ABSTRACT

The paper discusses a structured peer mentoring scheme for Early Career Academics (ECAs) in Sociology during COVID-19 and post-Brexit, the pedagogical framework adopted and programme challenges, benefits and learning. Internationally, structured peer mentoring schemes for ECAs are sparse and discussions of ‘what works’ in the context of dedicated peer mentoring programmes for ECAs are limited. This programme, designed and executed by the Sociological Association of Ireland (SAI) and a professional mentoring trainer in 2022, involved 8 peer mentors, all of whom were senior and mid-career academics and 10 mentees comprising PhD students and postdoctoral researchers. It encompassed formative sessions for peer mentors and mentees and a final joint session, which took place online. Subsequently, peer mentors facilitated online peer mentoring sessions, with mentees supporting them to explore, plan and achieve their professional goals. The authors discuss the pedagogical content and active methodologies adopted in relation to reflective practice and knowledge-exchange, whilst illuminating that more investment in and research on structured peer mentoring programmes in Higher Education can lead to better outcomes for ECAs. We underline the potential of similar inter-professional mentoring schemes for ECAs and key learning, which could benefit future programmes.

Introduction

This paper discusses a peer mentoring programme for Sociology Early Career Academics (ECAs) in Ireland, designed and implemented by the Sociological Association of Ireland (SAI), the national professional representative body for sociologists in 2022. The programme genesis was in May 2021 at the SAI national conference, where ECAs commented on the need for greater professional mentoring from Late Career Researchers (LCRs) to optimise career opportunities subsequent to doctoral/postdoctoral training. Some of the principal themes debated at the conference extended discussions amongst SAI executive committee meetings about employment prospects for sociologists in Ireland and internationally, including precarity and ‘brain drain’ within the discipline, precipitated by growing numbers of sociologists seeking employment outside of academia in private sector industries (O'Connor Citation2023). The SAI was also concerned about enhanced professional support for ECAs during COVID-19, which influenced decisions to devise the programme.

Support for a professional mentoring programme led by the SAI was iterated by LCRs and a decision was subsequently taken by the SAI executive to implement the scheme in 2022, led by this paper's second Author (also one of the mentors in the mentoring scheme), in conjunction with the executive and the first Author, a mentoring expert, who designed the pedagogical model and content for mentors and mentees and delivered the training and supervision. They were joined by three academics, all sociologists, who mentored ECAs as part of the scheme. While we found some evidence of peer mentoring schemes for ECAs in other countries, this is the first of its kind scheme in Ireland, explicitly targeted at sociology ECAs. Furthermore, it applied a structured approach to peer mentoring, which is rarely used in mentoring schemes for ECAs in Ireland. The paper outlines extant research on mentoring, illuminating how the SAI peer mentoring scheme was informed by research. Subsequently, we provide insights from our professional opinions as educators and based on informal feedback from participants about dimensions of the scheme that proved more or less effective and could be adopted for future programmes.

International research supports professional peer mentoring schemes, illuminating the positive impacts on ECAs who require career support to navigate the years that directly follow PhD conferral (see, e.g. Merga and Mason Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Schriever and Grainger Citation2019; Boeren et al. Citation2015; Ferguson and Wheat Citation2015). Recent studies show that peer mentoring assists ECAs to foster professional skills, confidence, scholarly productivity, and career advancement, leading to reduced stress and enhanced job satisfaction (see, e.g. Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023; Dore and Richards Citation2024; Mgaiwa and Kapinga Citation2021). Informed by this research, the scheme's overall aim was to facilitate knowledge exchange, mutual learning and critical discussions that would positively affect mentees’ self-confidence, social support, and knowledge of navigating national/international job markets (Dore and Richards Citation2024). This programme emphasised the professional learning of mentors and mentees, conceptualising mentoring as ‘sharing experiences, hardships, and knowledge to help others to grow, advance and carry on a legacy’ (Marino Citation2021, 748). We defined peer mentoring as a consolidated pedagogical practice which fosters professional skill development, confidence, scholarly productivity, career advancement, job satisfaction (Mgaiwa and Kapinga Citation2021) and the learning development of mentees and peer mentors (Fox et al. Citation2010). This definition was embedded in the pedagogical approach of the mentoring programme from design to completion.

The paper aims to discuss the approach adopted in our Peer Mentoring Scheme for Sociology Early Career Academics (ECAs), examine participants’ needs, challenges, and recommended practices, and identify potential improvements. The insights gained from this mentoring scheme are valuable for future Peer Mentoring Scheme for Early Career Academics (ECAs) online programs.

Subsequently, we detail the principal dimensions of this programme, the pedagogical content and approach, which was embedded in reflective practice (RP). We apply critical perspectives on mentoring and reflect on the key learning. In doing so, we focus on ‘what worked’ in relation to the literature and feedback from mentors and mentees, outlining challenges and factors for consideration which may be useful for other ECA mentoring programmes. We discuss implications for extant mentoring research and the benefits and challenges for HEIs concerning ECA mentoring schemes which may yet be implemented.

Project overview: development and context

This pilot peer mentoring scheme was designed and implemented as part of a growing training and support remit of the SAI specifically for PhD graduates and ECAs in research skills, writing and publishing, whilst drawing on an extant mentoring effective approach. The challenges faced by doctoral and postdoctoral sociology researchers are manifold; the prioritisation of STEM by successive government administrations (Government of Ireland Citation2016a), lack of research funding for the social sciences generally, falling enrolments on sociology undergraduate and PhD programmes and pay freezes and austerity. Increases in zero-hour contracts, rising consumer debt, lack of job security, and growing homeless figures severely limit opportunities for new doctoral candidates and graduates.

This mentoring programme was therefore developed as a response to these conditions and concerns amongst the sociological community about the future of our discipline. As part of the programme, mentees received dedicated training delivered by the first Author, who is widely published internationally on peer mentoring (see e.g. Bussu and Contini Citation2022; Atenas et al. Citation2023). We aimed to provide additional support for ECAs beginning their sociological careers and provide a safe space to discuss personal and professional development opportunities with experienced peers. The programme targeted ECAs pursuing doctoral research and/or completing PhD degrees, which may require advice but did not develop strong professional relationships with university departments, established academics or supervisors. The emphasis was on fostering cooperation and support throughout all stages of this 12-month mentoring project. We regarded this initial pilot as crucial for pinpointing significant challenges and effective operational methods, as perceived by mentors, mentees, and ourselves as educators. It also served to identify areas for potential improvement in future programme phases.

The programme design followed internationally recommended practices on mentoring (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Boeren et al. Citation2015; Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021).

The principal aims of this programme, co-devised by the authors in conjunction with the SAI executive, were:

To establish a professional peer-mentoring scheme on behalf of the Sociological Association of Ireland (SAI) with ECAs;

To facilitate mentees’ self-exploration of professional skills and career options;

To support peer mentors to develop mentoring skills and strategies;

To support ECAs in job opportunities, research, publishing, funding, and professional networks.

