ABSTRACT

Geography is a subject in the Primary Curriculum in Ireland. It is taught in all schools with some examples of engaging and challenging practices, characterised by enquiry-based learning (EBL) of a range of content, with learning occurring inside and out. In other settings, Geography is more limited in scope and children’s geographical experiences in school are minimal. There is a myriad of reasons for this range of practice. One significant feature is the lack of funding or provision for continuing professional development (CPD) for primary teachers in Geography. This paper outlines a project to create school-based CPD for teachers in primary geography. The results of the project are that the school-based CPD, designed by teachers can provide support them to enact the curriculum as well as providing engaging, interesting and enjoyable experiences for teachers. The findings also suggest that such CPD can also have a positive impact on children’s experiences of Geography, through enhanced practices by teachers. The implications for such findings are discussed in relation to curriculum change.

The context of primary geography in Ireland

Within the following section we set the context for this paper, outlining the position and context of primary geography in terms of geographical learning, geography curricular and teacher education before considering teachers’ professional development.

As the International Geographical Union (IGU) state, geography is an ‘informing, enabling and stimulating subject at all levels in education, and contributes to a lifelong enjoyment and understanding of our world’, with purpose as ‘geographical education is indispensable to the development of responsible and active citizens in the present and future world’ (IGU Citation2016, 4). Reflecting the importance of the subject, primary geography is an educational experience for children that is deeply rooted in enquiring about places. The Primary Curriculum for Geography (PCG) in Ireland outlines that ‘geographical activities should be based on the local environment and all pupils should have opportunities to explore and investigate the environment systematically and thoroughly’ (Citation1999, 19). Although it is a time of curriculum change in Ireland it is likely geography within the Social and Environmental Education curriculum will have similar provision (NCCA Citation2023). There is evidence of new teachers on the island of Ireland embracing such engaging practices (Greenwood et al. Citation2020) as well as it being explicit in teacher education (Pike et al. Citation2023). However, it also appears that teachers can use teacher-led, transmissive methods of enacting the curriculum, including the PCG (Pike Citation2011; Usher Citation2023; Citation2021; Waldron et al. Citation2007; Citation2009). This pattern of locality-focused enquiry-based curriculum lacking in children’s education is apparent internationally (Catling and Morley Citation2013; Lane Citation2015). Considering these, among other studies, educational researchers advocate for further research into teacher practices regarding geography education and curriculum implementation (Catling Citation2017; Cummins Citation2010; McNally Citation2012). The Primary Curriculum in Ireland is currently in a period of change, with the Primary Curriculum Framework launched in March 2023 (NCCA Citation2023). This will bring changes to the structure and content of the current curriculum, including change in the ‘enquiry’ grouping of history, geography and science, as well as a new emphasis on integration especially between geography and history (NCCA Citation2023; Pike et al. Citation2023). It is hoped this study along with other research within Irish Educational Studies and elsewhere will help inform such changes.

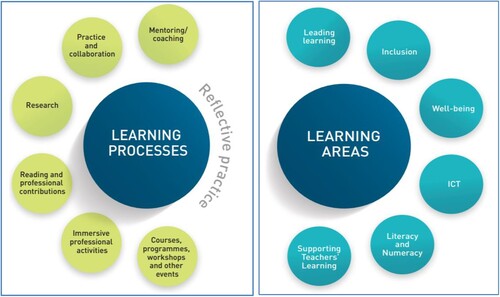

This paper focuses on research on teachers’ professional development, and the recent Primary Curriculum Framework specifies the need for CPD for teachers (Citation2023). However, it only alludes to how this will be carried out, perhaps as CPD for teachers will ultimately be the responsibility of the Department of Education, not the NCCA. And such CPD will need to align with the Teaching Council’s ‘Cosán’, the framework for teachers’ professional development (Citation2016). With this framework, the teacher is placed at the centre of their CPD, and granted a level of autonomy, acknowledging the different ways in which they learn (see ).

Figure 1. Teacher learning processes within the Cosán framework (TC Citation2016, 15 and 19).

Along with the learning processes of teachers, the Cosán framework also highlights six learning areas which are to be targeted in relation to CPD (). Like systems elsewhere (Catling Citation2017), this national framework of CPD does not feature any subjects as a priority, nor the development of teachers’ subject knowledge. This is despite literature which note the lack of CPD for teachers in geography, advocating for at least some such opportunities for teachers to engage with geography (Pike Citation2016; Usher Citation2020; Citation2021). It is hoped this study will help decision makers reflect on the possibilities for and significance of school based CPD for teachers.

A framework for primary geography

The research presented in this paper involved engaging teachers in high-quality practices in geography as part of their CPD. The basis of high-quality geography within the study is based on three key elements of primary geography from the research and curriculum: the use of children’s ‘ethno’ or everyday geographies, enquiry-based stances and strategies and the use of the locality:

Using and developing children’s ‘Ethno-geographies’

Constructivist theories, based on the work of Piaget, Dewey and others, stress the importance of the role of the child in building, or constructing, their own knowledge (Dewey Citation1915; Piaget Citation1932). In Ireland, the curriculum places the child at the centre of their learning and is underpinned by constructivist theories (McCoy et al. Citation2012). The curriculum dictates that teaching should also be built upon children’s previous knowledge and address their misconceptions (NCCA Citation1999).

Enquiry-Based learning stances and strategies

Also stemming from the work of Dewey, Greenwood et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the enquiry-based learning (EBL) approach is a suitable methodology for teachers to identify children’s previous knowledge and place children at the centre of their learning. Catling & Martin demand a less structured curriculum, in which children are recognised as ‘contributors rather than beneficiaries’, and believe it is necessary in order to fully implement an enquiry-based approach to teaching geography (Citation2011, 332). Roberts (Citation2013) outlines the four essential characteristics of EBL ; being is question-driven and encourages a questioning attitude towards knowledge, it involves studying geographical data and sources of information as evidence, making sense of information in order to develop understanding and finally reflecting on learning. There is clear evidence that children appreciate such approaches (Pike Citation2016; Usher Citation2023). And whilst it was envisaged that teachers would be afforded autonomy in their teaching due to both the enquiry approaches and menu structure of the 1999 PCG, they are constrained by many external requirements and policies (Usher Citation2021). This may account for studies which show that EBL approaches, despite the advantages mentioned previously, can be limited in classrooms (Greenwood et al. Citation2020; Usher Citation2021).

