ABSTRACT

In the early twentieth century, intense public debate was taking place in Sweden around the control of alcohol consumption. Under intense pressure from the growing temperance movement, the Swedish government passed a motion to hold a referendum on 27 August 1922 to determine whether a total prohibition of alcohol should be implemented. One of the most important means of influencing public opinions was the propaganda poster, which relied on simple pictures, catchy slogans and bright colours to domesticate the prohibition debate and make it easily digestible. This paper conducts a study of the posters produced by the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns during the lead-up to the referendum. It finds that, despite their opposing arguments, both sides used similar arguments based around the breakdown of family life and the breakdown of Swedish society, depicting an imagined present or future in which Sweden was lawless and traditional values were threatened. Furthermore, both sides stirred up class warfare, creating conflict between the Swedish people and the government, and depicting alcoholism as a predominantly male, working-class problem. Overall, it argues that the ‘no’ campaign posters were ultimately more successful because of their ability to play on voters’ emotions rather than use rational arguments.

Introduction

In the early twentieth century, intense public debate was taking place in Sweden around the control of alcohol consumption. Although alcohol had been strictly regulated since the 1860s, many politicians and religious figures felt that this was not enough to curb the country’s problems with alcohol abuse.Footnote1 Under intense pressure from the growing temperance movement, the Swedish government passed a motion to hold a referendum – the first in the country’s history – on 27 August 1922 to determine whether a total prohibition of alcohol should be implemented. Both sides of the debate launched elaborate referendum campaigns to convince the public of their arguments. One of the most important means of influencing public opinions was the propaganda poster, which relied on simple pictures, catchy slogans and bright colours to domesticate the prohibition debate and make it easily digestible for people.

This paper aims to establish the importance of propaganda posters in the 1922 prohibition referendum in Sweden by conducting an analysis of a small body of posters produced by the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns in the eight months leading up to the referendum. Specifically, it seeks to identify the recurring themes across posters and how they were enacted through linguistic and semiotic resources to convince the Swedish public to vote for or against prohibition. Given their visual and verbal content, the posters are approached through the theoretical framework of social semiotics and analysed with the tools of multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA), which is a method to reveal how semiotic resources are used to shape the representation of discourses and how we understand the world.Footnote2

While many studies have been carried out on the use of propaganda posters,Footnote3 particularly in the context of China,Footnote4 the Soviet Union,Footnote5 and the First and Second World Wars,Footnote6 there are many areas of research that still remain undeveloped. This is particularly the case with Sweden, whereby limited research has been conducted to date and has focused predominantly on election campaign posters between 1911 and 2010.Footnote7 Despite the importance of the 1922 referendum, there is limited literature on the topic, with no work yet to focus specifically on the linguistic and semiotic resources in the posters used during the campaign.Footnote8 Thus, this study breaks new ground in its attempt to shed light on the 1922 referendum through a social semiotic approach to the referendum posters and how they could be used to sell and advertise ideas around prohibition as if it were a consumer product. By using MCDA, it offers a focus on the ways in which complex messages and ideologies, at times paradoxical, are embedded in compositional and semiotic choices – an area which has generally been neglected in studies of posters by social historians or political scientists. Furthermore, it adds an important historical perspective to studies of propaganda in the field of media and communication studies, which overwhelmingly explore contemporary texts and artefacts.Footnote9 Finally, it opens up room for discussions on how propaganda posters can serve as an important battleground for different versions of history, thereby encouraging new debates on the social history of alcohol in Sweden.

The 1922 prohibition referendum: a brief history and overview

The Swedish sobriety movement has its roots in the early nineteenth century, but it began to grow as a political force at the beginning of the twentieth century in line with increasing national debates around alcohol consumption. Supported by the Free Church, as well as the labour and women’s suffrage movements, the Swedish sobriety movement began to move towards a more hard-line approach, campaigning to push through a general ban on intoxicants in the country.Footnote10 To strengthen this campaign, the different sobriety organizations that made up the movement gathered every three years for Prohibition Congresses. In 1909, they conducted an unofficial plebiscite to gauge public support on prohibition. The vote was telling: 55.6% of the Swedish population over the age of eighteen (both men and women) voted in favour of forbidding alcohol, which obliged the government to place the issue squarely on their political agenda.Footnote11

Given the radicality of sobriety and the political profiling of the movement, it was no surprise that the country’s two radical parties – the Liberals and the Social Democrats – particularly supported the issue of prohibition. In fact, at the 1911 Prohibition Congress, the Social Democratic Party decided to introduce demands for a ban on alcohol in their party program. When the Liberal Party came into government following the 1911 general election, Prime Minister Karl Staaff established a Sobriety Committee, made up of eight prohibitionists and three opponents to prohibition, to investigate the possibility of restricting sales of alcohol or imposing a total ban.Footnote12 One member of the committee was a young Stockholm doctor called Ivan Bratt. Unlike many of the other committee members, Bratt wanted to avoid prohibition because he felt that it would not be enforceable. Instead, he proposed individual restrictions on the purchase of alcohol and for private profit interest to be disconnected from alcoholic beverages.Footnote13 In 1914, Bratt developed the Stockholm system to demonstrate how his idea would work, introducing an individual restriction system with counter books and a limit of 12 litres/quarter from 26 February 1914 in order to regulate private purchases of alcohol.Footnote14

The Committee issued a report proposing a local veto and a new sales ordinance, which was actively debated in the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament). In the parliamentary sessions of 1914, 1915 and 1916, the lower chamber approved both proposals (perhaps unsurprisingly, given that two thirds of its members were members of a temperance movementFootnote15). However, the upper chamber consistently rejected them, citing economic and employment concerns. As both chambers needed to be in agreement for legislation to pass, the idea was halted. Nonetheless, under increasing pressure and facing an economic crisis, the Riksdag finally passed a nationwide alcohol bill in 1917, excluding prohibition but approving Bratt’s sales ordinance. It entered into force across the country on 1 January 1919.

However, the Sobriety Committee was still not satisfied and on 5 August 1920, they released a report that included a legislative proposal for general prohibition of all alcoholic beverages containing more than 2.25% alcohol. The Committee agreed that prohibition should not be implemented without a majority of the Swedish population being in agreement. Therefore, they proposed a nationwide advisory referendum.Footnote16 Ivan Bratt was reluctant to support the proposal, arguing that it went against ‘liberal Swedish traditions of justice’.Footnote17 Despite his concerns, in 1921, the Riksdag passed a motion for a consultative referendum on whether to completely ban the production, possession, introduction and transfer of beverages with more than 2.25% alcohol. It would require a majority of two thirds to enter into law. Prohibition was now threatening to splinter the main Swedish political parties. A referendum was, thus, a way to diffuse these tensions by placing the issue directly before the Swedish public.Footnote18

The referendum was set for 27 August 1922. A major topic of debate leading up to this date was whether ballots should be marked so as to distinguish the age, gender and social group of voters. While many members of the Sobriety Committee were against this proposal, Bratt felt that it was a good idea to mark ballots by gender. He argued that, based on evidence from neighbouring countries Norway and Finland (where prohibition was in place), women were more likely to vote for a ban than men. Furthermore, only 5% of Swedish women had a counter book.Footnote19 It would, therefore, indicate ‘qualified incomprehension’ to impose prohibition if most men were against it. After much debate, the Riksdag voted in favour of gender marking. Each ballot paper would, therefore, be stamped with an M (man) or K (kvinna – woman) to distinguish voters.Footnote20 The government believed that if it could get as many men to vote as possible, this would enable them to finally put the prohibition issue to rest and continue with the Bratt system, while also avoiding a split in the main Swedish political parties.

