Abstract

Teachers today must not only be prepared to use technology but must also know how to use it (Butler, D., K. Marshall, and M. Leahy. 2015. Shaping the Future: How Technology Can Lead to Educational Transformation, 1st ed. Dublin: Liffey Press). The purpose of this study was to explore two primary physical education initial teacher educator’s (PEITE’s) professional learning experiences while introducing iPads into a physical education module. The module’s focus was to promote quality teaching, learning and assessment of fundamental movement skills in physical education with pre-service generalist primary teachers. It was a qualitative study utilising lesson study methodology. Data included audio files, video recordings and field notes. Following analysis, three themes were developed: learning the technology, managing the technology and integrating the technology. The findings showed that for the PEITEs, time was a valuable commodity while grappling with technological knowledge, technological pedagogical knowledge and pre-service teachers’ physical education knowledge. Self-directed learning was an enabler to facilitate technological and pedagogical competence for the PEITEs. Although managing aspects of the technology, such as limited Wi-Fi access and technical support, was a challenge, the PEITEs continued to integrate iPads into their teaching.

Introduction and context

Generalist primary teachers face many challenges, including the demands of new technologies, and ultimately, these demands require changes in classroom practices. They must be skilled in technology applications and knowledgeable about using technology to support instruction and to enhance and extend children’s learning (Rosenthal and Eliason Citation2015; Armour et al. Citation2017; McGarr and McDonagh Citation2021). Primary school teachers should be able to demonstrate an ability to use technology tools in their teaching of all curriculum areas, including physical education, to promote children’s learning, improve children’s achievement and provide children with the skills they need in their future education and/or workplace careers. ‘Achieving adequate levels of digital competency is not without its challenges’ (McGarr and McDonagh Citation2021, 117). While Bakir (Citation2015) acknowledged that opportunities for technology training have become more available to prospective teachers, it is evident that despite the international recognition and encouragement to adopt technology, its integration in teacher education is also a challenge. van Hilvoorde and Koekoek (Citation2018) highlight the pedagogical implications of incorporating technology into physical education and its ability to reshape educational practices. They believe that due to the pervasiveness of technology in everyone’s daily activities and resulting changes to our behaviours it must be embraced. Initial teacher educators (ITEs) must become proficient at technology use and must come to understand content-specific, pedagogical uses of technology for their own teaching. PEITEs should be involved in adapting and aligning the technology and the science to the specific characteristics of their educational contexts.

Traditionally teacher education programmes offer stand-alone educational technology or digital learning courses as a part of pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) professional programmes (Lambert and Gong Citation2010) to address the technological requirements; however, integration of technology is becoming more the norm in teacher education programmes. In highlighting the important role of PEITEs in supporting PSTs to integrate technology into their teaching, it is important to note that there are few discussions of how PEITEs can develop their own understanding of these devices for learning and teaching, as they strive to evaluate and incorporate these devices into their teaching (Schuck et al. Citation2013).

The landscape of pre-service teacher education at the time of this study was a changing one. The Bachelor of Education programme had increased from three to four years in line with the Confederation of European University Rectors’ Conferences and the Association of European Universities (1999). This allowed for innovations (Waldron et al. Citation2012), including the weaving of key themes into all modules, for example, inclusion and digital technology rather than having stand-alone modules (Teaching Council Citation2011). Special options in curricular areas for PSTs to specialise in were introduced (Marron, Murphy, and Coulter Citation2018) and modules were created to respond to current research and policy, for example, physical education and digital learning.

The digital landscape in Ireland during this time was one where the potential for digital technologies to transform teaching and learning in Irish schools had not been realised (Woods Citation2019). In brief, Cosgrove et al. (Citation2014) highlighted insufficient levels of technical support, the age of computing devices, and insufficient time for planning and preparation, the pressure to cover the prescribed curriculum and insufficient access to technology for children as challenges to the effective use of technology to support teaching and learning in primary schools. Broadband and internet safety and related issues were also noted as obstacles. Eivers (Citation2019) tracked the key policy document trail in Ireland related to technology in primary schools, including the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) Integration of Information Communication Technology (ICT) in the Primary School Curriculum: Guidelines for Teachers (Citation2004) and the Framework for ICT in Curriculum and Assessment (Citation2007). Eivers highlighted the Inspectorate Report (Department of Education and Skills (DES) Citation2008) calling for technological infrastructure in classrooms, a national technology support and maintenance system, more continuous professional learning and a greater emphasis on technology at initial teacher education. The Digital Strategy for Schools 2015–2020 (DES Citation2015) and related policy documents that followed showed a clearer commitment to advance the progress of technology in schools. More recently, the inclusion of the children being a digital learners as a key competency in the Draught Primary Curriculum Framework (NCCA Citation2020) is a significant progression with wide-ranging implications for teachers and teacher educators and their work in all curriculum areas, including physical education.

Technology, knowledge and physical education

Technology is based on the Greek word technè, which means ‘craft’ or ‘art’ and the Greek word logos, meaning word or discourse. It refers to concrete artefacts, designed and produced by humans and the use of these artefacts by humans. In addition, technology also concerns the knowledge necessary to generate new technological solutions and refers to the knowledge about the technology design process and its applications in practice. All three meanings of technology are relevant for the role technology may play in education. In this study, we are concerned with the role of technology, specifically the iPad, and its application in practice.

