ABSTRACT

This paper examines the specificities of interpersonal credit networks in both a rural and an urban setting in pre-industrial Finland. To analyse peer-to-peer lending, the article studies a sample of 1047 probate inventories from the town of Kristinestad and its surrounding rural area, the parish of Lappfjärd. These probate inventories feature more than 5000 credit relations between households for the period 1850–1855 and 1905–1914. This paper also concerns itself with the changes pertaining to the advent of banking institutions in the mid-nineteenth century. Traditional behavioural sciences argue that formal institutions replaced informal ones because they are more efficient, more inclusive, or both. No longer needed, informal institutions are supposed to have disappeared when formal ones emerged. But this argument does not consider the social context – or embeddedness, a term coined by Granovetter – and the individuals evolving in it. Embeddedness does not disappear. Therefore, one may ask how banks penetrated communities and the credit networks that were already in place in order to supplant private lending. Tools from social network analysis help to draw insights into the features and changes pertaining to credit networks.

Contemporary markets lean on formal institutions to ensure their functioning. Regulations and legal norms define the rule of the game. As a result, formal institutions facilitating economic transactions offer, in theory, a protective and efficient framework to agents. In general, these formal institutions are reputed to be superior to informal institutions because they are more inclusive and more efficient (Fafchamps, Citation2017; Greif, Citation2002; North, Citation1990; Platteau, Citation1994). This is the case for modern banking institutions. Today, the main function of western commercial banks is – supposedly – to facilitate the allocation and deployment of financial resources between savers and users of capital in a manner that efficiently assesses and transfers risks (Patalano & Roulet, Citation2020, p. 14). As such, they stand in stark contrast with the so-called ‘informal’ economy or ‘informal banking’ which precluded the existence of formal institutions in the Western world.

Before the advent of banks, the allocation and deployment of financial funds was mainly ensured by private lenders. Throughout Europe, women and men borrowed and lent from each other, often at the local level, in tight-knit networks (see for instance Dermineur, Citation2018; Hoffman, Postel-Vinay, & Rosenthal, Citation2001; Lindgren, Citation2002; Muldrew, Citation1998; Padgett & Mclean, Citation2011). Households financed investments in real estate, land, livestock, shop stocks or even international trade via the allocation of capital from their peers. They also made ends meet, paid their taxes and fed their families via differed payments and small loans from family members, friends and neighbours. The degree of risk transfer, the availability of capital and the terms of the agreement were often tailored according to the needs, capabilities and expectations of the parties (Fontaine, Citation2008; Muldrew, Citation1998). These features also varied depending on the circuit of credit and the type of contractual agreement the parties choose. In the absence of banks, a wide range of credit channels existed. The majority of households were not constrained to seek capital from one unique source or one unique interlocutor. The existing constellation of credit providers offered parties flexibility and choice (Dermineur, Citation2018). Furthermore, credit, either certified by written evidence or verbal agreement, originated in social and economic interactions, and negotiations between lenders and borrowers. Economic activity, and in particular credit exchanges, were not disembedded from society (Granovetter, Citation1985; Polanyi, Citation2001). All economic behaviour in market societies is rooted in socialised networks. Repeated exchanges forged familiarity among lenders and borrowers leading to tight relations, creating quasi-kinship (Semin, Citation2007). As a result, most exchanges were mutually beneficial transactions featuring a high degree of fairness, cooperation, solidarity and flexibility. The pre-industrial market can thus be characterised as a ‘community of advantage’ (Sugden, Citation2018).

The concept of the informal economy was coined in the 1970s by the anthropologist Keith Hart who opposed a formal and regulated economy with what he called an ‘informal economy’. What he observed then in Ghana was an economy in which small-scale transactions took place outside the legal framework and the scope of the authorities and its institutions, unregulated by law, often illegal, and not subsidised (Guirkinger, Citation2008; Hart, Citation1973, Citation1985). The notion of the informal economy was thus framed in opposition to the existence of strong regulatory institutions. As these institutions were embryonic in pre-industrial Finland, where the present study is situated, I therefore refrain from using the term ‘informal’. Instead, I prefer the term semi-regulated or non-intermediated to designate peer-to-peer credit markets (Dermineur, Citation2019).

In pre-industrial Finland, these networks of non-intermediated credit dominated the financial exchanges at least until the eve of World War I. Yet, we still know little about the size and characteristics of these markets (see for instance Aunola, Citation1967; Markkanen, Citation1973; and more recently Hemminki, Citation2012, Citation2014; Hemminki & Hemminki, Citation2016; Turunen, Citation2019). One common assumption is that peer-to-peer credit markets were of insignificant size and played a negligible role in economic growth before the advent of commercial banking. This view has now been challenged. Rural and urban inhabitants of Finland turned to credit markets to bridge the lack of cash in circulation (Pipping, Citation1961; Kuusterä & Tarkka, Citation2011; Voutilainen, Turunen, & Ojala, Citation2020, p. 124). Peer-to-peer transactions were also of importance for households and local communities. Recently, Tiina Hemminki has compared two rural communities on each side of the Gulf of Bothnia between 1796 and 1830. There, in Swedish Nordmaling and in Finnish Ilmajoki, peer-to-peer exchanges were dynamic and of significant size well before the advent of commercial banks (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 144). Similarly, in her exploration of urban households’ bankruptcy in the nineteenth century, Riina Turunen found that an increase of credit supply via a greater institutionalisation of credit after 1860 led to greater indebtedness (Turunen, Citation2017a, p. 276). In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Finnish economy started to lift, saving and commercial banks slowly emerged (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996). At the turn of the century, these began progressively to offer their services to households. However, we still know little regarding the transition between the traditional peer-to-peer credit markets and the switch to banking services (Lindgren, Citation2002).

We do know that modern banking struggled to replace traditional interpersonal transactions and the switch occurred extremely slowly (Lindgren, Citation2002, Citation2017). In France, Great Britain, Sweden and even the United States, peer-to-peer lending continued to defy the modern financial sector at the turn of the twentieth century. There, in 1900, between 32% and 65% of mortgage lending was still being done by various sorts of traditional intermediaries, outside the scope of banking institutions (Hoffman, Postel-Vinay, & Rosenthal, Citation2019, p. 18). Interpersonal lending resisted the rise of commercial joint-stock banking up until the mid-twentieth century.

This article is concerned with this transition between non-intermediated transactions and intermediated ones, giving particular attention to the transition from peer-to-peer lending to bank lending. How did people lend and borrow money before the advent of banks? And how did the transition to banks take place? The aim of this paper is thus threefold. First, it offers a reconstruction of non-intermediated credit network structures with special reference to the characteristics and specificities of claims and liabilities. Scholars have long emphasised the specificities of private lending before the advent of banks, showing the dynamism of such markets (Dermineur, Citation2018; Hoffman et al., Citation2001; Muldrew, Citation1998). In Northern Europe, historians have uncovered non-intermediated lending, offering a scattered picture (Hemminki, Citation2014; Lindgren, Citation2002; Perlinge, Citation2005). In Finland, in particular, scholars have focused especially on indebtedness (Aunola, Citation1967; Frigren, Hemminki, & Nummela, Citation2017; Kaarniranta, Citation2001; Markkanen, Citation1973; Turunen, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Currently, a comprehensive overview of the size and functioning of the non-bank segments is missing. This paper aims to contribute to a better understanding of these markets. Second, this paper compares an interconnected rural and urban area, namely the town of Kristinestad, and its rural hinterlands, the parish of Lappfjärd (Lapväärtti in Finnish). It shows not only the ties between the city and the countryside but also the discrepancies and similarities between a rural and an urban credit market. Finally, this study examines the evolution of peer-to-peer lending over time and pays special attention to the transition from non-intermediated exchanges to banking transactions. In the 1850s, most transactions consisted in promissory notes and deferred payments. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, these types of loan were slowly being supplanted by transactions with commercial and savings banks, either in the form of loans or deposits. The analysis focuses especially on the penetration and diffusion of banking institutions into the peer-to-peer lending network (see the recent work of Broberg & Ögren, Citation2019). In theory, no longer needed, informal institutions are supposed to have disappeared when formal ones emerged (North, Citation1990). But this argument does not consider the social context – or embeddedness, a term coined by Granovetter – and the individuals evolving in it (Granovetter, Citation1985). Embeddedness does not disappear. Therefore, one may ask how banks penetrated communities and the credit networks that were already in place: what changed with the advent of banks, with special reference to peer-to-peer lending? Tools from social network analysis will help to draw insights into the features and changes pertaining to credit networks.

