ABSTRACT

Distributed leadership is currently to the forefront of emerging educational leadership literature, policy, and practice. It is suggested that the pressures exerted on schools during the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in distributed leadership becoming a default leadership style in schools. The adoption of a distributed leadership approach is supported by Irish school policy, yet little is known about its implementation. The aim of this study was to map the current state of distributed leadership in Irish post-primary schools from the perspective of school personnel. Data were collected from 337 participants using an online survey comprising Likert-type statements complimented with open-ended questions. Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis were used to analyse the data. Findings reveal disparities specific to how distributed leadership is implemented in schools, (if at all), including the division of labour, the impact of culture and complexities in relationships among staff. In this paper, recommendations are made regarding the need to further conceptualise the culture required for distributed leadership to flourish, the division of labour, and teacher leadership in a distributed leadership approach, as well as a focus on building positive relationships.

Introduction

While distributed leadership is reportedly the most popular school leadership theory internationally, Harris (Citation2020) notes that prior to the pandemic, traditional leadership styles were more commonly implemented in schools. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused ‘undeniable chaos’ (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2020, 334) for schools. Yet, distributed leadership is said to have become the default leadership style through necessity as a result of the pandemic (Harris and Jones Citation2020).

Distributed leadership is a form of shared leadership that is spread across leaders and followers with importance given to the interactions between these actors and their situation (Spillane Citation2005). It has become embedded in policy internationally (Harris Citation2011), and has superseded assumptions of solo leadership (Crawford Citation2012). Distributed leadership has been the cause of much debate in the field of educational leadership (Harris Citation2011). For example, Lumby (Citation2019) calls the power dynamics of a distributed model of leadership into question and Grint (Citation2010, 136) draws attention to the ‘romance of leadership’, whereby it is assumed that distributed leadership can solve all organisational issues, even though questions around the effectiveness of distributed leadership are prevalent. It has been critiqued as a potential case of the ‘emperor’s new clothes’ (Bolden Citation2011, 254) and its practical enactment has also been questioned by Leithwood et al. (Citation2007) who suggest that the more diffuse leadership is in an organisation, the more potential to detract from clarity of purpose in a school. Nonetheless, distributed leadership has been praised for its positive relationship with organisational commitment and school improvement (Hickey, Flaherty, and Mannix McNamara Citation2022) and significant interest in the construct remains (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022). Due to some of these tensions, Mifsud (Citation2023) argues that more problematisation of the concept in both theory and practice is required.

Theoretical underpinnings of distributed leadership

It is important to revisit the theoretical underpinnings of distributed leadership as Jambo and Hongde (Citation2020) describe the continued challenges regarding the conceptual differences in the way in which we write about the construct. Distributed leadership has theoretical roots in activity theory and distributed cognition (Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond Citation2001). Distributed cognition refers to cognition and knowledge as distributed across a social group (Hutchins Citation2000), while activity theory ‘is a conceptual framework based on the idea that activity is primary, that doing precedes thinking, that goals, images, cognitive models, intentions, and abstract notions like “definition” and “determinant” grow out of people doing things’ (Morf and Weber Citation2000, 81). Bertelsen and Bødker (Citation2003) report activity theory to be unique as it ‘understands human conduct as anchored in collective/shared practice, it addresses more than just individual skills, knowledge, and judgment’ (293–294). Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond (Citation2001) who along with Gronn (Citation2000) garnered interest regarding distributed leadership in the field of educational leadership (Youngs Citation2020), used this framework to describe the interdependence of individuals and their environment and how human activity is distributed between people, artefacts, and the situation. This activity theory framework forms the basis for the concept of distributed leadership involving leaders, followers, and their situation, and is as such, an activity system influenced by the division of labour, tools, rules, and community.

Context of the study

Irish national policy currently promotes a distributed leadership model (Department of Education and Skills Citation2018; Department of Education Citation2022) and given that this is a recent policy development, its impact is still being explored. In Ireland, senior school leadership comprise the principal and deputy principal(s). Middle leadership positions constitute those in the position of assistant principal I (API), and assistant principal II (APII). These roles are also referred to as posts of responsibility and the roles of each API/APII are determined by the needs of the school. These positions are filled through the completion of competency-based interviews.

There has been a movement towards shared leadership in schools in Ireland since the 1990s (Lárusdóttir and O'Connor Citation2017), however, such progression has been slow due to the traditionally hierarchical nature of Irish school structures (O'Donovan Citation2017). Many believe that progress towards a shared model of leadership has been delayed due to the moratorium on middle leadership positions (Lárusdóttir and O'Connor Citation2017). This constituted the loss of over 5,000 middle leadership posts in 2009 resulting in few career progression opportunities. In 2017, 1300 posts were restored and a further 1,400 posts restored in 2022. Furthermore, the demands on schools during the COVID-19 pandemic may further influence the movement towards distributed practices (Harris and Jones Citation2020). The closure of schools had a significant impact on teaching and learning as well as administration and leadership structures as the COVID-19 pandemic has caused ‘undeniable chaos’ in schools (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2020, 334).

Brown et al. (Citation2019) suggest that distributed leadership is a ‘vital first step in making schools flexible enough to respond to new pressures’ (457) and advocate the need for ‘distributed culturally responsive leadership’ to both enable schools to quickly respond and adapt to challenges, changing policies and practices while remaining focused on social justice for an increasingly diverse pupil population. However, some obstacles to implementation have emerged. Prior to recent change in policy, Humphreys (Citation2010) explored distributed leadership and its impact on teaching and learning whereby participants were found to have a wide range of understandings of distributed leadership. O'Donovan (Citation2017) has also found that distributed leadership is not explicitly part of the discourse of schools and that lack of visibility of the construct poses challenges for both school leaders and policy makers.

