Abstract

Educational disruption due to COVID-19 ushered in dramatically different learning realities in Ireland. Our research explored the experiences of children, young people and parents during the first period of ‘schooling at home’ (SAH) at the end of that academic year. An anonymous online survey, guided by social constructivist emphases, yielded responses from 2733 parents and 1189 students from primary and second-level schools. Substantial evidence emerged of parent-perceived and student-perceived negative psychosocial impacts of SAH on students. Further, our research clarified the exceptional stress experienced by parents in attempting to support SAH. A novel finding was student perceptions of having learned less during SAH, most likely due to significant declines in academic engagement. Recommendations for potential future periods of SAH include the need for innovative means of simulating socio-collaborative contexts, more flexible school supports based on unique home learning contexts, and enhanced psychological support for parents and at-risk children/young people. In addition, we recommend that further research in the Irish context should specifically investigate the perspectives and experiences of those from minority ethnic and lower socio-economic groups.

1. Introduction

In 2020, families around the world found themselves subjected to a ‘new normal’ when schools in over 191 countries were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic (UNESCO Citation2020). In the Republic of Ireland, educational disruption affected close to one million children and young people (CSO Citation2020). In this new context, they encountered a range of challenges including dramatic changes in daily routines (Prime, Wade, and Browne Citation2020), social isolation (Loades et al. Citation2020), unfamiliar virtual learning environments (UNESCO Citation2020), and a loss of critical professional services beyond education (i.e. nutrition, child safety, mental health services) (Golberstein, Wen, and Miller Citation2020). Contemporaneously, parents/guardians were faced with juggling the continuing, if not intensified, demands of work and domestic life, with the responsibility of meeting the educational needs of their children (Prime, Wade, and Browne Citation2020). This pattern of challenges was replicated across all levels of society, but it was quickly recognised that marginalised students and families were particularly vulnerable to the impact of school closures (Sahlberg Citation2020).

During the first school buildings closure period (March to May/June 2020), numerous studiesFootnote1 were conducted to explore experiences of ‘schooling at home’Footnote2 (hereafter, SAH) in Ireland, with the voices of school leaders, teachers, parents, and students represented. In general, this body of research indicated that Irish teachers and school leaders perceived a variable level of student engagement with SAH, with parental involvement (e.g. Mohan et al. Citation2020), and teacher use of collaborative and interactive pedagogies (e.g. Devitt, Bray, et al. Citation2020) being prominent predictors. Further, parental satisfaction with support from schools was variable, with some parents reporting that the continuity of their child(ren)’s learning and support was inadequate (e.g. Devitt, Ross, et al. Citation2020; Kelly et al. Citation2020). Regarding perceived and experienced impacts of SAH, many parents reported that being out of school had adverse psychological effects for their children (e.g. O'Sullivan et al. Citation2021). From a student perspective, the most salient stressor of SAH was a loss of peer interaction and support and, for second-level students, an increase in school workload (e.g. Galway City Comhairle na n’Óg Citation2020). Furthermore, in keeping with findings from other countries (e.g. Petretto, Masala, and Masala Citation2020), concerns were prevalent among parents and educators that SAH was exacerbating existing educational difficulties for students with English as an Additional Language, students from disadvantaged backgrounds, and students at key transitional stages such as examination years (e.g. Doyle Citation2020).

This exploratory study was developed and conducted in the context of a COVID-19 ‘rapid response research programme’ within the research team’s institution (NUI Galway). It aimed to build upon and extend existing Irish research by exploring the experiences of children, young people and parents from the vantage point of the end of the 2019–2020 academic year, which allowed for reflection on the entire first period of SAH. In this ‘rapid response research’ context, while the SAH study did not explicitly employ an overarching theoretical framework from the outset, our research design was strongly informed by social constructivist (cf. Vygotsky Citation1978) emphases, including concerns about the nature of student engagement in (remote) learning in the absence of the socio-collaborative context of the physical school, the resultant challenges of scaffolding therein, and related psychosocial impacts.

The first objective of this paper is to describe findings related to SAH engagement, conceptualised as a multi-dimensional construct comprising of cognitive, emotional and behavioural dimensions (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris Citation2004). The second objective is to report on psychosocial impacts of SAH for children/young people and their parents in Ireland; outcomes that are acquiring increasing attention and prominence in the expanding COVID-19 literature (Thorell et al. Citation2021).

2. Method

The study was implemented in the Republic of Ireland between June 17th and August 10th 2020 using an anonymous online survey. Full ethical approval for the research was obtained from the NUIG Research Ethics Committee. Parents were recruited via a database of parent affiliates from the National Parents’ Council (Primary), social media channels, and networks of the research team. Student respondents were accessed solely through their parents.

