ABSTRACT

According to Article 12 of the UNCRC, children have a legal right to have their views heard and acted upon as appropriate. In Ireland, this applies to local planning processes concerning children’s localities whereby legislation was specifically enacted to recognise children as a group who were entitled to participate in the local planning process. However, while provisions are being made at policy level, children’s participation in practice is extremely limited. Furthermore, recent research into the teaching of primary school geography in Ireland has found that didactic and text-book approaches are significant with teachers neglecting to teach about the local area and to use experiential learning methods such as fieldwork. Through a qualitative analysis of current research in primary geography education and children’s participation in the planning process, this research presents a conceptual framework which enables children to participate in the local area planning process in Ireland through primary school geography. This conceptual framework provides a systematic and coherent way of approaching children’s participation and the teaching of primary school geography. The key findings from this research centre around the positioning of schools and particularly the primary geography curriculum (PGC) to be the ‘space’ within which children’s participation can and should occur. Enabling children’s participation in planning processes to occur through the PGC serves to bridge the policy-practice gap pertaining to children’s participation, building their capacity to participate, and ensuring the broadest possible sample of the population are included. It also addresses the policy-practice gap in the teaching of geography by ensuring the teaching of lessons involving experiential methods focused on the local area. This conceptual framework sets out a stepped, progressional approach to enabling children to participate in local area planning decisions by carrying out geographical investigations of their localities.

Introduction

This research presents a conceptual framework which enables children to participate in the local area planning process in Ireland through primary school geography. Drawing on current research in primary geography education and children’s participation in the planning process in Ireland, the author makes a strong and unique argument for schools and particularly the primary geography curriculum to be the ‘space’ within which children’s participation can and should occur, thus bridging the policy-practice gap pertaining to children’s participation and also bridging the policy-practice gap in the teaching of geography in Irish primary schools.

This paper begins by providing a background to children’s participation in planning processes in Ireland and how geography is taught in Irish primary schools. Following this, an argument for the merging of children’s participation and primary geography education is put forward before presenting the conceptual framework for enabling children’s participation in planning processes through primary geography education.

Background

Children’s participation in local area planning processes in Ireland

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) established the right of children to participate in society (UN Citation1989). Under Article 12 of the UNCRC, also known as the ‘Participation Article’, children have the right to express their views and to have those views given due weight. Article 12 of the UNCRC has created a greater emphasis on listening to children’s voices and considering these in the planning and shaping of the built environment (David and Buchannan Citation2020; Chawla Citation2002). Article 12 goes on to state that ‘children’s views should be given due weight according to their age and maturity’ which this author argues is quite vague and ambiguous and also fails to acknowledge that age and maturity are not interlinked. ‘Competence as a citizen is not limited to adults, and neither is incompetence restricted to children’ (Theis Citation2010, 346). There has also been a shift towards acknowledging children as experts in and on their own lives (Clark Citation2004). While the UNCRC was significant in creating an impetus for children’s participation, this dovetailed with the more general democratisation of planning processes in the 1990s that emphasised more participatory approaches (Russell and Moore-Cherry Citation2013).

In response to these policy shifts, Irish planning legislation was specifically enacted to recognise children as a group who were entitled to participate in the local planning process, in particular the Planning and Development (Amended) Act 2010 (Russell and Moore-Cherry Citation2013)). Furthermore, under the Irish Local Area Planning Guidelines (LAPGs) (Department of Environment, Community and Local Government (DECLG) Citation2013), children have the right to be consulted in decisions made which affect them. It is indicated here that the views and opinions of children should shape the policies and objectives of Local Area Plans. The LAPGs state: ‘children, or groups or associations representing children, are entitled to make submissions or observations on local area plans’ (DECLG Citation2013, 26). While the LAPGs do not make it obligatory to consult children, they draw planners’ attention to the conception of children as a group of citizens in need of consideration for consultation. The current National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (DCYA Citation2015) was the first of its kind in Europe (Horgan Citation2017). It is underpinned by three goals, the first being: ‘Children will have a voice in matters which affect them and their views will be given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity’ (DCYA Citation2015, 6). Therefore, children in Ireland are now being recognised by planners as legitimate participants in planning processes; at least from a policy standpoint.

