ABSTRACT

Minecraft Education is a popular digital game-based learning platform designed for use in educational settings. This study explores teachers’ experiences of using Minecraft Education as an educational tool to foster the development of key competencies and skills in students. Semi-structured interviews with Irish primary school teachers (N = 11) were conducted during a national project-based initiative involving Minecraft Education in primary schools called Ireland’s Future is MINE. Thematic analysis identified six major themes: encourages student collaboration, supports creativity, students as active participants in their learning, inclusive educational tool, supports curricular content, and barriers to use. Findings emphasise how the platform can be used in the classroom to support the development of skills and competencies students need to succeed in the future while simultaneously supporting curricular content. In addition, the platform can enable learning conditions that are more inclusive and equitable for all students. External technological barriers to use need to be addressed to realise the full potential of the platform in a classroom setting. The paper concludes with a series of recommendations and implications relating to the use of Minecraft Education in primary school classrooms.

Digital technologies are rapidly reshaping society, the economy, and the nature of work (European Commission, Citation2020). In addition to this, the world is facing challenges never encountered before such as the threats of climate change, ethical artificial intelligence and false or misleading information online. The educational system is tasked with preparing students to be successful in this ever-changing technological world. According to the OECD 2030 Learning Compass, the key to success in the twenty-first century is the development of transformative or higher-order competencies (OECD, Citation2019). These competencies refer to a set of holistic concepts, which include the acquisition and application of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary for students to excel and create a better future for all (OECD, Citation2019). These competencies build on twenty-first century ‘transversal’ skills (UNESCO, Citation2015). That is, skills that are not related to specific tasks and can be used in a wide range of settings such as critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and problem solving (UNESCO, Citation2015). Digital technologies can be incorporated into learning environments to help students develop these skills and competencies (Redecker, Citation2017). Minecraft Education (ME) has been identified as a digital game-based learning platform with unique opportunities for learning (Slattery, Lehane, Butler, O’Leary, & Marshall, Citation2022). This paper explores Irish primary school teachers’ experiences of using ME as a tool to harness these twenty-first century competencies and skills during a national project-based initiative involving the platform called Ireland’s Future is MINE.

Competencies and skills for success in the twenty-first century

Transformative competencies are malleable and can be learned by integrating them into current curriculum content in a meaningful way (OCED, Citation2019). The OECD 2030 Learning Compass identifies three core transformative competencies: (1) creating new value (the ability to come up with novel innovations), (2) reconciling tensions and dilemmas (the ability to navigate challenging or conflicting situations or demands, which requires flexibility, perspective taking and an understanding that there can be multiple solutions to a problem), and (3) taking responsibility (the ability to recognise that all actions have consequences and can influence others). Providing students with opportunities to collaboratively solve and tackle real-world problems can help to develop these competencies (OECD, Citation2019). Twenty first century skills serve as a prerequisite for the development of transformative competencies. These skills refer to a wide range of skills (e.g. cognitive, interpersonal, and digital skills) and many twenty-first century skill frameworks exist (e.g. Partnership for 21st Century Learning Citation2007; for review, see Geisinger, Citation2016). Four twenty-first century skills that are particularly important and cut across all three competencies are critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and problem solving. Thus, a key issue for educators is how to design effective learning experiences that enable children to develop these skills and competencies. Educators are increasingly being asked to employ new methods of instruction to achieve this, particularly methods involving the use of digital technologies (Redecker, Citation2017).

Digital game-based learning

Digital game-based learning (DGBL) is an instructional method that can provide opportunities to facilitate twenty-first century skill development in students (e.g. Qian & Clark, Citation2016). DGBL, as the name suggests, is the use of digital games in learning environments. It includes off-the-shelf games (i.e. games developed for entertainment but used for learning purposes) and special purpose or serious games (i.e. games developed for learning purposes; All, Castellar, & Van Looy, Citation2016). These games use various game design elements such as adaptive challenge, incentive systems, graceful failure, aesthetic design, and narrative design to support effective learning (e.g. Plass, Homer, & Kinzer, Citation2015). However, different games likely generate different effects on learning. This is because games vary on many design elements (e.g. some games are 2D while others are 3D). Previous research has shown that ME can facilitate high quality learning experiences (e.g. Lehane, Butler, & Marshall, Citation2021). Thus, the platform may represent one potential means to help students develop the necessary competencies and skills to succeed in the future.

