Gender has long been an important category of historical analysis, nurtured by different and sometimes competing paradigms of research. In the 1970s, the study of gender was closely linked to the expansion of women’s history. Inspired by feminist and Marxist theories, this approach greatly contributed to the development of new insights on economic life, work, and remuneration in relation to women’s own experiences. Post-structural theories became more important after Joan W. Scott’s seminal article ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Research’ (Citation1986). This approach considered gender as the way in which humans create knowledge about the world they inhibit, rather than something they are. The importance of research on economic history from a gender perspective has increased significantly since the late 1980s – and perhaps especially so in the Nordic countries? At least, this is a timely question to ask 30 more years after Scott wrote her article and partly transformed the practices of gender research in history.

The inspiration for this special issue came from a seminar held at Stockholm University, Sweden, in the beginning of 2019, when a group of researchers in various stages of their career gathered to discuss the status of gender and intersectionality within economic history. Some of us were critical of how economic history was sometimes defined in a way that excluded the type of gender research we were engaged in. The idea of suggesting a special issue in SEHR was raised to highlight gender as an essential analytical category for economic history (and thus challenge narrower definitions), and to better understand the status of gender in the broader Nordic setting and beyond. Fortunately, the editors-in-chief of the journal were positive about the idea.

An open call for a special issue on gender and economic history broadly defined, was announced in the spring of 2020. We received nine papers for peer review, five of them are included in the issue, spanning topics such women and entrepreneurship in Iceland, migrant mothers and workers in Sweden, the decision-making roles of women in Finnish household economy, and Danish public wage hierarchies. What this selection of articles, their topics, and theoretical orientation can tell us about the current status of gender scholarship in general or in Nordic economic history in particular, is however uncertain. Trying to answer this question also extends the scope of the special issue. What is still evident, is the absence of Norwegian author(s). This indicates that the efforts and traditions of including gender as a category of economic historical analysis do vary across the Nordic region as much as overtime. What was in fashion in the 1980s, are not anymore, or the opposite. The impulses of gender research within the field of economic history, changes as much as the institutional conditions for economic history research do.

The introduction to this special issue is organised as follows. As a point of departure, we discuss the importance of gender perspectives in economic history by tracing it in articles published in economic history journals. Thereafter, we offer a short historiography of Nordic gender economic history before the articles of the special issue are presented and discussed.

From women’s history to gender perspective

This special issue on gender is not the first, and probably far from the last, within history-and economic history journals. In 1998, Business History Review offered a special issue titled ‘Gender and Business’, Scandinavian Journal of History presented in 2016 one on ‘Gender, Material Culture and Emotions in Scandinavian History’, and in 2021 Swedish Historisk tidskrift published a special issue titled ‘tema: kvinnor’ [theme: women]. Two more are also in the planning; one in Business History called ‘Gender, Feminism, and Business History: From periphery to centre’, and another in Labor History called ‘Gender, War and Coerced Labour’. However, as far as we know, no special issue on gender has appeared in the more general international economic history journals such as Journal of Economic History, Economic History Review, or Explorations in Economic History. Of course, this does not imply that gender perspectives have been absent in these journals. A brief comparison shows that women and gender since the 1980s have been the topic in several of these mainstream journal articles.

The mentioning of women, or female in the title of journal articles, does not necessarily mean that the research published employs a gender perspective. However, the use of these concepts in the titles is an indication of its centrality. thus shows that topics and issues deriving from women’s and gender history have been part of economic history since the early 1980s. Yet, as Albert J. Mills and Kristin S. Williams (Citation2021, p. 1) have argued for the case of business history, journals are important gatekeepers for ‘the ongoing process of defining’ the discipline. From their overview, women and gender studies are seldomly presented in business history journals but are more often published as independent monographs or articles in other field-specific journals.

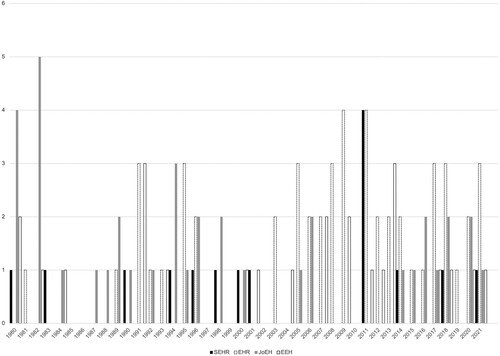

Figure 1. The number of articles in economic history journals using the concepts ‘gender’, ‘women’, or ‘female/feminine’ in their titles, 1980–2021. Sources: Journal homepages for Scandinavian Economic History Review (SEHR), Economic History Review (EHR), Journal of Economic History (JoEH), and Explorations in Economic History (EEH), accessed 8 April 2022.

