ABSTRACT

Individuals with anxiety disorders were traced back to have onset before aged 5 years. Early intervention is important to target preschool and primary school children. The objective of this 14-week fieldwork was to explore how we can support young children’s well-being in schools. The following research questions were identified to investigate this topic: 1. Did a 14-week ‘build-to-play’ approach lead to reports of reduced anxiety as reported by teachers, parents, and in observation reports from the researcher among a sample of 12 children (aged 4–6 years) who experience anxiety (n = 9) or anxiety and autism (n = 3)? 2. Throughout the 14-week approach, interviews with parents (n = 12) and teachers (n = 6), what were the co-construction of strategies to reduce anxiety? Twelve case studies in two primary schools in Dublin were conducted. We proposed to bring the approach to school settings as COVID-19 has accelerated the good work that children and parents may benefit more from the non-clinical settings. The theoretical frameworks were universal design for learning and bio-ecological model to design this ‘Build-to-Play’ approach as inclusive and developmentally appropriate for young children. The key findings related to education included outcomes of a reduction in childhood anxiety, improved social communication skills and executive functioning. More importantly, a collaborative understanding of what anxiety was and how to cope with it was established. For example, for children who had any risk factors of anxiety or additional needs such as autism (n = 8), a more intensive approach than the standard 14-week was needed to have better outcomes. Conceivably, this research would make an impactful contribution as change makers to educational practice, policy and theory. Keywords: anxiety, autism, play, inclusion, education.

Introduction

As educators, we understand that as long as a child is anxious, no real learning can happen (Goleman Citation1995). As educators, we are continually seeking new ways in which to facilitate creative responses from learners, and also to more fully realise our capacities to work with others in collaborative and sustainable ways (Riddle, Bright, and Heffernan Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic impacted children and increased the experiences of prolonged social isolation for many.

A review of the salient research and practice identified a gap in the attention provided to the support of young childrens’ well-being in school settings. In particular, there were limited group approaches that were targeted towards preschool and primary school children that demonstrated the outcome of anxiety reduction for children with co-occurrence of autism. In particular, these approaches were not play-based and were not inclusive enough to provide support accessible to a wide range of needs in this specific population. From our review of 12 identified case studies, the profiles of children with anxiety could be very diverse. Based on our systematic literature review (Authors Citation2023b) of play-based group interventions for children aged 2–12 years that effectively reduced anxiety levels, we developed an innovative programme using evidence-based strategies, including autism-friendly strategies. Among 7,300 studies, there were 34 out of 44 empirical studies that demonstrated outcome of anxiety reduction in children with both anxiety and autism aged 4–12 years. The majority of these studies used the cognitive behaviour therapy approach (n = 28), some used play-based approaches (n = 5) and one used Lego-based therapy that partially reduced the level of anxiety (Nguyen Citation2017).

Study rationale

The preschool stage, for children aged 4–6 years, in most countries, or called the infants classes which were incorporated in primary schools in Ireland, presented an important opportunity for the prevention of or early intervention for anxiety in children. Because a study reported that pre-schoolers who showed a tendency to do or think about the same things over and over were very likely to have a high insistence on sameness in middle childhood as well as elevated current and/or future anxiety symptoms (Baribeau et al. Citation2020).

Furthermore, limitations of previous research included few studies reporting on anxiety in pre-school (Hayashida et al. Citation2010). Few studies have examined the precursors or risk factors of anxiety symptoms in children and rates of sub-clinical anxiety symptoms in children with autism. Vasa et al. (Citation2013) reported that about 20% of preschool children (<6 years) and 9% of early elementary school children (6–9 years) with autism had sub-clinical levels of anxiety. Sub-clinical or sub-threshold symptoms were important because they reflect a potentially evolving anxiety disorder or a previous anxiety disorder that has been partially remitted.

Identifying sub-clinical anxiety is also critical for prevention and intervention (Axline Citation1969). The majority of the children with clinically elevated anxiety symptoms aged 8–11 followed a trajectory in which moderate preschool anxiety gradually increased over time (Baribeau et al. Citation2020). Given the high and impairing rate of anxiety in this autism population, prevention studies recruiting pre-school aged or early-school aged children are needed. The rationale for a constructive play approach includes children, despite their signs of anxiety and autism experience, like all children, need to be wanted, understood, respected, and accepted as human beings worthy of dignity (Axline Citation1950). Approaches using constructive play are appropriate for children with additional needs since it is free from the language barrier problem. Toys and play are relatively universal and not restricted by children’s verbal language abilities. It has been found that children can express their experiences and emotions more freely through play than by using language (Goh et al. Citation2011). Taking from the recreational activity groups which effectively reduced anxiety in aged 9–16 years children with autism (Goh et al. Citation2011; Sung et al. Citation2011), playing something they enjoyed as a group was beneficial., which was also echoed by the junior and senior infant classes of this current 14-week study. In addition, children with anxiety tended to avoid new activities (Blaustein & Kinniburgh, Citation2018).

The advantages of group intervention included addressing long waitlists and maximising resources. In addition, many group members felt less isolated as they began to recognise the universality of their experiences (Reaven Citation2009). Furthermore, participation in group therapy motivated less interested participants, promoted interpersonal skill development, provided an opportunity for peer modelling, and offered a safe space for the practice of new skills within a naturalistic environment (Christner et al. Citation2007). The group intervention format was described as helping to create a supportive and cohesive community among the participants and providing opportunities to learn adaptive strategies for coping and problem-solving (McLachlan, Fleer, and Edwards Citation2018).

On the other hand, the group format had some disadvantages. Individual attention was limited, inappropriate behaviours might be displayed and modelled by group members, and inaccurate information and perspectives could be perpetuated by well-meaning group members. Because of these, individual attention and the concepts of Individualised Education Programs (Blackwell and Rossetti Citation2014) should be stressed in this group approach.

