ABSTRACT

Youth labour remained important well into the twentieth century, although it is often elusive in traditional sources. In this article, we investigate messengers – a category of occupational titles, including errand and office boys, which is thought of as youth jobs. We sketch the long-term development of the occupation by making use of digitised Swedish daily newspapers and discuss demand-side, supply-side and institutional factors for the disappearance of the occupation. Our investigation suggests that the messenger jobs reached their peak around 1945 and thereafter decreased to low levels in the 1960s. We find that employers looking for messengers were large organisations that needed in-house help with deliveries and simple office tasks. These employers originally aimed at young men aged 15–17 years. The minimum age requirement was not loosened over time; instead, employers began to announce for older workers. We interpret this as employers’ adapting to a situation where the supply of young messengers had decreased. Employers made their ads appealing by emphasising good working conditions and career prospects, indicating that there was still a demand for messengers despite the changing times.

1. Introduction

The nature and decline of child labour in the wake of industrialisation are major themes in economic and social history (see e.g. Humphries, Citation2010; Olsson, Citation1980; Rahikainen, Citation2017). It is easily forgotten that youth labour continued. At least until the 1960s, most teenagers were in the labour force. Families needed their supplementary incomes and secondary schooling was available for tiny proportions of each cohort. In urban settings, some young men and women were drawn into new manufacturing industries (Heim, Citation1984; Scott, Citation2000) and there were plenty of jobs in the service sector that were appropriate – or even designed – for young people, as pointed out by Schrumpf (Citation1997). Among these were domestic servants, but also the messenger jobs, which this article covers.

Messenger jobs, criticised by some contemporary debaters and later idealised (see e.g. Håkansson & Karlsson, Citation2018), employed both boys and girls and were common. An investigation by the Swedish labour market authorities in 1946 found over 25,000 messengers employed in the commodity trade alone (Kommittén för yrkesutbildning åt varubud m. fl., Citation1949). This was equivalent to 6% of all employed in the sector and almost 6% of all people in the age group 15–20 years. Since these jobs were temporary, many more boys and girls had experienced, or would experience, work as a messenger, as is obvious when reading life histories of people who came of age in the early and mid-twentieth century (Håkansson & Karlsson, Citation2018).

Compared to the literature on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century child labour, the literature on twentieth-century youth labour dwindles. There are some studies on youth culture and lifestyles in the inter-war period (Todd, Citation2006), as well as on the debate over dead-end jobs for young people (Cooper, Citation2021; Fowler, Citation2014; Schröder, Citation1991). There is very little on the following period, when we believe that frequency of messenger jobs peaked and then began to fade away. Downey’s (Citation2002) account of American telegraph messengers, whose collective action pushed up their wages and induced employers to replace them, is a rare exception. This account is also exceptional in the sense that the high turnover of workers in messenger jobs typically has made unionisation difficult. Messengers have, therefore, not left many traces in union records. Published sources, such as censuses, have typically too broad categories to allow studies of specific occupational groups.

In this article, we use newspapers job ads to investigate the heydays and subsequent disappearance of messengers in Sweden. We study how frequently the relevant occupational titles appeared as well as the job content, qualifications, age preferences, gender, terms of employment and the types of firms that looked for messengers. We relate our findings to previous research on changes in retail trade, office work, education, and wage determination to discuss how to explain why messenger jobs disappeared from the pages of newspapers, and the labour market. Although newspaper job ads most directly reflect the demand for labour, we argue that they may also, indirectly, reflect changes in the supply of labour. The messenger jobs may finally have become redundant because of technological and organisational changes, but when studying the content of the job ads, we can notice that employers made efforts to make their job offers appealing by adding offers of what today would be called ‘fringe benefits’. Therefore, we conclude that messengers were still demanded.

Aware of the methodological challenges of using job ads for our purpose, we make systematic searches of relevant occupational titles in an interface of digitised Swedish newspapers. We look closer at the period 1960–1970, which we see as the decisive decade for the decline of the messenger jobs, and extract information manually from the two newspapers, Dagens Nyheter (hereafter DN) and Svenska Dagbladet (hereafter SvD). The resulting database that we study in the article consists of almost 500 job ads. In addition to the terms of employment, the job ads contain information about the firms that looked for messengers as well as the desired characteristics of the applicants. Our investigation concerns the Swedish labour market, or more precisely, the capital Stockholm. The timing and magnitude of the changes may differ for other locations.

In addition to the contributions to the historical literature on youth labour and the use of digital newspapers more generally, our findings add new perspectives to current debates on youth jobs and the gig economy. In the ongoing political debate in Sweden and elsewhere, some voices advocate the creation of low-skilled youth jobs. They usually assume that these jobs have been lost because of too high wages for young people. Although the current state of research does not allow disregarding such an explanation, we remind that forces of demand and supply were more likely to have crowded out the unskilled youth jobs of the past. Other voices in the debate regard the bike couriers and delivery services in modern cities as an unwelcome return of precarious work practices. In this regard, our study reminds us that although the tasks and occupational titles are similar, the terms of employment differed considerably between the errand or office boy of the mid-twentieth century and the courier of the twenty-first century. The historical roots of the gig economy have to be sought elsewhere.

In the following section, we discuss our methodological approach in greater detail. Thereafter, we present the empirical findings; firstly, by studying the frequency of messenger-job titles in the long run and secondly, by manually studying the content of job ads from the period 1960–1970. We reconcile and integrate our findings with previous research to discuss three types of explanations for the disappearance of messenger jobs: demand, supply, and institutional factors. The final section concludes and suggests directions for further research.

2. Reviewing the method: using job ads to study the demand for an occupation

There is an increasing interest in the use of job ads to capture various aspects of labour demand. The online publication of ads lowers the costs of collecting and coding huge datasets, which not only gives an indication of the volume of labour demand but also its qualitative content and the type of language used by employers when looking for applicants. There are, for example, studies on discrimination by gender and age (Burn, Button, Munguia Corrella, & Neumark, Citation2019; Kuhn & Shen, Citation2013), as well as studies on skill requirements (Deming & Kahn, Citation2018; Ziegler, Citation2020), based on job ads. The digitisation of historical newspapers creates similar research opportunities. Alves and Roberts (Citation2012) investigate ads in the Los Angeles Times for men and women during the Second World War, with the background of a government-sponsored campaign to increase female labour force participation. Schulz, Maas, and Van Leeuwen (Citation2014) try to capture the process of modernisation and development into a more open society by investigating the importance of non-job-related and job-related characteristics, respectively, in employers’ ads in a sample of Dutch newspapers for the period between 1870 and 1940. However, our article deviates from Alves and Roberts (Citation2012) and Schulz et al. (Citation2014) in that we are studying the demand for a defined occupation.

