ABSTRACT

Employing the Foucauldian term ‘conduct’, this article explores how social resilience and morale became a target of state intervention in Denmark during the Cold War. ‘Psychological defence’ was a Cold War phenomenon designed to bring an imagined future war into a space of control as well as a tool for the authorities’ exercise of power in case another world war became a reality. Advocating a methodological internationalism, the article analyses how the concept of psychological defence travelled from Sweden to Denmark via Norway and NATO, and in a complex process of translation, mixing and hybridization was adapted and appropriated to Danish security policy conditions, preparedness culture, and historical experiences. Ultimately, psychological defence was replaced with a more practical or even cynical approach to public information and media preparedness, even if the objectives remained the same. The article employs source material from Danish, Swedish, and NATO archives and combines Scandinavian Cold War history with media history and the history of knowledge.

Arthur Dahl’s memorandum

In late December 1954, Arthur Dahl, the Director of the Danish Civil Defence Directorate (CDD), composed a memorandum urging his superiors at the Ministry of the Interior to start concerning themselves with the population’s ‘psychological defence’.Footnote1 Dahl explained that in order to fight the Cold War, it was vital to strengthen the morale and mental resilience of the whole population: If the home front crumbled, a future war would be lost. Moreover, he warned, modern technologies such as film, television, and radio facilitated the easy spread of propaganda, disinformation, and false rumours. Dahl described in detail the ambitious plans in neighbouring Sweden to create an institution dedicated to psychological defence, and he added that developing some form of parallel organization at home was even more acute because Norway, too, had taken steps in this regard. Denmark was lagging in this vital matter.

Dahl’s memorandum signals the beginning of the history of psychological defence in Denmark. This is a history of how popular morale, resilience, and actual as well as anticipated conduct became a target of state intervention. It is not merely a Danish history, however. As indicated by the memorandum, it is an international history of how Cold War preparedness was inspired and shaped by external influences, contacts, and collaborations. In this article we examine the planning and development of Danish psychological defence during the Cold War focusing on how inspiration and knowledge was sought from, imposed by, or discussed with other partners. We employ source material from Danish, Swedish, and NATO archives to examine a simultaneously bilateral and multilateral knowledge and policy encounter and translation.

The article proceeds with a presentation of its historiographical foundations, where we combine two interrelated bodies of literature: Cold War historiography, including civil defence and preparedness studies, and studies of propaganda, media, and communication. In the following section, we introduce the theories of international knowledge transfer we use to unpack the development of psychological defence in the early Cold War, as well as the Foucauldian concept of ‘conduct’ that we employ to examine how information and knowledge transfer is linked to issues of influence and power. Next, we turn our gaze towards Sweden, the frontrunner of Scandinavian psychological defence, before returning to Dahl’s memorandum and focusing on the emerging belief of a nexus between information and resilience. We continue to trace how NATO entered the stage, followed by an in-depth analysis of the development of Danish psychological defence in the first two decades of the Cold War with comparative glances towards Sweden and Norway. We conclude by positioning the discussions of Danish psychological defence between Sweden, Norway, and NATO.

We argue, first, that psychological defence was a vital element in bringing the imagined future war into a space of control and a key part of the authorities’ exercise of power in case this war became a reality. Second, advocating a ‘methodological internationalism’, we contend that to study how knowledge about psychological defence was developed and put into practice, we need to go beyond a mononational context. Indeed, the concept of psychological defence travelled across the sound separating Denmark and Sweden, though zigzagging rather than going directly, and in the end, the Danes chose their own variant, which included mixing and appropriating of several foreign impulses and an adaptation to its own culture of preparedness. By looking at the Danish case through this international lens, we contribute to a broader understanding of how knowledge and concepts travel between different countries and are adapted in the process.

Historical contexts and previous research

As the Cold War materialized, the Scandinavian countries initially sought security with the 1948–9 negotiations on a Scandinavian Defence Union. Negotiations, however, broke down over differences between Norway, who wanted such a union associated with the Western powers, and Sweden who wanted to adhere to strict neutrality. Denmark leaned towards the Swedish standpoint but would have been happy with any arrangement.Footnote2

After Norway accepted an invitation to join the Atlantic Pact (later NATO), the less enthusiastic Denmark followed. For the governing Social Democratic Party, it was a choice between two evils, isolated neutrality, or a US-dominated alliance,Footnote3 and the population was split on the issue. Throughout the Cold War, as especially Rolf Tamnes and Poul Villaume have established, both Denmark and Norway were somewhat reserved allies, balancing NATO integration with national screening such as reservations on nuclear weapons and stationing of US troops.Footnote4 Nonetheless, the description of a foot-dragging Denmark needs to be nuanced: in terms of civil emergency planning, Denmark became a top member.Footnote5 Sweden remained non-aligned in peacetime, aiming at neutrality in war throughout the Cold War.

In the era of total war, the entire industrial capacity of a country was critical to its war effort and terror bombings of civilians were part of the game. Total war necessitated total defence: not only military defence, but also civil defence (efforts to protect civilian populations) and civil emergency planning (emergency governance and plans to ensure the continuation of production, transportation, communication etcetera) that would allow society to keep functioning, to some extent at least, during a war. Preparedness planning provided a way of grasping an uncertain, potentially catastrophic future, and bringing it into a space of present intervention as a political problem.Footnote6 Preparedness and emergency planning was (and is) not concerned with preventing a disaster from happening, but with preparations to make it manageable.

Nuclear culture and civil defence constitute a small but well-established research subfield in Anglo-American Cold War historiographies, where scholars have demonstrated how nuclear technology and anxiety influenced all spheres of society.Footnote7 In the same way as ‘the bomb’ was a global problem, the issue of preparedness presented itself to the competing blocs and neutral countries alike, and Scandinavia was no exception. Sweden developed an extensive civil defence organization, and Marie Cronqvist has detailed how the Swedish culture of preparedness became embedded in narratives of ‘the good’ (welfare) society.Footnote8 Danish historians have only recently started examining this part of the Cold War experience. The history of the CDD and its voluntary associations has been researched by Casper Sylvest with a particular focus on nuclear anxiety and emotion management, whereas Iben Bjørnsson has studied the cooperation between NATO and the CDD, and Rosanna Farbøl has examined local and urban policies, practices, and materialities of civil defence.Footnote9 In Norway, this seems a less developed field, though the total defence in general has been the focus of MA theses.Footnote10

The Cold War was a global ideological struggle that included competition for hearts and minds. Both sides used newspapers, radio, television, film, and other media to promote their propaganda, but also more sinister methods such as disinformation and false rumours.Footnote11 Psychological warfare of course predated the Cold War. In the interwar years, propaganda emerged as a key concept in relation to the Spanish Civil War and the Nazi regime in Germany, but the World War era and the early Cold War also saw the entanglement of psychological warfare and American social science communication research, a topic that has been researched by scholars such as Timothy Glander and Christopher Simpson.Footnote12

What has so far received less attention, within Scandinavia as well as abroad, is the other side of the coin: psychological defence. Currently, however, a research field is beginning to take shape in Sweden, also spurred by a governmental authority launched in 2019, the Psychological Defence Agency.Footnote13 Besides detailing the early institutional history of the Swedish psychological defence, new research has pointed to close interrelations between psychological defence and academic mass communication research, as in the US.Footnote14 In Denmark, the question of civil defence information has been in focus of a number of studies,Footnote15 but the wider topic of psychological defence and media preparedness has so far only been treated as a part of Bodil Frandsen’s PhD dissertation about the entire civil emergency planning,Footnote16 an important first step that takes us part of the way towards uncovering the history of psychological defence. Yet, we still lack knowledge about the meeting of foreign influences and Danish preparedness culture as well as more systematic and theoretically informed reflections on the development of psychological defence.

International knowledge transfer, power, and conduct

We take our lead from perspectives within the vibrant field of historical research which since the early 2000s in different ways – using various concepts such as transnational history, global history, transfer history, or entangled history – has begun to challenge the traditional preoccupation with the nation as the single and natural unit of study.Footnote17 This is not a call to do away with the nation but to understand it as a ‘stable moment’ in a series of past hybridizations,Footnote18 and to acknowledge that its history is one of cross-border influences, connections, and interferences. Rephrasing the call to interlinked or entangled histories, we suggest a ‘methodological internationalism’ when approaching Cold War preparedness to better uncover the flows and interconnections of knowledge at the heart of any national defence strategy.