Using the outdoors as a learning resource

Outdoor learning is an aspect of primary school that children enjoy participating in (Pike Citation2011). The use of the locality is explicitly outlined in the PCG as a means of developing the main geographical concepts, including a sense of space and place (NCCA Citation1999). The locality provides context for learning about place(s) and environmental awareness and care (Dolan Citation2016; Owens Citation2013). However, studies suggest that outdoor learning is not widely implemented by teachers in primary geography (Usher Citation2021; Citation2023). Overall, literature remains optimistic about the potential for this to change (Pike et al. Citation2023). Moreover, teachers’ enthusiasm for learning and developing their own pedagogical skills has been widely observed (MacQuarrie Citation2018; Pike Citation2016).

Research focus and questions

The study presented here stems from an interest in decisions which primary teachers make around the curriculum. To begin to answer a topic as broad as this, more focused questions were designed to guide the research, these were:

What are teachers’ opinions about geography?

How do teachers plan for primary geography education?

How confident are primary teachers in enacting the primary geography curriculum?

What methodologies are commonly used to enacting the primary geography curriculum?

What support do teachers need to aid them in the successful implementation of the primary geography curriculum?

What impact does school based CPD have on teachers’ thinking and practices around the primary geography curriculum?

The research which follows uses the questions outlined above to guide the review of literature, the research methodologies chosen, the collection and analysis of data, and the interpretation of findings.

Literature on teachers’ professional knowledge

Teachers’ knowledge and decisions about CPD

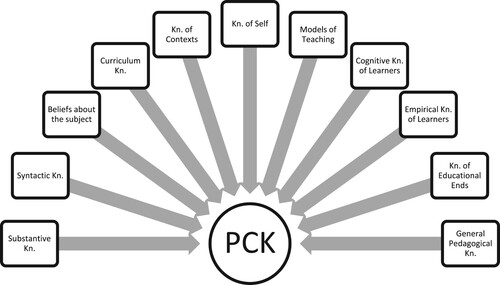

In order to understand and evaluate teacher knowledge, it is useful to refer to Shulman (Citation1986). He identified a range of knowledge bases teachers should have, with three categories of content knowledge: Firstly, Subject-Matter Knowledge (SMK), the amount and organisation of knowledge about facts, concepts and principles of the subject. Secondly, Pedagogical Knowledge, the knowledge of the curriculum topics and methodologies of teaching. And finally, the focus of this research, Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), is described as the point where SMK and pedagogical knowledge overlap. As a result of Shulman’s conceptualisation of PCK, along with the other knowledge bases mentioned above, other educationalists have developed their thinking around PCK. Turner-Bisset (Citation1999) built on Shulman’s model by breaking the concept of PCK down into 11 components, she described how integration must occur among the components for a teacher to demonstrate effective PCK, as shown in .

Figure 2. Eleven Knowledge (Kn.) Bases of PCK (adapted from Turner-Bisset Citation1999, 47).

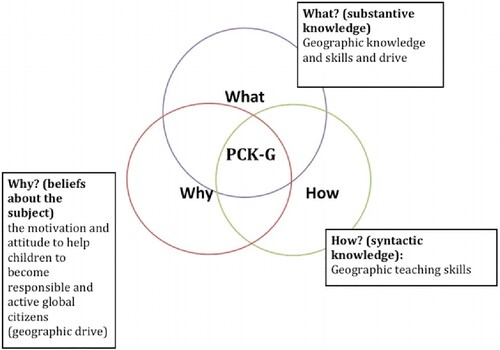

Martin (Citation2005), reformulated Turner-Bisset’s (Citation1999) detailed model of PCK, and the knowledge bases which PCK encompasses, into three seemingly simple questions: What am I going to teach? How am I going to teach it? Why am I going to teach it in this way? Research by Blankman et al. (Citation2015) supported Martin’s (Citation2005) study and refined these questions to demonstrate how the knowledge represented by each of these questions, when integrated, form teacher PCK. The framework was made specific to the teaching of geography, referring to pedagogical content knowledge in relation to geography (PCK-G).

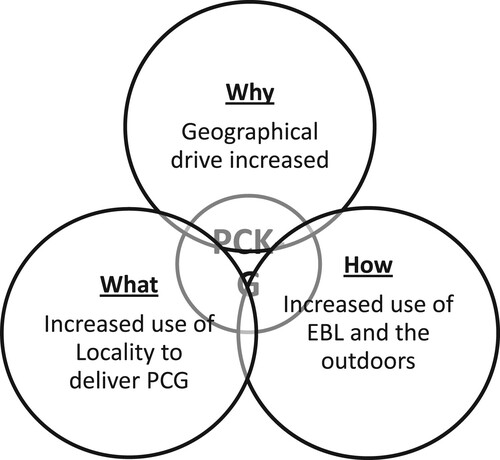

The PCK-G framework, (Blankman et al. Citation2015), was the theoretical lens for this research, through which the participants’ decisions regarding the PCG, were analysed. illustrates how the three questions of what, how and why teachers make certain decisions around the PCG, interconnect to form PCK-G, a knowledge base which the authors describe as central to the effective teaching of geography.

Figure 3. Framework for PCK-G (Blankman et al. Citation2015, 84).