A particular methodological challenge when using job ads to study historical labour markets, in general, is the uncertainty of how the matching of employers and workers took place and to what extent newspapers played a role in this process. Systematic inquiries into a job search and recruitment patterns began in the 1920s and typically emphasised the reliance on word-of-mouth and networks (Rosenbloom, Citation1994). Yet, employment agencies and newspapers were already important channels for office workers before 1950 (Licht, Citation2000). Newspaper ads also covered a wide spectrum of occupations. Except for an underrepresentation of jobs in agriculture and an overrepresentation of domestic servants, Schulz et al. (Citation2014) find a remarkable correspondence between the most common occupational titles mentioned in Dutch population registers 1870–1922 and newspapers. Most likely, newspapers were used more frequently in times of labour shortage. In addition, Alves and Roberts (Citation2012) estimate that they have captured one-third of all new job openings in Los Angeles in the 1940s by looking at two weekdays in one newspaper. The idea that job ads in newspapers were important in twentieth-century Sweden, and particularly in the decades after the Second World War, has been confirmed by oral-history research (Tovatt, Citation2013).

In this article, we assume a positive relationship between the frequency of ads and the demand for messengers. Therefore, more ads indicate an increased demand, and fewer ads show a decreased demand. However, there are at least three potential problems with our assumption. Firstly, there is a possibility that changes in the frequency rather reflect changes in the recruitment channels. Such changes may be long-term; however, based on previous research, we have a quite good idea of the directions of such changes. When it comes to long-term trends in recruitment, there was growing importance in formal channels (ads in newspapers and employment agencies) in the mid-twentieth century (Håkansson & Tovatt, Citation2017). There may of course also be shifts between the importance formal channels, that is between newspapers and employment agencies. To make sure that this does not distort our findings, we have made spot checks of the national vacancy list.Footnote1 Also, as shown below, we examined the structural development of the newspaper that we use as sources, and identified that the job ad section and the ad types remained stable enough for a long-term study even up until the 1980s.

Secondly, changes in the frequency of job ads for a particular occupation may reflect labour demand more generally and not necessarily the demand for the occupations that are our primary concern in this article. We deal with this problem by including a reference category (janitors) when studying long-term trends. Thirdly, employers typically look for workers because they have certain tasks that need to be carried out, and these tasks may well be performed by more than one occupation. Employers may substitute between occupations even though their basic demand remains the same. In this article, we pay particular attention to ads looking for elderly messengers, the so called ‘grey lads’ (grågosse). Moreover, when preparing for this study, we went through the various occupational titles associated with the same HISCO classification designating messenger jobs.Footnote2

Demand is not only reflected in the number of ads but also in their content. Given that advertisers paid according to the size of their ads, we assume a positive relationship between labour demand and the amount of information in the ads. In times of excess demand, job ads would increase in size and include more details about the job, such as the wage rate. As suggested by Alves and Roberts (Citation2012), high demand may also be reflected by ‘inducements’, appealing characteristics of the job in addition to the pay, such as fringe benefits, training and career opportunities. In times of slack demand, we expect job ads to become smaller and less informative. Moreover, labour demand may be indicated by the composition of information. In times of high demand, the ads would include more information about the job and fewer requirements for the applicant. A caveat when studying the content of job ads to draw conclusions about labour demand is that the size (amount of information) may be influenced by the advertisers’ ability to pay. Therefore, large firms would be able to buy more advertisement space.

There are additional methodological challenges to using job ads to study the demand for an occupation through digitised newspapers. Some of these challenges are general to digital history and text mining, while others are related to changes in the volume and content of Swedish newspapers and to the features of the search interface and database we have used, namely, Svenska dagstidningar, maintained by the National Library of Sweden (Kungliga biblioteket).Footnote3 The user interface of Svenska dagstidningar allows for keyword searches and the use of filters (publication, year) in the newspapers that have been digitised and included in the database. The material published after 1906 is under copyright and can be accessed only at separate user terminals at libraries. The challenge with the database is that it is not possible to download the search results or the newspaper data after 1906, and therefore not to extract the ads with automated methods (cf. Ros, Van Erp, Rijpma, & Zijdeman, Citation2020). In addition, there is currently no metadata about the newspaper content, which would help to search for advertisements only.

In this setting, we employ a semi-automatic method of digital textual analysis (Fridlund, Citation2020; Fridlund & La Mela, Citation2019). This means that we make use of the potential of the search interface for studying the long-term changes and finding the relevant articles and then extract manually information from the advertisements for our dataset. We used natural language processing tools to highlight the most common terms and expressions in the collected dataset. In addition, we examined our text extraction results manually to pinpoint the information relevant to our study. Moreover, we refined our text mining method iteratively (Guldi, Citation2018) when we learned about the structure and the quality of our digital source material. The methodological challenges will be addressed more in detail in the following two sections, which deal with long-term trends and the period 1960–1970.

3. The long-run evidence, 1910–1980

The coverage of the database Svenska dagstidningar depends on the time period and is continuously changing, as additional newspapers and years are added (Karlsson, Citation2019). We have, therefore, initially delimited our investigations to DN and SvD. Over the course of the twentieth century, the volume of texts produced by these two newspapers, as well as Swedish newspapers in general, increased substantially. In 1910, an issue of DN, one of the leading daily newspapers in Sweden, had around 12 pages.Footnote4 In 1970, the equivalent number of pages had increased to 58.

In , we show the yearly relative search hit frequencies for selected messenger occupation titles and the reference occupation janitor/caretaker (vaktmästare) in the two newspapers. In this first enquiry, the interest is to understand to what extent the job titles appear in the newspapers in general, which provides an indication of the public visibility and presence of the messengers. We see an increase in the presence of the messenger titles until the early 1940s, which is followed by two decades of slight decline, and then in the 1960s, an almost complete disappearance of these occupational titles in the newspapers.Footnote5

Figure 1. Yearly search hits per total newspaper pages for messenger job titles and janitor/caretaker [vaktmästare] in DN and SvD, 1910–1980. Source: National Library of Sweden newspaper service, https://tidningar.kb.se/. Note: The search hits are newspaper pages with at least one keyword found on the page.

![Figure 1. Yearly search hits per total newspaper pages for messenger job titles and janitor/caretaker [vaktmästare] in DN and SvD, 1910–1980. Source: National Library of Sweden newspaper service, https://tidningar.kb.se/. Note: The search hits are newspaper pages with at least one keyword found on the page.](/cms/asset/31b71bae-e6ac-4e7c-bf81-cb00019bce3b/sehr_a_2106300_f0001_oc.jpg)

There are interesting differences in how the messenger job categories appear in the newspapers, which signals not only a shift in the vocabulary but also in the characteristics of the messenger jobs. The more traditional occupational titles of ‘errand boy’, ‘errand girl’, and ‘errand lad’ (springpojk*, springflick*, springgoss*) decrease first.Footnote6 Inside this category, both errand boy and girl still appear regularly in the 1940s, but after 1950, we find mainly articles with the term errand boy. Since the 1930s, the ‘errand’ category was complemented with more specific and gender-neutral titles for messenger occupations: courier (varubud), bicycle or moped courier (cykelbud, mopedbud)¸and since the 1940s, the office boy (kontorsbud). The title for the elderly male messengers, ‘grey lads’ (grågosse), is the last to appear and continues until the mid-1960s. For our reference category janitor/caretaker, the trend in the search hits is rather stable until 1980. This suggests that the downward trend in the visibility of the messenger job titles is not only due to fewer job ads in newspapers more generally.

