ABSTRACT

In 1948, the social democratic government of Sweden imposed new wealth transfer taxes including an estate tax. Events have been characterised as the definite breakdown of the co-operation between social democracy and organised business. This article attacks the topic from the perspective of the reproduction of the business elite through the inheritance and the gift. The tax reform triggered an epidemic of generosity. In 1947, gift tax revenue was 20 times higher than the annual averages before and after. We have studied the individual actors of the Swedish business elite as donors and concluded that 76 couples of the business elite transferred 25.2 msek to above all their children. The joint political campaign of organised business against the reform raised 24.8 msek. The result complicates and questions previous assumptions concerning the motives of the business elite for protesting against the tax reform.

1. Introduction

In 1946–1947, one of the fiercest political debates in Sweden during the twentieth century occurred. It has been characterised by Söderpalm (Citation1976) and Stenlås (Citation1998) as the definite breakdown of the existing co-operation between social democracy and organised business. It concerned the new taxes proposed by Ernst Wigforss, minister of finance. The proposed taxes included increased taxes on wealth and transfers of wealth. A particular novelty was an estate tax based on the total wealth of a deceased person, whereas the inheritance tax was imposed on each heir. All in all, the estate tax together with the increased inheritance tax and the increased tax on wealth and gifts, were aimed to create a more fine-meshed net of wealth and wealth transfer taxes (Elvander, Citation1972). The proposal immediately provoked strong reactions from organisations representing industry and the employers. It was seen as a threat to power of initiative, to production and to the formation and accumulation of capital (Söderpalm, Citation1976, p. 139). In short, industry representatives feared losing control over industrial development. Instead of direct socialisation, power would be lost through loss of capital to such an extent that socialisation would occur indirectly. This campaign was part of what is known in Sweden as the PHM (sw. ‘planhushållningsmotstånd’), the ‘planned economy resistance movement’ (Lewin, Citation1967).

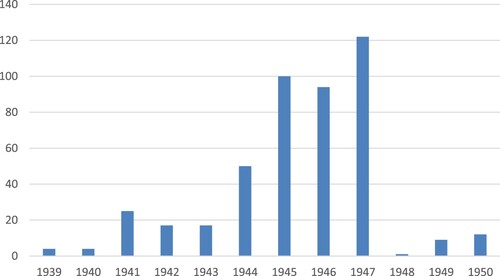

The battle between Sweden’s business elite and social democracy over the new tax system has been extensively covered by previous research. The topic of this article is instead the silent and less overt protest of strategic generosity, resulting from the possibility to pay the existing, and in comparison to what was to come, lower, tax. When the postwar program of the Swedish labour movement became public in 1944, an epidemic of generosity started that abated somewhat in the beginning of 1946, but then escalated all through the autumn of 1946, when the tax proposal became public, and even more so in 1947. When the proposal was debated in parliament in April 1947, generosity knew no boundaries. When the bill was passed and it became known that the new taxes would exist from 1 January 1948, the steady flow of gift giving increased to a crescendo (Ohlsson, Citation2011). For example, between Christmas and New Year’s Eve in 1947, 1545 gift tax returns were filed at the country administrative board of the city of Stockholm. The corresponding figure for 1944 was 106.Footnote1

The men who planned, funded and carried out the overt protests against planned economy in the 1940s, how did they, and, we must stress, their spouses act when it came to their own personal wealth? In this paper, we have investigated the gifts of the business elite during the gift explosion based on a large and unique source material, registers of filed gift tax returns. The main purpose is to shed new light on the overt political campaigns of big business through a study of the reproductive and dynastic strategies of personal giving.

The reform of 1947 offers a unique possibility to study a part of the transition from a historical situation which gave the business elite great leeway in disposing of their wealth, to a historical situation in which this leeway was curbed. The exact date for this transition is 1 January 1948. It is the most considerable tax reform in Swedish twentieth century history. The exact point in time in combination with a source material that has not previously been studied constitute the basis of a so-called natural experiment. By this we mean that actors can be observed before and after the tax reform to track down changes in behaviour.

Our assumption has been that the political, social and economic reproduction of the business elite would be a central motive for its actions during the battle against the new taxes. We ask two questions:

Given that men and women of the business elite did give away their resources, who were the recipients?

What were the motives for and the rationality behind the gifts?

Our main result is that 95.9% of the total gifts of the business elite were given to direct heirs. But, they were not given in equal amounts. All in all, daughters received larger gifts than sons. We have also come to the conclusion that the donorship of the Swedish business elite is closely correlated to their political activities to counteract the 1947 tax reform. Businessmen, together with their wives, counteracted the effects the reform would have on their personal finances and those of their families. Resources were during the gift explosion often transferred in a form that allowed the donor to keep the control over the resources: the promissory note. The private and silent crescendo of gifts in 1947 tells a tale of the reproduction of families within the business elite.

2. Reproducing an elite: the gift, the inheritance and political power over them

Research on business elites has claimed that exchange based on the gift is a central institution holding business elites together through the reproduction of social ties (Marceau, Citation1989; Stenlås, Citation1998; Useem, Citation1984). In fact, Swedish historian Niklas Stenlås (Citation1998) shows that the informal rules of giving in the business elite were central in gathering funds for the resistance to the social democratic reforms. The social pressure to make contributions from business profits was strong. Garantistiftelsen 1946 U.P.A was the organisation into which the business elite channelled their support for the resistance against the tax reform. Its aim was to support the non-socialist parties but also for example the Taxpayers’ Association. The ultimate aim was to oust the socialist government from power. Westerberg (Citation2020) has studied the anatomy of its activities and its expenses. Garantistiftelsen was founded not with family fortunes, but with money emanating directly from shareholding companies. Decisions to partake were taken by the same men that we have seen giving away their private fortunes. Discretion was demanded, contributions were not to be mentioned in board reports. The aim of the foundation was according to Westerberg (Citation2020, p. 109, 119) to raise 40 msek. In the end it had to settle for a little less than 25 msek, of which 17.6 msek were actually spent. The rest of the money was guaranteed, but guarantees were never called. One of the major arguments for making contributions to Garantistiftelsen was that the reform would make giving impossible in the future, thus, it was better to give money away now, for in the future they would be confiscated. Giving was thus a central aspect of the resistance. The freedom to give away money to whatever cause deemed worthy or as a means of reproducing your family and your position, was one of the freedoms fought over.

Stenlås (Citation1998) has concluded that the group leading the resistance did not coincide with the principal interest organisations or emanate from them, but that it was a loosely formed network, an inner circle with no stable or formalised boundaries. The actors acted as persons and there was no separation between their private sphere and their public missions or professional roles. This conclusion led Stenlås to include the wives of the men of the business elite in the investigation, as hostesses and as holders of social capital – for some of them were born into the business elite and held considerable wealth as well as were major owners and managers of industry.

Westerberg (Citation2020, pp. 1–2) instead firmly takes an organisational standpoint, where the publicly stated motives of defending free enterprise (as defined by Hayek and Friedman) become the driving force and the rationale of the political actions of business organisations. He explicitly leaves out the private sphere of the businessman from the investigation. The businessman acts, according to Westerberg (Citation2020, p. 18) as a manager or as a member of an interest organisation, but not as an owner of wealth, as a member of a family, or as a friend. Neither does the businessman act out of class interest or as a representative of a social group. The presuppositions of Westerberg consequently leaves out all private or semi-private motives for political action, as well as making the links between inheritance, donorship, wealth, class reproduction and political action invisible.

The difference between our perspective and that of Westerberg is that we, like Stenlås (Citation1998) assume that the reproduction of families and class position is interrelated with the political actions of the business elite as well as with business itself. The interrelationship of families and business itself is, however, not the topic of this investigation and we will not dwell on it further. It suffices to say that numerous studies on European business elites and on the family firm 1800–1940 for more than 30 years now have demonstrated the centrality of the connection (Augustine, Citation1994; Berghoff, Citation2013; Colli et al., Citation2013; Davidoff & Hall, Citation1987; Hasselberg & Petersson, Citation2006; Jones, Citation1987; Jones & Rose, Citation1993; Rose, Citation1999.)