A range of children’s participation structures have been put in place at local and national levels such as the creation of the Dáil na nÓg (National Youth Assembly), and Comhairlí na nÓg (Local Youth Councils) in every county and city council (34 councils in total). However, McEvoy (Citation2010) found limited evidence of links between the Comhairlí na nÓg and planning processes. Here, only one of the 34 Comhairlí na nÓg having an ongoing formal link with the planning department of the local authority, while just four had a one-off form of input into the local county/city development plan (McEvoy Citation2010). Furthermore, it is important to note that associations such as youth councils have been widely criticised and described as ‘insider’ groups whereby ‘insider’ groups are ‘legitimate’, often ‘sub-elite’ groups, which are consulted on a regular basis by decision-makers and policy-makers (Ringholm, Nyseth, and Hanssen Citation2018). These participatory groups are not representative of all children and are already agreeable to ‘playing by the rules’ (Faulkner Citation2009, 13). It needs to be acknowledged that there is no homogenous ‘child’, no authentic voice of the child but rather multiple realities of children’s lives and many individual unique voices (Freeman and Aitken-Rose Citation2005). Indeed, evidence of consultation of children at individual levels or indeed from any group or association outside of Comhairlí na nÓg is also lacking (Russell and Moore-Cherry Citation2013). Therefore, despite policy provisions and legislation promulgating for their inclusion, in practice, children are predominantly marginalised from planning processes and there is a clear policy-practice gap between actual planning practices and the legislation and policy provisions that supposedly inform these practices in Ireland.

There are enormous benefits to enabling the participation of children in local planning processes (see ). However, it is also clear from the widely accepted barriers to children’s participation (see ) that clearer structures and frameworks are needed to enable children to more easily participate in local planning processes and to equip planners with the means to facilitate this. This research study therefore argues for schools and indeed the primary geography curriculum to be the ‘space’ within which children’s participation can and should occur. Here children can explore issues and opportunities in their localities through primary geography lessons and then present their ideas and opinions in planner-friendly formats of maps and written reports.

Table 1. Benefits of, and barriers to, children’s participation in planning processes.

Primary geography education in Ireland

The current Irish Primary Geography Curriculum (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) Citation1999) (henceforth referred to as the PGC) was lauded nationally and internationally as progressive and ambitious in recognising and promoting the children as active participants in constructing their own learning; connecting new content to their own experiences and what they already know, developing empathy with others, and developing senses of space and place of their locality and the wider world (Catling 2013; Usher Citation2020; Citation2021a). The core principles of the PGC advocate for experiential and enquiry-based approaches including a focus on the local area and children’s own experiences (Usher Citation2020; Citation2021b). Constructivist principles are evident throughout, with children being encouraged to work as geographers, carrying out local investigations and fieldwork to explore patterns and processes and develop key concepts of a sense of place and sense of space (NCCA Citation1999). Dewey’s (Citation1938) work and Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning are evident in the PGC (Usher Citation2021b). The PGC promotes critical thinking and the holistic development of children as learners in their own right as well as active members of their local communities and society at large (NCCA Citation1999).

Unfortunately, the pattern of failed implementation that has perpetuated throughout Irish educational reform continued here (Usher Citation2020; Usher and Dolan Citation2021). Usher’s (Citation2021b) large-scale research of how the PGC is taught found Irish primary teachers use of practical, hands-on experiential learning methods in their teaching of geography is limited and inconsistent. Almost 60% of Irish primary teachers self-reported as not doing any geographical fieldwork in their teaching of geography (Usher Citation2021b). Limited pedagogical approaches including rote-learning and textbook based teaching are widely evidenced (Usher Citation2023; INTO Citation2005). Furthermore, teachers are not devoting enough time to the local area with 75% of teachers teaching between 1 and 5 lessons per year on the locality and 9% of teachers teaching no lessons on the local area (Usher Citation2021b). Undertaking investigations in and on the local area is well-regarded as the cornerstone for successful geography teaching and learning (Catling Citation2015). Therefore, there is a need to address this policy-practice mismatch and for teachers to teach more content based on the locality of the school and provide more opportunities for experiential learning including fieldwork on the local area.

Thus, in light of the above from both a participation and education perspective, the following section will present the main argument and premise for this conceptual framework; i.e. that the participation of children in local area planning processes should be facilitated and enabled through primary geography education in school settings. By doing so, this research study argues that the aforementioned policy-practice mismatches could both be addressed simultaneously.

Children’s participation in local planning processes through geography education

As a way of addressing the aforementioned policy-practice gaps, this research study conceptualises the merging of primary geography education in the local area with the local area planning process; enabling children to participate in the local area planning process through investigating the local area and forming informed views on local issues and possible solutions.