Furthermore, the traditional individualised culture of teachers operating behind a ‘closed door’ in Irish schools is a challenge for school leaders. O'Donovan (Citation2017) found principals express a reluctance to challenge this culture. Lárusdóttir and O'Connor (Citation2017) also suggest that there are inherent practical issues and difficulties with implementing distributed leadership. They discuss the tension present when implementing a decentralised practice in a centralised hierarchy and outline the potential of distributed leadership as little more than a polished version of delegation (Lárusdóttir and O'Connor Citation2017). It is within these varied perspectives and times of change that this study was conducted.

Purpose of study

An Irish circular (written statement providing information on laws and procedures) from the education ministry entitled School Leadership and Management in Post-primary Schools (Department of Education and Skills Citation2018) encourages the adoption of distributed leadership models in post-primary schools. Since the release of this document, there has been little exploration of the perceived implementation of distributed leadership in schools. Therefore, we aimed to map the state of distributed leadership in Irish post-primary schools through exploring the perceptions of school personnel towards distributed leadership implementation. This was achieved through the exploration of the research question how is distributed leadership being practiced in Irish post-primary schools? It is hoped that the findings of this study will add to the national and international body of literature and help to inform future school leadership policy and practice.

Methods

Post-primary school personnel currently working in Ireland were invited to complete a two-part survey comprising Likert-type statements and open-ended questions relating to distributed leadership. The first part of this survey explored school personnel’s interpretations of distributed leadership (Hickey, Flaherty, and Mannix McNamara Citation2023), while this paper reports on the second part of the survey relating to Likert-type statements and open-ended questions relating to distributed leadership practices. The Likert-type statements were analysed using descriptive statistics, while the open-ended questions were analysed using thematic analysis.

Instrument

The survey used in this study is an adapted version of the Distributed Leadership Inventory (DLI) developed by Hulpia, Devos, and Rosseel (Citation2009). Permission to use and modify this instrument for the purpose of this study was sought by the researchers and granted by the survey author. This survey was amended to include those working in schools but who do not have formal leadership roles. As a result, the wording of some statements were changed, statements were added and removed and some open-ended questions were also added to gain participants’ spontaneous responses (Reja et al. Citation2003) without being influenced by the researcher (Foddy Citation1993). Demographic questions were also added including questions about the participants’ gender, age, role in the school, school type etc. These demographic questions were kept to a minimum to ensure anonymity.

A total of 21 Likert-type statements were presented to participants, whereby they were asked to denote whether they strongly agree, agree, are undecided, disagree or strongly disagree with the statements in question, followed by open-ended questions. The amended survey is not deemed to take the form of an instrument to measure the implementation of distributed leadership, but rather is used as a tool to gain insight into various aspects of distributed leadership.

Reliability and validity

As the instrument was amended, the researchers carried out various reliability and validity appraisals. Three experts in the field were asked to provide feedback on the amended survey. A pilot study using the amended survey was also completed with a convenience sampling of thirty-one participants. Here, each participant was asked to fill out the survey and Cronbach’s Alpha values were calculated for each of the three sections of the Likert-type questions. Participants were also asked to provide additional feedback on the structure of the survey, the wording of the statements, and questions contained within it. The findings of the pilot study gave insight into improving the accessibility of the survey and identifying an average time required to complete it. Interviews were also conducted with three of the pilot participants to gain further insight into their understanding of the questions and further improve the reliability and validity of the survey. Changes made to the survey included minor changes to phrasing and the removal of some statements that were deemed less relevant. The finalised version of the survey comprised three sections: (i) Organisational Culture and Climate, (ii) Capacity Building and Empowerment, and (iii) Support and Supervision. These sections were reported to have Cronbach’s Alpha values of 0.898, 0.860, and 0.917 respectively.

It was found in the first part of this survey, that participants had differing interpretations of distributed leadership which is reported on in detail elsewhere (Hickey, Flaherty, and McNamara Citation2023). The elusive nature of distributed leadership (Harris Citation2011) can result in differing understandings among participants and potentially impact the subsequent analysis and findings. In order to minimise this, a number of measures were taken. The first step related to the use of multiple approaches to explore the perceived prevalence of distributed leadership. Several open-ended questions were asked relating to leadership activities among different members of the school community. A series of Likert-type statements were used to explore specific elements of distributed leadership practices, only one of which included the terminology of ‘distributed leadership’ itself. Lastly, participants were explicitly asked if they thought distributed leadership was being practiced in their schools. Multiple approaches were utilised to explore the concept from different angles. It is also worth noting that a definition of distributed leadership was provided to participants before any question which mentioned the term explicitly. This definition explained that for the purpose of this study, distributed leadership is the name given to a ‘distributed practice’, whereby school leadership activities are practiced by the whole school community and not just the principal (adopted from Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond Citation2001). However, as Evans (Citation2002) suggests that the provision of a definition to participants is not likely to be effective and instead, it is more useful to build data collection on ‘distinct dimensions of key concepts’ (70), both approaches were taken in order to maximise the chances of achieving construct validity. Lastly, as a final measure, participants were initially asked for their interpretations of distributed leadership which helped to inform the researchers of the nuances in their understandings.

Distribution of survey

The survey was electronically distributed using Qualtrics® which is compliant with the GDPR policy of the researchers’ host institution. An anonymous link to the Qualtrics survey was shared on Twitter and Facebook to recruit participants. School personnel who were currently enrolled in leadership professional development courses within the researchers’ university (N = 312) were also invited to complete the survey and share it with their colleagues. The purpose of this snowball sampling technique was to recruit more participants from a variety of contexts. However, a limitation of this approach is that the researchers are unable to obtain a calculated response rate as well as there being a risk of respondent bias.

