ABSTRACT

This study revises the picture of the interwar Czechoslovak land reform as an example of a successful non-violent land reform. The study reveals that the land reform in Czechoslovakia, which passed as a revolutionary change, did not reach its announced targets: the redistribution of the land to landless and land-poor people and the reduction of inequality of land distribution in society. Based on the hypothesis that even when there is a strong ruling agrarian political party, and no opponents to a land reform in the country, there is no guarantee of its successful realisation, the study follows two aims: (1) a revision of the real outcomes of the land reform in interwar Czechoslovakia; (2) an analysis of why the land reform failed in expropriating and redistributing the land. In doing so, the study discusses how the land reform was stolen from the peasants and to what measure the theft was calculated.

Introduction

The Czechoslovak land reform was fictionalised and even mythicised immediately after its introduction in 1918. The narrative depended on the authors’ ideological, political and national background. Texts written by members or sympathisers of the Agrarian party glorified the land reform as a social and national masterpiece. In this view, the land reform satisfied landless people hungry for land, equilibrated social inequality and returned the fatherland to the nation from which it was stolen during the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century. In contrast, sympathisers of the Agrarians’ political opponents criticised the clientelism and corruption that accompanied the land reform. Moreover, German and Hungarian interwar historiography criticised the reform for its anti-German and anti-Hungarian nature.

The second half of the twentieth century introduced two U-turns in the narrative of the land reform. As post-1948 Marxist-Leninist historiography became obsessed with a search for a revolutionary tradition in Czechoslovakia (Doležalová & Holec, Citation2016), the first U-turn emerged. In Marxist-Leninist historiography, the peasantry became the revolutionary force of the Czechoslovak countryside (Otáhal, Citation1963). The land reform started to be called the first land reform, while the second land reform was realised by the Nazis after March 1939 in the framework of Germanisation and the third land reform was implemented between 1945 and 1948. When the Czechoslovak Communists came to power in 1948 they introduced forced collectivisation in the Stalinist style (1948–1960). Marxist historiography particularly emphasised that while the first land reform fortified the position of the Czechoslovak bourgeoisie, and the second land reform was an act of the nation's enemies, the third land reform corrected the wrongs of both previous processes and secured real justice in land distribution. Post-Communist Czech historiography made a second U-turn, back towards defending the first land reform and its social nature: the land reform became an act of social justice that satisfied the landless people's hunger for land and rectified the unjust allocation of land tenure. The same statistics of the land reform that were used as proof of capitalist exploitation by Marxist historiography now became proof of the successful resolution of social problems of the Czechoslovak countryside.

Also, in the context of European historiography, the interwar Czechoslovak land reform is considered a successful reform that achieved the most beneficial results in Eastern Europe not only in the sense of its swiftness (Federico, Citation2005, p. 150) and the acreage of the redistributed land (Borodziej, Holubec, & von Putkamer, Citation2020, p. 16) but also in a macroeconomic perspective and in the sense of an increasing importance of medium-sized tenures (Feinstein, Temin, & Toniolo, Citation2008, p. 68). Only rarely do historians take into consideration its negative consequences (Balcar, Citation1998; Cornwall, Citation1997; Miller, Citation2003). This study calls into the question the narrative of the Czechoslovak land reform as a successful example of land reform by revealing three mistakes in its existing interpretations: that the land reform expropriated a third of the entire Czechoslovak acreage; that it liquidated the dominion of large estates and that the land was redistributed in favour of landless and land-poor people.

The main target of any land reform in history has been to transfer land from the rich to the poor and reduce the inequality of land distribution in society. The term land reform, however, covers a wide spectrum of ownership structural changes from small adjustments through to the breaking up of large estates and distribution of their lands to small farmers in (forced) collectivisation (Albertus, Citation2015; Barlowe, Citation1953; Eckstein, Citation1954–1955; Lipton, Citation2009). The main assumptions connected with any land reform are: first, that land reform promotes more equal assets and income distribution among farmers; second, that reinstating former large estates after land reform is politically too expensive (Federico, Citation2005, pp. 176–177); and third, that land reform can moderate social clashes in the country, including nationalist clashes (Albertus, Citation2015, p. 5).

It is not an easy task to place Czechoslovak land reform after the Great War in its proper position on the spectrum of ownership structure changes mentioned above, as it does not fit any of the main types of land reform. As this study reveals, it was not a pure type of classic land reform in a democracy (Lipton, Citation2009, p. 6) since its legislative framework was not introduced by a democratically elected Parliament. It was not a negotiated land reform (Albertus, Citation2015, p. 8) since there was no radical split between political and land elites; moreover, the proposals to sequestrate and expropriate land were introduced by a right-wing political party. Neither was it a redistributive land reform (Albertus, Citation2015); although the state compensated the owners of expropriated land, it was not at the market rate. The land reform in Czechoslovakia was not colonisation, with the exception of the Sudeten borderland and Slovak part of the country where, however, the state not only redistributed the land that was not used, it did it regardless of private, municipal or state form of ownership. At the same time, the Czechoslovak land reform challenges all the above-mentioned assumptions linked with any land reform. The land was not redistributed according to the needs of the most impoverished peasants; it did not satisfy their hunger for land; it did not improve the peasants’ well-being and it did not eliminate the fundamental inequality and social clashes in the countryside which in the multinational state of Czechoslovakia often had a national face.

Czechoslovak land reform was a non-violent intervention into the ownership of four million hectares of land (both agricultural and non-agricultural) introduced by the Revolutionary National Assembly immediately after the establishment of the new state and orchestrated by administrative bodies created on the principle of political participation. As shows, fewer than half of the four million sequestrated hectares were allotted to new owners.

Figure 1. The results of the Czechoslovak land reform by the end of 1937 (in hectares). Source: Statistisches Jahrbuch (Citation1938, p. 55).

Using the statistics published by the official land reform bodies and the statistical office, and with research into the dozens of cases of expropriation and redistribution of the land that can be found in the National Archive in Prague, this study follows three aims:

To revise the real outcomes of the land reform in interwar Czechoslovakia.

To analyse why the land reform that was called a revolution and even the crowning act of the revolution and its true realisation (Cornwall, Citation1997, p. 259), failed to expropriate and redistribute land.

To test the hypothesis that even with a strong ruling agrarian political party and no opponents to land reform, there is no guarantee of the successful realisation of land reform in a country.

The study is organised as follows. The first part of the article describes Czechoslovak agriculture before the land reform was introduced and analyses the political and ideological background of its introduction. The second part explores the evolution of the legislative framework of the land reform, analyses the metamorphosis of motivations and strategies of the actors involved in the process and distinguishes two break points in the process of the land reform in Czechoslovakia. The third part analyses the extent to which the main goals of the land reform were achieved, explores the hidden driving forces of the reform that influenced both the legislative process and its implementation, and investigates the winners and losers of the land reform in Czechoslovakia. The fourth chapter distinguishes the factors that influenced the process of the land reform. The conclusion formulates the lesson that can be learnt from the Czechoslovak land reform.

A background to the revolutionary change: the ownership structure and ideological background to the land reform in Czechoslovakia

Capturing the ownership structure of Czechoslovak agriculture before 1918 is complicated by the heterogeneity and non-comparability of data from the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the monarchy. Not only were different units of measurement used in the Czech, Slovak and Subcarpathian parts of Czechoslovakia, but also a cadastre did not exist in the eastern regions of the Republic in 1918, unlike in the Czech part, and was not completed before 1938. Generally speaking, the ownership and production structure of Czechoslovak agriculture was the result of developments that had been brought about by the abolition of second serfdom and patrimonial bonds for compensation after the revolution of 1848; the legal norms of the process of abolition were introduced already in the 1770s. The compensation allowed the large landowners not only to expand agricultural production but also to invest in other areas – mainly in banking and industries that were closely linked to agriculture (brewing, sugar industry, woodworking industry) as well as railroads (Urban, Citation2003, p. 116). After the agrarian crisis of the 1880s, the indebtedness of agriculture grew up by 210%; 60–70% of farms in the category of up to 5 ha fell into debt. As a consequence of the growing number of foreclosures and the commercialisation of the land market, the number of ownership changes increased. Until the end of the nineteenth century, the total number of farms regardless of size, increased by 30%; the number of farms up to 5 ha rose by 90% and the number of farms that were larger than 100 ha by 100% (Urban, Citation2003, pp. 116–117).

