ABSTRACT

This paper presents findings from a research project that investigated the aspects of inquiry-based learning (IBL), specifically experiences of teacher inquiry, within initial teacher education (ITE) programmes. The participants in the project were four teacher educators and 127 student teachers with the teacher educators being the research team. The inspiration for the research was an interest in features of IBL in ITE. Firstly, opportunities for teacher inquiry, conceptualised by the team as ‘intrinsic inquiry’, where student teachers carried out inquiries as reflections on their practice. Secondly, student teachers experiencing, planning and reflecting on classroom inquiry, conceptualised as ‘modelled inquiry’. We hoped our research would be informative for colleagues in ITE, as we knew from experience in ITE that providing opportunities for inquiry meant reflection, and acting on reflection was more likely to occur. Findings revealed many ‘multiplicities of inquiry’ between intrinsic and modelled enquiry, which participants had a range of views of. This paper focuses primarily on the aspects of intrinsic inquiry in teacher education, which included teacher inquiry and many other types of aspects of inquiry as outlined. However, throughout the findings reported students refer to both intrinsic and modelled inquiry.

Aims and participants

The aim of the project was to discover more about inquiry-based learning (IBL) in initial teacher education (ITE) at Dublin City University (DCU), Stranmillis University College (SUC) and the Marino Institute of Education (MIE) as shown in . As outlined below, in both jurisdictions student reflection was required in ITE, and we knew, where we used them, that inquiry approaches in ITE provided more opportunities for a range of reflections. And so, the research team focused on teacher educator and student experiences in Geography, History and Science Education in MIE (taught together as Social, Environmental and Scientific Education, SESE) and Geography Education in DCU and SUC. However, students referred to other areas of learning on their programmes. These modules focus on the nature of and pedagogies of teaching different subjects. As a research team, we had varied backgrounds and experiences in education, through which we had developed a disposition to inquiry but still had many questions about it. We were aware, from our experience of teaching and research, that inquiry operated in different ways across ITE and on placement for students. After publishing on the students’ experiences of inquiry teaching on placement (Greenwood et al. Citation2022), this paper focuses on how we explored our own and our student teachers’ experiences and views of intrinsic inquiry in ITE. Including the impact of such practices on student teachers’ understanding, confidence and practice in the praxis of teaching.

Table 1. Participants in the project.

This paper describes some findings in relation to the following research questions:

How do our ITE modules present intrinsic IBL to student teachers?

What impact does intrinsic inquiry in teacher education have on our student teachers’ understanding, confidence and practice?

We carried out the research with an aim to improve experiences of teaching and learning for us as teacher educators and for our student teachers. However, we also hoped informed insights arising from investigating these questions about IBL would contribute to the development of ITE programmes, to further possibilities to enhance programmes by incorporating a range of inquiry pedagogies into teaching. This paper is structured to outline definitions of IBL, including within teacher standards and curriculum in RoI and NI, and review research on IBL in ITE, before outlining the research project and its findings.

IBL definitions

IBL, whilst contested and debated, is generally recognised as pedagogies that draw on learners’ curiosity to investigate a topic or issue (Arnold et al. Citation2014). However, definitions of IBL do vary, some see it as a philosophy of teaching, others as a series of pedagogical practices that provide opportunities for learners to investigate a question or hypothesis (Short Citation2009; Roberts Citation2010). Short described inquiry as a stance on curriculum, which is as much about how we live as learners as it is about what we learn (Citation2009). Such stances mean that central to IBL is a recognition that the learner has an influence on the aim, scope or topic of their learning (Short Citation2009) and this can vary the intention and actions of teachers and learners (Roberts Citation2010). In practical terms, inquiry is often depicted as a set of recurring learning events commonly referred to as the inquiry cycle (Short, Harste, and Burke Citation1995; Roberts Citation2013). In relation to teacher inquiry, IBL is defined as an intentional study of one’s own professional practice (Cochran-Smith and Lytle Citation1999, Citation2009). It is embraced across many education systems as part of teacher education (Darling-Hammond Citation2021), including Ireland. However, in ITE, inquiry is generally enhanced by involvement with a community of learners, each learning from the others in social interaction (Lotter, Yow, and Peters Citation2014). There is also evidence that such stances and practices can be nurtured for teachers (Kroll Citation2005).

