ABSTRACT

In 1867–1868 northern Sweden suffered from a famine that has not gained much scholarly interest. Here we study how this famine was relieved in Västerbotten county. We use unique regional and local administrative sources alongside other contemporary reports. Our results show that the relief quantities coming into Västerbotten county were significant, in proportion to the size of the population, the depth of the harvest failure, and in relation to historical state aid. In addition, we reveal the complex interplay between the state, market, and civil society that, at least on the county level, contributed to a seemingly efficient administration for alleviating the effects of harvest failure. However, our results point to bottlenecks in the administration of relief at the local municipal level, which call for further investigations.

1. Introduction

The idea for this article is simple and straightforward: in 1867 and 1868, Northern Sweden suffered from a famine that has yet to be given the scholarly scrutiny it deserves. In this article we present pioneering research on how that famine was relieved. Internationally, this famine is not well known which may partially be excused by the very limited interest shown by Swedish scholars themselves in conducting and publishing research on the topic. One reason for the lack of scholarly attention is that the typical famine indicator used by economic historians and famine scholars, i.e. rise in excess mortality, was marginal in Sweden on a national level during this famine. In addition, the simultaneous ‘great famine’ in the Grand Duchy of Finland, caused by the same cold-weather pattern, relativises and dwarfs any claims of a Swedish ‘famine’: Finland suffered from an extremely high excess death rate, seven per cent according to one crude but internationally acknowledged estimate (Ó Gráda, Citation2009, p. 23). However, there is little doubt that Northern Sweden also suffered from a food-supply crisis at this time, which was triggered by a major crop failure in 1867 and followed by a clear rise in mortality in 1868, especially in the two northernmost counties of Västerbotten and Norrbotten (Dribe et al., Citation2017; Nelson, Citation1988, pp. 82–83; Schön, Citation2012, p. 114). Västerbotten had the highest mortality rate (34.2 dead per thousand) of all Swedish counties in 1868. In other words, in a Swedish context Västerbotten suffered from a famine, but in relation to the Finnish context it is classified as a mild one.

This article focuses particularly on the relief mechanisms that were activated in Västerbotten in response to harvest failures in the 1860s, and how the state, market, and civil society mitigated the consequences of the famine.Footnote1 Surprisingly, little academic research has been done on the famine in Sweden, which leaves a great deal of room for new, original research. Marie Clark Nelson, who studied the famine in Norrbotten in her PhD thesis, published by Uppsala University in 1988, is the rare exception (Nelson, Citation1988). Still, it is not unusual in general Swedish historical writing, folklore, and popular histories to find remarks about a famine in the late 1860s (see e.g. Charpentier Ljungqvist, Citation2012, pp. 289–292; Häger et al., Citation1978; Svanberg & Nelson, Citation1992, p. 122). However, that literature often contains inconsistent and/or empirically unfounded claims, and is often oblivious of the international field of famine studies and broader transnational context of simultaneous famines in Sweden’s neighbouring countries. For example, international literature proposes emigration as a form of disaster relief (Ó Gráda & O’Rourke, Citation1997; Sadliwala, Citation2021). It has been suggested that famine triggered Swedes to migrate in large numbers in 1867–1869 (Carlson, Citation1979, p. 356), but emigration from Västerbotten was low and most emigrants originated from the south (Utterström, Citation1957, p. 119). In other words, there is a discrepancy between regional experiences, and a disconnect between Västerbotten and the overall national narrative. In addition, the Swedish relief administration has been criticised in many ways, although with limited empirical evidence: for providing too little, too late and on too harsh terms, and for failing to reach those in the direst need (Charpentier Ljungqvist, Citation2012, pp. 289–292; Magnusson, Citation2008, p. 132). The limited knowledge of how relief schemes functioned, including regional and local characteristics, is troublesome since it may be key to understanding why mortality differed regionally. There were also other factors that may have contributed to the increased mortality, such as the severity of the harvest failure, outbreaks of epidemics, and socioeconomic conditions. However, supported by previous research on Northern Sweden (see Nelson, Citation1988, pp. 148–149), we focus on the regional characteristics of relief schemes in Västerbotten. Furthermore, in 2018 the popular historian and journalist Magnus Västerbro made the astounding claim in his book Svälten (English: ‘starvation’) that the famine shaped and formed modern-day Sweden, without actually explaining how it happened (Västerbro, Citation2018). Although the period following the 1860s was formative (Schön, Citation2012), it needs to be emphasised that correlation should not be mistaken for causation. Thus, there is a need for more historically accurate information and understanding concerning the famine of the 1860s in Sweden.

With these considerations in mind, the aim of this article is to inform scholars of the 1867–1868 famine in Västerbotten county and to empirically reconsider several misconceptions concerning it, especially regarding the characteristics of the relief schemes. The aim is fulfilled by answering the following questions: How much famine relief arrived in Västerbotten? How was it distributed? What were the institutions and actors involved?

The various administrative and organisational levels of the Swedish society and state offer an abundance of sources that are rarely matched by those relating to other historical or even contemporary famines, especially those that occurred under more politically controversial circumstances (see eg. Devereux, Citation2007, pp. 3–4; Wheatcroft & Ó Gráda, Citation2017). Thus, the case of the famine in Västerbotten in 1867–1868 presents famine scholars with a unique opportunity to investigate administrative procedures in a food crisis, and to scrutinise the reasons for failure and success in greater detail than is often possible in other cases.

2. Background, sources, and methods

The spring and summer of 1867 were unusually cold in Northern Europe, which led to severe harvest failures in many places around the Baltic Sea and beyond. In general, cold winters do not pose a threat to Nordic agriculture since it is adapted to such climate (Huhtamaa & Charpentier Ljungqvist, Citation2021; Solantie, Citation2012). However, the late spring did cause problems since it delayed sowing for three to six weeks, depending on location, and the release of livestock to pasture. The delay alone meant that crops, and barley in particular, would have needed an unusually long and warm summer and autumn to ripen before the first night frost struck in August or September. The winter road on ice over the narrow strait of Kvarken between Västerbotten and Finland was still functional in mid-May of 1867, and many inland lakes lost their ice cover five to six weeks later than usual. This weather anomaly was so rare that only a few similar events have been estimated to occur each millennium (Charpentier Ljungqvist, Citation2012, p. 290; Huhtamaa, Citation2018, p. 50; Jantunen & Ruosteenoja, Citation2000). It resulted in regionally severe food shortages, and food prices soaring across Northern and Western Europe (Dribe et al., Citation2017, p. 194; Jörberg, Citation1972; Kennedy & Solar, Citation2007; Pitkänen, Citation1993, pp. 148–150; Ó Gráda, Citation2001). The result was a countrywide famine in the Grand Duchy of Finland, a regional famine in Northern Sweden, and a lesser-known famine in the Governorate of Estonia (Dribe et al., Citation2017; Häkkinen & Forsberg, Citation2015; Lust, Citation2015). Typically, scholars have investigated these events, and the flow and management of relief measures, within a national framework (Häkkinen et al., Citation1991, pp. 158–175; Newby, Citation2015, pp. 107–119). Geographically, vulnerability to the extreme weather conditions of 1867 was similar in Västerbotten and areas in Finland at the same latitude. Ideally, we would compare regional differences concerning relief measures in Sweden, Finland, and other regions across the Baltic Sea, but due to the lack of knowledge regarding how relief schemes functioned in Sweden’s core famished region of Västerbotten county, this article instead begins there.