There is an inbuilt variety to CPD provision in Ireland, depending whether teachers are working in primary or post-primary schools. To date, the state’s Professional Development Service for Teachers and Junior Cycle Support Programme provides teachers’ CPD at second level. This includes supports and opportunities for teachers, such as in-person and online seminars, cluster meetings for newly qualified teachers and tailored support based on school-specific needs. However, there is little opportunities provided for teachers to engage with CPD in primary geography. The most popular form of CPD in Ireland are primary summer courses, available for teachers to attend throughout the months of the summer holidays. Teachers are entitled to a number of extra personal vacation days in lieu of attending summer courses (Department of Education and Science Citation2009). However, the level of impact of summer courses on teachers’ attitudes and practices has been criticised (Foley Citation2017; Sugrue Citation2002), with educationalists highlighting the timing of these courses as a concern.

Impact of CPD on teachers’ attitudes and practices

Research analysing the impact of CPD courses in the primary sector is relatively sparse, with data concerning the PCG particularly scarce. Literature yields inconsistent findings in relation to the impact of such CPD on teachers’ attitudes and practices. Evidence shows an increase in primary teachers’ enthusiasm and confidence in teaching geography after a course of CPD (Conner Citation1998; Keeling Citation2009). Studies on CPD in Science and Physical Education, also found teachers noted increased confidence levels, leading to greater engagement with the subject and unfamiliar topics after CPD (Harris, Cale, and Musson Citation2012; Murphy, Smith, and Broderick Citation2019; Smith Citation2015;). However, it has also been noted that the impact of the CPD on the wider school, was limited by the enthusiasm and participation of teachers who did not participate in the CPD sessions themselves (Conner Citation1998).

The increase in teachers’ confidence levels, outlined in the studies above, could be a result of increased SMK gained from participating in the CPD. In the field of primary geography identify SMK as essential for teachers to adapt and enact the geography curriculum effectively (Owens Citation2013; Waldron et al. Citation2007; Citation2009). Research has shown that CPD in primary geography has had a positive impact on teachers’ SMK (Keeling Citation2009), as well as an increase in the use of child-led pedagogies and EBL (Harris, Cale, and Musson Citation2012; McNally Citation2012). Researchers also suggest teachers may view textbooks as a familiar and safe method of enacting the PCG when their confidence is lacking (Usher Citation2020).

However, educationalists have debated the true impact on teachers’ practices. Jarvis and Pell (Citation2004) also noted that while schools’ and teachers’ capacity to plan learning appears to have improved during a programme of CPD, implementation levels were relatively low and varied between teachers and subjects (467). Sugrue (Citation2011) argued that CPD delivered in an Irish context was ‘more successful at information-giving than changing practice’ (803).

Methodology

An ‘Action Research Case Study’ approach was employed for this research, to accurately and vividly describe the unique experience of the participants. The study aimed to gain an insight into factors which affected decisions around the PCG before a short course of CPD was implemented and then to evaluate the effect this course of CPD had on such decisions, as shown in . Basit’s definition of a case study highlights its relevance, as it: ‘presents a rich description and details of the lived experiences of specific cases or individuals and offers an understanding of how these individuals perceive the various phenomena in the social world and their effect on themselves’ (Citation2010, 20).

Table 1. Research design for the study.

The qualitative approach was adopted to develop a descriptive and contextualised viewpoint (Cresswell Citation2007), allowing for a focus on the lived experiences of the participants, and for the research to accurately reflect the study (Maxwell Citation2005). In this way, important themes emerged from the study and allowed the findings to be true to the participants’ experiences, rather than being driven by the researcher. However, it was systemically acknowledged that the data collected from this study could not be generalised to the entire population. Overall, the qualitative investigation aimed to produce findings which readers could relate to and use to gain a deeper understanding of their own and others’ situations (O’Donoghue Citation2006).

Since statistical generalisation, was not the goal of this qualitative study, nonprobability sampling was used for selecting the participants. More specifically, purposive sampling was employed. The target sample were primary school teachers who did or had worked in an Irish mainstream setting at the time of the study. Teachers involved had varied years’ of experience and were a group through which the greatest insight and understanding could be gained (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2016).

The research was concentrated on one research site which ensured that participants could be accessed and data collected efficiently (Denscombe Citation2010). The school in which the participants worked was chosen as the research site. The school is located in suburban Dublin, with access to a large local park and seashore. Individual interviews were conducted with participants before and after the CPD sessions. Interviews with an interpretivist approach were drawn upon, emphasising social interaction as the basis for knowledge. Basit (Citation2010) described an interview as an interaction between two people on a topic of mutual interest, in this case primary geography. And so, semi-structured interviews were used for the purpose of collecting data for this study, allowing for unanticipated themes, concerns and viewpoints to emerge. These later informed the content and structure of the CPD sessions.

Coding was used to analyse the data collected from interviews. Codes were assigned to themes which emerged from more than one participant. The researcher systematically analysed interview transcripts and wrote a descriptive code beside each relevant point (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). Analysis was conducted simultaneously with data collection. Data findings revealed important themes which informed the design of CPD sessions. A number of threats to the validity of data collection were identified by the researcher and measures that were taken to counteract these threats. The researcher took extra care to avoid leading questions during post-interviews and to remove bias from her interpretation of the participants’ experience of the CPD sessions.

Through analysis of the pre-interview data, themes were identified as important to address during the CPD sessions. Misconceptions of content outlined in the PCG, use of the locality to enact the PCG and a lack of progression and collaborative planning were highlighted as the most important issues to address. Research on effective teacher CPD by Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) formed the basis for the structure of the CPD sessions in this study. Sessions engaged with materials suitable to the classroom, were school-based and required active engagement. The sessions also focused on implementing methodologies outlined in the PCG to teach geography lessons. Finally, as suggested by Chalmers and Keown (Citation2006), participants formed a community of practice for geography, where they shared knowledge and designed a whole-school progression plan for using EBL, and use of the school’s locality, to enact the PCG.

Working with the researchers’ colleagues meant a number of actions were taken to ensure validity of the work. To ensure there was no over-rapport between researcher and interviewee, the interview schedule was used to keep focus of interview (Basit Citation2010). Efforts were made to systematically acknowledge researcher bias and to only use the data collected to construct meaning (Rossman and Rallis Citation2017). Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Education, Dublin City University.