The long-term investigation of occupational titles is only a first step. In order to assess in more detail whether the pattern shown in represents an actual decline in the demand for messenger occupations, we need to look closer at the hits as well as the overall use of job advertisements in the newspapers. We focused on the 1960s, which saw the final decline of the messenger job categories in the newspapers.

4. The short-run evidence, 1960–1970

In its current version, the search interface of Svenska dagstidningar does not allow to automatically distinguish between hits referring to editorial texts, job ads and other kinds of features. Thus, we have manually recorded and inspected each hit on the three most frequently found search terms – ‘springpojk*’, ‘kontorsbud’, and ‘grågoss*’ – in DN and SvD for the month of October in the years 1960–1970,Footnote7which we have identified as the decade of decline of messenger jobs. By systematically retrieving and classifying information on each hit, we have created a database with information on the type of text (editorial or job ad) and the type of ad (individual looking for job or employer looking for worker). For ads initiated by employers to find workers, the great bulk of our observations, we have recorded information on the desired characteristics of the worker (age, sex, education), name and location of firm, job content and employment conditions.

As shown in , we found 566 articles with the keyword search. When examining our results, we noted, however, that the articles were disproportionally divided between the keywords and the two newspapers. The keyword ‘office boy’ (kontorsbud) captured the most hits, and almost all the articles found with the keyword were job advertisements. The results were similar with the keyword ‘grey lad’ (grågoss*). The actual term for errand boys was less frequent in our search results, and less than half of these regarded job advertisements. The articles included biographical texts where the earlier careers were described and pieces of news, for example, about small crimes, where errand boys were mentioned. The term also appeared in the figurative expression of acting as an errand boy. Moreover, we discovered significant differences in how the jobs were advertised in the newspapers. Even though SvD had a section for job ads, we found that it was narrower and less regularly published than in DN and did not contain many ads concerning our categories. For instance, almost all articles about errand boys in SvD regarded other matters than job advertisements.

Table 1. All articles collected from Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet during the Octobers of 1960–1970.

Based on these results, we decided to delimit our research focus to DN. We investigated manually the format of the job advertisement section of DN and saw that the section was stable in its structure and was rich with job ads even up until the 1980s.Footnote8 Moreover, as indicated in , the search terms captured the job advertisements well. Most of the articles that were not job ads concerned errand boys (springpojke). Instead, it was used in news articles and stories about past careers. Furthermore, we see that most of the job ads were by employers. Job requests by employees appeared only in the grey lad category.

illustrates the drop in messenger job ads in the 1960s. In the months of October between 1960 and 1963, 265 messenger job ads by employers were published in DN. At the end of the decade, in the Octobers of 1968–1970, we find only 55 messenger job ads in the same newspaper. shows also how the gender of the applicant became less explicitly expressed in the ads (for the neutral job title kontorsbud). We find a handful of job ads, where both male and female office workers were sought.Footnote9 In general, however, the ads show that being a messenger in this period was mainly thought of as a male occupation.

Table 2. Job advertisements in Dagens Nyheter for months of October in 1960–1970.

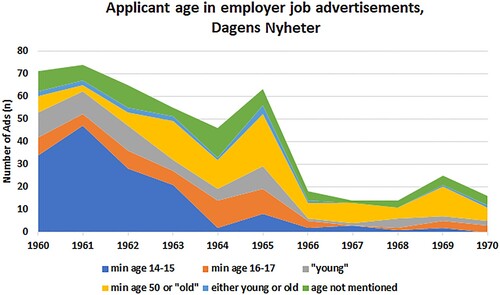

shows also how the grey lad category grows in relevance in the 1960s. This shift towards recruiting older cohorts is also visible when we study the applicant ages that were requested in the job ads. groups the applications by the age requested in the employer job ads. The figure illustrates that at the beginning of the 1960s, employers were mainly looking for messengers who were 14 or 15 years old. This minimum age rose at the same time as the decrease in the number of job ads. In the mid-1960s, the largest group requested were older applicants over the age of 50 or retired, and among the youngest, the group 14–15 years old decreased, and the group 16–17 years old increased.

Figure 2. Applicant age in employer job advertisements. Source: National Library of Sweden newspaper service, https://tidningar.kb.se/. Notes: The ‘min. age 14–15’ category shows how the requested age range started at 14 or 15. The ‘young’ category includes ads where a number was not given, but a ‘young person’ (yngling) was requested in the text. The category of ‘either young or old’ signifies the ads where either a young person (18 or younger or ‘young’ in the text) or old person (over 50 or ‘old’ in the text) was requested.

As mentioned, most of the hits referred to job ads, and most of these ads referred to employers looking for workers. We have not made a detailed classification of the employers, but some patterns are obvious. First, the firms looking for workers in DN are typically relatively big workplaces, often described as head offices of larger organisations. Some examples of employers that appear frequently in our database are AB Svenska Shell, Skånska Cementgjuteriet, Åhlén & Åkerlunds Förlags AB, and Svenska Tobaksaktiebolaget. However, the employers were not necessarily private businesses, as we found several examples of organisations in the public sector (Stockholms stads gatukontor and Televerket) and various interest organisations (Sveriges Lantbruksförbund and Stockholms Byggmästareförening). Second, the addresses of the employers reveal that they were typically located in central Stockholm. Sometimes, the add would simply state ‘central location’, suggesting that this was thought of as appealing to potential applicants. Moreover, while banks and printing houses appear frequently, some types of firms are surprisingly rare in our database, namely, retail trade businesses and delivery firms.

Regarding the lack of delivery firms in the job ads, we should mention that such firms did exist, at least for errand boys. An example is Gossexpressen, a delivery firm established in 1914 with branches in various cities that later merged with Expressbolaget (Henningsson & Henningsson, Citation1984). We also find individual examples of delivery firms among the ads, but in relation to the total number of ads, delivery firms are rare. Instead, the advertisers are organisations who want an in-house solution for the various services offered by messengers.

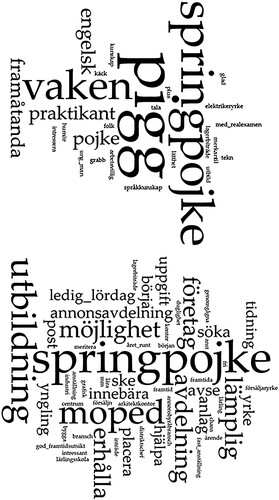

Finally, we examined what kind of applicants the employers were looking for and what kind of jobs they offered by studying frequencies and visualising them with word clouds. The word clouds highlight key features of the employers’ job ads and guided and framed our closer study of the ads. The information was collected manually from the job advertisements as written in the ads. We processed these ‘applicant characteristics’ and ‘job descriptions’ by lemmatising the words, removing stop words (common words with little semantic value such as prepositions, conjunctions, and auxiliary verbs) and organising the lemmas according to their frequency (see Appendices 2 and 3, supplementary material). We also examined the collocation of the terms and combined the terms that formed fixed expressions in the job ads, such as ‘free Saturdays’ (‘ledig_lördag’) or ‘good school grades’ (‘goda/gott_skolbetyg’). The results are visualised as word clouds in , where the size of the terms represents their relative frequency. The word clouds are not relative in size to each other, as there are different numbers of ads for the three search terms.

shows the most common words concerning the employee characteristics and the job description for the search term ‘errand boy’ (springpojke). We see that the employers used attributes related to the person of the applicant. They were looking for spirited and alert (pigg, vaken) errand boys with a forward-looking attitude (framåtanda). We find some references to educational qualities (e.g. language knowledge). Furthermore, in the job descriptions, the most common words were ‘moped’ and ‘education’ (utbildning). The ‘moped’ appears in the ads as a requested skill, but also a tool offered by the employer or something that the applicant should have. Regarding ‘education’, in some cases, the employers offered possibilities for further education within the company. As mentioned, we find evidence that the actual tasks were not related to the retail trade but rather to office work: mail (post), announcements (annonsavdelning, annonsbyråbranschen) or architect office (arkitektbyrå) all appear in the job ads.

