Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic is an unanticipated event that has exposed human fragility in an interconnected and interdependent world. While impacts are of a global magnitude, they have been felt at the most local of levels. Across the world pupils’ daily lives and experiences have been directly impacted by government-imposed measures and restrictions taken to address the pandemic. Existing research on the teaching of primary geography in Ireland, although both dated and limited, indicates the prevalence of didactic, textbook-based methods involving rote-learning. This points to a policy-practice gap whereby teaching methods are not aligned with those advocated by the curriculum. Primary teachers and student primary teachers have been found to hold knowledge-based encyclopaedic images of geography, failing to recognise the subject’s relevance to the real-world lived experiences of pupils. This paper frames the Covid-19 as an authentic learning experience that can form the foundation for effective geography education. Pupils learn best and are more motivated to engage in a problem or issue that affects them or that they are connected to. By investigating Covid-19 through geography in the primary classroom, this paper argues that both pupils and teachers can recognise the relevance of geography to their lives and the wider world.

Introduction

Since the first months of 2020, Covid-19 has affected the life of millions of people around the world. It has long been recognised that epidemics and pandemics exhibit several geographical dimensions. Firstly, the spatial aspect of COVID-19 is communicated through numerous national and international maps accompanied with statistical tracing. Secondly, Covid-19 highlights social and economic inequalities in different geographical regions. For instance, the number of ventilators per capita illustrates the level of critical care infrastructure across countries. Thirdly, the science of Covid-19 has geographical aspects, including the practice of contact tracing, tracking, testing, vaccine trials and development. Fourthly, Covid-19 raises important environmental questions. Ultimately, this zoonotic disease arose as a direct result of human activity generating extensive environmental degradation. Finally, the scale of disruptive consequences has sent shock waves around the world, comparable in scale to other major geopolitical events such as World War 1 and 11. Hence, the pandemic demands responses that are informed by the role of physical and biological processes including climate change, previous viruses and the impacts of political decision making. While the pandemic provides many opportunities for teaching place and space in primary schools, geography itself is an inherent part of the Covid-19 story. The need for a robust geographical education has never been greater.

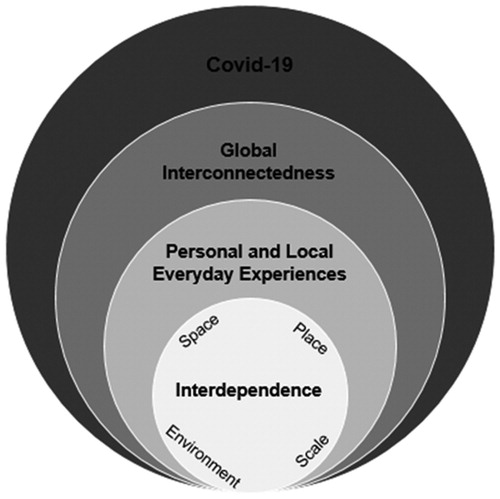

This conceptual paper frames Covid-19 as an authentic learning experience that can form the foundation for effective geography teaching and learning. Covid-19 illustrates the interdependence and interconnectedness of many geographical concepts including space, place, scale and the environment, which are composite building blocks of the discipline of geography, at both local and global scales (see ).

This paper argues that geographical education ought to be reimagined in response to contemporary challenges including Covid-19. Geographical learning in the twenty-first century requires an ability to read, understand and apply conceptual and spatial information associated with unfolding local, national and global analysis of events such as Covid-19. By investigating Covid-19 through geography in the primary classroom, this paper argues that both pupils and teachers can recognise the relevance of geography to their lives and the wider world. Through geography, pupils can develop the capacity to live in, and contribute to, a rapidly changing world as engaged and informed citizens.

The next section will present what is known pertaining to current teaching practices in Irish primary geography education. Following this, the links between children’s lived experiences throughout the pandemic and their personal everyday geographies will be explored before presenting Covid19 as a current event and authentic context for problem-based learning. Finally, some recent practices of teaching about Covid19 through primary geography will be presented, reimagining geography education by integrating school geography with pupils’ everyday lives through mapping activities, outdoor learning and futures thinking.

