ABSTRACT

In the Swedish context, fairly little is known about the variation in the level and composition of female wealth over the long term. This paper aims to contribute to filling this gap, emphasising the main features of unmarried women's wealth and assessing how it evolved during the second half of the nineteenth century. To this end, the study relies on a sample of about 500 probate inventories drawn up in the city of Uppsala between 1850 and 1910. The second half of the nineteenth century was a period of transformation encompassing several aspects of Swedish society. The change included the economic and financial structure of the country, as well as the legal framework and the labour market. The research proves that unmarried women's wealth increased in the period here analysed, even though dissimilarly between spinsters and widows. Their wealth changed also from a qualitative point of view, as shown by the increasing presence of specific assets such as real estate and stocks recorded in their inventories. Among the several factors that can be retraced at the origins of this phenomenon, the development of a more equal legal framework and the evolution of the housing market seemed to have played a major role.

1. Introduction

In the Swedish context, there is considerable research focusing on the historical evolution of personal wealth and inequalities.Footnote1 Not much of it, however, centres specifically on the variation in the level and composition of female wealth in the long term. This topic is of major interest, and it sheds light on several key issues such as female property and inheritance rights, as well as women's independence in implementing savings and investment strategies.

The present research aims precisely to contribute to filling this gap. It examines a sample of 488 probate inventories drawn up in Uppsala between 1850 and 1910 in order to retrace the variations in the quantity and quality of women's wealth.Footnote2 The city represents an ideal case study for this research: it was a major industrial centre and one of the biggest railway junctions in the country; moreover, its archives offer enough sources to carry out a long-term analysis. The main goal of the paper is to show how single women's wealth evolved qualitatively and quantitatively in relation to three specific phenomena that can be retraced in this period: the general phase of economic development of the entire country, the transformation of the labour market and the evolution of the legal framework (especially linked to property and inheritance rights).

After 1850, Sweden began on a long process that led it from being one of the poorest countries in Europe to one of the most developed (Lindgren, Citation2002; Ögren, Citation2009; Ögren, Citation2010; Sandberg, Citation1978; Sandberg, Citation1979). In this period, the evolution of the financial system benefited from the introduction of new instruments and institutions, which gave essential support for industrial expansion. The banking sector progressively developed and eventually came to dominate the credit market, which became increasingly impersonal and institutionalised. Research suggests that many young, unmarried women benefitted from the introduction of commercial banks, in the context of what has been defined as the ‘commercial banks revolution’ (Petersson, Citation2009, p. 259). This overall economic growth engendered a series of positive effects, such as a widespread increase in prosperity and an expansion of credit. Nonetheless, it also led to negative outcomes such as, for instance, the rise in inequality between and within social classes (Bengtsson & Svensson, Citation2019; Bengtsson, Missaia, Olsson, & Svensson, Citation2018). In the context of such dramatic social transformation, the changes in the composition of assets owned by women and the evolution of the gender wealth gap both emerge as topics of major interest.

In the last forty years of the nineteenth century, the average wage of the urban middle classes rose consistently. This phenomenon, known as the ‘bourgeois revolution’, involved especially those who were employed in educated professions – such as teachers, nurses, lawyers, and the like. As Bengtsson and Prado have put it, ‘these groups coalesced into a ‘new middle class’, typically with notions of themselves as quite cultivated and distinguished’ (2020, p. 93). Many women were occupied in such professions, especially employed as nurses and teachers; the rise in the average wage had many positive effects, and contributed to the process of accumulation which benefitted the women belonging to the lower and middle strata.

Inheritance and property rights are also likely to influence qualitative and quantitatively women's wealth. Spinsters, widows and married women not only had diverse rights, but they also enjoyed different degrees of freedom in managing their own assets (Ågren, Citation2009; Bennett & Froide, Citation1999; McCants, Citation2002; Spicksley, Citation2018). At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Swedish marital status, which had previously envisaged a bilateral property system, began to develop in a similar way to the British one, where a wife's belongings became the total and unconditional property of her husband (Ågren, Citation2009, pp. 12–15). The civil code introduced in 1734 made no distinction between the belongings of either spouse, and the marital estate became a unit of property at the husband's complete disposal. However, during the second half of the nineteenth century, the public authority intervened several times to regulate property rights and inheritance practices. The legislation became increasingly gender-equal and safeguarded the possibility of unmarried and married women managing their assets independently.

The present work focuses on unmarried women for at least two main reasons. First, the marital status of individuals greatly influenced their economic lives and patrimonial strategies. This is especially true in the case of women, who, still today, suffer a gender gap in employment and wealth accumulation (see for instance Kleven, Citation2022; Rothstein, Citation2012; Warren, Rowlingson, & Whyley, Citation2001). Unmarried individuals tend to accumulate less wealth than married ones, and, despite the fact that age has usually a positive effect on wealth accumulation, widowhood tends to impact negatively on women's net worth (Denton & Boos, Citation2007, p. 116; Di Matteo, Citation2008; Ruel & Hauser, Citation2013). Second, married women are not included because of the nature of the sources here analysed. Studying married men's or married women's wealth is akin to studying the entire household (Moring, Citation2007). Considering that men were the heads of their families, the patrimonial strategies and the composition of wealth recorded in the probate inventories of married women coincide to some extent with that of their husbands. However, married couples (including both men and women in a single category) have been considered a useful benchmark for comparisons.Footnote3

This study has found that several factors affected women's wealth. First, as a result of the economic development, all individuals became richer on average between 1850 and 1910, regardless of their gender or marital status. Savings and commercial banks provided unmarried women with a safe and profitable place to deposit their money, and the volume of deposits increased considerably over time. Second, the evolution of the labour market and the so-called ‘bourgeois revolution’ has positively affected the wealth of all individuals despite their social origins. This is true also for spinsters, many of whom were employed as maids. Third and finally, real estate emerged as the most important factor in determining personal wealth. It constitutes the main cause for spinsters’ wealth increases between 1890 and 1910, when this group recorded their real properties in their inventories for the first time. The evolution of a more equal inheritance and property rights played a critical role in this regard. On the other hand, widows’ share of stocks grew between 1870 and 1890. This is similar to what happened in nineteenth-century England, where widows compensated for their exclusion from the labour market by investing in stocks (Green, Owens, Swan, & van Lieshout, Citation2011, p. 68).

This study focuses on a single city and a limited number of inventories, and it does not aim for generalisations involving the whole country. However, it allows us to reach the goals of the paper, and assess how wealth evolved qualitatively and quantitatively in relation to three specific phenomena: economic development, the transformation of the labour market and the evolution of the legal framework. This is only a first step in that direction, which will hopefully be followed up by future research on this topic.

2. Women, wealth, and probate inventories

2.1. Context and legal framework

Uppsala, located about 70 km north of Stockholm, is one of the oldest cities in Sweden. It was the ecclesiastical centre of the country since the twelfth century and, after the foundation of the university in 1477, one of its most important cultural hubs. From an economic point of view, Uppsala was a prominent industrial centre, as well as one of the biggest railway junctions in Sweden. The city undoubtedly benefitted from its proximity to the capital, which acted as a driver for economic growth. The number of inhabitants of Uppsala proves to be a good benchmark to describe the general situation, as it increased strongly throughout the nineteenth century, growing from about 4.000 individuals in 1800 to almost 26.000 in 1910 (see ).