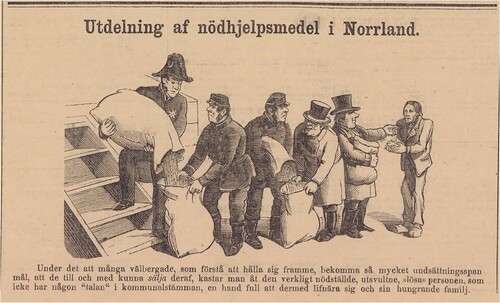

Conveniently, the bureaucratic Nordic societies provide valuable case studies in how central government responds top-down to regional scarcity problems (Van Bavel et al., Citation2020, pp. 105–110), since sources are relatively abundant (Voutilainen, Citation2016, p. 34). Firstly, we have witness testimonies: Sweden had a relatively high literacy rate and a free press, which reported on the event. The local newspaper Umebladet reported on and discussed the harvest failure – and its impact on increasing deprivation, begging, and mortality in several parishes in Västerbotten and elsewhere in Sweden – over the course of many articles (see e.g. Umebladet, 1 May 1868). Another newspaper, Fäderneslandet, actively criticised the authorities for their (mis)management of the crisis; is a cartoon which suggests that the relief diminished with each hand it passed through before reaching the intended recipient (Fäderneslandet, 14 December 1867). Secondly, Statistics Sweden provides trusted historical demographic data based on local parish records. The official demographic report of 1869 noted that the increased mortality in Västerbotten in 1868 was caused by an epidemic outbreak of typhoid fever, a typical famine-associated disease of the period,Footnote2 that was related to harvest failures, which weakened the population due to improper food intake and in tandem increased morbidity (BiSOS, serie A, 1868). In addition, we use information gathered from the County Governor’s five-year reports, bailiwick archives, and famine-relief-committee reports, which enable us to reconstruct and assess the famine-relief schemes.

Figure 1. Contemporary critique of the distribution of relief.

Source: Picture from the newspaper Fäderneslandet (14 December 1867), criticising the disproportionate quantities of relief that supposedly disappeared into the pockets of middlemen.

Archival work regarding Västerbotten involves certain methodological challenges. In 1888 the provincial capital, the town of Umeå, was destroyed by fire, as were many archival sources from the 1860s, including the archive of the provincial relief committee in Västerbotten. Given this, how do we research relief schemes when we lack the most vital primary sources? We know that the relief committee existed because we have other sources communicating with it, the most important being the Skellefteå bailiwick archive. Västerbotten county was at the time divided into three bailiwick districts: Skellefteå, Lappmarken, and Umeå. The latter’s archive was lost in the city fire in 1888, but the Skellefteå bailiwick archive contains a great deal of information on the local municipalities’ agriculture, economy, and – most importantly – the famine-relief transactions that were channelled through the bailiwick down to the municipalities. From these sources we can reconstruct how the famine relief was organised and transported through intermediaries, from the central relief committee in Stockholm to the relief committee in Västerbotten, down to the bailiwick’s storage facilities and further down to municipalities. The Skellefteå bailiwick archive contains bookkeeping relating to all conceivable kinds of relief transaction, combined with sporadic communication to actors involved in the process. The key actor was the bailiff Erik Johan Sparrman. However, there are some limits as regards the interpretation of this source material. One limit is that we cannot generalise how the municipalities distributed the received relief to households and individuals on a grassroots level, except for some individual cases that are indicated in the sources.

One final note should be made on famine-causation theories. Scholars agree that famines and their mortality are a multicausal problem, involving not only natural factors such as disruptive weather events – which destroy food production and facilitate the spread of lethal diseases – but also human factors such as politics, social institutions, socioeconomic status, inequality, market dynamics, population movements, and chosen relief measures (Dijkman & van Leeuwen, Citation2019; Howe & Devereux, Citation2007; Mokyr, Citation1983, pp. 2–3; Ó Gráda, Citation2009; Sen, Citation1981). The complexity of famine begins with the recognition that a famine is taking place in a certain moment and location, which in itself is motivated by political considerations (Howe, Citation2007). Therefore, it is reasonable to view famines as ‘complex emergencies’ (Keen, Citation2008). The magnitude of a famine is determined by both natural constraints on human societies, and human activity prior to and during it (Bankoff, Citation2004; Dijkman & van Leeuwen, Citation2019; Dyson & Ó Gráda, Citation2002, pp. 9–15). Dijkman and van Leeuwen (Citation2019) identify three interactive mechanisms of societal resilience to famine: the state, market, and civil society, which can substitute, complement, or work interdependently of one another. How the interaction functioned in practice in Västerbotten in response to the harvest failure of the 1860s is investigated in the subsequent section.

3. Results

3.1. Mortality, harvest outcomes, and influx of aid

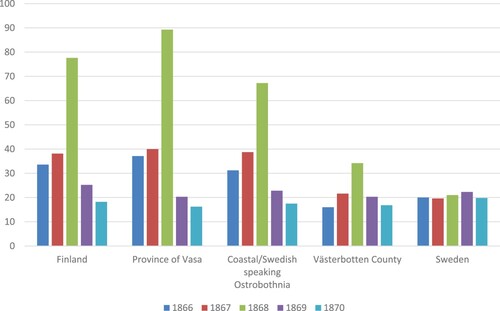

The County Governor’s five-year report for the period 1866–1870 informs us that Västerbotten had been severely affected by harvest failures. Indeed, in the report it is stated that the modest increase of the province’s population was due to an increase in deaths and net migration between counties. However, very few Västerbottnians emigrated abroad during the period (Historisk statistik för Sverige, 1969, p. 127). According to the report, harvest failures had induced people to eat less and had made them poorer, which, alongside disease in 1867 and 1868 in particular, resulted in a doubling of mortality, as can be seen in (BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, p. 2.). It also meant a 1.7 per cent reduction in the County’s total population between December 31, 1867 (90,815) and December 31, 1868 (89,237) (BiSOS, serie A, 1868, p. 1). It is a significant demographic response to a harvest failure. As a mortality rate it amounts to 34.2 dead per thousand – the highest in a Swedish cross-county comparison, and unusually high even by the County’s own historical standard (Nelson, Citation1988, pp. 82–83). Yet, this mortality increase did not match the increase in the nearby Finnish province of Vasa where mortality almost quadrupled, as can be seen in .

Figure 3. National and regional comparison of mortality rates in Finland and Sweden.

Source: Statistics Finland, Crude death rate. 1751–2021; Forsberg et al. (Citation1977), p. 245; Nelson (Citation1988); BiSOS, serie A. Befolknings-statistik 1866–1870.

