?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

During the half-century before World War One (WWI), Sweden was one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, but also one of the most indebted. While the role of foreign capital for public investments during this period is emphasised in previous research, its importance for the funding of Swedish industry is commonly de-emphasised. The conventional view is that since public investments could be financed by foreign money, this relieved pressure from domestic financial markets and made it possible to fund Swedish industry through domestic savings. Using balance sheet data for a large sample of Swedish industrial joint-stock companies in 1908 we show that, while it is true that only a small percentage of Swedish industrial shares were owned from abroad, foreign investments were much more important for new and dynamic industries (e.g. pulp and paper, electromechanics, and chemicals). Companies with foreign-owned shares were also more profitable, and had a much lower risk of bankruptcy over the ensuing decades. In fact, out of the 230 companies with foreign-owned shares in 1908, 103 (45 percent) were still in business fifty years later. This suggests that foreign capital was considerably more important for Swedish industrial development than what is commonly argued.

1. Introduction

The half-century before WWI saw a concomitant rise in income levels, levels of industrialisation, and financial market integration across most of Western Europe and its offshoots, as well as in other parts of the world. Most research indicates that this correlation was causal, and that the increase in foreign capital inflows fulfilled an important role in the development of the newly industrialised countries (Bordo & Meissner, Citation2011; Schularick & Steger, Citation2006). The available research has mainly focused on aggregate capital inflows, the bulk of which went into the funding of state or private infrastructure projects – above all railways, roads and harbours, which likely accounts for a large part of the growth effect of these flows. However, we know a lot less about the growth effects of foreign capital that went into the financing of domestic industry. Available country case studies, however, all tend to show that such flows, while accounting for a relatively small share of the total capital inflows, still had a large impact on the development of a select number of fast-growing industries (e.g. Colli, Citation2014; Strandskov & Pedersen, Citation2008; Wilkins, Citation1991). In this paper, we aim to add to this research by analysing the experiences of a country that was one of the largest capital importers of the time relative to its size, namely Sweden.

On the eve of WWI, Sweden was one of the most indebted countries in the world, in per capita terms (Schön, Citation2012, p. 169). Over the preceding four decades, Swedish real income had grown at an average rate of 1.8 percent per year, faster than almost anywhere else, transforming Sweden from an average economy to one of the richest countries in Europe (Bolt & van Zanden, Citation2020).Footnote1 From the 1890s in particular, the country's economic structure underwent significant changes. Traditional industries, such as wood and textiles, declined while emerging industries, such as pulp and paper and mechanical and electrical engineering, grew in importance. Achieving such an industrial transformation in a sparsely populated, agrarian economy that stretched over 1600 km from north to south required investments on a scale which was wholly incommensurate with the level of domestic savings. From the mid-nineteenth century, Sweden thus turned to the international market for capital. Through a combination of international bond issues, external credit, direct and portfolio investments and remittances, Sweden imported around SEK 3.4 billion in foreign capital between 1850 and 1910. By the end of the period, Sweden had accumulated a foreign debt of SEK 2.8 billion, equivalent to more than 80 percent of the national income (Schön, Citation1989, pp. 230–235; Schön, Citation2012, pp. 175–176).

While the role of this huge influx of capital in the Swedish industrialisation process has been emphasised by numerous researchers, the importance of foreign capital for the financing of Swedish industry has in general been downplayed. The standard view is that foreign capital aided Swedish industrialisation mainly by facilitating the construction of vital infrastructure, thereby relieving some of the pressure on Swedish financial intermediaries, which were thus set free to fund the burgeoning industry through domestic savings (Cameron, Citation1961; Dahmén, Citation1984; Gårdlund, Citation1942; Citation1947; O’Rourke & Williamson, Citation1995). The flows of foreign capital into Swedish industry, it has been argued, was far too small to have made a sizable impact. To this effect, it has been emphasised that contemporary state investigations into the ownership structure of Swedish industry showed that only a small percentage of all industrial shares were in fact owned by foreigners, and it has been stated that the reported figures would have needed to be ‘multiplied several times over in order to become significant’ (Gårdlund, Citation1942, p. 187).

One perspective that has gone missing in previous research is what kind of companies were included in this seemingly modest percentage with foreign-owned shares. Were foreign investments that flowed into Swedish industry distributed randomly across companies, or were there patterns that may lead us to re-evaluate their importance for the Swedish industrialisation process? In this article, we analyse the stock of foreign investment in Swedish industry in the year 1908 using balance sheet data, which covers the debts and assets of most Swedish industrial joint-stock companies in existence that year, and includes information about the portion of the share capital that was owned by foreigners, bonds emitted abroad, as well as foreign loans and foreign assets. We find that, while it is true that only a small percentage of Swedish industrial shares were owned from abroad (around 6 percent), foreign investments were much more important for a smaller number of fast-growing industries that are commonly held to have formed the backbone of the Second Industrial Revolution (e.g. pulp and paper, electromechanics, and chemicals). Secondly, foreign loans contributed to an even larger capital inflow than foreign-owned shares; adding foreign loans more than doubles the share of foreign to total liabilities in Swedish industrial companies. As could be expected, companies with foreign-owned shares took on a disproportionately large portion of these foreign loans. Finally, we show that companies with foreign-owned shares were more profitable, and they were also more likely to survive over the ensuing decades. In fact, out of the 230 companies with foreign-owned shares in 1908, no less than 103 (or 45 percent) were still in business fifty years later (in 1958) and several were among the largest companies in Sweden at that time. We argue that the higher survival probability of companies with foreign-owned shares was most likely due to the fact that foreign investment was associated with transfers of technology, know-how, and other resources that improved the competitiveness of these companies.