The differences (and similarities) between international history and transnational history are matters of continuous academic debate. An often-used distinction is that ‘international’ implies an interstate – in practice often bilateral – relationship, whereas ‘transnational’ suggests multiple inter-societal interactions and crossings.Footnote19 We define our topic as an international history of knowledge transfer because we maintain the top-down focus on relations between states, but we broaden the scope to include more than bilateral diplomacy and foreign affairs, and we trace the interactions, crossings and negotiations of knowledge and policies of preparedness, resilience, and psychological defence among and between three nations and one inter-state organization.

As Michel Espagne has pointed out, any act of cultural transfer of knowledge is a matter of translation and, thus, for the researcher, the concept offers a possibility to rethink simple dichotomies such as centre and periphery, sender and receiver, and in-going and out-going knowledge. A translation is no less legitimate than its model, and no less original.Footnote20 It opens for perspectives on cultural mixing, appropriation, and hybridization given the local, regional, global – or national – context. Unlike most transfer studies that tend to focus on the reception of a given feature in a new context, we include the origins, in this case the Swedish conceptualizations of psychological defence, but moreover, going beyond the start and end points of the journey, we study intermediate ‘stop-overs’, such as NATO and Norway, in order to analyse the entire process of translation, including clashes as well as coalescence, and pay attention to how links were made, remade, resisted or broken.

Since we are interested in the transfer and reshaping of knowledge, we also attach our study to recent scholarship on the history and especially the circulation of knowledge.Footnote21 In this we specifically stress the fact that knowledge is not a pre-fixed package or container that circulates; constantly in transit, it is also constantly transfigured in often asymmetric and ever-changing power relationships. When objects fall into a new context, they take on new meaning.

A key aspect in this study is the way in which information and knowledge transfer are inextricably linked to issues of influence and power. As Alistair Black and Bonnie Mak have put it, ‘information – its collection, storage, organization, dissemination, and accessibility – is central to the way power is executed and questioned’.Footnote22 We understand psychological defence as a way of ensuring the status quo in the power relationship between authorities and the population as much as it is about defence; indeed, these two are intimately connected.

To explore this further, it is enlightening to see psychological defence through the prism of the Foucauldian concept of ‘conduct’, introduced in ‘The Subject and Power’ (1982).Footnote23 Conduct links power and governmentality and can be understood, like subjectivity, in two ways: ‘To “conduct” is at the same time to “lead” others (according to mechanisms of coercion which are, to varying degrees, strict) and a way of behaving within a more or less open field of possibilities’.Footnote24 Hence, it denotes an individual’s personal behaviour and choices as well as leading, guiding or directing others, which can be confrontational or against their interest but does not have to be.

Unlike Foucault’s earlier works on power, here he stresses that ‘conduct’ can be consensual; indeed, without the freedom of choice, there would be no power and no conducting. In democracies, public opinion matters. The key problem of government, according to Foucault, is ‘the conduct of conduct’ because ‘[t]he exercise of power consists in guiding the possibility of conduct and putting in order the possible outcome’.Footnote25 Through psychological defence, the authorities sought to conduct the conduct of the population and direct them into conducting themselves in a specific way that resonated with official political rationales and strategies of preparedness planning.

Swedish psychological defence

To follow the development of a structure and organization for psychological defence in Denmark, it is vital to consider how the discussion took shape in Sweden. The Swedish mix of neutrality and an extensive welfare state, popularized as ‘the people’s home’ (folkhem), resulted in a preparedness culture permeating society.Footnote26 Despite the diverse experiences of the Second World War and even though the two countries chose different security policy paths in the late 1940s, Denmark and Sweden stayed in very close contact.

In the interwar years, propaganda had emerged as a key concept in Sweden and abroad, not only in defence circles but also in everyday life and not least in the context of advertising and PR. The Swedish conceptualization of propaganda during the Second World War was led by the governmental Board of Information (Statens Informationsstyrelse; SIS). SIS was in charge of publishing the first of a series of information leaflets entitled If war comes: Instructions for Swedish Citizens with practical information to the population about what to expect if Sweden was attacked and how to protect oneself.Footnote27 The leaflet as a medium for information to bolster resilience survived the transition from World War to Cold War, and If war comes was updated and reissued in 1952 and 1961.

Immediately after the Second World War, SIS became a target of sharp criticism, mainly due to its problematic and far-reaching wartime censorship. A different organizational structure for wartime information and preparedness was needed. For most commentators, the official policy of neutrality implied defensive countermeasures only, since psychological warfare, deception and disinformation were conceived as something that other nations were engaged in. Gradually, the formation of civil defence and total defence were discussed in relation to the new concept of psychological defence.Footnote28 In the Swedish context, psychological defence broadened the discussion from a narrow interwar delimitation on propaganda to much broader issues of possible cultural and ideological societal influence. It also served to firmly shift the focus from the propagandist/sender to the public/receiver. Furthermore, parallel to the heated discussion about SIS, academic research on military psychology grew in Sweden, predominantly influenced by the US behavioural sciences. Through key agents or strategists, this field of knowledge fed into the discourse on psychological defence in the early 1950s.Footnote29

In 1950, the government launched a commission on psychological defence, and they handed in a report in 1953 (which Dahl acquired through his close contacts with the Swedish civil defence authorities and used as the basis for his memorandum). The report defined psychological defence as attempts to maintain and strengthen the population’s resilience and gave a thorough review of European wartime operations of psychological warfare and hostile propaganda.Footnote30 The commission was tasked with making recommendations for the future, and they suggested appointing a Preparedness Board of Psychological Defence (Beredskapsnämnden för psykologiskt försvar (BN)). This became a reality in 1954, with Professor Gunnar Heckscher as the first chairman. The BN should, first, plan and organize a governmental information agency, Statens Upplysningscentral, that would become effective only when a crisis occurred or war broke out, and which would from then on lead the psychological defence. The second objective was to synthesize all knowledge about propaganda and psychological defence and to initiate research in the area.Footnote31

The early days of the BN were marked by a sense of strong and rapid media development, with which it was deemed important to keep up. They searched for ways to understand and discuss this development and to scientifically study propaganda. They found inspiration abroad; from the 1950s and onwards, this included a far-reaching quantified understanding of communication processes and a rapid import of American communication theories, including the application of such concepts as gate-keeping and the two-step flow of communication-thesis.Footnote32 The BN commissioned a series of reports about mass communication (either by their own researchers or external partners), and by the 1980s, about a third of the books in the Board’s own library dealt with this topic.Footnote33

In collaboration with the Civil Defence, the BN initiated several surveys examining public attitudes towards and knowledge about resilience and preparedness. In line with the emphasis on scientism, the surveys were conducted by trained sociologists, psychologists, and statisticians. In 1960, a survey made in Malmö demonstrated that 91% of the respondents believed it was important to acquire knowledge about self-protection, even though ‘only’ 67% confessed to being interested in the topic. Not only was civil defence and psychological defence thoroughly theorized and institutionalized, the Swedes themselves also demonstrated a remarkable embrace of the preparedness culture – particularly compared to the Danes as we shall see later. In fact, we may contend the Swedes leaned towards what we can call voluntary ‘self-conduct’, participating in exercises in large numbers and seeking out civil defence information.

It is, then, not surprising that Sweden was Denmark’s prime inspiration in matters of preparedness. Secondarily Denmark looked to Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States and, after the establishment of its Civil Defence Committee in 1952, NATO.Footnote34 But while Sweden served as a main inspiration, Denmark was not an uncritical observer. This became obvious with the advent of the thermonuclear bomb, which caused Sweden (plus the US and, in turn, NATO)Footnote35 to shift their civil protection strategy from shelters to evacuation, which greatly distressed Dahl. While evacuation was a viable option in Sweden, this was less the case in Denmark, a heavily populated but geographically small country.Footnote36 Dahl found more of a kindred spirit in the Norwegian Civil Defence Director August Tobiesen who stated that total evacuation was out of the question. Dahl estimated Denmark to be somewhere in between the Swedish and Norwegian positions.Footnote37

Information, resilience, and conduct

In the early 1950s, the Danish CDD sought various ways to inform and educate the population about civil defence, the nuclear threat and self-protection. Besides giving lectures and appearing occasionally in the media, they prepared the first post-war information leaflet for the population in 1951. One had been issued in 1944, emulating the Swedish 1943 leaflet, and this new attempt was also in tandem with the Swedish re-issuing.Footnote38 The text was redrafted several times, but it was never printed because the development of thermonuclear weapons in the mid-1950s upended the entire knowledge basis of population protection.Footnote39 Hydrogen bombs and their radioactive and political fallout raised new questions about warfare and preparedness. The means of destruction were now gigantic and the time of warning very short; consequently, authoritative information about the weapons, self-protection, and the nature of total war had simultaneously become more uncertain and more important. In the thermonuclear age, the state could not guarantee the survival of every citizen. Much therefore depended on the conduct of individuals, their resilience, morale, preparation, and education. To Dahl, the matter was now so complex and involved so many spheres of society that it exceeded the domain of civil defence: a state initiative was needed, hence Dahl’s memorandum.

