Abstract

Technology has the potential to enhance learning; however, generic technocentric strategies in schools have exacerbated barriers to technology integration in the classroom. Teachers are key to successful technology integration in schools. Factors such as subject culture and pedagogy will affect teachers’ willingness and ability to adopt technology in the classroom, yet subject-specific studies tend to focus on STEM subjects at the expense of the humanities. This mixed-methods study investigates technology use by teachers and pupils in the A-level history classroom in Northern Ireland, through the lens of Ertmer, P. 1999. “Addressing First- and Second-Order Barriers to Change: Strategies for Technology Integration.” Educational Technology Research and Development 47 (4): 47–61 classification of barriers. A number of impediments to effective technology use in the classroom were identified and strategies to minimise these barriers are recommended.

Introduction

Education technology has the potential to enhance learning in the classroom however a complex range of the factors affect teachers and their use technology in the classroom. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of the effective use of technology in education, yet many teachers struggled to adapt their lessons to digital delivery during school closures (Hebebci, Bertiz, and Alan Citation2020; Scully, Lehane, and Scully Citation2021; Winter et al. Citation2021). Deficiencies in motivation, self-efficacy (Kim and Ashbury Citation2020), IT skills (Niemi and Kousa Citation2020), knowledge of subject-specific technology strategies (Scully, Lehane, and Scully Citation2021) and access to technical resources (Hebebci, Bertiz, and Alan Citation2020) prevented teachers from successfully integrating technology into their teaching practice. However, those schools which addressed these barriers by providing support networks (Gandolfi and Kratcoski Citation2020; Lindsay and Whalley Citation2020), subject-specific technical professional development (Lindsay and Whalley Citation2020; Shin and Borup Citation2020), teaching resources (Gandolfi and Kratcoski Citation2020) and additional devices (Maher Citation2020; Vu, Meyer, and Taubenheim Citation2020) were able to support effective technology enhancing teaching and learning during Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al. Citation2020). With the potential of further disruption to classroom teaching, (Mejia Rodriguez et al. Citation2022) it is important to investigate barriers and to develop strategies to overcome these issues to achieve effective technology use in the classroom (Ertmer Citation1999).

Ertmer (Citation2015) defines technology integration as the meaningful use of technology to support or enhance learning. Studies have noted variations in technology integration between subject, key stage (Hammond, Reynolds, and Ingram Citation2011; Karaseva, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, and Siibak Citation2013; Zubković et al. Citation2017), school size (Francom Citation2020) and location (Backfisch et al. Citation2021; OECD Citation2016). In Northern Ireland, intermittent governance due to repeated suspensions of the Assembly (BBC Citation2020; McCormack Citation2023) has resulted in the absence of a national digital strategy and inequality of access to digital education in schools (NI Screen/RSM Consulting Citation2018; Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019). An uneven approach to research across school subjects, has placed a focus on technology use in STEM subjects at the expense of the humanities (Walsh Citation2017). The limited research into the use of technology in history suggests that teachers and pupils are conservative in their use of ICT (Haydn and Ribben Citation2017; Jasik et al. Citation2016) and should increase their use of technology in the classroom (Walsh Citation2017). The purpose of this study is to investigate technology integration in A-level history classrooms in Northern Ireland and to identify any barriers that would prevent effective technology use during lessons. This study uses Ertmer’s (Citation1999) classification of first and second-order barriers as a theoretical underpinning.

Literature review

In order to anticipate potential barriers in the contemporary history classroom in Northern Ireland, Ertmer’s (Citation1999) classification of barriers is used to structure a review of studies of technology integration in schools and technology use in the history classroom, and in Northern Ireland. The key findings from this review are used to inform the research questions for this investigation.

Teachers are the key to the process of technology integration in the classroom (Ertmer Citation1999; Hew and Brush Citation2007; Player-Koro Citation2012). A complex range of the factors affect teachers and their decision to use technology in the classroom; Ertmer (Citation1999) classified those with a negative influence on technology integration as barriers. First-order barriers are external and relate to the availability of resources such as hardware and software, time, training, and support. Second-order barriers are internal to teachers and concern their attitudes and beliefs about technology, classroom practice and willingness to change (Ertmer Citation1999). These barriers are interrelated, in flux (Ertmer Citation1999), and affected by the contextual factors of institution, assessment, and subject culture (Hew and Brush Citation2007).

First-order barriers

As technology access in schools has normalised, the focus of much research has shifted to second-order barriers (Ertmer et al. Citation2012). However, first-order barriers have not been wholly eliminated as illustrated by the studies of Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al. Citation2020) conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. Hebebci, Bertiz, and Alan Citation2020; Scully, Lehane, and Scully Citation2021; Winter et al. Citation2021).

Poor quality, lack of access, and inadequate maintenance of equipment are considered to be barriers to technology use (Hennessy, Ruthven, and Brindley Citation2005). Teachers need access to robust and up-to-date hardware and software in order to integrate technology into their classroom practice (Lawrence and Tar Citation2018; Mejia Rodriguez et al. Citation2022). However, during ERT a lack of available technical equipment and robust internet connections prevented teachers in Northern Ireland (ETI Citation2020), Republic of Ireland (Scully, Lehane, and Scully Citation2021; Winter et al. Citation2021) and internationally (Hebebci, Bertiz, and Alan Citation2020) from successfully migrating their teaching practice online. Educational organisations that anticipated the potential barrier of equipment shortages and limited internet connections were able to supply additional devices to students to facilitate their migration to learning online during lockdown (Maher Citation2020; Vu, Meyer, and Taubenheim Citation2020).

The Education Training Inspectorate (ETI) highlighted the issue of digital disadvantage in their 2021 report, noting that three-fifths of schools identified restricted access to IT at home as a barrier to remote learning (ETI Citation2021). In Northern Ireland, prior to 2022, C2K provided primary and post-primary schools with a standardised provision of whiteboards, computer suites, PCs, laptops, a managed learning environment and software maintained by a centralised support team (C2K Citation2016). A review of post-primary schools is not available; however, a 2019 survey of Northern Ireland primary schools suggests a variation in the availability of equipment in schools, with over a third of teachers indicating they did not have access to sufficient technical resources (Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019).