To answer the questions above, the paper is divided into three sections. First, it focuses on the general characteristics of the Finnish economy in the period considered with special reference to capital markets. Then, it turns to the analysis of the peer-to-peer lending market. To conduct the analysis, this paper draws on a sample of over 1000 probate inventories from the western coastal town of Kristinestad and its rural hinterland from 1850 to 1914.

In the absence of brokers, such as notaries, probate inventories prove to be a useful and rich resource (Lindgren, Citation2002; Markkanen, Citation1978a; Holderness, Citation1975; Kuuse, Citation1974). Finally, the paper analyzes the penetration of banks into the peer-to-peer financial market.

I. Main characteristics of the pre-industrial Finnish economy

In Europe, and in Finland in particular, viable financial markets and networks, i.e peer-to-peer lending, existed long before the emergence of modern banking institutions in the mid-nineteenth century. These financial exchanges were sustained through strong norms of collaboration, fairness, and solidarity; traditional features of moral economies. Finland before the mid-nineteenth century -in terms of credit exchange- did not differ much from other Western countries. Nearly 90% of the transactions in early modern England were carried out on credit because a chronic shortage of money as a medium of exchange made credit crucial in daily transactions (Muldrew, Citation1998). We do not have an exact estimate for the monetisation rate in nineteenth-century Finland, but the proportion might have been close or even superior to the British amount (Kuusterä & Tarkka, Citation2011; Voutilainen et al., Citation2020). Barter, trade and subsistence farming persevered throughout the nineteenth century. And taxes could even be paid in kind, at least at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It is safe to argue that most of the Finnish credit transactions in the nineteenth century took place between private individuals (Hemminki, Citation2014).

In pre-industrial Finland, the authorities did not provide an infrastructure for the conclusion of these peer-to-peer contracts. In the absence of public brokers – such as notaries –, intermediation remained the business of private individuals (Ågren, Citation2018; Hemminki, Citation2014; Lindgren, Citation2017). The State did not concern itself much either with the substance of the agreement, including the price agreed, or any other benefits or detriments both parties committed to as part of the exchange. A ceiling was applied to the interest rate at 6% for most of the period. But in the absence of coercive means and a screening process for non-intermediated transactions, the legal rate could easily be disregarded. In this sense, most of the credit agreements mirrored flexibility and negotiability.

To a certain extent, the State did provide an infrastructure for the enforcement and sometimes the certification of such contracts, i.e. judicial courts. Lenders and borrowers could register their written contracts at court to guarantee their validity against a fee. And they could turn to a court to settle any dispute they might have concerning the terms of their contracts, especially related to the issue of repayment. Although verbal transactions might have been impossible to enforce at court (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 136). We still know very little regarding the proportion of default sought at court and the proportion of failures resolved informally. In 1868, a Bankruptcy Code was enacted, assuring greater security to the creditor (Turunen, Citation2017a, p. 262). Riina Turunen has shown that the number of bankruptcies and foreclosures increased significantly from the late 1870s onwards (Turunen, Citation2017a, p. 271). The resort to court for contract registration and certification was not mandatory and meant a transaction cost. Overall, peer-to-peer lending was based on the needs and expectations of lenders and borrowers. Contrary to the depersonalisation of lending today, most of these nineteenth-century credit relations were socially embedded and originated in fact in personal relations, i.e. the existence of strong, tight-knit social networks.

Finland’s political situation and relative under-development resulted in a significant delay in the emergence and development of banking institutions compared to other Nordic and Western countries (Kauko, Citation2018). In 1809, Russia defeated Sweden in the Finnish War (1808–1809). As a result of the peace treaty of Fredrikshamn, Finland, then part of the Swedish kingdom, was annexed to the Russian empire. The Grand Duchy of Finland, albeit under Russian rule, remained semi-autonomous and preserved most of its Swedish institutions and legislation. In 1812, the Bank of Finland was established in the then capital of Åbo by Tsar Alexander I, before being relocated to the new capital, Helsinki, in 1819 (Kuusterä & Tarkka, Citation2011). From the beginning of the nineteenth century to 1860, various currencies circulated in the country (Kauko, Citation2018; Voutilainen et al., Citation2020). In 1860, Finland adopted its own currency, the Finnish Markka (abbreviated mk). In 1917, in the chaos of World War I, Finland gained its independence and finally broke free from Russia.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Finnish population increased rapidly. With the exception of the Finnish famine of 1866–68, when about 8% of Finns died of hunger, the population grew consistently by 153% from 1801 to 1900 (Häkkinen, Citation2018; Hjerppe, Citation1989; Voutilainen, Citation2016). On the eve of World War I, just a little over 3 million inhabitants populated Finland.Footnote1 Most of the rural and urban dwellers settled in the south of the country along the coast. In parallel, despite the demographic pressure, few people chose emigration for most of the nineteenth century, especially compared to other northern countries. It is not until the end of the nineteenth century that the migration rate rose. It increased from 13.2 per 1000 inhabitants in the decade 1881–1890 to 54.5 per 1000 inhabitants in the decade 1901–1910. An estimated 300,000 Finns emigrated to the United States (Hatton & Williamson, Citation1998, p. 96). The demographic explosion and the low emigration rate combined engendered, in part, a process of proletarianisation. In particular, the proportion of landless workers had doubled in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the 1860s, about 80% of the population was employed in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. In 1914, this proportion still reached about 70%.

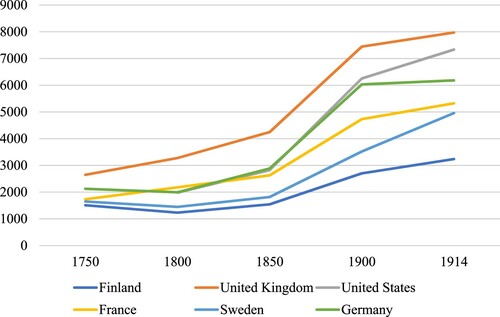

The level of development in Finland lagged behind other Western European regions by far (see ); industrialisation occurred late compared to other countries in the area. The situation improved in the last decades of the nineteenth century. For most of the nineteenth century, agriculture and forestry engendered the main source of revenue and employment. But the Finnish economy started taking off in the 1860s, thanks precisely to its wood, timber and tar industry. A series of legislative reforms in the 1860s prompted economic growth and contributed to the liberalisation of the economy and the boosting of the secondary and tertiary sector occupations. In 1857, a prohibitive order on the establishment of steam-powered sawmills was lifted. Finland gained its own currency, the markka, in 1860, and trade guilds were abolished (1859, 1868) (Hjerppe, Citation1989, p. 19). In parallel, the paper industry developed. The Finnish market, then a highly domestic market, expanded increasingly into Europe. Exports increased from 10% of the GDP in the 1860s to 25% in the 1880s, a constant level until the eve of World War I (Hjerppe, Citation1989, p. 151). But despite these rapid changes, industries contributed to less than 20% of the GDP until the 1890s. Various hurdles in the period 1860–1890, such as crop failures, currency devaluation, and the international context, hindered Finnish development (Pipping, Citation1969, pp. 10–12). In the period 1890–1913, the volume of gross domestic product grew by 3% per annum (Hjerppe, Citation1989, p. 47). In 1900, the Finnish GDP per capita corresponded to 37% only of the British equivalent and 76% of the Swedish one (Bengtsson, Missiaia, Nummela, & Olsson, Citation2019, p. 1). Many rural dwellers still had an occupation related to agriculture and forestry. In the period 1880–1910, their proportion went down from 79.2% to 63.7%. In fact, in 1880, only 8.5% of Finns lived in urban areas (Pipping, Citation1969, pp. 22–23). And between 1880 and 1910, the part of the population working in the industrial sector rose from 7% to 15% (Pipping, Citation1969, p. 22). Private consumption rose steadily from 1860 onward (Ojala, Eloranta, & Jalava, Citation2006, p. 43).

Figure 1. Real GDP per capita in 2011 USD, 2011 benchmark. Source Maddison Project Database, version 2018. Bolt, Jutta, Robert Inklaar, Herman de Jong and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2018), www.ggdc.net/maddison.

Before 1860, the Bank of Finland and a few savings banks were the only institutions granting formal credit before the advent of commercial banking institutions (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996; Kuusterä & Tarkka, Citation2011; Pipping, Citation1969). Then, their share of the GDP was about 0.4% (Hjerppe, Citation1989, p. 83). Savings banks emerged in the 1820s under the impulse of philanthropic initiatives. Just like in the United Kingdom or Sweden, these institutions aimed at encouraging the workers to save (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996; Lilja & Bäcklund, Citation2016). They met a relative success at first. In the second half of the nineteenth century, their number rose steadily, attracting greater deposits especially in rural areas. Savings banks also acted as lenders and provided credit to borrowers who could offer securities (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996).

