ABSTRACT

The article focuses on masculine consumption patterns and the production and dyeing of textiles in rural Finland in the early nineteenth century. It maintains that the rural consumption of textiles as well as individual choices and tastes evolved, and our selected examples of males’ wardrobes demonstrate that contemporary styles were followed. The article targets an era that can be regarded as a watershed: this was a time when mass production was in its infancy and craft production and self-sufficiency were still relevant to household economies. As the wealth of certain groups, particularly landed peasantry, increased, they began among other things to purchase and wear clothes dyed with imported dyes such as indigo. The presence of blue garments in the wardrobes of the common people testifies to a change that took place in rural Finland. This change is evident especially in our analysis of probate inventories of the male inhabitants. Variety of documents on artisanship, the textile and dyeing industry and the import of indigo dye to Finland provide further evidence. The research thus contributes to the discussion on changing consumption patterns among the rural inhabitants in a country that is usually seen as one to which industrialisation came late.

1. Introduction

In early summer 1810, a young pharmacy student, Carl Fredric Hellsten, submitted a petition to the newly formed Finnish Senate, asking the authorities to return to him 50 skålpund (some 21 kilograms) of indigo dye confiscated in the port of Turku (Åbo in Swedish), then the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Hellsten had purchased the dye from Stockholm and organised its shipping to Finland together with his business partners. The cargo was confiscated because of the restrictions of the Continental Blockade, which limited the import of colonial goods from Sweden to Finland during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). The confiscation almost ruined the business venture, but eventually the seizure was cancelled, and Hellsten was able to retrieve his indigo dye and allowed to retail this commodity.Footnote1

The above-mentioned case concerning the import of indigo dye is one of the signs indicating a change in consumption patterns and taste in the early nineteenth century. In this article, we examine how the textile and especially dyeing industry developed in Finland. We also shed further light on the import of indigo dye to Finland and ask, how the use of the colour blue was reflected in the clothing of rural men in particular. By studying the above mentioned questions, we aim to show, by what means the dyeing industry was able to satisfy the demand of the rural population for dyed textiles in the early nineteenth century. Consequently, we examine the whole production chain, starting from the import of indigo dye for the dyeing industry and finishing with the ownership of blue garments. We have conducted a case study of one parish in southern Finland in order to analyse more closely the production and ownership of blue textiles. This parish, Hollola, represented a large and prosperous peasantFootnote2 community and has been regarded as a region that was receptive to innovations – particularly in the form of new and fashionable clothing (Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, p. 17, 200–203). There were also a few small manufactories focusing on textile production and dyeing in this region that constituted the local supply of dyed textiles.

By focusing on the spectrum of production as a whole, we aim to respond to the problem of production-centeredness in economics raised by Jan de Vries (Citation2008, p. 9; see also Roche, Citation1994, p. 8), among others. Supply and demand constitute a pair that need to be addressed together: production and consumption are conceptually and factually related and intertwined. The idea of an ‘industrious revolution’ developed by de Vries serves as a starting point of our study and provides us with a wider perspective. We are also aware of a growing interest in pre-modern consumption research: economic growth and the expanding markets of consumption have received considerable scholarly attention since the early 2010s. Concepts like the industrious revolution (see especially de Vries, Citation2008Footnote3), the European marriage pattern (e.g. de Moor & van Zanden, Citation2010; Dennison & Ogilvie, Citation2014) and Great and the Little Divergence (de Pleijt & van Zanden, Citation2016) have been used to explain changes in consumption. Even so, the underlying reasons behind these changes and developments are still widely discussed. We aim to contribute to this discussion by taking Finland as an example, as it is usually considered a country that developed slowly economically.

Clothing is a key issue in studying consumption (de Vries, Citation2008, pp. 138–139). In this article, we have focused on blue clothing, as the colour had a special significance in the early modern world (Pastoureau, Citation2001). Especially indigo dye and the colour indigo blue offer a fruitful example for a case study, although the colour blue was also produced by using woad grown in Europe (Nieto-Galan, Citation2001, pp. 17–19; Runefelt, Citation2015, pp. 110–117). The fact that indigo was an imported colonial commodity added its prestige. As a valuable substance, it was often confined to use by professional dyers, a fact that increased the value and appreciation of blue clothes (Alm, Citation2016, p. 51; Runefelt, Citation2015, pp. 109–110).

In this article, we examine men’s wardrobes (revealed in probate inventories) and also focus on a few court cases in which blue fabrics are mentioned. Consumption habits of rural men have received less attention as the focus has mainly been on urban settings (e.g. Breward, Citation1999). Additionally, women’s clothes have received (and still receive) more attention but we concentrate on the clothing of peasant men because it was usually the men who had the most valuable clothes in the household. Moreover, their outerwear was often bespoke garments made by a guild or parish tailor, while women’s clothes were typically homemade (Ulväng, Citation2012, p. 253; Uotila, Citation2019, p. 118). Generally, a person’s appearance was a sign of his/her position or social group in society (Wirilander, Citation1974, p. 45; Roche, Citation1994, pp. 5–6; Runefelt, Citation2015, p. 125).

Our attention is devoted to production, consumption patterns and changes in material culture in a rural environment because at the beginning of the nineteenth century the majority of Finnish people lived in the countryside. Owing to a rise in the standard of material living in rural areas, there emerged potential consumers whose opportunities to engage in commercial activities gradually began to increase. However, the available options were still rather limited, as in accordance with mercantilist policies, commerce and certain craft trades were concentrated in the towns – it was only in the 1860s that the economic legislation was relaxed and, for example, retail shops were allowed to open in rural areas (Alanen, Citation1957; Nevalainen, Citation2016, p. 19; Wassholm & Östman, Citation2021). On the other hand, the concentration of production exclusively in urban areas was not altogether successful in this highly rural country as certain industrial units were established in rural environments, and craft trades were also widely practised in rural areas.

We study the emergence and development of a consumer culture that was not based purely on mass production and/or mass consumption (Nyberg, Jonsson, Fagerberg, & Lindberg, Citation1998, pp. 86–87). In other words, we target a period when mass production was in its infancy and craft production and self-sufficiency were still relevant to Finnish household economies, albeit gradually losing their formerly strong foothold (Hjerppe & Jalava, Citation2006). In practice, the research covers the period from 1809 to the early 1850s. In 1809 Finland came under Russian rule after the Russo-Swedish war, and over time the existing cultural, social and economic ties with its former mother country, Sweden, gradually loosened.

Studies on consumption in Finland have generally focused on the post-war period (e.g. Ahlqvist, Citation2008; Heinonen & Peltonen, Citation2013). Previous research has paid little attention to the consumption behaviour of the rural population in early-nineteenth-century Finland. However, the patterns of peasant consumption in late-nineteenth-century Finland have received some attention in scholarly publications (e.g. Kuusanmäki, Citation1936; Heikkinen, Citation1981; Citation1986; Citation1997). On the other hand, the existing research suggests that the picture of the peasant population’s consumption is more complicated, and that their self-sufficiency was gradually decreasing, especially in western and southern Finland (Laurikkala, Citation1947; Uotila, Citation2014, pp. 325–328). Conversely, the consumption choices of the higher social groups have received more attention in Finnish historiography over the last decade or so (e.g. Ilmakunnas, Citation2009; Citation2012; Citation2017; Ijäs, Citation2015; Citation2017).

Our study has especially benefited from the findings of research focusing on the textile and dyeing industry as well as research on the history of clothing and sartorial culture. In his studies on the development of industrial production, Per Schybergson has provided detailed estimates of the production of various consumables over several decades in nineteenth-century Finland. He has also collected data on industrial production facilities, the workforce and recorded the numbers of both urban and rural artisans (Citation1973; Citation1974a; Citation1974b; Citation1980; Citation1992). In the case of the clothing of the rural population in Finland, we use two works in particular as reference material: the seminal research by Lehtinen and Sihvo (Citation2005), which provides an overall picture of folk costumes, and T.I. Kaukonen's work on the same subject (Citation1985). In both studies, both museum collections and probate inventories were employed.

In the following, we first look at the points of departure for this article (research methodology and source material). Then we consider the consumption opportunities and forms of production that existed in rural Finland. The import of indigo dye is studied in the following section, and after that, our attention is paid to early textile factories, thus the focus is mainly on small-scale production. The latter part of the article focuses on the consumption of blue-dyed garments and concludes with a discussion section.