The nineteenth century is in Europe generally a period of transition of power and resources from one social group to another, namely from the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie, of which the business elite could be assumed to be a part. The social composition of the new elite group was much the same in France, Britain and Germany: its social origin was primarily the old ‘third estate’ – shopkeepers, tradesmen, artisans and industrialists (Gill, Citation2008, pp. 22–33). But in other respects, this development is not uniform, it has national traits. Bengtsson (Citation2019) has correctly pointed out that there is a questionable tendency to interpret modernisation processes in terms of national trajectories. But still, national traits do exist. A central aspect of the formation and reproduction of the new elite is access to political representation and political power. As stated in the introduction, the gift explosion was the consequence of a political decision that led to a countermovement from Swedish business. A key to understanding this is the lack of direct political influence of business interest after the democratic breakthrough.

In Sweden, the four estate parliament survived until 1866. The industrialists did get two (2) seats of their own in 1830 but generally the modern industrial bourgeoisie lacked political representation as until 1858 one had to be a burger (an artisan or a tradesman) in the traditional sense to belong to the third estate. Three reforms of the 1860s changed the situation radically: the municipal reform of 1862, the introduction of county councils in the same year and the two chamber parliament in 1866. The new county councils, to which the votes were limited by wealth and income, were given the task of electing the first chamber of parliament. In the new municipalities, voting power was also based on wealth and income according to the so-called ‘fyrk system’. A higher number of ‘fyrks’ gave a person more votes, and corporations were included in the system. Suddenly, local and regional power along with a direct influence on the composition of the first chamber of parliament was in some geographical areas handed over to the emerging industries such as sawmills and their owners (Nydahl, Citation2010). The age of undisputed and direct political power of the Swedish industrialists is limited to the period before 1920, when the fyrk system was abolished and general suffrage introduced. Sweden’s relatively late industrialisation also lies within this period and it is a period of capitalisation and building of fortunes (Ohlsson et al., Citation2020).

Thus the late nineteenth century is clearly a period of bourgeois elite formation in Sweden, even though Norrby (Citation2005) has stressed the adaptability and entrepreneurship of the late nineteenth century Swedish nobility. The formation of business interest organisations in Sweden, reflecting organised capitalism, takes place in anticipation of the democratic breakthrough, between 1898 (the Swedish Employers’ Confederation) and 1909 (the Federation of Swedish Industries). Swedish sociologist Göran Therborn (Citation1989) claimed that the democratisation then leads to the emergence of a new political elite with its roots in the popular movements. He claims that in Sweden the period after WW1 has been two-pronged with a division of power between an economic elite and a political elite, of different outlook and social composition. The tax reform of 1947 and the political battles surrounding it can be seen in this light: as a battle between the economic and the political elite.

In a European perspective, Swedish business elite organisation has similarities with its German counterpart. However, German industrialists did not have the late nineteenth-century golden age of political influence. A by now classical perspective of the German ‘sonderweg’ leading up to Nazism is the conclusion of Hans-Ulrich Wehler and the Bielefeld school (Wehler, Citation1995) that the German ‘bürgerlichkeit’ never managed at all to wrench the political power from the not particularly liberal ‘junkers’, the landed gentry. In Germany, unlike in Britain and France, nation building and economic modernisation were led by the old Prussian rural elite. It was characterised by reactionary traditionalism, not a bourgeois revolution, not division of power and co-optation and certainly not gradual democratisation. In France, the political influence and representation of business interest in parliament and government date from the July Monarchy, but were fairly limited compared to the situation in Britain and the USA (Gill, Citation2008, chapter 4). In Britain, the ascent to political power of the liberal party, supported by the industrialists and middle class, took place in 1832. In terms of representation in government, there was a breakthrough for the economic middle class in the mid-1860s (Gill, Citation2008, p. 118). The German business interest instead compensated its lack of direct political power with activity in business interest organisations (Gill, Citation2008, pp. 138–139) that were much stronger than their British and French counterparts. The structure and anatomy of the new European elites, as well as their power resources, vary enormously between different European nation states.

Let us then move to the economic reproduction of bourgeois elites. How has wealth been transferred and families reproduced? The obvious answer to this question is that it is inherited. Inheritance perpetuates inequality across generations and in general reproduces elites (Keister et al., Citation2019; Mills, Citation1956; Ohlsson et al., Citation2020; Piketty & Zucman, Citation2015; Thurow, Citation1976). Inheritance law during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in France, Germany and the USA, according to Jens Beckert (Citation2007 and Citation2008), became a prime social concern from a republican and individualist standpoint. Legal regulation of bequests was then formed and has changed relatively little since. A comparison shows that it was meant to fulfil different moral and societal goals in different countries. The unlimited disposal of wealth by testators has been opposed (Beckert, Citation2007, p. 80), but similarities stop there. In the USA and Britain, the individual freedom of the testator and the meritocratic critique against inherited wealth shaped the law, while in France the state took upon itself to enforce equality between direct heirs and in the process limited the freedom of the testator. German inheritance law eliminated this freedom almost entirely, not recognising the institution of the last will but automatically bequeathing property according to line of succession. The reproduction of the family was more central in the German legal tradition and in this respect Swedish law resembles German law.

In Sweden, a testator with direct heirs has never been free to dispose of his/her property, and when the first modern inheritance law was passed in 1845, granting women the same rights to inherit as men, this rule was kept intact. Since 1857, there exists a legal share system including all direct heirs of a testator, granting the right of the testator to bequeath up to half of the estate to other persons than direct heirs. The existence of a last will was and still is today exceptional in Sweden and the absolute majority of all estates (78%) are divided according to the order of succession. Also, in the cases where a will exists and there is more than one direct heir, 84% of the estates are today divided equal (Erixson & Ohlsson, Citation2015). In practice, inherited wealth is still in Sweden treated as something belonging to the family, not the individual testator. This leads us to expect that the act of giving is also prone to be treated as a family matter, because, as we will demonstrate, the gift and the inheritance have strong interlinks.

There are historical case studies regarding inheritance practices of the bourgeoisie in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and regarding Britain we have plenty of evidence. Thompson (Citation1994) concluded that the British economic bourgeoisie differed from the aristocracy in that it distributed the inheritance more fairly, though still primarily between sons. Davidoff and Hall (Citation1987, p. 206) found that the middle class in Birmingham favoured partible inheritance and that children of both sexes inherited roughly equal shares. Mackie (Citation2022), in a recent study of businessmen in Scotland, however finds that sons inherited the family firm and that in no case it was left to a daughter. Daughters were given other types of property and sometimes a smaller inheritance. Mackie finds that had the testator more than one surviving child, the shares were absolutely equal in less than half of the cases.

We know of no large-scale historical studies of inheritance patterns of classes/social groups based on micro data. Data collections would simply be too laborious. But it seems safe to assume from aggregated data that the economic reproduction of the bourgeoisie did greatly rely on inheritance in this period, although to a lesser extent after 1910. Piketty and Zucman (Citation2015) demonstrate for France, Britain (based on Atkinson), Germany (based on Schinke) and Sweden (based on Ohlsson et al., Citation2020) that inherited wealth as share of aggregated wealth begins to fall after 1910. It fell from between a little more than 60% in Germany and almost 80% in France, the UK and Sweden (1910), to between 45% in Sweden and almost 70% in France in 1950 (Piketty & Zucman, Citation2015, pp. 1340–1341). In the same countries, the inherited wealth to aggregated wealth ratio roughly follows the private wealth to income ratio during the period 1870–2010, falling steeply after 1910, reaching its low in 1950–1980 and then rising again (Ohlsson et al., Citation2020 Piketty & Zucman, Citation2015). When inequality decreases, so does inherited wealth. When inequality increases again, so does inherited wealth.