But Finland remained a modest market for commercial banking activities. In 1861, the first mortgage bank opened its doors, the Mortgage Society of Finland, Finland’s Hypoteksförening or Suomen Hypoteekkiyhdistys (Pihkala, Citation1961). Its initial aim was to provide credit for farmers. For this purpose, Hypotekförening was an association based on the principle of mutual guarantees among the debtors (Kuusterä, Citation1994, p. 137). The first commercial bank, Suomen Yhdys-Pankki, the Union Bank of Finland, was chartered in 1862 and served the needs of the business community (see Herrala, Citation1999; Pipping, Citation1969). In 1866, Finland issued its first banking act, a set of regulations inspired largely by Sweden, in which financial activities were tightly regulated. The banks had to trade solely in gold, silver, bills of exchange and interest-bearing paper, limiting de facto their reach in the population. Furthermore, the senate had to give its permission for the establishment of a commercial bank. This resulted in further delay for the commercialising of banking products. The second banking act was enacted in 1886 and defined a bank as a business, ‘Which is engaged in borrowing from the general public by means of deposits or bonds issued’ (Andersen, Citation2010, p. 114). In this context, Vaasan Osakepankki, or Vasa Aktie Bank, featured in our sample, was funded in 1879 in the northern town of Vasa. It was the first commercial bank with strictly provincial interests (Lefgren, Citation1975, p. 86). Vasa Aktie Bank soon extended to the rest of Finland via regional branches. In 1920, the total deposits reached the 160 million mk. In 1919, Finland counted twenty-four commercial banks, its historical peak (Herrala, Citation1999, p. 7).

Delayed in commercial banking development, Finland was nevertheless a leader in cooperative banking (Kuusterä, Citation1994; Odhe, Citation1931). Its cooperative system attracted international praise (see for instance Langlois, Citation1940; Marshall, Citation1958; Odhe, Citation1931). In the beginning of the twentieth century, cooperative banks based on the German Raiffeisen model started to emerge (see especially Guinnane, Citation2001; Hilson, Markkola, & Östman, Citation2012). Under the dynamic impulse of Hannes Gebhard, inspired by Friedrich Raiffeisen who had founded the first cooperative in 1864 in Germany, the movement was stimulated and encouraged from above (Gebhard, Citation1927; Hallstén, Citation1924). A central organ, Osuuskassojen Keskuslainarahasto (Central Credit Fund of the Cooperative Banks), was first founded in 1903 (Kuusterä, Citation1994, p. 138). Progressively, with the support of the State, the central institutions set local credit cooperatives throughout the country. The cooperatives targeted especially farmers. Contrary to saving banks which encourage deposits, cooperative banks aimed at granting capital. A typical credit cooperative had between 20 and 50 members, usually from the same parish, featuring thus strong sociability ties. A management committee, elected by the members, took care of daily business. In the first years, the loans remained modest. By 1910, the cooperatives lent 51.9 million mk and had 370 branches throughout the country (Kuusterä, Citation1999). Cooperative banks really took off in the 1920s (Hallstén, Citation1924, pp. 30–36).

A vast array of other lenders coexisted with banking institutions and informal peer-to-peer lending (Pihkala, Citation1978). Gradually, in the nineteenth century, charitable and ecclesiastical funds, state funds and various mutual aid groups, as well as insurance companies, proposed saving and lending schemes of a various nature. All these financial actors proposed different services tailored to people’s needs and expectations. In nineteenth-century Finland, not only did formal and non-intermediated financial markets coexist, but they were also numerous and diversified.

II. The dataset

Probate inventories constitute the best archival material with which to draw a sketch of private financial markets in nineteenth-century Finland. They have long constituted a rich source for the study of not only personal wealth and material culture, but also for the analysis of credit and debt (Hemminki, Citation2014; Huldén, Citation2018; Markkanen, Citation1978; and also Keibek, Citation2017). Made mandatory in 1734, when Finland was still attached to the Swedish crown, this legal practice remained effectively in place after 1809. Probate inventories listed a decedent’s property, such as real estate, movables, livestock, and other assets. More importantly, a list of detailed claims and liabilities was also included. Customarily, probate inventories aimed not only to settle the division of the estate among the heirs but were also used for the repayment of outstanding debts. The document served also as a means of taxation; a small tax of 0.125% was deducted on the value of the probated estate. The list of debtors and creditors points particularly to our purpose. Names of the debtor/creditor and the amount of money at stake are mentioned. However, the type of contract or agreement between the parties is not often referred to, while the ultimate purpose of the debt seldom appears. Nonetheless, the lists of the decedents’ claims and liabilities give us a general sense of financial activities at the time t.Footnote2

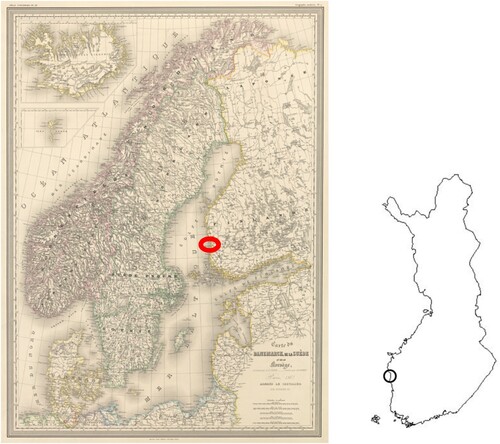

The dataset for this study includes 1047 probate inventories for adults older than 20 years from the coastal town of Kristinestad (Kristiinankaupunki in Finnish) and its hinterland, the parish of Lappfjärd (Lapväärtti) for the years 1850–55 and 1905–1914.Footnote3 The area is located along the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, approximately 250 kilometers north of Turku and 130 kilometers south of Vasa (see ). Kristinestad grew increasingly into a commercial centre and a dynamic harbour throughout the period under investigation (). A growing number of wealthy merchant houses exported all sort of products including resin, tar, oats, laths, planks, butter, meat, etc. (Mäkelä, Mäkelä, Pettersson, & Åkerblom, Citation1984; Sjöblom, Citation1915, pp. 181–187). The good number of probate inventories and the continuity of the sample also justifies the choice of this area for the present study.

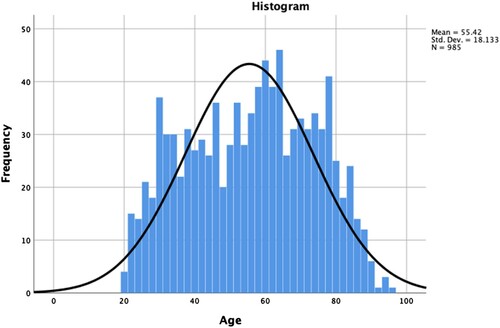

Figure 3. Histogram of probated decedents’ age at death (older than 20 years old) in both Kristinestad and Lapväärtti, 1850–1914. Source: the dataset.

While probates appear as the most suitable source for the reconstruction of credit networks, this type of document is not without its flaws. First, age distribution may appear problematic. The decedents tended to be older than the rest of the living population and might have accumulated more wealth. One of the central issues, while using probate inventories, is thus the adjustment of the sample to the living population. This can be done while using the inverted mortality rate (see Appendix). Håkan Lindgren and Carole Shammas, among others, have shown that this bias can be corrected by using inverse mortality multipliers based on the mortality rates of different age groups (Lindgren, Citation2002; Shammas, Citation1978). For our purpose, the age of the decedents mattered as it could potentially affect not only their capacity to borrow/lend but also the type of credit instruments at their disposal (see ). The age of the decedents, often absent in Finnish probates, has been retrieved in church records or newspaper necrology notices for 93.9% of our sample. The mean age at death is 55.42 for adults older than 20 years (). In both locations, the decedents witnessed their life expectancy prolonged over the period considered.

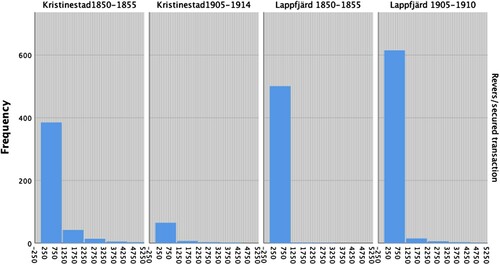

Figure 4. Distribution of promissory notes by value in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914. Source: the dataset.