2. Materials and methods

We have consulted a variety of sources because we study consumption in a time period when consumption opportunities, like engagement in retail trade and various other business activities, were regulated, and there were no statistics on consumption or consumer surveys. Therefore, we have used import statistics (the Sound Toll Registers), official permits granted to rural production facilities (that among other processes were capable of dyeing textiles), probate inventories (in the 1830s), as well as court records and contemporary newspapers.

The following research emphasises qualitative methods, but also quantitative analysis is conducted whenever the source material permits. The close reading of the source material allows us to provide a multifaceted picture of early modern consumption in a rural community. The selection of the source material and our research methods are more closely connected to the perspectives employed in business and economic history than those usually employed in the history of fashion.

In order to understand the development of textile production and the dyeing industry and to set it in a transnational framework, we study the importation of indigo dye to Finland through the Sound, the strait between Denmark and Sweden, where the Danish Crown collected a toll from passing ships. The Sound Toll Registers include information on about 1.8 million passages in or out of the Baltic Sea from 1497 to 1857. They have been compiled and published in a digital database (STRO), in which it is possible to use the Sound's customs statistics to search for information on cargoes imported to various ports in the Baltic Sea region, including Finnish ones (Gøbel, Citation2010; Scheltjens & Veluwenkamp, Citation2012). The customs statistics also contain information on the composition and volume of the cargoes, but since these figures were provided by the captains of the ships, the amounts may have been underreported. The registers also allow us to ascertain to which ports the indigo dyes were destined but not to whom or how they were distributed. It must be noted that these statistics do not reveal the whole situation in the period under our scrutiny: they do not include imports to Finland from ports in Sweden and elsewhere in the Baltic Sea region or illegal trade.

In order to investigate the establishment of new production facilities, we take a closer look at the petitions and appeals submitted to the highest national decision-making organ, the Finnish Senate, concerning the textile and dyeing industry. In early modern Finland, the establishment and expansion of production units in urban and rural areas was contingent upon obtaining official permission (privileges), and the same applied to engagement in craft trades in rural areas (Paloheimo & Uotila, Citation2015). The studied documents include petitions to establish new industrial facilities or to expand the production of existing ones. The data collated for the purposes of this study are sampled from a very wide archival collection: from 1809 to 1850, over 30,000 petitions and appeals were submitted to the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate. These letters were recorded in the so-called Registers of Petitions and Appeals of the Economic Department. For the closer research, recorded entries of almost 6,600 cases were scrutinised in every fifth year between 1810 and 1850 over nine reference years. A careful study revealed that of all these applications 871 (13 percent) were business-related and submitted by a business actor or a collective of business actors (Paloheimo, Citation2012, pp. 37–38). Of the sampled applications, 66 cases (20 percent) concerned the textile and dyeing industry. The rural textile and dyeing industry was concerned in 38 cases, and these constitute the focus of this research.

In addition, we focus on examining the consumption of rural inhabitants in the parish of Hollola and conduct an analysis of selected probate inventories from the 1830s. This particular decade was a difficult time both economically and epidemiologically, with various epidemic diseases ravaging the community (Kuusi, Citation1937, pp. 79–80; Uotila, Citation2014, p. 93, 319–320). This is reflected in mortality, with many young and middle-aged men dying prematurely, leaving behind them property that had not yet become worn out and worthless. Thus, it can be argued that these data reveal actual consumption and clothing assets more accurately than analysing the wardrobes left behind by older men – in which case the clothing may have already been worn out. Another practical reason for analysing this decade is the fact that it is only from this point on that the documents form a complete series.Footnote4 We analyse what kind of clothing was listed in the probate inventories of male members of local peasant families in the parish of Hollola, paying particular attention to outerwear and coats. Some fifty probate inventories were examined in greater detail. This figure does not reflect the total number of deceased during the 1830s and is in fact considerably lower. Although drafting a probate inventory was a legal requirement, in some cases no probate inventories were made because of the low value of the belongings, or the inventories were not submitted to the authorities at all. In either case, the probate inventories are often considered as biased source material (Roche, Citation1994, pp. 17–18; de Vries, Citation2008, pp. 123–124; Hemminki, Citation2014, p. 271).

In addition, with the help of the Finnish National Library’s digital newspaper service we have searched relevant newspapers for keywords meaning ‘indigo’, ‘colour’, ‘dyer’ and ‘textile factory’ (indigo, färg, färgare, kläde fabrik in Swedish).Footnote5 However, the search functions of the digitalised materials are not without fault, especially when old-fashioned fonts like Fractur, which were commonly used in newspapers and which the search engine has difficulties in recognising, have been used. Therefore, in this case no quantitative research has been conducted. The consulted material provides additional qualitative evidence on the development of the rural textile and dyeing industry and the use of blue in the early nineteenth century and further reinforces our arguments. Similarly, we have also consulted the court records of Hollola Parish for cases related to the dyeing of textiles.

3. Limited consumption opportunities for the rural population

A rapid population growth was one of the most important factors contributing to the development of Finnish society in the nineteenth century: in 1800, the Finnish population numbered one million, but by the mid-nineteenth century this figure had grown to 1.6 million (Voutilainen, Helske, & Högmander, Citation2020). The population growth did not have a direct influence on the demand for consumer goods or the services of professional artisans as the major growth took place among the lower social groups (mainly the landless rural population), who had a low standard of living and fewer opportunities to consume. On the other hand, the accumulation of wealth among the middle groups of society, including the landed peasantry, opened more consumption opportunities for them.

The level from which consumption in Finland started to grow was fairly modest compared with the situation in central parts of Europe (e.g. de Vries, Citation2008; Ogilvie, Citation2010; Dennison & Ogilvie, Citation2014; de Pleijt & van Zanden, Citation2016). The rural population in Finland at the time has been regarded as largely self-sufficient. Traditional ethnological studies in particular have highlighted the peasants’ dexterity and self-sufficiency (e.g. Talve, Citation1979; Vilkuna, Citation1953), with iron and salt the only products that peasant households needed to purchase. The findings offered in previous research are to a considerable extent convincing as country folk could make ordinary clothes and shoes, and women in particular sewed their own clothes as a regular household chore (Wottle, Citation2008, pp. 30–31). On the other hand, purchasing commodities or ordering products from professional artisans eventually became more popular. The fact that the garments were made to measure and had to be ordered in advance from tailors (Wirilander, Citation1974, p. 49; Wottle, Citation2008; Riello, Citation2020, p. 17) limited consumption opportunities in both rural and urban areas. Tailors made superior men’s clothing and finery for women. This is reflected in the growing number of artisans, which, especially in southern Finland, had been increasing since the 1750s and peaked in the nineteenth century (Uotila, Citation2014, pp. 109–112).

There were several factors that curbed the peasants’ consumption and encouraged them to remain as self-sufficient as possible.Footnote6 Owing to the mercantilist policies in practice, the right to engage in commerce and craft trades was restricted to town dwellers, and thus the towns developed into centres of these activities. Retail shops were not permitted in the countryside, and thus rural inhabitants had to travel long distances to the closest town in order to buy various goods (sugar, salt, coffee, tea, fabrics, etc.). On the other hand, there were annual countryside fairs, where rural inhabitants could purchase products that town merchants had brought for sale. In addition, itinerant peddlers sold small goods such as haberdashery and fabrics to the rural population. Although this trade was forbidden by law, rural dwellers in distant villages favoured the peddlers, who provided them with a wide variety of consumer goods (Nevalainen, Citation2016; Wassholm & Sundelin, Citation2018).

In addition, fabrics could be purchased directly from producers as they had their own outlets (Wottle, Citation2008, pp. 24–25). For example, a well-known rural broadcloth factory in Littoinen (Littois in Swedish) near the city of Turku had its own shop in the city centre selling textile products and buying wool from local producers. In general, the products of large-scale facilities were sold by merchant houses and individual merchants in various towns. Littoinen had over 90 wholesalers in Finland in the 1850s (e.g. Koskelainen, Citation1923, pp. 158–159; Leinonen & Talanterä, Citation1987, p. 25). A wide variety of fabrics was available in blue and several other colours according to advertisements published regularly in the newspapers.Footnote7 The most frequently sought service of the factory was the dyeing of customers’ fabrics, and the most popular colours in 1850 were blue, black, dark green and grey (Koskelainen, Citation1923, p. 161).

