Abstract

This paper presents a unique school-based programme that harnesses the benefits of both trauma-informed practice (TIP) and outdoor environments to support children’s social and emotional wellbeing throughout the pandemic and beyond. In the opening sections of the paper, we discuss the extant literature and conceptual underpinning of TIP and outdoor learning, and highlight why both are needed, particularly in the context of Covid-19. We then chart the design of a six-week outdoor trauma-informed programme, devised to support children’s emotional regulation and overall sense of wellbeing. The programme activities are aligned to the Northern Ireland curriculum, and are tailored to make use of the outdoor spaces available in the first author’s place of work – a primary school in South Belfast. We conclude the paper by highlighting the importance of trauma-informed curriculum and pedagogical innovations and note future directions for trauma-informed schools. Whilst there are many generic guidelines on trauma-informed care in schools, this paper makes a distinct contribution to the field; firstly by demonstrating how teachers can use their craft – teaching – as a component of TIP; and secondly by infusing trauma-informed principles within outdoor learning environments.

Context and rationale

Covid-19 has dramatically altered the everyday lives of children, with many experiencing isolation, worry, loneliness, and uncertainty about the future (Burke and Dempsey Citation2020; O’Toole and Simovska Citationin press; Walsh Citation2020). Escalating cases of domestic violence along with rises in alcohol consumption within family homes, has placed children and young people at a higher risk of exposure to violence and abuse (Save the Children Citation2020), whilst school closures have not only denied children of their right to education, but also their access to a place of safety, security, and connection (United Nations Citation2020). It is increasingly evident that the pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities, increasing the economic, social, and psychological pressures on children.

Trauma-informed practice (TIP) has been advocated in many countries to support teachers to respond to children who have been exposed to abuse, trauma, and other adverse experiences (Maynard et al. Citation2019). TIP is a strengths-based approach that is based on knowledge and understanding of how trauma affects people's lives. It integrates an awareness of the pervasive biological, psychological, and social consequences of trauma with the ultimate aim of ameliorating, rather than exacerbating, their effects (SAMHSA Citation2014). Many academics and advocacy groups in Ireland and elsewhere have argued that the pandemic has created a new urgency for TIP in schools (Alcohol Action Ireland Citation2020; NCTSN Citation2020).

The pandemic has also created many practical challenges for schools in lowering the risk of virus transmission and/or ensuring social distancing. This has prompted many schools to consider the opportunities afforded by outdoor environments (Simovska Citation2020; Childhood by Nature Citation2020). In addition to providing a safer space in the context of Covid-19, outdoor environments have many benefits for children’s learning, health, and development, including supporting emotional regulation and overall sense of wellbeing (IFSA Citation2017; Louv Citation2010; Lovell and Roe Citation2009). Against this backdrop, we present a unique school-based programme that harnesses the benefits of both TIP and the outdoor environment to support children’s social and emotional wellbeing throughout this time of crisis.

Theoretical perspectives

The design of the programme was informed by research and theory in trauma studies and outdoor learning and pedagogy. Recent decades have seen advances in our understanding of trauma and its impact on mind, body, and behaviour. When children grow up in relationally impoverished environments, and when they experience danger or threat, the body’s stress response system initiates a cascade of biological changes, responsible for the fight, flight, or freeze (Porges Citation2009). Prolonged activation of the stress response system impacts brain development and takes a toll on the body, potentially developing into chronic illness over time (Maté Citation2003; van der Kolk Citation2014). In the aftermath of overwhelmingly stressful events, children are often flooded with distressing sensations, images, or implicit body memories. They are likely to have a narrow window of tolerance (Siegel Citation1999), meaning that they have a lower threshold for high-intensity emotion, which can cause them to become hypo-aroused (dissociated, withdrawn, or shut down) or hyper-aroused (distraught, panicked, or enraged). Both states interfere with children’s ability to autonomously regulate their emotions and reduce their capacity to concentrate, process, and store information. There are obvious implications for school performance and relationships (Perry and Szalavitz Citation2017).

In school, children who have experienced trauma may appear angry and disruptive, spaced-out and inattentive, and/or confused and disengaged. These responses to trauma may seem bizarre or incomprehensible to those who do not understand how trauma and adversity impact mind, body, and behaviour. Children’s outbursts and/or withdrawals often lead to them getting into trouble, as staff misinterpret these behaviours as wilful defiance, a lack of respect, or laziness (O’Toole Citationin press). The reality is that these trauma responses are rooted in deep emotional pain.