The rationale for parental involvement included parents are key in the management of young children with mental well-being issues (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2007).

The rationale for an inclusive education framework and a bio-ecological model

In acknowledging the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (4: Quality Education; 10: Reducing Inequalities), the current research was conceptualised and operationalised within an inclusive framework. Such an approach can meaningfully includie children with anxiety or with co-morbid autism. Underpinning this approach was the influence of Universal Design for Learning (Rose and Meyer Citation2002) – e.g. always giving the participants options based on their preferences. The research was also conceptualised from the bie-ecological perspective advanced by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation1998), in that attention was directed towards the study participants and their ‘ecological context’ (e.g. parents, peers, teachers).

The theoretical frameworks that guided the current study were Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation1998), and the inclusive Universal Design for Learning educational approach first advanced by Rose and Meyer (Citation2002). These two theories formed an overarching framework for the new school-based approach that included children, parents, and teachers with different levels of ability and/or disability. Taken together, the current research highlights the utility of a multidisciplinary perspective to valuing diversity in both theoretical models of education and methodology in educational research. The research presented here was drawn from a larger study that involved interventions of more than 14 weeks and other components such as whole-class storybook reading and discussion to facilitate coping of anxiety and raising awareness of the anxiety conditions.

Materials and methods

To address the two research questions, 14-week case studies in two primary schools in Dublin city, Ireland, were conducted. The project lasted for two school years and started after the COVID-19 pandemic, in May 2022, and was completed in June, 2023. Therefore, the participating children did not necessarily begin their participation at the beginning of the school term. A bespoke ‘build-to-play’ approach that was influenced by UDL and Bronfenbrenner was designed for this research.

The first author (a qualified speech and language therapist, play therapist, and counsellor) delivered the ‘build-to-play’ approach in the schools. Sessions were delivered either before or after school, based on a UDL approach that sought the input of the school management regarding what would be feasible and best for the participants.

The concept of ‘participation in learning’ in the interviews was borrowed from UDL thinking. For the teachers, it meant to what extent the child was learning at school. To the parents, it meant to what extend the child was learning at home and outside.

The ratio of adults to children in the play-sessions was proposed to be 1:2–1:4. This made a difference because it was more intensive with four children in the same group, while it was still within the recommended ration of 1:5 as recommended in the literature (Authors Citation2023b) for children with both anxiety and autism. More interaction opportunity was observed and still gave the children individual attention. If the adult to child ratio was 1:1, one more peer from the child’s class was nominated by the class teacher. With more peer interactions, this design worked well to support children’s well-being.

The research design for the study was as follows, it was proposed to be one study with two components:

Component One: ‘Build-to-PlayTM’ children groups explored whether a 14-week ‘build-to-play’ approach would lead to reports of reduced anxiety among a sample of 12 children (aged 4–6 years) who experience anxiety (n = 9) or anxiety and autism (n = 3), as reported by teachers, parents, and observation reports from the researcher.

phase 1 (Dates 11May 2022 to 29June 2022)−8 sessions pilot,

phase 2 (Dates 11May 2022 to 7May 2023)−14 sessions,

phase 3 (Dates 11May 2022 to 20June 2023) 20–33 sessions intensive intervention.

Component Two: Parental and teacher involvement.

RQ2. Throughout study 1, interviews with parents (n = 12) and teachers (n = 6), what were the co-construction of strategies that are supporting RQ1 and RQ2 to reduce anxiety?

Phase 1 (Dates 4May 2022 to 7May 2023)- research instruments of interviews, SDQ and PAS

Phase 2 (Dates 4May 2022 to 7May 2023)- co-construction of strategies to support children with anxiety, summarized in a resource pack for teachers and parents respectively.

Phase 3 (Dates 11May 2022 to 20June 2023)-baseline research instruments of interviews, SDQ and PAS.

For both of the research questions, and prior to the first session, a pre-test was conducted. This included interviews with the parents and teachers, administration of two instruments to confirm elevated level of emotional difficulties, types and elevated level of anxiety (The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ: Goodman Citation2001)) and The Preschool Anxiety Scale (PAS: Stone, Janssens, and Vermulst Citation2015) After the final session (i.e. session 14), post-test interviews were conducted with parents and teachers so as to solicit feedback. Two instruments were administered to record any change in the level of emotional difficulties, types and elevated level of anxiety. Analysis of play and verbal / non-verbal themes throughout all sessions were recorded for analysis using Clarke, Braun, and Hayfield (Citation2015)’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis.

Research instrument

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ: Goodman Citation2001) and The Preschool Anxiety Scale (PAS: Stone, Janssens, and Vermulst Citation2015) were administered. There were interviews for the 12 children’s parents and teachers (before and after the children’s 14-week groups).

The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ was a brief behavioural screening questionnaire that can be completed in 5 min by parents or teachers of children aged 4–17 years (Goodman Citation2001). The SDQ consists of five domains: emotions, behaviour, concentration, peer interaction, and prosocial skills. The SDQ can be used in clinical assessment, research and evaluation, and screening. There is a large international literature available concerning the instrument’s psychometric properties and general utility. Reliability is generally satisfactory, whether judged by internal consistency (mean Cronbach α: = 0.73), cross-informant correlation (mean r = 0.34), or test-re-test stability after 4–6 months (mean r = 0.62) (Essau, Muris, and Ederer Citation2002). SDQ scores above the 90th percentile are predictive of a substantially raised probability of independently diagnosed psychiatric disorders (mean odds ratio: 15.7 for parent scales, 15.2 for teacher scales, 6.2 for youth scales). Furthermore, for the aged 4–7 years population, Clarke, Hill, and Charman (Citation2017)have reported that previous results on test-retest reliability and criterion validity were replicated.