The final sample included 2733 parents and 1189 students from primary and second-level schools. The parent sample comprised predominantly ‘White-Irish’ (87.4%)Footnote3and female (91%) parents who were of high socio-economic status [indicated by non-possession of a medical card (87%) and having a third-level qualification (79%)]. The majority (74.5%) were parents of a child who attended primary school of non-DEISFootnote4 (i.e. non-disadvantaged) status (76.5%). 12.7% of participating parents reported that their oldest school-age child usually received learning support due to an Additional Educational Need (AEN). The final student sample comprised 896 primary school children, and 293 second-level students.

Survey questions focused on demographic factors, organisation of SAH, levels of engagement with SAH, positive and negative aspects of SAH, and psychosocial impacts of SAH. Responses to closed-ended survey questions were analysed using descriptive statistics, T tests, or Chi Square Tests of Association. A quantitative-based content analysis approach was used for short open-ended survey responses, whereas a more inductive approach was employed for elaborated and nuanced responses (Schreier Citation2014).

3. Findings

3.1. Engagement in SAH

It was found that the most common approaches adopted by Irish schools for organising SAH were emails with instructions for work (Primary (P): 75.3%, Second-Level (S): 67.5%), and apps or online platforms (P: 69.4%, S: 74.2%). Asynchronous inputs were most prevalent, with live online teaching experienced by 19% of primary and 58.5% of second-level students. A strong desire for more consistency and direction from the Department of Education, so as to ensure equitable access to the curriculum within and across schools, featured in many open-ended responses throughout the survey.

A number of different closed and open-ended survey items were used to explore cognitive engagement (interest in SAH, learning), emotional engagement (enjoyment of SAH) and behavioural engagement (time spent in SAH). In relation to emotional engagement, the majority of primary respondents (66.5%) reported variable enjoyment of SAH, whereas the second-level sample was split between reports of variable enjoyment (44.3%) and a consistent lack of enjoyment (40.1%). Primary respondents particularly enjoyed project and practical work, technology-related activities, extracurricular activities, and spending extra time with family. Second-level students enjoyed getting up later, and following their own more flexible learning schedule. They also identified being away from disruptive students or bullies (‘kids being mean to me’; ‘eejits in my class disrupting class’) as positive aspects of SAH. Primary respondents reported that they did not enjoy academic subjects with which they felt they needed their teacher’s help (e.g. Irish and Mathematics), and many also reported missing fun aspects of school and important events. For second-level students, the least enjoyable aspects of SAH were missing their friends, a lack of communication with and support from teachers, and coping with a more intense workload.

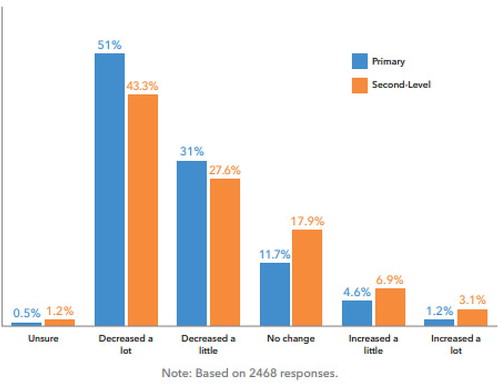

Behavioural engagement was found to be significantly lower for primary students (M = 2.2 h, SD = 1.1) than for second-level students (M = 3.6 h, SD = 1.9), t(2439) = −22.79, p < .001. In addition, it was found that cognitive engagement had decreased over the first SAH period (see ), with significantly greater decreases in interest being reported by parents for primary students, χ2 = 37.82, df = 5, p < .001. Corresponding with parent reports, the majority (67.1%) of second-level students reported that their interest in SAH had either decreased ‘a little’ or ‘a lot’. In open-ended responses, many students emphasised their lack of motivation towards schoolwork, with a significant number of both second-level students and parents referencing a lack of communication with, and support from, teachers. Importantly, 73% of the second-level and 52% of the primary respondents reported that they had learned either a ‘little less’ or a ‘lot less’ at home than at school.

3.2. Psychosocial impacts

The majority of parents reported that SAH had a mild negative impact on various academic and social-emotional aspects of their child’s life, with impacts on routine being most prominent (see ). Comments from parents in open-ended items reiterated concerns about the mental health and social-emotional impacts of SAH. In terms of academic impacts, parents expressed concerns about academic progression, particularly where their child was entering Senior Cycle or Leaving Certificate the next academic year, transitioning to second-level, or if their child had an AEN. In an item asking second-level students to report on the impact of SAH on their learning, routine, confidence, independence, and mental health, the only aspect of their life that they reported being impacted somewhat positively, as indicated by a mean rating above the 7-point Likert scale midpoint (M = 4.25, SD = 1.81), was their independence. Contrastingly, they reported that all of the other listed aspects of their lives were mildly negatively affected by SAH, with learning being the most significantly impacted (M = 3.04, SD = 1.63).