Regardless of the specification of the technical infrastructure, teachers need sufficient subject-specific training to integrate the available technology into their lessons (Francom Citation2020; Selwyn Citation2017; The World Bank, UNESCO and UNICEF Citation2021). Collaborative, teacher-driven forms of professional development such as communities of practice and professional learning communities enable teachers to develop their skills and improve their technical self-efficacy (Durff and Carter Citation2019). Insufficient training will act as a barrier (Lawrence and Tar Citation2018); a factor that prevented some teachers from implementing effective online teaching during ERT (Winter et al. Citation2021). Those schools that addressed this potential barrier with support networks and subject-specific technical professional development (Gandolfi and Kratcoski Citation2020; Lindsay and Whalley Citation2020; Shin and Borup Citation2020) were able to rapidly upskill their staff and facilitate effective remote teaching.

According to the 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), 18% of teachers identified a need for ICT training (OECD Citation2020). In Northern Ireland, there are no compulsory digital skills attainment levels, nor accreditation for teachers and training is funded from internal school budgets, which can limit provision (NI Screen/RSM Consulting Citation2018). The survey of Northern Ireland primary school teachers identified gaps in ICT skills provision, with a third of respondents indicating that they did not have the opportunity to develop their ICT skills (Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019).

A lack of time deters greater technology use as it limits opportunities for teachers to develop their skills, to locate and try out new resources, and to plan ways of integrating technology into lessons (Francom Citation2020; Lawrence and Tar Citation2018; Tondeur et al. Citation2017). School leaders who schedule time for their teachers to take part in training, share their technical practice and plan the use of technical resources in their lessons facilitate greater technology integration in the classroom (Durff and Carter Citation2019). Insufficient time was found to limit opportunities for primary school teachers in Northern Ireland to develop their skills and to locate and try out new resources (Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019). A large expenditure of time is needed to devise effective digital history resources (Tribukait Citation2020); however, few history teachers considered the benefits of new technologies equivalent to the investment (Walsh Citation2017).

Second-order internal barriers

Even if resource-based factors are resolved, second-order barriers, those that are intrinsic and relate to teachers’ knowledge and beliefs, may limit technology usage (Ertmer Citation1999; Player-Koro Citation2012). Specific technical knowledge, which is used for administrative and communication tasks is associated with the use of technology as a delivery tool (Hew and Brush Citation2007). Whereas technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) which aligns technology affordances with teachers’ discipline, pedagogical approach and educational circumstance will motivate meaningful technology integration (Lawless Citation2016; Makki et al. Citation2018). Limited technical knowledge can act as a barrier as it can result in low levels of confidence (self-efficacy), causing teachers to avoid the use of technology (Lawrence and Tar Citation2018; Player-Koro Citation2012). TPACK increases teachers’ technical self-efficacy, their perceived ease of use and usefulness of technology, which positively impacts on their intention to use technology in the classroom (Joo, Park, and Lim Citation2018). The absence of technical self-efficacy was a potential barrier identified by history teachers (Jasik et al. Citation2016), who were found to have lower confidence levels than their STEM counterparts (Zubkovic et al. Citation2017). Inadequate knowledge of subject-specific technology strategies (Scully, Lehane, and Scully Citation2021) and technical self-efficacy (Kim and Ashbury Citation2020; König, Jäger-Biela, and Glutsch Citation2020) were two factors that affected teachers’ successful migration to online teaching during COVID.

Pedagogical beliefs concern how a subject is taught and the role of the teacher and students in the classroom (Tondeur et al. Citation2017). Teachers will implement technology according to their educational approach (Francom Citation2020; Heitink et al. Citation2016; Tondeur et al. Citation2017). Those teachers with a preference for traditional teaching are more likely to demonstrate low levels of technology integration, whereas teachers with constructivist, student-centred beliefs will have the most transformative digital teaching practice (Ertmer et al. Citation2012).

Teachers’ technology beliefs concern their preference for technology and their perception of its educational value (Hew and Brush Citation2007). Teachers who recognise the pedagogical value of a technology, will overcome resource-based barriers to facilitate its use (Ertmer et al. Citation2012; Vongkulluksn, Xie, and Bowman Citation2018). However, if teachers do not consider the technology to be conducive to learning outcomes it will not be integrated into regular practice (Backfisch et al. Citation2021; Heitink et al. Citation2016; Lawrence and Tar Citation2018). History educators are reluctant to adopt technologies of perceived limited educational relevance (Haydn Citation2013; Haydn and Ribben Citation2017; Walsh Citation2017) particularly those that are not aligned to curricular learning objectives e.g. chronological thinking skills (Jasik et al. Citation2016). However, a number of studies have demonstrated the effective use of technology in post-primary history, in particular, the enquiry-based use of digital media to develop curricular historical knowledge and skills. The internet provides teachers with access to a range of digital historical sources that can engage, and challenge students; encouraging debate, analysis, and the development of historical thinking skills (Haydn and Ribben Citation2017; Tribukait Citation2020; Walsh Citation2017).

However, teachers will conform to the norms of the subject and reflect the classroom practices and attitudes towards technology of their peers and senior management (Hennessy, Ruthven, and Brindley Citation2005; Karaseva, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, and Siibak Citation2013; Zubković et al. Citation2017). Constrained by the curriculum or exam targets, teachers may be reluctant to incorporate new forms of technologies into their practice preferring to adopt traditional (transmission) forms of teaching to cover the syllabus more efficiently (Ertmer et al. Citation2012; Tondeur et al. Citation2017). A study of European history curricula noted that that national curricula do not stipulate the use of digital technologies concluding that this had a negative impact on technology integration in the classroom (Tribukait Citation2020). In addition, students’ negative attitudes, lack of confidence and poor ICT skills will minimise their use of technology and negatively impact on teachers’ inclination to use technology in the classroom (Hennessy, Ruthven, and Brindley Citation2005). Inadequate students’ ICT skills was an issue highlighted by history teachers (Jasik et al. Citation2016) and by maths teachers (Mailizar, Abdulsalam, and Suci Citation2020) and educators in Northern Ireland (ETI Citation2020) during remote learning.