The literature suggests that effective technology integration with specific subject matter requires teachers to apply their knowledge of curriculum content, general pedagogies, and technologies. This approach, known as the ‘technological pedagogical content knowledge’ TPCK (currently known as TPACK) model (Koehler and Mishra Citation2008), is grounded on Shulman’s (Citation1987) idea that teachers should be able to apply their content knowledge in a pedagogically sound way that is adaptable to the characteristics of children and to the educational context. Content knowledge (CK) refers to the mastering of major facts, concepts and relationships within a particular field. For example, a physical education teacher should possess a basic understanding of motor learning in physical activities. Technological content knowledge (TCK) refers to one’s awareness of the available technology, knowing how to use it, and understanding its purpose within the content of the specific subject matter. Leight, Banville, and Polifko (Citation2009) stated that both the rapid increase in technological capabilities and falling costs had made the use of technology in physical education more accessible. However, Kirkwood and Price (Citation2014) question the extent to which effective use is being made of technology to improve the learning experience of students.

Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), proposed by Shulman (Citation1987), is the combination of the knowledge of teaching strategies and concepts to be taught and strategies for evaluating student understanding (Mishra and Koehler Citation2006). Teachers must have a rich and flexible knowledge of the subjects they teach (Borko Citation2004) because without this, how can they adapt and use this knowledge (pedagogical content knowledge) for the benefit of the children they teach? It then follows that technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) refers to one’s knowledge of the various technologies that can be integrated and utilised in educational settings. This can be evidenced when a physical education teacher, who has high TPK, can easily select the appropriate tool or device to use in teaching by taking into account the child’s readiness level and the activity to be learned.

Teachers’ confidence (self-efficacy) and motivation (outcome expectations) with regard to integrating technology in education are considered important variables in teaching effectiveness (Niederhauser and Perkmen Citation2010); however, the speed at which technological know how to operate particular technologies becomes obsolete as new technologies take-over is very challenging (Mishra and Koehler Citation2006). Digital technologies can make things possible; however, it is people that make things happen, and teachers’ pedagogical orientations are pivotal in how digital technologies are used (Butler, Marshall, and Leahy Citation2015).

van Hilvoorde and Koekoek (Citation2018), in their research on physical education, emphasise the importance of PSTs having deep knowledge of how children can learn skills that may be found on tablets, for example, iPads. PSTs must become critical users of technology from a pedagogical lens before they use it in their teaching. There has been a growing interest focussed on the use of iPads as learning devices (Dündar and Akçayır Citation2014). Compared to traditional desktops, users prefer using iPads owing to the mobility and more intuitive operation methods (Reychav and Wu Citation2014). Tablets equipped with wireless network connectivity, high-resolution displays, digital cameras and multi-touch screens, and being light and portable devices, open up innovative learning possibilities for students on the move (Eberline and Richards Citation2013). With the portability of iPads, PSTs are free to record and play videos without hardware limitations when they practise their actions in physical education contexts. However, despite the fact that numerous studies have explored a wide range of technology-based learning, few studies on the use of mobile technology in physical education have been published (Hung, Shwu-Ching Young, and Lin Citation2018). Rosenthal and Eliason (Citation2015) reported on a College of Education iPad initiative where the staff was provided with training to develop their iPad skills and, in turn, were then expected to prepare future teachers to use the iPad as a teaching and learning tool in their future teaching. Their successes included the competence of the PSTs if faculty members modelled the use of the technology in the learning process and faculty members’ confidence increased with basic instruction and familiarity on even one or two applications. Haynes and Miller (Citation2015) succeeded in applying technology to accurately analyse and assess the skill components of performances during physical education lecture time that can be applied in a school setting using smartphones or digital cameras with video recording capabilities.

Theoretical framework

As the PEITEs were learning how to teach something new and different with very little prior knowledge and had little to no professional development in the area of integrating technologies and physical education, the theory of self-directed learning informed this study. Knowles (Citation1975) describes self-directed learning as a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies and evaluating learning outcomes (18).

Dialogue, collaboration and critique were important components that were used to help the PEITEs on their learning journey. ITEs who inquire into their practice with others receive the ‘benefits from the support of colleagues engaged in similar enterprises and the scrutiny of the wider educational community’ (Clarke and Erickson Citation2006, 5). This self-directed inquiry was to explore the PEITEs’ professional learning experiences while introducing iPads into a physical education module.