Inquiry in teacher standards and school curriculum in Ireland

Inquiry is promoted and required at different phases in the RoI and NI education systems. Related to this paper are the references to inquiry in teacher education that are referred to in teacher standards, requiring reflective professionals who can draw on a range of experience and research to develop their practice (Lifelong Learning UK Citation2009; Teaching Council Citation2020). Teacher inquiry is specifically mentioned in the NI standards, with the requirement that teachers use well-developed skills of inquiry, to inform their professional practice. And in the RoI, student teachers are asked to use the Céim standards as a tool to support their own development, including reflective practice and inquiry pedagogies (Teaching Council Citation2020, 10), although it is not clear if this is referring to their learning or that of their own students in school. In both jurisdictions, teachers are also required to promote inquiry in their classrooms. In the RoI, there are requirements for longer placements to provide opportunities for ‘more reflective, inquiry-oriented approach to the school placement and facilitate the development of the teacher as reflective practitioner’ (Teaching Council, 17). In NI teachers are subject to the ‘promotion of student-centred learning and creative teaching environments’ (LLUK, 3).

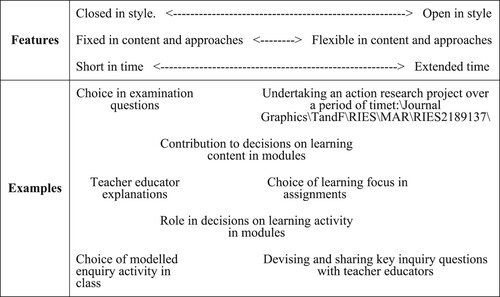

A representation of some layers and places for IBL in ITE is presented in . Student teachers experience IBL in university modules, where there are opportunities provided for it, both intrinsic and modelled. However, early conversations amongst the research team revealed more varied views and experiences of IBL in our ITE programmes and modules than the four quadrants of . Within the table, we have outlined possible definitions and examples of inquiry that occur in ITE, recognising that there is an overlap between these. In this study, we explored these multiple layers and types of inquiry as an intrinsic component of student learning about the roles and practices of teaching and learning in schools. This layered experience of IBL is referred to here as the ‘multiplicities of inquiry’, as there were many variations on this table, as explored below. These types of IBL were explored to help us develop practices, our own as well as that of others in ITE.

Table 2. Possible definitions and examples of intrinsic inquiry in ITE.

Theory and research on IBL in ITE

Theory and research on IBL in ITE tends to explore models, scope and practices as well as student attitudes to it. As outlined in the opening section of this report, IBL is significant for student teachers as it can encourage curiosity and criticality, to ‘problematise their own learning and to seek solutions through critical reflection and through in-depth study of theoretical readings’ (Hulse and Hulme Citation2012, 313). This resonates with critical educational theories such as the work of Freire and colleagues, who advocated that ITE programmes should encourage epistemological curiosity, asking teacher educators to create ‘pedagogical spaces where student teacher become apprentices in the rigours of exploration’ to ensure teachers were skilled (Freire and Macedo Citation1996, 53). As lecturers, taking inquiry stances can enable student teachers to develop their understanding through more opportunities for reflection of the complex relationships between theory, policy and practice in teaching (Dickson Citation2011). However, there is to a degree, a continuum of experience of IBL in ITE, and for some student teachers there are few opportunities for it, and even where they are learning about classroom inquiry, sessions can be didactic (Lotter, Yow, and Peters Citation2014). The types of activity students referred to, can be represented along a continuum is illustrated in part , indicating experiences in ITE could be considered more open or closed in terms of inquiry pedagogies. Although each of these can vary in terms of being inquiry in nature, according to how they are presented and carried out.

There has been an examination of students’ experiences of IBL (Levy and Petrulis Citation2012) as well as impact on student learning outcomes in ITE (Justice, Warry, and Rice Citation2009). From the research available, there is some evidence that students gain when their ITE programmes are characterised by practitioner-based and modelled IBL, with there being more research on the former. For example, Goodnough (Citation2011) concluded that research activity becomes meaningful to an individual when they are able to choose for themselves what they want to explore and how. Dickson and colleagues found students in ITE were able to identify their own learning trajectory, which had the effect of personalising their learning; this gave them a sense of agency in their external environments (Citation2011, 272). In Finland, Byman et al. (Citation2009) found that students commented on a strong sense of revelation which occurred when their reading aligned closely with their classroom experience. Overall, Byman and colleagues’ research found that engagement in practitioner inquiry facilitated student teachers’ professional learning, as 90% agreed that they had learned something from the experience (Byman et al. Citation2009). Even though 32% found the experience negative, they still agreed it had been of benefit to them (Citation2009). They concluded there was potential and willingness among the students to increase the research-based approach at the everyday level of the courses (Citation2009). Van Katwijk, Jansen, and van Veen (Citation2021) found this was the case with Dutch students, and concluded IBL in ITE was valuable training, but interestingly, that their students did not think it was something they would carry out in the future. In terms of IBL once qualified, there is evidence that the hyper socialisation of teachers (Mitchell Citation2020), as they can and do draw on many sources of information for their practice, which may mean space and time to think through in an inquiry manner on their practice is limited.

