ABSTRACT

In March 2023, the Department of Education published the ‘Primary Curriculum Framework’ for primary and special schools in Ireland. Reflecting trends in international curriculum reform centred on the needs and priorities of twenty-first century learning and life, the Framework proposes a set of seven key competencies which are presented to underpin children’s learning and development during their time in primary school. In this paper, we focus on one such key competency, ‘being an active learner.’ We aspire to theoretically conceptualise this key competency in relation to the psychological constructs of ‘learner identity’ and ‘learning to learn.’ We argue that such a conceptualisation must not only reflect the cognitive and metacognitive ‘how’ of learning, but also the affective ‘who’ of the learner. Arising from this, we explore Irish primary school children’s perceptions of themselves as learners, drawing on 188 children’s open-ended descriptions of themselves as learners and 136 online survey responses to the ‘Myself-As-Learner Scale’ (MALS). Despite a majority of children describing themselves as learners in positive terms, findings indicate that Irish primary school children report lower mean MALS scores than standardisation data for the scale, with statistically significant differences revealed between genders and class levels. Implications for policy and practice are discussed, as well as opportunities associated with the key competency if meaningfully realised.

1. Introduction

Throughout the past century of primary education in Ireland, ‘influences on curriculum [have] evolved from a colonial, to a nationalist, to a child-centred perspective,’ with each having ‘a particular impact on the design, content, and delivery of the curriculum in schools’ (Walsh Citation2016, 3). Indeed, Walsh (Citation2016) attests that such evidently disparate influences have caused the history of primary curricula in Ireland to embody ‘a tale of a swinging pendulum’ (1). As such, in the present context of the rollout of the ‘Primary Curriculum Framework’ (Department of Education Citation2023), that pendulum now swings definitively towards the needs and priorities of twenty-first century learning and life.

1.1. Introducing the ‘Primary Curriculum Framework’

The trajectory of reforming the current primary school curriculum (Department of Education and Science [DES] Citation1999) was initiated in 2011 with a comprehensive consultation process with educational stakeholders on the curriculum priorities for primary education (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment [NCCA] Citation2012). FitzPatrick, Twohig, and Morgan (Citation2014) assert that the priorities emanating from this initial consultation ‘conjure up positive images of future primary school children as capable and competent learners’ (281, emphasis maintained). Six key priorities were extrapolated from their responses:

development of life-skills, including those related to lifelong learning, through a broad curriculum;

communication competencies, encompassing oral expression, Gaeilge, a third language, and communicating using ICT;

wellbeing, including emotional, spiritual, and physical domains;

fundamental literacy and numeracy skills to provide a solid foundation;

motivation and engagement through a child-centred approach which fosters a love of learning; and

a sense of identity and belonging, with an awareness of oneself as a learner.

In the intervening years, ongoing consultation took place through a ‘Schools Forum,’ as well as through surveying of and focus groups with parents and children (NCCA Citation2019a). Despite some contrasting and conflicting discourses, all parents emphasised the need to prepare children for a rapidly changing Irish society and economy (NCCA Citation2019a). Furthermore, children of all ages expressed a clear preference for collaborative and engaging learning, along with an enthusiasm for ICT (NCCA Citation2019b). Consultation also took place on the subject-structure and time allocation for a prospective curriculum (NCCA Citation2018). The rich, varied, and representative insights ascertained from this engagement distinctly informed the ‘Draft Primary Curriculum Framework,’ released for consultation by the NCCA in February 2020, ultimately culminating in the publication of the ‘Primary Curriculum Framework for Primary and Special Schools,’ henceforth referred to as the Framework, by the Department of Education in March 2023.