Minecraft Education as an educational tool

ME is a DGBL platform designed for use in educational settings. The platform is popular with educators with over 100 million downloads between March-September 2020 (Minecraft, Citation2021). Though this coincides with remote learning during Covid-19, the use of ME in schools has been increasing in recent years as educators regard it as a serious game that can be used to facilitate improved learning processes and outcomes for a range of needs and abilities (Callaghan, Citation2016). ME is a sandbox game, which means that there are no predetermined goals or objectives. This allows educators and students a great degree of creativity and freedom in terms of how they use the game. In the game, students can freely move around virtually infinite 3D ‘worlds’ that consist of cubic blocks. The platform has several features that make it beneficial for use in the classroom (e.g. students can work together to build projects in the same world, teachers can monitor students’ work within the game/turn off some settings, and teachers can use various features to track student progress or provide feedback). In the past, some regarded DGBL as ‘edutainment’ that only served to improve students’ motivation (Charsky, Citation2010); however, game-based learning can effectively support learning if appropriate games are chosen (Lehane et al., Citation2021). According to Schrier (Citation2018), DGBL should be used when it is the most appropriate instructional method and contributes to a meaningful learning experience for students. As a versatile DGBL platform, educators can easily modify ME to develop key competencies and skills while simultaneously supporting curricular content. Importantly, Minecraft supports several principles of key learning theories (Slattery et al., Citation2022). For example, Papert’s constructionism, which builds on constructivism, posits that learning happens most effectively when learners design and/or construct artefacts that can be shared or discussed with others. These artefacts then become ‘objects to think with’ (Papert, Citation1980, p. 12) and facilitate knowledge construction. This theory is particularly well suited to understand knowledge and skill acquisition with Minecraft as learners construct digital 3D artefacts in the game, which can be shared and discussed with others (e.g. classmates, teachers, parents).

Project-based learning opportunities in ME may be most effective for developing transformative competencies. Project-based learning is a student-centred, inquiry-based approach to instruction that supports learning via exploration of real-world problems and challenges (Condliffe et al., Citation2017). It is based on constructivist learning principles (Kokotsaki, Menzies, & Wiggins, Citation2016). According to Krajcik and Shin (Citation2014), the key characteristics of project-based learning include: (1) a driving question/problem, (2) learning goals, (3) scientific practices, (4) collaboration, (5) use of digital tools, and (6) creation of a final product. Other important features of project-based learning include balancing instruction and independent student inquiry and including a degree of student choice and autonomy (Kokotsaki et al., Citation2016). Importantly, project-based learning has been identified as a key approach for developing core competencies and skills (Birdman, Wiek, & Lang, Citation2022). However, it can be challenging to implement project-based learning in some classrooms (Condliffe et al., Citation2017). ME can be used to support project-based learning activities and these activities can facilitate meaningful learning if the activities are aligned with curricular content and objectives (Lehane et al., Citation2021). Project-based learning activities in Minecraft have been effectively used across a range of learning or subject areas such as English, history and STEM (e.g. Butler, Brown, & Criosta, Citation2016; Callaghan, Citation2016). Therefore, embedding these core skills and competencies in curriculum-based project work in the platform may create high quality learning experiences for students.

A project-based initiative with Minecraft Education

In 2021, a national initiative was launched across the island of Ireland called Ireland’s Future is MINE. The initiative involved the use of ME as a tool to support the development of transversal skills and competencies in primary school students (3rd to 6th class). Schools could avail of 120 free ME licences. The initiative had two phases. During the first phase, six educational episodes on ME aired on Ireland’s national broadcaster (RTÉ). The episodes were designed to enable students and teachers to learn how to use the platform. In each episode, students were given a challenge and were required to use the platform to complete it (e.g. design and build a house). During the second phase, a competition was held for schools, which required class groups to complete a project on the topic of sustainability. Class groups were asked to design a sustainable version of their local community by working collaboratively to come up with an innovative solution, build this community in ME, and make a video to showcase their work. This topic was chosen to align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (or Global Goals), in particular the goal of ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ (United Nations, Citation2015). Moreover, the project incorporated many key curricular areas such as mathematics, geography, science, and social, personal, and health education. The current study follows on from this initiative and explores Irish primary school teachers’ experiences of using ME as an educational tool to help students develop key competencies and transversal skills.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with teachers to examine their experiences of using ME in their classrooms during the Ireland’s Future is MINE initiative. The study was granted ethical approval by Dublin City University’s research ethics committee (DCUREC/2021/202).

Participants

Teachers were invited to register their interest in the research when they signed up for their ME licences and advertisements were circulated via social media and stakeholder groups. Eleven primary school teachers (n = 8 female) participated in the research. All participants have been assigned a pseudonym for confidentiality purposes. Teachers taught 3rd to 6th class. Out of the 11 teachers, 7 reported no or slight ME proficiency. One teacher reported high proficiency. Most teachers taught in mixed gender schools (n = 9). Additional demographic characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Participant demographic information.

Semi-structured interviews

Interviews were semi structured with the schedule of questions designed to encourage discussion of teachers’ experiences of ME with a focus on problem solving, creativity, critical thinking, and collaboration – Do you think Minecraft Education impacts students’ development of problem solving / creativity / critical thinking / collaboration skills? If so, how? We included prompts in the interview schedule to encourage further discussion. Each member of the research team reviewed and provided feedback on the schedule, and it was piloted a priori with another researcher who has qualitative expertise and previously worked as a primary school teacher. Interviews were conducted by the first author on Zoom in January and February 2022. The audio was recorded. Interview duration ranged from 17 to 33 min (M = 28). Zoom transcription was used to transcribe the interviews. All transcripts were reviewed for accuracy by the interviewer. From the 6th participant onwards, similar patterns were discussed, which indicated data saturation.

Data analysis

Our main goal was to examine patterns across participants’ experiences of using the ME platform. Thus, we chose reflective thematic analysis to analyse the data. The analysis was conducted in line with Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step framework for reflective thematic analysis: (1) familiarisation, (2) initial coding, (3) theme search, (4) theme review, (5) theme definition and, (6) write up. The first author read and re-read the transcripts, and coded and recoded the data using an inductive approach. The codes were then organised into initial themes. The initial themes were reviewed and refined. Themes were then defined and the relationships between themes were identified. The first author developed the themes. Further detail on theme development is presented in . NVivo software was used for data analysis.