Participants

A total of 337 participants completed the online survey. This included post-primary school personnel currently working in Ireland namely principals, deputy principals, assistant principals (I and II), class teachers, guidance counsellors and special needs assistants. As the survey included both Likert-type statements and open-ended questions and not everyone completed both fully, it was decided by the researchers that only responses with fully completed Likert-type statements would be included in the analysis.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Education and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the researchers’ host institution (approval code 2020_05_09_EHS). Participation in the study was voluntary. On opening the survey link, all participants were presented with a consent form which they were required to sign prior to completing the survey. An information sheet was also attached. To ensure anonymity, identifying features of participants and their school were limited to a small number of demographic questions.

Data analysis

The researchers approached this study with the assumption that social reality is ‘shaped by human experiences and social contexts’ (Bhattacherjee Citation2012, 103). As the survey comprises demographic questions, Likert-type questions and open-ended questions, there were two stages of data analysis. The demographic data and Likert-type statements were analysed using descriptive statistics. These are ‘the numerical procedures or graphical techniques used to organise and describe the characteristics or factors of a given sample’ (Fisher and Marshall Citation2009, 93). The open-ended questions were analysed using thematic analysis, informed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2008). This ‘is a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2008, 79) that enables the researcher to ‘see and make sense of collective or shared meanings and experiences’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2012, 57). The six-step model of Braun and Clarke (Citation2008) was followed using a reflexive approach as intended by the authors (Braun, Clarke, and Hayfield Citation2022). Data were first explored question by question and subsequently explored participant by participant.

Within this reflexive approach, Braun and Clarke suggest that it is important to outline the researchers’ positionality and underlying assumptions. All three researchers are qualified post-primary school teachers and therefore, have experience in the school context. One of the researchers is also an experienced school leader. This study is anchored in an interpretivist approach which is typically associated with qualitative research, however it can also be used for mixed methods (McChesney and Aldridge Citation2019). It is important to note that the Likert type statements used within the data collection for this study are not designed to be a measurement of distributed leadership, but rather to gain insight into specific elements of distributed leadership which would be difficult to do via qualitative methods. As distributed leadership is a ‘variegated’ concept, it is important to be clear about the location of research in the area (Youngs Citation2022). In this case, the work is situated within the ontological and epistemological assumptions that there are multiple realities in which the researchers could explore the subjective interpretations of participants.

Results

Variety in the perceived implementation of distributed leadership is evident in the results of this study. The demographic data of participants are first presented, outlining background information of participants. Descriptive statistics of the Likert-type statements are presented followed by a series of themes generated during data analysis to explain the disparities in how distributed leadership was implemented, if at all. These themes comprise: (i) the influence of school culture on distributed practices, (ii) the division of labour among staff, (iii) the complexity of relationships between staff, and (iv) the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on distributed practices.

Demographic data

Participants comprised post-primary school personnel of different genders, ages, qualifications, roles, years teaching experience, school type and location. A full breakdown of participants’ demographic data can be seen in .

Table 1. Demographic data.

Descriptive statistics of Likert-type statements

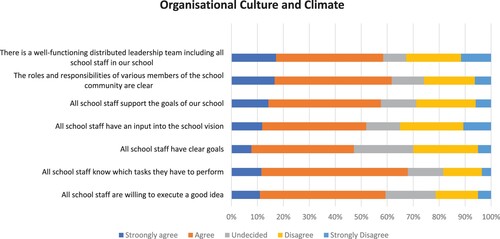

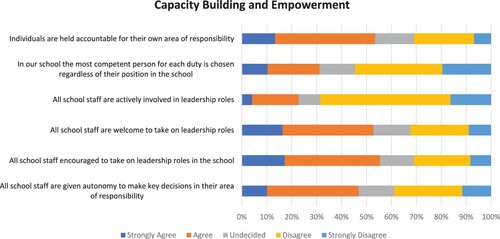

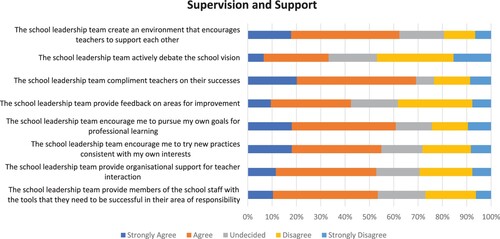

The 21 Likert-type statements were analysed using descriptive statistics to denote the number of responses and corresponding percentages that aligned themselves with each response on the Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). The data can be seen in full in below which illustrate the descriptive statistics for each of the three survey sections.

Implementation of distributed leadership

There was generally a positive response from participants towards the implementation of distributed leadership in their schools as can be seen in . The mode response for 18/21 of the statements showed that participants agreed with aspects relating to distributed leadership implementation in their school. These statements related to organisational culture and climate, capacity building and empowerment, and supervision and support. This is an encouraging finding for the implementation of the practice as the statements were written positively regarding either the concept of distributed leadership itself or characteristics associated with it. For example, the mode response was positive for the following statements: the majority of participants agreed that 'there is a well-functioning distributed leadership team including all school staff in [their] school’, ‘all school staff know which tasks they have to perform’, and ‘the school leadership team provide members of the school staff with the tools that they need to be successful in their area of responsibility’.

The remaining three statements had a mode response of ‘disagree’. This included 55% (n = 184) of participants disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the statement; ‘in our school the most competent person for each duty is chosen regardless of their position in the school’. Sixty-nine percent (n = 231) of participants disagreed or strongly disagreed that ‘all school staff are actively involved in leadership roles’. Finally, 47% (n = 158) of staff disagreed or strongly disagreed that ‘the school leadership team actively debate the school vision’ in their school.