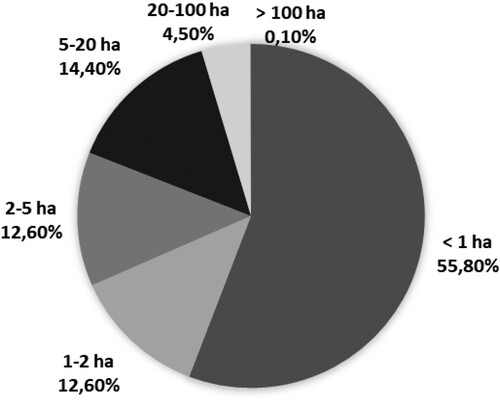

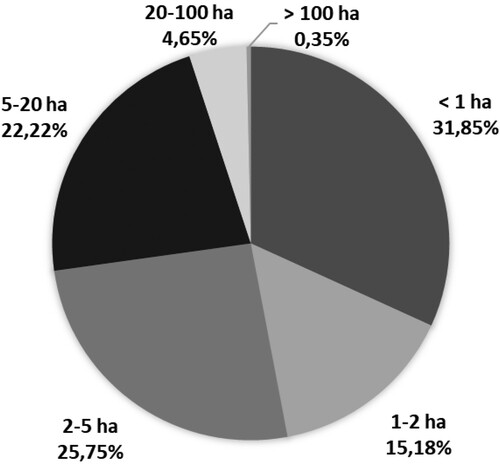

The ownership and social structure of the countryside of the future Czechoslovakia was composed of completely landless people; people managing their own or leased land; craftsmen that combined working in agriculture with handcrafted production; small-sized farmers managing land up to 10 ha with the help of a hired workforce; mid-sized farmers with acreage between 10 and 20 ha (up to 25 ha in Slovakia) supplemented by small-scale businesses (most often a pub); large estate owners (20–100 ha); and aristocratic large estate owners with acreage larger than 100 ha. The following figure shows the number of landowners according to their acreage in the future Czechoslovakia before the Great War ().

Figure 2 Landowning structure in Czechoslovakia before the land reform. Sources: Urban (Citation2003, p. 121) for the Bohemian Lands and calculation based on Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 160 for Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus. + less than 2.5 ha in Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus. ++ up to 25 ha in Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus.

In 1910, 3,489,289 people worked in agriculture in the Bohemian Lands (2,142,601 of them being family members) (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 106); from the viewpoint of Austrian statistics at that time, family members were neither owners nor employees (Horská, Citation1972). 25% of the remaining 1,346,688 people working in agriculture were landless (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 111). At the same time, only 932,925 of the total number of 1,593,507 landowners worked in agriculture (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 111). In the Slovak part of the future Czechoslovakia, 1,769,780 people worked in agriculture (1,032,010 of them being family members) (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 128); 65% of them were landless people (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 161). And finally, 397,630 people worked in agriculture (245,971 of them being family members) in Subcarpathian Rus (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 128); 62% of them were landless people (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II, p. 161). Moreover, agriculture in the eastern part of the country manifested a significantly more extensive character; the output of 10 ha in the eastern part of the country was approximately equivalent to the output of 4 ha in its Czech part (Průcha, Citation2011, p. 182).

Despite significant inequality in the land distribution, there was no room for considerations about land reform in the Bohemian Lands; a land reform was not a programme priority for any of the existing political parties. When the traditional political parties of Staročechs [Old Czechs] and Mladočechs [Youth Czechs] were replaced by modern political parties during the last third of the nineteenth century, Social Democratic and Agrarian parties (distinguished further according to nationality) started to dominate. The strongest political player however remained the group of large landowners that were not politically organised; the original core of their representation was formed by the Staročechs. The position of the large landowners in political life was fortified by the Austro-Hungarian political tradition: before the introduction of universal suffrage in 1907, one large landowner electoral vote was equivalent to 46 urban electoral votes and 168 countryside electoral votes. After the last general election before the Great War in 1908, large landowners gained 70 of 236 seats in Bohemian Diet (Doležalová, Citation2008).

The agenda of Agrarian political parties aimed at supporting agriculture, as opposed to the Social Democrats’ support of industry. In fact, the core of their interest was the expansion of agricultural industry in the hands of large farmers with up to 500 ha of land. As their fundamental principle, Agrarian programmes formulated agrarianism, defined as the love of the fatherland, the ultimate source of all national life, and the only means of sustaining a nation. The programme encompassed a personal and emotional relationship to the land as well as working directly on it (Doležalová, Citation2015). Despite the party's slogan ‘In the countryside, we are all one family’ until 1919, the main target group of Agrarians remained middle and large landowners and the Agrarians’ political activities were driven by the confrontation between the rapidly expanding capitalist towns and the more slow-moving countryside.

For the Social Democrats, as a party protecting the interests of workers in industry, the farmers and peasants represented a conservative and anti-modernising class connected with the large landowners. The Great War radicalised the attitude of the Social Democrats towards the agrarian question; they started to consider the agrarian question as a problem of class conflict in the countryside when Lenin brought this idea forward in revolutionary Russia. While for Lenin land reform was a necessary precondition for the unifying workers and peasants, for the Czech Social Democrats it was but a tool for solving the question of how to supply the workers in the cities. They defined the nationalisation of land as a fundamentally Slavonic and Socialistic requirement (Otáhal, Citation1963, p. 59).

Despite the indifference of the Social Democrats towards the agrarian question, the first theoretical as well as practical contemplation about the land reform in Bohemian Lands had Social Democratic roots. The author was the Social Democratic politician and economist Josef Macek. In his contemplations published in Citation1917, Macek was influenced not by Karl Marx but by Adam Smith and the English reformers Henry George and Thomas Spence, and the German Social Democratic politician Gustav Hildebrand. Under their influence, Macek incorporated the agrarian question including the land reform as the basis for solving social issues (he used the term socialisation) into the framework of the social question in the Czech environment. Macek understood the agrarian question as a fair division of the land and saw the root of all social evil in large estates. In his analysis of inequality and capitalistic exploitation, he called for the elimination of the land monopoly (Doležalová, Citation2018a, pp. 94–99). He estimated that the process might take more than two hundred years and proceed through two simultaneous processes. First, economic compulsion by progressive taxation and strict restriction of the hereditary right and, second, through a voluntary change of human beings through education and ethical influence (Macek, Citation1918).

At the end of the Great War, the political landscape of the Bohemian Lands had been shaped by the leftist Social Democratic Party and National Socialist Party, and the rightist Agrarian Party, National Democratic Party and Catholic People's Party. The large and middle landowners were not yet politically organised; however, they formed circles around the National Democrats and the Agrarians respectively. The vast majority of rural inhabitants gravitated towards the People's Party. A few months before the end of the war, when the representatives of the political parties established the National Committee, the purchase of the land from the large estates in favour of landless people appeared among the first steps in its unofficial programme that focused on what had to be done after Austria-Hungary's prospective capitulation. In October 1918, the expropriation of the large estates for inner colonisation was mentioned in the Washington Declaration, which is considered the first attempt by Czechs and Slovaks to formulate the rules for the establishment of their independent state.

Pillars of the change: the institutional and legislative framework of the land reform in Czechoslovakia

The establishment of Czechoslovakia in October of 1918 falls into a turbulent period of European history. The Great War changed Europe not only in the territorial sense; in Central Europe, it irretrievably destroyed the whole system of monarchist norms, relativised the aristocratic ethos and questioned the existing patterns of dominion and power. It also shook people's confidence in the existing economic and social organisation and opened the door to alternative economic systems with significant state involvement. Czechoslovakia was no exception.

Under the umbrella of socialisation, Czechoslovakia introduced relatively extensive state interventions to the economy that manifested themselves not only in the land reform but also in the nationalisation of strategic materials and some industrial fields that gave birth to the state sector; in the strongly progressive assets levy that was introduced as a part of monetary reform; and in what was known as ‘Nostrifikace’ [domestication] of selected industries that transformed the ownership structure and executive and administrative functions in favour of Czechoslovak citizens in those companies that had their headquarters in Austria (or Hungary), but their operational premises in Czechoslovakia (Doležalová, Citation2013).

