ABSTRACT

In 2018, the Irish Department of Education and Skills (DES) officially recommended a distributed leadership model as a new approach to leadership and management in post-primary schools. Policy implementation guidance was circulated to school management via DES circular CL003/2018. This study investigates the perspective of voluntary secondary school principals implementing CL003/2018 within the voluntary secondary school sector, where the role of the school principal is pivotal in its implementation.

A pragmatic approach to the research methodology led to the adoption of a case study methodology within a mixed-method sequential quantitative > qualitative research design. The quantitative research instrument was an online survey distributed to a census population of voluntary secondary school principals in Ireland. Using Zoom, semi-structured interviews with ten voluntary secondary school principals informed the qualitative research.

The findings are examined and interpreted within the literature on distributed leadership, with the concepts of power, accountability, and sustainability emerging from the research.

The research identifies recommendations on professional learning for principals to develop sustainable leadership capacity within the voluntary secondary school sector, and the essential time to hold strategic leadership team meetings.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the implementation of the Department of Education and Skills (DES) CL003/2018, entitled ‘Leadership and Management in Post-Primary Schools which outlines the allocation of assistant principal posts of responsibility, creating a middle leadership team in schools referred to as assistant principal I (API), and assistant principal II (APII) posts. The deputy principal and assistant principals support the principal within the leadership framework. DES CL003/2018 introduced a revised criterion for appointment to the assistant principal position using a competency-based model, phasing out seniority as a stand-alone criterion. It also mandated a criterion for the assignment and reassignment of roles and responsibilities to assistant principals to allow school management greater flexibility to respond to their school's individual needs and priorities, along with an appeals procedure for appointments confined to an alleged breach of procedures in the appointment process.

This paper explores how DES CL003/2018 completes a shift from the predominant hierarchical model of school leadership to a more collaborative practice through the contextualisation of this national policy, which Ball (Citation1993) describes as the challenge ‘to relate together analytically the ad hocery of the macro with the ad hocery of the micro without losing sight of the systematic bases and effects of ad hoc social actions’ (p.10).

The context for this research paper is the voluntary secondary school sector which involves 366 out of a total of 730 post-primary schools in Ireland. Voluntary secondary schools operate under patrons’ or trustees’ licenses governed by religious congregations or diocesan bodies and can promote and protect their characteristic spirit, also known as ethos, under Articles 42 and 44 of the Irish Constitution (1937). The governance and funding of schools in this sector differ from other post-primary sectors, with some schools in the sector operating as fee-paying schools and others as non-fee-paying schools, with the non-fee-paying schools receiving grants and subsidies from the state. Despite the significance of the new policy for the management of schools in Ireland, there is no research on the principal's perspective on the impact of DES CL003/2018 within the post-primary voluntary school sector. This research study aims to amplify the voices of school principals as they navigate the implementation of policy requirements within their respective voluntary secondary schools. Unlike the next largest sector, the Education and Training Boards (ETB) with 225 post-primary schools, the voluntary sector does not have the benefit of regional education authorities which provide support for ETB schools including finance, human resources, and management of building projects. Therefore, this study reflects the viewpoints of school principals, individuals entrusted with extensive and diverse duties, highlighting the pivotal role of leadership models in their professional realm.

While Redmond (Citation2016) claims that capturing and consolidating the perspective of school principals has become a pivotal approach in revealing the narrative of modern school leadership, Murphy (Citation2023) argues that there is a dearth of research on principals’ perspectives regarding their readiness to lead schools in the current policy context. For that reason, this research specifically examines the perspective of a group of Irish voluntary secondary school principals in a case study approach. It studies the principals’ descriptions of how they develop distributed leadership in their schools, capturing their understanding of the implementation process and the success and challenges that go along with it. Furthermore, this research attempts to address the gap between distributed leadership theory and its implementation in schools, by taking cognisance of the culture and context of putting the policy into practice (Bonneville Citation2017).

From an Irish perspective, Kavanagh (Citation2020) researched DES CL003/2018 within the Education and Training Board (ETB) sector. Additionally, Murphy and Brennan (Citation2022) assessed the experience of Irish primary school principals enacting distributed leadership, while Moynihan and O’Donovan (Citation2021) investigated the vital role played by the school principal in developing and implementing collaborative practice in voluntary secondary schools before DES CL003/2018. Therefore, this paper will complement previous research conducted within the area of distributed leadership in Ireland, as there is a shortage of empirical evidence concerning post-primary school principals’ perspectives and experiences regarding implementing the new model of distributed leadership outlined in DES CL003/2018.

This research inquiry probes the following research question:

What is the experience of post-primary school principals implementing distributed leadership in the voluntary secondary school as mandated in the Department of Education and Skills (DES) CL003/2018?

Does implementing DES CL 003/2018 change the post-primary principal's role within the school's leadership framework?

Does the micropolitics of a school impact the implementation of DES CL003/2018?

Is there a distribution of accountability and responsibility within the distributed leadership framework outlined in DES CL003/2018?

The research question and its sub-questions inform the focus of the literature review, which examines Irish and international literature on distributed leadership in schools, considering the role of the principal, politics, and accountability in establishing a distributed leadership model.

2. Literature review

2.1. Introduction

This literature review focuses on the concepts that define the study’s fundamental questions, placing the conceptual framework in the context of school leadership. Within the literature on enacting distributed leadership in schools, the concepts of the micropolitics of schools, accountability and the role of the school principal emerge.

Distributed leadership is considered a democratic form of leadership and historically, researchers have considered the role of education in disseminating democratic values (Sant Citation2019). The Democracy in Education Movement in the United States of America (USA) acknowledge that Dewey's (Citation1916) calls for democratic education were made in a different political and economic environment. However, the basic tenet of educating for democracy still prevails, albeit with many ontological and epistemological viewpoints and the distributed leadership model aligns with the discourse on the role of democracy in education and school leadership. Notably, research on education systems ‘as carriers of modern orientations and democratic values worldwide predicts that educated individuals will exhibit more democratic values than less educated ones, regardless of the country's level of democracy’ (Kołczyńska Citation2020, 3). Meanwhile Nishiyama (Citation2021) argues for consideration of schools from a broader perspective and recognises a growing emphasis in the 2000s on schools as places where democratic deliberation evolves. Furthermore, Tenuto (Citation2014) observes the movement of political systems from the 1990s and increasingly in the twenty-first century to develop national educational goals which promote democracy in schools and, therefore, in society. Democratic values in education are also reflected in the OECD report, Improving School Leadership (Citation2008b), which recognised that the expansion and intensification of the role of the school leader meant that education systems needed to adopt a broader notion of school leadership and acknowledged that countries were experimenting with different ways to allocate better distribution of tasks across leadership teams. It transpires that as legislative and curricular changes impacted schools, a strong sense of the necessity for distributed leadership emerged, with leading a school becoming increasingly complex and demanding for one person (Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond Citation2001, Citation2006).

Interestingly much of the literature on distributed leadership in schools expounds on the point that the school principal plays an essential role in successfully implementing distributed leadership. Therefore, if a successful distributed leadership model requires the principal to embed the concept of distributed leadership systemically throughout the school, it also involves utilising various leadership skills, communicating expectations, and creating a dialogue in the school community, reinforcing the notion that principals must suppress authority to permit others to lead (Murphy and Seashore Citation2018). Changing the leadership framework in schools to reflect democratic values and facilitate school improvement requires implementing a new way of thinking and doing. As the day-to-day operational leader, the voluntary secondary school principal leads this change within cultural and contextual factors, putting theory into practice.

However, despite its promising theoretical appeal, distributed leadership faces numerous challenges in practice. Exploring the problems faced by headteachers in leading a distributed leadership approach, Tahir et al. (Citation2016) reported that teachers often perceive duties beyond the classroom as extra workload and can be resistant to undertaking leadership roles. Selection processes the provision of training and support for leaders, requires time and careful consideration. Headteachers also found it challenging to involve multiple teaches in different levels of management. Irvine (Citation2020) further identifies school size as a challenge for implementing distributed leadership, arguing that smaller schools may be more cohesive and collaborative but lack sufficient leadership capacity to facilitate distributed leadership successfully. Efforts to embed distributed leadership often fall short according to Camburn and Han (Citation2009) due to a lack of clearly defined expectations for leadership responsibilities, a lack of training for teachers and a sense of isolation in schools where the political climate and culture limit social interactions.

2.1. Distributed leadership as practice

While the concept of distributed leadership is ambiguous and refers to a wide range of practices, Tian, Risku, and Collin (Citation2016) describe two paradigms in their meta-analysis of distributed leadership theory as ‘a descriptive-analytical paradigm, providing an understanding of the concept of distributed leadership: secondly, a prescriptive -normative paradigm with a focus on the practice of distributed leadership’ (p.149). Furthermore, in their distributed leadership study, Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond (Citation2001) argue that practice stretches over leaders, followers, and situations defined by the relational or situational context of leaders and followers. The interactional and relational aspects of the model are apparent. Similarly, Spillane (Citation2006) suggests leadership is stretched across the school community by relational connections, as illustrated in below.

Figure 1. Leadership in Practice (Spillane Citation2006).

Internationally, Liu (Citation2020) examines how contextual variables affect distributed leadership in schools across thirty-two countries using international evidence from the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) data. The findings highlight seven different types of distributed leadership operating across thirty-two countries. The evidence demonstrates distributed leadership in schools with various levels of decision-making occurring with management teams and teachers. Anglo countries appear to have a high level of distributed leadership, with Nordic Europe having the highest implementation. The findings support the practice-centred approach, with distributed leadership depending on situations and contextual variations such as country policies and school culture (Liu Citation2020).

Looking at Nordic Europe, Lahtero, Lång, and Alava (Citation2017) studied distributed leadership in practice in Finnish schools, and, unlike Ireland, Finnish schools have no formal hierarchical structure, as the ‘teachers are usually appointed to the management team on a temporary basis’ (p.218). Interestingly, in that study, Lahtero, Lång, and Alava (Citation2017) note that more than half of respondent teachers perceive distributed leadership as delegating assigned tasks rather than interaction among leaders. However, from a more advanced point of view, a significantly smaller number of respondents ‘described distributed leadership as an interaction between leaders, followers, and situations’ (p.225). Furthermore, in their recent study, Lahtero, Ahtiainen, and Lång (Citation2019) sought principals’ views on enacting distributed leadership in Finland. Of relevance, they explored the principal's views of distributed leadership in Finnish schools to examine if distributed leadership is a delegation by principals or the principal and the leadership team's interaction. Their study claims the usefulness of focusing on the interactive engagement between principals and teachers.

Moving to southern Europe, Gómez-Hurtado et al. (Citation2020) conducted a research study on the practice of implementing distributed leadership in two Spanish secondary schools, adding that, in practice, ‘the actions of principals in the configuration and distribution of the leadership in these centres are key’ (p.9). The dominant finding is the importance of contextual factors and the use ‘of power as a regulating mechanism of social relations. In tandem, Printy and Liu (Citation2020) suggest that teachers will undertake leadership roles if the school culture is conducive to distributed leadership and the country context is part of the contextual situation. Within the global context, distributed leadership in schools is on a journey. The significance of DES CL003/2018 is that it formalises Ireland's journey and provides a roadmap for a distributed leadership framework in schools. The next section considers distributed leadership as practice in Ireland.

2.2. Distributed leadership in practice in Ireland

The current thinking in Irish education policy regarding leadership in schools certainly demonstrates a definite move towards a distributed leadership approach. This is clearly articulated in the Looking at Our Schools (LAOS) quality framework (Department of Education Inspectorate Citation2022). The LAOS quality framework replaces the previous 2016 edition, providing a coherent set of standards for two dimensions of the work of schools, teaching and learning and leadership and management, within a framework for evaluating standards and accountability. The document takes a macro look at schools and sets the leadership agenda within the socio-political environment.

While working with primary school principals, Murphy and Brennan (Citation2022) note ‘little research on DL in the Republic of Ireland in practice’ and ‘that practising leadership in a DL model is, for many, a radical departure from the hierarchical and managerialist structures of the relatively recent past’ (p.14). Supporting that argument in post-primary schools, Hickey, Flaherty, and Mannix McNamara (Citation2022) concur that ‘despite multiple literature reviews that sought to yield greater understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of distributed leadership, there is little focus on empirical research on distributed leadership in post-primary schools’, yet it ‘has now become prevalent and pervasive in both policy and practice spheres’ (p.1). Beyond exploring the roles and tasks of middle leaders there is a clear need for research to explore related practice, as was highlighted by Forde et al. (Citation2019), in their reflection on both the Irish and Scottish leadership policy context, Therefore, the how of distributed leadership rather than the why should now take centre stage.

How distributed leadership is implemented takes cognisance of culture and context within the school, and school principals are central to framing the construct to improve teaching and learning and establish a collaborative culture extending to leadership teams (Moynihan and O’Donovan Citation2021). Furthermore, Murphy and Brennan (Citation2022) agree that ‘culture plays a key role in the enactment of DL, as well as transformational and transformative learning to support this reculturing both within and beyond the school’ (p.14).

The principal has a key role in the how of distributed leadership policy and must convince teachers to engage in the process, motivate support and encourage leadership among the teaching cohort. School principals provide a mechanism through which policies and practices can move from rhetoric to implementation (Spillane and Anderson Citation2019). The implementation process requires the school principal to encourage collaboration, engagement, and empowerment within the micro-political activity of the school. Butler (Citation2024) suggests principals use coaching skills to build leadership capacity and collaboratively distribute responsibilities. However, he also acknowledges that principals may require upskilling in coaching skills.

2.3. Micro-politics

The functioning of a school is entwined with the intricate dynamics of micro-politics. Gronn (Citation2009) suggests the enactment process of distributed leadership is potentially related to abuses of power, which critics claim is often overlooked because the process disguises that a cohort of individuals within the organisation can hold significant power. Indeed, in the vast array of literature on distributed leadership, the element of power does not take centre stage (Spillane Citation2007; Harris Citation2008; Tian, Risku, and Collin Citation2016). However, Lumby (Citation2013) notes ethical questions relating to power and agency and argues that distributed leadership is a political phenomenon ‘replete with the uses and abuses of power’ (p.592). Resonating with the Irish school context, Mifsud (Citation2017, 154) notes that schools are ‘traditionally bureaucratic organisations with hierarchical demarcations of position and pay scale’, which the author recognises as a potential barrier to a smooth application of a distributed leadership approach. In agreement, Piot and Kelchtermans (Citation2015), in their study of collaboration between principals within four Flemish school federations, posit ‘a central idea in micropolitical theory is that organisation members’ actions (and sense-making) are largely driven by their interests’ (Piot and Kelchtermans Citation2015, 1). Of concern, such divergent thinking within can lead to inconsistent and fragmented practice, hinder collaboration and lead to potential conflicts within the school community.

Another factor to consider is that teachers’ non-compliance and micro-politics may purposefully or unintentionally alter a policy's intended implementation (Giudici Citation2020). How schools deal with new policy texts ‘depends on contextual and institutional constraints specific to the enactment phase, such as school location’ (Giudici Citation2020, 5). The enactment of the DES CL003/2018 requires a process of interpretation and translation: it thus implies ‘repeated negotiations about policies’ meanings and ways they are put into practice’ (Giudici Citation2020, 5). There is a political dimension to assigning leadership roles, whereby some teachers may feel empowered, and some teachers who may be unsuccessful in obtaining leadership roles may feel disempowered.

Despite the challenges, even still, the principal's influence as the formal leader and the school's culture or climate is paramount to successfully enacting distributed leadership (Diamond and Spillane Citation2016). Principals retain considerable formal power, and distributed leadership will not be manifest ‘if principals do not support it’ (Printy and Liu Citation2020, 7). Focusing on the principal's views and opinions regarding its implementation process needs to be more evident, and the role of power and politics must be considered (Lumby Citation2013). As principals distribute leadership throughout the school, they are also distributing responsibility, so the question of accountability must be considered.

2.4. Accountability

The concepts of leadership, responsibility and accountability often go hand in hand, yet this is not always clear cut in practice. In their study, Lahtero, Ahtiainen, and Lång (Citation2019) state that some parts of school leadership must be defined clearly, such as who takes ‘responsibility’ (p.345). DES CL/003/2018 describes leadership and management posts of responsibility, acknowledging that teachers take responsibility for any aspect of school leadership; however, the accountability to the stakeholders resides with the principal. Interestingly, King and Stevenson (Citation2017) note that in an environment ‘where high stakes accountability often drives control and conformity’ (p.667), it is challenging for school leaders to create conditions where teachers can exercise leadership.

Rashid (Citation2015) suggests mutual accountability is associated with teams, whereby the team members share the liability and are accountable. However, in contrast, within educational environments, Abadzi (Citation2017) states that if work groups are large and lack the means to reward individuals, people may feel a limited personal obligation to accountability. However, many teams’ working relationships in education are informal and function based on goodwill and volunteerism. Thus, while teachers may take responsibility for a whole school project or activity, there is no onus on them for accountability.

Within the formal leadership structure, DES CL003/2018 provides for an annual review process with assistant principals; the principal remains accountable to the board of management; therefore, principals may be less willing to relinquish power in a climate of accountability, as it might leave them vulnerable due to a lack of direct control concerning financial, legal, and human resource issues and the school's educational operation (OECD Citation2008). This complexity brings the notion of educational responsibility and accountability to the fore, which Connolly, James, and Fertig (Citation2017) see as a ‘significant and relatively under-utilised idea in the literature on organising in educational institutions’ (p.12).

2.5. Conclusion

The literature review identifies some critical themes of distributed leadership, which assist in creating categories to examine the enactment of DES CL 003/2018 and show how dominant socio-economic and political thinking of the day influences school leadership models. Furthermore, the literature on leadership practice considers the ideological dimensions of micropolitics and accountability. At the same time, the literature recognises that the principal plays a crucial role in determining the success of change initiatives and distributed leadership; however, a focused lens on the principal's views and opinions regarding its implementation process is not evident in the literature. It is apparent from the literature that the contextual nature of school leadership influences the implementation process of distributed leadership, with power, politics, and accountability influencing the process.

3. Research methodology

A case study research methodology was selected to investigate the implementation of DES CL003/2018 concerning changes to the leadership and management structure in post-primary schools from the perspective of the voluntary secondary school principal. Overall, this study involved two phases of data collection. Firstly, questionnaires were completed by principals in voluntary secondary schools, which was followed by semi-structured interviews with principals. The research was conducted in alignment with university ethics guidelines which includes a code of conduct for researchers’ actions and the protection of individual participants. The research proposal received full ethical approval at university level. The research study relies solely on the principal voice as its primary source of information. The findings are a snapshot of post-primary school principals in a voluntary secondary school setting during a set period in 2021.

The survey questionnaires were designed and distributed to a census sample of 366 school principals in voluntary secondary schools in Ireland) through the Qualtrics online platform. As the participant ID function on Qualtrics was deactivated on the online survey platform to conduct an ethical audit trail, ID codes were assigned for survey participants in a classic sequential format by using the auto-filling function in Excel, starting with # 01 in the first row to #61 for the final row. A total of 61 participants completed the online questionnaire, giving a response rate of 16.5% of the population. Following best practice advice (Connolly Citation2007), the percentages listed relate to those who answered the question. The quantitative data was analysed using Qualtrix and Excel spreadsheets. The ordinal data emerged from a mixture of closed and open questions using a Likert scale. Univariate analysis was applied to data collection from the online survey using descriptive statistics, which, according to Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2018), researchers can analyse and interpret what these descriptions mean. Descriptive statistics suited the process appropriately, as no hypothesis was under investigation. Of the respondents to the survey, twenty-four have been principals for more than ten years, twenty are between 5 and 10 years, and 17 are less than five years. On school size, thirty principals are in a school with less than 500 students, twenty-six principals have between 500 and 900 students, and five are principals with more than 900 students.

During the qualitative phase, ten school principals from the voluntary secondary school sector participated in individual semi-structured interviews for this research via Zoom, and the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The sampling of interview subjects was purposive and based on a balance of gender, school type, size, and length of service as a principal. The size of the school was essential to reflect the number of assistant principal positions in the school because schools are assigned assistant principal positions based on the number of fulltime teachers employed which in turn is based on the number of pupils enrolled.

A rigorous and systematic approach was used for coding and analysis. Data were analysed following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2013) six-step approach to thematic analysis using the qualitative data analysis software Nvivo Pro. This involved reading the transcripts and recording initial nodes/ codes, developing categories, coding on, data reduction and consolidation. Both a deductive and inductive approach to thematic analysis was employed. Thematic analysis identifies themes in the data, with emerging patterns used to address the research questions. Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) differentiate between two levels of themes: semantic and latent. Semantic themes represent the superficial meanings apparent in the data, where the analyst primarily focuses on the explicit content of what participants have expressed. Conversely, the latent level delves into the underlying concepts and assumptions that influence the semantic content of the data. In this study, themes were identified at both levels with a focus on interpreting and elucidating the participants’ statements.

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness of the findings, the methodological approach is logical, systematic and rigorous. Data gathering approaches are consistently applied across all participants. The researchers analysed and considered the data over a prolonged period and an audit trail was maintained throughout. The transcription of the recorded interviews and the use of NVivo software helps to reduce bias through the generation of themes for comparison and analysis. The systematic approach to analysis ensures that the findings are derived from the data and detailed notes were maintained relating to the development of themes. Triangulation occurs by identifying consistent patterns across the quantitative and qualitative research findings; using multiple sources of evidence, including questionnaires and interviews, to assist the triangulation process and allows the researcher to examine the evidence from different perspectives. Each interview participant received a copy of their interview transcripts in this research, and no changes were requested as all participants felt the transcript provided a true reflection of their responses.

4. Findings

The quantitative and qualitative data analysis shows a broadly positive response to DES CL 003/2018 from the principals’ perspective. The data gathered in this research study identifies that the establishment of a distributed leadership model is underway in schools and that future policy development on school leadership can build on this progress. The findings from the survey and interviews are presented below under the following headings: micropolitics, the role of the Principal and implementation challenges.

4.1. Micro-politics

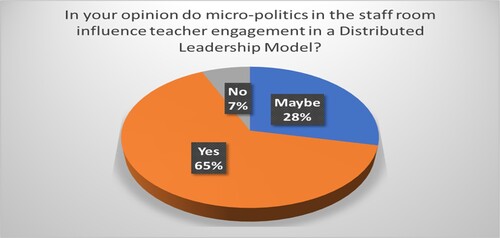

The research findings support the literature concerning the impact of micro-politics within the school environment on implementing a distributed leadership framework. The qualitative and quantitative data findings correlate with the literature on the influence of power within the concept of distributed leadership.

In the survey and interview data, principals are cognisant of the micro-politics in the staffroom during the change process, as indicated in above, with most viewing the influence of staffroom micro-politics on the process as primarily positive. Furthermore, the principals in this research study recognise that teachers have agency due to the collaborative nature of the policy consultation phase. The principals were required to skilfully negotiate the political climate of the staffroom to maintain a delicate balance between staff and to ensure that no one person or cohort felt alienated or discouraged from engaging in the new leadership framework. The powerful influence of micro-politics is articulated by participant R.18 as follows:

There are also long-standing traditions in Irish secondary schools of ‘waiting your turn’. CL 3/18 has shifted this slightly, but it will take a long time. In any working environment, there are different personalities that can direct the way things go in a staff room. Certain personalities’ previous interactions with staff (or conflicts, most likely) can make other staff slow to engage or come forward because they are aware of what has happened with or to others in the past. (R.18)

In the initial stages, some younger teachers were made to feel they did not have enough experience to apply the assumption that the longer you were in the school, the more ‘likely’ or ‘entitled’ you may be to succeed. This no longer appears to exist. (R.50)

The AP1's get it. They get a sense that they are there as part of management, as part of leadership and that they, you know, are, and even I suppose when we were closed, they were hugely important in keeping everything going. The others don't see their role quite so much as being, you know, as whole school leaders. (P.4)

4.2. The role of the principal

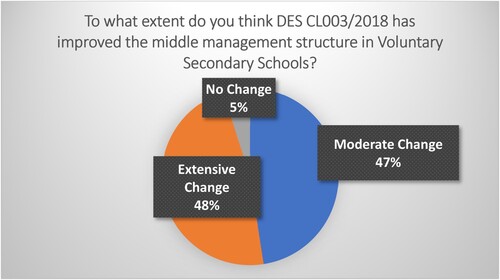

The research sought to discover if the principal's role changed within the school while implementing DES CL003/2018. Most principals agree that DES CL003/2018 changed the leadership structure to varying degrees, as indicated in .

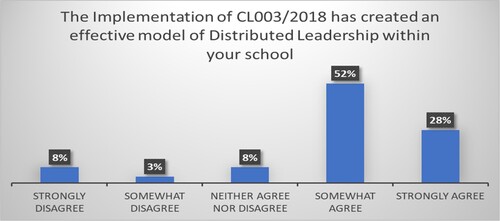

Almost all principals confirmed that DES CL 003/2018 resulted in either moderate or extensive improvement to the middle management structure in voluntary secondary schools. Of importance is the collaborative and consultative nature of the DES CL 003/2018 with the creation of a leadership team within the school, whereby the role of the principal as the figurehead who has a solution to all problems diminishes, and a leader who facilitates and seeks collective consensus emerges, as illustrated in .

The research findings confirm that the role of the principal has evolved with the distributed leadership approach, and principals welcome the concept of distributed leadership with the support of a leadership team to implement curriculum and policy initiatives to improve the learning experience for students. Despite this, the practical application of the circular remains challenging considering the realities of schools, as explained by participant R.50.

It has allowed for more effective distributed leadership, but without an allocation of hours, particularly at the AP1 level, the complete realisation of leadership being distributed is unattainable. (R.50)

With only 28% strongly agreeing, for the majority of schools there is still a distance to travel in order to change the culture and practice of distributed leadership, as highlighted by participant R. 45.

I think there is still a culture of seeing school leadership as just the responsibility of the Principal and Deputy. This will take time; however, the inspectorate, through the WSE-MLL process, are part of getting this message across to teachers. (R.45)

4.3. Challenges to implementation

Principals identify the challenges of implementing DES CL003/2018 as a lack of professional learning and support, the accountability structure, and lack of time.

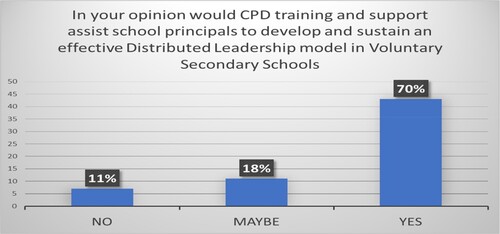

4.4. Lack of professional learning & support

Principals strongly saw the need for ongoing professional learning for themselves, as shown below in . They also recognise the need for assistant principals to undertake professional learning in leadership skills and teamwork, the lack of which was described as a ‘skill deficit’ within leadership teams (P.5).

There was also an awareness of the need for ongoing support and professional learning for principals in implementing and developing the concept and practice of distributed leadership. The principals acknowledge the provision of seminars and information sessions by the voluntary secondary school sector Joint Managerial Body (JMB); however, the session mainly focused on specific aspects of implementing DES CL003/2018 such as the recruitment and selection process. A need for greater support in relation to a developing an understanding within staff teams of the concept and principles of distributed leadership is also required as highlighted in the quote from participant P.7 below.

Look at the breakdown of the circular; I think there might be a page, a page and maybe two pages on the principles behind it. You know, obviously, Looking at Our School (LAOS) and different things like that, but there's so much training on not getting it wrong in terms of avoiding an appeal, making sure you know the advertisements on a notice board or every notice board or digitally. I think the focus on, you know, these trivial really aspects, as opposed to the principles of leadership, is a key deficit in all of this. (P.7)

4.5. Accountability structure

In an age of accountability, principals express concern about whether there is a functional mechanism for accountability and whether the annual review process adequately serves that purpose. Principals mention their accountability to the Board of Management and the Department of Education inspectorate. Principals observe that there appears to remain a perception of the principal as having the ultimate responsibility, and the extent of assistant principals’ responsibility is vague. Principals have mixed views on the accountability mechanism provided in the review and feedback element of DES CL003/2018. indicates a mixed view on shared responsibility and accountability.

This perception is exemplified by a quote from participant P.9 who states:

I think a lot of the accountability and responsibility comes back to me or whoever is the principal in whatever school because, ultimately you have to report back to the Board. So, the oversight does come back to here. (P.9)

I’ve gained far less from the annual review meetings than I thought I would. I found them box-ticking, largely. This is what I do. The same people who exceed expectations are doing it, and the same people who don't are doing it, and they'll frame it to make it look like they're doing more. I could go and cause a lot of issues by completely renegotiating roles, but there's no point in doing that. (P.3)

4.6. Lack of time

Regarding changes, additions, or amendments for future leadership development, most principals raised the lack of time to hold meetings with assistant principals both as a team and the time for them to discharge their leadership functions outside of their teaching timetable. There was a distinct view that even though assistant principals received remuneration, they needed more time to discharge their role, particularly AP1 post holders. Assistant principals generally teach a full timetable, and there is no time allowance provided in DES CL003/2018 for undertaking the duties they have been allocated. In the voluntary secondary school sector, a reduction in teaching hours may be allowed for assistant principals, but only depending on the resources available within the school's yearly allocation. The Education and Training Board (ETB) sector generally provides up to four hours weekly for API posts. In the absence of official time, principals in voluntary secondary schools are obliged to find time within the school allocation, which proves very difficult in some cases, with the amount of time varying from school to school. Principals in voluntary secondary schools indicate they are finding it increasingly difficult to facilitate the allocation of hours for assistant principals with the many competing demands and new initiatives. Comparing the situation to another jurisdiction one Principal commented as follows:

My understanding is that if you're in senior or middle management in England, you might only have half a teaching timetable, and the rest of your time is supporting management. I've to take people out of class to get them to do that; that's not good. (P.3)

The main issue with Distributed Leadership is the time needed for those to whom leadership is distributed to undertake their tasks. Whether AP1 or AP2, the middle leader can only engage with the model effectively if they have the time to do so. If the DES is to give any further consideration to the model, it should be the provision of protected time for middle management to manage. (R.44)

5. Discussion

Reflecting on the data gathered in this research study it is apparent that establishing a distributed leadership model is underway in schools, and future policy development on school leadership can build on this progress. The procedures for recruitment and selection to leadership posts have established a competency-based approach broadly welcomed by the principals who participated in this research study.

5.1. Micropolitics

The research notes that principals experienced a shift in the dynamic of staff engagement with the process once the initial concerns regarding the loss of the seniority criterion dissipated. The influence of the micro-political atmosphere of the staffroom on the implementation of distributed leadership changed by the time the principal was leading the biennial review, a crucial finding, as it opens the door to leadership development on a whole school collective basis (Harris Citation2014).

The division between API and APII posts emerge in the research, with a considerable difference in remuneration and role status within the school. The categorisation and inequality present a dichotomy in a distributed leadership model of creating teams and collaboration. Principals acknowledge staff perceptions of the differences between API and APII positions and the subsequent challenges within the school culture to validate the significance and contribution of the APII post holder to the leadership team and how principals manage any power imbalance, whether real or perceived, is critical for implementing distributed leadership (Murphy Citation2009).

5.2. Accountability

The research shows that principals do not view the end-of-year review meeting as an effective accountability measure; there appears to be a need for more consistency of approach in schools to this part of DES CL003/2018. Principals understand that a performance review meeting requires skills and a clear understanding of the process. However, principals express a clear need for enhanced clarity and professional development regarding this aspect of the circular. Currently, it's being addressed on an ad hoc basis, relying on individual school discretion rather than a consistent, systemic approach. Moreover, in the context of a whole school inspection (Ehren and Perryman Citation2017), if an issue arises regarding a leadership aspect within an assistant principal's remit, such as school self-evaluation, the accountability during an external inspection remains unclear. It's uncertain whether the principal or the assigned assistant principal will be accountable to the inspectorate.

5.3. The principal’s role

It is clear from the research that DES CL003/2018 has changed the principal's role to varying degrees. Forming leadership teams and distributing leadership responsibilities require a change in leadership style, letting go, and deepening trust and collaboration (Duignan Citation2006; Spillane Citation2006). Creating a framework for distributed leadership dilutes the idea of a sole leader and strengthens collaborative leadership within the school. The research findings confirm that the role of the principal has evolved with distributed leadership and that principals welcome the concept of distributed leadership with the support of a leadership team to implement curriculum and policy initiatives to improve the learning experience for students. However, concerns are also evident within the broader context of the emerging distributed leadership structure in the voluntary secondary school.

5.4. Professional learning & support

Once such concern identified by participants is a need to have access to leadership skills-based professional learning for assistant principals in the school (Kavanagh Citation2020; Kavanagh Citation2020). All principals identify a need for a more accessible and structured professional learning model for assistant principals through onsite or off-site delivery.

The need for principals to receive ongoing support and learning of a skills-based nature also emerges as an essential component for the successful implementation of distributed leadership. King and Nihill (Citation2019) explain that ‘teachers engage voluntarily in professional learning, but it is not a requirement for career advancement, and the absence of any mandatory qualification for appointment to senior school leadership is an example of this lack of prioritisation of ongoing learning in the profession’ (p.7).

The Centre for School Leadership (CSL) (Citation2018) which is now incorporated into Oide, the national support service for teachers and school leaders in Ireland acknowledged the need for ongoing and enhanced leadership development within the school leadership framework. It suggests that a ‘well-constructed continuum also provides a framework for aspiring and serving school leaders at different levels to plan their learning partway’ (p.14).

5.5. Time

The demands of timetabling the teaching requirements for individual assistant principals and the necessity to timetable leadership team meetings are causing tensions for principals. If the leadership team does not meet and communicate regularly, the vision and the effectiveness of distributed leadership within the school will be considerably reduced.

The second issue of concern for principals around time is the absence of a time allowance for assistant principals in the voluntary school sector to discharge their leadership roles. A principal can effectively delegate leadership responsibilities to an assistant principal in a distributed manner only when there is ample time for the assistant principal to fulfil the role effectively. The challenge of time reported in this study raises a question regarding the ability of school principals to communicate and engage with assistant principals in a meaningful and productive manner.

6. Conclusion & recommendations

To conclude, the full potential of a distributed leadership model in action is currently not fully realised, and schools are at various stages of development operating within their particular context and resources. Interestingly, the findings create a significant commonality of perspectives within the contextual environments and experiences of the post-primary school principals in the voluntary school sector.

This study found that the underlying concepts of power and accountability fundamentally impact the principal's perspective on implementing distributed leadership. Micro-politics influenced the implementation of the distributed leadership process in the early stages of enactment. In addition, while accountability exists within the implementation phase for assistant principals, creating a structure to clarify and measure the level of accountability within a distributed leadership model requires further consideration. This research indicates that principals have fostered and developed a positive attitude among school staff towards a distributed leadership model.

Considering the findings of this research it is evident that they correlate with the literature on distributed leadership, which highlights the significant role played by the school principal in successfully embedding distributed leadership in the school. As such, the current research recommends that school principals in the voluntary secondary school sector receive the ongoing support and resources required to successfully implement, maintain, and develop a distributed leadership model.

To further support the enactment of DES CL003/2018, several recommendations are advised including the provision of professional learning for principals and leadership teams, and the allocation of dedicated time for assistant principals to carry out their leadership roles working collaboratively as authentic members of the school leadership team. Further, policymakers should ensure that the concept of distributed leadership is integrated in the professional learning experiences designed for school leaders and teachers.

More specifically, it is recommended that principals are offered professional learning on how to effectively carry out annual review meetings with assistant principals. In addition, it is recommended that onsite, sustained and externally facilitated professional learning would be afforded to school leadership teams to provide context-specific guidance focusing on the school's vision and ethos. This would foster an authentic, collaborative culture conducive to distributed leadership implementation and a shared understanding of school leadership in action. Professional learning of this nature may support self-reflection and the identification of the team's strengths and challenges so as to create a sense of team cohesion and purpose rather than a series of individual leaders within the school.

Schools work within a time constraint and in the absence of dedicated ring-fenced time for leadership teams to meet discuss and plan it is difficult to see how distributed leadership can effectively operate. The current findings show that a principal, though willing, cannot devolve a leadership role to an assistant principal in its entirety because the principal or deputy principal often must undertake elements of an assistant principal’s role due to their teaching timetable. Therefore, it is recommended that additional resources are provided to schools, not only to allow assistant principals to carry out their allocated duties through a reduction in their teaching hours but also to facilitate meetings of the leadership team at least once every term. A comparative research study on time allocation provided to schools in other jurisdictions to assist the implementation and sustainability of distributed leadership might support this recommendation.

Further consideration by policy makers and researchers is required in relation to the concept and practice of accountability within the distributed leadership model. Distributing leadership without distributing accountability suggests a need to explore how these aspects of the model would operate. However, one could argue that it is unreasonable to expect assistant principals to be accountable for roles for which no dedicated time has been allocated.

Finally, the words of Popper, as cited by Magee (Citation1973), reminds us that ‘nothing that is not a proposal can ever be put into practice. Therefore, what matters in politics or in science, is not the analysis of concepts but the critical discussion of theories and their subjection to the tests of experience’ (p.107). Bearing this in mind we must continue to discuss, research, and explore the implementation of distributed leadership by capturing the voices and lived experiences of principals, leadership teams and teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maree O’Rourke

Dr Maree O'Rourke is a post-primary school principal and a research associate with Dublin City University, Centre for Evaluation, Quality and Inspection. She is also a leadership associate with Oide, the national teacher support service in Ireland.

References

- Abadzi, H. 2017. Paper commissioned for the 2017/8 Global Education Monitoring Report, Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments”. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259573.

- Ball, S. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” The Australian Journal of Education Studies 13 (2): 10–17. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249913509_What_Is_Policy_Texts_Trajectories_and_Toolboxes.

- Bonneville, D. 2017. Demystifying Distributed Leadership: How Understanding Principles of Practice and Perceptions Regarding Ambiguity Can Enhance the Leadership Capacity of Department Chairs. Available from: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/937Citation.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE Publication.

- Butler, P. 2024. “Building a Coaching Culture in Irish Schools; Challenges and Opportunities: A Mixed-Methods Study.” Societies 14: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010010.

- Camburn, E., and S. Han. 2009. “Investigating Connections Between Distributed Leadership and Instructional Change.” In Distributed Leadership: Different Perspectives, edited by A. Harris, 25–46. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Centre for School Leadership (CSL). 2018. Innovation through Collaborative Leadership and Management. Available from: www.cslireland.ie/images/downloads/leadershipclusters/.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education. 8th Edition. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138209886.

- Connolly, P. 2007. Quantitative Data Analysis in Education: A Critical Introduction Using SPSS. London: Routledge.

- Connolly, M., C. James, and M. Fertig. 2017. “The Difference Between Educational Management and Educational Leadership and the Importance of Educational Responsibility.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 47 (4): 504–519.

- Department of Education (DE). 2022. Looking at our Schools 2016 Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools [online]. Available from file:///C:/Users/mor1/Downloads/232730_4afcbe10-7c78-4b49-a36d-e0349a9f8fb7.pdf.

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education. From The Collected Works of John Dewey: The Middle Years, vol. 9, edited by JoAnn Boydston.

- Diamond, J., and J. Spillane. 2016. “School Leadership and Management from a Distributed Perspective: A 2016 Retrospective and Prospective.” Management in Education 30 (4): 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616665938 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309268503_School_leadership_and_management_from_a_distributed_perspective_A_2016_retrospective_and_prospective.

- Duignan, P. 2006. “Ethical Leadership: Key Challenges and Tensions. Melbourne, Cambridge University Press Countries.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 25 (1): 3–43. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11092-012-9156-4.

- Ehren, M., and J. Perryman. 2017. “Accountability of School Networks: Who is Accountable to Whom and for What?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46 (6): 942–959. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318660752_Accountability_of_school_networks_Who_is_accountable_to_whom_and_for_what.

- Forde, C., G. Hamilton, M. Ní Bhróithe, M. Nihill, and A. Rooney. 2019. “Evolving Policy Paradigms of Middle Leadership in Scottish and Irish Education: Implications for Middle Leadership Professional Development.” School Leadership & Management 39 (3-4): 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1539962

- Giudici, A. 2020. Teacher Politics Bottom-up: Theorising the Impact of Micro-Politics on Policy Generation. Oxford, UK: Department of Politics & International Relations, University of Oxford.

- Gómez-Hurtado, I., I. González-Falcón, J. M. Coronel-Llamas, and M. D. P. García-Rodríguez. 2020. “Distributing Leadership or Distributing Tasks? The Practice of Distributed Leadership by Management and Its Limitations in Two Spanish Secondary Schools.” Education Sciences 10: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10050122. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340946898_Distributing_Leadership_or_Distributing_Tasks_The_Practice_of_Distributed_Leadership_by_Management_and_Its_Limitations_in_Two_Spanish_Secondary_Schools/citation/download.

- Gronn, P. 2009. “Leadership Configurations.” Leadership 5 (3): 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715009337770. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247765278_Leadership_Configurations.

- Harris, A. 2008. “Distributed Leadership: According to the Evidence.” Journal of Educational Administration 46: 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810863253.

- Harris, A. 2014. Distributed Leadership. Available from: https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/article/distributed-leadership.

- Hickey, N., A. Flaherty, and P. Mannix McNamara. 2022. “Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research.” Societies 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010015

- Irvine, J. 2020. “Distributed Leadership in Practice: A Modified Delphi Method Study.” Journal of Instructional Pedagogies 25: 1–29.

- Kavanagh, S. 2020. “The Professional Development Needs of Appointed Middle Leaders in Education and Training Board, Post-Primary Schools.” (Doctor of Education thesis). Dublin City University. Available from: https://doras.dcu.ie/25009/.

- King, F., and M. Nihill. 2019. “The Impact of Policy on Leadership Practice in the Irish Educational Context; Implications for Research.” Irish Teachers’ Journal 7 (1): 57–74. [Open Access https://doras.dcu.ie/23969/1/Impactofpolicyonleadershippractice-withadditionalrevisions.pdf.

- King, F., and H. Stevenson. 2017. “Generating Change from Below: What Role for Leadership from Above?” Journal of Educational Administration 55 (6): 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-07-2016-0074 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316984798_Generating_change_from_below_what_role_for_leadership_from_above.

- Kołczyńska, M. 2020. “Democratic Values, Education, and Political Trust.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 61 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715220909881

- Lahtero, T. J., R. S. Ahtiainen, and N. Lång. 2019. Finnish Principals: Leadership Training and Views on Distributed Leadership. Available from: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/304896/2019_Lahtero_Ahtiainen_L_ng_Distributed_leadership.pdf?sequence = 1.

- Lahtero, T. J., N. Lång, and J. Alava. 2017. “Distributed Leadership in Practice in Finnish Schools.” School Leadership & Management 37 (3): 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1293638

- Liu, Y. 2020. “Focusing on the Practice of Distributed Leadership: The International Evidence from the 2013 TALIS.” Educational Administration Quarterly 56 (5): 779–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20907128.

- Lumby, J. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: The Uses and Abuses of Power.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 41 (5), https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213489288.

- Magee, B. 1973. Popper. UK: Fontana Paperback.

- Mifsud, D. 2017. “Distributed Leadership in a Maltese College: The Voices of Those among Whom Leadership is ‘Distributed’ and who Concurrently Narrate Themselves as Leadership ‘Distributors’.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 20 (2): 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1018335.

- Moynihan, J., and M. O’Donovan. 2021. “Learning and Teaching: The Extent to Which School Principals in Irish Voluntary Secondary Schools Enable Collaborative Practice.” Irish Educational Studies 41: 1–18. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350109514_Learning_and_teaching_the_extent_to_which_school_principals_in_Irish_voluntary_secondary_schools_enable_collaborative_practice.

- Murphy, G. 2019. “A systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Research on School Leadership in the Republic of Ireland: 2008–2018.” Journal of Educational Administration. Available from: https://www-emeraldcom.dcu.idm.oclc.org/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JEA-11-2018-0211/full/html.

- Murphy, G. 2023. “Leadership Preparation, Career Pathways and the Policy Context: Irish Novice Principals’ Perceptions of Their Experiences.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 51 (1): 30–51.

- Murphy, G., and T. Brennan. 2022. “Enacting Distributed Leadership in the Republic of Ireland: Assessing Primary School Principals’ Developmental Needs Using Constructive Developmental Theory.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 52 (3): 666–685.

- Murphy, J., and L. K. Seashore. 2018. Positive School Leadership: Building Capacity and Strengthening Relationships. New York: Teacher College Press Colombia.

- Nishiyama, K. 2021. “Democratic Education in the Fourth Generation of Deliberative Democracy.” Theory and Research in Education 19 (2): 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785211017102

- OECD. 2008. Pont B., Nusche, D. & Moorman, H. (2008) Improving School Leadership Volume 1: Policy and Practice. OECD. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/44374889.pdf.

- Piot, L., and G. Kelchtermans. 2015. “The Micropolitics of Distributed Leadership: Four Case Studies of School Federations.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44, https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214559224. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277307201_The_Micropolitics_of_Distributed_Leadership_Four_Case_Studies_of_School_Federations/citation/download.

- Printy, S., and Y. Liu. 2020. “Distributed Leadership Globally: The Interactive Nature of Principal and Teacher Leadership in 32 Countries.” Educational Administration Quarterly 57 (2): 290–325. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341792868_Distributed_Leadership_Globally_The_Interactive_Nature_of_Principal_and_Teacher_Leadership_in_32_Countries.

- Rashid, F. 2015. Mutual Accountability and Its Influence on Team Performance. Doctoral Dissertation. Cambridge: Harvard University Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Available from: https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/14226095/RASHID-DISSERTATION-2015.pdf?sequence = 4.

- Redmond, M. 2016. Affective Attunement- Emotion & Collaboration – A Study of Irelands Voluntary Secondary School Principals. Available from: https://www.jmb.ie/Site-Search/resource/246 file:///C:/Users/mor1/Downloads/Affective%20Attunement%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Ireland's%20Voluntary%20Secondary%20Principals.pdf.

- Sant, E. 2019. “Democratic Education: A Theoretical Review (2006–2017).” Review of Educational Research 89 (5): 655–696. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493

- Spillane, J. P. 2006. Distributed Leadership, Distributed Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Spillane, J. P., and L. Anderson. 2019. Negotiating Policy Meanings in School Administrative Practice: Professionalism, and High Stakes Accountability in a Shifting Policy Environment Northwestern University Connecticut College – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335018576_Negotiating_Policy_Meanings_in_School_Administrative_Practice_Practice_Professionalism_and_High.

- Spillane, J. P., and J. B. Diamond. 2007. Distributed Leadership in Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Spillane, J., R. Halverson, and J. Diamond. 2001. “Investigating School Leadership Practice: A Distributed Perspective.” Educational Researcher 30 (3): 23–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030003023 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/246537076_Investigating_School_Leadership_practice_A_Distributed_Perspective.

- Tahir, L. M., S. L. Lee, M. B. Musah, H. Jaffri, M. N. H. M. Said, and M. H. M. Yasin. 2016. “Challenges in Distributed Leadership: Evidence from the Perspective of Headteachers.” International Journal of Educational Management 30 (6): 848–863. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2015-0014.

- Tenuto, P. L. 2014. “Advancing Leadership: A Model for Cultivating Democratic Professional Practice in Education.” SAGE Open 4 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014530729

- Tian, M., M. Risku, and K. Collin. 2016. “A Meta-Analysis of Distributed Leadership from 2002 to 2013: Theory Development, Empirical Evidence, and Future Research Focus.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44 (1): 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214558576.