While 58% (n = 197) of participants strongly agreed or agreed that there is a well-functioning distributed leadership team including all school staff in their school, in comparison to 33% (n = 110) who disagreed or strongly disagreed, participant responses were quite varied when asked if distributed leadership was practiced in their school including specific examples. Some participants perceived there to be ‘lots of opportunities to step up and lead out new initiatives’ (API). They believed that ‘staff voices are heard’ (API) and that staff ‘are encouraged to take on various roles that help develop school vision’ (teacher). Other participants reported that their school is ‘moving towards it’ (teacher) or that ‘the intention is for there to be distributed leadership’ (teacher). In some instance, the principal was reported to ‘meet resistance’ (SNA). Others mention that ‘in theory it is [implemented]. However, in practice the principal controls everything allowing for little autonomy’ (APII), or that ‘although leadership appears to be distributed. It is transactional – tick the box’ (API).

It was also reported by other participants that distributed leadership was not implemented within their school. Many reasons were offered for this including, unwillingness to share leadership and lack of shared decision making, i.e. ‘there is a lot of fake collaboration but decisions are actually already made’ (APII). These disparities in perceived implementation of distributed leadership can be described through four themes that were generated from the data. These themes related to the influence of school culture, the division of labour, complexity of relationships among staff, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The influence of school culture on distributed practices

School culture appeared to influence distributed leadership practices in both positive and negative ways. Several comments were made regarding the culture of leadership including the idea that the leadership culture is ‘quite formal’ (deputy principal), or ‘principal led’ (SNA). Some participants reported that the culture is ‘growing’ (API) or ‘evolving’ (principal) and that they are ‘gradually changing from a top only leadership to a more distributed leadership’ (API). Other participants noted somewhat paradoxical cultures for example: ‘it can be a bit of a dictatorship but at the same time encouraging people to come forward for leadership roles’ (teacher) as well as conditional positives e.g. ‘room for improvement. Some good elements but sometime support depends on who the actor is’ (teacher).

Positive school cultures were also described, many of which included a focus on sharing leadership and building leadership capacity. For example, the school culture was described as ‘very positive. Majority of staff engaged and willing to take on responsibilities outside of their classroom duties’ (principal). An openness among staff to take on leadership activities was praised along with the idea of school culture being ‘collaborative, open, encouraging and flexible’ (principal). The enactment of a culture where staff have a voice and are respected and appreciated was also described as ‘one where staff are valued, and they value themselves as professionals. They have a voice and are encouraged to build their leadership capacity by genuinely leading’ (principal). Additional affirmative comments included descriptions of the school culture as ‘excellent. All forward thinking and progressive’ (teacher), ‘holistic’ (unknown), ‘open and approachable’ (teacher), and ‘strong and fair’ (SNA).

Contrarily, negative school cultures were also reported. The culture of leadership in the schools was noted as ‘competitive’ (API) and ‘post driven’ (teacher). Further to this, a reluctance among staff to take on additional leadership roles even when they are encouraged was reported. For example, one participant noted that ‘in [their] school, there is still a slight culture of “that’s not my post”, specifically amongst older staff members’ (deputy principal). On the other hand, it was also noted that some ‘postholders are not doing the jobs given’ (teacher). Some participants noted very negative experiences within their school culture and described it as ‘toxic beyond belief’ (SNA) with another participant stating that ‘bullying is rife’ (teacher).

The division of labour among staff

The way in which labour or workload is shared among school personnel is noteworthy in this study. The leadership activities of the principal, deputy principal, and assistant principal posts noted by the participants were relatively consistent. However, there were some inconsistencies regarding the leadership activities of class teachers.

The leadership activities of principals were reported to include general administration, finances, and timetabling. Principals were seen as the ‘figure head’ (APII) and reported to liaise with ‘community and stakeholders’ (teacher) as well as ‘managerial bodies outside of the school’ (teacher), staff, parents, and the board of management. Their role was seen as ‘managerial’ with responsibility for discipline, staffing, planning and policy development. Principals were reported to both create and share the school vision and were responsible for ‘making the final decision on things’ (APII). Similar to the principals, the deputy principals were reported to carry out the ‘day to day running of the school’ (APII) and have a management role. Deputy principals were seen to ‘work with principal’ (API) or ‘support the principal’ (teacher). The most common specific leadership practices noted were ‘discipline and behavioural issues’ (teacher), ‘supervision and substitution’ (API) and ‘timetabling’ (teacher). Like the principals, they were seen to have ‘administrative duties mainly’ (APII).

Assistant principals are ‘assigned a specific role’ (teacher) based on the ‘needs and wants of the school’ (teacher). This activity can be based on ‘their own areas of expertise’ (API) and are ‘reviewed and changed regularly’ (API). They were seen to support the principal and the deputy principal. The most common leadership activity carried out by APIs was the role of year head. Other roles mentioned included transition year coordinator, mentoring, academic monitoring, as well as roles in wellbeing, discipline, school self-evaluation and information and communication technology (ICT). Some participants responded that APIs ‘almost do nothing for their duties’ (APII), while others were said to do everything. Similar to that of APIs, APIIs were reported to enact their assigned roles. Some participants described them as ‘identical to APIs’ (API). Their main duties were noted to be exam secretary, health and safety, and ICT. While a smaller number of responses noted APIIs to be year heads, it was more common for them to act as class tutor or substitute year head. However, several participants stated that for APIIs there are ‘no clear duties given’ (unknown) or that they are ‘not sure who it is’ (SNA).

Responses regarding the leadership activities of class teachers were more divisive and could be largely separated into classroom duties and additional leadership duties. Within their classrooms, teachers were seen to ‘lead classroom learning’ (API), manage ‘student work and behaviour’ (teacher) and assessment. Class teachers are ‘driving curriculum delivery’ (APII). They were also seen to have a significant pastoral role. While some participants reported that class teachers have ‘very little extra participation’ (teacher) in leadership activities, and ‘just teach and stay in their lane’ (teacher) with ‘no leadership roles’ (teacher), others were reported to take on additional leadership duties which were ‘voluntary duties such as green schools’ (deputy principal). These additional duties were often department specific and related to ‘subject planning’ (teacher). Many participants reported teachers having ‘class tutor roles’ (API) and being involved in extra-curricular activities. Some teachers were reported to work in groups or committees, for example in a literacy team or digital working group and carry out administrative duties such as monitoring attendance, punctuality, and uniform.