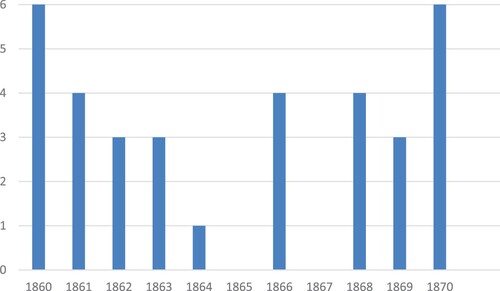

What characterised harvest outcomes in Västerbotten in the 1860s? The County Governor’s five-year report for 1861–1865 mentions the occurrence of harvest failures, but they did not result in any demographic responses worthy of discussion. Nonetheless, the purpose of remarking on them was to ensure and justify the continuity of state subventions aimed at the reclamation of peat soils for cultivation. According to the County Governor, the cause of harvest failures was not to be found in the people’s character nor in the region’s climate, but in the night frosts that rose from bogs. By draining the bogs more land could be used for cultivation, thus increasing the number of new settlers in the County’s forest-dense inland (BiSOS, serie H, 1861–1865). That is how the argument went, at least. Nevertheless, the harvest failure of 1867 seems to have been total. According to the County Governor it had been preceded by below-average harvests in the previous years (BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, p. 5), and if we are to believe a contemporary scale of harvest outcomes (see ) then 1865 was a total failure following a series of below-average harvests beginning in 1862 (Hellstenius, Citation1871). The contemporary scale is supported by the annually published county-level agricultural statistics collected by Västerbotten county’s economic society (Hushållningssällskap) from 1865 to 1870 (BiSOS, serie N, 1865–1870).

Figure 4. Harvests in Västerbotten, 1860–1870.

Note: 0 = total harvest failure; 1 = almost total harvest failure; 2 = meagre harvest; 3 = below or almost average harvest; 4 = average harvest; 5 = better-than average-harvest; 6 = good harvest (Hellstenius, Citation1871, pp. 77–119).

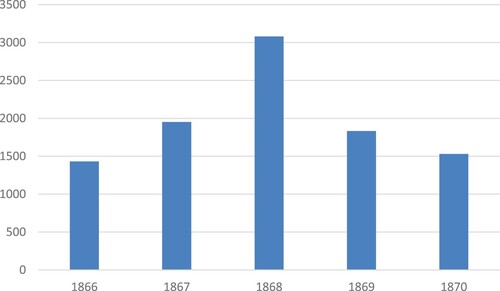

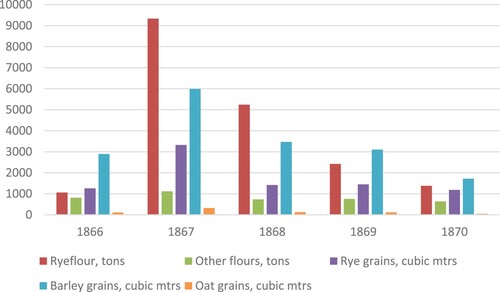

How much famine relief arrived in Västerbotten, in the form of grain and flour? The County Governor’s five-year report for 1866–1870 informs us that a substantial quantity of grain and flour came into Västerbotten, as can be seen in (BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, p. 4). Unfortunately, the five-year report for 1861–1865 does not contain similar information (BiSOS, serie H, 1861–1865), which makes assessing the normal level of grain imports difficult, as well as imports in relation to the supposed total harvest failure of 1865. Nonetheless, in 1867 Västerbotten received substantial quantities of grain, which in comparison to the ‘normal’ years of 1866 and 1870 represented a tenfold increase. In 1867 alone Västerbotten received 10,453 tons of flour, grain excluded. Converted into barrel measure it equals circa 89,341 barrels of flour for a population of 90,000.Footnote3

Figure 5. Incoming grain and flour to Västerbotten, 1866–1870.

Source: BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, p. 4.

The first takeaway of the results so far is that the quantity of food coming into the province was substantial. The additional flour imported in 1867 would have meant approximately 117 kilogrammes of flour per person, which in theory could provide subsistence for half a year for all inhabitants or for half of the population (circa 45,000) for a year. In addition, the incoming grain, which was likely primarily used as seeds, doubled from 1866 to 1867. Converted into barrel measure, approximately 58,335 barrels of grain and 89,341 barrels of flour arrived in Västerbotten in 1867 (in total 147,676 barrels). That inflow occurred before the winter sealed off the sea route, after which transport would have continued on a much smaller scale by horse-drawn sledges. The amounts should be understood as a minimum estimate of incoming cereals, on top of which were other food supplies, such as food already in the province and unaccounted-for imports.Footnote4 Thus, by all measures the quantity of food should have been plenty to keep the population alive. Furthermore, the level of imports was well above average even in 1868 (e.g. imports of rye flour exceeded 44,788 barrels), when the urgency of the situation led to a concentration of shipments to the first half of the year.

To put the quantity of incoming flour to Västerbotten in a broader context, it is worth mentioning that in the autumn of 1867 the Finnish Imperial Senate commissioned a relatively mere circa 63,850 barrels of relief flour and seeds for the three most northern provinces of Oulu, Vaasa, and Kuopio, which had a combined population of 729,000 in 1865 (eight times larger than the population of Västerbotten).Footnote5 Furthermore, Oiva Turpeinen calculated that, if all the allocated relief funds targeted for the three Finnish provinces had materialised during the 1867–1868 famine, they would have generated 130,000–140,000 barrels of grain (Turpeinen, Citation1986, pp. 156–158). If shared equally per capita, the relief would have provided subsistence for only one to one and a half months. In comparison, the quantity of cereals imported to Västerbotten must be considered substantial, since it could potentially have fed the County’s entire population for six months. In other words, Västerbotten received four times more cereals per capita than the Finnish northern provinces.

On the local level, the sheriff of Lövånger (a coastal parish circa 50 kilometres south of the town of Skellefteå) mentioned in his five-year report to the Skellefteå Bailiff that the harvest failure in 1867 had caused up to tenfold increases in imports of flour and grain compared to normal years.Footnote6 Although a rough estimate of imports, it is in line with the bigger picture, as shown in . Still, it is important to note that even in normal years some agricultural workers in Lövånger relied upon a grain market to deliver foodstuffs from either nearby or afar. The dependence on external grain markets may seem somewhat surprising as Lövånger’s local economy relied on traditional field cultivation, unlike the inland parishes where the harsher local climate and soil conditions made field cultivation much more hazardous. Nonetheless, the conclusion we draw from this is that Lövånger had an established market demand and trade contacts that could facilitate grain and flour imports from elsewhere when needed.

All things considered, Västerbotten county received large quantities of flour and grain, and the shipments arrived at the district granary well in advance of mortality beginning to peak in 1868. The bulk of relief arrived in 1867, before the winter ice sealed off the maritime transport routes.

3.2. Administration of famine relief

This section reconstructs the administration of famine relief in Västerbotten in the 1860s, exploring the following questions: How was it distributed? What were the institutions, and who were the actors involved?