Findings and analysis

The PCK-G framework, as outlined previously, is used as a means of interpreting the data collected from pre and post-interviews. The three questions of how, what and why teachers make decisions around the PCG frame the following findings. Therefore the findings are organised around the influences on teachers’ practices, expertise and decisions in relation to primary geography. After this influence and impacts of the CPD sessions are considered.

Initial influences on teachers’ practices

Teachers’ own experiences of learning geography

The participants’ own experiences as students of geography impacted their teaching in different ways. Four of six participants commented that their own exposure to geography in primary school was heavily focused on reading from textbooks and rote learning aspects of physical geography. One participant recalled finding it ‘really difficult to remember all the names and stuff’. Another described similar experiences, ‘I remember there was a lot of learning off of maps which I wasn't eager on. I remember that it was quite difficult and not as enjoyable as it could be.’ As a result of these experiences, these participants illustrated that they tried to avoid teaching in this way by trying to make teaching geography more engaging and making it as interesting. These findings support research that found student teachers, while on placement, use different approaches and are cognisant of not making the same mistakes they perceived their own teachers to have made (Brown et al. Citation1999; Waldron et al. Citation2009).

Post interviews with these participants found that there was no significant change in thinking, they continued to try to avoid the style of teaching which they perceived as negative, but to refine and develop the methodologies which they implement in their classes. The opposite was found for participants who enjoyed their experience of primary geography. Two participants, who enjoyed the subject for different reasons, both tried to replicate their own learning experiences in their teaching. One participant, who shared a similar experience to the participants mentioned above, of rote learning and textbook-focused lessons, enjoyed this style of learning and as a result of this he tried to implement this style of teaching in his own classroom:

It is a teacher led lesson. I might put them in pairs for a quick discussion about maybe what's on the board, what they see, what they think is the reason for something to happen. But I think maybe it's because I enjoy teaching that I actually like being the main person having a discussion about it.

Teachers and teaching methodologies

Many methodologies were mentioned by participants during pre-interviews. Specifically, teacher-led learning, child-led learning and EBL. Only the participant mentioned above, explicitly described his lessons as mostly teacher-led, using a didactic method of delivering the PCG. While the others described child-centred, enquiry-based styles of teaching, further questioning revealed participants were not using these methodologies in the classroom. Participants mostly viewed their role as needing to supplement information in textbooks and to develop content that was covered in textbooks. These findings are supported by literature which shows that there is limited evidence of teachers implementing EBL methodologies in their geography lessons (Cummins Citation2010; Lane Citation2015; McNally Citation2012; Pike Citation2011).

Analysis of post-interview data revealed the impact of the CPD sessions on this aspect of the teachers’ thinking. When asked the question: ‘How would you go about planning a geography lesson?’, every participant included an EBL approach. All the participants also highlighted the importance of allowing the children a level of autonomy of learning, as one noted, ‘I will let the children drive the lesson, then they are more willing to learn and will try a little bit harder’. The CPD sessions also had an impact on how teachers viewed their role. Post interviews demonstrated how the teachers had developed their thinking from an adult imparting information onto the children in their class to that of a facilitator of learning. When asked to describe a geography lesson they planned to teach after the CPD sessions, all the participants described how they would provide their students with the resources they needed but then allow them to develop their own questions about the topic while scaffolding and supporting them as they went about answering these questions. These findings support existing literature which indicates that CPD sessions have a positive impact on developing child-centred learning approaches, as indicated in the 1999 Primary Curriculum (Conner Citation1998; Murphy, Smith, and Broderick Citation2019).

Children’s learning, including fieldwork

Every participant acknowledged the use of the outdoors or fieldwork as a method of enacting the PCG in their interviews, however, this methodology was not used often or at all by the teachers. Notably, the teachers who did not use the outdoors in their teaching had different reasons for its absence. One participant, in her first year of teaching, shied away from bringing the children outdoors as she felt she did not have the confidence to do so. Another participant felt that fieldwork was ‘done to death in the junior classes’ and she expressed her apprehension of the lack of progression in whole-school planning, from 3rd to 6th class. Other participants echoed her concern and identified a lack of planning for children’s progress as a priority concern. These findings are consistent with existing literature which revealed a significant lack of outdoor learning and fieldwork being implemented as a part of geography in primary schools (Pike Citation2006; Catling Citation2001).

The impact of the CPD sessions on the thinking of the participants is noteworthy. Analysis of post-interviews revealed that the teachers unanimously identified use of fieldwork and the locality as priorities in both their planning and teaching going forward. Another significant impact of the CPD sessions was on the participants who expressed uncertainty around structuring an outdoor lesson. One teacher described the change that occurred to his own thinking. ‘It's not just wandering around looking at trees, but you can plan a lesson based on the local environment. If you do it properly it won’t be wishy-washy’. These findings reflect previous studies which show the impact of CPD sessions on the attitudes and thinking around use of outdoor learning and fieldwork (Murphy et al. Citation2020).

Initial influences on teachers’ expertise

Subject matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge

Participants’ level of SMK was qualitatively assessed initially through interview questions. An analysis of the teachers’ SMK was made by the researcher from participants’ definitions of geography and their level of certification in the subject. All participants had studied geography to Leaving Certificate (LC) level (the final examination of the Irish secondary school system). However, analysis of data suggested that participants had varying levels of SMK. Participants’ level of SMK was highest in the area of physical geography, which was also the aspect of geography which participants were most confident in teaching. Possibly due to the emphasis on physical geography on the LC curriculum. The link between high SMK of the topic and confidence in teaching is important to consider. One participant had a degree in geography, and was the only participant to have recently designed an enquiry specific to the school’s locality and having used fieldwork as a pedagogy. This finding contradicts research which found student teachers who had a higher qualification in geography demonstrated the same level of PCK as those without (Morley Citation2012). It supports findings which suggest that previous academic and school training affect how geography teachers conduct field-based enquiry (Seow et al. Citation2020).