Complexity of relationships between staff

The results show complexity in the relationships among staff and their apparent attitudes towards one another. In many instances, positive relationships among staff were described. Comments were made that staff ‘are all working as a team’ (teacher) with everyone being ‘supportive of each other’ (teacher). However, the senior leadership team were on the receiving end of much criticism for various aspects of their leadership, suggesting potential damaged relationships between the senior leadership team and other staff members. A ‘disconnect between “the office” and staff’ (API) was perceived by some participants. Participants reported on several occasions that school principals do ‘everything’ (APII) in the school with an ‘endless list’ (teacher) of leadership activities. This was not always viewed positively as some participants suggested that the principal ‘doesn’t share enough of the responsibility’ (API). Leadership was perceived to not be shared as the ‘principal finds it difficult to delegate and empower people to lead’ (API) or else ‘the principal micromanages everything’ (teacher). The opposite was also noted with some principals perceived to do ‘very little’ (API). One participant stated that their principal ‘duck and dives and blames DP for any shortcomings’ (SNA), while another ‘delegates all jobs’ (teacher).

Further relational issues were noted as participants expressed that leadership was ‘unevenly distributed with power residing with a small number of individuals’ (SNA). Favouritism and cliques were described on multiple occasions with a climate of ‘us and them’ (API) expressed. For example, one APII described the situation as:

very frustrating. Opportunities are open to the favourites and those in the clique only, and initiatives are then fully backed and promoted by smt [senior management team]. Not the case for most staff. No backing, support or recognition of initiatives. (APII)

very closed off and excludes SNAs. We are not included in meetings, we do not receive circulars that are meant to be brought to our attention. If we’ve an idea, we are dismissed and very much aware we need to stay within our boundaries. (SNA)

Authoritative direction, often leading through fear. Repercussions are often a change in timetable /subjects taught the following term. Reprimand all staff for one person’s mistakes. A lack of acknowledgment of the positive things being done, more focus on the negatives. (guidance counsellor)

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on distributed practices

Varying responses on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the distribution of leadership practices in schools were reported. Several participants stated that COVID-19 did ‘not really’ (APII) influence the distribution of leadership practices in their school, or if it did, the changes were minimal. This appeared to be true if distributed leadership practices were deemed to be both effective and ineffective prior to the pandemic. Participants appeared to positively report ‘everyone still doing their roles and responsibilities’ (teacher) but perceived negative leadership practices were also deemed to continue during the pandemic as another participant reported that the ‘principal still dictates everything’ (SNA).

Other participants acknowledged that COVID-19 had an impact on the distribution of leadership practices in their school in either a positive or negative way. Positive impacts included the idea that there has been ‘more collaboration’ (API), and it ‘has created opportunities’ (principal). These additional opportunities mostly related to the Lead Representative Worker, and the need for increased ICT supports. The importance of distributed leadership was also highlighted. The pandemic enhanced the need for distributed practices, and one participant noted that ‘everyone [was] willing to help’ (teacher) during the COVID-19 crisis. One principal shared their development in understanding of the need for distributed leadership based on the impact of COVID-19. They stated that ‘the penny dropped! I couldn’t handle the load alone and needed to share it out, albeit a little late!’ (principal).

While some participants reported the positive impacts of COVID-19 on the distribution of leadership, there were also perceived negative impacts of the pandemic on shared leadership practices. Participants noted that there was ‘very little communication’ (APII) in their schools and ‘all decisions were made with no input from teachers or APII postholders’ (APII). Some participants suggested that the pandemic resulted in school life becoming ‘more authoritarian’ (teacher). Another impact noted was the ‘lack of opportunity to meet physically’ (APII) as well as a ‘lack of collaboration’ (deputy principal). This resulted in leadership becoming ‘more centralised’ (API), that ‘it has made the divide between management and staff even greater’ (APII) and that ‘cliques [have] got tighter’ (APII). Some leadership activities and roles were paused as participants stated that they ‘are just getting through each day and the unknown’ (teacher). Overall negative comments further included that ‘there is significantly more work to do’ (APII), ‘less autonomy given to teachers’ (guidance counsellor), there are ‘less opportunities to lead’ (guidance counsellor), and there is a ‘reinforced hierarchy’ (deputy principal) whereby the senior leadership team are being forced to make quick decisions involving little or no staff consultation.

Discussion

Irish post-primary school personnel’s perceptions of the prevalence of distributed leadership in their schools is varied. The school culture, division of labour, and professional relationships among staff were identified as factors that influence the implementation of distributed leadership. The following discussion will explore the need to further conceptualise school culture and the division of labour within distributed leadership practices as well as focus on the importance of building positive relationships. The potential danger for distributed leadership to become a ‘tick-the-box’ exercise will also be discussed.

Conceptualising the culture required for distributed leadership

School culture has been noted to play an important role in the success of distributed leadership (Harris Citation2008). Culture can be defined as the ‘enduring sets of beliefs, values and ideologies underpinning structures, processes and practices which distinguishes one group of people from another’ (Dimmock and Walker Citation2000, 146). There is a concern about the inclusion of the non-hierarchical nature of distributed leadership within the formal school structure (Hartley Citation2010). In order for distributed leadership to be implemented effectively in schools, a cultural move away from the top-down model of leadership is required (Harris Citation2008).