Women’s and the later gender history have been closely related to the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, and later waves of feminisms and identity politics. This has been decisive for what women’s and gender historians have been interested in, their research topics, methodologies, and how they have problematised gender relations. Mainstream historiographies also tend to emphasis the role of new social history, also known as history from below, for the making womeńs history as an academic discipline. During the 1980s, new theoretical impulses moved the field in new directions and towards what is now known as gender history. This included post-structuralist theory, Foucauldian discourse analysis and other cultural theories, turning the historiańs attention to how people and societies in the past gave meaning to sexual differences.

Since the 1980s, gender history has been a scholarly field with its journals and conferences. Black feminism and the rise of a queer social movement have inspired a theoretical expansion, covering the intersection of power relations beyond gender and class. A simplified historiographical narrative thus suggests that the field went from a focus on women’s history – and womeńs contribution to history – to gender as an independent category of historical analysis, and then to a theoretical broadening including masculinity studies, post-colonialism, queer studies and the concept of intersectionality. From our limited survey of article titles, the trend towards increasing use of gender as a more theoretically advanced and socially inclusive concept can only partially be discerned (see ).

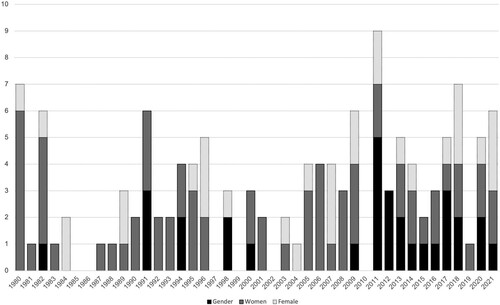

Figure 2. Uses of the concepts ‘gender’, ‘women’, and ‘female/feminine’ in article titles in economic historical journals, 1980–2021. Sources: Journal homepages for Scandinavian Economic History Review (SEHR), Economic History Review (EHR), Journal of Economic History (JoEH), and Explorations in Economic History (EEH), accessed 8 April 2022.

When the concept of gender gained popularity among researchers in the 1990s, it was still only central enough to end up in the titles of all together seven articles in the studied journals. However, in the 2010s the concept had more of a breakthrough in economic history journals, although after almost a decade of absence. Also, the concept of gender does not seem to have replaced the use of ‘women’ and ‘female’. Taken together, still, gender and women’s history appeared as central topics of several economic history journal articles during the period 1980–2021. Nevertheless, when we also searched for queer, post-colonialism, masculinity, and intersectionality, we found that these concepts were almost totally absent not only in titles but also in full texts of published articles in those same journals.Footnote1 This is not only an indication of the absence of categories and concepts used in the field of gender history but rather the lack of influential theoretical perspectives that have greatly impacted the social sciences since the late 1900s. With a few exceptions, this is also the case for Scandinavian Economic History Review.

A Nordic tradition of gender economic history?

Writing a historiography of the evolving field of gender economic history in the Nordics is neither easy, nor neutral or apolitical. As Clare Hemmings (Citation2005, Citation2011) has argued, simplifications and inaccuracies are common in historiographies of Western feminism, leading to strong and linear narratives of either progress or loss, especially in relation to post structural influences. In this way, the ‘truths of the past’ becomes politics of the present. As Daniel Nyström (Citation2015) has shown, similar tendencies of contrasting earlier phases of research to newer, in order to distance oneself from a supposed non-radical past, has also been practiced in Nordic labour and gender history. Writing a historiography of gendered economic history therefore inevitably means sketching the limits of what counts as gender perspectives, and what counts as economic history. However, given that only a small share of all the empirical and theoretical contributions of women’s/feminist/gendered economic history has permeated the economic history journals, a historiography nevertheless serves a feminist purpose of inscribing and making visible this research for a broader economic historical readership.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, several Nordic networks within the broader field of women’s studies were established. Within history, dedicated sessions for women’s history were organised at the Nordic History conferences, and since 1983 Nordic conferences on womeńs and gender history have been regularly organised. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, gender history in the Nordic countries expanded rapidly, whereas economic history in general did not.Footnote2 Major differences also exist among the Nordics on how economic history is practised. Whereas economic history is a well-established field in Sweden with their own departments at the largest universities, economic and business history have to a higher degree been integrated into business schools and history departments in the other Nordic countries. Within these institutional settings and beyond, gender economic historians have still challenged mainstream (economic) history by questioning its male biases, including the tendency to prioritise productive work over reproductive; paid labour over unpaid, and reproducing ideals and notions of the female consumer and the male producer, etc.