Table 1. Uppsala, demographic structure; * % in relation to the total no. of inhabitants in the city; to calculate % I used national statistics. Source: Statistiska Centralbyrån (Citation1969).

Uppsala benefitted from the general phase of economic expansion of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as did almost all other parts of the country. Savings and commercial banks, which were introduced during the 1820s and 1830s respectively, played a critical role in spreading a new and different concept of savings as an essential prerequisite for economic development (Lindberg, Citation2007, p. 3; Sandberg, Citation1978, p. 680). Even if, overall, the peer-to-peer credit market remained the most important source of funding all through the nineteenth century, the introduction of banks favoured a more organised collection and redistribution of savings, and crucially, a more efficient allocation of capital. This ‘financial revolution’ played a major role in supporting and fostering the industrialisation process and in the evolution of a financial system that has been defined as ‘both effective and inclusive’ (Petersson, Citation2009, p. 265; see also Magnusson, Citation2000; Ögren, Citation2009; Ögren, Citation2010; Sandberg, Citation1979).

This process left many traces in the sample of probate inventories. Bank deposits recorded are very few at least until 1870, and all of them were made in savings banks. Many of these accounts belonged to unmarried women, especially widows and, to a lesser extent, spinsters. At the turn of the twentieth century, by contrast, the number of deposits increased consistently, especially in commercial banks, triggering a strong rise in the overall volume of money deposited. In Stockholm, the total number of deposits in commercial banks had already surpassed those in savings banks by 1868. A study demonstrates that approximately 50 per cent of depositors in the Stockholm's Enskilda Bank were middle and upper-class women. A very large share of them (70–75 per cent) were young, between 16 and 25 years old, and unmarried (Petersson, Citation2009, p. 259).

This phenomenon, which is known as the ‘commercial banks revolution’, happened in Uppsala about 30 years later, between 1890 and 1910. As in Stockholm, commercial banks became, over time, the preferred investment for young unmarried women, and the average age of those who have a bank account in their probate inventory gradually lowers: in 1870 they were all in their thirties or older, in 1890 they were at least in their twenties, and for the first time in 1910 we find bank accounts in the probate inventories of spinsters under 20 years of age. This does not imply that young women started managing their money independently, of course; at least, it means that commercial banks were a valuable investment opportunity for these young and (still) not married women.

Property rights are a key to economic development. Full property rights involve three aspects: the right to use the property, the right to keep the gains derived from it for oneself, and, last but not least, the right to change its form and substance (for instance, to sell it; see Göransson, Citation1993, p. 12). It is well known that all women suffered during most of their lives from a lack of rights, and on this score, Sweden proves no exception. According to the Swedish Code of 1734, widows could enjoy full legal rights after the death of their husbands and were therefore totally comparable to men (Holmlund, Citation2008, p. 240; Petersson, Citation2009, p. 258). On the other hand, none of these rights belonged to spinsters and married women: they were placed under the control of a male guardian, usually their father or husband, who had almost full control over their assets.Footnote4

All over Europe, the literature recounts many examples of women who took an active part in commerce and craft, and who participated in credit markets as borrowers or lenders (see for instance Bellavitis, Citation2018; Dermineur, Citation2014; Laurence, Maltby, & Rutterford, Citation2009; Petti Balbi & Guglielmotti, Citation2010). However, such cases are sometimes the result of a contradiction between legal theory and actual practice. In many cases, a right is not just the privilege to do something, as it involves a change in social conventions and ethical norms; in the case of female rights, it is also an attempt to redefine the relationship between two parts of the society, to solve a social conflict. This process of redefinition began in Sweden during the second half of the nineteenth century, when more and more rights were granted to women, especially to spinsters and married women, who were the most disadvantaged by the pre-existing legal framework.

For instance, guardianship over spinsters was progressively abolished between 1858 and 1863, fully in 1872; from 1884, spinsters could manage autonomously their assets from the legal age of twenty-one, while, on the other hand, married women had to wait until 1921. However, from 1874, married women had at least the right to dispose of their own income from work (Sweden was the first country on the European continent to grant this right; see Göransson, Citation1993, p. 12). After 1845, inheritance law became more equal from a gender point of view. In fact, before that date, all children inherited from their parents, but sons usually received much more than daughters, especially in rural areas; afterwards, all children had equal rights under the law, thus inheriting the same amounts of both fixed and movable assets (Dribe & Lundh, Citation2005, p. 294; Holmlund, Citation2008, p. 240). Altogether, we should expect to find the strongest changes in the probate inventories of spinsters, while widows’ wealth should follow more closely the general trend: sections 3 and 4 will clarify this issue.

The effects of economic development in Sweden on the evolution of personal wealth should be easy to assess in the sample of probate inventories. It is more difficult to evaluate the effect of the evolution of the legal framework. Sometimes, laws certify situations already ongoing, and solve a need that already exists among the population; in other cases, they anticipate this need. Laws might have been promulgated at the same moment in the whole country, but the results of the legal changes did not have the same effects everywhere and at the same moment. Moreover, probate inventories are slower in detecting these changes, because they record the wealth of people at the time of their death. Therefore, we should not expect an immediate cause–effect relation between the evolution of the legal framework and individual wealth, but a more delayed reaction.

2.2. Studying the past through probate inventories

Probate inventories are veritable ‘windows’ on the past, as they allow historians to get an overview of the lives of individuals, even if just at the moment of their death. Their primary goal was to record a set of information points about a deceased person, so as to facilitate the correct apportioning of their inheritance, the repayment of their debts and the collection of credits they had gathered throughout their lives (Kuuse, Citation1974, p. 22). Probate inventories have proved to be an essential source for the study of the economic and social history of past societies. They contain relevant information to better understand the composition and distribution of wealth, as well as to retrace the material life of people (Shammas, Citation1990; Weatherill, Citation1988). They have also been essential in assessing the rate of development of credit markets, the extension of peer-to-peer networks and in evaluating the degree of female involvement in credit relations (McCants, Citation2006 and Citation2007; Dermineur, Citation2014).

The Swedish Civil Code of 1734 made it compulsory to draw up an inventory for each deceased person (Markkanen, Citation1978, p. 67). The law established that heirs could be held personally liable for the debts of the deceased if they had unlawfully disposed of their inheritance before the inventory was arranged. According to Lindgren (Citation2002), this was one of the most important economic incentives to draw up inventories (p. 818). They were usually compiled very carefully, recording detailed information about different kinds of assets: they report precise information about the net value of several assets, such as land, debits and credits, something that proves very useful when analysing the evolution of personal wealth, as this paper aims to do.

The present research is based on a sample of 488 probate inventories, collected through four different surveys between 1850 and 1910 (1850, 1870, 1890 and 1910). Probate inventories of the university staff have been included, but not those of the nobility, which are stored in the archives of specific courts. The sample contains all inventories related to individuals deceased in the four years here analysed, as well as those who died in the year immediately preceding whose inventories have been recorded in the following one (1849-1850, 1869-1870, 1889-1890, 1909-1910). In fact, even if the law specified that the inventory had to be compiled up to three months after the death, this was not always the case, and sometimes the clerk drew up inventories of individuals deceased months or even years before. Moreover, since there were few inventories recorded in 1850, 1851 has been considered as well (see ).