Current practices in primary geography education

There is limited research pertaining to primary teachers’ practices in geography education in Ireland. Indeed, the development of a new primary curriculum is currently underway (NCCA Citation1999) and geography remains one of the few subjects for which no review has been carried out since its enactment in 1999. Pike (Citation2006) found that limited pedagogical approaches including rote-learning and textbook-based teaching dominated pupils’ learning experiences pertaining to the current primary geography curriculum. Moreover, a 2005 Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO) survey found that 88% of primary teachers used textbooks as the core component in the planning and teaching of the Social, Environmental and Scientific Education element of the primary curriculum (i.e. history, geography and science) (INTO Citation2005). Indeed, Dolan et al.’s (Citation2014) large-scale, all-island Irish study of student primary teachers’ memories of school geography found evidence of didactic, rote-learning and textbook-dependent approaches dominating the teaching of geography. Notably, in a similar study, Waddington (Citation2017) found rote-learning and textbook approach to dominate student primary teachers’ memories of primary school geography.

In relation to pupils’ preferred methods of learning geography, Pike (Citation2011) found that while Irish pupils prefer experiential child-centred methods and building on their own experiences and everyday knowledge, such methods are rarely experienced. These findings are further supported by Dolan et al. (Citation2014) who found that overall, as pupils, student primary teachers valued active, experiential and collaborative methods while they held negative memories of didactic textbook-dominated lessons and rote-learning. Strikingly, Dolan et al. (Citation2014, 319) also found only 5% of student primary teachers in Ireland ‘saw geography as useful and relevant to everyday life’. This disconnection with geography is problematic, particularly because those who do not perceive the relevance of the subject will be unlikely to teach it in a way that is relevant to pupils (Catling and Martin Citation2011).

Text books continue to be used as a predominant teaching resource in both primary and post-primary classroom (Krause, Béneker, and van Tartwijk Citation2021; Lee et al. Citation2021). From existing research in Ireland, although limited and somewhat dated, the teaching methods employed in geography lessons in Irish primary schools are generally lead by didactic textbook-based methods involving rote-learning with teachers and pupils failing to see its relevance to everyday life outside the classroom. This is all despite the fact that the primary geography curriculum advocates strongly for experiential learning methods connected to everyday experiences and specifically warns educators against an over-reliance on textbooks and the use of rote-learning (NCCA Citation1999). However, it should be noted that the research is incomprehensive, as it is somewhat dated, or are based on student primary teachers’ memories, or general teaching across subjects.

Overall, the PGC is viewed as progressive and ambitious in recognising and promoting the children as active participants in constructing their own learning; connecting new content to their own experiences and what they already know, developing empathy with others, and developing senses of space and place of their locality and the wider world (Pike Citation2015).

Personal everyday geographies: covid-19

Exploring real-world, everyday issues and problems better informs pupils than if learning is just treated as something related only to school (Roth Citation2014). This is certainly the case with the Covid-19 pandemic which has had a direct impact on everyone’s lives both globally and locally, to varying degrees (see ). Usher (Citation2020) argues that geography needs to be seen as relevant by pupils, teachers, policymakers and the public at large, where meaningful geography education with tangible links to the real world can be delivered. The extraordinary circumstances surrounding Covid-19 provide an opportunity to illustrate the importance and relevance of geography education. This section argues for the acknowledgement and use of pupils’ everyday lived experiences and knowledge in the teaching of primary geography. It outlines how public measures have had direct impacts on pupils’ lived experiences and communities before arguing that addressing these experiences and knowledge in primary geography not only highlights the relevance of geography, but also encourages more hands-on, experiential teaching methods.

The notion that pupils’ own experiences and personal prior knowledge and understandings should be acknowledged and developed upon in geography education goes back as far as Bale (Citation1987:, 58) who referred to pupils’ ‘personal geographies’ or ‘private geographies’ and how personal experiences and connections form the basis for rich geographical knowledge, understanding and skills. Martin (Citation2006, Citation2008) refers to the importance of ‘routine geography’ or ‘everyday geography’ in that geography pertains to the context of our daily lives and decisions about what we do, how we do it, and why we do it, our understandings of the world, and of our feelings and views on its happenings. It is a ‘living subject’ (Dolan Citation2020; Citation2016). Covid-19 has brought drastic changes physically, socially, economically and politically at both local and global scales. Thus, integrating geography education with pupils’ everyday lives and experiences pertaining to Covid-19 and examining its impacts in other areas of the globe, enables pupils to draw tangible connections to the learning content and the subject as a whole (see ).

Pupils do not enter schooling without a geographical background or without geographical skills, knowledge and understanding that are in and from their lived geographies (Martin Citation2008). This concept is illustrated clearly through the Covid-19 pandemic which was, and still is, a lived experience, shared by pupils and teachers alike throughout Ireland and across the globe. Multiple lockdowns and travel restrictions had a direct impacts on pupils’ social, and emotional well-being, further exacerbated by socio-economic conditions including access to broadband. Most pupils temporarily lost access to schools, community centres, streets, playgrounds and other social spaces that are central to their lives and identities. The geographical dimensions of the pandemic were both explicit and implicit. Children’s everyday geographies have relevance, hence it is important to provide a space for acknowledging that many aspects of day-to-day living have been affected by Covid-19.