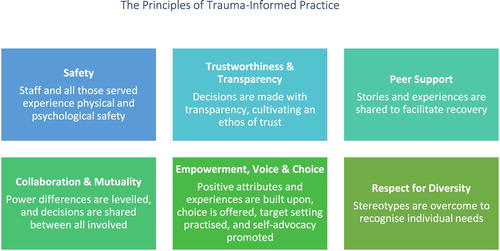

It is important therefore, that schools are aware of trauma and how it impacts children’s emotions and behavioural responses. TIP is a strengths-based approach, guided by the six principles shown in . Central to trauma-informed work is the establishment of nurturing environments and positive relationships between teachers and pupils, which offer ‘more compassionate, open-hearted encounters’ and pave the way for healing and growth (O’Toole Citation2019, 17). Indeed, successive studies show that the single most important factor in healing from trauma is positive relationships with significant others (Treisman Citation2017).

Figure 1. The principles of trauma-informed practice. Adapted from SAMHSA (Citation2014) and Harris and Fallot (Citation2001).

Trauma-informed educators recognise the need to move away from punitive responses to dysregulated behaviour. Instead, they acknowledge the need to help children learn and reflect by intervening in a simple sequence; firstly, they support children to regulate, or to calm the body’s fight/flight/freeze response, making them feel soothed and safe; then they relate, or connect by validating children’s feelings; and lastly they reason, offering reasurrance but negotiating a more positive way forward (Perry Citation2019). Through these attuned and responsive interactions, children’s window of tolerance (or optimal zone of arousal) can be expanded to enable them to not only manage, but thrive in everyday life (Siegel Citation1999; Treisman Citation2018).

In addition to the power of relationships, it is increasingly recognised that interacting with natural spaces helps to soothe or regulate the body’s stress response system. Research demonstrates that the calming sounds of nature and even outdoor silence can lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which calms the body's fight/flight/freeze response (Strauss Citation2018). Connection with the natural world supports children’s sense of security and trust and is associated with higher levels of self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-expression (Bento and Costa Citation2018; Berger Citation2008; Richardson and Murray Citation2017), all of which is crucial for children dealing with the aftermath of stress and trauma.

It has been suggested that outdoor environments support both learning and emotional regulation through the dynamic interaction between the child, others, and space (Waite and Pratt Citation2017). In relation to the child, the parts of the brain responsible for self-regulation are developed through the physical movement of outdoor learning (White Citation2014), whilst emotional development is supported through risk-taking, impulse control, and behavioural self-management (Thomas and Harding Citation2011; McNair Citation2012). With respect to others, outdoor learning supports the development of empathy, cooperation, problem-solving, and leadership skills (McArdle, Harrison, and Harrison Citation2013), which enables children to contribute to the wellbeing of their peers. Finally, the space, full of open-ended elements and multiple loose parts, encourages effective child-initiated interactions (Waters and Maynard Citation2010; Nicholson Citation1971) and offers a safe environment for children to navigate their challenges (Passy Citation2014).

Of course, the use of outdoor environments is also beneficial in the context of Covid-19 mitigation efforts, as they are associated with a lower risk of virus transmission and enable effective social distancing (Qian Citation2020). This further strengthens the calls for increased use of outdoor learning in schools (Simovska Citation2020; Krarup Citation2020). All of this points to the benefits that could accrue from introducing trauma-informed, outdoor curriculum and pedagogy innovations. In the next section we outline the design and development of one such innovation.

Programme design and development

We designed an outdoor socio-emotional learning programme infused with trauma-informed principles and values. This programme was designed to facilitate the participation of a small group of around ten children, aged between four to six years old. It runs for six-weeks, with a planning session prior to commencement and each session lasting between 70 and 90 min.

The principles of TIP guided programme content and implementation (see ). A sense of safety is fostered through working in a small group, with lessons following a predictable structure within familiar outdoor grounds; trustworthiness and transparency through positive self-regulation modelling and informing the participants about what to expect during the lessons; peer support through employing activities which invite the children to assist each other; collaboration and mutuality through allowing the participants to contribute to the programme design; empowerment, voice and choice by respecting the children’s views and acting upon them; and respect for diversity through responsive facilitation which follows the children’s lead. The infusion of these principles and values into the curriculum and pedagogy sets the foundation from which positive relationships and emotional regulation can be fostered.