From the outset, it is attested that ‘the framework embodies society’s broadly held view of what a curriculum should provide for our children as we look further into the twenty-first century’ (Department of Education Citation2023, 3). The realisation of this assertion is underpinned by eight overarching principles of teaching, learning, and assessment which convey what is valued in primary education: assessment and progression, engagement and participation, inclusive education and diversity, learning environments, partnerships, pedagogy, relationships, and transitions and continuity. In addition, the Framework identifies seven inextricably linked key competencies that seek to ‘equip children with the essential knowledge, skills, concepts, dispositions, attitudes, and values which enable them to adapt to and deal with a range of situations, challenges, and contexts’ (8), traversing all curriculum areas. As McGuinness (Citation2018) notes, a move to a competency-based model such as this ‘can be seen as part of a more general thrust in educational systems across the world to pursue broader learning goals beyond traditional school subjects,’ with the aspiration ‘to improve student learning in preparation for twenty-first century living and twenty-first century work’ (39). This progressive paradigm shift is most prominently exhibited in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s ‘DeSeCo’ project (Citation2005) and its subsequent ‘Future of Education and Skills 2030’ publication (Citation2018) which, when taken together, propose six such key categories of competence: using tools interactively, interacting in heterogeneous groups, acting autonomously, creating new value, reconciling tensions and dilemmas, and taking responsibilities. Moreover, such a move within the Framework draws parallels with recent reforms at both pre-primary and post-primary levels within the Irish education system, namely the ‘Aistear’ framework (NCCA Citation2009) and the ‘Framework for Junior Cycle’ (Department of Education and Skills Citation2015) respectively, ensuring continuity in children’s development (McGuinness Citation2018). As such, within the Framework, the seven key competencies essential to preparation for life in the twenty-first century are identified as: being an active citizen, being creative, being a digital learner, being mathematical, being a communicator and using language, being well, and, the focus of the present paper, being an active learner.

1.1.1. Key competency of ‘being an active learner’

In this paper, we focus specifically on the key competency of ‘being an active learner’ within the Framework (Department of Education Citation2023), originally proposed as ‘learning to be a learner’ in the Draft Primary Curriculum Framework (NCCA Citation2020). It is an evidently broad and multifaceted competency which is characterised to help ‘children develop an awareness of themselves as learners’ (11). Moreover, it is described to underpin children’s development as agentic learners, fostering essential knowledge, skills, concepts, attitudes, values, and dispositions, including those related to goal-setting, problem solving, reflexivity, and curiosity. In addition, it encompasses children’s ability to learn collaboratively with others, supporting a sense of belonging, connection, and empathy. In light of this evidently broad and wide-ranging definition, we propose that this key competency can be most meaningfully conceptualised and realised through the psychological construct of ‘learning to learn,’ oftentimes abridged as L2L. We will now explore such a conceptualisation in relation to the literature base in order to delineate the most effective realisation of the key competency of ‘being an active learner’ in Irish primary schools.

First, however, it is necessary to disentangle the relationship between L2L and the interdependent, yet not analogous, construct of ‘learner identity.’ Learner identity is a construct which reflects an individual’s whole identity as a learner, rather than merely presenting part of one’s identity as that of being a learner (Kolb & Kolb, Citation2009). It stipulates that the socio-cultural aspects of an individual’s experiences shape their subjective experience of being a learner (Parkinson and Brennan Citation2020). Central to the construct is an individual’s awareness and conception of themselves as an autonomous, dynamic, and reflective actor, continuously engaging in the ‘emotional and cognitive process of becoming and being a learner’ (Coll & Falsafi, Citation2010, p. 219). By acknowledging the unique story, voice, and capabilities of each learner, the meaningful realisation of learner identity enables individuals to ‘see themselves as learners,’ compelling them to ‘seek and engage life experiences with a learning attitude and [to] believe in their ability to learn,’ both independently and collaboratively (Kolb & Kolb, Citation2009, p. 5). As such, it represents a fundamental potentiating force for lifelong learning, making it essential to human flourishing within the society of the twenty-first century (Parkinson et al. Citation2021). Stemming from this, when conceptualising the key competency of ‘being an active learner’ within the Framework, it is evidently informed by the development of a distinct sense of learner identity, the practical realisation of which can be better understood through an exploration of the process of L2L.