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of a geographical perspective. McKendrick and Hammond (Citation2021) uphold that geography education can contribute to helping pupils understand and recover from the impacts and experiences endured during the Covid-19 crisis. Covid-19 provides a unique and salient opportunity for geography education to reconsider the relationships between pupils’ everyday lives and their education.

Addressing the pandemic through geography not only highlights the importance and relevance of geography to the real-world and pupils’ everyday experiences, but also encourages teachers to employ more hands-on, collaborative and experiential-based teaching methods which pupils prefer, rather than didactic, textbook-dominated passive methods. Indeed, Degirmenci and Ilter (Citation2017) found geography textbooks to be insufficient in their inclusion of real-world events and issues.

Covid-19: Current events and problem-based learning

There is enormous potential to examine Covid-19 in school geography through problem-based learning. As demonstrated in the framework (), Covid-19 illustrates the interdependence and interconnectedness of many geographical concepts including place, space, environment, and scale. Here, the study of Covid-19, led through geography, could lend itself to integration with other subject areas such as literacy and numeracy as well as the examination of previous pandemics in history education such as the 1918 flu outbreak. Catling (Citation2010) maintains that geography is the ultimate integrator subject because of geography’s real-life, everyday nature. Moreover, Bale (Citation1987, 133) referred to how authentic contexts highlight the ‘artificiality of subject boundaries … where disciplinary boundaries serve to obscure, rather than encourage, the awareness of reality’. Prior knowledge and experience are important in problem-based learning whereby the pupil is able to connect the problem or event to their own experiences (Weiss Citation2017). As a shared and lived experience, Covid-19 is particularly conducive to problem-based learning in that it is an authentic and lived context in which every pupil is an expert in their own unique way and to which every pupil has personal connections. Usher (Citation2019b) found pupils value learning about events and issues discussed both in the media and at home in the local community. Over the past year, Covid-19 has permeated every facet of human life including community engagement, politics, economics, trade, sport and recreation, travel and tourism, and media at both local and global levels. Experiential learning activities including group work and discussions concerning the nature of the Covid-19 crisis, its causes, the various responses and solutions from social, economic and health perspectives are appropriate methods for geography education. The interdependent links between our local and globalised worlds have never been more clearly illustrated than throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. Geography education provides an awareness of societal issues and problems that pupils may encounter in daily life and as such, equips pupils with the ability to consider how to address or solve these societal problems and events. ‘There is a mutual causal link between geography classes and current events’ (Degirmenci and Ilter Citation2017, 1807). Movement, connectedness and proximity can be examined both locally and globally through social distancing restrictions at local levels to international travel restrictions and quarantine enforcements. Impacts on trade, employment and the provision of essential and non-essential goods and services can be explored. Social inequalities can be examined at a local and global scale such as the possibilities of social distancing in high density areas such as the favelas of Brazil, juxtaposed against holiday-makers and sports fans who aided the spread of the virus at an international level. Never before have geographical boundaries and borders been more clearly defined with new borders and boundaries being created to restrict and constrict movement both locally and globally. Pupils could reflect on their own experiences and examine the impact of Covid-19 restrictions on neighbourhood spaces and places before, during and after the Covid-19 crisis (McKendrick and Hammond Citation2021).

Reimagining geography education: learning lessons from the Covid 19 experience

Covid 19 provides many valuable insights for reimagining geography education by integrating school geography with pupils’ everyday lives. This section outlines how school geography can develop more positive attitudes by: focusing on outdoor learning, the pupils’ immediate local environments; by exploring ‘real-life’ global geography geography using contemporary issues such as climate change; and by positioning pupils as experts and problem solvers through futures thinking and pupil agency.

Outdoor learning

The outdoor environment is a substantial but often underappreciated resource for primary geography (Dolan Citation2016). Pupils’ disengagement with the natural world is well documented. Louv (Citation2008) coined the term ‘nature-deficit disorder’ to describe how a generation of pupils have been deprived of time outside to explore and interact with nature. While some teachers are hesitant to bring pupils outside for reasons related to weather, health and safety and an over-reliance on the textbook, other teachers regularly explore human and physical geography in their localities. In the early twentieth century, outdoor learning in Europe and America was a response to pandemics such as TB and the 1918 flu. The importance of ventilation and fresh air has once again been highlighted during Covid-19. As a response, some schools have built outdoor classrooms and learning spaces while others have increased the amount of outdoor time for pupils. Originally initiated for health and safety reasons, a focus on outdoor learning can be also used to achieve important aims of the primary geography curriculum.