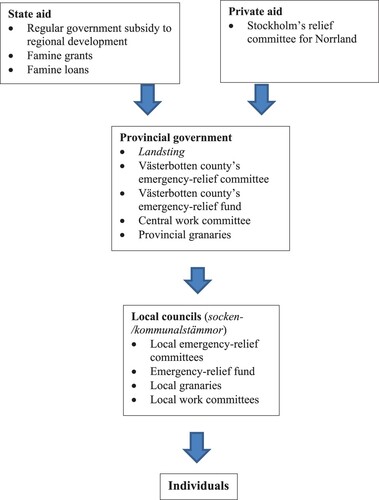

The famine-relief scheme set in motion in 1867 did not emerge out of nothing. A Poor Law system existed, which was based on parishes/municipalities providing for their ‘own’ poor (Engberg, Citation2005; Salmonsson & Spross, Citation2021, pp. 111–162). Characteristic of the provinces of Northern Sweden was that the Crown had a project to expand areas of cultivation by subsidising new settlers and forest workers and their families in the sparsely populated forested inlands (Utterström, Citation1957, p. 379). Many of the settlers received direct aid to help them succeed, in order to ensure a standing workforce to extract the Crown forest resources (BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, p. 18–19). Famine relief relied on state aid, and private aid through donations and philanthropic collections. Both types of aid consisted of cash and foodstuffs, and state aid was provided in the form of grants and loans (Redovisning, Stockholms undsättnings-kommitté för Norrland, 1869). On the regional level, aid was typically administered by a relief committee, which consisted of the County Governor and other high-ranking elite representatives. In Västerbotten a similar committee chaired by the County Governor was established in the autumn of 1867 (BiSOS, serie H, 1866–1870, pp. 18–19). Its main function was to coordinate incoming state and private aid from domestic and international sources, further down to local relief committees of parishes/municipalities.

What were the characteristics of the administration of famine in relief in Västerbotten, and how did it evolve in relation to recent experiences of harvest failure? The archival sources from the bailiwick of Skellefteå reveal several examples of relief activities in the 1860s. In 1863, for example, the County administrative board organised a purchase of 85 cubic metres (3240 cubic feet) of unspecified grain in support of Crown tenant settlers (krononybyggare) in the parishes of Burträsk, Norsjö (including Jörn), and Skellefteå. Registers confirm that the grain was collected from the crown granary in Skellefteå in the spring of 1864 (Förteckning öfver den spannmål som blifvit upphandlad. Spannmålsräkenskaper 1862–1868. Kronofogden i Skellefteå fögderi arkiv). Relief activities intensified in the spring of 1866 in response to the major harvest failure of 1865 (see ). Public action began in February, when the Crown gave instructions to the County Governor regarding how to use the grain in the regional granaries of Umeå and Skellefteå (Till Pastors Embetet i Sorsele. Spannmålsräkenskaper 1862–1868, Kronofogden i Skelleftå fögderi arkiv, G VI:1). It was stated that, although it was preferably to be used as payment to the poor for public work, grain could be distributed without repayment obligation to those who were not able to work or otherwise repay. Following the County Governor’s decision, several parishes were allotted relief. For example, Sorsele parish received 3.8 cubic metres (146 cubic feet) of grain, and the parish priest was called upon to ensure that it was distributed according to the County Governor’s instructions. After doing so, the priest was obligated to submit a report, which was reviewed by the municipal board. Transportation from the crown granary to the various parishes was typically organised privately. As regards individually allotted relief, several documents reveal that it was commonplace for intended recipients to issue certificates which enabled intermediaries to collect the grain on their behalf.

An example of how larger volumes of allotted grain were distributed is presented in the following: In April 1866, four sockenmänFootnote7 from Burträsk parish personally undertook the transportation of 3.1 cubic metres (120 cubic feet) of grain (Leveranskvitto, Burträsk den 10de April 1866. Spannmålsräkenskaper 1862–1868. Kronofogden i Skellefteå fögderi arkiv, G VI:1). The municipal board organised a subsequent delivery in May by means of a reversed auction, meaning that the lowest bidder undertook to transport a certain quantity of grain. In this case, nine bidders undertook to transport 0.55 cubic metres (21 cubic feet) each.

How did the administration of famine relief evolve in the 1860s, and how did it function in response to the harvest failure of 1867? summarises the main findings, showing the institutions and actors that made up the famine-relief administration, and different forms of famine relief. Nationally, following a reform in 1862, local councils shifted from parishes to municipalities (kommuner), and the offices of county governors to a new form of county councils (landsting). An important finding of our reconstruction is that district granaries remained an important institution in the organisation of famine relief in Västerbotten, making the County stand out in a national context.Footnote8 Our investigation reveals that the district granary in Skellefteå managed both state and private aid, in the form of grain, flour, and money (grants and loans). In 1865, leftover funds from previous relief activitiesFootnote9 were combined to form Västerbotten county’s emergency-relief fund. It was stated that the fund’s annually earned interest was to be used as grants ‘for those haunted by harvest failure or other unmerited misfortune’ (BiSOS, serie H, 1861–1865, p. 18) without repayment obligation. Similar funds were managed by local councils.Footnote10 After the harvest failure of 1867 had been acknowledged by the government, the state granted the county council (i.e. the landsting) a substantial loan of 45,000 riksdaler, which was to be used to promote handicraft work and purchase what was produced. The state also granted loans for similar purposes, i.e. subsidised work, to local councils.Footnote11

Figure 6. The administration of famine relief in Västerbotten in the 1860s. The illustration can be compared to Nelson’s (Citation1988, p. 123) findings concerning Norrbotten, to acknowledge regional differences.

Our investigation reveals that the coordinating mechanisms of the state and market were closely intertwined. Market institutions and actors were connected to all levels of the central, regional, and local government bodies shown in , as coordinators of e.g. transportation, storage, and insurance. Several examples of how this functioned in practice are presented in the following.

The central role of the provincial granary has already been emphasised. The granary in Skellefteå received substantial inflows of cereals by means of private shipping in the autumn of 1867. Transporting the grain from the coastal port to the granary in the town centre, a journey of circa 13 kilometres, also depended on private actors. The Bailiff’s meticulous accounts specify several costs; in addition to the captains’ fees they included fees for unloading, transportation, and measuring, as well as for using necessary measuring vessels. Furthermore, accounts concerning subsequent deliveries by boat reveal even more specific costs charged to the emergency-relief fund, such as fees for candles, rental compensation, and the purchase of cords from a local merchant that were used to close sacks. Fees also included storage and fire insurance. In the winter of 1867/1868, when no ships could arrive due to frozen seaways, regional redistribution of grain occurred, as shown by two deliveries from Umeå that arrived in Skellefteå on December 7 and January 21. Withdrawals and deliveries from the granary to the various parishes of the district started on November 4 and continued throughout the winter and the following spring.Footnote12 Municipal boards organised and paid for transportation, and for the grain that was not assigned as free grants.

3.3. Contemporary assessments of relief structures

You noble people, receive from the population of Västerbotten County a heartfelt thanksgiving for what you have done for us […] You have acted as the hands of God to save countless victims from certain death by starvation (Letter of thanks, Umebladet, 9 October 1868).Footnote13

Table 1. Financial state aid for harvest failure given to Västerbotten county, 1862–1867 (riksdaler riksmynt).

In addition to the approved state aid, the County Governor stated that the provincial government’s call for private aid in 1867 had been necessary to meet demand. The County Governor claimed that ‘most of’ the monetary donations had been used to purchase cereals, which had been distributed without repayment obligation to those who were most in need. However, ‘some’ of the aid had been distributed in exchange for public work, mainly roadworks. In addition, some of the donations had been reserved for providing seed to less wealthy farmers, on condition of repayment of 1/3 of the allotted amount.