Swedish historian Yvonne Hirdman (e.g. Citation1988, Citation2001) developed in the late 1980s a theoretical framework, partly inspired by Scott, that became very influential in the Nordic context of gender studies. She suggested to view gender relations as societal contracts that changed over time, where gender separation and the male norm served as organising principles. This meant that discourse analysis influenced by Scott and gender analysis inspired by Hirdman have tended to co-exist with (other) macro theories of power among Nordic gender historians.Footnote3 At the same time, and as in most countries, there have been disagreements about the influence of post-structural thinking in the field of history, while on the other hand critiques of exclusionary (white/heterosexual/middle class) norms in Nordic gender history (e.g. Aalto & Leskelä-Kärki, Citation2014; de los Reyes, Citation1998; Manns, 2005; Niskanen & Hassan Jansson, Citation2012).

Several Nordic historical studies of labour and women’s work were written in the early expansion of women’s history, and especially scholars working in the field or discipline of economic history were pivotal in this expansion.Footnote4 Labour was not rejected as a research theme after the 1990s, but it was no longer a heavily dominating topic of gender history in general. Noteworthy, the tradition of social history has remained strong in Finland, with studies on gender covering the time span from the Middle Ages to the late twentieth century (e.g. Hilson, Markkola, & Östman, Citation2012; Ilmakunnas, Rahikainen, & Vainio-Korhonen, Citation2017; Ojala-Fulwood, Citation2018; Rahikainen & Vainio-Korhonen, Citation2006).

Labour history with a gender perspective has covered research on topics such as gendered divisions of labour and its changes over time, salaries, education, gendered working conditions, and women’s relation to the labour movement (e.g. Ågren, Citation2017; Burnette & Stanfors, 2020; Göransson, Citation1988; Hilson, Neunsinger, & Vyff, Citation2017; Karlsson & Stanfors, 2018; Kyle, Citation1979; Ohlander, Citation2005; Östman, Citation2000; Sommestad, Citation1992; Sundevall, Citation2011; Uppenberg, 2018; Wikander, Citation1988). Early studies in women’s history focused on the modern period and on modernisation. However, economic historians also used gender as an analytical tool when re-interpreting processes of modernisation (e.g. Niskanen, 2000; Halldórsdóttir, Citation2018). Later labour-related studies have covered a wide range of time-periods, and gendered aspects of labour relations under neo-liberal reforms have been scrutinised. While class and gender have long been central analytical categories in labour history, also race/ethnicity and processes of racialisation have been analysed. However, in-depth studies of various gendered livelihoods of minorities are lacking in several Nordic contexts over time (see e.g. Larsen & Kieding, Citation2016; Wassholm & Östman, Citation2021).

Connected to labour is research on family formations and the possibility of combing parenting and (paid) labour in various time periods. To this comes the role of marriage, child labour, demographic patterns, and organisation of households (e.g. Andersson Raeder, Citation2011; Edvinsson & Nordlund Edvinsson, Citation2017; Frangeur, Citation1998; Hagemann, Citation2002; Melby, Pylkkänen, Rosenbeck, & Carlsson Wetterberg, Citation2006; Rahikainen, Citation2002; Sandvik, Citation2005; Stanfors, Citation2017). In all the Nordic countries, the role of the welfare state and its predecessors have been examined both as an enabler of gender equality and more critically in the context of exceptionalism (i.e. how the narrative of exceptional gender equality in the Nordics has built on nationalist senses and have tended to obscure oppressing structures) (e.g. Alm et al., Citation2021; Larsen, Moss, & Skjelsbæk, Citation2021). A certain body of research has also been devoted to the transformations of the welfare states and its gendered implications.