Focusing on the local

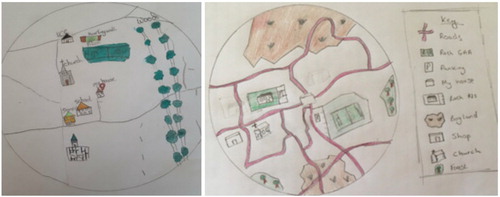

During the Covid-19 lockdowns in Ireland, 2 km and 5 km limits on all travel resulted in a rediscovery of local hidden treasures and an enhanced appreciation of nature. The Heritage Council and National Museum of Ireland launched the initiative ‘Know your 5km’ designed to help the public document and share discoveries about local heritage. Using a 2 km/5 km radius helps pupils to focus on local amenities by noticing, exploring and documenting local human and natural geographical features. The potential for mapping local areas using the 2km/5km radius described by Dolan and Usher (Citation2020, Citation2021) allows pupils to discover the extraordinary in their local ordinary, everyday environs. Geographical fieldwork conducted within a 5 km radius enhances the use of geographical vocabulary to describe local physical features such as: beaches, cliffs, coast, forests, hills, mountains, and human features, including: city, town, village, factory, farm, office, shop, and port. Other skills associated with fieldwork and mapping can also be developed including the use of locational and directional language, working with a compass and spatial awareness (see ).

Focusing on the global

The pandemic offers a lens for exploring other significant global crises such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Pupils are directly affected by contemporary issues such as Covid-19, hence the potential for integrating their experiences and personal prior knowledge are substantial. Since the Covid-19 outbreak, the world’s attention has been focused on the pandemic and the coordination of the emergency response. Meanwhile, major sustainable development challenges, including the greatest challenge of our times – climate change – remain unresolved. In theory, climate change will be more devastating than Covid-19, yet local and global responses are grossly inadequate. While Covid-19 is a rapidly unfolding crisis which caught the world by surprise, the impacts of climate change have been evident for decades. Education has been recognized as a crucial element to counter climate change (Dolan Citationforthcoming). A re-imagination of geography education focusing on pupils’ agency can make the challenges of climate change accessible in primary classrooms.

Futures thinking

The Covid-19 crisis has upended the world, setting in motion tremendous change with a wide range of possible trajectories. While the future implications of coronavirus are uncertain, there is much discussion now about a ‘new normal’. Futures thinking is designed to consider possible, probable and preferable futures. A creative and exploratory process, futures thinking uses divergent thinking, seeks many possible answers and acknowledges uncertainty. Hicks (Citation2007) describes futures studies as a source of expertise which can be used by geographers to develop a futures dimension in the curriculum. By focusing on pupil concerns about the future, Hicks encourages us to focus more critically and creatively about the future.

Using a geographical enquiry framework (Roberts Citation2013) approach, pupils can incorporate a futures dimension as follows (see ):

Table 1: Futures dimension framework.

Allowing pupils an opportunity to consider a range of futures, helps them to appreciate that the future is not predetermined, it is dependent on current choices and actions.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic is an unanticipated event of epic proportions that has exposed human fragility in an interconnected and interdependent world. Notwithstanding the seriousness of the issue, Covid-19 provides a significant teachable moment for geography in primary classrooms. Geographical perspectives provide a framework for exploring global crises such as Covid-19 including its interrelated spatial and temporal dimensions. Reimagining school geography allows teachers to teach contemporary issues such as Covid-19 in an authentic context by making connections with pupils’ everyday lives. Geography, through concepts such as space, place, scale and interdependence, enables pupils to develop twenty-first-century skills and competencies, to analyse and form opinions about real-world issues, and to understand and challenge how the world works. Here, geographical perspectives encourage a deeper concept of how phenomena are interrelated, locating private, local issues and actions, in a wider, public, global scale. This paper argues that integrating school geography with pupils’ everyday lives through the focus on Covid-19 will result in more preferred learning methods being employed in classroom practices, broader recognition of pupils’ everyday personal geographies and wider appreciation for the relevance of the subject.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joe Usher

Joe Usher is an assistant professor inPrimary Geography education and Social, Environmental and Scientific Education (SESE) at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. He works in the area of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and Professional Learning.