Second, not everyone had property worth listing after their death. Markkanen estimates that, at the beginning of the twentieth century, only a third of the decedents had an inventory written up in central Finland (Markkanen, Citation1978). In contrast, before World War I, 60% of the decedents in South West Finland had a probate inventory compiled corresponding to levels one finds in Sweden. But this proportion was only 16% in North East Finland (Lindgren, Citation2002, p. 821; Moring, Citation2007, p. 235). Those without a probate inventory might have been too poor to have anything to pass over to the next generation and/or to be able to pay the requested fee on the gross assets. One cannot discard the fact that some probates might have been lost. For Lappfjärd, it seems that increasingly over the period we are considering here, a greater number of probates were written up, perhaps the result of an increase in household wealth. While in Kristinestad, on the other hand, fewer probates were written, perhaps because of the increasing pauperisation of urban workers (see ). For our purpose, the under representation of poor decedents might overshadow a part of the informal or non-intermediated credit markets, leaving aside numerous small credit transactions and deferred payments. A fraction of poor dwellers, however, appear in our dataset as creditors or debtors, giving us a glimpse of their financial activities on the market. In addition, the number of probate inventories for the wealthiest might also skew the data.

Table 1. Overview of the probate inventories in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

In order to resolve this bias, the dataset can be adjusted to the living population socio-professional status (see Table 5). However, these figures are only estimates as the categorisation between our dataset and the figures available may differ (see Appendix).

In Lappfjärd, the mean for the decedents’ net wealth increased throughout the period, while it decreased in Kristinestad. The wealthy merchants often featured a net wealth over 10,000 mk while the poorest urban or rural worker’s estate was estimated between 0 and 200 mk. An estate worth 201–1000 was considered of small means while an estate ranging between 1001 and 5000 mk was considered well-off (Markkanen, Citation1973, p. 41). At the beginning of the nineteenth century in Ilmajoki, most inhabitants qualified as poor and very poor (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 104). In the North of Finland, the average wealth of a farmer in 1850 was circa 2200 mk and the one of a crofter about 550 mk. In 1890, the average wealth of a landed farmer equalled 5100 mk while that of a crofter amounted to 550 mk (Aunola, Citation1965, p. 35) ().

Table 2. Decedents and their total wealth in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

Table 3. Breakdown of the probate sample by sex and marital status in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

Table 4. Distribution of decedents by age in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd 1850–1914.

Out of 1047 probate inventories, 514 pertained to women, while 533 concerned men (). It is nonetheless important to note that probate inventories listed the assets and property of the entire household without distinguishing their original owner. In traditional communities, upon marriage, goods and assets formed a homogeneous heap. This heap, called community property, regrouped all assets bought in common and any income from either of the spouses, with the exception of property inherited by both spouses. The male head of the household managed and looked after this community property throughout the duration of the marriage. Upon death, goods and property were recovered by their original owner. In nineteenth-century rural Finland, the widow inherited a third of the community property, while the widower inherited two thirds, legal heirs shared the remaining parts (Markkanen, Citation1973). Gradually, in the nineteenth century, community property assets were progressively divided in half.

This legal patriarchal disposition often hindered women’s economic well-being. Many widows flirted with poverty and had to rely on their familial network for survival. Retirement contracts in nineteenth-century Finland allowed the widow to transmit her property to her children in exchange for room and board. In the late-eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, Beatrice Moring finds that married women had 97% of the property of men, but widows had only 34% in South West Finland (Moring, Citation2007). For our purpose, therefore, decedents, either male or female, are considered as households since the property of the spouse who died first was not personal ().

Table 5. Decedents according to their socio-professional status in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

III. Credit in Kristinestad and its surrounding rural area in the nineteenth century

3.1. Features of the credit market in Kristinestad and its rural hinterland

Probate inventories provide a solid overview of lending and borrowing characteristics in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Finland. The dataset includes a total of 1047 probate inventories featuring 5525 credit relations for a total volume of 2,431,573.6 inflation-adjusted mk (index year 1914), approximately 5.3 transactions per inventoried person. Note that for convenience all currencies in circulation have been converted and adjusted (on this see especially Ojala, Citation1999; Voutilainen et al., Citation2020, appendices). About 34% of the decedents died leaving no liability and 66% died leaving no claim, while 23% of the decedents left no outstanding claim nor debt. Note that both claims and liabilities are included here and that potential double entries have been eliminated. The total value of liabilities represented 55.6% of all transactions while the total value of claims represented 44.4% of all transactions.

As a point of comparison, the decedents of the rural parish of Ilmajoki had incurred more debts than claims. There, the majority of decedents had incurred between one and ten liabilities (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 135). The rate of reciprocal exchanges seems to have been high. There too, the tendency was a general increase of households’ claims and liabilities throughout the period (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 142).

gives an overview of credit relations in both Kristinestad and Lappfjärd. The average size of a debt per inventory increased in both locations throughout the period. However, the mean size per decedent was significantly smaller in rural Lappfjärd. This can be explained by the presence of wholesale merchants in Kristinestad and better-off households consequently skewing the data. Not surprisingly perhaps, the ratio of claims/ liabilities shows a more uniform spread in rural areas. On the other hand, the spread was much more important in Kristinestad. There, merchants’ probates often featured their personal debt and credit relations but also that of their business. We have to wait until at least the late-nineteenth century for this distinction to materialise.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of credit relations in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914 (markka 1914).

Overall, debt can be divided into three main categories: the peer-to-peer transactions between households, the transactions between a household and a private company (banking services and trade) and a debt between a household and a public institution (often for tax purposes). For the period 1850–1855, most of these credit relations took place between individuals. With the advent of banking institutions in the mid-nineteenth century, we observe an increasing share of banks and companies in the credit transactions for the period 1905–1914. For the purpose of this article, the focus is mainly on both the peer-to-peer transactions and the transactions of households and banking institutions.

Interestingly, the proportion of peer-to-peer transactions in both areas decreased significantly throughout the period. On the eve of World War I, only about a third of the financial transaction observed took place between households. Even if we add the unknown transactions that were likely to be peer-to-peer exchanges, the proportion still decreased, especially in the urban area (from 91.7% to 60.65%). In Kristinestad, the proportion of peer-to-peer exchanges shrunk to the profit of trade and commerce companies, banking institutions and mutual help funds. This can be explained by the growing standardisation and legal framework in relation to business and companies. Companies operated under their own names and became separate entities.

3.2. Varieties of credit

Probate inventories give a snapshot of credit relations and their purpose. Claims and liabilities inscribed on probate inventories often kept silent regarding the exact purpose for which households borrowed money (See Hemminki, Citation2014, pp. 136–141 for a discussion on this issue). But it is clear that credit was ubiquitous in daily transactions, either to support considerable investments or to incur a smaller debt and to make ends meet (see ).

Table 7. Overview of the nature of the claims and liabilities of the decedents in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1905–1914.

Deferred payments, for instance, often feature small daily transactions and represented a usual feature of peer-to-peer transactions. Either because of a temporary shortage of cash in circulation (especially in rural areas) or because of a temporary lack of disposable cash in the household, deferred payments often prevailed to delay the payment of crafted and subsistence items. In fact, 72% of the decedents in our dataset did not leave any cash.Footnote4 Europeans have long used running tabs at the shops, with artisans of all sorts, and with each other. Harvests often gave an irregular rhythm to repayments. When the merchant Alexander Johan Sjöberg died in 1853, his probate inventories listed his personal claims and liabilities, including the ones of his shop (räkning or enligt boken mentioned). Out of 141 transactions inscribed, 69 represented deferred payments by several customers. Private debts and the decedent’s business transactions formed an undistinguishable heap, at least until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Deferred repayments have perhaps not yet received the attention they deserve. An ersatz of credit, often featuring a negligible amount of money, deferred payments allow us to measure the pulse of local economic life. Just like credit cards today, deferred payments were therefore a form of loan. Deferred payments for a crafted item, for foodstuff or livestock, overall for household consumption, were ubiquitous. Because of the irregularities of income, the hazardous nature of harvests, the various domestic accidents and contingencies, and the general lack of coins in circulation, cash was often scarce in pre-industrial Europe and in Finland in particular. Many small shopkeepers, artisans and service providers accommodated customers with a line of credit facilities. This practice of delaying payment had turned into a norm long before the period examined here. One might have preferred to reserve cash for some other debt to repay, perhaps older ones. For the shopkeepers or the seller, it was largely a matter of having the patience to await payment for everything one has sold. Deferred payments could also cancel each other out in reciprocal exchanges where ungoverned reciprocity prevailed. In fact, this practice of deferred payment has persisted long into the twentieth century.