Several researchers have argued that running their own businesses has helped especially women to combine parenting with earning a living. Within the field of gender perspectives on business, studies span from highlighting successful and strong businesswomen, to small-scale entrepreneurship as strategies to survive discriminatory regulations and labour markets. To this empirical strand, the organisation of business and management, family businesses, entrepreneurial masculinities, and male power secured by exclusionary networks can be counted (see e.g. Andersson-Skog, Citation2007; Bladh, Citation1991; Heinonen & Vainio-Korhonen, Citation2018; Larsen, Citation2014; Malmén, 2019; NordlundEdvinsson, 2010; Qvist, Citation1960).

Not only the earning, but also the spending of money has been analysed by Nordic economic historians from a gender perspective. Within the history of consumption, the gendering and classing of luxury consumption and strategies for making ends meet has been examined, as well as gendered structures in the development of retail, shopping habits, and marketing (e.g. Arnberg, Citation2019; Frisk, Citation2019; Husz, Citation2015; Ilmakunnas & Stobart, Citation2017; Myrvang, Citation2009; Söderberg, Citation2001; Uotila & Paloheimo, Citation2021; Wassholm & Östman, Citation2021; Wassholm & Sundelin, Citation2018). Also, gendered consumer cultures, with practices of expressing marital and societal status with clothing has been studied as part of economic history.

Looking at the historiography of women and gender in the Nordic countries, gender continues to be an important perspective and a theme in various fields of study. However, there also seem to be quite different trajectories. While gendered perspectives, themes and theories seem to have been somewhat neglected – or marginalised – in some subfields of economic history, the interest of gender aspects of the economy are growing in adjacent fields. For instance, the history of retailing and consumption has become a large field of study during the last decades. In the Nordic region, this vibrant area of study was mainly formed by scholars of economic history. Now, scholars involved in the history of gender and consumption often work in its neighbouring disciplines, including cultural history, social history, and cultural studies. We also see a return of interest in gendered aspects of consumption, consumerism, and grass-root economies in the Nordic countries and beyond.

In previous historiographical overviews of gender and economic history, it is often suggested that the use of post-structural inspired theories and the influence of cultural history has divided gender history (who no longer use socio-economic approaches) and traditional economic history (delving deeper into econometrics) (see e.g. Blom, 2012; van NederveenMeerkerk, Citation2014; Walton, Citation2010). To uncover the possible inaccuracies or simplifications in this type of statement deserves a study of its own and is thus beyond the scope of this text. However, we want to stress that this type of narration does not only suggest that cultural history could not be studied from an economic viewpoint, it also ignores the research field that studies gender relations with the help of cliometrics. Also, feminist economics has been important for developing neoclassical economic theory used by economic historians to study historical gender relations. From the above historiography over Nordic gender economic history, we believe it is clear both that the use of gender perspectives can take various epistemological forms and that the conduct of economic history can include a variety of methodologies.

Gender gives ground for revisions and new stories

Economic history emerged in many respects as an alternative to event history – i.e. traditional political history. Therefore, Ann Laura Stoler’s (Citation2009) analytical concept of ‘non-events’ that Paulina de los Reyes uses in her article to this special issue, deserves to be highlighted. As de los Reyes (p. 4) express it, the concept of ‘non-events’ can be used to ‘define historical facts that are considered irrelevant and not worth including in official historiographies’. This therefore ties the non-event nature of economic history – i.e. searching for long-term patterns and material/structural explanations – and the non-event of gender history – i.e. searching for experiences outside the male/dominant/official historiographies – neatly together. In the intersection of these two understandings of non-events, we think a fertile soil could be found for gendered and intersectional approaches to economic history. Gender formations and relations, as well as inequality in other aspects, are non-events in the sense that they are historically resilient and have major economic consequences. Understanding them are thus key for a fuller historical understanding of change and continuities. At the same time, the understanding of historical processes is premised by the exclusion of social practices considered as non-events.

All five articles in this special issue show the importance of exploring different types of non-events of the past. The authors employ gender quite differently, however, alternating between being a descriptive and an analytical category. Regardless of this, the gender category provides ground for revisions of economic concepts, practices, and discourses as well as norms, values, and ideologies.