Planning, development and implementation

In November 2021, the second Author assembled a scholarly team of four sociologists with professional and research interests in mentoring. Two were members of the SAI Executive Committee; another was an educational sociologist, and an expert on youth mentoring subsequently joined. The team convened meetings in 2021 and early 2022 and subsequently sourced a mentoring expert from the UK (Author one). The project lead (Author two) subsequently wrote the mentoring scheme's aims and convened several meetings with the mentoring team concerning Irish sociology contexts and ECA's professional needs.

The project lead (Author two) drafted an email calling for the participation of potential mentors and mentees, which was sent to SAI members. We made a subsequent call two weeks later via email and recruited 8 peer mentors whose professional interests aligned with the project. We requested ECA applicants to write a short letter outlining their professional experiences, research, and what they would like to achieve from the scheme. This application subsequently informed the matching process of mentors and mentees, which was further supported by evidence-based practices. Deng, Gulseren, and Turner (Citation2022) propose, for instance, matching mentors and mentees according to three criteria: deep-level similarities, taking into account the developmental needs of mentees during the matching process, and soliciting input from both mentors and protégés before confirming matches.

We facilitated contact with academic mentors and supported the development of high-quality professional relationships among mentors and mentees through WhatsApp groups, break-out discussions online and encouraging face-to-face meetings. We now discuss the peer mentoring scheme in the context of critical international literature on mentoring and the professional development of ECAs.

Contextualising Irish sociological ECAs in transformations to work and society

Internationally, academic landscapes have changed extensively over the past two decades for ECAs (Johnson and Weivoda Citation2021). They face radically new challenges in forging independent careers in academia and outside of it as a result of global transformations like Brexit, political instability, Artificial Intelligence (AI), neo-liberal ‘creep’ (Lynch Citation2010), work intensification, managerialism, concerns about research impact (Shankar et al. Citation2021) and growing societal uncertainty post COVID-19. This is compounded by the limited availability of tenure-track positions relative to the higher number of PhD graduates globally fuelled by government funding cuts; ‘funding rates by granting institutions are lower as increases in budget fail to keep up with a growing pool of applicants’ (Johnson and Weivoda Citation2021,1). Existing literature corroborates the multiple professional challenges that ECAs face, linked to research and development (Sauermann and Roach Citation2012; Vitae Citation2011), including international mobility (Kehm Citation2007; Mellors-Bourne et al. Citation2013), public engagement (Montgomery, Dodson, and Sonya Citation2014) and teaching performance (Udegbe Citation2016).

Across the world, academic workplaces have become more challenging, technologically oriented, competitive, and diverse, rendering them highly complex in relation to institutional structures, policies and social dynamics (Baker et al. Citation2014). COVID-19 also affected a depletion of financial and human capital resources to support academic skills development for researchers at all career stages (Johnson and Weivoda Citation2021). During lockdowns, for example, ECAs had limited access to study spaces, laboratories and institutions, which precipitated delays in completing research, adversely affecting ECA's personal development, career prospects, and well-being (Boeren et al. Citation2015). Due to online learning, students experienced severe contractions in learning possibilities, especially face-to-face interactions, which further limited job opportunities (Termini and Traver Citation2020). The pandemic was also particularly challenging for ECAs with young children due to intensified domestic and caregiving responsibilities which affected research productivity, especially for women (Gewin Citation2020). In addition, COVID-19 re-entrenched multiple power inequities pertaining to race and technology poverty severely limiting students’ learning during pandemic times (Atenas et al. Citation2023). We argue, with Johnson and Weivoda (Citation2021), that at all stages, but especially during global emergencies, ECAs should have access to peer networks, information about career options, and career-stage opportunities, which effective mentoring programmes can offer.

While ECAs are heterogeneous with regard to their social backgrounds, learning needs, resilience and coping, COVID-19 lockdowns were initiated less than 14 months after Brexit (January 31st 2020). This was significant given the strong public uncertainty in social and political debates on Brexit nationally and internationally, and growing fears about further economic slowdown when Ireland still bears the scars of mass emigration, over-indebtedness and unemployment after the collapse of the ‘property bubble’ in 2008. This was reflected in HE debates, too, on how opportunities for cross-border cooperation could continue post-Brexit (Koch Citation2021), the impact on internationalisation (Courtois and Veiga Citation2020), and graduate employability. For sociology graduates in Ireland, this uncertainty was compounded by the moratorium on hiring lecturing staff in universities after the 2007 financial crash and the predominance of precarious lecturing and research contracts in Irish universities. While small-in-scale, this mentoring programme was not a panacea for employment options, but the emphasis on RP and guidance from LCRs on funding and publishing was significant for professional development (Smith Citation2020).

Mentoring ECAs in new academic landscapes: international research evidence

Mentoring relationships have been academically studied in the last 40 years, yet there is limited literature on how structured mentoring programmes’ impact on ECAs can create an environment conducive to the growth of both mentors and mentees, fostering enduring relationships (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023; Sargent and Rienties Citation2022). Based on Boeren et al.'s (Citation2015) literature review, it is recommended that further research be conducted to refine the conceptualisation of mentoring. Additionally, future research agendas should investigate the effectiveness of formal mentoring programs.

ECAs’ training needs have transformed with regard to outputs, employment opportunities, international networks and knowledge-exchange. Specific peer support is required on research grants, how to conduct research, present at conferences and submit research papers to high-impact international journals (Orlando and Gard Citation2014). ECAs require support post-PhD in generating research impact to elaborate evidence-based policies and practices in their fields and communicate with policy-makers. How to communicate research outcomes for academic audiences and non-academic audiences has also become a vital learning dimension for ECAs, which also requires academic guidance (Merga and Mason Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

Previous studies underline the value of academic peer mentoring relationships for ECAs (Mullen and Forbes Citation2000), as do reports of institutional and academic practices, co-working and networking for supporting ECA's academic and personal development (Baker, Pifer, and Griffin Citation2014).

The existing literature shows the effectiveness of peer mentoring for ECAs developing professional skills, in exploring decisions for short and long-term career advancement (Harker et al. Citation2019) and enhancing feelings of interpersonal support in their career pathways (Oberhauser and Caretta Citation2019). Furthermore, mentorship is associated with a positive self-image, psychological well-being and emotional adjustment among mentees (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Marino Citation2021), along with enhanced research performance and career satisfaction. This current literature guided the initial development and implementation of the scheme, whilst also justifying the importance of mentoring for ECAs generally.