Table 2. Application of thematic analysis.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity is a key aspect of quality practices in reflective thematic analysis. It involves critically reflecting on how the researcher (e.g. their values, attitudes, and knowledge) and their research practices (e.g. methodological choices) influence knowledge production (Bran & Clarke, Citation2022). A reflexive research journal is an important part of the practice (Bran & Clarke, Citation2022). As such, the first author kept a research journal during the project to document thoughts for consideration.

Results

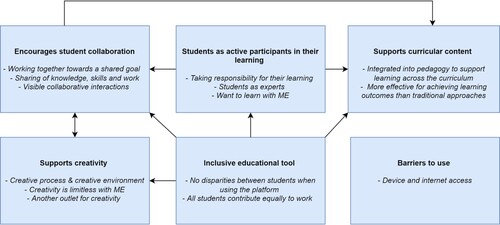

Six distinct overarching themes were identified (‘encourages student collaboration’, ‘supports creativity’, ‘students as active participants in their learning’, ‘inclusive educational tool’, ‘supports curricular content’, and ‘barriers to use’). visually depicts the final thematic framework and the relationships between themes.

Theme 1: encourages student collaboration

Most participants identified student collaboration as a key feature of using the platform in the classroom. ‘I think it really fosters collaboration’ (Sue). Students engaged in genuine collaboration. That is, students worked interdependently towards a shared goal (e.g. to solve a problem encountered or design a build) and this was achieved by students sharing their knowledge, skills, and workload.

Collaboration occurred in both the physical and virtual world. In the classroom, students’ collaborative efforts were visible as the teachers reported observing students working together on various aspects of their projects:

They're just talking all the time to each other, talking about who's doing what, and what's going on where, and what's working and what's not working. I can hear them say ‘will you do that bit, and I'll do this bit and then such and such can do that bit’. So, they are planning what they're doing, when they're doing it and who's doing each individual part of it. So, it's very clear. (Lucy).

Importantly, collaboration supported the acquisition of academic skills (e.g. coding) and other critical skills such as planning and problem solving. Teachers referenced several instances of peer-to-peer teaching occurring organically within the classroom while students used the platform. In these instances, a more capable peer assisted another student or students when a problem or issue was encountered. Often this involved openly sharing information (e.g. an idea they viewed as beneficial for the class) and providing others with feedback on their work.

You'll find during the day, they’re coding, and somebody will say, 'I'm stuck on this bit', and somebody else from another group might go over and help so that's the system we're using anyway. (Katie)

So, they would teach each other the coding. I might have one student that is particularly good, and they will come up and they would share something or another student would share their screen and show the class what they're doing. They’re coming up with ideas for the builds … So, they would share that all the time and they would just say to me ‘look, I've a really good idea can I show everybody?’ and that would happen organically. (Mary)

There were various different people giving feedback to other people about how to do it and demonstrating. (Paul)

Theme 2: supports creativity

All teachers highlighted how using the platform supported students’ imagination and idea creation. ‘They were coming up with brilliant ideas’ (John). The platform provided students with an opportunity to ‘think outside of the box’ (Paul). Ideas were novel and useful. Many teachers expressed surprise at the original and elaborate nature of students’ ideas. ‘They came up with loads of ideas that I wouldn’t have thought of.’(Lucy) / ‘The students had huge ideas and different things, things that you would never, me and you wouldn’t think’ (Mark).

Teachers discussed creativity and ME in terms of the creative process, the creative environment it fostered, and the end creative product built in the platform. Typically, the creative process arose from a problem or question students encountered. Potential solutions to these issues were considered in a process that involved idea creation (divergent thinking) and critically thinking about the ideas that were generated:

One of the groups were looking at the pitch behind the church and they decided it's quite mucky so they would drain that pitch and they would use the water from the pitch to water an area of a plots for vegetables that would be used by the community. They came up with that idea themselves that this would be a good use of that water, rather than just draining the pitch and then it not having use beyond that. That was a fourth-class student that came up with that idea, so you know, I was pretty blown away by that and that they would just be thinking in those terms. (Mary)

They have so much freedom with this and there is far more freedom within Minecraft than there is within the classroom because, obviously, everything is there, whereas in the classroom you might have to go out to buy things. There is no limit to what they can do … There is a finite number of resources in the classroom but there is an infinite amount in Minecraft, and they can just go hell for leather. (Helen)

They can try something and if it does not work, they can just get rid of it. They seem to be very free to come up with suggestions and they are not worried about having a wrong answer. (Lucy)

It allows those kids who might not be the most artistic kids and they might be more inclined towards technology or maybe more maths or things like that, Minecraft allows those kids to kind of come into their own in terms of being a bit more creative … It is just another form of creativity, like when we talk about multiple intelligences; it is another string in the bow like to allow kids to be creative. (Ann)

Theme 3: students are active participants in their learning

ME gave students the opportunity to be agents in their own learning. Students play an active role and are motivated to engage in the learning process when using the platform (e.g. in deciding what would be included and how this would be included). This was reiterated across interviews. Many teachers described how students took responsibility for their learning, ‘Children have a lot more autonomy and ownership over it.’ (Sue). This was highlighted in comparison to other teaching and learning activities students typically engage with in the classroom. For example, one teacher explained this in relation to the open-ended nature of the platform with students having more freedom and choice compared to other teaching and learning activities:

In other subjects, you might have a particular path you want them to go down … where in this one they've basic instructions that they have to fulfil, but it can be a lot more free within the project to do different things. (Lucy)

I have given them a timeline of when we have to be ready, and they are self-regulating and self-organising. The student that is hosting the world will come on and he will type in One Note, the code and the time he's on at and the others can join then to do their work as they want. They've been really motivated about that so it's not just happening within the school day, it’s happening at home as well, and again they're the ones that are – it's not me saying 'you need to come in at five o'clock', it's them organizing. (Mary)

I've got a cohort of boys who are not really, they're very difficult to engage in class, but when it came to Minecraft, one of the boys is pretty much heading up our whole project, he's helping everyone. (Marie)

I can say that with absolute confidence, everyone actually did their job, and I didn't have to force them to do it, even the kids who wouldn't have been as familiar with Minecraft wanted to learn … Everyone wanted to do it because it was really high value. Very motivational you know, there was nobody who didn't enjoy it, which is quite strange because there's always someone who's against [something] … I'm convinced there's days that you could bring an actual rainbow in here and they'd be like – eh. You know, whereas that just didn't happen. (Marie)

Theme 4: inclusive educational tool

Teachers’ highlighted ME as a beneficial tool to support learners with special educational needs. The platform helped to ensure learning was more inclusive and equitable for all students in the classroom. This was reiterated across a range of additional needs, including ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, and anxiety. This was particularly the case for students with literacy challenges such as dyslexia. One teacher described how there are no disparities between students with and without dyslexia when using the platform. ‘They [students] are not disadvantaged by dyslexia, for example, they are on a level playing field with everybody else, which is huge.’ (Lucy). Importantly, it enabled students with additional needs to display their knowledge and skills and demonstrate their understanding of learning activities. One teacher (6th class), Eve, integrated the platform into their English lessons and described how using the platform helped a student with literacy challenges demonstrate their comprehension of a class novel:

There is one student in the class who would have literacy challenges. They would have been very engaged in the novel but in terms of their response to the novel, it would have been closer to maybe a third class written response like comprehension questions, your standard read a story and answer questions on it. Those kind of things would pose a challenge but they were probably one of the strongest in creating a scene from the novel … It proved to me that they had really engaged with the novel and understood the novel, but because of their language difficulties, they would not have been able to express that in a written format, like in an essay. (Eve)

One child in particular who is selective mute, they have selective mutism and when it comes to doing Minecraft they are more interested in, you know they are more engaged showing me what they are building … They are more willing to communicate with me now. (Katie)

Usually, you will get a couple of kids who would be very able children and they would be good problem solvers. If you have a problem-solving task, you tend to have one child who would be doing the problem solving and the other kids would just do what they had told them. Whereas in Minecraft … they all join, and they all feel comfortable with it, so they all contribute to the problem solving. Everybody is chipping in something. (Lucy)

Theme 5: supports curricular content

Most teachers described ME as a versatile tool they could embed into their practice to support learning across the curriculum ‘I just feel it slots in with every area of the curriculum’ (Marie) / ‘It could be made to link into everything’ (John). Teachers identified the platform as a tool to effectively support learning objectives. One teacher discussed how they felt learning was more effective with Minecraft compared to more traditional materials, ‘I think the learning potential in those active activities [Minecraft activities] is invaluable and way better than anything you're going to get in the workbook.’ (Marie). Another teacher, Mark, described how he replaced a physical building project with a virtual building project and felt the learning objectives were more effectively achieved using the platform.

For fifth class, we always do a castle build and my teaching partner [and I] we talked about it. They did it in the classic cardboard building and I did it in Minecraft. The detail of it [the project] in Minecraft, the students could do a lot more detail … We saw a huge difference in quality and their learning outcomes, we felt they were a lot more achievable in Minecraft … just for the more fine details; the learning outcomes are more achievable in Minecraft than the traditional cardboard box.

Many teachers regard ME as a practical learning tool, which brings learning to life. It can bring a practical and visual element to subjects that do not usually have this. Moreover, the platform allows students to put themselves in the centre of the learning, and to see things from others’ point of view. Mark discussed this with regard to history:

Particularly in history, you can just bring it to life with the castles. There's a lot of text, there's a lot of illustrations, a lot of just drawings, but they are able to walk through Minecraft so they are interacting with the model, they are interacting with the build, they are interacting with each other, just being able to walk through it was like a virtual tour at the end of it. So, it's just the fact that they're involved in it. (Mark)

Theme 6: barriers to use

Teachers encountered various technical issues when using the platform. However, these issues primarily related to devices and internet access. Firstly, many teachers did not have access to enough student devices. This limited teachers’ and students’ ability to use the platform in the way they wanted. One teacher described how they had only a small number of devices in a class of 20 + students:

Our trolley that would have brought our iPads to the various classes was divided up [because of Covid], so I ended up with two or three iPads, but we also have a few people that are using assistive tech, so I had access to a few laptops as well, so I think devices were the big challenge … I’d love to have more devices. (Paul)