Table 2. Composition of the sample: number of probate inventories per gender and marital status.

The number of inventories grows over time (from 46 in 1850–136 in 1910), as a direct consequence of the demographic development, and therefore the increase in the number of deaths (the representativity is roughly stable, see ). Women are slightly more represented than men, but most of them were married and cannot be considered for analysis of individual wealth. In fact, studying married men or married women is akin to studying the entire household (Moring, Citation2007). Men were usually the head of the family: therefore, to analyse the patrimonial strategies and the composition of the wealth of married women starting from their probate inventories means to some extent studying that of their husbands. This is why this study focuses on spinsters and widows, while married couples are considered a benchmark for useful comparisons.

Table 3. Comparison between the number of inventories and deceased people (more than 20 years old) M: men W: women. Sources: footnote 2; The Demographic Data Base, CEDAR, Umeå University (1790-1850); BiSOS årsberättelse 1870K, bilaga 1, s. 19; BiSOS årsberättelse 1890K, bilaga 1, s. viii; BiSOS årsberättelse 1910K, bilaga 1, s. vi. * only inventories of people who died in these 4 years.

Widows and spinsters are a significant group among women, while we cannot say the same for unmarried men (bachelors and widowers). This is mainly due to two different phenomena: first, men live less than women on average, and it is likely that their wives are still alive when they die. Moreover, it has been shown in other contexts that widowers tended to remarry more frequently than widows, who, on their part, could not – or chose not to – do so, either because of their age or on account of other social reasons.Footnote5 Finally, bachelors are on average very young, which suggests that they died just before reaching the marriage age (which is not the case for spinsters).

Understanding the characteristics of the sample is extremely useful in clarifying the limits and potential of this analysis. It is well known that one of the major challenges in working with probate inventories involves gauging how representative they are compared to the living population: first, we need to assess the percentage of deceased that had a probate inventory. To do that, we can just compare the number of deceased people with the number of inventories in the same year. As we can see in , between 43 and 52 per cent of those who died in each year have a probate inventory: therefore, the sample includes roughly half of the deceased population.Footnote6

The external validity of the sample (in other words, how well the sample represents the living population) constitutes an additional challenge to this kind of analysis. Probate inventories tend to include older individuals, simply because more deaths occur among the elderly than among the young. At the same time, the age of people is usually strongly correlated with their wealth (with some differences, as we will see): this means that the population described in the sample is not just older but probably also richer than the living one. There is also an important difference from an economic and social point of view, since the higher social classes, those who had assets to be inventoried, and probably some creditors claiming at least part of them, are much more likely to be represented than the lower ones (Keibek, Citation2017; Lindgren, Citation2002; Markkanen, Citation1978). Not by chance, the members of the higher classes (bourgeoisie) are strongly over-represented, while the lower ones are under-represented (especially artisans and both skilled and unskilled workers). For that reason, it has been stated that the study of inventories produces a ‘distorted impression of changes in the wealth of the entire population’, effectively neglecting the lower part of society (Markkanen, Citation1978, p. 82).

While we have to keep in mind the features of the sample we are working with, it has to be specified that the ‘unbalanced’ representation of the society does not represent a problem for the present investigation itself.Footnote7 This paper analyses the variations over time in the quantity and quality of the wealth owned by never-married women and widows, from an interclass perspective. Moreover, the sample includes many women who belonged to the lower strata of the society, as is highlighted in section 2. Finally, the paper does not offer any general statistics, and it only tries to assess what is likely to have caused these changes in wealth, focusing in particular on three different phenomena, the economic development, and the evolution of both the labour market and property rights. Probate inventories prove to have many flows, but they often constitute one of the few available options in the study of certain specific categories or groups such as unmarried women, who are often neglected in other kinds of sources.

The correct evaluation of assets is another issue that has always negatively affected studies based on probate inventories. First of all, all values have been corrected for inflation using the CPI index available in Edvinsson and Söderberg (Citation2010).Footnote8 Then, the value of specific assets has been adjusted to make the results of the analysis more reliable. In Swedish probate inventories, the value of the real estate was taken from tax registers, which were usually slower than the market in recording changes in the value of these assets. Therefore, because of the sharp rise in prices, especially of land, which occurred throughout the nineteenth century, the values reported in the inventories are generally underestimated (Bengtsson & Svensson, Citation2019, p. 132). Although scholars have claimed that this problem concerned rural more than urban contexts, the argument here is that it is better to take some kind of countermeasure.Footnote9 According to other research on the subject, we need to consider a sales-to-taxable-value price ratio of 1.45 in 1850, which gradually decreased – perhaps due to a more efficient and timely updating of tax registers – to 1.2 in 1910 (Bengtsson & Svensson, Citation2019, p. 132; in Walndenström, Citation2017).

Other types of assets with similar evaluation issues are movables and livestock, which were also undervalued very often. Comparing the value of a series of items listed in some probate inventories with those of the same objects sold through public auctions, Murhem, Karlssom, Nilsson, and Ulväng (Citation2019) found between 1728 and 1900 a mean undervaluation of −36 per cent / + 3 per cent (p. 88). Isacson (Citation1979; in Murhem et al., Citation2019) has shown that moveable property was undervalued by around 25 per cent in probate inventories from the Swedish county of Kopparberg between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (p. 139), while Kuuse found a similar percentage for agricultural equipment and cattle in Uppsala, Kronoberg and Malmohus (Murhem et al., Citation2019, p. 91). I will therefore use an adjustment of 33 per cent for both movables and livestock, as Isacson and Kuuse have suggested, and in line with the assessment by Murhem et al.

Finally, the sample needs to be normalised excluding outliers that could bias the results. Identifying an outlier is not always easy, and not even statistical methods prove to be fully reliable. This is because data have to be evaluated in relation to their context, and according to the variables considered in the analysis. Four inventories out of 488 have been excluded, because their value was too high (3) or too low (1) with respect to the average. Outliers have been selected considering both the whole sample, as well as the single categories (gender and marital status) to which they belonged. There is little doubt that their value was out-of-scale in relation to the others, and they would have compromised the analysis.Footnote10

3. Wealth distribution over time

Although few individuals died without any debt, inventories with a positive net value are the clear majority, with a trend that tends to increase over time. Out of a total of 484 inventories (outliers excluded), only 85 (17.57 per cent) have a negative net value, and they are equally distributed among all socio-professional statuses. Married individuals are more exposed to the risk of dying with debts (48 inventories), followed by widows and widowers (23 inventories) and the never-married (14). This situation probably reflects different life-cycle savings strategies. Many studies focus on how the distribution of wealth changes according to the age of individuals. For instance, a hump-shaped curve that declines over time is typical in the context of life-cycle savings. In short, wealth reaches its peak just before retiring, and then it gradually decreases as the individual uses their resources to survive. In other cases, the hump-shaped curve does not gradually decline over time, but it increases or remains stable; in that case, the money is earmarked for bequests (Di Matteo, Citation2008, p. 146). However, since nobody quite knows their own date of death, everybody usually leaves some kind of wealth, big or small.