Following the articles of this special issue, a gender approach both provides alternative interpretations and narratives, and a more complete picture of the past. This underscores that a gender approach also provides insight and better understanding, and sometimes criticism, of the present. In her article on migrant mothers in Swedish official discourses between 1970 and 2000, Paulina de los Reyes challenges the contemporary – and neoliberal – ‘economisation’ – of the migrant mother discourse in contemporary Sweden. She combines the gender approach with other concepts and approaches, using an intersectional understanding in combination with a Foucauldian analysis of knowledge production as a form of (discursive) power. Gender is treated discursively and public reports/white papers as historical artefacts and cultural products/products of culture. She shows how public reports drew its meaning from gendered positions and gendered ideals. Methodologically, the article highlights dynamic forces and processes more than categories – gendering rather than gender, racialisation rather than race/ethnicity, and so on – in order to recognise the distinctiveness of how power operates across particular institutional fields.

The article by Björn Eriksson and Maria Stanfors covers the role of gender and migration, but in a very different way than de los Reyes. In their analysis of historical labour markets and migrant earnings, the gender approach is used together with the concept of the migrant worker, adding on to our understanding of the economic pressure that migrants experienced during industrialisation in Sweden. Focusing on labour markets and migrants’ earnings, they show there were no major difference between male and female migrant workers. As Eriksson and Stanfors contribution makes clear, the process of ‘adding a gender perspective to the story’ by using statistical methods where women become the gender marker, is by no means a mission completed. Also, with the growth of new methodological possibilities in combination with increasing digitisation of sources, we can expect a growing body of literature that give us a deeper understanding of labour market dynamics of which this article is a fine example.

Shifting from the overall to the individual, Sigrídur Mathíasdóttir and Thorgerdur J. Einarsdóttir offers a micro-historical account of the Icelandic business woman Pálina Waage. With a local perspective of female enterprise on a transnational border, they suggest that entrepreneurial subjects otherwise invisible in historical accounts can be brought to the fore. This narrower focus also enables a deeper and more complex understanding of gender where notions, meanings, and ideals of manhood and womanhood are analysed without losing sight of the wider societal, or cultural context that shaped the entrepreneurial opportunities of Icelandic women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Especially in Norway and Denmark, several studies on rural women, work, and economics were conducted in the 1980s, when the field of women's history was its childhood. In her article about decision-making in peasant households in Southwest Finland 1760–1820, Kirsi Laine returns to this important but also underexplored part of Nordic history. She studies land distribution, enclosures, and landownership, the latter a crucial construction site of gender. During a long period, landownership and land reform were major social issues and objects of state intervention in the Nordic region, especially in Finland. The implementation had various gendered outcomes defining both masculinities and femininities. In her article, Laine thus makes the gender of economic decision-making visible through studying situations when the patriarchal order of the family/firm was broken. In this way, Laine actually makes sense of one type of event in order to shed light on the non-events, as she exposes men’s symbolic capital in economic matters in the case of enclosures.

Astrid Elkjær Sørensen, Stinne Skriver Jørgensen and Maja Meiland Hansen analyse Denmark’s public wage hierarchy by comparing the gender wage gap of 1969 with the current one. The article highlights how historical reforms still structure the present. Emphasising the importance of gendered structures, practices and traditions, the article contributes to a more thorough understandings of institutions and economics as well as economic processes. Their findings suggest an enduring gendered wage gap, stressing the structural force of gender through profession and remuneration. They see gender primarily as ways of signifying power – and that a feminisation of occupations also brings a tendency of devaluation. Their article is also a contribution to the ongoing discussions in the various Nordic countries of the role of the welfare state, the public sector, and education for achieving gender equality.

Gendering (Nordic) economic history – an unfinished business

A feminist perspective, claimed Ulla Wikander in a Citation1990 article in SEHR, also means ‘denying the ‘normal’ limits of the discipline of economic history’ (p. 65). Gender perspectives in economic history has certainly continued to challenge the male bias within the field, and highlighted women’s roles in economic development, but also confronted and studied power relations between the sexes since then. However, the gendering of economic and business history and the challenging of its limits are by no means completed. Taken together, the articles of this special issue illustrate the different ways in which perspectives from the field of gender history still influence how economic history is being practiced. They thus provide not only ground for revision of established economic concepts, ideals, and practices, such as entrepreneurship and economic decision-making in agrarian societies. They also add new levels of meanings to key issues of contemporary Norden, for example understandings of gendered and intersectional implications of neoliberalisation and wage earning among migrant workers. In doing so, the articles of this special issue provide grounds for new stories of an economic past, helping people in general to better understand aspects of the present society as they experience and know it, or fear it.