Most Czechoslovak political parties rhetorically adopted the concept of socialisation after the establishment of Czechoslovakia, with a narrative of defending Europe against the import of Bolshevism from Russia. Despite their position in the political spectrum, political parties started to publicly support social insurance, the eight-hour work day, minimum wage, improvement of working conditions and revision of the private ownership of land. Moreover, within a few weeks, representatives of all the political parties agreed publicly with Macek's statement (Macek, Citation1917, p. 10) that the land reform should solve three burning social questions: landless and land-poor people's hunger for land, depopulation of the countryside, and unemployment in cities (Doležalová, Citation2008). However, the first Czechoslovak governments paid little attention to the land reform in their policy statements, and the land reform was not an official programme priority of any of the political parties when the land reform was proposed in the National Revolutionary Assembly.

Three acts that were passed between the spring of 1919 and the spring of 1920 are usually connected with the land reform in Czechoslovakia: the Act on the Expropriation of Land; the Act on the Allotment of Expropriated Land, and the Act on Compensation. In fact, more than three dozen acts related to the land reform were passed during these years and the legislative process of the land reform actually started six months earlier. The first of them was submitted as the third proposal during the first sitting of the Revolutionary National Assembly in November 1918.

The proposalFootnote1 was presented by the right-wing national-democratic MP and future minister of finance, Karel Engliš, and asked for the temporary protection of forests to prevent their exploitation by their owners. Engliš rationalised his proposal by fears that owners, worried by omnipresent rumours about expropriation and confiscation, would exploit the forests and threaten the future Czechoslovak woodworking industry. The Agriculture Committee of the Assembly was reluctant to support the proposal, arguing that forests were sufficiently protected by the Imperial Patent No. 250/1852 and by Imperial Act No. 31/1879 on forestry, which defined the state supervision over the administrative bodies of private forests through inspectorates and forest management offices (Krajčovičová, Citation1996). Because of these objections, the proposal was not passed until 17 December 1918 (as Act No. 82) and was overtaken by the norms that were proposed later. First, by Act No. 32 of 9 November 1918 on the sequestration of all estates in the country that was proposed in order to prevent them from being sold off or run into debt by their owners. After this, any property transaction had to be officially approved by the Ministry of Agriculture. Second, by Act No. 61 of 10 December 1918 that cancelled aristocratic titles and privileges in Czechoslovakia.

On Thursday 9 January 1919, the first government (14 November 1918–8 July 1919) of a broad ‘all national’ coalition consisting of rightist National Democrats, Agrarians and the People's Party, and of leftist Social Democrats and National Socialists, came up with its policy statement. It was at the same meeting where right-wing MPs proposed to expropriate and nationalise all forests in the country because ‘ … it is in the state's interest to maintain the forest assets in good condition, to protect them, and to exploit them in favour of the whole nation, since forests are of great importance to the public.’Footnote2 However, the first prime minister, National Democrat Karel Kramář, concentrated his speech on post-war economic reconstruction and only in one sentence did he mention the colonisation and expropriation of large estates without specifying its extent; he called for ‘the expropriation of estates beyond a certain acreage.’Footnote3 Another aspect of the prime minister's speech deserves our attention. When Kramář announced the nationalisation of (‘taking control over’) the mining industry, including the distribution of raw materials, members of the Assembly in the auditorium were screaming: ‘Foreign capitalists have already raked us clean more than enough!’Footnote4 The narrative of a new heroism of rebelling against ‘foreign’ owners fit well with the new republic's paradigm of history, in which Czechs became the bearers of democracy in the Bohemian Lands before the incursion of feudal and inherently undemocratic German elements.

This narrative allowed Agrarians and Social Democrats to transform the land reform from the rectification of an unfair allocation of land into a tool for a new reallocation of resources and the national takeover of economic power in the next few months. The same narrative can be distinguished in the nationalisation, in monetary reform and in so-called ‘nostrifikace.’ However, the parties were not yet unanimous in their concepts of how best to solve the agrarian question. The Social Democrats called for the confiscation of large estates and the creation of co-operatives of small farmers in group ownership; the National Democrats conceded to the formation of model settlements; the Agrarians called for the redistribution of land in favour of small-sized farmers. Differences existed even among the different national Agrarian parties within Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak Agrarians spoke about the ‘popularization’ of land, whereas the German Bund der Landwirte supported the idea of the land reform in which disabled war veterans and landless agricultural workers would receive the land. The Hungarian parties called for the allocation of land in Hungarian-speaking areas exclusively to Hungarian peasants (Doležalová, Citation2011a). The only agreement among them was that the land reform should be inner colonisation; i.e. the redistribution of land laying fallow for the benefit of local peasants.

Even though the main target of the redistribution of land for the Agrarians was still the equalisation of conditions of industrial and agricultural production and even though, according to their banners, the countryside was still one family, within a few weeks, the Agrarians came to an agreement with Social Democrats on the question concerning the large estates of what extent must be parcelled out: it should be the land of large estates with acreage above 1000 ha that is not used. For every peasant's hunger for the land to be satisfied, Josef Macek proposed to move the border line to 500 ha. Agrarians agreed. Before discussing the expropriation act in the Assembly, Social Democrats accepted the Agrarian claim to compensate the original owners. Their narratives were, however, different. The Agrarians connected compensation with the untouchability of private ownership, and hence the duty of the state to pay for the expropriated land. The Social Democrats saw in compensation by the state the toll for the mobilisation of their voters against large landowners; as Josef Macek stated earlier, it would be politically reckless to attack large landowners’ possessions until landowners began to be publicly criticised (Macek, Citation1918, p. 69).

Acceptance of Macek's statement by crucial political representatives announced the first turning point of the game; I call this phase of the land reform in Czechoslovakia, the social-nationalist phase. Its primary goal was to ostracise large farmers as large owners. In the surrounding public narrative, however, large owners were defined according to their nationality. Thus, an appeal to national awareness became a tool for the social mobilisation of the masses to support the land reform (Doležalová, Citation2006). For both, Agrarians and Social Democrats, it was essential to find a proper public narrative for the land reform. While the Social Democrats, in agreement with the official political ideology introduced in revolutionary Russia, regarded landlordism as a great evil that was to be eradicated (Scheidel, Citation2017, p. 127), the Agrarians proposed the original Czechoslovak narrative that soon prevailed. Knowing the complicated national inheritance of Austria-Hungary, we can call this narrative a nationalist one.

According to the statistics from 1906, 5,073,896 ha of the entire agricultural land in the Bohemian Lands was divided amongst 868,402 owners. Among them, 244 large estate owners with tenure over 2000 ha owned 28.3% (1,436,084 ha) of the entire land (Fiedler, Citation1906, pp. 174–175). In Slovakia, 955 large farmers owned over 546 thousand hectares of land (Průcha et al., Citation2004, p. 83). The owners of large estates with acreage larger than 2000 ha started to be called foreigners-Germans, Hungarians and Jews - that had had no other goal for three hundred years than to exploit the Czech (and Slovak) lands; they were excluded from the term countryside. Land gained a national status and, in the Czech part of the country, the land reform started to be publicly promoted as revenge for the lost Battle of White Mountain in 1620 and the exile losses of the original Czech nobility during the subsequent Thirty Years War. In Slovakia, the narrative was that the land that had been stolen by Hungarian conquerors after the fall of Great Moravia in the tenth century had to be returned to Slovak hands.

On 20 March 1919, a group of right-wing MPs proposed to expropriate large estates, defined as estates where the acreage possessed by the same owner or owners was more than 250 ha, excluding forests.Footnote5 In its final version, the Act on Expropriation (No. 215 of 16 April 1919) expropriated acreage exceeding more than 150 ha of arable land or more than 250 ha of land including forests for an indefinite period. Estates owned by municipalities, local authorities or the state were excluded from expropriation. Estates owned by the Habsburg family were confiscated by the Czechoslovak Republic without compensation. All land transactions after 28 October 1918 had to be declared invalid.