This review sought to investigate the potential presence of barriers to technology integration in the contemporary post-primary history classroom in Northern Ireland. The literature suggests that meaningful technology use continues to be hampered by Ertmer’s (Citation1999) first and second order barriers. The overarching research question was identified as ‘What are the barriers to technology integration in A-level history teaching in Northern Ireland?’. Recurrent categories of barriers identified in the literature were then included in the research aims:

Research aim 1: Determine teachers’ and pupils’ access to, and regularity of use of technology resources in the A-level history classroom

Research aim 2: Gauge history teachers’ technical knowledge and training in the use of technology in the classroom

Research aim 3: Characterise A-level history teachers’ classroom practice and pedagogical beliefs

Research aim 4: Identify A-level history teachers’ and pupils’ technology beliefs and attitudes towards the use of technology in the classroom

Materials and methods

A mixed-methods methodology was adopted for the study with a complementarity, concurrent research design employed to investigate the four aspects of the A-level history classroom context in Northern Ireland (Greene, Caracelli, and Graham Citation1989; Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013). Three methods of data collection were implemented: an online questionnaire, a standardised interview, and a semi-structured focus group. The initial survey of A-level history teachers aimed to develop a broad overview of the educational context and classroom practice. Teachers’ interviews and pupils’ focus groups were conducted to gather more in-depth descriptions of classroom activities and attitudes (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). The first method, an online questionnaire, targeted the population of 100–150 A-level history teachers in 130 post-primary schools in Northern Ireland (DOE Citation2019). The online questionnaire included dichotomous, multiple-choice, and Likert scale questions to probe teachers’ experience of teaching A-level history and access and use of technology. Those teachers responding to the questionnaire were invited to take part in further research. Of those who expressed interest, a purposeful sample of six teachers from schools that were representative of the variety of those offering the CCEA GCE History in Northern were selected to participate in standardised interviews and focus groups. These history teachers were selected for their heterogeneity of gender, teaching experience (ranging between 5 and 35 years) and type of school in order to achieve maximum variation across the sample (Patton Citation2002). The schools being single-sex or mixed, controlled, voluntary grammar or integrated establishments located in each of the different district councils in Northern Ireland. An hour-long interview was conducted with a teacher from each of these six sample schools, followed by a 35-minute focus group with between five and ten of the teacher’s A-level history pupils. All focus-group students were studying the A2 2 module of the CCEA A-level curriculum, four of the six groups were mixed-sex, one was all male, the other all-female. Interview schedules with questions regarding classroom practice and attitudes and use of technology were used to structure these sessions (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007).

The data from each method were analysed independently, then, integrated during interpretation and reporting (Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013). Descriptive statistical calculations were performed on the quantitative data and tables, bar charts and pie charts were created to identify patterns and themes (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2007; Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). The data from history teachers’ structured interviews and pupils’ focus groups were subjected to qualitative content analysis; a method suitable for parallel mixed analysis (Tashakkori and Teddlie Citation1998) with the quantitative data from the online survey. The qualitative data was subjected to three stage content analysis process: data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing and verification (Miles and Huberman Citation1984). Due to the heterogeneity of the qualitative sample, themes that appeared in two of more schools after coding were considered indicative of a pattern. Tabular and graphical representations were used to examine trends and patterns within and across the datasets (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). Visual representations of the qualitative and quantitative procedures were merged through joint displays during interpretation and then integrated by research aim during the reporting of the findings (Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013).

Results

Access to and use of technology resources in the A-level history classroom

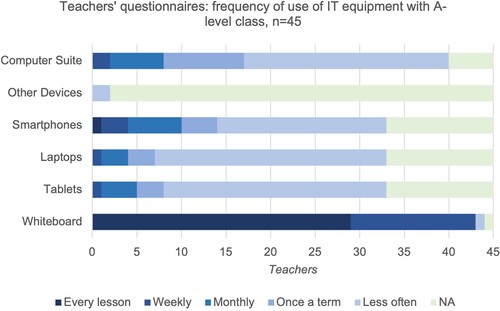

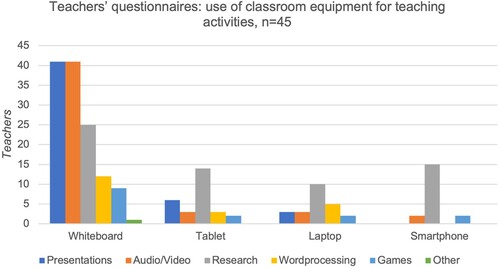

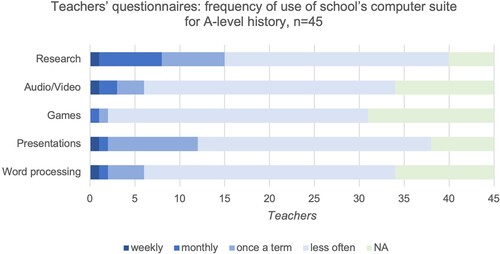

Results from the survey presented in and and from teachers’ interviews demonstrate that most A-level history teachers used a whiteboard and PC in their classroom whereas levels of student technology use were found to be much lower. According to and , nearly all the survey teachers (44/45) have access to a whiteboard in their classroom, which they used at least weekly (43/45), with 29 employing it daily. Most survey teachers (41/45) utilised their whiteboard to show slideshow presentations and play audio/video to the class. All interview teachers used their whiteboard to show video (6/6) and half to show PowerPoint presentations (3/6), their choice of resource was determined by the subject of the lesson:

… it just depends on the topic. So sometimes I’ll give them an overview with a PowerPoint and then they will have to go and do their own reading and making notes and … , to consolidate a topic at the end, … I will show them the programme. (Teacher, school C)

shows that only one survey teacher agreed to employing tablets on a weekly basis with their A-level class, four more teachers used them monthly. Only one of the interview teachers (in the school with mandatory tablet ownership) agreed to using tablets with his A-level pupils. Survey teachers, as illustrated in , were found to be more likely to employ smartphones than tablets with their A-level class. A third of teachers encouraged their pupils to use devices – 15/45 mobiles and 14/45 tablets – for self-directed research (). When mobile devices were employed, their use is regulated and restricted to certain year groups:

Their phones can only be used in very closely monitored circumstances within classes and it’s only sixth form and it’s only in certain subjects and it’s only when they have signed a personal device policy. (Teacher, school F)

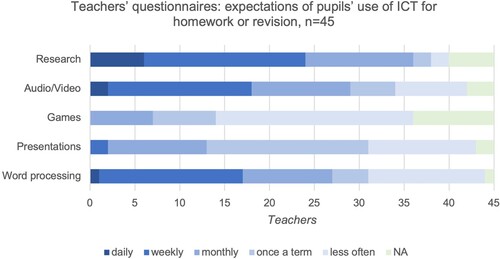

demonstrates that rates of student technology use are expected to be higher outside the classroom. Two-thirds of surveyed teachers (30/45) expected the weekly utilisation of technology by their students, a smaller fraction (6/45) expected daily usage for homework. Student research (24/45), audio/video consumption (18/45) and word processing (17/45) were the most frequently set tasks. These findings aligned with comments from half of the interviewed teachers (3/6), who stated their homework required a connected digital device.