Figure 3. The most common words describing the applicant qualities (above) and the job offered (below) in advertisements for ‘errand boy’ (‘springpojke’). Source: Appendices 2 and 3 (see supplementary material). Note: The size of the words reflects their relative frequency. The content has been selected manually from the advertisements. The most frequent words for the applicant qualities (n = 44) are spirited, 8 (pigg); errand boy, 5 (springpojke); alert, 4 (vaken); English, 2 (engelsk); forward thinking, 2 (framåtanda); boy, 2 (pojke); and trainee, 2 (praktikant). The most frequent words describing the job (n = 118) are errand boy, 7 (springpojke); education, 5 (utbildning); moped, 4 (moped); section, 4 (avdelning); obtain, 3 (erhålla); and company, 4 (företag).

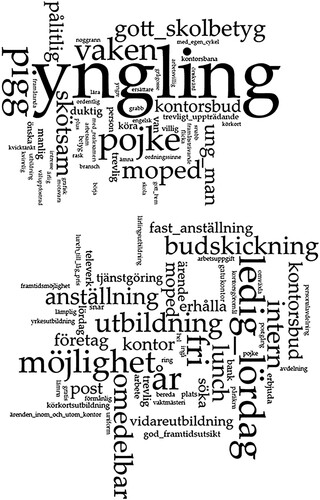

When we look at office boy (kontorsbud) ads () and how the applicant and the job were described, we find that the employers had requests about education and that they emphasised many benefits in the application. Like the errand boys above, the employers asked for a spirited and alert (pigg, vaken) attitude from the employees. In these ads, however, we also find requests about good school grades (gott/goda_skolbetyg) and that the employee should be reliable (pålitlig) and well-behaved (skötsam). The jobs that were offered regarding office tasks included words such as office (kontor), messenger tasks (budskickning), office matters (kontorsgöromål), and mail (post). Moreover, among the most common expressions appeared free Saturdays (ledig(a)_lördag(ar)) and free or decent priced lunch (lunch), as the employers offered these benefits for their employees. Finally, we find that some employers emphasised future possibilities (framtidsutsikter) and a chance at or support for further education (vidareutvildning, yrkesutbildning) that the company and the sector could offer. For example, the Stockholm Building Contractor Association (Stockholms Byggmästareförening) was looking for an office boy ‘aged 15–17 years with a sense of order and good school grades. Moreover, the ad suggested that those successful in their work could be offered further employment in the Association or education in the building sector (Dagens Nyheter, 14 October 1963, p. 43). Overall, the frequently used term, possibility (möjlighet), often indicates employer inducements, similar to that observed by Alves and Roberts (Citation2012).

Figure 4. The most common words describing the applicant qualities (above) and the job offered (below) in advertisements for office boy (kontorsbud). Source: Appendices 2 and 3 (see supplementary material). Note: The size of the words reflects their relative frequency. The content has been selected manually from the advertisements. The most frequent words for the applicant qualities (n = 536) are young man, 111 (yngling); spirited, 32 (pigg); boy, 30 (pojke); alert, 25 (vaken); good school grades, 18 (gott/goda_skolbetyg); and moped, 18 (moped). The most frequent words describing the job (n = 1777) are free, 55 (fri), free Saturday(s), 52 (ledig_lördag); year, 50 (år), possibility, 44 (möjlighet); and education, 35 (utbildning).

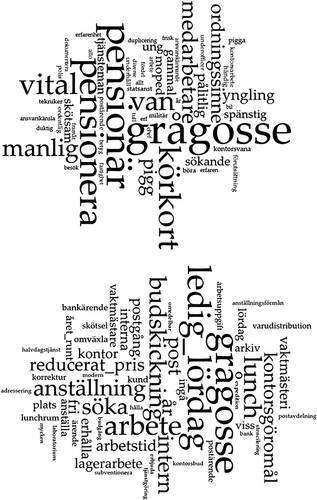

Finally, in the advertisements where a grey lad (grågosse) was requested (), we see differences related to the employee age group. The common words are pensioner (pensionär, pensionerad), male (manlig), and the requested qualities are vital and experienced (vital, van). Also, instead of a moped, the employers wrote that a driving licence (körkort) would be useful for the task. The context of offices is present, but the jobs encompass more than mere messenger or office tasks: the frequent descriptive words include messenger tasks (budskickning), office matters (kontorsgöromål), mail (post, postärenden), bank matters (bank, bankärenden), but we also find warehouse work (lagerarbete) and janitor/caretaker (vaktmästare). For example, the engineering office Allmänna Ingeniörsbyrån AB advertised for a grey lad, ‘a male worker, preferably retired’ to work in ‘internal posting, archives, and [in] assistance to the caretakers’ (Dagens Nyheter, 29.10.1969, 55). Moreover, in contrast to the errand boy and office boy, adjectives light and simple (lätt, enkel) were used to describe the tasks. The employers also offered the grey lads stable working hours, with Saturdays off and lunch benefits.

Figure 5. The most common words describing the applicant qualities (above) and the job offered (below) in advertisements for a ‘grey lad’ (grågosse). Source: Appendices 2 and 3 (see supplementary material). Note: The size of the words reflects their relative frequency. The content has been selected manually from the advertisements. The most frequent words for the applicant qualities (n = 215) are grey lad, 17 (grågosse); pensioner, 14 (pensionär); retire, 12 (pensionera); driving licence, 11 (körkort); vital, 11 (vital); experienced, 8 (van); and male, 7 (manlig). The most frequent words describing the job (n = 638) are grey lad, 21 (grågosse); free saturdays, 19 (ledig_lördag); work, 15 (arbete); lunch, 12 (lunch); employment, 11 (anställning); messaging, 11 (budskickning); and internal, 11 (intern).

5. Explaining the results: demand, supply, and institutional factors

So far, we have established a decreased frequency of messenger job titles overall in Swedish newspapers in the mid-twentieth century. In the same period, the visibility of janitors/caretakers, our reference category, remained stable. Moreover, spot checks in the national vacancy list do not suggest that employers switched from using newspapers to the Employment Service to recruit messengers in the relevant period.Footnote10 In this section, we discuss possible explanations for the disappearance of messenger jobs. We do not claim to quantitatively evaluate causal relationships. Our ambition is rather to make a preliminary assessment by combining our findings with previous research in relation to three types of explanations: demand, supply, and institutional factors.