According to previous studies (Merga and Mason Citation2021a, Citation2021b), the first mentors for ECAs are supervisors who support them in achieving their academic research goals far beyond doctoral candidature. A productive relationship that supports ECAs during and after candidature shows significant relative advantages in comparison to students who do not have these relationships beyond their PhD journeys. However, universities and professional associations should provide additional, targeted support for ECAs; not all PhD candidates and supervisors develop positive, trusting relationships (Merga and Mason Citation2021a). This can severely undermine graduates’ prospects for network building and leadership capacity during and post-PhD, effectively limiting progression opportunities (Schriever and Grainger Citation2019).

The contextual character of peer mentoring

Scholarly works illuminate the multiplicity of interlinking factors that substantially reduce or enhance peer mentoring effectiveness depending on context. Not all academic institutions offer pedagogical training during doctoral/postdoctoral programmes, so mentorship is one of the most cost-effective mechanisms to support ECAs (Mgaiwa and Kapinga Citation2021). Recent studies emphasise institutional weaknesses in preparing ECAs to engage in teaching, research, and public service (ibid.). This includes a lack of research on institutional mentorship arrangements and a paucity of formalised peer mentoring systems.

Research also shows that a mismatch of expertise, incompatible personalities, and communication styles have a negative impact on mentoring (Ehrich, Hansford, and Tennent, Citation2004). Research by Straus et al. (Citation2013), with 54 academic researchers, iterates that successful peer mentoring relationships are characterised by clear and reciprocal expectations, personal connections and reciprocity, and mutual sharing of values. Concomitantly, ineffective relationships are frequently based on poor communication, lack of commitment, competition, mentor's inexperience and conflicts of interest (Ibid.). Frequently, mentor and mentee learning needs and expectations are not the same, and mentees require pastoral and academic support during their journeys. Browning, Thompson, and Dawson (Citation2014) highlight that mentees require dedicated workshops, supportive research environments and targeted research career planning. Academic workload and time limitations also affect mentoring provision, with research illuminating that in some circumstances, mentoring may be more aspirational than actual (Merga and Mason Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

Some previous studies show that failure to provide specific training for peer mentors has limited positive effects on mentees (Boeren et al. Citation2015). This concurs with Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs (Citation2021), who argue that academic peer mentors are frequently hampered by a lack of information about peer mentoring resources, tools and best practices, and training opportunities for developing peer mentor identities. Often, academic peer mentors lack opportunities to discuss their mentorship experiences with each other, which impedes their personal development (Pfund et al. Citation2016). According to existing literature (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023), ECAs also require training in mentoring and skills-building. Furthermore, as per previous studies, mentors who are more informed about their roles and practice are frequently more engaged and open to diversity (Straus et al. Citation2013). We incorporated these insights from existing research into the SAI mentoring scheme, thus fostering interconnections to published work.

Pedagogical framework

The SAI peer mentoring scheme is based on a pedagogical model elaborated in academic contexts in the last decade and implemented in Italy, the UK, Ireland and Ecuador in HE (Bussu et al. Citation2016; Citation2018, Bussu and Contini, Citation2022; Atenas et al. Citation2023). The pedagogical model, conceptualised as the StudyCircle Model (Bussu et al. Citation2016, Citation2018), adopts pedagogical practices (e.g. collaborative learning, restorative practices, one-to-one and team coaching, and teacher-as-coach model) (Veloira et al. Citation2020), has been developed for training peer mentors in HE and for building supportive relationships between mentors and mentees. The model developed by Bussu et al. (Citation2016, Citation2018) was originally utilised among undergraduate university students, and for the SAI scheme was readapted for supporting ECAs as mentees. Furthermore, the original learning model and learning contents were planned for face-to-face sessions, not online.

In the SAI scheme, we employed various active learning methodologies; for example, individual tasks and action plans, which were not adopted in previous experiences, were shared during one-to-one peer mentoring sessions. Methods like circle processes, which can be more challenging to implement online, were not utilised. Furthermore, the need to manage communicative conflicts among ECAs did not arise, indicating a smooth interpersonal dynamic among the participants.

In contrast to previous experiences, where mentoring training exclusively targeted peer mentors, the SAI scheme provided training to peer mentors and mentees. Conducting online training and one-to-one peer mentoring sessions proved to be more sustainable and effective, particularly for mature participants, including LCRs and ECAs. This proved beneficial, particularly in light of the challenging circumstances posed by COVID-19 and the essential requirement for flexibility, considering the substantial workloads of participants in these conditions.

The pedagical model adopted a social-constructivism framework (Bruner Citation1996; Vygotsky Citation1978) that guides mentoring relationships, teaching styles (trainer as learning facilitator), and mentoring tools (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023; Pfund et al. Citation2016). In accordance with the social-constructivism framework (Bruner Citation1996), we incorporated active learning methodologies in relation to the participants, aims and objectives. Drawing on the pedagogical activism of Dewey (Citation1938), the programme design centred on the subject's agency in constructing knowledge within interactive relationships between the subject and their environments, understood as the complex web of interpersonal relationships that we encounter and experience. Learning was conceptualised as the product of the mind's activity, which acts upon stimuli derived from culture and the environment, thereby selecting, recombining, engaging in meaningful communicative exchanges (Vygotsky Citation1978), and creating one's own knowledge.

In this view, both mentors and mentees were the ‘centre of the learning process’ (Isfol - Felice Citation2005, 7), actively constructing their own knowledge in interactive relationships within the contexts they engage with. Learning through mentoring experiences is co-constructed through sharing content and experiences (experiential learning). During training sessions and group supervision, the learning facilitator facilitated the development and self-awareness of the mentor's skills, bridging the formation process for mentors and mentees and emphasising the importance of planning shared goals through tangible tasks.

The trainer-coach model prioritised learning and growth by emphasising individual autonomy while simultaneously attending to academic achievement. The trainer-coach does not provide solutions but facilitates generative processes (Huston and Weaver Citation2008). This requires a positioning whereby the teacher-coach valorises each member and facilitates learning by participating in activities, sharing responsibility for the learning process, and assessing and shifting instruction if needed. This pedagogical balancing act entails attending to the emotional needs of each group member (Bussu and Contini Citation2022; Bussu and Burton Citation2022).

Consistent with this approach, we employed methods and strategies that encourage active participation in the educational journey as co-constructors of learning (Dyson Citation2010). This involves promoting transferable life skills, exemplified through self-awareness tasks and the facilitation of collaborative activities among mentees. The mentoring learning process was designed to guide mentees to explore options, develop self-confidence and life skills, build professional networks, and actively collaborate with colleagues (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Dore and Richards Citation2024).

The SAI pedagogical model is based on three principal dimensions outlined below, which drew on evidence-based recommendations.

Building reciprocal and trustworthy partnerships. A balanced mentorship relationship is built on reciprocity (Fox et al. Citation2010). To achieve this, the mentoring scheme focused on mentors’ and mentees’ learning and emotional needs. Both mentees and mentors should explore and define their own educational and professional goals related to mentoring experiences (Sorcinelli and Yun Citation2007). During training sessions, mentors and mentees acquired strategies to promote reciprocity in their relationship. This included working on generative questions to explore mutual goals and needs, developing active listening, and establishing personal strategies to foster an environment where both parties actively contribute, share, and understand each other.