A-level history teachers’ technical knowledge and training

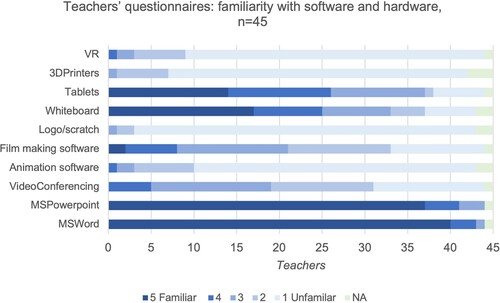

Findings indicated that the majority of teachers were familiar with standard software and hardware and were satisfied with their level of technical Continuing Professional Development (CPD). According to the survey responses presented in , over three-quarters of teachers (36/45) received ICT-related CPD during the past five years, the majority of whom received instruction in the use of general software such as MS Office (22/45) and Google Education (19/45). As shown in , most survey teachers declared themselves familiar with this type of software e.g. MS Word (40/45) and MS PowerPoint (37/45), a smaller number considered themselves familiar with filmmaking (8/45) and none were knowledgeable of coding or animation. Just over half of the survey teachers (26/45) claimed to be familiar/very familiar with tablets, and slightly fewer teachers (25/45) claimed to be familiar with whiteboard technology. One interviewee was found to possess more advanced skills and discussed using interactive apps on tablets. Findings suggest that history teachers were satisfied with their level of technical knowledge as only a quarter of survey teachers (11/45) desired further CPD, few survey teachers considered their technical skills to be a barrier to ICT use (see 'A-level history teachers’ and pupils’ technology beliefs' section) and none of the teacher interviewees discussed a need for additional training.

A-level history teachers’ classroom practice and pedagogical beliefs

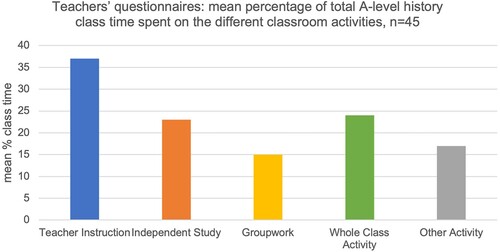

The findings from the survey () and interviews suggest that teacher instruction was the dominant teaching activity in the classroom, followed by whole class activity and independent pupil study. demonstrates that a mean percentage of 37% of class time was spent in teacher instruction. This corresponded with interview findings, which indicate that all teachers engage in teacher instruction to ensure that the whole syllabus is covered during class time:

It is mostly teacher-led at the moment … It would be great to have them go on and research things … and read it themselves … [or] like the podcast, that if you thought they would go and listen to it, but you couldn’t guarantee that they would. (Teacher, school C)

Figure 7. Teachers’ questionnaires: mean percentage of total A-level history class time spent on the different classroom activities.

… so, we quite often get into debates … that gets them really thinking … , we have such rich debates, it’s very good how they are engaged. (Teacher, school B)

Whenever, the pupils are … watching one of the [online] lectures or listening to the podcast, they are not being passive, they are encouraged to take notes as they do so. So, it’s just really to ensure there is a variety of ways in which that information is being relayed. (Teacher, school F)

When asked to describe their experience of teaching A2 2 module, all teacher interviewees identified a lack of time as a major difficulty and attributed its scarcity to the characteristics and circumstances of the CCEA specification:

The problem is … they’ve increased the paper from two hours to two and a half. It has made it even more content heavy. Thus, cutting down the time to do that [watch videos] … and that’s what I find frustrating. (Teacher, school A)

Push all this information at them and they are sitting there bored to tears, … you have to cover the content there is no other way around it, it’s an A-level … (Teacher, school D)

A-level history teachers’ and pupils’ technology beliefs

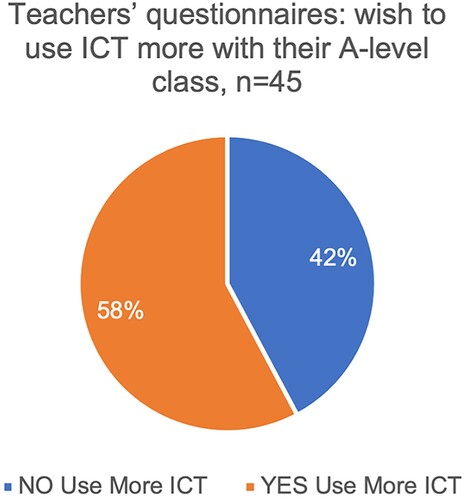

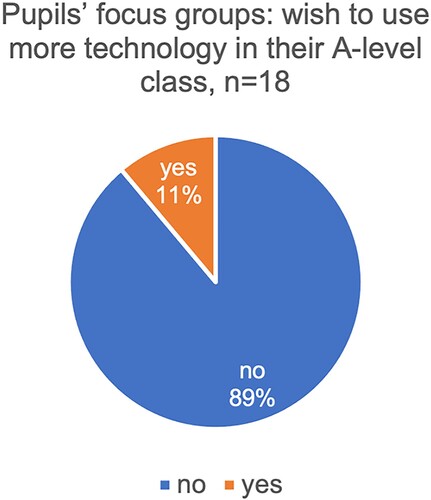

Findings indicated that teachers were more interested than pupils in increasing their use of technology in the classroom ( and 9). Over half of survey teachers (58%) were keen to include more ICT in the classroom, whereas only a tenth of pupils (11%) desired an increase in the educational use of technology ( and ).