Traditional scholarship has argued that deferred payments did not feature any interest rate (Muldrew, Citation1998). Recently, however, some historians have showed that despite the absence of contract between the parties, oral transaction could possibly carry an interest rate (Shaw, Citation2018). Presumably, this rate was often lower than in written transactions. In Finland, it is unclear if any price at all was included or not in the repayment amount. Probate inventories did not mention interest rate for deferred payments, but one may assume that the price might have included some monetary compensation for the delay in repaying the shopkeeper, artisan or merchant. And if no monetary indemnity was hidden in the price, a sense of moral obligation towards the creditor certainly engendered an unbalanced – if not unequal – relationship between the parties in which the creditor retained the upper hand.

The farmer Anders Stormartonen from the village of Bötom had loaned money to 11 fellow farmers all ‘utan revers’ – without contract – for small amounts, possibly as deferred payments. His 11 loans amounted all together to 20 markka.Footnote5 Oral transactions, albeit difficult to track, represented a small proportion of existing debts. One may assume they often appeared in the non-specified debt reported and sometimes in the unsecured transactions whose nature it is impossible to determine. Maria Finne and her husband from the village of Dagsmark, for instance, owed three mk to Johan Finne, a relative also from Dagsmark ‘utan revers’. This mention indicates the informal nature of the transaction. Presumably, because of strong ties between the parties, a written contract appeared superfluous and perhaps even offensive.Footnote6 These type of transactions, oral, informal and deferred could be found especially in the mid-nineteenth century. A certain formalisation took place then and were progressively replaced by written and formalised instruments.

Peer-to-peer loans in Finland were often characterised in probate inventories as either ‘secured’ or ‘unsecured’ (säkra/osäkra). Presumably, a secured transaction would be retrieved by the heirs in full, while an ‘unsecured’ loan would likely not be recovered in full or at all. What were the grounds to establish such a distinction? First, scholars seem to agree on its vague boundaries (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 141). Second, such a dividing line did not necessary entail an absence of written contract of any nature. It seems, rather, that the debtor’s solvency was at stake. It is the argument of Hemminki for instance: an unsecured debt would likely not be repaid because of lack of available funds (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 141). It could also be the case that the debt had overrun the repayment deadline or had fallen far to the bottom of the seniority line of repayments (Aunola, Citation1967).

Mutual aid societies (kassor of various nature) supplied another type of transaction featured in probate inventories (Berg, Citation2015, Citation2017). Mutual aid societies’ significance remained modest throughout the period in our dataset. As decedents were older than the living population, it is possible that younger rural and urban dwellers belonged to other mutual aid funds in greater proportion. Throughout Finland, countless local, parish-based and small cooperative funds existed and served various purposes (on cooperative banking per se see Kuusterä, Citation2002). Only a handful of studies have shed light on their financial services (Aronsson, Citation1992). Some mutual aid societies resulted from private initiatives while some other were semi-public institutions. Religious funds provided credit and relief to disadvantaged families and some specialised in the preparation and financing of funerals. Retirement funds offered the possibility to save for old age. Just like contemporary rotating saving and credit associations, these funds offered insurance, a saving opportunity and credit lines to people. These funds applied interest rates; Bengt Åke Berg has recently found that 5% instead of 6% was applied in rural Sweden (Berg, Citation2015, Citation2017). As these mutual aid funds were often local institutions, members knew each other, could monitor and screen each other’s behaviour. Meanwhile, insurance companies, especially fire insurance, arose in the nineteenth century. But contrary to the self-help funds, fire insurance companies were profit oriented and did not present the same features as the local mutual aid funds ().

Table 8. Overview of the promissory notes in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

Finally, promissory notes were the most popular type of transaction between individuals. In the mid-nineteenth century, before the advent of banks, promissory notes represented the most popular form of credit transaction both in terms of volume and number of transactions in Finland but also in Sweden (Hemminki, Citation2014; Lindgren, Citation2002; Perlinge, Citation2005, pp. 69–70). Their popularity then declined significantly at the turn of the twentieth century. A promissory note (reverslån and assimilated) was a written agreement, often collateralised, and usually served to finance a productive investment. Promissory notes were fungible and could be presented at court to retrieve and enforce unpaid payments (Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 136; Ögren, Citation2003, p. 160; Perlinge, Citation2005, p. 70). But a promissory note could also have been used to alleviate a gap of trust between parties. Abraham Pärus from the village of Lappfjärd, for example, owed 150 mk to his daughter. They signed a reverslån likely for her to be able to retrieve the money upon his death without protestation on the part of other potential heirs.Footnote7

In both Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, the average size of such loans exceeded other types of debt, indicating not only their attraction but also their productive nature. Those transactions were written contracts with negotiated terms of agreements, often featuring collateral (real estate and land for example). Promissory notes were especially popular among the better-off, such as the mercantile bourgeoisie, but also among the landed peasantry, who could all too easily offer collateral. The legal interest rate was capped at 6% until 1884, although a lesser – and more important – rate could be negotiated and applied. Note that informal transactions escaped close supervision and that a lack of coercive means would make shark lending possible. There are 1682 promissory notes in the dataset (30.5% of the total transactions) covering 27.5% of the total volume. Most of the promissory notes remained modest and stipulated an amount between 100 and 1000 mk (mean=378.8; average value of real estate among all the decedents = 1744, see ).

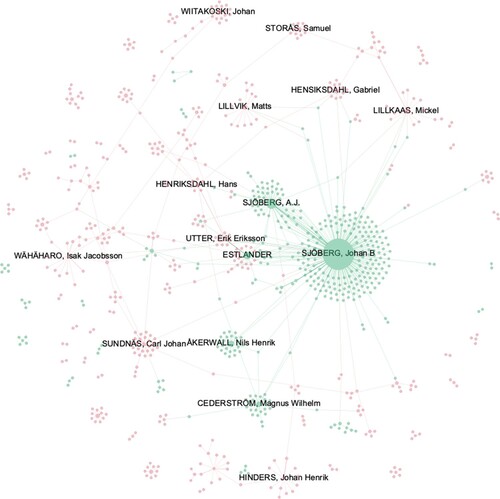

How were promissory notes exchanged and who used them? In 1850–5, we observe a few interactions between Kristinestad and its rural hinterland (see ). Promissory notes remained highly correlated to personal relations and homophilic patterns, such as living in the same village and working in the same labour sector. These homophilic trends apply especially to rural communities. In Lappfjärd, farmers mutually favoured each other (). In Kristinestad, promissory notes circulated among merchants and the bourgeoisie. Presumably, merchants (Magnus Cederstörm, Nils Henrik Åkerwall and the two Sjölander merchants featured in the network for example, ) used promissory notes as a common financial tool to secure their business transactions, especially with each other. Some of these wholesale dealers could also act as professional moneylenders. In Kritinestasd, some wealthy merchants such as Simon Anders Wendelin even printed their own ‘sedelmynt’, bank note, a fungible means of payment (Sjöblom, Citation1915, p. 209).

Figure 5. Network of promissory notes in Kristinestad and Lappfjäard in 1850–5. Nodes are coloured according to their geographical origins (Red for Lappfjäard and Green for Kristinestad) and weighted according to their out-degree. Source: the dataset.

Table 9. Relations between creditors and debtors in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd using promissory notes, 1850–1914.

But apart from these creditors, the lower strata of society, such as farmers and artisans, also extended credit using promissory notes, a highly accessible tool despite illiteracy. One notes that some members of the urban bourgeoisie did extend credit to farmers in a vertical fashion, likely on the basis of existing business relations between them (Åström, Citation1977; Aunola, Citation1965, p. 166). Farmers could use their land as security to reassure their creditors. The wealthy merchant Nils Henrik Åkerman, for example, extended credit to seamen but also to farmers. One should note that the landless, unable to provide landed collaterals and/or co-signers had much more difficulties to access this type of loans.

With the notable exception of merchants, no one in either community really made excessive use of promissory notes. No real dominating ‘parish banker’ or ‘village financier’ could be found if we focus strictly on the out-degree of the nodes (see ).Footnote8 Håkan Lindgren found farmers extending over 30 loans in Norra Mörre in the mid-nineteenth century (Lindgren, Citation2017). It seems that Finnish farmers’ capacities remained more limited in comparison. Yet, a handful of individuals featured in the network extended more than 10 promissory notes (4.4% of all the creditors). The pastor of the community, Estlander, did sign an important number of promissory notes with both urban and rural dwellers. His function undoubtedly allowed him to get easy access to his parishioner’s information. Nonetheless, the vast majority of individuals (91.8% of the creditors) extended only between 1 and 4 loans using promissory notes.