The picture that emerges from the study of probate inventories is not easy to interpret. In 1850 and 1870 the average net wealth of married individuals seems to be correlated to age and increases over the course of life. However, in 1890 and 1910, it grows after the age of 30 and decreases between the ages of 60 and 70. The result is a reversed U curve typical of the lifecycle saving strategy. It is maybe the result of a change in the saving strategies through the nineteenth century, similar to what has been highlighted in other contexts.Footnote11

On the other hand, widows found themselves in another phase of their life cycle. Their average net wealth peaks between the ages of 60 and 80, and then it decreases quickly, also because of a higher indebtedness. The positive correlation between age and debts suggests that older widows were more likely to borrow to survive or to maintain their standard of living. Finally, spinsters’ data are more difficult to interpret since on average they are not as old as widows, nor as young as bachelors. Moreover, the low number of inventories makes it difficult to highlight patterns, especially in 1850 and 1870. The distribution of wealth is quite flat at least until 1890: in 1910, their wealth pattern roughly follows that of widows, since it peaks later in the life cycle and decreases quite fast immediately after.

In the sample (outliers excluded) there are assets recorded for a total net value of 5,694,135.34 crowns (the gross wealth – without considering liabilities and other expenses – is 8,129,742.93 crowns).Footnote12 If we consider the average value of inventories in the period (), we can notice a progressive increase in individual wealth at death. Walndenström (Citation2017) claims that per capita wealth growth increased in Sweden from less than 0.5 per cent in the first half of the nineteenth century to 1.5 and to 3 per cent between 1850 and the 1970s (p. 288). Returns on the Stockholm stock exchange and housing prices were among the main reasons for this phenomenon. In particular, housing prices strongly increased in the larger Swedish cities between 1875 and the 1900s (Söderberg, Blöndal, & Rodney, Citation2014), and, as data suggests, this happened in Uppsala too. Real estate was in fact at the base of the strong increase in the net value of inventories between 1850 and 1890, as well as of its fall in the following twenty years.Footnote13

Table 4. Average net value of inventories in kronor; *adjusted for inflation using the CPI available in Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2010, p. 1914 = 100%; outliers excluded.

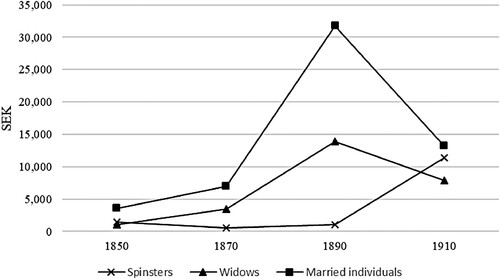

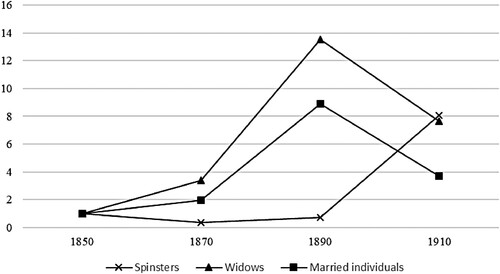

shows how the average wealth of inventories of spinsters, widows and married individuals (both men and women) evolved in the period under analysis. The effects of the Swedish economic development – already highlighted in – are quite clear, since the overall level of wealth tends to increase between 1850-1910, even though in different ways. The relationship between the different lines that compose reflects a situation already highlighted by the literature. Unmarried individuals – in particular women – were on average poorer than couples. In fact, two spouses could pool their resources and share the expenses, with a generally positive effect on the level of wealth. Spinsters had to deal with the negative social stigma of living in what was perceived as an unnatural situation – that of having never been married. Widows lived instead in a slightly better condition since after the death of their husbands they enjoyed the same full rights as men. Married individuals and widows are characterised by a similar trend: the average net value of their inventories peaks in 1890 and declined significantly in 1910. On the other hand, spinsters’ wealth decreased in the first forty years and increased significantly in the last twenty years.

Figure 1. Average net value of inventories, spinsters, widows and married individuals (both men and women); adjusted for inflation using the CPI available in Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2010, p. 1914 = 100%.

seems to suggest that the turn of the twentieth century was a phase of transition for spinsters in Uppsala. The data on widows is more problematic: even though their wealth increased by a factor of four in 60 years (), between 1890 and 1910 they were probably hit by a fall in housing prices, which halved their average wealth (Söderberg et al., Citation2014). As we can see from , spinsters’ wealth increases eightfold between 1890 and 1910. The gender wealth gap seems to have started to narrow down, although it remained quite large in absolute terms. So, what happened in the second half of the nineteenth century – and more specifically between 1890 and 1910 – that could explain this trend?

Figure 2. Average value of inventories, married individuals, spinsters and widows, indexed 1850 = 1.

Demographic dynamics could greatly influence inheritance, savings and investment patterns. Licini (Citation2011) highlights that at the end of the nineteenth century, Milanese spinsters were becoming increasingly richer. She claims that the origins of this phenomenon are to be found in the lack of male heirs, thus determining a greater number of women inheriting great fortunes. Something similar also happened in nineteenth-century England, where the constant surplus of females over males meant that a significant number of middle-class women were excluded from the marriage market. Given the difficulties for such women to undertake paid employment, they needed to generate income from investment (Berg, Citation1993; Green & Owens, Citation2003; Rutterford & Maltby, Citation2006, pp. 116–118).Footnote14 However, in Uppsala there is no evidence of a similarly marked surplus of women, not even when considering the whole country (Statistiska Centralbyrån, Citation1969, p. 57). Between 1850 and 1910 spinsters were roughly about 30 per cent of the total population, between 9.5 per cent and 10 per cent if we consider just those above the age of 20. Therefore, even though the absolute number of spinsters’ probate inventories grew over time, they always represent a stable percentage of the total sample in each survey.

A variation in income due to the transformation of the labour market could be another possible explanation for the increase in the wealth recorded in the probate inventories of spinsters. The occupational status of individuals have been considered as one of the factors that has stronger consequences on wealth, even more than inheritance (Ruel & Hauser, Citation2013, p. 1157). Therefore, the level of inclusiveness of the labour market and the rate of employment of women could be of critical importance in the process of wealth accumulation. As I already pointed out, between the 1860s and the 1880s, the structure of the Swedish labour market changed consistently. This process, called the ‘bourgeois revolution’, had several origins, among which was a strong increase in the demand for skilled, salaried employees, partly due to the modernisation of state bureaucracy, and the consequent mismatch between high demand and much lower offers (Bengtsson & Prado, Citation2020, pp. 105–107).

As a consequence of this ‘bourgeois revolution’, middle-class wages grew substantially, widening wage differentials relative to low-paid professions, such as construction workers and farmers. This gap peaked in the 1880s and then declined throughout the twentieth century: in the 1900s, a regular teacher still earned twice as much as an unskilled worker; the gulf was even wider in the case of a clerk, who might earn up to 3.3 times more compared to his unskilled counterpart (Bengtsson & Prado, Citation2020, p. 98). This process could be important for the present analysis, as it might throw light on the growth in the overall wealth of spinsters. In fact, many women were employed in professions that required advanced education, but usually did not pay very well, such as nurses, teachers, etc. (Ruel & Hauser, Citation2013, p. 1173). Those were exactly the kind of professions that began yielding increasingly rates during the ‘bourgeois revolution’: if women's salaries began to rise, they probably had more resources to save and invest, which, in turn, would be recorded in their inventories.