Various European countries passed import bans and sumptuary laws to restrict the use of foreign-based products (Riello, Citation2020, pp. 27–34). Here again, in accordance with mercantilist economic policy, the state sought to protect and develop its own production (Heckscher, Citation1953). In early modern Finland, the rural population was encouraged to curb consumption and wear homemade clothing. These sartorial practices created social order as there was a close connection between appearance (clothes) and social status, particularly with regard to the fabric, cut and colour of clothing items, although the actual garments themselves might be the same (Wirilander, Citation1974, p. 45; Roche, Citation1994, p. 39; Alm, Citation2016, pp. 47–58). Societal reasons thus created a different consumer culture for different estates. For example, in the 1790s there was a nation-wide debate about how the rural population should dress. In many parishes, dwellers promised to abandon foreign products such as silk and velvet and to use only home-dyed products because factory-dyed clothing was denounced as a sign of vanity (Kuusi, Citation1937, pp. 325–327; Runefelt, Citation2015, pp. 107–110, 121–128; Alm, Citation2016, pp. 50–52).

The sumptuary laws were abolished in Finland in the 1810s, much later than in many other European countries (Jahnsson, Citation1904; Murhem & Ulväng, Citation2017, pp. 200–201; Uotila, Citation2019, p. 120). Nevertheless, expensive and pretentious outfits continued to incur disapproval, especially among the lowest social groups (for whom investing in dress was seen as a vanity). In addition, certain kinds of clothing – including those dyed blue – were long regarded in contemporary newspaper writings as an unnecessary luxury for the common people (cf. Riello, Citation2020, pp. 101–106).Footnote8 However, these writings did not fully coincide with how the population actually dressed, and contemporary attitudes towards the appearance of peasant men were more permissive, especially in western Finland (Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, p. 17), where people’s attire and consumption followed contemporary style. This was reflected, among other things, in people following European fashion trends and the introduction of new styles of garments such as fashionable coats and in the use of dyed clothes. However, Finland was not a homogenous country: in eastern Finland, the use of traditional clothing, including loose, homemade and undyed garments, persisted (Kaukonen, Citation1985, p. 252; Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, p. 17, 200–203).

4. Various forms of production in rural Finland

In early modern time, the production of various goods (outside households) in rural areas can be divided into two categories: traditional craft trades and production in small- or large-scale production facilities, so-called manufactories. The difference between ‘artisanal’ and ‘industrial’ units was often vague and artificial – both used labour-intensive production methods as machinery was rare, and thus the role of craftsmanship was stressed (Nyberg, Citation2000. See also Bruland, Citation1989). Most of these manufactories were small-scale facilities: they were, in practise, workshops with a workforce consisting of a master and his assistants. They also employed the traditional master-journeymen-apprentice system (Söderlund, Citation1949, pp. 205–209; Schybergson, Citation1980, pp. 410–411). There were only a few large factories operating with a wider division of labour.Footnote9

In the context of early modern Finland, the most important difference between the sectors was institutional. Crafts and manufactories operated under different legal frameworks: crafts within the guild-system or as parish artisan institutions, while manufactories had their own legislation. In addition, the licences required for operation were granted by different authorities – the establishment and production of industrial facilities were controlled by the Finnish Senate and the so-called hallmark courts (Lindeqvist, Citation1930, pp. 135–136; Paloheimo, Citation2012, p. 97), whereas the permits of rural artisans were decided upon at the local and provincial levels (Ranta, Citation1978; Uotila, Citation2014, pp. 122–134).

During the first half of the nineteenth century, an increasing number of manufacturers and various small-scale businesses were located in rural areas, outside the town borders, where they could secure the natural resources − such as forest raw materials, certain soil types or waterpower − required to set up industrial facilities. In urban areas these were often not available (Annala, Citation1928, p. 328). For instance, dye houses needed extensive amounts of clean water and firewood (Bergström, Citation2013, pp. 52–62). However, although the Finnish countryside had plenty of natural resources, it was not so simple to set up a manufactory focusing on dyeing in the countryside as dyers could not apply for formal parish artisan licences, and privileges for individual dye houses were rarely issued. In practice, they had to establish a broadcloth manufactory in order to operate in countryside (Schybergson, Citation1992, p. 87). This issue is discussed in detail below.

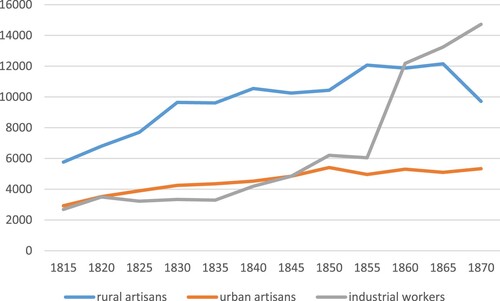

Although industrialisation was advancing in Finland during the early decades of the nineteenth century, many sectors remained in an undeveloped state, and artisanship continued to be a viable trade. Rural artisans, who were controlled by the parish artisan system, in which an artisan enjoyed a certain formal status, including a licence to work, and was obliged to pay special handicraft taxes, were more numerous in the nineteenth century. The spectrum of trades was greater in towns, where the guild system prevailed. In order to protect urban crafts, only a few (the most needed) trades were recognised by the law: blacksmiths, tailors and shoemakers. The craft trades, particularly rural artisans, made an important contribution to the production of consumer goods during the nineteenth century as is demonstrated in , which plots the numbers of industrial workers, town artisans and rural artisans from 1815 to 1870 (Schybergson, Citation1974b).

Figure 1. Industrial workers and artisans in Finland 1815–1870. Source: Schybergson, Citation1974b.

Rural artisans were more numerous than urban artisans, whose number was more stable owing to the restrictions imposed by the craft guilds. As the figure further shows, it was not until the mid-1850s that the number and importance of industrial workers increased significantly. However, in the first decades of the century, new facilities were already being established in growing numbers, and as their production gained in volume, it began to replace the existing production in households or artisans’ workshops. A phase of rapid growth in domestic industries took place in the latter part of the nineteenth century, although certain sectors – especially the textile and metal industries, which were strongly supported by the government – had begun to grow earlier (Kuusterä, Citation1989, p. 200). Globally, the textile industry, and the cotton textile industry in particular, developed early into large-scale production thanks to technical innovations and mechanisation (Mokyr, Citation1990, pp. 100–103).

In Finland, the textile and dyeing industry was the sector that employed the greatest number of industrial workers in the first part of the nineteenth century: for example, in the early 1840s, 44 percent of the workforce was employed in this sector (Hjerppe, Citation1979). The highest number of workers was employed by the cotton textile industry, and the development of this particular sector explains the rapid increase in the size of the industrial workforce in the 1850s (Schybergson, Citation1973, p. 113). The biggest employer in this industry was Finlayson & Co in the town of Tampere (Tammerfors in Swedish). However, the biggest broadcloth factories were also important employers (see below). The position of the cotton mill as the top employer reflects the growth of the cotton industry that took place in the nineteenth century along with changes in technology (Berg, Citation1994, pp. 40–42).

Rural consumption was also boosted by a growing number of artisans, which was enabled by allowing new occupational groups to apply for parish artisan rank. For example, after 1824 tanners, carpenters, hatters, clockmakers, just to mention a few, could apply for recognition as parish artisans. The case study of Hollola Parish allows us to study the situation in more detail. Often the development was related to population growth, but this alone does not suffice to explain the increase in the number of artisans (Uotila, Citation2014, pp. 116–117). Therefore, it is better to compare this number with the number of peasant households rather than with the population as a whole because the proportion of the landless was high, and they are not considered to have been the main customers of artisans. shows that, over the time studied here, households had more artisan services available, but there were large differences between the occupations. Blacksmiths were the most important artisans for the peasants because they repaired and made the necessary agricultural tools. Purchasing clothing from tailors was probably not the most important consideration in peasant households because their calculated clientele was some 60 customers (in 1780 and 1810), which was more than one tailor could serve in a year. Thus the figures in indicate that peasant households did not use the services of tailors every year. The figure was halved by the year 1840, which shows that there was a growing need for their services. The development in the number of shoemakers follows that of tailors: they were not needed until the nineteenth century. Interestingly, artisanal weavers gradually disappeared from the countryside: home weaving and factory-made fabrics eventually deprived male weavers of their livelihood (Vainio-Korhonen, Citation2000).

Table 1. The proportion of artisans in the population and peasant households in Hollola 1780–1840.

To summarise, peasants could increasingly afford to purchase artefacts made by professional artisans as a result of their growing incomes. This meant that it was possible, if they so chose, to use artisans’ services, and it was no longer a matter of the availability of such services (see de Vries, Citation2008, p. 52). The popularity of the artefacts made by professional artisans increased because professionally produced artefacts were better in quality and more durable.