Having come this far, a conclusion can be reached regarding the combined conditions for political and economic reproduction of the Swedish business elite around 1950. Sweden was, as has been demonstrated by Bengtsson (Citation2019), very unequal before the democratic breakthrough, both politically and economically. The share of inherited wealth started to fall already during WW1, in accordance with the international trend. But peculiar to Sweden, democracy in general and the Social democratic ascendancy after 1932 in particular, led to loss of political power for the business elite which in turn made the conditions for the economic reproduction even more difficult. Our hypothesis is that this is reflected in the gift explosion, as the only way to avoid the new taxes for the business elite would have been to find other ways of transferring wealth than through inheritance, namely through inter vivos gifts.

The strong link between inheritance and the gift is central to this study. In terms of gifts, the wealth taxation system in many OECD countries (Belgium, Finland, France, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, UK and the US, see OECD, Citation2021) and previously in Sweden (before the repeal of the inheritance and gift taxes in 2004) have integrated the inter vivos gift and the inheritance, so as to eliminate the time aspect of giving. Inter vivos gifts do not give an opportunity to avoid inheritance tax. The assumption that inter vivos gifts also contribute to the economic reproduction of elites is strong. Albertini and Radl (Citation2012) have demonstrated substantial class differences in wealth transfers, with the propensity to give unsurprisingly being higher in white collar occupations than in the working class. However, it must also be stated that a more general conclusion regarding donorship in the twentieth century, drawn by Thurow (Citation1976), Poterba (Citation2001) and Schmalbeck (Citation2001) is that prospective donors prefer to keep their money as long as possible, largely for reasons of control. Weisbach (Citation2002) has demonstrated that giving to ones heirs as a tax shelter is not utilised to the extent that would be rational in a purely economic sense. Thus from the existing literature one could advance the hypothesis that the Swedish bourgeoisie in general and the business elite in particular would have a higher propensity to give money to their offspring than other social groups, but that they still would avoid doing so when not strictly motivated. Also, as stated previously, one would expect that the act of giving away a fortune expected to be inherited by relatives, to non-relatives, would be more or less tabu.

Husz (Citation2013) and Gustavsson et al. (Citation2009, p. 89) discuss the cultural meaning of wealth in the Stockholm bourgeoisie 1915–1965 and conclude that keeping the fortune intact had a cultural value and an importance for the identity. All inroads on the wealth amassed were a threat eventually leading to economic and cultural decline. This way of reasoning would also hold for gifts to heirs, as it would be impossible to control that the gifts were not used for consumption. Gustavsson, Husz and Söderberg (ibid.) investigate the development of wealth in the Stockholm bourgeoisie during the period and conclude that the mean wealth declined strongly before 1945, as a consequence of the Depression and WW2. This would explain the worries of the interwar period concerning bourgeois decline. Our hypothesis is that it was intensified by the lessened direct political influence after 1920, the pronounced political target of economic planning and redistribution of social democracy after 1932 and no doubt also reflecting the decrease in inherited wealth discussed above. The sample in this study is fairly large, it consists of almost 37,000 wealthy Stockholm households. Therborn (Citation1989) examines a much smaller Swedish elite group, holding fortunes above 8.5 million SEK in 1927, closer to our empirical sample but not identical with it. His result is that the very wealthy families become fewer but also wealthier in the period 1914–1927. Bengtsson and Molinder (Citation2021), based on data from two elite areas in greater Stockholm, study the composition of the income elite. They show (p. 16) that the incomes of the capital rich top 0.1% declined relatively less 1909–1950 compared to incomes of the others in the top percentile group, which declined even more steeply. They conclude that there was, during the first part of their period, a marked difference between the entrepreneurial nature of the very top incomes and the incomes of wealthy professionals. The very top incomes depended on the globalised market economy and were later greatly affected by regulation and unionisation. Their result is consistent with Therborn’s, but also with the result of Gustavsson, Husz and Söderberg, who’s larger sample in all likelihood contains a large number of wealthy professionals. All in all it seems that the composition of the economic elite is a crucial issue, but also that the movement in and out of the top percentile group is of great importance if one wants to really understand historical change.

Let us now return to the questions we asked in the introduction. With the existing knowledge on the reproduction elite groups as a starting point, we would like to launch two hypotheses regarding the gifts of the Swedish business elite.

Our first hypothesis is that the recipients of their gifts will prove to be direct descendants in equal shares, thus the gifts will prove to have a dynastic function and be directly linked to the change in inheritance taxation.

Our second hypothesis is that the results will in total point to a more complex rationale of the planned economy resistance movement than the aim of defending free enterprise, namely a rationale that concerns the reproduction of the business elite.

3. The anatomy of the sources

The sources of this study are (i) the registers of filed gifts kept by the county administrative boards (CAB) of the counties of Jämtland, Jönköping, Kopparberg, Kronoberg, Norrbotten and Uppsala 1942–1950 and (ii) the regional court archives that include all gift tax returns filed in the city of Stockholm and the counties of Stockholm and Gotland during the studied period. It is of course important to note that gifts that have not been reported, by negligence or tax avoidance, are not included in the investigation.

The counties included overall reflect a representative Swedish average in terms of social composition and economic structure. This is mirrored by types of donors and recipients, as well as the size of gifts. The academic town of Uppsala was dominated by the university but Uppsala county also held some major landowners. The counties of Gotland, Jämtland, Jönköping, Kopparberg, Kronoberg and Norrbotten were more rural, and gifts were significantly smaller. Norrbotten also held the regiments of Boden, and a substantial share of the recipients were officers. A comparison of the city of Stockholm and the eight counties with Sweden at large, in terms of the composition of the economy, can be found in .

Table 1. The population classified after industry 31 December 1940 according to the census data, percent.

The regional court archives of the city of Stockholm are in many ways a more central source than the other country registers, since gifts were much more numerous and the average gift was larger. A problem in the composition of the material is that complete registers from the major city in the west, Gothenburg, and two major cities in the south, Malmö and Helsingborg, have not been found. It has, however, turned out to be possible to find a non-negligible number of gifts in the county of Gothenburg, the county of Malmö and Helsingborg, and three more countiesFootnote2 primarily by using estate inventory reports. The gift tax was integrated with the inheritance tax so gifts given up to 4 years before death had to be reported in the estate inventory.

We also must point out that although forms were filed by recipients in their home county, in a substantial number of cases the donor resided in another county. The gifts create a geographic network that spans all of Sweden and extends abroad. As a result, although registers are missing, donors from southwest Sweden are included in the investigation to a certain extent too.

The time period of the investigation is 1942–1950.Footnote3 The year 1942 is a natural starting point as a new inheritance and gift tax law started to apply that year – only 6 years in advance of the major reform that we examine. The period has been chosen to allow the study of not only the actual transition from one tax system to another but also to allow the study of the periods before and after the ‘tax panic’ of 1945–1947. The period 1942–1944 thus reflects the ‘normal’ giving of the old tax system, in which recipients paid a low and differentiated tax according to the family relationship of the donor and the recipient. Example: A gift of 15,000 sek (equal to roughly 300,000 sek or 30,000 EUR today) would yield a tax of 390 sek if the recipient was a direct descendant (tax class 1) and of 1060 sek if the recipient was the descendant of a relative or an ancestor (tax class 2). All other recipients would pay 2640 sek (tax class 4). The years between 1945 and 1947 reflect the period during which tax avoidance would be expected. We are prone to interpret all excess giving during this period as a sign of tax avoidance. Lastly, the period 1948–1950 reflects normal giving after the reform. The tax schedule remained the same as in the 1942 tax reform but the estate tax and the gift tax on estates were introduced (Ohlsson, Citation2011, p. 569). It is to be expected that some gifts in January 1948 were simply filed too late, but as the motive of each gift cannot be studied, we leave that aside.