This is not to say IBL in ITE is universally accepted or valued. Byman and colleagues found students were initially apprehensive about engaging in research although were positive about the final outcome (Citation2009). In addition, a study of teachers also found similar resistance, particularly amongst science graduates (Bryant and Bates Citation2010). It is ideal that student teachers can research about their own practice and that of others (Hulme and Cracknell Citation2009), and this is required in ITE programmes (Teaching Council Citation2020). And there is evidence that IBL in ITE is most effective when it is focused. For example, Hulse and Hulme (Citation2012) found that a significant factor in students’ success was their ability to keep their research firmly focused on a specific intervention into their own teaching.

Overall, there is a range of interpretations, experiences and views of IBL in ITE, with a corresponding range of activity considered to be inquiry in both programmes and modules. Whilst there is a lack of systematic research in the area, it appears that embedding IBL in ITE means that student teachers have more opportunities to engage with the process of teacher inquiry (Wirkala and Kuhn Citation2011).

Research methodology, methods and design

As outlined above, we sought to find out how ITE programmes present IBL to student teachers and what impact the multiplicities of inquiry have on their understanding, confidence and practice. Research methodology broadly followed a model of collaborative action research (Kemmis Citation2009), consisting of a process where researcher team collaboratively planned, observed, reflected and acted upon their findings. As a community of practice, reflection was intrinsic to the research process occurring at each meeting we held (Simmons, McDermott, Eaton, Brown and Jacobsen Citation2021). The research design was subjected to ethical review and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at each institution. Participants gave informed consent prior to participating in discussions, surveys or focus group interviews. Participation was voluntary and student teachers retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time. All data were anonymised and stored in secure files.

At the beginning and the end of the project, each researcher submitted a written reflective piece on inquiry and how they used it in their teaching. With these, other notes and journals and the conversations throughout the project, TEs reflected on their own and each other’s practises and experiences, through shared critical thinking. In addition, the 10 research group meetings provided ongoing opportunity for critical reflection through discussion and dialogue.

A convenience sample of student teachers completed brief initial survey questionnaires relating to their views and experiences of IBL. From these, the final questionnaires were devised collaboratively by the research group and delivered to student teachers in , as can be seen 127 survey responses were received. All responses were anonymised, with quantitative analysis via SPSS to enable descriptions of patterns and relationships.

Student teachers from each of the team’s modules volunteered for interview, and in each case interviews were carried out by members of the team who were not involved in the teaching of those modules. Interviews were conducted in person with student teachers at their institutions and were recorded using an Olympus WS-321 digital voice recorder. A semi-structured interview format was employed, which provided a framework for the interview but allowed the student teachers to set the tempo and order of conversation and catered for the emergence of unexpected themes (Erlandson Citation1993). The interview schedule was based on concepts derived from the literature and the researchers’ own fieldwork and experience. Therefore, questions were asked of the students’ experiences of and attitudes to inquiry at school as children, in college and on placement. Groups ranged in size from 4 to 7 student teachers, and interviews were about 60 min in duration.

Audio recordings were transcribed, with the transcriptions read independently and coded by each member of the research team. Collectively, we then met to identify dominant and recurrent themes, and these were combined to constitute categories of meaning. This meant that the constant comparative method was used for data analysis (Marshall and Rossman Citation2010) and then re-evaluated. Codes were grouped to create the categories described in the findings below, which were then consolidated again to answer the original research questions, in the final conclusions section.

Findings from research team’s data

Within this section, the findings from the data collection are presented in relation to the team’s experiences, through the peer observation visits and researcher reflections, as well as the student teachers’ perspectives, through the student surveys, and student focus groups.

Researcher peer observations

As outlined above, the peer observation visits enabled practices to be discussed and observed, with a view to learning critically, from each other. Following the pilot session, the significance of pre- and post-briefing sessions to reflect became apparent. An inquiry-based observation framework facilitated consistency of categorising data collated and eased the process of articulating observations. There was a fluidity of movement among the different ‘modes’ of inquiry within modules, which sometimes made it difficult to complete the observation framework as originally devised. Through observing each other we noted that multiple inquiry pedagogies were incorporated into our teaching, although all were limited by programme structures and timings. Overall, the impacts of observation and discussion in the peer observation visits led to evaluating our own and others’ performance helping each of us to critically review our focus on our practice.