So, we don't have free access. We're restricted to one half day per week, and we get one extra half day per month. We have to make sure we kind of use that to its best effect and then, if someone is out that day they kind of miss it. So, if we had more access to the technology, it would be great. You know we could use it, I would use it [Minecraft] in a lot more subjects. (Sue)

Unfortunately, we don't have Wi-Fi that was strong enough in the classroom. We do have sets of iPads, but it wasn't strong enough, so what I did was source three different laptops that were not being used in the school and they kind of use the hotspot of my phone. (Katie)

Discussion

This study explores teachers’ experiences of using ME as an educational tool to foster the development of twenty-first century competencies and skills. It was conducted during a national project-based initiative involving ME in primary schools across the island of Ireland called Ireland’s Future is MINE. Six themes were identified across teacher interviews: ‘encourages student collaboration’, ‘supports creativity’, ‘students as active participants in their learning’, ‘inclusive educational tool’, ‘supports curricular content’ and ‘barriers to use’.

The findings suggest that project-based learning activities in ME may promote genuine collaboration between students in the classroom. Using the platform provides students with an opportunity to work together to complete tasks and achieve goals. In this project, classes were tasked with working together to design and create a sustainable version of their local community with the platform. Collaboration is one of the most common design elements integrated into DGBL (Qian & Clark, Citation2016), as learning often takes place in a social context. However, group work does not necessarily mean that students will engage in genuine collaboration or that students’ collaboration skills will improve (Evans, Citation2020). In the classroom, genuine collaboration occurs when individuals work interdependently, take part in a joint activity (e.g. solve a problem), and combine their knowledge, skills, and efforts (Evans, Citation2020). According to Johnson and Johnson (Citation2008), students engage in three types of interaction in the classroom: (1) promotive interaction, (2) oppositional interaction and (3) no interaction. Promotive interaction facilitates true collaboration as group members support other members to complete tasks to attain the group’s goal (Johnson & Johnson, Citation2002). Notably, this type of interaction can involve explaining and demonstrating how to solve a problem or sharing knowledge with peers (i.e. peer-to-peer teaching; Johnson & Johnson, Citation2002). DGBL provides an ideal context for peer-to-peer teaching as it promotes collaboration (Squire & Jenkins, Citation2003). In this study, the majority of teachers identified peer-to-peer teaching as a key aspect of students’ learning experience with the platform. This is a notable finding especially when one considers that peer teaching is particularly important for improving learning among lower ability students (Kimbrough, McGee, & Shigeoka, Citation2022). Overall, the findings support the notion that ME can likely foster promotive interaction and genuine collaboration between students, which may help to improve students’ collaboration skills and learning.

The second theme supports creativity emphasises how educators can use ME to develop students’ creative skills. Through gameplay in Minecraft, students can experiment with different ideas, learn from their mistakes, and collaborate with their peers, which are important elements of the creative process (e.g. Davies et al., Citation2013). One of the most widely used models of creativity is the four-P model (Rhodes, Citation1961). This model distinguishes between four components: person, process, product, and press. The person component refers to the individual, including their personality, behavioural and dispositional characteristics linked to creativity (Brandt, Citation2020). The product component refers to the outcome of the creative process such as an artistic work (Brandt, Citation2020). The process component refers to the visible cognitive steps or strategies involved in the creative act, which allow the individual to develop creative ideas (Brandt, Citation2020). Finally, the press component refers to the many external factors that influence the creative process such as social support and cultural norms (Brandt, Citation2020). The findings of this study suggest that educators can use the platform to likely foster all four components – person (e.g. self-efficacy), process (e.g. divergent thinking), product, and press (e.g. creative classroom environment). Notably, teachers consistently reiterated how ME promoted a positive creative environment due to (1) the many resources available to create in the platform and (2) the open-ended nature of the platform. This is in line with previous research on creativity development, for example, Davies et al. (Citation2013) found that the availability of appropriate materials and game-based approaches with an element of autonomy supported the development of students’ creativity skills. This provides evidence that the platform has the potential to be a powerful tool for promoting creativity by providing a learning environment that encourages students to think outside of the box and come up with novel solutions.

The third theme students as active participants in their learning captures how students take responsibility for their learning when using the platform. This is related to the concept of student agency, which can be defined as the ‘capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change’ (OECD, Citation2019, p. 16). Student agency is a crucial aspect of education in the twenty-first century (OECD, Citation2019) and providing students with a high degree of agency is a core DGBL design characteristic (Taub et al., Citation2020). At the core of student agency is students making decisions about what and how they will learn. Crucially, students want to learn with Minecraft (i.e. how). Moreover, the platform gives students the opportunity to direct the learning process (i.e. what) because of its freedom and choice. As Vaughn (Citation2020) argues this autonomy promotes student agency as students can take charge of their own learning experience. Furthermore, ME allows educators to incorporate students’ interests and experiences into teaching and learning, which is essential for cultivating student agency in the classroom (Vaughn Citation2020). Many of these features also encourage a creative classroom environment, as previously discussed (e.g. learner autonomy). Importantly, providing students with opportunities for student agency can increase students’ academic motivation and satisfaction (e.g. Reeve, Citation2013; Reeve & Tseng, Citation2011). When students can direct their own learning (e.g. make choices and decisions), they can feel more invested in the process and are more likely to remain engaged in their work. This is important as students’ academic motivation declines as they progress through the educational system (Gallup, Inc., Citation2014) and motivation plays an important role in students’ academic success (Rowell & Hong, Citation2013). Previous research has shown that student agency in DGBL can improve students’ learning outcomes (Taub et al., Citation2020). However, it is important to note that unlimited student agency does not lead to improved learning as support such as teacher guidance is required to scaffold the learning experience (Taub et al., Citation2020). Overall, this study indicates that teachers believe that ME can be used to give students a sense of control and ownership over their learning, which fosters a positive learning environment. This can help students feel more motivated and engaged in their education.