The Swedish framing of information, education, and resilience as psychological defence and the connection to mass media research offered a new way of conceptualizing knowledge and public information through a scientific, systematic, and authoritative approach. Psychological defence, Dahl wrote in his memorandum while quoting the Swedish 1953 report, sought to ‘evoke, promote and consolidate’ popular resilience and the motivation and ability to resist.Footnote40 A non-resilient population risked falling prey to panic or apathy, and in consequence, surrender. To avoid this, Dahl, again referring to the Swedish original, pointed to the importance of information: ‘Quick and factual information is the best weapon against hostile propaganda and the rumours the enemy will circulate’.Footnote41

Dahl assumed an uncomplicated nexus from information to resilience: the first automatically led to the latter. It was mostly a question of finding the right timing and dosage of information to avoid unfortunate adverse effects such as panic, apathy, or ridicule.Footnote42 He emphasized the vital role of the press in this regard: A free press and in particular the radio was the link between authorities and the population. They would bring news, directives, and orders as well as comfort and entertainment, in essence, facilitate the authorities' attempts at conducting the conduct of the population. Effective information, moreover, demanded cooperation between representatives of military authorities, civil defence, press, and radio. Information was a transdisciplinary and cooperative endeavour.

Dahl spent more than half his memorandum detailing the Swedish report, the public debate it sparked and the institutionalization of psychological defence in Sweden. Whether the Swedish model was directly transferable to Denmark, Dahl did not feel confident enough to say. He believed a more modest institute would do; his main point was not the form, but that action was taken. Yet, despite the urgency of his appeal, the memorandum did not produce any immediate reaction in the relevant ministries. This political attitude would soon change, however. Not due to the evidence from Sweden but because of pressure from NATO.

The emergence of civil preparedness in NATO

Since 1952, there had been steps within NATO towards coordinating civilian functions in war, such as civil defence, infrastructure, supplies etcetera in various committees. The invention of the thermonuclear bomb and the shift to a primarily nuclear strategy also caused a re-evaluation of this. In 1955, the US proposed re-organizing and streamlining the existing ‘piecemeal and incomplete’ civilian emergency planning within NATO: instead of the many scattered committees, subcommittees and working groups, the reorganization created one Senior Committee for Civil Emergency Planning, which oversaw eleven sub-committees. The Senior Committee was endowed with the authority to do annual reviews, like those in the military area, of each country’s progress towards fulfilling the set goals. While – like the military reviews – these were not legally binding, they were the strongest tool at NATO’s disposal to compel countries to meet its demands.

The Senior Committee made a list of priorities with number 1 being ‘Maintenance of Government Control’.Footnote43 A functioning government and central administration were necessary to claim and exercise sovereignty. Government control, however, necessitated a population under control (instead of, for instance, staging protests against the government, rioting and looting). Conduct here takes on clearer connotations of control. A key part of ensuring stability was communication before as well as during a war. In peacetime, the population should be informed about how to prepare for and act in case of a war, and if war broke out the government should still be able to communicate to the population to assure the population that there was still a government, as well as to give further information on to how to conduct themselves. With NATO Secretary General Lord Ismay: ‘… governmental control will play, if there is visible evidence of its existence, a very important part in maintaining national morale in the conditions of attack which we anticipate’.Footnote44 That morale and control were intrinsically linked was clear from the following passage by the NATO Civil Defence Committee: ‘Unless the morale of the population can be maintained, it may be extremely difficult to exercise reasonable control over them’.Footnote45

As is evident from these quotes, NATO was not skittish about speaking directly about its need for conducting and controlling civilian populations. In the end, NATO could not recommend anything touching upon national (martial) law or more hands-on police-driven approaches to control the populations. They could, and did, however, recommend information programmes that would both act as conducting guidelines and, hopefully, inspire self-conduct in the citizens.Footnote46

Developing a Danish psychological defence

In late 1956, under pressure from NATO, Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen established a committee for preparedness planning that would map needs and prepare legislation. One key area, psychological defence, was delegated to a subcommittee called ‘The Committee for press preparedness etc’., nicknamed ‘The H.P. Sørensen Committee’ after its chairman (hereafter HPSC). The Prime Minister tasked the committee with the vital task of conduct: upholding the press and public authorities’ information activities upon the outbreak or under threat of war, including boosting the population’s ‘psychological resistance’. It can seem curious that the onus was specifically on governmental information activities as well as on the press, not psychological defence at large, unlike the ‘Swedish model’ that emphasized societal resilience as outlined by Dahl. However, as we shall see, psychological defence on the one hand and news and information on the other became somewhat conflated in a Danish context.

The committee consisted of newspaper editors, members of the press and government officials, as well as military officers, but not, initially, the civil defence (they were invited to join in 1957).Footnote47 It is not without irony that when, finally, psychological defence gained momentum, Dahl and the civil defence was sidelined. The government preferred to keep the sensitive topics of nuclear war and population control out of the public debate, and, relatedly, to have the HPSC, who, unlike the civil defence, was working below the public radar, take care of the information issue.

The HPSC inquired abroad for inspiration and experiences, specifically, they addressed NATO fellow members Norway, the UK, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium as well as Finland and, in particular, Sweden. The HPSC immediately invited the chairman of the Swedish BN, Professor Heckscher, to give an account of the Swedish organization.Footnote48 Heckscher visited the HPSC already at their second meeting, and in his talk, he emphasized the importance of information and news in war: ‘Communication of news during war is of special significance, because if the population does not receive news, it will fabricate them itself’.Footnote49 This lesson and many of the other themes introduced by Heckscher were adopted by the HPSC and found their way into their final report, which openly acknowledged the Swedish foundation of and heavy influence on their work.Footnote50

Symptomatically for the Danish approach, the HPSC saw no point in repeating the Swedish ‘theoretical development’ and ‘abstract argumentation’, but the beliefs that knowledge increased robustness and ignorance in turn created unrest and insecurity – fertile ground for rumours and propaganda – and that newspapers and radio were paramount in strengthening population resolve became the basic premises for the committee’s work.Footnote51 However, there was one crucial difference: while Sweden planned for a ‘more normal and drawn out state of war’, Denmark assumed a ‘chaotic’ state of affairs during war. This emanated from NATO’s planning assumptions which focused on immediate survival and holding society together for the first 30 days.Footnote52

Norway also sent the HPSC information about their work on psychological defence which was still in an early stage. A committee for State Information Services in War had been established in 1956, but its tasks were not as elaborate as the Swedish BN and mainly pertained to information services and communication of news. The HPSC secretariat noted that while the Swedes had been developing psychological defence for some years and had a fully formed organization plan with appointed personnel, the Norwegian organization was new and detailed planning did not seem to have taken place. As such, cooperation with Norway might, in fact, make more sense.Footnote53

In the end, the HPSC did not recommend a full Swedish model. Rather, it concluded that if Denmark made wartime plans for news and communication, the remaining tasks for a psychological defence organization would mainly consist of peacetime information, including monitoring public opinion and enemy propaganda. These issues, the HPSC referred to further consideration in a permanent committee. This was probably due to the workload of the HPSC, but also a lack of political clarity as to whether psychological defence proper should be prioritized. Instead, the HPSC recommended forming an information council for wartime, which would act as a contact hub between press and authorities and as an advisory agency in information questions; in essence an organization more along the Norwegian than Swedish lines.Footnote54

As for the press, the HPSC recommended an independent news service consisting of the leading Danish news agency, Ritzaus Bureau and the Danish Broadcasting Corporation Danmarks Radio.Footnote55 While ‘regular’ radio content should be independently editorialized, there would be a closer connection than usual between the radio’s leadership and the government, as the radio was the main and most direct communication tool for authorities to convey messages to – and thereby conduct – the population. Thus, the radio should have representation in government headquarters upon relocation. This constellation was also found in the Swedish model.Footnote56

The press would operate under a set of guidelines to keep the enemy from obtaining information about the war effort, informed by similar guidelines from the Second World War, but with a noteworthy difference: whereas the former guidelines had mainly banned the publishing of military information, total war significantly broadened the list of issues not to be reported on, including certain industries, construction, infrastructure, traffic, weather forecasts, trade, rationing, financial policies etcetera. Nearly all areas of society and civil life would be under some sort of publishing ban. Moreover, authorities could demand certain messages released at certain times.

