ABSTRACT

Knowledge of symbols, which can be influenced by school ethos, informs identity construction in primary school children. This study aimed to explore Gaelscoil (Irish-medium) and English-medium primary school children’s familiarity with Irish and European symbols. Thirty 9–12-year-old children in Ireland participated in this study; 15 from two Irish-medium and 15 from an English-medium primary school. A draw-and-tell data collection design was used and qualitative data was analysed using the constant comparative method. Results indicate children from both school types shared a number of Irish symbols, namely Irish emblems, Irish mythology, sports and material aspects of culture. Irish-medium primary school children had two further Irish symbol categories, the past as a symbol and physical characteristics of Ireland. European symbols shared across children from both school types included signifiers of the European Union (EU), monetary symbols and European countries. The Irish-medium primary school children had two further categories, Europe through an Irish lens and European cuisine, while the English-medium children had one further category, sport. The results suggest that by middle childhood, children in both school types have knowledge about a number of symbols associated with both national and European identities. Implications for future research are discussed.

Symbols play an important role in national identity construction. Flag, emblems and mottos serve as important visual aids in the nation building and maintenance process (Dautel et al. Citation2020; Kolstø Citation2006). As Butz (Citation2009) noted, ‘[national symbols] are conceptual representations of group membership’ (780). The daily display of national symbols, such as flags, continually reinforces the nation state in the minds of its citizens, increasing identification with one’s nationality. For example, research on the role of national symbols in identity construction has found that symbolic involvement is associated with higher scores on measures of national identification (Schatz and Lavine Citation2007). Although national flags are intuitively symbolic, a similar sense of national identity can be evoked through cultural symbols such as music, sport, landscapes and language (Bechhofer and McCrone Citation2013).

Cultural symbols are thought to be particularly salient to children. Children’s national identity construction has been found to centre around these ‘tangible characteristics’ of national culture (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). Children as young as three demonstrate an awareness of cultural and political symbols (Connolly, Smith, and Kelly Citation2002), and that knowledge increases through the primary school years (Taylor, Dautel, and Rylander Citation2020). In Ireland more specifically – Social, Personal and Health Education Curriculum (SPHE) curriculum for fifth and sixth class includes a unit on ‘developing citizenship’ which aims to teach children about the European Union, the role of the European Parliament in shaping Irish laws and the connectedness of EU countries (Government of Ireland Citation1999). Prior to fifth class, there is no mention of the EU in the SPHE curriculum. It is possible that the deeper awareness of European identity in older primary school children may in part stem from the school curriculum. Using a questionnaire of typical or cliché signifiers of Irishness, Moffatt (Citation2011) found that young Irish people considered the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), the Irish soccer team, St Patrick’s Day, the Catholic Church, and particularly relevant to schooling, the Irish language, learning/understanding Irish history, as important symbols of Irishness. Through emulating the symbols of traditional nation-states, the EU has attempted to manufacture a sense of belonging to the European community (Bruter Citation2003).

European institutions have long since recognised the necessity of shared symbols in promoting a singular European identity. For example, the European flag and anthem, Europe Day, the Euro, European licence plates and the shared burgundy passport are carefully constructed visual identifiers of unity. A cross-country study on school children’s visualisations of Europe found the EU flag and Euro currency to be prominent and recurring signifiers of Europe (Mason, Richardson, and Collins Citation2012). The Irish State and EU institutions recognise the power of symbols in the identity construction process, with both using the education system as a key purveyor of their messages.

Social identity development theory

Social identity development theory (SIDT; Nesdale Citation2004) outlines how children acquire knowledge of and attachment to relevant social groups. More specifically, SIDT outlines the importance of children’s’ social contexts, including schools, in shaping the content and influence of such identities (Nesdale Citation2017; Nesdale and Flesser Citation2001). Across middle childhood, SIDT describes different phases of social identity; by age seven, it is postulated that children have developed a sense of group awareness and preference. Consistent with this theory, children have a sense of their national identity by age 5 that is refined throughout middle childhood (Barrett Citation2007), while European identity emerges between the ages of 6 and 10 (Barrett Citation1996). SIDT has been applied cross-culturally to understand different ethnic groups (Merrilees et al. Citation2018; Shamoa-Nir et al. Citation2020; Taylor, Dautel, and Rylander Citation2020; Tomovska Misoska et al. Citation2020); to the best of our knowledge, however, it has not yet been used to study both national and supra-national identities (e.g. European) in children.

The European Union

Since its foundation as the European Economic Community in 1957, the European Union (EU) worked to bring peace, as well as economic and political stability, to a region plagued by conflict. Reflecting the relative success toward this primary aim, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. The political landscape of European Union member states has shifted dramatically in the intervening years. Brexit and the rise of Eurosceptic populist and far-right parties have called into question the success of the European Project. Critics and proponents alike have cited a lack of European identity and the strength of distinct national identities as contributing factors (Kølvraa Citation2016). Despite these trends, the 2019 Eurobarometer survey indicates that public support for the EU is notably higher in Ireland than in other member states (European Parliament Liaison Office in Ireland Citation2019).

Originally conceived as an institution based on shared economic prosperity, over the last number of decades, the European Union has made a concerted effort to be seen as a social and cultural community (Philippou Citation2005). The development and adoption of shared European symbols has played an important role in this process. For example, free movement of people, a common/single market and a unified currency are some of the key policies and symbols that define EU membership and has been incorporated by member states as part of school curricula. As a shared European identity is crucial for the continued success of the European Union, and national identity has been cited as a barrier to this (Carey Citation2002), the current study compares primary school type on children’s knowledge of national and European symbols. In Ireland, both Irish and English are official languages, although the primary language is English and Irish is taught in all state recognised schools. Offering an alternative to English as the primary language of instruction, Gaelscoileanna are Irish language-medium primary schools.

Identity construction and the Irish education system

In constructing their identity and sense of self, children not only rely on their families and peers but also schools, curricula and teachers play an equally important role (Barrett and Oppenheimer Citation2011; Haywood and Mac an Ghail Citation1996). Symbols and activities in school can have a profound influence on children’s identities. Traditional music, sports, language, dance and religion, promoted as part of the school curriculum, are tangible expressions of one’s culture and play a role in forming national identity (Scourfield et al. Citation2006). Irish children often use the history of their country as a foundation on which to build their national identity (Scourfield et al. Citation2006); through qualitative research and international case studies, Scourfield and colleagues found that children creatively identify with place and nation, including content learned in schools. The Irish history curriculum provides children with a carefully constructed national narrative, one designed to foster common values and promote a ‘national ethos’ (Magennis Citation2016). That is, school history content, symbols and practices influence and shape the formation of national identities. Sport also can play a significant role in fostering a sense of national identity, while also providing an appropriate outlet for nationalistic feelings (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). GAA sports, such as hurling, camogie and Gaelic football, are incorporated into the primary school physical education curriculum.