It was agreed that no political parties would campaign in the referendum; rather, it would be run by independent organizations. The ‘yes’ campaign organized its activities through various well-established sobriety and temperance societies split into blocs. These included the Förbudsvännernas rikskommitté (Prohibition Friends’ National Committee), Svenska nykterhetssällskapets representanter församling (Swedish Sobriety Society’s Parish Representatives), Riksutskottet för de kristnas förbudsrörelse (National Committee for the Christian Prohibition Movement) and Centralrådet för kvinnornas förbudsarbete (Central Council for Women’s Prohibition Work).Footnote21 The ‘no’ campaign, on the other hand, was led by the Landsföreningen för folknykterhet utan förbud (National Association for Sobriety without Prohibition), which was established by pharmacology professor Carl Gustaf Santesson and vice chairman director Allan Cederborg. This organization was mainly represented and financed by brewery, distillery and bottle making industries, receiving just over half a million SEK in funding.Footnote22

Over the course of eight months, the two campaigns battled it out, exploiting a wide range of media and artefacts to convince the Swedish public of their cause. Messages were spread through pamphlets, placards, songs and flyers, as well as cartoons, postcards, photographs, films and posters. These material artefacts were also accompanied by propagandistic events and displays, including public lectures, parades, marches, rallies, demonstrations and church sermons.Footnote23 Of all these visual artefacts and bold displays, posters stood out as a particularly effective propaganda device. Posters intensified the propaganda campaign already at play in traditional print media by capitalizing upon the growing dominance of images and the global circulation of information and tapping into the collective consciousness of the Swedish public.Footnote24 The ‘yes’ posters were produced predominantly by the Förbudsvännernas rikskommitté, while the majority of the ‘no’ posters were created by the Propagandacentralen N.E.J. in Gothenburg (financed largely by the city’s brewing industries).Footnote25 Both sides recruited famous artists to design their posters: Birger Ohlsson, Ivar Starkenberg and Karl Örbo for the ‘yes’ campaign and Fred Proessdorf, Gunnar Widholm and Albert Engstrom for the ‘no’ campaign.

Through a combination of pictures, colours, and slogans with understood referents and allusions, posters translated complex and abstract ideas into simple and concrete forms, which made them easily digestible for the public, even if these ideas often relied on exaggerated, stereotyped or distorted information. Furthermore, the frequently humorous nature of these posters meant that ideological meanings could be hidden behind the argument that they were ‘just a bit of fun’,Footnote26 therefore granting them with a more subtle persuasive power than the overt tactics of newspaper articles, manifestos, meetings and marches.

In what follows, a selection of posters produced by the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns will be analysed with the aim of identifying how both language and semiotics were co-deployed to convince Swedish people to vote a particular way in the prohibition referendum. Studying such posters is essential in gaining an understanding of how propaganda can influence public opinion and how strategies of persuasion are designed for specific audiences and purposes.Footnote27

Research design

Given the nascent state of visual culture research in Swedish historical studies, it is important to reassess the way in which multimodal artefacts, such as posters, played a pivotal role in transmitting propaganda, particularly during the 1922 referendum on the prohibition of alcohol – the first referendum ever to be held in Sweden. This paper identifies the key themes that reoccur across posters produced for the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns and uses four examples that are characteristic of these themes to examine how different linguistic and semiotic resources were used to convince the Swedish public to vote for or against prohibition. The posters come from a broader dataset of 36 posters collected from two archives: Arkiv Gävleborg (https://www.arkivgavleborg.se/), which contains Sweden’s largest collection of political posters, and Kungliga Biblioteket (www.kb.se), the Swedish National Library.

The collected posters are explored using MCDA – a qualitative approach that derives from social semiotics and brings together two important methodologies from the field of sociolinguistics: multimodality and critical discourse analysis. Multimodality is concerned with how different semiotic resources (e.g. language, image, typography, colour, texture, materiality, layout, composition) are co-deployed to make meaning, while CDA seeks to demonstrate how certain practices, ideas, values and identities are promoted, naturalized and transmitted through discourse.Footnote28 Discourse is a central concept in MCDA, which can be defined as a set of socially constructed beliefs and forms of knowledge that influence how we think and act in particular situations. MCDA seeks to demonstrate how representations of discourse are shaped by the co-deployment of lexical and semiotic resources and to draw out what ideas are foregrounded, abstracted or concealed with the aim of identifying their ideological and/or political consequences.Footnote29 When applied to the context of posters produced for the 1922 referendum, MCDA can help deconstruct the verbal and visual choices used to convey ideas about the prohibition of alcohol and how they work to shape public understanding of the topic and make certain beliefs seem credible and rational.

My approach to MCDA draws particularly on the work of Ledin and Machin,Footnote30 who designed a set of analytical tools to critically interrogate multimodal texts and how certain semiotic choices shape what we do, how we think, and how we experience the world. These tools focus particularly on the following key elements:

language (e.g. vocabulary, grammar, use of metaphor and rhetoric);

image (e.g. people, actions, perspectives, angles, distance);

colour, particularly the emotions, attitudes, and values associated with certain choices;

typography, especially the cultural connotations of certain typefaces;

texture and materiality in terms of their physical and symbolic meanings (e.g. liquidity, viscosity, temperature, relief, density, rigidity)

layout and composition in terms of salience, framing, coordination, and hierarchies.

In the first stage of MCDA, the collected advertisements were grouped into themes based on recurring patterns in their use of language and semiotics. The themes were established based on the core message of the posters rather than their central image; this decision was guided by the fact that the same image often reoccurred across posters (on each side of the campaign, but also within the same campaign) for different communicative purposes. This led to the identification of two overarching themes used by both the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns: the breakdown of family life and the breakdown of Swedish society. They will be discussed further in the first analysis section of the paper.

In the second stage, each poster was subjected to a detailed MCDA. Due to space limitations, four examples will be presented in this paper (representative of each theme for the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns). The arguments made regarding their use of linguistic and semiotic cues and how they are used to build support for or against prohibition are reflective of the general strategies used across all posters. However, applying MCDA to individual examples can help uncover subtleties in messages and also reveal contradictions in their design.

Key themes of the prohibition referendum campaign posters

Applying MCDA to the dataset of 36 posters produced by the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns for the 1922 referendum, I have identified two overarching themes that reflect their principal communicative functions – the breakdown of family life and the breakdown of Swedish society – as well as a series of sub-themes centred around specific crimes, Swedish values and sociocultural traditions. These themes/sub-themes are summarized in , along with the typical imagery, slogans and colours that appear across the posters. The table serves as a useful classification system for those exploring the propaganda poster genre in both historical and contemporary contexts and helps clearly identify recurring semiotic features and their significance in constructing particular arguments.

Table 1. The themes and semiotic features of 1922 prohibition referendum campaign posters.

Although the arguments differ considerably on both sides of the campaign (as to be expected), each uses their posters to evoke an imagined present or future, emphasizing the disastrous consequences that voting for or against prohibition will have for individuals, their families and the nation. While limited historical research has been conducted on referendum campaign posters, in recent years, there has been a growing number of studies on the topic in a contemporary context. Research on posters produced for the 2016 European Union referendum campaign in the UK,Footnote31 as well as referendums in Ireland on the Good Friday Agreement (1998), Lisbon Treaty (2008), marriage equality (2015), and abortion (2018)Footnote32 all show similar tactics to the Swedish 1922 referendum posters, highlighting the imagined impact of a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ vote on both a personal and national level. Equally, like the Swedish historical posters, the ‘no’ campaigns tend to resort to more scaremongering tactics to rouse the public’s anxieties, while the ‘yes’ campaigns rely largely on rationalism and appeals to the public’s sensibilities. Similar strategies can also be identified in historical postcard propaganda circulated during the early twentieth-century campaigns for Home Rule in Ireland and women’s suffrage in the UK,Footnote33 as well as more generally for expressing support for or against Bolshevism, Naziism and Fascism.Footnote34

In what follows, a general overview is presented of the ways in which MCDA can help identify how language, image, colour, typography, texture, layout and composition are co-deployed across the body of collected posters. To further develop an understanding of how language and semiotics work together in the posters to promote support for or against prohibition, each section is followed by a detailed MCDA of four individual posters – two ‘yes’ and two ‘no’ examples – that are representative of the major themes identified. Shining a spotlight on individual examples can help identify foregrounded, abstracted or concealed ideas, their potential contractions and broader ideological/political aims. The posters were selected as, in accordance with Rosch’sFootnote35 prototype theory, they are most prototypical in terms of their central features (identified in ). This analysis will enable me to put forward arguments in the concluding discussion on the similarities between both campaigns despite their opposing stances and why the ‘no’ campaign was marginally more successful than the ‘yes’ campaign.

The breakdown of family life: the “Yes” campaign

The theme of family breakdown was used on both sides of the campaign and is defined by its emphasis on the impact that voting for or against prohibition would have on traditional family life in Sweden.