5. From global to local: the import of indigo dye and its use in Finland

In early-nineteenth-century Finland, blue-dyed garments can be regarded as luxury goods, not essential daily consumables. As indigo dye was an expensive imported raw material, it was often only entrusted into the hands of professionals: the dyeing process required both expertise and the right tools in order to get the desired shade and not waste valuable materials. This kind of expertise was usually possessed by professional dyers (with artisanal training), although indigo was not the most demanding dye to use (Pastoureau, Citation2001, p. 74). However, there also existed publications providing instructions on dyeing textiles (Bergholm, 2013, p. 21–24). And indigo dyes were sold in merchant houses and at auctions where anyone could buy them.Footnote10

For early modern Europeans, indigo dye was a rare, expensive, imported commodity originating from distant tropical and subtropical regions, first from East Asia and later from European-owned plantations in the West Indies, Central America and the southern United States (e.g. Balfour-Paul, Citation1999, p. 99; van Schendel, Citation2008, p. 33, 35). Many governments supported the local traditional source of blue dye, the woad plant, which grew commonly in many European countries, including Finland. In some cases, the import of indigo was forbidden (Pastoureau, Citation2001, p. 125). In the eighteenth century (the so-called Age of Utility), the authorities aimed to promote the use of woad, and its cultivation was examined for example at the University of Turku in Finland (Runefelt, Citation2015, pp. 114–115; Alanko, Citation2018, pp. 135–139). Woad, however, proved to be inferior to, and more difficult to use than, the tropical indigo plant, which produced a better and deeper blue colour (Balfour-Paul, Citation1999, pp. 101–104). Nevertheless, woad continued to be used, particularly in situations where indigo was not available (Bergström, Citation2013, pp. 97–98).

As a prized, lightweight commodity, which was easy to re-load, indigo dye was simple to transport via various routes to the Baltic Sea region (Ahonen, Citation2005, p. 24, 109). Indigo dye was regularly transported to Finland from the 1760s onwards, but the quantities were usually insignificant.Footnote11 It is not possible to trace in greater detail the origins of the indigo dyes imported to Finland, but some speculations can be made as we know the European ports of departure of those ships that paid duty in the Sound. Almost half of the ships carrying indigo to a Finnish port departed from Amsterdam. It seems likely that the indigo dye was originally transported to Amsterdam from the Dutch colonies in East Asia (see e.g. Balfour-Paul, Citation1999, p. 100). Almost 40 percent of the ships carrying indigo to Finland had left from an English port: London, Liverpool or Hull. This leads us to believe that the indigo dye was first imported from the British colonies to these British ports. The rest of the ships departed from various other European ports. Almost always the ships carrying indigo were returning to their home ports. It seems that indigo was often carried to Finland in small amounts along with bulk products. However, the quantities imported varied widely. The smallest indigo cargo was less than 20 kilograms, and the largest a few thousand kilograms.Footnote12

below provides further evidence of the importation of indigo dye to Finland via the Sound from 1810 to 1850.Footnote13 Judging from the data, the influence of the Continental Blockade is evident in the 1810s here, as in other regions too, because the indigo dye trade was halted (Pastoureau, Citation2001, pp. 130–131). The earlier mentioned case of the pharmacy student Hellsten demonstrates that, despite the risks of getting caught by customs officials, potential confiscations of cargo and fines, the illicit trade and smuggling of indigo dye and various other colonial goods presented a tempting opportunity because of the high profits to be made. In Hellsten’s case, the trade route went from Stockholm to Turku, but it was not documented where the indigo dye had originally come from or to whom it had been sold. Finland also served as a transit country to the Russian markets (Kaukiainen, Citation1970, pp. 34–35, 57; Kaukiainen, Citation2008; p. 189: Ojala & Paloheimo, Citation2020, pp. 167–170). Eventually, Hellsten managed to save his investment by claiming that he was totally unaware of the restrictions. Many of his compatriots were not so successful in their attempts to ship colonial goods such as tea, coffee, tobacco and dyestuffs to Finland in the early 1810s.Footnote14 Previous research has pointed out that smuggling played an important role in the Baltic Sea region, and it served to satisfy the demand for colonial as well as other products (Aaslestad, Citation2006; Citation2015; Lundqvist, Citation2013).

Table 2. The number of ships importing indigo into Finland and the amount of cargo according to the Sound Toll Registers, 1820–1850.

When trade returned to a normal footing in 1814 after the political turmoil abated, the numbers of vessels carrying indigo dye to Finland increased steadily, although the imports slowed down in the 1830s. From 1831 to 1834, no shipments of indigo were recorded. Nevertheless, there was no significant decrease in the total amount of imported indigo in the 1830s, although shipments were at a standstill in the first years of the decade. Indigo imports rose to a whole new level in the 1840s: more than 100 ships brought in indigo, and the total amount of the dyestuff imported was substantial. It is most likely that the development of the textile and dyeing industry as well as changes in wider consumption patterns had increased the demand for it.

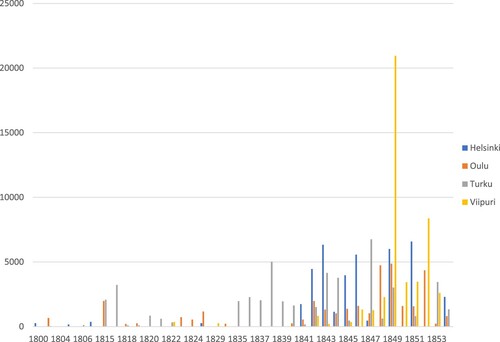

The data indicate that almost all Finnish ports received at least some ships carrying indigo dye. However, the cargoes brought into small-town ports were infrequent and insignificant in size. Four Finnish cities stand out from the rest with regard to the amount of indigo dye imported through them (see ). The ports in southwest Finland, with the city of Turku as its commercial centre, predominated: Turku was the destination of almost one quarter of the imported indigo dye between 1810 and 1850. However, the importation of indigo dye was not recorded every year. Viipuri (Vyborg in Swedish), Helsinki (Helsingfors) and Oulu (Uleåborg) were other cities where more than 20,000 punds of indigo was imported. In addition, in 1849 Viipuri received a notable amount of indigo dye with some 15,000 punds of indigo dye imported to the city. The cargo was exceptionally carried by a foreign vessel as Vyborg’s foreign trade was heavily dependent on foreign vessels (e.g. Ojala & Räihä, Citation2017). The imported indigo dye was sold in the port towns, transported to other regions and distributed to dyers and dye houses.

Figure 2. The import of indigo to major Finnish towns via the Sound, 1800–1856. Source: Sound Toll Registers (www.soundtoll.nlnnnnnnn). NB. The chart shows only the most important ports.

The first half of the nineteenth century was the golden age for the use of indigo dye in Europe. For example, the growing imports of indigo dye and the changes in global trading networks, the accelerating industrial development (especially in the textile industry) as well as the increasing demand for this particular dye in Europe influenced its popularity (van Schendel, Citation2008). Indigo dye kept its popularity in the dyeing industry until the late 1890s – it was only then that synthetic blue dyes were developed (Nieto-Galan, Citation2001, pp. 192–196).

6. Early textile factories in rural Finland

The early broadcloth (kläde in Swedish, verka in Finnish) factories were typically established in rural areas. In Finland, most textile factories used wool as their raw material, and this was also obtained locally. A typical broadcloth factory consisted of several units: a dye house, a weaving mill, a tamping plant and a cutting room, and it employed artisans specialised in the different fields (Annala, Citation1928, p. 226). Therefore, broadcloth manufactories tended to employ dyers – a fact that makes it more difficult to estimate the numbers of dyers operating in rural areas (Schybergson, Citation1974a, p. 82; Bergström, Citation2013, pp. 104–105). However, not all factories made fabrics from start to finish: smaller establishments in particular bought certain services, such as tamping, from others.

Only a few of the early textile factories developed into large-scale producersFootnote16 in the first part of the nineteenth century as they were forced to mechanise and modernise their production in the face of intensified competition in their own sector. For example, the Littoinen broadcloth factory (established in 1823 with a tamping plant several decades older), which was located in the countryside near the city of Turku, and another rural broadcloth factory in Jokioinen (Jockis in Swedish, established in 1797) did develop into large-scale industrial units and were among the largest industrial employers in Finland before the 1850s (Hjerppe, Citation1979).