The preschool anxiety scale (PAS)

The PAS is a 28-item scale that is completed by a parent/guardian and which assesses anxiety in children between the ages of 2½ and 6½ years of age (Stone, Janssens, and Vermulst Citation2015). The PAS indicates if a child has elevated levels (reaching the cut-off point) in the five subtypes of anxiety: generalised anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, physical injury fear, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

One limitation of the PAS is that no norm data is available for the teachers’ version – thus, care needs to be taken in the interpretation of results. Spence et al. (Citation2001) reported the reliability and construct validity of the PAS, with the results being broadly consistent with the DSM-IV classification of anxiety disorders (although there was a high level of covariation between the subtypes of anxiety). The findings are also consistent with research relating to the structure of anxiety symptoms among primary school children (Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim Citation2016). However, in pre-schoolers, the subtypes of anxiety may be less differentiated than in older children, a premise that warrant further investigation. The high level of covariation suggests that, although there is sufficient unique variance in anxiety subtypes to justify their examination in clinical practice, it would be unwise to design assessments and treatments for preschool anxiety around discrete anxiety subtypes. For this research purpose, these two instruments are not used to determine or deny eligibility for services, nor are they used as clinical measures for diagnostic purposes.

Given the limitations of the standardised instruments, qualitative data from interview questions for children, parents, and class teachers were important. This research adopted the ‘Inclusion as Process’ (Quirke, Mc Guckin, and McCarthy Citation2022) approach. To make the research process accessible, the questions were simplified and both visual and auditory responses were accepted. Appendix A included questions for children, parents, and class teachers (adapted from Clarke, Hill, and Charman Citation2017). For example, two questions for the whole-class to discuss were ‘what is anxiety/scared/worry/frightened/anxious?’ and ‘how to reduce anxiety when your worry goes too big?’ Both verbal and non-verbal forms of the answers were accepted. Feedback from all the participants was invited and the questions were revised three times to make them more inclusive and universal. For example, instead of long and complicated questions, a simple and relevant question was found to be the most useful to begin the interview ‘Any concerns for your child so that I may help him in this project?’ In the results section, we would report the responses to the two questions for Junior and Senior Infant classes, in addition to the acceptability of the suggested storybooks on the topic of anxiety for the junior and senior infant classes.

Recruitment procedure and research sample

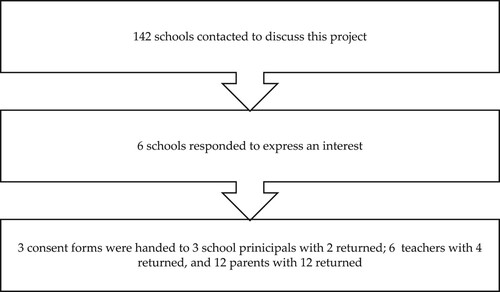

Following ethical approval from The Research Ethics Committee of the researchers’ host university, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, 12 children were recruited through convenience sampling (Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim Citation2016) and snowball sampling from 142 mainstream schools. Schools in the geographical location of Dublin City, and later expanded to South County Dublin were contacted through emails. shows the school and participant recruitment flowchart.

The sample of participants was referred by the Schools (Junior Infants and Senior Infants having anxiety, among them, three children have comorbidity condition of autism and nine without autism). Following consent from school management (with a principal information sheet regarding signs of anxiety in children), the nature of the study was described in detail (visually, orally, kinaesthetically / through the use of play and the Creative Arts) (Carroll and Twomey Citation2021) by the researcher to potential student participants outside their form class time. It was made clear that students were not obliged to participate in any aspect of the study and that they could withdraw at any time without having to give a reason and without prejudice. Participants were then presented with an information sheet for themselves and their parents/guardians and invited to participate in the questionnaire and the interview components of the study. They were asked to return the signed parent/guardian and teacher consent forms after a week if they were willing to participate in the research.

presented findings from the demographic survey regarding the characteristics of the child participants, as reported by parents/carers and class teachers. Twelve children participated (10 boys and two girls), aged between four and six years old (Mean = 4.4; S.D. = 0.52). All attended mainstream schools and one attended the autism unit within the mainstream school, from a range of socio-economic backgrounds and urban communities across the Republic of Ireland. Based on teachers and parental reports, participants had a range of anxiety presentations: ten of them with anxiety confirmed by SDQ and PAS (S) and one with anxiety confirmed by parent and teacher interviews (I). One boy with autism had no anxiety as measured by SDQ and PAS nor interviews but he was included in this project because he was referred by the teachers and parent as having ‘flight risk’, social difficulties and executive functioning difficulties such as attention problems. Four participating children had at least one co-morbid condition (autism: n = 3, language difficulties: n = 1).

Table 1. Child demographic information.

Eleven out of 12 participants had at least one risk factor (R) as reported in parent interviews and one reportedly had no risk factors. All case studies contained one or two parents (N = 12) and one class teacher (N = 12).

Authors (Citation2023a) reviewed the three types of risk factors of anxiety. First, genetic factors: anxiety disorders partly run in families with varying genetic transmission (Eley et al. Citation2003). In this current study, Jay had parental anxiety and Barry had depression in the extended family. Second, child factors: include an inhibited or withdrawn temperament, social withdrawal, intolerance of uncertainty, and difficulties with emotional regulation (Authors Citation2023a). In this current study, Jayden had sleep problems and Ray had sensory sensitivity issues. Third, environmental factors, such as environmental fostering of avoidance or specific parenting style (Authors Citation2023a). In this current study, Barry had relocation which was a stressful life event for the family, Leo had surgery during COVID-19 which was considered a trauma at his young age coupled with social isolation. The implication was children with anxiety had diverse profiles and more research in recruiting a bigger sample warranted investigation. In addition, children with one of these risk factors and early onset were ‘at risk’ of having recurring anxiety (Ramsawh et al. Citation2011). These could be taken into consideration when planning for a standard length of intervention (12–14 sessions) or a more intensive intervention (32 sessions).