1.2. Learning to learn

Radovan (Citation2019) explains that the origins of L2L can be traced to the 1980s when the processes through which individuals ‘control, direct, and manage’ their learning became of interest to researchers, reflecting a contemporaneous shift from a teacher-oriented behavioural conception of learning to an increasingly cognitive approach which centred on ‘how information is processed and stored in memory’ (31). Over time, such an emphasis, complemented by advances in the field of metacognition, encompassing the planning, monitoring, and regulation of one’s thinking, led to a characterisation of L2L as ‘“classroom practices” … aimed at promoting “learner autonomy” and enabling learners to create new “learning tools”’ (Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd Citation2013, 610). This characterisation is evident in the identification of L2L as one of eight ‘Key Competences for Lifelong Learning’ by the European Commission (Citation2006, 12). The Commission describes L2L in largely cognitive and metacognitive terms surrounding the processing, assimilation, and application of knowledge and skills, as well as the organisation and management of information and time. This definition also somewhat acknowledges the affective and social dimensions of L2L, highlighting the role of motivation, confidence, and persistence in overcoming obstacles, either individually or collaboratively. In 2018, the Commission revised the aforementioned key competences, incorporating L2L to a broader ‘Personal, Social, and Learning Competence’ (European Commission Citation2018, 51).

In addition, a predominantly cognitive and metacognitive conceptualisation of L2L is similarly reflected across varying international jurisdictions. For instance, L2L is acknowledged in the ‘Personal Development and Mutual Understanding’ strand of Northern Ireland’s primary curriculum (Council for Curriculum, Examinations, and Assessment Citation2007), L2L is described to involve reflection on learning processes as one of eight key principles of the New Zealand curriculum for years one to thirteen (Ministry of Education Citation2007), and its definition as ‘the ability and willingness to adapt to novel tasks’ has been extrapolated from the Finnish Learning to Learn Framework (Black et al., Citation2006, p. 181). While contemporary authors regularly argue the need to wrest the epistemological basis of L2L from such ‘a narrow identification with self-regulated learning and meta-cognition’ (Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd Citation2013, 610), as will be explored later, it is nonetheless worthy to first examine this narrow vision of the L2L.

1.2.1. A narrow vision of L2L – the ‘how’ of learning

Radovan (Citation2019) emphasises the inextricable link between L2L and ‘the cognitive and metacognitive aspects of learning’ (30). Further, Lee (Citation2014) definitively identifies L2L as a crucial ‘twenty-first-century cognitive competence’ (466). Cognitive learning strategies are defined as intentional mental processes implemented by an individual in pursuit of a specific learning goal involving self-regulation and control (Radovan Citation2019). Radovan (Citation2019) outlines that they can be categorised across three different levels of cognitive engagement. First, ‘rehearsal strategies,’ such as repetition and mnemonics, are useful for the simple retrieval of information but not for deeper understandings. Second, ‘elaboration strategies,’ including paraphrasing and forming analogies, require the minor transformation of content by summarising and making connections. Third, ‘organisational strategies,’ like making notes and mind maps, are based on the deeper processing of information related to the ways in which learners structure their knowledge. Metacognitive strategies, by contrast, involve guiding or managing the learning process (Radovan Citation2019). Again, Radovan (Citation2019) classifies these across three sequential categories. First, ‘planning strategies,’ including setting goals and selecting resources, take place before the learning process in preparation for the task at hand. Second, ‘managing strategies,’ like maintaining attention and continuous self-testing, relate to solving problems and guiding learning during an activity. Third, ‘monitoring strategies’ take place subsequent to the learning process, comprising the evaluation of performance and identification of problems.

Radovan (Citation2019) emphasises that evidence of a positive relationship between the use of such cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies and academic achievement consistently emerges in empirical research, suggesting that they enhance efficiency and effectiveness in learning. Furthermore, Radovan (Citation2019) explains that the development of such strategies in learners is not passive, but rather is contingent upon their intentional instruction through either direct or indirect means. Direct instruction, also termed the ‘isolated’ implementation of L2L by Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe (Citation2002, 307), is characterised by discrete courses or lessons focussing on a particular skill, thus limiting opportunities for transferability. Conversely, indirect instruction, or the ‘embedded’ implementation of L2L (Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe Citation2002, 307), transpires contemporaneous to the teaching of regular content, thereby guaranteeing ‘to some extent the occurrence of transfer’ (Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe Citation2002, 307). Notwithstanding such a preference, however, Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe (Citation2002) assert that the implementation of this approach in exclusivity restricts L2L ‘to some general advice and vague learning tips’ (309). Therefore, it remains necessary to broaden the vision of L2L beyond the narrow remit of the ‘how’ of learning represented in the cognitive and metacognitive domains as explored thus far.