2. International capital flows during the second industrial revolution

The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in the international mobility of capital. The stock of foreign-owned assets in the global economy rose quickly from negligible levels in the mid-nineteenth century to seven percent of world GDP in 1870 and continued upwards to just under 20 percent before WWI. According to Schularick (Citation2016), 9 out of the top-12 recipient countries of foreign investment before the outbreak of WWI could be characterised as developing economies. Clemens and Williamson (Citation2004) have furthermore showed that, at least in the case of British capital exports, investors primarily chased after higher returns. The main determinants of British capital flows were economic fundamentals, e.g. natural resource endowment, population growth or education levels, which would mainly have affected the expected profitability of the investments (Clemens & Williamson, Citation2004, pp. 318–324; Obstfeld & Taylor, Citation2004, pp. 49–55; Schularick, Citation2016, pp. 8–16).Footnote2

The combination of large rich-to-poor capital flows chasing after high returns during a period when many new countries joined the industrial club, suggests that the increase in international capital mobility before WWI may have played an important role during the Second Industrial Revolution. There is indeed a strong correlation between catch-up growth and economic convergence during the late 19th and early twentieth century and the available capital inflows data (Clemens & Williamson, Citation2004; Collins & Williamson, Citation2001). Schularick and Steger (Citation2006), and Bordo and Meissner (Citation2011) show that capital inflows had a positive impact on economic growth over the period 1880–1913. Schularick and Steger (Citation2006) attribute the growth effect to a strong association between foreign capital inflows and investments, which is also supported by Esteves and Khoudour-Castéras (Citation2011), who found that pre-WWI capital inflows contributed to domestic financial development (Esteves, Citation2011, pp. 464–465). Bordo and Meissner (Citation2011), however, also highlight the fact that capital inflows raised the probability of experiencing financial crises, thereby increasing income volatility. They furthermore found that the growth effect during non-crisis years was insufficient to fully counteract the negative short-run income shock from crises. In their view, only countries that managed to avoid large-scale financial crises were thus able to reap the benefits of foreign capital inflows.Footnote3

Most research on pre-WWI international capital flows have studied aggregate flows, and since the bulk of international capital went to the financing of government investments in infrastructure, the conventional view has been that foreign capital inflows mainly affected economic growth by enabling and/or speeding up the construction of railroads, harbours and other public works that were necessary for industrialisation. We know considerably less about the portion of foreign capital inflows that went to the funding of domestic industry, in the form of direct or portfolio investments, foreign bank loans or through foreign bond issues. There are no cross-country studies that have examined the growth effects of these flows in a similar manner as for the aggregate flows. There are, however, a number of country case studies available, and all of them have tended to find that such flows, while small in comparison to the aggregate flows, were nevertheless important for the industrialisation process of several countries. For instance, Wilkins (Citation1991) argued that foreign investments in U.S. industry before WWI had a profound impact on American industrialisation because they contributed with more than just the financial capital. Foreign investments also transfered know-how and technology and funded new forms of economic activity. Foreign investments were also heavily influenced by changes in U.S. tariff policy, flowing into protected sectors, thereby aiding U.S. import substitution (Wilkins, Citation1991, pp. 16–20). Jones (Citation1988), and Jones and Bostock (Citation1994) similarly argued that while foreign investment was quite limited in most sectors of British industry before WWI, it was considerably more important for a subset of new, and fast-growing industries, such as chemicals, electrical and electronic engineering and pharmaceuticals (Jones, Citation1988, pp. 445–446; Jones & Bostock, Citation1994, pp. 119–120). Mason (Citation1987) made similar claims for the case of Japan 1899–1931, and emphasised that foreign investors introduced new technology and new modes of business management, which provided an important stimulus for Japanese economic development (Mason, Citation1987, pp. 95–97, 105–106). Strandskov and Pedersen (Citation2008) likewise found that foreign investments in Denmark during the early twentieth century mainly targeted emerging industries, and argued that such investments were essential for later Danish competitiveness in, for instance, electronics (Strandskov & Pedersen, Citation2008, p. 628, 637–640). Colli (Citation2014), finally, showed that in the case of Italy during the late nineteenth and early twentienth centuries, foreign multinationals acted as ‘substitutes for weak, or even absent, domestic entrepreneurship’ (Colli, Citation2014, p. 304) in technology-intensive industries such as chemicals and electromechanics (Colli, Citation2014, pp. 326–327).

Sweden is an interesting case to add to this literature, given that (i) it was one of the largest capital importers of the time in per capita terms, (ii) it was also one of the fastest growing economies, yet (iii) the role of foreign capital in industrial financing has generally been downplayed. In Swedish economic historiography, the critical role of foreign capital inflows for infrastructure development during the country’s industrialisation phase (above all for railroads, harbours and urban dwellings) has been emphasised by numerous researchers, while at the same time, the importance of foreign capital for financing domestic industry has been de-emphasised. O’Rourke and Williamson (Citation1995) argued that foreign capital inflows were indeed an important factor behind the rapid Swedish catch-up during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, but attributed this wholly to its effect on government investments (O’Rourke & Williamson, Citation1995, pp. 180–182). In a study of French foreign investment in 1800–1914, Cameron (Citation1961) similarly argued that Sweden benefitted from foreign capital inflows mainly because foreign capital was used to finance productive government investments in infrastructure (Cameron, Citation1961, pp. 488–494). In regards to the role of foreign capital for industrial companies, the conventional view has been that because Swedish government and municipal investments to a large extent could be financed by foreign money, this relieved pressure from domestic financial markets and made it possible to fund Swedish industry through domestic savings (i.e. foreign capital was important, but only in an indirect sense). The conventional view was perhaps most clearly articulated in Gårdlund (Citation1942; Citation1947). In Gårdlund (Citation1942) it was noted that official surveys showed that foreign ownership of Swedish industry was very limited in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and that the total value of foreign bonds issued by industrial companies was relatively small. Gårdlund (Citation1947) also examined balance sheet data for a sample of 33 Swedish companies before 1913 and found that, in most years, only a small proportion of companies had foreign liabilities, and then usually in small amounts. According to Gårdlund, the amount of foreign capital that went into the financing of industrial companies was therefore far too small to have made a difference. This point has since been reiterated by a number of other researchers (Dahmén, Citation1984, pp. 24–26; Gårdlund, Citation1942, pp. 187–195; Gårdlund, Citation1947, pp. 123–128; O’Rourke & Williamson, Citation1995, p. 181). Schön (Citation1989), however, criticised this view in his study of Swedish capital imports 1850–1910. Using the indirect methodFootnote4, Schön demonstrated that Sweden’s total capital imports were much higher than official figures suggested. He argued that foreign businessmen, merchants and bankers who moved to Sweden during the country’s industrialisation phase were likely to have brought in significant amounts of capital that went unregistered by the authorities (Schön, Citation1989, pp. 232–233). The most comprehensive study of foreign investment in Swedish industry before WWI was conducted by Nordlund (Citation1989). The study revealed that inward FDIFootnote5 in Sweden was considerably more common during this period than what had previously been assumed. Nordlund also analysed the geographical distribution of investor countriesFootnote6, as well as the share of total employment and total manufacturing output held by foreign-owned companies. In 1913, these shares were only 6.9 and 6.1 percent, respectively, but with significant variation across sectors (Nordlund, Citation1989, pp. 58–86). More recently, Broberg (Citation2006) re-affirmed the conventional view in a study of 115 Swedish joint-stock companies that were founded between 1849–1938, stating that ‘the significance [of foreign investments] for the studied companies, as a whole, can hardly be considered as decisive’ (Broberg, Citation2006, pp. 169–170).