Shortly thereafter, the Act No. 330 of 11 June 1919 established the State Land Office (hereafter the SLO). Right-wing National Democratic MPs presented the proposal for its establishmentFootnote6 as a necessary step to reduce land reform paperwork in the Ministry of Agriculture. The SLO was subordinate to the government; it consisted of a Chairman and two Vice-Chairmen appointed by the Czechoslovak President after the government nomination. According to Act No. 330, the SLO officers had to be chosen through competition; in fact, their composition followed the political structure of the Assembly with the leading role played by Agrarians, National Democrats and Social Democrats. The SLO had complete executive, decision-making and punitive power concerning land reform. It had to examine expropriated land and decide which objects of expropriation to exclude; supervise the management and administration of sequestrated but not yet expropriated land; manage the expropriated property, specify the range and tools for allocation, select applicants for allocation or renting of land, examine the eligibility of new landholders, and prepare purchases or rental contracts; set the salaries for state administrators of allocated land; and provide long-term loans to the land administrators, specify the loan conditions and mediate the contracts with banks. Besides, it had to supervise livestock, take care of paperwork related to employees, monitor the new administrators’ activities and progress, and assist in forming cooperatives.

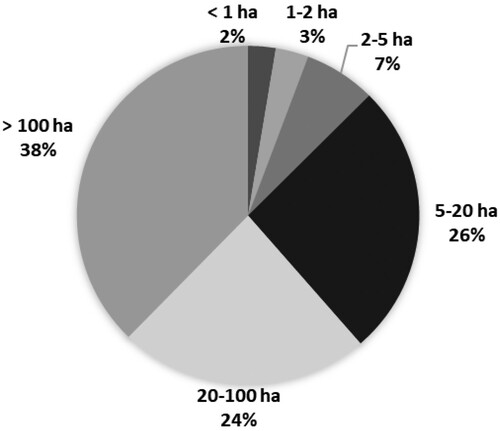

After acts on the expropriation and the SLO passed, inner colonisation as a tool of the land reform metamorphosed into a wider method of the redistributive land reform and the land reform was elevated to a programme priority of all political parties as a key tool to achieve social peace. Programme slogans of all the parties were re-directed toward landless people and small-sized farmers and any support for large farmers disappeared (Doležalová, Citation2008). The Agrarians agreed with the extent of expropriation which jeopardised their members and traditional voters for reasons of election arithmetic. As and demonstrate, there was at one end of the spectrum of the countryside population, a land-rich but very small group of aristocratic large estate owners, and at the other end of the spectrum was a very large group of small to medium-sized owners who were the potential driving force behind the land reform. Any political party struggling for political power had to become a mass type of a party. The numerical superiority of small and medium-sized owners in the countryside defines the mass. A small stratum of countryside landlords did not guarantee electoral success.

Figure 3 Division of the land in the Bohemian Lands in 1906 (according to size of the tenure). Source: Calculation based on Fiedler (Citation1906, p. 174).

Figure 4. Division of the land in the Bohemian Lands in 1906 (according to the number of owners). Source: Calculation based on Fiedler (Citation1906, p. 174).

Agrarian worries became a reality in June 1919 when, in the municipal elections that were held only in the Czech part of the state, Czech Social Democrats achieved 32.5% (German Social Democrats gained 47% of German votes) and National Socialists 17%. In comparison, Agrarians received only 15% votes (Průcha et al., Citation2004, p. 65). The consequence of the election results was the introduction of the second cabinet (8 July 1919–25 May 1920) in which Social Democrats dominated. In his government policy statement, the Social Democratic prime minister Vlastimil Tusar devoted only a couple of sentences to the land reform, when he called it ‘a great deal of social renaissance.’Footnote7 Under the pressure of election results, the Agrarians dramatically changed their attitude. As they grasped that the small group of large landowners could not guarantee their political success any longer, they briskly re-formulated their programme's headlines and changed the party's name to the Republican Party of the Czechoslovak Countryside. It was a wise and effective decision from both an economic and a political point of view.

The second turning point of the game followed soon: the Act on Allotment (Act No. 81 of 30 January 1920). Its introduction clearly shows the way through which, under the umbrella of nationalist and anti-landowners rhetoric, the Agrarian Party was changing its strategy. Until January 1920, Agrarians MPs’ speeches were reserved about expropriation. However, the allotment act put an offer on the table to participate in an unprecedented redistribution of private property. As the Agrarians described years later, their party always protected private ownership with only one exception: ‘In the nobility, we saw foreigners and that was our impulse for the land reform.’Footnote8 According to the allotment act, expropriated land was supposed to be allocated to small holders, legionnaires, and disabled people to enable them to establish an agricultural business or family farm of between 6 and 10 ha depending on the quality of the land. The act also ordered every large farmer to give an adequate part of his or her land to small applicant on a temporary lease immediately. Most importantly, the act briefly mentioned the terms ‘residual farm’ and ‘other large tenure.’ These terms referred to any acreage larger than 30 ha that could be economically depreciated by parcelling it out; other large tenures also included buildings and associated production facilities.

Two weeks after the allotment act, the Act on the Administration and Management of Expropriated Property (Act No. 118 of 12 February 1920) was passed. It was passed exceptionally quickly with the familiar argument that landowners who expected that the nationalisation would follow the sequestration, would not care for the land properly and might damage and exploit it. This way, all the large estates started to be supervised by the SLO (either permanently or temporarily). The SLO officials had to grant permission for any capital changes to a particular estate as well as for any business transactions. The last legal regulation that framed the land reform in Czechoslovakia was the Act on Compensation for Expropriated Land (Act No. 329 of 8 April 1920). It defined compensation at the price valid before the Great War (1913) deduced progressively from 5% to 40% in the case of land size exceeding 1000 ha. Compensation was to be paid either in cash or in 3% bonds; the latter form was more common.

We have already seen how the limit of expropriation was significantly enlarged by the fact that the nationality of the owners was publicly emphasised and how inner colonisation metamorphosed into redistributive land reform. After the introduction of the allotment act, the stress on ‘unused’ land and ‘local and in need’ acquirers also changed. I call this phase of the land reform in Czechoslovakia the nationalist-political phase: If up until January 1920, calls for national awareness had been emphasised to ostracise owners, now the question of the political allegiance of acquirers of expropriated land moved to the forefront. Without doubt, the hope of gaining a residual estate or other large tenure convinced the remaining critics of the land reform inside the Agrarian Party to support the land reform. Moreover, Agrarians used the opportunity and took the initiative to orchestrate the entire land reform process. They were under time pressure, since the first regular general election was due in June 1920.

In the general election in June 1920, the Social Democratic Parties won with 25.7% of votes. The Agrarians, with 13.6%, came second (Doležalová, Citation2008). The internal polarisation between the liberal and radical wings in the Social Democratic Party, which led to the foundation of the Czechoslovak Communist Party in May 1921, however, weakened the Social Democrats. The Agrarians became the strongest political party in Czechoslovakia. At that time already, the land reform moved from the Parliament to the countryside: the expropriation of individual estates and the allocation of expropriated land became the most dynamic area for clashes, not only political, between Agrarians and Social Democrats. There is no doubt this is why the implementation of the land reform acts was not finished until 1937.

The revolutionary change in progress: winners and losers of the land reform in Czechoslovakia revised

Despite the fast legislative process, Czechoslovakia took longer to implement the land reform acts than other countries that introduced a land reform at that time; the land reform ended in 1937 when the SLO published the official results that concluded the still unfinished redistribution of the expropriated land. According to the common picture of the land reform in Czechoslovak historiography, the land reform goals were accomplished: the large estates dominion was destroyed and the land hunger of the landless and land-poor people was satisfied through the massive redistribution of more than 4 million hectares of the land, 33% of which was arable land. In this picture, the winners of the land reform in Czechoslovakia were landless people, and the landowners were losers. This chapter calls this picture into question.

