square.” Comparative Education Review 59 (1): 1–23.

- Myers, G. A. 2001. “Introductory Human Geography Textbook Representations of Africa.” The Professional Geographer 53 (4): 522–532.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 1999a. Primary Geography Curriculum. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 1999b. Primary School Curriculum: Geography –Teacher Guidelines. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2008. Science in the Primary School (Final Report). Dublin: NCCA.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2016. Proposals for Structure and Time Allocation in a Redeveloped Primary Curriculum. Dublin: NCCA.

- Nieto, S. 1996. Affirming Diversity: The Socio-political Context of Multicultural Education. New York: Longman.

- Nieto, S. 2002. Language, Colour and Teaching: Critical Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- Nieto, S. 2004. Affirming Diversity: The Socio-political Context of Multicultural Education. 4th ed. New York: Allyn and Bacon.

- Nieto, S. 2010. Language, Colour and Teaching: Critical Perspectives. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Ozturgut, O. 2011. “Understanding Multicultural Education.” Current Issues in Education 14 (2): 1–9.

- Paxton, R. J. 2002. “The Influence of Author Visibility on High School Students Solving a Historical Problem.” Cognition and Instruction 20 (2): 197–248.

- Picton, O. J. 2020. “Teaching and Learning about Distant Places: conceptualising diversity.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 17 (3): 227–249.

- Pike, S. 2006. “Irish Primary School Children's Definitions of ‘Geography’.” Irish Educational Studies 25 (1): 75–91.

- Pike, S. 2011. ““If you Went Out It Would Stick”: Irish Children’s Learning in Their Local Environments.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 20 (2): 139–159.

- Pike, S. 2015. “Primary Geography in the Republic of Ireland: Practices, Issues and Possible Futures.” Review of International Geographical Education Online 5 (2): 185–198.

- Pike, S. 2016. Learning Primary Geography: Ideas and Inspirations from Classrooms. London: Routledge.

- Pollock, M. 2005. “‘Race Bending: Mixed Youth Practicing Strategic Racialization in California.” In Youthscapes: The Popular, National and Global, edited by S. Maira and E. Soep, 249–298. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Rasheed Ali, S., and J. R. Ancis. 2005. “‘Multicultural Education and Critical Pedagogy Approaches’.” In Teaching and Social Justice: Integrating Multicultural and Feminist Theories in the Classroom, edited by C. E. Enns and A. Sinacore, 69–84. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Roberts, M. 1998. “The nature of geographical enquiry at Key Stage 3.” Teaching Geography 23 (4): 164–167.

- Roberts, M. 2003. Geography Through Enquiry: Approaches to Teaching and Learning in the Secondary School. Sheffield: The Geographical Association.

- Roberts, M. 2013. Learning Through Enquiry. Sheffield: The Geographical Association.

- Sleeter, C. E. 2004. “Critical Multicultural Curriculum and Standards Movement.” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 3 (2): 122–138.

- Sleeter, C. E. 2005. Un-standardizing Curriculum: Multicultural Education in the Standards-based Classroom. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

- Sleeter, C., and Grant C. 2003. Making choices for multicultural education: five approaches to race, class and gender. 4th edition. Hoboken: Wiley and Sons.

- Sleeter, C. E., and C. A. Grant. 1987. “An Analysis of Multicultural Education in the United States.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (4): 421–445.

- Sleeter, C. E., and C. A. Grant. 1991. “‘Race, Class, Gender and Disability in Current Textbooks’.” In The Politics of Textbooks, edited by M. W. Apple and L. K. Christian-Smith, 78–110. New York: Routledge.

- Smyth, E., M. Darmody, F. McGinnity, and D. Byrne. 2009. Adapting to Diversity: Irish Schools and Newcomer Students. Dublin: ESRI.

- Troyna, B., and J. Williams. 1986. Racism Education and the State: The Racialization of Education Policy. London: Croom Helm.

- Usher, J. 2020. “Is Geography Lost? Curriculum Policy Analysis: Finding a Place for Geography Within a Changing Primary School Curriculum in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 39 (4): 411–437.

- Varley, J., C. Murphy, and O. Veale. 2008a. Science in Primary Schools Phase 1. Dublin: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA).

- Varley, J., C. Murphy, and O. Veale. 2008b. Science in Primary Schools Phase 2. Dublin: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA).

- Waddington, S. 2017. “‘What do People Remember and What do Teachers Assume About Primary Geography in Ireland.” In Reflections on Primary Geography, edited by S. Catling, 167–170. London: CMP Book Printing.

- Waldron, F. 2013. “The Power to End History? Defining the Past Through History Textbooks.” Inis 39 (1): 54–59.

- Waldron, F., S. Pike, R. Greenwood, C. Murphy, G. O'Connor, A. Dolan, and K. Kerr. 2009. Becoming a Teacher: Primary Student Teachers as Learners and Teachers of History, Geography and Science- An All-Ireland Study. A Report for SCoTENS.

- Wellens, J., A. Berardi, B. Chalkley, B. Chambers, R. Healey, J. Monk, and J. Vender. 2006. “Teaching Geography for Social Transformation.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30 (1): 117–131.

- Wineburg, S. 2001. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Young, M., and D. Lambert. 2014. Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice. London: Bloomsbury.