1.2.2. A broad vision of L2L – the ‘who’ of the learner

In this vein, Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd (Citation2013) definitively expound that ‘the embodied, situated, affective and creative dimensions of L2L have previously been subordinated to the cognitive dimension, and have thus received insufficient attention’ (610). Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie (Citation2015) postulate that such subordination can be attributed to the territorialisation of educational disciplines such as psychology and sociology. It is argued that the contemporary pre-eminence of psychology in learning theory has engendered the dominant cognitive and behavioural perspective of L2L, as described above. The authors call for a more nuanced interdisciplinary approach, embracing the social sciences and the humanities, while also acknowledging ‘the inner world of the human imagination’ (82), in order to broaden the vision of L2L. Such a shift is necessary to transcend the current individualistic and task-oriented approach to L2L which sets arbitrary horizons to a learner’s efforts through its predetermined educational ends (Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd Citation2013). Indeed, Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd (Citation2013) emphasise that this predetermination stifles creativity in the learning process through a reliance on predictable and reified practices.

By contrast, the broader vision of L2L intentionally evades such reification. For instance, aspirations to develop a ‘fluid sociality’ (Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie Citation2015, 83) based upon a ‘reflexive social epistemology of learning to learn’ (73) certainly appear intangible and elusive at first. Nevertheless, Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd (Citation2013) suggest to begin by considering learning as a fundamentally social process, wherein L2L embodies an end in and of itself rather than a means to a performative end. Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe (Citation2002) note that such a perception of L2L enables individuals to recognise learning as a goal for its own sake, cultivating a desire to become lifelong learners through a particular set of attitudes and dispositions, reflective of a sense of learner identity as described above. Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie (Citation2015) further strive to explicate the construct by outlining the integration of cognition and metacognition with affective factors, including motivation, emotions, and self-regulation, in a socialised and collaborative learning context. As such, communities of learners inculcated with a broad vision of L2L come to practice citizenship, develop reflexivity, and engage in questioning through dialogical, inquiry-based, and experiential tasks (Pirrie and Thoutenhoofd Citation2013), wherein they ‘continuously interrogate their experiences of and orientation towards learning’ (Thoutenhoofd and Pirrie Citation2015, 75).

While such multidimensionality may indeed seem challenging to envisage in the practical classroom context, it merely ensures that L2L appropriately reflects the complexity and variability of the human condition itself. By recognising the myriad and, oftentimes, nebulous factors which impinge upon an individual’s learning engagements, this conceptualisation of L2L acknowledges and embraces the ‘who’ of the learner. As such, while it is evidently valuable to consider the cognitive and metacognitive ‘how’ of learning, its relevance is contingent upon the concurrent recognition of the unique person brought to the learning process, as well as the context in which it transpires. In this sense, L2L is not limited to the development of a toolkit of skills and strategies in pursuit of effectiveness and efficiency in learning. Rather, it must concurrently support the development of a sense of learner identity, cultivating learning dispositions and attitudes, accounting for prior experiences and the sociocultural context, and recognising the collaborative, dialogical, and experiential nature of learning. In this paper, we argue that the realisation of such a conceptualisation will effectively support the key competency of ‘being an active learner’ within the Primary Curriculum Framework. Stemming from this, we now turn to explore Irish primary school children’s perceptions of themselves as learners in preparation for this key competency.

2. Methodology

The present study, supported by the Teaching Council’s ‘John Coolahan Research Support Framework,’ embodied a mixed-methods cross-sequential design, exploring Irish primary school children’s perceptions of themselves as learners. Owing to Covid-19 restrictions at the time, it was decided that online surveys were the most appropriate means of data collection. As such, in the final term of the 2020/21 academic year, immediately after the reopening of schools following their second closure due to the pandemic (Hale et al. Citation2021), participation invites were sent to all primary schools in Ireland using email addresses provided on the website of the Department of Education. Thirteen primary schools agreed to participate in the study, representing a spread of school types relating to gender, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural settings. Teachers of Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Classes in participating schools were invited to share survey links with children as assigned homework across a given week.

The first of such surveys included demographic items related to gender, class level, and age, along with an open-ended response item which invited children to describe themselves as learners. From our thirteen schools, 188 children completed this qualitative measure. Participants ranged in age from nine to thirteen years, with a mean age of 11.93 years. outlines further demographic information for children who participated in the qualitative survey.