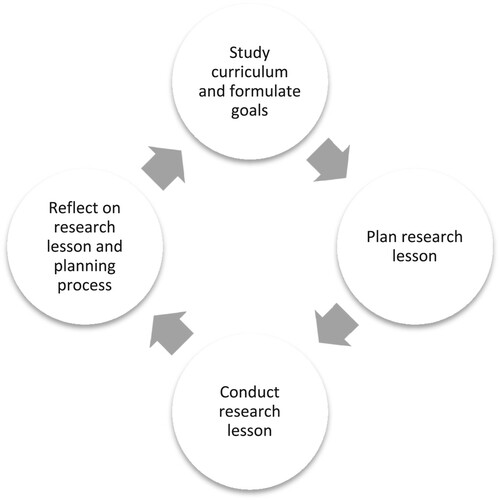

Professional development that is becoming increasingly popular worldwide, but is not yet frequently applied within the physical education domain, is lesson study (Elliott Citation2019; Willems and Van den Bossche Citation2019). Lesson study is a form of systematic classroom inquiry (Lee and Tsai Citation2008; Verhoef, Coenders, and Pieters Citation2015) into the practice of teaching in which teachers or teacher educators collaboratively plan, teach, observe, revise and share the results of a single class lesson. As the PEITEs were engaging in self-directed learning, lesson study provided them with the framework for ‘on the job’ professional development. The two PEITEs who knew the PSTs, the context and the learning outcomes to be achieved came together to undertake in-class inquiry-based research. The PEITEs had identified a specific challenge within their teaching practice, the implementation of TPACK using iPads in order to acquire and deepen new insights through self-directed learning. The practice of lesson study can lead to instructional improvement as the PEITEs become more knowledgeable about how PSTs learn and think and how instruction affects their thinking. A lesson study cycle consists of four steps (see ) (Lewis, Perry, and Hurd Citation2009):

Study curriculum and formulate goals

Plan research lesson

Conduct research lesson

Reflect on research lesson and planning process

Figure 1. Lesson study cycle (Lewis, Perry, and Hurd Citation2009).

While post-lesson discussions and reflections traditionally focus on the student learning that took place during the ‘research lesson’, when teachers are new to lesson study, such as the PEITEs at the centre of this study, they will often focus on their own teaching methods and less on the pre-service students and their learning (Saito, Citation2012). This study explores how two PEITE’s professional learning experiences of introducing iPads into a physical education module underpinned by the TPACK model (Koehler and Mishra Citation2008). The lesson study provided a reflective framework that influenced the PEITEs’ practices and how it informed their learning and professional development.

Methodology

This qualitative study, utilising lesson study, focussed on one cycle of the lesson study process during a 2-hour lesson in a second-year module. During the lesson, the PSTs, in pairs, were required to observe, analyse and self and peer assess their own performance of a fundamental movement skill using an iPad and checklists. They had to represent the teaching of this skill in a two-minute video clip using the iMovie and Explain Everything Apps. The PSTs had to include demonstrations and the teaching of activities to support the development and practice of the skill at three stages of development – beginning, developing and consolidating (Graham, Holt/Hale, and Parker Citation2010).

Participants

Two primary PEITEs were the participants in the study. Sharon was responsible for the design, and the facilitation of the module and Maria acted as a critical colleague. (Pseudonyms are used here for blind review). The PEITEs had pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) of FMS, but their technological content knowledge (TCK) and technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) required development. The PEITEs’ backgrounds in the use of technology included PowerPoint, Photo Story, Online Adobe classroom and Loop, and the online teaching environment, which provided PEITEs and PSTs with access to electronic teaching and learning materials and activities (such as discussion forums and reflective journals). The PSTs undertaking the lesson had completed one module in the use of digital technologies, specifically in the use of cameras, video, and the interactive whiteboard in the first year of their degree programme.

Data collection

Data were collected during each stage of the lesson study cycle as outlined in . These data consisted of the lesson plan, three sound files from three meetings between the PEITEs [Pre-lesson study meeting one (PM1), Pre-lesson study meeting two (PM2) and Post-lesson study meeting (PTM)] and the field notes taken during these meetings and the lesson. The final piece of data was the video recording of the lesson.

Data analysis

Data were inputted into Nvivo (QSR NVivo Version 10) software for analysis. Data were initially pooled and read by each PEITE. An interpretive-descriptive approach was used, involving the constant comparative method of data analysis proposed by Strauss, Corbin, and Corbin (Citation1998). This is an iterative process in which the data were read, listened to and watched by both PEITEs to determine recurring categories in the content of the data. Data categories emerged directly from this content. Categories were identified independently by each PEITE and these were refined at a further analysis meeting until agreement was reached. All data were analysed further, assigning data to the agreed categories and subcategories, and cross-checked. Finally, similar categories were combined, resulting in three themes; (1) Learning the Technology, (2) Managing the Technology and (3) Integrating the Technology.

Findings and discussion

This study explored the professional learning experiences of the PEITEs as they introduced iPads into one physical education module underpinned with the use of the TPACK model in a primary teacher education programme. Lesson study methodology, informed by self-directed learning theory, guided the research process. The professional learning experiences of the PEITE’s, will be discussed under the themes that developed from the data analysis (1) Learning the Technology, (2) Managing the Technology and (3) Integrating the Technology.