However, the press would not be subject to censorship in the classical sense of pre-examination of content (which is illegal under the Danish constitution). Rather, the model was one of conduct and shared responsibility: the press organizations would co-sign the guidelines and keep discipline through self-policing. In case of uncertainty about whether a specific piece could be published or not, the proposed Information Council could offer guidance, but, in the end, responsibility resided with the editors. Should they fail to live up to the guidelines, however, authorities would have the last-resort possibility of shutting down a newspaper, issuing fines or even prison sentences.Footnote57 And, of course, laws against espionage and assisting an enemy were still in force. Yet, there is no doubt that the desired model was one in which the press was mobilized, not coerced, in support of the war effort and would willingly conduct themselves as well as assist the conduct of the population.

The HPSC report referred to the Swedish recommendation of such a model (even though Sweden could legally censor, they had also chosen the conduct method) and pointed out that while it could possibly lead to the enemy obtaining some information, forced censorship risked weakening the population’s trust in the news and hence be counter-productive for the conducting efforts of maintaining social order.Footnote58 Moreover, the committee referred to a similar model in the UK and the US during the Second World War.Footnote59

The HPSC report was submitted in December 1958, and a law on civil emergency planning for society in general was proposed in March 1959. The very first section of the law established a communication apparatus as a necessity for society’s survival but made no reference to psychological defence as such. However, in his motivational speech, Prime Minister Hansen mentioned ‘the psychological preparedness’, which he defined first and foremost as information services and activities, radio, and newspapers, ‘which will be of importance in increasing the population’s possibilities of resisting pressure’ as well as public information.Footnote60

The backbone of the proposal – and hence of Danish civil emergency planning – was the sector responsibility principle which gave each ministry responsibility for planning within its own domain. This, the Prime Minister stated, made Denmark unlike Sweden and Norway, who had gone ‘much further’ with specially constituted agencies for emergency planning, perhaps speaking to those who feared the preparedness planning would lead to a militarization of society. Tasks that did not fall naturally under a ministry or needed closer coordination, were to be referred to a separate committee with representation from relevant authorities. A (sub)committee for communication/psychological defence planning was one such task.

Curiously, while the work of the HPSC had been inspired primarily by Sweden (to which their final report also referred again and again), Norway played an equal role in the Prime Minister’s speech and the bill. There were several references to ‘Norway and Sweden’, almost as a unity, and an appendix to the bill listed existing emergency legislation aiming at (danger of) war in Denmark and Norway.Footnote61 There are at least three possible explanations, none of which are mutually exclusive. First, NATO membership and militarization were still touchy subjects in the Danish public. Following – and referring to – Norway and Sweden was a way of signalling (and probably also maintaining) an anchoring of Danish security policy in a Scandinavian context, rather than just ‘taking orders’ from NATO. Second, Norway, as a fellow NATO country operated from the same planning assumptions, which would make a Norwegian comparison of emergency legislation more relevant in practice. Third, it is possible that the shared experience of occupation a decade earlier made references to and fellowship with Norway particularly appealing to a Danish audience.

The proposal was heard in a parliamentary committee and re-submitted in October with the addition of a parliamentary committee to oversee emergency planning. All parties (except the Communists) passed the law in December 1959.Footnote62

If war comes: Public information and media preparedness

Following the passing of the law, the ‘Committee on Press Preparedness’ (Udvalget vedr. Pressens Beredskab, hereafter CPP) was established in March 1960 in accordance with the HPSC recommendations. At this point, the concept of psychological defence had all but disappeared. According to Bodil Frandsen this was due to an uneasiness with the term which chairman Jens Zeuthen, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior, claimed was tainted by associations to ‘more or less ruthless propaganda or worse’.Footnote63 Instead, the CPP concerned itself with ‘information to the public’ in peacetime as well as organizing the wartime structure of media preparedness and government information. Zeuthen stressed the importance of international knowledge transfer because Denmark itself had little experience to build on. As NATO had not done any coordinating work that could offer guidance, he suggested the CPP reached out to other countries individually. Implying the importance of alliance community for knowledge sharing, he lamented that the country that had devoted most attention to the issue, namely Sweden, ‘ … stands outside NATO’.Footnote64

The committee consisted largely of the same people as the HPSC and mostly followed its recommendations. They decided to make a leaflet containing information about the threat of nuclear war and instructions on the right behaviour during attack. This task was given priority as the leaflet should be distributed already in peacetime. In contrast to the civil defence’s failed attempts of the 1950s, there was a momentum by 1960. The key difference was the passing of the Law on Civil Preparedness, by which Denmark obligated herself to follow NATO guidelines on preparedness planning. NATO had urged its members to conduct the public through education and even made a template for an information leaflet: The NATO Self-Help Handbook.Footnote65 However, instead of copying the NATO draft, the CPP sought inspiration from the civil defence’s unpublished drafts as well as Swedish and Norwegian information leaflets from 1952 and 1957 respectively.Footnote66 The Danish leaflet was distributed to all households in January 1962.

The inspiration from the Scandinavian originals is unmistakable. The title of the Danish leaflet is identical to the Swedish: If war comes.Footnote67 The leaflets contained similar chapters on sonic warnings, evacuation, civil defence organizations and mobilization. However, the Danish leaflet was the only one to include a separate chapter on shelters like the NATO Handbook. All three Scandinavian leaflets addressed the reader directly in a solemn, patriotic, and paternalistic tone. Modern war was total, the introductions stated, warning readers that the enemy would try to cause confusion and panic through psychological warfare, hence it was vital to stay prepared and informed. They also underlined an interdependency between society and citizens: national survival depended on the preparation, resilience, and preparedness of every single individual.

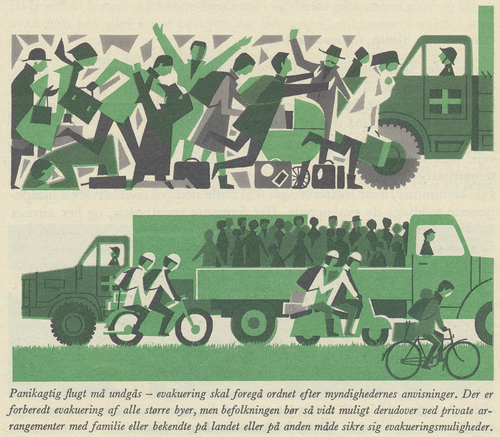

Clearly influenced by NATO’s approach to conduct and education, the Danish leaflet sought to strengthen psychological defence by giving clear instructions on the ‘right’ behaviour (according to national authorities): do not listen to foreign propaganda, stay calm, obey orders. The alternative was chaos, defeat, and surrender. This attempt to conduct the conduct of the populations is, for instance, clearly visible in the chapter on evacuation. The text read: ‘Avoid flight in panic – evacuation must take place systematically and according to the instructions of the authorities’.Footnote68 The message was driven home by two illustrations: the top one showed an unplanned, chaotic exodus: people fleeing on foot, some trampled and a military van was stuck. The lower illustration showed an orderly evacuation: people were on the road to safety by bike, motorbike and lorry, and the military van had already passed .

Caption: The leaflet’s illustrations visually assisted the message of the ‘proper’ conduct

The Norwegian and, particularly, the Swedish leaflet boldly asserted that the countries would, could and had to defend themselves and that any announcement of surrender was false. The Danish stated that such announcements would not be obeyed by the military, but it added a subordinate clause: 'unless it is certain that a legal Danish authority has given the order [to surrender or give up resistance]'. The sources do not reveal the thoughts behind the ambiguous Danish phrasing, but it is likely that the experience of the quick surrender in 1940 and three years of collaboration had an impact (in contrast, the Norwegians had fought for two months until the Germans installed a government in Oslo).