As for the destruction of the dominion of large estates, the sequestration act introduced the sequestration of a third of the whole territory of the country. Based on the expropriation act that followed, one could assume that everyone who owned more than 150 ha of arable land or 250 ha of land, including a forest, lost his or her land; the larger the owner, the greater the loss. In April of 1919 that meant 786 landowners with 2,348,406 ha of land in the Czech part of the country and 944 landowners with 1,614,658 ha of land in Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus combined (Statistická příručka,Citation1925, p. 571). The largest among them were the Schwarzenbergs (248,000 ha), Liechtensteins (173,000 ha), Habsburgs (77,000 ha), Czernins of Chudenice (61,000 ha), and Colloredo-Mannsfelds (58,000 ha). The largest owner of land in Czechoslovakia was, however, the Catholic Church (Novotný, Citation1994).

In fact, not all landowners suffered the loss of their possessions. Boix's dictum that big landowners oppose democracy because of fear of expropriation (Albertus, Citation2015, p. 91) is not valid in the Czechoslovak case. The majority of large and aristocratic landowners did find their way towards the new state – through the institution they established in response to the expropriation act and an anti-landowners campaign and its nationalist rhetoric: the Union of Large Landowners (hereafter the Union). The Union was established in the early spring of 1919 as a politically independent organisation associating owners of more than 100 hectares funded from members’ fees: each member had to pay a fee based on the acreage of her or his estate. The Union's main official objective was to maintain the landowners’ common interests and deal with the economic, social and cultural problems they faced. The Union offered consultancy on the broad spectrum of administrative and productive issues, including tax management; all free of charge.

Even though the Union was politically independent, it started to co-operate with MPs and secretariats of various political parties immediately: primarily with the National Democrats and the People's Party; the owners of smaller large farms (up to 500 ha) gravitated towards the Agrarians. Generally, members of the Union can be divided into two groups: while the first group criticised the land reform, the second group was willing to search for a compromise with state political power. Under the influence of the second group that was significantly larger, the implementation of the expropriation act became a touchstone of the Union's activities, since the vast majority of landowners asked for their sequestrated land to be removed from expropriation; the act allowed for the return of up to 150 ha arable land and up to 100 ha of the other land.

The selection of the estates to be expropriated was in the hands of the SLO. More precisely, it was in the hands of the Agrarians’ officials in the SLO. The first round of expropriation began in June of 1921. In the Czech part of the country, a three-year plan was introduced to expropriate 248 large estates defined as abandoned objects, negligently managed objects, objects belonging to owners with acreage larger than 5000 ha, objects that were not personally managed by their owners, and in the case of national interest, any other objects.Footnote9 In Slovakia, a one-year plan was introduced to expropriate and redistribute 88,060 ha (Krajčovičová, Citation2009, p. 215). In fact, the large estates of 150 owners (11 of whom were churches or monastic orders)Footnote10 were expropriated. By the end of the land reform, the expropriation was never applied in the full measure of both the sequestration and expropriation act ().

Figure 5 Land expropriated within the land reform. Source: Calculation based on Pavel, Antonin (Citation1937), Pozemková reforma Československá [Czechoslovak Land Reform], Prague, 2; Československá pozemková reforma v číslicích a diagramech (1925) [Czechoslovak Land Reform in Numbers and Diagrams.] Praha: Státní pozemkový úřad, 8–9.

![Figure 5 Land expropriated within the land reform. Source: Calculation based on Pavel, Antonin (Citation1937), Pozemková reforma Československá [Czechoslovak Land Reform], Prague, 2; Československá pozemková reforma v číslicích a diagramech (1925) [Czechoslovak Land Reform in Numbers and Diagrams.] Praha: Státní pozemkový úřad, 8–9.](/cms/asset/4ebb1afd-0e57-4c50-9443-fe1879e3fb06/sehr_a_1984295_f0005_ob.jpg)

At the end of the land reform, the majority of large landowners did not lose their property even though they were affected not only by sequestration but also by the assets levy within the monetary reform (Doležalová, Citation2018b). More than half the sequestrated land was returned to 1843 out of 1913 original owners. The expropriation affected, for instance, only 11,000 ha of the 248,000 ha that the largest landowners, the Schwarzenbergs, owned. Only 16% of the Catholic Church's land was expropriated (Novotný, Citation1994). In total, only half the initially sequestrated land was expropriated.

The measure of expropriation of individual estates fully depended on the density of the social network of their owners: whether they were Czechoslovak citizens or foreigners; whether they agreed or disagreed with the land reform; and most importantly, whether they were open to making a deal with the Agrarians. Foreign owners who did not live in Czechoslovakia and did not hold Czechoslovak citizenship thought that they were protected against expropriation by the peace treaties.Footnote11 Being surprised by sequestration, they did not hesitate to ask for diplomatic intervention or even for an audience with the Czechoslovak president to avoid expropriation.Footnote12 If they were citizens of the Allied Powers, the expropriation was often reduced or lifted.Footnote13 In some cases, their already sequestrated estates were bought by the state for a price that not only was higher than the calculated compensation price but was also higher than the market price, and was paid in cash in a few days (Dufek, Citation2008). German and Hungarian complaints on the contrary, failed even at the League of Nations (Cornwall, Citation1997; Kubačák, Citation1991–1992).

As far as satisfaction of hunger for land goes, landless and land-poor people were supposed to be the winners of the land reform in Czechoslovakia. We talk about 1,049,457 peasants who owned less than 2 ha in the Czech part of the country; together, they owned the same acreage as the 151 largest owners. Of these small landowners, 667,526 owned less than half a hectare of land. In the Slovak part of the country, 293,461 peasants owned between 2.5 and 5 ha of land. According to my calculation based on the retrospective statistics, approximately one million people were landless in Czechoslovakia before the land reform (Statistická příručka, Citation1925/II). Without any doubt, landless and land-poor people became the driving force behind the land reform as the number of their requirements for the land allotment became a decisive argument of the Agrarians in their successful struggle to avert the Social Democrats’ plan to create cooperatives in group ownership of the expropriated land.

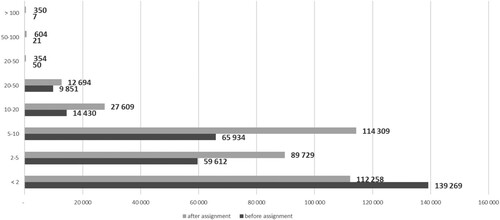

However, the expectations of the landless and land-poor people to receive the land allotment were not fulfilled, even though the redistribution of the expropriated land was in the hands of the Agrarian officers in the SLO; Agrarians even established local allotment commissaries to collect the names of those interested in acquiring land. Very soon, they also started to collect information from local Party members to determine which expropriated estate they or their friends were interested in acquiring. As shows, 2,270,994 ha of land remained for the allotment. In the first round of the allotment in 1922, commissaries received half a million requests for small-sized allotments.Footnote14 In order to accommodate everyone, only 0.4 ha could be allotted to each requestor. In general, each expropriated estate had more applicants than available expropriated land.Footnote15

According to the pre-war effectiveness calculation (Macek, Citation1918) and omnipresent public rhetoric, an allocation of 1 ha per person, or more precisely 5 ha per family, was supposed to be allocated. The majority of peasants did not reach that limit even before the reform, let alone after it. At the end of the land reform, only a fifth of the land-poorest peasants changed their social status, and land was assigned to only 60,000 landless people (Otáhal, Citation1963, p. 200) in favour of whom the land reform was originally introduced. By the end of 1928, the SLO had refused 41.9% of applicants; among them, the majority of claimants for minimal allotment. At the same time, approximately 15% of the small-sized allocations were given to large farmers (Otáhal, Citation1963, pp. 200–201). A second tendency was already visible in the first phase of the allotment. The following figure demonstrates the distribution of the small-sized allotments to 357,170 successful applicants in the first phase of the allocation of the land by the end of 1924. It shows that through the small-sized allotment the reform actually strengthened the group of the largest farms; whilst the number of farms between 20 and 50 ha increased seven-fold, the group of farms between 50 and 100 ha increased thirty-fold, and the number of farms larger than 100 ha increased fifty-fold ().

Figure 6 Distribution of small-seized allocations according to the number of assignees (by the end of 1924). Source: Calculation based on Československá pozemková reforma v číslicích a diagramech. Prague (Citation1925, pp. 27–28).