Learning the technology

Learning the technology was a challenge for the PEITEs. It was risky delivering a lesson and being unsure how to use the technology (Fielding et al. Citation2005) or deal with any issues which may have arisen. The National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (Citation1997) believes that all ITEs must experiment with the effective application of computer technology for teaching and learning in their own campus practice to inform PSTs’ skill development. They must develop a fearless attitude in PSTs in relation to developing their technological skills and applications. This was easier said than done when all the PEITEs felt was fear. Sharon’s fear and frustration was evident when she said,

we have not received the training we thought we would get last Friday [when the iPads were installed] which does have implications for the amount of exposure we have got [to upskill] for next Tuesday [lesson] … To be honest I felt a bit overwhelmed that I had to be an expert in all of this. (PM2)

Obrusnikova and Rattigan (Citation2016) all recognised this overwhelming experience even by experienced instructors in their research. While keeping an open mind to the task, Sharon questioned her self-efficacy in teaching effectiveness (Niederhauser and Perkmen Citation2010) rather than the motivation she required to integrate technology in education. Maria reassured Sharon during their planning meetings that the focus was on PCK (Shulman Citation1987) rather than pure TCK (Koehler and Mishra Citation2008);

No I don’t think so, I think we look on it very much from the way we have looked at it from the start, … we don’t have to give them as much input as we thought on the actual skill and technical end of it – they have it. We are talking about the application [of technology] to PE … At the end of the day we want to show students that if we can do it with 25 students you would hope that they would be able to do it with 25 children. I suppose it’s to model that idea. (PM1)

Semiz and Inze (Citation2012, 1259) suggested that ‘university instructors could be better role models for technology integration’, but becoming this role model was challenging. Sharon continued to reassure herself by remembering that those with responsibility for DL had undertaken the TCK learning, she ‘has uploaded a YouTube video tutorial on iMovie App along with a tutorial from the Apple website to the DL website for our project’ (PM2). Again Maria reiterates the purpose of the lesson, ‘it’s applying it to PE that this practice is about … It’s not our responsibility to upskill the students in DL it’s our responsibility to give them opportunities to use it’ (PM2). Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) point out teacher development is more likely to prosper if there is a culture of collaboration amongst those involved. The critical friend in this instance was playing a vital role in ensuring the purpose of the learning was maintained. Sharon and Maria were aware of the PSTs’ learning in stand-alone modules on their degree programme and were building on this knowledge by providing infused modules.

Time became a key commodity in this study, as Maria pointed out early in the study when she questioned, ‘are we getting enough from the time we are going to put into it’ (PM1). However, the PEITEs persevered as they believed in the contribution of iPads to enhance the teaching and learning in physical education. Time in the PEITEs’ work schedule to develop their skill set was found to be an issue learning the iPad technology. Sharon was using her free time to upskill and learn the technology, ‘I am just disappointed myself that I have not had more time to practice using the iPad, maybe now over the weekend to reassure me’ (PM2). Thomas and colleagues (Citation2013) reported that a quality TPCK rich environment is created where infrastructure is provided, including time. They believed that faculty staff requires time to practice using devices to allow innovation and change to happen at the university level. Ciampa and Gallagher (Citation2013) went further than simply providing release time to learn how to use technology for instruction but emphasised the importance of time to think, to engage in discourse and to reflect in a context specific and safe environment. Using lesson study gave the PEITEs the framework for reflection and discourse, but this was in our own time and not ‘official’ professional learning time. Obrusnikova and Rattigan (Citation2016) reported that technology is time-consuming for educators as they are learning how the technology and applications work. This is further supported by van Hilvoorde and Koekoek (Citation2018) when they state that, ‘integrating content, pedagogy and technology demands an enormous amount of time, expertise and spaces for developing new skills'. However, the benefit of collaborating with a colleague to overcome the riskiness of not being fully competent was reassuring. Maria felt that the younger generation of PSTs might have TCK, which they might share in the lesson, ‘maybe some of the students (PSTs) will know, add more and can share their learning, as if any of those have good DL skills – they can do that as well’ (PM2). Sharon, in a lighter moment, acknowledged that the lesson may not run smoothly and that if problems occurred, they should treat them lightly, as the purpose was to enable the PSTs, ‘we are going to learn from each other as problems arise and there should be a laugh or two as well’ (PM1).

As the PEITEs went through the lesson with the PSTs, Maria noted that ‘maybe you need to get over this initial “digital learning” learning before you can apply the PE bit. Maybe you cannot expect them to do both together’ (PTM). As the PEITEs had to learn the technology, so too did the PSTs during their lesson, but at the same time, Sharon did not want planning and learning the digital technology activities taking away from the physical education tasks, ‘I was aware that I did not want them planning the film storyboard for too long … it would take away from their [skill] practice time’ (PTM).