In posters for the ‘yes’ campaign, arguments focus on an imagined present in order to make a case for why alcohol should be banned. Images frequently show domestic scenes, but their sanctity is threatened by the father who is depicted lying drunk on the floor or on the steps of the house with an empty bottle in his hand. The mother and children are hiding in the corner with a scared look on their faces and tears in their eyes. Other similar images show the father in a drunken state of rage, raising his fist to his wife and children as they flinch and cover their heads. These images not only promote the idea that thousands of families in Sweden currently suffer from domestic abuse and poverty, but also suggest that if the Swedish public does not vote for prohibition, they will be directly contributing to their continued suffering. Thus, they call on people to protect their fellow citizens by voting yes to prohibition. These posters also make strong use of the dichotomy between black and white and its symbolic connotations of good versus evil. In them, the drunk and aggressive father is typically shaded in darker hues to emphasize his malevolence, while the mother and children are shaded in lighter tones to depict them as innocent and pure.Footnote36 This reframes the referendum not just as a choice between banning or not banning alcohol, but also as a battle between good and evil as played out through the family.

These points are further emphasized by the accompanying slogans that describe alcohol as ‘humanity’s enemy’ and the ‘destroyer of homes’ and call directly on mothers to ‘think of your children’ and ‘choose the right path’ for the sake of their future. This direct address to mothers was a strategic move by the ‘yes’ campaign as, just one year earlier, all women over the age of 23 had been granted universal suffrage. As women had limited experience of voting, temperance societies saw them as a malleable group from which they could potentially win thousands of votes.Footnote37 Although the ‘no’ campaign targeted women in some of their posters, this was not a central concern. In fact, they worried that newly emancipated women presented a danger to the future of Sweden because they were incapable of making an informed decision.Footnote38 Therefore, the few posters to feature women encourage them to listen to their husbands and vote no.

In other posters, the father is not present; instead, the mother is shown lying in bed, clutching her children close to her and gently stroking their hair. The tenderness of the scenes is emphasized by the use of pastel colours, as well as accompanying captions that suggest the mothers are directly addressing their children (‘I’ll vote yes for your sake’, ‘I’ll protect our home’). Not only is this bedtime scene familiar to Swedish women across the country, thus enabling them to feel an immediate connection with the content, but the direct form of address allows them to embody the image and imagine themselves in the same position, both physically and metaphorically. This gives the plea to vote yes a humanistic touch and makes readers – particularly women – feel more emotionally invested in its message.

In other more metaphorical depictions of the absent father, the mother and children are shown fleeing from their home. As they look back over their shoulder, they see barrels of alcohol spilling and forming a river that floods their house. The strapline warns that ‘the river of alcohol drowns homes and family happiness’. Here, the ‘river’ is not a typical blue or even the colourless hue of pure alcohol; rather, it is shades of red, yellow and orange, used to symbolize fire and its associations with hell, evil and danger.Footnote39 The combination of the absent father, dramatic strapline and evocative river leads readers to connect the dots themselves, either assuming that alcohol has led to a broken home – something extremely taboo at that time in Sweden – or that the father has drunk himself to death, leaving his family in abject poverty. Often these images also feature longer blocks of text with unqualified statements, informing readers that ‘innumerable homes’ have been ‘destroyed’ because of alcohol and ‘countless tears’ shed, which has put a ‘heavier burden’ on women. Although no evidence is provided to support these points, the emotive language is convincing and encourages women to feel empathy with their fellow peers and vote yes out of solidarity. With the suffrage movement having only concluded the year before, this sense of comradeship was still heightened amongst women and is something that the ‘yes’ campaign knowingly exploited.

“At the crossroads”: a multimodal critical discourse analysis

The poster in , produced by for the ‘yes’ campaign”, shows a crossroads junction on which a signpost points to two forks in the road: the left depicts the imagined outcome of voting for prohibition, while the right shows that of voting against prohibition. Its bright red hue draws upon viewers’ familiarity with stop signs,Footnote40 encouraging them to pause and reflect before making a decision about which path to choose. Furthermore, the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ signs are shaped like pointing hands, which act as manicules that direct viewers’ attention to the words printed on top and signal the possible directions they can take.Footnote41

Figure 1. “At the crossroads”: breakdown of family life (“Yes” campaign).

On the left path is a typical middle-class family: the father, in a boater hat and suit, and the mother, in a blouse and skirt, are linking arms and walking next to their two small children. The four members’ close proximity to one another signals their tightknittedness, while the parents’ raised heads and turned gaze indicates their disgust at and disconnection with the way of life portrayed on the no path.Footnote42 They are heading towards a homely red cottage in the woods – a clear symbol of traditional Swedish rural tranquillity, a safe haven from the world outside.

In contrast, the right path shows two drunk men: one is sitting on the floor, red-faced with his head down and hand on a bottle, while the other is staggering up the road holding a bottle and clutching his stomach. Their downward gazes create distance from viewers, alienating them and their chosen path in life.Footnote43 The absence of women or children on this path clearly indicates that alcoholism will lead to the rupture of families. In the background is a pub, shaded in a dull brown that stands in direct opposition to the vibrant red of the cottage on the other path and associates the scene with the dirt and grime of the inner city. This feeling of foreboding is also accentuated by the other similar-looking buildings alongside, as well as the murky grey of the grass, which varies considerably from the paler green of the grass on the yes path. Thus, through this clever use of images, colour and framing, the referendum is reformulated not just as a choice between banning or not banning alcohol, but as a battle between good and evil, safety and danger, a stable family or a broken home. Despite these overt messages, there are also some subtle ideas being channelled by the poster. Not only does the ‘no’ path only depict men as drunk, but their style of dress (black bowler hat, tieless shirt) suggests that they are working class. Thus, the poster visually implies that alcoholism is a male, working-class problem. In putting forward this belief, it turns Sweden’s battle with drunkenness into a battle of gender and class, pitting different groups against one another and suggesting that to abstain from alcohol grants higher status, wealth and success in life.

Beneath the image in black capital letters are the words ‘AT THE CROSSROADS’, used to indicate the scene in the picture, but also metaphorically to state that the country is at a crucial decision point in its history. This is followed by the date of the referendum (27 Aug) and then ‘VOTE YES!’ in bright capital letters, which creates a sense of urgency and incites the public to vote in favour of prohibition if they wish to protect the sanctity of the family and the best interests of their children.

The breakdown of family life: the “No” campaign

For the ‘no’ campaign, arguments on the breakdown of family life focus more on an imagined future and are predominantly centred around crime, with posters asserting that prohibition will encourage smuggling and illegal distilling. It may also lead Swedes to resort to drastic measures and start consuming mouthwash, perfume, hair tonic or shoe polish as viable alternatives, which would ultimately poison them. While criminal activity may be considered as a repercussion for Swedish society, here, it is very clearly framed in the context of family life instead. Images typically show the patriarch of the family carrying out these illicit acts within the family home. Rather than cower away or disapprove, his wife and children are fully immersed in the act, listening intently as he explains what he is doing and teaches them how to do it too. From these images, the implication is clear: a vote for prohibition is a vote for lawlessness, juvenile delinquency and corruption of the sanctity of home. In early twentieth-century Sweden, a stable home life was deemed as essential for the nation’s wellbeing; home stood for ‘emotions and warmth, for security, harmony, and coziness’.Footnote44 All of these virtues are seemingly under threat should a total ban on alcohol be approved in the referendum. These threats to family life are further emphasized by the typical slogans that accompany such images, which are often sarcastic in nature (‘what nice future prospects!’) and use personal pronouns to show shared accountability (‘must we be forced into crime?’), as well as strong value-laden language (‘should we contribute to the poisoning of our people?’). These emotionally provocative statements imply that prohibition will encourage crime and the disintegration of family life.