Over the past twenty years, researchers and advocates in Europe have been calling on practitioners and policy-makers to achieve the institutionalisation of children’s participation within local planning practices and recommending for embedding this within school curricula ‘thus building capacity for active citizenship in children’ (Chawla Citation2002; Knowles-Yanez Citation2005, 9). However, the geography curriculum itself has never been highlighted as the specific optimal bedfellow for children’s participation in these instances. From a geography education perspective, Usher and Dolan (Citation2021), Beneker and Van der Schee (Citation2015) and Catling (Citation2005) argue that children should be able to use their geographical knowledge attained in school to help them become more autonomous decision-makers and active citizens. However, they do not specifically refer to children participating in local planning processes. Children are current and future residents, citizens and social actors of their localities; they have views on their localities now and in the future (Knowles-Yanez Citation2005; Percy-Smith Citation2010). They are the longest-term stakeholders in society (Badham Citation2002). Therefore, children should have the opportunity to shape their own futures and those of their communities. Wellens et al. (Citation2006) argue that geography is well-placed to play a pivotal role in social transformation and active citizenship, lending itself to participation. This research study also upholds the role of geography in enabling children to understand the world around them, both locally and globally, and to develop and apply critical thinking skills and problem-solving skills pertaining to real-life issues which impact themselves and their wider communities. ‘Geography, through concepts such as space, place, scale and interdependence, enables children to develop twenty-first-century skills and competencies, to analyse and form opinions about real-world issues, and to understand and challenge how the world works’ (Usher and Dolan Citation2021, 8). Weiss (Citation2017) advocates for the investigation and examination of planning decisions within geography teaching. Indeed, in their argument for the use of planning in secondary school geography textbooks, Maier and Budke (Citation2016, 9) assert that ‘teaching the subject of planning in geography lessons provides a possibility to reach the goals of geography education; i.e. an understanding of central social, environmental and spatial issues and to ensure participation in a democratic society’. Weiss (Citation2017) upholds that connecting with planners and the planning process creates awareness of professions associated with geography and how geography is a relevant living subject. Thus, use of local planning issues and experiential approaches are conducive to primary geography. However, it is worth noting that none of the above researchers and authors argue for the inclusion and indeed participation of children in these planning decisions but more for the exploration of planning processes and decisions after they have been taken as a way of contextualising learning.

The PGC in Ireland refers to the knowledge and skills children will develop through investigations in and on their local environment (NCCA Citation1999). It recognises children as citizens of, and experts on, their local communities. This aligns with the need for planners to see children as experts in their own lives and as active participants rather than a vulnerable group in need of protection (Clark and Percy-Smith Citation2006). The PGC affords children the opportunity to engage with people from the local community and to express their ideas and opinions (NCCA Citation1999). The PGC purports that children from age of eight upwards should be enabled to identify, discuss and investigate a local issue and to suggest possible solutions and to participate in the resolution process where possible (NCCA Citation1999). Suggested examples of issues that children can investigate include litter, pollution, the need for new roads, bicycle lanes and housing developments. Children’s localities are part of their everyday lives (Catling and Willy Citation2018). Children’s everyday geographies or ‘ethno-geographies’ are very important in that ‘through interacting in a myriad of daily-life activities, children already think geographically’ (Martin Citation2008, 369). Catling and Willy (Citation2018) maintain that investigations of the local area through experiential activities such as map making, fieldwork, collaborative group work and hands-on learning increases children’s academic achievement, creates stronger links to the local community, enhances their appreciation of the local environment and develops them as active citizens. These arguments are further upheld both nationally and internationally (Dolan Citation2020; Halocha Citation2012). Additionally, use of the local area is well-emphasised in the PGC (NCCA Citation1999). Throughout the history of curricular development in Ireland, the PGC has always referred to the local environment as the main resource and context for learning (Usher Citation2020). The use of the local area goes beyond identifying a range of features, services, changes and connections, contextualising learning and providing a space for experiential fieldwork to be carried out. It also aids the development children’s sense of belonging, local community identity, and empowers children’s voice and involvement (Dolan Citation2020).

While the educational benefits of exploring local area planning in primary geography are widely accepted, researchers also agree that children possess certain competencies that the planning process should incorporate (Cele Citation2006; Cele and Van der Burgt Citation2015). Thus, a foundational argument in this research study is that without an active citizenship component, geography education is merely a school simulation activity with preparation for action in the real world at the very least questionable.

Conceptual framework for enabling the participation of children in local area planning decision-making processes through primary geography education

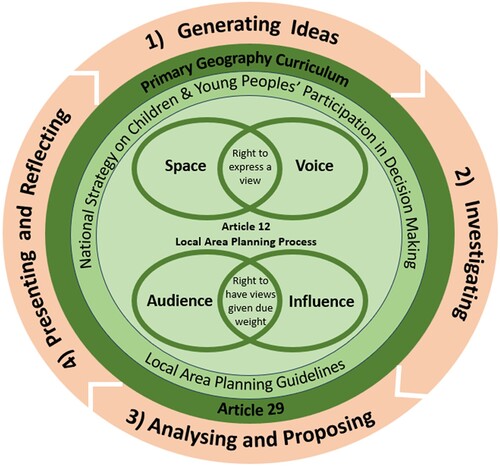

The conceptual framework presented in this research study (see ) is underpinned and informed by a variety of diverse sources, drawing from the work of educational theorists such as Dewey and Kolb. It includes Lundy’s (Citation2007) model for children’s participation and is underpinned by various articles from the UNCRC, national policy and guidelines in Ireland pertaining to children’s participation in decision making and local area planning. Finally, and significantly, it is embedded within and inspired by, the PGC.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for enabling the participation of children in local area planning decision-making processes through primary geography education in Ireland.