Gaelscoileanna are Irish language-medium primary schools (Mac Giolla Phádraig Citation2003). They immerse children not only in the Irish language but also the culture, history and tradition of Ireland both past and present. Parents may choose to send their children to Gaelscoileanna for both language and non-language reasons, such as increased tolerance and self-esteem (Gaeloideachas Citation2019). As school ethos has been found to influence children’s construction of an Irish national identity, it is probable that the unique school environment of a Gaelscoil will shape children’s national identity in line with the school’s values and focus (Waldron and Pike Citation2006).

As part of the EU, Ireland has also responded to encouragement for member states to include a ‘European dimension’ in their curriculums (Ryba Citation1995); educational initiatives are a means of promoting European identity and citizenship. The EU has also promoted a number of programmes across several countries aimed at enhancing European identification including Comenius, Erasmus and Leonardo Da Vinci programmes. In Ireland, the Blue Star Programme, aimed at primary school pupils, is designed to teach children about other European countries, cultures and the European Union (Blue Star Programme Citationn.d.). These various educational initiatives reflect the role of school systems in influencing the content of identity construction, both as Irish and European, in Ireland. In addition to the curriculum, school factors have been found to influence European identification (Agirdag, Huyst, and Van Houtte Citation2012). For example, even controlling for family socio-economic status, schools with a higher number of working-class pupils had a weaker sense of European identity; this finding, in part, could be due to lower opportunities for school peers to travel to other European countries (Agirdag, Huyst, and Van Houtte Citation2012). Thus, even the same curriculum applied in different school types may differentially shape children’s European identity.

Current study

Using the lens of SIDT, the current study explores the symbolic content of children’s national and European identities during the primary school years in Ireland. In particular, we focus on the symbolic content of Irish and European identities that can be influenced by the Irish education system. Using a draw-and-tell design, we compare the content and explanations of children who attend Gaelscoileanna and children who attend an English-medium primary schools. This exploratory approach allows for the emergence of new symbols, content and ideas, as well as rich descriptions from the children themselves.

Methods

Research design

Drawings are a method of data collection which is non-invasive and familiar to children. The draw-and-tell method ensures that children’s rights and autonomy are maintained (Driessnack Citation2006; Driessnack and Gallo Citation2013) and often generates deeper discussion than interviews alone (Merriman and Guerin Citation2006). Following the drawing tasks, brief interviews were conducted where the children explained each of the drawings they completed; explanations were recorded and transcribed verbatim. These interviews helped to unpack their understanding of the images (O'Toole, Joseph, and Nyaluke Citation2020).

Participants

Three schools agreed to participate, two Irish-medium and one English-medium primary school in a broader project of the Author Identifying Lab. None of these schools were on the Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) list; all of the schools were mixed gender ranging in size from approximately 200–600 pupils. All consent materials and study tasks were conducted in English. Principals provided consent for their primary schools to participate. Parental information letters and consent forms were sent home to all students in first to sixth class; 33.45% from the Irish-medium and 32.67% from the English-medium school were returned with consent. Out of 143 children who received parental consent, 30 children aged 9–12 and born in Ireland were randomly selected to participate in this study; 15 attending Irish-medium school (M = 10.2, SD = 1.1, 53% female) and 15 attending the English-medium school (M = 10.6, SD = 1.1, 60% female). Children also provided assent prior to participating; no children refused to participate.

Materials

Two A4 sheets of white paper, one with the heading ‘Irish Symbols’ and one with the heading ‘European Symbols’, along with colouring pencils, markers and crayons were provided. The researchers used an iPad with the Qualtrics programme to record each child’s assent. If children seemed stuck or asked for clarification, the researchers used a series of probes to generate ideas and confidence in engaging in the task (Appendix). A digital audio recorder was used to record the child’s explanations of their drawings.

Procedures and data collection

Children were interviewed in an unoccupied room in each of the schools. The researcher followed a script in order to ensure consistency across interviews. Following the draw-and-tell technique (Driessnack Citation2006; Driessnack and Gallo Citation2013; see also O'Toole, Joseph, and Nyaluke Citation2020), children were informed that they were here to ‘draw some fun pictures,’ and asked if they agreed to take part. To ensure the child was comfortable with the researcher and understood the task, children were asked to ‘draw their favourite animal’ and describe their drawing. Children were then prompted to draw ‘things’ that they associated with Ireland and with Europe; which label they were presented with first was randomly assigned to control for potential order effects. When children finished each drawing, the researcher prompted explanation, for instance ‘What do you associate with Ireland and being Irish?’ Upon completion of the study, children were thanked and given a sticker. Ethical approval for this study was granted by Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis procedures

Data analysis followed the constant comparative method (Maykut and Morehouse Citation1994; Taylor et al. Citation2011) including an ‘audit trail’ of the analysis process (Reidy et al. Citation2015). First, the children’s descriptions of their drawings were carefully transcribed, allowing the researcher to become familiar with the material. The data were then ‘unitised’ into ‘chunks of meaning’ and labelled with a descriptor and the participant ID. Second, in the ‘process of discovery’ stage, the researcher identified broad themes, ideas and concepts from the initial review of the data (Taylor and Bogdan Citation1984). Third, in the ‘inductive category coding’ stage, the researcher examined the unitised data for each category and determined whether it fit the first provisional category using the ‘looks like’ or ‘feels like’ criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985). Fourth, the ‘refinement of categories’ stage involved writing ‘rules for inclusion’ for each category. A rule of inclusion described the meaning of the category (Taylor et al. Citation2011). After all of the units of data were categorised, the researcher undertook the fifth stage of the constant comparative method, ‘exploration of relationships and patterns across categories’. Finally, the differences and similarities that emerged across the categories were analysed, focusing on a ‘convergence of themes’ (Taylor et al. Citation2011).