We have used the material to build a database. The resulting database (Gilda) contains in all 36,551 gifts.Footnote4 Of these, 30,565 were received in the nine core counties and 5166 in the five supplementary counties. The database also includes 1322 gifts received in other counties in Sweden and gifts going to abroad that were not filed in the core counties. The gift tax yielded in total SEK 107.7 million during the period 1942–1950. The sum of taxes paid on the gifts in Gilda is SEK 64.8 million, so Gilda covers slightly more than 60% of total gift tax revenue during the studied period.

There are 12,682 individual donors, 36,522 gifts and 24,917 individual recipients in Gilda. An extensive discussion of the sources and how we have used them to construct the database Gilda can be found in Appendix 2. Methodological concerns are also addressed in Appendix 2. Only deceased individuals have been included in Gilda, which has been established with the help of the current population register.

4. Who were the 1940s Swedish business elite?

From Gilda, we extract all members of the business elite engaged in PHM, the ‘planned economy resistance movement’, comparing them to the total population of CEO:s in the material.

This begs the question of how we define the politically active business elite and who they were. We have defined our field of investigation by resorting to two standard works on PHM and the business elite in the 1930s and 1940s: Sven Anders Söderpalms Direktörsklubben and Niklas Stenlås’ Den inre kretsen. Söderpalms work was published in 1976 and can be characterised as traditional political history with a focus on the actions of big business – especially the so-called Directors’ Club formed by 5 CEOs of Sweden’s major exporting businesses – versus the political sphere. Niklas Stenlås’ study was published in 1998 and has a theoretically more advanced approach. It focuses on the networks of the historical actors engaged in PHM, on their family ties, as well as on their friendships, linking the networks of the inner circle to the political actions. Stenlås (Citation1998, pp. 343–344) was able to prove Söderpalm wrong in a few instances, resulting from the method of consequently studying the correspondence of the inner circle.

We have chosen to define our investigation through Stenlås study, extracting all CEO:s and owners plus all professionals of the interest organisations of Swedish business (Svenska Arbetsgivarföreningen, Svenska Bankföreningen, Köpmannaförbundet, Näringslivets fond, Sveriges Grossistförbund, Lantbruksförbundet, and Industriförbundet) in his investigation. We have thus included all actors involved in setting up and running the following projects: Näringslivets fond, Libertas, Garantistiftelsen 1946 U.P.A. and a number of subscribed actions to support the conservative party and the liberal party 1928–1940, plus all the actors present at a famous rallying meeting at restaurant Operakällaren in April 1942. In a few cases, we have supplemented actors not explicitly mentioned by name by Stenlås but mentioned by Söderpalm. We have excluded actors who were solely engaged in the political sphere, with no evident occupation or family liaison connected to big business. We have also excluded a small number of actors who died on the brink of the 1940s.

The total number of historical actors extracted is 132. We utilised the same sources as for Gilda with the addition of Svensk Industrikalender 1947 to identify the actors (if not evident from Stenlås, Citation1998) and find their title, date of birth and death, and marital status at date of death.

Who were these men? The oldest of them by far was born in 1866 and the youngest in 1912. The absolute majority of them were born between 1880 and 1895, being in the age between 45 and 60 at the beginning of our period. Their age corresponds quite well to the period one would expect a person to have reached a very senior position in big business. It is also evident that the social norm in this group was to be married. 102 of the 132 men were married, 27 of them widowers, 3 were divorced and 2 unmarried. Five of them were noted in the sources as bankers, CEOs of the major banks (Stockholms Enskilda Bank, Handelsbanken, Skandinaviska banken and Skånska Banken), while the absolute majority, 101 individuals, were titled ‘direktör’ (director), ‘verkställande direktör’ (CEO), ‘disponent’ (an older term meaning managing director), or ‘bruksdisponent’ (an older title meaning managing director of ironworks or steel producing company), including a number of individuals who were noted as retired. A few of them had not reached the position of CEO and were titled engineers. There were also a few officers, a landowner, a shipowner, a merchant, an architect, a few members of the legal profession including a country governor, and an editor.

In what way and to what extent did these individuals represent big business in Sweden? Of the 15 biggest companies in Sweden 1944/45, in terms of numbers of employed, 11 were represented directly by their CEOs. ASEA, Husqvarna, Uddeholm, Götaverken, SKF, SCA and LM Ericsson were represented in the material by more than two individuals; Sandviken, Fagersta, Bofors and Hellefors only by one (Jagrén, Citation1986, p. 261). A few more of the 15 were in fact indirectly represented by their owners in the form of their banker. This concerns Stora Kopparberg, Swedish Match and Gränges which belonged to the Wallenberg bank sphere. In terms of branches, mining, steel and pulp producers were heavily represented as was the emerging engineering industry (e.g. ASEA, Separator, Atlas, Electrolux, Åtvidaberg), but brewing, textiles, shipping, construction, chemicals and the food industry were also represented, as was the publishing business and the insurance companies. All in all, Swedish big business was well represented in the political campaigns.

Small-scale business did not have a political voice to the same extent. According to Stenlås (Citation1998), it contributed to the PHM movement financially, but it did not plan the actions or sit on the boards. Only two companies represented in the material cannot be located by resorting to Svensk Industrikalender 1947 and it is possible that they should be categorised as small-scale business. Only the building contractor F.O. Peterson & son in Gothenburg, represented by the son of the founder, can with any certainty be called a small business.Footnote5

Totally we have included 115 director’s wives in the study – 2 of them sported an occupational title: 1 library assistant and 1 physician – as well as 13 widows of men who passed away during the period.

All of the actors were not found in any of the county registers and we cannot confirm that they were donors. We have located 65 of them as donors in Gilda, meaning that 49% of the business elite to our knowledge did give away more than 3000 sek (3000 sek being the gift tax threshold) in the period 1942—1950. We have also, adopting the networks approach that guided Stenlås’ study, included their wives and widows in the investigation. As we shall see, this affects the results. There are 11 cases where the wife, but not the husband, is a donor in Gilda. So all in all, there are 76 business elite couples who are donors in Gilda.

5. Some comparative remarks on the gift explosion and the business elite

Gift tax revenue in Swedish history has three distinct peaks – 1919, 1933 and 1947 – but the 1947 peak is certainly the most important. In 1947, gift tax revenue was 20 times higher than the annual averages before and after. Gift tax revenue was higher than revenue from the inheritance tax. The effect of the gift tax revenue was, in other words, as if mortality had doubled in 1947. The total number of individual donors in Gilda are 12,682 and they gave in total 915.6 msk or 19.6 bsek in 2021 years’ price level.Footnote6

To position the actors in the business elite, we proceed to comparing the business elite group to the subgroup of directors in Gilda. To position the actors in the business elite in a wider elite group, we then move on to the top percentile of Gilda and its share of business elite members.

All in all, 76 of the 132 industrialists in the business elite, and/or their wives, are confirmed donors. This is the group we are going to discuss onwards in this paper. In Appendix 1, 76 donors are listed in total, together with their wives. The total sum given during the period includes both individual gifts by the husband and the wife, and joint gifts.

The majority of donors in this group gave substantial sums. The median total gift amount per individual in Gilda is 23,300 sek. (Unfortunately it is not possible to calculate the total per couple in Gilda in general.) Only nine of the donor couples in the business elite gave less than that. These families can probably be regarded as ‘underperformers’, in all likelihood taking an active decision not to give away their fortune. We do not have access to current information about the income and net wealth but we do have information about income and net wealth of the couples in the business elite in 1930. The presumption is that the majority of couples in the business elite would have amassed greater net wealth in the 1940s than in 1930. It is evident that couples that were very young in 1930 then had no net wealth to speak of. Wealth followed the classical age wealth profile. A few couples that were very wealthy already in 1930 (Jacobsson, Wicander), however, gave very little. On the other hand, families Westerberg, Bergengren, Wistrand, Kempe, Göransson, Wehtje and Jacob Wallenberg (unmarried) all gave in total an amount that equals more than 20 msek in present prices. Of these ‘superdonors’ Bergengren, Wistrand and Wallenberg were very rich already in 1930 and presumably even richer in the 1940s ().