The following section will explain each element of the conceptual framework beginning with the outer ring and working towards the centre.

Outer ring: experiential learning and geographical enquiry

The outer ring of the conceptual framework presented in this research study demonstrates the merging of frameworks for geographical enquiry (Catling and Willy Citation2018; Roberts Citation2003) and Kolb’s (Citation1984) cycle of experiential learning to form four separate yet interdependent and indivisible elements: (1) Generating Ideas; (2) Investigating; (3) Analysing and Proposing; and (4) Presenting and Reflecting (see ). Enquiry-based learning in geography education comprises a child-centred, experiential approach whereby children are active in their learning and participate in the leading of the investigation through posing questions and generating ideas before actively creating and/or collecting data to help develop their understanding before devising findings, identifying solutions to issues and taking action where appropriate and reflecting on the process and learning (Dolan Citation2020; Roberts Citation2003). Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning promotes critical thinking, problem-solving and enquiry, and stresses the importance of connecting to children’s real-world experiences; all key facets of effective geography education. An example of this is the approaches put forward by Usher and Dolan (Citation2021) on teaching about Covid19 through primary school geography education as an authentic context and lived experience of children. Ives and Obenchain (Citation2006) outline three fundamental elements of experiential education comprising: child-centred approaches, connections to the real world, and opportunities for reflection. These three elements are key to effective geography education as outlined by the Irish PGC (NCCA Citation1999) and the wider research literature (Dolan Citation2020; Usher Citation2021a; Citation2021b; Wellens et al. Citation2006). Moreover, Ives-Dewey (Citation2009, 167) maintains that ‘local community-based planning projects provide rich opportunities for experiential learning activities in geography’, thus reifying the very argument of this research study. However, it is important to note that, similarly to Weiss (Citation2017), Maier and Budke (Citation2016) and Catling (Citation2005), Ives-Dewey (Citation2009) sees the topic of local planning as an authentic context and subject to be studied, highlighting to children the relevance of geography to the real-world. There is no argument put forward by these authors for the participation of children in planning decisions.

The outer ring depicts the four stages of learning and engagement: (1) Generating Ideas; (2) Investigating; (3) Analysing and Proposing; and (4) Presenting and Reflecting (see ). It is envisage the primary geography education lessons and learning activities on the local area would follow these stages, beginning with the Generating Ideas stage where the children speculate and generate investigable questions in relation to their local area, identifying possible issues (such as lack of cycle lanes or footpaths, poor public space provision, lack of specific bins). Lessons would then progress to the second stage Investigation, with children carrying out investigations in the form of interviews, fieldwork and observations. Here they would use a range of resources to both create and/or collect data to be used as evidence for their investigations into local issues. During stage three Analysing and Proposing, the children analyse and interpret the data pertaining to their investigations, thus reflecting on and modifying their ideas and concepts and developing specific recommendations and solutions for local issues. They would also prepare their findings and recommendations. The final stage of the conceptual framework is Presenting and Reflecting. Here the children will take action by presenting and submitting their findings and recommendations via their own Local Area Plan (which includes their own maps and report of recommendations) to the designated audience of the local authority and planners. During this stage, the planners would provide feedback on the extent to which the children’s voices were heard and the extent to which their findings and recommendations influenced the local planning decisions that had been made. The children would then reflect on their learning and the participation process.

Second ring: geography curriculum and Article 29

The next ring comprises the PGC which itself provides that children in 3rd Class to 6th Class (i.e. from age of eight to twelve) should be enabled to identify, discuss and investigate a local issue and to suggest possible solutions and to participate in the resolution process where possible (NCCA Citation1999). The children would attain geographical knowledge, skills and understanding within the context of their local investigations (core to the Irish PGC) which would then enable them to form a view on their locality and express this view (i.e. voice) with regard to local area planning. Article 29 is also included in this circle as, not only does it reflect the learning approaches advocated for by the PGC, but a foundational pillar of the framework itself is the right to an education that encourages responsible citizenship.