The Swedish and Norwegian leaflets contained chapters on what the population ought to do if a part of the country was occupied, including direct calls for ‘a tough passive resistance’.Footnote69 The Danish leaflet was silent on this topic. In fact, the first draft of the Danish leaflet did have a section about organized resistance as part of a chapter about the legal status of civilians during war, but this was removed in the drafting process. The legal experts of the Foreign Ministry believed a separate leaflet dedicated to the Geneva Conventions was necessary to live up to the international obligations.Footnote70

However, meeting minutes reveal other considerations. One member of the CPP believed the section could cause ‘misunderstandings’, another claimed it gave the entire leaflet a ‘dangerous twist’.Footnote71 There are two likely, supplementary though seemingly contradictory, explanations: first that the CPP wanted to avoid frightening the population as much as possible; reminding the reader about the risk of (a new) occupation would counteract this. Such cautiousness was in line with the authorities’ general approach to topics of civil defence and nuclear information,Footnote72 and the explanation is further supported by the fact that the rhetoric of the leaflet was made less dramatic as the drafting progressed.Footnote73 The second explanation is that the CPP feared the leaflet could ultimately be read as a call to sabotage and guerrilla warfare, and the Danish authorities dreaded social disorder and anarchy. Indeed, during the German occupation, the Social Democratic-led government had gone strongly against the resistance movement. In either scenario, panic or uprisings, it would undermine the conducting attempts. In line with NATO priorities, government control during war was seen as paramount. The desire to imprint on the population that they always should do what they were told – no more, no less – and leave the rest to the authorities, shines through the entire leaflet.Footnote74

The Danish leaflet is an example of mixing, hybridization, and appropriation in the field of knowledge about psychological defence that took place in a trilateral or even multilateral context. The necessary impetus to make a leaflet came from NATO, but Denmark sought inspiration from her Scandinavian neighbours. ‘To transfer is not to transport’, Espagne reminds us, and neither the HPSC nor the CPP merely transported existing models. Some elements were borrowed, adapted, and adjusted, others were left out and new ones added.

The reception of the Danish If war comes was mixed. Major newspapers were in general sympathetic whereas anti-nuclear movements rejected the premise altogether. 34% did not read the official leaflet, whereas in Sweden and Norway, only 19% and 16% respectively had disregarded their leaflets.Footnote75 Public debate in Denmark about the leaflet revealed a general aversion towards engaging with the topic at all.Footnote76 Furthermore, the Gallup poll showed that only 11% of Danish readers had changed their opinion about the possibility of survival after reading If war comes. Of these, the vast majority believed they had better chances of survival, but 16% were more pessimistic. Considering this, it is doubtful whether the leaflet was successful as a medium of conducting conduct. Certainly, the Danes showed less openness towards the attempt than their Scandinavian neighbours. However, another factor might be that while Danish authorities did not conceal that survival was not guaranteed (though chances were claimed to increase by following the leaflet’s instructions), the Swedish authorities firmly maintained the fiction that everybody could survive.Footnote77 It was, perhaps, easier to conduct a population with a promise of a happy end.

After the publication of the Danish leaflet, the CPP appeared to consider the task of informing the public – what had previously been called psychological defence – solved. Hereafter, the committee dedicated itself to finalising the media preparedness organization. This planning, as the entire civil defence and civil emergency preparedness, provided the authorities with a(n illusive) way of grasping the uncertain, but likely catastrophic future, and bringing it into a space of intervention, in short transforming it into a practical political problem. The CPP developed a decentralized structure with an information service linking the press and authorities and a news service connecting the press and the public. In this way, the press could keep the government informed about the situation and the general mood as well as convey orders, directives, and information from the government to the population, in addition to the news that made the cut through the de facto censorship guidelines as envisioned by the HPSC.Footnote78 The activation of the media preparedness should follow a three-step plan that also included evacuating to secured locations as the level of threat increased.

The CPP spent much time deliberating technical or practical planning in detail, for instance, whether to use the FM or the AM net for broadcasting news, and the amount of paper and ink to be stored in depots. In contrast, they did not initiate any theoretically based research like their Swedish counterpart. Rather, they approached the matter with pragmatism. Information, communication, and conduct was a practical and technical problem to be solved. As the HPSC had pointed out, abstract theorisation had already been made by the Swedes and could be referred to if necessary. A draft plan for media preparedness was ready in March 1965, and the final version in 1967, following the above-mentioned lines. The process of acquiring, translating, adapting, and applying knowledge of conduct and psychological defence was done; plans were ready if war came.

Conclusions

’The label psychological defence has, as we all know, never been popular here, in contrast to Sweden, where there is a directorate for psychological defence as an integral part of the Swedish total defence’.Footnote79 With these lines, Erik Schultz opened a 1978 memorandum on the peculiar career of psychological defence in Denmark. The concept of ‘psychological defence’ was simply lost in translation. Though initially adopted by actors in Denmark, it was soon replaced by a focus on rather practical public information and media preparedness. This, however, did not mean that the objective of psychological defence initiatives, public resilience and morale, was not a target of state intervention. Danish authorities were just as eager to conduct the conduct of the population as their international counterparts. However, they preferred a seemingly less centralized model, in which particularly the media was made responsible as co-conductors. The uneasiness with the term ‘psychological defence’ and its replacement with less fraught terms such as ‘information service’ and ‘media preparedness’ reveals the Danish planners’ self-understanding as more pragmatic than ideological.

In this article, we have analysed not a simple bilateral knowledge transfer but a multilateral constellation, involving nation-states and a multilateral organization. Instead of merely seeing the Swedish psychological defence as a ‘model’ or ‘centre’ from where knowledge of psychological defence was transferred 1:1 to an ‘imitator’ or ‘periphery’ (and ending up as a bleaker version), we have studied the knowledge transformation, mixing, and hybridization that involved the three Scandinavian countries, NATO and to a limited extent other Western European countries, which resulted in a Danish solution that was different from but connected to other models. It was appropriated to Danish security policy conditions, preparedness culture, and historical experiences, and in that process, the concept that had originally sparked interest, psychological defence, was shelved even if the objectives remained.

Sweden was the original inspiration but without pressure from NATO, it is uncertain if or when any attempts at forming a Danish psychological defence would have been initiated at all, and in the end, Norway seems to have been more of a model to Denmark than Sweden. Sweden had a very extensive (and expensive) psychological defence, so for practical inspiration, Denmark increasingly looked to Norway, a fellow NATO member, working with the same kind of planning assumptions and with less costly ambitions than the Swedes. In short: there could be value in looking to Sweden for ideals and to Norway for compromises. In addition, this offered the possibility of complying with NATO directives but presenting them as Norwegian, which was less controversial. Norway and Denmark, countries certain to become theatres of war if the Cold War turned hot, assumed complete chaos after a likely nuclear, possibly thermonuclear, attack, whereas Sweden planned for a prolonged, less intense war, which was possible to survive. The Swedish 1953 report spoke loftily and almost romantically about resilience and resistance, whereas the Danish and Norwegian approaches were more cynical or practical. They would create the backbone of an organization and improvise for the rest.

This difference between the Scandinavian approaches can be explained by alliance status, but another and equally important reason can be traced in the lingering experiences and memories of the Second World War. Sweden had a history of successful neutrality, and resilience was seen as a prerequisite for neutrality, which again was the basis of the revered folkhem. If the ordinary Swede was persuaded by foreign propaganda or paralysed by fear, neutrality would fail and ‘the Swedish way of life’ would cease to exist, as (the Swedish) If war comes stated. All three countries considered it likely that parts of their territory could become occupied during a future war, but Sweden had no experience to build on and was free to theorize. Denmark and Norway, in contrast, had been occupied during the Second World War, and it seems likely that this experience fed into their considerably more practical approach to the conduct of conduct in a future war. Yet, the collective memory of having fought heroically and refused collaboration was likely reflected in the Norwegian leaflet’s bold call to arms that resembled the Swedish approach more than the pragmatic cautiousness expressed in the Danish leaflet.