In previous research on the role of foreign investments for Swedish industrial companies there has been a very strong emphasis on the absolute volume of the investments, as well as on the question of foreign control over Swedish industry. In large part, this is probably due to the fact that the main source of knowledge about foreign influences in Swedish industry before WWI comes from a series of state investigations that were initiated during the late ninteenth and early twentieth centuries out of concern for undue foreign control over Swedish natural resources (e.g. Fahlbeck, Citation1890; Citation1901; Flodström, Citation1912). In this article, however, we focus not so much on the absolute size of the foreign investment stock, as on the relative importance of foreign investments for select industries. The argument of the article, inspired by previous research on other western countries (e.g. Colli, Citation2014; Jones & Bostock, Citation1994; Strandskov & Pedersen, Citation2008; Wilkins, Citation1991), is that a seemingly small stock of foreign investment may still have been important for the Swedish industrialisation process, if it can be shown that foreign investments tended to finance viable companies in new industries, thereby contributing to the restructuring of the economy.

3. Our data

Our database is based on balance sheets of all joint-stock companies that were active in the Swedish industrial sector in 1908, with exception for the cement industry and the printing industry, for which the records are lost.Footnote7 These were collected using standardised forms from a government investigation that was undertaken by the Swedish Department of Finance in order to assess the wealth of Sweden in 1908 (Flodström, Citation1912). The forms were sent out to all joint-stock companies by the County administrative boards with guarantees that the information would be kept confidential. The forms contain detailed information on the assets and liabilities of each company, such as the value of real estate, machines and stocks in other companies as well as the capital stock, and foreign and domestic debt. When comparing the forms with larger companies published balance sheets for the same year, they match closely, although some categories are different in the companies’ own balance sheets compared to the standardised forms.Footnote8 One problem with the data is, however, that the companies tended to only report profits and only very rarely reported losses.Footnote9 The mean profitability of Swedish industry was thus probably lower in 1908 than our data suggest.

The companies were also obliged to report the amount of the share capital that was held by foreign citizens. This information was based upon the companies’ own records of shareholders,Footnote10 and it is of course possible that stocks may have changed hands without the companies’ knowledge (Flodström, Citation1912, p. 222). However, this would entail that the owner did not use his or her voting rights during the annual general meeting, and thus, did not influence the company in any way. It also seems likely that the companies themselves would have had an incentive to keep track of the ownership of their company.

In order to assess the risk of bankruptcy or liquidation, we have also collected data from the registers of the joint-stock companies that were kept by the Swedish Intellectual Property Office. From these registers, we have collected information about the year the company was founded and the date of liquidation or bankruptcy up until 1925.

Our database thus, with the exceptions mentioned above, contains all 2190 joint-stock companies that were active in the Swedish industrial sector in 1908, their assets, liabilities, profits and information about foreign ownership in that year, as well as their age in 1908 and whether or not they were liquidated or went bankrupt between 1908 and 31st December 1924. As can be seen in , the average joint-stock company was 11.87 years old at the end of 1908, and about 46 percent of the companies would either be liquidated or go bankrupt over the following 16-year period. The rates of liquidation and/or bankruptcy differed markedly between industries. Whereas on the one hand, they were low in the newer and more capital-intensive chemical- and pulp and paper industries, they were, on the other hand, high in the old export-oriented sectors such as mining and metal and the wood industry that were hit hard by the deflationary crisis in 1920–1923 (Magnusson, Citation2002, pp. 367–370).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The average company held about 1.2 million SEK in assets and a share capital of about 0.5 million SEK. However, as is to be expected with this kind of data, the spread is very wide and the averages are somewhat biased upwards due to several very large companies such as Svenska Sockerfabriks AB, Stora Kopparbergs Bergslags AB, and LKAB. In order to say something about the branch distribution of foreign ownership and foreign debt, we have also grouped the data in accordance with the Swedish historical national accounts. In most cases, this was a straightforward process, but in some cases, when a company produced goods related to more than one industrial branch (such as iron works that also had mills or sawmills) we have tried to determine the company’s main business in 1908 using other sources. In some cases, however, this was not possible and the company was placed in the ‘Other industries’ category.

4. The stock of foreign investment in Swedish industry in 1908

Our data on foreign investment in Swedish industry for the year 1908 largely confirms the findings in previous research, with respect to the limited volume of such investments. Out of a total share capital of 1.1 billion SEK only 62 million SEK (or 5.5 percent) was held by foreign investors. These 62 million SEK were, moreover, concentrated to a relatively small number of companies (230). Only a little more than 10 percent of all Swedish companies had foreign-owned shares in this year. Consequently, the average foreign ownership share for these companies was quite high, at 29.3 percent (SD = 36.3). In fact, around half (49.5 percent) of the companies had a foreign ownership share above 10 percent (corresponding to the modern definition of FDI), and ∼28 percent of the companies had a foreign ownership share above 50 percent.Footnote11

In examining the distribution of foreign investment across different industries, our primary objective is to ascertain whether foreign investment was indeed more prevalent in new, as opposed to traditional, industries, as has been the case in previous country case studies. We define new industries as those most commonly associated with the Second Industrial Revolution, i.e. capital- and technology-intensive industries such as Steel, Pulp and paper, Chemicals, and Mechanical and Electrical engineering. Conversely, we define raw material- and labour-intensive industries such as Wood, Textiles and Mining as traditional industries.Footnote12

In absolute terms, the largest recipients of foreign investments in Sweden were the Metal- and mining industry, which accounted for 33 percent of the total foreign-owned share capital in 1908, and the Pulp and paper industry, with 27 percent. The smallest recipients were the Textile- and Leather-, hair and rubber industries, with 3 and 2 percent respectively, while the remaining industries accounted for around ten percent each. The different industries were of very different sizes however, with the Metal- and mining- Food- and Wood industries being the largest (in terms of the number of companies). If we instead look at the relative importance of foreign investments within each industry, a somewhat different picture therefore emerges.