As early as 1869, substantial amounts had been repaid to the County’s emergency-relief fund, reflecting the better harvest in 1868. The value of the County’s emergency-relief-fund had increased from 15,591 riksdaler in 1865, to 53,612 riksdaler in 1870, and distributed a total of 2,842 riksdaler in grants during the period 1866–1868 to ‘a lot of poor people haunted by failed harvests’ (BiSOS, serie H, 1861–1865, p. 18). Similarly, the local relief fund for Bygdeå parish had more than doubled in value: from 1156 riksdaler in 1865 to 2763 riksdaler in 1870. The Skellefteå parish emergency-relief fund, in contrast, only increased slightly, from 33,131 riksdaler in 1865 to 35,192 riksdaler in 1870. The County Governor stated that the reasons for the fund’s modest growth were that earned capital had been used as poor relief after failed harvests, and a price drop for farmsteads on which the fund’s value depended.

In 1870, the County Governor concluded that Västerbotten was still suffering financially from the consequences of the 1860s harvest failures. Municipalities were burdened by loans and increased costs for poor relief, which had continued to rise until 1869. Increased private debt and bankruptcies, and subsequent sales by authority of law, put additional strain on poor relief and ability to pay taxes, showing how economic and social consequences became intertwined. However, the County Governor noted that parishes located in Lappmarken, i.e. where the Sami population lived, had not suffered the same fate. shows the development of municipal expenses, including poor relief, for Västerbotten.

Table 2. Municipal expenses, including poor relief, in Västerbotten, 1866–1870 (riksdaler riksmynt).

In summary, our results show that in 1867, 147,676 barrels of cereals (flour and grain) arrived for a population of a little less than 90,000. The bottom line is that plenty of relief arrived on time before the shipping season came to an end in the autumn of 1867, and shipments continued at above average level in the following year as well. Moreover, the central actor at the regional level was the Bailiff, who oversaw the district granary. He was the main coordinator and mediator between the municipal authorities and the county-level relief work and emergency-relief committees. Furthermore, distribution of aid in the form of seed and foodstuff to their targeted destinations was dependent on private actors. In addition, the relief that did come into the district granary seemingly moved swiftly to the local authorities and relief committees.

4. Discussion

4.1. International implications

Our case of the relief measures undertaken in response to a major harvest failure in the 1860s in Västerbotten, Northern Sweden, offers new insights to the international academic field of famine history. Firstly, we want to stress the importance and complexity of adapting regional and comparative perspectives in famine studies. The weather anomaly wrecked harvests all around the Baltic Sea, albeit with regional variations, but the effects in Sweden in terms of famine-related deaths were comparatively mild. Even severely affected Swedish regions such as Västerbotten appear to be a relative success story, in terms of relief being obtained and the increase in mortality rate being relatively small as compared to e.g. adjacent regions in the Grand Duchy of Finland. However, in comparison to other Swedish counties it seems more like a failure. Irrespective of which comparative benchmarks we use, Västerbotten stands out as an anomaly which deserves more scholarly attention.

Our study has focused on the relief measures put in place in Västerbotten. Naturally, a starting point could have been to investigate the demographic response to the harvest failure and then proceed to an analysis of the relief measures. However, since it has been hinted in the Swedish literature that relief arrived too little and too late, for example by the historians Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist and Lars Magnusson, as well as displays in the local museum in Skellefteå (Forsberg, Citation2023), we felt that this topic was a suitable starting point with regard to historiographic debates in Sweden.

We observed that the relief coming into Västerbotten county arrived in significant quantities: in proportion to the size of the population and the magnitude of the harvest failure, and in relation to historical state aid. However, this does not negate a thorough demographic analysis. Indeed, if the quantity of relief coming into Västerbotten county was plenty and more than expected, the reasons behind a doubled mortality rate are an even greater conundrum. Hence, our results have led us to the following recommendation for future research: if there were distribution bottlenecks in the relief administration in Västerbotten that contributed to increased mortality then future studies ought to identify the bottlenecks at the local level. In addition, other factors besides relief administration play a part in determining the demographic outcome during famines. Examples of possible factors are the extent of the local harvest losses (see e.g. Edvinsson, Citation2012), the overall vulnerability of local economies to weather shocks, other side incomes, outbreaks of epidemics, organisation of poor relief and healthcare, and extent of migrants coming and going. Our study calls for more studies on these factors in order to provide an empirical foundation for comparisons with adjacent regions.

Our case of Västerbotten showcases the complex interplay between the state, the market, and civil society in effective administration of relief, and certain characteristics which make the region stand out nationally and maybe even internationally. Future international comparisons could assess the relief administration in further detail, although our results suggest the need for caution when extrapolating relief models. Thus, we postulate that regions in Sweden and elsewhere had considerably different challenges and opportunities in coordinating the state, the market, and civil society in order to efficiently provide relief measures. Regions across the Baltic Sea were not equal in terms of access to commodity and financial markets, and in terms of state aid.Footnote16 Our tentative comparison with the three most northern Finnish provinces in terms of aid per capita could go some way to explaining the lower mortality figures in Västerbotten as compared to the Finnish side of the Gulf of Bothnia. However, we restrain ourselves from speculating on this matter until more comparative and conclusive studies have been undertaken.

Finally, scholars should ask: what made some Swedish rural economies and/or its national economy more resilient, and its famine-relief measures seemingly more efficient? Even if our focus has been on a single Swedish county and its famine-relief scheme, Västerbotten was not in isolation from the rest of the world, which is proven by the quantities of relief that it managed to mobilise from elsewhere. Thus, in light of our results we welcome a reconsideration of the simultaneous ‘greater’ famines in Estonia and Finland with respect to how relief operations there managed to utilise state capacity and market mechanisms, as well as the popular notion of Sweden in the 1860s as a supposedly weak state with a poor economy (see e.g. Lagerqvist, Citation2022, pp. 161–162; Schön, Citation2012, p. 65; Västerbro, Citation2018, p. 37).

4.2. Swedish implications

There is room for debate regarding how scholars should define and apply the term ‘famine’ with regard to Northern Sweden in the 1860s. The idea is often expressed in Swedish as svält, i.e. starvation, which is a narrower term than the one often applied within international famine studies. The latter typically applies ‘famine’ as a term for a broader crisis in which starvation is only one component, comparable to the Swedish term nöd. Famines often occur under chaotic and conflict-related circumstances in weak and underdeveloped states (Ó Gráda, Citation2009, pp. 274–278; Schön, Citation2012, p. 65), and politics is ever-present in one way or another (Devereux, Citation2007, pp. 7–9). Does this apply to Sweden in the 1860s? Sweden was at the time not among the poorest countries in Europe (Morell, Citation2011), nor was Västerbotten county the poorest of Swedish counties as measured in regional GDP per capita (Enflo & Rosés, Citation2015, p. 196). Our study shows that the state had resources and the ability to report on, inquire into, and alleviate a potential famine that would have developed in adjacent regions into what Alex De Waal calls ‘a famine that kills’ (De Waal, Citation2005). With these considerations in mind, our results problematise the definition and application of the term ‘famine’ in Västerbotten, and call for a more nuanced debate on how it fits into the general narrative of Sweden’s economic and social development during the latter half of the nineteenth century. One point of contestation is whether the number of excess deaths is high enough for it to be counted as a famine, in the historical context of a total harvest failure in a preindustrial society. In addition, if we accept that excess mortality defines a famine, does it or should it matter what people died from? Finally, a point to be made is that famines are almost always preceded by poverty and malnutrition that are pushed beyond a critical threshold after a particular event, such as a harvest failure.