It was evident in the observations that inquiry was most common where student teachers were the inquirers. In most seminars observed there were opportunities for student teachers to work as children, for example in experiencing inquiry pedagogies whilst investigating the college grounds or locality. Next most common was student teachers experiencing and reflecting on and planning for IBL in schools. The least common was student teachers having the opportunity to investigate aspects of teaching most pertinent to them. This occurred only to a certain degree; for example, whilst the research team all supported this intrinsic inquiry, we noted that opportunities to provide it were severely constrained by the limited time for our subject areas as well as high student numbers. We were also limited by the requirement for clear learning outcomes and pre-planning for all modules. Specialism modules allowed for a greater level of collaboration between student teachers and teacher educators, creating space for intrinsic inquiry. For example, one researcher noted that, during observation of a specialism module, the teacher educator ‘shares the course learning outcomes with the students, to illustrate the confluence between the student and the teacher educator objectives’ (MIE researcher). Due to the differences in the student groups, programme focus and subject areas of the seminars observed, ‘each of the 3 lessons observed to date have been so different from each other’ (SUC researcher). Whilst it may have been easier to draw more definitive conclusions had the sessions observed been more similar, it was both beneficial and encouraging to observe and identify commonalities, such as a focus on problem-posing and problem-solving; encouraging critical thinking; the use of interactive pedagogies, in our approach to IBL across a broad range of circumstances.

Researcher written responses

From the initial reflective pieces submitted by each researcher on the project, entitles ‘How I use inquiry in my practice’, it became apparent that, although we each had different conceptions of IBL, broadly speaking our understanding of the characteristics of inquiry was similar. We were committed to teaching through inquiry by creating experiences for students that were conceptual, collaborative, questioning, learner-led, critical and analytical as shown in . As can also be seen in the table, inquiry was evident in modes of assessment: assignments were often based around research investigations. In some cases, this was intrinsic inquiry, such as an action research project; at other times it was both intrinsic and modelled inquiry, such as an investigation into a locality.

Table 3. Research design for the project.

Challenges identified by the researchers included time constraints and the tension between structured and open inquiry. For example, as one noted ‘I always feel pressured to cover much with little contact time; this is where I struggle most - deciding what is absolutely required, and when to just go with the flow’ (MIE teacher educator). And another that, ‘the scope for using inquiry in the general … modules is limited by time and numbers of students, but it is not impossible!’ (MIE teacher educator).

In our retrospective reflective pieces, entitled ‘What has changed in my practice through the course of this project?’, the team independently identified several common elements on which this research process has had an impact. One was a recognition that we may need to be more explicit about the IBL that is going on in our classrooms. Each researcher also recognised that, despite a shared belief that inquiry is about learner responsibility and agency, there may be limited opportunity to practise this in a real sense in much of our teaching. All of the team expressed a desire to increase the amount of student agency and responsibility within their modules. The team also team commented on the value of having the time and opportunity to engage with colleagues, both through peer observation and through collaborative reflection.

Findings from student teachers’ data

Questionnaire data

To discover student teachers’ views and experiences of IBL, 127 student teachers were surveyed. As shown in , all were in Year 2 (76 students, 60%) or 3 (51 students, 40%) of their programmes. Most of the student teachers (94, or 74%) were studying in the RoI, with 33 student teachers (26%) studying in NI, reflecting the balance of the student numbers and research partners in the project. Student teachers noted the way IBL appeared in varied ways in their ITE modules, both intrinsically and modelled, as well as varieties of these. 55% of student teachers agreed or strongly agreed that their teacher educators use IBL to model classrooms on their modules. However, only 21.8% of student teachers agreed or strongly agreed that their teacher educators involve them in the planning of their modules, a key aspect of intrinsic IBL in ITE. This is echoed in student responses to the statement ‘I have a say in how my module is taught’, with 66.1% of student teachers disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with this statement. Overall, it appeared teacher educators were teaching through inquiry in very limited ways but were expecting their students to use it far more on school placement.

Interview data

The interview data revealed a range of descriptions and understandings as well as varied attitudes to teacher inquiry in ITE. The students also recognised a range of limitations and complexities of inquiry and some tensions for teacher educators and themselves as noted in . From the outset the importance of IBL to their teacher educators was highly evident, as one DCU student immediately joked, ‘History, Geography, Science; definitely would have been the main areas where we did inquiry. They were always on about it!’.

Table 4. Opportunities and frustrations for teacher inquiry in ITE as described by the participants.

Descriptions and understandings of teacher inquiry

Within many of the interviews, there were descriptions of intrinsic, modelled and many other variations of inquiry, as noted in . The collaborative nature of IBL in class, and the importance of such positive relationships within groups, as another DCU student reflected, ‘I think it’s a lot of learning from each other, especially in the class. People always share the experience of placement, and things like that, and it’s useful. It is valuable peer learning’.

In terms of intrinsic inquiry, student teachers noted how they were given the opportunity to have a role in the design and delivery of modules in advance through collaboration with teacher educators as we expected. Their descriptions revealed different ways lecturers scaffolded within the IBL process for them, as one student described for Geography:

At the beginning of every year our lecturers just asked us what we wanted to get out of the specialism, and then they built the specialism around that and tried to facilitate what we wanted to get out of it. I thought that was a nice way to do it. Apart from that I’m not sure if there was much more.’ (DCU student).