Managing the technology

Although funding was provided to purchase the technology required (25 iPads, mac mini, storage and charging trolley and educational Apps) and the university recognised the importance of supporting technology integration in curricular areas, no administrative or on-site technological support was provided. ITEs’ inexperience in troubleshooting skills discouraged them from integrating technology, and PSTs felt discouraged as they watched ITEs fumble with the technologies (Bakir Citation2015). The findings show that during three meetings, there were twenty-three references to logistics alone. These references included discourse around ownership of the iPads. The PEITEs had to decide which groups within the class would use each iPad, how the PSTs would identify the iPad they were working on, and once this lesson was complete, how would their work be kept and not accidentally wiped or accessed by another class group. Other logistical references included ensuring charging of the iPads and where to conveniently and safely store the iPad trolley with access to electricity for charging. Managing the technology was a facet the PEITEs had not anticipated starting out on the study. Maria pointed to the difficulty in saving PSTs class work,

whatever work the students do next week on the iPads they must save it to somewhere – preferably to a folder or a file with their names on it. The whole idea would be that eventually we will have a folder on the server that they can … upload to. (PM2)

Managing the practicalities of being available to distribute and collect the iPads to allow the PSTs to use the iPads in their own time to work on their assignment following the research lessons were deemed not possible as pointed out during the planning meeting by Maria ‘we may not be around especially with you away that week and I will be teaching’ (PM2). Koh, Chai, and Tay (Citation2014) studied how the ecology of elementary school teachers in Singapore impacted the planning of technology-rich lessons in terms of intrapersonal, interpersonal, cultural/institutional and physical/technical components. They found that discussions about practical concerns hampered the teachers to talk about the pedagogical use of technology. Similarly, Boschman, McKenney, and Voogt (Citation2015) analysed design talk during the collaborative design of a technology-enhanced module for early literacy. They found that discussions on practical concerns (e.g. how to organise classroom activities) outweighed deliberations about existing priorities (knowledge, skills and beliefs) and external priorities (requirements set by others). These studies suggest that the practicality of teaching impacts and even dominates how teachers use their TPACK in educational practice.

Small practical issues around using the iPads arose as Sharon taught the lesson, and these had to be dealt with on the spot. These little issues, such as accessing the camera lens, had not been foreseen, ‘the one issue is with the survival cases, the camera is covered and we did not tell them to uncover it. It was only when they were having difficulty we told them to uncover it and you actually have to twist it around to hold’ (PTM). However, reflecting on the lesson, the PEITEs noted these iPad management issues and planned to include cues in future teaching to ensure time was not lost by PSTs trying to solve minor issues on their own.

Integrating the technology

Sharon was continually challenged on how to achieve a balance between achieving the outcomes of the module for PSTs and becoming absorbed by technical elements on the integration of technology to achieve the outcomes such as the pedagogy of technology in physical education. Sharon had to be reminded by Maria to keep focussed on using the technology in physical education to enhance PSTs and children’s learning, as Sharon tried to rationalise ‘what [time] can we afford in our modules to give to the actual technical side of it?’ (PTM). Maria, while thinking out loud, proposed that maybe learning the technology was ‘something they do in their own time, additional time, not in class but we need to be sure they are able to do it (use the technology) … ’ (PTM).

Following the lesson, Maria spoke about the PSTs’ learning and how they were able to integrate the technology, ‘the idea would be that they can transfer the knowledge gained here to the classroom’ while Sharon pointed out ‘they could see checklists and an iPad as tools to assess for the teacher and the pupil’ (PTM). It was noted that Sharon was becoming distracted at times with the technological issues and needed to keep focus on the goals of the lesson and the aims of the module. However, according to Niess (Citation2005), learning activities should take into account student needs, the content being taught and other contextual variables. Perhaps these PSTs required more technological support, as Maria points out, ‘do they need input from us [The PE Team] or DL [Digital Learning Team]?’ (PTM). This shaped the PEITEs practice because they had to consider how best to support the PSTs in their learning of technology (TCK) as well as ensuring their physical education PCK. The PEITEs needed to ascertain whether it was their role as PEITEs to facilitate the PSTs’ technological learning. However, they were anxious about their ability to meet these demands as they did not feel competent in delivering TCK. The PEITEs agreed that they might have to engage in this type of pedagogy for quite a while in order for themselves and the PSTs to become adjusted to a new approach, but they also found themselves concerned that they may not be able to do this and keep up with the rigorous pace of current university and technological change.

Mohnsen and Lamaster (Citation2013) suggested that teacher education programmes should integrate technology into all courses rather than isolating the skills to technology courses. Rosenthal and Eliason (Citation2015) went further and believed that all staff should have TCK and model it as part of the teaching and learning process. Young people should have to move beyond passive use of technology towards active use in collaborative and creative endeavours (McGarr and McDonagh Citation2021). PEITEs should be able to develop an understanding of why, when and how to use technology for learning and the ability to model and deliver technology-infused curricula, pedagogy and assessment as pointed out by Maria, ‘now that they know what they are looking for [in PE] … and now that they know what the iPads can video and do … they need to link the two’ (PTM). However, despite the challenges, linking the use of digital technologies with the purposes of physical education pedagogy was beginning to happen. Integration of technology was happening through TPCK leadership (Thomas et al. Citation2013), as displayed by the PEITEs. The PSTs in this study were beginning to use the iPads for assessment purposes; according to Maria, ‘it [the iPads] may not improve their own (PSTs) fundamental movement skills but it gives them a better awareness of them … It’s really to observe movement to provide feedback to enhance learning’ (PM2). In integrating the technology, the PSTs became aware of their own ability to perform, demonstrate or model fundamental movement skills from viewing themselves on the video clips as observed by Maria,

could they observe students; … it was using it for observation purposes linked to assessment … we have learned today they did [assess] because when they started videoing they were not sure what they were doing was the right thing. They had to go back to their notes and FMS book because they felt that what they videoed did not look like what they should have [done]’. (PTM)