Other frequently occurring images in ‘no’ campaign posters are serpents or hydras, also a common feature of early twentieth-century temperance posters.Footnote45 These threatening creatures are often portrayed with an open mouth, forked tongue and red eyes, and are hovering over the family home or a map of Sweden, ready to pounce. Snakes have a long historical association with ‘evil’ because of their depiction in Christianity and Judaism as a representation of the devil.Footnote46 They are also recognized in heraldry as symbols of wisdom and defiance. Thus, here, they are seen to uphold the truth and work to depict a terrifying future that will destabilize families and, by the same token, destabilize Sweden. Their impact is also strengthened by the fact that a series of phrases are often printed on their bodies that describe the imagined future of the country and how prohibition will spark a chain of events that will lead to the breakdown of family life: ‘prohibition – destroyed sanctity of the home – reign of terror – defiance of law – double taxation – unemployment – poverty – misery’. While there is no clear connection between these events, their close proximity to one another connotes logic and presents them as effects of one another.Footnote47

Colour is also drawn upon for rhetorical effect in the ‘no’ campaign’s posters. In the family scenes, blue is the overwhelmingly preferred choice for the background. Blue has a long association with calmness and serenity.Footnote48 By using it in a typical family setting that has been corrupted by smuggling, illegal distilling or poisoning, it implies that these types of activities will become the new norm and will no longer be seen as something outrageous, but rather as a normal part of everyday life in Sweden. In contrast, the posters with the snakes tend to have bright red backgrounds – a colour that acts as a symbolic visualizer of danger ahead, as well as frustration and sacrifice.Footnote49 Red is historically associated with martyrdom and is employed here to suggest that an innocent family have had to sacrifice themselves and forcibly forego their own lives as a result of prohibition.

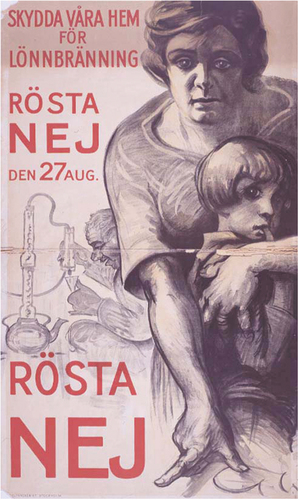

“Protect our home from illegal distilling”: a multimodal critical discourse analysis

shows a poster for the ‘no’ campaign that aims to persuade voters that banning alcohol will pose a major threat to the sanctity of family life. The poster is dominated by a large image of a woman and child. The woman has her left arm protectively around the child who sucks his thumb and cuddles into his mother’s bosom. Both figures are depicted from a full-frontal angle and look directly at the viewer. Kress and van LeeuwenFootnote50 describe this gesture as an act of ‘demand’ because it creates a visual form of direct address by acknowledging viewers explicitly and forcing them to enter into an imaginary relationship with the figures. In this case, their large pleading eyes, stern expressions and tense hands showcase their vulnerability, making an emotional call to help them out of their plight.

Figure 2. “Protect our home from illegal distilling”: breakdown of family life (“No” campaign).

Behind them in the background is the patriarch, engaged in the process of illegally distilling his own alcohol using a funnel, tube and the family teapot. The teapot is a long-established symbol of homeliness and domesticity.Footnote51 Here, by repurposing this everyday household object for an illegal cause, it turns into a dangerous artefact and acquires new meanings tied up with crime and corruption. However, at the same time, by moving the process of distilling into the ‘sanctum sanctorum’ of the home, it also somewhat normalizes it and suggests that it is now every much a part of ordinary family life as drinking a cup of tea.Footnote52 Unlike the woman and child, the man is depicted from a side angle, with his head bowed and fully engrossed in his activity. Kress and van Leeuwen see this as an act of ‘offer’Footnote53 because it ‘offers’ the represented participant to viewers as a piece of information that they must interpret. Here, viewing him in juxtaposition to his wife and child, we feel immediate anger towards him and sympathy towards them. These feelings are intensified by his facial expression and shaded cheeks, which suggest that he is drunk, as well as the disproportionate size difference between the figures,Footnote54 which makes salient the women and child, thereby foregrounding their appeal.

The appeal of the woman and child is also strengthened by the accompanying written text that appears in bright red block capitals – drawing on the colour’s associations with danger – and states ‘PROTECT OUR HOME FROM ILLEGAL DISTILLING. VOTE NO ON 27 AUG. VOTE NO’. Here, the use of the imperative commands voters to act assertively, while the personal pronoun ‘our’ is highly emotive and makes viewers feel guilt-tripped into action. By centring arguments for prohibition around an ‘innocent’ mother and child, it humanizes the campaign: the dangers of prohibition are no longer based on statistics or facts, but rather tied up with individual faces and stories. Viewers, thus, become more emotionally invested in the arguments put forward and may even reflect on their own circumstances or those of the people around them. The impact of the message is also enhanced by the woman’s index finger, outstretched and pointing directly to the final ‘NO’ in large font at the bottom of the poster, as well as the position of the husband ‘trapped’ between the two ‘VOTE NO’ straplines.

Like the ‘yes’ campaign, gender- and class-based messages are also embedded in this poster. At its heart is the clear implication that drinking alcohol and criminal activity are predominantly male activities. However, more subtly, lies the suggestion that prohibition will start ‘corrupting’ good, middle-class homes and risk turning them into working-class homes; this is apparent through the overtly middle-class clothes and hairstyle of the woman and boy contrasted with the dirty and stained labourer’s clothes of the man. Thus, despite their differing arguments, the ‘no’ and ‘yes’ campaigns make similar claims, stirring up gender and class divisions to push forward their beliefs around prohibition.

The breakdown of Swedish society: the “Yes” campaign

The other major theme running across posters for both the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns is the dramatic consequences that banning or not banning alcohol will have on Swedish values and sociocultural traditions, therefore leading to the potential breakdown of Swedish society.

The ‘yes’ campaign stirs up class warfare in its posters, capitalizing on the many tensions existing in Sweden at this time. Prior to the First World War, 1.3 million Swedes had emigrated to the US due to the country’s growing inequality, while there was a general strike in 1909 and hunger riots in Stockholm in 1917.Footnote55 Thus, focusing on class inequalities and how they are exacerbated by alcohol was an emotive way to win sympathy. Posters portray the Riksdag as made up solely of entitled elites who make vast amounts of money at the expense of the Swedish people. To emphasize this point, images show the Swedish people represented as a large muscular man fighting back against the Government, embodied in the figure of a man in a tuxedo and top hat. The images are often accompanied by slogans that act as calls to arms, telling Swedes to ‘break the shackles of alcohol’ or ‘stop the alcohol capital’ by voting in favour of prohibition.

It is this framing of the government as greedy, selfish and capitalistic that dominates many of the other posters for the ‘yes’ campaign. Most posters are heavily text-based and rely on long statements with manicules (☛) pointing to key sentences that outline why the current Bratt System is ineffective. Echoing the image of the Swedish people versus the Government, one central belief asserted is that the Bratt System is contributing to the wealth of the government. Although it is true that the money made from the sale of alcohol went largely back into the government, the money was then reinvested in public services. Furthermore, as the Bratt System introduced alcohol rationing, there was a limit on the amount of money that would be made each year. Here, however, such statements cleverly twist the purpose and outcome of the Bratt System to the ‘yes’ campaign’s advantage, convincing readers that the government is being avaricious. Other critiques of the Bratt System are instead framed around egalitarianism, with claims that it ‘fosters inequalities’, while prohibition is ‘fair for everyone’. Although rationing was intended to encourage equality in alcohol consumption, it, in fact, had the opposite effect, with Systembolaget (the government-owned chain of liquor stores) dictating who had access to a motbok according to their ‘alcohol necessity’. Married women, young, unmarried men, the unemployed and the homeless were all prohibited, for example, while people living in cities and in the south received much larger rations than those in the countryside and in the north.Footnote56 As many voters had first-hand experience of this discrimination, this argument would have resonated strongly with them. Other statements claim that the Bratt System curbs individual freedom because alcohol can only be purchased at certain times of day, which is described in one poster as ‘breaking a record in childishness’. There is a certain irony in complaining about when alcohol can be bought, given that the ‘yes’ campaign’s ultimate aim is prohibition and that they fully supported the Bratt System previously; nonetheless, the strong emphasis on curtailing freedom was likely to gain potential voters’ support for the cause.