A low level of SMK was also found to have an impact on participants’ unwillingness to adapt the curriculum in order to design a local enquiry. One participant was hesitant to bring her students outdoors and to learn about the locality. She was nervous that she would not have the SMK to answer questions which children could ask without her laptop if she left the classroom. These findings support studies that identify SMK as essential for teachers to adapt and enact the geography curriculum effectively (Owens Citation2013; Waldron et al. Citation2007).

Pedagogical knowledge, which includes teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning, and educational ideology (Martin Citation2008), also appeared to vary among participants. Some teachers displayed strong pedagogical knowledge through explanations of use of groupwork, gathering additional resources, use of initial stimuli and sourcing children’s prior knowledge before starting a topic. However, as mentioned above, the level to which these practices were implemented in the participants’ teaching was perceived by the researcher to be low.

The CPD sessions the participants engaged with were designed around developing their use of the locality as a method of teaching the PCG and the EBL approach to teaching geography. Although the impact of the CPD sessions on SMK and pedagogical knowledge could not be quantifiably measured, post-interviews highlighted positive changes in participants’ confidence and perceptions of their own knowledge levels.

Originally, I said my confidence was a barrier to teaching about the locality and my subject-knowledge in general, the actual content of what I was teaching. I do feel a lot more confident with the local now. The local was actually my biggest worry because I didn’t know anything about [the local area] and I feel that I know a lot now.

The varied levels of SMK among the teachers add to the question of whether there is a place for ‘subject specialists’ within primary teaching. It also highlights the pressure on generalist teachers to ‘know everything’ and raises the question of whether this is an unrealistic expectation of primary teachers, especially those who are new to the profession.

Planning for primary geography

Pre-interview data indicated that the participants of the study went about planning their geography lessons in very different ways. Starting with the curriculum books and working back, using and supplementing the textbook as a reference point/guide of what to teach and using other Social, Environmental and Scientific Education subjects as a starting point were all planning strategies which were employed by the participants. These findings contradict previous studies which suggest Irish primary teachers plan the majority of their geography lessons around the textbook (McNally Citation2012; Usher Citation2020). Three out of 6 teachers in the study raised concerns over progression in geography throughout the school. They identified a need for a plan to be put in place to rectify topics being repeated or missed out altogether. The CPD sessions which the participants engaged in were centred around designing a relevant and accessible progression plan for local studies and fieldwork in geography.

Post-interviews indicated the impact the CPD sessions had on teachers’ planning for geography. participants were asked the same question as was posed to them in the initial interviews: ‘How would you go about planning a unit of work in geography?’. Three main strategies were identified; that of seeking the children’s prior knowledge (which increased from one participant identifying it as a strategy in pre interviews to three teachers in post interviews), the use of enquiry-questions (mentioned by four teachers as a starting point for their lessons) and use of the locality as a stimulus for enquiry. Furthermore, the progression plan was referenced by all the participating teachers as a valuable resource going forward. One participant commented,

By having a clear progression, teachers can confidently plan investigations and fieldwork that build on previous experiences, without overlapping. It gives a clear framework for enquiry and pupil-led learning, without being prescriptive. I think children will have more meaningful experiences of geography because of this.

Impacts of the CPD on teachers’ decisions

Community of practice

The decisions primary school teachers make around the PCG are affected by their ‘geographical drive’ (Blankman et al. Citation2015). Studies show that the whole-school climate or approach to a subject, plays an important role in how effectively that subject is taught by individual teachers. The schoolwide climate, whether positive or negative, impacts teachers’ geographical drive, or motivation to help children become responsible global citizens (Brooks Citation2012). Participants in this study revealed that they felt isolated as teachers of geography and identified a lack of resources and guidance in relation to the PCG. Teachers also commented that they did not know of any designated person in the school whom they could approach for advice on teaching the PCG.

As a result of the CPD sessions, teachers formed a community of practice. Post-interviews showed that teachers felt more supported and were able to identify colleagues to whom they could seek support and guidance from.

The fact that we have a group, means we can ask a few people what they think. People that have some interest in the local environment, at least now you know the people that you are asking are interested in it.

Teacher identity

Teacher identity was a strong theme which emerged from the post-interviews. During the initial interviews, the participating teachers did not refer to their teacher identity in any way. During the post-interviews, four teachers specifically identified themselves as ‘geographers’ (Seow Citation2016). One participant commented, ‘Well now I think that we are all geographers. I think that every day I would be a geographer in some way without realising it’. Previous research has suggested that CPD opens a space for discourse for teachers to reflect on their professional identities, and results of this study substantiate such findings (Clarke Citation2009). These data are also significant as studies have shown that teachers who recognise themselves as geographers, and acknowledge the relevance of their own prior knowledge, possess a greater sense of agency and ability to adapt the geography curriculum to include such methodologies as local studies and EBL in their teaching (Clarke Citation2009; Martin Citation2008). Furthermore, the previous themes which have emerged, and which have been analysed above support the teachers’ judgements in suggesting that they identify as geographers. Increased enthusiasm for EBL, use of the outdoors and an ability to adapt the curriculum in a way which allows them to implement these methodologies within its confines, echoes the definition of a ‘geographer’ (Clarke Citation2009; Martin Citation2008; Seow Citation2016; Seow et al. Citation2020).

Teachers’ perceptions of the CPD sessions

An important finding of the study was the positive response of the participants to the style of CPD which they took part in as a part of the research. Motivational factors for participants engaging with CPD were also explored. The participants were questioned about previous CPD experiences they had before the study and about the factors which influenced them to engage with such experiences. Responses revealed that a desire to improve their own teaching skills and knowledge, and therefore job satisfaction, emerged as motivation to engage with CPD for two of the participants. Teachers who fell within this category had completed evening courses in the local education centre throughout the year as well as one participant having completed a Professional Diploma in Education (with a focus on special needs). These findings contradict research by McMillan, McConnell, and O’Sullivan (Citation2014) which found career advancement to be a prevalent factor for teacher engagement with CPD.