The methodological internationalism advocated by this article has brought new perspectives to the field of civil and psychological defence history and has made us rethink some elements of our previous works. For instance, reading the leaflets through the lens of methodological internationalism highlights how the Danish approach acknowledged surrender as an option and avoided any mention of resistance during an occupation. Existing studies of the Danish leaflet, incl. our own, have missed this point.Footnote80 With very few exceptions, this history has primarily been studied within a national state-centred framework. With the nation-state as the ultimate conductor, this is neither futile nor irrelevant. However, the nation-state does not exist in a vacuum, and as we have shown here, while an effort might emanate from the state, it can be informed, inspired, or even imposed by outside actors, while still being negotiated into its own specific setting. In the same vein it is worth noticing that while the efforts originated with official authorities such as government and civil defence, it was a constant ambition to mobilize the press and population as co-conductors of themselves and their fellow citizens. Crucially this was to be consensual and mutually acceptable, it was not forced upon the population even if, of course, it was obviously an unequal power relation. The efforts of the authorities testify to a strong wish for not just a policy but a culture of conduct permeating all of society. After all, this was considered a necessity for morale, resilience and, ultimately, survival in the nuclear age.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank prof. Johan Östling, Lund University, for his insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of SJH for their inspirational suggestions. This article is the result of research projects funded by the Crafoord Foundation (grant 20210610) and the Swedish Research Council (grant 2019–02664).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rosanna Farbøl

Rosanna Farbøl is an Assistant Professor in History, School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, and affiliated researcher at Department of Communication and Media, Lund University. Her main research interests are Cold War history, civil defence and nuclear culture, and her latest publications include “Prepare or resist? Cold War Civil Defence and Imaginaries of Nuclear War in Britain and Denmark in the 1980s”, Journal of Contemporary History 57, no. 1 (2022): 136–158.

Iben Bjørnsson

Iben Bjørnsson is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Strategy and War Studies, the Royal Danish Defence College. Her main research interests are Cold War history, emergency preparedness planning and International Relations. Her latest publications include “Negotiating Armageddon. Civil defence in NATO and Denmark 1949–59”, Cold War History 23, no. 2 (2023): 217–38

Marie Cronqvist

Marie Cronqvist is a Professor of Modern History, Department of Culture and Society, Linköping University, and an Associate Professor in Journalism and Media History, Department of Communication and Media, Lund University. Her main research interests are media history, cultural history, and the history of sound. Her latest publications include ‘Between Scripts: Radio Berlin International (RBI) and its Swedish Audience in November 1989’ in Remapping Cold War Media: Institutions, Infrastructures, Translations, edited by A. Lovejoy & M. Pajala, 139–154. Indiana University Press, 2022.

Notes

1. Memorandum, 23 Dec. 1954, The Danish National Archives (henceforth DNA), Beredskabsstyrelsen, Civilforsvarsdirektør E. Schultz’ embedsarkiv (henceforth BES), box 186, “Memorandum vedrørende psykologisk forsvar”.

2. Borring Olesen, “Scandinavian Security Alignments,” 191–2.

3. Runge Olesen, “To Balance,” 84–91.

4. Villaume, Allieret med forbehold, ch. 6 and 7; Villaume and Borring Olesen, I blokopdelingens tegn, 179ff, 301ff; Tamnes, “Integration and Screening,” 59–100.

5. Frandsen, “Hvis krigen kommer,” 68–9.

6. Lakoff, “Preparing for the next emergency,” 247–8; Collier, Lakoff and Rabinow, “Biosecurity,” 3–7.

7. Rose, One Nation Underground; Oakes, The Imaginary War; McEnaney, Civil Defense; Masco, ““Survival is your business”,” 361–98; Grant, After the Bomb; Burtch, Give Me Shelter.

8. Cronqvist, “Evacuation as welfare ritual”; Cronqvist, “Survival in the welfare cocoon”.

9. See for example Sylvest, “Pre-enacting the next war”; Sylvest, “Atomfrygten og civilforsvaret”; Bjørnsson, ““Stands tilløb til panik””; Bjørnsson, “Negotiating Armageddon”; Farbøl, “Prepare or resist?”; Farbøl, “Urban civil defence”; Farbøl, “Ruins of resilience”.

10. Sørlie, “At alle deler”; Rønne, “Hver på sin”.

11. See for example Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?; Hixson, Parting the Curtain; Osgood, Total Cold War; Bastiansen, Klimke, and Werenskjold, Media and the Cold War. For a discussion about the concept and history of propaganda, see Wimberley, How Propaganda became Public Relations.

12. Nietzel, Die Massen lenken; Glander, Origins of Mass Communication Research; Simpson, Science of Coercion.

13. (Accessed August 10, 2023) https://www.mpf.se/en/.

14. Rossbach, Fighting Propaganda; Cronqvist, “Mediekunskaper och propagandaanalyser”; Jakobsson and Stiernstedt, “Swedish Media Research”.

15. Sylvest, “Atomfrygten og civilforsvaret”; Bjørnsson, ““Stands tilløb til panik””; Bjørnsson, Farbøl, and Sylvest, “Hvis krigen kommer”; Farbøl and Sylvest, “Sensitive information”; Rostgaard and Christensen, “Modernitet”; Høj, Stokbro and Noe, “Tryghed på tryk”.

16. Frandsen, “Hvis krigen kommer”. However, a Master Thesis examines Cold War planning for the press, see Høj, Stokbro, and Noe, “Tryghed på tryk”.

17. Middell and Roura, Transnational Challenges; Paisley and Scully, Writing Transnational History; Iriye and Saunier, The Palgrave Dictionary. See also Werner and Zimmermann, “Beyond Comparison”; Iriye, “Internationalizing International History”; Hogan, “The “Next Big Thing””; Clavin, “Defining transnationalism”; Thelen, “The Nation and Beyond”. On the concept of “methodological nationalism,” see Wimmer and Glick Schiller, “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond”. For discussions within the field of media history, see Cronqvist and Hilgert, ‘Entangled Media Histories’.

18. Espagne, “Comparison and transfer,” 43.

19. This understanding has its roots in the definition of transnationalism in the classic but not uncontested study by Nye and Keohane, who used the concept to denote contracts, coalitions, and interactions across state boundaries, when at least one of the members of a transnational relationship represented a non-governmental organization, see Keohane and Nye, Transnational Relations and World Politics. This definition as well as the separation between transnational history and international history can also be found in later champions of transnational and international history as Clavin, “Defining transnationalism’ and Iriye, “‘Internationalizing International History”.

20. Espagne, “Comparison and transfer,”, 42.

21. Östling et al., Circulation of knowledge; Secord, “Knowledge in transit”.

22. Black and Mak, “Period, theme event,” 20.

23. Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” 777–95. We were inspired to use this approach by Wimberley, How Propaganda became Public Relations.

24. Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” 789.

25. Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” 789; McCall, “Conduct,” 68.

26. Cronqvist, “Survival in the welfare cocoon”; Cronqvist, “Det befästa folkhemmet”; Cronqvist, “Utrymning i folkhemmet”.

27. Cronqvist, “Survival in the welfare cocoon,” 192.

28. Rossbach, Fighting Propaganda.

29. Bennesved and Cronqvist, “En humanistiskt skolad kunskapsstrateg”

30. SOU 1953:27: Psykologiskt försvar.

31. Cronqvist, “Mediekunskaper och propagandaanalyser,” 81.

32. Cronqvist, “Mediekunskaper och propagandaanalyser,” 78–9.

33. Jakobsson and Stiernstedt, “Swedish Media Research,” 135.

34. References were constantly made to what was done in Sweden, then Norway, then other NATO countries at meetings of the Danish Civil Defence Board. DNA, Beredskabsstyrelsen: Civilforsvarsrådets møder 1950–77, box 1–2.

35. On the Danish attitude to the shelter/evacuation discussion and NATO guidelines, see Bjørnsson, “Negotiating Armageddon”.

36. Report from trip to Sweden by Arthur Dahl, 14 May 1955, DNA, BES, box 132.

37. Ibid.

38. Report, Oct. 1953, DNA, BES, box 185, “Status for Civilforsvaret pr. september 1953”. For recruitment purposes, the film medium was seen as particularly useful, and Civil Defence made a couple of films as well as borrowed and adapted Swedish films to demonstrate the capabilities of civil defence, see Sylvest and Bennesved, “Embedding Preparedness, Assigning Responsibility,” 103–29; Bjørnsson ““Stands tilløb til panik””.

39. Sylvest “Atomfrygten og civilforsvaret,” 29.

40. Memorandum, 23 Dec. 1954, DNA, BES, box 186, “Memorandum vedrørende psykologisk forsvar,” 2–3.

41. Ibid., 3.

42. Farbøl and Sylvest, “Sensitive Information”.

43. Bjørnsson, “Order on Their Home Fronts,” 25–52; Resolution, 10 Nov. 1955, NATO Archives Online (henceforth NAO) CM(55)100, “Resolution on the Establishment of a Senior Civil Emergency Planning Committee”; Survey, 21 Dec. 1955, NAO, AC/98-D/1 “General Survey of the Present Civil Emergency Planning Structure … “; Memorandum, 20. Aug. 1955, NAO, C-M(55)75: “United States Proposal for Reorganization of the NATO Civil Emergency Planning Committee Structure”.