In other posters, the government’s expenditure each year on schooling, housing, unemployment and transport is framed in relation to the amount of money that the Swedish public spend on alcohol, with the aim of highlighting how much money they ‘squander’ and that only a total ban on alcohol will stop this. Infographics are frequently used to emphasize this point, with symbols representing each area of expenditure arranged in size according to investment. The biggest symbol of all is often the bottle, used to draw attention to the large sum of money that the public spends on alcohol. By framing this in juxtaposition to government expenditure, the posters imply that there is a direct connection between the two and that how much the Swedish public spend on alcohol is bad. However, once again, this point is contradictory, given that most of this money was reinvested by the government into local services; in fact, there is a case to be made that the more money the public spend, the better it is for Sweden. Nonetheless, for the ‘yes’ campaign, the central argument here is that for Swedish society to function properly, more government investment is needed and that somehow prohibition will enable this. While the logic is unclear, the argument appears positive and convincing for many voters who wish for a better country.

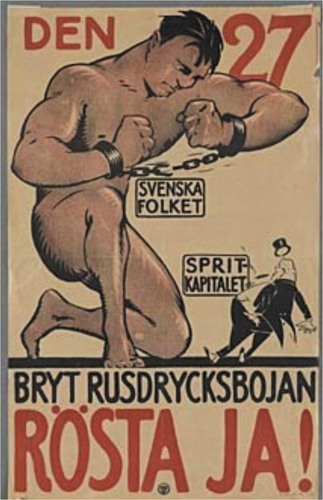

“Break the shackles of alcohol”: a multimodal critical discourse analysis

The poster in represents a characteristic poster of the ‘yes’ campaign centred around the impact that alcohol is currently having on Swedish society. Its central image is a figurative representation of the Swedish people versus the Government, which bears a strong resemblance to images produced by the working-class labour movements across Europe at this time. The poster is dominated by a large, muscular, tanned, naked man with shackles on his wrists. He is half-kneeling on the floor and his bowed head, strained face, clenched fists and tense shoulders indicate that he is trying to break free from the shackles. Shackles have a long history of use, dating back to ancient times, but are particularly associated with the Atlantic slave trade. They were frequently taken up by the temperance movement to suggest that people are ‘slaves’ to alcohol,Footnote57 as clearly indicated in this poster, which implies that the Swedish people are not just ‘slaves’ to alcohol, but also to politicians and the liquor industry as a whole. However, the fact that one link in the chain is broken gives hope that the Swedish people will break their dependency on alcohol by voting in favour of prohibition for the greater good of the nation.

Figure 3. “Break the shackles of alcohol”: breakdown of Swedish society (“Yes” campaign).

The large man in the figure is based on classical revivalist models of body perfection, which had become popular during the Physical Culture Movement (PCM) of the late nineteenth century.Footnote58 While the PCM was associated with right-wing politics in many countries (e.g. Germany, Italy), in Sweden, it was seen as a democratic socialist movement, which reconciled ‘unbridled manliness and disciplined bourgeois civility’ to achieve social harmony.Footnote59 Gymnastics in particular was practiced by the majority of the population in the countryside. These ideas are transmitted through the poster by the label next to the man informing us that he is ‘the Swedish people’. Thus, viewed within this sociocultural context, we understand him as an allegory of the workers, fit, strong, and ready to ‘rise up’ against the cultural elite. The collective strength of the people is accentuated by his large size and dominating position as he towers over the figure below, thereby creating an unequal power relationship between the twoFootnote60 and suggesting that it is only by working together that the Swedish people have the ability to bring about change.

The extent to which arguments around prohibition have been turned into class warfare is further emphasized by the other figure in the poster. Far smaller in stature, this man is noticeably older, paler, overweight and balding. Furthermore, he is dressed in a black tuxedo and top hat and smoking a cigar. Viewed together, his dress and appearance work as symbols of wealth, high social status and corporate success, positioning him as a member of the elite and, therefore, an ‘enemy’ of the Swedish people. His back is turned to viewers, indicating a feeling of indifference, while his outstretched legs and arms, tilted body and raised hat and cigar showcase him as a coward when confronted by the collective force of the workers. The label alongside states that he represents ‘alcohol capital’; as money from alcohol sales went primarily to the Swedish government, we immediately interpret the figure as a politician or, rather, a representation of the entire government, suggesting that they are only interested in making money off the public. The polysemy of the term ‘alcohol capital’ also means that it can be interpreted as the distillers, pub landlords or anybody else involved in the alcohol industry, all personified in the image of the greedy tycoon. Through these visual messages, the poster accentuates the divisions between different class groups in Swedish society that were already fraught at the time.

Underneath the image is a slogan in black that warns voters to ‘BREAK THE SHACKLES OF ALCOHOL’, the colour serving as a subtle indicator of badness and the imperative acting as a command. ‘VOTE YES’ then follows in large bright red lettering and an exclamation mark to emphasize the point. Thus, here, banning alcohol is about protecting the country and preventing the rich from becoming richer. This stands in strong contrast to the ‘breakdown of family life’ posters, which promote alcohol itself as the root of evil and stress its negative effects on individual lives.

The breakdown of Swedish society: the “No” campaign

The ‘no’ campaign focuses many of its arguments on the breakdown of Swedish society around the notions of freedom, openness and transparency. One reoccurring assertion is that prohibition will encourage a culture of espionage and whistleblowing in Sweden, leading neighbours to spy on one another and report illegal distilling or smuggling to the police. This is emphasized in posters by images of men dressed in black – the colour of evil – sneaking around at night and peering through windows to watch their neighbours. Accompanying captions ask rhetorical questions, such as ‘should spies and whistleblowers be trained by prohibition?’, or warn potential voters that ‘on 27 August, your personal freedom will be determined’. These provocative statements imply that a vote in favour of prohibition will curb freedom of movement, but also turn the whole country into informers. In a similar vein, other posters claim that banning alcohol will result in false arrests as neighbours will become overly suspicious and paranoid of one another. This point is demonstrated through the juxtaposition of images of people enjoying a soft drink with images of the police creeping up behind them brandishing swords and angry citizens shouting to arrest them because the drink is probably fermented. This scaremongering aims to stir up panic and convince voters that their everyday activities will be under constant scrutiny, thereby taking away their personal freedoms. Like in previous ‘no’ campaign posters, the ‘no’ is emphasized in red to signal a warning of danger ahead, but additionally, the letters are often constructed in such a way that they resemble planks of wood hammered together with nails. This framing forms a symbolic barrierFootnote61 between members of Swedish society, suggesting that prohibition will foster divisions.

Threats to freedom and equality are also expressed in more metaphorical ways by using imagery to stir up class warfare. Just as in the ‘yes’ campaign, the ‘no’ campaign portrays the Riksdag as a chamber of entitled elites who impose their will on the populace and uses the figures of an oversized muscular man to represent the Swedish people and a man in a top hat and tuxedo to represent the Government. The two are often engaged in battle with one another on top a red backdrop – used to signal danger and aggression – while the accompanying slogans are linked to class warfare, directly asking the public such questions as ‘Do you want freedom? Vote no no no!’ Another key figure used by the ‘no’ campaign is Mother Svea, the female personification of Sweden. Often, she is flanked by a snarling lion and portrayed in yellow and green – the national colours – as she holds up her hand in a stop gesture to the suited politician or looks over a map of Sweden in dismay. Captions ask ‘Shall Svea fall for her tempter?’ or ‘Which part of Sweden should be surrendered?’ which imply that prohibition will lead to the disintegration of the country. Although no reason is provided for this possible outcome, the inclusion of a patriotic emblem that represents stability and respectability is a powerful way of playing to the public’s emotions.Footnote62

Another significant subgenre of posters is those that make appeals to the Swedish public by focusing specifically on how prohibition will affect their daily rituals and traditions, particularly in terms of food and drink. A frequently reoccurring image is the elderly female peasant who warns that prohibition will make the price of coffee soar. Then, as now, Sweden was one of the biggest coffee drinkers in the world and fika – roughly defined as a coffee break with friends – was considered a social institution, integral to strengthening relationships between people.Footnote63 To suggest that this intrinsic part of Swedish culture will be under threat with prohibition elicits an emotional reaction from the public, which is more likely to make them vote no. Similarly, other posters make reference to kräftskiva –the Crayfish Party – which is a traditional summertime eating and drinking celebration with roots in the eighteenth century.Footnote64 Images show plates of crayfish alongside a stern-faced man who, pointing at a bottle of beer, warns that ‘crayfish require these drinks’ and that if the ‘yes’ campaign wins, ‘you must abstain’ from them. Like the coffee posters, these are highly emotive and suggest that a vote for prohibition is a vote for the eradication of an important Swedish ritual.