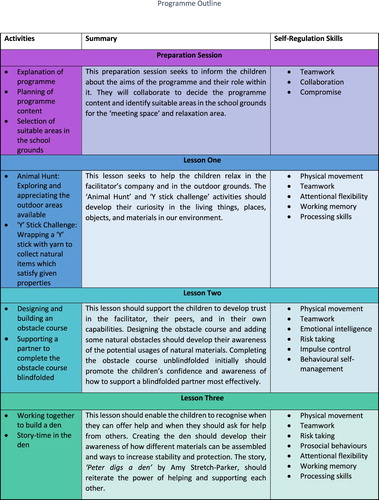

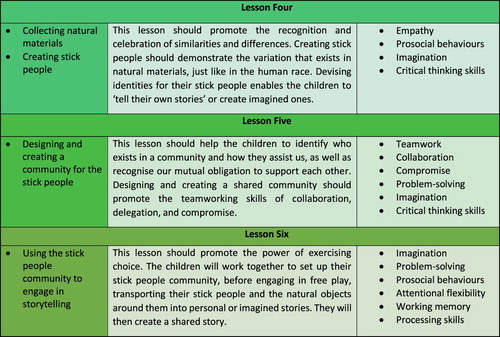

The programme content was designed to enrich the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural domains of self-regulation. provides a summary of programme activities and the self-regulation skills that were targeted. Full lesson plans and accompanying resources can be acquired by contacting the first author. The activities were chosen to encourage children to employ individual strengths to overcome challenges, as well as support others through peer co-regulation (Perry Citation2020). By engaging in programme activities, children are empowered to identify, compliment, and learn from their own and each other’s skills and talents. A range of high and low energy activities were selected to promote inclusive and open-ended play (Tovey Citation2007) and enhance physical, social, imaginative, and creative development (Waters and Maynard Citation2010). Adventure activities, such as the den building, identify nature as ‘an obstacle to be overcome’ and promote communication skills, joint decision-making, and teamwork (Berger Citation2008, 324). Creative opportunities, such as the ‘stick people’ activities, address nature more symbolically as ‘a strength-giving partner’ and support creativity and individuality (Berger Citation2008, 324). Story-making activities using the stick people community enable the exploration of imaginary or real-life situations and allow children to embody and act out roles (Kroll Citation2017). The relaxation activities at the end of every lesson demonstrate the sense of safety and calm that can be found in nature (Berger Citation2008).

Figure 2. Programme outline. Note: full lesson plans and accompanying resources can be obtained by contacting the first author.

The programme content is designed to align with various aspects of the Northern Ireland Curriculum (CCEA Citation2007a), especially the areas of Personal Development and Mutual Understanding (CCEA Citation2007b), the World Around Us (CCEA Citation2007c), and Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities (CCEA Citation2015). However, whilst identifying a range of activities and cross-curricular links was deemed important, it should be noted that the programme is designed with flexibility in mind. In line with trauma-informed principles, a key role of the facilitator is to be attuned and responsive to children’s developing interests and ideas. Programme content should be co-constructed by children and facilitator during the planning session and post-lesson reflections. Thus, a priority is given to flexibility and adjustments throughout the curriculum enactment.

Another important feature of the programme is its tailoring to the local context. This programme was designed with the first author’s particular school context in mind. It takes account of the children’s social and cultural background, as well as the school’s available resources and facilities. For instance, the first author’s school has a large natural outdoor space, and the programme harnessed this strength. Other schools would need to be creative in adapting the programme to suit their own contexts.