Lack of supportive culture has been attributed for the withering of reforms (Peterson and Deal Citation1998) and there is a risk that distributed leadership will face a similar outcome if due consideration is not given to the type of school culture needed for distributed leadership to flourish. While many participants in this study reported positive, collegial, and empowering cultures in their schools, other participants outlined hierarchical structures that are not conducive to shared models of leadership. In some instances, the culture was described as toxic, and school leaders were described as bullies. This type of culture can be detrimental to schools (Mannix-McNamara et al. Citation2021) and is not conducive to a distributed model of leadership.

Some participants described the structure of posts of responsibility as contributing to a competitive culture in schools where individuals focus on attaining these posts rather than the general practice of leadership in the school. This actively works against the principles of distributed leadership focusing on the practice of leadership rather than the individual who is leading (Spillane Citation2005) and creating a culture of ‘us and them’. This leads to a slightly different structure, where individuals acknowledge that leadership does not reside with just the principal, but is still problematic for distributed leadership in viewing leadership as an activity that remains owned by individuals, rather than an ‘organisational resource that is maximised through individuals and teams’ (Harris Citation2008).

A cultural shift away from the traditional individualised nature of schooling in Ireland to a more open and flexible culture is needed for distributed leadership to occur. The data in this study suggests that school culture that is open, collaborative, encouraging, and flexible is conducive to distributed leadership. Whereas competitive school cultures that are perceived to lack transparency and exhibit favouritism have the opposite effect. Authoritarian school cultures with cliques and exclusion stem distributed leadership from occurring. Some of these challenges appear to be embedded in power dynamics which distributed leadership has been critiqued for potentially abusing (Lumby Citation2019). The cultural impact of including a shared leadership practice in a hierarchical structure is complex. Depending on its nature, a school culture can be supportive or damaging to the distribution of leadership within schools. While this study offers some initial insight, the culture that is required for distributed leadership to flourish requires further conceptualisation and its influence explored further.

Conceptualising how labour is divided in a distributed leadership model

Spillane (Citation2005) draws heavily on activity theory to describe distributed leadership as a product of the interactions between school leaders, followers, and their situation. In Engeström’s (Citation1999) model of activity theory, he outlines the division of labour as a mediator of activity. The results of this study suggest variances in the way in which labour is divided, suggesting the need for greater clarity regarding the division of labour in distributed leadership models.

While the spread of leadership activities was evident in the results of this study, perceived inequality of access to opportunities was also evident among responses. Some participants noted that the same individuals are consistently provided with opportunities to lead while others are not. A total of 55% (n = 184) of participants disagreed or strongly disagreed that the most competent person for each duty is chosen regardless of their position in the school. Perceptions that an individual is chosen for a role for any reason other than their competency for that role suggests underlying beliefs that leadership is not being spread over the organisation or that there is a potential for favouritism which has previously been reported as a concern for distributed leadership (Murphy et al. Citation2009). This concern is echoed in the results presented in this study.

The statement that all staff are actively involved in leadership roles was disagreed or strongly disagreed with by 69% (n = 231) of participants. While it should not be expected that all staff are leading at all times, this does not fit well with the circular Leadership and Management in Post-Primary Schools which states that ‘every teacher has a leadership role within the school community and in relation to student learning’ (Department of Education and Skills Citation2018, 6), or the definition of distributed leadership whereby leadership is spread over leaders, followers and the situation. This suggests the need to further consider how labour is divided in schools and more specifically within a distributed leadership model.

While in some instances school leaders were perceived to be intentionally restricting the leadership of others, the perception also existed that some staff members do not want to engage in additional leadership if they are not going to receive additional payment. This can be an extremely challenging space for school leaders as they may try to include individuals in school leadership who do not want to be involved. This is increasingly complex as principals come under some criticism for both retaining leadership practices and corresponding power and influence, while also being criticised for sharing all their leadership with others and doing very little themselves. Without clarity on how labour is divided in a distributed leadership model, it can be very difficult for school leaders to navigate this space.

A distinct lack of clarity also remains on what is meant by teacher leadership in the school context. There is a significant difference between class teachers leading within their classrooms and engaging in additional leadership outside of the classroom which has not yet been refined. This leads to confusion and some assumptions about the inclusion of class teachers in a distributed leadership model. It has previously been noted that a task performed by school leaders would be referred to as leadership and labelled teaching if completed by a teacher (Murphy et al. Citation2009). There is a distinct need for concept clean-up of the use of teacher leadership within a distributed framework.

Furthermore, the results of this study particularly highlight the need for recognition of special needs assistants in leadership activities. Some of the special needs assistants that participated in this study described themselves at the ‘bottom of the list in all areas’ and having received ‘little to no communication from anybody in leadership’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. We know that special needs assistants have a ‘broader profile than originally planned’ (Keating and O’Connor Citation2012, 540) and that they play a key role in supporting students’ learning. However, they may also play key leadership roles among staff in advocacy or other leadership activities outside of the pedagogical support they provide. Recognition and enhancement of this via distributed leadership may be a significant step in their inclusion among staff and the school community.

Building positive relationships

Staff relationships can have an impact on many aspects of school life including influence on school climate, and acting as a connecting bridge for students and the overall school community (Back et al. Citation2016). Within this study, there were many statements suggesting that relationships among staff could be adversely impacting distributed leadership practices. This was reported due to perceived favouritism, a divide between senior management and other staff, a sense that some staff members are deemed more important than others, poor communication, or everyone not being on the same page regarding distributed leadership practices. The importance of relationships in a distributed practice is not surprising as community, referring to a group of people sharing a common objective (Ho, Victor Chen, and Ng Citation2016), is an important element of activity theory which underlines distributed leadership. However, it appears that this may be a gap that requires further consideration within schools. Distributed leadership requires school staff to work together (Harris Citation2008) which is very difficult if sufficient attention is not given to building positive relationships among staff in advance of distributing leadership practices. It is hence suggested that time to build and sustain positive working relationships requires further attention in distributed leadership practices in Irish post-primary schools.