Overall, the most referenced aspect of IBL was modelled inquiry, where classroom inquiry was experienced by the students within teaching, learning and/or assessment. The student teachers described how, in some cases the inquiry activity was carried out first, to get the student teacher to begin thinking about inquiry, but in most cases student teachers took on the role of ‘inquiring child’ after they had been introduced to theories and models of inquiry. However, this type of IBL had elements of intrinsic inquiry, as many of the students described how they had elements of choice in what and how they investigate key aspects of teaching for assignments, representing an intrinsic inquiry for the students. As one SUC student described, ‘something you would experience in a variety of different modules, definitely in education this year, we got to pick age groups to specialise in and then those questions are different as well’. There was also evidence of modules where the student teachers were investigating a topic or place with a view to teaching about it. When asked if teacher educators in college had supported them in using IBL in their teaching, a number of examples were given across subjects. This was noticed in both core and elective modules, with this example also showing how students tended to conflate IBL with outdoor work:

Last year we did Local Studies, a mixture of History, Geography and Science. We did a study of Drumcondra, I felt that was really the most inquiry we had done. It was interesting because you had classes, then you had to go out and find out more information yourself. For Local Studies, there’s no other way to find the answers unless you go out. So that was a good way of doing it. (DCU student, referring to a core module)

Some of the groups agreed that a greater degree of intrinsic inquiry in ITE could increase students’ scope and flexibility, leading to significant reflection about teaching. There were also times within their modules where intrinsic and modelled inquiry came together, which was particularly evident in relation to how resources were used. As one SUC student noted, ‘in literacy they always give us the practical resources especially for phonics they let us play about with the packs and the letters. They get us to be the pupils to show us how you would really do it’. However, students did not simply note IBL in terms of moving their own practice on, they also described how they were instrumental in the reflection dimension of teacher educators work. In fact, there were more such references than to current, intrinsic IBL.

Overall, student teacher opportunities for IBL were quite bounded, often limited to some shaping of modules at the beginning of the module or in assignments, including projects. They noted that assessments were sometimes an inquiry themselves with student teacher being required to investigate an issue, problem or question of their own.

Attitudes to teacher inquiry

Within the data were descriptions that included students attitudes to teacher inquiry, with some of the students opportunities and frustrations noted in . As one MIE student noted, ‘some lecturers did teach in that way and you really saw the difference with the engagement. It could have been something small but people seemed to be more engaged, or confused!’ Despite that degrees of choice, are a very limited version of inquiry in teacher education, it was still viewed positively with the importance of relationships being noted by one DCU student, ‘the PE specialism have a bit of choice, they would have very good rapport with their lecturers. I think that’s a good thing, when you have the relationship with the lecturers in your major specialism’. As noted above, in other cases the scope of IBL was limited to essay choices, but again this was viewed positively and linked to classroom practices. As a MIE student noted,

In History of Education we picked our own essay titles, doing your own research and you’re coming back and putting it in. It’s like your version of children going off and researching their bits, coming back and writing a report.

You’re thinking, ‘I wouldn’t want to sit here and listen to someone for x amount of time so why would a child?’ So you should get them up and get them moving. It was mainly with the curriculum subjects, rather than big lectures, in PE, History, Geography, those subjects.

Issues, opportunities and tensions of teacher inquiry

The student teachers noted issues in inquiry, as outlined in many of these were opportunities but there were also frustrations. The students also recognised the tensions between the need for teacher educators to teach student teachers the many aspects of the ITE programme, and also the wish to model good practice, giving student teachers a say in the design and implementation of modules, As one MIE student noted. ‘Everything we learn seems to be pointing towards letting the children figure things out for themselves. But we remarked that it seemed like some of our lectures wouldn’t have that format’.

The student teachers also had thoughts about the equality of access to learning about IBL pedagogies in ITE. For example, the student teachers at DCU wondered if IBL approaches were being used in other subjects or areas not represented in the focus group students. The SUC student teachers were concerned that they as Geography/History specialists, might be the only student teachers who had discussed and experienced IBL at length in university and in schools or, at best, were using the term for methods they were using already:

I feel like we are the only ones who will have an understanding of inquiry-based learning even though it is done in literacy to a point and in science it’s not explicitly talked about - I suppose in science it is explicit. I feel if I was to say to somebody who’s not in our geography/ history class something about inquiry-based learning they would look at you and think ‘what’s that?’ when it’s really not that complex at all. I mean they’ll probably do it themselves and not realise that they’re doing it.

Some of the subjects did inquiry-based learning and the assessment was inquiry-based, whereas some subjects had assessment which was the old fashioned, written exam style assessment. I think in order to have inquiry-based learning, the assessment has to somehow marry with that and I think that’s the difficulty colleges have really.