Probate inventories do not allow us to evaluate the whole working life of individuals. However, we can compare the level of wealth of individuals working in the same context, and assess whether and to what extent it changed over time. For instance, the average value of inventories belonging to artisans and skilled workers increased sixfold between 1850 and 1910. Even more interesting results can be found focusing on those professions that more than others relied on salaries as the only source of income, such as labourers. The sample contains a good number of individuals belonging to this category (all men), almost equally distributed throughout the period. The average wealth of their inventories increased twentyfold between 1850 and 1910, indicating a strong improvement in their standard of living. The sample of probate inventories seems therefore to partially confirm what Bengtsson and Prado (Citation2020) found in Stockholm: in absolute terms, the value of inventories of skilled professions heavily increased between 1850 and 1910. However, those who experienced a proportionally stronger increase in their wealth (and probably living conditions) were the lower classes, at least according to the sample here analysed.

There is little information on the professional careers of women, and the type of job they did. In most cases, the socio-professional status of a woman was omitted or combined with that of the householder – usually the father or husband. They were just the ‘daughter/wife/widow of’ someone else, who in turn is/was doing some kind of profession: therefore, it is not possible to know anything about what their own profession was, if they had any. This is true for most widows and wives throughout the period. In other cases, women were classified according to their social status, but usually only if they belonged to the higher or lower parts of the society (basically noble or poor).

We have information about the professional status of only a limited number of women, mostly spinsters. Some of them were employed in ‘educated’ professions, such as nurses, teachers, and also a cashier at the Uppsala Sparkasse. However, the largest group is that of maids, which includes about 1 spinster out of 5. Even though maids were not members of the middle-class, this could be an interesting case study.Footnote15 In fact, they could have indirectly enjoyed the advantage of the ‘bourgeois revolution’: as a consequence of the growth in their wages, the middle-classes started to mimic the lifestyle of the nobility. They hired maids that they could now afford, increasing the demand for this typology of workers and therefore their salary (Bengtsson & Prado, Citation2020, p. 106). Analysing the sample, it is clear that they became richer over time, given the fact that their inventories recorded more wealth, at least starting from 1870. And this is roughly what happened among men, even if the variation seems to be more limited, given that, on average, their inventories in 1910 are only 25 per cent richer than in 1850.

Between 1850 and 1910 salaries seem to have increased in Uppsala, at least according to what the sample of probate inventories suggests. Higher salaries partially explain the growth in the overall wealth recorded in the probate inventories as well as the trend we saw in and . The ‘bourgeois revolution’ had, directly or indirectly, some effects on the increase in the wealth level of spinsters. It partly clarify why the probate inventories of certain specific categories, such as maid, became richer over time. However, this does not seem to justify what happened between 1890 and 1910, especially when members of higher social strata are considered. Other, more crucial, phenomena played a much more relevant role.

4. Variations in the wealth composition over time

In the course of the paper, I have already mentioned the importance of the legal framework on women's wealth accumulation, as well as the evolution it has in nineteenth-century Sweden. Shammas (Citation1994), Jones (Citation1982) and Mcdevitt and Irwin (Citation2017) have shown that in the second half of the nineteenth century there was a dramatic narrowing of the gender wealth gap in the United States, paralleled by an increase in the number of women among probate inventory holders.

Carole Shammas (Citation1994) claims that women's wealth has varied in relation to a more systematic right of ownership in the United States of the nineteenth century. She maintains that when the law stated that women could keep the property they brought to their marriages, parents were more inclined to donate or bequeath it to their daughters, since they knew that the property would not be taken by their husbands. Shammas linked this phenomenon to the expansion of married women's property rights; Mcdevitt and Irwin (Citation2017) argue that the legal recognition of greater property rights for women was just a type of formal recognition of a process that had its origins elsewhere. Whatever the reason, the outcome was the same: in the second half of the nineteenth century, American women's probate inventories began to be more numerous and richer than ever before.

Even though in Uppsala we do not see a ‘dramatic’ narrowing of the gender wealth gap, the evolution of legal rights of women could partly explain the growth in the wealth recorded in the probate inventories of spinsters at the turn of the twentieth century. As already stated above, there have been many legal changes that were aimed at giving more rights to women. They did not suffer primarily from a lack of property rights, but rather from the possibility to manage their properties autonomously: wives and spinsters, the two categories of women most affected by this problem, owned wealth and assets, but their guardians – their husbands and fathers – had administrative authority over the assets of the whole household.Footnote16 As I have already said, the guardianship over spinsters was progressively abolished (1858–1872), the legal age was lowered (1884 for spinsters, 1921 for wives) and from 1874 married women could autonomously dispose of the income from their work (Göransson, Citation1993, p. 12). None of these interventions took place between 1890 and 1910, but it is likely that it takes time before legal changes affect actual life, especially if we are talking about wealth accumulation. To delve deeper and to better evaluate the impact that the evolution of the legal framework, this section analyses how individuals’ wealth changed qualitatively over time, focusing again on the three categories of married individuals, widows and spinsters.

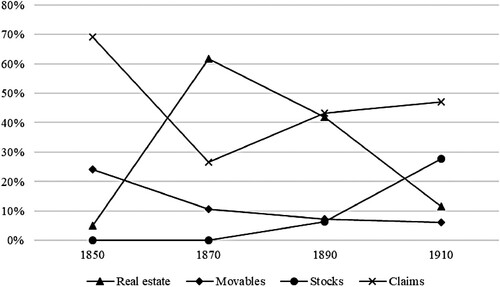

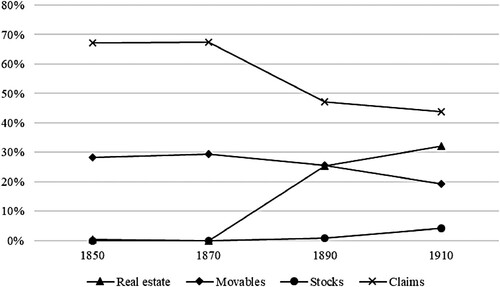

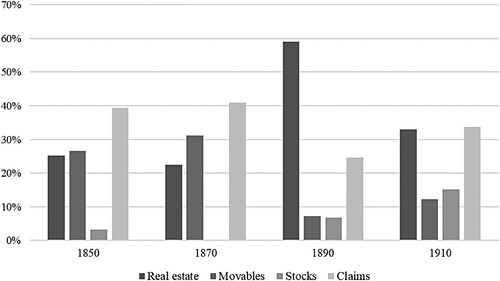

Probate inventories list separately the several different kinds of assets that contributed to creating the wealth of individuals at the time of their death. This analysis focuses more specifically on real estate, movables, claims and stocks. They prove to be the most important assets in determining individuals’ levels of wealth. Summed together they account for between 94 and 97 per cent of total wealth in all years considered (1850, 1870, 1890 and 1910).Footnote17

First of all, between 1850 and 1910 movables lose their proportional weight in the inventories: even if their absolute value increases over time, indicating that individuals own more objects (or more precious ones), it grew slower than that of other assets. Of course, this is not always true, since in the poorest inventories (gross value of less than a thousand crowns) movables constitute the majority of wealth until 1910.