Since the articles presented in this special issue all illustrate how gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power, we can echo the words of Joan Scott and state that gender is ‘a constitutive element’ in economic relations and historical change. Gender can also inform the ways we understand the concept of ‘economy’ and how we create knowledge about societies’ production and reproductions dilemmas. In addition to this, the articles give important contributions to the economic history of gender relations. Thus, the concept of gender is used both as a descriptive category and as an analytical tool. Furthermore, the analytical concept of gender is fruitfully used together with other theoretical approaches. In this way, several articles take their point of departure in a broad approach, but gendered questions remain fundamental. Showing both methodological and theoretical richness, these contributions exemplify the potential to achieve cutting-edge results. We hope that this collection will contribute to broadening the scholarly field, by its multi-layered ways to approach social and economic history. It shows the importance of complex theoretical conceptualisation of gender, economics, and power.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In titles, only one article was found using the concept masculinity in its title, published in EHR in 2013, none of the other concepts were found in titles. In full texts, the theoretical concept post-colonialism (thus not mere periodisation colonial/post-colonial) was found twice (in EHR 2009and in SEHR (2017), intersectionality was found twice (both 2018 in SEHR), masculinity was found three times (in JoEH 1993, in EEH 2011, and the one in EHR 2013 already mentioned).

2 The construction of the Nordic in relation to gender and women’s studies has also been studied from a critical perspective (e.g. Dahl, Liljeström, & Manns, Citation2016; Manns, 2005).

3 For example Lena Sommestad’s (Citation1992) work on gender, dairying and industrialization also can be mentioned as an early study that used the insights presented by Scott, but it was used in combination with other theories. These highlighted the importance of cultural notions of work, such as the strong feminine coding of milking. There have also been efforts to bridge realist and post structuralist positions. Making references to Scott, the Norwegian historian Gro Hagemann (Citation1994) underlined the need to combine post structuralism with social science theory. Swedish economic historian Anita Göransson (Citation1998) published an article entitled ‘Mening, makt och materialitet’ – an attempt to combine realist and post structuralist positions. She introduced the term maktbas (power basis) and underlined the pivotal role the connection between changing social power relations and masculinity.

4 For example, the Swedish economic historian Ulla Wikander studied the changing gendered divisions of labor and changing work practices, while the Norwegian historian Sølvi Sogner scrutinised the importance of the household. In Finland, Pirjo Markkola studied working class families at the turn of the twentieth century.

References

- Aalto, I., & Leskelä-Kärki, M. (2014). Jatkumoita ja uusiakäänteitä: Sukupuolihistoria 2010-luvulla. Sukupuolentutkimus-Könsforskning, 24(1).

- Alm, E., et al. (2021). Pluralistic struggles in gender, sexuality and coloniality: Challenging Swedish exceptionalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Andersson Raeder, J. (2011). Hellre hustru än änka: äktenskapets ekonomiska betydelse för frälsekvinnor i senmedeltidens Sverige (Disserattion). Stockholmsuniversitet.

- Andersson-Skog, L. (2007). In the shadow of the Swedish welfare state: Women and the service sector. Business History Review, 81(3), 451–470.

- Arnberg, K. (2019). Selling the consumer: The marketing of advertising space in Sweden, ca. 1880–1939. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 11(2), 142–116.

- Ågren, M. (Ed.). (2017). Making a living, making a difference: Gender and work in early modern European society. Oxford University Press.

- Bladh, C. (1991). Månglerskor. Att sälja från korg och bod i Stockholm 1819–1846. Stockholmia.

- Blom, I. (2014). Gender history: Then, now and in the future. In Manns, U. & Sundevall, F. (Eds.), Methods, interventions and reflections: report from the X Nordic women’s and gender history conference, Bergen, Norway, August 9–12, 2012. Makadam Förlag .