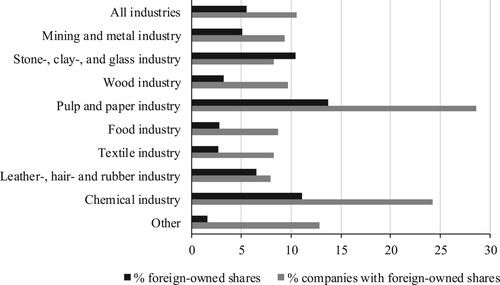

As can be seen in , the relative importance of foreign investments varied considerably across the different industrial branches. While the percentage of foreign-owned shares was around or below the total sample average for most industrial branches, foreign ownership was much more common in the Stone-, clay- and glass- (10.5 percent), Pulp and paper- (13.7 percent) and the Chemical (11.1 percent) industries. In the Stone- clay- and glass industry foreign ownership was concentrated to a relatively small share of all companies (8.3 percent), whereas in the Pulp and paper- and the Chemical industries, the percentage of companies with foreign-owned shares was as high as 28.6 and 24.3 respectively.

Figure 1. Percentage of total share capital owned by foreigners and percentage of companies with foreign-owned shares for different Swedish industrial branches in 1908. Source: Finansstatistiska utredningar 1908 617:1, vol. 62–65.

Pulp and paper and Chemicals were of course new industries, whereas Stone-, clay- and glass was not. The remaining new industries (Steel, Mechanical engineering and Electromechanics) are all included in the Mining and metal industry. If we break down the industrial branches into individual industry groups, it becomes evident that foreign investment played a significant role also in the Electromechanical industry, where 9.1 percent of the total share capital was held by foreign investors and 33.3 percent of all companies had foreign-owned shares. In Steel and Mechanical engineering, on the other hand, foreign investments appear to have been less prevalent.Footnote13 Apart from the Electromechanical industry, only a very limited number of industry groups outside the Stone-, clay- and glass-, Pulp and paper- and Chemical industries had a percentage of foreign-owned shares above the total sample average, and in almost all cases this was mainly driven by one or a few individual companies. So, for instance, within the Food industry, Tobacco factories had 18.6 percent foreign-owned shares, but this was due to only one company (if this company is excluded, the figure drops to 3 percent). Similarly, within the Leather-, hair- and rubber industry, the group Other factories had 36.8 percent foreign-owned shares, but this was fully due to a single company. The only exception was Breweries, where 6.1 percent of the total share capital was held by foreign investors and 17.8 percent of all companies had foreign-owned shares.

Within the chemical industry, which consisted of a very diverse group of companies, large foreign ownership shares were mainly found in the groups Match factories (14.5 percent), Adhesives (19.3 percent) and Other chemical-technical industries (15.8 percent). In the Pulp- and paper industry, the group Combined saw mills and pulp factories had the largest share, at 24 percent, while in the Stone-, clay- and glass industry, the largest shares were found in the groups Glassworks (12.3 percent), Stonemasonry (16.7 percent) and Lime-quarrying (21.2 percent).

Many of the industry groups in which foreign investment was most prevalent were characterised by rapid output growth and dynamism, with some of the fastest TFP growth rates of all Swedish industries in the early twentieth century. This is true especially of Electromechanics, Pulp and paper, Match factories and Other chemicals, but TFP growth was relatively fast also in Quarrying in general (see Prado, Citation2008, pp. 178–186).Footnote14 Breweries and Glassworks were less dynamic industries but were, on the other hand, characterised by relatively high profitability, and were therefore likely seen as attractive investments (see e.g. Häggqvist, Citation2023, p. 19).Footnote15 Stonemasonry finally, was a rapidly expanding industry in Sweden during the early twentieth century, driven both by strong domestic demand and a booming export market. The increasing need to build fortifications, roads, harbours, canals and other buildings across much of Europe gave momentum to the industry, and the low-cost structure of the Swedish granite industry (and of Swedish paving stone in particular) gave it a competitive advantage on above all the German market, but also in e.g. England, Denmark and the Netherlands (Lindberg, Citation1983, pp. 137–141).

While it is no doubt true that foreign investments contributed to a relatively small share of the total liabilities of Swedish industrial companies on aggregate, such investments were obviously much more important for a select number of new and fast-growing industries, similar to what has been found in previous research on other Western countries. Moreover, foreign loans contributed to an even larger capital inflow to Swedish industry than foreign-owned shares and, as could be expected, companies with foreign-owned shares took on a disproportionately large portion of such loans. shows a breakdown of different balance sheet items as percentages of total assets/liabilities for companies with foreign-owned shares and compares this to other companies.Footnote16 As can be seen, foreign loans made up around 6 percent of the total liabilities of companies with foreign-owned shares, as compared to 1 percent for other companies. Foreign bond issues were also more common for these companies (though still only 0.4 percent of total liabilities), as were foreign property and other forms of foreign assets. Companies with foreign-owned shares were also typically older, larger and more profitable than other companies. They operated with less share capital but, on the other hand, had larger funds, making the total level of equity quite similar. They do not appear to have been more capital-intensive than other companies. Nor do they appear to have been more heavily leveraged, rather it was just the structure of debt which differed, with these companies being geared more towards international capital markets. Domestic bond financing was also more important for these companies, but this was most likely related to their larger size.Footnote17

Table 2. Balance sheet composition for companies with and without foreign-owned shares.

Foreign investments were thus largely directed to somewhat older, larger and more profitable companies, which operated in a select number of fast-growing and dynamic industries. These companies, moreover, also took on a disproportionately large share of other foreign liabilities (and assets). While for all companies, foreign liabilities only accounted for just under 6 percent of total liabilities, for companies with foreign-owned shares this figure was 14.7 percent. For a smaller segment of the companies with foreign-owned shares (around 1/5, or 43 companies), foreign liabilities made up over 50 percent of total liabilities.