Finland's only cotton mill, Finlayson & Co, founded in Tampere beside the Tammerkoski Rapids, was an exceptional enterprise among the early nineteenth century broadcloth factories. The mill, established by a Scottish-born engineer called James Finlayson in 1820 and still bearing his name to this today, grew rapidly to become the largest in its field (Haapala & Peltola, Citation2019; Peltola, Citation2019). The products of the above-mentioned broadcloth factories were destined for the army (especially before 1809Footnote17) or local customers, whereas the cotton industry served specifically Russian markets. In fact, exports to Russia and especially to the markets of St Petersburg provided an impetus for investment in the Finnish cotton industry and was a major factor in the further development of this sector (Joustela, Citation1963; von Bonsdorff, Citation1956, pp. 137–143, 227).

Despite the development of large-scale facilities, the majority of the production units in this sector were still small-scale workshops using traditional techniques and employing fewer than five workers (Schybergson, Citation1973, p. 66). They were often operated by self-employed artisans, and as a result some of them were short-lived, an indication of operational uncertainty and the low scale of production. In addition, factories were often rented out, so the operators of some factories changed frequently. This may have influenced the way investments were made (e.g. in production facilities, machinery etc.). Another reason for the low investment rates was the general lack of capital. The skilled workforce, usually journeymen dyers, likewise moved frequently from one factory to another. This was a common practice in several industries in Finland, as the country was small and the number of professionals low (e.g. Leinonen & Talanterä, Citation1987, p. 28).

provides an overview of the social background of the business actors engaged in the textile and dyeing industry, the number of applications concerning the establishment of new facilities and the number of applications on other matters (transferring privileges to a new owner or permits to import raw materials). It must be noted that the sampled data do not allow us detect the later development of the facilities or their success. Although the number of cases is rather low – altogether 38 cases as indicated in Section 2 – the data complement the other source materials consulted for the purposes of this research.

Table 3. Petitions and appeals concerning the rural textile and dyeing industry and the social background of the petitioners.

The majority of the cases concerned the establishment of a new broadcloth manufactory and/or dye house. In practice, many of the petitioners for new textile manufactory privileges were artisans specialising in dyeing, for in this way they could set up business in the countryside. Occasionally, the founders were journeymen attempting to circumvent the existing legislation and secure access to the countryside in order to be near their potential customers because they could not apply to be parish artisans. Another reason for trying to establish a new business in the countryside was that it was difficult for newcomers to establish themselves as urban artisans because guild constraints tended to limit competition. Thus, for a journeyman wishing to become an independent actor, it was easier to establish a new business or rent a facility in the countryside. In other words, manufacturing privileges were used as a front for an ordinary craft workshop in cases where the trade was not otherwise legal in the countryside. However, the authorities noticed these attempts to circumvent the legislation, and the licenses of more modest factories were revoked in 1844 (Schybergson, Citation1974a, pp. 70–74; 1992, p. 87; Nyberg, Citation2000, p. 622).

The applications for privileges to establish new facilities indicate increased activity in this sector, although it is evident that some of the privileges that were granted were not used. Similarly, a number of the established facilities were not successful, and their business declined (e.g. von Bonsdorff, Citation1956, p. 223). In any case, our data document the growing interest in establishing new facilities – and most likely the growing demand for their products – in rural areas. A minority of the selected cases concern the expansion of existing facilities or the transfer of rights to other persons. Petitions to import raw materials or machinery with lower customs duties or petitions for government loans were submitted only by the owners of the large-scale facilities such as the proprietors of the Littoinen broadcloth factory. The number of cases rose steadily throughout the first part of the century, following the above-mentioned growth and diversification of the industry.Footnote18

Applicants for a permit to establish textile manufactories can be roughly divided into two groups: artisans (in particular journeymen dyers) and members of the gentry. One example of a member of the local gentry seeking to become a manufacturer comes from Hollola. In fact, a family belonging to the landowning gentry, the Polóns of the village of Messilä, submitted several applications before the 1840s. In 1815 Carl Henrik Polón applied for permission to set up a broadcloth factory. The licence was granted, but owing to the early death of the owner, a request was made to transfer the factory privileges to other relatives in 1821 and again in 1824.Footnote19 Polón had started his business by employing journeymen dyers, but after his death, the factory, and in particular its dyeing facilities, were rented out to journeymen dyers. The renting-out of facilities was not an uncommon practice in the countryside at the time as other rental advertisements can be found in the newspapers.Footnote20 C. H. Polón’s cousin, Hans Henrik Polón, was also granted permission to establish another textile factory in the same village in 1823. However, instead of having two active broadcloth factories operating in the village, as the official permits allowed, there is evidence that only one factory was in operation, and its production was very small. Indeed, in 1825, for example, neither of the factories had so far produced any cloth owing to a lack of raw materials and tools.Footnote21 In the late 1820s, the operations of launched business improved as there was an active dye house (run by changing dyers), but only one broadcloth weaver without any assistants.

Although, as has been claimed, privileges to establish new facilities were granted fairly liberally in early-nineteenth-century Finland (Schybergson, Citation1973, p. 47; Hjerppe, Citation1979, pp. 126–127), not all applications were successful. For instance, an attempt to establish a new dye house in Hollola in 1826 by a dyer named Ojalin and an industrialist called Hofdahl, who already possessed two dye houses in the town of Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus in Swedish), was eventually unsuccessful. Permission for a dye house was granted by the local administration, but the Economic Department of Finnish Senate refused it twice. The Department did not provide any reason for its decisions, and the dye house was not established.Footnote22

7. A fondness for blue: colours in peasant men’s wardrobes

Evaluating the consumption of the rural population is frequently conducted using probate inventories (e.g. Laurikkala, Citation1947; Ulväng, Citation2012; Hutchinson, Citation2014; Johnson, Citation2014; Uotila, Citation2019). Although some worn-out clothes were probably not documented, the most valuable garments were meticulously recorded in probate inventories. Typically these documents also recorded details of the garment such as its colour and fabric. The lists of clothing in probate inventories began with the most valuable garments, often overcoats. In Hollola, the regular travel coat of peasant men was the kaprokki (in Finnish) (kapprock in Swedish), which was an extravagant long coat with a cape covering the shoulders and upper torso. The origin of the coat was in England, and in the latter part of the nineteenth century, it became associated with its use among coachmen, who wore a version called an ulster coat. Another type of popular overcoat was the surtout (sortuukki in Finnish). The Finnish version of the surtout was a sort of frock coat, long and tight-fitting. The model for this long coat came from France. These coats were garments the possession of which was regarded as indicative of a prosperous peasant, and items which not everyone could afford (Kaukonen, Citation1985, p. 239; Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, pp. 192–193). Typically, they were made of factory-made broadcloth or alternatively of frieze, a homemade coarse woollen fabric (sarka in Finnish, vadmal in Swedish).

The kaprokki in particular was generally regarded as a garment for a wealthy peasant; it was made to measure and frequently made of manufactured fabric, both of which were features that increased its value and appreciation. The coat was eminently suitable to proclaim the position and affluence of a peasant when he was attending church or going to town (Kaukonen, Citation1985, p. 239; Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, p. 17, 200). In the 1830s, it was not exactly a novelty as the first mentions of it are from the end of the eighteenth century, but it gained in popularity in the nineteenth century. The surtout was a rarity in a man’s wardrobe at the end of the eighteenth century, but it gained in popularity in Hollola in the 1820s (Kuusi, Citation1937, p. 328). The area of distribution was mainly western Finland (Lehtinen & Sihvo, Citation2005, pp. 192–193). A new kaprokki coat made of blue broadcloth might easily cost as much as a cow; clearly not everybody could afford to purchase one.

Since these coats were long, more of the valuable fabric was needed, which required good cutting skills on the part of the tailor (Ulväng, Citation2012, p. 211; Uotila, Citation2019, pp. 121–122). A kaprokki with impressive details required a lot of extra fabric, thus making it more luxurious and fashionable. These long coats were investments that demonstrated the wearer’s wealth and status as a peasant. Coats, like clothing in general, were also inherited, sold and pawned (Riello, Citation2020, pp. 91–93). Well-made clothes thus had an economic significance: they were an asset, which could be sold if necessary. A fashionable outfit was also important for the user, and it served the wearer’s own comfort and pleasure. These garments did not necessarily merely imitate upper-class dress, but, as de Vries has noted, they also sent a signal to the wearers’ peers (de Vries, Citation2008, pp. 22–24, 52; Riello, Citation2020, p. 20).