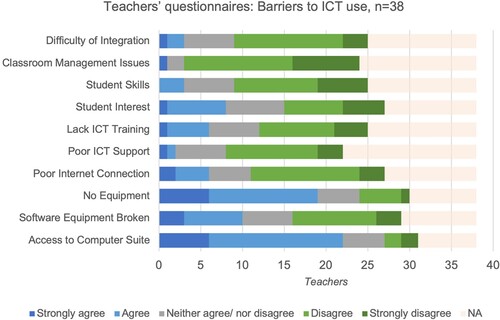

presents survey teachers’ perceived barriers to technology use in the A-level classroom. When asked to select barriers to technology usage in their A-level class, over half of surveyed teachers (22/38) identified the lack of access to a computer suite. Half of the survey teachers (19/38) mentioned a lack of equipment and a quarter of teachers (10/38) cited broken software or equipment wheras only six teachers considered their technical skills to be a barrier to ICT use. However, when discussing barriers during the interviews, only two teachers mentioned access to technical facilities, whereas five cited time, four mentioned pupils’ skills or attitudes, and three highlighted a lack of relevance to the A-level specification. Two teachers believed that a lack of time prevented them from facilitating student use of technology and two interviewees felt it prevented them from incorporating more audio-visual or interactive content into lessons:

They like the documentaries, and they would watch extracts from some, … and … the Trinity talks [Ireland in Rebellion video lectures]. … That’s good in terms of visualization. But again, the basic problem is time (Teacher, school A)

I don’t think they rate technology enough. I think if pupils think they are on technology or if I took them to a computer suite and ask them to do a bit of research that it’s not real learning for them, … they think that was a waste … (Teacher, school B)

I think with essays and stuff or writing notes, it goes into your head better (Pupil, school E)

I would love to use it, they would love to use it, but I don’t feel it would advance us through the course a lot and that’s my bottom line. (Teacher, school B)

I think you’re better learning off paper because actually physically writing it as opposed to typing it. Your exam is writing, you’re developing that skillset, the muscle memory of writing whereas with the tablet I don’t think you would get that. (Pupil school, B)

The visual and engaging nature of technology was praised by most teachers and pupils during the interviews and focus groups. Five teachers used their whiteboards to illustrate historical characters, events, and concepts with video and primary sources:

… the series on the Third Home Rule Crisis. … . That’s good in terms of visualization. … they love them, they can really relate to them, because … when you are describing things like Carson reviewing the UVF, you can see it. (Teacher, school A)

… it, makes it easier to understand it like. Helps you visualize it in your head, it’s just not the same when it is on a piece of paper … . (Pupil, school D)

Students … enjoy engaging with audio-visual material and certainly by the time they get to year 14, I would be encouraging them to engage with a range of audio-visual material … (Teacher, school F)

Discussion

Research aim 1: Determine teachers’ and pupils’ access to, and regularity of use of technology resources in the A-level history classroom

Consistent with previous studies (Haydn and Ribben Citation2017; Jasik et al. Citation2016; Walsh Citation2017) technology use in the Northern Ireland A-level history classroom was found to be moderate with teachers identified as the primary technology users. Nearly all A-level history teachers had access to a whiteboard, which they used on a daily or weekly basis to display PowerPoint presentations or play media, suggesting that history teachers avoid the more advanced (interactive) functionality of whiteboards in favour of presenting information (Haydn and Ribben Citation2017; Walsh Citation2017). It was found that the majority of pupils were not provided with personal devices and that only one school had regular access to tablets in history classes. This level of access was reflected in pupils’ use of devices, which was limited to the occasional use of mobile phones and tablets for personal research. Visits to the computer suite for history were rare and limited use was made of the facility for general research or compiling presentations. However, teachers expected greater use of technology by pupils outside the classroom, with two-thirds expecting the use of ICT for weekly study/homework.

Ertmer (Citation1999) identified time and access to technical resources as first-order barriers to technology implementation in schools. A-level history teachers cited their limited access to adequate technical facilities as a barrier, ranging from limited access to the computer suite, to a lack of equipment or broken hardware and software. This reflects the findings of ETI’s Citation2020 and Citation2021 reviews of ERT in Northern Ireland which noted that a lack of available technical equipment and robust internet connections restricted teachers’ online delivery and students’ digital learning (ETI Citation2020, Citation2021). In the study, teachers cited a lack of time as a deterrent to greater technology use in the A-level history classroom. All teachers felt obligated to cover the extensive content knowledge and exam preparation of the CCEA specification during timetabled lessons. Consequently, teachers felt they had insufficient time to dedicate to locating, devising and implementing additional digital history resources, corresponding with the findings of Tribukait (Citation2020) and Walsh (Citation2017).

Research aim 2: Gauge history teachers’ technical knowledge and training in the use of technology in the classroom

Insufficient training and limited technical knowledge can act as a barrier as it can result in low levels of confidence (self-efficacy), causing teachers to avoid the use of technology (Ertmer Citation1999; Lawrence and Tar Citation2018). In Northern Ireland, there are no compulsory technical training attainment levels for post-primary teachers, nor certification for prior training (NI Screen/RSM Consulting Citation2018). Most surveyed history teachers had received general ICT-related training during the past five years and believed they had received sufficient ICT CPD for their teaching needs. This is in contrast to the findings of TALIS (OECD Citation2020) and the Northern Ireland primary school digital survey (Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019) that suggests there are gaps in ICT provision for teachers. The history teachers appear to be well-versed in standard technology, professing familiarity with Microsoft Office. Fewer respondents had received advanced/specialist technical CPD, and this was reflected in their technology familiarity rating, which suggests they possess specific technology knowledge (Hew and Brush Citation2007). Typical teachers’ technical training programmes aim to develop general software skills (Ertmer et al. Citation2012), however authors agree that subject-specific training is required for effective technology integration in lessons (Francom Citation2020; Selwyn Citation2017; The World Bank, UNESCO and UNICEF Citation2021). The Education and Training Inspectorate noted that nearly all schools provided in-house technical CPD to staff during ERT and that their staff had become more digitally aware (ETI Citation2021). Communities of practice and subject-specialist teacher networks proved particularly effective for sharing knowledge and developing digital practice amongst teachers prior to and during remote teaching conditions (Durff and Carter Citation2019; Gandolfi and Kratcoski Citation2020; Lindsay and Whalley Citation2020).

Research aim 3: Characterise A-level history teachers’ classroom practice and pedagogical beliefs

Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs concern how a subject should be taught and the role of teacher and learner in the classroom (Ertmer Citation1999; Hew and Brush Citation2007); teachers will align their technology use to their pedagogical approach (Francom Citation2020; Heitink et al. Citation2016; Tondeur et al. Citation2017). The data from the teachers’ interviews and questionnaires indicated that teacher instruction was the dominant A-level history classroom activity, followed by whole-class activity such as discussion. Independent pupil study was also popular; however, this was teacher-led and included activities such as the reading of teacher-compiled booklets, note-taking, and written assessments. There were lower levels of pupil-led activities such as groupwork and self-directed research, which were largely confined to outside the classroom.