Third ring: Irish policy for including children’s participation in local area planning processes

The third circle pertains to two significant Irish policies on the inclusion of children in local area decision-making processes i.e. the LAPGs (DCLG Citation2013) and the National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (DCYA Citation2015) (see ). This research study aims to bridge the policy-practice gap in this regard.

Inner circle: Lundy’s model of child participation

Lundy’s model of child participation is included in the inner circle of this conceptual framework (see ). This model is centred on the premise that all human rights are inseparable, interdependent and interconnected, meaning that the ‘individual provisions of the UNCRC can only be understood when they are read and interpreted in conjunction with the other rights protected in the Convention’ (Lundy Citation2007, 932). Here, Lundy conceptualises Article 12 as being underpinned and supported by Article 2 (non-discrimination); Article 3 (best interests); Article 5 (right to guidance); Article 13 (right to seek, receive and impart information); and Article 19 (protection from abuse). Lundy’s model focuses on four elements of Article 12: Space, Voice, Audience and Influence. These elements were included in the conceptual framework and will be discussed below in this regard.

Space: children must be given the opportunity to express a view

Lundy (Citation2007) purports that a necessity for meaningful and true participation of children in decision making is the provision of opportunities for enabling them to get involved; i.e. a space in which children are encouraged to express their views. There is an obligation on those in power to take proactive steps to encourage children to express their views and to actively seek their input rather than passively receiving such input wherever it happens to occur (Lundy Citation2007). Therefore, in the context of this research study, the children are provided with a safe space in which to form and express their views (i.e. their own school and class environment) with the geography curriculum itself being the mechanism and opportunity provided to enable this participation to happen. Percy-Smith (Citation2010) criticises the use of schools and other formal spaces for the provision of participation opportunities for children. He argues that children should be afforded their own informal means of participation and engagement. However, Ringholm, Nyseth, and Hanssen (Citation2018, 9) acknowledge that such informal procedures lack accountability and clarity. Indeed, informal spaces and participatory methods are also more difficult and less likely to be captured by planners and replicated across planning processes. Furthermore, the number of children of primary school-going age not attending registered primary schools in Ireland in 2019 was less than 1% (Bowers Citation2019) making it arguably the best space for accessing the broadest sample of the population, building capacity and enabling children’s participation. Russell and Moore-Cherry (Citation2013) and Freeman and Aitken-Rose (Citation2005) found that where planners did seek children’s views on local planning matters, they preferred to use local schools rather than formal youth councils as schools were often situated more locally with regard to the specific area being planned for. The primary school and class should be designated as the space for participation as it is a space with which the children are most familiar and of which they feel a sense of ownership, and so would help alleviate the power dynamics. Lundy (Citation2007) also alludes to the fact that Article 12 is a right and not a duty and therefore children’s right to not participate should also be respected. This is reflected in the conceptual framework whereby all children within the classroom context would learn about the local area and carry out local geographical investigations and enquiries in line with normal curriculum practice, but children are not obliged to make a submission to the local planning authority.

(2) Voice: children must be facilitated to express their views

This research study criticises the wording of Article 12 which advocates for ‘due weight according to … age and maturity’ (UN Citation2010, 15) as it fails to acknowledge that age and maturity are not interlinked. Additionally, much research takes a capacity-building approach to enabling children to have their say by familiarising them with the topic or issues, enabling them to develop their own views on these issues and to assist them in sharing these views (Lundy and McEvoy Citation2009). Article 5 of the UNCRC provides children with the right to receive guidance and direction from adults in the exercise of their rights. The conceptual framework presented in the current research study positions teachers in this very role as facilitators of children’s learning and voicing their views on the local area. Moreover, Article 29 provides children with the right to an education that encourages responsible citizenship. Here, teachers as experts in teaching, would differentiate their support in facilitating children in sharing their voice in accordance with their abilities.

(3) Audience: the view must be listened to

Article 12 requires that children have the right to have their voices listened to (and not just heard) by those in charge of the decision-making process (Lundy Citation2007). The right to an audience here is crucial in that this provides children with a guaranteed opportunity to express their views to an identifiable body with the responsibility to listen. This conceptual framework identifies a local planning authority as a willing audience and distinguishable body whose responsibility is to listen. Here, children are facilitated to express their views in ‘planner-friendly’ ways via their own maps of the local area and setting out clear objectives for specific aspects of the local area so as to reach their audience effectively. This information would then be sent to or presented to the local planning authority by the class. The local planning authority has the decision-making power in this instance and so is obliged to listen. Activities such as map-making, report writing and presenting are all elements of the PGC and therefore, this would not require additional work or time outside of the current curricular expectations.