Paradoxically, a precondition of a successful relief measure is that someone powerful enough shouts ‘famine!’ before it turns out to be one,Footnote17 which leads the historical demographer to be perplexed as to whether there ever was a famine. Having said that, we do agree that the harvest failure in 1867 on top of the previous years’ meagre harvests did present an urgent food shortage for people in Västerbotten, and because of this people died in larger numbers than usual. However, our task has not been to explain why people died. Our study would suggest that the relief aid that was sent to Västerbotten county did reduce the shortage of food caused by the harvest failure – not entirely, but significantly enough to avoid similar death rates as occurred in neighbouring Finland.Footnote18

The claim of the County Governor that deaths due to starvation were averted thanks to the bountiful help his county received does not correspond to predominant narratives that have been presented by historians and journalists alike (Forsberg, Citation2023). However, such contradictory remarks are not unusual when it comes to famines, since state and local authorities often downplay starvation deaths that are indicative of gross socioeconomic injustice upheld by institutional arrangements. Similarly, deaths linked to diseases point to causes that authorities only have limited influence over (Forsberg, Citation2020, pp. 56–57; Newby, Citation2023, p. 55).

Our results show that relief came into Västerbotten county and reached the municipalities, but whether from there it reached those in direst need requires further targeted study. We do not know how a society that developed a food shortage which then led to an influx of relief still suffered from several typical famine symptoms, such as increased begging and migration, soaring food prices, lower wages, higher mortality, and reduced births (Devereux, Citation2007; Dijkman & van Leeuwen, Citation2019; Jutikkala, Citation1993; Mokyr & Ó Gráda, Citation2002; Sen, Citation1981). Perhaps the cause was the municipalities’ distribution, the way relief work projects were organised, the treatment of the sick and infirm, or something else. Regardless, we need to know what really happened in local communities.

There is an idea in the literature, as well as among contemporary observers, that a large portion of the intended relief went into the pockets of middlemen. While our study does not disprove that such losses may have occurred, we see no evidence of it on the county and bailiwick levels. The relief aid that came into the bailiwick granary was swiftly transported to the allocated municipalities. In addition, the Bailiff had a separate monetary budget for expenses. He used cash to pay for services, including different stages of transport, measuring, unloading, repacking, and insurance payments. Hence, we do not find support for the picture presented in Fäderneslandet (see ), where grain intended for relief went into the pockets of middlemen. The relief scheme’s success relied on an integration of the state, the market, and civil society, and the monetary economy of Västerbotten seemingly functioned well at the time.

On the same note, state aid typically came in monetary form as loans, and receivers were expected to pay back much of the received aid to relief funds. State aid in monetary form indicates a functioning credit market, but to what extent it enabled municipalities and households to postpone or smooth out the effects of the crisis over a longer period requires further investigation. Accounts from contemporary Finland suggest that local municipalities were unwilling or unable to take loans offered to them by the state for fear of individual households defaulting on them. Thus, local communities not only experienced food shortages but were short on cash and credit, which exacerbated the economic squeeze on food supplies locally (Häkkinen, Citation1999; Pipping, Citation1961, pp. 355–393; Voipaala, Citation2021).

From previous studies we know that farmers’ forests were increasingly transferred to sawmill companies in Västerbotten during this period (Fagerberg, Citation1973). Preliminary results from Burträsk and Vännäs municipal archives suggest that credit markets were actively utilised as a coping mechanism. Loans could be taken out by municipalities and private households because there was a belief that the loans could be repaid in the years to come. Seed and flour could be bought by the local population because the state, civil society, and private actors facilitated relief transport on steamboats and other vessels, and various forms of debt arrangement provided the necessary entitlements, i.e. money and/or credit, with which to buy incoming food locally.

In conclusion, our results show that the coordinating mechanisms of the state, the market, and civil society had an opportunity to succeed in Västerbotten. However, our results do not mean that the coordination succeeded everywhere, since local variations certainly existed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Jan Wallanders och Tom Hedelius stiftelse samt Tore Browaldhs stiftelse for financial support during the work on this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Dijkman and van Leeuwen (Citation2019) for an extensive discussion of famine-relief mechanisms from a historical perspective.

2 The classification of diseases and causes of death used in the 1860s do not correspond to modern medical knowledge. Typhoid fever (nervfeber) was one of a group of diseases, along with typhus and relapsing fever, that were discussed interchangeably at the time but are now considered to be completely different diseases (Nelson, Citation1988, pp. 100–104). In Finland in 1868, nearly half of deaths were attributed to ‘typhus’, which would have included typhoid fever as well (Pitkänen, Citation1993, p. 70).

3 Conversions of contemporary measurements to the metric system (and in some cases barrels) are based on information from the same source, i.e. the official statistics/BiSOS: 1 barrel of grain = 165 litres; 1 cubic foot = 10 kannor = 26,17 litres; 1 centner = 42.5 kg; 1 barrel of autumn rye = 117 kilogrammes (Morell, Citation1988; Grönros et al., Citation2015).

4 A contemporary remark in the official statistics explains the difficulty in estimating the total quantity of incoming grain due to large, unaccounted-for influxes (BiSOS, serie N, 1867, p. 29). As a possible example of this, in mid-May 1867 a large caravan consisting of 90 sledges left the town of Umeå and travelled on the still-frozen winter road over the sea to the town of Vasa (officially Nikolaistad) on the Finnish west coast to buy cereals, in total approximately 270 sacks of flour (Forsberg, Citation2021, p. 428; Forsberg, Citation2018, p. 496). It is unknown whether these volumes were included in the official statistics, but it is safe to say that they were not part of the relief accounts that were started only in the autumn of 1867. Nevertheless, our point is that the County Governor statistics should be interpreted as the minimum imports to the county.

5 See for example, SVT VI:1. Väkiluvun-tilastoa. Helsinki 1870, p. 15.

6 Handlingar angående femårsberättelser 1843–1880. Lövånger socken. Kronofogden i Skellefteå arkiv.

7 A sockenman was a propertied farmer with full tax liability and voting rights.

8 See Nelson (Citation1988, pp. 117–119) and Utterström (Citation1957, p. 379) for further information on regional variations concerning the role of district granaries. Provincial and local granaries were part of a state-enforced system for storing grain, which was to be used in times of need as either grants or loans. The system was established earlier in the southern provinces but was not well developed in the northern provinces until the mid-nineteenth century. These granaries in their old form were abolished in 1863 and were typically turned over to municipal councils as cash funds. However, Västerbotten was one of the counties (along with Älvsborg, Göteborg, Bohus, and Norrbotten) that retained the institution.

9 The County Governor’s five-year report for the period 1861–1865 refers to leftover funds from two sources: state aid without repayment obligation that had been allotted to Västerbotten in the wake of the 1862 harvest failure, and private donations such as charity fundraising in response to the 1865 harvest failure.

