ABSTRACT

Civic, social and political education (CSPE) is a mandatory citizenship education subject taken during the junior cycle in the Irish post-primary curriculum. This article looks at the historical development of the subject from its first incarnation as civics to its recreation as CSPE and then to its recent move into the Wellbeing Programme. The study investigates the challenges of teaching CSPE and how those challenges relate to being a pedagogic subject, as identified by 206 CSPE teachers and based on a thematic analysis of their responses to survey questions. The findings note challenges related to the low-status of the subject and making it relevant to students. The status issues are linked to a disconnect between the conceptualisation and realisation of the subject, a lack of teacher agency and issues regarding its position in the Wellbeing Programme. The article concludes that CSPE lacks the internal ability to overcome these problems and gain increased status.

Introduction

Citizenship education

Citizenship education focuses on students learning about their rights and responsibilities, democracy and how to be active and participative citizens. In Ireland, citizenship education is provided in the post-primary curriculum in a cross-curricular fashion and through transition year social awareness and active citizenship programmes such as Young Social Innovators and distinct subjects such as politics and society at senior cycle. At junior cycle, civics and from 1997, civic, social and political education (CSPE) have been distinct citizenship education subjects. Wylie (Citation1999) suggests that treating citizenship as a distinct subject as opposed to a cross-curricular theme ensures a more consistent approach across schools and having timetabled provision reinforces the subject. Citizenship education has faced criticism for only promoting political stability (Lynch Citation2000; Merry Citation2020), neglecting political power (Frazer Citation2007) and creating the illusion of confronting social problems while not actually doing anything to address these issues (Gillborn Citation2006). Despite such critiques, citizenship education programmes have promoted greater awareness of current affairs and greater civic and political participation (Kahne and Sporte Citation2008; Manning and Edwards Citation2014; Niemi and Junn Citation1993; Whiteley Citation2014). Citizenship education programmes, however, are not identical. Westheimer and Kahne (Citation2004) outline three models of what it means to be a good citizen: personally responsible, participatory and justice oriented. The personally responsible citizen behaves responsibly but concentrates only on individual behaviour. The participatory citizen organises action but fails to question the root causes of injustice. Justice-oriented citizens challenge the root causes of problems in society but lack leadership capacity. Westheimer and Kahne view the latter two models as more evolved and beneficial for a democratic society. Westheimer (Citation2019) suggests that citizenship education should teach students to ask questions and expose them to multiple perspectives and root instruction in local contexts. Yet critical thinking and justice-oriented citizenship are rarely taught (Leung, Yuen, and Ngai Citation2014) and are more likely to be experienced by high-achieving students from wealthier backgrounds (Cohen Citation2016; Kahne and Middaugh Citation2008).

Reichert and Torney-Purta (Citation2019) identified three views of citizenship education among citizenship teachers that broadly align with Westheimer and Kahne's typologies: dutiful school participation and consensus building, knowledge and community participation, and independent thinking and tolerance. In Ireland, the dominant profile is knowledge and community participation, which suggests that CSPE equates to participatory citizenship.

Theoretical framework

Goodson (Citation1993) outlines how subjects predominantly fall within one of three categories: academic, utilitarian and pedagogic. Elements of all three are evident in each subject but the more academic subjects have greater prestige and power. They attract more able students and focus on abstraction and theory rather than being practical and socially relevant. All school stakeholders accept the high-status of academic subjects, parents see certification as a route to better jobs, teachers use examination success to provide motivation and prestige for their subjects, and principals promote academic success to enhance their school's reputation. Utilitarian subjects have a low-status but provide practical knowledge that is relevant to everyday life, helping prepare students for vocational work. Pedagogic subjects, such as social studies and civics, focus on students’ personal and social development rather than preparing them for work; these subjects emphasise common-sense knowledge and employ active learning methodologies to move the student from being a passive participant to an active agent in the learning process. The teachers of academic or utilitarian subjects are subject specialists, whereas pedagogic subjects are often taught by non-specialists. Because it is in teachers’ interests for employment and promotion purposes, subject associations, supported by university scholars, promote academic formulations of their subject. This academic drift leads to high-status for the subject.

Until the 1970s, educational change was generally initiated by teachers and educationalists (Goodson Citation2014). However, external changes, driven by business groups, think-tanks and pressure groups that view education as a service and parents as consumers, have come to dominate educational change and side-lined the expertise of internal change agents in the decision-making process. Teachers are therefore expected to implement changes they have had no role in initiating. This has generated indifference and active hostility among teachers because many changes seem ill-conceived and professionally naïve. Goodson (Citation2001) suggests that educational reform works best when the change is driven by internal school agents and takes cognisance of their personal projects and concerns.

In the Irish system, a focus on education for the market has progressively influenced the education system (Lynch Citation2012). Agents outside the education system are increasingly promoting educational change to service the market needs, with some constructing problems such as the ‘mathematics crisis’ to bring about the curricular changes they want (Kirwan and Hall Citation2016). Jeffers (Citation2008) speaks of moving from living in a society to living in an economy and how the allocation of four class periods per week to business studies at junior cycle level, compared with the single class period for CSPE, shows that academic subjects are valued more by the Department of Education and Skills (DES).

The dominance of academic subjects poses a challenge to pedagogic subjects. Duggan (Citation2015) shows how schools side-line non-academic subjects because they have low-status, are of no value for Leaving Certificate points, are allocated limited class contact time and are taught by teachers not qualified in the subject area. These subjects are seen as a break from study, the calibre of the teacher does not matter, and parents and teachers engage in minimum communication with each other. Lynch (Citation2000), however, suggests that to be relevant to young people, CSPE must be both academically challenging, providing students with opportunities to see the world from different perspectives, and set in a pedagogical environment supportive of democratic principles.

Historical overview of civics and CSPE

Civics

In 1959, Sean Lemass became Taoiseach and initiated a programme of economic reform that saw a move from protectionism towards free trade. These reforms included an attempt to join the European Economic Community in 1961 and the signing of the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement in 1965 (Lee Citation1989). The emigration rate fell from 14.8% to 3.7%, and the population rose to almost 3 million. Irish society began to be exposed to the wider world with Irish battalions joining United Nations peacekeeping missions and the founding of Radio Telefís Éireann (RTE) television in 1961 (Keogh Citation2005).

The 1965 Investment in Education Report provided evidence of a lack of opportunity for poorer children in post-primary and higher education (Lee Citation1989). Lemass saw education as the key to reforming the economy and, over the course of his premiership, appointed three proactive ministers for education – Dr Patrick Hillery, George Colley and Donogh O’Malley – who broadened the curriculum by establishing comprehensive schools, promoted higher technical education by creating regional technical colleges and expanded educational opportunities by providing free second-level education and free school transport (Fleming and Harford Citation2014). An increased emphasis was placed on subjects that were required for the labour market (Lynch Citation2012).