“Do you want to let a small minority curb your freedom of action”: a multimodal critical discourse analysis

The poster in promotes the idea that prohibition will pose a risk to personal freedom in order to convince the public to vote ‘no’ in the referendum. Like the posters for the ‘yes’ campaign, it depicts a figurative battle between the Swedish people and the Government, as played out through two central images. On the left, we see the large, muscular, naked man associated with the PCM, but here, he is depicted as weak and vulnerable. This is emphasized by his kneeling position with head bowed and face twisted into a grimace, as well as his hands fastened tightly behind his back with rope. He makes no attempt to break free from his bonds and seems to have resolutely accepted his fate. The non-frontal perspective turns us into passive observers who are unable to intervene; Footnote65 this strengthens the emotional appeal of the poster as we are forced to watch the man and his suffering. The pale blue of the man’s body carries strong connotations of depression and sadness,Footnote66 thereby further accentuating his anguish to viewers and, by the same token, the gloomy prospects for the future of Sweden.

Figure 4. “Do you want to let a small minority curb your freedom of action”: breakdown of Swedish society (“No” campaign).

Standing behind the man is the familiar figure of the politician in a black tuxedo and top hat. This time, however, he is portrayed as slim, cunning and in control of the situation. The figure, in fact, carries subtle anti-Semitic undertones, drawing upon derogatory physical stereotypes of Jewish people used throughout history (e.g. hooked nose, dark beady eyes, beard), as well as stereotypical personality traits of being greedy and avaricious, while the black suit of the figure connotes evil and slyness.Footnote67 Even though there were only 6,500 Jews in Sweden in 1922, similar stereotypes were frequently used in the left-wing press to depict Jews as capitalists obsessed with money.Footnote68 Letters to the government from concerned Swedes at the time warned that Jews were ‘a state within the state, whose interests do not coincide with those of the rest of the population’.Footnote69 Thus, the poster not only plays upon prevalent fears of the Swedish people around the power of Jews and the threat they pose to the Swedish way of life, but also projects these fears onto the context of the Government, suggesting that it is Jewish people who secretly pull the strings. These fears are heightened by the fact that the figure in black is much smaller than the other man, yet is able to easily restrict him, thus warning of the danger of the referendum for the Swedish people. The bright red of the background, which symbolizes danger, also strengthens this message.

The slogan underneath the poster works in tandem with the image, underlining the major argument of the ‘no’ campaign. It begins with direct address—‘SWEDISH PEOPLE’—in block capitals and white font, immediately demanding attention. This is followed by the rhetorical question: ‘DO YOU WANT TO LET A SMALL MINORITY CURB YOUR FREEDOM OF ACTION?’ The phrase ‘SWEDISH PEOPLE’ carries nationalistic and jingoistic undertones, while the personal pronoun ‘you’ puts responsibility onto each individual and the value-laden word ‘let’ implies that a failure to act by voting no will have disastrous consequences for Sweden. ‘SMALL MINORITY’ is written in red font, serving to highlight the notion that the future of the country will be decided by several members of the cultural elite and, thus, creates divisions on the grounds of class and wealth. Here, the message centres particularly around the concept of handlingsfrihet, roughly translated as ‘freedom of action’ but incorporating the ability to speak and act freely without any external coercion or constraints. This core aspect of being Swedish is positioned as under threat without a vote against prohibition. ‘No’ is repeated twice in black across the centre of the poster, with individual dots between each letter to prolong and emphasize the words. Overall, despite the opposing arguments of the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaign, both challenge the integrity of the Swedish government in their posters with the aim of demonstrating that the referendum will be destructive to the country’s core values and principles.

Concluding discussion

Following the announcement of a referendum on the prohibition of alcohol in 1922, Sweden became gripped in an ideological battle between two conflicting beliefs about its future. On one side was the ‘vote yes’ campaign, led by the temperance societies and convinced that prohibition was the only way to stop drunkenness, domestic abuse and poverty on an individual level, as well as to prevent the growth of capitalism and social inequalities on a national level. On the other was the ‘vote no’ campaign, ran by the newly founded National Association for Sobriety Without Prohibition and strongly against prohibition on the grounds that it would encourage smuggling, illegal distilling and false arrests, and pose a direct challenge to Swedish values.

Over an eight-month period, both sides carried out an extensive propaganda campaign, using posters to ‘sell’ their arguments to the public in a palatable and engaging format. Despite their opposing views, ‘yes’ and ‘no’ posters both focused on two main themes: the breakdown of family life and the breakdown of Swedish society. ‘Yes’ posters tended to concentrate on an imagined present, juxtaposing images of drunk, aggressive fathers with scared mothers and children to emphasize the dangers of alcohol. They also made strong use of the symbolic meanings of black and white to reframe the debate as a battle between good and evil. Taking advantage of the fact that women had been recently emancipated, posters also directly addressed mothers through personal pronouns and emotive language, serving to build upon the sense of comradeship and solidarity fostered by the suffrage campaign to convince them to vote in favour of prohibition for the good of their children. Other posters accentuated the threats to society posed by the current Bratt System, using figurative images of the Swedish people versus Government, infographics and blocks of text laying out rational arguments.

The ‘no’ campaign, on the other hand, focused on an imagined future, conjuring up scary images of a Sweden in which, deprived of alcohol, people poisoned themselves with household products, illegally distilled alcohol at home, smuggled it on boats and spied on their neighbours and reported them to the police. The fact that the whole family is shown witnessing or taking part in these acts strengthened their emotional impact, as did the supporting sarcastic straplines, personal pronouns, red backdrops and images of snakes to indicate personal responsibility and a sense of impending doom. In other posters, threats centred around prohibition leading to a curbing of individual freedom of action or an end of Swedish traditions, such as fika and kräftskiva. In these cases, popular images included the metaphorical depictions of the Swedish people versus Government, Mother Svea and elderly peasants.

On the surface, these linguistic and semiotic choices suggest strong differences between the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns. However, MCDA reveals that the two sides were far more similar than they perhaps would care to admit. In ‘breakdown of family life’ posters, for example, both sides used individual family stories to provide specific narratives that humanized the campaign and played upon the emotions of viewers. Furthermore, both called on the Swedish people to ‘do their duty’ and protect fellow Swedes; not to do so was to be an irresponsible, bad citizen. Both also used images not only to imply that alcohol was a predominantly male problem, but also that it was a working-class problem, as emphasized by certain choices of clothing (e.g. stained overalls, bowler hat, tieless shirt). Additionally, both used posters to stir up class warfare: they set the Swedish people against the Government, using classical revivalist representations of the male figure and embedding them in the rhetoric of the PCM to showcase arguments around capitalism and individual freedom. However, the ‘no’ campaign went one step further, drawing on Antisemitic stereotypes in its depiction of the cultural elite. While the ‘yes’ campaign did not resort to casual racism in its posters, it was at times contradictory. Its overwhelming critique of the Bratt System, for example, was ironic when sobriety associations had strongly supported it, while its criticism of the ‘capitalist’ government was also paradoxical when the majority of the money made from alcohol sales was invested back into local services.

On 27 August – the day of the referendum – 1.8 million people turned out to vote. The vote had unprecedented political interest, with the turnout much higher than expected at 55.1% (more than the preceding parliamentary election, which had a turnout of 54.2%).Footnote70 The result: 49% in favour of prohibition and 51% against, giving a marginal win to the ‘no’ side. While it is hard to assess the extent to which the poster campaign contributed to this outcome, some assertions can be made based on an analysis of the votes. First, there were major differences on the grounds of geographical location, with the north and rural areas voting strongly in favour of prohibition compared to the south and urban areas.Footnote71 There is a strong correlation between the areas that voted yes and the areas where temperance societies were well-established (e.g. Norrland, Småland). Equally, there is a notable relationship between the areas that voted no and the areas that the Systembolaget favoured in its rationing (e.g. cities and south). This suggests that it was not so much the posters that influenced voters’ decisions, but rather their own personal circumstances, regional traditions and historical ties. Furthermore, ballots had been issued in two different colours in order to track male and female votes. Analysis also revealed major differences across Sweden based on gender, with 59% of women voting in favour of prohibition compared to 41% of men.Footnote72 This suggests that the ‘yes’ campaign’s targeted focus on mothers with personal stories was successful in stirring their emotions sufficiently and convincing them to vote in favour of prohibition.