The interesting question is the rationality behind the gifts. To classify them as a form of tax avoidance, the ideal would be to certify that the money would not have been given independent of the tax reform. There is no way of knowing this, but there are a couple of indicators of tax avoidance with dynastic properties. As can be seen, the absolute majority of the gifts were given in the period before the tax reform was realised, not after. If the aim had been to keep control over capital and to ease transference of capital from one generation to the next, the money would have been given to institutions (foundations). When it comes to giving to organisations, as part of the planned economy resistance or simply to avoid tax, it can safely be stated that this was not part of the gift explosion. Only 1 gift or in total 0.28% of the total number of gifts of the business elite (351) was given to an organisation. This claim is also valid for Gilda in general. The absolute majority of gifts were given to persons. Our interpretation is that they were given to maintain the family fortune rather than to keep the company intact. Giving away promissory notes rather than cash would allow for continued control over the capital given away. We have only scattered evidence regarding the nature of gifts (cash, promissory notes, landed property, etc.) as complete information on the nature of the gift is only given for the counties of Kopparberg, Kronoberg, Norrbotten and Uppsala. We will return to this issue in the last section of this paper. However we still conclude that the gifts of the business elite according to our interpretation do not reflect a general pattern of generosity, they reflect a strategic generosity specific to this particular historical situation.

Can the donorship of the business elite be construed as typical of Swedish business in general? The answer to this question is yes in the sense that directors were in general donors. The subgroup of directors, CEOs and managers (including the 52 in the business elite and including former directors) made up a hefty 1502 or 11.8% of the total donors in Gilda (). This makes them the largest professional category among the donors, excluding the more numerous wives and widows. They were grossly overrepresented in relation to their share of the employed population, which was 1.11% in 1940.Footnote7 In a second respect, there is a close correspondence between the director donors in general and the business elite: the median birth year was 1886 in the former group and 1886 also in the latter. In other words, the average director donor was about 48 years of age in the beginning of our period. The directors in general in Gilda gave on average 131,700 sek, and the median gift was 59,200 sek, which was however substantially less than the business elite directors.

Table 2. Share of CEOs in different subsamples.

In total 30 of these 1502 directors belonged to the top percentile group of Gilda. If we compare the business elite to the directors in general, a larger share of the business elite donors however belonged to the top percentile. Eight of them did, taken as individuals, i.e. excluding their wives. Including the donations of the wives, the figure rises to 10. In total 6% of the 130 donors in the top percentile group belonged to the 1940s Swedish business elite. These are listed in the table below ().

Table 3. Actors in the Swedish business elite in the top percentile group of donors.

Seen from the top percentile group, it is however striking that 30 of its top 130 donors were CEOs or directors, or ex. directors, of private business. This further supports the hypothesis that this social group in Swedish society was in general more prone to react to the tax reform proposals than others ().

5.1 The relationship between donor and recipient: family fortune and tax avoidance

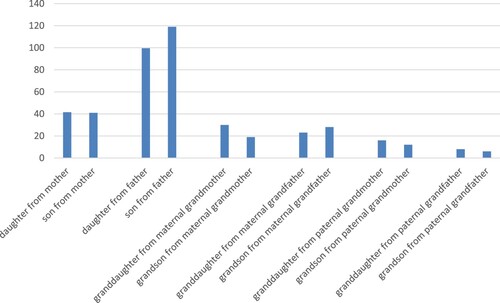

Let us now leave the donors in the business elite. We now take the individual gifts of the business elite as a starting point and take a closer look at the recipients and their relationship to the business elite donors. Only 1.5% of the gifts were given to non-relatives. A very small percent of gifts were given to husband/wife or in-laws. But the absolute majority of gifts were given to direct heirs ().

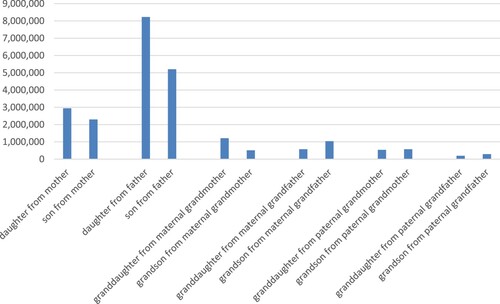

444 gifts or 95.9% of the total were given to direct heirs. Fathers gave a larger number of gifts than mothers and the most common gift was from a father to a son, fathers giving fewer gifts to their daughters. Mothers gave slightly more gifts to daughters than to sons.

Both men and women also gave to their grandchildren but much more to their maternal grandchildren than to their paternal grandchildren. Resources were channelled to the offspring of daughters to a larger extent than to the offspring of sons, somewhat balancing the fewer gifts directly to daughters. There is some generation skipping going on here, but it is more of a ‘daughter skipping’. There is also a same-sex pattern in the giving to grandchildren; maternal grandmothers obviously being prone to skip their daughters and give to their granddaughters.

The number of gifts, however, do not tell the whole story, as the gift sums are highly different. If we instead look at the amounts given from the perspective of the donor–recipient relationship, a somewhat different result emerges ():

All in all, daughters received larger gifts than sons, and they received larger gifts from their fathers than from their mothers. Out of the total 25.2 msek totally given by the Swedish business elite, nearly a third, or slightly more than 8 msek, was given by fathers to their daughters. Mothers in this group also gave more to their daughters than to their sons. The donor group that benefitted the most was thus daughters, receiving in total 11 msek from their parents. This sum constitutes 44% of the total amount given. Granddaughters also received substantial sums from their maternal grandmothers while grandsons received more from their maternal grandfathers. Again, the same-sex pattern is evident in giving, and again, paternal grandparents were not giving to the same extent as maternal grandparents.

The pattern of giving strongly suggests that gifts can be interpreted as a form of advance inheritance. Daughters received fewer but larger gifts than sons. The advance inheritance of a generation of daughters in the business elite must have created conditions of life for this group different from the ones both of the preceding and the following generation.

Can giving be interpreted as tax avoidance by the donors? We answer this question with yes. We have not found any other plausible reason for this sudden collective burst of generosity than the wish to avoid the new estate tax and the increased inheritance tax to the extent possible. We thus interpret the giving of the business elite as a response to the introduction of an enhanced mode of institutionalised and state-led redistribution. The response took the form of an intensified informal giving with evident dynastical properties. Faced with the threat of ‘expropriation’ of their fortunes, the old mode of redistribution based on the family network grew from a torrent to a flood.

5.2 Donors in context

In the following, we will take a closer look at three donors or donor families in their context. To investigate every donor in the business elite in context is not viable, it would create a massive body of information and an as large body of text. To exploit the richness of the material and demonstrate a few finer points of the gift explosion, such as the structure of giving, the dynastic rationality and the different motives for giving evident in the material, we have chosen three cases that are all principally interesting. We have chosen the three examples to explore the differing strategies of donor families; the selection is polarised. These three cases are families Åhlén, Nisser and Kempe-Carlgren. The Åhlén family employed a very clear dynastic strategy but donor Maja Åhlén also displayed an unusual paternalistic donor strategy. The married couple Nisser gave to their direct offspring. Their gifts were in the form of promissory notes: gifts were formal but the power over the resources given was kept by the parents. The gifts of the Kempe-Carlgren family form long and complicated gift chains. It is possible that the given sums were forwarded, thus giving the impression of resources trickling downwards and outwards in the family tree. All three families belong to the upper echelon of the business elite in terms of participating in the gift explosion; and all three belong to the top percentile group of Gilda – in the case of Åhléns not CEO Gösta Åhlén but his mother Maja. All three families were active donors and gave a large number of gifts.