10 The County Governor’s five-year report mentions the funds of Skellefteå and Bygdeå municipalities specifically.

11 Bygdeå parish was granted a loan of 40,000 riksdaler for promoting shipbuilding, including purchasing of timber. State aid was also granted specifically to provide for the Sami population in Vilhelmina, Sorsele, and Stensele parishes.

12 Accounts concerning withdrawals from the provincial granary reveal that aid in support of public work was common. For example, a withdrawal on November 4 went to a road-construction project in Burträsk parish.

13 Letter of thanks, on behalf of County Governor E. V. Almquist and the County Council/landsting. Translated by the authors.

14 These sums trend in the same direction as those presented by Utterström (Citation1957, pp. 388–389). His source was the central government’s state office archive, which seemingly did not include grants given to provinces (at least not for every year), while our source is the recipient county. In addition, Utterström’s figures may diverge from ours due to the way he accounted for the value of received relief in natura. See also Gadd et al. (Citation2007, p. 333).

15 For broader context, see Utterström (Citation1957, pp. 372–387).

16 For Estonia, see for instance Lust (Citation2015).

17 The Swedish state and the Grand Duchy of Finland had an institutionalised system with the intention of deploying state aid in good time, which enabled county governors to react swiftly to unfolding events. Since 1799 there had been a system in which they, with the support of reports from the sheriffs (länsmän), submitted crop reports to the Crown each July, August, and October. The first two reports each year concerned growing, i.e. not-yet-gathered, crops, and the last report in October concerned the harvested crop (Hedqvist, Citation1999). However, since the same institutionalised system was in active use in both countries, it should not be given too much power in explaining the swiftness of the Swedish (or inertia of the Finnish) realised relief measures (Reese, Citation2017, p. 92).

18 We acknowledge the urge to explain the broader context regarding why the Finnish famine developed into the catastrophe it did. However, that discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

References

Archival sources

- Landsarkivet i Härnösand, Kronofogdens i Skellefteå fögderi arkiv 1738–1918.

Online sources

- Statistics Finland’s free-of-charge statistical databases, Crude death rate. 1751–2021: https://pxdata.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/sv/StatFin/StatFin__kuol/statfin_kuol_pxt_12al.px/table/tableViewLayout1/ (last visited 4.10.2023).

Printed sources

- BiSOS (Bidrag till Sveriges offentliga statistik), statistikserie A, befolkning.

- BiSOS, statistikserie H, femårsberättelser.

- BiSOS, statistikserie N, jordbruk – Hushållningssällskapens årsberättelser.

- Fäderneslandet. Svenska dagstidningar. Kungliga biblioteket. https://tidningar.kb.se/

- Historisk statistik för Sverige. Del 1. Befolkning. Andra upplagan, 1720–1967. Statistiska centralbyrån. Stockholm: KL Beckmans Tryckerier AB (1969).

- Redovisning för den insamling af penningar och lifsförnödenheter, som egt rum åren 1867–1868 genom Stockholms undsättnings-kommitté för Norrland. Stockholm: Ivar Hꜳggströms boktryckeri (1869).

- SVT VI:1. Suomenmaan Virallinen Tilasto. VI Väkiluvun-tilastoa. Ensimmäinen vihko. Suomen Väestö Joulukuun 31. P 1865. Helsinki 1870.

- Umebladet. Svenska dagstidningar. Kungliga biblioteket. https://tidningar.kb.se/

Literature

- Bankoff, G. (2004). Time is of essence: Disasters, vulnerability and history. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 22(3), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700402200303

- Carlson, S. (1979 [1961]). Svensk historia 2. Fjärde upplagan. Esselte studium.

- Charpentier Ljungqvist, F. (2012). Klimat, missväxt och extremt väder 1830–1920. In B. Stråth (Ed.), Sveriges historia 1830–1920 (pp. 289–292). Norstedts.

- De Waal, A. (2005). Famine that kills: Darfur, Sudan (Revised ed). Oxford University Press.

- Devereux, S. (2007). Introduction: From ‘old famines’ to ‘new famines’. In S. Devereux (Ed.), The New famines: Why famines persist in an era of globalization (pp. 1–26). Routledge.

- Dijkman, J., & van Leeuwen, B. (2019). Resilience to famine ca. 600 BC to present: An introduction. In J. Dijkman & B. van Leeuwen (Eds.), An economic history of famine resilience (pp. 1–13). Routledge.

- Dribe, M., Olsson, M., & Svensson, P. (2017). Nordic Europe. In G. Alfani & C. Ó Gráda (Eds.), Famine in European history (pp. 185–211). Cambridge University Press.

- Dyson, T., & Ó Gráda, C. (2002). Introduction. In T. Dyson & C. Ó Gráda (Eds.), Famine demography: Perspectives from the past and present (pp. 1–18). Oxford University Press.

- Edvinsson, R. (2012). Harvests and grain prices in Sweden, 1665–1870. The Agricultural History Review, 60(1), 1–18.

- Enflo, K., & Rosés, J. R. (2015). Coping with regional inequality in Sweden: Structural change, migrations, and policy, 1860–2000. Economic History Review, 68(1), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.12049

- Engberg, E. (2005). I fattiga omständigheter: Fattigvårdens former och understödstagare i skellefteå socken under 1800-talet. Umeå universitet.

- Fagerberg, B. (1973). The transfer of peasant forest to sawmill companies in northern Sweden. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 21(2), 164–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.1973.10407769

- Forsberg, H. (2020). Famines in mnemohistory and national narratives in Finland and Ireland, c. 1850–1970. University of Helsinki. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/308655

- Forsberg, H. (2021). “För den svenska befolkningen frukta vi icke.” Är 1860-talets svält i Österbotten en bortglömd episod i historien om det Svenska i Finland? Historisk tidskrift för Finland, 106(3), 406–439.

- Forsberg, H. (2023). Scandia debatt: Den svårsmälta svälten. Forskningen om 1860-talets hungersnöd i rige. Scandia: Tidskrift för Historisk Forskning, 89(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.47868/scandia.v89i1.25210

- Forsberg, H. M. (2018). ‘If they do not want to work and suffer, they must starve and die.’Irish and Finnish famine historiography compared. Scandinavian Journal of History, 43(4), 484–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2018.1466859

- Forsberg, K.-E., (1977). Befolkningsutvecklingen efter år 1749 Svenska Österbottens landskapsförbund (Ed.), Svenska Österbottens historia I (pp. 213–303). Svenska Österbottens landskapsförbund.

- Gadd, C-J, (2007). On the edge of a crisis: Sweden in the 1840s. In C. Ó Gráda, R. Paping, & E. Vanhaute (Eds.), When the potato failed: Causes and effects of the last European subsistence crisis, 1845–1850 (pp. 313–342). Brepols.

- Grönros, J., Hyvönen, A., Järvi, P., Kostet, J., Rantatupa, H., Väärä, S., (2015). Tiima, tiu, tynnyri: Miten ennen mitattiin, suomalainen mittasanakirja. Turun maakuntamuseo.

- Häger, O., Torell, C., & Villius, H. (1978). Ett satans år. Sveriges Radios förlag.