5.1. Demand factors: structural change in retail

Errand boys and girls of the early and mid-twentieth century often were employed in retail trade (Håkansson & Karlsson, Citation2018; Kommittén för yrkesutbildning åt varubud m. fl., Citation1949). Yet, in our manual investigation of job advertisements in the 1960s, we find very few employers in retail trade announcing for messengers. Neither do we find many examples of specialised delivery firms.

The lack of retail trade businesses and delivery firms advertising for messenger jobs may be a consequence of more general structural changes in the retail trade and in the shopping habits of customers. In Sweden, the retail sector changed dramatically during the 1950s and 1960s. Stores became bigger, and employment in the sector increased (Gråbacke, Citation2002). There are many causes for this development. Motorism made its entrance, new residential areas were established, and reforms to increase competition was introduced.

From the 1930s, there were restrictions on competition, and these were of two kinds: (1) the restriction of new establishments and (2) a supplier-controlled price system (the gross price system) (Gråbacke, Citation2002). This changed during the 1950s. The two legal changes led to increased price competition, which in turn led to increased pressure for rationalisation. Of course, other factors were also important, in particular, changing consumer practices, accepting groceries and convenience goods to be sold in the same store. This led to the development of self-service stores, supermarkets, retail chains and hypermarkets in the outskirts of the town, where people went by car (Gråbacke, Citation2002, pp. 240–243).

In this new retail landscape formed in the 1960s, there was no place for errand boys and errand girls. This was made explicit in a newspaper article from 1964, where some Swedish merchants were interviewed (DN, Citation1964). The merchants were not interested in delivering goods to the customers. They explained that if the big hypermarkets did not offer home delivery, they did not see any reason to either. Only when the customers bought more than they could carry did the interviewed merchants offer home delivery for the price of two kronor. They claimed it was too expensive to offer home delivery – not only did they have to employ an errand boy, but this also required that a salesclerk be available to pack the groceries.

The falling frequency of errand boys and girls in job advertisements makes sense in the light of the structural changes in retail trade. Yet, most of the employers that used newspapers looking for young messengers were not retail businesses but big offices.

5.2. Demand factors: structural change in office work

Several studies have documented how office work changed dramatically during the twentieth century (see e.g. Conradson, Citation1988; England & Boyer, Citation2009; Fellman, Citation2010; Greiff, Citation1992; Parker & Jeacle, Citation2019). In fact, England and Boyer (Citation2009, p. 307) claim that ‘clerical work captures some of the major cultural, social and economic changes that have shaped the late nineteenth and twentieth century’. For example, the rationalisation of organisations and work processes more generally and the introduction of new technology more specifically (Bedoire, Citation1981; Boyer, Citation2004; Conradson, Citation1988; Parker & Jeacle, Citation2019). These changes meant increased differentiation of the office workers. In the nineteenth century, office workers were few in number and had high status and high responsibility. However, during the twentieth century, office work was divided into one (minor) high-status group that performed intellectual and managerial work and one (major) low-status group that performed repetitive, routine, non-intellectual work. This was a division of labour which led to the proletarianisation of office work (Conradson, Citation1988; Ericsson, Citation1982; Greiff, Citation1992).

During the 1930s and until the 1960s, errand boys were an important occupational group in offices. For every tenth office clerk, there was at least one errand boy ready to deliver messages (Conradson, Citation1988, p. 187). In offices, there were two kinds of unqualified youth jobs: errand boys and office pupils/office boys. The errand boys were to run errands externally, which also included bank errands (i.e. deposits in, or withdrawals from, the bank). The office boys were to serve the clerks in the office by, for example, sorting documents for the archive.

The errand boys were mobile, both geographically and socially. Because of this, they held a position that contained an information advantage. They delivered both written messages and spoken information, and by this, they entrenched themselves in information about the company and about individuals in the organisation. A boy that obtained a position as errand boy or office boy in a major office was expected to advance to clerk and maybe also to a managerial position (Conradson, Citation1988). As seen in section 4, these expectations were also articulated in the job ads.

Yet, the errand boys were not classified as office workers. Both male as well as female clerks could mark a distance towards them, and they were in many senses subordinated. The culture was patriarchal, and the errand boys had to run private errands for the clerks, even though this was not included in the formal work description. Organisationally, errand boys often belonged to the caretaker’s unit (Conradson, Citation1988, pp. 187–192).

During the 1950s and the 1960s, offices underwent significant change (see e.g. Conradson, Citation1988; Fellman, Citation2010). This change may be divided into two parts: organisational and technological. The organisational change can be connected to what was then a new view on how to organise office work driven by rationalisation and Scientific Management. Work was formalised, new management methods introduced, and dissemination of information systemised and formalised. Offices became organised in new ways, where specific units for the administration of the office (i.e. administration sections) were often introduced. Rationalisation was an important part of this process. Until then, each manager wanted their own secretary, which signalled status, but in the 1960s, it became more common to send all the typewriting tasks to a secretarial pool. Dissemination of information became a task for department and section meetings, with agendas and minutes, and not anymore, a task for errand boys and errand girls.

Correspondingly, along with organisational change came technological change. Punch card technology had already existed for decades, but after WWII, it came into more frequent use in offices. This technology is the precursor of computers. Computer technology started to be introduced in the offices in the 1960s, often in combination with punch card technology. Other technology that grew in importance and in use during the 1960s was electrostatic copying, the telephone and the telex machine (Conradson, Citation1988, pp. 212–217).

Due to these changes, the employee structure changed. The numbers of errand boys and the caretakers decreased significantly, while those with academic education became more common. Fellman (Citation2010) compares Sweden and Finland and claims that the increase of white-collar employees with a higher education was specifically significant in Sweden. A new group was IT personnel (‘computer people’), which, due to their expert knowledge of computers, became an important occupational group. Due to the increased demands on expert knowledge and schooling, being able to make a career as an errand boy was no longer a given.

Although the falling frequency of job advertisements for office boys seems to fit well in the overall history of office work in the 1960s and early 1970s, our study of the content of the ads calls for further consideration. On the one hand, we find fewer vacant messenger positions. On the other hand, the existing advertisements do not suggest that messengers had become redundant in the 1960s. There are two indications of continuing demand. Firstly, employers maintained their efforts to describe the appealing aspects of messenger jobs, including fringe benefits and good career prospects. Free Saturdays and training opportunities were often emphasised. Secondly, an increasing proportion of the messenger ads targeted elderly workers. A new occupation (or at least, a new title) became increasingly common from mid-1950s – the ‘grey lads’. What the motivations of employers may have looked like is explicit an ad for a grey lad posted by the advertising bureau of Schönkopf & Westrell AB. In the ad, the firm voiced its dissatisfaction and wrote how it was ‘tired of all the errand boys who disappear after a week, the broken mopeds, and the delivery agencies with too little people. We now believe in a real grey lad who can be trusted!’ (DN, Citation1966).

To make sense of the decreasing frequency of messenger ads and their content, we must look at the supply-side of the youth labour market, and the changes in the educational system in particular.