Autonomy and empowerment. The objective of the mentoring relationship is to contribute to mentees’ professional growth and autonomy. In this regard, it is important to work on the mentee's transversal/life skills (WHO Citation2003) (e.g. self-awareness and self-confidence). The training content is designed to develop both self and collective efficacy (Bandura Citation2004), referring to an individual or group's competence to define and achieve specific objectives over time in the face of obstacles and setbacks.

The mentor helps mentees to explore professional goals to be achieved by developing an action plan (Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021) to undertake specific activities that need to be implemented to achieve measurable goals, in the short and long-term, following the ‘Grow model’ developed by Graham Alexander (Alexander and Renshaw Citation2005), and subsequently adapted by Whitmore (Citation2009). The action plan must include options and alternatives, personal and external resources, timetables and deadlines. Parties must explore the mentees’ obstacles and challenges. Within the training sessions, mentors and mentees acquired skills to develop action plans recurrently emphasised during the training programme. The collaborative exploration of mentee objectives and resources, and the delineation of actionable steps culminating in mentee performance have collectively contributed to the formulation of a structured plan, thereby enhancing the quality of mentoring sessions and empowering the mentee.

Group dimension. In our pedagogical model, the group dimension is crucial; peer mentor training operationalised strategies to manage this within groups and individually. The pedagogical approach embodied active learning methodologies utilising Collaborative Virtual Classrooms (Farrell et al. Citation2022), role-playing, brainstorming, and case studies for self-awareness, oriented to the active role of peer mentors in learning processes (Bussu et al. Citation2018; Bussu and Burton Citation2022). The trainer developed training content to facilitate discussions on the importance of community for mentors and mentees. Subsequently, both mentor and mentee groups opted to establish group chats and participate in mutual support activities, which is evident from the observed interactions during discussion sessions.

The SAI mentoring scheme: design and implementation

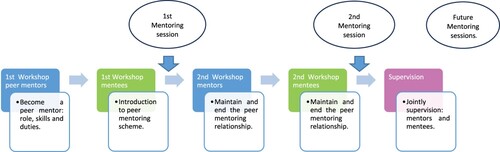

This peer mentoring scheme consisted of two sessions for training peer mentors and two sessions for mentees to facilitate self-exploration of their professional skills and career options. To support relationships with allocated peer mentors, a final session took place, which brought peer mentors and mentees together online (See ). An innovative aspect of this programme was the structured training sessions for both peer mentors and mentees. Previous peer mentoring for supporting ECAs (Merga and Mason Citation2021a; Mgaiwa and Kapinga Citation2021) did not conduct structured training sessions for peer mentors and/or mentees. However, lack of structure can also lead to mis-clarification of goals, roles and responsibilities, leading to fewer actions being operationalised. Training materials were designed in line with effective practice from international mentoring research (see, for example, Felisatti et al. Citation2019; Atenas et al. Citation2023) and were structured to match the programme aims and mentees’ needs, as expressed in initial applications and relationships with mentors as they developed across the scheme.

In total, 8 academics (five females and three males) all professional sociologists (mid-career (MCRs) and LCRs), volunteered as mentors. 10 ECAs (7 females and 3 males) participated as mentees; all were educated to a Master's level, and three had Doctoral degrees in sociology. Author 2 completed the matching process in line with evidence-based recommendations and correspondence between applicants’ statements and mentors’ professional/personal interests.

illustrates the programme design with the sequential progression of thematic content covered in the two alternating workshops for mentors and mentees, followed by the final supervision. After the first workshop session for mentors and mentees, the initial one-on-one mentoring session was conducted, and after the second workshop session, the second mentoring session took place. Following supervision, mentors and mentees continued their mentoring sessions and independently decided when to conclude the programme. also explains in detail the content sessions and key operational features. Subsequent sections delve into the model in depth to further define its structure.

Table 1. Content sessions.

Training and supervision

As per extant research, well-trained peer mentors exhibit greater confidence and frequently empower less-experienced mentees to see themselves as active members of an academic community (see, for example, Jung and Suzuki Citation2015; Venktaramana et al. Citation2023; Weinberg Citation2019). During all stages of the mentoring scheme, we conceptualised training as dynamic learning with mutual group support (Bussu et al. Citation2018; Bussu and Contini Citation2022) to reflect upon the notion of self and power relations in academia. During each session, the trainer facilitated discussions on challenging cases and strategies. Throughout sessions and supervision, mentors and mentees suggested new activities, which were discussed along with approaches for implementing them with mentees (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023; Sargent and Rienties Citation2022). During training, peer mentors explored topics that emerged from both the programme content and their experiences. Mentors shared information about academic career challenges, reflecting on their values (Atenas et al. Citation2023).

The SAI mentoring team checked in monthly using emails and phones to gauge how relationships were progressing. Training encompassed questioning processes informed by RP and goal identification for action. Hitherto, many peer mentoring programmes focused primarily on one-to-one relationships (Denny Citation2010); however, the group dimension extrapolated here was crucial to developing peer mentors’ skills, and group activities were planned with mentee groups. A similar approach informed how the trainer previously worked with professionals in mentoring in UK justice systems, with social and health services representatives, social workers, school teachers, psychologists and managers.

Best practice learning: ‘What worked in the SAI ECA mentoring programme’?

From our in-depth engagement with international research and from our own experiences as educators and mentoring programme leaders, the following points are noteworthy for developing future mentoring programmes. We are also guided by anecdotal evidence from the mentors and mentees and the Author's research and practical mentoring experience. Despite being a small-scale programme, these insights corroborate most current work as outlined below. Significantly, the structured aspect of the programme was one of the central findings as regards programme effectiveness, further indicating its importance for future ECA mentoring programmes:

Structured Approach. Designing and implementing a structured approach helped mentors and mentees to more fully understand their roles and mentoring boundaries, aiding in building relationships (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023; Pfund et al. Citation2016). It is apparent from studies that a structured approach can significantly impact early career professionals, including teachers serving as mentors (Hairon et al. Citation2020). Crucial factors that influence mentoring effectiveness are the mentor's ability to establish relationships, exhibit approachability and empathy, and share a flexible and adaptable mentoring timetable, considering the time constraints faced by mentors. The lack of time for mentor-mentee interactions can pose challenges.

Additionally, the mentee's willingness to trust the mentor's guidance plays a pivotal role (Sargent and Rienties Citation2022).