Results

To address RQ 1, the 12 children were grouped according to their class. For two groups, a peer from their class was invited to practise social communication skills. All 12 children and two peers completed the groups and received a ‘certification of achievement’ or a ‘certificate of appreciation’.

RQ1. Did a 14-week ‘build-to-play’ approach lead to reports of reduced anxiety as reported by teachers, parents, and in observation reports from the researcher among a sample of 12 children (aged 4–6 years) who experience anxiety (n = 9) or anxiety and autism (n = 3)?

Attendance rate

The overall attendance rate was 92.9%, which was considered to be very high. During group time, the children were asked how many more sessions were needed. Most of them said ‘more’ or ‘until our young adulthood’ or ‘at least till the end of the year’. All these demonstrated the new approach was welcomed by most children. showed the attendance rate of the 12 children. The white colour indicated an absence of the child. The light grey colour indicated an 8-week pilot study of two groups which started last year and the dark grey colour indicated the groups that started this school year.

Table 2. 14 Sessions attendance in 2 schools, 5 groups, 12 case studies.

The attendance rate of this new approach was very high. The introduction of this novel approach facilitated children’s participation in learning as this approach was part of the school activities.

Case analysis of the two schools

The North City school that participated in this 14-week study was a DEIS school, defined by part of the Department of Education social inclusion strategy Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) to help children and young people who were at risk of or who were experiencing educational disadvantage (Kavanagh, Weir, and Moran Citation2017). It was located in the suburb on the north side of Dublin city in Ireland. 658 primary schools in Ireland were included in the DEIS initiative (Kavanagh, Weir, and Moran Citation2017).

In this all-boys school, there was one junior and one senior infant class. A total of seven children were referred by the school principal and two class teachers. All seven boys were included in the current study, with one to four children from the junior infant class in one group, and one child and one peer from the senior infant class forming a peer-mediated group.

The other South County Dublin school was a mainstream school, with boys and girls. This school also had one junior and one senior infant class. Six children from junior infant and senior infant classes formed two groups. showed the case comparison of the two schools.

Table 3. Case analysis of the two schools.

Results from the interviews and 2 instruments (Strength and difficulties questionnaire and preschool anxiety scale)

Before the commencement of the groups, ten out of 12 children were established to have emotional distress in the standardised assessment SDQ, and elevated levels of anxiety in some type(s) in either teacher’s or parent’s versions of the PAS. One child Barry was established to have elevated levels of anxiety in the interviews and risk factors of anxiety. One child Ray had no reported anxiety but was referred by parents and teachers as requiring support for his autism, flight risk, social communication skills and executive functioning (e.g. attention and impulse control). showed the completion of the SDQ, PAS, and interviews by teacher (T) or parent (T).

Table 4. Results from the initial interviews and 2 instruments (strength and difficulties questionnaire and preschool anxiety scale).

The learning from COVID-19 was that the commonly used parallel parent groups along with the children’s groups (e.g. Solish et al. Citation2020) were not feasible because of public health concerns. In addition, individual face-to-face interviews were ideal, but the options of video or phone interviews were also provided with email follow-up for sharing resource packs.

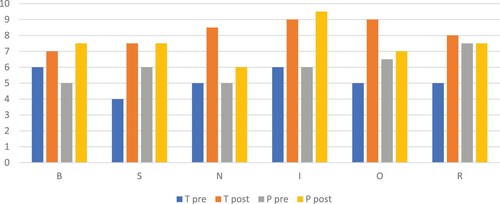

In the interviews of the South Dublin School, the teachers and parents were invited to give a rating of their child’s extent of participation in learning (0–10). showed the teacher’s pre (T pre) and post (T post) ratings and the parent’s pre (P pre) and post (P post) ratings. All ratings improved by 0.5 points to 4 points. The exception was the parent’s rating for R whose rating remained the same at 7.5.

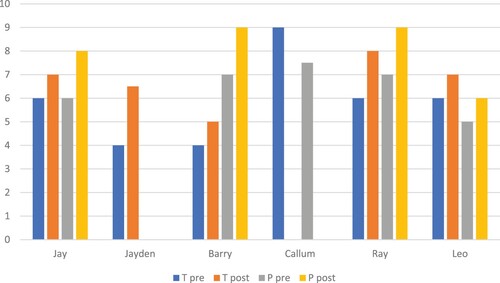

In the interviews with the North Dublin School, Callum missed the post-measurement because he left his current school, and Jayden’s parent could not complete the ratings. All those who completed the ratings, improved by 1–2.5 points regarding the children’s participation in learning (0–10). showed the details.

In summary, to address RQ1, two different schools, and five groups, with 12 children participated in this 14-week project. The answer was a ‘yes’: a 14-week ‘build-to-play’ approach led to reports of reduced anxiety as reported by teachers, parents, and in observation reports from the researcher among a sample of 12 children (aged 4–6 years) who experienced anxiety (n = 9) or anxiety and autism (n = 3). The attendance rate of 92.9% was very high. The presence of risk factor(s) of anxiety identified from the interviews (11 out of 12) and co-morbid condition of autism suggested future research on the intensive intervention of more than 14 weeks was warranted. Moreover, ten out of 11 ratings of teachers and parents demonstrated improvement in participation in learning by 0.5–4 points, while 1 set of ratings remained the same and 1 set of ratings was missing ( and ).