Threat of ‘tick the box’ distributed leadership

It is evident that many post-primary schools in Ireland are implementing distributed leadership practices to various degrees in their schools. This included the sharing of opportunities to lead among staff, collaborative decision making, and the voices of everyone being heard and considered. The environment within these schools were in turn described by participants as supportive, holistic, and collaborative.

However, a trend emerged in the data suggesting that distributed leadership might be surface work in some schools, while remaining hierarchical in reality. This aligns with the work of Lárusdóttir and O'Connor (Citation2017, 434) who describe the potential for distributed leadership to be ‘little more than a seductive and elegant version of the more longstanding notion of delegation whereby responsibility for completing tasks is passed down the school hierarchy’. Lack of consideration of the organisational structures required to effectively divide labour and create a culture conducive to distributed leadership as well as ineffective working relationships can result in a potential facade of distributed leadership with little practical application of the model. Survey responses report perceptions of the inclusion of distributed leadership as a ‘tick the box’ exercise rather than a framework for effectively leading a school. In several instances, participants perceived fake and false efforts to implement distributed leadership while the perceived reality of school life remains top-down. If this is the case, not only is it not conducive to the implementation of distributed leadership, but it causes additional concern for the field by adding to the notion of distributed leadership as the ‘emperor’s new clothes’ (Bolden Citation2011, 254).

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. While the aim of the study was exploratory in nature, it must be noted that the study is limited in its generalisability. The results provide initial insight into the implementation of distributed leadership in Irish post-primary schools, rather than generalisable results. A study drawing on inferential statistics to explore perceptions of the prevalence of distributed leadership from participants of different demographics including age, gender, school type, years of experience etc. would be valuable in future research, as would a study exploring these topics in specific school settings. The second limitation is that a sample size cannot be calculated for the study due to the nature of snowball sampling as well as a risk of respondent bias. Lastly, the data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic when there was a lot of unrest in schools. While this provides insight into the impact that the virus had on school leadership, it will have affected how participants were thinking about leadership at the time.

Conclusion

The Irish post-primary school leaders, teachers, guidance counsellors and special needs assistants surveyed in this study described varied perceived implementations of distributed leadership practices in their schools. Descriptions of leadership cultures in schools varied significantly from being extremely positive and collegial, to toxic in nature. This warrants the attention of practitioners, researchers, and policy makers. Similarly, COVID-19 was reported in many instances to have a significant impact on the school community. In some cases, this was perceived as a positive change which should be retained and utilised to its full potential, while others reported significantly negative consequences of the pandemic. Either way schools are faced with the challenge of rebuilding schools after the impact of COVID-19, and it is a pivotal time to ensure that they move forward inclusively and positively. Further consideration is required of the type of school culture needed for distributed leadership to flourish as well as the structure for the division of labour. The necessity to focus on building positive working relationships among staff is also evident. Lastly, there is a distinct need for concept clean-up of teacher leadership in the context of distributed leadership to avoid confusion and to progress the practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank those within their institution for their support as well as the Irish Research Council for funding the study. They also wish to thank the subject experts who offered guidance and support, and the school personnel who participated in both the piloting and final data collection phases in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Niamh Hickey

Niamh Hickey is a University Teacher in Education (Leadership) at the University of Limerick, Ireland. She has completed a doctorate in educational leadership which was funded by the Irish Research Council. She is currently researching and lecturing on educational leadership professional development modules at the university.

Aishling Flaherty

Aishling Flaherty is the Course Director for the Professional Masters in Education (Science) at the University of Limerick. She has completed a PhD in chemistry teacher education. Before joining the University of Limerick, she was a post-doctoral research associate in Prof. Melanie M. Cooper’s lab at Michigan State University.

Patricia Mannix McNamara

Patricia Mannix McNamara is Professor (Chair) in Education at the University of Limerick and is currently the Head of the School of Education at the university. She also began her career as a post-primary school teacher before completing her PhD in the examination of supervisory relationships from a critical theory perspective.

References

- Back, Lindsey T, Elizabeth Polk, Christopher B. Keys, and Susan D. McMahon. 2016. “Classroom Management, School Staff Relations, School Climate, and Academic Achievement: Testing a Model with Urban High Schools.” Learning Environments Research 19 (3): 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-9213-x.

- Bertelsen, Olav W., and Susanne Bødker. 2003. “Activity Theory.” In HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks: Toward an Interdisciplinary Science, edited by John M. Carroll, 291–324. San Francisco, CA, United States: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Bhattacherjee, Anol. 2012. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. Vol. 3. Tampa, FL, USA: Textbooks Collection.

- Bolden, Richard. 2011. “Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Research.” International Journal of Management Reviews 13 (3): 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2008. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, edited by Harris Cooper, Marc N. Coutanche, Linda M. McMullen, Abigail T. Panter, David Rindskopf, and Kenneth J. Sher, 57–71. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, and Nikki Hayfield. 2022. “‘A Starting Point for Your Journey, not a Map’: Nikki Hayfield in Conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 19 (2): 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765.

- Brown, Martin, Gerry McNamara, Joe O’Hara, Stafford Hood, Denise Burns, and Gül Kurum. 2019. “Evaluating the Impact of Distributed Culturally Responsive Leadership in a Disadvantaged Rural Primary School in Ireland.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (3): 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217739360.

- Crawford, Megan. 2012. “Solo and distributed leadership: Definitions and dilemmas.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 40 (5): 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143212451175.

- Department of Education. 2022. Looking at Our School 2022: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: The Inspectorate.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2018. Leadership and Management in Post-pimary Schools, 1-30. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Dimmock, Clive, and Allan Walker. 2000. “Developing Comparative and International Educational Leadership and Management: A Cross-Cultural Model.” School Leadership & Management 20 (2): 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430050011399.

- Engeström, Yrjö. 1999. “Expansive Visibilization of Work: An Activity-Theoretical Perspective.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 8 (1-2): 63–93. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008648532192.