In September 1966, civics was introduced as a mandatory subject in post-primary schools and was allocated at least one class period per week (Dáil Éireann Citation1967). Fahy (Citation1984) suggested that the impetus for this decision came from a Council of Europe resolution on civics and European education rather than from any pressing national crisis. However, only one of the 21 syllabus topics referred to external affairs. The content-heavy syllabus emphasised the need to inculcate, train, instil, recognise and obey lawful authority. Topics such as the duties and responsibilities of the citizen and nationalism and patriotism outlined a vision of citizenship focused on patriotism and responsibilities (Department of Education Citation1970). Although the syllabus appeared academic, civics was not assessed because O’Malley believed that an examination would undermine the spirit of the subject (Dáil Éireann Citation1967).

No teaching methodologies were suggested in the syllabus. However, a second document produced by the Department of Education (Citation1966), Notes on the Teaching of Civics, provided guidance on teaching civics. This document advocated a pedagogic approach to the subject, by employing active teaching methods, emphasising the cross-curricular aspect of the subject and suggesting the use of controversial issues in civics classes to enliven ‘the dry bones of the syllabus.’ It outlined how to guide the discussion by steering ‘a middle course between complete permissiveness (which would almost certainly lead to chaos) and rigid authoritarianism.’ Promoting active methodologies, controversial issues and discussion was relatively progressive for its time.

Measures were put in place to support the implementation of civics. Seminars and regional courses were organised. In 1975, the Association of Teachers of Civics and Allied Subjects was formed, and the Institute of Public Administration (IPA) published Young Citizen, a civics magazine for students, which included a newsletter for teachers (Hyland Citation1993).

Gleeson (Citation2008), however, described the Department's attitude towards civics as one of ambivalence. By 1971, an IPA seminar of civics teachers agreed that civics had not developed and that ‘the overall picture was one of fading enthusiasm’ (Fahy Citation1984). The 1970 International Study on Civic Education (Torney, Oppenheim, and Farnen Citation1975) found that Irish students performed lowest or next to lowest on every subscale except for political institutions; they suggested that the Irish education system's emphasis on facts, memorisation, homework, standardised testing and citizenship based on developing good and responsible boys and girls rather than politically active citizens may have been responsible. A 1977 IPA report suggested using theme-based teaching, project work, discussion classes, role-playing and involving adult non-teaching members of the community (Hyland Citation1993). Despite this input, civics was often the last subject placed on the timetable, or the single civics period was allocated to an examination subject (NCCA Citation1993) or taught as one subject with religious education (RE) (Gleeson Citation2008). Torney, Oppenheim, and Farnen (Citation1975), however, found that students viewed civics classes as interesting but suggested that may be compared with their other classes.

McAleese (Citation1991) described the civics class as a filler, with vague instructions issued to the teacher about civic duties, information about the state, county council, Bishop Tutu or Nelson Mandela. Quizzes and videos from embassies were suggested methodologies, but students were often instructed to read their books. McAleese, however, outlined how civics could become a vibrant subject by promoting ‘Buy Irish’ and ‘Green Windows’ campaigns that would allow students to conduct interviews, produce posters and engage with local media. Nevertheless, such agentic actions of the civics teacher seem to have been the exception rather than the norm.

A general acceptance emerged that civics had failed and needed to be replaced rather than reformed (DES Citation1992). This failure was attributed to factors associated with being a pedagogic subject: lower status, insufficient class contact time, a lack of trained teachers, a lack of resources, principals not taking the subject seriously and exam subjects being viewed as more important (NCCA Citation1993). In the 1980s, the Curriculum and Examinations Board (CEB) recommended that a new subject – civic and political studies – replace civics (Houses of the Oireachtas Citation1986).

Civic, social and political education

The 1990s saw a period of rapid economic growth, and starting in 1997, the Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrat coalition government began to adopt a neoliberal economic model (Keogh Citation2005). In 1990, Ireland elected its first female president, homosexuality was decriminalised in 1993, two years later a referendum on legalising divorce was carried, and in 1997, the Freedom of Information Act was passed. The traditional authority of business, church and political leaders began to decline following a series of enquiries into the beef industry, clerical sexual abuse, industrial schools and payments to politicians. An increase in immigration saw people born outside of Ireland rising from 6% of the population in 1991 to over 10% in 2002 and a rise in the number of asylum seekers from 39 in 1992–10,938 by 2000 (Ruhs and Quinn Citation2009).

The green and white papers on education stressed the importance of promoting languages, European citizenship and an awareness of global issues such as the environment and developing countries (DES Citation1992, Citation1995). Against this background, in Citation1993, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA), which had replaced the CEB, published a discussion document on CSPE (NCCA Citation1993). The emphasis on exploring, examining and analysing through active methodologies differed greatly from the civics syllabus. The type of citizenship envisaged was active, participatory and reflective. Assessment was considered to avoid CSPE having a second-rate status. A whole-school approach and in-service training for teachers and school management were advocated to prevent a repeat of the in-school factors behind the failure of civics. Following a pilot programme in 1993–94, CSPE became a compulsory junior cycle subject in post-primary schools starting in 1997 and was allocated 70 h over the three junior cycle years (DES Citation1996). The proposals in the discussion document were implemented, and where possible, teachers were to opt to teach CSPE and be assigned to teach another subject to their class. Classes were to have a continuity of teachers at least in second and third year (DES Citation2001).

The CSPE syllabus (NCCA Citation1996) outlined a subject in the pedagogic tradition, but with assessment and certification, that emphasised active citizenship and developing skills by research/discovery activities, groupwork/discussion, simulation and action research. The course centred on seven key concepts taught in relation to the individual, the community, the state and the world. Minster for Education Bhreathnach’s (Citation1996) vision of students being capable of taking action, critically evaluating information, justifying opinions and accepting different perspectives reflected the participatory and justice-oriented models of citizenship. Wylie (Citation1999), however, notes the syllabus's lack of explicit reference to developing a critical and analytical approach to the teaching of citizenship, suggesting a justice-oriented approach was aspirational rather than integral.

In 1992, insufficient in-service training and the non-assessment of active and practical work in the Junior Certificate Programme (JCP) meant that the envisaged active methodologies were not widely used and that teachers had reverted to an academic focus in their subjects (Hanafin and Leonard Citation1996). Against this background and mindful of the experience with civics, external assessment was used to guarantee that active methods were implemented in CSPE. The concept-based examination accounted for 40% of the marks, and 60% of the marks were allocated to either a report on an action project or a coursework assessment booklet. This assessment differed from other subjects in the JCP because more marks were allocated to the non-examination element of the assessment and the examination was assessed at a common level, whereas in other subjects examinations were offered and higher and ordinary level, and in some cases at foundation level.

The DES supported postgraduate CSPE diplomas, universities provided CSPE as an elective in their higher diploma in education programmes, the Association of CSPE Teachers (ACT) was founded, and a CSPE support service was established to provide in-service training for teachers (Dáil Éireann Citation2000). Textbooks were produced, which Coleman (Citation2000) suggests helped CSPE gain more status among parents. State-owned bodies and NGOs produced resources for teaching CSPE. Teachers and principals were generally positively disposed to CSPE, and teachers overwhelmingly believed that CSPE developed students’ communication skills and promoted teamwork (Redmond and Butler Citation2004).