Table 1. Primary and second-level parent reports of perceived impacts of SAH on specified aspects of their children’s lives.

Social interaction was a factor highlighted by the vast majority of both primary and second-level respondents as something they greatly missed, most notably with their friends, but also with their teachers. Typical comments included: ‘I really missed my friends and I was worried I wouldn’t have friends when I got back to school’, and ‘I missed the way the teacher helped us with our work’. Analysis of relevant open-ended items revealed parents’ significant concern about potential deleterious effects of the lack of social interaction, the loss of time with friends, and the loneliness triggered by this isolation.

With respect to effects of SAH on parents, responses indicated adverse psychosocial impacts. Mothers were found to be the main home support for students (P & S: 73%). The impossibility of working full-time and simultaneously caring for and ‘schooling’ their children was made clear in their comments (‘not feasible’, ‘impossible’, ‘unrealistic’, ‘stressful’, ‘draining’, ‘far too much’). They emphasised their lack of ability to adequately support their children’s academic work, particularly at second-level (‘We are not teachers’). In particular, working parents, single parents, parents of multiple children, and parents of children with AEN, expressed high levels of burnout and exhaustion. Some stated that they had done the bare minimum, and/or that they ‘gave up’ altogether:

I actually gave up on schooling at home as my 2 other children are 1 and 3 years. My partner is a medical professional and was not at home for support. I was working from home full time and I had zero child care. It became humanly impossible to meet all the responsibilities so I let the schooling go.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Our main findings align with previous research in several respects: asynchronous online inputs being the most common mode for organisation of SAH (e.g. Devitt, Bray, et al. Citation2020); the lack of social interaction with peers being the most negative aspect for students (e.g. Buheji et al. Citation2020; Galway City Comhairle na n’Óg Citation2020); mothers/female guardians being the main SAH support for students (e.g. Bonal and González Citation2020); and a strong desire from parents and educators for more consistency and direction from the Department of Education to ensure equity of access to the curriculum across schools (e.g. Kelly et al. Citation2020).

In terms of engagement with SAH, conceptualised as a multi-dimensional construct comprising of cognitive, emotional and behavioural elements (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris Citation2004), we found that students’ reported levels of engagement had declined over the first period of SAH. In particular, a novel finding of our study was student perceptions of having learned less during SAH relative to school. We believe that this may have had implications for academic self-efficacy on return to school due to reduced mastery experiences (Zimmerman Citation2000). Academic self-efficacy has consistently been found to predict academic performance, mediated by effort regulation, choice of processing strategies, and goal selection (Honicke and Broadbent Citation2016), and thus, it is important to pre-empt declines in self-efficacy wherever possible. Consequently, for potential future periods of SAH, we recommend more focus from schools on monitoring, enhancing and sustaining students’ engagement through regular live online classes, meaningful learning tasks, and collaborative learning with peers. The reported decrease in students’ academic engagement and learning over time is unsurprising; the sudden and prolonged closure of physical school buildings removed the social learning context of schooling, a base necessity for successful engagement in learning from a social constructivist perspective (Vygotsky Citation1978). From this theoretical perspective, scaffolding (within a Zone of Proximal Development framework, ibid.), so highly dependent upon socio-collaborative processes, needs to be reconceptualised as well as reactualised. Indeed, in the context of higher education (HE) online education, Bryceson (Citation2007) has noted the challenge of providing scaffolding mechanisms that adequately facilitate online socialisation and ‘deep learning’, and we recognise the additional barriers presented by teaching online with younger learners, including in relation to GDPR and child protection We contend that for future periods of SAH, educators need to proactively reimagine opportunities for meaningful online connection among students (peer-peer and student-teacher), from collaborative learning with peers during live classes, to broader online social interaction opportunities. While research has identified relatively effective online engagement strategies for students in HE (cf. Lehman and Conceição Citation2014; McLoughlin, Winnips, and Oliver Citation2000), research in this area to support school-aged children and young people is needed, followed by rapid and targeted high quality professional development for teachers. As well as supporting students’ academic engagement and learning, such an approach would also mitigate adverse psychosocial consequences by more actively supporting students’ needs for relatedness, which Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) considers to be a universal basic need for psychological wellbeing and optimal functioning.