Table 1. Participant demographics for qualitative survey.

Subsequently, teachers of Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Classes were invited to share the link to a second survey comprising Burden's (Citation1998) ‘Myself-As-Learner Scale’ (MALS), as well as demographic items again relating to gender, class level, and age. While it is important to note that no quantitative measure can capture the variability of L2L and learner identity as explored above, we argue that the MALS represents good construct validity in this regard, owing to its inclusion of items related to children’s skills and strategies in learning (e.g. ‘I know how to be a good learner’), as well as their attitudes and dispositions towards learning situations (e.g. ‘I like having difficult work to do’). As such, this 20-item scale appropriately captures both the narrow and broad visions of L2L explored above, recognising both the ‘how’ of learning and the ‘who’ of the learner in cultivating a positive sense of learner identity. Furthermore, the measure has been repeatedly demonstrated to yield high internal consistency (Burden Citation1998; Erten Citation2015; Sangawi, Adams, and Reissland Citation2018). Typically utilised as a measure of academic self-concept, MALS scores have also been shown to predict children’s achievement in academic tasks (Bayraktar-Erten and Erten Citation2014; Erten and Burden Citation2014). Following the reverse-coding of five items, the MALS provides a score ranging from 20 to 100 for each participant, with a mean of 71.0 established in the initial standardisation of the scale (Burden Citation1998). Comparable mean scores ranging from 72.2–75.1 have been demonstrated in subsequent validations and implementations of the scale (Chalk and Bizo Citation2004; Erten Citation2015).

From our thirteen schools, 136 children from Fourth to Sixth Class completed the second quantitative survey described above. The assignment of surveys as homework on different days may explain the attrition in participants between the first and second surveys. On this occasion, participants again ranged in age from nine to thirteen years, with a mean of 10.92 years. below outlines demographic information for children who participated in the quantitative survey.

Table 2. Participant demographics for quantitative survey.

Both surveys outlined above included short animated videos for children explaining the procedure for and purpose of the task at hand. The study followed appropriate ethical guidelines, including parental consent and child assent, and was approved by the College ethics committee.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative measure

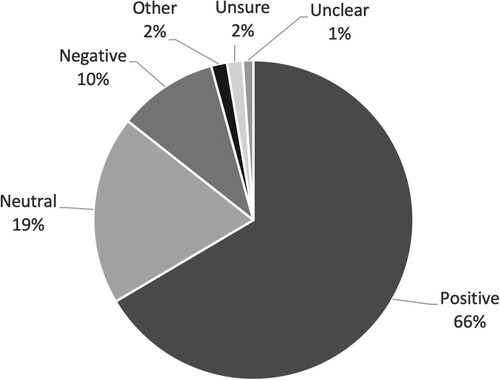

As noted above, 188 participants responded to the qualitative measure inviting children to describe themselves as learners. Responses were analysed by the researchers and determined to reflect children’s positive, negative, or neutral perceptions of themselves as learners. A further three categories were established to reflect responses that were unsure, unclear, or other.

Firstly, two-thirds of participants (n = 125) were determined to demonstrate positive perceptions of themselves as learners. These responses included terms and phrases such as ‘good,’ ‘intelligent,’ ‘smart,’ ‘hard-working,’ ‘good listener,’ ‘serious,’ and ‘interested.’ Children in this category expressed clear confidence in their learning skills and abilities, as well as their enjoyment of the learning process:

I would describe myself as a hard worker who gets stuck sometimes but always finds a way to solve the problem. (Boy, Sixth Class)

I personally think I’m a good learner and have amazing grades. (Girl, Sixth Class)

Somebody who likes to be involved and not afraid to ask questions. (Boy, Fifth Class)

I would describe myself as a person that takes in things really easy. (Girl, Fourth Class)

I find it hard to learn things and when it comes to concentrations I can get confused quite easy. (Girl, Sixth Class)

Not that smart. (Boy, Fourth Class)

Finds some stuff hard. (Boy, Fifth Class)

I think I am like a novice, I am good at my work but I make mistakes as well. (Boy, Fifth Class)

I struggle sometimes but I can be good at other times. (Girl, Fifth Class)