That foreign investments were mainly directed to older and larger companies is perhaps not so surprising, as companies would most likely have needed to establish some kind of track record in order to attract such investments. It would also, by necessity, have involved companies with an actual need for external funding, and as the sample includes numerous small-scale companies which in many cases would have had a very limited need for external finance, it seems natural that companies with foreign-owned shares were larger than the sample average. It is noteworthy that these companies were also more profitable than the average company. This suggests that foreign investors were able to discriminate between profitable and unprofitable investments (or, alternatively, that foreign ownership conferred a competitive advantage). Granted, comparing company profitability for a single year is precarious, as profits tend to vary substantially from year to year and is also affected by accounting practices. But we can evaluate the successfulness of foreign investments also by looking at company survival, and it turns out that this overwhelmingly corroborates the notion that companies with foreign-owned shares tended to perform better than other companies.

4.1. Foreign investments and company survival

If we want to evaluate the competitiveness and long-term viability of foreign-owned companies, there is no better way than to compare their probability of survival with that of other companies. As Atack (Citation1985) argues, competition ensures that inefficient companies are weeded out over time, leaving only the efficient ones to survive. Survival, in this sense, ‘is the ultimate “market test” of efficiency' (Atack, Citation1985, p. 37).

Foreign ownership may have affected the probability of company survival for a number of reasons. For instance, (i) foreign owners may have been more inclined (and/or better able) to provide support to companies with temporary problems with cash flow, liquidity or solvency than were domestic owners. Alternatively, (ii) foreign ownership may have been associated with transfers of technology, know-how and/or management skills which improved the competitiveness of companies with foreign-owned shares, or (iii) foreign investors may simply have been very proficient in discriminating between good and poor investments. We will return to discuss each of these possibilities in more detail below.

4.2. Empirical strategy

To examine the impact of foreign ownership on company survival, we employ a Cox proportional hazards model. This model estimates the risk of exit of a company based on various covariates, assuming it has survived until time t. More formally, the Cox model can be specified as follows:

where the risk of exit at time t is a function of a baseline hazard function

, which is not specified, and Xi is a vector of covariates, which in our case consists of a number of company characteristics. We measure the survival time of companies in days from 1st January 1909 to 31st December 1924, and exit is defined as a declaration of bankruptcy. One of the main assumptions of the Cox model is that hazard rates are proportional between observations and that this proportionality is maintained over time. We use the standard approach in the literature and employ the Therneau and Grambsch nonproportionality test to test this assumption.Footnote18

Our variable of interest is a dummy variable which takes value 1 if a company had foreign-owned shares in 1908, and zero otherwise. Previous research has identified company age, company size and industry-specific characteristics as the three most important determinants of company survival (Box, Citation2005, pp. 35–38). We therefore control for the (log of) age of companies in 1909 as well as their size (defined as the log of total assets, expressed in mill. SEK), and control for industry-specific factors using industry branch fixed effects.Footnote19 As debt might be correlated with both firm performance (see for example: Campello, Citation2006; Yazdanfar & Öhman, Citation2015) and the level of foreign-owned equity we also include two additional indicator variables: Foreign loans (which takes value 1 if a company had foreign bank loans or had issued foreign bonds, and zero otherwise) and Domestic loans (which takes value 1 if a company had domestic state-, bank- or other loans or had issued domestic bonds, and zero otherwise).

In addition to our baseline specification, we also tested several alternative models to evaluate the robustness of our results. Firstly, bankruptcy was not the only way for companies to exit the market. Only 183 companies (or 8 percent of the sample) went bankrupt during the research period, but an additional 831 companies ceased operations through liquidation. We do not know the reasons why these companies were liquidatedFootnote20, but if we assume that liquidated companies were more often than not genuine business failures, then looking only at bankruptcies could of course bias the results. We therefore performed an additional Cox regression using the same set of explanatory variables as in our baseline specification, but with liquidations as the event of interest. In this regression, the 183 bankruptcies were treated as censored observations. Similarly, in the baseline regression, liquidations were treated as censored observations. However, treating alternative events as censored observations may bias the results for the event of interest (Fine & Gray, Citation1999). We therefore also performed a competing risks regression. In a competing risks regression, it is possible to analyse the risk for an event of primary interest (in this case bankruptcy) while simultaneously controlling for the fact that companies may also exit due to other kinds of events (in this case liquidation). As previous country case studies have typically excluded portfolio investments and focused solely on FDI, we have also conducted an analysis that only considers companies where foreign investments exceeded the standard 10 percent FDI threshold. We furthermore checked if using a linear probability model or a logistic regression model would significantly alter the results. Finally, we utilised the detailed information on all balance sheet items in our database and reanalysed the data by including a large number of additional control variables. All robustness tests produced results consistent with our baseline estimate. Therefore, we focus on the baseline regression in the following section. Results from all robustness tests can be found in the appendix.

4.3. Results

presents the results of the baseline test on the risk of company bankruptcy between 1 January 1909 and 31 December 1924. The data indicates that companies with foreign ownership had a significantly lower risk of bankruptcy during the specified period. In the first column of , we included only the dummy for foreign-owned shares along with industry-fixed effects. The hazard ratio for companies with foreign-owned shares is 0.368, indicating a 63 percent reduced risk compared to other companies. Controlling for the age and size of companies (in column 3) increases the hazard ratio to 0.549, but the effect remains significant at the 1 percent level. In column 5 finally, we also included the dummies for foreign and domestic loans. Having foreign loans increased the risk of bankruptcy (by 87 percent), but on the other hand, so did having domestic loans. There is furthermore no indication that having foreign loans was riskier than having domestic loans; rather, if anything, the opposite appears to have been true. More importantly, controlling for the effect of external financing on the risk of bankruptcy does not substantially affect the hazard ratio for companies with foreign-owned shares (which is measured at 0.48). It thus appears that foreign-owned companies were in fact more viable than other companies, with less than half the risk of going bankrupt.

Table 3. Testing the determinants of bankruptcy, Cox proportional hazards model.