Corresponding with international research (e.g. Lee Citation2020), we found substantial evidence of parent-perceived and student-perceived negative psychosocial impacts of SAH on students, likely linked to the experience of social isolation from peers and friends. Since it is estimated that half of all lifetime psychological disorders have their onset by mid-adolescence (Kessler et al. Citation2007), we consider it important that more funding be directed to enhancing co-ordinated, timely and accessible psychological support services for school-aged individuals who are experiencing new or re-emerged clinical-level psychological symptoms.

Congruent with international findings (cf. Thorell et al. Citation2021 for findings of a seven-country European study), our research clarified the exceptional amount of stress experienced by parents in Ireland in attempting to support SAH. This was particularly observed for parents with several children, parents who were working, and parents with children with AEN. Thus, for future periods of SAH, we believe that demands associated with unique home learning contexts need to be considered more carefully, followed by the initiation of individualised and concrete capacity-building supports for parents (e.g. training in the adopted online learning platform). At community-level, parents would likely benefit from access to universal short-term psychological support delivered by phone and/or internet service, for example.

School building closures, as a strategy to mitigate community transmission of COVID-19, has represented one of the most significant shocks to education ever experienced in Ireland. At the time of writing (February 2020), anecdotal evidence suggests an improved student experience of remote learning during the second period of SAH (January 2021 onwards). However, it is unclear to what extent this has been the experience of all students, and particularly whether students from marginalised groups have participated in and benefitted from SAH in Ireland (OECD Citation2021). Accordingly, we recommend that further research in the Irish context should specifically explore the perspectives and experiences of those from minority ethnic and lower socio-economic groups during ‘SAH 2.0’ using a combination of real-time and retrospective methodologies. It is our hope that the hard-gained insights from this period of online provision will not decay in the rush to ‘normalcy’, but rather will provide the impetus for a reimagining of education in Ireland where people and purpose will be at the heart of future innovation.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Niamh Flynn

Dr. Niamh Flynn is an Educational Psychologist, and Lecturer in Educational Psychology, Inclusive Education, and Research Methods, in the School of Education at NUI Galway. Her research interests are focused on inclusive education, social-emotional learning, and student and teacher wellbeing.

Elaine Keane

Dr. Elaine Keane is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology of Education and Research Methods, and Director of Doctoral Studies, in the School of Education at NUI Galway. Her research and publications centre on widening participation in higher education, social class and ethnicity in education, and diversifying the teaching profession.

Emer Davitt

Emer Davitt is a Lecturer in Education, primarily with the Máistir Gairmiúil san Oideachas, in the School of Education at NUI Galway. Her research and publications centre on Irish language education, teacher pedagogy and wellbeing in the curriculum.

Veronica McCauley

Dr. Veronica McCauley is a researcher and lecturer in science education in the School of Education, NUI Galway. She publishes regularly in the field of science education, science communication and public engagement, technology education, and related areas; and holds the seat of Vice-Chair at NUI Galway's University Ethics.

Manuela Heinz

Dr. Manuela Heinz is the Director of Teaching and Learning at the School of Education and joint programme director of the Professional Master of Education at NUI Galway. Her research focuses on diversity in teacher education and schooling and teacher professional learning.

Gerry Mac Ruairc

Prof. Gerry Mac Ruairc is the Established Professor of Education and Head of School in the School of Education, NUI Galway and Senior Research Fellow with the UNESCO Child and Family Centre at NUI Galway. He has published widely in the areas of leadership for inclusive schooling and school improvement for equity and social justice.

Notes

1 This summary literature review provides examples of key themes from the national and international literature but is not exhaustive due to the word count limit.

2 We developed the term ‘schooling at home’, a novel descriptor, to capture parents’ and children’s experiences of navigating school-at-home during the closure of school buildings, and to differentiate from ‘homeschooling’, which is typically understood as “voluntary parent-directed learning in the home that substitutes partially or completely for attendance at a regular school” (Peters and Dwyer Citation2019, 3).

3 Irish Census categories were employed to ascertain participant ethnicity.

4 Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) (Department of Education and Skills Citation2005).

References

- Bonal, X., and S. González. 2020. “The Impact of Lockdown on the Learning Gap: Family and School Divisions in Times of Crisis.” International Review of Education 66 (5): 635–655. doi:10.1007/s11159-020-09860-z.

- Bryceson, Kim. 2007. “The Online Learning Environment—A New Model Using Social Constructivism and the Concept of ‘Ba’as a Theoretical Framework.” Learning Environments Research 10 (3): 189–206.