RQ2: Throughout study 1, interviews with parents (n = 12) and teachers (n = 6), what were the co-construction of strategies that are supporting RQ1 to reduce anxiety?

Table 5. Storybooks on the theme of anxiety for junior and senior infant classes.

Table 6. The stress response in kids.

However, the teachers and parents seldom noticed any ‘Fight’ responses such as ‘aggression’ and ‘hyperactivity’ and related them to anxiety. The new understanding of anxiety led to the proposed ‘fourth F’ that teachers and parents needed to be prepared to understand the relationship between the ‘Fight’ responses and anxiety and ‘frame’ them into positive coping. Accordingly, some strategies from play therapy about how to set behavioural boundaries while keeping a safe relationship were provided in the resource packs.

Blaustein and Kinniburgh (Citation2018) stressed that there were three primary danger responses available to human beings: Fight, Flight, and Freeze. The primary function of the triggered response was to help the child achieve safety in the face of perceived danger.

Adapted evidence-based strategies to reduce anxiety from the literature

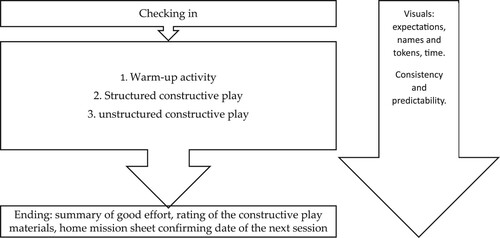

In the literature review, inclusion of the role of the teachers in co-design and co-delivery of this ‘Build-to-PlayTM’ approach were conducted. For example, the teachers co-designed which children to be grouped together and which peer to be invited. Another example was teachers co-delivered the whole-class story book reading. In addition, the inclusion of the role of the teacher in co-design and co-delivery of this approach and also how school can offer these types of ‘extra’ activities were also important. Since the structure of the sessions remained the same was one of the important strategies for the targeted young children with anxiety Goh et al. (Citation2011) and it was regarded as one of the effective autism-friendly strategies (Mpella et al. Citation2018), the current authors designed the following structure as outlined in .

Every session started with greetings with a visual attendance chart with stickers, followed by three group activities, namely (1) warm-up activity, for example, using six bricks to build something that could move; (2) a structured constructive play, for example, a magnetic set with a picture to build a vehicle; (3) unstructured constructive play, for example, a set of plastic tracks with a motor car that could move. The sessions ended by summarising everyone’s good effort as shown by the visual chart of names and tokens, the children rating how much out of 10 they liked the constructive play materials, a home mission sheet with skills practised, good effort, home mission tasks, and date of the next session written.

On top of that, children with anxiety needed visuals, consistency and predictability to feel safe and calm. Before the groups began, all the dates were given to parents and teachers. The plan was given to the children. On the day of the first group, the teacher introduced the first author to the children. The first author provided a visual chart with everyone’s name, date and time on it. These helped the children to transition to a new activity. Visual expectations or rules were provided, and the duration of 45 min or 60 min was announced at the beginning of the sessions so that children could make use of their time. For the last five sessions, a visual chart for counting down was provided. These were all effective strategies to support children with anxiety. It was observed that one of the children cried for the first three sessions, and afterwards no children cried. Some children gave feedback that consistency was important to them because ‘whenever it’s time to leave I want to cry’ (Jay); ‘you always said the same thing ‘Today you have 60 min to play’’ (B).

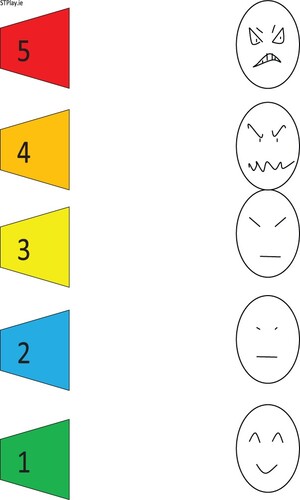

A new visual chart for checking in was created as shown in , adapted from Buron and Curtis (Citation2012). As some children needed co-regulation of their emotions by increasing their emotional awareness and acceptance. It was also used to check the children’s emotions during the sessions. The specific numbers, colours, and faces related to anxiety were matched with feeling words. The 5-point scale was also provided in the resource packs for the home mission.

1: calm or happy;

2: sad or nervous;

3: angry or frustrated;

4: very angry or overwhelmed;

5: super angry or I am going to explode.

Figure 5. 5-point Scale. Note. Adapted from Buron and Curtis (Citation2012).

Structured constructive play.

Magnetic vehicles with instruction cards

Classic lego sets with instructions

Unstructured constructive play.

Magnetic vehicles with instruction cards

Marble run

Straws and wheels

Links

Loose legos

A playground set that allows assembly of slides, swings, climbing bars and children's figures,

Train tracks

Loop the loop car

Selecting structured constructive play with simple instruction cards and easy-to-success was recommended for the first six sessions. Unstructured constructive play with more than one way to build was recommended for the rest of the sessions. At the same time, the children had the option of having both unstructured and structured constructive play-based on their preferences. This was linked to the inclusive framework of universal design for learning (Rose and Meyer Citation2002) to design this ‘Build-to-Play’ approach as inclusive.

In summary, to address RQ2: the co-construction of strategies to reduce anxiety in children included (1) structure (2) visuals (3) consistency (4) predictability (5) home mission. In addition, 10 sets of constructive play materials were rated highly by these 12 children. More structured and unstructured play materials available in schools could be explored with the children in future research.