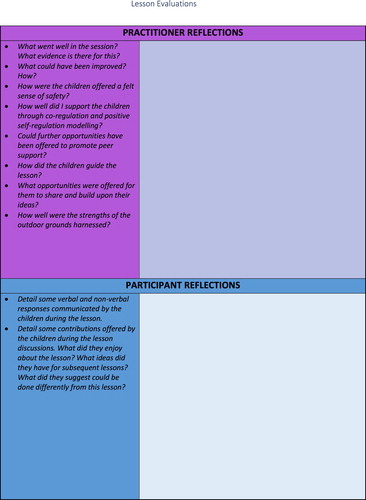

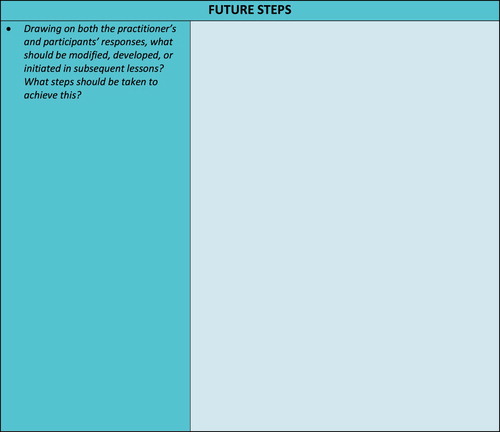

To ensure on-going improvement and development, it would be important to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the programme. This could be approached from different angles depending on your role as either researcher or practitioner. If the programme was part of a research project, a realist approach to evaluation might be appropriate (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997). Here the focus would be on identifying and evaluating both situational processes and causal factors that affect children’s outcomes and experiences. For the educational practitioner, the programme could be evaluated through on-going observations and critical reflections with peers, whilst also drawing on evaluative discussions with the participants themselves (already a key aspect of the lessons). Evaluations should avoid simply trying to quantify behavioural changes and instead appraise more broadly, focusing on how well the principles of TIP have been enacted. displays a lesson evaluation template which could be used at the end of each session. Whilst avoiding a narrow ‘checklist’ format, it does offer questions relating to the principles of TIP, to act as thinking prompts. It also aims to reflect and draw on the participants’ responses when outlining future steps.

Figure 3. Lesson evaluation template.

Discussion

The increased levels of adversity experienced by children since the pandemic began have heightened the impetus for TIP in schools (Alcohol Action Ireland Citation2020; NCTSN Citation2020). Internationally, there are many examples of trauma-informed guidelines and resources. However, Thomas and colleagues (Citation2019) noted a dearth of empirical work describing how teachers use their craft – teaching – as a component of trauma-informed care. Similarly, O’Toole (Citationin press) has highlighted that existing trauma-informed guidelines are limited in that they do not typically extend to supporting teachers in identifying ways to respond through their ongoing pedagogical practices or curriculum innovations. This paper responds to these concerns by presenting an example of how trauma-responsiveness can be infused into the cut and trust of teacher’s everyday practice.

There has been criticism of a potential over-reliance on generic trauma-informed guidelines; with fears that they may be little more than a ‘tick box’ exercise. Some authors have highlighted the need to support educators in developing a rich contextual understanding of their students’ lives and a deep appreciation of the various strengths and challenges that exist in the particular communities they serve (Alvarez Citation2017). A strength of this programme is that it is specifically tailored to the lead author’s place of work and is responsive to the local context. Whilst educators would indeed benefit from being offered pragmatic examples of how to realise TIP in school life, they themselves must be prepared to think creatively and strategically about how to adapt generic trauma-informed guidelines to suit their own unique contexts.

Whilst this programme provides a helpful example of how TIP can be infused into curricula and pedagogy, it should be noted that trauma sensitivity and responsiveness require a whole school approach. Treisman (Citation2017) highlights that embedding trauma responsiveness within schools means attending to all aspects of school life, including organisational dynamics, leadership, the social milieu, physical environments, school structures, policies and procedures, and so on. Future directions for this work would be to expand on this programme and explore ways to infuse TIP at a whole-school level.

In conclusion, embedding the principles of TIP in school life is imperative, not only to alleviate the consequences of increased levels of adversity and trauma experienced because of the pandemic, but also to contribute to improving the challenging life circumstances that many will continue to find themselves in. However, schools must be supported in making TIP a reality. To do this, they require high-quality Continuous Professional Development opportunities and resources which highlight not only the theory of TIP, but also offer tools and practical examples of how to realise it in action.

Ethical considerations

Initiating new curriculum and pedagogical innovations can present ethical challenges. Indeed, working with your own students risks evoking pressure to conform and please. Planning the sessions collaboratively with the participants minimises the power differential. The guidance of the principles of TIP fosters a supportive and inclusive ethos and limits the possibility of children who struggle with self-regulation feeling inadequate or judged. Effective support is given in the lead up to activities and participants’ emerging needs are monitored and responded to. They are reminded regularly that they can opt out of activities at any stage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michaela Mulholland

Michaela Mulholland is a primary school teacher working in South Belfast. She recently completed a Master of Education degree in Maynooth University. She has a particular interest in play, outdoor learning, wellbeing and language and literacy.

Catriona O'Toole

Dr. Catriona O’Toole is a chartered psychologist and assistant professor in Maynooth University Department of Education. Her research focuses on wellbeing and trauma-informed practice in schools and community settings.

References

- Alcohol Action Ireland. 2020. “AAI | MHI – Call for Investment in Trauma-Informed Services to Support Covid-19 Recovery.” [Online] Accessed 27 November 2020. https://alcoholireland.ie/aai-mhi-call-investment-trauma-informed-services-support-covid-19-recovery/.