Conclusions

This self-directed professional learning experience enhanced the PEITEs’ TPACK using iPads in this particular physical education lesson and, subsequently, the module. The findings related to learning and managing the technology (TCK), and integrating the technology (TPACK) into a physical education lesson. Lesson study was chosen, in this case, as a scaffold for self-directed learning. The PEITEs planned the lesson carefully, reflected during and after the lesson towards improving practice; however, this is only the beginning of their work. As Loughran (Citation2006, 30) points out, ‘the very act of teaching churns up the waters of learning and creates situations that, although perhaps able to be anticipated, are not able to be fully addressed until they arise in practice’. The development of this new practice of introducing iPads came out of a desire to improve and address the DES (Citation2015) vision of incorporating technology into teaching. It came about through adapting, adjusting and developing their practice as a result of teaching, reflecting on teaching and learning from teaching. The PEITEs used their initiative, acted as a sounding board for each other and the reflective meetings generated further support and enthusiasm for this professional learning.

Time for development activities, such as reflection and conversations with colleagues, is identified as a barrier to the professional development of teacher educators (Smith Citation2001). Koster and colleagues (Citation2008) report that reflection is not a prominent teacher educator professional development activity, and although reflection is identified as a valued practice, it seems that structures to help teacher educators to prioritise reflective practices are lacking. This suggests that a better understanding is needed of how teacher educators can be supported to integrate reflection and conversations on pedagogical practices with colleagues into professional learning experiences (Koster et al. Citation2008; Loughran Citation2014).

The findings indicate that lesson study is a useful framework to begin and guide the process of improving teaching through self-directed inquiry. Going through the iterative process of inquiry, reflection, and refinement and negotiating existing constraints within the lesson to create conditions necessary for iPad integration was insightful. Refining this lesson within the overall module, including course objectives, methods and materials, will be instrumental to continuous improvement and the evolution of the PEITEs’ practice over time. While the lesson study provided a useful and beneficial framework for the PEITE’s professional learning, as this study only provided the data from one lesson study cycle focussing on the PEITEs there was no data from the PSTs considered. Including this data was beyond the scope of this paper, but PSTs digital competency skills might provide further evidence for the introduction of iPads in the lesson (McGarr and McDonagh Citation2021). The implications for ‘next lesson’ in the lesson study cycle is to continue to work collaboratively, the individual contributions made strengthen the collaboration, as the PEITEs continue to learn the technology, they have each other to query technological problems. The PEITEs have agreed to take risks and talk about them to keep challenging their learning.

This study demonstrated that the PEITEs struggled to remain focussed on the learning outcomes of the physical education lesson and module as they were grappling with their own TPACK and PSTs’ physical education pedagogical content knowledge to create a TPACK rich environment in physical education. Looking back at the initial technology integration effort, the PEITEs realised that it was flawed. Hands-on activities were not emphasised enough, and technological knowledge was over-emphasised. It was clear, however, that a hands-on, problem-based approach would better prepare the PSTs to use technology and equip them with the necessary skills and confidence needed to integrate technology into physical education lessons.

Research indicates that ITEs trying to integrate technology (including iPads) need to develop a critical disposition toward technology (Rosenthal and Eliason Citation2015) and determine and develop TPACK (Cengiz Citation2015). It implies that ITEs should be able to develop an understanding of why, when and how to use technology for learning and the ability to model and deliver technology-infused curricula, pedagogy and assessment. For the PEITEs, this study was ‘step 1’ in an ongoing change process. They realised that they have to find time to reflect on their teaching and consider self-directed learning while also meeting the other demands of university teacher education. How the PEITEs conceived integration of iPads will impact further technology integration by both of them. They planned to use additional Apps in other physical education modules underpinned by the TPACK model (Mishra and Koehler Citation2006). The iPad was slowly becoming a ‘teaching tool’ rather than an ‘add on’ (Jones Citation1980).

Recommendations for change in relation to integrating the use of iPads in teaching include (1) universities allocate time in workloads for ITEs to practice using iPads and other technological devices as well as providing formal professional development time and management support (2) university staff consider establishing a learning community of interested PEITEs with few rather than more group members and perhaps with PEITEs of similar ability and experience to allow situated and shared learning (3) university staff take risks and integrate iPads into their teaching to improve their TPACK and that of their PSTs (Cengiz Citation2015).

The findings of this study have given the PEITEs a better understanding of the underlying challenges that affected iPad implementation in primary physical education teacher education. These findings will impact the redesign of this particular lesson and module, but they will also have an impact on the learning experiences of the PSTs as the PEITEs weave iPads into other physical education lessons and modules. Advice to others embarking on a similar professional learning journey is to start small and take time learning, managing and integrating digital technology and, while doing so, seek optimal solutions rather than perfect solutions (Simon Citation1969).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susan Marron

Susan Marron is an Assistant Professor in the School of Arts Education and Movement in the Institute of Education at Dublin City University where she teaches in the area of Primary Physical Education. Her research interests include inclusion in physical education and teacher education.