However, problems quickly surfaced. With principals finding staff unwilling to teach CSPE, inexperienced teachers were regularly asked to teach the subject (Coleman Citation2000). Teachers were often not timetabled for another subject with their class or had no continuity with the class (Coleman Citation2000; DES Citation2008–2017; Redmond and Butler Citation2004). Although principals reported that most teachers taught the subject for three years and were allocated to CSPE based on their personal interest in teaching it, timetabling constraints played an equal role in the allocation of teachers (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011). Murphy (Citation2008), however, found that only 20% of teachers had opted to teach CSPE, only 4% of CSPE teachers had been teaching the subject since its introduction, and there was a low level of collegiality among CSPE teachers. More positive views of CSPE were recorded in state-owned schools than in traditionally academic-focused voluntary secondary schools (Gleeson and Munnelly Citation2003; Murphy Citation2008).

Teacher training was also a problem, 92.4% of CSPE teachers had not taken an elective course in CSPE as part of their preservice training (Redmond and Butler Citation2004). In addition, 37.6% of CSPE teachers had no qualifications suited to teaching the subject, and although 98% of CSPE teachers had received some training, this appeared to be inadequate because their primary demand was training both in content and methodology (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011). Murphy (Citation2008), however, showed that only 52% of teachers received in-service training in CSPE. Active learning, the teacher choosing content, greater student autonomy in the action project and controversial issues were challenges in teaching CSPE (Harrison Citation2008). Some of these were new concepts for teachers, and it is difficult to see how teachers would embrace these challenges without comprehensive in-service training. Chief Examiners’ Reports published by the State Examinations Commission (SEC) highlighted a pattern of students submitting either action projects beyond the parameters of the course or identical reports (DES Citation2000; SEC Citation2005). This shows that teachers were unaware of the requirements for the action project, which suggests they had not received training.

In addition to training, teachers wanted more time allocated to teaching CSPE. With just one teaching period per week, the gap between lessons affected momentum (Coleman Citation2000; Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; Redmond and Butler Citation2004). Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel (Citation2011) highlighted the difficulties of switching to an innovative teaching mode with just one class per week. There were also problems with active methodologies such as classroom layout, teacher reticence, overreliance on textbooks and pupil indiscipline (Coleman Citation2000; Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; DES Citation2008–2017; Murphy Citation2008; Redmond and Butler Citation2004).

Students, too, had mixed attitudes towards CSPE. Many enjoyed the subject and rated it as useful, but others did not or saw it as worthless (Gleeson and Munnelly Citation2003; Nugent Citation2006). Duggan (Citation2015) showed that only RE was rated lower than CSPE by students in terms of its importance and value. Students recognised that time limitations impacted teachers’ ability to practise active democracy and get to know the class group, and schools’ emphasis on success in examinations saw students associate empowerment with individual success rather than with citizenship education (McSharry Citation2008). Students saw the benefits of political education for their democratic, social and political development but often found this in English class rather than CSPE (Duggan Citation2015). This indicated a need for more academically challenging material, as proposed by Lynch (Citation2000). However, students’ knowledge of civic affairs was quite high (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; Gleeson and Munnelly Citation2003); Ireland ranked seventh out of 36 countries in the ICCS study, and grades received in CSPE positively impacted internal efficacy (Murphy Citation2017). Chief Examiners’ Reports showed how 82.5% to 89.7% of candidates achieved A, B, and C grades and only 2.4% to 4.8% obtained E, F and NG grades (DES Citation2000; SEC Citation2005, Citation2009). The reports found students understood and were aware of topical issues and had an ability to engage in a personal way, to demonstrate a caring attitude towards others and to think critically. Despite tending to opt for safe topics, the action project ensured that students engaged in active participatory citizenship (Wilson Citation2015). Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel (Citation2011) ascribed the low levels of student participation to their research being conducted among second-year pupils, whereas the action project was generally conducted in third-year. This indicates that CSPE relied heavily on one aspect of the course to promote participation. However, students viewed the CSPE examination as insufficiently challenging, indicating that assessment did not automatically raise the subject's status (Murphy Citation2008).

Wellbeing

In 2012, Ireland began to emerge from the economic crash of 2008 that had seen increased emigration, an economic austerity programme and the government relying on financial assistance from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. Gender quotas for political parties were introduced in 2012 to boost women's participation in politics. Referendums in 2015 providing for same-sex marriage and in 2018 for abortion were carried.

In 2015, the NCCA launched a junior cycle profile of achievement (JCPA) to replace the JCP (DES Citation2015). Original proposals to replace state-certified examinations with school-based examinations (Quinn Citation2012) were unacceptable to the teacher unions. This led to a compromise JCPA that included state-certified examinations, classroom-based assessment (CBA) and other areas of learning (NCCA Citation2016). Apart from Irish, English and Mathematics, all examinations moved from assessing candidates at higher and ordinary levels to a single common level assessment paper.

The new JCPA contained a compulsory Wellbeing Programme, which included CSPE, social, personal and health education (SPHE), physical education (PE) and guidance. This move saw CSPE become a more pedagogic subject, with the external assessment being removed and replaced by a CBA. CSPE was now referred to as a short course rather than as a subject and the seven key concepts were replaced by three strands and 37 learning outcomes (NCCA Citation2016). From September 2022, the hours allocated to CSPE increased from 70 to 100 h over the course of the junior cycle (NCCA Citation2021). The rationale for CSPE being included in the Wellbeing Programme was to make links between individual and collective wellbeing (NCCA Citation2021). Bryan (Citation2019), however, cautioned that CSPE's presence in the programme risked promoting an individualised form of citizenship focused on responsibility.

Teachers were to be assigned to teaching CSPE with their prior knowledge and, because they were not expected to have specialist training in CSPE, were to be supported by schools to do continuous professional development (NCCA Citation2017). Unlike the 2001 circular letter (DES Citation2001), it did not encourage schools to allocate the teachers to another subject with their CSPE groups. Moreover, there was little evaluation of CSPE with the Chief Inspector's Report focusing on the other areas in wellbeing, PE, SPHE and guidance, which suggested that CSPE was seen as peripheral (DES Citation2022).

Although CSPE became a more pedagogic subject, the lack of a follow-on at senior cycle was addressed when politics and society was introduced as an optional subject for the Leaving Certificate in 2016. Unlike CSPE, politics and society is an academic subject worth points for the Leaving Certificate.

In 2009, the Teaching Council first produced the criteria for teachers to register in post-primary subjects (Teaching Council Citation2009). Teachers with a degree in sociology or politics and a higher diploma in CSPE or an elective CSPE methodology as part of a higher diploma in education were eligible to register as CSPE teachers. However, the revised criteria from 2023 meant that teachers could only register based on subjects taught to Leaving Certificate level. It was therefore no longer possible to register as a teacher of CSPE, but as a teacher of politics and society (Teaching Council Citation2022). The only area in the Wellbeing Programme where registration is currently possible is PE.