Discussion

Implications for future research and practice

For future research and practice, the outcomes in three areas of development were recommended. First, practised emotional regulation: awareness of emotions, acceptance of emotions, and regulate emotions. Second, practised social communication skills: group problem-solving, friendships, turn-taking, joint attention, polite words, and so on. Third, practised executive functioning: planning, attention, impulse control, decision-making, evaluation, and so on. Therefore, the group leader’s task was to facilitate positive interactions among the children and to facilitate effective problem-solving and/or emotional regulation skills. For example, instead of laughing at others, the visual expectations included ‘use polite words ‘Thank you/ please/ sorry’.’ Or ‘Respect others.’

In addition, the summary of this new ‘build-to-play’ approach together with the analysis of the needs of children with anxiety, could be incorporated for staff continuous professional development (CPD). Staff CPD could make this new approach sustainable. Moreover, in terms of scalability – this research could scale up to involve different professionals to run the school-based intervention. The following was a list of what this new approach did and didn’t do.

What this ‘build-to-play’ approach did

Universal Design to facilitate access and participation

Regular groups (45 min or 60 min)

Consistent facilitator

Play together

Practise social skills and executive functioning

use of autism-friendly strategies such as Visual cues

Group structure

Free play time

Reinforcement schedule

Home missions and tip sheets

Adult facilitator to children ratio 1:2–5

What this ‘build-to-play’ approach didn’t do

exposure tasks to anxiety

Explicitly talk about anxiety

specific instruction on emotional regulation, problem-solving techniques

The following was the suggested plan for the 14 sessions and broadly divided into four stages through the analysis of the themes of the 14 sessions.

Stage 1: Rapport building to feel safe. Some children cried a lot, and wanted to leave. Structure, visual cues, predictability and consistency are important. Session 1–3. (Freeze, Flight)

Stage 2: Structure, and practice positive social skills. Structured constructive play. Conflicts resolution, problem-solving, sharing, helping. Sessions 1-6. (Fight, flight, freeze)

Stage 3: Boundaries, social expectations: safety, nice, respect. Executive functioning such as planning, decision making, problem solving and evaluation. Creativity and imagination. Friendship. Sessions: 7–14. (Fight)

Stage 4: Termination. Count down 3–5 sessions. (Fight)

In addition, Authors (Citation2023a) reviewed the risk factors of anxiety in children, namely genetic, inborn temperament, and environmental factors. This research prompted thinking relating to the genetic factors and environmental factors of the inter-generation cycle of mental health issues in families. Last but not least, feedback from teachers and parents demonstrated that parental involvement and teachers’ support were important for a positive outcome. For example, user-friendly packs for teachers and parents were developed and their feedback: ‘much needed.’

In relation to researcher positionality, the first author was an emerging researcher from a range of allied disciplines (speech and language therapy, play therapy and counselling, and tertiary education). In her research approach, she has expanded from the dominant medical model perspective of viewing children with ‘symptoms’ and ‘disorders' in ‘clinical settings’ to a more socially oriented model where she valued children’s ‘signs’ and ‘well-being’ in ‘non-clinical settings’. Contemporary approaches to education support an inclusive framework where research and practice are valued.

Bridging the gap between research and practice

This current study had the potential to contribute to the research-practice gap in addressing anxiety in young children. From the review of the literature on play-based group interventions to address anxiety in children aged 4–6 years, we identified that research on play-based intervention, inclusion framework and a bio-ecological model that were important for early childhood education was not well-developed. The primary focus was children with anxiety, children with anxiety and autism were also discovered. In particular, the age range were not identified for children aged 4–6 years.

To link back findings to teachers and school or classroom teaching and learning, the integration of children’s groups, how to support children with anxiety in the classroom with evidence-based strategies, how to enhance understanding and acceptance of anxiety problems in the classroom, and resource packs were all possible for curriculum planning. More importantly, for professional learning for teachers, teachers continuous professional development (CPD) could be developed from this approach so that teachers could be trained to run the children’s groups, learn this overarching ‘Build-to-PlayTM’ approach for curriculum planning, or supervision.

This current article explained the rationale of the study, including why early childhood education, why constructive play approach, why group format, why parental involvement and whole-class involvement, why needed an inclusive framework and bio-ecological model.

The results showed that all components of this project were important. These had implications for practice on how research could guide group leaders. These included first the play-based children’s groups with adapted and added strategies, then the parental involvement with a user-friendly resource pack, and last the class teachers’ involvement with a user-friendly resource pack.

One contribution of this article

For young children with anxiety, we developed a novel approach in schools to facilitate their access to participation in learning. The existing problems included missing specific research in the literature, missing bio-ecological models, and inclusion not planned at the beginning. This research invited voices from children, parents and teachers and attempted to make this approach sustainable. For example, their contribution was included in the resource packs for parents and teachers and after the completion of the children’s groups, the teachers and parents could continue to use these co-constructed understanding of anxiety and evidence-based strategies to support their children. In addition, if some children could not take part in the project for different reasons, the teachers and parents could use these resource packs to support those children.

Future research directions

Going forward, this 14-week school-based approach should be expanded to more intensive intervention and be more gender-balanced. More research on this topic, integrating a play-based approach, inclusive framework, and bio-ecological model for children with neurodiversity (such as autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) was much needed in Europe and beyond.

The research instruments SDQ, PAS, and interviews were essential to identify the children in need to support and evaluate progress. A referral from either teachers or parents for well-being support was accurate in terms of the presence of signs of anxiety. The interview questions were important to access the teachers’ and parents’ descriptions of the children, the presence of risk factors, and estimate the extent the child is participating in learning in school and at home (0–10). In addition, the two questionnaires were useful for confirming the presence of emotional difficulties in SDQ and the types and levels of anxiety in PAS. Furthermore, the children’s profiles from SDQ might indicate any social, behavioural, and attention difficulties that might warrant further investigation regarding the potential benefit of the play-based, social group design. RQ2 is also an important factor as it is more scale-able. This approach could be upgraded on demand. Furthermore, future research of bibliotherapy, that was, book selections with the theme of anxiety for storytelling for junior infant and senior infant classes was recommended for curriculum planning for enhancing young children’s understanding of anxiety and coping.