- Dahl, U., Liljeström, M., & Manns, U. (2016). The geopolitics of Nordic and Russian gender research 1975–2005. Södertörn University.

- de los Reyes, P. (1998). Det problematiska systerskapet: om ‘svenskhet’ och ‘invandrarskap’ inom svensk genushistorisk forskning. Historisk Tidskrift, 118(3), 335–356.

- Edvinsson, R., & Nordlund Edvinsson, T. (2017). Explaining the Swedish ‘housewife era’ of 1930–1970: Joint utility maximisation or renewed patriarchy? Scandinavian Economic History Review, 65(2), 169–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.2017.1323671

- Frangeur, R. (1998). Yrkeskvinna eller makens tjänarinna? Striden om yrkesrätten för gifta kvinnor i mellankrigstidens Sverige (Dissertation). Göteborg.

- Frisk, L. M. (2019). “Naiseni on omaitsensä”: Rakennettuluonnollisuus, ruumiillisetkulutustuotteet ja nuortensukupuoltenmurros 1961–1973. Nuorisotutkimusseura Nuorisotutkimusverkosto.

- Göransson, A. (1988). Från familj till fabrik: teknik, arbetsdelning och skiktning i svenska fabriker 1830-1877. Diss: Umeå University.

- Göransson, A. (1998). Mening, makt och materialitet. Häften för kritiska studier, 31(4), 3–26.

- Hagemann, G. (1994). Postmodernismen en användbar men opålitlig bundsförvant. Kvinnovetenskapligtidskrift, 15(3), 19–34.

- Hagemann, G. (2002). Citizenship and social order: Gender politics in twentieth-century Norway and Sweden. Women’s History Review, 11(3), 417–429.

- Halldórsdóttir, E. H. (2018). Beyond the centre: Women in nineteenth-century Iceland and the grand narratives of European women’s and gender history. Women’s History Review, 27(2), 154–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2017.1303888

- Heinonen, J., & Vainio-Korhonen, K. (Eds.). (2018). Women in business families: From past to present. Routledge.

- Hemmings, C. (2005). Telling feminist stories. Feminist Theory, 6(2), 115–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700105053690

- Hemmings, C. (2011). Why stories matter: The political grammar of feminist theory. Duke University Press.

- Hilson, M., Markkola, P., & Östman, A.-C. (Eds.). (2012). Co-operatives and the social question: The Co-operative movement in Northern and Eastern Europe, c.1880-1950. Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press.

- Hilson, M., Neunsinger, S., & Vyff, I. (Eds.). (2017). Labour, unions and politics under the North Star: The Nordic countries, 1700-2000. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Hirdman, Y. (1988). Genussystemet: teoretiska funderingar kring kvinnors sociala underordning. Uppsala: Maktutredningen.

- Hirdman, Y. (2001). Genus: om det stabilas föränderliga former. Liber.

- Husz, O. (2015). Golden everyday: Housewifely consumerism and the domestication of banks in 1960s Sweden. Le Mouvement Social, 250(1), 41–63.

- Ilmakunnas, J., & Stobart, J. (Eds.). (2017). A taste for luxury in early modern Europe. Display, acquisition and boundaries. Bloomsbury.

- Ilmakunnas, J. M., Rahikainen, S. M., & Vainio-Korhonen, K. (Eds.). (2017). Early professional women in Northern Europe, c. 1650–1850. Routledge.

- Kyle, G. (1979). Gästarbeterska i manssamhället: studier om industriarbetande kvinnors villkor i Sverige. LiberFörlag.

- Larsen, E. (2014). Kjønn og næringslivshistorie. In E. Ekberg, M. Lönnborg, & C. Myrvang (Eds.), Næringslivoghistorie (pp. 268–297). Pax Forlag.

- Larsen, E., & Kieding, V. (2016). Mixed feelings: Women, Jews, and business around 1900. Scandinavian Journal of History, 41(3), 350–368.

- Larsen, E., Moss, S. M., & Skjelsbæk, I. (Eds.). (2021). Gender equality and nation branding in the Nordic Region. Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003017134

- Manns, U. (2009). En ros är en ros är en ros: konstruktionen av nordisk kvinno- och genusforskning. Lychnos, 283–314.