The long coats were frequently blue as demonstrated in . Interestingly, over 60 per cent of the men’s long coats in the probate inventories investigated here were made of blue-dyed fabric. Another popular colour was grey, but this may have referred to uncoloured or home-dyed clothing. The probate inventories do not reveal who had dyed them or with what, but the fact that most of the clothes were blue, i.e. dyed, indicates the popularity of dyeing. It is most likely that when the garment is described as dark or deep blue, it was dyed with indigo dye. The fondness for the colour blue is partly explained by the fact that it was widely associated with military uniforms (e.g. Sweden) as well with the uniforms of certain Finnish officials after 1809, which gave the colour further prestige (Wirilander, Citation1974, p. 49; Alm, Citation2016, pp. 50–51; van Schendel, Citation2008, p. 33).

Table 4. The proportion of the kaprokki and surtout coats in men's probate inventories, Hollola 1830s.

The inhabitants of Hollola Parish could have had their fabrics and yarns dyed in several places. Before the establishment of the local broadcloth factory (in the 1820s), the residents of Hollola used the services of urban dye houses, meaning that they either travelled more than 60 kilometres to the nearest town, Hämeenlinna, or asked others to go on their behalf. In addition, the dyers themselves toured the countryside collecting work orders. It is likely that the materials were home-woven or homespun. Occasionally the fabrics disappeared, or some other mix-up occurred, so disagreements were brought to the local courts. Interestingly, in the court records the disputes between the dyers and their customers frequently concerned fabrics dyed blue. For example, in 1815, one peasant complained in court that together with two other men he had left material with a dyer called Sundberg of the town of Hämeenlinna, but now his fabric had gone missing. The court case clearly stated that he had ordered a dark blue colour.Footnote23 According to the governor of the Province of Häme, Sundberg and his fellow dyers in Hämeenlinna were reputed to serve rural inhabitants as well as townsfolk quite profitably in the 1830s, a statement that testifies to the wide demand for the services of urban dye houses (Lindeqvist, Citation1930, p. 125).

The court records also provide further details on the businesses of individual dyers and their relations with their customers, which they usually describe as disputatious. For instance, the dyers of Hollola's own dye house, which operated under the privilege of the broadcloth manufactory in the above-mentioned village of Messilä, also lost their customers’ fabrics. Here, in particular, two dyers lost their customers’ goods, and they had to compensate them for the lost fabrics. One of them, a dyer called Nysted, lost the fabrics in a fire at the dye house in 1835, but he was still required to pay compensation. After the fire, the dyer sued his landlord over a rent disagreement, in which he listed the dyeing commissioned by the landlord and also calculated the cost of his improvements to the dye house. During the five years that the dyer had rented the dye house, the work orders alone amounted to 25 Swedish riksdaler, a sum equivalent to a good horse. Most of the fabrics (18 out of 23) were required to be dyed blue.Footnote24

At the same time, the production of broadcloth was minimal in Messilä because there was only one weaver in the village capable of producing this kind of cloth. However, broadcloth was a very common fabric in men’s outer garments, so it is possible that the broadcloth produced in Messilä – although minimal – was sold locally. In any case, the above-mentioned large-scale broadcloth factories had created extensive selling networks, as evidenced in contemporary newspaper advertisements. This broadcloth, being factory-made, was a more highly appreciated material than frieze – and it was then passed on to the parish tailors.

The survival and ability of artisans like dyers and tailors to earn a living as rural artisans is in itself a sign of the growing demand for their services. Additionally, as the quality of yarns and fabrics improved, it was worth paying to have these dyed and have the finished fabric cut and sewn by a professional.

8. Discussion

Our aim has been to demonstrate that during the early nineteenth century individual tastes and choices changed and various kinds of consumer goods became available to a wider group of the population. It is also evident that consumption was not anymore aimed at satisfying only basic daily needs but was an investment in a person’s own status – especially in the case of sartorial choices – as well as an investment that served the owner’s pleasure and comfort. Obviously, there was more room for individual choice, which was demonstrated in the male peasants’ wardrobes: they purchased and wore fashionable, blue-dyed garments, a practice that conveyed personal and collective meanings. According to our research so far, we argue that the use of blue clothes was a sign of opulence in Finland: as the wealth of certain groups, particularly the landholding farmers, increased, they were able to purchase clothes dyed with imported dyes like indigo.

Again, it was not only the demand for luxury items or novel products – or for fabrics dyed blue – that grew. At the same time, the production of everyday consumer goods also shifted from households to local professional manufacturers and artisans. Following the arguments developed by de Vries, the households became more market-oriented and, hence, more ‘industrious’. The growing demand became evident in the changes in the wardrobes of the peasant population: our closer analysis of the probate inventories shows that factory-made and factory-dyed fabrics became more common. Evidently, the material culture was evolving: this was also seen in the wardrobes of rural men.

The change that took place in consumption and the growth of market-based consumption can be seen in the increase in the number of different production facilities in nineteenth-century rural Finland. Although the economic environment was strictly regulated, it was possible to find opportunities to engage in various industries within it. This took place particularly in rural locations, and as a result production facilities of various sizes were established in the countryside. The growth of the dyeing industry is also demonstrated by the fact that the import of indigo dye increased substantially from the 1840s onwards. The diversification and modernisation of economic activity were also reflected in the changes and growing demand in local markets – as became evident in the case of the parish of Hollola studied in the present article.

The increasing supply of, and demand for, everyday consumer goods and most likely also higher expectations regarding the quality of the products in both urban and rural areas illustrate the changes in consumption. Furthermore, our research on the import of indigo dye indicates that the availability of this valuable foreign commodity not only reshaped consumer culture but also influenced sartorial craftsmanship and the production of textiles – it affected the traditional dyeing industry based on the use of woad as it required a new kind of expertise. Nevertheless, following the arguments of the industrious revolution theory, we maintain that consumption rather than major technological changes led to demand of blue garments. Moreover, the trade of indigo dye connected Finland to the global trading networks as well as the colonial trade and goods. That being said, there is a certainly need for a more detailed study of this development in a modernising Finland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 National Archives of Finland (NA, Helsinki), Archives of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, Register of Petitions and Appeals 1810 (Ab:2); Case file STO AD 311/61 1810; Minutes of the joint session of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate II 1810 (Ca:3).

2 The word 'peasant' is used here in the sense of a land-owning farmer who belonged to the Peasant Estate. It carries no pejorative connotation.

3 For a criticism of this approach, see Ogilvie, Citation2010.

4 NA, Hollola church archives, probate inventories 1831–1839.

5 The newspapers were published mainly in Swedish.

Katja Palokangas, a history student at the University of Jyväskylä, has kindly assisted in this vast task.

6 It is difficult to study retailing in rural Finland in the first part of the nineteenth century: the local markets operated mainly unofficially due to the restrictive policies. On the Swedish situation, see e.g. Nyberg, Citation2010 and Wottle, Citation2010.

7 E.g. Wasa Tidning, 11.02.1843; Borgå Tidning, 21.09.1844, Helsingfors Tidningar, 28.06.1845; Åbo Tidningar, 22.01.1845; Åbo Underrättelser, 25.01.1845. On similar advertisements published in the Swedish newspapers, see Nyberg et al., Citation1998 and Nyberg, Citation2010, pp. 110–115.

8 E.g. Oulun Wiikko-Sanomia, 07.03.1829.

9 For the sake of clarity, the government did not contribute to the large-scale textile production in the period under closer scrutiny neither forced labour was used in production. However, women who had committed various kinds of crimes (including vagrancy) were sentenced to work in facilities called spinnhus (practically a women’s prison). The women were employed e.g. in spinning.

10 Åbo Allmänna Tidning 26.04.1814; Finlands Allmänna Tidning 13.03.1821.

11 Sound Toll Registers (www.soundtoll.nl).

12 Sound Toll Registers (www.soundtoll.nl).

13 The data was kindly provided by Timo Tiainen, a PhD student at University of Jyväskylä.

14 E.g. NA, The Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, The Registers of Petitions and Appeals, 1809–1815; Case file STO AD 311/61 1810.

15 One pund is estimated to be 0.496 kg (Karvonen, Citation2020, p. 108).

16 In this article, a large-scale production facility means a unit which employed over 30 persons.

17 The Finnish army was dismantled after 1809 when Finland became a part of the Russian Empire.

18 NA, The Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, The Registers of Petitions and Appeals, 1810–1850.

19 NA, The Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, The Registers of Petitions and Appeals, 1809–1850; Minutes of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, 1815–1850.

20 Finlands Allmänna Tidning 03.04.1828.

21 NA, Hollola District Court, winter session1826 Ca3:93 §51; autumn session 1826 Ca3:94 § 326.

22 NA, Hollola District Court, winter session1826 Ca3:93 §51; autumn session 1826 Ca3:94 § 326; NA, Minutes of the Joint Session of the Economic Department of the Senate, I 1826–1826 (Ca:51), 31.5.1826; II 1826–1826 (Ca:52), 8.11.1826.