This current research was a new approach, based on literature evidence and a research project. The outcomes related to education included a reduction in childhood anxiety, improved social communication skills and executive functioning. More importantly, a collaborative understanding of what anxiety was and how to cope with stress was established. For example, for children who had any one of the risk factors of anxiety or additional needs such as autism (n = 8), a more intensive approach than the standard 14-week was needed to have better outcomes.

A critique of this research’s strengths and limitations would add value to future practice and research for young children’s well-being. Questions existed regarding the efficacy of the research project and if stronger results were possible over a longer period. Were the components of this approach good enough? The outcome was both a reduction in childhood anxiety and a collaborative understanding of what anxiety was and how to cope with it. Conceivably, this research would make an impactful contribution as change makers to educational practice, policy and theory. These contributed to the achievement of SDG 4: quality education and SDG10: reducing inequality, which the United Nations (UN) helped us to relate to how societies in Europe and beyond could look by 2030.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN.

Acknowledgements

PhD supervisor, M. Twomey’s unfailing support in the research journey was acknowledged. Authors wished her all the best in the career break.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stella Wai-Wan Choy

Stella Wai-Wan Choy is a PhD candidate at Trinity College Dublin. Stella obtained M.Soc.Sc.(Counselling)*Distinction in 2008 at The University of Hong Kong. Stella has been working as a Speech and Language Therapist for 20 years, added the roles of Play Therapist and Psychological Counsellor since 2008, part-time Lecturer at various universities since 2016, and Clinical Supervisor since 2017. Stella’s research interests are play approaches of inclusive education for children with autism and anxiety.

Conor Mc Guckin

Conor Mc Guckin, is an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at Trinity College Dublin. Conor convenes the Inclusion in Education and Society Research Group and is the founding editor of the International Journal of Inclusion in Education and Society. Conor’s research interests include: psychology applied to educational policy and practices, bullying/victim problems among children and adults, and special and inclusive education.

References

- Authors. 2023a. “Effectiveness of Peer-Mediated Lego® Play for Reducing Anxiety in Children Aged 4 to 6 Years with and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review.” In Learning Disabilities in the 21st Century. London: ProudPen. ISBN: 978-1-914266-22-3.

- Authors. 2023b. “To Fill the Gap: A Systematic Literature Review of Group Play-Based Intervention to Address Anxiety in Young Children with Autism.” Education Thinking. ISSN 2778-777X.

- Axline, V. M. 1950. “Play Therapy Experiences as Described by Child Participants.” Journal of Consulting Psychology 14 (1): 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056179.

- Axline, V. M. 1969. Dibs: In Search of Self (Vol. 6109). New York: Mansion.

- Baribeau, D. A., S. Vigod, E. Pullenayegum, C. M. Kerns, P. Mirenda, I. M. Smith, and P. Szatmari. 2020. “Repetitive Behavior Severity as an Early Indicator of Risk for Elevated Anxiety Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 59 (7): 890–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.08.478.

- Blackwell, W. H., and Z. S. Rossetti. 2014. “The Development of Individualized Education Programs: Where Have We Been and Where Should We Go Now?” SAGE Open (4): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014530411.

- Blaustein, M E, and K M Kinniburgh. 2018. Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard university press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 1998. The ecology of developmental processes.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 2007. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” Handbook of Child Psychology 1 (pp. 793-828).

- Buron, K. D., and M. Curtis. 2012. The Incredible 5-Point Scale: The Significantly Improved and Expanded Second Edition, Assisting Students in Understanding Social Interactions and Controlling Their Emotional Responses. The United States of America: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.

- Carroll, C., and M. Twomey. 2021. “Voices of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Qualitative Research: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 33: 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-020-09775-5.

- Christner, R. W., E. Forrest, J. Morley, and E. Weinstein. 2007. “Taking Cognitive-Behavior Therapy to School: A School-Based Mental Health Approach.” Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 37: 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-007-9052-2.

- Clarke, V., V. Braun, and N. Hayfield. 2015. “Thematic Analysis.” In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, edited by J. A. Smith, 222–248. London: SAGE Publications.

- Clarke, C., V. Hill, and T. Charman. 2017. “School Based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Targeting Anxiety in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Quasi-Experimental Randomised Controlled Trail Incorporating a Mixed Methods Approach.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47: 3883–3895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2801-x.

- Eley, T. C., D. Bolton, T. G. O'Connor, S. Perrin, P. Smith, and R. Plomin. 2003. “A Twin Study of Anxiety-Related Behaviours in pre-School Children.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44 (7): 945–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00179.

- Essau, C. A., P. Muris, and E. M. Ederer. 2002. “Reliability and Validity of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale and the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders in German Children.” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 33 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(02)00005-8.

- Etikan, I., S. A. Musa, and R. S. Alkassim. 2016. “Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling.” American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.

- Goh, T., M. Sung, Y. Ooi, C. Lam, A. Chua, D. Fung, and P. Pathy. 2011. “Effects of a Social Recreational Program for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders - Preliminary Findings.” European Psychiatry 26 (S2): 290–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(11)72000-4.

- Goleman, D. 1995. Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

- Goodman, R. 2001. “Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 40 (11): 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015.

- Hayashida, K., B. Anderson, T. Paparella, S. F. Freeman, and S. R. Forness. 2010. “Comorbid Psychiatric Diagnoses in Preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Behavioral Disorders 35 (3): 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874291003500305.