This was not the case for all of the participants, however. Receiving extra personal vacation days for completing summer courses was the most common reason for participants to engage with CPD, with 3 of the six teachers naming this as their biggest motivation. One teacher in this group commented that he chose the topic of the CPD course as it was ‘easy to get through’. The participants of this group appear to be influenced by the external stimulus of such days in lieu, supporting work by Foley (Citation2017).

The participants were also questioned on their opinions of the format and content of the CPD sessions which were part of the study. Participants perceived the sessions as effective, with the collaborative nature of the CPD being highlighted as essential. All participants reported having had a positive experience, as well as all participants commenting that they would be eager to continue the CPD sessions in order to develop the remaining areas of the PCG as well as other subjects, as one noted ‘I would have loved if there had been time or scope within the CPD to compile information on each of the areas identified in the progression plan’.

It is also important to note that no teacher had previously completed a CPD course which was solely focused on geography. However, two teachers had engaged with a general Social, Environmental and Scientific Education (geography and history) course, which touched ‘minimally’ on geography. During post-interviews, all participants commented that they would be interested in choosing geography as a subject for their CPD if there was one available to them, an important and encouraging finding for the future of primary geography.

Summary of findings

Firstly, it appears that teachers in the case study were not using the school’s locality as a method of enacting the PCG. Although most participants demonstrated that they did not rely on the class textbook as a focus of their geography lessons, it was clear that the textbook played a role in determining which topics which were chosen from the menu curriculum. It seems that use of the textbook for choosing topics meant that the children’s locality was omitted from teachers’ planning. Furthermore, findings also suggest that most teachers in this school were not using the outdoors to teach the content and skills outlined in the PCG. Encouragingly, however, it appears that three sessions of CPD had a positive impact on the participants’ attitude and practices with all teachers commenting that they intend to use the school’s locality to enact the PCG in future lessons.

Secondly, interviews revealed that teachers in the study were aware of the various teaching methodologies outlined in the PCG (NCCA Citation1999). However, a number of factors, such as a lack of SMK (knowledge about local geography) or a lack of pedagogical knowledge (classroom management, curriculum knowledge) was stopping them from implementing EBL in their teaching. Participants explained how they went about using these methodologies, and data findings suggest they perceived themselves to be implementing these strategies more commonly than they were in practice. Teachers’ willingness and enthusiasm to learn about and plan for the use of new enquiry-based methodologies was a significant finding from post-interviews.

Thirdly, collaborative planning arose as an issue among the participants. Teachers mentioned repetition of topics from year to year and a lack of progression as a concern they had in relation to the PCG. Teachers were less likely to engage with outdoor learning and fieldwork as they felt that they would be teaching material which was already covered in previous years. Moreover, teachers felt the whole-school geography plan which existed did not have a practical use and there was no member of staff whom they felt they could approach for support or guidance in the subject. As a result, the designing of a progression plan for geography was incorporated into the CPD sessions. Post-interviews revealed the positive attitude of teachers towards the plan. Consequently, participants demonstrated a desire to widen the scope of the plan from local fieldwork to all strands of the curriculum and to other subjects of the 1999 Primary Curriculum. This finding may have future implications for teacher CPD.

The effect of three sessions of CPD on the decisions teachers make around the PCG was a core theme of this study. Findings from this case study contribute to existing literature on the effect of CPD on teachers’ practices in geography education. The course of CPD appeared to have a positive effect on the teachers’ thinking and practices around the PCG and their level of PCK-G in terms of how and why teachers approach the PCG in a particular way. The teachers’ geographical drive or why they make certain decisions when teaching geography appeared to have been impacted by the CPD sessions. Evidence of this was expressed during post-interviews, where the participants identified as ‘geographers’ (Seow Citation2016). Their willingness to learn and engage with future CPD both in geography and other subjects of the 1999 Primary Curriculum demonstrates their increased geographical drive. Teachers demonstrated increased SMK in terms of what they teach. This included increased confidence in SMK about the schools’ locality and more holistic definitions of geography. How the participants teach was impacted by their engagement with the CPD sessions. All teachers mentioned EBL, use of the outdoors and using the schools’ locality in their post-interviews as methodologies which they will implement in their geography lessons going forward.

In conclusion, the teachers in this study demonstrated an eagerness to implement the PCG to the highest quality, however, factors such as a lack of SMK, pedagogical knowledge, whole-school planning and support hindered them in achieving this. Their engagement with three sessions of CPD showed an improvement in all aspects of the theoretical framework, which indicates an improvement in the participants’ PCK-G overall (see ).

Conclusions and implications for further research

Although the qualitative nature of the study does not allow for generalisation, the findings do suggest possible implications for teachers of geography, school management and teacher CPD in Ireland. In relation to teaching methods, teachers involved in this study demonstrated knowledge of various teaching methodologies, however, they did not appear to be implementing these methodologies in their teaching. And so, opportunities for teachers to work together to share and exemplify such enquiry methods, which are outlined in many subjects of the 1999 Primary Curriculum, should be availed of.. In relation to geography content, it was apparent that teachers in the case study who were from the school’s locality were more familiar with local geography and therefore were more likely to use the outdoors or the locality to enact the PCG. Therefore, it would be beneficial for schools to provide incoming non-local teachers with SMK, specific to the school’s local area, especially as in this study they were seldomly doing so. Increased local knowledge could have a positive impact on other subjects of the curriculum, including History and Science. An unexpected finding of the study was the extent to which teachers are relying on access to the internet to enact their lessons. Where laptops and computers were once seen as an excellent resource, this paper raises the question as to whether inexperienced teachers are now over-reliant on their devices, impacting their ability to effectively adapt the curriculum.