I think there has to be a balance between the inquiry and teaching them what they have to do. You have to summarise and that’s what the teacher educators do here. So, a lot of them do have a small component [of IBL].

Conclusions

This project aimed to explore and examine IBL, specifically elements of teacher inquiry, within in ITE. This was carried out with a view to strengthen and extend the use of such methodologies in teacher education in NI and RoI, reflecting the emphasis on these methodologies across both education systems. Within these final conclusions, we return to summarise findings under two headings tied to the research questions presented at the start of this paper:

How ITE modules present intrinsic IBL to student teachers

The first research aim was to find out about how IBL was presented and received in ITE. This was firstly investigated both through individual reflection and through observation of the teaching of the four researchers by each other. From this data, there was evidence of shared interest in the area of IBL; although there were differences in the researchers’ approaches to teaching, it is not clear if in the approaches to teaching, although it is not clear if this was mostly because of the differences in the modules examined. A major benefit of the observations identified by all four researchers was that they facilitated valuable opportunities to discuss, provide encouragement and to critique their practice. It was noted how rare such opportunities were, even with colleagues in our own institutions. As data was limited to the four researchers and our students involved, we have been cautious about drawing wider conclusions. However, we hope the findings provide interesting issues for discussion with our colleagues and initiate further research.

The second aim was to investigate how students experienced IBL in their modules. We developed our thinking beyond this initial ‘two-level model’ towards an understanding of the multiple inquiry modes which exist in any given learning environment. Our revised thinking was encapsulated our focus on how multiplicities of inquiry best be incorporated into ITE courses at teacher education and classroom levels. Arising from our observation visits, three inquiry modes were particularly noted in our ITE modules. We described these as ‘student as learner’, ‘student as teacher’, and ‘student as enquirer researcher’. We recognised that identifying these different modes and getting the student teacher to distinguish between, and more importantly to make connections between them was valuable. This echoes Short’s view, mentioned earlier, about inquiry ‘reaching beyond current understandings’ (Short Citation2009, 12). In some responses during the focus group interviews, student teachers demonstrated a vague understanding of intrinsic IBL. They tended to have emphasis on choice, agency and active learning, but at times a lack of awareness of the importance of reflection and action. We also noted how students were expected to teach through IBL on Placement, but their own teacher educators were not necessarily using such pedagogies to teach them. Thus, we as researchers now recognise that we need to demonstrate the full process of inquiry, and make the connections between the multiplicities of inquiry more explicit in our own teaching.

The impact of intrinsic inquiry in ITE on student teachers’ understanding, confidence and practice

This aspect was investigated mostly through the questionnaires administered to the student teacher and through focus group interviews. It was evident that student teachers were positively disposed towards IBL and could see the benefits of it. They viewed themselves as having greater freedom and agency with inquiry and that the children they were teaching were more motivated. However, at times they did over-associate having a choice as being inquiry, when this was not fully the case.

However, there seems to be a strong link between the positive attitudes of the student teacher towards any aspects of IBL and their experience of inquiry within their ITE modules. Student teacher expressed confidence in the benefits of inquiry, and their ability to use inquiry in their teaching, based on their own learning in teacher education. This is reflective of the research literature, which indicates a relationship between modelling of inquiry, student teachers’ self-efficacy and their positive attitude to a range of pedagogical approaches (Ross, Bradley Cousins, and Gadalla Citation1996; Swars and Dooley Citation2010).

While the survey responses indicated that the majority of student teacher felt they had little involvement in the planning of their modules, or little say in how they were taught (indicators of intrinsic inquiry), within the focus groups student teacher gave examples of a number of ways in which they were given opportunities to shape their modules. Overall, however, students cited few examples of any type of IBL in modules beyond the subject areas of History, Geography and Science. The researchers thus realise that they themselves may be the main conduits for IBL within their institutions and have little knowledge of how other colleagues address inquiry, if at all.

Final conclusions and recommendations

There are several conclusions that can be drawn from this research. All of these are tentative, as this research was carried out by just four researchers with their students. And we recognise many are possible avenues for more in depth investigation through research in ITE. However, the weight of evidence from the project allows us to make the following conclusions:

Firstly, it is clear that a community of inquiry has emerged among the authors as researchers. Discussion and dialogue were integral to the project (DeWitt Citation2003), and our pursuit of new understanding was a shared process, based on willingness to listen and respond to others’ perspectives. Through observing each other in a teaching and learning environment, we gained deep insights into each other’s ITE programmes, and how the process of supporting student teachers worked in different settings. The research processes were enriched by drawing our student teacher into the project, through interactions in classes, interviews and questionnaires. Our willingness to question our own and others’ practice and our openness to observation and follow-up discussions, all increased the criticality of our research process. We hope that in sharing this finding further such communities of inquiry develop in teacher education.