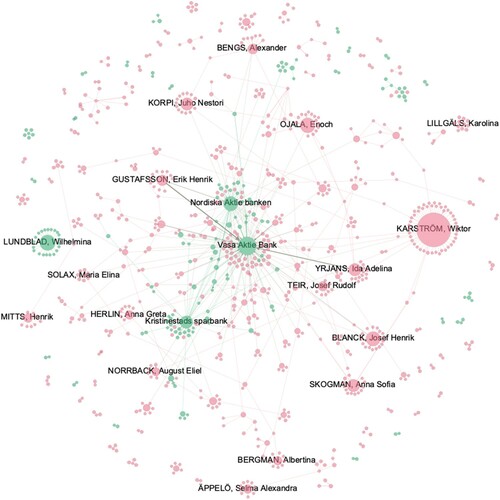

Figure 6. Network of promissory notes and bank loans in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd in 1905–14. Nodes are coloured according to their geographical origins (Red for Lappfjärd and Green for Kristinestad) and weighted according to their out-degree. Source: the dataset.

Some nodes present a more strategic position in the network despite their lower out-degree. The farmer Carl Johan Sundnäs from Skaftung, for example, recorded overall 30 loans, 28 outstanding loans (1559 mk) and 2 claims (1940 mk). The mean per promissory note in the rural area was only 30 mk. In that sense, his saving and lending capacity was far superior to that of his counterparts. Sundnäs also presents the highest eigenvector centrality value in the network, meaning he was very well connected to other central nodes. It is possible these connections made him both well informed and influential. His betweenness centrality – that is, how often he found himself on the shortest paths between nodes in the network – is among the highest.

On the left-hand side of the graph, the farmer Isak Wähäharö did not have any outstanding claim but 14 debts owed to several individuals (total 1642 mk, 41% of his total assets). Yet, he was connected to other influential nodes, making him in turn well connected and informed. Possibly, these links allowed him to find capital to borrow more easily.

Chains of credit also emphasise the strategic and dominant position of certain nodes in the network. In rural Lappfjärd, such clustering could be a significant predicator of behaviours, such as money transfers and borrowing for example. In the meantime, such high clustering also emphasises the interdependency of the actors in terms of the allocation of funds. On the one hand, in the event that one actor could not meet his repayment obligation, the entire chain of credit could be affected. But on the other, high clustering in a network suggests cooperative or prosocial behaviours as these relations were socially embedded, making lending easier (Jackson, Citation2014, p. 13). One must keep in mind that a credit tie was also a social tie.

Over time, promissory notes seem to have lost their attraction. One notes a decrease in terms of volume and proportion in both Kristinestad and Lappfjärd at the beginning of the twentieth century (see ). Agents signed fewer promissory note contracts. Once again, no one monopolised the allocation of credit at the beginning of the twentieth century. More than 68% of the agents had only one outstanding claim, while 27.9% had between two and five outstanding claims and about 4% of the private lenders could pretend to lend between 10 and 25 promissory notes. One merchant, Viktor Karström, had 52 outstanding claims (see ). His centrality measures did not make him a significant actor in the network. His interactions were mainly with outsiders. Agents who continued to use promissory notes did it for bigger transactions.

The same tendency of loss of attraction has been observed elsewhere. Håkan Lindgren has shown that in the 1840s in Kalmar, for instance, promissory notes accounted for more than half of the total credit market. This proportion subsequently dropped at the beginning of the twentieth century to 30.5% (Lindgren, Citation2002, p. 827). Lindgren argues that banking institutions gradually replaced peer-to-peer lending.

IV. Changes and permanence: the rise of banking institutions

4.1. The rise of banks

In the area under consideration in this study, a number of banking institutions competed in the late-nineteenth century. First, savings banks could be found in many small towns across Finland. These institutions accepted small deposits remunerated by interest rates and encouraged long-term saving, especially for workers (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996; Lilja & Bäcklund, Citation2016). In 1823 and 1825, two savings banks were founded in Åbo and in Helsinki. Over the very first years, they attracted 200 depositors and by 1830, they counted 800. Between 1830 and 1840, the amount deposited tripled (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 51). The remuneration of deposits (about 5% for most of the period) rendered saving attractive and safe. In 1850, the country counted only a dozen of these institutions. But in 1895, their number jumped to 169. Between 1896 and 1918, 287 new saving banks were established (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 86 and 156). New establishments lifted from the ground especially in rural areas after 1860 (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, pp. 78–89 and 156). The number of savings accounts experienced a rapid and sharp rise at the end of the nineteenth century with about 93,000 depositors in total in 1895 (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 91). In urban areas, the majority of deposits came from shopkeepers, artisans, civil servants and workers. In contrast, in rural areas, the majority of the depositors were landed farmers. Deposits were in general small, the majority were under 100 mk (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, pp. 96–97). Shortly after the start of World War I, in 1915, roughly 10% of the living population had a savings bank account. In our dataset, 63 households out of 1047 had a savings bank account (6%). Savings banks also extended capital. Most of the loans went to business owners in urban areas (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 102). In Uleåborg between 1875 and 1895, for instance, 31% of the loans were directed to artisans and 29% to small retailers. In rural areas, landed farmers who could offer land as a collateral represented the majority of the borrowers, although the volume of loans there remained modest (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 103).

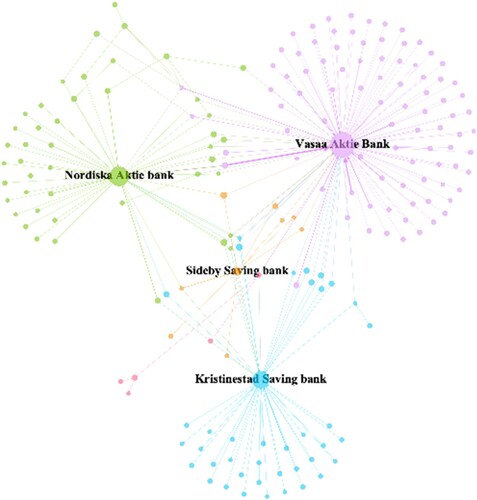

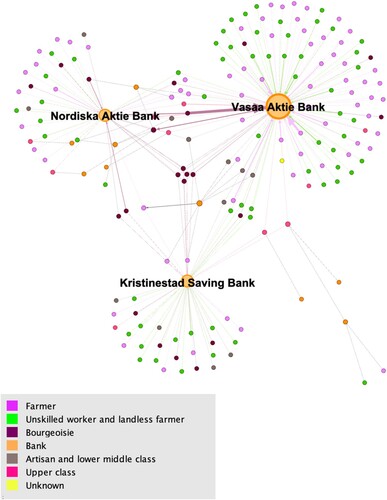

In the area under consideration here, Kristinestad Savings Bank opened in 1852. Other small local savings banks featured in our network, such as Sideby Savings Bank, were also active in the area (see ). Savings banks had the particularity of being hyperlocal.

While the purpose of saving banks was to attract deposits, cooperative banks aimed at lending capital. In Finland, cooperative banks started their operations in 1903 (Gebhard, Citation1927). Up until the eve of World War I, their number had risen rapidly but their operations had remained modest in comparison to commercial banks for instance (Hallstén, Citation1924; Kuusterä, Citation2002; Odhe, Citation1931). They primarily targeted farmers to encourage development and investment (Kuusterä, Citation2002). That explains why they are not featured in Kristinestad. However, cooperative banks did not seem to have been popular yet in Lappfjärd, at least not in the period examined here.Footnote9 Some authors mentioned a certain resistance on the part of Swedish speakers along the coast to adopt cooperative banking (Odhe, Citation1931, p. 106). One has to wait until the 1920s to witness the establishment of cooperative banking in the area.

Commercial banks also competed with savings banks for depositors. Finnish commercial banks, however, were chartered well after saving banks. Just like in the United States, the initiative to obtain a banking license from the government came from merchants and town officials (Lamoreaux, Citation1996). In 1859, both in Åbo and Jyväskylä, merchants and civil servants teamed up to draft a proposal. They were both rejected. Presumably, the Bank of Finland, which also lent money, did not look favourably on the newcomers. One had to wait until the 1860s. In 1862, the Hypoteksförenings Bank was created. Ten years later, the Nordiska Aktie Banken för Handel och Industri was chartered. The primary purpose of the bank was to act as an international bank for facilitating trade and commerce. Its central office was located in Viborg (Pipping, Citation1962, pp. 24–27, 45); it soon opened affiliated offices throughout the country. Other commercial banks were chartered in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The Vasa Aktie Bank, featured in our network, was founded in 1879 and opened a branch in Kristinestad almost immediately. This provincial bank was quite successful; the volume of deposits, between 1886 and 1913, was multiplied by five (Aaku, Citation1957, pp. 102–103).Footnote10 Therefore, at the beginning of the twentieth century, potential customers were offered a wide range of options for depositing their savings and eventually borrowing capital (see Table 10).