As stated at the outset of this article, geography is indispensable, important and informative for young people. However, it appears that limited CPD for teachers was insufficient for the effective implementation of the recommended pedagogies of the geography curriculum. Lessons must be learned from these shortcomings so that the potential of the current and new curriculum can be fully accomplished (NCCA Citation1999; Citation2023). Findings from this study could help in this process, as it was evident that local, school based collaborative CPD was favoured and considered to more effective by the teachers than traditional CPD involving visiting experts. They were motivated by their own learning as a community of practice. Findings also showed that the participants valued the voluntary nature of the CPD as they were able to bring their own interests and knowledge to the group, without expectations from others. In general, limited opportunities for CPD in primary geography remain an issue and findings from this study suggest that creating more opportunities for teachers to engage with CPD in this area would have a positive impact on the planning and teaching of geography. Finally, it is evident that further research is needed to identify the most effective form of CPD for the new Primary Curriculum Framework, as well as for the development of a national framework for teacher CPD in Ireland. We hope this study will contribute to evidence of the significance of teachers working together as a community of practice for geography.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our thanks to the teachers who took the time to engage in this project during an extremely challenging time in schools. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers of this paper, for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa Clarke

Ms Lisa Clarke is an Assistant Professor in Geography Education in the School of STEM Education, Innovation and Global Studies in Dublin City University.

Susan Pike

Susan Pike is an Assistant Professor in Geography Education in the School of Education in Trinity College Dublin.

References

- Basit, Tehmina N. 2010. Conducting Research in Educational Contexts. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Blankman, Marian, Joop van der Schee, Monique Volman, and Marianne Boogaard. 2015. “Primary Teacher Educators’ Perception of Desired and Achieved Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Geography Education in Primary Teacher Training.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (1): 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.967110.

- Brooks, Clare. 2012. “Changing Times in England: The Influence on Geography Teachers’ Professional Practice.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 21 (4): 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2012.725966.

- Brown, Tony, Olwen Mcnamara, Una Hanley, and Liz Jones. 1999. “Primary Student Teachers’ Understanding of Mathematics and Its Teaching.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (3): 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250303.

- Catling, Simon. 2001. “English Primary Schoolchildren’s Definitions of Geography.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 10 (4): 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040108667451.

- Catling, Simon. 2017. “Not Nearly Enough Geography! University Provision for England’s Pre-Service Primary Teachers.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 41 (3): 434–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1331422.

- Catling, Simon, and Fran Martin. 2011. “Contesting Powerful Knowledge: The Primary Geography Curriculum as an Articulation Between Academic and Children’s (Ethno-) Geographies.” The Curriculum Journal 22 (3): 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.601624.

- Catling, Simon, and Emma Morley. 2013. “Enquiring Into Primary Teachers’ Geographical Knowledge.” Education 3-13 41 (4): 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.819617.

- Chalmers, Lex, and Paul Keown. 2006. “Communities of Practice and the Professional Development of Geography Teachers.” Geography 91 (2): 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2006.12094156.

- Clarke, Matthew. 2009. “The Ethico-politics of Teacher Identity.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 41 (2): 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00420.x.

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education. 5th ed. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Conner, Colin. 1998. “A Study of the Effects of Participation in a Course to Support the Teaching of Geography in the Primary School.” Teacher Development 2 (1): 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664539800200036.

- Cresswell, J. W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. 2nd ed. California: Sage Publication Inc.

- Cummins, M. 2010. “Eleven Years On: A Case Study of Geography Practices and Perspectives Within an Irish School.” MEd Thesis. Dublin City University.

- Denscombe, Martyn. 2010. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. Berkshire: Open University Press. https://www.dawsonera.com:443/abstract/9780335241408.

- Department of Education and Science. 2009. Extra Personal Vacation (EPV). Circular 0035/2009. https://circulars.gov.ie/pdf/circular/education/2009/35.pdf.

- Dewey, John. 1915. The School and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dolan, Anne M. 2016. “Place-Based Curriculum Making: Devising a Synthesis Between Primary Geography and Outdoor Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16 (1): 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1051563.

- Foley, Kathleen. 2017. “Models of Continuing Professional Development and Primary Teachers’ Viewpoints.” Irish Teachers’ Journal 5 (1): 55–73. https://www.into.ie/app/uploads/2017/01/21Nov_IrishTeachersJournal2017.pdf.

- Greenwood, Richard, Sandra Austin, Karin Bacon, and Susan Pike. 2020. “Enquiry-Based Learning in the Primary Classroom: Student Teachers’ Perceptions.” Education 3-13 (December): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2020.1853788.

- Harris, Jo, Lorraine Cale, and Hayley Musson. 2012. “The Predicament of Primary Physical Education: A Consequence of ‘Insufficient’ ITT and ‘Ineffective’ CPD?” Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 17 (4): 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2011.582489.

- International Geographical Union. 2016. 2016 International Charter on Geographical Education. IGU Commission on Geographical Education. http://www.igu-cge.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/IGU_2016_def.pdf.

- Jarvis, Tina, and Anthony Pell. 2004. “Primary Teachers’ Changing Attitudes and Cognition During a Two-Year Science In-Service Programme and Their Effect on Pupils.” Research Report’. International Journal of Science Education 26 (14): 1787–1811.

- Keeling, Anne. 2009. “Geography is Happiness.” Primary Geography 68 (1): 15–17.

- Lane, Rod. 2015. “Experienced Geography Teachers’ PCK of Students’ Ideas and Beliefs About Learning and Teaching.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (1): 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.967113.

- MacQuarrie, Sarah. 2018. “Everyday Teaching and Outdoor Learning: Developing an Integrated Approach to Support School-Based Provision.” Education 3-13 46 (3): 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1263968.

- Makopoulou, Kyriaki, Ross D. Neville, Nikos Ntoumanis, and Gary Thomas. 2019. “An Investigation Into the Effects of Short-Course Professional Development on Teachers’ and Teaching Assistants’ Self-efficacy.” Professional Development in Education (September): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1665572.

- Martin, Fran. 2005. The Relationship Between Beginning Teachers’ Prior Conceptions of Geography, Knowledge and Pedagogy and Their Development as Teachers of Primary Geography. Coventry: Coventry University.