The fourth theme Minecraft Education as an inclusive educational tool is about how the platform supports the inclusion of students with a range of needs and abilities. This study provides evidence that ME is a tool that may be used to ensure learning is more inclusive and equitable for all students and their needs are appropriately met (i.e. it supports inclusive educational practice). According to the National Council for Special Education (NCSE, Citation2011), inclusive education involves (1) identifying and responding to the diverse needs of students and (2) removing barriers to education by providing appropriate supports to allow each student to reach their full potential. All teachers should implement teaching and learning approaches into their practice that support the meaningful inclusion of students with special educational needs (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2020). Guidelines developed by the Department of Education and Skills for the educational provision of students with special educational needs in Ireland recommend embedding digital tools into teaching, learning and assessment to facilitate a truly inclusive classroom (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2020). DGBL may support inclusive learning in the classroom by providing a variety of ways for students to engage with learning content and progress at their own pace (Salgarayeva, Iliyasova, Makhanova, & Abdrayimov, Citation2021). For example, some digital games such as ME can be tailored to meet the needs and abilities of each individual student. Moreover, as previously discussed, digital games can also provide an engaging way for students to learn, which can help sustain students’ motivation and attention. Student engagement is regarded as a critical factor in the effective educational provision of students with special educational needs as it can help improve academic, social, and emotional outcomes (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2020). This study indicates that project-based learning with Minecraft Education may be used by teachers to ensure all students have an equal opportunity to learn and succeed.

The fifth theme supports curricular content relates to how teachers can integrate the platform into their practice to support learning in various areas. The platform is open-ended and versatile, which allows teachers to adapt the game to their teaching and design their own lessons (Lehane et al., Citation2021). As such, they can customise their students’ learning experiences. Teachers can use the platform to create lessons, assign activities and monitor student progress. In addition, the platform has a catalogue of pre-existing lesson plans and resources that teachers can use to support their students’ learning. Moreover, the use of digital tools in education may improve curricular outcomes (Twyman, Citation2014). Minecraft has been used across a range of learning areas, including STEM (e.g. Hobbs, Bentley, Hartley, Stevens, & Bolton, Citation2020), history (e.g. Butler et al., Citation2016) and socio-emotional development (e.g. Stone, Mills, & Saggers, Citation2019).

The final theme barriers to use includes the factors that restrict teachers’ engagement with the platform. While technology use is increasing in Irish classrooms, technology infrastructure (e.g. Wi-Fi) is still an issue in many schools (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2022). Ertmer (Citation1999) describes two types of barriers that influence teachers’ integration of technology in their classroom: first-order barriers (external to the teacher e.g. devices) and second-order barriers (internal to the teacher e.g. teachers’ confidence using technology, expertise in using technology). Both barriers must be overcome to achieve successful technological integration. Increasing device access and improving Wi-Fi will help teachers to integrate the platform into their practice.

Recommendations and implications

This study has important implications for the educational system. Below we detail a series of recommendations and implications based on the findings of the current study, which are directed at teachers, school leaders and policy makers. It is our hope that these recommendations will guide the use of ME in the classroom moving forward.

Incorporate ME into lesson planning to support curricular objectives: Consider using ME as a tool to teach curricular content in a variety of subject areas such as history, science, maths, and languages.

Use ME to support project-based learning: Consider using ME as a platform for project-based learning, where students try to solve real-world problems or challenges. This may help students develop transformative competencies and twenty-first century skills such as creativity.

Foster collaboration: Encourage students to work in small groups or pairs to complete tasks or projects using the platform. Provide opportunities for students to share their ideas and work together to solve problems. This can help students to learn how to collaborate with their classmates, communicate effectively with one another, and develop their perspective taking skills.

Incorporate ME into learning experiences to promote inclusive and equitable learning. The platform can be used to help ensure all students participate in and contribute to the learning process in a meaningful way.

Encourage students to create, build and experiment: Encourage students to use ME to create their own projects such as building local landmarks and designing environments. Highlight the importance of experimenting with different approaches and solutions. This may help students to develop their creativity, innovation, and problem-solving skills.

Utilise the customisable nature of the platform to tailor learning experiences to individual student needs: ME is open-ended so teachers can use this feature to create individual learning opportunities for students (e.g. teachers can create custom tasks that are aligned to learning goals).

Promote student agency: Allow students to take ownership of their learning by giving them the freedom to direct their learning in ME. This can help ensure students are active participants in their learning, which helps develop their self-directed and self-regulation learning skills. In addition, this may increase students’ motivation and engagement in the learning process.

Professional learning opportunities for teachers (pre-service and in-service) in DGBL and ME: To effectively integrate DGBL environments such as ME into the classroom, teachers must understand the full functionality of the platform.