Maura Coulter

Maura Coulter is Associate Professor in the Institute of Education at Dublin City University where she teaches in the area of Primary Physical Education. Maura is also the Associate Dean for Research at the Institute of Education and her research interests include meaningful physical education, teacher education and professional identity and professional development.

References

- Armour, K., G. Evans, M. Bridge, M. Griffiths, and S. Lucas. 2017. “Gareth: The Beauty of the IPad for Revolutionising Learning in Physical Education.” In Digital Technologies and Learning in Physical Education: Pedagogical Cases, edited by A. Casey, V. A. Goodyear, and K. M. Armour, 1st ed, 213–230. Oxon: Routledge.

- Bakir, N. 2015. “An Exploration of Contemporary Realities of Technology and Teacher Education: Lessons Learned.” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 31 (3): 117–130.

- Borko, H. 2004. “Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain.” Educational Researcher 33: 3–15.

- Boschman, F., S. McKenney, and J. Voogt. 2015. “Exploring Teachers’ Use of TPACK in Design Talk: The Collaborative Design of Technology-rich Early Literacy Activities.” Computers & Education 82: 250–262.

- Butler, D., K. Marshall, and M. Leahy. 2015. Shaping the Future: How Technology Can Lead to Educational Transformation, 1st ed. Dublin: Liffey Press.

- Cengiz, C. 2015. “The Development of TPACK, Technology Integrated Self-efficacy and Instructional Technology Outcome Expectations of Pre-service Physical Education Teachers.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 43 (5): 411–422.

- Ciampa, K., and T.L. Gallagher. 2013. “Professional Learning to Support Elementary Teachers’ Use of the IPod Touch in the Classroom.” Professional Development in Education 39 (2): 201–221.

- Clarke, A., and G. Erickson. 2006. “Teacher Inquiry: What’s Old Is New Again!.” BC Educational Leadership Research 1, 44–68.

- Cosgrove, J., D. Butler, M. Leahy, G. Shiel, L. Kavanagh, and A.M. Creaven. 2014. The 2013 ICT Census in Schools Summary Report. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2008. ICT in Schools. Inspectorate and Evaluation Studies. Dublin: DES.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2015. Digital Strategy for Schools 2015-2020: Enhancing Teaching, Learning and Assessment. Dublin: DES.

- Dündar, H., and M. Akçayır. 2014. “Implementing Tablet PCs in Schools: Students’ Attitudes and Opinions.” Computers in Human Behavior 32: 40–46.

- Eberline, A.A., and K.A.R. Richards. 2013. “Teaching with Technology in Physical Education.” Strategies: A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators 26 (6): 38–39.

- Eivers, E. 2019. Left to Their Own Devices: Trends in ICT at Primary School Level. Cork: Irish Primary Principals Network.

- Elliott, J. 2019. “What is Lesson Study?” European Journal of Education 54 (2): 175–188.

- Fielding, M., S. Brag, J. Craig, I. Cunningham, M. Eraut, S. Gillinson, M. Horne, C. Robinson, and J. Thorp. 2005. Factors Influencing the Transfer of Good Practice. Sussex: University of Sussex and Demos DFES Publications.

- Graham, G., S.A. Holt/Hale, and M. Parker. 2010. Children Moving a Reflective Approach to Teaching Physical Education. 8th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Hargreaves, A., and M. Fullan. 2012. Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Haynes, J., and J. Miller. 2015. “Preparing Pre-service Primary School Teachers to Assess Fundamental Motor Skills: Two Skills and Two Approaches.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 20 (4): 397–408.

- Hung, H.C., S. Shwu-Ching Young, and K.-C. Lin. 2018. “Exploring the Effects of Integrating the iPad to Improve Students’ Motivation and Badminton Skills: A WISER Model for Physical Education.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 27 (3): 265–278.

- Jones, R. 1980. “Microcomputers: Their Uses in Primary Schools.” Cambridge Journal of Education 10 (3): 144–153.

- Kirkwood, A., and L. Price. 2014. “Technology-enhanced Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: What Is ‘Enhanced’ and How Do We Know? A Critical Literature Review.” Learning, Media and Technology 39 (1): 6–36.

- Knowles, M.S. 1975. Self-directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. New York, NY: Cambridge Book Co.

- Koehler, M., and P. Mishra. 2008. “Introducing TPACK.” In AACTE Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge, edited by Committee on Innovation and Technology, 3–30. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Koh, J., C. Chai, and L. Tay. 2014. “TPACK-in-action: Unpacking the Contextual Influences of Teachers’ Construction of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK).” Computers & Education 78 (September): 20–29.

- Koster, B., J. Dengerink, F. Korthagen, and M. Lunenberg. 2008. “Teacher Educators Working on Their Own Professional Development: Goals, Activities and Outcomes of a Project for the Professional Development of Teacher Educators.” Teachers and Teaching 14 (5–6): 567–587.

- Lambert, J., and Y. Gong. 2010. “21st Century Paradigms for Pre-service Teacher Technology Preparation.” Computers in the Schools 27 (1): 54–70.