- Martin, Fran. 2008. “Knowledge Bases for Effective Teaching: Beginning Teachers’ Development as Teachers of Primary Geography.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 17 (1): 13–39. https://doi.org/10.2167/irgee226.0.

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2005. Qualitative Research Design, An Interactive Approach. 2nd ed. CA: Sage.

- Mccoy, Selina, Emer Smyth, and Joanne Banks. 2012. The Primary Classroom: Insights from the Growing Up in Ireland Study'. Dublin: The Economic and Social Research Institute.

- McMillan, Dorothy, Barbara McConnell, and Helen O’Sullivan. 2014. “Continuing Professional Development Why Bother? Perceptions and Motivations of Teachers in Ireland.” Professional Development in Education 42 (May): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.952044.

- McNally, J. 2012. “Going Places: The Successful Implementation of the 1999 Primary Geography Curriculum.” Master’s thesis. Dublin City University.

- Merriam, S. B., and E. J. Tisdell. 2016. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. 4th ed. NJ: Jossey-Bass.

- Morley, Emma. 2012. “English Primary Trainee Teachers’ Perceptions of Geography.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 21 (2): 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2012.672678.

- Murphy, Clíona, Greg Smith, and Nicola Broderick. 2019. “A Starting Point: Provide Children Opportunities to Engage with Scientific Inquiry and Nature of Science.” Research in Science Education (February), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-019-9825-0.

- Murphy, Cliona, Greg Smith, Benjamin Mallon, and Erin Redman. 2020. “Teaching About Sustainability Through Inquiry-based Science in Irish Primary Classrooms: The Impact of a Professional Development Programme on Teacher Self-Efficacy, Competence and Pedagogy.” Environmental Education Research 26 (8): 1112–1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1776843.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Geography. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2023. Primary School Curriculum Framework. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- O’Donoghue, Tom. 2006. Planning Your Qualitative Research Project: An Introduction to Interpretivist Research in Education. London: Routledge.

- Opfer, V. Darleen, and David Pedder. 2011. “Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 81 (3): 376–407. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Owens, Paula. 2013. “More Than Just Core Knowledge? A Framework for Effective and High-Quality Primary Geography.” Education 3-13 41 (4): 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.819620.

- Piaget, Jean. 1932. The Moral Judgement of the Child. London: Kegan Paul.

- Pike, Susan. 2006. “Irish primary school children's definitions of ‘geography’.” Irish Educational Studies 25 (1): 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323310600597618.

- Pike, Susan. 2011. ““If You Went out It Would Stick”: Irish Children’s Learning in Their Local Environments.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 20 (2): 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2011.564787.

- Pike, Susan. 2016. Learning Primary Geography: Ideas and Inspirations from Classrooms. London: Routledge.

- Pike, Susan, Sandra Austin, Richard Greenwood, and Karin Bacon. 2023. “Inquiry in Teacher Education: Experiences of Lecturers and Student Teachers.” Irish Educational Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2023.2189139.

- Roberts, Margaret. 2013. “The Challenge of Enquiry-based Learning.” Teaching Geography 38 (2): 50–52.

- Rossman, G. B., and S. F. Rallis. 2017. An Introduction to Qualitative Research: Learning in the Field. 4th ed. CA: Sage.

- Seow, Tricia. 2016. “Reconciling Discourse About Geography and Teaching Geography: The Case of Singapore Pre-Service Teachers.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 25 (2): 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1149342.

- Seow, Tricia, Kim N. Irvine, Ismath Beevi, and Tharuka Premathillake. 2020. “Field-Based Enquiry in Geography: The Influence of Singapore Teachers’ Subject Identities on Their Practice.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 29 (4): 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2019.1680001.

- Shulman, Lee S. 1986. “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching.” Educational Researcher 15 (2): 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004.

- Smith, Greg. 2015. “The Impact of a Professional Development Programme on Primary Teachers’ Classroom Practice and Pupils’ Attitudes to Science.” Research in Science Education 45 (2): 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9420-3.

- Sugrue, Ciaran. 2002. “Irish Teachers’ Experiences of Professional Learning: Implications for Policy and Practice.” Journal of In-Service Education 28 (2): 311–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580200200185.

- Sugrue, Ciaran. 2011. “Irish Teachers’ Experience of Professional Development: Performative or Transformative Learning?” Professional Development in Education 37 (5): 793–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2011.614821.

- Teaching Council. 2016. Cosán: Framework for Teachers Learning. Maynooth: Teaching Council. Accessed August, 25 2023.

- Turner-Bisset, Rosie. 1999. “The Knowledge Bases of the Expert Teacher.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (1): 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250104.

- Usher, Joe. 2020. “Is Geography Lost? Curriculum Policy Analysis: Finding a Place for Geography Within a Changing Primary School Curriculum in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 39 (4): 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1697945.

- Usher, Joe. 2021. “How Is Geography Taught in Irish Primary Schools? A Large Scale Nationwide Study.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education (September): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2021.1978210.

- Usher, Joe. 2023. “‘I Hate When We Learn off the Mountains and Rivers Because I Don’t Need to Know Where They All Are on a Blank Map?!’ Irish Pupils’ Attitudes Towards, and Preferred Methods of Learning, Primary Geography Education.” Irish Educational Studies (April): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2023.2196257.

- Waldron, Fionnuala, Susan Pike, Richard Greenwood, Cliona M. Murphy, Geraldine O’Connor, Anne Dolan, and Karen Kerr. 2009. Becoming a Teacher, Primary Student Teachers as Learners and Teachers of History, Geography and Science: An All-Ireland Study. Armagh: The Centre for Cross Border Studies.

- Waldron, Fionnuala, Susan Pike, Janet Varley, Colette Murphy, and Richard Greenwood. 2007. “Student Teachers’ Prior Experiences of History, Geography and Science: Initial Findings of an All-Ireland Survey.” Irish Educational Studies 26 (2): 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323310701296086.