On the contrary, consistent with some of the issues explored in the context section, such as the need for human and professional support for ECAs during challenging times, consolidating a trustworthy and effective relationship between mentor and mentee can lead to a positive and formative experience for both parties. Additionally, effective mentoring between academics and professionals can also contribute, in the long term, to an improvement in the academic environment. Mentoring can also have a positive impact on the academic human environment, fostering a culture of solidarity and support among peers (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021) and increasing ECA's personal confidence (Dore and Richards Citation2024).

The structured approach and the emphasis on relationships, emotions and belonging were commented on by mentors and mentees as an important feature of the programme that influenced their professional practice.

Compatibility. Effective allocation and compatibility between mentors and mentees are important for trust and productive relationships. Mentors support the mentee based on their own skills and abilities (Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021), supporting the idea that a single mentor is not necessarily able to respond to the diversified professional and personal development needs of mentees. Mentors need not be at one's home institution, and this is sometimes useful for avoiding hierarchical dynamics (Atenas et al. Citation2023). Previous studies suggest that mentees can have more than one mentor. Due to the difficulty in finding an individual excelling as a lecturer and researcher within the mentee's specific area of interest, ECAs might find it necessary to have more than one mentor. Academic mentees are advised to establish multiple mentoring relationships throughout their careers for success. Additionally, while a mentor may excel in research advising, in some cases, their lack of a personal work-life balance could render them less suitable as a role model for maintaining healthy working patterns (Sanfey, Hollands, and Gantt Citation2013), further highlighting the complexity of matching.

Mentor self-awareness. Mentors require a high level of self-awareness to recognise and manage their behaviours, as well as to understand their roles and relationships.

One crucial aspect of developmental mentoring relationships is that the mentor must deeply understand mentoring practice (Irby Citation2013) and be able to observe themselves, the mentee, and the relationship (Atenas et al. Citation2023). We found open discussions valuable during the training, focusing on mentor self-awareness concerning their role, responsibilities, and personal commitment. Furthermore, these discussions addressed expectations regarding skills development, effective communication, generative questioning, and active listening (Bussu and Contini Citation2022; Atenas et al. Citation2023).

Supervision. Having specific spaces for mentors to discuss mentoring challenges, cases, personal needs, and difficulties is crucial for trust. The importance of mentor supervision and peer support has been highlighted previously (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Felisatti et al. Citation2019). Integrating the training scheme with an informal community of mentors can offer a valuable space for experimentation, peer support, and informal individual and group mentoring.

Flexible approach. A mentor's flexible approach is crucial for effectively guiding ECAs, given the individualised nature of their needs, the dynamic landscape of research, and diverse career pathways. A similar adaptive attitude is expected from mentees to optimise mentorship experiences, fostering a dynamic and responsive relationship that aligns with the evolving nature of research careers in the early stages (Bussu and Contini Citation2022).

Flexibility is closely tied to the exchange of reciprocal constructive feedback in mentoring relationships, signifying the mentor's depth of understanding of mentoring. This not only diminishes/minimises power imbalances in relationships but also facilitates agency. Consequently, it fosters a continuous loop of feedback and feed-forward, enabling both parties to actively contribute to the relationship (Durak Citation2024).

Impact and Evaluation. It is relevant to explore the effectiveness of training and mentoring sessions by examining the achievements and satisfaction levels of both mentors and mentees. Based on our pilot experience, future rollouts of the mentoring programme should systematically analyse mentors’ and mentees’ self-awareness of professional and personal development. While these dimensions were explored during training sessions, effective practice would be to assess these competencies at the beginning and end of the mentoring programme with structured research design and tools for in-depth evaluation of impact. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to follow up with mentees 12 months after the programme's conclusion to assess the mentoring scheme's long-term impact on their professional careers. Future studies can help to design mentoring programmes and address gaps in the literature on the implications of mentoring for LRCs, MCRs and ECAs based on robust evaluation techniques.Footnote1

Discussion

While some Irish research exists on mentoring, we have not found any comparable work from Ireland on peer mentoring for ECAs or mentoring research as applied to training sociology ECRs. However, given the emphasis on PhD student recruitment (especially international students) in Irish policies (Government of Ireland Citation2016b) and ambitious targets for the Technological University (TU) sector regarding staff PhD/NFQ Level 10 attainments, human capital investment for ECAs should now be given greater consideration by universities and government. As Ireland's third and fourth-level sectors face continuous financial challenges, mentoring constitutes a relatively low-cost option to universities that facilitates multiple opportunities for ECAs. The relational dimensions of mentoring, such as building networks, trust, and rapport, are essential for ECAs’ professional development. Furthermore, substantive international evidence illuminating the predominantly positive effects of mentoring for ECAs (Harker et al. Citation2019; Mgaiwa and Kapinga Citation2021), corroborates the significance of peer mentoring programmes for ECAs in terms of enhanced motivation, confidence, and community (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021).

The peer mentoring model outlined here has not been tested or benchmarked; however, its design and execution draw on effective practices and combine dimensions of mentoring programmes that have been tried and tested internationally (Atenas et al. Citation2023). While the model is applied here with a small number of participants, all of whom are sociologists, it is potentially adaptable to other professional contexts and universities. The highly structured aspect of the mentoring scheme is noteworthy; while some mentoring programmes comprise a ‘looser’ structure, without training, for example, and are oriented less towards shared reciprocal learning (Sorcinelli and Yun Citation2007), values, integrated activities, and goal setting, the structured approach, which emphasises individual and group learning and reflexivity, is significant for co-creating career goals, needs and aspirations (Brizuela, Chebet, and Thorson Citation2023). Comparably, the programme's orientation towards action and to short, medium and long-term goals is significant. The career development plan, which crystallises mentees’ goals, timelines, obstacles, and resources, is important in encouraging mentees to strive for and operationalise better career outcomes in the short, medium and long term. Furthermore, the group and one-to-one dimensions of the programme reiterated trust, mutuality, communication, and individual reflection, all of which are important for ECRs.

To achieve long-term impacts, mentoring should be conceptualised by all partners, including universities and governments, as a long-term opportunity and social and economic investment in ECAs’ learning and development, not as a short-term initiative. We advocate that extant research that emphasises RP, trust, and reflexivity is significant to the planning and execution of future ECA mentoring programmes. This paper corroborates these findings while also calling for greater emphasis to be placed on structured approaches, which appear to yield positive results in terms of professional goal setting. Formal mentoring programmes for ECAs can guide individuals and incorporate accompanying workshops designed to support mentees in their skill development. Additionally, these programmes provide networking opportunities that are valuable for ECAs in accessing grants, collaborative opportunities, and job networks (Meschitt and Lawton Smith Citation2017; Schriever and Grainger Citation2019).