- Buheji, M., A. Hassani, A. Ebrahim, K. da Costa Cunha, H. Jahrami, M. Baloshi, and S. Hubail. 2020. “Children and Coping During COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Bio-Psycho-Social Factors.” International Journal of Applied Psychology 10 (1): 8–15.

- CSO. 2020. Department of Education Statistics. Dublin: Central Statistics Office. Accessed 1 February, 2020. https://www.cso.ie/en/databases/departmentofeducation/.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2005. Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. An Action Plan for Educational Inclusion. Dublin: DES.

- Devitt, A., A. Bray, J. Banks, and E. Ni Chorcora. 2020. Teaching and Learning During School Closures: Lessons Learned. Irish Second-Level Teacher Perspectives. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin.

- Devitt, A., C. Ross, A. Bray, and J. Banks. 2020. Parent Perspectives on Teaching and Learning During Covid-19 School Closures: Lessons Learned from Irish Primary Schools. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin.

- Doyle, O. 2020. COVID-19: Exacerbating Educational Inequalities? Dublin: University College Dublin.

- Fredricks, J. A., P. C. Blumenfeld, and A. H. Paris. 2004. “School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence.” Review of Educational Research 74 (1): 59–109. doi:10.3102/00346543074001059.

- Galway City Comhairle na n’Óg. 2020. Online Learning Survey Report. Galway: Galway Comhairle na nÓg.

- Golberstein, E., H. Wen, and B. F. Miller. 2020. “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents” JAMA Pediatrics 174 (9): 819–820.

- Honicke, T., and J. Broadbent. 2016. “The Influence of Academic Self-Efficacy on Academic Performance: A Systematic Review.” Educational Research Review 17: 63–84. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002.

- Kelly, N., F. Fleming, B. Demirel, and J. O'Hara. 2020. The Real Cost of School 2020: Back to School Survey Briefing Paper. Dublin: Barnardos.

- Kessler, Ronald C., G. Paul Amminger, Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Jordi Alonso, Sing Lee, and T. Bedirhan Ustün. 2007. “Age of Onset of Mental Disorders: A Review of Recent Literature.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 20 (4): 359–364. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c.

- Lee, J. 2020. “Mental Health Effects of School Closures during COVID-19.” The Lancet Child and Adolescent Mental Health 4 (6): 421. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7.

- Lehman, R. M., and S. C. O. Conceição. 2014. Motivating and Retaining Online Students: Research-Based Strategies That Work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Loades, M. E., E. Chatburn, N. Higson-Sweeney, S. Reynolds, R. Shafran, A. Brigden, C. Linney, M. N. McManus, C. Borwick, and E. Crawley. 2020. “Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19.” Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 59 (11): 1218–1239.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009.

- McLoughlin, C., K. Winnips, and R. Oliver. 2000. “'Supporting Constructivist Learning Through Learner Support Online’.” In Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications, edited by J. Bourdeau, and R. Heller, 674–680. Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Mohan, G., S. McCoy, E. Carroll, G. Mihut, S. Lyons, and C. Mac Domhnaill. 2020. Learning for All? Second-Level Education in Ireland During Covid-19. Dublin: ESRI.

- OECD. 2021. The State of School Education: One Year Into the COVID Pandemic. Paris: OECD.

- O'Sullivan, K., S. Clark, A. McGrane, N. Rock, L. Burke, N. Boyle, N. Joksimovic, and K. Marshall. 2021. “A Qualitative Study of Child and Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ireland.” International Journal of Public Research and Environmental Health 18 (3): 1062–1076. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031062.

- Peters, J. G., and S. F. Dwyer. 2019. Homeschooling: The History and Philosophy of a Controversial Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Petretto, D. R., I. Masala, and C. Masala. 2020. “Special Educational Needs, Distance Learning, Inclusion and COVID-19.” Education Sciences 10 (6): 154–155. doi:10.3390/educsci10060154.

- Prime, H., M. Wade, and D. Browne. 2020. “Risk and Resilience in Family Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” American Psychologist 75: 631–643.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Sahlberg, P. 2020. “Will the Pandemic Change Schools?” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5 (3/4): 359–365. doi:10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0026.

- Schreier, M. 2014. “Qualitative Content Analysis.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 170–183. London: Sage.

- Thorell, L. B., C. Skoglund, A. G. de la Peña, D. Baeyens, A. B. M. Fuermaier, M. J. Groom, I. C. Mammarella, et al. 2021. “Parental Experiences of Homeschooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences between Seven European Countries and between Children with and Without Mental Health Conditions.” European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1.

- UNESCO. 2020. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. UNESCO. Accessed 1 February 2020. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. 2000. “Self-efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 82–91. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1016.