- Kavanagh, L., S. Weir, and E. Moran. 2017. The Evaluation of DEIS: Monitoring Achievement and Attitudes among Urban Primary School Pupils from 2007 to 2016. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- McLachlan, C., M. Fleer, and S. Edwards. 2018. Early Childhood Curriculum: Planning, Assessment and Implementation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mpella, M., C. Evaggelinou, E. Koidou, and N. Tsigilis. 2018. “The Effects of a Theatrical Play Programme on Social Skills Development for Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Natural & Applied Sciences 22 (3): 828–845.

- Murray, J., ed. 2020. “Mind Yourself. The Mental Health and Wellbeing Reading Guide.” In Themed Section of Worry, Stress and Anxiety, 39–51. Ireland: Children’s Books Ireland.

- Nguyen, C. 2017. “Sociality in Autism: Building Social Bridges in Autism Spectrum Conditions Through LEGO® Based Therapy” PhD diss., University of Hertfordshire.

- Quirke, M., C. Mc Guckin, and P. McCarthy. 2022. “How to Adopt an “Inclusion as Process” Approach and Navigate Ethical Challenges in Research.” In Sage Research Methods Cases Part 1. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529605341.

- Ramsawh, H. J., R. B. Weisberg, I. Dyck, R. Stout, and M. B. Keller. 2011. “Age of Onset, Clinical Characteristics, and 15-Year Course of Anxiety Disorders in a Prospective, Longitudinal, Observational Study.” Journal of Affective Disorders 132 (1-2): 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.006.

- Reaven, J. A. 2009. “Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders and Co-Occurring Anxiety Symptoms: Implications for Assessment and Treatment.” Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 14 (3): 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00197.x.

- Riddle, S., D. Bright, and A. Heffernan. 2022. “Education, Policy and Democracy: Contemporary Challenges and Possibilities.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 54 (3): 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2083678.

- Rose, D. H., and A. Meyer. 2002. Teaching Every Student in the Digital age: Universal Design for Learning. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Solish, A., N. Klemencic, A. Ritzema, V. Nolan, M. Pilkington, E. Anagnostou, and J. Brian. 2020. “Effectiveness of a Modified Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program for Anxiety in Children with ASD Delivered in a Community Context.” Molecular Autism 11 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-020-00341-6.

- Spence, S. H., R. Rapee, C. McDonald, and M. Ingram. 2001. “The Structure of Anxiety Symptoms among Preschoolers.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 39 (11): 1293–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00098-X.

- Stone, L. L., J. M. A. M. Janssens, A. A. Vermulst, et al. 2015. “The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties of the Parent and Teacher Version in Children Aged 4–7.” BMC Psychology 3: 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0061-8.

- Sung, T. J., P. Pathy, D. S. Fung, R. P. Ang, and C. M. Lam. 2011. “Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Child Psychiatry & Human Development 42: 634–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1.

- Vasa, R. A., L. Kalb, M. Mazurek, S. Kanne, B. Freedman, A. Keefer, and D. Murray. 2013. “Age-related Differences in the Prevalence and Correlates of Anxiety in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7 (11): 1358–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.005.

Appendix A

Interview questions to children, parents, and class teachers

Ask all children in Junior infant and Senior infant classes two questions, they can respond by drawing, writing, talking and taking a photo of facial expression/gesture and email to XXX

what is anxiety/scared/worry/frightened/anxious?

how to reduce anxiety when your worry goes too big?

Interview Parent before the groups

(adapted from Clarke, Hill, and Charman Citation2017)

Any concerns for your child so that I may help him in this project?

What is your understanding of anxiety/worry in children?

_____________________________________________________________________

Any signs/presentations of anxiety you know?

_____________________________________________________________________

Any causes/ contributing factors of anxiety in children?

Can tick more than one

genetic factors:

□ family/ relatives with anxiety or mental health problems

_______________________________________________________________

factors intrinsic to the child:

□ shyness- inhibition in response to a novel social situation

□ sensory sensitivities

□ social withdrawal- consistently playing alone

□ difficulties with emotional regulation- express emotions in the peer group (sadness, anxiety, fearfulness)

environmental factors:

□ parenting style of caregivers discourage (or might not encourage) exploration of novel situations or stimuli

□ unsuccessful peer interactions

□ others:

_____________________________________________________________________

| 3. | What coping behaviours did they use (silent, withdrawal, avoidance, seek help from others etc.) | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 4. | Have you noticed any changes in ________________ recently? | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 5. | To what extent _______________is participating in learning? | ||||

(please mark with an ‘x’)

Interview teacher before the groups

(adapted from Clarke, Hill, and Charman Citation2017)

What is your understanding of anxiety/worry in children?

_____________________________________________________________________

Any signs/presentations of anxiety you know?

_____________________________________________________________________

Any causes/ contributing factors of anxiety in children?

_____________________________________________________________________

| 2. | Using your understanding, how does anxiety impact on your pupil’s behaviours? | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 3. | What sort of feelings/emotions do you see in your pupil? | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

How does s/he cope with these behaviours and feelings?

____________________________________________________________________

What does anxiety look like to you as the teacher?

____________________________________________________________________

Physiological or physical aspects of anxiety?

____________________________________________________________________

| 4. | When has s/he done something which they thought would be difficult, but s/he was okay with (what was different? why was it surprising about it?) | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 5. | What coping behaviours did they use (silent, withdrawal, avoidance, etc.) | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 6. | What is your understanding of her/his behaviours in school/classroom (what have you heard from parent’s, your pupil’s friends, etc.) | ||||

____________________________________________________________________

| 7. | Have you noticed any changes in ________________ recently? | ||||

_____________________________________________________________________

| 8. | To what extent _______________is participating in learning? | ||||

(please mark with an ‘x’)