Conclusion

Our findings have significant implications for educators and policy makers. They suggest strongly that it is possible to embed newer competencies and skills into the curriculum in a meaningful way through project-based learning experiences in ME. This was particularly the case for creativity, collaboration, and student agency. In addition, educators in our study demonstrated that they can use the platform to support existing curricular content. Importantly, the study provides clear evidence that ME supports the inclusion of students with a range of needs and abilities. External barriers in relation to technology infrastructure restrict the use of the platform in the classroom and need to be addressed if educators are to use the platform to its full potential and embed it into daily school life. Overall, the data from this study can be used to support the argument that the platform is a valuable educational tool for learning in the twenty-first century. Further data derived from an experimental study on the impact of ME on students’ spatial thinking is currently underway in a number of Irish primary schools and will be analysed by the authors in the months ahead.

Disclosure statement

This research has been funded by Microsoft Education Ireland. Microsoft is the owner of Minecraft. Declarations of interest: Eadaoin Slattery’s position at Dublin City University is funded by a grant from Microsoft Ireland to DB and MoL. Kevin Marshall is an employee of Microsoft Ireland.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eadaoin J. Slattery

Dr Éadaoin Slattery is a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre for Assessment Research, Policy and Practice in Education (CARPE) in Dublin City University. She holds a Ph.D. in Psychology from the University of Limerick. Her post-doctoral research focuses on digital game-based learning and assessment with Minecraft Education. She is broadly interested in the measurement and enhancement of cognition and learning in young people, and the design and evaluation of educational interventions.

Deirdre Butler

Deirdre Butler is a Professor at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. Her passion in life is exploring what being digital in learning can mean and what skills or competencies are needed to live and thrive in today's complex globally connected world. Deirdre is internationally recognised in the field of digital learning, particularly for the design and development of sustainable, scalable models of teacher professional learning. She consistently works across a broad range of stakeholders in education, technology, government, corporate and non-profit sectors.

Michael O’Leary

Professor Michael O'Leary held the Prometric Chair in Assessment at Dublin City University (DCU) and was Director of the Centre for Assessment Research Policy and Practice in Education (CARPE) at the Institute of Education, DCU, from 2015–2022. He gained his Ph.D. in Educational Research and Measurement at Boston College in 1999. At CARPE he led an extensive programme of research focused on assessment and measurement at all levels of the educational system and in the workplace.

Kevin Marshall

Dr Kevin Marshall is Head of Learning and Skills at Microsoft Ireland. He has a B.A. (Hons) in Psychology from University College Dublin, an M.Sc. in Occupational Psychology from the University of Hull, and a Ph.D. in Educational Measurement & Research from Boston College. He is interested in empowering students and teachers of today to create the world of tomorrow.

References

- All, A., E. P. N. Castellar, and J. Van Looy. 2016. “Assessing the Effectiveness of Digital Game-Based Learning: Best Practices.” Computers & Education 92-93: 90–103. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.007.

- Birdman, J., A. Wiek, and D. J. Lang. 2022. “Developing Key Competencies in Sustainability Through Project-Based Learning in Graduate Sustainability Programs.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 23 (5): 1139–1157. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/1467-6370 doi:10.1108/IJSHE-12-2020-0506

- Bran, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE.

- Brandt, W. C. 2020. Measuring Student Success Skills: A Review of the Literature on Creativity. Dover, NH: National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Butler, D., M. Brown, and G. Mac Criosta. 2016. Telling the Story of MindRising: Minecraft, Mindfulness and Meaningful Learning. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting for the International Association for Development of the Information Society, Melbourne, December 6-8.

- Callaghan, N. 2016. “Investigating the Role of Minecraft in Educational Learning Environments.” Educational Media International 53 (4): 244–260. doi:10.1080/09523987.2016.1254877.

- Charsky, D. 2010. “From Edutainment to Serious Games: A Change in the Use of Game Characteristics.” Games and Culture 5 (2): 177–198. doi:10.1177/1555412009354727.

- Condliffe, B., J. Quint, M. G. Visher, M. R. Bangser, S. Drohojowska, L. Saco, and E. Nelson. 2017. Project-Based Learning: A Literature Review [Working Paper]. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578933.pdf.

- Davies, D., D. Jindal-Snape, C. Collier, R. Digby, P. Hay, and A. Howe. 2013. “Creative Learning Environments in Education—A Systematic Literature Review.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 8: 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2012.07.004.

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2020. Guidelines for Primary Schools: Supporting Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/edf64-guidelines-for-primary-schools-supporting-pupils-with-special-educational-needs-in-mainstream-schools/#.

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2022. Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/69fb88-digital-strategy-for-schools/.

- Ertmer, P. A. 1999. “Addressing First- and Second-Order Barriers to Change: Strategies for Technology Integration.” Educational Technology Research and Development 47 (4): 47–61. doi:10.1007/BF02299597.

- European Commission. 2020. Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027: Resetting Education and Training for the Digital Age. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0624.

- Evans, C. 2020. Measuring Student Success Skills: A Review of the Literature on Collaboration. Dover, NH: National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment.

- Gallup, Inc. 2014. State of America’s Schools Report: The Path to Winning Again in Education. https://www.gallup.com/services/178769/state-america-schools-report.aspx.