5.2.1. Gösta and Maja Åhlén

Gösta Åhlén was born in 1904 in the parish of Ål in the county of Kopparberg. He was the son of J. P. Åhlén, the founder of the trading firm Åhlén & Holm, and Maja Åhlén, née Brolin. The firm was founded in 1899 and famous in Swedish history for launching the first Swedish mail order catalogue. Gösta was the oldest son; he had three younger siblings. His younger brother Ragnar also worked for the family firm. Gösta Åhlén went into the family firm and became its CEO in 1939, which he remained until 1969. Gösta married Gunhild Hörberg, her father was director Karl Hörberg and her mother Elsa was born Sievers. The Åhlén family story tells us about rapid upward social mobility.

In 1945, Gösta became a donor: he gave 200,000 each to his 3 daughters Karin, Inger and Kerstin. He was the sole donor; his wife Gunhild did not contribute to the gifts. The act of giving seems to have been a dynastic strategy: his brother Ragnar did exactly the same in 1945, donating 100,000 each to his 4 children. The Åhlén brothers together gave away 700,000 sek in 1945, or roughly 15,130,000 sek in present prices. The hierarchy between the brothers is reflected in the size of the gifts. The Åhlén brothers, with Gösta ranking no 15 among the business elite donors, represent a type of giving that must be deemed normal in the inner circle of the business elite, giving to their children. But they were not the sole donors in the Åhlén family. Their mother Maja is the donor in Gilda who gave the highest number of gifts. She is also the 15th largest donor in Gilda. In total, she gave 60 gifts (in total 1,772,150 sek) in between 1944 and 1947 with only one of them given in 1944. The sum of each gift ranged from 3100 to 102,000 sek. She gave 10 gifts of 102,000 sek each in 1946. All of the recipients were family and among them were the 4 children of her younger son Ragnar. They thus received money both from their father and their grandmother. Her daughters’ young children Gunvor, Hjördis and Ragnar Beck were also recipients. She gave 50,000 sek each to 6 other family members, three of whom carried the name Brolin, her maiden name. Two of them were her nephew and niece. These 16 large gifts are, exempting the one gift of 1944, the first of Maja’s gifts. The Åhlén family fortune was rapidly transported out into the diverse branches of the family network.

After Maja had finished this process of enriching her wider family network, she started giving to persons unrelated to her. In the autumn of 1947, 41 gifts of 3100–15,000 sek were given by her to persons she had no family relations with. A fair share of these 36 individuals were born in Ål and parishes close to Ål and all but six of them are proven employees of Åhlén & Holm or other companies in the Åhlén group. The majority of the 30 Åhlén employees were senior officers. In a few cases, the employee was also a relative by marriage. Maja Åhlén is thus the only donor related to the Swedish business elite who can be proven to have adopted a paternalist donor strategy. Whether the gifts were a loyalty bonus, an encouragement or just a matter of personal regard, we cannot know. The sums were not big enough to give rise to economic independence, but that was perhaps never the aim.

The pattern created by the gifts demonstrate very clearly that the Åhlén business empire interweaves three types of relationships: the family relationship, the neighbourhood relationship and the employer–employee relationship. It is likely that tax avoidance was an ulterior motive for the Åhléns.

5.2.2. William and Märta Nisser

The Nisser family is yet another family with strong connections to the province of Dalecarlia and to Swedish industrialisation. In 1854, William A. Nisser sr founded the Hofors sawmill with his brothers-in-law J. H. Munktell and Thore Petre. His son Samy Nisser became director of the Hofors sawmill in 1874. After Samy his brother Ernst took over in 1890. Eventually the family came into the possession of Grycksbo paperworks through the Munktell connection. The son of Ernst, William Nisser jr, born 1882, became director of Grycksbo in 1922. The family were landowners as well as industrialists and William grew up on the Lövåsen manor, then Rottneby. William married into another landowning family, the Hennings, when he took Märta Carolina Hennings to be his wife in 1912.

William and Märta Nisser are particular in one sense; all their gifts were jointly given. They are also particular in the sense that their giving started early in the 1940s. 4 of their 8 gifts were given in 1943 and the rest in the autumn of 1947. In total, they gave 968,380 sek and it all went to their sons. On the first of January in 1943, four gifts of 56,100 sek, in shares, were given to the 4 sons.Footnote8 The date tells us that these gifts were probably planned; they were part of a ritual transfer of wealth to the younger generation and in all likelihood they consisted of shares in companies the family owned and managed. The two older sons Ernst and Fredrik lived in Stockholm at the time. The two younger sons, Henrik and Bengt Georg William, still resided at Grycksbo.

In the autumn of 1947, all 4 brothers were yet again given the same amount: 150,000 sek each. Bengt and Henrik were given promissory notes, and as they still resided in Dalecarlia we know this. Fredrik and Ernst were in all probability also given promissory notes, although as their gifts tax returns were filed in Stockholm, no such information is given. This tells us that these gifts were not as planned and not a part of the normal generational transfer of wealth. These gifts were clearly part of the gift explosion. William kept the control over his finances but the future inheritance and estate tax could be avoided.

William and Märta were not the only members of the Nisser family to partake in the gift explosion. The descendants of Samuel Martin Nisser, director of Klosterverken, to which belonged Stjernsund manor, also had money to give. Carl Wilhelm Nisser (b. 1897), son to the industrialist Martin Nisser, gave in total 292,000 sek. The sum was given in December 1947 and consisted of 4 gifts of 73,000 each to his 4 children. Carl’s 3 sisters, Margit Richert, Ellen Wettergren and Märta Aschan, were also donors. All in all, the Nisser siblings of Stjernsund gave 439,170 sek to their offspring. The Nissers are overall typical members of the business elite in giving solely to their direct heirs and in handing out more promissory notes in the late 1940s than previously.

5.2.3. Erik and Naima Kempe

Erik Kempe was born in 1898 in Hemsö, Ångermanland. The Kempe family owned a number of sawmills and also went into pulp production in 1903 when they acquired the Husum sawmill. Erik Kempe was the third generation Kempe to run the geographically wide Kempe business empire. Erik had, somewhat unusually, a university education from Uppsala University and acquired a doctorate in political science. In 1928, at the age of 30, he went home to northern Sweden to become the director of Robertsfors. In 1949, he became the CEO of the Mo & Domsjö Ltd, the crown jewel of the business empire. In 1924, Erik Kempe married Naima Wilhelmina Wahren, of the textile merchant family Wahren from Norrköping. The Wahrens owned a part of Holmens papermill and the textile business was soon turned into a subsidiary to Holmen. The marriage was thus a union between two competing industrial dynasties.

The donorship of Erik Kempe is very straightforward. There are only 6 gifts. They were given in December 1942 and November 1947, to his 3 daughters Helga Charlotta (married Peppler), Anna Catharina and Naima Antoinette. The notable aspect is the total sum given. Erik gave each daughter 462,500 sek or in total 1,387,500. Erik thus gave nearly 28 msek in present prices.

Erik Kempe was, however, widely surpassed as a donor by the widow of his uncle Frans, Eva Charlotta Kempe, b. 1863. She gave in total 1,937,958 sek in 1947, or 40.5 msek in present prices, distributed on 11 gifts. All of it went to her offspring, with the son Johan Carl Kempe and the daughter Fanny Charlotta Carlgren receiving the two most substantial gifts – 500,000 sek each. Other recipients were her grandchildren and two inlaws: the daughter-in-law Marianne Kempe and the son-in-law, Mauritz Carlgren, who got 24,800 sek each. The two daughters of her son received much more than her other grandchildren: 300,000 sek each. Perhaps it was because her daughter’s children were also given money by Fanny, their mother, so the children of her son had to be compensated.

The recipients of Eva Charlotta were also donors. Her daughter-in-law Marianne in her turn in 1949 gave nearly exactly twice the amount she had received from her mother-in-law to her husband, 49,800 sek. This was after the tax reform. But above all, Fanny Charlotta Carlgren, who had received 500,000 sek from her mother, gave more than she received. Her total gift sum, 1,739,661 sek, is almost identical to her mother’s. Her 14 gifts above all went to her children and grandchildren – two of them were small sums to persons who were not family. Some of her recipients were identical to her mother’s: her children were given money both from their mother and grandmother. The gifts of mother and daughter seem co-ordinated: Eva Charlotta Elisabet von Bodelschwingh was given less than her daughters by her mother but had already received from her grandmother. Of Fanny Charlotta’s gifts, 11 were given in November and December 1947.