(4) Influence: the view must be acted upon as appropriate

As the right of children having their views given due weight is to be provided ‘in accordance with their age and capacity’, there is a danger that adults who act as gatekeepers to Article 12 might have limited perceptions of children’s capabilities in this regard. Therefore, Lundy (Citation2007) argues that Articles 3 and 5 of the UNCRC are crucial in the realisation of Article 12, particularly in the affordance of giving children’s views due weight and appropriate influence. Article 3 provides that children’s best interests be a primary consideration in all decisions affecting them. Article 5 obliges adults to provide children with guidance and direction in line with their evolving capacities. This research study argues that by situating the participation to occur within the educational PGC context, the class teacher has a realistic understanding of the children’s capabilities and also has the expertise to develop and enhance their capabilities in this regard. A provision within planning guidelines and policy also needs to be made to ensure that children are informed of how their views were taken into account and the extent to which this was done. This could be done via videos, in person presentations or additional documentation. Therefore, this framework ensures that children’s views are taken seriously and given due consideration by the local planning authority, while the participating children should receive feedback on how and to what extent their views influenced decisions (during the Presenting and Reflecting stage).

Lundy’s model also underpins the National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making 2015–2020 which uses the model to form a checklist to ensure appropriate and effective participation (DCYA Citation2015). Finally, just as Lundy (Citation2007) argues that Article 12 can only be fully understood in light of other relevant UNCRC provisions; this research study argues that children’s participation in local decision making cannot be fully realised without the merging of this right to participation with their education, particularly learning about the local area and how people’s decisions and actions have direct impacts on the natural and built environment. Therefore, Article 29 (the right to an education that encourages responsible citizenship) is also crucial to the conceptual framework for this study as it meets the curricular requirements of the PGC while simultaneously building children’s capacities, equipping them with the knowledge and skills to form their own views and opinions and thereby enabling them to participate in local planning decision-making processes.

Considerations for the practical application of this conceptual framework

While policies such as the UN CRC (UN, Citation1989), National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (DCYA Citation2015), LAPGs (DCLG Citation2013) and the Planning and Development (Amended) Act, (2010) maintain that children should be consulted on all matters which affect them, and participate in the local area planning processes, there is clearly a misalignment of policy and practice. This research argues for the provision of specific guidance for planners to enable children’s participation to be fully realised. Lack of expertise as well as a lack of resources and time are barriers to children’s participation which have been clearly identified in the literature (Freeman and Vass Citation2010; Freeman, Nairn, and Sligo Citation2003; Hanssen Citation2019; Ringholm, Nyseth, and Hanssen Citation2018; Russell and Moore-Cherry Citation2013). Moreover, planners’ and policy-makers’ adultist views and limited perceptions of children’s capabilities are also major barriers inhibiting children’s participation (Agyei, Gyorgy, and Vinberg Citation2017; Driskell Citation2002; Percy-Smith Citation2010; Russell and Moore-Cherry Citation2013). Therefore, a key recommendation from this research study is that guidelines be created for planners with clear examples and specific identification of the PGC as an appropriate means for ensuring children’s participation in local area planning processes. Moreover, primary schools should be explicitly identified as recommended spaces in which true democratic participation can be achieved in line with the aims and objectives set out in national strategies and policies (DCLG Citation2013; DCYA Citation2015). Schools offer the broadest sample of the population, thus mitigating against representational biases (Ringholm, Nyseth, and Hanssen Citation2018; Faulkner Citation2009; Tisdall, Davis, and Gallagher Citation2008). Consultation should occur in schools and the children’s own classrooms themselves as these spaces are owned more by the children than by the visiting town planners, thus assuaging power dynamics. Timeframes should be clearly defined and be considerate of school academic calendar year to allow sufficient time for consultation within the statutory timeframe of planning and public consultation. Planning guidelines should provide exemplars of children’s contributions to educate planners and the broader community on the capacities and capabilities of children.

Finally, the provision in the LAPGs that ‘children, or groups or associations representing children, are entitled to make submissions or observations on local area plans’ (DECLG Citation2013, 26) should be removed from any guidelines and policies. Allowing for groups or associations representing children to make submissions on their behalf can be viewed as giving planners a ‘get-out clause’ and dissuades them from pursuing real participation and truly listening to children. The idea that children’s lived experiences and unique perspectives can be represented by certain designated adults upholds the idea of children as one homogenous group and whose interests can be represented by a few ‘authentic’ adults. Therefore, this provision needs to be omitted and children must be recognised as individual citizens with their own unique lived experiences of places (Freeman and Aitken-Rose Citation2005; Martin Citation2008).