The data indicated that despite the constructivist foundations of the history curriculum (HA Citation2020), the behaviourist nature of summative assessment deterred A-level history teachers from engaging in constructivist practices such as pupil-led learning, reflecting the findings of Husbands, Kitson, and Pendry (Citation2003). Summative assessment is used as a tool of accountability in schools, which places pressure on history teachers to ensure their pupils achieve high grades in their A-levels (Husbands Citation1996). In the study, A-level history teachers were conscious of the need to cover extensive content knowledge, in addition to exam preparation, which left them feeling under time pressure. This pressure motivated them to use traditional modes of instruction such as lecturing in order to efficiently cover the syllabus; their technology use of PowerPoint presentations and playing video reflected this pedagogical approach (Francom Citation2020; Heitink et al. Citation2016; Tondeur et al. Citation2017). These findings are consistent with previous studies, that suggest that teachers favouring traditional teaching practices who possess specific technology knowledge will engage in the teacher-centric use of technology (Hew and Brush Citation2007; Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich Citation2010, Citation2013).

Research aim 4: Identify A-level history teachers’ and pupils’ technology beliefs and attitudes towards the use of technology in the classroom

Teachers’ technology beliefs – those that relate to the perceived educational value of technology and preference for its use – affect the implementation of ICT in the classroom (Ertmer Citation1999; Hew and Brush Citation2007). Findings revealed that A-level history teachers and pupils did identify the benefits of using technology in the classroom for the purposes of illustration, visualisation, and engagement. Although over half of the history teachers declared a desire to use more technology, time and educational value concerns outweighed the perceived benefits of pupils’ technology use. Teachers felt that an increase in the use of technology would not advance the class through the curriculum, suggesting that further integration of technology would be unlikely (Hennessy, Ruthven, and Brindley Citation2005; Jasik et al. Citation2016). This concern was echoed by pupils who believed that technology use was not relevant to the A-level history specification. They cited a preference for traditional modes of teaching and learning such as lecturing and making notes as these were considered more compatible with the study and assessment of the A2 2 history module. Benini and Murray’s (Citation2014) noted that pupils consider technology to be an engaging but non-essential aspect of learning. Pupils’ mistrust of technology can impede teachers’ technology use (Hennessy, Ruthven, and Brindley Citation2005) corresponding with the identification of pupils’ skills and attitudes as a potential barrier by A-level history teachers. These findings reflect Walsh’s (Citation2017) conclusions that the nature of external assessment prevents history teachers and pupils from recognising the educational value of technology in the classroom.

Limitations

The reported gaps in access to digital education in Northern Ireland (Galnouli and Clarke Citation2019) indicate the need for research into technology integration in schools, however, there are few available studies on technology use in post-primary schools in Northern Ireland, and in the history classroom. Therefore, this investigation was designed to be exploratory, to shed light on history teacher’s use of technology and to identify potential barriers to technology integration. The findings from the study should be used to indicate potential issues and provide lines of inquiry for researchers investigating technology use in schools.

Additional research is particularly recommended as a result of changes that have occurred since data collection, namely Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) and changes in technology infrastructure. The Education Authority NI (EANI) introduced EdiS to replace C2K system in schools EANI (Citation2022), therefore it is recommended that further investigation into technical infrastructure in post-primary schools is conducted. The impact of ERT on teachers’ technical training and knowledge and perceived value of technology in the classroom are additional topics of investigation. In addition, the small sample size and use of purposive sampling limits the generalisability of the findings from the teacher’s interviews. However, this method did produce rich data and is recommended that additional interviews with a larger sample size be conducted.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study used Ertmer’s (Citation1999) classification of barriers as a lens through which to investigate technology use in A-level history classrooms in Northern Ireland. Findings indicate that meaningful technology use in this educational context continues to be hampered by a number of impediments. Technology use in the A-level history classroom was found to be moderate with first and second level barriers affecting further technology integration. Access to adequate technology, insufficient time, teachers’ technological and pedagogical beliefs and pupils’ attitudes and skills were identified as barriers to further technology integration. The process and pressures associated with assessment-level history curricula contributed to some of these factors.

The history teachers identified a lack of equipment, poor access to the computer suite, and a limited number of student devices as barriers to greater technology use. This reflects the findings of the ETI study which identified the issue of student access to technical equipment during ERT (ETI Citation2020). As indicated in the previous section, changes in technical infrastructure caused by a change in supplier and ERT indicate the need for additional research into the topic of technology access in post-primary history classrooms. With many history teachers’ expecting students’ technology use at home, student domestic access to technology also needs further investigation to prevent digital disadvantage (ETI Citation2021).

The extensive A-level curriculum shaped teachers’ pedagogical and technological beliefs and contributed to their perception of time as a barrier. History teachers were conscious of the need to cover extensive and complex content knowledge in addition to historical skills during their timetabled lessons. Teachers employed a transmission model of teaching and used technology to complement this approach. Pupils and teachers were reluctant to incorporate additional forms of technology, concerned it would not contribute to their coverage of the curriculum (Haydn Citation2013). Tribukait (Citation2020) suggests using the curriculum to encourage greater use of technology in the history classroom. The current history specification, which is assessed through a hand-written exam, does not simulate technology use in the class. A less expansive curriculum which references student-centred activities such as the enquiry-based use of digital historical sources would facilitate greater technology integration in the classroom (Walsh Citation2017). A less extensive A-level specification would allow teachers more time to engage in subject-specific ICT training, to try out new technologies, and to plan their integration into lessons.

A change in the curriculum should be complemented by a framework of accredited subject-specific technology professional development and the development of the communities of practice established during ERT. Technical training, resources and techniques designed specifically for A-level history teachers would encourage a more positive attitude and awareness of effective uses of technology and motivate meaningful technology integration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ellen Bell

Dr Ellen Bell holds a PhD in Education and has 17 years’ industry experience developing innovative digital learning resources. She teaches on the BSc Interactive Media and BA, MA Journalism courses at Ulster University. Her research interests include education technology in schools, usability, location-based learning and digital archives.