- Alvarez, A. 2017. ““Seeing Their Eyes in the Rearview Mirror”: Identifying and Responding to Students’ Challenging Experiences.” Equity & Excellence in Education 50 (1): 53–67.

- Bento, G., and J. A. Costa. 2018. “Outdoor Play as a Mean to Achieve Educational Goals – a Case Study in a Portuguese day-Care Group.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 18 (4): 289–302.

- Berger, R. 2008. “Going on a Journey: A Case Study of Nature Therapy with Children with a Learning Difficulty.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 13 (4): 315–326.

- Burke, J., and M. Dempsey. 2020. Covid-19 Practice in Primary Schools in Ireland Report. Maynooth: Maynooth University.

- CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). 2007a. The Northern Ireland Curriculum: Primary. Belfast: Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment.

- CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). 2007b. “Statutory Requirements for Personal Development and Mutual Understanding at Foundation Stage.” [Online] Accessed 14 May 2020. https://ccea.org.uk/downloads/docs/ccea-asset/Curriculum/Statutory%20Requirements%20for%20Personal%20Development%20and%20Mutual%20Understanding%20at%20Foundation%20Level.pdf.

- CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). 2007c. “Statutory Requirements for The World Around Us at Foundation Stage.” [Online] Accessed 14 May 2020. https://ccea.org.uk/downloads/docs/ccea-asset/Curriculum/Statutory%20Requirements%20for%20the%20World%20Around%20Us%20at%20Foundation%20Stage.pdf.

- CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). 2015. “Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities in the Foundation Stage.” [Online]. Accessed 14 May 2020. http://www.nicurriculum.org.uk/curriculum_microsite/TSPC/doc/getting_started/foundation/FS_thinking_skills_poster.pdf.

- Childhood by Nature. 2020. “Resources for Outdoor Learning During COVID-19.” [Online] Accessed 10 January 2021. https://childhoodbynature.com/resources-for-outdoor-learning-during-covid-19/.

- Harris, M., and R. D. Fallot. 2001. Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems: New Directions for Mental Health Services. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- IFSA (Irish Forest School Association). 2017. “What is Forest School?” [Online]. Accessed 21 November 2019. https://irishforestschoolassociation.ie/whatisforestschool.

- Krarup, J. 2020. “Outdoor learning: Changing the Way we View Learning Spaces During COVID-19.” [Online]. Accessed 15 February 2021. https://www.zeneducate.com/resources/schools/outdoor-learning-changing-the-way-we-view-classrooms-during-covid-19.

- Kroll, L. R. 2017. “Early Childhood Curriculum Development: The Role of Play in Building Self-Regulatory Capacity in Young Children.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (5-6): 854–868.

- Louv, R. 2010. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. London: Atlantic Books.

- Lovell, R., and J. Roe. 2009. “Physical and Mental Health Benefits of Participation in Forest School.” Countryside Recreation Network Volume 17: 20–23.

- Maté, G. 2003. When the Body Says no: The Costs of Hidden Stress. London: Penguin.

- Maynard, B. R., A. Farina, N. A. Dell, and M. S. Kelly. 2019. “Effects of Trauma-Informed Approaches in Schools: A Systematic Review.” Campbell Systematic Reviews. [Online] Accessed 27 November 2020. https://schoolsocialwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Campbell-Maynard_et_al-2019-Campbell_Systematic_Reviews.pdf

- McArdle, K., T. Harrison, and D. Harrison. 2013. “Does a Nurturing Approach That Uses an Outdoor Play Environment Build Resilience in Children from a Challenging Background?” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 13 (3): 238–254.

- McNair, L. 2012. “Offering Children First-Hand Experiences Through Forest School: Relating to and Learning About Nature.” In Early Childhood Practice: Froebel Today, edited by T. Bruce, 57–68. London: SAGE Publications.

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN]. 2020. “Trauma-Informed School Strategies during COVID-19.” [Online] Accessed 27 November 2020. https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/resource-guide/trauma_informed_school_strategies_during_covid-19.pdf.

- Nicholson, S. 1971. “How not to Cheat Children: The Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape Architecture 62 (1): 30–34.

- O’Toole, C. 2019. “Time to Teach the Politics of Mental Health: Implications of the Power Threat Meaning Framework for Teacher Education.” Clinical Psychology Forum 313: 15–19.

- O’Toole, C. in press. “Childhood Adversity and Education: Integrating Trauma-Informed Practice Within School Wellbeing and Health Promotion Frameworks.” In Wellbeing and Schooling - Cross Cultural and Cross Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by R. McLellan, C. Faucher, and V. Simovska. Springer.