Not the worst or best. (Girl, Sixth Class)

I’m fine but I’m not the best. I couldn’t get it the first go it would take a couple of tries but then sometimes I wouldn’t get it all but I try my hardest. (Girl, Sixth Class)

3.2. Quantitative measure

A mean MALS score of 68.8 was calculated for participating Irish primary school children, a lower score than that established in the previously mentioned initial standardisation of the scale (Burden Citation1998), as well as subsequent validations and implementations (Chalk and Bizo Citation2004; Erten Citation2015). Additionally, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) demonstrated a significant effect of gender on MALS scores, F(2, 133) = 3.97, p = .02, with males reporting greater scores (M = 71.20) than both females (M = 67.76) and those reporting as ‘other’ (M = 53.76). Similarly, another one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of class level on MALS scores, F(2, 133) = 14.74, p < .001, with the highest scores reported by children in Fourth Class (M = 75.42), followed by those in Sixth Class (M = 68.26), with those in Fifth Class reporting the lowest scores (M = 62.41).

4. Discussion

In this paper, we aspire to better understand Irish primary school children’s perceptions of themselves as learners in preparation for the key competency of ‘being an active learner’ within the Primary Curriculum Framework (Department of Education Citation2023). Our analysis is grounded within the theoretical conceptualisation which we propose for this key competency, attesting that it can be most meaningfully realised through the development of a positive sense of learner identity achieved through the process of L2L. In this sense, we argue for a broad vision of L2L, which not only recognises the cognitive and metacognitive ‘how’ of learning, but also the embodied, situated, affective, and creative dimensions of learning which recognise the ‘who’ of the learner.

Stemming from this, findings from our qualitative measure indicate that two-thirds of children participating in the research hold positive perceptions of themselves as learners, expressing confidence in their skills and abilities as learners (i.e. the ‘how’ of learning), as well as positive attitudes and dispositions towards learning (i.e. the ‘who’ of the learner). However, this is somewhat challenged by the lower mean score for Irish primary school children on the MALS compared to previous standardisations and implementations of the measure (Burden Citation1998; Chalk and Bizo Citation2004: Erten Citation2015). While the MALS was chosen due to its incorporation of items related to the ‘how’ of learning and ‘who’ of the learner, the apparent discrepancy between qualitative and quantitative measures in this instance may reflect shortcomings in the construct validity of the scale for the purposes of this study. Nonetheless, the lower mean MALS score in this study warrants attention, highlighting the value and necessity of the key competency ‘being an active learner’ within the Framework. This value and necessity is further underscored by the one-tenth of participants in our qualitative measure reporting negative perceptions of themselves as learners, expressing a clear lack of confidence in their abilities as learners and a lack of enjoyment in the learning process.

Despite the evident strengths and implications of this research, it is important to discuss a number of notable limitations additional to those identified above. For instance, it is noteworthy that the online surveys in this research were completed following the second period of school closures due to Covid-19 in Ireland, which may have negatively influenced children’s perceptions of themselves as learners at the time. Further research is necessary to determine children’s perceptions in the post-pandemic context. Additionally, despite the robust nature of sampling for this study, the participation of children from a narrow sample of thirteen schools limits the generalisability of our findings. However, this is somewhat tempered by the spread of school types relating to gender, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural settings in our sample. Finally, variance in MALS scores across genders and class levels suggests differences in children’s perceptions of themselves as learners between groups, warranting further investigation and requiring specific attention from teachers and schools in their implementation of the Framework.