The future implementation of mentoring schemes across disciplines and in universities could also be complemented by new research agendas which benchmark the effectiveness of mentoring in different contexts, given the (multifarious) impacts of institutional cultures on the success of mentoring initiatives (Kochan Citation2013). Furthermore, the instigation and adoption of mentoring programmes by other professional organisations for ECAs nationally could enhance employment and career options for ECAs, as evident in previous studies (Garcia and Henderson Citation2015). This paper is limited in terms of mentor/mentee numbers, but our professional insights and those of project participants qualify some of the key characteristics of effective mentoring as stated in previous research (e.g. compatibility, self-awareness). It should also be noted that this is only the first phase of the peer mentoring scheme; the subsequent planned phase employs biographic, narrative interviewing to elicit more detailed responses on the labyrinthine effects of mentoring on participants’ career and personal trajectories in the short, medium and long-term. More longitudinal qualitative research on the effects of peer mentoring on mentees and mentors in Ireland and internationally would also be valuable in further establishing the evidence base for ECA mentoring (Schriever and Grainger Citation2019).

The literature review also generated fruitful research avenues for mentoring. Specifically, HE mentorship programmes internationally would benefit from concerted research efforts to understand how mentorship training impacts the quality of peer mentoring. For example, LCRs might feel well equipped to mentor people from different cultures and disciplinary fields (Fleming et al. Citation2013), but training is critical in learning to work and communicate effectively with others in delineating personal goals and understanding the multidimensional personal/professional factors that might detract mentees from achieving them. Furthermore, the nuanced nature of peer mentoring necessitates greater research with regard to variables like social class, gender, race and organisational culture, which generate extensive research effort internationally but substantially less so in Ireland (Bogat and Liang Citation2005). Developing these research agendas nationally is important for appreciating how cultural factors contribute to the success/failure of mentoring initiatives in organisations and for establishing larger-scale mentoring programmes for ECAs by the government.

Finally, instilling mentoring cultures into Irish universities so that all ECAs can benefit can be accomplished by political will, financial commitments by governments and universities to ECAs and understanding mentoring as a tool for positive change. Given the predominance of neo-liberal thinking in Irish HE (Loxley and Seery Citation2012), which has militated against larger-scale investments in the social sciences, the future implementation of larger-scale mentoring initiatives in social scientific disciplines necessitates a governmental re-think of the creative power of these disciplines and their importance for public policy, society and the economy. While extant research highlights that mentoring can lead to very positive outcomes, its success is reliant on external and internal factors, including funding, institutional commitment and relationships (Atenas et al. Citation2023; Diggs-Andrews, Mayer, and Riggs Citation2021).

In order for mentoring schemes to offer higher-quality mentoring support, institutions should actively endorse and implement peer mentoring initiatives. There are financial and human capital implications; mentors and mentees must be equipped with adequate tools to effectively build and nurture positive peer mentoring relationships, including professional trainers. Additionally, institutions should offer professional mentoring training opportunities for mentees and mentors to reflect on their roles and expectations within these processes (Atenas et al. Citation2023).

Conclusions

The impacts of peer mentoring schemes on ECAs are multidimensional and diverse; mentoring offers much in terms of forging relationships, building self-confidence and identifying new and enhanced career prospects (Dore and Richards Citation2024). In Europe and internationally, research on mentoring ECAs is well developed; however, in Ireland, research is sparse, which reflects a lack of large-scale human capital and financial investment by government and universities in peer mentoring programmes for ECAs. While this scheme was small-scale and our observations are limited to a pilot phase only, our analysis suggests that mentoring programmes for ECAs, when built upon mutuality, support, and reciprocal engagement, can yield positive results for mentors and mentees. Moreover, the paper corroborates the importance of structured peer mentoring schemes, a potentially important finding for the effective design and implementation of ECA peer mentoring programmes (Atenas et al. Citation2023).

Although mentoring schemes differ in terms of their design and implementation, ultimately, their success in terms of participant engagement and learning is contextual. The mentoring model discussed here, which operationalised mentor-mentee compatibility and was oriented to self-awareness, flexibility, reflexivity, and training, is potentially applicable to other professional contexts in Ireland and elsewhere. However, choosing and implementing an effective mentoring scheme should be informed by research into interlinking factors (cultural, economic and organisational) that affect the successful design, implementation and evaluation of these programmes. The low-cost base of ECA peer mentoring schemes renders them potentially attractive to universities, especially during times of increased living costs. However, these schemes would likely prove most effective when embedded in a broader, interconnected suite of support programmes for ECAs that are research-informed, evaluated for continuous improvement and attuned to the medium and long-term career goals of ECAs/doctoral candidates, which may also vary by discipline (to some extent) (Schriever and Grainger Citation2019). Further research needs to be undertaken to explore solutions about how HE administrators and faculty can create an enabling atmosphere for mentoring amid the often-conflicting demands for faculty to attain tenure, secure grants, and publish. Additionally, research could contribute to providing clarity on the role of LCRs’ values and life experiences in fostering successful mentoring relationships with ECAs.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Dr Elaine Keane, Co-Editor IES, and anonymous referees for their invaluable suggestions, which significantly contributed to the improvement of the manuscript. Sincere gratitude to all mentors and mentees who participated in our Peer Mentoring Scheme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Bussu

Dr Anna Bussu is a senior lecturer in criminal justice at Edge Hill University (UK), a senior fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK) and a chartered psychologist (BPS). Since 2014, she has researched and facilitated psycho-pedagogical practices such as mentoring and coaching, aiming to promote self-development and empowerment. She is currently leading a mentoring scheme for the Regional University Network Plus (RUN-EU +) project.

Lisa Moran

Dr Lisa Moran is the dean of graduate studies, head of the Graduate School and a senior lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Ireland. She is a senior fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK).

Notes

1 We want to highlight that during the first edition of the mentoring scheme, we were unable to obtain timely approval from the ethics committee for the implementation of the qualitative research aimed at rigorously collecting the perspectives and satisfaction of mentors and mentees who participated in the study.

References

- Alexander, G., and B. Renshaw. 2005. Super Coaching. London: Random House.

- Atenas, J., C. Neranzti, and A. Bussu. 2023. “A conceptual approach to transform and enhance academic mentorship through Open Educational Practices.” Open Praxis 15 (4): 271–287. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.15.4.595

- Baker, V. L., Pifer, M. J., and K. A. Griffin. 2014. “Mentor-protégé fit.” International Journal for Researcher Development 5 (2): 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRD-04-2014-0003

- Bandura, A. 2004. “Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means.” Health Education & Behavior 31 (2): 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

- Boeren, E., I. Lokhtina-Antoniou, Y. Sakurai, C. Herman, and L. McAlpine. 2015. “Mentoring: A Review of Early Career Academic Studies.” Frontline Learning Research 3 (3): 68–80. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v3i3.186.

- Bogat, G. A., and B. Liang. 2005. “Gender in Mentoring Relationships”. In Handbook of Youth Mentoring, edited by D. L. DuBois and M. J. Karcher, 205–217. CA: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Brizuela, V., J. J. Chebet, and A. Thorson. 2023. “Supporting Early-Career Women Researchers: Lessons from a Global Mentorship Programme.” Global Health Action 16 (1): 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2162228.

- Browning, L., K. Thompson, and D. Dawson. 2014. “Developing Future Research Leaders: Designing Early Career Academic Programs to Enhance Track Record.” International Journal for Researcher Development 5 (2): 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRD-08-2014-0019.

- Bruner, J. 1996. "The Culture of Education". Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bussu, A., and S. Burton. 2022. “Higher education peer mentoring programme to promote student community using Mobile Device Applications.” Groupwork 30 (2): 53–71.https://doi.org/10.1921/gpwk.v30i2.1636

- Bussu, A., C. N. Veloria, and C. Boyes-Watson. 2018. “Study Circle: Promoting a restorative student community.” Pedagogy and the Human Sciences 6 (1): 1–20. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/phs/vol6/iss1/6

- Bussu, A. and R. Contini. 2022."Peer mentoring Universitario. Generare legami sociali ecompetenze trasversali". Milano: Franco Angeli

- Bussu, A., Quinde Reyes, M., Macias Ochoa, J. and E. Mulas. 2016."Modelo de intervención StudyCircle: promover la paz y el bienestar estudiantil con las prácticas restaurativas. In Roja Garcia, A., Villalobos Monroy, G., Brunett Zarza, K. andMartine Orozco J.P. (Eds). Convivencia y bienestar con sentido humanista para una culturade paz. Universidad Autonoma del Estado del Mexico. ISBN 978-607-42-2775-8

- Courtois, A., and A. Veiga. 2020. “Brexit and Higher Education in Europe: The Role of Ideas in Shaping Internationalisation Strategies in Times of Uncertainty.” Higher Education 79 (5): 811–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00439-8

- Crisp, G., and I. Cruz. 2009. “Mentoring College Students: A Critical Review of the Literature between 1990 and 2007.” Research in Higher Education 50 (6): 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2.

- Deng, C., D. B. Gulseren, and N. Turner. 2022. “How to Match Mentors and Protégés for Successful Mentorship Programs: A Review of the Evidence and Recommendations for Practitioners.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 43 (3): 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2021-0032.

- Denny, H. C. 2010. Facing the Center: Toward an Identity Politics of one-to-one Mentoring. : Logan, Utah: Utah State University.

- Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan

- Diggs-Andrews, K. A., D. C. Mayer, and B. Riggs. 2021. “Introduction to Effective Mentorship for Early-Career Research Scientists.” BMC Proceedings 15 (7): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-0v21-00212-9.

- Dore, E., and Richards, A. 2024. Empowering Early Career Academics to Overcome low Confidence.” International Journal for Academic Development 29 (1): 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2022.2082435.

- Durak, Y. H. 2024. “Feedforward-or Feedback-Based Group Regulation Guidance in Collaborative Groups.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 40 (2): 410–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12887

- Dyson, M. 2010. “What Might a Person-Centered Model of Teaching Education Look Like in the 21st Century?” The Transformism Model of Teacher Education.” Journal of Transformative Education 8 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611406949.

- Ehrich, L., B. Hansford, and L. Tennent. 2004. “Formal Mentoring Programs in Education and Other Professions: A Review of the Literature.” Educational Administration Quarterly 40 (4): 518–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X04267118.

- Farrell, R., P. Cowan, M. Brown, S. Roulston, S. Taggart, E. Donlon, and M. Baldwin. 2022. “Virtual Reality in Initial Teacher Education (VRITE): A Reverse Mentoring Model of Professional Learning for Learning Leaders.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (1): 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.2021102.

- Felisatti, E., O. Scialdone, M. Cannarozzo, and S. Pennisi. 2019. “Mentoring at University: The Project “Mentors for Teaching” at Palermo University”. Italian Journal of Educational Research 23:178–893. https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/sird/article/view/3690

- Ferguson, H., and K. Wheat. 2015. “Early Career Academic Mentoring Using Twitter: The Case of #ECAchat.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 37 (1): 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.991533.

- Fleming, M., S. House, V. S. Hanson, L. Yu, J. Garbutt, R. McGee, et al. 2013. “The Mentoring Competency Assessment: Validation of a new Instrument to Evaluate Skills of Research Mentors.” Academic Medicine 88 (7): 1002–1008. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318295e298

- Fox, A., L. Stevenson, P. Connelly, A. Duff, and A. Dunlop. 2010. “Peer-mentoring Undergraduate Accounting Students: The Influence on Approaches to Learning and Academic Performance.” Active Learning in Higher Education 11 (2): 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787410365650.

- Garcia, I., and S. Henderson. 2015. “Mentoring Experiences of Latina Graduate Students.” Multicultural Learning and Teaching 10 (1): 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1515/mlt-2014-0003.

- Gewin, V. 2020. “The Career Cost of COVID-19 to Female Researchers, and how Science Should Respond.” Nature 583 (7818): 867–869. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02183-x.

- Government of Ireland. 2016a. "STEM Education, Policy Statement: 2017-2026". DES.Retrieved from https://assets.gov.ie/43627/06a5face02ae4ecd921334833a4687ac.pdf

- Government of Ireland. 2016b. "Irish Educated, Globally Connected Dublin". DES. Retrived from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/553ec-irish-educated-globally-connected-an-international-education-strategy-for-ireland-2016-2020/.

- Hairon, S., S. H. Loh, S. P. Lim, S. N. Govindani, J. K. T. Tan, and E. C. J. Tay. 2020. “Structured Mentoring: Principles for Effective Mentoring.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 19 (2): 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-019-09251-8.

- Harker, K., E. O'Toole, S. Keshmiripour, M. McIntosh, and C. Sassen. 2019. “Mixed-Methods Assessment of a Mentoring Program.” Journal of Library Administration 59 (8): 873–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2019.1661745.

- Huston, T., and C. L. Weaver. 2008. “Peer Coaching: Professional Development for Experienced Faculty.” Innovative Higher Education 33 (5): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-007-9061-9.

- Irby, B. J. 2013. “Editor's Overview: Mentoring as a Social Function.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 21 (2): 121–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2013.820030.

- Isfol - Felice, A. 2005. L’accompagnamento per Contrastare la Dispersione Universitaria: Mentoring e Tutoring a Sostegno Degli Studenti. Roma: Isfol. https://isfoloa.isfol.it/xmlui/handle/123456789/1524.

- Johnson, R. W., and M. M. Weivoda. 2021. “Current Challenges for Early Career Academics in Academic Research Careers: COVID-19 and Beyond.” JBMR Plus 5 (10): e10540. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10540

- Jung, I., and Y. Suzuki. 2015. “Scaffolding Strategies for Wiki-Based Collaboration: Action Research in a Multicultural Japanese Language Programme.” British Journal of Educational Technology 46 (4): 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12175.

- Kehm, B. 2007. “The Changing Role of Graduate and Doctoral Education as a Challenge to the Academic Profession: Europe and North America Compared.” In Key Challenges to the Academic Profession, edited by M. Kogan and U. Teichler, 111–124. UNESCO Forum on Higher Education Research and Knowledge. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000152928.

- Koch, K. 2021. “Cross Border Resilience in Higher Education.” In Borderlands Resilience, edited by D. J. Anderson and E-K Prokkola, 37–53. London: Routledge.

- Kochan, F. 2013. “Analysing the Relationships between Mentoring and Culture.” Mentoring & Tutoring 21 (4): 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2013.855862.

- Loxley, A., and A. Seery. 2012. “The Role of the Professional Doctorate in Ireland from the Student Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.489148.

- Lynch, K. 2010. “Carelessness: A Hidden Doxa of Higher Education.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 9 (1): 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022209350104.

- Marino, F. E. 2021. “Mentoring Gone Wrong: What is Happening to Mentorship in Academia?” Policy Futures in Education 19 (7): 747–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320972199.

- Mellors-Bourne, R., Humfrey, C., Kemp, N., and Woodfield, S. 2013. The wider benefits of international higher education in the UK. BIS Research paper, 128. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/240407/bis-13-1172-the-wider-benefits-of-international-higher-education-in-the-uk.pdf

- Merga, M. K., and S. Mason. 2021a. “Mentor and Peer Support for Early Career Academics Sharing Research with Academia and Beyond.” Heliyon 7 (2): e06172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06172.

- Merga, M. K., and S. Mason. 2021b. “Doctoral Education and Early Career Academic Preparedness for Diverse Research Output Production.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (5): 672–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1807477.

- Meschitt, V., and H. Lawton Smith. 2017. “Does Mentoring Make a Difference for Women Academics: Evidence from the Literature and a Guide for Future Directions.” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 7 (1): 166–199. https://doi.org/10.22381/JRGS7120176.

- Mgaiwa, S., and O. Kapinga. 2021. “Mentorship of Early Career Academics in Tanzania: Issues and Implications for the Next Generation of Academics.” Higher Education Pedagogies 6 (1): 114–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2021.1904433.

- Montgomery, B. L., J. E. Dodson, and M. J. Sonya. 2014. “Guiding the Way: Mentoring Graduate Students and Junior Faculty for Sustainable Academic Careers”. Sage Open 4 (4): 215824401455804. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014558043.

- Mullen, C., and S. Forbes. 2000. “Untenured Faculty: Issues of Transition, Adjustment and Mentorship.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 8 (1): 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685508

- Oberhauser A. M., and M. Caretta. 2019. “Mentoring Early Career Women Geographers in the Neoliberal Academy: Dialogue, Reflexivity, and Ethics of Care” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 101 (1): 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2018.1556566.

- O'Connor, P. 2023. “The Precarious Employment of Staff in Irish Higher Educational Institutions and its Policy Implications” Public Policy.ie. Retrieved from The precarious employment of staff in Irish Higher Educational institutions and its policy implications – Public Policy, last accessed 08 October 2023.

- Orlando, J., and M. Gard. 2014. “Playing and (not?) Understanding the Game: ECAs and University Support.” International Journal for Researcher Development 5 (1): 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRD-10-2013-0016.

- Pfund, C., A. Byars-Winston, J. Branchaw, S. Hurtado, and K. Eagan. 2016. “Defining Attributes and Metrics of Effective Research Mentoring Relationships.” AIDS and Behavior 20 (S2): 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1384-z.

- Sanfey, H., C. Hollands, and N. L. Gantt. 2013. “Strategies for Building an Effective Mentoring Relationship.” The American Journal of Surgery 206 (5): 714–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.001.

- Sargent, J., and B. Rienties. 2022. “Unpacking Effective Mentorship Practices for Early Career Academics: A Mixed-Methods Study.” International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 11 (2): 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-05-2021-0060.

- Sauermann, H., and M. Roach. 2012. “Science PhD Career Preferences: Levels, Changes and Advisor Encouragement.” PLoS One 7 (5): e36307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036307.

- Schriever, V., and P. Grainger. 2019. “Mentoring an Early Career Researcher: Insider Perspectives from the Mentee and Mentor.” Reflective Practice 20 (6): 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1674272.

- Shankar, K., D. Phelan, V. Suri, R. Watermeyer, C. Knight, and T. Crick. 2021. “The COVID-19 Crisis is not the Core Problem: Experiences, Challenges and Concerns of Irish Academia During the Pandemic.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1932550.

- Smith, E. R. 2020. “Techniques for Mentors to Support Early Career Teachers’ Reflective Practice.” Teaching Geography 45 (2): 53–55.

- Sorcinelli, M. D., and J. Yun. 2007. “From Mentor to Mentoring Networks: Mentoring in the New Academy.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 39 (6): 58–61. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.39.6.58-C4.

- Straus, S. E., M. O. Johnson, C. Marquez, and M. D. Feldman. 2013. “Characteristics of Successful and Failed Mentoring Relationships: A Qualitative Study Across two Academic Health Centres.” Academic Medicine 88 (1): 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0.

- Termini, C. M., and D. Traver. 2020. “Impact of COVID-19 on Early Career Scientists: An Optimistic Guide for the Future.” BMC Biology 18 (95): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00821-4.

- Udegbe, I. B. 2016. “Preparedness to Teach: Experiences of the University of Ibadan Early Career Academics.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (10): 1786–1802. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1221656.

- Veloria, C. N., A. Bussu, and M. Murry. 2020. “The transformative possibilities of restorative approaches to education.” In Intercultural education: Critical perspectives, pedagogical challenges, and promising practices, edited by C. Pica-Smith, C. N. Veloria, and R. Contini, 298–320. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Venktaramana, V., Y. T. Ong, J. W. Yeo, A. Pisupati, and L. K. R. Krishna. 2023. “Understanding Mentoring Relationships between Mentees, Peer and Senior Mentors”. BMC Medical Education 23 (76): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04021-w

- Vitae. 2011. Principal Investigators and Research Leaders Survey. London, UK. Retrieved from https://www.vitae.ac.uk/vitae-publications/reports/annual-report-vitae-2011.pdf/@@download/file/Annual-Report-Vitae-2011.pdf.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Weinberg, F. J. 2019. “How and When is Role Modelling Effective? The Influence of Mentee Professional Identity on Mentoring Dynamics and Personal Learning Outcomes.” Group & Organization Management 44 (2): 425–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601119838689.

- Whitmore, J. 2009. Coaching for Performance: Growing Human Potential and Purpose - the Principles and Practice of Coaching and Leadership. 4th ed. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2003. “Skills for Health: Skills-Based Health Education Including Life Skills: An Important Component of a Child-Friendly/Health-Promoting School.” In World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42818.