- O’Toole, C., and V. Simovska. in press. “All in the Same Storm, but not in the Same Boat! The Impact of COVID-19 on School Wellbeing.” Health Education. Special Issue

- Passy, R. 2014. “School Gardens: Teaching and Learning Outside the Front Door.” Education 3-13 42 (1): 23–38.

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 1997. “An Introduction to Scientific Realist Evaluation.” In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook, edited by E. Chelimsky and W. R. Shadish, 405–418. London: Sage Publications.

- Perry, B. 2019. “The Three R's: Reaching The Learning Brain.” [Online] Accessed 23 April 2020. https://beaconhouse.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/The-Three-Rs.pdf.

- Perry, B. 2020. “Respect Your Client & Their Story with Bruce Perry, MD, PhD [Interview] 2020”.

- Perry, B., and M. Szalavitz. 2017. The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog: What Traumatized Children Can Teach Us About Loss, Love, and Healing. New York: Basic Books.

- Porges, S. W. 2009. “The Polyvagal Theory: new Insights Into Adaptive Reactions of the Autonomic Nervous System.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 76 (Suppl 2): S86.

- Qian, H., T. Miao, L. Liu, X. Zheng, D. Luo, and Y. Li 2020. “Indoor Transmission of SARS-CoV-2.” [Online] Accessed 10 June 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.04.20053058v1.full.pdf.

- Richardson, T., and J. Murray. 2017. “Are Young Children’s Utterances Affected by Characteristics of Their Learning Environments? A Multiple Case Study.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (3-4): 457–468.

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2014. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Save the Children. 2020. “Children at Risk of Lasting Psychological Distress from Coronavirus Lockdown.” [Online]. Accessed 26 February 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/children-risk-lasting-psychological-distress-coronavirus-lockdown-save-children.

- Siegel, D. J. 1999. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape who we are. New York: The Guildford Press.

- Simovska, V. 2020. “Children's Wellbeing when Schools are Locked Down.” [Online]. Accessed 27 November 2020. https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/sites/default/files/editor/wellbeing-and-covid19-she-110620.pdf.

- Strauss, J. 2018. “Sour Mood Getting You Down? Get Back to Nature: Research Suggests that Mood Disorders can be Lifted by Spending More Time Outdoors.” [Online]. Accessed 26 February 2021.

- Thomas, M. S., S. Crosby, and J. Vanderhaar. 2019. “Trauma-Informed Practices in Schools Across Two Decades: An Interdisciplinary Review of Research.” Review of Research in Education 43: 422–452.

- Thomas, F., and S. Harding. 2011. “The Role of Play: Play Outdoors as the Medium and Mechanism for Well-Being, Learning and Development.” In Outdoor Provision in the Early Years, edited by J. White, 12–22. London: SAGE publications.

- Tovey, H. 2007. Playing Outdoors. Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenges. Maidenhead: Open University Press, McGrawHill Education.

- Treisman, K. 2017. Working with Relational and Developmental Trauma in Children and Adolescents. London: Routledge.

- Treisman, K. 2018. “Good relationships are the Key to Healing Trauma, TEDx Talks.” [Online]. Accessed 23 April 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTsPdMqVwBg.

- United Nations. 2020. “UN Supporting ‘trapped’ Domestic Violence Victims During COVID-19 Pandemic.” [Online]. Accessed 21 November 2020. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/un-supporting-%E2%80%98trapped%E2%80%99-domestic-violence-victims-during-covid-19-pandemic.

- van der Kolk, B. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Waite, S., and N. Pratt. 2017. “Theoretical Perspectives on Learning Outside the Classroom- Relationships Between Learning and Place.” In Children Learning Outside the Classroom: From Birth to Eleven, edited by S. Waite, 7–22. London: SAGE Publications.

- Walsh, G., N. Purdy, J. Dunn, S. Jones, J. Harris, and M. Ballentine. 2020. Homeschooling in Northern Ireland During the COVID-19 Crisis: The Experiences of Parents and Carers. Belfast: Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement/Stranmillis University College.

- Waters, J., and T. Maynard. 2010. “What's so Interesting Outside? A Study of Child-Initiated Interaction with Teachers in the Natural Outdoor Environment.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 18 (4): 473–483.

- White, J. 2014. Playing and Learning Outdoors: Making Provision for High Quality Experiences in the Outdoor Environment with Children 3-7. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge.