ABSTRACT

The article traces the beginnings of the powerful liaison between automobile technology, tourism, and the ‘Land of the Fjords’. Focusing on the German automobile club ADAC in the period 1920s to 1960s, the article examines how German motorists discovered and embraced Norwegian roads, and what idea of the ‘Norway experience’ was constructed along the way. Tourists, it is argued, were primed for car travel through the narratives of contrasting vistas and sublime nature stemming from the time Norway was experienced by cruise and cariole. During the German occupation of Norway 1940–1945, narratives and pictures of Norwegian landscapes were spread among Germans as never before; now combined with narratives of heroism, conquest, and technology. In the 1950s, when West Germany was experiencing the onset of mass tourism and mass motorization, the concept of the extraordinary car trip on Norway’s roads was ready to be widely communicated and put into praxis. Postwar ‘Grand Tours on wheels’ to Scandinavia were both continuing narratives on Northern remoteness and otherness, and ‘silencing’ historical landscapes of war. By the mid-1960s, Norway had been established as a superb car travellers’ destination, a sanctuary of nature just accessible by a car.

Introduction

My family keeps an untitled photo album, which belonged to my great-uncle (1915–2010) from Berlin. ‘Start on 2 August 1953 for the Scandinavian journey’ is written on the first page. You can see my great-uncle with his newly-wed wife, standing together in a Berlin street, next to their companion for the following four weeks: A van borrowed from the in-laws’ laundry. Whenever a country border was crossed during the following month, a new pennant was proudly displayed on the hood – at the end of the journey, there were German, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian pennants (). The pictures, postcards, and drawings collected in their album show their fascination for Scandinavian landscapes, cultural sights, camping, and car travelling. On a postcard home, tucked between the album pages, they mention in particular the diversity of the Norwegian landscapes. Travelling northwards, for them, was a goal in motion, not a place they could reach.

Figure 1. Photograph from a Scandinavian journey done by a German couple in 1953, titled ‘By the Trondheim fjord’. Private.

Eight years after World War II, my great-uncle and his wife must have been one of the first German car tourists in Scandinavia after the war. With their self-made camping car, they practiced a tourism culture that is highly professionalized and self-evident today, at least as far as Norway is concerned: In 2019, 61% of foreign tourists in Norway travelled through the country by car, among these German tourists were the largest group of them.Footnote1 While other countries have internationally renowned tourist resorts tailored for longer stays, this is not the case in Norway. At most, we find stops along the way (for example Bryggen in Bergen and the Geiranger fjord) and well-known roads like the E6 and the Atlantic route. Norway is covered by a network of campsites, rest stops, hotels, tourist signs, and specially designated scenic routes. The state project Nasjonale turistveger (Norwegian Scenic Routes), realized through huge investments since 1994, is a recent evidence that Norway is prioritizing car tourism.Footnote2

This article traces the beginnings of this powerful liaison between automobile technology, tourism, and the ‘Land of the Fjords’. Focusing on the activities and writings of the German automobile club ADAC in the period 1920s to 1960s, this study examines how German motorists discovered and embraced Norwegian roads, and what idea of the ‘Norway experience’ was constructed along the way. Which images of country, people, and nature were sustained, challenged, and redefined by the car? What steps made the car not only fit into the coastal landscapes and the fjords, but also become a preferred means of travel and landscape experience? And finally, what role did the German occupation of Norway 1940–1945 play in this bilateral history of tourism?

The premise of the article is the observation that the development of tourist destinations depends not only on infrastructural development, legal regulations, economic aspects, and right to rest and leisure, but also on certain, circulating narratives and images that construct a ‘tourist gaze’.Footnote3 This often-quoted term by sociologist John Urry helps to describe that what people are looking for as tourists ‘varies by society, by social group and by historical period’ and is shaped by the tourists’ own social, cultural and political background.Footnote4 In this understanding, the communicative construction of what is ‘out of ordinary’ and worth seeing, is the prerequisite of modern mass tourism. This means that an investigation of the development of Norway into a car travel destination needs a discursive and transnational approach. The analysis of the German accounts is thus only a beginning, although it focuses on a significant visitor group. This inquiry draws on several studies on automobilism and tourism in Norway, in particular on early tourism by foot or cariole and cruises by ship along the coast.Footnote5 Norway was discovered by foreigners in the late eighteenth century, and from the 1830s onwards, it became a destination for the first ‘tourists’.Footnote6 Foreign car tourism has so far only been superficially researched.Footnote7

Another seminal theoretical lens of this article is the technological system of road, car, and windscreen, and how it ‘mediates’ nature, together with other technologies.Footnote8 Automobility has been described as requisite, companion, and reflection of modern lifestyle and societal ideas of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, where the car is closely connected to ideas of individuality, flexibility, freedom, and adventure, but also everyday-life.Footnote9 Infrastructure, travelling, and perception of landscapes have always been closely intertwined.Footnote10 While the railway journey revolutionized time, space, and landscape in the nineteenth century, the windscreen has redefined how we experience the world in the twentieth century.Footnote11 Several studies have observed how, particularly in North America, the car has redesigned the idea of nature and wilderness.Footnote12 The ‘windscreen’ is understood both literally as a frame that creates constantly changing landscape vistas, and in a figurative sense as the automobile technology that both enables, mediates, and creates nature experience. This article aims to apply these perspectives on automobility and the mediation of nature to a European case, and expand the discussion further by including border crossing, national identity, and bilateral relations.Footnote13

The article’s analytical gaze concentrates on the German automobile club ADAC, today Europe’s largest automobile association by its 21 million members.Footnote14 Founded in 1903 as Deutscher Motorradfahrer-Vereinigung (German motorcyclist’s association) and changed to Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club (General German Automobile Club) in 1911, it soon became the leading advocate and information channel for German motorists. In 1930, 140,000 Germans were members, and in 1965, the one millionth member was celebrated.Footnote15 ADAC established its own tourism department in 1924,Footnote16 which has since produced large amounts of information material, maps, travel guides, marketing brochures, and package tours. By this ADAC had a massive impact on the travels of Germans, and thus played a remarkable role in the history of leisure and landscapes in Europe in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. However, ADAC has so far been overlooked as a central agent in the history of tourism.Footnote17

The article’s main source material is ADAC-publications, especially the club magazine ADAC-Motorwelt. This is an outstanding source published monthly from 1925 (the precursor Der Motorfahrer was published from as early as 1903), with a break between August 1944 and August 1948.Footnote18 The title ‘motor world’ is telling, as the magazine narrates a world defined by the engine’s possibilities in companionship with the mobile human. In ADAC-Motorwelt, ADAC discussed both technological development, societal changes, and its own practices – and, not least, tourist destinations, ways to travel, and to meet the world as a tourist. Contemporaneous tourist literature is also consulted in this article. The selection criterion for these additional publications is based on their renown and popularity.

The study is limited to the period from the 1920s to the 1960s. The starting point is not a car trip, but a cruise by ship for ADAC members along the Norwegian coast in 1929. At that time, however, the Norwegian inland routes were already thematized in various German travel guides. In the 1960s, which has been described as the German ‘take-off of mass tourism’,Footnote19 the idea of Norway as a travel destination by car was established. According to ADAC-Motorwelt, car travels on Norwegian roads were no longer an ‘expedition’,Footnote20 and later travel guides and travelogues were variations on the established theme.

Cruising northwards

The first time the ADAC guided its members to Norway was in 1929. This year, the club organized a Nordlandfahrt – a three-week club cruise from Hamburg and along the Norwegian coast to the North Cape, run by the shipping company Hapag with its 9,000 tonnage steamer Oceana. The tour was the main story of several ADAC-Motorwelt issues in 1929, in order to promote the cruise ahead of the journey and to report on the travel experience after the fact. The coastal landscape of Norway up to the North Cape was the tour’s main attraction: ‘Northwards, ADAC-wanderer, your tour is heading this time!’ the first article began.Footnote21 Norway was characterized as a land of ‘harsh majestic beauty’, of ‘Gods and sagas’, of a ‘ragged coast’ and ‘blue fjords’.Footnote22 The traveller was to be overwhelmed by the ‘contrasting coexistence of cycloptic immenseness and lovely gracefulness’, and by ‘the sublime solitude of the North Cape’.Footnote23 The stimulating changes of impressions were to make passengers forget the ‘monotonousness of everyday life’.Footnote24

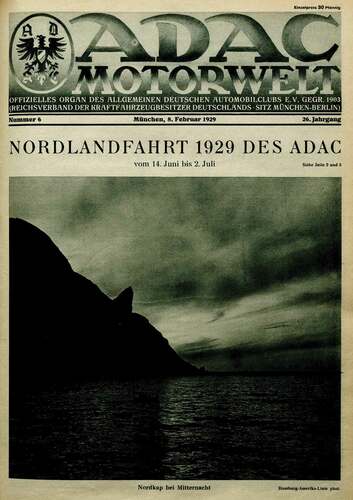

In this very first paragraph about Norway in ADAC-Motorwelt, all that characterized Norway in 1929 and in the following decades, was introduced: the fjords, the northern remoteness, the Viking history, the sublime landscapes, and the breath-taking contrasts en route. Norway was a land defined by extremes, specifically the clash of land and sea. It was not a destination to travel to and to stay in, but to travel through or alongside. The traveller’s direction was northwards, aiming for the North Cape, which ADAC-Motorwelt introduced by a dramatic cover in February 1929 ().

Figure 2. Cover of ADAC-Motorwelt 26, no. 6 (1929) © Reprinted with the kind permission of ADAC e.V., Communication and Editorial Department. Provided by www.zwischengas.com/archiv.

This Norway was not only an ADAC concoction. A Nordlandfahrt was built on a well-established concept of German tourism. Kaiser Wilhelm II (r.1888–1918) had started sailing through Norwegian fjordscapes with a group of male companions from 1889 onwards. As these sailings were covered by the German mass media, cruising northwards like the Kaiser became popular when offered by shipping companies for a larger group of German tourists.Footnote25 The Norwegian landscapes became a promised land – a mythic, pre-industrial, and apolitical region far away from the accelerations of modern urban life, political and social tensions, complaints and ‘demoralization’.Footnote26 Nordland seemed to be what the Reich was not, and symbolized the lives Germans wanted to live. Heroic narratives of human struggles with nature became connected to Northern-ness by the celebrities of Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, and Sven Hedin.Footnote27 ADAC’s Nordland clearly drew on popular German narratives and marketing conventions.

ADAC had organized member tours before. Collective driving tours through Germany and neighbouring countries were a central part of club life.Footnote28 Car touring was understood as the sport of mastering the engine, the road and the speed, and landscape as a means of ‘crunching miles’. The members needed landscapes to drive through and hotels to stay overnight. Tourism was the consequence of driving, not the other way around. With increasing automobile possibilities, the members sought more remote destinations. While American car drivers could explore apparently endless ‘wilderness’,Footnote29 it seems that German roads became too short for motorists.Footnote30 Americans drove to experience their own nation. Germans drove around the neighbouring countries, especially the challenging mountain roads of the Alps. In 1928, ADAC even organized a club tour by car through America.Footnote31

The tour along the Norwegian coast was something new, however. The Nordlandfahrt did not require any driving skills, wayfinding efforts, refuelling, or engine repairs – the German motorists left their ‘Adventure Machine’Footnote32 at home. The essence of what it meant to be a motorist was no longer needed. The freedom, flexibility, and individuality connoted with automobility was replaced by a detailed schedule of a shared itinerary. There was leisure, laughter, community, luxury. The originally exclusive and masculine Norway experience in the emperor’s stern waves was now available to more people, also women and children.Footnote33

For ADAC, Norway was a country rich in natural beauty, yet the local population was hardly mentioned in the cruise descriptions. The exception was the derogatory characterization of the Sami: ‘It is a strange people who live here in primitive huts, with their depressed figures, with their colourful costumes, with their dogs and reindeers’.Footnote34 ADAC here described the indigenous people as ‘others’ the tourists could observe as in a folk exhibition. In another article, the ADAC author even expressed his slight discomfort that the presentation of the Sami with their reindeer reminded him of ‘Hagenbeck’, i.e. the zoo in Hamburg.Footnote35

The landscapes, too, were on display. The coast and fjord landscapes slid far behind the railing. Historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch noted a new landscape experience in relation to the railway journey, and described the view from the railway window as ‘panoramic’.Footnote36 The same was true for cruises along the Norwegian coast. The foreground lost its importance, while the interplay of landscapes at distance acquired a special attraction.

When the ship docked at certain locations and shore excursions were made possible, the ship’s passengers could also ‘step into’ these panoramas. Trains, carriages, and even cars were waiting for them, bringing them deeper into the country. One ADAC member, however, complained about the Norwegian driving style: Norwegians drove slowly, did not cut corners, and honked at blind spots.Footnote37 Norway was ‘not a country for German drivers’, in the rapporteur’s judgment.Footnote38

Early automobile routes

Why would ADAC bypass the car entirely when launching Nordland as a travel experience? The Norwegians’ driving style could hardly have been that daunting. Maybe an answer can be found in the contemporaneous guidebooks. It must be remembered, however, that these books were aimed at a broad German readership, not just at motorists as were the ADAC publications. We have to keep in mind that the car was still a luxury item.Footnote39 In 1919 only one in 684 Germans owned a car.Footnote40 In 1933, the relationship was one car for every 100 people.Footnote41

The most popular publishing house for German travellers at the time was Karl Baedeker. His renowned red books guided readers to German and foreign landscapes from 1835 onwards.Footnote42 In 1929, the current Baedeker about Norway (including Sweden, the routes through Denmark, Iceland, and Svalbard) was from 1914. This was the 13th edition of a guidebook published as far back as in 1879.Footnote43 These editions make clear that Norway already had a firm place on the German map of tourist-attractive countries.

In the 1914 Baedeker, travelling with ‘your own automobile’ was recommended for Denmark and Southern Sweden, but explicitly not advised for Norway.Footnote44 Surprisingly, the reason was not the condition of the roads, as the public roads were characterized as ‘excellent’.Footnote45 Legal aspects similarly presented no obstacle, as the book referred to automobile associations that could provide information on customs conditions and other regulations to bring one’s own car.Footnote46 The reason why Germans shouldn’t travel by car was that all roads ended ‘at the outermost branches of the fjords’.Footnote47 Travelling in Norway was dependent on transporting the car on a steamer, ‘which may cause difficulties’.Footnote48 Accordingly, the automobile was not suitable in Norway’s fjord landscape. Since this was Norway’s main attraction, there was no reason to car travel to Norway.

Furthermore, travelling by car was too fast for the viewer to catch all the various landscape impressions. Even if several Norwegian Skyssstasjoner (coaching inns) already provided transport by automobile, this was not a convenient way to enjoy the landscapes.Footnote49 To meet the requirements of the Norwegian nature, the traveller needed to slow down:

The sometimes expressed opinion that even the magnificent nature of the Western Norwegian fjords cannot stand comparison with the Alps, is essentially due to the haste with which many travellers hurry through the country, without allowing themselves the time to take in the different landscape vistas. Only gradually the eye of the Central and Southern European get used to the new appearance of a pure nature untouched by human hands.Footnote50

The worries about shortcomings for fast-travelling tourists can be found in other contemporary German books about Norway.Footnote51 A possible solution for Baedeker and others, could have been to guide the readers to cruise by ship along the fjords. Instead, Baedeker formulated a harsh critique on this kind of mass tourism, which did not fit the idea of travelling individually with the red guidebook as a travel companion.Footnote52 In the criticism of cruise ships and the homage to carioles, pre-automotive travel books gave an idea of what would become the attraction of travelling by car in Norway: the freedom to stop whenever and wherever the traveller chose.Footnote53

All travel guides described travelling through Norway as the main attraction. They were structured by routes, not by sightseeing vistas, places, hotels, or towns.Footnote54 The guidebooks gave the reader a choice between different routes. In this way, each journey became unique: the traveller chose which route, which combination of routes, at what pace, and where he or she would make a stop. This concept of offering tourist routes in Norway had since 1850 been professionalized by the travel bureau of the Englishman Thomas Bennett.Footnote55

The German guidebooks also paid attention to certain Norwegian roads, ‘cleverly laid out’ within a challenging topography.Footnote56 Common for these roads was their winding way through mountainous regions, along steep slopes and wide views, all of them ending in a fjord. This interest in scenic roads increased around 1930. Grieben’s guide to Norway from 1930, for example, described the Haukeli road in Southern Norway as ‘one of the most magnificent, splendid mountain roads in Norway, built 1857–87 under the greatest difficulties’.Footnote57 When Baedeker published a new guide to Norway in 1931, this book, too, praised Norwegian road construction: ‘with regard to the daringness of the construction, they are in no way inferior to the great alpine roads’.Footnote58

The Norwegian roads were not for the faint of heart. Baedeker warned its readers: ‘In the beginning, some travellers will not be able to suppress a slight discomfort on the older, hilly paths or on the sharp bends of the mountain roads’.Footnote59 This ‘slight discomfort’ was a modern variation of Edmund Burke’s sublime, referring to the aesthetics of high mountains, deep abysses, or wide oceans.Footnote60 The observer was frightened and attracted, just some metres away from danger and death. This feeling was compounded with awe and respect for engineering structures, a combination which has been called ‘the technological sublime’.Footnote61 Riding the Norwegian roads, then, was a sublime experience. These descriptions contain the seed for understanding car driving as a brave act.

The drive by car, however, was still not recommended for foreigners according to Baedeker in 1931.Footnote62 The most beautiful parts of Norway – the fjords and Northern Norway – were hardly suitable for driving. Travellers had to transport their car by steamship over longer distances; an expensive and sometimes difficult affair. The guidebook mentioned newer car ferries but did not describe them in more detail.

In 1931 ADAC contributed to the touristic discovery of Norway with five pages in Auslands-Tourenbuch (Abroad tour book), and the country was thus established as a possible destination for German motorists. The roads were described as first-rate and attractive for the car driver looking for challenging journeys:

Road conditions for car tourism are quite favourable in Norway. The country has excellent communication routes with its long roads whose conditions really could serve as a model for many other countries. The roads leading from the east and south over the mountains to the beautiful fjords of the west coast are really excellent. However, they – and even more so, of course, the roads in the far north – make certain demands on the vehicle and driver, because the mountainous stretches have numerous steep inclines and countless tight bends that often lead to dizzying heights or into the enormous depths of the cut valleys.Footnote63

Driving Norway by car, ADAC made clear, was an outstanding experience. The interruptions by steamboats were not described as obstacles as in Baedeker. Rather, the ferries gave the trip a greater experience value:

It is particularly advisable to undertake a trip combined by car and ship, because on the one hand you can enjoy the beauties of the coastal landscapes with their fjords deeply cut into the land, on the other hand you have the opportunity to get into the interior of the country with the motor vehicle from the bays and fjords, where there is ample opportunity for hiking, mountain climbing and hunting.Footnote64

The combination of different technologies – steamer and automobile – opened up the Norwegian nature with all its beauty, sublimity, and diversity.

In Auslands-Tourenbuch from 1931, Norway was yet far inferior to other destinations. The statistics on ADAC travel information of the same year presented the same picture.Footnote65 Norway was still hardly discovered as a car travel destination. The pieces were gradually put in place: Roads were built and opened to car traffic.Footnote66 The grand narrative of the land of the manifold vistas, great roads, and skilled drivers was established. More and more Germans could afford a car, even though the development ‘from luxury goods to everyday objects’ had not yet been completed.Footnote67 Last but not least, getting used to the speed of the automobile – originally perceived as too fast for the variety of Norwegian landscapes – was just a matter of time.

Spying out the north

German tourism to Norway continued to take place primarily on board on a ship – after 1934 cheaper options began to be offered by the Nazi leisure organization Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy).Footnote68 In the same year, ADAC and other smaller German automobile clubs were consolidated into a common, Nazi loyal club, DDAC (Der Deutsche Automobil-Club). The club excluded Jewish members and worked for the automobile’s contribution to strengthen the Volksgemeinschaft, and cooperated closely with NSKK (Nationalsozialistische Kraftfahrkorps – The National Socialist Motor Corps), the paramilitary organization for motorists.Footnote69 ADAC-Motorwelt was replaced by the magazine Deutsche Kraftfahrt – published monthly 1939–1943 and four times in 1944 – paying homage to automobile technology at the front.

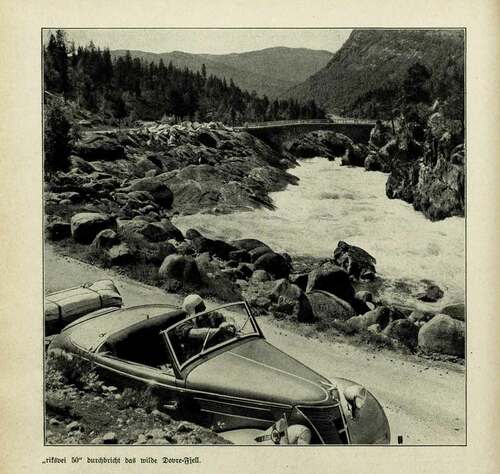

In April 1940, Deutsche Kraftfahrt devoted a five-page long article about the new Norwegian road Riksvei 50, connecting Oslo and Hammerfest and today called E6.Footnote70 The report was published the same month as Germany attacked and occupied Norway. At first glance, the article did not tell a story of war, but a story of tourism. Several well-composed photographs showed a Ford Cabrio, the driver, and a female co-driver. The couple travelled individually, not on board a Nordland cruise. Again, and again, the Ford stopped, and landscape vistas were documented with the camera (). The aim of the tour was to reach the North Cape.

Figure 3. ‘“Riksvei 50” breaks through the wild Dovrefjell’. Photograph from Vitalis Pantenburg, ‘Riksvei 50. Die neue transskandinavische Fernautostraße’. Deutsche Kraftfahrt no. 4 (1940)© Reprinted with the kind permission of ADAC e.V., Communication and Editorial Department. Provided by www.zwischengas.com/archiv.

The story told is about exploring a foreign country by car. On its way through Norwegian landscapes, the car was equipped with a pennant of DDAC at the front and Danish and Norwegian flags on the radiator bonnet. All pictures focused on infrastructure: the road Riksvei 50, the harbours of Oslo, Hammerfest, and Narvik, and the walking path up to the North Cape were all included. The author started describing the length of the Norwegian coast, and the distance from Trondheim to Kirkenes of 2000 km, before noting ‘the almost colonial Nordland’.Footnote71 Today, considering the date of publication, this trip appears as a manifestation of Nazi claims in the North.

The Deutsche Kraftfahrt article from 1940 about experiencing Norway by car was highly political. The text was written and the pictures were taken before the German occupation of Norway, and despite the description of an ‘almost colonial’ space, the author discussed the ‘English interest in Norway’ and noticed that he had met several ‘English “Tourists” and scientists’ on his trip.Footnote72 His quotation marks told the readers that these Englishmen had come to Norway for reasons other than holiday or research. The author was Vitalis Pantenburg (1901–?), a Nazi geographer and journalist who was, in fact, himself accused of being a German spy.Footnote73 Most likely, the purpose of the trip described in the 1940-article was to explore and document Norway for the German military; especially the infrastructure and harbour facilities. This representation of German car tourism in Norway, we can assume, depicts an act of espionage.Footnote74

The female co-driver was not mentioned in the text. Probably, she was Pantenburg’s wife.Footnote75 Her role is unclear – was she an accomplice or a cover, or maybe both? Nevertheless, we never do see her at the wheel, at a time when there were indeed female drivers, even though they were in the minority.Footnote76 In German narratives, Norwegian roads were made for male drivers.

On 9 April 1940, thousands of German soldiers followed the car tracks of Pantenburg and his co-driver, and occupied Norway until May 1945. While there were around 130,000 German soldiers in Norway in 1940, around 380,000 were stationed in the country from 1943 until the end of the war.Footnote77 Wartime service abroad could also involve touristic experiences while stationed in a foreign country, several studies have shown.Footnote78 We may assume that this observation also applies to German soldiers in Norway during World War II. Compared to other locations, being stationed in Norway turned out to be relatively quiet, as the main task was to be prepared for a possible allied attack.Footnote79 As photographs, diaries, landscape paintings, and oral histories document, there was time for skiing, mountaineering, bathing, and sightseeing.Footnote80 Ebba D. Drolshagen, author of several books on the history of German-Norwegian relations, argued that for many of the German soldiers in Norway, Norwegen was an admired touristic destination they would not have experienced without ‘Travel agency Wehrmacht’.Footnote81

The war put a halt on civil tourism, but it did not stop the circulation of narratives and visualizations of the various, sublime, and beautiful Norwegian landscapes.Footnote82 The Norwegian Travel Agency in Berlin and writers in German newspapers and magazines continued to promote Norway as tourist destination.Footnote83 Two publications issued during the occupation can serve as examples for the continuity – and development – of a German ‘tourist gaze’ during World War II.

The first example is Das Land der Mitternachtssonne: Erinnerungen an Norwegen 1940 (The Land of the Midnight Sun: Memories of Norway 1940), written by Hans Poll, a German stationed in Norway.Footnote84 The text was committed to Nazi ideology and assumed a we-community of shared memories of ‘a proud, wonderful time’.Footnote85 The visualization of these war memories, however, happened through photographs of varied, classic tourist sites and landscapes. The texts consisted of different building blocks that we recognize from the pre-war travel guides, describing the manifold landscapes of fjords, mountains, waterfalls, and midnight sun.Footnote86 The photographs in Poll’s book stem from two renowned Norwegian picture agencies, Carl Normann and A.B. Wilse.Footnote87 Both had been important agents in selling Norwegian landscapes as attractive tourist destination by the means of postcards, tourist books, and slide shows.Footnote88 The 72 pictures included in Poll’s book presented the diversity and beauty of Norway seen as a whole. Hiking, skiing, and boat trips were ways to experience Norwegian nature, as was driving a car. Several pictures showed a landscape opened by a road, sometimes with a car.Footnote89

The other example is from Deutsche Kraftfahrt, the previously mentioned magazine issued by the consolidated DDAC. In January 1942, a nine-page long article entitled ‘Norwegen’ was published.Footnote90 The main text is the memory of a pre-war coast, but the introduction puts this travelogue in the context of occupation:

As on all fronts of this war, the NSKK has also proven its worth high up in the north, in the Norwegian mountains, which are so rich in terrain difficulties. The demands that men and machines had to meet here were sometimes unusually high, but they were mastered everywhere.Footnote91

Photographs of NSKK vehicles stuck in mud and snow visualized the story of Norway as a challenging, yet heroic driving experience. Photographs of scenic landscapes were also shown. The text and images present a compelling story: Windscreen Norway, here, was a land of beauty, sublimity, diversity, and heroic, masculine struggle on wheels.

The automobile was to connect Berlin with the northernmost point of the ‘Greater Germanic Reich’, the North Cape. At a time when highway construction in Germany was being pushed forward on a massive scale, the individual practice of driving and car travel might appear as a collective service.Footnote92 Car enthusiasm was part of Nazi propaganda, and the Volkswagen was seen as contributing to literal, but also political mobilization.Footnote93 By this understanding, driving on Norwegian roads, like massive road construction in the occupied country, was part of ‘Hitler’s Northern Utopia’.Footnote94 A scenic ‘Great Road of the North’ was primarily planned for postwar civilian use.Footnote95 Travelling northwards was no longer conceptualized as a border-crossing, but as an appropriation of landscapes claimed to belong to Berlin.

Don’t mention the war

When the war ended in 1945, approximately 1–2 million Germans, perhaps more, had spent time in Norway.Footnote96 They returned to postwar Germany with different memories of Norway,Footnote97 and it is likely that the narratives of wartime in Norway influenced the postwar history of tourism. It may well be that former German soldiers in Norway went back northwards as tourists, with wives and children; that postwar adolescents travelled to the land that fathers, uncles, older brothers or others had talked about; or that they had seen on postcards and read about in books such as Land der Mitternachtssonne.

Historian Alon Confino has described how veterans’ travels to war sites of their youth functioned ‘as a symbolic practice in which German men embraced experience of the Third Reich without being – in the new Western Europe – politically incorrect’.Footnote98 At the same time, a younger generation of travellers began to see tourism as a break with the Nazi past and as a means of international understanding.Footnote99 The heterogeneity of postwar tourists – different generations, roles in Nazi Germany, political standpoints, ways of dealing with the past – makes an analysis of tourist narratives complex. Norwegian roads could encompass a breadth of longings, and this, as we shall see, was most likely key to their attractiveness.

ADAC re-emerged in 1946, and started again to publish ADAC-Motorwelt in 1948, now under the pronounced purpose of democracy, reconstruction, peace, and freedom.Footnote100 The resurrection of ADAC involved efforts to re-establish the Nordic connection, also with the ‘“promised land” in the north’,Footnote101 as one ADAC-Motorwelt writer phrased it. In 1952, the Olympic Winter Games were hosted in the capital city of this promised land, Oslo. This year, Norway was explicitly mentioned in ADAC-Motorwelt for the first time after the war. ADAC published an answer to a ‘letter-to-the-editor’ where a club member asked for a travel route for a summer vacation to Oslo with a Volkswagen. ADAC-Motorwelt indicated how difficult it was for Germans to get a visa to Norway, with the comment: ‘Deutsche noch unerwünscht!’ (‘Germans still unwanted!’) – probably an unconscious adoption of the sign ‘Jews unwanted’, which was found in German shops, restaurants, hotels, and at village boundaries in Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, ADAC-Motorwelt recommended different routes from Hamburg to Oslo.Footnote102

Only a year later, ADAC-Motorwelt published a travel story entitled Eismeerstraße und Mitternachtssonne (Arctic Sea Road and Midnight Sun).Footnote103 This was the year when my great-uncle and his wife made the earlier mentioned road trip northwards with the laundry van. The text in ADAC-Motorwelt was about driving, the different and tough road conditions, the stops along the way, and the many ferries through Norway. The marks of the war in Northern Norway were briefly recognized by the author, although not connected with feelings of sorrow, guilt or worry about how Scandinavians would react to German tourists eight years after the war.Footnote104 No meetings with Norwegians were mentioned, while the author described the Finns as a welcoming people, with good knowledge of the German language.Footnote105 In Finland, he also met several Sami. This was not, however, considered a meeting of equals: ‘The primitive living Lapps are small, have all crooked legs and decorate their blue costumes with a lot of red embroidery’.Footnote106 The author continued the old discourse, now addressed to car tourists. In this way, the car became a vessel not only for space but also time travel: It brought the traveller back to the pre-war concept of Northern remoteness and otherness.

Car travels to Scandinavia gradually became easier and more affordable, at least as far as the Federal Republic of Germany was concerned. From 1954 onwards, Norway no longer required visas for German travellers.Footnote107 The rapid growth of West German industry – usually labelled Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) – helped tourism flourish, with Italy as the main travel destination.Footnote108 In 1955, the one millionth Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the production line in Wolfsburg.Footnote109 During these years the level of motorization in the West German population rose by 20% annually, and in 1960 the number of cars per 1000 inhabitants exceeded the Western European average with 81 cars.Footnote110 In 1961, the same year that the construction of the Berlin Wall finally excluded citizens of the German Democratic Republic from the Scandinavian adventure, the ferry-line between Kiel and Oslo was reopened. The new M/S Kronprins Harald had place for 130 automobiles, and a second ferry, M/S Prinsesse Ragnhild, was introduced in 1966.Footnote111 ADAC-Motorwelt stated that a road trip to the far north no longer had the ‘character of a medium sized expedition’.Footnote112

During the 1950s and 1960s, ADAC-Motorwelt promoted Norway as an attractive car travel destination, often as a part of a Scandinavian journey.Footnote113 In this coverage the landscapes appeared remarkably empty of people and history. Scandinavia was described as a ‘travel destination with wide areas in which time seems to have stood still for centuries’.Footnote114 Landscapes, however, are never empty; they are always historical and closely linked to stories about the past.Footnote115 Supposedly untouched nature can be ‘a landscape of a shared knowledge of history’, said the anthropologist Kirsten Hastrup in regard to Iceland.Footnote116 With this notion in mind, Norwegian landscapes were also German historical landscapes: They were associated with ideas of Vikings and Ultima Thule, and with the names of Ibsen, Grieg, Hamsun, and Nansen. For German tourists, Norwegian landscapes were related to German conceptions of history.

After 1945, these landscapes had a new layer of history: the history of war, occupation, and destruction. There were narratives related to places and placenames (for example the Battles of Narvik and the sinking of Blücher in the Oslo fjord), as well as ruins, voids, and remains of military infrastructure and installations. The Atlantic wall – the German built defence system at the coast – remained as a concrete mark of the war. Places like Narvik and Voss were rebuilt after the war, and the new houses told the story of what had been lost. However, the postwar German guidebooks and ADAC publications hardly describe these urban and coastal landscapes of war.Footnote117 Baedeker from 1957 briefly noted the destructions of Narvik: ‘damage that has since been repaired’.Footnote118 The bunkers along the coast were not mentioned anywhere, neither the Blücher wreck nor the German bombs that ruined Voss. These are some of many examples of what I term ‘silenced historical landscapes’.Footnote119

Landscapes of war were silenced in postwar travel literature, and so was the fact that there were continuities between Nazi tourism and postwar tourism. The social spread of tourism and consumerism brought about by the Nazi leisure organization Kraft durch Freude had great significance for German tourism in the postwar period.Footnote120 The car had played a major role in propaganda but not been common property during Nazi Germany: In the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1950s, the car was regarded as a means of transport free of ideology.Footnote121 Private and individual car travels could appear as a new beginning after the war.

Questions of a German responsibility were apparently not compatible with tourism. In contrast, grief was very well reconciled with tourism, as historian Wiebke Kolbe argued in her study on journeys with the German War Graves Commission.Footnote122 Also ADAC recommended its members to visit the war graves.Footnote123 Nonetheless, travelling meant first and foremost to flee from everyday life.

Car travellers could not flee from being German, however. The car identification revealed the nationality. In this way, car travellers abroad could be understood as ambassadors for the new German states.Footnote124 Both ADAC and Baedeker gave clear instructions how to behave as German tourist abroad. In Schlagbaum hoch! (Turnpike up!), ADAC was primarily concerned about the unsuitable clothing style of German tourists.Footnote125 Baedeker’s guide to Scandinavia from 1957, on the other hand, addressed the war wounds directly:

Anyone who goes abroad should always remember that they are seen as a representative of their people when they appear and behave. Especially in the Scandinavian countries, from which Denmark and Norway were occupied by German troops in World War II, tact and calm restraint are required in order to gain respect and friendship.Footnote126

This did not always work out. In 1965 an ADAC-Motorwelt author shared the story about a German tourist staying at a hotel in Hammerfest, boasting of his wartime experience in the same town.Footnote127 The author was deeply ashamed, and advised his readers never to talk about war memories abroad.Footnote128 Possibly this episode is a sign of the postwar Germany’s generational conflict entangled with Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past).Footnote129

Contrary to US travels to the national parks, German car travel to Norway did not mean getting to know one’s own nation. The idea of national identity was nevertheless woven into the tourist narratives. They were part of a complicated web of images of self and other, ideas of Nordland and Skandinavien, and postwar concepts of guilt and reparation, remembrance and repression, continuity and new beginnings. The war and postwar generations both found their fortunes northwards, albeit with different starting points. For the older generation, the trip could be a return to places visited – or longed for – in their youth; for the younger generation the trip was a break with the past. The roads and routes were the same for both of them.

Grand Tours on wheels

While ADAC guided members to certain places for longer stays in countries such as Italy and Austria,Footnote130 Norway was presented as ‘drive-through’, as previously mentioned. Long driving in the ‘far north’ suited the car’s appeal of individuality. The Volkswagen beetle was the icon of the Western German reconstruction and the new living standard, and travels by car abroad became a modern Grand Tour. Just as the sons of the English nobility went on an educational trip mainly to Italy in the eighteenth century,Footnote131 Germans became automobile mile crunchers in the 1950s and 1960s. The individual travel thus became a collective experience – at least for Germans having the time, the money, a car, and a driver’s licence – and the North Cape became a personal trophy.

Car travel became a fashionable business. Camping places, motels and rest places popped up in Norway in the postwar years.Footnote132 When Baedeker came with its first postwar book about Scandinavia in 1957, it was called Autoreiseführer (Car travel guide).Footnote133 The guide’s selling point – also when ADAC-Motorwelt promoted it – was that ‘the road plays a particularly important role in Scandinavia’.Footnote134

ADAC started to offer several package tours for car travellers.Footnote135 In 1960, members could choose between 12 different Nordlandreisen car travels to Scandinavia, and all of the six Norwegian travels led to the south and west coast and to the ‘most beautiful fjords’.Footnote136 ADAC also organized convoy travels, as the ‘Wikingerfahrt’ through Norway and to the North Cape with 200 participants in 1969.Footnote137

Only mile-crunching could give an idea of the three main attractions of Scandinavia: solitude, largeness, and diversity.Footnote138 The Nordic countries, and Norway in particular, were conceptualized as a sequence of contrasting vistas, connected by roads and guidebooks. This was similar in the very beginning of Norwegian tourism history, as described earlier. What was new was that the car was no longer incompatible with the fjord landscape and the car’s pace was no longer considered to be too fast for the diversity of Norway. Rather, the automobile became the preferred means to experience the country. Even when it came to an article about sport fishing in Norway, ADAC did not describe this as a purpose in itself, but as a valuable occasion to stop on the route through Norway.Footnote139

To get to know Norway, you needed a car, a tent, a camera, and time.Footnote140 A recommended trip could easily be up to 8000 kilometres: ‘Can be mastered in five weeks without difficulty’.Footnote141 ADAC knew that Norwegian road kilometres were not the same as German road kilometres. The numerous ferries made an interesting change, but also delayed the journey.Footnote142 The road conditions – generally unpaved, narrow, winding, and unsecured roads – made driving challenging.Footnote143 ADAC-Motorwelt gave the impression that Norway’s ‘boldly laid roads’ were just for good drivers with strong nerves, thus offering the starting point for proud travel reports.Footnote144

Although gender was not explicitly mentioned in the postwar accounts, an old narrative of men conquering nature was continued here. Breath-taking roads, huge distances, and the solitude made the postwar Grand Tour a demonstration of masculinity. The authors of all writings analysed in this article were male, but their travelogues hardly allow any conclusions about who they travelled with. Generally, ‘we’ or ‘one’ is the subject, but we do not know whether it is (male) comrades, couples, or families. The picture in an article likely shows the author’s daughter, and in a few places, such as the discussion of ferry prices and hostels, there are references for families.Footnote145 However, the mileage was hardly compatible with family holidays.

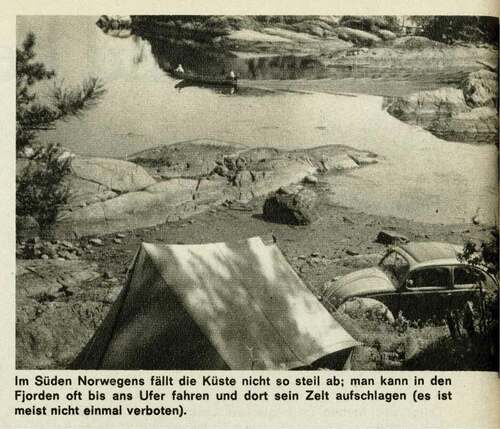

Conquering and enjoying nature was to be closely connected for the modern car traveller. Scandinavia was presented as different from central Europe, and the main tourist destination, Italy.Footnote146 ‘Northwards’ was always construed as the opposite of the South and standstill, always a goal in motion. While you were lying on the beach with many others in Italy, you were crunching miles in the vastness of the north. In Northern Europe, there was ‘a lot of space’, many opportunities to be alone and to feel close to nature.Footnote147 Here was ‘Europe’s last big nature paradise’.Footnote148 This modern sanctuary was only available by car. Camping was promoted as a way to get closer to nature and solitude (). ADAC-Motorwelt discussed camping equipment, places, and behaviour, and in 1962, an independent camping guide to the Nordic countries was launched.Footnote149

Figure 4. ‘In the south of Norway the coast does not descend so steeply; in the fjords you can often drive right to the shore and pitch your tent there (it is usually not even forbidden)’. Photograph from Heinz Schmidt-Wiking, ‘Nach Norden, ums Südland kennenzulernen’. Motorwelt no. 6 (1964)© Reprinted with the kind permission of ADAC e.V., Communication and Editorial Department. Provided by www.zwischengas.com/archiv.

By the 1960s, car travelling to Norway had become an attractive yet still paradoxical combination of collective and individual experience. On the one hand, to be guided by the ADAC, Baedeker, and others meant driving collective ‘German’ tourist routes in Norway. On the other hand, driving a private car on individually chosen routes, made the car traveller feel unique. This was contrary to the masses of German Italy-tourists, and it was different from the package tourism that attracted many others.Footnote150 The car seemed to fit perfectly with the diversity of the Norwegian landscapes, the fjords, and the individual experience of the Northern remoteness. The windscreen mediated a more authentic, more natural Norway than tourists had ever experienced before.

These German narratives demonstrated considerable similarities to American driving culture. The US national parks were opened up to the masses by the automobile, as David Louter elucidated in Windshield Wilderness.Footnote151 Apart from Alaska’s reserves, the parks have not been imaginable without cars – ‘parks have been spaces, both real and imagined, for machines in nature’.Footnote152 Just as Americans sought and found ‘wilderness’ by car, German drove northwards in search of it. While for American motorists the national parks have represented ‘natural’ sanctuaries within a modern world, for German motorists Scandinavia became such a ‘world within the world’. A place in which time seems to have ‘stood still’, as quoted earlier. In America car tourism also led to the modern wilderness movement and the search for roadless nature,Footnote153 but this was not the case in German-Norwegian tourism. In the German narratives, the roads appeared as a matter of course and were never questioned. The ‘natural world’ was extensive stretches of space, without a soul, experienced only by the mile-crunching machine.

Conclusion

The development of Norway as a destination for German car tourism did not only depend on roads and accommodation, cars and driving skills, travel documents and holiday time. There was also a need for images, texts, and told stories that portrayed precisely this type of travel as possible, exceptional, and attractive. In this development, the authors of travel guides and information channels played a significant role, as did the German automobile club ADAC.

The German narrative of travelling northwards by car emerged and gained power in the period between the 1920s and the 1960s, so that car tourism finally was presented to be the best, even ‘natural’ way to discover Norway. This narrative was entangled with concepts of nature, technology, gender, and national identity, and strongly influenced by social, economic, and political history – especially the German occupation of Norway 1940–1945. ‘Northwards’ was described as the opposite of the South and standstill, and thereby combined with different concepts such as the interwar condemnation of ‘the monotonousness of everyday life’, Nazi ideology of ‘Nordic’ supremacy, and the postwar idea of Scandinavia with a ‘lot of space’ and ‘nature’ in contrast to the destination of Italy.

When the car became a part of the tourist experience in Europe and America in the beginning of the twentieth century, Norway was renowned in Germany for the fjords, the North Cape, and the cruises in the stern waves of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II; a type of collective travel that was expanded after 1934 by the Nazi organization Kraft durch Freude. The car did not fit into these landscapes of the promised Nordland. Until the 1950s, concrete travel recommendations to Norway did not appear in the ADAC club magazine ADAC-Motorwelt, and no car travel guide to Scandinavia was brought onto the German market.

Several instances did prepare an ‘automobile gaze’ at Norway, however. First, all of the analysed publications from before 1930 described travelling through Norway as the main attraction. Norway was not one landscape, but many contrasting vistas; not one resort to travel to, but a long route. Secondly, positive descriptions of travelling by cariole made clear that individual travels helped to experience ‘authentic Norway’. Choosing the route, stops, and pace individually intensified the experience of Norwegian nature. In the beginning of the 1930s, a third instance was added, when guidebooks and ADAC became interested in Norwegian road construction. Mastering the road and the technique of travelling in remote nature became a sublime experience and part of Norway’s attractiveness. The German occupation of Norway 1940–1945 spread these narratives among Germans as never before, and linked them to stories of heroism, conquest, and technology. The roads northwards were now conceptualized as part and prerequisite of a ‘Great Germanic Empire’, linking the North Cape to Berlin.

In the 1950s, when West Germany was experiencing the onset of mass tourism and mass motorization, the concept of the extraordinary car trip on Norway’s roads was ready to be widely communicated and put into praxis. It appealed to both Germans of the war generation who may have retained older concepts of landscape and the North, and veterans who wanted to see again the places of their youth. But it also appealed to the postwar generation who wanted to set themselves apart from the older generation and look to a future of international understanding, in which tourists were ambassadors of a new Germany. Even if Volkswagen and car travel were deeply connected to Nazi propaganda, driving northwards could appear as a new beginning after the war. Historical landscapes of war were ‘silenced’ in the postwar narratives on being a tourist on Norwegian roads.

Destination Norway became part of a modern Grand Tour through Scandinavia. Just mile-crunching could give an idea of the solitude, largeness, and diversity of Scandinavia, and Norway in particular. The fjords were no longer the obstacles, but the goal for the car tourist. Roads and campsites replaced waterways and cruise ships as a preferred gateway to experience Norway. As the parks for American motorists, Norway for German motorists became a destination where automobiles and landscapes entered into an almost ‘natural’ symbiosis. ADAC embraced the opportunity to lead its members northwards, both by promoting the destination and by offering organized trips.

By the mid-1960s, Norway had been established as a superb car travellers’ destination. The following decades must be the subject of future research considering major social, political, and technological changes. The first impression given by studying tourist publications of these decades (amongst them all ADAC-Motorwelt issues) is that the concept of Norway-by-car has been remarkably stable, even if cruising along the coast with the Norwegian public coastal route Hurtigruten was given new attention, and different Norwegian regions and activities like hiking and cross-country skiing were introduced. The tenor of promoting the country as a touristic destination seemed nevertheless to still require a car in order to experience the ‘authentic Norway’.Footnote154 The German car travellers and RV drivers one meets on Norwegian roads today are thus following a traditional route. When most of them feel they are not being ‘a typical tourist’,Footnote155 this is a symptom of a well-established and widely promoted ‘Norway-package’ where individual driving far away from package tourism is a key attraction.

For my great-uncle and his wife in 1953, the van borrowed from the in-laws’ laundry opened up a new world. Where they got the idea for the travel from, what information they read, and how they found their route is not known – nor whether they were ADAC members. What remains are the fragmentary pictures of a trip that, precisely in its individuality and experience en route, reflected collective German ideas of Norway as tourist destination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marie-Theres Fojuth

Marie-Theres Fojuth is Associate Professor of History at University of Stavanger. Her research focuses on environmental history, public history, and the history of knowledge and technology. Fojuth’s doctoral thesis from the Humboldt University Berlin explores Norwegian railway politics in the nineteenth century as a history of geographical knowledge. Her current project concentrates on Western Norway as an automobile fjordscape.

Notes

1. Innovasjon Norge, Nøkkeltall, 23, 37.

2. Kampevold Larsen, “Turistvegene.”

3. Urry, The Tourist Gaze. See also Zuelow, History of Modern Tourism, 76–90.

4. Urry, The Tourist Gaze, 1.

5. On Norwegian automobility, see Eriksen, Et land; Nygaard, Store drømmer; Østby, “Car mobility”; Skåden, “Bilder”. On the history of tourism, see Berg and Gjermundsen, Da Norge ble oppdaget; Büchten, “Auf nach Norden!”; Kinzler and Tillmann, eds. Nordlandreise; Rogan, “Meninger og myter”; Slagstad, (Sporten), 13–130.

6. Berg and Gjermundsen, Da Norge ble oppdaget; Spode, “Nordlandfahrten,” 20.

7. For a brief introduction to German car tourists to Norway, see Kliem, “Mit dem Wohnmobil”; Wöbse, “Anders Reisen.”

8. On the role of mass media, see Elliot, Mediating Nature.

9. Featherstone, Thrift and Urry, eds. Automobilities; Flink, The Automobile Age; Mom, Atlantic Automobilism; Möser, Geschichte des Autos.

10. Fojuth, “Høyfjells-koreografier”; Hvattum, Brenna, Elvebakk, and Kampevold Larsen, eds. Routes, Roads and Landscapes; Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey; Zeller, Driving Germany.

11. Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey; Larsen, “Tourism Mobilities”; Mauch and Zeller, eds., The World Beyond the Windshield.

12. Bradley, British Columbia; Louter, Windshield Wilderness; Mauch and Zeller, eds. The World Beyond the Windshield; Sutter, Driven Wild.

13. On national identities and driving, see Edensor, “Automobility.”

14. ADAC, “Der ADAC im Überblick.”

15. “Die Abteilung Touristik,” 342; ‘Unser “Millionär”,’ 24.

16. G., “Die Abteilung Touristik,” 342–343.

17. On ADAC more generally, see Bretz, 50 Jahre ADAC; Ramstetter, 100 Jahre ADAC.

18. On German magazines for motorists, see Kubisch, Das Automobil als Lesestoff.

19. Pagenstecher, Der bundesdeutsche Tourismus, 460. Literary quotations have been translated by me, M.-T. F.

20. “Ferien im hohen Norden.”

21. “Nordlandfahrt 1929 des ADAC [1].”

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Kinzler and Tillmann, eds. Nordlandreise.

26. Henningsen, Klein, Müssener, and Söderlind, eds. Wahlverwandtschaft; Zernack, “Anschauungen vom Norden.”

27. Brennecke, “Recken als Erzieher?”

28. See for example Cag., “ADAC-Auslandstourenfahrt 1928.”

29. Louter, Windshield Wilderness; Sutter, Driven Wild.

30. On the joy of driving far, see Wetterauer, Lust an der Distanz, 201–213.

31. Höpfner, “Bilder von der ADAC-Amerikafahrt.”

32. Mom, Atlantic Automobilism, 59–132.

33. See photograph entitled “ADAC-members in front of the snow peaks of Bjorli”, B., “Die ADAC Nordlandfahrt 1929 [1],” 5.

34. “Nordlandfahrt 1929 des ADAC [2],” 5; see also the photograph ibid., 4.

35. B., “Die ADAC Nordlandfahrt 1929 [2],” 9.

36. Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey, 52–69.

37. See note 35 above. 12.

38. Ibid.

39. Edelmann, Vom Luxusgut.

40. “Automobilstatistik Europas.”

41. “Nachrichten aus aller Welt.”

42. Müller, Die Welt des Baedeker.

43. Baedeker, Schweden, Norwegen.

44. Ibid., XXV.

45. Ibid., XXII.

46. Ibid., XXV.

47. Ibid., XXV.

48. Ibid., XXV.

49. Ibid., XXIV.

50. Ibid., XIII, see also XXIV.

51. For example in Ruge and Arstal, Norwegen, 68.

52. Baedeker, Schweden, Norwegen, XVIII; see also Nielsen, Norwegen, 169.

53. Ruge and Arstal, Norwegen, 65.

54. Nielsen, Norwegen; Baedeker, Schweden, Norwegen; Grieben, Norwegen.

55. Fojuth, Herrschaft über Land und Schnee, 317.

56. Ruge and Arstal, Norwegen, 62; see also Baedeker, Schweden, Norwegen, XXII, XXV; Grieben, Norwegen, 31.

57. Ibid., 89.

58. Baedeker, Norwegen, Dänemark, XXVIII.

59. Ibid., XXI.

60. Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry.

61. Nye, American Technological Sublime; Fojuth, “Høyfjells-koreografier,” 180–182.

62. Baedeker, Schweden, Norwegen, XXIX–XXX.

63. ADAC, Auslands-Tourenbuch, 155.

64. Ibid.

65. “Ein Jahr ADAC-Arbeit,” 26, 27.

66. Nygaard, Store drømmer.

67. See note 39 above.

68. Baranowski, Strength through Joy; Schallenberg, “Kreuzfahrt unterm Hakenkreuz”; Timpe, Nazi-Organized Recreation.

69. Hochstetter, Motorisierung und “Volksgemeinschaft,” 191–229.

70. Pantenburg, “Riksvei 50.”

71. Ibid., 35.

72. Ibid., 38.

73. Stratigakos, Hitler’s Northern Utopia, 38.

74. In 1941, Pantenburg published a seven-part series about the travel in the newspaper Kölnische Zeitung. Ibid., 37–38.

75. Ibid., 37.

76. Fell, Kalkuliertes Abenteuer, 44–75; Scharff, Taking the Wheel.

77. Bohn, “Die Wehrmacht”; Drolshagen, Den vennlige fienden, 16.

78. Buchanan, ‘“I felt like a Tourist”’; Confino, “Traveling,” 108–109; Gordon, War Tourism; Kolbe, “Trauer und Tourismus”, 84; Manning, Die Italiengeneration, 111–113; Torrie, ““Our rear area”.”

79. Drolshagen, ‘“Reisebüro Wehrmacht”,’ 208; see also Økland, Norwegen, 17–20.

80. Drolshagen, ‘“Reisebüro Wehrmacht”,’ 208–211; Dyrhaug and Sørlie, Tyske foto, 43, 52, 62, 65, 69, 74, 97, 101, 102, 105.

81. Drolshagen, ‘“Reisebüro Wehrmacht”,’ 208–211.

82. Stratigakos, Hitler’s Northern Utopia, 11–35; Økland, Norwegen.

83. Stratigakos, Hitler’s Northern Utopia, 45–46.

84. Poll, Das Land der Mitternachtssonne.

85. Ibid., [3].

86. Ibid., [3], 24.

87. Ibid., [2].

88. Bjorli, ed. Wilse.

89. Poll, Das Land der Mitternachtssonne, 29, 33, 34, 38, 39, 44, 45, 52, 54, 60.

90. “Norwegen” (Deutsche Kraftfahrt).

91. Ibid., 27.

92. Möser, Geschichte des Autos, 180–182; Vahrenkamp, “Automobile Tourism”; Zeller, Driving Germany.

93. Möser, Die Geschichte des Autos, 174–180.

94. Stratigakos, Hitler’s Northern Utopia, 37–62.

95. Ibid., 46–55. See also Andersen, Hitlers byggherrer, 78–91.

96. Drolshagen, ‘“Reisebüro Wehrmacht”,’ 208.

97. Ibid., 215.

98. Confino, “Traveling”, 107–112, quote 110.

99. Ibid., 111–112; Jobs, “Youth Mobility.”

100. Sporer, “Wieder ein Schritt vorwärts!”

101. F., “Dänemark,” 12.

102. “Hier spricht der Reiseonkel,” 21.

103. Sartorius, “Eisemeerstraße.” This year, the first German postwar guide to Norway was published, a translation from French. Spode, “Nordlandfahrten,” 31.

104. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 222, mentioned also the marks of the war.

105. Sartorius, “Eisemeerstraße,” 398.

106. Ibid.

107. Bienwald, “Ein Bummel,” 498.

108. Manning, Die Italiengeneration.

109. Bundesarchiv, “Neue Deutsche Wochenschau.”

110. Edelmann, Vom Luxusgut, 228; Möser, Geschichte des Autos, 193.

111. Erlenbusch, ‘“Fährhaus nach Norden”’; Stampehl, “Die Kiel-Oslo-Fähre.”

112. See note 20 above.

113. Ba. “Camping”; Bienwald, “Ein Bummel”; Boustedt, “Im Lande Peer Gynts”; Paul, “Viel Platz”; Schmidt-Wiking, “Nach Norden”; Schulz, “Zum Sportfischen.”

114. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 220.