Results

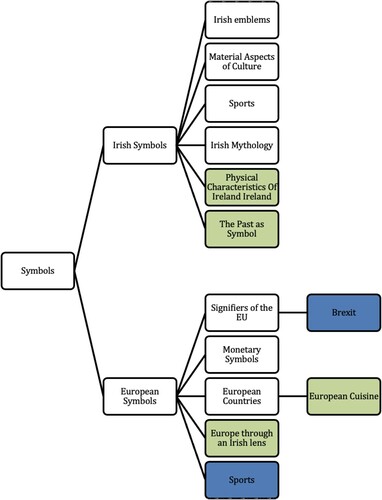

Children’s drawings included national symbols of Ireland, official symbols of Europe and the EU, as well as cultural and commercial symbols of both Ireland and Europe. depicts the overall themes and categories that emerged from the drawings. The following sections outline the Irish symbols followed by the European symbols. Within each section, the results are described by the school type, i.e. Irish-medium and English-medium; first the themes that were shared by children in both school types, followed by unique themes from only one of the two schools.

Figure 1. Concept map of the overall themes and categories that emerged in the drawings. A white background indicates categories that were found in both school types, light grey/green background indictates categories found only in the Gaelscoileanna, and dark grey/blue background indicates categories only found in the English-langauge school.

Irish symbols

When asked to draw things associated with Ireland, children in both school types created images depicting Irish emblems, Irish mythology, material aspects of culture and sport; children attending the Irish-medium primary schools also drew and described additional images not found in the English-medium primary school drawings: physical characteristics of Ireland and the past as a symbol.

Irish emblems – Irish-medium

The Irish-medium primary school pupils demonstrated a keen knowledge of Irish emblems, such as national flag, shamrock and harp.

National flag

The children’s reasonings for drawing the Irish flag was matter of fact (). As one child put it: ‘it’s the Irish flag and I think it’s the best symbol I’ve done because it's literally the Ireland flag’ (female, age 9). One child went further with their descriptions of the flag, attempting to explain the meaning behind the tricolour: ‘The green is for Ireland, the white is for peace and the orange is for something else that I don’t know’ (female, age 11). This child has a cursory understanding of the meaning behind the Irish flag. Although she identifies the white as symbolising peace, she fails to explain the purpose of symbolising peace between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants specifically. Others described the flag as an important signifier of nation and nationality: ‘We can show other countries that we’re Irish and it’s Ireland’ (male, age 11). This child is inadvertently highlighting the us/them aspect of social identity and how group membership can be symbolised.

Figure 2. Drawings for each of the themes that emerged for Irish symbols across both school types; numbers in parentheses indicate the number of children who included a symbol in these theme: G = Gaelscoileanna, E = English-langauge school. Example images are shared in both columns when drawn by participating children.

Shamrock

Two children drew the shamrock as symbol of Ireland due to their abundance: ‘That’s the Irish symbol like a shamrock the show that that’s Ireland cause lots of them grow around Ireland’ (male, age 10). This child’s answer is basic, but represents the sometimes simple way children can form meaningful associations. Two other children mentioned St Patrick when discussing their shamrock drawing. St. Patrick is thought to have brought Christianity to Ireland in around A.D. 432. Irish legend says he used the Shamrock in his teachings to symbolise the Holy Trinity. However, this story did not feature in any of the children’s interviews. Children alluded to St Patrick in their answers but made no attempt to explain why the shamrock was associated with the Saint: ‘Because of St Patrick’s Day, and … because he like represented Ireland a bit’ (female, age 11).

Harp

One child identified the harp as a symbol of Ireland. In a similar way to the Irish flag, his explanations as to why he chose the harp as a symbol were brief and to the point: ‘Number two is a harp, it’s the symbol of Ireland’ (male, age 10). The Irish-medium primary school children’s drawings of Irish symbols included the national emblems of Ireland and the Irish flag, indicating an awareness of the official signifiers of Ireland and Irishness.

Irish emblems – English-medium

In a similar way to the Irish-medium primary school children, the majority of the English-medium primary school children included Irish emblems in their drawings.

National flag

Children who drew the Irish flag described their drawings in a similar matter-of-fact way to the Irish-medium primary school children: ‘That’s the Irish flag so yeah that’s the flag that represents Ireland’ (male, age 12). None of the children offered a further explanation of their drawing of the flag beyond this type of basic statement.

Shamrock

The shamrock was also common image drawn as symbol of Ireland. Three children mentioned St Patrick in their interviews, but there was no mention of the Holy Trinity or the shamrock’s religious origins: ‘It’s a shamrock … because like St Patrick like if like if you go to a St Patrick’s Day parade you see shamrocks’ (male, age 12). However one child had a vague recollection of the story but could not quite put all of the pieces together:

I picked the shamrock because there are a lot of shamrocks in Ireland and from like I think it was St Patrick or something and he picked up the shamrock and said like something I forget what he said. (Female, age 11)

Harp

The harp was drawn as a symbol of Ireland by three children. However, their interviews yielded very different reasons as to why they chose it. One child emphasised the harp as an Irish instrument: ‘A harp because it’s em it’s Irish em instrument [sic] and like a lot of Irish people play it’ (female, age 11). Another associated it with Irish sports: ‘Because it’s always on like the crests and stuff for like Irish jerseys anall [sic]’ (male, age 11). For others around the world, the harp is not as synonymous with Ireland as the shamrock or Irish flag may be. However, for several children, it remains a signifier of Ireland.

Irish mythology – Irish-medium

Ireland has a rich history of myths, legends and folklore which are part of its national identity. As stories are told and retold, they change, evolve and take on new meaning.

Banshee

‘The Banshee’ is a well-known Irish legend, a supernatural figure whose scream is an infamous omen of death. One child drew the Banshee and identified the myth in her interview: ‘The Banshee, she mostly originates from Ireland. Em well she walks around like dead bodies during the war in the shape of a crow’ (female, age 12). This child’s description of the Banshee may incorporate other tales of Irish folklore such as that of Badhbh, a Celtic war goddess who is said to take the form of a crow and is often described as wailing.

Leprechaun

The Leprechaun was another mythical Irish creature drawn by the children. Leprechauns have been a part of Irish folklore for centuries, although their image has changed as they entered mainstream popular culture and were co-opted by brands, movies and events. For these children, they are a St Patrick’s Day motif. As one child noted: ‘The Leprechaun em from the story like St Patrick’ (female, age 12) while another explained: ‘I’ve heard about Leprechauns and about the rainbow at the end of the rainbow [sic] with their pot of gold … because they’re kind of like St Patrick as well’ (female, age 9). These Irish-medium primary school children demonstrate a knowledge of Irish mythology which has evolved as some aspects of the story are forgotten and new associations are forged. However, Irish mythology remains a national identifier and symbol for these children.