- Häkkinen, A. (1999). Nälkä, valta ja kylä 1867–1868. In P. Haapala (Ed.), Talous, valta ja valtio: tutkimuksia 1800-luvun Suomesta (pp. 111–130). Vastapaino.

- Häkkinen, A., & Forsberg, H. (2015). Finland’s ‘famine years’ of the 1860s. In D. Curran, L. Luciuk, & A. G. Newby (Eds.), Famines in European economic history: The last great European famines reconsidered (pp. 99–123). Routledge.

- Häkkinen, A., Ikonen, V., Pitkänen, K., Soikkanen, H., (1991). Kun halla nälän tuskan toi: Miten suomalaiset kokivat 1860-luvun nälkävuodet. WSOY.

- Hedqvist, L. (1999). Subjektiva skördebedömningar under nästan 200 år. Årsväxtrapporteringen 1799–1990. In U. Jorner (Ed.), Svensk jordbruksstatistik 200 år (pp. 141–162). Statistiska centralbyrån. (SCB).

- Hellstenius, J. (1871). Skördarna i Sverige och deras verkningar. Statistisk tidskrift häfte, 28–31.

- Howe, P. (2007). Priority regimes and famine. In S. Devereux (Ed.), The New famines: Why famines persist in an era of globalization (pp. 336–362). Routledge.

- Howe, P., & Devereux, S. (2007). Famine scales: Towards an instrumental definition of ‘famine’. In S. Devereux (Ed.), The New famines: Why famines persist in an era of globalization (pp. 27–49). Routledge.

- Huhtamaa, H. (2018). “Kewät kolkko, talwi tuima” Ilmasto, sää ja sadot nälkävuosien taustalla. In T. Jussila & L. Rantanen (Eds.), Nälkävuodet 1867–1868 (pp. 33–65). Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

- Huhtamaa, H., & Charpentier Ljungqvist, F. (2021). Climate in Nordic historical research – a research review and future perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of History, 46(5), 665–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2021.1929455

- Jantunen, J., & Ruosteenoja, K. (2000). Weather conditions in Northern Europe in the exceptionally cold spring season of the famine year 1867. Geophysica, 36(1–2), 69–84.

- Jörberg, L. (1972). A history of prices in Sweden 1732–1914, volume One. Lund.

- Jutikkala, E. (1993). Frost or microbes. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 41(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.1993.10415861

- Keen, D. (2008). Complex emergencies. Polity.

- Kennedy, L., & Solar, P. M. (2007). Irish agriculture: A price history from the mid-eighteenth century to the eve of the first world War. RIA.

- Lagerqvist, C. (2022). Från fattigdom till välstånd: Sveriges flykt från vardagshunger och för tidig död. Dialogos.

- Lust, K. (2015). Providing for the hungry? Famine relief in the Russian Baltic province of Estland, 1867–9. Social History, 40(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071022.2014.991196

- Magnusson, L. (2008). Industrialismens genombrott. In J. Christensson (Ed.), Det moderna genombrottet (pp. 99–137). Lund.

- Mokyr, J. (1983). Why Ireland starved: A quantitative and analytical history of the Irish economy, 1800–1850. Routledge.

- Mokyr, J., & Ó Grάda, C. (2002). Famine disease and famine mortality: Lessons from the Irish experience, 1845–50. In T. Dyson & C. Ó Gráda (Eds.), Famine demography: Perspectives from the past and present (pp. 19–43). Oxford University Press.

- Morell, M. (1988). Om mått- och viktsystemens utveckling i Sverige sedan 1500-talet, Uppsala Pepers in Economic History Research report 16, Department of Economic History, Uppsala universitet. http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A128523&dswid=4370 (last visited 3.2.2023)

- Morell, M. (2011). Subsistence crises during the Ancien and Nouveau Régime in Sweden? An interpretative review. Histoire & Mesure, XXVI(1), 105–134. https://doi.org/10.4000/histoiremesure.4127

- Nelson, M. C. (1988). Bitter bread: The famine in norrbotten 1867–1868. Uppsala University.

- Newby, A. G. (2015). The society of friends and famine relief in Ireland and Finland, c. 1845–57. In P. Fitzgerald & C. Kinealy (Eds.), Irish hunger and migration: Myth, memory and memorialization (pp. 107–119). Quinnipiac University Press.

- Newby, A. G. (2023). Finland’s great famine, 1856-68. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ó Gráda, C., & O’Rourke, K. H. (1997). Migration as disaster relief: Lessons from the great Irish famine. European Review of Economic History, 1(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1361491697000026

- Ó Gráda, C. (2001). Markets and famines: Evidence from nineteenth century Finland. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(3), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1086/452516

- Ó Gráda, C. (2009). Famine: A short history. Princeton University Press.

- Pipping, H. (1961). Från pappersrubel till guldmark: Finlands bank 1811–1877. Finlands bank.

- Pitkänen, K. (1993). Deprivation and disease: Mortality during the great Finnish famine of the 1860s (pp. 14). Publications of the Finnish demographic Society.

- Reese, H. (2017). A lack of resources, information and will: Political aspects of the Finnish crisis of 1867–68. In A. G. Newby (Ed.), “The enormous failure of nature” famine and society in the nineteenth century (pp. 83–102). The Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

- Sadliwala, B. (2021). Fleeing mass starvation: What we (do not) know about the famine–migration nexus. Disasters, 45(2), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12420

- Salmonsson, G., & Spross, L. (2021). Försörjningens förändrade former: Lönearbet och fattigvård under 1800-talet. Arkiv.

- Schön, L. (2012). An economic history of modern Sweden. Routledge.

- Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford University Press.

- Solantie, R. (2012). Ilmasto ja sen määräämät luonnonolot Suomen asutuksen ja maatalouden historiassa [The role of the climate and related nature conditions in the history of the Finnish settlement and agriculture]. University of Jyväskylä.

- Svanberg, I., & Nelson, M. C. (1992). Bone meal porridge, lichen soup, or mushroom bread: Acceptance or rejection of food propaganda in northern Sweden in the 1860s. In A. Häkkinen (Ed.), Just a sack of potatoes? Crisis experiences in European societies, past and present (pp. 119–147). Helsinki.

- Turpeinen, O. (1986). Nälkä vai tauti tappoi? Kauhunvuodet 1866–1868. SHS.

- Utterström, G. (1957). Jordbrukets arbetare. Levnadsvillkor och arbetsliv på landsbygden från frihetstiden till mitten av 1800-talet. Första delen. Tidens Förlag.

- Van Bavel, B. J. P., Curtis, D. R., Dijkman, J., Hannaford, M., De Keyzer, M., Van Onacker, E., Soens, T., (2020). Disasters and history: The vulnerability and resilience of past societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Västerbro, M. (2018). Svälten: hungeråren som formade Sverige. Albert Bonniers förlag.

- Voipaala, H. (2021 [1941). Nälkävuodet 1866–68 Ala-Sääksmäen kihlakunnassa. NTAMO.

- Voutilainen, M. (2016). Poverty, inequality and the Finnish 1860s famine. University of Jyväskylä.

- Wheatcroft, S., & Ó Gráda, C. (2017). The European famines of world wars I and II. In G. Alfani & C. Ó Gráda (Eds.), Famine in European history (pp. 240–268). Cambridge University Press.