115. Assmann, Das kulturelle Gedächtnis, 50–56; Fojuth, Herrschaft über Land und Schnee, 322–325.

116. Hastrup, “Icelandic Topography,” 58.

117. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 222; Sartorius, “Eismeerstraße”, 399; Schmidt-Wiking, “Nach Norden,” 118.

118. Baedekers Autoreiseführer (1957), 268.

119. Based on the concept of ‘silence’ in cultural memory studies, see Dessingué and Winter, eds. Beyond Memory.

120. Baranowski, Strength through Joy, 231–249.

121. Möser, Geschichte des Autos, 174, 191–198.

122. Kolbe, “Trauer und Tourismus.”

123. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 222; Walter, “Besucht die Kriegsgräber.”

124. Manning, Die Italiengeneration, 110–132.

125. Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobilclub e.V. München, Schlagbaum hoch! 48.

126. Baedekers Autoreiseführer (1957), 58. Also found in Baedekers Autoreiseführer (1976), 62.

127. Bernhard, “Wir im Ausland,” 69.

128. Ibid.

129. See the discussion in Confino, “Traveling,” 97–101.

130. S., “Zauberhafte Riviera”; Zitke, “Kennen Sie den Wallersee?”

131. Zuelow, History of Modern Tourism, 14–30.

132. Østby, “Car mobility.”

133. Baedekers Autoreiseführer (1957).

134. “Die Bücherecke”; Baedekers Autoreiseführer (1957), 2.

135. “Hier spricht die ADAC-Reise (1959),” 407–408.

136. “Hier spricht die ADAC-Reise (1960),” 284.

137. “ADAC-Winter-Campingtreffen 1969/70,” 119.

138. See for example Paul, “Viel Platz.”

139. Schulz, “Zum Sportfischen.”

140. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 220.

141. Ibid., 222.

142. Bienwald, “Ein Bummel,” 499; Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 220, 222; Boustedt, “Im Lande Peer Gynts,” 364; Paul, “Viel Platz,” 121.

143. Bienwald, “Ein Bummel,” 499; Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 221; Boustedt, “Im Lande Peer Gynts,” 364; Schmidt-Wiking, “Nach Norden,” 116.

144. Sartorius, “Eismeerstraße,” 399; see also Schmidt-Wiking, “Nach Norden,” especially 116.

145. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 220; Paul, “Viel Platz,” 121; Sartorius, “Eisemeerstraße,” 399.

146. Schmidt-Wiking, “Nach Norden,” 114.

147. Paul, “Viel Platz,” 120.

148. Biere, “Mit Auto und Zelt,” 222. See also the expression ‘mother nature”, Paul, “Viel Platz,” 120.

149. ‘Zwei “Zeltplatz-Forscher”’; Lange, Campingurlaub.

150. Manning, Die Italiengeneration; Kopper, “Die Reise als Ware.”

151. Louter, Windshield Wilderness.

152. Ibid., 164.

153. Sutter, Driven Wild.

154. Nowak, ADAC Norwegen.

155. Prebensen, Larsen, and Abelsen, “I’m Not a Typical Tourist.”

Original sources

- ADAC. Auslands-Tourenbuch und Auslands-Reiseführer 1931. Berlin: Verlag Dr. Hüsing, 1931.

- ADAC. “Der ADAC im Überblick.” ADAC. Accessed November 22, 2020. https://www.adac.de/der-adac/verein/daten-fakten/ueberblick/ .

- “ADAC-Winter-Campingtreffen 1969/70.” ADAC-Motorwelt [22], no. 10 (1969): 118–119.

- Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobilclub e.V. München. Schlagbaum hoch! ADAC-Ratgeber für Auslandsreisen. 2nd edition. Munich: Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobilclub e.V., 1954.

- “Automobilstatistik Europas.” Der Motorfahrer no. 12 (1919): 8.

- B., K. “Die ADAC Nordlandfahrt 1929 [1].” ADAC-Motorwelt 26, no. 26 (1929): 3–5.

- B., K. “Die ADAC Nordlandfahrt 1929 [2].” ADAC-Motorwelt 26, no. 28 (1929): 9–12.

- Ba. “Camping von der Costa Brava bis zum Nordkap.” ADAC-Motorwelt 8, no. 6 (1955): 414–415.

- Baedeker, Karl. Schweden, Norwegen: Die Reiserouten durch Dänemark. Nebst Island und Spitzbergen. Handbuch für Reisende. 13th edition. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1914.

- Baedeker, Karl. Norwegen, Dänemark, Island, Spitzbergen: Handbuch für Reisende. 14th edition. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1931.

- Baedekers Autoreiseführer Skandinavien mit Finnland. Stuttgart: Baedekers Autoführer-Verlag, 1957.

- Baedekers Autoreiseführer Skandinavien mit Finnland. 8th edition. Stuttgart: Baedekers Autoführer-Verlag, 1976.

- Bernhard, Michael. “Wir im Ausland.” ADAC-Motorwelt [18], no. 7 (1965): 69–71.

- Bienwald, Gerhard. “Ein Bummel durch Schweden und Norwegen.” ADAC-Motorwelt 8, no. 7 (1955): 498–499.

- Biere, H. “Mit Auto und Zelt zum Polarkreis.” ADAC-Motorwelt 14, no. 4 (1961): 220–222.

- Boustedt, Olaf. “Im Lande Peer Gynts.” ADAC-Motorwelt 11, no. 7 (1958): 364–365.

- Bretz, Hans. 50 Jahre ADAC: Im Dienste der Kraftfahrt. Munich: Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club e.V., 1953.

- Bundesarchiv. “Neue Deutsche Wochenschau 289/1955.” August 12, 1955. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.filmothek.bundesarchiv.de/video/586185?topic=doc6lldywtgun788z6tl97&start=00%3A05%3A01.09&end=00%3A06%3A57.10.

- Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. 1756. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Cag. “ADAC-Auslandstourenfahrt 1928 vom 11. bis 23. April.” ADAC-Motorwelt 25, no. 9 (1928): 5–8.

- “Die Bücherecke.” ADAC-Motorwelt 10, no. 7 (1957): 383.

- Dyrhaug, Tore and Rune Sørlie. Tyske foto fra Norge. Oslo: Dreyer, 1990.

- “Ein Jahr ADAC-Arbeit.” ADAC-Motorwelt 28, no. 3 (1931): 4–50.

- F., K. “Dänemark – Das nordische Autoland.” ADAC-Motorwelt 2, no. 8 (1949): 12–13.

- “Ferien im hohen Norden.” ADAC-Motorwelt 16, no. 2 (1963): 111.

- G., A. “Die Abteilung Touristik.” ADAC-Motorwelt 10, no. 7 (1957): 342–343.

- Grieben: Norwegen. Grieben Reiseführer Band 46. Berlin: Grieben-Verlag, 1930.

- “Hier spricht der Reiseonkel.” ADAC-Motorwelt 5, no. 1 (1952): 21–22.

- “Hier spricht die ADAC-Reise.” ADAC-Motorwelt 12, no. 7 (1959): 406–407.

- “Hier spricht die ADAC-Reise.” ADAC-Motorwelt 13, no. 5 (1960): 278–280, 283–284.

- Höpfner, Wilhelm. “Bilder von der ADAC-Amerikafahrt.” ADAC-Motorwelt 25, no. 48 (1928): 15.

- Innovasjon Norge. “Nøkkeltall for norsk turisme 2019.” Innovasjon Norge. Accessed November 22, 2020. https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/N_kkeltall_for_norsk_turisme_2019_ce8a8138-7765-43f8-81ef-5fe51142f594.pdf.

- Lange, Werner. Campingurlaub im Norden: Die schönsten Campingreisen nach Dänemark, Schweden, Norwegen, Finland. Munich: Gräfe und Unzer Verlag, 1962.

- “Nachrichten aus aller Welt.” ADAC-Motorwelt 30, no. 17 (1933): 26–30.

- Nielsen, Yngvar. Norwegen, Schweden und Dänemark. Meyers Reisebücher. 8th edition. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut, 1903.

- “Nordlandfahrt 1929 des ADAC [1].” ADAC-Motorwelt 26, no. 4 (1929): 3.

- “Nordlandfahrt 1929 des ADAC [2].” ADAC-Motorwelt 26, no. 10 (1929): 4–5.

- “Norwegen.” Deutsche Kraftfahrt no. 1 (1942): 26–34.

- Nowak, Christian. ADAC Norwegen. Reiseführer plus. Munich: Gräfe und Unzer Verlag GmbH, 2019.

- Pantenburg, Vitalis. “Riksvei 50: Die neue transskandinavische Fernautostraße.” Deutsche Kraftfahrt no. 4 (1940): 35–39.

- Paul, Hermann. “Viel Platz in Europas Norden: Länder mit hellen Sommernächten.” ADAC-Motorwelt 16, no. 2 (1963): 120–121.

- Poll, Hans. Das Land der Mitternachtssonne: Erinnerungen an Norwegen 1940. Oslo: Verl. Haraldssøn, 1940.

- Ruge, Sophus, and Aksel Arstal. Norwegen. Monographien zur Erdkunde 3. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1926.

- S., H. “Zauberhafte Riviera di Fiori.” ADAC-Motorwelt 11, no. 4 (1958): 164–165.

- Sartorius, Carl. “Eismeerstraße und Mitternachtssonne.” ADAC-Motorwelt 6, no. 7 (1953): 398–399.

- Schmidt-Wiking, Heinz. “Nach Norden, ums Südland kennenzulernen.” ADAC-Motorwelt [17], no. 6 (1964): 114–119.