Although propaganda posters were only one part of the way that the campaign was fought, there is some indication that the ‘no’ campaign was more successful overall because it was able to use posters to play on voters’ emotions by conjuring up a scary imagined future. The ‘yes’ campaign, on the other hand, relied on an imagined present that could be easily recognized as false by many voters and often used large blocks of text to outline arguments, which were not as engaging as the punchy slogans, colours, and images of the ‘no’ campaign and likely put off some voters, even though the arguments were rational. Similar findings have been made in a contemporary context, particularly around the result of the Brexit referendum.Footnote73

Despite the close result of the referendum, it was considered a victory, which enabled the government to finally close the issue of prohibition and continue with the Bratt System rationing already in place. The Riksdag implemented some changes, however, including a ban on the sale of strong beer and strong cider and a legal requirement for bars and pubs to serve food with alcoholic beverages. The temperance movement, on the other hand, changed its focus, emphasizing enlightenment and moderation now rather than an outright ban on alcohol. Although rationing ended in 1955, Sweden still has some of the strictest alcohol measures in Europe. All alcohol stronger than 3.5% by volume is sold only in Systembolaget and customers must be 20 years old to purchase it. Furthermore, alcohol can still only be sold in bars and pubs if hot food is offered. Finally, alcohol is taxed more highly than in most other European countries. Thus, although prohibition was ultimately unsuccessful, the effects of the hard-fought campaign and the aftermath of the referendum are still evident in Sweden today.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Alex O’Hagan

Lauren Alex O’Hagan is currently a Researcher in the School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences at Örebro University, Sweden, where she works on the ‘Selling Healthy Lifestyles with Science’ project. She specialises in performances of social class and power mediation in the late 19th and early 20th century through visual and material artefacts, using a methodology that blends social semiotic analysis with archival research. She has published extensively on the sociocultural forms and functions of book inscriptions, food packaging and advertising, postcards and writing implements.

Notes

1. Johansson, Systemet lagom.

2. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis; Ledin and Machin, Doing Visual Analysis.

3. Seidman, Posters, Propaganda, and Persuasion.

4. Landsberger, Chinese Propaganda Posters; Suglo, “Visualizing Africa … ”.

5. Bonnell, Iconography of Power; Williams, “Let’s Smash It!”.

6. McCrann, “Government Wartime Propaganda Posters”; Kingsbury, For Home and Country.

7. Johansson, “Negativity in the Public Space”; Håkansson, Johansson, and Vigsø, “From propaganda to image building”.

8. Instead, studies have tended to concentrate on the debates in Parliament around the topic (Johansson, Systemet lagom; Johansson, Staten, supen och systemet), gendered perspectives on alcohol consumption at the time (Knobblock, Systemets långa arm) or the impact of the referendum in specific cities, such as Lund (Hultgren, För vår skull rösta nej!), Luleå (Moslem, Rusdrycksforbudet 1922), and Umeå (Frånberg, Umeåsystemet).

9. van Leeuwen, “Critical Discourse Analysis and Multimodality,” 248.

10. Hellspong, Korset, fanan och fotbollen.

11. Johansson, Staten, supen och systemet.

12. Lindberg, “Motbokens avskaffande”.

13. Ibid.

14. Johansson, Systemet lagom.

15. Schrad, The Political Power of Bad Ideas, 96.

16. Ibid, 102.

17. Ibid.

18. Johansson, Staten, supen och systemet.

19. Johansson, Systemet lagom.

20. Ibid.

21. Karlsson, ”att driva ut djävulen i en av hans värsta skepnader”.

22. Johansson, Systemet lagom.

23. Gustavsson, ed., Alkohol och nykterhet.

24. Wollaeger, Modernism, Media, and Propaganda, 80.

25. Propagandacentralen N.E.J. printed 60,000 copies of their 12 poster series. They also presented them in a booklet, which was printed in 45,000 copies.

26. van Leeuwen, “Critical Discourse Analysis and Multimodality”, 288.

27. Johansson, “Negativity in the Public Space”; Seidman, Posters, Propaganda, and Persuasion …

28. Machin and Mayr. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis.

29. Machin, “What is multimodal critical discourse analysis?”

30. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis; Ledin and Machin, Doing Visual Analysis.

31. Ross and Bhatia, “Ruled Britannia”.

32. Somerville and Kirby, “Public relations and the Northern Ireland peace process”; Quinlan, “The Lisbon Treaty Referendum 2008”; Murphy, “The marriage equality referendum 2015”; Murphy et al., “False Memories for Fake News … ”.

33. O’Hagan, “Home Rule is Rome Rule”; O’Hagan, “Contesting women’s right to vote”.

34. Mathew, “‘Wish you were (not) here”; Wilson, Luftwaffe Propaganda; Sturani, Analysing Mussolini Postcards”.

35. Rosch, “Reclaiming concepts”.

36. Kress and van Leeuwen, “Colour as a semiotic mode,” 348.

37. Frånberg, Umeåsystemet, 139.

38. Ibid.

39. Kress and van Leeuwen, “Colour as a semiotic mode,” 353–4.

40. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 98.

41. Hasler, “A Show of Hands”.

42. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 84, 182.

43. Ibid.

44. Löfgren, “The Sweetness of Home Class, Culture and Family Life in Sweden”.

45. Williams, “‘Let’s Smash It!”.

46. Charlesworth, The Good and Evil Serpent.

47. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 165.

48. Kress and van Leeuwen, “Colour as a semiotic mode,” 354.

49. Ibid, 343.

50. Kress and van Leeuwen, Reading Images, 122.

51. Bielinski, “Steeped in Modernism”.

52. Richards, Commodity Culture of Victorian Britain, 134.

53. Kress and van Leeuwen, Reading Images, 122.

54. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 171.

55. Ericsson and Nyzell, “Sweden 1910–1950”.

56. Johansson and Jansson, “Glasbankens hemlighet”. As mentioned earlier, only 5% of women in Sweden had a motbok at this time.

57. Berk, “Temperance and Prohibition Era Propaganda”.

58. Heffernan, “Truly muscular Gaels?”.

59. Pfister, “Cultural confrontations,” 74.

60. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 171.

61. Ledin and Machin, Introduction to Multimodal Analysis, 180.

62. Tornbjer, Den nationella modern.

63. Mäkelä. “Cultural Definitions of a Meal.

64. Anon. “Kräftskivan”.

65. Ibid., 82.

66. Ibid., 89.

67. Baigell, The Implacable Urge to Defame.

68. Oredsson, “Judehatet kom före judarna”.

69. Ibid.

70. Johansson, Systemet lagom.

71. Systembolaget, “Systembolagets historia”.

72. Knobblock, Systemets långa arm, 87.

73. Moss, Robinson and Watts, “Brexit and the Everyday Politics of Emotion”; Rosa and Jiménez Ruiz, “Reason vs. emotion in the Brexit campaign”.

References

- Anon. “Kräftskivan – En svensk tradition.” Gentlemannaguiden. Accessed August 15, 2020. https://gentlemannaguiden.com/kraftskivan-en-svensk-tradition/

- Baigell, Matthew. The Implacable Urge to Defame: Cartoon Jews in the American Press, 1877-1935. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2017.

- Berk, Leah Rae. Temperance and Prohibition Era Propaganda: A Study in Rhetoric (2004), https://library.brown.edu/cds/temperance/essay.html

- Bielinski, Maya. “Steeped in Modernism: The Teapot as Manifesto in Early 20th Century Art.” Inquiry@Queen’s Undergraduate Research Conference Proceedings, 2010. doi:10.24908/iqurcp.8439.

- Bonnell, Victoria E. Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Charlesworth, James H. The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Ericsson, Martin and Stefan Nyzell. ”Sweden 1910-1950: The Contentious Swedes – Popular Struggle and Democracy.” In Popular Struggle and Democracy in Scandinavia: 1700-Present, edited by Flemming Mikkelsen, Knut Kjeldstadli, and Stefan Nyzell, 319–337. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Frånberg, Per. “Umeåsystemet: en studie i alternativ nykterhetspolitik 1915-1945.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Umeå University, 1983.

- Gustavsson, Anders, ed. Alkohol och nykterhet. Aktuell forskning i Norden presenterad vid ett symposium i Uppsala. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet, 1989.