All in all, there were 11 donors in the Kempe family network. Erik’s cousin Anna, married Hwass, gave 544,070 sek, distributed on 11 gifts. Anna had no children so she gave to more distant relatives and non-relatives. Her largest gift of 150,000 sek went to her niece Carola Tersmeden, daughter to her sister Vera. Carola in her turn was also given in all three gifts by her mother Vera, the total was 370,093 sek.

The Kempe family is unique in the complicate pattern of money flows as well as in the size of the resources redistributed. The 11 donors together redistributed 6,404,632 sek or in present prices 137,475,431 sek. The sum is vertiginous. It is fully possible that the individual acts of giving within this family constitute a causal chain. In reality, one sum of money once transferred can have caused another act of giving, so that this sum was given, in parts of as a whole, more than one time.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we believe that we have advanced our knowledge on the economic reproduction of the Swedish business elite. We also believe that this investigation sheds new light on the business resistance against the planned economy. We have penetrated the giving of the Swedish business elite and found it to be more substantial than the average donor’s, and more substantial than the giving of directors in general. In total, 76 of the 132 members of the business elite are confirmed donors if we include their wives in the investigation. The total gift sum was 25.2 msek.

Let us now turn to our hypotheses:

Our first hypothesis was that the recipients of gifts would prove to be direct descendants, thus the gifts will prove to have a dynastic function and be directly linked to the change in inheritance taxation. This has indeed been confirmed: 444 gifts or 95.9% of the total were given to direct heirs. But, they were not given in equal amounts. All in all, daughters received larger gifts than sons, and they received larger gifts from their fathers than from their mothers. Out of the total 25.2 msek totally given by the Swedish business elite, nearly a third, or slightly more than 8 msek, was given by fathers to their daughters. Why this was so we do not know and it is certainly not in accordance with established patterns of inheritance in Sweden. Further research into the gender distribution of both donorship and the reception of gifts would be interesting. We are also convinced that this issue could in future be studied from a generational perspective. The gifts to heirs potentially contributed to a particular type of freedom for the generation born before 1948, as they could use their gifts – in reality advance inheritance – when they came of age. The same possibility was not enjoyed by offspring born later.

Our second hypothesis was that the results will in total point to a more complex rationale of the planned economy resistance movement than the aim of defending free enterprise, namely a rationale that concerns the reproduction of the business elite: the men and wives as owners and their children as future owners. Here, we have come to the conclusion that the donorship of the Swedish business elite is closely correlated to their political activities to counteract the 1947 tax reform. In public, these men argued that the reform would rob them of their power of initiative and be to the detriment of the development of private business. They also, through their companies, partook in funding political actions against the reform. In private, businessmen, together with their wives, counteracted the effects the reform would have on their personal finances and those of their families. Resources were sometimes transferred in a form that allowed the donor to keep the control over the resources: the promissory note. The private and silent crescendo of gifts in 1947 tells a tale not of the reproduction of business, but of the reproduction of families within the business elite.

One interesting comparison is between the extent of funding raised for the planned economy resistance and the extent of personal donorship. It seems that the political project of counteracting the tax reform in a joint effort of Sweden’s largest and most successful companies could raise 24.8 msek, compared to the 25.2 msek silently and privately transferred by the 76 couples of the business elite to above all their children. The sums are almost identical, and our interpretation is that this says something concerning the motives for the actions: they were personal and dynastical as well as professional. The three historical examples we have explored, families Åhlén, Nisser and Kempe, demonstrate that further explorations of the dynastic aspects of giving would in all likelihood be rewarding.

We have thus found the research area of donorship and the method of mapping donors, recipients and gifts in this particular historical situation a viable path to a more thorough understanding of the motives of the Swedish business elite. We would also like to suggest that what we have studied here is an aspect of the transgression from one pattern of redistribution to another. The tax reform of 1948 created a more fine-meshed net of tools with which the initiative of redistribution was taken from major owners and given to the state. We know from the last decades that this change was not final; the abolishment of inheritance and gift tax in Sweden in the 2000s effectively reversed the situation. To understand the consequences as well as the differences of the two models of redistribution in history, this is an area which would benefit from further studies.

Sources

GIftExpLosion DAtabase (Gilda), version compiled 2022-11-04.

Riksarkivet (The Swedish National Archives), Folkräkningen 1930. (The 1930 Census) https://sok.riksarkivet.se/folkrakningar

Riksarkivet, Svea Hovrätt, Advokatfiskalens arkiv 1614–1965, D IX Register över gåvodeklarationer, D IX a:1–D IX a:17, D IX b:1–D IX b:5 SE/RA/420422/02/D/D IX

Landsarkivet i Härnösand, Norrbottens läns landskontors arkiv 1574–1976, G IV j Handlingar ang gåvoskatt, G IV j:3 – G IV j:6 SE/HLA/1030007/G IV j

Landsarkivet i Uppsala, Länsstyrelsen i Kopparbergs län, Landskontoret 1626–1957 B I h Diarier för gåvo- och kvarlåtenskapsskatt, B I h:1 SE/ULA/12903/11/B I h

Landsarkivet i Uppsala, Länsstyrelsen i Uppsala län, Landskontoret 1634–1957, G 3 O Gåvoskattedeklarationer, G 3 O:5 – G 3 O:12 SE/ULA/11035/21/G 3 O

Landsarkivet i Vadstena, Länsstyrelsen i Jönköpings län, Landskontorets arkiv 1620–1957, C II b Förteckning över gåvodeklarationer SE/VALA/01971/C II b

Landsarkivet i Vadstena, Länsstyrelsen i Kronobergs län, Landskontorets arkiv 1635–1953, D VII Handlingar till gåvoskattediarium, D VII:3 – D VII:7 SE/VALA/01974/D VII

Statistiska Centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden): Folkräkningen den 31 december 1940, III Folkmängden efter yrke, (The 31 December 1940 Census, Part III ‘The population according to occupation’), 1943. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/aldre-statistik/innehall/sveriges-officiella-statistik-sos/folk-och-bostadsrakningarna/folkrakningen-19101960/folkrakningen1940_sos/

Svensk Industrikalender 1947. Tjugonionde årgången. Stockholm: Sveriges Industriförbund. http://runeberg.org/svindkal/1947/ (2021-08-18).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 GIftExpLosion DAtabase (Gilda), version compiled 2022-11-04.

2 The counties of Södermanland, Örebro and Östergötland.

3 Gifts from before 1942 are included when it is necessary to be able to replicate the tax calculation.

4 Gilda is continuously updated. The results reported here are based on the version of Gilda compiled 4 November 2022.

5 Svensk Industrikalender 1947.

6 All price conversions have been undertaken on the basis of Edvinsson & Söderberg, Citation2011.

7 The 1940 Census, part III, table 20, p. 308. Own calculation.

8 The Nisser brothers had already in 1939 received the dividends of these shares as gifts. Now they received full ownership of the shares. The source is: Länsstyrelsen i Kopparbergs län, Landskontoret, Diarier för gåvo- och kvarlåtenskapsskatt, p. 32.

References

- Albertini, M., & Radl, J. (2012). Intergenerational transfers and social class: Inter-vivos transfers as means of status reproduction? Acta Sociologica, 55, 107–123.

- Augustine, D. (1994). Patricians and parvenues. Wealth and high society in Wilhelmine Germany. Berg.

- Beckert, J. (2007). The Longue Durée of Inheritence Law. Discources and institutional development in France, Germany and the United States since 1800. European Journal of Sociology, 48, 79–120.

- Beckert, J. (2008). Inherited wealth. Princeton University Press.