- Melby, K., Pylkkänen, A., Rosenbeck, B., & Carlsson Wetterberg, C. (2006). Inte ett ord om kärlek: äktenskap och politik i Norden, ca 1850-1930. MakadamFörlag.

- Mills, A. J., & Williams, K. S. (2021). Feminist frustrations: The enduring neglect of a women’s business history and the opportunity for radical change. Business History. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2021.1896706

- Myrvang, C. (2009). Forbruksagentene. Slikvekket de kjøpelysten. Pax Forlag.

- van NederveenMeerkerk, E. (2014). Gender and economic history. The story of a complicated marriage. TSEG - The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History, 11(2), 175–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.18352/tseg.137

- Niskanen, K. (Ed.). (1998). Föreställningar om kön. Ett genusperspektiv på jordbrukets mekanisering. Stockholm Studies in Economic History.

- Niskanen, K., & Hassan Jansson, K. (2012). Genushistoriens utmaningar – kan Clio flyga högt och fritt? Scandia, 76(2), 9–14.

- Nordlund Edvinsson, T. (2010). Broderskap i näringslivet: en studie om homosocialitet i Kung Orres jaktklubb 1890-1960. Lund: Sekel.

- Nyström, D. (2015). Innan forskningen blev radikal: en historiografisk studie av arbetarhistoria och kvinnohistoria. Umeå universitet.

- Ohlander, A.-S. (2005). Kvinnors arbete. 1. uppl. Stockholm: SNS förlag.

- Ojala-Fulwood, M. (Ed.). (2018). Migration and multi-ethnic communities: Mobile people from the late middle ages to the present. De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

- Östman, A.-C. (2000). Mjölk och jord: om kvinnlighet, manlighet och arbete i ett österbottniskt jordbrukssamhälle ca 1870-1940 (Dissertation). Åbo Akademi, Åbo.

- Qvist, G. (1960). Kvinnofrågan i Sverige 1809-1846: studier rörande kvinnans näringsfrihet inom de borgerliga yrkena. Diss. Göteborg: Univ.

- Rahikainen, M. (2002). First-generation factory children: Child labour in textile manufacturing in nineteenth-century Finland. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 50(2), 71–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.2002.10410809

- Rahikainen, M., & Vainio-Korhonen, K. (2006). Työteliäs ja uskollinen: naisetpiikoina ja palvelijoina keskiajalta nykypäivään. SKS.

- Sandvik, H. (2005). Decision-making on marital property in Norway, 1500-1800. na.

- Scott, J. W. (1986). Gender. A useful category of historical analysis. The American Historical Review, 99(5), 1055–1075.

- Söderberg, J. (2001). Röda läppar och shinglat hår: konsumtionen av kosmetika i Sverige 1900-1960. Ekonomisk-historiska institutionen.

- Sommestad, L. (1992). Från mejerska till mejerist. En studie av mejeriyrkets maskuliniseringsprocess. Arkiv förlag.

- Stanfors, M. (2017). Mellan arbete och familj: ett dilemma för kvinnor i 1900-talets Sverige. 2nd ed. Studentlitteratur.

- Stoler, A. L. (2009). Along the archival grain: Epistemic anxieties and colonial common sense. Princeton University Press.

- Sundevall, F. (2011). Det sista manliga yrkesmonopolet: genus och militärt arbete i Sverige 1865–1989. Makadam förlag.

- Uotila, M., & Paloheimo, M. (2021). Textiles in blue: Production, consumption and material culture in rural areas in early-nineteenth century Finland. Scandinavian Economic History Review. Early online. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.2021.2010593

- Walton, J. K. (2010). New directions in business history: Themes, approaches and opportunities. Business History, 52(1), 1–16.

- Wassholm, J., & Östman, A. (Eds.). (2021). Att mötas kring varor: Plats och praktiker i handelsmöten i Finland 1850–1950. Svensk litteratursällskapet i Finland.

- Wassholm, J., & Sundelin, A. (2018). Emotions, trading practices and communication in transnational itinerant trade: Encounters between ‘Rucksack Russians’ and their customers in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Finland. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 66(2), 132–152.

- Wikander, U. (1988). Kvinnors och mäns arbeten. Gustavsberg 1880–1980. Lund: Arkiv.

- Wikander, U. (1990). On women's history and economic history. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 38(2), 65–71.