Secondly, through this research teacher educators and students recognised that there is a multiplicity of inquiry stances, pedagogies and strategies used in our ITE modules. This represents a shift in our thinking from the conceptualisation of inquiry in ITE as a broadly ‘two-level model’ towards a ‘multiplicities model’ of inquiry in ITE. This finding emerged early in the project, arising primarily from discussion before and after peer observation sessions. The interviews with students compounded this thought but also expanded our views of IBL in ITE. This has implications for practice in that it may be that we need to be more explicit about these multiplicities of inquiry with our student teachers in order for them to fully understand and benefit from inquiry in ITE and in how they enact it in their classrooms. We hope this discovery helps others involved in teacher education to consider the range and type of IBL they use in their modules.

Thirdly, it is clear from both the quality and amount of responses from student teachers, that IBL is something they are expected to learn about and teach through on school placement. And yet, it is something that their teacher educators do not use to the same extent in their own practices. Referring back to , the student experience tends to be to the left of the continuum, but they are expected to teach to the right of it. This contradiction of practice is a feature of ITE that needs to be questioned and reviewed.

Finally, the research highlighted the impact of IBL experience on student teachers. The research suggests that student teachers appreciate planning of ITE programmes and modules that embrace and enact teacher and modelled inquiry as well as all the other multiplicities of inquiry explored above. However, it was evident that opportunities for students to enact inquiry in ITE are somewhat limited. It appears that ITE tends to favour content over curiosity. Overall the research led to a greater understanding of how pedagogical practices can contribute to the learning experiences of student teacher to help to prepare them for a career in education. We hope that opportunities we provide for our students to work as curious professionals in ITE will encourage their ongoing professional development as teachers.

Arising from this study, we recommend that research into all aspects of IBL described in the findings of this work. This should be an ongoing, iterative process for teacher educators and students which involves a high level of criticality, reflected in engagement with student voice, open communication and critical questioning. Within each institution, the limited opportunities for intrinsic IBL compared to modelled IBL needs to be reviewed. We also recommend continued collaborations between institutions in relation to IBL in teacher education, to enhance practices. We also suggest expanding teacher inquiry projects between schools and universities, to help embed teacher inquiry in educational systems across subjects. In conclusion, this research has shown student teachers appreciate having an inquiry stance in all aspects of their professional lives, in both how they progress through their careers. We hope that this key finding will contribute to the ongoing conversation about inquiry in teacher education and our schools.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our thanks to the students who took time to participate in this study. Thank you also to the members of the Ethics Committees in all institutions for taking the time to review our proposals. We also wish to thank all the students who gave their time and thoughts for the project. Finally, we wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers of this paper, your support and suggestions were very much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susan Pike

Dr Susan Pike is an Assistant Professor in Geography Education in the School of Education in Trinity College Dublin.

Sandra Austin

Dr Sandra Austin is a Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Global Diversity, Sustainability and Intercultural Education at Marino Institute of Education, Dublin.

Richard Greenwood

Dr Richard Greenwood is a Senior Lecturer at Stranmillis University College in Belfast.

Karin Bacon

Dr Karin Bacon is a Lecturer in the area of Social, Environmental and Scientific Education and inquiry-based learning (IBL) at the Marino Institute of Education (MIE).

References

- Arnold, J., P. Burridge, M. Cacciattolo, C. Cara, T. Edwards, N. Hooley, and G. Neal. 2014. Researching the Signature Pedagogies of Praxis Teacher Education. Brisbane: AARE-NZARE.

- Bryant, J., and A. Bates. 2010. “The Power of Student Resistance in Action Research: Teacher Educators Respond to Classroom Challenges.” Educational Action Research 18 (3): 305–318. doi:10.1080/09650792.2010.499742.

- Byman, R., L. Krokfors, A. Toom, K. Maaranen, R. Jyrhämä, H. Kynäslahti, and P. Kansanen. 2009. “Educating Inquiry-Oriented Teachers: Students’ Attitudes and Experiences Towards Research-Based Teacher Education.” Educational Research and Evaluation 15 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1080/13803610802591808.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 1999. “Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher Learning in Communities.” Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 249–305. doi:10.3102/0091732X024001249.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. Lytle. 2009. Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2021. “Defining Teaching Quality Around the World.” European Journal of Teacher Education 44 (3): 295–308. doi:10.1080/02619768.2021.1919080.

- DeWitt, S. 2003. “Multicultural Democracy and Inquiry Pedagogy.” Intercultural Education 14 (3): 279–290. doi:10.1080/1467598032000117079.

- Dickson, B. 2011. “Beginning Teachers as Enquirers: M-Level Work in Initial Teacher Education.” European Journal of Teacher Education 34 (3): 259–276. doi:10.1080/02619768.2010.538676.