Irish mythology – English-medium

Irish myths and legends were also seen in a number of English-medium primary school children’s drawings of Irish symbols.

Leprechaun

In their interviews, the children demonstrated different associations with the Leprechaun than those of the Irish-medium primary school children. One child linked their drawing to cultural stereotypes: ‘Leprechaun … eh because like em like em other people around the world call Irish people Leprechauns’ (male, age 12). The majority of children who drew a Leprechaun emphasised the rainbow and pot of gold as well as the mythical aspect of the story: ‘Leprechaun because like like [sic] the rainbow it’s like we always have rainbows in Ireland there’s always gonna like they always say that there’s a Leprechaun at the end of the rainbow’ (female, age 11) and ‘A Leprechaun … it’s just a myth in Ireland’ (male, age 10). In contrast to the Irish-medium primary school children, there was no reference to St Patrick’s Day in these children’s explanation of the Leprechaun.

Oisín and Tír na nÓg

One child drew a book of Irish stories and described in detail the story of Oisín and Tír na nÓg. When explaining her drawing she said: ‘cause you usually hear a lot of old stories and you don’t usually hear as much stories is that in different countries’ (female, age 9). For that child, Irish myths and legends are unique to Irish culture and make them an especially important symbol of Ireland.

Material aspects of culture – Irish-medium

Irish-medium primary school children’s drawings included a number of material aspects of culture, food and drink which they felt were characteristically Irish and thus symbolised Ireland.

Potato

The potato has long been synonymous with Irish food and has made its way into the national consciousness as a signifier of Ireland. Three children drew potatoes and in their interviews identified the potato as simply being Irish: ‘cause the potato are just an Irish thing that you can grow in Ireland’ (male, age 10) and ‘spuds that are Irish’ (male, age 10).

Tayto crisps and guinness

As advertising and branding became a part of daily life, a number of Irish products took on a type of symbolism: ‘Tayto [a popular brand of crisps] because it kind of originates from Ireland’ (female, age 11), ‘A packet of Taytos … cause they’re made in Ireland’ (male, age 10) and ‘Guinness … because whenever I see an ad on TV or something I just remember Ireland’ (female, age 11). For these children, Tayto crisps and Guinness have morphed from brand to Irish icon.

Material aspects of culture – English-medium primary school

English-medium primary school children’s drawing included the same material aspect of culture, Guinness.

Guinness

The ‘drunken Irish’ are a common stereotype known around the world and the children’s drawings reflect this. In an interview, one child draws on his personal experience, greatly elaborating on their drawing:

Em like just this cause my like every time I go to the pub like my dad anall [sic] always there always like literally when you walk into the pub up the road my dad’s the manager and you walk up there you can see literally everybody with Guinness and all and loads of people in Ireland anall like the Guinness cause it’s like a Guinness beer from Irish. (Male, age 11)

Sports – Irish-medium

Traditional Irish sport, Gaelic football, hurling and camogie, were popular signifiers of Ireland in the Irish-medium primary school children’s Irish symbol drawings.

GAA sports

A minority of children did not say much when asked to explain their drawings: ‘GAA … eh it’s an Irish sport’ (male, age 10). However, most emphasised the cultural role of GAA sports, and their importance as a unique signifier of Ireland: ‘Hurling it’s only played in Ireland and it’s very important to our culture same with Gaelic football’ (male, age 10). This child emphasises GAA sport as ‘belonging’ to Ireland: ‘It’s our sport it’s not like other countries sport and they do play it but it’s like ours … that’s our native sport’ (male, age all 11). Overall the majority of children who drew Gaelic football, hurling and camogie as symbols for Ireland discussed it in a way that conveyed a sense of respect and appreciation for GAA sports.

Sports – English-medium

Sports were a key image in the English-medium primary school children’s Irish symbols drawings, although in contrast to the Irish-medium primary school children, they included sports besides GAA.

GAA sports

However, a majority of children did draw GAA sports. Most emphasised the cultural and historical ties to the national sports:

Hurling and Gaelic, they’re like the national sports … because we had to win we had to be able to like get like we had to like eh we had to kind of change England’s mind to let us play our national games. (Male, age 12)

Non-GAA sports

English-medium primary school children included non-GAA sports in their drawings. When discussing rugby, one child emphasised Ireland’s prowess as a reason for it symbolising Ireland: ‘There’s the rugby team em because I done that because em it’s a sport that we are really good at and we’ve been up there and we’ve won loads of stuff for rugby and all’ (male, age 11). Three children also drew Irish dancers. While some people may not consider Irish dancing a sport, in their interviews all children referred to it as such: ‘Irish dancing because it’s nice to have like a main sort of sport in Ireland’ (female, age 11). English-medium primary school children consider sport to be a major symbol of Ireland, but their understanding of this symbol is not confined to GAA sports like the Irish-medium primary school children’s. Irish dancing has clear roots in Irish culture, however, rugby, while popular in Ireland, is not a typical ‘Irish’ sport.

Physical characteristics of Ireland – Irish-medium

Several children chose to draw pictures of the physical characteristics that they associate with Ireland. Ireland’s landscape is known for being ‘green’ and this was conveyed in a number of children’s interviews. One child described the ‘rolling green hills’ (male, age 10) of Ireland. However, the physical characteristics of Ireland were not confined to scenery, with three children including farms in their drawings. The agricultural sector is an integral part of Ireland’s economy and therefore farms are a common feature of the Irish countryside. This was reflected in the children’s interviews: ‘Fields and hills because there’s lots of grass and a lot of farms and everything in Ireland and everything’ (female, age 11). One child emphasised the food production aspect of these farms: ‘It’s just farms because we have a lot of farms in Ireland … because we grow lots of food in Ireland and it does rain a lot but sometimes that sometimes that can be a good thing’ (female, age 11). The children’s interviews conveyed a sense of pride in the Irish landscape, in the green fields, hills and farms. By using the physical characteristics of Ireland as an Irish symbol, it suggests children see the landscape as more than simple scenery and rather something that unique to Ireland.

The past as a symbol – Irish-medium

Irish history features heavily in the Irish-medium primary school children’s Irish symbols drawings but was missing from the English-medium primary school children’s.