- Schulz, Werner. “Zum Sportfischen nach Norwegen.” ADAC-Motorwelt 10, no. 6 (1957): 296.

- Sporer, Ludwig. “Wieder ein Schritt vorwärts!” ADAC-Motorwelt 1, no. 1–2 (1948): 1.

- “Unser ‘Millionär’.” ADAC-Motorwelt [18], no. 11 (1965): 24.

- Walter, Bruno. “Besucht die Kriegsgräber.” ADAC-Motorwelt [17], no. 4 (1964): 208.

- Zitke, H.J. “Kennen Sie den Wallersee?” ADAC-Motorwelt [17], no. 7 (1964): 62–64.

- “Zwei ‘Zeltplatz-Forscher’ des ADAC berichten aus Skandinavien.” ADAC-Motorwelt [18], no. 3 (1965): 38–40, 43.

Bibliography

- Andersen, Ketil Gjølme. Hitlers byggherrer: Fritz Todt og Albert Speer i Norge. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 2021.

- Assmann, Jan. Das kulturelle Gedächtnis: Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Munich: C.H. Beck, 1992.

- Baranowski, Shelley. Strength through Joy: Consumerism and Mass Tourism in the Third Reich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Berg, Arngeir, and Arne Johan Gjermundsen. Da Norge ble oppdaget: europeernes utrolige opplevelser og inntrykk i det mangslungne fjellandet Norge på 1700- og 1800-tallet. [Oslo:] J.W. Cappelens Forlag A.S., [1992].

- Bjorli, Trond, ed. Wilse: mitt Norge. Oslo: Forlaget Press, 2015.

- Bohn, Robert. “Die Wehrmacht als Besatzungsarmee.” In Hundert Jahre deutsch-norwegische Begegnungen: Nicht nur Lachs und Würstchen, edited by Bernd Henningsen, 189–191. Berlin: Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2005.

- Bradley, Ben. British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017.

- Brennecke, Detlef. “Recken als Erzieher? Amundsen, Hedin und Nansen – Drei Idole in Deutschland.” In Wahlverwandtschaft: Skandinavien und Deutschland 1800 bis 1914, edited by Bernd Henningsen, Janine Klein, Helmut Müssener, and Solfrid Söderlind, 419–420. Berlin: Jovis, 1997.

- Buchanan, Andrew. “‘I Felt like a Tourist Instead of a Soldier’: The Occupying Gaze – War and Tourism in Italy, 1943–1945.” American Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2016): 593–615. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2016.0055.

- Büchten, Daniela. “Auf nach Norden! Deutsche Touristen in Skandinavien.” In Wahlverwandtschaft: Skandinavien und Deutschland 1800 bis 1914, edited by Bernd Henningsen, Janine Klein, Helmut Müssener, and Solfrid Söderlind, 113–114. Berlin: Jovis, 1997.

- Confino, Alon. “Traveling as a Culture of Remembrance: Traces of National Socialism in West Germany, 1945–1960.” History & Memory 12, no. 2 (2001): 92–121.

- Dessingué, Alexandre and Jay Winter, eds. Beyond Memory: Silence and the Aesthetics of Remembrance. Routledge Approaches to History 13. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Drolshagen, Ebba D. Den vennlige fienden: Wehrmacht-soldater i det okkuperte Norge. Oslo: Spartacus, 2012.

- Drolshagen, Ebba D. “‘Reisebüro Wehrmacht’: Deutsche in Norwegen zwischen 1940 und 1945.” In Nordlandreise: Die Geschichte einer touristischen Entdeckung. Historien om oppdagelsen av turistmålet Norge, edited by Sonja Kinzler and Doris Tillmann, 208–215. Hamburg: Mare, 2010.

- Edelmann, Heidrun. Vom Luxusgut zum Gebrauchsgegenstand. Die Geschichte der Verbreitung von Personenkraftwagen in Deutschland. Frankfurt am Main: Verband der Automobilindustrie e.V. (VDA), 1989.

- Edensor, Tim. “Automobility and National Identity: Representation, Geography and Driving Practice.” In Automobilities. Theory, Culture & Society 21, 4/5 (2004), edited by Mike Featherstone, Nigel Thrift, and John Urry, 101–120. London: Sage, 2005.

- Elliot, Nils Lindahl. Mediating Nature. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Eriksen, Ulrik. Et land på fire hjul: hvordan bilen erobret Norge. Oslo: Res Publica, 2020.

- Erlenbusch, Timo. “‘Fährhaus nach Norden’: Neubeginn des Linienverkehrs von Kiel nach Skandinavien nach 1945.” In Nordlandreise: Die Geschichte einer touristischen Entdeckung. Historien om oppdagelsen av turistmålet Norge, edited by Sonja Kinzler and Doris Tillmann, 216–223. Hamburg: Mare, 2010.

- Featherstone, Mike, Nigel Thrift, and John Urry, eds. Automobilities. Theory, Culture & Society 21, 4–5. London: Sage, 2005.

- Fell, Karolina Dorothea. Kalkuliertes Abenteuer: Reiseberichte deutschsprachiger Frauen (1920–1945). Ergebnisse der Frauenforschung no. 49. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1998.

- Flink, James J. The Automobile Age. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1988.

- Fojuth, Marie-Theres. Herrschaft über Land und Schnee: Norwegische Eisenbahngeographien 1845–1909. Geschichte der technischen Kultur no. 7. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2019.

- Fojuth, Marie-Theres. “Høyfjells-koreografier: norske og sveitsiske jernbanelinjeguider omkring 1900.” In Turismhistoria i Norden, Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi No. 150, edited by Wiebke Kolbe, 173–186. Uppsala: Kungliga Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur, 2018.

- Gordon, Bertram M. War Tourism: Second World War France from Defeat and Occupation to the Creation of Heritage. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

- Hastrup, Kirsten. “Icelandic Topography and the Sense of Identity.” In Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe. Edited by Michael Jones and Kenneth R. Olwig, 53–76. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

- Henningsen, Bernd, Janine Klein, Helmut Müssener, and Solfrid Söderlind, eds. Wahlverwandtschaft: Skandinavien und Deutschland 1800 bis 1914. Berlin: Jovis, 1997.

- Hochstetter, Dorothee. Motorisierung und “Volksgemeinschaft”: Das Nationalsozialistische Kraftfahrkorps (NSKK) 1931–1945. Studien zur Zeitgeschichte no. 68. Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2005.

- Hvattum, Mari, Brita Brenna, Beate Elvebakk, and Janike Kampevold Larsen, eds. Routes, Roads and Landscapes. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011.

- Jobs, Richard Ivan. “Youth Mobility and the Making of Europe, 1945–60.” In Transnational Histories of Youth in the Twenntieth Century, edited by Richard Ivan Jobs and David M. Pomfret, 144–166. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Kampevold Larsen, Janike. “Turistvegene som landskapshage.” In Utsikter: Norge sett fra veien 1733–2020, edited by Nina Frang Høyum and Janike Kampevold Larsen, 168–175. Oslo: Press, 2012.

- Kinzler, Sonja, and Doris Tillmann, eds. Nordlandreise: Die Geschichte einer touristischen Entdeckung. Historien om oppdagelsen av turistmålet Norge. Hamburg: mare, 2010.

- Kliem, Thomas. “Mit dem Wohnmobil zum Nordkap.” In Hundert Jahre deutsch-norwegische Begegnungen: Nicht nur Lachs und Würstchen, edited by Bernd Henningsen, 233–235. Berlin: Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2005.

- Kolbe, Wiebke. “Trauer und Tourismus: Reisen des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge 1950–2010.” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History no. 14 (2017): 68–92.

- Kopper, Christopher. “Die Reise als Ware: Die Bedeutung der Pauschalreise für den westdeutschen Massentourismus nach 1945.” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History no. 4 (2007), 61–83.

- Kubisch, Ulrich. Das Automobil als Lesestoff: Zur Geschichte der deutschen Motorpresse 1898–1998. Berlin: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, 1998.

- Larsen, Jonas. “Tourism Mobilities and the Travel Glance: Experiences of Being on the Move.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism no. 2, 1 (2001): 80–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/150222501317244010.

- Louter, David. Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington’s National Parks. Foreword by William Cronon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

- Manning, Till. Die Italiengeneration: Stilbildung durch Massentourismus in den 1950er und 1960er Jahren. Göttinger Studien zur Generationsforschung no. 5. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2011.

- Mauch, Chritstof, and Thomas Zeller, eds. The World Beyond the Windshield: Roads and Landscapes in the United States and Europe. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2008.

- Mom, Gijs. Atlantic Automobilism: Emergence and Persistence of the Car, 1895–1940. Explorations in Mobility No. 1. New York: Berghahn Books, 2015.

- Möser, Kurt. Geschichte des Autos. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2002.

- Müller, Susanne. Die Welt des Baedeker: Eine Medienkulturgeschichte des Reiseführers 1830–1945. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2012.

- Nye, David E. American Technological Sublime. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1994.

- Nygaard, Pål. Store drømmer og harde realiteter: veibygging og biltrafikk i Norge, 1912–1960. Oslo: Pax Forlag, 2014.

- Økland, Einar. Norwegen, schönes Land! Tyskprodusert fredspropaganda i krigens Norge, 1940–1945. Oslo: Samlaget, 2017.

- Østby, Per. “Car Mobility and Camping Tourism in Norway, 1950–1970.” Journal of Tourism History 5, no. 3 (2013): 287–304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2014.938777.