23 NA; Hollola district court, winter session 1815 Ca3:71 §199. See also autumn session 1816 Ca3:74 §152.

24 NA; Hollola district court, autumn sessions 1836 Ca3:113 §289.

References

- National Archives of Finland (NA, Helsinki)

- Archives of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate:

- Registers of Petitions and Appeals 1809–1815, 1820, 1825, 1830, 1835, 1845, 1850

- Minutes of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate

- Registers of the Minutes of the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, 1809–1815

- Petitions and appeals submitted to the Economic Department of the Finnish Senate, selected case files

- Hollola District Court Archive:

- Legal protocols 1815–1836 (Ca3: 71–113)

- Hollola Church Archive:

- Probate inventories 1831–1839 (I Jee:1)

- Selected newspapers retrieved from National Library of Finland, digital collections https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/etusivu?set_language=en

- Aaslestad, K. B. (2006). Paying for War: Experiences of napoleonic rule in the hanseatic cities. Central European History, 39(2006), 641–675.

- Aaslestad, K. B. (2015). Introduction. Revisiting Napoleon’s continental system: Consequences of economic warfare. In J. Joor & K. B. Aaslestad (Eds.), Revisiting Napoleon's continental system: Local, regional and European experiences (pp. 1–22). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ahlqvist, K. (2008). Kulutuksen pitkä kaari. Niukkuudesta yksilöllisiin valintoihin. Helsinki: Palmenia Helsinki University Press.

- Ahonen, K. (2005). From sugar triangle to cotton triangle. Trade and shipping between America and Baltic Russia, 1783–1860. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Alanen, A. J. (1957). Suomen maakaupan historia. Helsinki: Kauppiaitten kustannus.

- Alanko, T. (2018). Malva ja mulperi. Poimintoja entisajan puutarhoista. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Alm, M. (2016). Making a difference. Sartorial practices and social order in eighteenth-century Sweden. Costume, 50(1), 42–62.

- Annala, V. (1928). Suomen varhaiskapitalistinen teollisuus Ruotsin vallan aikana. Kansantaloudellinen yhdistys: Helsinki.

- Balfour-Paul, J. (1999). Indigo in South and South-East Asia. Textile History, 30(1), 98–112.

- Berg, M. (1994). The age of manufactures, 1700–1820. Industry, innovation and work in Britain (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bergström, E. (2013). Den blå handen. Om Stockholms färgare 1650–1900. Stockholm: Nordiska Museets Förlag.

- Breward, C. (1999). Renouncing consumption: Men, fashion and luxury, 1870-1914. In D. L. Haye, & E. Wilson (Eds.), Defining dress: Dress as object, meaning and identity (pp. 48–62). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Bruland, K. (1989). British technology and European industrialization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- de Moor, T., & van Zanden, J. L. (2010). Girl power: The European marriage pattern and labour markets in the North Sea region in the late medieval and early modern period. Economic History Review, 63(1), 1–33.

- Dennison, T., & Ogilvie, S. (2014). Does the European marriage pattern explain economic growth? Journal of Economic History, 74(3), 651–693.

- de Pleijt, A. M., & van Zanden, J. L. (2016). Accounting for the “little divergence”: what drove economic growth in pre-industrial Europe, 1300–1800? European Review of Economic History, 20(4), 387–409.

- de Vries, J. (2008). The industrious revolution. Consumer behavior and the household economy, 1650 to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gøbel, E. (2010). The sound toll registers online project, 1497–1857. International Journal of Maritime History, 22(2), 305–324.

- Haapala, P., & Peltola, J. (2019). Globaali Tampere: Kaupungin taloushistoria 1700-luvulta 2000-luvulle. Tampere: Tampereen museot.

- Heckscher, E. (1953). Merkantilismen. Förra delen. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag.

- Heikkinen, S. (1981). Kulutus Suomessa autonomian ajan jälkipuoliskolla. In Y. Kaukiainen (Ed.), När samhället förändras. Kun yhteiskunta muuttuu (pp. 395–421). Helsinki: Suomen historiallinen seura.

- Heikkinen, S. (1986). On private consumption and the standard of living in Finland, 1860–1912. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 34(2), 122–134.

- Heikkinen, S. (1997). Finnish food consumption from the 1860s to the 1950s. In J. Söderberg, & L. Magnusson (Eds.), Kultur och konsumtion i Norden 1750–1950 (pp. 83–110). Helsingfors: Finska historiska samfundet.

- Heinonen, V., & Peltonen, M. (2013). Finnish consumption. An emerging consumer society between East and West. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Hemminki, T. (2014). Vauraus, luotto, luottamus: Talonpoikien lainasuhteet Pohjanlahden molemmin puolin 1796–1830. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Hjerppe, R. (1979). Suurimmat yritykset Suomen teollisuudessa 1844–1975. Tammisaari: Societas scientiarum Fennica.

- Hjerppe, R. & Jalava, J. (2006). Economic growth and structural change – A century and a half of catching-up. In J. Ojala, J. Eloranta & J. Jalava (Eds.), The road to prosperity. An economic history of Finland, pp. 33–64. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Hutchinson, A. (2014). Consumption and endeavour. Motives for the acquisition of new consumer goods in a region in the north of Norway in the 18th century. Scandinavian Journal of History, 39(1), 27–48.

- Ijäs, U. (2015). Talo, kartano, puutarha: Kauppahuoneen omistaja Marie Hackman ja hänen kulutusvalintansa varhaismodernissa Viipurissa. Turku: University of Turku.

- Ijäs, U. (2017). English luxuries in nineteenth-century Vyborg. In J. Ilmakunnas, & J. Stobart (Eds.), A Taste for luxury in early modern Europe. Display, acquisition and boundaries (pp. 265–282). Oxford: Bloomsbury.

- Ilmakunnas, J. (2009). Kuluttaminen ja ylhäisaatelin elämäntapa 1700-luvun Ruotsissa. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Ilmakunnas, J. (2012). Kartanot, kapiot, rykmentit. Erään aatelissuvun elämäntapa 1700-luvun Ruotsissa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Ilmakunnas, J. (2017). French fashion: Aspects of elite lifestyle in eighteenth-century Sweden. In J. Ilmakunnas, & J. Stobart (Eds.), A taste for luxury in early modern Europe. Display, acquisition and boundaries (pp. 243–263). Oxford: Bloomsbury.

- Jahnsson, Y. (1904). Ylellisyysasetukset Ruotsissa vapauden ajalla. Historiallinen Aikakauskirja, 2(6), 171–188.

- Johnson, S. (2014). Fashion from the ship. Life, fashion and fashion dissemination in and around Kokkola, Finland in the 18th century. In T. Engelhardt Mathiassen (Ed.), Fashionable encounters. Perspectives and trends in textile and dress in the early modern Nordic world (pp. 31–48). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Joustela, K. E. (1963). Suomen venäjän-kauppa autonomian ajan alkupuoliskolla vv. 1809–1865. Helsinki: SHS.

- Karvonen, L. (2020). From salt to naval store: Swedish trade with southern Europe 1700–1815 [Master’s Thesis in Economic History]. Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä.

- Kaukiainen, Y. (1970). Suomen talonpoikaispurjehdus 1800-luvun alkupuoliskolla (1810–1853). Helsinki: Suomen historiallinen seura.

- Kaukiainen, Y. (2008). Ulos maailmaan! Suomalaisen merenkulun historia. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Kaukonen, T.-I. (1985). Suomalaiset kansanpuvut ja kansallispuvut. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Koskelainen, Y. (1923). Littoisten verkatehtaan historia ynnä piirteitä Wechterin manufaktuurilaitoksen vaiheista, 1738–1823–1923. Porvoo: Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö.

- Kuusanmäki, L. (1936). Kulutustavarain leviäminen maalaisväestön keskuuteen. In G. Suolahti (Ed.), Suomen kulttuurihistoria IV. Industrialismin ja kansallisen nousun aika (pp. 96–119). Jyväskylä: Gummerus.

- Kuusi, S. (1937). Hollolan pitäjän historia. Muinaisuuden hämärästä kunnallisen elämän alkuun 1860-luvulle. II osa. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Kuusterä, A. (1989). Valtion sijoitustoiminta pääomamarkkinoiden murroksessa 1859–1913. Helsinki: Suomen historiallinen seura.