5.3. Supply factors: expansion and changes within the system of education

Until the beginning of 1952, the Swedish educational system consisted of a 7-grade primary school (starting at the age of seven), intermediate school (realskola) and secondary school (gymnasium), leading to academic studies. There were also different forms of education for vocational training. The apprenticeship system, as a heritage from the guild system, was not as legally regulated in Sweden as it was in Denmark and Germany. Instead, it was regulated by collective agreements between social partners (i.e. employers’ organisations and the labour unions). Apprenticeship schools and vocational schools were part time and aimed at young people working parallel with their studies.Footnote11

In the beginning of 1950s, a range of decisions were made concerning the education system in Sweden. Based on the 1946 school commission, Parliament decided to increase primary school to 9 years. This decision took more than 20 years to implement, but gradually, an increasing number of 15- and 16-year-olds (one’s age at Year 9) remained in school.

To some part, because of the Parliament decision in 1950 concerning primary schooling, a governmental investigation was also appointed in 1950 to investigate vocational education.

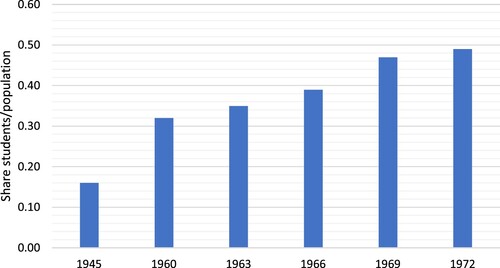

The rapid expansion of the Swedish system of schooling is illustrated in , which summarises the share of students in the population aged 16–19 in selected years. In 1945, around 15% of the 16- to 19-year-old young men and women were students. Fifteen years later, in 1960, this share had doubled to around 30%, and in 1972, it was close to 50%. This figure shows that the potential supply of messengers who were in their late teens was considerably reduced in the 1950s and 1960s.

Figure 6. Share of students in the population, ages 16–19. Source: Statistics Sweden, Statistical Yearbook, years 1950–1974.

Changes in the demand for messengers cannot account alone for the long-run patterns that we see in the job advertisements but need to be combined with supply-side changes related to the educational system. Interestingly, neither of these forces are emphasised as main drivers in Downey’s (Citation2002) account of the disappearance of the American telegraph messengers. In this account, it is rather institutional factors that are highlighted. After the 1930s, adult, skilled telegraph workers allied with the unskilled telegraph boys (Downey, Citation2002, pp. 169–170). In 1945, the telegraph workers achieved raised minimum wages, in line with national legal standard. However, Western Union, which was the dominant employer, then started to mechanise and use post offices and taxi services as subcontractors to carry its telegrams (Downey, Citation2002, p. 190).

5.4. Institutional factors: collective agreements and relative wages

Although there were a couple attempts by Swedish messengers to unionise, we must consider that the Swedish system of industrial relations was very different from the American. In Sweden, the wages of messengers were not so much determined by the union strength of this occupational group but rather by negotiations at higher levels. Highly organised employers and employees regulated wages and other working conditions through collective agreements (Lundh, Citation2020). Collective agreements were normative, which meant that they not only covered organised but also non-organised workers. Non-organised employers were expected to enter into collective agreements modelled upon what had been agreed upon by trade unions and employers’ organisations.

Centralisation and coordination of wage negotiation became fully developed in the mid-1950s, when the so-called solidaristic wage policy was formally established, but scholars disagree on when this policy was implemented in practice. Recent empirical research has identified two periods of wage compression more generally: during World War II (Prado & Waara, Citation2018) and from 1969 to the early 1980s (Molinder, Citation2019). Still, there are few in-depth studies on the long-run evolution of youth relative wages in Sweden and certainly no studies on the relative wages of messengers.

According to calculations by Edin, Forslund, and Holmlund (Citation2000, p. 358), the youth relative wage increased from 0.55 in 1968 to 0.80 in 1986.Footnote12 Focusing on a specific occupational group – salesmen and shop assistants – and with data compiled by Gustafsson and Tasiran (Citation1994), we can calculate relative youth wages from 1948 to 1989. Among salesmen and shop assistants, youth relative wages began to increase somewhat earlier. From having been stable, in the period between 1948 and 1960, the wages of 17- to 18-year-olds relative to 30- to 34-year-olds increased from 0.37 in 1960 to 0.56 in 1970.Footnote13 While we have not been able to find equivalent relative wages for errand boys and office messengers, the overall character of the Swedish system of industrial relations suggests that the development of relative youth wages was similar in the occupations of our main concern.

Based on the current state of research on relative wages, it is hard to make clear conclusions about the role of wage compression in making messengers more expensive for employers. Research on wage differentials more generally do not suggest the 1950s and 1960s as a period of major wage compression but rather the 1970s. That is after the number of messenger job ads had begun to decrease. Research on wages in retail trade, however, suggests that young workers’ wages improved substantially in the 1960s. But again, these wages do not directly refer to messenger jobs, nor office work.

6. Concluding discussion

There are several explanations for why messengers largely disappeared from the Swedish labour market in the decades after the Second World War. The aim of this article is not to strictly quantify the impact of these forces but rather to make a rough estimation of their relative importance and timing, as expressed through job ads.

Our investigation has revealed two patterns that, at first, may appear contradictory. First, we see that the frequency of ads for messengers decreases, which, all else equal, would suggest a reduced demand. Second, a closer investigation of the ads during the 1960s, when the frequency of ads was falling, shows that the advertisers continued in their efforts to make the messenger job appealing to young people. Free Saturdays, training opportunities and good career prospects were often emphasised. We do not find evidence that employers were relaxing requirements on skills or social capabilities. Office boys with some secondary education and good grades were often explicitly demanded. However, employers did become more flexible regarding the age requirements.

While we do not see any big changes in the age requirements for office boys, an increasing proportion of the messenger ads targeted elderly workers. As it seems, a new occupation (or at least, a new title) emerged in the 1950s – the ‘grey lad’. The grey lads did not replace the office and errand boys entirely, but it seems as though there were many tasks that were incorporated into grey lad tasks.

Our interpretation of these seemingly contradictory tendencies is that the disappearance of messengers was initiated by a fall in the supply. The fall in supply was brought about by the expansion of secondary schooling. This led to a shift in labour demand from the young (errand boys and office boys) to the elderly (grey lads). The services of messengers were still required in the big offices, and when not being able to recruit enough able office boys, employers expanded their search field. It is possible that technological changes (such as pneumatic dispatch, the telefax, computerisation) happening around that time also eventually reduced the demand for messengers. Another aspect that we have not discussed in detail, as it mainly takes place after our period of investigation, is the trend towards the outsourcing of service functions from in-house provision to external subcontractors.

In addition to the question of the disappearance of messenger jobs, this article also contributes to the understanding of the youth labour market. Clearly, being an errand or office boy in the period of investigation was considered a full-time job, with scheduled working hours and explicit terms of employment. Here, we see a clear difference in relation to the messenger jobs of the twenty-first century, which typically are thought of as precarious work and non-standard employment. Another difference is that the messengers of the twentieth century often were employed by big organisations with a broad range of activities. These organisations could function as internal labour markets, offering various pathways for young people to advance their careers. This aspect of the job was often emphasised in the ads. It is an interesting question for further research to investigate to what extent these career expectations were realised. In the twenty-first century, messenger jobs are often described as an entrance to the overall labour market but hardly as stepstones to future careers. Even when employed, today’s messengers typically work for specialised delivery firms that cannot function as internal labour markets.