- Evans, Linda. 2002. Reflective Practice in Educational Research. London: A&C Black.

- Fisher, Murray J, and Andrea P. Marshall. 2009. “Understanding Descriptive Statistics.” Australian Critical Care 22 (2): 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2008.11.003.

- Foddy, William Henry. 1993. Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Grint, Keith. 2010. Leadership: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: OUP Oxford.

- Gronn, Peter. 2000. “Distributed Properties: A New Architecture for Leadership.” Educational Management & Administration 28 (3): 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211X000283006.

- Hargreaves, Andy, and Michael Fullan. 2020. “Professional Capital after the Pandemic: Revisiting and Revising Classic Understandings of Teachers’ Work.” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5 (3/4): 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0039.

- Harris, Alma. 2008. “Distributed Leadership: According to the Evidence.” Journal of Educational Administration 46 (2): 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810863253.

- Harris, Alma. 2011. “Distributed Leadership: Implications for the Role of the Principal.” Journal of Management Development 31 (1): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711211190961.

- Harris, Alma. 2020. “COVID-19 – School Leadership in Crisis?” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5 (3/4): 321–326. doi:10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0045.

- Harris, Alma, and Michelle Jones. 2020. “COVID 19 – School Leadership in Disruptive Times.” School Leadership & Management 40 (4): 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1811479.

- Harris, Alma, Michelle Jones, and Nashwa Ismail. 2022. “Distributed Leadership: Taking a Retrospective and Contemporary View of the Evidence Base.” School Leadership & Management 42 (5): 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2109620.

- Hartley, David. 2010. “Paradigms: How far Does Research in Distributed Leadership ‘Stretch’?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 38 (3): 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143209359716.

- Hickey, Niamh, Aishling Flaherty, and Patricia Mannix McNamara. 2022. “Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research.” Societies 12 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010015.

- Hickey, Niamh, Aishling Flaherty, and Patricia Mannix McNamara. 2023. “Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations.” Education Sciences 13 (4): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040388.

- Ho, Jeanne Pau Yen, Der-Thanq Victor Chen, and David Ng. 2016. “Distributed Leadership through the Lens of Activity Theory.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44 (5): 814–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143215570302.

- Hulpia, Hester, Geert Devos, and Yves Rosseel. 2009. “Development and Validation of Scores on the Distributed Leadership Inventory.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 69 (6): 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409344490.

- Humphreys, Eilis. 2010. “Distributed Leadership and its Impact on Teaching and Learning.” Ph.D. Maynooth, Ireland: National University of Ireland.

- Hutchins, Edwina. 2000. “International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences.” International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences:2068-2072 138 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01636-3.

- Jambo, Daniel, and Lei Hongde. 2020. “The Effect of Principal's Distributed Leadership Practice on Students’ Academic Achievement: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Higher Education 9 (1): 189–198. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n1p189.

- Keating, Stephanie, and Una O’Connor. 2012. “The Shifting Role of the Special Needs Assistant in Irish Classrooms: A Time for Change?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 27 (4): 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2012.711960.

- Lárusdóttir, Steinunn Helga, and Eileen O'Connor. 2017. “Distributed Leadership and Middle Leadership Practice in Schools: A Disconnect?” Irish Educational Studies 36 (4): 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2017.1333444.

- Leithwood, Kenneth, Blair Mascall, Tiiu Strauss, Robin Sacks, Nadeem Memon, and Anna Yashkina. 2007. “Distributing Leadership to Make Schools Smarter: Taking the Ego out of the System.” Leadership and Policy in Schools 6 (1): 37–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760601091267.

- Lumby, Jacky. 2019. “Distributed Leadership and Bureaucracy.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (1): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217711190.

- Mannix-McNamara, Patricia, Niamh Hickey, Sarah MacCurtain, and Nicolaas Blom. 2021. “The Dark Side of School Culture.” Societies 11 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030087.

- McChesney, Katrina, and Jill Aldridge. 2019. “Weaving an Interpretivist Stance throughout Mixed Methods Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42 (3): 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1590811.

- Mifsud, Denise. 2023. “A Systematic Review of School Distributed Leadership: Exploring Research Purposes, Concepts and Approaches in the Field between 2010 and 2022.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 56 (2): 154–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2158181.

- Morf, Martin E, and Wolfgang G Weber. 2000. “I/O Psychology and the Bridging of A. N. Leont'ev's Activity Theory.” Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne 41 (2): 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088234.

- Murphy, Joseph, Mark Smylie, David Mayrowetz, and Karen Seashore Louis. 2009. “The Role of the Principal in Fostering the Development of Distributed Leadership.” School Leadership & Management 29 (2): 181–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430902775699.

- O'Donovan, Margaret. 2017. “The Challenges of Distributing Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 8 (2): 243–266.

- Peterson, Kent D, and Terrence E. Deal. 1998. “How Leaders Influence the Culture of Schools.” Educational Leadership 56 (1): 28–31.

- Reja, Urša, Katja Lozar Manfreda, Valentina Hlebec, and Vasja Vehovar. 2003. “Open-ended vs. Close-Ended Questions in Web Questionnaires.” Developments in Applied Statistics 19 (1): 159–177.

- Spillane, James P. 2005. “Distributed Leadership.” The Educational Forum 69 (2): 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720508984678.

- Spillane, James P, Richard Halverson, and John B Diamond. 2001. “Investigating School Leadership Practice: A Distributed Perspective.” Educational Researcher 30 (3): 23–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030003023.

- Youngs, Howard. 2020. “Distributed Leadership.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 1–24. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Youngs, Howard. 2022. “Variegated Perspectives within Distributed Leadership: A mix (up) of Ontologies and Positions in Construct Development.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse, edited by Fenwick W. English, 261–281. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.