Why, then, does foreign ownership appear to have mattered for company survival (or profitability)? Previous research indicates that foreign investments during this period were primarily motivated by the prospects of achieving higher returns.Footnote21 Therefore, it is unlikely that foreign owners would have been more inclined to aid ailing companies than domestic owners. Foreign ownership, on the other hand, may well have constituted an advantage in its own right for certain companies, e.g. export-competing companies that could have benefitted from foreign contacts and/or better information about important markets. It has also been shown that, in many other countries, foreign investments during this period were accompanied by significant transfers of technology, know-how, and other resources that tended to improve competitiveness (e.g. Colli, Citation2014; Strandskov & Pedersen, Citation2008; Wilkins, Citation1991). Nordlund (Citation1989) also provides numerous examples of technology transfer through FDI in pre-WWI Sweden. The growth of the Swedish Pulp and paper industry, for instance, was largely driven by imports of technology from Great Britain and Norway. The world's first sulphite mill was established in Swedish Bergvik in 1874, financed by a consortium of British investors, and built on a pre-existing British patent (Nordlund, Citation1989, p. 109).Footnote22 Before WWI, the Pulp and paper industries in both Britain and Norway were technologically more advanced than those of Sweden. As a result, many new pulp and paper mills were established in Sweden with the help of British and Norwegian investors and immigrants who brought their technological expertise to take advantage of Sweden's vast forest resources. In the Stone-, clay- and glass industry, German investors played a role similar to that of the British and Norwegians in the Pulp and paper industry, for instance by introducing the mechanical cutting of paving stone and other granite products, which reinforced the ongoing structural rationalisation of the Swedish Stone industry through associated economies of scale. In the Clay industry, it was a Danish immigrant, supported by Danish investors, who introduced the new chamotte (or fireplace brick) method to Sweden. Similarly, in the Chemical industry, foreign investors introduced entirely new production methods to Sweden, for example in paints and varnishes, and in the Electromechanical industry, German investment financed the first domestic production of spun copper wire, an essential product for the emerging Swedish telephone industry (Nordlund, Citation1989, pp. 111–115, 122–129, 133–135, 200–201).

While none of these examples can be used to prove that the higher survival probability of foreign-owned companies was due to technological advantages, they do show that foreign capital inflows were often associated with the transfer of new technology. It is therefore highly likely that many of the 230 foreign-owned companies in our sample benefited from such transfers. Whether this was true for foreign-owned companies in general or only in specific cases is not possible to determine from our data. Alternatively, we would have to imagine that foreign investors were able to successfully discriminate between good and bad investments, and were able to target mostly viable companies with competitive advantages. However, Nordlund (Citation1989) has shown that, at least in the case of FDI, the greenfield mode (setting up production facilities from scratch) was much more common than investment in existing Swedish companies, which makes this explanation less plausible. But whichever explanation one prefers, the fact remains that foreign-owned companies tended to survive longer. Thus, foreign investors either targeted or created successful companies with a high potential for long-term growth and survival.

We were not able to track the companies in our sample beyond 1924 using the archives of the Swedish Intellectual Property Office, but we cross-referenced the names of the 230 foreign-owned companies in our sample with the registry in the publication Svenska aktiebolag for the year 1958. Svenska aktiebolag contains information on all active Swedish joint-stock companies above a certain size threshold (in 1958 the threshold was 200,000 SEK in share capital). We were able to find 103 of the 230 companies in this publication, meaning at least 45 percent of the companies were still in business 50 years later. A great number of these companies belonged at that time to the largest industrial companies in Sweden.Footnote23

5. Conclusions

While it is commonly agreed that foreign capital inflows played an important role for the Swedish industrialisation process of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the importance of foreign capital for the financing of Swedish industry has in general been downplayed. Using balance sheet data for a large sample of Swedish industrial joint-stock companies for the year 1908, we show that while it is true that only a very small percentage of the total share capital of Swedish industrial companies was owned by foreigners, this percentage was much higher for a select number of new and dynamic industries, such as Pulp and paper, Chemicals and Electromechanics. Companies with foreign-owned shares furthermore took on a disproportionately high percentage of the total foreign loans and foreign-issued bonds of Swedish industrial companies, meaning their share of foreign- to total liabilities was more than twice that of the sample average. Companies with foreign-owned shares also tended to be more profitable than other companies, and also ran a much lower risk of going bankrupt or being liquidated over the ensuing decades.

The picture that emerges from our analysis is quite different from the conventional view, which argues that foreign capital inflows were important only for government investment. Not only was foreign investment in Swedish industry much more common in new industries with high TFP growth rates, but it also tended to be directed to (and/or created) competitive companies with high potential for growth, profitability and long-term survival. All in all, this suggests that foreign capital inflows into Swedish industry were much more important for the Swedish industrialisation process than the aggregate figures would suggest.

6. Sources

Riksarkivet Marieberg:

Patent- och registreringsverket Bolagsbyrån

Det alfabetiska aktiebolagsregistret 1897–1924, SE/RA/420209/01/D 2 B, vol. 1-3.

Aktiebolagsregistret, SE/RA/420209/01/D 1 AA, vol. 1-123.

Finansstatistiska utredningar 1908

Finansstatistiska utredningar 1908 617:1, SE/RA/320617/1, vol. 62-65.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Growth rates calculated as regressions of the log of per capita income on time.

2 Esteves (Citation2008, Citation2011) has argued that German and French capital flows were no more politicized at the time than the British, but were mainly determined by expected returns. Nordlund (Citation1989) similarly argued that prior to WWI, inward FDI in Sweden was primarily motivated by the country's abundance of natural resources and inexpensive labor, as well as a rapidly growing domestic consumer market.

3 The ability of countries to avoid financial crises was suggested to have varied with the degree of financial development and the overall credibility of the nation in the eyes of international investors, as well as with the level of foreign currency debt and currency mismatches.

4 The indirect method estimates capital imports by analysing a country's capital account, rather than relying on often incomplete data on actual capital flows.

5 Defined as companies with a foreign ownership share above ten percent and foreign representation on the board of directors.

6 Before 1914, the largest investor countries were Denmark, Norway, Germany and Great Britain (in that order).

7 These companies represented a small share of the total Swedish industrial sector. 6 cement companies and 241 paper and printing companies represented about 3.3 percent of total assets in the industrial sector, see Flodström (Citation1912), and it should be unproblematic that we do not observe these companies. We were also unable to match the names of 95 companies (representing about 4.3 percent of total assets) between the registers of the Swedish Intellectual Property Office and the forms from the Swedish Department of Finance. To enable an analysis of company survival, we have also eliminated 43 companies that were undergoing liquidation or bankruptcy in the year 1908 from the sample.