Celtic symbols

Historical symbols are not limited to the recent past, with Celtic symbology appearing in one’s child’s drawings: ‘It’s just kind of a like Celtic symbol, cause it’s our history’ (male, age 11). The symbol the child drew was the triskelion, a symbol found in Irish Neolithic art, most notably on the stones lining the entrance to Newgrange.

The famine

The Irish Potato Famine was also a salient symbol for a minority of children: ‘Well the potato reminds me for Ireland because the famine happened in Ireland’ (female, age 12). This child went on to say: ‘I think it might have happened somewhere else don’t know’ demonstrating how one’s own history can take on a greater importance and result in the minimising or dismissal of similar events in other places.

The Easter Rising

The 1916 rising was a pivotal moment in Irish history. The Easter Rising and the subsequent execution of its leaders by the British had a transformative effect on Irish public opinion, turning the tide against British rule and towards support for Irish independence. One child wrote ‘1916’ and demonstrated an understanding of the nuances of the Rising in their interview:

Like Ireland wanted freedom for our country so we started an uprising against the British and we didn’t win though but we still got freedom in the 19 [sic] in the war of independence with Michael Collins. (Male, age 11)

For peace you know, like so nobody fights again like England fighting Ireland ya know … because when England was fighting Ireland and we need peace so that reminds me of Ireland. (Male, age 10)

European symbols

There was also substantial overlap between the content of European symbols for children from both types of schools (). For example, they drew and described different signifiers of the EU, monetary symbols and different European countries. Children in the Irish-medium primary schools also drew images that represented Europe through an Irish lens, and images specifically of European cuisine, while these did not appear in English-medium school drawings. At the same time, English-medium school children used sport as a representation of European symbols that did not appear in the Gaelscoil students drawings.

Figure 3. Drawings for each of the themes that emerged for European symbols across both school types. Example images are shared in both columns when drawn by participating children.

Signifiers of the EU – Gaelscoil

The European Union has constructed a number of official symbols to signify EU membership including that of the European flag, however unofficial symbols and current EU events also form part of these children’s associations with the EU.

The European flag

Their interviews revealed a straightforward or matter of fact response as to why they drew the European flag: ‘It’s just the European flag … so you know it’s Europe’ (male, age 11). One child attempted to elaborate on the meaning of the flag: ‘It’s the European flag, I’m pretty sure that the stars represent all the countries’ (female, age 11).

European licence plates

The licence plates of the member states of the EU each have the circle of stars from the European flag as a common signifier. One child mentioned licence plates in their drawings, and while they did not comment on the stars they mentioned that most of the licence plates they have seen are from European countries.

Signifiers of the EU – English-medium

The official signifier of the EU, the EU flag, was seen consistently in the drawings of the English-medium primary school children.

The European flag

In a similar way to the Irish-medium primary school children, their interviews yielded a straightforward explanation as to why: ‘Eh that’s the European flag, cause like that’s just their flag. There’s probably more stars but I wasn’t able to draw them all … because the flags their symbol and like yeah’ (male, age 12).

The EU headquarters

Two children wrote Belgium and Brussels and in their interviews emphasised the connection to the European Union: ‘I wrote Belgium because that’s where the EU headquarters are … like I think there’s a representative from each country that like all the meetings are held there’ (male, age 12).

Brexit

Brexit was also a part of a minority of children’s drawings. This child emphasised the community aspect of the EU in their interview, highlighting Britain’s desire for independence:

I just done Britain with an X through it cause Brexit happened … Britain basically wanted to leave the EU because they didn’t want to be a part of it they wanted to be on their own an independent country so ye. (Male, age 12)

Monetary symbols – Irish-medium

The euro was a common drawing among Irish-medium school children. Their interviews demonstrated that they saw it as a shared symbol of Europe:

So I chose money because more than it’s not just in Ireland that uses the same money it’s a lot of the countries in Europe use it like the same kind … you don’t really see it like if you went out of Europe not every country has it so like when you see it you think oh yeah this from the European Europe. (Male, age 11)

Monetary symbols – English-medium

The euro appeared in a majority of the English-medium primary school children’s drawings. In a similar way to the Irish-medium primary school children, they saw it as a signifier of Europe: ‘Em the euro coins because that is what every country in the EU’s currency is and what like what they spend instead of like dollars in America’ (male, age 11). Of course not all of the member states have joined the Eurozone. However, for these children the euro is a tangible signifier of Europe.

European countries – Irish-medium

Eight children identified Europe in geographical terms, using the countries which form the continent as a symbol. France and Spain were most frequently mentioned:

France, and it’s one of the countries that are in Europe so … Spain, and it’s another country that’s in Europe … because they all make Europe, like all the countries together. (Female, age 11)

European countries – English-medium

European countries were a part of seven English-medium primary school children’s European symbols drawings. Most children drew and then named specific countries: ‘I did a picture I did like a picture of Portugal because it’s another country in Europe’ (female, age 9). One child commented on the capital cities of European countries: ‘So what reminds me if it are the capitals of each country that are in Europe so like example Cyprus, the capital of Cyprus is Nicosia’ (female, age 11). However others kept it much more basic: ‘Countries cause there’s loads of countries in Europe’ (female, age 11). Ireland also featured in these children’s drawings but in the context of the country being a part of Europe: ‘I drew an Irish flag because Ireland is a country in Europe’ (female, age 9). Rather than focusing on Irish sports or landmarks as Irish-medium primary school children did in their European symbols drawings, these children framed Ireland as part of Europe. However, in a similar way to the Irish-medium school children, drawing countries or cities that are geographically a part of Europe is a simple way of signifying the continent for these children.

Europe through an Irish lens – Irish-medium

Ireland featured heavily in the Irish-medium school children’s European symbols drawings. Five children drew the Irish flag or a map of Ireland: ‘Em it’s the Irish flag, it’s in Europe so it just reminds me of Europe because it’s in Europe’ (female, age 10). As Ireland is in Europe and most likely the country these children know best, many of the interviews consisted of an ‘It’s in Ireland and Ireland is in Europe’ explanation. One child drew a sliotar which is used to play one of Ireland’s national sports: ‘It sorta reminds me of Ireland because hurling was made in Ireland and Ireland is in Europe’ (male, age 11). The Irish-medium school children who drew signifiers of Ireland for their European symbols drawings clearly viewed Europe through an Irish lens, relating Europe back to Ireland and what is most familiar to them.