- Geisinger, K. F. 2016. “21st Century Skills: What Are They and How Do We Assess Them?” Applied Measurement in Education 29 (4): 245–249. doi:10.1080/08957347.2016.1209207.

- Hobbs, L., S. Bentley, J. Hartley, C. Stevens, and T. Bolton. 2020. “Exploring Coral Reef Conservation in Minecraft.” ASE International 9 (1): 24–28. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/147530/1/Hobbs_et_al.pdf.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 2002. “Learning Together and Alone: Overview and Meta-Analysis.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 22 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1080/0218879020220110.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 2008. “Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning: The Teacher’s Role.” In The Teacher’s Role in Implementing Cooperative Learning in the Classroom Edited by P. Dillenbourg, 9–37. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Kimbrough, E. O., A. D. McGee, and H. Shigeoka. 2022. “How do Peers Impact Learning? An Experimental Investigation of Peer-to-Peer Teaching and Ability Tracking.” Journal of Human Resources 57 (1): 304–339. doi:10.3368/jhr.57.1.0918-9770R2.

- Kokotsaki, D., V. Menzies, and A. Wiggins. 2016. “Project-Based Learning: A Review of the Literature.” Improving Schools 19 (3): 267–277. doi:10.1177/1365480216659733.

- Krajcik, J. S., and N. Shin. 2014. “Project-Based Learning.” In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Scienc (2nd ed.), edited by R. K. Sawyer, 275–297. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lehane, P., D. Butler, and K. Marshall. 2021. Building a New World in Education: Exploring Minecraft for Learning, Teaching and Assessment [White Paper]. https://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/inline-files/m90135-minecraft-191121_web_singles.pdf.

- Minecraft. 2021. Minecraft Franchise Fact Sheet: October 2021. Xbox. https://news.xbox.com/en-us/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/04/Minecraft-Franchise-Fact-Sheet_Oct.−2021.pdf.

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2011. Inclusive Education Framework: A Guide for Schools on the Inclusion of Pupils with Special Educational Needs. https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/InclusiveEducationFramework_InteractiveVersion.pdf.

- OECD. 2019. OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030. OECD Learning Compass 2030. A Series of Concept Notes. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf.

- Papert, S. 1980. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. New York: Basic Books.

- Partnership for 21st Century Learning. 2007. Framework for 21st Century Learning. https://www.battelleforkids.org/networks/p21.

- Plass, J. L., B. D. Homer, and C. K. Kinzer. 2015. “Foundations of Game-Based Learning.” Educational Psychologist 50 (4): 258–283. doi:10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533.

- Qian, M., and K. R. Clark. 2016. “Game-based Learning and 21st Century Skills: A Review of Recent Research.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.023.

- Redecker, C. 2017. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu. doi:10.2760/159770

- Reeve, J. 2013. “How Students Create Motivationally Supportive Learning Environments for Themselves: The Concept of Agentic Engagement.” Journal of Educational Psychology 105 (3): 579–595. doi:10.1037/a0032690.

- Reeve, J., and C. M. Tseng. 2011. “Agency as a Fourth Aspect of Students’ Engagement During Learning Activities.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (4): 257–267. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002.

- Rhodes, M. 1961. “An Analysis of Creativity.” The Phi Delta Kappan 42 (7): 305–310.

- Rowell, L., and E. Hong. 2013. “Academic Motivation: Concepts, Strategies, and Counseling Approaches.” Professional School Counseling 16 (3): 158–171. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2013-16.158.

- Salgarayeva, G. I., G. G. Iliyasova, A. S. Makhanova, and R. T. Abdrayimov. 2021. “The Effects of Using Digital Game Based Learning in Primary Classes with Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Contemporary Education 10 (2): 450–461. DOI: 10.13187/ejced.2021.2.450.

- Schrier, K. 2018. “Guiding Questions for Game-Based Learning.” In Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education, edited by J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, and K.-W. Lai, 1–20. Springer International Publishing.

- Slattery, E. J., P. Lehane, D. Butler, M. O’Leary, and K. Marshall. 2022. Assessing the Benefits of Digital Game-Based Learning in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review in the Use of Minecraft. Submitted for Publication.

- Squire, K., and H. Jenkins. 2003. “Harnessing the Power of Games in Education.” Insight 3: 5–33.

- Stone, B. G., K. A. Mills, and B. Saggers. 2019. “Online Multiplayer Games for the Social Interactions of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Resource for Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (2): 209–228. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1426051.

- Taub, M., R. Sawyer, A. Smith, J. Rowe, R. Azevedo, and J. Lester. 2020. “The Agency Effect: The Impact of Student Agency on Learning, Emotions, and Problem-Solving Behaviors in a Game-Based Learning Environment.” Computers & Education 147: 103781. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103781.

- Twyman, J. S. 2014. “Envisioning Education 3.0: The Fusion of Behavior Analysis, Learning Science and Technology.” Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la Conducta 40 (2): 20–38. doi:10.5514/rmac.v40.i2.63663.

- UN. 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement.

- UNESCO. 2015. Rethinking Education: Towards a Global Common Good? https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/RethinkingEducation.pdf.

- Vaughn, M. 2020. What is Student Agency and Why is it Needed Now More Than Ever?. Theory Into Practice 59(2): 109-118. doi:10.1080/00405841.2019.1702393