8 We have compared the data in the forms with balance sheets from the Historical Annual Reports Archive from the Swedish House of Finance data center. The archive contains the annual reports of all companies that were listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange during the period 1912 to 1978.

9 Out of more than 2000 companies, only three reported losses, which leads us to believe that our data on profits is, in many cases, censored at zero.

10 A joint-stock company was required by law to keep a register of all stock holders in the company, and to register changes in ownership. See SFS 1895:65 §47.

11 In the following, we do not differentiate between foreign direct- and portfolio investments, as is done in e.g. Nordlund (Citation1989) or Strandskov and Pedersen (Citation2008), but rather analyze the whole foreign investment stock. The reason is that we do not have information about the composition of the companies’ board of directors, and are thus unable to confidently say whether a given foreign investment represented a controlling stake in a company. We have, however, rerun the following analyses looking only at foreign investments that were ≥ 10 percent of companies share capital, to ensure that our results are not sensitive to this choice (see the appendix). Our data also do not allow us to distinguish between greenfield and other modes of investment. According to Nordlund (Citation1989), foreign investors in Sweden commonly started entirely new companies, while investments in already existing Swedish companies were rare. However, since we also include portfolio investments, the distribution of different modes of investment is likely more mixed in our dataset.

12 Our definition is thus similar to that in Colli (Citation2014) or Strandskov and Pedersen (Citation2008). With the exception of Steel, these new industries were also the most important in the industrial transformation of the Swedish economy before WWI. Mechanical engineering and Pulp and paper in particular formed the backbone of the Swedish industrialization. Chemicals and Electromechanics on the other hand, were smaller but nonetheless important carrier industries with widespread applications in other industries. See Schön (Citation2012), pp. 127–143; Persarvet (Citation2019), pp. 61–66.

13 Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to separate Mechanical engineering from Foundries and Shipbuilding, but even with this caveat, foreign investment is unlikely to have been important in financing this industry, as the percentage of foreign-owned share capital for the group as a whole was only 1.6 percent.

14 Limestone was, of course, also an important input in the production of cement, which was yet another of the more fast-growing and dynamic Swedish industries at the time. Unfortunately, we are missing Cement factories in our dataset, so we are not able to say anything about the role of foreign investments in this particular industry.

15 Foreign investments in these two industries may furthermore have been connected. According to Nordlund (Citation1989) Norwegian and Danish breweries invested in Swedish glassworks to expand their production of beer bottles, both for domestic use and for export to the British market (pp. 218–219).

16 In , we only present variables for which there was a statistically significant difference between companies with foreign-owned shares and other companies. To test for significant within-industry differences in age and size, we regressed the natural logarithm (to correct for skewness) of age and total assets on a dummy for foreign-owned shares along with industry branch fixed effects. In the case of return on assets (roa), we used a tobit regression, to account for the fact that negative earnings were rarely reported. To enable this analysis, we imputed zero values for roa in the case of the three companies that reported losses (see footnote 32). Since all of the remaining variables are ratios, and several of them had mass points at zero, we used fractional regression (as recommended by Papke & Wooldridge, Citation1996) to test for significant differences.

17 As is evident from the table, the difference in size was quite striking, with the average company with foreign-owned shares being more than four times as large as the average for other companies. In fact, out of the 100 largest companies in the sample (in terms of total assets) 40 had foreign-owned shares. Furthermore, 140 out of the total 230 companies with foreign-owned shares (or ∼60 percent) could be found in the top size quartile, whereas only 6 (or ∼3 percent) were in the bottom size quartile.

18 This test may also identify a variety of specification errors. See Keele (Citation2010).

19 In four of the industrial branches no company with foreign-owned shares went bankrupt during the period 1909-1924, which necessitated merging some of the industry branches. The Pulp and paper industry was therefore merged with the Wood industry, the Textile industry with the Food industry and the Leather-, hair- and rubber- and Other industries were merged with the Stone-, clay- and glass industry.

20 The reasons for the liquidation of these 831 companies could have been due to a variety of factors, such as the death of the owner, unsatisfactory profitability, mergers, or acquisitions. However, unlike bankrupted companies, these companies were able to repay all of their debts. This group likely consisted of both failed companies that exited due to losses and limited prospects for recovery, as well as successful companies that were acquired or merged with other companies.

21 See footnote 2.

22 The sulfite pulping method is sometimes attributed to the Swedish chemist C.D. Ekman, but his contribution was likely marginal. See Valeur (Citation2007), pp. 144–146.

23 E.g. pulp and paper companies such as Stora Kopparbergs Bergslags AB and Korsnäs AB, chemical companies such as Nitroglycerin AB, AB Barnängens Tekniska Fabrik and Liljeholmens Stearinfabriks AB, and mechanical- and electromechanical engineering companies such as AB Bofors-Gullspång, AB Separator and Allmänna Svenska Elektriska AB.

References

- Atack, J. (1985). Industrial structure and the emergence of the modern industrial corporation. Explorations in Economic History, 22(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4983(85)90020-8

- Bolt, J., & van Zanden, J. L. (2020). The Maddison project: Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update. Maddison-Project Working Paper, 15.

- Bordo, M. D., & Meissner, C. M. (2011). Foreign capital, financial crises and incomes in the first era of globalization. European Review of Economic History, 15(1), 61–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1361491610000158

- Box, M. (2005). New venture, survival, growth. continuance, termination and growth of business firms and business populations in Sweden during the twentieth century. Stockholm Studies in Economic History. 48.

- Broberg, O. (2006). Konsten att skapa pengar: aktiebolagens genombrott och finansiell modernisering kring sekelskiftet 1900. Ekonomisk-historiska institutionen, Göteborgs universitet.

- Cameron, R. E. (1961). France and the economic development of Europe 1800-1914. Princeton University Press.

- Campello, M. (2006). Debt financing: Does it boost or hurt firm performance in product markets? Journal of Financial Economics, 82(1), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.04.001

- Clemens, M. A., & Williamson, J. G. (2004). Wealth bias in the first global capital market boom, 1870-1913. The Economic Journal, 114(495), 304–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00211.x

- Colli, A. (2014). Multinationals and economic development in Italy during the twentieth century. Business History Review, 88(2), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000768051400004X

- Collins, W. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2001). Capital-goods prices and investment, 1870-1950. The Journal of Economic History, 61(1), 59–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050701025049

- Dahmén, E. (1984). Varifrån kom kapitalet? In E. Stavenow-Hidemark (Ed.), Fataburen – Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok (pp. 23–28). Bohuslänningens boktryckeri.