David Barr

Professor David Barr is Head of the School of Education and Professor of Technology-Enhanced Learning. He is also a leading expert in computer-assisted language learning, serving as associate editor for two leading international journals in the area, and is a member of the WorldCALL steering committee.

References

- Backfisch, Iris, Andreas Lachner, Kathleen Stürmer, and Katharina Scheiter. 2021. “Variability of Teachers’ Technology Integration in the Classroom: A Matter of Utility!.” Computers & Education 166: 104159. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104159.

- BBC. 2020. “Stormont Deal: Parties Return to Assembly After Agreement.” BBC News, January 11. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-51071827.

- Benini, S., and L. Murray. 2014. “Challenging Prensky’s Characterisation of Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants in a Real-World Classroom Setting.” In Chap. 3 in Digital Literacies in Foreign and Second Language Education, edited by J. P. Guikema, and L. Williams, CALICO Monograph Series, 12, 69–85. San Marcos, TX: CALICO.

- C2K. 2016. “Information Sheet ENO39: Managing Internet Filtering.” http://www.c2kexchange.net.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education. 6th ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., and V. L. Plano Clark. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- DOE. 2019. “Schools and Pupils in Northern Ireland 1991/92–2018/19.” https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/education/enrolment%20time%20series%201819_1.XLSX.

- Durff, Lisa, and Maryfriend Carter. 2019. “Overcoming Second-Order Barriers to Technology Integration in K–5 Schools.” Journal of Educational Research and Practice 9 (1): 17. doi:10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.18.

- EANI. 2022. “Education Information Solutions Programme (EdIS).” https://www.eani.org.uk/services/education-information-solutions-programme-edis.

- The Education and Training Inspectorate. 2020. “Post-primary. Remote and Blended Learning: Curricular Challenges and Approaches.” https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/post-primary-curricular-challenges-and-approaches-taken_4.pdf.

- The Education and Training Inspectorate. 2021. “Thematic Report on Post-Primary Schools’ Delivery, Monitoring and Evaluation of Effective Remote Learning.” https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/post-primary-thematic-report-on-remote-learning_0.pdf.

- Ertmer, P. 1999. “Addressing First- and Second-Order Barriers to Change: Strategies for Technology Integration.” Educational Technology Research and Development 47 (4): 47–61. doi:10.1007/BF02299597.

- Ertmer, P. 2015. “Technology Integration in Spector.” In Sage Encyclopedia of Educational Technology, edited by J. Michael Spector, and Youqun Ren, 748–751. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ertmer, P. A., and A. T. Ottenbreit-Leftwich. 2010. “Teacher Technology Change.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 42 (3): 255–284. doi:10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551.

- Ertmer, P. A., and A. T. Ottenbreit-Leftwich. 2013. “Removing Obstacles to the Pedagogical Changes Required by Jonassen's Vision of Authentic Technology-Enabled Learning.” Computers & Education 64: 175–182. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.008.

- Ertmer, P. A., A. T. Ottenbreit-Leftwich, O. Sadik, E. Sendurur, and P. Sendurur. 2012. “Teacher Beliefs and Technology Integration Practices: A Critical Relationship.” Computers & Education 59 (2): 423–435. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001.

- Fetters, M. D., L. A. Curry, and J. W. Creswell. 2013. “Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices.” Health Services Research 48 (6pt2): 2134–2156. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12117.

- Francom, Gregory M. 2020. “Barriers to Technology Integration: A Time-Series Survey Study.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 52 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/15391523.2019.1679055.

- Galnouli, D., and L. Clarke. 2019. “Study into the Development of Digital Education in Primary Schools in Northern Ireland.” https://www.northernirelandscreen.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Digiskills-Full-Report.pdf.

- Gandolfi, E., and A. Kratcoski. 2020. “Coping During Covid-19: Building a Community of Practice (CoP) for Technology Integration and Educational Reform in a Time of Crisis.” In Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, 169–173.

- Greene, J. C., V. J. Caracelli, and W. F. Graham. 1989. “Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11 (3): 255–274. doi:10.3102/01623737011003255.

- Hammond, M., L. Reynolds, and J. Ingram. 2011. “How and why do Student Teachers use ICT?” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27 (3): 191–203. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00389.x.

- Haydn, T. 2013. “What Does It Mean ‘To Be Good at ICT’ as a History Teacher?” In Using New Technologies to Enhance Teaching and Learning in History, edited by T. Haydn, 6–28. London: Routledge.

- Haydn, T., and K. Ribben. 2017. “New Technologies in History Education.” In Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, edited by M. Carretero, S. Berger, and M. Grever, 735–753. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hebebci, M. T., Y. Bertiz, and S. Alan. 2020. “Investigation of Views of Students and Teachers on Distance Education Practices During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” International Journal of Technology in Education and Science 4 (4): 267–282. doi:10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.113.

- Heitink, M., J. Voogt, L. Verplanken, J. van Braak, and P. Fisser. 2016. “Teachers’ Professional Reasoning About Their Pedagogical use of Technology.” Computers & Education 101: 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.05.009.

- Hennessy, S., K. Ruthven, and S. Brindley. 2005. “Teacher Perspectives on Integrating ICT Into Subject Teaching: Commitment, Constraints, Caution, and Change.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 37 (2): 155–192. doi:10.1080/0022027032000276961.

- Hew, K. F., and T. Brush. 2007. “Integrating Technology into K-12 Teaching and Learning: Current Knowledge Gaps and Recommendations for Future Research.” Educational Technology Research and Development 55 (3): 223–252. doi:10.1007/s11423-006-9022-5.

- Historical Association. 2020. “Disciplinary Concepts.” Accessed 3 September 2020. https://www.history.org.uk/secondary/categories/pp-disciplinary-concepts.

- Hodges, Charles B., Stephanie Moore, Barbara B. Lockee, Torrey Trust, and Mark Aaron Bond. 2020. “The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning.” https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning.

- Husbands, C. 1996. What is History Teaching? Language, Ideas, and Meaning in Learning About the Past. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Husbands, C., A. Kitson, and A. Pendry. 2003. Understanding History Teaching, Teaching and Learning About the Past in Secondary Schools. Maidenhead.: Open University Press.

- Jasik, K., J. Lorenc, K. Mrozowski, J. Staniszewski, and A. Walczak. 2016. Innovating History Education for All. Needs Assessment. Warsaw: Educational Research Institute.