Conclusion

Drawing on current research in primary geography education and children’s participation in the local area planning process, this research study has made a strong argument for primary geography education to be the ‘space’ within which children’s participation can and should occur, thus bridging the policy-practice gap pertaining to children’s participation and also bridging the policy-practice gap in the teaching of geography. Children are more motivated to engage in a problem or issue that affects them, their area, or people and places familiar to them (Usher and Dolan Citation2021). Exploring real-world, everyday issues, events and problems is more exciting, engaging and memorable for children than if learning is confined to abstract issues in the classroom. Here, children can see and experience the relevance and significance of geography to their lives and the wider world while developing investigation skills, rich content knowledge and conceptual understanding within a real-world purposeful context. They can then apply this new knowledge and skills to voice their informed opinions on, and engage in, local area planning processes, thus realising their rights within the participatory legislation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joe Usher

Joe Usher is an assistant professor in Primary Geography education and Social, Environmental and Scientific Education (SESE) at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. He works in the area of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and Professional Learning.

References

- Agyei, A., R. Gyorgy, and A. Vinberg. 2017. Children’s Participation in Creating the Local Action Plan for Oulunkyla English Kindergarten. Helsinki: Metropolia University of Applied Sciences.

- Badham, B. 2002. “Faith in Young People in Regeneration.” Childright 190: 10–12.

- Beneker, T., and J. Van Der Schee. 2015. “Future geographies and geography education.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (4): 287–293.

- Bowers, S. 2019. “Stress and anxiety factors in homeschool numbers rising.” Irish Times, December 9.. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/stress-and-anxiety-factors-in-homeschool-numbers-rising-1.4108700.

- Catling, S. 2005. “Children’s Personal Geographies and the English Primary School Geography Curriculum.” Children’s Geographies 3 (3): 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280500353019.

- Catling, S. 2015. Debates in Primary Geography. London: Routledge.

- Catling, S., and T. Willy. 2018. Understanding and Teaching Primary Geography. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Cele, S. 2006. Communicating Place: Methods for Understanding Children’s Experience of Place. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Cele, S., and D. Van der Burgt. 2015. “Participation, Consultation, Confusion: Professionals’ Understandings of Children’s Participation in Physical Planning.” Children’s Geographies 13 (1): 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.827873.

- Chawla, L. 2002. “Insight, Creativity and Thoughts on the Environment: Integrating Children and Youth Into Human Settlement Development.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (2): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780201400202.

- Clark, A. 2004. “Listening to Children.” In Supporting Children's Learning in the Early Years, edited by L. Miller and J. Devereux. London: David Fulton/Open University.

- Clark, A., and B. Percy-Smith. 2006. “Beyond Consultation: Participatory Practices in Everyday Spaces.” Children, Youth and Environments 16 (2): 1–8.

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA). 2015. National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making 2015-2020. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Department of Environment, Community and Local Government (DECLG). 2013. Local Area Plans: Guidelines for Planning Authorities. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Derr, V. 2015. “Integrating Community Engagement and Children’s Voice into Design and Planning Education.” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 10 (1): 1–15.

- Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Collier Books.

- Dolan, A. M. 2020. Powerful Primary Geography: A Toolkit for 21st Century Learning. London: Routledge.

- Driskell, D. 2002. Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth: A Manual for Participation. London: Routledge.

- Faulkner, K. M. 2009. “Presentation and Representation: youth participation in ongoing public decision-making projects.” Presentation and Participation 16 (1): 89–104.

- Frank, K. I. 2006. “The Potential of Youth Participation in Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 20 (4): 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205286016.

- Freeman, C., and E. Aitken-Rose. 2005. “Future Shapers: Children, Young People and Planning in New Zealand Local Government.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 23 (2): 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0433.

- Freeman, C., K. Nairn, and J. Sligo. 2003. “Professionalising’ Participation: from rhetoric to practice.” Children’s Geographies 1 (1): 53–70.

- Freeman, C., and E. Vass. 2010. “Planning, Maps and Children’s Lives: A Cautionary Tale.” Planning Theory and Practice 11 (1): 65–88.

- Halocha, J. 2012. The Primary Teachers’ Guide to Geography. Witney: Scholastic.

- Hanssen, G. S. 2019. “The Social Sustainable City: How to Involve Children in Designing and Planning for Urban Childhoods?” Urban Planning 4 (1): 53–66. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i1.1719.

- Head, B. W. 2011. “Why not ask Them? Mapping and Promoting Youth Participation.” Children and Youth Services Review 33 (1): 514–547.

- Horgan, D. 2017. “Consultations with Children and Young People and Their Impact on Policy in Ireland.” Social Inclusion 5 (3): 104–112.

- Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO). 2005. The Primary School Curriculum: INTO survey. Dublin: INTO.

- Ives-Dewey, D. 2009. “Teaching Experiential Learning in Geography: Lessons from Planning.” Journal of Geography 107 (4-5): 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340802511348.