Stocks are specific types of security that entitle their holders to a fraction of ownership in a company. Buying a stock ensures its holder a portion of a company's earnings, regularly distributed as dividends. Stocks are a potentially lucrative but risky investment, which reflects active and conscious participation in the credit market. As we can see in , stocks were 3 per cent of total gross wealth in 1850, 15 per cent in 1910. This is a clear sign that the so-called ‘paper’ economy started playing an increasingly important part in people's lives, and contributed to generating wealth (Green et al., Citation2011, p. 68). All categories started investing in stocks by 1890, but in markedly different ways. The share of stocks owned by spinsters is almost irrelevant in 1890 and remains very limited in 1910 (around 0.4 per cent of total gross wealth). On the other hand, married individuals and widows invested much more substantially in stocks.

Figure 3. Wealth composition in 1850, 1870, 1890 and 1910 as a % of the gross wealth (inventories of married individuals, spinsters and widows).

It is especially interesting to note that almost 28 per cent of the wealth recorded in the inventories of widows in 1910 is in stocks (4 per cent of total wealth in 1910). Of course, these could be simply shares inherited from their husbands, but this does not seem always the case. For instance, comparing the probate inventory of a widow who died in 1910 in the Swedish city of Gävle with that of her husband who died 17 years before, Pompermaier (Citation2021) has shown that the investment in stocks increased considerably in the 17 years that separate the death of the two spouses.Footnote18 It is not a coincidence that it occurs at the turn of the twentieth century, a period in which stock investments increases in all categories (see ).

Probate inventories, therefore, reflect active and conscious participation in the credit market by widows. This trend finds a partial confirmation in the literature focused on nineteenth-century England. In that period, a significant number of people became dependent on the fortunes of the stock market in the context of a process that has been called the ‘democratisation of shareholding’. Due to their exclusion from paid employment, women – especially widows and married women – relied on dividends for an income to a much greater extent than men. In the English case, it seems they were more concerned with the security of the funds and the guaranteed dividends, rather than their profitability (Rutterford & Maltby, Citation2006, p. 113). However, despite the lower risks, they often managed to get globally higher returns than men (Carlos, Maguire, & Neal, Citation2009; Laurence, Citation2009). By the end of the nineteenth century, many English women were strictly tied into the market fluctuations for their financial well-being (Green et al., Citation2011, pp. 68–69).

Claims consist of all the money that individuals had invested in both private lending (especially through promissory notes) and banking, and that they still have to recover when they died. They appear consistently as a predominant part of private wealth, averaging between one-fourth and one-third of the total value of inventories throughout the period. More specifically, the preponderance of promissory notes as a means of providing credit confirms that the peer-to-peer credit market remained the most important source of funding all through the nineteenth century (Petersson, Citation2009, p. 256).

Claims are globally the main part of the wealth of spinsters (56.33 per cent) and widows (46.53 per cent, married individuals 25.58 per cent). In absolute terms, the value of claims increases throughout the period in the inventories of unmarried women, while it decreased in those of married individuals. In particular, the amount invested in claims by spinsters between 1850 and 1910 multiplied sevenfold (although their proportional value decreased, see ). This is nothing new since it has already been highlighted by the literature. Never-married women were usually characterised by conservative behaviour on the credit market, preferring low-risk forms of investments (see Green et al., Citation2011; Green & Owens, Citation2003; Rutterford & Maltby, Citation2006). The analysis of Uppsala's probate inventories confirms this idea, since 70 per cent of claims are made up of bank deposits in savings and commercial banks, while just 30 per cent to direct lending such as promissory notes. This is true in both rich and less rich inventories, and it is therefore not the consequence of more or less money available for investment.Footnote19 Banks were considered safe and profitable places where to deposit their money.

Finally, real estate is the most relevant source of wealth in Uppsala between 1850 and 1910. Real estate was a strategic asset with a strong cultural meaning, which was linked to gender and inheritance dynamics as well as to the law of supply and demand: it was the counterweight to the ‘paper’ economy, favourite because it was ‘unaffected by financial scandals, relatively easy to understand in relation to risk and rates of return’ (Green et al., Citation2011, p. 68). This is why in nineteenth-century England real estate was preferred by shopkeepers and more broadly by the members of the middle-class. This was not the case in Uppsala, where it was for a long time almost exclusively in the hands of the richer part of the society.

Real estate value explains the trend of both the average and aggregate value of inventories (see ). In 1890 real estate alone was worth 60 per cent of the total value of the inventories (61 per cent for married individuals and 42 per cent for widows). Private wealth was strictly linked to housing prices, and, more in general, to the housing market. The drop in the aggregate and average value of inventories that happened between 1890 and 1910 was probably linked to the fall in the housing prices in 1909, highlighted in several Norwegian towns, as well in Stockholm and Gothenburg (Söderberg et al., Citation2014). Uppsala was among the ten most populous cities in Sweden in 1900, and it was very closely connected to Stockholm: probate inventories seem to confirm that the same downturn also hit its housing market.

The percentage of inventories that enlisted real estate increased between 1850 and 1890 (from 18.35–23.13 per cent) and then declined in 1910, returning to the level of 1850. There were fewer married individuals (−8 per cent) and widows (−13 per cent) who owned real properties, and their value fell considerably (by 20 per cent in the inventories of married individuals), suggesting that housing prices could have dropped in Uppsala. However, this general trend is not the same for every category. In fact, the number of spinsters owning real estate at the time of their death doubled in 1910 compared to 1890, from 5 to 10 per cent of the total. Spinsters owned 10 per cent of the total value of real estate recorded in the inventories in that year, something that has never happened before.

The owning of real estate seems therefore to be the cause of the strong increase of spinsters’ wealth in 1910 and contributed consistently to narrowing the wealth gap they had with widows and married individuals. In future, studies on the housing market in Uppsala could confirm to what extent housing prices contributed to the fall of private wealth in 1910, and shed more light on the role of spinsters as real estate owners. However, the very fact that spinsters owned real estate is interesting in itself, and it is likely to be a consequence of the introduction in the second half of the nineteenth century of an increasingly gender-equal legal framework, especially in relation to property and inheritance rights.

5. Concluding remarks

This paper has focused on the evolution of personal wealth during a key period in Swedish history when the country set off on the path that made it – almost a century later – one of the most industrialised and advanced in the world. The economic development was accompanied by a process of transformation that involved several aspects of society. The legal framework was modernised and provided a more equal, systematic right of ownership for women, especially spinsters and wives. The public authorities intervened to protect the property rights of women, regulate the inheritance practices and, above all, safeguard the possibility for unmarried and married women to manage their assets independently (guardianship, legal age, etc.). Moreover, in the second half of the nineteenth century, many women benefitted from the so-called ‘bourgeois revolution’, during which the average wage of the middle classes started to increase. This process specifically concerns the educated professions – such as teachers and nurses – but it also had important consequences on lower-rank jobs, for example, maids. All of them enjoyed higher salaries and better living conditions.