- Bengtsson, E. (2019). The Swedish Sonderweg in question: Democratisation and inequality in comparative perspective, c. 1750–1920. Past and Present, 244(1), 123–161.

- Bengtsson, E., & Moliner, J. (2021). What happened to the incomes of the rich during the great levelling? Evidence from Swedish individual-level data, 1909–1950. . Lund Papers in Economic History, 230.

- Berghoff, H. (2013). Blending personal and managerial capitalism: Bertelsmann’s rise from medium-sized publisher to global media corporation and service provider, 1950–2010. Business History, 55(6), 855–874.

- Colli, A., Howorth, C., & Rose, M. (2013). Long time perspectives. Business History, 55(6), 841–854.

- Davidoff, L., & Hall, C. (1987). Family fortunes. In Men and women of the English middle class 1780–1950. Routledge.

- Edvinsson, R., & Söderberg, J. (2011). A consumer price index for Sweden 1290–2008. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(2), 270–292.

- Elvander, N. (1972). Svensk skattepolitik 1945–1970: en studie i partiers och organisationers funktioner. Rabén & Sjögren.

- Erixson, O., & Ohlsson, H. (2015). Förmögenhet – Mina pengar eller släktens? Ekonomisk Debatt, 2, 17–27.

- Gill, G. (2008). Bourgeoisie, state and democracy: Russia, Britain, France. Germany and the USA. Oxford University Press.

- Gustavsson, M., Husz, O., & Söderberg, J. (2009). Collapse of a bourgeisie? The wealthy in Stockholm, 1915–1965. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 57(1), 2009.

- Hasselberg, Y., & Petersson, T. (2006). ‘Bäste broder’. Nätverk, entreprenörskap och innovation i svenskt näringsliv. Gidlund.

- Husz, O. (2013). Att räkna värdighet. Privatekonomi och medelklasskultur vid mitten av 1900-talet. Scandia, 79, 87–121.

- Jagrén, L. (1986). Företagens tillväxt i ett historiskt perspektiv, IUI working paper no. 165. The Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IUI).

- Jones, C. A. (1987). International business in the 19th century: The rise and fall of a cosmopolitan bourgeoisie. The New York University Press.

- Jones, G., & Rose, M. B. (1993). Family capitalism. Frank Cass.

- Keister, L. A., Benton, R. A., & Moody, J. W. (2019). Cohorts and wealth transfers: Generational changes in the receipt of inheritances, trusts and inter vivos gifts in the United States. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 59, 1–13.

- Lewin, L. (1967). Planhushållningsdebatten, 2. Upplagan. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Mackie, R. (2022). Succession and inheritance in Scottish business families, c. 1875–1935. Business History, 1, 55–74.

- Marceau, J. (1989). A family business? The making of an international business élite. Cambridge University Press.

- Mills, C. W. (1956). The power elite. Oxford University Press.

- Norrby, G. (2005). Adel i förvandling: adliga strategier och identiteter i 1800-talets borgerliga samhälle. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Historica Upsaliensia, 217.

- Nydahl, E. (2010). I fyrkens tid. Politisk kultur i två ångermanländska landskommuner 1860–1930 [Mid Sweden University doctoral thesis] 100.

- OECD. (2021). Inheritance taxation in OECD countries, OECD tax policy studies 28. OECD Publishing.

- Ohlsson, H. (2011). The legacy of the Swedish gift and inheritance tax, 1884–2004. European Review of Economic History, 15(3), 539–569.

- Ohlsson, H., Roine, J., & Waldenström, D. (2020). Inherited wealth over the path of development: Sweden, 1810–2016. Journal of the European Economic Association, 18, 1123–1157.

- Piketty, T., & Zucman, G. (2015). Wealth and inheritance in the long run. In Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 1303–1368). North-Holland.

- Poterba, J. (2001). Estate and gift taxes and incentives for inter vivos giving in the US. Journal of Public Economics, 79, 237–264.

- Rose, M. B. (1999). Networks, values and business. Entreprises et Historie, 2, 16–30.

- Schmalbeck, R. (2001). Avoiding federal wealth transfers taxes. In W. G. Gale, J. R. Hines, & J. Slemrod (Eds.), Rethinking the estate and gift tax (pp. 113–158). Brookings Institution Press.

- Söderpalm, S. A. (1976). Direktörsklubben: Storindustrin i svensk politik under 1930- och 40-talen. Zenit.

- Stenlås, N. (1998). Den inre kretsen: den svenska ekonomiska elitens inflytande över partipolitik och opinionsbildning 1940–1949. Arkiv Avhandlingsserie, 48.

- Therborn. (1989). Göran: Borgarklass och byråkrati i Sverige: anteckningar om en solskenshistoria. Arkiv.

- Thompson, F. M. L. (1994). Business and landed elites in the 19th century. In F. Thompson (Ed.), Landowners, capitalists and entrepreneurs: Essays for Sir John Habakkuk (pp. 139–170). Clarendon Press.

- Thurow, L. C. (1976). Generating inequality. Macmillan.

- Useem, M. (1984). The inner circle: Large corporations and the rise of business political activity in the U.S. And U.K. Oxford University Press.

- Wehler, H.-U. (1995). Von der “Deutschen Doppelrevolution” bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges. 1849–1914. In Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte (Vol. 3). Beck.

- Weisbach, D. (2002). Ten truths about tax shelters. Tax Law Review, 55(2), 215–253.

- Westerberg, R. (2020). Socialists at the gate: Swedish business and the defense of free enterprise, 1940–1985. Handelshögskolan i Stockholm.

Appendix 1.

Donor families in the Swedish business elite

Appendix 2.

Gilda – data sources and the method of mapping donors

This appendix gives an overview of the sources for Gilda. There are four steps for building Gilda:

Step 1. Finding the names of donors and recipients

This can done using gift tax returns. Returns are available for three main counties at three different regional archives (Kronoberg, Norrbotten, and Uppsala). There is much more information on these returns than names of the donor and the recipient, for example the diary number, the gift date, the gift amount, and the type of asset given.

There are gift tax diaries available for two more main counties at two different regional archives (Dalarna and Jönköping). The gift date, the gift amounts and the diary number of the gift are available.

There are gift tax lists available for all main counties and most supplementary counties. The gift tax lists can be found at the National Archives and the regional archives. These lists contain a lot of administrative information: the diary number of the gift, the tax return filing date, the tax decision date, the tax payment date, the tax amount paid, etc. The lists include the name of the donee, who was liable to pay the tax. But these lists do not include the name of the donor.

The regional courts supervised the gift tax collection of the county administrations. Svea Hovrätt, the regional court in the middle of the country including the Stockholm area, organised a register to able to audit the tax collection. The register looks like an analogous version of excel sheets and is available at the National Archives. This register covers six of the main counties including the City of Stockholm, the county of Stockholm, Gotland, and Jämtland. The information is the diary number, the name of the donor, the name the recipient, the gift date, and the gift amount.

There is also information in estate inventory reports. The family research site Arkiv Digital, available on the internet, provides access to most estate inventory reports for people in Gilda who passed away 1960 or before. The information content in estate inventory reports differ a lot between reports.

The family research site Arkiv Digital, available on the internet, provides access to Swedish population registers until and including 1990.

The Swedish Death Index, available on a usb stick, provides access to information about people who passed away in Sweden until and including 2022 in its 9th edition.

The web sites of undertakers and the family pages of daily newspapers provide information on death dates in recent years.

We have also used grave registers available on the internet.

The 1930 Swedish Census has information on education, income, and net wealth for individuals. The information is organised parish by parish. The census is searchable at the website of the National Archives. The problem is that the information is only digitalised for a small share of the parishes. There are, for example, only two searchable parishes for these variables in the City of Stockholm.

However, the sources for the census, excerpts from parish registers, are available on the National Archives website. Given information on where a person lived in 1930 it is possible to try to find education, income, and net wealth in the parish excerpts. The is a very time-consuming method, but we have had to use it in almost all cases.