In the period 1905–1914, the number of bank loans between households and banking institutions increased progressively (see and ) following the national trend (Pipping, Citation1969, p. 144).Footnote11 While banks still preferred to lend capital to companies and entrepreneurial ventures, rather than households, some banking institutions such as the Vasa Bank began increasingly to target households especially for their savings (see ). In Lappfjärd, one notes that the 38 bank loans to individuals were three times more important than the mean loan recorded for promissory notes ().

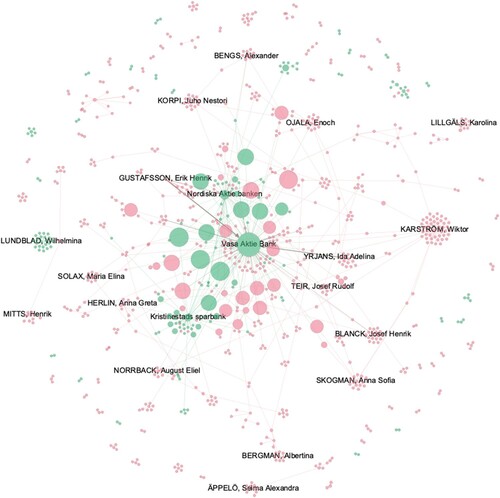

Figure 7. Network of promissory notes and bank loans in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd in 1905–14. Nodes are coloured according to their geographical origins (Red for Lappfjärd and Green for Kristinestad) and weighted according to their eigenvector centrality measure. Source: the dataset.

Table 10. Distribution of depositor facilities across banking institutions in Finland, 1870–1913.

Table 11. Overview of bank loans and deposits in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1850–1914.

Table 12. Estimation of the living population’s interaction with banking institutions in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1905–1914.

The number of bank deposits, and therefore bank accounts, opened in commercial and savings banks surpassed the number of bank loans. This can be explained by two reasons. First, logically, banking institutions began to attract clients by offering checking accounts against a remuneration, usually between 4.5 and 5%.Footnote12 Saving levels per decedent were almost three times higher in the city compared to the countryside. Several decedents owned several checking accounts or recorded several deposits (see ). Therefore, the number of bank deposits or bank loans does not necessarily match the number of account holders (see ). One can hypothesise that banks created a favourable trust environment, offering deposit features to savers first and only later proposing financial products, such as loans, to their existing and valuable clients (Kuusterä & Ahlholm, Citation1996, p. 48). Note that, in the meantime, banks could accumulate valuable information on their savers, before turning them into borrowers.

Figure 8. Banking institutions’ network in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1905–14. The nodes are weighted according to their out-degree and coloured according to their modularity class. Source: the dataset.

The different banks in the area shared a pool of common customers. They are featured in . In turn, these clients were well connected and well informed. We might wonder why a customer would have more than one bank account. Was it to spread the risk? Were customers targeted by several banks at once? One can only hypothesise. Customers who had more than two bank accounts presented a similar profile: urban dwellers from the bourgeoisie. When Gurli Teresia Johansson, the wife of a high-ranking civil servant died in February 1914 at age 35, her household left a series of outstanding loans owed to several banking institutions. The Bötom savings bank, Storå savings bank, the Vasa Aktiebank, the Nordiska Aktiebank and the Landtmannbank had all lent Johansson’s household capital, amounting to 15,623 mk.Footnote13 We know next to nothing regarding these banks’ screening process. But social status and connections appears key in the allocation of funds. Carl Alfred Carlström, for example, borrowed from the Vasa bank for his trading and commercial activities. Incidentally, he was also one of the bank directors and owned a substantial number of shares.Footnote14 He committed suicide after one of the bank’s shareholders committed fraud and forgery causing the bank important losses and precipitating Carlström’s business into bankruptcy. As Lamoreaux has shown, the local merchant elite often sat on banks’ boards and/or owned a large share of their stocks, allowing them to borrow easily (Lamoreaux, Citation1996).

Figure 9. Banks and their clients in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd, 1905–14 (coloured by socio-professional categories and weighted according to their degree). Source: the dataset.

Matts Wilhelm Martens, a merchant in Kristinestad and the chief accountant of Carlström’s company (who, incidentally, also committed suicide after the same scandal causing Carlström’s death), had three deposit accounts in three different banks: Vasa Bank (8400 mk), Nordiska Bank (9800 mk) and Kristinestad Savings Bank (600 mk).Footnote15 He was far from being the only one adopting this strategy (see ). His connection to Carlström, a bank director, might have provided him with insider information and preferential treatment.

Banks did not necessarily offer a different price than private lenders. The specification of the interest rate is in most instances missing. Maria Adelina Mattfolk, a farmer’s widow, borrowed simultaneously from three different banks. Her household took out a loan of 1600 mk at 6%, while the two other loans were each 200 mk at 7%. Bank interest rates generally oscillated between 6 and 7% (promissory notes featured an interest rate of 6%).

Customers of banking institutions did not necessarily abandon traditional practices of credit. Most of them continued to allocate funds via promissory notes and practiced deferred payments in parallel.

Probate inventories give only a snapshot of banking activities via the sole activities of decedents. These figures, therefore, might well have been higher for the living population. Håkan Lindgren estimates that ‘as early as in 1900, 47% of all credits in the Grand Duchy were granted by commercial banks’ (Lindgren, Citation2010, p. 200). By projecting the sample results to the living population based on age structure, about 21.5% of the inhabitants of Kristinestad and 23.7% of the inhabitants of its rural surroundings had a bank account. But only 22.5% in Kristinestad and 8% in Lappfjärd borrowed from a bank ().

The level of savings and the capacity to borrow might be affected by the occupation of the decedents, who tended to be better-off than the rest of the population. Specific estimates on the inhabitants of Kristinestad and Lappfjärd labour occupations do not exist but national statistics allow a rough estimate (see Appendix). By projecting the sample results to the living population, based on the socio-professional categories, one finds similar results for the number of savings account holders. But the projection for the number of people borrowing from a bank based on the socio-professional categories indicates a much lower proportion, around 6%.

Unfortunately, we cannot test these estimations as the records of bank account holders of the Vasa bank no longer exist, we cannot verify when decedents began to put aside money in banking institutions.

4.2. How did banks supplant private creditors? A hypothesis

In a society where trust has always been highly personal, banking institutions’ growth in the late-nineteenth century, in terms of clients, progressed slowly throughout Europe. There is still little understanding of how commercial banks supplanted peer-to-peer lending exchange; except for the rational argument that banks had a greater availability of capital and liquidity and less moral hazard and transaction costs. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, banks paid account holders interest to attract deposits. But the interest rate was not exceptionally superior to promissory notes.

The contagion/diffusion hypothesis via social network analysis can contribute to explain the migration of trust from private to institutional transactions. Friends, acquaintances, and kin might have referred an individual to a bank or recommended the use of a banking institution. They shared information, opinion and feedback via tight-knit social networks. Banks themselves might have leant on certain key individuals within the community as ‘injection points’ to promote their services (see Banerjee, Chandrasekhar, Duflo, & Jackson, Citation2013). These actors helped to diffuse information. In India, people who join a microfinance scheme are more than four times as likely to pass on to their friends information about microfinance (Banerjee et al., Citation2013, p. 4). There, the average degree of each household – regardless of the nature of the bond – is 15 (Banerjee et al., Citation2013, p. 13). This means that each household interacts, on average, with 15 others, possibly spreading information to them. It is conceivable that households in nineteenth-century Finland had a similar degree.

Interestingly, the Vasa bank, a latecomer on the banking scene, had an aggressive policy when it came to the recruitment of new clients. In the south of the country, they seduced numerous new customers who already had accounts with the oldest banks (Pipping, Citation1962, p. 149). The Vasa bank turned to potential customers who already had access to information and were therefore early adopters. It certainly helped the bank to cut transaction costs.