By 2017, some areas of strength were evident in CSPE. It was a compulsory subject, it was taught on initial teacher education programmes, it had external assessment and a subject association. CSPE promoted knowledge and understanding of current affairs (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; Gleeson and Munnelly Citation2003; Murphy Citation2017; DES Citation2000; SEC Citation2005, Citation2009). However, these strengths were outweighed by weaknesses. These included insufficient class contact, a lack of trained and interested teachers and poor attitudes towards the subject from all educational stakeholders. With CSPE's move to the Wellbeing Programme, the extra time allocation and a learning outcome-based specification may be beneficial for the subject, but the challenges may also grow with the end of external assessment and no possibility to register with the Teaching Council in CSPE or wellbeing. Having looked at the experience of civics and CSPE from its introduction to 2017 and as CSPE moves from being a hybrid pedagogic subject with an academic element to becoming a more pedagogic subject in the Wellbeing Programme without external assessment, a study looking at teachers’ views of teaching CSPE is pertinent.

Methodology

The present study is based on data collected as part of a larger survey conducted among CSPE teachers. The findings will refer only to the analysis of six open-ended questions in the questionnaire (Appendix).

The following research questions were formulated based on the research aim and on an analysis of the literature relating to CSPE:

What challenges do CSPE teachers identify in teaching CSPE?

How do these challenges relate to CSPE being a pedagogic subject?

Ethics approval was granted prior to data collection. All surveys were accompanied by a cover letter that informed the respondents of the purposes of the survey. The respondents gave their consent for the data to be used by completing the survey and all responses were anonymous.

The survey was distributed by post and online by Survey Monkey in October and November 2018. Postal surveys were addressed to CSPE coordinators in 40 schools, and a link to an online survey on Survey Monkey was emailed to the CSPE coordinator in a further 450 schools. The ACT circulated the online version of the survey to its members. The respondents were asked to return the postal questionnaires within two weeks. Reminder emails for the online survey were sent after six days, and a final reminder was sent six days after this. In total, 223 responses were received. Of the respondents, 69.5% (N = 155) were female teachers, and 30.5% (N = 68) were male teachers.

The response rate to the six open-ended questions was high with 206 respondents answering these questions. The depth of detail in the responses varied; some were very developed, others were brief but informative, and responses such as yes, no and n/a were excluded from further analysis. All other responses were analysed using thematic analysis. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) define thematic analysis as searching across a data set to find repeated patterns of meaning; they outline a six-phase approach, beginning by repeatedly reading the data, looking for patterns, generating initial codes and creating potential themes by a detailed rereading of the codes. From this process, seven themes were identified: status, relevance, lack of knowledge from home, social awareness, politics, elections and voting and sensitive issues. Phase four involved reviewing the themes. At this point, some themes were combined, and three main themes were identified: the challenges of teaching CSPE (status, relevance, knowledge from home, resources and sensitive issues), social responsibility and politics (elections and voting and politics). In phase five, the themes that were evident across the whole data set were named and defined, and items were categorised into subthemes. One theme, the challenges of teaching CSPE, was more prevalent than the other two. Because the focus of the present paper is on the challenges of teaching CSPE, phase six, which involved the analysis of vivid compelling extracts of the theme of challenges, will be examined in the findings.

Findings

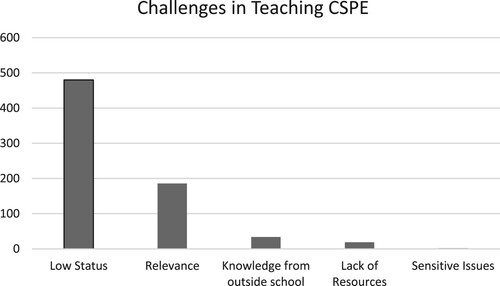

demonstrates the coding references for the five categories of challenges in teaching CSPE identified in the thematic analysis. Within these challenges, low-status (N = 480) was the dominant concern. Apart from relevance (N = 186), the figures for the other themes were comparatively small: limited knowledge from outside school (N = 34), insufficient resources (N = 19) and sensitive issues (N = 2).

Low-status

The overwhelming theme that was identified was the low-status accorded to CSPE. This was further divided into three subthemes: general low-status, role of the DES and role of school management. The first subtheme – general low-status (N = 91) – identified negative perceptions of the worth of the subject but did not elaborate on the origins of this low-status or on how it impacted the subject. The other two subthemes – the role of the DES (N = 289) and the role of school management (N = 100) – identified the causes and impacts of poor status.

The DES's role was most frequently cited as a cause of the low-status of the subject, and further subthemes were identified in this area. A general dissatisfaction with the department's role (N = 59) was expressed by many respondents, but they did not elaborate on this. Two areas dominated here: limited class contact (N = 105) and concerns about the removal of state assessment and certification (N = 96). Some benefits of the latter were mentioned (N = 29), but they were outweighed by concerns, which were more strongly expressed. CSPE's inclusion in the Wellbeing Programme was also referenced (N = 28).

The most common concern was the insufficient time allocated to CSPE. The lack of momentum, behavioural issues, difficulty getting to know students and inadequate time to get comprehensive work done were often referenced. The following quotes provide a flavour of such responses:

Once a week is too little to have any momentum in topics. (More time) would also help raise its status.

The timetabling is very poor. You cannot expect to teach the curriculum effectively with only a forty-minute lesson each week. Also, the exam component should not have been removed because it devalues the subject.

I feel that the biggest challenge with the new syllabus is keeping them interested in a subject where they don't have an exam. They understand that the whole idea of CSPE is important, but they want to spend their time on exam subjects.

It will mean no more action projects, which is a bad thing because they were the most effective part of the course.

I am worried that the subject will lose any value it has. The action project was a great idea, and none of that work will happen under the new assessment method.

I think that the lack of a terminal exam is a big problem. The project work has always captured their attention, and I think it is an integral part of the subject. We are always talking about taking action, and the project element allows them to do that.

CSPE's position in the Wellbeing Programme was also referenced. However, those respondents who elaborated on this did not comprehend the connection between CSPE and wellbeing or were dismissive of the claimed benefits:

It's losing any status now that it's not an exam subject. I can't understand the link with wellbeing really.

Now, for management, it's ticking the ‘wellbeing’ box. For me and hopefully the students, it is a practical subject that opens their eyes to issues and expands their general knowledge.

It is not seen as important by management of this school and only appears on the timetable because it is obligatory to make up the new junior cycle wellbeing hours.

The negative attitude that exists towards the subject is often displayed by teachers who are not qualified in the subject and lack the basic knowledge and interest to teach it effectively. As a result, this trickles down to the students, who, in turn, show no interest.

The same teachers seem to get timetabled for CSPE, SPHE, RE and other soft subjects, along with their own subjects. Too many subjects means not enough time/opportunity/headspace for adequate preparation for all. Others only sometimes, seldom or never asked to teach these subjects.