This study was made possible because major Swedish newspapers were digitalised, and the database was opened for public use. There are, of course, some limitations in the method used here. First, we only used two newspapers (SvD and DN). Even though they are the biggest Swedish newspapers, they have a Stockholm bias. The labour market in Stockholm is for obvious reasons different from the labour market in the countryside and in minor Swedish towns. One reason is that, as the Stockholm labour market is bigger, it carries more opportunities and wages develop differently. Another is that the structure of the economy is different. All throughout the twentieth century, there is a centralisation of head offices in Stockholm (Petersson, Citation2008), and by this, an increasing demand for office boys. This calls for a study that would include other, minor cities and towns, as well as the countryside.

Second, the time period we study may be too late and too short to fully understand the disappearance of messengers. As we show, the downward slope starts already in the 1940s, even if it was in the 1960s that it became clear that the heydays of the messengers were gone. Therefore, to get a fuller picture of the disappearance of the messenger, we would need to examine a longer period.

Although there are limitations, we see that this approach of studying newspaper job ads is a fruitful method for understanding the content of past youth jobs. The content of youth jobs is in general under-researched, as they are less described and less organised by, for example, trade unions. The newspaper job ads do not give a full picture of the overall content of these jobs, but they do tell what is expected, what is offered, and to some extent, what the job involves. Further, the job ads give a richer picture of the content of the job than most quantitative data. Therefore, even though it is a limited amount of data, it is possible to analyse the jobs in terms of descriptive statistics. In the future, this kind of enquiry about the long-term changes and the content of youth jobs can serve as a basis for more focused research on individual experiences or case studies by using source material such as photographs or oral history material.

Finally, although this article has not set out to compare messengers of the twentieth century with the messengers of the twenty-first century, the findings in this article do not suggest a continuous line of development between these jobs. The messengers we study in the current article were not part of the gig economy but rather were employed in big organisations. Specialised delivery firms did exist in the period of investigation but did not appear frequently in the job ads sections of newspapers, or in any case they were not using the occupational titles we have included among our search terms. It is an interesting question for further research to investigate whether the delivery firms of the past used job ads to find workers, what kind of workers they looked for, and to what extent these firms and their business practices have links to modern-day delivery firms.

To sum up, apart from adding more knowledge to a common group of occupations, whose history has been largely unwritten, this article contributes to research on youth jobs and demonstrates some of the opportunities of using digitised newspapers as a source in economic and social history.

messengers-appendix-4.docx

Download MS Word (20.8 KB)messengers-appendix-3.docx

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)messengers-appendix-2.docx

Download MS Word (2.2 MB)Acknowledgement

Earlier versions of this article draft were presented at the Seminar in History and History Didactics (Malmö University), Seminar at Centre for Work Life and Evaluation Studies (Malmö University), DigitalHistory@Lund (Lund University), and the Workshop ‘Digital Methods in History and Economics’ (Hamburg University, University of Regensburg). The authors would like to thank the seminar and workshop participants for their useful comments. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The national vacancy list was published regularly in the journal Platsjournalen from 1963/1964 to 2017. We have made spot checks of the issues covering the month of October in 1965 and 1970, respectively. Although each issue included 10,000 vacant positions in 1965 and 16,000 in 1970, we hardly found any examples of messenger jobs listed. To all appearances, employers used newspapers or social networks to recruit messengers in mid-twentieth-century Sweden. How the relative importance of network recruitment changed over time is difficult to study. More generally, however, the increasing importance of networks took place long after our period of investigation (see Håkansson & Nilsson, Citation2019).

2 See Appendix 1 (see supplementary material).

3 Svenska Dagstidningar (https://tidningar.kb.se/).

4 This and the following number have been obtained by spot checks the first weekday in October in every tenth year from 1910 to 1970.

5 As a robustness check, we also searched for two tasks that are associated with messengers: internal post deliveries (intern postgång) and messaging (budskickning). The frequency of these terms showed a downward trend from the mid-1960s onwards.

6 Although errand boy as an occupational title is nowadays mainly associated with young men, we have been careful to include the search terms errand girl (springflick*) since previous research has indicated that there were also many young women in the occupation (Håkansson & Karlsson, Citation2018; Kommittén för yrkesutbildning åt varubud m. fl., Citation1949).

7 The search term ‘springflick*’ was not among the most frequent occupational titles. Note however that the occupational title ‘kontorsbud’ is gender neutral.

8 The job ads section (Arbetsmarknaden) of DN was divided into specific categories about the type of jobs demanded, which remained similar from the 1960s until 1980. These included for example ‘engineers, technicians’ (ingenjörer (och) tekniker), ‘clerks, office personnel’ (tjänstemän (och) kontorspersonal), ‘stock and storage personnel’ (lager- och förrådspersonal), ‘security personnel, janitors, messengers’ (bevakningspersonal, vaktmästare/vaktmästeri, bud), ‘transport and communication’ (transporter kommunikationer). We found that the job ad texts become longer and more elaborate since the late 1960s, which slightly reduced the number of ads published. The job titles demanded remained varied: teachers, school janitors, stock personnel, cooks, nannies, nurses.

9 These job ads (kontorsbud) are from 1961 to 1965 and they were looking for male or female workers, or a boy or girl to work in the office.

10 See Section 2, footnote 1.

11 For a full description of the establishment of the Swedish educational system 1940–1975, see Nilsson (Citation2013).

12 Edin et al. (Citation2000) compare the wages of 18- to 19-year-olds with the wages of 35- to 44-year-olds.

13 Own calculations, based on data from Gustafsson and Tasiran (Citation1994, pp. 97–98). The same data shows that the relative wages of 17- to 18-year-olds to 19-year-olds were at remarkably stable levels, around 0.80 from the late 1940s to the late 1980s (when the series ends).

References

- Alves, A. J., & Roberts, E. (2012). Rosie the riveter's job market: Advertising for women workers in World War II Los angeles. Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas, 9(3), 53–68.

- Bedoire, F. (1981). Den stora arbetsplatsen. In Sankt Eriks årsbok. (pp. 29–66).

- Boyer, K. (2004). “Miss Remington” goes to work: Gender, space, and technology at the dawn of the information age. The Professional Geographer, 56(2), 201–212.

- Burn, I., Button, P., Munguia Corrella, L. F., & Neumark, D. (2019). Older workers need not apply? Ageist Language in job ads and age discrimination in hiring. Working Paper no. 26552, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Conradson, B. (1988). Kontorsfolket: En etnologisk studie av livet på kontor (diss.) Univ. Stockholm, Stockholm.

- Cooper, M. (2021). ‘Blind alley’ to ‘steppingstone’? Insecure transitions and policy responses in the downturns of the 1930s and post 2008 in the UK. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–15.

- Deming, D., & Kahn, L. B. (2018). Skill requirements across firms and labor markets: Evidence from job postings for professionals. Journal of Labor Economics, 36(S1), S337–S369.