Anne M. Dolan

Anne M. Dolan is a lecturer in Primary Geography education inthe Department of Learning, Society and Religious Education at the Faculty of Education, Mary Immaculate College. She is author of PowerfulPrimary Geography: A Toolkit for 21st Century Learning (Routledge 2020).

References

- Bale, J. 1987. Geography in the Primary School. London: Routledge.

- Catling, S. 2010. “Understanding and Developing Primary Geography.” In Primary Geography Handbook, edited by S. Scoffham, 74–91. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Catling, S., and F. Martin. 2011. “Contesting Powerful Knowledge: The Primary Geography Curriculum as an Articulation Between Academic and Children’s (Ethno-) Geographies.” The Curriculum Journal 22 (3): 317–335.

- Degirmenci, Y., and I. Ilter. 2017. “An Investigation Into Geography Teachers' Use of Current Events in Geography Classes.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 5 (10): 1806–1817.

- Dolan, A. M. 2016. “Place-based Curriculum Making: Devising a Synthesis Between Primary Geography and Outdoor Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16 (1): 49–62.

- Dolan, A. M. 2020. Powerful Primary Geography: A Toolkit for 21st Century Learning. London: Routledge.

- Dolan, A. M. forthcoming. Teaching Climate Change in Primary Schools: An Interdisciplinary Approach. London: Routledge.

- Dolan, A. M., and J. Usher. 2020. The Geography of Covid-19 inTouch, into Teacher’s Magazine November/December 2020, p. 52–53.

- Dolan, A. M., and J. Usher. 2021. “Where in the World Is Covid-19? Teaching About Covid19 Through Primary Geography.” Primary Geography 104 (1): 10–12.

- Dolan, A. M., F. Waldron, S. Pike, and R. Greenwood. 2014. “Student Teachers’ Reflections on Prior Experiences of Learning Geography.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (4): 314–330.

- Hicks, D. 2007. “Lessons for the Future: A Geographical Contribution.” Geography 92 (3): 179–188.

- Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO). 2005. The Primary School Curriculum: INTO Survey. Dublin: INTO.

- Krause, U., T. Béneker, and J. van Tartwijk. 2021. Geography Textbook Tasks Fostering Thinking Skills for the Acquisition of Powerful Knowledge. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, pp.1–16.

- Lee, J., S. Catling, G. Kidman, R. Bednarz, U. Krause, A. A. Martija, K. Ohnishi, D. Wilmot, and S. Zecha. 2021. “A Multinational Study of Authors’ Perceptions of and Practical Approaches to Writing Geography Textbooks.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 30 (1): 54–74.

- Louv, R. 2008. Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. New York: Algonquin Books.

- Martin, F. 2006. “Everyday Geography: Re-visioning Primary Geography for the 21st Century.” Geographical Education 9 (1): 31–37.

- Martin, F. 2008. “Ethnogeography: Towards Liberatory Geography Education.” Children's Geographies 6 (4): 437–450.

- McKendrick, J. H., and L. Hammond. 2021. “Connecting with Children’s Geographies in Education.” Teaching Geography 1 (1): 118–121.

- NCCA. 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Geography. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Pike, S. 2006. “Irish Primary School Children’s Definitions of ‘Geography’.” Irish Educational Studies 25 (1): 75–91.

- Pike, S. 2011. ““If You Went Out It Would Stick”: Irish Children’s Learning in Their Local Environments.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 20 (2): 139–159.

- Pike, S. 2015. “Primary Geography in the Republic of Ireland: Practices, Issues and Possible Futures.” Review in International Geographical Education Online 5 (2): 185–198.

- Roberts, M. 2013. Geography Through Enquiry: Approaches to Teaching and Learning in the Secondary School. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Roth, W. M. 2014. “Personal Health-Personalized Science: A Phenomenological Approach.” International Journal of Science Education 36 (9): 1434–1456.

- Usher, J. 2019b. “BREXIT and Borders in the Geography Classroom: Exploring Life on the Irish Border with Students Aged 10-12 Years old.” Teaching Geography 44 (3): 21–25.

- Usher, J. 2020. “Is Geography Lost? Curriculum Policy Analysis: Finding a Place for Geography Within a Changing Primary School Curriculum in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 39 (4): 411–437.

- Waddington, S. 2017. “What do People Remember and What do Teachers Assume About Primary Geography in Ireland.” In Reflections on Primary Geography, edited by S. Catling, 167–170. London: CMP Book Printing.

- Weiss, G. 2017. “Problem-oriented Learning in Geography Education: Construction of Motivating Problems.” Journal of Geography 116 (1): 206–216.