- Ives, B., and K. Obenchain. 2006. “Experiential Education in the Classroom and Academic Outcomes: For Those who Want it all.” Journal of Experiential Education 29 (1): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590602900106.

- Knowles-Yanez, K. L. 2005. “Children’s Participation in Planning Processes.” Journal of Planning Literarure 20 (1): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205277032.

- Kolb, D. A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience As The Source Of Learning And Development. London: Prentice-Hall.

- Kränzl-Nagl, R., and U. Zartler. 2010. “Children’s Participation in School and Community: European Perspectives.” In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation, edited by B. Percy- Smith and N. Thomas, 164–173. London: Routledge.

- Landsdown. 2010. “The Realisation of Children’s Participation.” In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation. London and New York: Routledge, edited by B. Percy-Smith and N. Thomas, 11–32. London: Routledge.

- Lundy, L. 2007. “‘Voice’ is not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” British Educational Research Journal 33 (6): 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033.

- Lundy, L., and L. Mcevoy. 2009. “Developing Outcomes for Educational Services: A Children’s Rights-Based Approach.” Effective Education 1 (1): 43–60.

- Maier, V., and A. Budke. 2016. “The Use of Planning in English and German (NRW) Geography School Textbooks.” Review of International Geographical Education Online 6 (1): 8–31.

- Martin, F. 2008. “Ethnogeography: Towards Liberatory Geography Education.” Children’s Geographies 6 (4): 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280802338130.

- McEvoy, O. 2010. Evaluation Report: Comhairle na nÓg Development Fund 2009– 2010. Dublin: Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Geography. Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Palmy David, N., and A. Buchanan. 2020. “Planning Our Future: Institutionalizing Youth Participation in Local Government Planning Efforts.” Planning Theory & Practice 21 (1): 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1696981.

- Percy-Smith, B. 2010. “Councils, Consultations and Communities: Rethinking the Spaces for Children and Young People’s Participation.” Children’s Geographies 8 (2): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733281003691368.

- Ringholm, T., T. Nyseth, and G. S. Hanssen. 2018. “Participation According to the law?: The Research-Based Knowledge on Citizen Participation in Norwegian Municipal Planning.” European Journal of Spatial Development 67: 1–20.

- Roberts, M. 2003. Learning Through Enquiry: Making Sense of Geography in the Key Stage 3 Classroom. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Russell, P., and N. Moore-Cherry. 2013. “Planning for Their Future: Children, Participation and the Planning Process.” AESOP-ACSP Planning for Resilient Cities and Regions 1 (1): 1–14.

- Theis, J. 2010. “Children as Active Citizens.” In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation, edited by B. Percy-Smith and N. Thomas, 343–356. London: Routledge.

- Tisdall, E. K. M., J. Davis, and M. Gallagher. 2008. “Reflecting on Children and Young People’s Participation in the UK.” International Journal of Children’s Rights 16 (3): 343–354.

- UN. 1989. "Convention on the rights of the child." Treaty no. 27531. United Nations Treaty Series, 1577, pp. 3–178. Accessed July 3, 2023. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf.

- United Nations (UN). 2010. United Nations Conventions of the Rights of the Child. Dublin: Children’s Rights Alliance.

- Usher, J. 2020. “Is Geography Lost? Curriculum Policy Analysis: Finding a Place for Geography Within a Changing Primary School Curriculum in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 39 (4): 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1697945.

- Usher, J. 2021a. “Africa in Irish Primary Geography Textbooks: Developing and Applying a Framework to Investigate the Potential of Irish Primary Geography Textbooks in Supporting Critical Multicultural Education.” Irish Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1910975.

- Usher, J. 2021b. “How is Geography Taught in Irish Primary Schools? A Large Scale Nationwide Study.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2021.1978210.

- Usher, J. 2023. “I Hate When we Learn off the Mountains and Rivers Because I Don’t Need to Know Where They all are on a Blank map?!’ Irish Pupils’ Attitudes Towards, and Preferred Methods of Learning, Primary Geography Education.” Irish Educational Studies 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2023.2196257.

- Usher, J., and A. M. Dolan. 2021. “Covid-19: Teaching Primary Geography in an Authentic Context Related to the Lived Experiences of Learners.” Irish Educational Studies ‘COVID-19 and Education: Positioning the pandemic; facing the future’ 40 (2): 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916555.

- Weiss, G. 2017. “Problem-oriented Learning in Geography Education: Construction of Motivating Problems.” Journal of Geography 116 (5): 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2016.1272622.

- Wellens, J., A. Berardi, B. Chalkley, B. Chambers, R. Healey, J. Monk, and J. Vender. 2006. “Teaching Geography for Social Transformation.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30 (1): 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260500499717.