- DN. (1964, October 6). Husmor som vill ha hem maten är inte populär hos köpmännen. Dagens nyheter.

- DN. (1966, 10 October). “Grågosse” till annonsbyrå. Dagens nyheter.

- Downey, G. J. (2002). Telegraph messenger boys: Labor, technology, and geography, 1850-1950. New York: Routledge.

- Edin, P. A., Forslund, A., & Holmlund, B. (2000). The Swedish youth labor market in boom and depression. In David G. Blanchflower & Richard B. Freeman (Eds.), Youth employment and joblessness in advanced countries (pp. 357–380). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- England, K., & Boyer, K. (2009). Women's work: The feminization and shifting meanings of clerical work. Journal of Social History, 43(2), 307–340.

- Ericsson, T. (1982). Tjänstemännen i Sverige och Storbritannien före första världskriget. Arbetsförhållanden, löner och fackföreningssträvanden. In Bo Öhngren (ed.), Organisationerna och samhällsutvecklingen. En antologi. Stockholm: TCO.

- Fellman, S. (2010). Enforcing and re-enforcing trust: Employers, managers and upper-white-collar employees in Finnish manufacturing companies, 1920–1980. Business History, 52(5), 779–811.

- Fowler, D. (2014). The first teenagers: The lifestyle of young wage-earners in interwar Britain. New York: Routledge.

- Fridlund, M. (2020). Digital history 1.5: A middle way between normal and paradigmatic digital historical research. In P. Paju, M. Oiva, & M. Fridlund (Eds.), Digital histories: Emergent approaches within the new digital history (pp. 69–87). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

- Fridlund, M., & La Mela, M. (2019). Between technological nostalgia and engineering imperialism: Digital history readings of China in the Finnish technoindustrial public sphere 1880–1911. Tekniikan Waiheita, 37(1), 6–40.

- Greiff, M. (1992). Kontoristen: från chefens högra hand till proletär: proletarisering, feminisering och facklig organisering bland svenska industritjänstemän 1840–1950 (diss.). Univ. Lund, Lund.

- Gråbacke, C. (2002). Möten med marknaden. Tre svenska fackförbunds agerande under perioden 1945–1976 (diss.). Göteborg univ., Göteborg.

- Guldi, J. (2018). Critical search: A procedure for guided reading in large-scale textual corpora. Journal of Cultural Analytics, 1(2).

- Gustafsson, B., & Tasiran, A. C. (1994). Wages in Sweden since World War II – gender and age specific salaries in wholesale and retail trade. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 42(1), 77–100.

- Heim, C. E. (1984). Structural transformation and the demand for new labor in advanced economies: Interwar Britain. Journal of Economic History, 44(2), 585–595.

- Henningsson, E., & Henningsson, R. (1984). Springpojke i Helsingborg för längesen. Örkelljunga: Settern.

- Humphries, J. (2010). Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Håkansson, P., & Karlsson, T. (2018). På spaning efter springpojken ungdomsjobb och sociala nätverk vid sekelskiftet 1900. Historisk Tidskrift, 128(1), 33–62.

- Håkansson, P., & Nilsson, A. (2019). Getting a job when times are bad: Recruitment practices in Sweden before, during and after the Great Recession. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 67(2), 132–153.

- Håkansson, P., & Tovatt, C. (2017). Networks and labor market entry–a historical perspective. Labor History, 58(1), 67–90.

- Karlsson, T. (2019). Databasen Svenska Dagstidningar: Mycket text, mindre kontext. Historisk Tidskrift, 139(2), 408–416.

- Kommittén för yrkesutbildning åt varubud m. fl. (1949). Yrkesutbildning för varubud m. fl.: betänkande. SOU 1949:32. Stockholm.

- Kuhn, P., & Shen, K. (2013). Gender discrimination in job ads: Evidence from China. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 287–336.

- Licht, W. (2000). Getting work: Philadelphia, 1840–1950. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lundh, C. (2020). Spelets regler: Institutioner och lönebildning på den svenska arbetsmarknaden 1850-2018. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Molinder, J. (2019). Wage differentials, economic restructuring and the solidaristic wage policy in Sweden. European Review of Economic History, 23(1), 97–121.

- Nilsson, A. (2013). Yrkesutbildningens utveckling 1940–1975 [The development of vocational training 1940–1975]. In P. Håkansson, & A. Nilsson (Eds.), Yrkesutbildningens formering i Sverige 1940–1975 (pp. 21–37). Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Olsson, L. (1980). Då barn var lönsamma: Om arbetsdelning, barnarbete och teknologiska förändringar i några svenska industrier under 1800- och början av 1900-talet (diss.). Tiden, Stockholm.

- Parker, L. D., & Jeacle, I. (2019). The construction of the efficient office: Scientific management, accountability, and the neo-liberal state. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(3), 1883–1926.

- Petersson, T. (2008). Huvudkontorens lokalisering. In H. Lindgren, & T. Petersson (Eds.), Tillväxt & tradition: Perspektiv på Stockholms moderna ekonomiska historia (pp. 107–132). Stockholm: Stockholmia.

- Prado, S., & Waara, J. (2018). Missed the starting gun! Wage compression and the rise of the Swedish model in the labour market. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 66(1), 34–53.

- Rahikainen, M. (2017). Centuries of child labour: European experiences from the seventeenth to the twentieth century. New York: Routledge.

- Ros, R., Van Erp, M., Rijpma, A., & Zijdeman, R. (2020, May). Mining wages in nineteenth-century job advertisements: The application of language resources and language technology to study economic and social inequality. In Proceedings of the Workshop about Language Resources for the SSH Cloud (pp. 27–32).

- Rosenbloom, J. L. (1994). Looking for work, searching for workers: US labor markets after the Civil War. Social Science History, 18(3), 377–403.

- Schröder, L. (1991). Springpojkar och språngbrädor: Om orsaker till och åtgärder mot ungdomars arbetslöshet (diss.). Uppsala universitet, Uppsala.

- Schrumpf, E. (1997). From full-time to part-time: Working children in Norway from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. In N. de Coninck-Smith, B. Sandin, & E. Schrumpf (Eds.), Industrious children: Work and childhood in the Nordic Countries, 1850-1990 (pp. 47–78). Odense: Odense University Press.

- Schulz, W., Maas, I., & Van Leeuwen, M. H. (2014). Employer's choice – selection through job advertisements in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 36, 49–68.

- Scott, P. (2000). Women, other “fresh” workers, and the new manufacturing workforce of interwar Britain. International Review of Social History, 45(3), 449–474.

- Todd, S. (2006). Flappers and factory lads: Youth and youth culture in interway Britain. History Compass, 4/4, 715–730.

- Tovatt, C. (2013). Erkännandets janusansikte: det sociala kapitalets betydelse i arbetslivskarriärer (diss.). Santérus Academic Press, Stockholm.

- Ziegler, L. (2020). Skill demand and posted wages. Evidence from online job ads in Austria. Vienna Economics Papers

- vie 2002. University of Vienna, Department of Economics.

Data

- Statistics Sweden. Statistical Yearbook 1960–1975 Svenska Dagstidningar. https://tidningar.kb.se/