The trend persisted. In 1930, 1,578,694 ha of land (within it 825,817 ha of arable land) was allotted to 586,175 acquirers; among them, 583,060 small-sized acquirers gained 787,998 ha (within it 626,251 ha of arable land) including, however, nationalised land that is not further specified in the statistics.

In addition to the limited acreage of land at disposal and its unequal redistribution in favour of middle-sized and large farmers, and the omnipresent clientelism, there was another reason for the small number of successful small-sized allotments. Every applicant had to pay for the allocated land. While the compensation for the expropriated land was based on progressively deduced 1913 prices, the applicants paid in market prices that ranged from 3500 and 5000 Crowns for 1 ha based on the region and land fertility. This was a high price that excluded not only landless people but also capitally weak small and middle-sized acquirers. Even though the average daily wage in Czechoslovakia grew from 11 Crowns in 1919 to 31 Crowns in 1922, the average daily wage in agriculture remained significantly lower: 7.30 and 15.60 Crowns, respectively (Statistická příručka, Citation1925, p. 62). Even former large estate employees who received compensation for their dismissal due to the expropriation of the large estate on which they worked were not able to pay for an allotment of land. According to statistics, 66,277 former employees of large estates received compensation from the state, and only 37,569 of them were agrarian workers (Statistická ročenka, Citation1937, p. 66); the compensation, however, fluctuated between 2000 and 5000 Crowns per person.

The inability of the poorest applicants to obtain a land allotment was why, initially, the state introduced three types of credit (for assignment of, investment in, and running of a farm) and loans from the so-called Compensation fund. There were, however, considerable differences between acquirers: one hectare of land was cheaper for those who acquired larger allotments. These acquirers were able to get credit more easily and on better terms, and they had to pay just a tenth of the land price in advance, whereas minor applicants had to pay half of the purchase price. As a consequence, the average indebtedness for 1 ha reached 2500 Crowns within a few years (Otáhal, Citation1963, p. 202). In many cases, however, the loans were not invested in agricultural production and its modernisation but used instead for family, community and religious activities (Crampton, Citation1994, p. 35). The following figure describes the outcomes of the redistribution of the land ( and ).

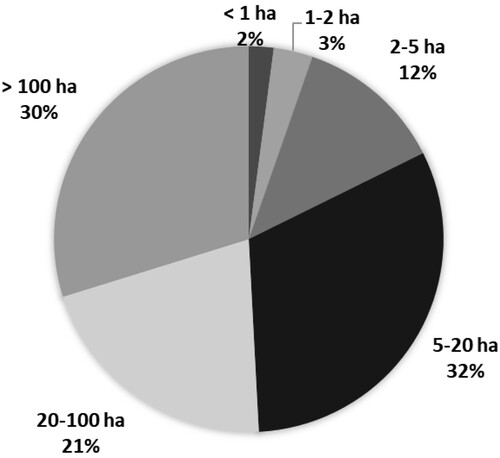

Figure 7 Division of the land in 1930 (according to seize of the tenure). Source: Calculation based on Otáhal, (Citation1963, p. 250).

Figure 8 Division of the land in 1930 (according to the number of owners). Source: Calculation based on Otáhal, (Citation1963, p. 250).

According to the 1930 statistics, large farms of more than 100 ha were owned by less than 1% of landowners who owned 30% of the entire land; as and clearly show, in 1906, the acreage above 100 ha was also owned by less than 1% of landowners who owned 38% of the entire land. Thus, large estates were not liquidated; only their ownership structure was changed – so were the names of some owners. The reason why large estates were not liquidated lies in residual estates and other large tenures. As already mentioned, the allotment act defined them as any acreage larger than 30 ha that would be economically depreciated by parcelling it out. During the 1920s and 1930s, several legal norms were adopted that allowed large farm owners to keep the land, when necessary from the perspective of cultural heritage or industrial purposes.

We have already seen that the hope of acquiring a residual estate was an irresistible incentive for Agrarians, including those who had criticised the land reform inside the Party previously, to support the land reform in the extension that jeopardised members of the Party. The fight for residual estates and other larger tenures fully began in 1922. Members of all political parties took part. The Union completely changed its focus to arranging the sales of sequestrated or expropriated large estates. As correspondence between members of the Union and headquarters of political parties reveals, the process of allocating expropriated land became very soon pervaded by clientelism and corruption. Under the title ‘residual estate’ the expropriated land was being given not only to members of political parties, MPs and senators but also to bank directors, distinguished entrepreneurs and other important persons. Usually, an officer of the SLO offered in his letter to a politically friendly applicant a ‘comfortable arrangement’ of the assignment of an estate: ‘ … a larger or smaller forest area might be added too, further a smaller castle with a park and a garden centre, or some other objects.’ The applicant had ‘only’ to send a proclamation that should he or she be ‘allowed’ to purchase the land, he would pay the officer ‘ … entirely voluntarily 2% of the arranging provision.’Footnote16 Two typical phases can be distinguished in such commercialisation of individual allocation cases.

First, a stock company was founded in the locality of a to-be expropriated estate with Agrarians, members of their local organisations, and the SLO-connected solicitors on board. Social Democrats often participated in these stock companies as well. The common practice was for the stock company to be established only after the approval of expected transactions by the SLO. Secondly, the stock company, as a straw man, quickly – because its members were very well informed – bought the land as sequestrated property for the 1913 price and subsequently sold ít under the title residual estate or other large tenure to an applicant chosen in advance. The stock company gained 1% of the market price commission.

In the first round of the allotment in 1922, besides half a million requests for small-sized allotments, commissaries received five thousand requests for residual estates.Footnote17 At the beginning of the 1930s, in the group of residual estates, 1,762 acquirers gained 196,905 ha (of this 170,993 ha was arable land), and 1,358 acquirers in the group of other larger tenure gained 588,791 ha of land (of this 28,578 ha was arable land) (Statistická příručka, Citation1932, p. 85). At the end of the land reform, 2061 applicants gained 2296 residual estates and 2277 applicants gained 2487 other large tenures (Statistisches Jahrbuch, Citation1938, p. 56). The numbers reveal that some applicants acquired more than one residual estate; moreover, in some cases, the acreage of the residual estates and other large tenure did exceed 2000 ha.

demonstrates the full picture of the land redistribution achieved by 1937. It shows, among others, the destiny of the non-allotted land (), including the entire acreage of the Habsburg family's confiscated land: it remained in the hands of the state and was nationalised. This land became the foundation of two types of state-owned enterprises – State Farms and State Forests (Doležalová, Citation2011b). In 1921, they owned and managed 605,596 ha of land, of which only 161,656 ha were the Habsburg family's estates (Statistická příručka, Citation1925, p. 62). In 1937, the State Farms and State Forests owned and managed 506,586 ha of land: 318,607 ha in the Czech part, 178, 384 hectares in Slovakia, and 9595 ha in Subcarpathian Rus. The entire acreage consisted of 38,146 ha of arable land (Statistisches Jahrbuch, Citation1938, p. 56).

Figure 9 Distribution of the expropriated land. Source: Calculation based on Statistisches Jahrbuch der Čechoslovakischen Republik [Statistical Yearbook of the Czechoslovak Republic], Prague (Citation1938, pp. 55–56).

![Figure 9 Distribution of the expropriated land. Source: Calculation based on Statistisches Jahrbuch der Čechoslovakischen Republik [Statistical Yearbook of the Czechoslovak Republic], Prague (Citation1938, pp. 55–56).](/cms/asset/d7302ac0-b54a-4eeb-8e92-110f90c80a00/sehr_a_1984295_f0009_ob.jpg)

The residual estates were owned by 1,470 owners in the Czech part, 564 in Slovakia and 27 in Subcarpathian Rus and represented 13% of the entire allocated land. Other larger tenures were allocated to 824 owners in the Czech part, 1,326 owners in Slovakia and 127 in Subcarpathian Rus and represented 44% of the entire allocated land.