- Erlandson, D. A. 1993. Doing Naturalistic Inquiry: A Guide to Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Freire, P, and D P Macedo. 1996. “A dialogue: Culture, Language and Race.” In Breaking Free: The Transformative Power of Critical Pedagogy, edited by P. Leistyna, A. Woodrum, and S. A. Sherblom, 199–228. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Goodnough, K. 2011. “Examining the Long-Term Impact of Collaborative Action Research on Teacher Identity and Practice: The Perceptions of K–12 Teachers.” Educational Action Research 19 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1080/09650792.2011.547694.

- Greenwood, R., S. Austin, K. Bacon, and S. Pike. 2022. “Enquiry-Based Learning in the Primary Classroom: Student Teachers’ Perceptions.” Education 3–13 50 (3): 404–418. doi:10.1080/03004279.2020.1853788.

- Hulme, R., and D. Cracknell. 2009. “Learning Across Boundaries: Developing Trans-Professional Understanding Through Practitioner Enquiry.” In Connecting Inquiry and Professional Learning in Education: International Perspectives and Practical Solutions, edited by A. Campbell, and S. Groundwater-Smith. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hulse, B., and R. Hulme. 2012. “Engaging with Research Through Practitioner Enquiry: The Perceptions of Beginning Teachers on a Postgraduate Initial Teacher Education Programme.” Educational Action Research 20 (2): 313–329. doi:10.1080/09650792.2012.676310.

- Justice, C., W. Warry, and J. Rice. 2009. “Academic Skill Development – Inquiry Seminars Can Make a Difference: Evidence from a Quasi-Experimental Study.” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 3: 1. doi:10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030109.

- Kemmis, S. 2009. “Action Research as a Practice-Based Practice.” Educational Action Research 17 (3): 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Kroll, L. R. 2005. “Making Inquiry a Habit of Mind: Learning to Use Inquiry to Understand and Improve Practice.” Studying Teacher Education 1 (2): 179–193. doi:10.1080/17425960500288366.

- Levy, P., and R. Petrulis. 2012. “How Do First-Year University Students Experience Inquiry and Research, and What Are the Implications for the Practice of Inquiry-Based Learning?” Studies in Higher Education 37 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.499166.

- Lifelong Learning UK. 2009. “Northern Ireland Professional Standards for Teachers, Tutors and Trainers in the Lifelong Learning Sector.” Lifelong Learning UK. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/190/.

- Lotter, C., J. A. Yow, and T. T. Peters. 2014. “Building a Community of Practice Around Inquiry Instruction Through a Professional Development Program.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 12 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1007/s10763-012-9391-7.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 2010. Designing Qualitative Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Mitchell, D. 2020. Hyper-Socialised: How Teachers Enact the Geography Curriculum in Late Capitalism. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Roberts, M. 2010. “Geographical Enquiry.” Teaching Geography 35 (1): 6–9.

- Roberts, M. 2013. Geography Through Enquiry: Approaches to Teaching and Learning in the Secondary School. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Ross, J. A., J. Bradley Cousins, and T. Gadalla. 1996. “Within-Teacher Predictors of Teacher Efficacy.” Teaching and Teacher Education 12 (4): 385–400. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(95)00046-M.

- Short, K. 2009. “Inquiry as a Stance on Curriculum.” In Taking the PYP Forward, edited by S. Davidson, and S. Carber, 9–26. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Short, K., J. Harste, with C. Burke. 1995. “Creating Classrooms for Authors and Inquirers”. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Simmons, M, M Mcdermott, S E Eaton, B Brown, and M Jacobsen. 2021. “Reflection as Pedagogy in Action Research.” Educational Action Research 29: 245–258. doi:10.1080/09650792.2021.1886960.

- Swars, S. L., and C. M. Dooley. 2010. “Changes in Teaching Efficacy During a Professional Development School-Based Science Methods Course: Changes in Teaching Efficacy.” School Science and Mathematics 110 (4): 193–202. doi:10.1111/j.1949-8594.2010.00022.x.

- Teaching Council. 2020. Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education. Athlone: The Teaching Council. www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/teacher-education/initial-teacher-education/ceim-standards-for-initial-teacher-education.

- Van Katwijk, L., E. Jansen, and K. van Veen. 2021. “Development of an Inquiry Stance? Perceptions of Preservice Teachers and Teacher Educators Toward Preservice Teacher Inquiry in Dutch Primary Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 73 (3): 286–300. doi:10.1177/00224871211013750.

- Wirkala, C., and D. Kuhn. 2011. “Problem-Based Learning in K–12 Education: Is It Effective and How Does It Achieve Its Effects?” American Educational Research Journal 48 (5): 1157–1186. doi:10.3102/0002831211419491.