- Lee, M.-H., and C.-C. Tsai. 2008. “Exploring Teachers’ Perceived Self Efficacy and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge with Respect to Educational Use of the World Wide Web.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 38: 1–21.

- Leight, J., D. Banville, and M.F. Polifko. 2009. “Using Digital Video Recorders in Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 80 (1): 17–21.

- Lewis, C., R. Perry, and J. Hurd. 2009. “Improving Mathematics Instruction Through Lesson Study: A Theoretical Model and North American Case.” Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education 12 (4): 285–304.

- Loughran, J. 2006. Developing a Pedagogy of Teacher Education: Understanding Teaching and Learning about Teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Loughran, J. 2014. “Professionally Developing as a Teacher Educator.” Journal of Teacher Education 65 (4): 271–283.

- Marron, S., F. Murphy, and M. Coulter. 2018. “Primary Teachers ‘Fit’ to Enhance Wellbeing of Children.” In Ireland's Yearbook of Education 2018-2019, edited by B. Mooney, 38–42. Education Matters.

- McGarr, O., and A. McDonagh. 2021. “Exploring the Digital Competence of Pre-service Teachers on Entry Onto an Initial Teacher Education Programme in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (1): 115–128.

- Mishra, P., and M.J. Koehler. 2006. “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge.” Teachers College Record 108 (6): 1017–1054.

- Mohnsen, B., and K. Lamaster. 2013. “Technology: Attitudes, Efficacy, and Use by Practicing Physical Education Teachers.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 69 (6): 21–23.

- National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. 1997. Technology and the New Professional Teacher. Preparing for the 21st Century Classroom. New York, NY: AT&T Foundation.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2004. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) Integration of ICT in the Primary School Curriculum: Guidelines for Teachers (2004). Dublin: NCCA.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2007. ICT Framework: A Structured Approach to ICT in Curriculum and Assessment. Revised Framework. Dublin: NCCA.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2020. “Draft Primary Curriculum Framework for Consultation.” Dublin: NCCA.

- Niederhauser, D., and S. Perkmen. 2010. “Beyond Self-efficacy: Measuring Preservice Teachers’ Instructional Technology Outcome Expectations.” Computers in Human Behavior 26 (3): 436–442.

- Niess, M. L. 2005. Preparing teachers to teach science and mathematics with technology: Developing a technology pedagogical content knowledge. Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (5): 509–523.

- Obrusnikova, I., and P.J. Rattigan. 2016. “Using Video-based Modeling to Promote Acquisition of Fundamental Motor Skills.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 87 (4): 24–29.

- Reychav, I., and D. Wu. 2014. “Exploring Mobile Tablet Training for Road Safety: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective.” Computers & Education 71: 43–55.

- Rosenthal, M., and S.K. Eliason. 2015. “‘I Have an iPad. Now What?’ Using Mobile Devices in University Physical Education Programs.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 86 (6): 34–39.

- Saito, E. 2012. “Key Issues of Lesson Study in Japan and the United States: A Literature Review.” Professional Development in Education 38 (5): 777–789.

- Schuck, S., P. Aubusson, M. Kearney, and K. Burden. 2013. “Mobilising Teacher Education: A Study of a Professional Learning Community.” Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development 17 (1): 1–18.

- Semiz, K., and L.M. Inze. 2012. “Pre-service Physical Education Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge, Technology Integration Self-efficacy and Instructional Technology Outcome Expectations.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 28 (7): 1248–1265.

- Shulman, L. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57: 1–23.

- Simon, S. 1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. Book, Whole. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Smith, S. 2001. “Teacher Education.” Journal of Special Education Technology 16: 55–56.

- Strauss, A., J.M. Corbin, and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. New York, NY: SAGE Publications.

- The Teaching Council. 2011. Policy on the Continuum of Teacher Education. Dublin: Teaching Council.

- Thomas, T., M. Herring, P. Redmond, and S. Smaldino. 2013. “Leading Change and Innovation in Teacher Preparation: A Blueprint for Developing TPACK Ready Teacher Candidates.” TechTrends 57 (5): 55–63.

- van Hilvoorde, I., and J. Koekoek. 2018. “Next Generation PE: Thoughtful Integration of Digital Technologies.” In Digital Technology in Physical Education, 1st ed. 1–16. London and New York: Routledge.

- Verhoef, N.C., F. Coenders, J.M. Pieters, et al. 2015. “Professional Development Through Lesson Study: Teaching the Derivative Using GeoGebra.” Professional Development in Education 41 (1): 109–126.

- Waldron, F., J. Smith, M. Fitzpatrick, and T. Dooley. 2012. Re-imagining Initial Teacher Education: Perspectives on Transformation, 1st ed. Dublin: Liffey Press.

- Willems, I., and P. Van den Bossche. 2019. “Lesson Study Effectiveness for Teachers’ Professional Learning: A Best Evidence Synthesis.” International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 8 (4): 257–271.

- Woods, A.. 2019. “Using Digital Technologies to Support Inclusion in the Mainstream Classroom.” REACH: Journal of Inclusive Education in Ireland 32 (2): 102–124.