Small-sized allocations represented an acreage that varied from 0.1 ha to 30 ha and were allocated to a very socially and economically heterogeneous group of farmers. In the Czech part, 413,747 small-sized acquirers received 456,161 ha in total; in Slovakia, 186,648 acquirers received 298,034 ha in total; and in Subcarpathian Rus, 34,261 acquirers received 131,958 ha (Statistisches Jahrbuch, Citation1938, 55–56). While 812 landowners owned more than 500 hectares of the land, 31,501 peasants had to farm acreage of less than 0.1 ha. During the reform, 344,225 applicants gained less than 1 ha of land. In 1935, the Minister of Agriculture Milan Hodža pointed out that, despite the ownership changes of 12.5% of the entire land in Czechoslovakia and the participation of 600,000 people in the process of the land reform, the hunger for land was not satisfied (Krajčovičová, Citation2009, p. 221).

Thus, the winners in the land reform in Czechoslovakia were not the poor and landless peasants. The real winner is hidden behind the residual estates and other larger tenures: Agrarian party. Its members gained a third of the whole number of residual estates and other larger tenures with a total acreage of 999,976 ha (226,609 ha of which was arable land). Moreover, by endless promises of allotment and the removal from expropriation, Agrarians shrewdly manoeuvered between the competing demands of landless and land-poor people, mid-sized farmers and landlords. Thanks to this strategy, the Czechoslovak Agrarian Party worked its way to become the most influential party in interwar Czechoslovakia; from October 1922 until September 1938, an Agrarian prime minister presided over 13 out of 19 Czechoslovak governments.

Factors of the change: in a trap of political, economic and national interests

Recent historiography has pointed out that a non-violent land reform fully succeeded only in the rarest of circumstances (Scheidel, Citation2017, p. 355). A survey of twenty-seven reforms that were realised during the second half of the twentieth century shows that in a large majority of cases (21% or 78%), land inequality remained largely unchanged or even grew over time (Scheidel, Citation2017, p. 353). The search for land reforms that were both peaceful and effective has not been particularly successful (Scheidel, Citation2017, p. 356). Until now, the Czechoslovak interwar land reform was considered a rare example of a non-violent successful land reform in historiography. While the previous chapter revised the results of the land reform in Czechoslovakia and showed that the land reform failed in expropriating and redistributing land to either the announced or the expected scale, this chapter explores three groups of factors that could influence this failure: the political environment, the level of industrialisation and the multinational character of the state. I point out, that under the pressure of these factors the land reform in Czechoslovakia changed its nature from a tool that should have rectified an unequal division of land into a tool fortifying the power of the newly-established economic-political elites.

(1). The evolution of the political environment. The structure of both the Assembly and the first governments in Czechoslovakia consists of seven political parties in a ratio that corresponded to the last pre-war election results in the Czech part of the country. Until 1926, the political scene in Czechoslovakia was represented by a broad governing coalition, in which any decision was of a quid pro quo nature. Any political decision was made behind the closed doors of non-formal institutions, primarily by Pětka [the Five]; i.e. the leaders of the five strongest political parties (rightist Agrarian Party, National Democratic Party, and People's Party, and leftist Social Democratic Party and National Socialistic Party) and not in the Assembly or Parliament meeting room (Broklová, Citation1992). The land reform was not an exception (Balcar, Citation1998, p. 395). Socialisation, with land reform as its crucial element, became part and parcel of Czechoslovak economic policies not only under the pressure of social tensions of the time, the surrounding narrative of which emphasised a defense against the import of Bolshevism from Russia into Europe. There was another factor of the same importance: the necessity to achieve a political compromise between Social Democrats and Agrarians. The breaking point was less the sequestration and expropriation of the land than its allotment. Through the 18-year-long phase of redistribution of the land, the Agrarians acquired not only political capital but also tangible capital in the form of estates that they gained through the clientelism and corruption that accompanied trading with expropriated land with no regards to the real needs of peasants. This fact had, in my view, at least two far-reaching consequences that confirm the hypothesis, that even with a strong ruling agrarian political party and no opponents to land reform, there is no guarantee of the successful realisation of land reform in a country.

First, the clientelist nature of the land reform institutions. Control of the land reform was in the hands of the SLO and its local committees, which reflected the relative strength of the individual political parties in the Assembly and then in the Parliament. Decisive positions were occupied by Agrarians who held, as we have already mentioned, not only the position of the SLO Chairman and the position of Minister of Agriculture; from 1922 on, Agrarians held the position of the prime minister as well. During the expropriation and allocation of the sequestrated land, formal rules were superseded by informal negotiations within the newly formed social networks. These networks were defined by common economic interests and crossed the borders of political membership and national allegiance, as correspondence between the members of the Union demonstrates. Political parties even created special land departments that focused exclusively on arranging the sale of expropriated large estates into the hands of their clientele.

Second, the changing political culture of the country. Based on an analysis of the political parties’ programme priorities (Doležalová, Citation2008) and the acts individual parties proposed in Parliament, I argue that during the implementation of the land reform acts, the Social Democrats forgot that their goal was the creation of cooperatives in collective ownership, and the Agrarians forgot that their motto was the ‘countryside is one big family.’ Since one cannot serve two masters at once, when choosing between the national and private interest, the representatives of the new Czechoslovak political elites picked up their private interests. From the Agrarian perspective, the initial idea of agrarianism as a love of the native soil gradually gave way to the interests of those who rose through the party hierarchy into the political power structures. These people became duty-bound to their party. They had to sign a declaration that they accepted their parliamentary posts or positions in the state offices and managing boards of various SOEs only thanks to the party; that they would comply with its rules; that they would give up their mandates and positions when they requested to do so by the executive committee of the party; and, with their mandate, they would automatically lose all other positions to which they had been appointed.Footnote18 The possibility of losing the acquired residual estates, however, always represented a threat, since the SLO could at any time take advantage of the act on the management of assigned farms and take the land away in any way the party saw fit.

(2). The level of industrialisation. Already in the time of its establishment, Czechoslovakia was an industrialised country; only 38% of Czechoslovak inhabitants worked in agriculture. However, Czechoslovakia inherited the imbalanced economic development of the western and eastern part of the Monarchy: the Czech part was economically considerably more highly developed than Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus. Before the Great War, the per-capita national income of the Bohemian Lands was 118% of the European average (Lacina & Hájek, Citation2002, p. 13). However, the decisive share of capital value of the industry in the Bohemian Lands was in the hands of German and Jewish entrepreneurs (Urban, Citation2003, p. 62); Czech entrepreneurs controlled approximately 20–30% of it and dominated only in agricultural industries (Urban, Citation2003, pp. 57–60), in which the business interests of Agrarians and their supporters including the Agrarian Bank (CitationNovotný & Šouša, 1996) were anchored. This fact had, again, two far-reaching consequences.

First, this is why the Agrarians supported agricultural entrepreneurs more than peasants and never actually changed their programme priority to equalise agriculture with industry. They never altered their conviction that only large estates with their agricultural production could fulfil this aim. As their contemporary newspapers Venkov and Role show, they pretended just for a short period of time that they wished to attract peasants, as they needed their votes before 1921 when the Social Democratic Party was significantly stronger than they were. After the Communist rift, the strength of the two parties was balanced, and a quid pro quo strategy allowed the green-red coalition to govern comfortably.

Second, the situation allowed the Agrarians to fortify their entrepreneurial interests not only in industries connected with agriculture but also in the banking sector, in heavy industry and the arms industry and to create a large consortium of companies in the various industrial branches under the umbrella of the Agrarian Bank. As a consequence, the influence of the Agrarians on the shaping of economic policy was decisive during the entire interwar period (Lacina & Slezák, Citation1994). According to their programme statements, all the Czechoslovak governments promised to support small tradesmen and farmers, as well as industrial production. On the other side, they protected agricultural workers in only limited measure. When the lowest social groups in agriculture did not get a sufficient amount of land to secure their economic independence, they either suffered insolvency within a few years or were pauperised. Both groups found themselves in a state social network that was insufficient to help them; there was an increase in the army of unemployed in agriculture that the industry could not absorb quickly enough. According to the Act on State Support in Unemployment (Act no 63 of 10 December 1918), employees in agriculture had no right to state support. The Ghent system did not change the situation significantly. In the second year of its implementation in 1926, on average, the state supported 34,035 unemployed monthly; only 127 of them worked in agriculture (Statistická příručka, Citation1928, p. 365).