Make it a subject that teachers choose to teach rather than be taught by management. If I knew I would be teaching it every year, I would invest more of my time developing my resources for the subject.

I have CSPE on my timetable and NEVER received any training.

I wish that the CSPE teaching departments in all schools could be stabilised. It's like a revolving door with different teachers nearly every year, so the levels of expertise are not enhanced. This is what has held CSPE back for years. The Department of Education could have saved themselves a fortune if it was mandated that all schools have a cohort of dedicated CSPE teachers; the amount of money spent by support services that have come and gone would not have been necessary if this had been properly attended to. A great pity.

Relevance

The second major theme was relevance (N = 186). Unlike status, teachers saw relevance as a challenge that was within their power to overcome. The respondents outlined how they tackled the challenge of making CSPE relevant by focusing on engaging pupils, encouraging volunteering and helping older students register to vote. Although some respondents felt overcoming student disengagement was unachievable, the majority furnished examples of how they engaged students and, consequently, made the topics covered relevant. Donald Trump, for example, was widely cited as providing a hook to interest pupils and helping them see the relevance of politics. Frequent references were made to topical issues such as the US and Irish presidential elections, water charges, the abortion and same-sex marriage referendums. In addition, student councils and mock elections were cited as a means of promoting relevance. Some examples of responses included the following:

Once you engage them and they understand, then they feel very strongly about issues in politics: repeal, same-sex marriage and (the) presidential election.

Bringing in real-world examples of voting and the democratic process – such as the US presidential vote and the Irish presidential race … At a more local level, student council elections have demonstrated student interest.

Limited knowledge from outside school

Students’ limited knowledge from outside school was featured as a theme in a smaller number of cases (N = 34). The respondents referred to a lack of knowledge, exposure to or awareness of current affairs and government institutions. Many of the respondents noted that their students do not read or watch news reports; therefore, the only civic knowledge they gain is from school. The respondents outlined the need to question biased viewpoints and expose students to alternative perspectives and debates. CSPE's role in generating informed conversation on topical issues, which is frequently absent from pupils’ homes or social media activities, was also mentioned.

Lack of resources

Insufficient resources were mentioned, but infrequently (N = 19), and these responses were rarely developed, indicating that, in comparison, a lack of resources is not viewed as a critical challenge.

Sensitive issues

Surprisingly, teaching sensitive issues was mentioned only twice among all the responses. This challenge referred to the need to be mindful of students’ backgrounds when teaching certain topics. Issues such as abortion and water charges were referenced as topical issues to engage students rather than as sensitive ones.

Discussion

The findings will be discussed under three headings: how CSPE has been conceptualised and realised, limited teacher agency and CSPE’s place in the Wellbeing Programme.

How has CSPE been conceptualised and realised?

The aim of CSPE is ‘ … to inform, empower and enable young people to participate as active citizens at local, national and global levels based on an understanding of human rights and social responsibilities’ (NCCA Citation2016), which suggests a participative and personally responsible citizenship with hints of justice-oriented elements (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004). As part of the Wellbeing Programme, CSPE is tasked with promoting not only the wellbeing of the individual, but also society by focusing on key skills, wellbeing indicators and a learning outcome-based specification that allows the teacher to choose the content being taught.

In the findings, CSPE teachers identified the insufficient teaching time allocated to the subject by the DES as a major source of the subject's low-status. This supports previous findings that have identified similar concerns among teachers (Coleman Citation2000; Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; Redmond and Butler Citation2004). The limited contact time has been viewed as a demonstration that the subject is not an important element of the overall curriculum, supporting Jeffers’s (Citation2008) contention that the time allotted to a subject demonstrates where the department's priority lies. While the increased time allocation (NCCA Citation2021) will be of some benefit, it was not mandatory at the time of data collection.

It is significant that so many CSPE teachers were critical of the removal of external assessment. Their concerns were twofold: further reduced status due to a reverse academic drift as CSPE became a more pedagogic subject, and the harmful effects on participative citizenship. An analysis of civic knowledge scores, Junior Certificate results and internal efficacy suggests the benefits of CSPE to students (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011; Gleeson and Munnelly Citation2003; Murphy Citation2017; DES Citation2000; SEC Citation2005, Citation2009). Although the assessment guidelines (NCCA Citation2017) suggest that the CBA goes beyond a report on an action project, many of the respondents viewed this as considerably less influential than a Junior Certificate grade. It is debatable, however, whether external assessment conveyed status to CSPE. Students considered the examination to be of poor quality (Murphy Citation2008), although the action project may have led to greater participation, it is unclear whether it was optimal (Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel Citation2011), and many action projects were found to be safe and bland (Bryan Citation2019; Wilson Citation2015).

The DES's attitude towards CSPE impacts the outlook of school management, with teachers identifying how school management is complicit in diminishing the status of CSPE by staffing it with untrained teachers, who are often disinterested in the subject, and providing very limited planning time or upskilling opportunities. Gleeson (Citation2008) notes how the students’ views of CSPE were related to their teachers’ attitudes and how teachers’ attitudes were related to school management's attitude. The haphazard allocation of staff to CSPE and its negative impact on the status of the subject supports the findings from DES inspections and others (Coleman Citation2000; Murphy Citation2008; Redmond and Butler Citation2004).

In academic subjects, the subject association, examinations, the academic content and teachers’ identity as academic subject teachers mean these subjects have the support to develop and tackle challenges, such as the implementation of a new curriculum. These strengths are not available to pedagogic subjects. It is hard to imagine that CSPE can be successful without providing a foundation for dedicated and interested teachers who are afforded the opportunity of training and developing their expertise. Currently, there is no facility or incentive for CSPE teachers to do so. When 48% of mathematics teachers were found to be teaching the subject without the necessary qualifications, a professional diploma in mathematics for teaching was urgently established (Goos et al. Citation2021). This and similar professional diplomas in physics and Spanish were fully funded by the DES (Dáil Éireann Citation2022). Although the same problem exists with CSPE, there has not been a similar response.

Furthermore, failing to develop expertise and relying on untrained and disinterested teachers who have insufficient class contact time increases the likelihood that they will see citizenship solely through a personally responsible lens, a bland interpretation of citizenship that is reduced to the ‘3fs’ of fundraising, fasting and fun (Bryan and Bracken Citation2011). Duggan (Citation2015) found that CSPE failed to deliver informed and participative citizens, attributing student dissatisfaction with teacher quality to the teachers’ lack of training. It is difficult to envisage how a deeper understanding of the causes and consequences of and solutions to societal problems using a justice-oriented approach can be adopted without exposing students to academic concepts and alternative scenarios to enable them to critically analyse issues (Lynch Citation2000). A justice-oriented approach requires academic content and teachers capable of delivering it.

Limited teacher agency

Lynch (Citation2000) warns that to successfully teach a subject, teachers need expertise and the enthusiasm that comes from teaching a subject they really love. Interestingly, although relevance was viewed as a challenge, it was seen as being within the teacher's power to address. The teacher can use their expertise and judgement to design lessons and use resources that interest and educate. The fact that methodologies, resources and textbooks were not major challenges in the present study suggests teachers viewed them as areas that they could solve themselves.