44. Note, 30 Dec. 1955, NAO, AC/98-D/4, “Senior civil emergency planning committee. Maintenance of Governmental Control”.

45. Memorandum, 6 Sep. 1956, NAO, “Civil Defence Committee. Control of civilian population under attack,” AC/23(CD)-D/151.

46. Bjørnsson, ““Stands tilløb til panik”,” 85–6.

47. Letters from H.C. Hansen to H.P. Sørensen, 20 and 21 Dec. 1956, Labour Movement’s Library and Archive (Arbejderbevægelsens bibliotek og arkiv, henceforth ABA), Regeringsudvalget for civilt beredskab (henceforth RCB) box 1; Report, Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 1–4.

48. Letter from Toft-Nielsen, 23 Jan. 1957, ABA, RCB, box, 1, 2) Forsk korrespondance; H.P Sørensen’s speech, 18 Jan. 1957 and minutes, 27 Feb. 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 3) Referater, “Første møde” and “Referat af udvalgets møde onsdag den 27. februar 1957 i folketingets udvalgsværelse 2”.

49. This and all other quotes in the article are translated by the authors. Emphasis in original. Meeting minutes ABA, RCB, box 1, 3) Referater, “Referat af udvalgets møde onsdag den 27. februar 1957 i folketingets udvalgsværelse,” 2.

50. Memorandum, 5 July 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 6) Udvalg 1 Forh m myndigheder, “Det psykologiske forsvar”; Report, Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 5.

51. Draft, 3 May 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 6) Udvalg 1 Forh m myndigheder, “Pressens forhold til myndighederne under krig”.

52. Minutes, 1 Mar. and 10 Apr. 1957 and ABA, RCB, box 1, 3) Referater, “Referat af udvalgets tredje møde fredag den 1. marts 1957 i mødesalen, ministeriet for offentlige arbejder” and “Referat af udvalg I’s første møde onsdag den 10. april 1957 kl. 10 i mødelokalet, regeringsudvalget for civilt beredskab”; Draft, 3 May 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 6) Udvalg 1 Forh m myndigheder, “Pressens forhold til myndighederne under krig”.

53. Letter from Toft-Nielsen, 18 Feb. 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 2) Forsk korrespondance; Draft, 3 May 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 6) Udvalg 1 Forh m myndigheder, “Pressens forhold til myndighederne under krig”.

54. Memorandum, 5 July 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 6) Udvalg 1 Forh m myndigheder, “Det psykologiske forsvar”; Report Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box, 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 65–67.

55. Report Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “etænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 14ff.

56. Draft, Apr. 1957, ABA, RCB, box 2, Udvalg III Radioen, “Bemærkninger vedrørende radioens særlige forhold”.; Report, Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 68ff.

57. Report, Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” 40ff. On the Second World War, see appendix A.

58. ibid., 31–34; Meeting minutes, ABA, RCB, box 1, 3) Referater, “Referat af udvalgets møde onsdag den 27. februar 1957 i folketingets udvalgsværelse 2”.

59. Memorandum, 22 Jan. 1957, ABA, RCB, box 1, 3) Referater, “Det norske beredskabsnævn for statens informationstjeneste i krig”; Memorandum in copy, ABA, RCB, box 1, 5) Forsk tilsendt materiale, “Statens informasjonstjeneste i krig”; Report, Dec. 1958, ABA, RCB, box 2, “Betænkning fra Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab m.v.,” appendix B.

60. Copy of the Prime Minister’s presentation of a bill on civil emergency planning, 11 Mar. 1959, ABA, RCB, box 1, 2) Forsk korrespondance, “Statministerens forelæggelsestale til forslag til lov om det civile beredskab”.

61. Bill on civil emergency planning and the Prime Minister’s presentation of the bill, 11 Mar. 1959, ABA, RCB, box 1, 2) Forsk korrespondance, “Forslag til Lov om det civile beredskab’ and ‘Statministerens forelæggelsestale til forslag til lov om det civile beredskab”.

62. Folketingstidende 1958–59 (vol. 110), sp. 4022–4046, https://www.folketingstidende.dk/ebog/19581F?s=; Folketingstidende 1959–60 (vol. 111), sp. 29–30, 77–80, 1849–50, 2030–1, Accessed April 28, 2023 https://www.folketingstidende.dk/ebog/19581F?s=#.

63. Quoted in Frandsen, “Hvis krigen kommer,” 189.

64. Note, May 1960, DNA, BES, box 112, “Notat som grundlag for diskussion om udvalgets arbejde,” 5.

65. Leaflet, 1961, DNA BES, box 112 “NATO Self Help Handbook”; Note, Civil Defence Committee, Working Party on Publicity and Public Relations, NAO, AC/23(CD/PU)D/3, “Note by the Chairman”; Agenda, 30 June 1961, DNA, BES, box 112, “Dagsorden for udvalgets 3. møde fredag den 30. juni 1961 kl. 10.00”.

66. Letter to Erik Schultz from Toft-Nielsen, 29 July 1960, DNA, BES, box 112. The Norwegian and Swedish leaflets were revised and reissued in late 1961, but this was too late for them to have an impact on the work with the Danish 1962 leaflet. The comparison here is made on the basis of the 1950s editions.

67. Om kriget kommer in Swedish, Hvis krigen kommer in Danish, and Hvis det skulle bli krig (If war should happen) in Norwegian.

68. Statsministeriet, Hvis krigen kommer, 23.

69. Civilförsvarsstyrelsen, Om kriget kommer, 23; Beredskapsnemnda for Statens informasjonstjeneste i krig, Hvis det skulle bli krig, 39.

70. Noe, Stokbro, and Høj, “Tryghed på tryk,” 120.

71. Summary, Apr. 1961, DNA, BES, box 112, Presseberedskabsudvalget, “Foreløbigt referat af udvalgets 2. møde, torsdag d. 6. April 1961,” 2.

72. Farbøl and Sylvest, “Sensitive Information”.

73. Noe, Stokbro and Høj, “Tryghed på tryk,” 180–2 as well as Bærholm and Lorenzen, “Hvis krigen kommer,” 167–9.

74. Bjørnsson, Farbøl, and Sylvest, “Hvis krigen kommer,” 42; Bjørnsson, “Order on their home front”; Kirchhoff, ““Vor eksistenskamp”,” 13–63.

75. Article, DNA, BES, box 112, “den norske befolkning er positivt innstilt overfor Sivilforsvarets opplysningsvirksomhet,” 183; Document, DNA, BES, box 112, Udvalget vedr. pressens beredskab ”‘Bilag til skrivelse af 7. Maj 1962,” 1.

76. Rostgaard, “Kan man overleve,” 164.

77. Ibid., 164.

78. For more detail about this organization, see Noe, Stokbro, and Høj, “Tryghed på tryk,” 129–68.

79. Document by Erik Schultz, 5 Jan. 1978, DNA, BES, box 112, “Vedr. psykologisk forsvar,” 1.

80. Bjørnsson, Farbøl and Sylvest, “Hvis krigen kommer”; Bærholm and Lorentzen, “Hvis krigen kommer”; Sylvest, ”Civilforsvaret”; Noe, Stokbro, and Høj, “Tryghed på tryk”.

References

- Bærholm, Anders Kristian, and Jakob K.B. Lorenzen. “Hvis krigen kommer - historien om en pjece fra den kolde krig.” In Den kolde krig på hjemmefronten, edited by Klaus Petersen and Nils Arne Sørensen, 167–182. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2004.

- Bastiansen, Henrik G., Martin Klimke, and Rolf Werenskjold, eds. Media and the Cold War in the 1980s: Between Star Wars and Glasnost. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

- Bennesved, Peter, and Marie Cronqvist. “En humanistiskt skolad kunskapsstrateg på ett samhällsvetenskapligt fält: Torsten Husén och framväxten av ett svenskt psykologiskt försvar.” In Humaniora i välfärdssamhället: Kunskapshistorier om efterkrigstiden, edited by Johan Östling, Anton Jansson, and Ragni Svensson Stringberg, 241–265. Stockholm & Göteborg: Makadam, 2023.

- Beredskapsnemnda for Statens informasjonstjeneste i krig. Hvis det skulle bli krig: Veiledning for befolkningen. Oslo, 1957.

- Bjørnsson, Iben. “Stands tilløb til panik: Civilforsvarspjecer som social kontrol.” In Atomangst og civilt beredskab: Forestillinger om atomkrig i Danmark 1945–1975, edited by Marianne Rostgaard and Morten Pedersen, 65–103. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press, 2020.