European cuisine – Irish-medium

Food is familiar to children and is seen in several of their drawings as a tangible European symbol. In their interviews, some offered a broad sweeping statement of explanation: ‘It’s food because I just think that Europe has good food and it’s kind of famous for that’ (male, age 11). However others mentioned specific places and dishes, for example, ‘Em, pizza for Italy, cause Italy makes the best pizza ever’ (female, age 9), ‘A hot dog … it’s made in Germany so it is’ (male, age 10) and ‘Croissant for France … cause I’ve been to France lots of times’ (male, age 11). These children drew the familiar, and somewhat stereotypical, food of some European countries. The associations may stem from personal experience or the way food is branded, packaged and advertised.

Sports – English-medium

Sport appears to be a way in which a number of English-medium primary school children have forged associations with Europe. The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) European Championship is mentioned by two children as a signifier of Europe: ‘The second one is football cause there’s a every four years the euros take place which is a tournament of all the countries in Europe’ (male, age 12). Rugby was also mentioned by one child as a clear signifier of Europe: ‘That’s a rugby ball cause a lot of European countries play rugby and the rugby ball may represent Europe the best’ (female, age 12). One child drew a Spanish flag and a basketball and, when asked to explain their drawing in the interview, they referenced the FIBA Basketball World Cup: ‘It’s like when Spain won the basketball world cup I think’ (male, age 12). Sport has a way of bringing people together and promoting a sense of shared identity. As the GAA represented an Irish symbol, these children have used the sports teams and games of Europe as a way of symbolising the continent.

Discussion

Given the role of schools in promoting identity construction through symbols, this study explored Irish-medium and English-medium primary school children’s familiarity with Irish and European symbols. The constant comparative method revealed a number of shared categories for ‘Irish symbols’, such as Irish emblems, Irish mythology, sports and material aspects of culture. The qualitative analysis revealed a further two categories apparent in the Irish-medium primary school children’s drawings, physical characteristics of Ireland and the past as a symbol, which were not used in the English-medium primary school children’s drawings. The shared categories of ‘European symbols’ included signifiers of the EU, monetary symbols and European countries. The Irish-medium school primary children had two further categories, Europe through an Irish lens and European cuisine, while the English-medium primary school children had one further category, sport, and ‘Brexit’ as a subtheme of European symbols. This study offers a unique insight into what children consider to be symbols, with the inclusion of official signifiers of Ireland and the EU, alongside cultural and commercial symbols.

Irish symbols

There were several Irish symbols displayed in both the Irish-medium and English-medium primary school children’s drawings, including national emblems; myths, legends and folklore; commercial products; and sport. There were also two themes that solely emerged in Irish-medium, but not English-medium, schools. Irish symbols, such as the national flag, harp and shamrock, featured in most of the children’s drawings, in both the Irish-medium and English-medium primary school children’s drawings. The symbols are clear signifiers of Ireland, routinely displayed, fostering a continued sense of national attachment and identity (Butz Citation2009). Myths, legends and folklore played a similar role in identity construction in post-colonial Ireland and beyond (Ní Bhroin Citation2011). These ranged from presented authentic Irish tales (e.g. Oisín i dTír na nÓg) to the commercialised trope of the Leprechaun that acted as an Irish symbol for many children in both school types. The commercialised aspects are such as Tayto crisps and Guinness. The interviews highlighted how advertising campaigns also help to forge the association between brand and Irish identity. The children’s inclusion of Guinness in their drawings was striking, but in line with previous research (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). Sport was the final Irish symbol that the Irish-medium and the English-medium primary school children shared, particularly the GAA. The GAA was founded at the height of the Gaelic revival and played a key role in promoting nationalist views and Irish culture (Billings Citation2017). Children’s interviews emphasised the cultural importance of GAA sports, which explains its role as national identifier and symbol (Waldron and Pike Citation2006) and of ‘Irishness’ (Moffatt Citation2011). The inclusion of non-GAA sports (e.g. rugby) in the English-medium primary school children’s drawings speaks to the success Ireland has had in the global sporting arena.

The two unique themes that emerged in the Irish-medium children’s were physical descriptions and Irish history. The Irish-medium primary school children’s interviews demonstrated a similar appreciation of and cultural connection with the Irish landscape (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). Although not a ‘typical’ symbol, the landscape of one’s country can act as a cultural symbol, eliciting feelings of national identification (Bechhofer and McCrone Citation2013). The Irish-medium primary school children’s use of Irish history as a symbol may speak to the school’s ethos (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). The inclusion of the 1916 Rising, the Easter Lily and the IRA in the children’s drawings show a clear nationalist theme which was not seen in the English-medium primary school children’s drawing. The absence of this type of drawing from English-medium primary school children’s Irish symbols suggests that they may not imbue the Irish landscape with a cultural meaning in the way the Irish-medium primary school children do.

Of note, and in contrast to previous research, Irish language was not a salient Irish symbol for the Irish-medium or the English-medium primary school children (Waldron and Pike Citation2006). This may be due to children’s tendencies to draw and describe tangible symbols of identity (e.g. O’Toole, Joseph, and Nyaluke Citation2020). It is also possible that if the interviews were conducted through Irish with the Irish-medium primary school children that the Irish language may have appeared as a symbol.

European symbols

The Irish-medium and English-medium primary school children’s inclusion are of a number of signifiers of the European Union such as the European flag and currency. The European flag was described in a removed way, suggesting children are aware of the shared symbol of the European flag, but that they may not associate it with their social identity. Most children, across the two school types, drew the euro. Unlike the European flag, it was seen as a unifying symbol, something which separates Europe from other continents. Finally, the inclusion of Brexit in as a subtheme of EU in the English schools demonstrates an impressive understanding of the EU and knowledge about the current European political environment.

Symbolising Europe in geographic terms was popular with children in both the Gaelscoileanna and the English-medium primary school. Typically children named one or two European countries or offered a sketched map of the country. In contrast to the study looking at school children’s visualisations of Europe, neither the Irish-medium nor the English-medium primary school children offered a map of the European continent as a whole (Axia et al. Citation1998; Mason, Richardson, and Collins Citation2012).

The European symbol categories which were only seen in the Irish-medium primary school children’s drawings were Europe through an Irish lens and European cuisine. Irish-medium primary school children used Ireland as a grounding when drawing and discussing Europe. Mason, Richardson, and Collins (Citation2012) found a similar inclusion of and focus on symbols from the children’s own countries in their study looking at children’s visualisations of Europe. The final category which was unique to the Irish-medium primary school children was European cuisine. Using stereotypical European food was a clever way for these children to symbolise Europe, allowing them to use their knowledge of European countries and culture. However, these symbols are more linked to the individual country of origin rather than symbolising Europe as a whole.