Because the DES manages the curriculum and school management decides how it is applied in schools, respondents ascribed the responsibility for low-status to these two bodies. Many passionate responses indicated significant frustration among CSPE teachers in calls for trained teachers, teachers opting to teach CSPE, more professional development and concerns related to the removal of external assessment. There was a noticeable lack of suggestions from teachers as to how they can raise the status of CSPE. Only one respondent recommended that CSPE pursue an academic route by teaching political and sociological theories.

The learning outcome focus in the CSPE specification (NCCA Citation2016), and the removal of external assessment allow teachers to decide content without being tied to an examination. The freedom this offers was rarely mentioned in the findings. Suggestions as to how to deal with time issues were also not identified. Teacher-led means of providing additional exposure to CSPE outside the school-based environment, such as flipped learning or online platforms (O'Brien 2021), were not referenced.

McSharry and Cusack (Citation2016) identified how teaching experience and training are key to developing teacher confidence in teaching controversial issues and how the absence of in-service leads to teachers ignoring or adopting a minimalist approach to sensitive issues. An unexpected finding in the present study was how rarely teaching sensitive issues featured, indicating either a confidence or reticence in dealing with such issues. Although CSPE pedagogy courses are taught in initial teacher training programmes, there are no comprehensive programmes available to in-career teachers. A lack of training or experience in teaching CSPE may inhibit teacher agency.

Goodson (Citation1993) outlines how the push towards becoming an academic subject can be teacher or scholar led. There is a clear demand for greater status for the subject from the teachers, but there was little reference to how they could raise that status beyond their efforts to make the subject relevant and the desire to reinstate the assessment. Although some scholars have argued for more academic and critical content (Bryan Citation2019; Lynch Citation2000), little evidence emerged here of a similar push coming from the teachers. It appears that the teachers feel powerless in creating solutions to address this problem. This supports Goodson’s (Citation2014) assertion that externally driven educational change leads to indifference and hostility.

CSPE's place in the wellbeing programme

Bryan (Citation2019) suggests the link between CSPE and wellbeing and the form of personally responsible citizenship it purports to produce can promote an individualistic outlook of citizenship that exemplifies the neoliberal order.

It was noticeable in the findings, however, that the respondents were either unsure of why CSPE was part of the Wellbeing Programme or critical of the connection. This indicates that the rationale for CSPE's link to wellbeing has not been well-communicated. There was a strong sense of disengagement from wellbeing, and respondents did not outline how CSPE and wellbeing complement each other or how CSPE could develop the wellbeing of others.

CSPE's move into the Wellbeing Programme became the vehicle for removing assessment and explicitly made the subject a pedagogic one. The negative response to the Wellbeing Programme demonstrates antagonism towards it because of its impact on CSPE's status. As with teacher agency, the response to the Wellbeing Programme supports Goodson’s (Citation2014) argument that externally mandated decisions for the education system lack buy-in from internal stakeholders.

Conclusion

The current study aimed to identify the challenges CSPE teachers experience in teaching the subject and how these challenges relate to CSPE being a pedagogic subject. The findings have brought to light two principal challenges: the low status of the subject and the effort to make it relevant. The status issues are linked to a disconnect in how CSPE has been conceptualised and in how it has been implemented, this is compounded by a lack of teacher agency and by teachers’ scepticism towards CSPE's move to the Wellbeing Programme. These concerns impact the progress of CSPE as a subject because the teachers view themselves as having no role in its development, without training they are not subject specialists and finally because CSPE subject departments are staffed by teachers conscripted to teach it, there is limited development of in-school expertise.

Recommendations

The reconceptualisation of CSPE's as a pillar of the Wellbeing Programme has several identifiable benefits for the subject: it remains a mandatory subject at junior cycle, the increased time allocation allows for greater continuity in lessons, the learning outcomes provide guidance for teachers without being overly prescriptive and contemporary issues of relevance to citizenship education have been included. It is telling however that these strengths were rarely referenced in the findings. Many respondents were unaware or dismissive of the link with wellbeing and appear to view the changes in CSPE as a tokenistic reform. CSPE teachers demonstrate agency only in their teaching and view themselves as peripheral to decision-making with no forum to raise the problems with implementing the subject. The historical analysis has demonstrated that after each reconceptualising of CSPE little effort was made to address problems arising in the subject, many of which were linked to its position as a pedagogic subject. The minimal reference to CSPE in the Chief Inspector's Report (DES Citation2022) is another indication of a detached attitude to successfully embedding CSPE in the Wellbeing Programme. The DES needs to address the disconnect between how CSPE has been conceptualised and how it is taught by firstly outlining to CSPE teachers the benefits to the subject of being in the Wellbeing Programme and the removal of external assessment and secondly evaluating the implementation of CSPE in the Wellbeing Programme. Such evaluation must include teachers’ experiences of teaching the subject. However, CSPE is only one subject in the new junior cycle programme. If a similar lack of teacher agency exists in other subjects, there will be significant challenges in firstly gaining teacher acceptance of the JCPA and secondly ensuring a willingness to actively support and participate in implementing it.

While the inclusion of emerging issues in CSPE is welcome, it is difficult to envisage how CSPE teachers will properly understand and engage with these and other issues without having the requisite knowledge, training and interest. CSPE pedagogy courses provide training for pre-service teachers who opt to teach the subject. This study, however, reiterates the negative impact of allocating CSPE classes to in-career teachers who are disinterested and untrained in the subject. CSPE is very different to politics and society, the former is pedagogic, the latter is academic. A qualification fully funded by the DES such as with the professional diplomas in mathematics, physics and Spanish to upskill teachers interested in teaching CSPE must be provided. Moreover, some recognition by the Teaching Council of qualifications achieved in CSPE would act as a motivation. Such a move has the potential to create subject specialist to advocate for the subject.

Many teachers believe that school management's only interest in CSPE is satisfying the wellbeing criteria. School management must move beyond such detached attitudes to the subject and work to create functioning CSPE subject departments by encouraging and supporting professional development and by making planning time available, but especially by ensuring that there is a continuity of staffing where teachers opt to teach CSPE rather than being unwillingly assigned to teach it. These changes would allow CSPE to have a greater profile at school level, with CSPE subject departments staffed by teachers who have experience of teaching the subject, developed teaching resources and a genuine interest in the subject.

As a pedagogic subject, CSPE lacks the internal change motivation to enhance its status, as evidenced in the lack of teacher agency and the indifferent and negative response to the externally imposed Wellbeing Programme. Policymakers and school management must include teachers in evaluating the implementation of the subject, CSPE teachers must have the opportunity to become specialists and subject departments must be developed at school level to address the causes of status problems. Such reforms have the potential to create a cohort of interested subject specialists working to promote the development of CSPE. The history of civics and CSPE has shown that the challenges it faces are well known but because CSPE is a pedagogic subject they are continually ignored. Unfortunately, without a strong internal drive for change, it is unlikely to overcome these challenges.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

The data were gathered using a self-completion survey. A limitation of this method is that responses are based on espoused views and may differ consciously or subconsciously from the respondents’ practices (Argyris and Schön Citation1974). An ethnographic research approach would have seen the challenges from an external perspective. Similarly, survey responses do not allow for probing questions, such as in interviews. Case studies looking at how teachers make CSPE relevant, their own vision of citizenship education and school factors in the challenges in teaching CSPE would be beneficial.