A few interactions between individuals with information and others without information can affect a large fraction of the population. After all, ‘one person’s behaviour affects the well being of others’.Footnote16 For instance, each actor in the network represents a potential link for spreading information about banks. In a network, if someone in a giant component opens a bank account, this can potentially set a trend among others via contact, influence, persuasion and emulation. The question, of course, is how many repeated interactions with bank account holders an individual needed to open an account in turn. Traditional sociological theory assumes that a few people adopt a new idea at first. Then, the proportion of new adopters rises until the trend is adopted. This produces an ‘S’ shaped curve of diffusion (Kadushin, Citation2012, p. 137). But we also need to remain careful with endogenous networks as they can have biased endorsement effects, because similarities across linked individuals tend to correlate their decisions independently of other factors (Banerjee et al., Citation2013).

Thanks to this approach, we can identify the so-called ‘opinion leaders’, or game changers within a network; such individuals have influence within the community and can promote change (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation1955; Valente, Citation1996). These high-degree leaders are usually well-placed in the network and have a high centrality and high eigenvector centrality, e.g. their centrality depends on their neighbours’ centrality. Naomi Lamoreaux has shown how American bankers did in fact lean on local social networks, especially the bank directors, to increase not only their customer base but to foster investors’ trust (Lamoreaux, Citation1996). In , for example, a few agents in the network were extremely well connected and present a high eigenvector centrality thanks to their ties to banks. One can imagine they were ‘injection points’.

A cross-analysis of bank material, such as account holders’ information, would reveal a bit more on such strategies and verify the ‘injection point’ hypothesis. Probate inventories alone cannot fully reveal diffusion in an exhaustive fashion. Unfortunately, such material has not been preserved for the Vasa Bank and the other banking institutions in our dataset.Footnote17 We are therefore bound to propose only a hypothesis.

Vasa Bank attracted depositors from various socio-professional groups but especially landed farmers (see ). It seems that the bank whose interests were primarily provincial targeted the same types of savers as savings banks. How did the bank recruit clients? In the absence of the bank records, one can only hypothesise. The diffusion theory may be key in answering this question. Some agents with the same last name and living in the same village appeared to be clients at the same bank. For example, four members of the Båsk family in Dagsmark had a bank account at the Vasa bank. Three members of the Storkull family living in Dagsmark and three Ulfves from the village of Lappfjärd all had a deposit account at the Vasa bank. These examples corroborate the diffusion effect. Future research on this aspect will provide details on the transition between traditional peer-to-peer lending to banking loans.

V. Concluding remarks

Before the advent of banks, peer-to-peer transactions offered urban and rural dwellers the possibility to save and lend money. These interpersonal networks remained largely confined to the limits of the community and formed in highly homophilic groups. Kristinestad and the rural parish of Lappfjärd offer such a picture in the mid-nineteenth century. There, people used different types of loan contracts tailored to their needs, expectations and capabilities.

In the rural parish of Lappfjärd, lenders and borrowers presented a similar profile. Members of the local community sharing the same living conditions, socio-professional background and same ‘mental state’ trusted one another. They exchanged between community members, often within homogenous groups, with and without written agreements. Trust was sustained thanks to strong norms of social proximity and a sense of community belonging. Cooperation, reciprocity and solidarity being thus the natural responses of communities facing the same hurdles. A significant degree of mutual insurance seemed to have prevailed. In Kristinestad, on the other hand, those ties seemed to have been looser. But the network analysis of probate inventories in the 1850s points to a mostly uniform network where no single private lender monopolised big chunks of the market for himself (with the exception of merchants for business reasons).

These peer-to-peer transactions progressively declined from the mid-nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, to the profit mainly of emerging banking institutions. As a consequence, personal ties were slowly replaced by more impersonalised ones, becoming disembbeded. At the beginning of the twentieth century, with the advent of banking institutions, banks increasingly turned into significant players, allocating funds and attracting agents’ savings. It is unclear how banks managed to convince their customers to open an account in the first place. But the hypothesis that an advantageous interest rate on deposit attracted a few customers, who in turn informed their relatives of this opportunity, could stand. Banks seem to have targeted the same clients’ profiles as they shared mutual customers. These customers show a net wealth of their estates far superior to their counterparts. Yet, banking institutions did lend to wealthy decedents from the bourgeoisie and the upper class while targeting the savings of farmers. Farmers seems to have passed on information on the advantageous saving scheme to their relatives and fellow villagers who opened deposit accounts as well. The early adopters of banking practices played, therefore, the role of injection points in their network. Nevertheless, banking institutions did not supplant peer-to-peer lending and both channels coexisted. At the eve of World War I, peer-to-peer lending still prevailed in Kristinestad and Lappfjärd. Comparison between probate inventories and bank account records in the future could help us resolve this issue of diffusion thanks to network analysis.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Riksbankens Jubileumsfund via a Pro Futura fellowship, the Jan Wallander och Tom Hedelius stiftelse (grant P17-0040) and the Marcus & Amalia Wallenberg Minnesfond (MAW2018-0015). Part of this paper was written while in residence at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioural Sciences at Stanford University. The author would like to thank Sofia Gustafsson, Tiina Hemminki for their help with the source material and the Finnish literature, and the anonymous referees for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Note that although usually three months were allowed for the preparation of a probate inventory, deadlines were not always met.

3 Note that for the period 1905–1914, the data for Lappfjärd includes probates from 1905 to 1911 while the data for Kristinestad extends to 1914 in order to have enough probates for a meaningful comparison. The dataset consists of (thereafter name ‘the dataset’): Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:14; Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad Eg:15; Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:21; Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:22; Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:6b; Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:7a; Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:7b; Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:8; Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:11 Lappfjärds tingslag; Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:12 Lappfjärds tingslag; Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:13 Lappfjärds tingslag.

4 A note of caution: the surviving spouse might not have been inclined to reveal this information to the probate assessors in order to keep the cash.

5 Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:6a.

6 Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:7a.

7 Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:13 Lappfjärds tingslags bouppteckningar, 140.

8 Anders Perlinge coined the term ‘parish banker’. See (Perlinge, Citation2005).

9 In the villages of Dagsmark, Sideby, Lappfjärd, and Tjöck, cooperative banks were established in the 1920s. In Lappfjärd, a cooperative store opened its doors in 1907 (Lappfjärd Andelshandel). Smaller branches were opened around in smaller villages in the 1920s. See also Lingonblad, Citation1953 on Närpes dairy cooperative. Cooperative banks in southern Ostrobothnia were established in Malax (operations started in 1904 there); Ilmola (Ilmajoki in Finnish) inaugurated its cooperative bank, Yläpää Cooperative Fund, in 1902, (see Hyvönen, Citation1953). And the Alapää cooperative credit union in Kauhajoki was established in 1903 (see Simonen, Citation1949). I thank Lasse Backlund and Riku-Matti Akkanen for their help with this information.

10 In 1920 Vasa Aktiebank, Landtmannabanken in Helsinki and Åbo Aktiebank in Åbo merged into Unionbank.

11 For the period 1850–5, only a couple of inventories mentioned banking activities.

12 Interestingly, rural and urban dwellers considered these deposits as claims in their probate inventories.

13 Kristinestad, Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:22 Bouppteckningar, Johansson.

14 Kristinestad, Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:21 Bouppteckningar, Carlström.

15 Kristinestad, Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:21 Bouppteckningar, Martens.

16 Cited in M. Jackson (Citation2019), from Henry Sidgwick, The Principles of Political Economy.

17 Either the material could not be found in the archives (Vasa Aktie Bank) or was not accessible for consultation (Kristinestad Savings Bank and other saving banks).

References

Source material

- Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:6b.

- Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:7a.

- Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:7b.

- Korsholman eteläisen tuomiokunnan arkisto (VMA), Lapväärtin käräjäkunnan perukirjat, E2a:8.

- Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:11 Lappfjärds tingslag.

- Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:12 Lappfjärds tingslag.

- Närpes domsags arkiv, E2c:13 Lappfjärds tingslag.

- Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:14.

- Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad Eg:15.

- Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:21.

- Rådstuvurätten i Kristinestad, Eg:22.

Secondary sources

- Aaku, E. (1957). Suomen liikepankit 1862-1955. Helsinki: Suomen pankkiyhdistys.

- Ågren, M. (2018). Providing security for others: Swedish women in early modern credit networks. In E. Dermineur (Ed.), Women and credit in pre-industrial Europe (pp. 121–142). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.

- Andersen, S. E. (2010). The evolution of Nordic finance. Manheim: Springer.

- Aronsson, P. (1992). Bönder gör politik: det lokala självstyret som social arena i tre Smålandssocknar, 1680-1850. Lund: Lund University Press.

- Åström, S.-E. (1977). Majmiseriet : Försök till en Komparativ och Konceptuell Analys. Historisk Tidskrift För Finland, 62, 90–108.

- Aunola, T. (1965). The indebtedness of North-Ostrobothnian farmers to merchants, 1765–1809. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 13(2), 163–185.