The English-medium primary school children included sport in their European symbols drawings. The UEFA Champions League and the European Rugby Champions Cup have provided a symbol of Europe which these children can connect with, understand and observe. These leagues allow children to root for their own country, yet also provide a space to support other European countries, which in turn could increase identification with Europe (Mason, Richardson, and Collins Citation2012).

In summary, this exploratory approach demonstrates that by middle childhood, primary school children in Ireland have fairly expansive knowledge of national and European symbols. Consistent with SIDT, the content of school curriculum reflects in their drawings and narration of the importance and meaning behind such symbols. Perhaps surprising, however, is lack of substantial divergence across the two school types. That is, the themes of symbols and narrative were largely shared between Irish-medium and English-medium primary school children. Those attending Gaelscoileanna, however, reported some additional themes in both Irish and European symbols, which were not present in the English-medium schools. Expanding previous research primary concerning majority and minority group differences, the current study shows the utility of SIDT to frame not only national identities but also supra-national identities, such as European, in children.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of using a draw-and-tell design and following a script to ensure consistency across interviews, there were a number of methodological limitations. Although the script ensured some consistency across participants, a more open-ended method might have resulted in more elaborate conversations. As the interviews were conducted solely through English, it is possible that the Irish-medium children may have offered different symbols or explained their drawings in other ways if the questions were asked in Irish. However, none of the children tried to converse or explain their drawings through Irish. Furthermore, it is possible that for some children, Europe or European symbols meant very little to them, but rather than expressing this, the children drew ‘anything’, resulting in the inclusion of images which the child does not have any symbolic meaning or association with. Future research could also consider recruiting larger samples to be able to explore potential age effects; for example, are there differences between the children aged 9 and 12 in the symbols used (see Barrett Citation2007). Finally, recruiting from a larger number of schools might also help to tease apart site/curriculum specific findings. While the sample size limits the strength of the conclusions which can be drawn, the study has uncovered some interesting patterns regarding children’s perceptions of Irish and European symbols.

Future directions

This study has the potential to act as a basis for further research on Irish children’s knowledge of symbols, particularly as learned through school curricula and ethos, and the potential influence on the development of a national and European identity. For example, the content of these symbols could be used to understand how both national and European identities relate to other child outcomes, such as intergroup attitudes or behaviours (Taylor, Dautel, and Rylander Citation2020; Tomovska Misoska et al. Citation2020). Given the European goal of peace, future research that examines how the strength of the European identity may relate to children’s peacebuilding could offer important insights for policy and practice (Taylor Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to the principals for allowing their schools to participate and to the parents and children who agreed to partake in this study. We would like to thank the lab for their assistance with school recruitment; for more on this broader work, visit http://helpingkidslab.com.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Lennon Malbasha

Louise Lennon Malbasha (BA) is completing her MRes in Developmental Neuroscience and Psychopathology at UCL and Yale.

Jocelyn Dautel

Jocelyn Dautel (PhD) is a lecturer in the School of Psychology, QUB.

Laura K. Taylor

Laura K. Taylor (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Psychology, UCD.

References

- Agirdag, O., P. Huyst, and M. Van Houtte. 2012. “Determinants of the Formation of a European Identity Among Children: Individual- and School-Level Influences.” Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (2): 198–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02205.x.

- Axia, G., J. G. Bremner, P. Deluca, and G. Andreasen. 1998. “Children Drawing Europe: The Effects of Nationality, Age and Teaching.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 16 (4): 423–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1998.tb00762.x.

- Barrett, M. 1996. “English Children’s Acquisition of a European Identity.” In Changing European Identities: Social Psychological Analyses of Social Change, edited by G. M. Breakwell, and E. Lyons, 349–369. Oxford: Garland.

- Barrett, M. 2007. Children’s Knowledge, Beliefs and Feelings About Nations and National Groups. New York: Routledge.

- Barrett, M., and L. Oppenheimer. 2011. “Findings, Theories and Methods in the Study of Children’s National Identifications and National Attitudes.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 8 (1): 5–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2010.533955.

- Bechhofer, F., and D. McCrone. 2013. “Imagining the Nation: Symbols of National Culture in England and Scotland.” Ethnicities 13 (5): 544–564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812469501.

- Billings, C. 2017. “Speaking Irish with Hurley Sticks: Gaelic Sports, the Irish Language and National Identity in Revival Ireland.” Sport in History 37 (1): 25–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2016.1244702.

- Blue Star Programme. n.d. “What Is the Blue Star Programme?” https://www.bluestarprogramme.ie/

- Bruter, M. 2003. “Winning Hearts and Minds for Europe: The Impact of News and Symbols on Civic and Cultural European Identity.” Comparative Political Studies 36 (10): 1148–1179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003257609.

- Butz, D. A. 2009. “National Symbols as Agents of Psychological and Social Change.” Political Psychology 30 (5): 779–804. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00725.x.

- Carey, S. 2002. “Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration?” European Union Politics 3 (4): 387–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116502003004001.

- Connolly, P., A. Smith, and B. Kelly. 2002. Too Young to Notice? The Cultural and Political Awareness of 3–6 Year Olds in Northern Ireland. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/en/publications/too-young-to-notice-the-cultural-and-political-awareness-of-3-6-y-3.

- Dautel, J., E. Maloku, A. Tomovska Misoska, and L. K. Taylor. 2020. “Children’s Ethno-National Flag Categories in Three Divided Societies.” Journal of Cognition and Culture 20 (5): 373–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12340090.

- Driessnack, M. 2006. “Draw-and-Tell Conversations with Children About Fear.” Qualitative Health Research 16 (10): 1414–1435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306294127.

- Driessnack, M., and A. M. Gallo. 2013. “Children ‘Draw-and-Tell’ Their Knowledge of Genetics.” Paediatric Nursing 39 (4): 173.