The present study did not look at the respondents’ level of training. Cosgrove, Gilleece, and Shiel (Citation2011) find that most CSPE teachers had received some training, but these teachers wanted more in both content and methodology. Further studies on the type and quality of training provided and sought would be useful. Moreover, an analysis of trained CSPE teachers who no longer teach the subject should be undertaken, questioning the factors that influenced their decision to discontinue teaching the subject.

The respondents were not chosen by random sampling; teachers who responded to the survey were more likely to be interested in the teaching of CSPE or members of the ACT; therefore, the findings are not generalisable. However, many respondents expressed concerns that the removal of the action project risks diminishing the participatory aspect of CSPE. This aspect warrants further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gearóid O’Brien

Gearoid O'Brien lectures in the Teaching of CSPE in the Professional Master of Education (PME) in the School of Education at University College Cork. He is also a practising post-primary teacher.

References

- Argyris, C., and D. A. Schön. 1974. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bhreathnach, N. 1996. “Speech by the Minister for Education.” Paper presented at the launch of the Civic, Social and Political Education Programme for second-level schools, February 15.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bryan, A. 2019. “Citizenship Education in the Republic of Ireland: Plus Ça Change.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education, edited by A. Peterson, G. Stahl, and H. Soong, 1–14. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bryan, A., and M. Bracken. 2011. Learning to Read the World? Teaching and Learning about Global Citizenship and International Development in Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: Irish Aid.

- Cohen, A. 2016. “Navigating Competing Conceptions of Civic Education: Lessons from Three Israeli Civics Classrooms.” Oxford Review of Education 42 (4): 391–407. doi:10.1080/03054985.2016.1194262.

- Coleman, E. 2000. “The Role of the Regional Trainer in the Development of Civic, Social and Political Education in the Post-primary School: An Action Research Approach.” Unpublished master’s thesis, University College Cork.

- Cosgrove, J., L. Gilleece, and G. Shiel. 2011. International Civic and Citizenship Study (ICCS): Report for Ireland. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Department of Education. 1966. Notes on the Teaching of Civics. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Department of Education. 1970. Rules and Programme for Secondary Schools 1970–71. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Department of Education. 1992. Education for a Changing World: Green Paper on Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Department of Education and Science. 1995. Charting our Education Future: White Paper on Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Department of Education and Science. 1996. Circular Letter M1/96: Civic, Social and Political Education. Dublin: DES.

- Department of Education and Science. 2000. Junior Certificate Examination, Civic, Social and Political Education, Chief Examiner’s Report. https://www.examinations.ie/archive/examiners_reports/cer_2000/jc_00_cspe_er.pdf.

- Department of Education and Science. 2001. Circular Letter M12/01. Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE). Dublin: DES.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2008–2017. Subject Inspection Reports. Dublin: DES. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Subject-Inspection-Reports-List/.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2015. Framework for Junior Cycle. Dublin: DES. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Policy-Reports/Framework-for-Junior-Cycle-2015.pdf.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2022. Chief Inspector’s Report September 2016-December 2020. https://assets.gov.ie/219402/d70032eb-efdf-4320-9932-7f818341afe6.pdf.

- Dáil Éireann. 1967. Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 231. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1967-11-29.

- Dáil Éireann. 2000. Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 522. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/2000-06-27.

- Dáil Éireann. 2022. Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 1028. https://debatesarchive.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/debateswebpack.nsf/takes/dail2022110800086#WRCC06000.

- Duggan, P. 2015. “Citizenship Education in Irish Secondary Schools: The Influence of Curriculum Content, School Culture and Stakeholder Perspectives.” Unpublished PhD diss., University College Cork.

- Fahy, M. 1984. “Some Curricular Aspects of Social and Civic Education in Ireland, 1966–1984.” Irish Educational Studies 4: 146–162. doi:10.1080/0332331840040112.

- Fleming, B., and J. Harford. 2014. “Irish Educational Policy in the 1960s: A Decade of Transformation.” History of Education 43 (5): 635–656. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2014.930189.

- Frazer, E. 2007. “Depoliticising Citizenship.” British Journal of Educational Studies 55 (3): 249–263. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00378.x.

- Gillborn, D. 2006. “Citizenship Education as Placebo.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 1 (1): 83–104. doi:10.1177/1746197906060715.

- Gleeson, J. 2008. “The Influence of School and Policy Contexts on the Implementation of CSPE.” In Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, edited by G. Jeffers, and U. O’Connor, 74–95. Dublin: IPA.

- Gleeson, J., and J. Munnelly. 2003. “Developments in Citizen Education in Ireland: Context, Rhetoric, Reality.” Paper presented at the international conference on civic education research, New Orleans, LA, November 16.

- Goodson, I. 1993. School Subjects and Curriculum Change. 3rd ed. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Goodson, I. 2001. “Social Histories of Educational Change.” Journal of Educational Change 2: 45–63. doi:10.1023/A:1011508128957.

- Goodson, I. 2014. “Context, Curriculum and Professional Knowledge.” History of Education 43 (6): 768–776. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2014.943813.

- Goos, M., M. Ní Ríordáin, F. Faulkner, and C. Lane. 2021. “Impact of a National Professional Development Programme for Out-of-Field Teachers of Mathematics in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1964569.

- Hanafin, J., and D. Leonard. 1996. “Conceptualising and Implementing Quality: Assessment and the Junior Certificate.” Irish Educational Studies 15: 26–39. doi:10.1080/0332331960150105.

- Harrison, C. 2008. “Changing Practices Within Citizenship Education Classrooms.” In Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, edited by G. Jeffers, and U. O’Connor, 110–123. Dublin: IPA.

- Houses of the Oireachtas. 1986. Joint Committee on Cooperation with Developing Countries, Report No. 05 Development Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Hyland, A. 1993. “Address to the First Meeting of the Teachers Involved in the Pilot Scheme for the Introduction of Civic, Social and Political Education at Junior Cycle Level.” Paper presented to department of education/NCCA in-service course participants, Dublin Castle, December 9.

- Jeffers, G. 2008. “Some Challenges for Citizenship Education in the Republic of Ireland.” In Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, edited by G. Jeffers, and U. O’Connor, 11–23. Dublin: IPA.

- Kahne, J., and E. Middaugh. 2008. Democracy for Some: The Civic Opportunity Gap in High School (Working Paper 59). Washington, DC: The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning (CIRCLE).

- Kahne, J. E., and S. E. Sporte. 2008. “Developing Citizens: The Impact of Civic Learning Opportunities on Students’ Commitment to Civic Participation.” American Educational Research Journal 45 (3): 738–766. doi:10.3102/0002831208316951.