- Esteves, R. (2008). Between imperialism and capitalism. European capital exports before 1914. Economic History Society Working Papers, No. 8022.

- Esteves, R. (2011). The belle epoque of international finance. French capital exports, 1880-1914. Economics Series Working Papers, No. 534.

- Fahlbeck, P. E. (1890). Sveriges nationalförmögenhet, dess storlek och tillväxt. Norstedt.

- Fahlbeck, P. E. (1901). Öfversikt af Sveriges näringar. In G. Sundbärg (Ed.), Sveriges land och folk: historisk-statistisk handbok (pp. 445–457). Norstedt.

- Fine, J. P., & Gray, R. J. (1999). A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(446), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144

- Flodström, I. (1912). Sveriges nationalförmögenhet omkring år 1908 och dess utveckling sedan midten av 1880-talet. Finansdepartementet.

- Gårdlund, T. (1942). Industrialismens samhälle. Tidens förlag.

- Gårdlund, T. (1947). Svensk industrifinansiering under genombrottsskedet. Svenska bankföreningen.

- Häggqvist, H. (2023). Production and profitability in Swedish breweries, 1924-1950. Revista de Historia Industrial — Industrial History Review, 32(88), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1344/rhiihr.40772

- Jones, G. (1988). Foreign multinationals and British industry before 1945. The Economic History Review, 41(3), 429–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.1988.tb00474.x

- Jones, G., & Bostock, F. (1994). Foreign multinationals in British manufacturing, 1850-1962. Business History, 36(1), 89–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076799400000005

- Keele, L. (2010). Proportionally difficult: Testing for nonproportional hazards in Cox models. Political Analysis, 18(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp044

- Lindberg, A. (1983). Småstat mot stormakt – Beslutssystemet vid tillkomsten av 1911 års svensk-tyska handels – och sjöfartstraktat. Liber/Glerup.

- Lobell, H. (2010). Foreign exchange rates 1804-1914. Exchange rates, prices, and wages, 1277-2008. (291-339).

- Magnusson, L. (2002). Sveriges ekonomiska historia. Prisma.

- Mason, M. (1987). Foreign direct investment and Japanese economic development, 1899-1931. Business and Economic History, Vol. 16, Papers presented at the Thirty-Third Annual Meeting of the Business History Conference, pp. 93–107.

- Nordlund, S. (1989). Upptäckten av Sverige – Utländska direktinvesteringar i Sverige 1895-1945. Umeå.

- Obstfeld, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2004). Global capital markets: Integration, crisis, and growth. Cambridge University Press.

- O’Rourke, K. H., & Williamson, J. G. (1995). Open economy forces and late nineteenth century Swedish catch-up. A quantitative accounting. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 43(2), 171–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.1995.10415900

- Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996). Methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (K) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(6), 619–632. https://doi .org/10 .1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199611)11:6 < 619::AID-JAE418 > 3.0.CO;2-1

- Persarvet, V. (2019). Tariffs, trade, and economic growth in Sweden 1858-1913. 119. Uppsala Studies in Economic History.

- Prado, S. (2008). Aspiring to a higher rank: Swedish factor prices and productivity in international perspective 1860-1950. Ekonomisk-historiska institutionen, Göteborgs universitet.

- Schön, L. (1989). Kapitalimport, kreditmarknad och industrialisering 1850-1910. In E. Dahmén (Ed.), Upplåning och utveckling – Riksgäldskontoret 1789-1989 (pp. 227–273). Norstedt.

- Schön, L. (2012). An economic history of modern Sweden. Routledge.

- Schularick, M. (2016). International capital flows. In Y. Cassis, C. R. Schenk, & R.S. Grossman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of banking and financial history. Oxford University Press.

- Schularick, M., & Steger, T. M. (2006). Does financial integration spur economic growth? New evidence from the first era of financial globalization. CESIFO Working Paper No. 1691.

- Strandskov, J., & Pedersen, K. (2008). Foreign direct investment into Denmark before 1939: Patterns and Scandinavian contrasts. Business History, 50(5), 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802246053

- Valeur, C. (2007). Papper och massa i Hälsingland och Gästrikland: från handpappersbruk till processindustri. Skogsindustrierna.

- Wilkins, M. (1991). Foreign investment in the U.S. economy before 1914. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 516(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716291516001002

- Yazdanfar, D., & Öhman, P. (2015). Debt financing and firm performance: An empirical study based on Swedish data. The Journal of Risk Finance, 16(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-06-2014-0085

Appendix

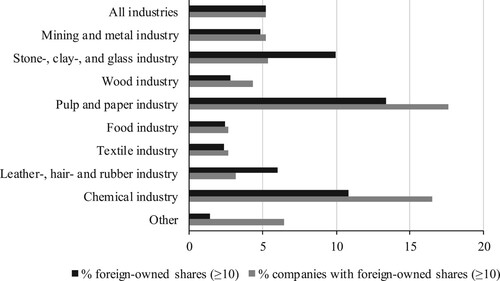

Figure A1. Percentage of total share capital owned ≥ 10 percent by foreigners and percentage of companies with ≥ 10 percent foreign-owned shares for different Swedish industrial branches in 1908. Source: Finansstatistiska utredningar 1908 617:1, vol. 62–65.

Table A1. Testing the determinants of liquidation, Cox proportional hazards model.

Table A2. Testing the determinants of bankruptcy using a competing risk model.

Table A3. Balance sheet composition for companies with and without ≥10 percent foreign-owned shares.

Table A4. Tests of company survival, including a dummy for companies with ≥ 10 percent foreign-owned shares.

Table A5. Testing the determinants of bankruptcy using a logistic regression.

Table A6. Testing the determinants of bankruptcy using a linear probability model.

Table A7. Testing the determinants of bankruptcy with additional control variables.

Table A8. Tests of company survival (Bankruptcy), with dummy variables for different levels of foreign owned shares.

Table A9. Tests of company survival (Liquidation), with dummy variables for different levels of foreign owned shares.