- Joo, Young Ju, Sunyoung Park, and Eugene Lim. 2018. “Factors Influencing Preservice Teachers’ Intention to use Technology: TPACK, Teacher Self-Efficacy, and Technology Acceptance Model.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 21 (3): 348–359. doi:10.30191/ETS.201807_21(3).0005.

- Karaseva, A., P. Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, and A. Siibak. 2013. “Comparison of Different Subject Cultures and Pedagogical use of ICTs in Estonian Schools.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 8 (3): 157–171. doi:10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2013-03-03.

- Kim, K., and L. Ashbury. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Research Evidence from Interviews with Primary and Secondary Teachers in England.” Accessed January 2021. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/9038/pdf/.

- König, J., D. J. Jäger-Biela, and N. Glutsch. 2020. “Adapting to Online Teaching During COVID-19 School Closure: Teacher Education and Teacher Competence Effects among Early Career Teachers in Germany.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 608–622. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650.

- Lawless, K. A. 2016. “Educational Technology.” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3 (2): 169–176. doi:10.1177/2372732216630328.

- Lawrence, Japhet E., and Usman A. Tar. 2018. “Factors That Influence Teachers’ Adoption and Integration of ICT in Teaching/Learning Process.” Educational Media International 55 (1): 79–105. doi:10.1080/09523987.2018.1439712.

- Lindsay, L., and R. Whalley. 2020. “Building Resilience in New Zealand Schools Through Online Learning.” Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, 55–58.

- Maher, Damian. 2020. “Video Conferencing to Support Online Teaching and Learning.” In Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, 91–96.

- Mailizar, Almanthari, Maulina Abdulsalam, and Bruce Suci. 2020. “Secondary School Mathematics Teachers’ Views on e-Learning Implementation Barriers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Indonesia.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education 16 (7): 1–9. doi:10.29333/ejmste/8240.

- Makki, Taj W., LaToya J. O'Neal, Shelia R. Cotten, and R. V. Rikard. 2018. “When First-Order Barriers are High: A Comparison of Second- and Third-Order Barriers to Classroom Computing Integration.” Computers & Education 120: 90–97. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.005.

- McCormack, J. 2023. “Stormont Crisis: Ni Secretary Invites Parties to Hold Deadlock Talks”. BBC News, January 4. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-64166307.

- Mejia Rodriguez, A. M., A. Strello, R. Strietholt, and A. Christiansen. 2022. “A Booster for Digital Instruction: The Role of Investment in ICT Resources and Teachers’ Professional Development”. IEA Compass: Briefs in Education. Number 18. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. https://www.iea.nl/sites/default/files/2022-09/Compass%20Brief%2018%20The%20Role%20of%20Investment%20in%20ICT%20Resources.pdf.

- MILES, MATTHEW B, and A. MICHAEL HUBERMAN. 1984. “Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft.” Educational Researcher 13 (5): 20–30. doi:10.3102/0013189X013005020.

- Niemi, H. M., and P. Kousa. 2020. “A Case Study of Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions in a Finnish High School During the COVID Pandemic.” International Journal of Technology in Education and Science 4 (4): 352–369. doi:10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.167.

- NI Screen/RSM Consulting. 2018. “Review of Digital Education Policy and Implementation in UK and Ireland.” https://www.northernirelandscreen.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/RSM-Final-Report-Review-of-Digital-Education-Policy-and-Implementation-in-UK-and-Ireland.pdf.

- OECD. 2016. “Teachers’ ICT and Problem-Solving Skills: Competencies and Needs.” In Education indicators in focus. No. 40, Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm0q1mvzqmq-en.

- OECD. 2020. “Teachers’ Training and Use of Information and Communications Technology in the Face of the COVID-19 Crisis.” In Teaching in Focus. No. 35. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/696e0661-en.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Player-Koro, C. 2012. “Factors Influencing Teachers’ Use of ICT in Education.” Education Inquiry 3 (1): 93–108. doi:10.3402/edui.v3i1.22015.

- Scully, D., P. Lehane, and C. Scully. 2021. “‘It is no Longer Scary’: Digital Learning Before and During the Covid-19 Pandemic in Irish Secondary Schools.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 30 (1): 159–181. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2020.1854844.

- Selwyn, N. 2017. Education and Technology: Key Issues and Debates. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Shin, J. K., and J. Borup. 2020. “Global Webinars for English Teachers Worldwide During a Pandemic:“They Came Right When I Needed Them the Most.” In Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, 157–162.

- Tashakkori, A, and C Teddlie. 1998. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tondeur, J., J. van Braak, P. Ertmer, and A. Ottenbreit-Leftwich. 2017. “Understanding the Relationship Between Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs and Technology use in Education: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence.” Educational Technology Research and Development 65: 555–575. doi:10.1007/s11423-016-9481-2.

- Tribukait, M. 2020. “Digital Learning in European History Education: Political Visions, the Logics of Schools and Teaching Practices.” History Education Research Journal 17 (1): 4–20. doi:10.18546/HERJ.17.1.02.

- Vongkulluksn, Vanessa W., Kui Xie, and Margaret A. Bowman. 2018. “The Role of Value on Teachers’ Internalization of External Barriers and Externalization of Personal Beliefs for Classroom Technology Integration.” Computers & Education 118: 70–81. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.009.

- Vu, Phu, Richard Meyer, and Kelli Taubenheim. 2020. “Best Practice to Teach Kindergarteners Using Remote Learning Strategies.” In Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, 141–144.

- Walsh, B. 2017. “Technology in the History Classroom.” In Debates in History Teaching, edited by I. Davies, 250–261. London: Routledge.

- Winter, Eileen, Aisling Costello, Moya O’Brien, and Grainne Hickey. 2021. “Teachers’ Use of Technology and the Impact of Covid-19.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 235–246. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916559.

- The World Bank, UNESCO and UNICEF. 2021. “The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery.” Washington D.C., Paris, New York: The World Bank, UNESCO, and UNICEF. Accessed January 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/the-state-of-the-global-education-crisis-a-path-to-recovery.

- Zubković, Barbara Rončević. 2017. “Predictors of ICT Use in Teaching in Different Educational Domains” European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research 11(4s):145-154. doi:10.26417/ejser.v11i2.p145-154

![Figure 6. Teachers’ questionnaires: familiarity with software and hardware [NB data collected 2019].](/cms/asset/97e79829-9972-4eb5-b0e7-c51c7e9beccb/ries_a_2209853_f0006_oc.jpg)