- Laurikkala, Saini (1947). Varsinais-Suomen talonpoikain asumukset ja kotitalousvälineet 1700-luvulla: Kulttuurihistoriallinen tutkimus. Turku: Turun yliopisto.

- Lehtinen, I., & Sihvo, P. (2005). Rahwaan puku. Folk costume. Näkökulmia Suomen kansallismuseon kansanpukukokoelmiin. Museovirasto: Helsinki.

- Leinonen, K., & Talanterä, E. (1987). Wechteristä Valvillaan: Suomen tekstiiliteollisuus 250 vuotta. Turku: Valvilla.

- Lindeqvist, K. O. (1930). Hämeenlinnan kaupungin historia, 3. Hämeenlinnan kaupungin historia vuosina 1809–1875. Hämeenlinna: Hämeenlinnan kaupunki.

- Lundqvist, P. (2013). Förbjudna tyger. In K. Nyberg & P. Lundqvist (Eds.), Dolda innovationer. Textila produkter och ny teknik under 1800-talet (pp. 191–213). Stockholm: Kulturhistoriska Bokförlaget.

- Mokyr, J. (1990). The lever of riches. Technological creativity and economic progress. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Murhem, S., & Ulväng, G. (2017). To buy a plate: Retail and shopping for porcelain and faience in Stockholm during the eighteenth century. In J. Ilmakunnas, & J. Stobart (Eds.), A taste for luxury in early modern Europe. Display, acquisition and boundaries (pp. 197–215). Oxford: Bloomsbury.

- Nevalainen, P. (2016). Kulkukauppiaista kauppaneuvoksiin. Itäkarjalaisten liiketoimintaa Suomessa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Nieto-Galan, A. (2001). Colouring textiles. A history of natural dyestuffs in industrial Europe. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Nyberg, K. (2000). Brittisk teknik, svensk överföring och finländsk mottagande? Textilindustrin i Sverige och Finland 1809–1870. Exemplet ylleindustrin. Historisk Tidskrift, 120(4), 615–641.

- Nyberg, K. (2010). Staten, manufakturerna och hemmamarknadens framväxt. In K. Nyberg (Ed.), Till salu: Stockholms textila handel och manufaktur 1722–1846 (pp. 95–117). Stockholm: Stads- och kommunhistoriska institutet.

- Nyberg, K., Jonsson, P., Fagerberg, M., & Lindberg, E. (1998). Trade and marketing. Some problems concerning the growth of market institutions in Swedish industrialisation. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 46(1), 85–102.

- Ogilvie, S. (2010). Consumption, social capital, and the ‘industrious revolution’ in early modern Germany. The Journal of Economic History, 70(2), 287–325.

- Ojala, J., & Paloheimo, M. (2020). Näköpiirissä laskevia voittoja: Ulkomaankauppiaat etujaan puolustamassa Suomen sodan jälkeen. In P. Einonen, & M. Voutilainen (Eds.), Suomen sodan jälkeen: 1800-luvun alun yhteiskuntahistoria (pp. 153–179). Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Ojala, J., & Räihä, A. (2017). Navigation Acts and the integration of North Baltic shipping in the early nineteenth century. International Journal of Maritime History, 29(1), 26–43.

- Paloheimo, M. (2012). Business life in pursuit of economic and political advantages in early-nineteenth-century Finland. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Paloheimo, M., & Uotila, M. (2015). Elinkeinoluvat ja talouselämän monipuolistuminen 1800-luvun alun Suomessa. Ennen ja nyt – Historian Tietosanomat, 3/2015.

- Pastoureau, M. (2001). Blue. The history of a color. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Peltola, J. (2019). The British contribution to the birth of the Finnish cotton industry (1820–1870). Continuity and Change, 34(1), 63–89.

- Ranta, R. (1978). Pohjanmaan maaseudun käsityöläiset vuosina 1721–1809 I. Käsityöläiseksi pääsy ja käsityöläisten lukumäärä. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Riello, G. (2020). Back in fashion. Western fashion from the middle ages to the present. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Roche, D. (1994). The culture of clothing. Dress and fashion in the ‘ancien Regime’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Runefelt, L. (2015). Grå bonde, blå bonde. In P. von Wachenfeldt, & K. Nyberg (Eds.), Den Svenska begäret. Sekler av lyxkonsumtion (pp. 106–129). Stockholm: Carlssons Bokförlag.

- Scheltjens, W., & Veluwenkamp, W. (2012). Sound toll registers online: Introduction and first research examples. International Journal of Maritime History, 24(1), 301–330.

- Schybergson, P. (1973). Hantverk och fabriker I. Finlands konsumtionsvaruindustri 1815–1870. Helhetsutveckling. Helsingfors: Finska vetenskaps-societeten.

- Schybergson, P. (1974a). Hantverk och fabriker II. Finlands konsumtionsvaruindustri 1815–1870. Branschutveckling. Helsingfors: Finska vetenskaps-societeten.

- Schybergson, P. (1974b). Hantverk och fabriker III. Finlands konsumtionsvaruindustri 1815–1870. Tabellbilagor. Helsingfors: Finska vetenskaps-societeten.

- Schybergson, P. (1980). Teollisuus ja käsityö. In E. Jutikkala, Y. Kaukiainen and S.-E. Åström (Eds.), Suomen taloushistoria 1. Agraarinen Suomi, pp. 408–435. Helsinki: Tammi.

- Schybergson, P. (1992). Ensimmäiset teollisuuskapitalistit. In P. Haapala (Ed.), Talous, valta ja valtio. Tutkimuksia 1800-luvun Suomesta (pp. 89–107). Tampere: Osuuskunta Vastapaino.

- Söderlund, E. (1949). Hantverkarna. Andra Delen. Stormaktstiden, frihetstiden och gustavianska tiden. Stockholm: Tidens Förlag.

- Talve, I. (1979). Suomen kansankulttuuri. Historiallisia päälinjoja. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Ulväng, M. (2012). Klädekonomi och klädkultur. Böndernas kläder i Härjedalen under 1800-talet. Möklinta: Gidlunds förlag.

- Uotila, M. (2014). Käsityöläinen kyläyhteisönsä jäsenenä. Prosopografinen analyysi Hollolan käsityöläisistä 1810–1840. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Uotila, M. (2019). Kun talonpojat ryhtyivät kuluttamaan. Pukeutuminen miehen aseman ja varallisuuden ilmentäjänä 1800-luvun alun suomalaisessa maaseutuyhteisössä. In A. Turunen, & A. Niiranen (Eds.), Säädyllistä ja säädytöntä. Pukeutumisen historiaa renessanssista 2000-luvulle (pp. 115–144). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Vainio-Korhonen, K. (2000). Handicrafts as professions and sources of income in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Turku (Åbo). A gender viewpoint to economic history. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 48(1), 40–63.

- van Schendel, W. (2008). The asianization of indigo. Rapid change in global trade around 1800. In P. Boomgaard, D. Kooiman, & H. S. Nordholt (Eds.), Linking destinies. Trade, towns and kin in Asian history. Leiden: Brill.

- Vilkuna, K. (1953). Isien työ. Veden ja maan viljaa. Arkityön kauneutta. Helsinki: Otava.

- von Bonsdorff, L. G. (1956). Linne och jern, 1. Textil- och metallindustrierna i Finland intill 1880-talet. Helsingfors: Söderströms.

- Voutilainen, M., Helske, J., & Högmander, H. (2020). A Bayesian reconstruction of a historical population in Finland, 1647–1850. Demography, 57(3), 1–22.

- Wassholm, J., & Östman, A. (eds.). (2021). Att mötas kring varor: Plats och praktiker i handelsmöten i Finland 1850–1950. Helsingfors: Svensk litteratursällskapet i Finland.

- Wassholm, J., & Sundelin, A. (2018). Emotions, trading practices and communication in transnational itinerant trade: Encounters between ‘Rucksack Russians’ and their customers in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Finland. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 66(2), 132–152.

- Wirilander, K. (1974). Herrasväkeä. Suomen säätyläistö 1721–1870. Helsinki: Suomen historiallinen seura.

- Wottle, M. (2008). Opposing prêt-à-porter: mills, guilds and government on ready-made clothing in early nineteenth-century Stockholm. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 56(1), 21–40.

- Wottle, M. (2010). Detaljhandel med kläder och tyger, 1734–1834. In K. Nyberg (Ed.), Till salu: Stockholms textila handel och manufaktur 1722–1846 (pp. 119–141). Stockholm: Stads- och kommunhistoriska institutet.