However, the dynamics linked to the housing market proved to be the most critical in defining the levels of private wealth. The average wealth of spinsters increased strongly after 1890, exactly when real estate was recorded for the first time in some of their inventories. It is not easy to explain what changed in that period, considering that at least until 1870 they were almost excluded from real estate ownership. It is probably the consequence of the more equal legal framework and perhaps a more accessible market.

The second main source of wealth for unmarried women, both spinsters and widows, was claims, especially bank accounts. As in Stockholm, the establishment of savings and commercial banks offered them a safe and profitable place to deposit their money (Petersson, Citation2009). This is confirmed by the increase of wealth deposited into banks by these two categories of women, especially between 1890 and 1910. Widows also invested in stocks, at least starting between 1870 and 1890. We do not know if it was the result of their individual choice or just an echo of something their husbands did when they were still alive. It is, at any rate, interesting to stress that something similar happened in nineteenth-century England, where widows compensated for their exclusion from the labour market by investing in the stock market. Widows seemed to have paid for the fall of housing prices in the 1900s, and the share and value of real estate reduced consistently between 1890 and 1910, affecting the average and aggregate value of their inventories. Claims and stocks contributed to partially compensate for this wealth reduction.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that married individuals – and especially men – held the majority of wealth throughout the period. However, all the phenomena we have referred to – economic development, the ‘bourgeois revolution’, and the progressive introduction of a more gender-equal legal framework – contributed to the progressive emergence of spinsters with rich inventories at the turn of the twentieth century. In future, other research on the housing market could be useful to better contextualise what the analysis of probate inventories described us. In general, it seems that the Swedish development of the late nineteenth century engendered not solely economic improvement, but also a broader redefinition of the relations between genders.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank Prof. Elise Dermineur, Prof. Gonzalo Pozo Martin, Dr Mattia Viale and all the participants at the EHFF seminarium at the Stockholm School of Economics for their invaluable comments and suggestions. He is also grateful to Robert Eckeryd and Martin Almbjär for their help in the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See, among others, Bengtsson et al., Citation2018; Bengtsson & Svensson, Citation2019; Lindberg, Citation2007; Lindgren, Citation2002.

2 Uppsala rådhusrätt och magistrat FII (48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 70, 90); Uppsala Universitetsarkiv, EIII (204, 205). The exact numeration is available upon request ([email protected]).

3 The analysis of the sample of probate inventories confirmed that married men's and women's wealth follows roughly the same pattern; it is a further confirmation that it is reasonable to consider them as a single group.

4 However, husbands could not sell or use as collateral the real estate of their wives without their consent.

5 For instance, see Fauve-Camoux, Citation1998 for the French case.

6 Even though the sample includes all the inventories regardless of the age of the decedents, the representativeness test considers only those who were more than twenty years of age when they died. In fact, the youngest decedents were only rarely economically independent, and there was no need to draw up an inventory (Lindgren, Citation2002, pp. 821–822): this explains why, if we consider just the younger decedents, representativity falls to around 2–3 per cent of the total.

7 However, an examination of professional status proves that many spinsters belonged to the middle and lower strata of the society, suggesting a varied social composition of the sample (see section 3).

8 Values are always corrected for inflation using the CPI available in Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2010, p. 1914 = 100%

9 However, there are few studies on the evolution of land prices, especially in the nineteenth century; for instance, Edvinsson and Söderberg retraced land prices in east Sweden between 1294 and 1651; see Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2010, pp. 440–442.

10 For instance, the net value of the richer inventory was 115 times higher than the average.

11 See the Canadian case in Di Matteo, Citation2008.

12 All values in crowns have been corrected for inflation using the consumer price index available in Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2010, p. 443.

13 As a double-check, I analysed a sample of 129 inventories drawn up in 1891, and I found that the overall value of the real estate was even higher than in 1890.

14 For every 100 wives, there were 81 spinsters and 27 widows; for every 1,000 men there were 3,660 women (1901); see Rutterford & Maltby, Citation2006, p. 118.

15 As I already said, medium and lower strata are under-represented but not completely missing.

16 They got limits of course: for instance, husbands could not sell or use the land as collateral without the authorisation of the wife; see Ågren, Citation2009, pp. 71–84.

17 Cash has been excluded because, even if it is listed in more than 50 per cent of inventories, its incidence on the overall value is quite limited.

18 It is not clear the role of the sons and the daughters of the couple in the management of family assets, however when the husband died ‘there has been a change toward a more “aggressive” management characterised by a strong indebtedness and investment in more diversified sectors’ (Pompermaier, Citation2021, p. 21).

19 The same proportion between bank accounts and promissory notes can be found in the first quintile as in the last quintile of the sample.

Bibliography

- Ågren, M. (2009). Domestic secrets: Women and property in Sweden, 1600-1857. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bellavitis, A. (2018). Il lavoro delle donne nelle città dell’Europa moderna. Rome: Viella.

- Bengtsson, E., Missaia, A., Olsson, M., & Svensson, P. (2018). Wealth inequality in Sweden, 17501900. Economic History Review, 71(3), 772–794.

- Bengtsson, E., & Prado, S. (2020). The rise of the middle class: The income gap between salaried employees and workers in Sweden, ca. 1830–1940. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 68(2), 91–111.

- Bengtsson, E., & Svensson, P. (2019). The wealth of the Swedish peasant farmer class (1750–1900): Composition and distribution. Rural History, 30, 129–145.

- Bennett, J. M., & Froide, A. M. (1999). A singular past. In J. M. Bennett, & A. M. Froide (Eds.), Singlewomen in the European past. 1250-1800 (pp. 1–36). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Berg, M. (1993). Women’s property and the industrial revolution. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 24(2), 233–250.

- Carlos, A. M., Maguire, K., & Neal, L. (2009). Women in the city: Financial acumen during the south Sea bubble. In A. Laurence, J. Maltby, & J. Rutterford (Eds.), Women and their money 1700–1950. Essays on women and finance (pp. 33–46). London and New York: Routledge.

- Denton, M., & Boos, L. (2007). The gender wealth gap: Structural and material constraints and implications for later life. Journal of Women & Aging, 19(3-4), 105–120.

- Dermineur, E. (2014). Single women and the rural credit market in eighteenth century France. Journal of Social History, 48(1), 1–25.

- Di Matteo, L. (2008). Wealth accumulation motives: Evidence from the probate records of Ontario, 1892 and 1902. Cliometrica, 2, 143–171.

- Dribe, M., & Lundh, C. (2005). Gender aspects of inheritance strategies and land transmission in rural Scania, Sweden, 1720–1840. The History of the Family, 10(3), 293–308.

- Edvinsson, R., & Söderberg, J. (2010). The evolution of Swedish consumer prices 1290–2008. In R. Edvinsson, T. Jacobsson, & D. Waldenström (Eds.), Exchange rates, prices, and wages, 1277-2008 (pp. 412–452). Stockholm: Ekerlids Förlag & Sveriges Riksbank.

- Fauve-Camoux, A. (1998). Vedove di città e vedove di campagna nella francia preindustriale: Aggregato domestico, trasmissione e strategie familiari di sopravvivenza. Quaderni Storici, 33(2), 301–332.