- Bjørnsson, Iben. “Order on Their Home Fronts: Imagining War and Social Control in 1950s NATO.” In Cold War Civil Defence in Western Europe: Sociotechnical Imaginaries of Survival and Preparedness, edited by Marie Cronqvist, Rosanna Farbøl, and Casper Sylvest, 25–52. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

- Bjørnsson, Iben. “Negotiating Armageddon. Civil Defence in NATO and Denmark 1949–59.” Cold War History 23, no. 2 (2023): 217–238. doi:10.1080/14682745.2022.2123915.

- Bjørnsson, Iben, Rosanna Farbøl, and Casper Sylvest. “Hvis krigen kommer: Forestillinger om fremtiden.” Kulturstudier, no. 1 (2020): 33–61.

- Black, Alistair, and Bonnie Mak. “Period, Theme Event: Locating Information History in History.” In Information and Power in History. Towards a Global Approach, edited by Ida Nijenhuis, Marijke van Faassen, Ronald Sluijter, Joris Gijsenbergh, and Wim de Jong, 18–36. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

- Borring Olesen, Thorsten. “Scandinavian Security Alignments 1948–1949 in the DBPO Mirror.” Scandinavian Journal of History 37, no. 2 (2012): 185–197. doi:10.1080/03468755.2012.666719.

- Burtch, Andrew. Give Me Shelter: The Failure of Canada’s Cold War Civil Defence. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

- Civilförsvarsstyrelsen. Om kriget kommer: Vägledning för Sveriges medborgare. Stockholm, 1952.

- Clavin, Patricia. “Defining Transnationalism.” Contemporary European History 14, no. 4 (2005): 421–439. doi:10.1017/S0960777305002705.

- Collier, Stephen J., Andrew Lakoff, and Paul Rabinow. “Biosecurity: Towards an Anthropology of the Contemporary.” Anthropology Today 20, no. 5 (2004): 3–7. doi:10.1111/j.0268-540X.2004.00292.x.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Utrymning i folkhemmet: Kalla kriget, välfärdsidyllen och den svenska civilförsvarskulturen 1961.” Historisk tidskrift, no. 3 (2008): 451–476.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Det befästa folkhemmet: Kallt krig och varm välfärd i svensk civilförsvarskultur.” In Fred i realpolitikens skugga, edited by Magnus Jerneck, 169–197. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2009.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Survival in the Welfare Cocoon: The Culture of Civil Defence in Cold War Sweden.” In Cold War Cultures: Perspectives on Eastern and Western European Societies, edited by Thomas Lindenberger, Marcus M. Payk, and Annette Vowinckel, 191–210. New York: Berghahn, 2012.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Evacuation as Welfare Ritual: Cold War Media and the Swedish Culture of Civil Defence.” In Nordic Cold War Cultures: Ideological Promotion, Public Reception, and East-West Interactions, edited by Valur Ingimundarson and Rosa Magnusdottir, 75–95. Helsinki: Aleksanteri Institute, 2015.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Mediekunskaper och propagandaanalyser: Beredskapsnämnden för psykologiskt försvar och PROPAN-projektet, 1970–1974.” In Efterkrigstidens samhällskontakter, edited by Fredrik Norén and Emil Stjernholm, 73–99. Lund: Fredrik Norén and Emil Stjernholm, 2019.

- Cronqvist, Marie, and Christoph Hilgert. “Entangled Media Histories: The Value of Transnational and Transmedial Approaches in Media Historiography.” Media History 23, no. 1 (2017): 130–141. doi:10.1080/13688804.2016.1270745.

- Espagne, Michel. “Comparison and Transfer: A Question of Method.” In Transnational Challenges to National History Writing, edited by Matthias Middell and Lluís Roura, 36–53. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Farbøl, Rosanna. “Urban Civil Defence: Imagining, Constructing and Performing Nuclear War in Aarhus.” Urban History 48, no. 4 (2021): 701–723. doi:10.1017/S0963926820000590.

- Farbøl, Rosanna. “Ruins of Resilience: Imaginaries and Materiality Imagineered and Embedded in Civil Defence Architecture.” In Cold War Civil Defence in Western Europe. Sociotechnical Imaginaries of Preparedness and Survival, edited by Marie Cronqvist, Rosanna Farbøl, and Casper Sylvest, 157–183. Cham: Palgrave, 2022a.

- Farbøl, Rosanna. “Prepare or Resist? Cold War Civil Defence and Imaginaries of Nuclear War in Britain and Denmark in the 1980s.” Journal of Contemporary History 57, no. 1 (2022b): 136–158. doi:10.1177/00220094211031996.

- Farbøl, Rosanna, and Casper Sylvest. “Sensitive Information: Knowing and Preparing for Nuclear War during the Cold War.” In Routledge Handbook of Information History, edited by Toni Weller, Alistair Black, Bonnie Mak, and Laura Skouvig. Abingdon on Thames: Routledge, Forthcoming.

- Foucault, Michel. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 4 (1982): 777–795. doi:10.1086/448181.

- Frandsen, Bodil. “Hvis krigen kommer: En undersøgelse af det centrale civile beredskab og REGAN Vest under den kolde krig (1950–1968).” PhD diss., Aalborg University, 2021.

- Glander, Timothy. Origins of Mass Communication Research during the American Cold War: Educational Effects and Contemporary Implications. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Grant, Matthew. After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Britain, 1945–1968. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Hixson, Walter L. Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture and the Cold War 1945–1961. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1997.

- Hogan, Michael J. “The ‘Next Big Thing’: The Future of Diplomatic History in a Global Age.” Diplomatic History 28, no. 1 (2004): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2004.00396.x.

- Høj, Tobias, J. Andreas, L. Stokbro, and R. Noe Bjarke. “Tryghed på tryk: Det danske presseberedskab under Den Kolde Krig.” MA thesis, Aalborg University, 2017.

- Iriye, Akira. “Internationalizing International History.” In Rethinking American History in a Global Age, edited by Thomas Bender, 47–62. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Iriye, Akira, and Pierre-Yves Saunier, eds. The Palgrave Dictionary of Transnational History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Jakobsson, Peter, and Fredrik Stiernstedt. “Swedish Media Research in the Service of Psychological Defence during the Cold War?” Nordicom: Nordic Journal of Media Studies, no. 2 (2020): 133–144.

- Keohane, Robert, and Joseph Nye, eds. Transnational Relations and World Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- Kirchhoff, Hans. ““Vor eksistenskamp er identisk med nationens kamp” – Om Socialdemokratiets overlevelsesstrategi under besættelsen.” In Årbog for Arbejderbevægelsens Historie, 13–63. København: SFAH, 1994.

- Lakoff, George. “Preparing for the Next Emergency.” Public Culture 19, no. 2 (2007): 247–271. doi:10.1215/08992363-2006-035.

- Masco, Joseph. “‘Survival Is Your Business’: Engineering Ruins and Affect in Nuclear America.” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 2 (2008): 361–398. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2008.00012.x.

- McCall, Corey. “Conduct.” In The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon, edited by Leonard Lawlor and John Nale, 68–74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- McEnaney, Laura. Civil Defense Begins at Home. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Middell, Matthias, and Lluís Roura, eds. Transnational Challenges to National History Writing. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Nietzel, Benno. Die Massen lenken: Propaganda, Experten und Kommunikationsforschung im Zeitalter der Extreme. Oldenbourg: de Gruyter, 2023.

- Oakes, Guy. The Imaginary War: Civil Defense and American Cold War Culture. New York, NY: New York University Press, 1994.

- Osgood, Kenneth. Total Cold War: Eisenhower’s Secret Propaganda Battle at Home and Abroad. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

- Östling, Johan, Erling Sandmo, David Larsson Heidenblad, Anna Nilsson Hammar, and Kari Nordberg, eds. Circulation of Knowledge: Explorations in the History of Knowledge. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2018.

- Paisley, Fiona, and Pamela Scully. Writing Transnational History. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

- Rønne, Helle Kristiane. “Hver på sin tue: totalforsvaret 1955–1970.” MA diss., University of Oslo, 2004.

- Rose, Kenneth. One Nation Underground: The Fallout Shelter in American Culture. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2001.

- Rossbach, Niklas. Fighting Propaganda: The Swedish Experience of Psychological Warfare and Sweden’s Psychological Defence, 1940–1960. Stockholm: Axess Publishing AB, 2017.