- Keogh, D. 2005. Twentieth Century Ireland: Revolution and State Building. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- Kirwan, L., and K. Hall. 2016. “The Mathematics Problem: The Construction of a Market-led Education Discourse in the Republic of Ireland.” Critical Studies in Education 57 (3): 376–393. doi:10.1080/17508487.2015.1102752.

- Lee, J. J. 1989. Ireland 1912-1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leung, Y. W., W. W. T. Yuen, and S. K. G. Ngai. 2014. “Personal Responsible, Participatory or Justice-Oriented Citizen: The Case of Hong Kong.” Citizenship Teaching & Learning 9 (3): 279–295. doi:10.1386/ctl.9.3.279_1.

- Lynch, K. 2000. “Education for Citizenship: The Need for a Major Intervention in Social and Political Education in Ireland.” Paper presented at the CSPE conference, Bunratty, Co. Clare, 29th September.

- Lynch, K. 2012. “On the Market: Neoliberalism and New Managerialism in Irish Education.” Social Justice Series 12 (5): 88–102.

- Manning, N., and K. Edwards. 2014. “Does Civic Education for Young People Increase Political Participation? A Systematic Review.” Educational Review 66 (1): 22–45. doi:10.1080/00131911.2013.763767.

- McAleese, J. 1991. “We Did Our Homework During Civics.” The Secondary Teacher 20 (3): 29–30.

- McSharry, M. 2008. “Living with Contradictions: Teenagers’ Experiences of Active Citizenship and Competitive Individualism.” In Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, edited by G. Jeffers, and U. O’Connor, 187–195. Dublin: IPA.

- McSharry, M., and M. Cusack. 2016. “Teachers’ Stories of Engaging Students in Controversial Action Projects on the Island of Ireland.” Journal of Social Science Education 15 (2): 57–69. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v15-i2-1947.

- Merry, M. S. 2020. “Can Schools Teach Citizenship?” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 41 (1): 124–138. doi:10.1080/01596306.2018.1488242.

- Murphy, D. 2008. “Civics Revisited? An Exploration of the Factors Affecting the Implementation of Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE) in Five Post-Primary Schools.” In Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, edited by G. Jeffers, and U. O’Connor, 96–109. Dublin: IPA.

- Murphy, P. 2017. “Unsettled in the Starting Blocks: A Case Study of Internal Efficacy Socialisation in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Political Studies 32 (3): 479–497. doi:10.1080/07907184.2016.1255201.

- NCCA. 1993. NCCA Discussion Paper: Civic, Social and Political Education at Post-Primary Level. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- NCCA. 1996. Civic, Social and Political Education Syllabus. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- NCCA. 2016. Civic, Social and Political Education: A Citizenship Course Specification for Junior Cycle. https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/4370bb23-00a0-4a72-8463-d935065de268/NCCA-JC-Short-Course-CSPE.pdf.

- NCCA. 2017. Junior Cycle Civic Social and Political Education (CSPE) Short Course: Guidelines for the Classroom-Based Assessment. https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/85185792-37f3-4249-be55-a0525aa850f8/CSPE_AssessmentGuidelines_Feb2017.pdf.

- NCCA. 2017. Junior Cycle Wellbeing Guidelines. https://ncca.ie/media/2487/wellbeingguidelines_forjunior_cycle.pdf.

- NCCA. 2021. Junior Cycle Wellbeing Guidelines. https://ncca.ie/media/4940/updated_guidelines_2021.pdf.

- Niemi, R. G., and J. Junn. 1993. “Civics Courses and the Political Knowledge of High School Seniors.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American political science association, Washington, DC, September 2.

- Nugent, R. 2006. “Civic, Social and Political Education: Active Learning, Participation and Engagement?” Irish Educational Studies 25 (2): 207–229. doi:10.1080/03323310600737552.

- Quinn, R. 2012. “Minister Quinn Announces Major Reform of the Junior Certificate.” https://merrionstreet.ie/en/news-room/releases/minister-quinn-announces-major-reform-of-the-junior-certificate.html.

- Redmond, D., and P. Butler. 2004. Civic, Social and Political Education: Report on Survey of Principals and Teachers. Dublin: Nexus Research Cooperative.

- Reichert, F., and J. Torney-Purta. 2019. “A Cross-National Comparison of Teachers’ Beliefs About the Aims of Civic Education in 12 Countries: A Person-Centered Analysis.” Teaching and Teacher Education 77: 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.005.

- Ruhs, M., and E. Quinn. 2009, September 1. “Ireland: From Rapid Immigration to Recession.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/ireland-rapid-immigration-recession#:~:text=Ireland’s%20economic%20boom%20during%20the,from%20outside%20the%20European%20Union.

- SEC. 2005. Junior Certificate Examination 2005, Civic, Social and Political Education, Chief Examiner’s Report. https://www.examinations.ie/archive/examiners_reports/cer_2005/JC_CSPE.pdf.

- SEC. 2009. Junior Certificate Examination 2009, Civic, Social and Political Education, Chief Examiner’s Report. https://www.examinations.ie/archive/examiners_reports/JC_CSPE_2009.pdf.

- Teaching Council. 2009. General and Special Requirements for Teachers of Recognised Subjects in Mainstream Post-primary Education. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/publications/registration/documents/requirements-for-degree-recognition.pdf.

- Teaching Council. 2022. Teaching Council Registration Curricular Subject Requirements (Post-Primary). https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/news-events/latest-news/2022/curricular-subject-requirements.pdf.

- Torney, J. V., A. N. Oppenheim, and R. F. Farnen. 1975. Civic Education in Ten Countries: An Empirical Study. New York: Halstead.

- Westheimer, J. 2019. “Civic Education and the Rise of Populist Nationalism.” Peabody Journal of Education 94 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2019.1553581.

- Westheimer, J., and J. Kahne. 2004. “What Kind of Citizen? The Politics of Educating for Democracy.” American Educational Research Journal 41 (2): 237–269. doi:10.3102/00028312041002237.

- Whiteley, P. 2014. “Does Citizenship Education Work? Evidence from a Decade of Citizenship Education in Secondary Schools in England.” Parliamentary Affairs 67: 513–535. doi:10.1093/pa/gss083.

- Wilson, M. 2015. “Citizenship in Deed: A Study of the Action Project Component in Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE) in Ireland 2001–2013.” Unpublished PhD diss., Trinity College, Dublin.

- Wylie, K. 1999. “Education for Citizenship - a Critical Review of Some Current Programmes in England and Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 18 (1): 91–102. doi:10.1080/0332331990180111.

Appendix

The thematic analysis is based on the following six open-ended questions that appeared on the survey.

Young people have little interest in politics and the voting process. Would you agree?

What is the primary purpose of CSPE in your school?

Schools are irrelevant for the development of students’ attitudes and opinions about matters of citizenship. Would you agree?

What would you like to change in the teaching of CSPE?

How do you feel the new method of assessment of CSPE will impact the subject?

What do you feel is the biggest challenge in teaching CSPE?