- Göransson, A. (1993). Gender and property rights: Capital, kin, and owner influence in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Sweden. Business History, 35(2), 11–32.

- Green, D. R., & Owens, A. (2003). Gentlewomanly capitalism? Spinsters, widows, and wealth holding in England and Wales, c. 1800-1860. The Economic History Review, 56(3), 510–536.

- Green, D. R., Owens, A., Swan, C., & van Lieshout, C. (2011). Assets of the dead: Wealth, investment, and modernity in nineteenth – and early twentieth-century England and Wales. In D. R. Green, A. Owens, J. Maltby, & J. Rutterford (Eds.), Men, women and money. Perspectives on gender, wealth and investment, 1850-1930 (pp. 54–81). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holmlund, S. (2008). From formal to female property rights: Gender and inheritance of landed property in Estuna, Sweden, 1810-1845. In I. A. Morell, & B. B. Bock (Eds.), Gender regimes, citizen participation and rural restructuring (pp. 239–260). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Isacson, M. (1979). Ekonomisk tillvävt och social differentiering 1680-1860. Bondeklassen i By socken, kopparbergs län. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Jones, A. H. (1982). Estimating wealth of the living from a probate sample. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 13(2), 273–300.

- Keibek, S. A. J. (2017). Correcting the Probate Inventory Record for Wealth Bias. Working Paper No. 28, March 2017, Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure & Queens’ College.

- Kleven, H. (2022). The Geography of Child Penalties and Gender Norms: Evidence from the United States. Working Paper, April 2022, Princeton University and NBER, https://www.henrikkleven.com/uploads/3/7/3/1/37310663/childpenalties-culture_kleven_april2022.pdf (05.19.2022)

- Kuuse, J. (1974). The probate inventory as a source for economic and social history. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 22(1), 22–31.

- Laurence, A. (2009). Women and finance in eighteenth-century England. In A. Laurence, J. Maltby, & J. Rutterford (Eds.), Women and their money 1700–1950. Essays on women and finance (pp. 30–33). London and New York: Routledge.

- Laurence, A., Maltby, J., & Rutterford, J. (2009). Women and their money 1700–1950. Essays on women and finance. London and New York: Routledge.

- Licini, S. (2011). Assessing female wealth in nineteenth century Milan, Italy. Accounting History, 16(1), 35–54.

- Lindberg, E. (2007). Mercantilism and urban inequalities in eighteenth-century Sweden. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 55(1), 1–19.

- Lindgren, H. (2002). The modernization of Swedish credit market, 1840–1905: Evidence from probate records. The Journal of Economic History, 62(3), 810–832.

- Magnusson, L. (2000). An economic history of Sweden. London: Routledge.

- Markkanen, E. (1978). The use of probate inventories as indicators of personal wealth during the period of industrialization: The financial resources of the finnish rural population 1850–1911. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 26(1), 66–83.

- McCants, A. (2002). Petty debts and Family networks: The credit markets of widows and wives in eighteenth-century Amsterdam. In B. Lemire, R. Pearson, & G. Campbell (Eds.), Women and credit. Researching the past, refiguring the future (pp. 51–71). Oxford and New York: Berg.

- McCants, A. (2006). After-death inventories as a source for the study of material culture, economic well-being, and household formation among the poor of eighteenth-century Amsterdam. Historical Methods, 39(1), 10–23.

- McCants, A. (2007). Goods at pawn: The overlapping worlds of material possessions and family finance in early modern Amsterdam. Social Science History, 31(2), 213–238.

- Mcdevitt, L., & Irwin, J. R. (2017). The narrowing of the gender wealth gap across the nineteenth-century United States. Social Science History, 41, 255–281.

- Moring, B. (2007). The standard of living of widows: Inventories as an indicator of the economic situation of widows. History of the Family, 12, 233–249.

- Murhem, S., Karlssom, L., Nilsson, R., & Ulväng, G. (2019). Undervaluation in probate inventories probate inventory values and auction protocol market prices in eighteenth and nineteenth century Sweden. History of Retailing and Consumption, 5(2), 87–110.

- Ögren, A. (2009). Financial revolution and economic modernisation in Sweden. Financial History Review, 16(1), 47–71.

- Ögren, A. (2010). The Swedish financial revolution. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Petersson, T. (2009). Women, money and the financial revolution: A gender perspective on the development of the Swedish financial system, c.1860–1920. In A. Laurence, J. Maltby, & J. Rutterford (Eds.), Women and their money 1700–1950. Essays on women and finance (pp. 254–270). London and New York: Routledge.

- Petti Balbi, G., & Guglielmotti, P. (2010). Dare credito alle donne. Presenze femminili nell’economia tra medioevo ed età moderna. Proceedings of the international conference in asti, 8-9 October 2010, centro studi renato bordone sui lombardi, sul credito e sulla banca.

- Pompermaier, M. (2021). A complicated puzzle: Spinsters, widows, and credit in Sweden (1790-1910). Financial History Review, 29(1), 1–23.

- Rothstein, B. (2012). The reproduction of gender inequality in Sweden: A causal mechanism approach. Gender, Work and Organization, 19(3), 324–344.

- Ruel, E., & Hauser, R. M. (2013). Explaining the gender wealth gap. Demography, 50(4), 1155–1176.

- Rutterford, J., & Maltby, J. (2006). ‘The widow, the clergyman and the reckless’: Women investors in England, 1830-1914. Feminist Economics, 12(1-2), 111–138.

- Sandberg, L. G. (1978). Banking and economic growth in Sweden before World War I. Journal of Economic History, 38(3), 650–680.

- Sandberg, L. G. (1979). The case of the impoverished sophisticate: Human capital and Swedish economic growth before World War I. The Journal of Economic History, 39(1), 225–241.

- Shammas, C. (1990). The pre-industrial consumer in England and America. New York: Clarendon Press.

- Shammas, C. (1994). Re-assessing the married women’s property acts. Journal of Women’s History, 6(1), 9–30.

- Söderberg, J., Blöndal, S., & Edvinsson, E. (2014). A price index for residential property in Stockholm, 1875–2012. In R. Edvinsson, T. Jacobson, & D. Waldenström (Eds.), House prices, stock returns, national accounts, and the riksbank balance sheet, 1620–2012 (pp. 63–101). Stockholm: Ekerlids Förlag & Sveriges Riksbank.

- Spicksley, J. M. (2018). Never-Married Women and Credit in early modern England. In E. Dermineur (Ed.), Women and credit in pre-industrial Europe (pp. 227–252). Turnhout: Brepols Publisher.

- Statisticka Centralbyrån. (1969). Historisk statistik för Sverige (1720-1967), del 1: Befolkning, KL beckmans tryckerier AB, Stockholm top? Financial Management, 86, 1–28.

- Walndenström, D. (2017). Wealth-income rations in a small developing economy: Sweden 1810–2014. The Journal of Economic History, 77(1), 285–313.

- Warren, T., Rowlingson, K., & Whyley, C. (2001). Female finances: Gender wage gaps and gender asset gaps. Work, Employment & Society, 15(3), 465–488.

- Weatherill, L. (1988). Consumer behaviour and material culture in Britain, 1600-1750. London: Routledge.