On this note of implementation, Walsh (Citation2016) cautions that, despite the radical nature of historical curricular reform in Ireland, it has been accompanied by a trend of insufficient focus on implementation, emphasising that curricular aspirations have traditionally not been accompanied by the necessary roadmap to ensure their practical realisation. In fact, the existing primary school curriculum (DES Citation1999) identifies ‘learning how to learn’ as an overarching aim of primary education (7). Moreover, the 1999 curriculum conceptualises the construct in the broader sense through reference to developing ‘an appreciation of the value and practice of lifelong learning’ (7). Despite this inclusion, however, it is reasonable to argue that this aim has failed to influence Irish classroom practice to any meaningful extent in the intervening quarter century. As such, Walsh (Citation2016) highlights that creating a sense of teacher ownership is integral to ensuring that policy reform is realised in practice. This can be achieved by broadening the vision of L2L held by teachers, the majority of whom presently have a narrow sense of the construct centred on achievement-based remediation and support (Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe Citation2002). By contrast, those who conceptualise L2L in a broader sense are described to ‘endeavour to develop attitudes and skills which are important outside the school and classroom context’ (316), perceiving it as a vital life skill which warrants extensive emphasis in their classroom practice. Furthermore, Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe (Citation2002) found that such teachers desire to empower their students through L2L. Ultimately, therefore, in order to wholly achieve the key competency of ‘being an active learner,’ as identified within the Framework, it is necessary that a sense of ownership is cultivated within teachers by broadening their vision of L2L. Without the realisation of such clarity, L2L is likely to remain wielding ‘a minimal impact on … teaching behaviour’ (Waeytens, Lens, and Vandenberghe Citation2002, 319), reflecting the policy-practice vacuum in Irish primary schools pertaining to L2L at present.

Overall, this paper presents important implications for the implementation of the Primary Curriculum Framework in Irish schools over the coming years, particularly in relation to the key competency of ‘being an active learner.’ Firstly, drawing on the psychological constructs of learner identity and L2L, we theoretically conceptualise this key competency as the concurrent development of both the ‘how’ of learning and the ‘who’ of the learner, thereby potentiating success as lifelong learners in the society of the twenty-first century. Moreover, in exploring Irish primary school children’s perceptions of themselves as learners, we shed light on the value of the inclusion of this key competency within the Framework. Despite the initial promise of our qualitative findings, lower mean MALS scores amongst our sample, coupled with one-tenth of children expressing negative perceptions of themselves as learners, underscores the necessity and value of this key competency within the Framework. Finally, we emphasise the central role of teachers in the implementation of the key competency, highlighting the need to broaden their vision of L2L beyond cognitive and metacognitive strategies which enhance effectiveness and efficiency in learning. Ultimately, if successfully realised in the manner proposed here, the competency of ‘being an active learner’ has transformative potential for Irish learners throughout the twenty-first century and beyond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seán Gleasure

Seán Gleasure is a Teaching Fellow in Educational Psychology at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick. A former primary school teacher, he holds a B.Ed. in Education and Psychology from Mary Immaculate College and an M.Ed. in Applied Studies in Teaching and Learning from West Chester University of Pennsylvania, USA. He is a PhD student in the School of Education at University College Dublin.

Suzanne Parkinson

Suzanne Parkinson is an Educational Psychologist at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick. Winner of the Psychological Society of Ireland 2020 Member’s Contribution to Psychology Practice Award for her work on the development of the ‘My Learner ID’ series, Suzanne has interrogated the concept of learner identity and sought to actualise its application within educational contexts.

References

- Bayraktar-Erten, N., and I. H. Erten. 2014. “Academic Self-Concept and Students’ Achievement in the Sixth Grade Turkish Course: A Preliminary Analysis.” International Online Journal of Education and Teaching 1 (2): 46–55.

- Black, P, R Mccormick, M James, and D Pedder. 2006. “Learning how to learn and assessment for learning: A theoretical inquiry.” Research Papers in Education 21 (02): 119–132.

- Burden, R. 1998. “Assessing Children’s Perceptions of Themselves as Learners and Problem-Solvers.” School Psychology International 19 (4): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034398194002.

- Chalk, K., and L. A. Bizo. 2004. “Specific Praise Improves on-Task Behaviour and Numeracy Enjoyment: A Study of Year Four Pupils Engaged in the Numeracy Hour.” Educational Psychology in Practice 20 (4): 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736042000314277.

- Coll, C, and L Falsafi. 2010. “Presentation. Identity and education: tendencies and challenges.” Revista de Educación 353: 29–38.

- Council for Curriculum, Examinations, and Assessment. 2007. The Northern Ireland Curriculum Primary. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Council for Curriculum, Examinations, and Assessment.

- Department of Education. 2023. Primary Curriculum Framework: For Primary and Special Schools. Dublin, Ireland: Department of Education.

- Department of Education and Science. 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Introduction. Dublin, Ireland: The Stationary Office.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2015. Framework for Junior Cycle. Dublin, Ireland: DES.