(3). The multinational character of the state. The common legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy throughout the newly established states was a multinational population structure. In Czechoslovakia, minorities formed 33% of the entire population, of which the German minority accounted for 25%. Thus, Czechoslovakia had a very mixed population from the point of view of individual nationalities, which were structured quite differently socially and participated differently in various social activities. As far as the Czech population was concerned, the majority were workers in the manufacturing industry. This was even more noticeable among those of German and Polish nationality. Among the Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians and Hungarians, the number of those engaged in agriculture was clearly the highest. The proportion of agricultural labourers in the total workforce was larger in the eastern part of the republic than in its Czech part. However, representatives of the minorities (including the Slovaks) did not participate either in the legislative or executive bodies that introduced, implemented and controlled the land reform in Czechoslovakia; among 1100 employees of the SLO, we can only find one German (Jančík, Citation2011, p. 74). The multinational character of Czechoslovakia had a significant influence on the nature of the land reform. After the introduction of the expropriation act, the original narrative of the land reform as a tool of economic and social necessity that would solve the hunger for the land, depopulation of the countryside and unemployment in cities, was replaced by the narrative of the land reform as the core of the national fight for freedom through which the land had to be returned to the nation from whom it was stolen 300 or 900 years before, respectively. The metamorphosis of the narrative was orchestrated by the Agrarians who recognised that an emphasis on the national struggle could hide the real motivations of the main players. Thus, the Czechoslovak land reform shows how an appeal to national interests can be used to push through very personal interests (Doležalová, Citation2006). It had at least four far-reaching consequences.

First of all, the nationalist rhetoric significantly influenced the scale of the announced expropriation and the measure of redistribution. During 1919, the original intention of political parties to carry out rectification of social inequality in agriculture through colonisation was moved to the much broader concept of the land reform. The difference was fundamental and is oftentimes overlooked. Colonisation supposed the creation of settling committees and widening the possibility of gaining a mortgage loan so that every new applicant could get as much land as he or she needed for his or her livelihood. Even in March of 1919, when the question of land reform began to be negotiated in the Assembly, politicians, as well as the public, spoke about colonisation.

Secondly, according to the expropriation act, the nationality of the original owners was irrelevant. Expropriation was defined by the extent of the possession. However, the large estates that were to be expropriated were owned by aristocrats who were defined by their nationality – in the Czech part of Czechoslovakia as Germans, in the Slovak part as Hungarians. Nationalist rhetoric also allowed the introduction of progressive deduction of compensation that affected the largest landowners the most. Thus, the nationality of owners did significantly affect the extent of the land reform; this aspect can be demonstrated not only in Czechoslovakia but also throughout Central and Eastern Europe. When the nobility of a nationality other than that of the majority owned large estates, the expropriation was on a larger scale, as the land reforms in Czechoslovakia, Latvia and Estonia prove (Albertus, Citation2015, p. 55; Doležalová, Citation2015, p. 55). On the other hand, in Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary, where the large farm owners were of the same nationality as the majority, less land was expropriated, and the land reform was on a minimal scale, except for the eastern parts of Poland with Ukrainian and Belarusian landowners (Doležalová, Citation2015, p. 55).

Thirdly, according to the allotment act, the nationality of applicants played no role. In fact, the German minority received a total of 4.5% of all distributed land in Czechoslovakia (Cornwall, Citation1997, p. 264). In Silesia, where Poles and Germans had a significant majority, 19 residual estates and 2217 minor allocations were assigned. Only six of the assignees were either Poles or Germans, and the entire acreage of their allocations was 5 ha; the others were Czechs (Rychlík, Citation1996, p. 28). A similar situation was in the allotment proceedings when parcelling out large estates in the linguistically mixed Czechoslovak borderlands, where Germans acquired only 28% of small-sized tenures (Cornwall, Citation1997, p. 264); the same amount of land was given to Czech and German applicants only in the cases of buying out long-terms leaseholds (Jančík, Citation2011, pp. 327–330). German acquirers gained only 15% of residual estates and other larger tenures. Thus, the land reform became a tool for spreading Czech settlers into areas that had been German, Hungarian and Polish, but also Slovak. It was exactly for its nationalist character that it was financially supported by the government (Miller, Citation2003).

Finally, the primary goal of the nationalist rhetoric was to ostracise foreign landowners as the main enemies that had to be punished (Pekař, Citation1923, p. 34). There is no doubt that appealing to national awareness became a tool for the social mobilisation of the masses to the support of the land reform. However, it also ostracised the ‘inconvenient’ original owners and helped to establish new economic elites in Czechoslovak agriculture. From a long-term perspective, the anti-landowner rhetoric promoted the stereotype of the owner as evil and hence, in my opinion, paved the way for more radical interventions into the private ownership that were about to show their Communist face a few years later.

Conclusion: revolutionary pragmatics

The land reform in Czechoslovakia was introduced immediately after the state was established on the ruins of Austria-Hungary on 28 October 1918. The challenge to break from the Austro-Hungarian economy and fully realise the newly acquired independence and sovereignty was accompanied by an attempt to escape the negative consequences of the war. The land reform became a powerful tool in this struggle. In the Czechoslovak land reform, one-quarter of the land in the country was sequestrated, but only one-half of it was subsequently expropriated, and only three-quarters of the expropriated land was actually allotted. Less than one-half of the allotted land was allotted to small-sized acquirers with land acreage between 0.1 and 30 ha. However, even the smallest acquirers varied as they included not only landless and land-poor people but also mid-sized and large landowners. Fifty per-cent of the sequestrated land was given back to the original owners. Large estates were not liquidated; only some original landlords were replaced by new ones. The hunger of the landless people and land-poor people for land was not satisfied to the degree they expected.

The mobilisation of rural inhabitants for the support of the land reform was but a strategy of political agrarianism, the target of which was the redistribution of political power. National agitation became a powerful tool in the hands of the bureaucratic apparatus and various interest groups with connections in the entire political spectrum. For the Agrarians, the land reform was an ideal tool for shifting the public focus onto agriculture. The pragmatism of the Agrarians explains why they shifted their strategy and why they changed the name of their party during the course of the land reform, why the multinational character of the state was extensively disregarded in the course of the redistribution of the land, and why the peasantry was somewhat overlooked.

The answer to the question of why the land reform in Czechoslovakia failed in removing the unequal division of the land and solving three burning social questions: the landless and land-poor people's hunger for land, the depopulation of the countryside, and unemployment in cities, lies in the fact that the land reform became a political game of the first order. Not only Agrarians and Social Democrats but also MPs and senators of various political parties participated in this game. So did their friends among businessmen, state officials and, last but not least, large landowners. These players transformed the land reform from being a tool of rectification in an unfair allocation of land, to being a tool of the redistribution of economic power and the reinforcement of a political domain. By these means, the land reform was stolen from the peasants in a calculated theft.

The Czechoslovak land reform teaches us that a successful and strong Agrarian party does not guarantee the land reform in favour of landless and land-poor people even though such a land reform is anchored in legislation. The decisive factors were: a young democracy in which the rules of governing were not yet internalised; the multinational character of the state in which the nationalist rhetoric could be abused; calculated and manipulative interventions into the land reform process accompanied by a high level of corruption and clientelism; lack of financial resources among peasants and agricultural workers; and the level of industrialisation.

As a consequence of political, economic and national factors, from the short-term perspective the reform failed, while also creating long-term dependency. The Communists were the only political party that did not take part in described clientelistic networking. When their moment came after the liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945, one of their slogans was to correct the wrongs of the first land reform, give the land to the people, and punish traitors. They nationalised all landed property in the country through forced collectivisation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Available from http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/tisky/t0003_00.htm. [Last opened on 13 August 2020]

2 Available from http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/tisky/t0320_00.htm. [Last opened on 13 August 2020]

3 Available from http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/stenprot/014schuz/s014002.htm [Last opened on 15 August 2020]

4 Available from http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/stenprot/014schuz/s014002.htm [Last opened on 15 August 2020]

5 Available from http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/tisky/t0680_00.htm. [Last opened on 13 August 2020]