- Håkansson, Niklas, Bengt Johansson, and Orla Vigsø. ”From Propaganda to Image Building: Four Phases of Swedish Election Poster History.” In Election Posters Around the Globe, edited by Christina Holtz-Bacha and Bengt Johansson, 319–337. Cham: Springer, 2017.

- Hasler, Charles. “A Show of Hands.” Typographica 8 (1953): 4–11.

- Heffernan, Conor. “Truly Muscular Gaels? W.N. Kerr, Physical Culture and Irish Masculinity in the Early Twentieth Century.” Sport in History 41, no. 1 (2021): 1–24. doi:10.1080/17460263.2019.1655088.

- Hellspong, Mats. Korset, fanan och fotbollen. Stockholm: Carlsson, 1991.

- Johansson, Lennart. Systemet lagom: rusdrycker, intresseorganisationer och politisk kultur under förbudsdebattens tidevarv 1900-1922. Lund: Lund University, 1995.

- Johansson, Lennart. Staten, supen och systemet: svensk alkoholpolitik och alkoholkultur 1855-2005. Stockholm: Brutus Östlings, 2008.

- Johansson, Bengt. ”Negativity in the Public Space: Comparing a Hundred Years of Negative Campaigning on Election Posters in Sweden.” In Comparing Political Communication Across Time and Space, edited by María José Canel and Katrin Voltmer, 67–82. London: Springer, 2014.

- Johansson, Ambjörn and Anders Jansson. ”Glasbankens Hemlighet – Spritransonering Och Social Masskontroll.” Sveriges Radio (December 5, 2016). https://sverigesradio.se/avsnitt/816542?programid=909.

- Karlsson, Carl Michael. “”att driva ut djävulen i en av hans värsta skepnader”: En studie om förbudsomröstningen 1922 i Jönköping och Lund.” Unpublished undergraduate dissertation, Uppsala University, 2015.

- Kingsbury, Celia M. For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Knobblock, Inger. “Systemets långa arm: en studie av kvinnor, alkohol och kontroll i Sverige 1919-1955.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Umeå University, 1995.

- Kress, Gunther and Theo van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Kress, Gunther and T. van Leeuwen. “Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour.” Visual Communication 1, no. 3 (2002): 343–368. doi:10.1177/147035720200100306.

- Landsberger, Stefan. Chinese Propaganda Posters: From Revolution to Modernization. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Ledin, Per and David Machin. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. London: SAGE, 2018.

- Ledin, Per and David Machin. Doing Visual Analysis. London: SAGE, 2020.

- Lindberg, Bertil. “Motbokens avskaffande – nykterhetsrörelsens sista stora nykterhetspolitiska projekt.” Nykterhetshistoriska Sällskapet, 2018. http://www.nykterhetshistoriskasallskapet.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Motboken.pdf

- Löfgren, Orvar. “The Sweetness of Home Class, Culture and Family Life in Sweden.” Ethnologia Europaea 14 (1984): 44–64.

- Machin, David. “What is Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis?” Critical Discourse Studies 10, no. 4 (2013): 347–355. doi:10.1080/17405904.2013.813770.

- Machin, David and Andrea Mayr. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE, 2012.

- Mäkelä, J. ”Cultural Definitions of a Meal.” In Dimensions of the Meal: The Science, Culture, Business and Art of Eating, edited by Herbert L. Meiselman, 7–18. Gaitersburg: Aspen Publishers, 2000.

- Mathew, Tobie. “Wish You Were (Not) Here: Anti-Bolshevik Postcards of the Russian Civil War, 1918-21.” Revolutionary Russia 23, no. 2 (2010): 183–216. doi:10.1080/09546545.2010.523070.

- McCrann, Grace Ellen. “Government Wartime Propaganda Posters: Communicators of Public Policy.” Behavioral & Social Science Librarian 28, no. 1–2 (2009): 52–73.

- Moss, Jonathan, Emily Robinson, and Jake Watts. “Brexit and the Everyday Politics of Emotion: Methodological Lessons from History.” Political Studies 68, no. 4 (2020): 837–856. doi:10.1177/0032321720911915.

- Murphy, Yvonne. “The Marriage Equality Referendum 2015.” Irish Political Studies 31, no. 2 (2016): 315–330. doi:10.1080/07907184.2016.1158162.

- Murphy, Gillian, E F. Loftus, R H. Grady, L J. Levine, and C M. Greene. “False Memories for Fake News During Ireland’s Abortion Referendum.” Psychological Science 30, no. 10 (2019): 1449–1459. doi:10.1177/0956797619864887.

- O’Hagan, Lauren Alex. “Contesting Women’s Right to Vote: Anti-Suffrage Postcards in Edwardian Britain.” Visual Culture in Britain 21, no. 3 (2020): 330–362. doi:10.1080/14714787.2020.1827971.

- O’Hagan, Lauren Alex. “‘Home Rule is Rome Rule’: Exploring Anti-Home Rule Postcards in Edwardian Ireland.” Visual Studies 35, no. 4 (2020): 330–346. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2020.1779612.

- Oredsson, Sverker. “Judehatet kom före judarna.” Populär Historia. Accessed March 19, 2001. https://popularhistoria.se/sveriges-historia/judehatet-kom-fore-judarna

- Pfister, Gertrud. “Cultural Confrontations: German Turnen, Swedish Gymnastics and English Sport – European Diversity in Physical Activities from a Historical Perspective.” Culture, Sport, Society 6, no. 1 (2003): 74.

- Quinlan, Stephen. “The Lisbon Treaty Referendum 2008.” Irish Political Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 107–121. doi:10.1080/07907180802674381.

- Richards, Thomas. Commodity Culture of Victorian Britain. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

- Rosa, Jorge Martins and Cristian Jiménez Ruiz. ”Reason Vs. Emotion in the Brexit Campaign: How Key Political Actors and Their Followers Used Twitter.” First Monday 25, 3 (March, 2020). 10.5210/fm.v25i3.9601.

- Rosch, E. “Reclaiming Concepts.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 6, no. 11–12 (1999): 61–77.

- Ross, Andrew S. and Aditi Bhatia. “‘Ruled Britannia’: Metaphorical Construction of the EU as Enemy in UKIP Campaign Posters.” The International Journal of Press/politics 26, no. 1 (2021): 188–209. doi:10.1177/1940161220935812.

- Schrad, Mark Lawrence. The Political Power of Bad Ideas: Networks, Institutions, and the Global Prohibition Wave. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Seidman, Steven A. Posters, Propaganda, and Persuasion in Election Campaigns Around the World and Through History. London: Peter Lang, 2008.

- Somerville, Ian and Shane Kirby. “Public Relations and the Northern Ireland Peace Process: Dissemination, Reconciliation and the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ Referendum Campaign.” Public Relations Inquiry 1, no. 3 (2012): 231–255. doi:10.1177/2046147X12448370.

- Sturani, Enrico. “Analysing Mussolini Postcards.” Modern Italy 18, no. 2 (2013): 141–156. doi:10.1080/13532944.2013.780425.

- Suglo, G.D. “Visualizing Africa in Chinese Propaganda Posters 1950–1980.” Journal of Asian and Africa Studies (2021). doi:10.1177/00219096211025807.

- Systembolaget. “Systembolagets Historia.” 2021. http://www.systembolagethistoria.se/Teman/Ursprunget/Motbokstvang-och-folkomrostning/

- Tornbjer, Charlotte. “Den nationella modern: Moderskap i konstruktioner av svensk nationell gemenskap under 1900-talets första hälft.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Lund University, 2002.

- van Leeuwen, Theo. ”Critical Discourse Analysis and Multimodality.” In Contemporary Critical Discourse Studies, edited by Christopher Hart and Piotr Cap. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Williams, Christopher. “‘Let’s Smash It!’ Mobilizing the Masses Against the Demon Drink in Soviet-Era Health Posters.” Visual Resources 28, no. 4 (2012): 355–375. doi:10.1080/01973762.2012.732206.

- Wilson, James. Luftwaffe Propaganda: A Pictorial History of the Luftwaffe in Original German Postcards. Ramsbury: Motorbooks International, 1996.

- Wollaeger, Mark. Modernism, Media, and Propaganda: British Narrative from 1900 to 1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.