- European Parliament Liaison Office in Ireland. 2019. Eurobarometer: Ireland Among Most Pro-European Member States. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ireland/en/news-press/eurobarometer-ireland-among-most-pro-european-member-states

- Gaeloideachas. 2019. Why Choose Irish-Medium Education? Accessed May 16, 2022. https://gaeloideachas.ie/why-choose-an-irish-medium-school/

- Government of Ireland (GOI). 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Social, Personal and Health Education. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Haywood, C., and M. Mac an Ghail. 1996. “Schooling Masculinities.” In Understanding Masculinities: Social Relations and Cultural Arenas, edited by M. Mac an Ghaill, 50–60. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Kolstø, P. 2006. “National Symbols as Signs of Unity and Division.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 29 (4): 676–701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870600665409.

- Kølvraa, C. 2016. “European Fantasies: On the EU’s Political Myths and the Affective Potential of Utopian Imaginaries for European Identity.” Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (1): 169–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12325.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Mac Giolla Phádraig, B. 2003. “A Study of Parents’ Perceptions of Their Involvement in Gaelscoileanna.” The Irish Journal of Education/Iris Eireannach an Oideachais 34: 70–79.

- Magennis, M. 2016. “National Symbols and Practices in the Everyday of Irish Education.” In Childhood and Nation, edited by Z. Millei, and R. Imre, 119–140. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mason, R., M. Richardson, and F. M. Collins. 2012. “School Children’s Visualisations of Europe.” European Educational Research Journal 11 (1): 145–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2012.11.1.145.

- Maykut, P., and R. Morehouse. 1994. Beginning Qualitative Research, a Philosophic and Practical Guide. London: The Falmer Press.

- Merrilees, C. E., L. K. Taylor, R. Baird, M. C. Goeke-Morey, P. Shirlow, and E. M. Cummings. 2018. “Neighborhood Effects of Intergroup Contact on Change in Youth Intergroup Bias.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 47 (1): 77–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0684-6.

- Merriman, B., and S. Guerin. 2006. “Using Children’s Drawings as Data in Child-Centred Research.” The Irish Journal of Psychology 27 (1–2): 48–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2006.10446227.

- Moffatt, J. 2011. “Paradigms of Irishness for Young People in Dublin.” Doctoral dissertation. National University of Ireland Maynooth. Accessed July 23, 2020. http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/2578/1/Joseph_Moffatt_Paradigms_of_Irishness_for_Young_People_in_Du.pdf

- Nesdale, D. 2004. “Social Identity Processes and Children’s Ethnic Prejudice.” In The Development of the Social Self, edited by M. Bennett, and F. Sani, 219–245. London: Psychology Press.

- Nesdale, D. 2017. “Children and Social Groups: A Social Identity Approach.” In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents, edited by A. Rutland, D. Nesdale, and C. Brown, 3–22. Malden: Wiley.

- Nesdale, D., and D. Flesser. 2001. “Social Identity and the Development of Children’s Group Attitudes.” Child Development 72 (2): 506–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00293.

- Ní Bhroin, C. 2011. “Mythologizing Ireland.” In Irish Children’s Literature and Culture: New Perspectives on Contemporary Writing, edited by K. O’Sullivan, and V. Coghlan. New York: Routledge.

- O’Toole, B., E. Joseph, and D. Nyaluke. 2020. Challenging Perceptions of Africa in Schools: Critical Approaches to Global Justice Education. Oxon: Routledge.

- Philippou, S. 2005. “Constructing National and European Identities: The Case of Greek-Cypriot Pupils.” Educational Studies 31 (3): 293–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690500236761.

- Reidy, C. M., L. K. Taylor, C. E. Merrilees, D. Ajduković, D. Č. Biruški, and E. M. Cummings. 2015. “The Political Socialization of Youth in a Post-Conflict Community.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 45: 11–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.12.005.

- Ryba, R. 1995. “Unity in Diversity: The Enigma of the European Dimension in Education.” Oxford Review of Education 21 (1): 25–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498950210102.

- Schatz, R. T., and H. Lavine. 2007. “Waving the Flag: National Symbolism, Social Identity, and Political Engagement.” Political Psychology 28 (3): 329–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00571.x.

- Scourfield, J., B. Dicks, M. Drakeford, and A. Davies. 2006. Children, Place and Identity: Nation and Locality in Middle Childhood. Oxon: Routledge.

- Shamoa-Nir, L., I. Razpurker-Apfeld, L. K. Taylor, and J. B. Dautel. 2020. “Outgroup Prosocial Giving During Childhood: The Role of Ingroup Preference and Outgroup Attitudes in a Divided Society.” International Journal of Behavioral Development. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420935619.

- Taylor, L. K. 2020. “The Developmental Peacebuilding Model (DPM) of Children’s Prosocial Behaviors in Settings of Intergroup Conflict.” Child Development Perspectives. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12377.

- Taylor, S. J., and R. Bogdan. 1984. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: The Search for Meanings. Ann Arbour: Wiley-Interscience.

- Taylor, L. K., J. Dautel, and R. Rylander. 2020. “Symbols and Labels: Children’s Awareness of Social Categories in a Divided Society.” Journal of Community Psychology 48 (5): 1512–1526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22344.

- Taylor, L. K., C. E. Merrilees, A. Campbell, P. Shirlow, E. Cairns, M. C. Goeke-Morey, Alice C. Schermerhorn, and E. M. Cummings. 2011. “Sectarian and Nonsectarian Violence: Mothers’ Appraisals of Political Conflict in Northern Ireland.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 17 (4): 343–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10781919.2011.610199.

- Tomovska Misoska, A., L. K. Taylor, J. Dautel, and R. Rylander. 2020. “Children’s Understanding of Ethnic Group Symbols: Piloting an Instrument in the Republic of North Macedonia.” Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 26 (1): 82–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000424.

- Waldron, F., and S. Pike. 2006. “What Does It Mean to be Irish? Children’s Construction of National Identity.” Irish Educational Studies 25 (2): 231–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03323310600737586.

Appendix

Interview prompts

If child asks what do I draw/what do you mean/I don’t understand-start with these prompts:

What do you think of when I say Ireland/Europe?

What do you associate with Ireland/EU and being Irish/European? Sports? Music? Dance?

If they are still struggling, you can want them through these questions for each of the two sets of drawing:

Ireland

What is the Irish flag?

Who is the patron saint of Ireland?

Europe

Do you know what Europe is?

o Europe is a continent – Ireland is in Europe

Do you know what the EU is?

o It is a union of 28* countries – they help each other and work together to solve problems – Ireland is part of the EU

Can you name any other countries in the EU?

Do you know what the European flag looks like?

What is the currency/money used in Ireland or Europe called?

*Note: The United Kingdom had not yet formally withdrawn from the European Union at the time of data collection.