- Erten, I. H. 2015. “Validating Myself-as-a-Learner Scale (MALS) in the Turkish Context.” Research on Youth and Language 9 (1): 46–59.

- Erten, I. H., and R. L. Burden. 2014. “The Relationship between Academic Self-Concept, Attributions, and L2 Achievement.” System 42: 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.01.006.

- European Commission. 2006. Key Competences for Lifelong Learning: A European Reference Framework. Luxembourg, Luxembourg: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2018. Proposal for a Council Recommendation on key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Luxembourg, Luxembourg: European Commission.

- FitzPatrick, S., M. Twohig, and M. Morgan. 2014. “Priorities for Primary Education? From Subjects to Life-Skills and Children’s Social and Emotional Development.” Irish Educational Studies 33 (3): 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2014.923183.

- Hale, T., N. Angrist, R. Goldszmidt, B. Kira, A. Petherick, T. Phillips, S. Webster, et al. 2021. “A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker).” Nature Human Behaviour 5: 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8.

- Kolb, A, and D Kolb. 2009. “On becoming a learner: The concept of learning identity.” In Learning Never Ends: Essays on Adult Learning Inspired by the Life and Work of David O, edited by D. Bamford-Rees, B. Doyle, B. Klein-Collins, and J. Wertheim, 5–13. Chicago, IL: CAEL Forum and News.

- Lee, W. O. 2014. “Lifelong Learning and Learning to Learn: An Enabler of new Voices for the new Times.” International Review of Education 60 (4): 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-014-9443-z.

- McGuinness, C. 2018. Research-informed Analysis of 21st Century Competencies in a Redeveloped Primary Curriculum. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Queen’s University Belfast.

- Ministry of Education. 2007. The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media Limited.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2009. Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. Dublin, Ireland: NCCA.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2012. Priorities for Primary Education? Report on Responses to ‘Have Your say.’. Dublin, Ireland: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2018. Primary Developments: Consultation on Curriculum Structure and Time. Dublin, Ireland: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2019a. Primary Curriculum Review and Redevelopment: Report of Main Findings from Parents on the Review and Redevelopment of the Primary Curriculum. Dublin, Ireland: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2019b. Early Childhood and Primary Developments. Consulting with Children: Child Voice in Curriculum Developments. Dublin, Ireland: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2020. Draft Primary Curriculum Framework. Dublin, Ireland: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2005. Definition and Selection of Competencies: Executive Summary. Paris, France: OECD.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Paris, France: OECD.

- Parkinson, S., and F. Brennan. 2020. “Exploring the Positioning of Educational Psychology Practice in 21st Century Learning.” DECP Debate 1: 16–22. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsdeb.2020.1.175.16.

- Parkinson, S., F. Brennan, S. Gleasure, and E. Linehan. 2021. “Evaluating the Relevance of Learner Identity for Educators and Adult Learners Post-COVID-19.” Adult Learner 9: 74–96.

- Pirrie, A., and E. D. Thoutenhoofd. 2013. “Learning to Learn in the European Reference Framework for Lifelong Learning.” Oxford Review of Education 39 (5): 609–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.840280.

- Radovan, M. 2019. “Cognitive and Metacognitive Aspects of key Competency “Learning to Learn”.” Pedagogika 133 (1): 28–42. https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2019.133.2.

- Sangawi, H., J. Adams, and N. Reissland. 2018. “The Impact of Parenting Styles on Children Developmental Outcome: The Role of Academic Self-Concept as a Mediator.” International Journal of Psychology 53 (5): 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12380.

- Thoutenhoofd, E. D., and A. Pirrie. 2015. “From Self-Regulation to Learning to Learn: Observations on the Construction of Self and Learning.” British Educational Research Journal 41 (1): 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3128.

- Waeytens, K., W. Lens, and R. Vandenberghe. 2002. “‘Learning to Learn’: Teachers’ Conceptions of Their Supporting Role.” Learning and Instruction 12 (3): 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00024-X.

- Walsh, T. 2016. “100 Years of Primary Curriculum Development and Implementation in Ireland: A Tale of a Swinging Pendulum.” Irish Educational Studies 35 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1147975.