ABSTRACT

The VRCHIVE workshop was a first-of-its-kind exploratory pilot initiative to examine the feasibility of running a remote, intergenerational Virtual Reality (VR) storytelling workshop through the Toronto Public Library. The workshop took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has highlighted a need to develop solutions to address the digital divide and consequent increased social isolation in older adults. The overall program goals were threefold: (1) to create a ‘VRCHIVE’ of 360° VR films that documented participants’ lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) to explore the challenges and successes of the program in order to evaluate its effectiveness, and (3) to understand, broadly, the program’s impact on technology literacy, feelings of isolation, and familial relationship strengthening. Five pairs of grandparents and grandchildren (n = 10) engaged in four, one-hour long online sessions each week in November 2020. Feedback was collected through facilitator observations and weekly debriefing sessions (n = 4), as well as online participant surveys (n = 3) and phone interviews (n = 2) conducted upon program completion. All intergenerational pairs successfully completed a VR film. Post-workshop, participants reported feeling less isolated, more connected with other people, and more confident in learning to use innovative technology. A detailed description of the workshop is provided, along with a discussion on recommendations for future iterations of the program that may serve as a model for other locations that wish to implement similar programming. Overall, participants reported positive experiences, and there is an appetite to sustain and scale the program in the future.

Introduction

Background

The digital divide and isolation in seniors

The circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic place individuals of all ages at risk of worsening mental health due to social isolation (Pancani et al., Citation2020). For older adults in particular, social distancing measures and the rapid switch to virtual services have shed light on the concerning health consequences of low levels of digital literacy (Daly et al., Citation2021), social isolation, and loneliness (Herron et al., Citation2021; Wu, Citation2020). Loneliness in older adults has been shown to have a clear association with depression, anxiety, and frailty, all of which are correlated with loss of independence and overall decline (Chen et al., Citation2020; Perissinotto et al., Citation2012). Unfortunately, older adults are on average slower to adopt new technologies (Pew Research Center, Citation2017), and low digital literacy has prevented many seniors from staying socially connected, albeit remotely, during the pandemic (Wu, Citation2020). Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted a dire need to develop solutions for tackling the digital divide to ensure the long-term mental and physical health of the world’s aging population (Daly et al., Citation2021).

VR as a catalyst for intergenerational connection and digital literacy

Technology adoption in older adults can be influenced by their first experiences and teaching methods used (Peek et al., Citation2016). Reverse mentoring, where a younger individual supports an older individual’s learning, has shown success in teaching seniors to use technology, as well as in strengthening connections between generations (Leedahl et al., Citation2018). Likewise, a benefit of technology use by older adults is its application as a catalyst for intergenerational connection; older adults are motivated to use technology by the desire to remain socially connected with family members by taking part in the hobbies of younger family members (Freeman et al., Citation2020). The immersive and multisensory nature of Virtual Reality (VR) could make this novel technology an especially attractive shared learning experience for pairs intergenerational participants.

When viewed through a VR head-mounted display (HMD), 360° films simulate a three-dimensional environment that synchronously stimulates the senses (e.g., vision, hearing, proprioception) to create an illusion of reality that closely resembles the physical world. This portable technology is now increasingly used as a tool in many industries including marketing, museums, healthcare, and education (Cipresso et al., Citation2018). VR equipment has also become increasingly easy to use, affordable and available; a mobile VR HMD can now be purchased for approximately $400 USD.

Social connectedness through VR storytelling

Sharing personal experiences through ‘non-VR’ digital storytelling (e.g., film, photographs, audiobooks, podcasts) has already been shown to increase connectedness with others and may be an effective way for seniors to learn digital literacy skills (Hausknecht et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Moreover, intergenerational digital storytelling was found to foster intergenerational relations (Freeman et al., Citation2019), support meaningful relationships, help to confront ageism (Loe, Citation2013), and improve awareness of older adult issues (Hewson et al., Citation2015). Enjoying togetherness through shared activities can be seen as a way to strengthen reciprocal bonds, prolong relationships, improve well-being, and foster a sense of community, ultimately improving the quality of life for all parties involved (Park, Citation2014).

The immersive and three-dimensional nature of films recorded using a 360° video camera allows individuals to relive memories and experiences. When viewed through a VR HMD, 360° film allows the wearer to – quite literally – see things from another’s perspective (Bertrand et al., Citation2018; Zak, Citation2013). These unique affordances of VR and the flexibility of the 360° video medium, makes this an ideal way to archive experiences and build empathy through storytelling. In fact, VR may hold benefits over other forms of digital media in terms of teaching empathy (Rueda & Lara, Citation2020; Theriault et al., Citation2021; Ventura et al., Citation2021). For example, recent findings suggest that having nursing students create VR film simulations of challenging patient interactions can be an effective tool for helping these students to learn how to show empathy toward their patients (Appel, Citation2021).

Community technology training for older adults

Services and technologies that promote connectedness have been recommended to help individuals cope with social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sepulveda-Loyola et al., Citation2020). Like other libraries worldwide (Caroll & Reynolds, Citation2014) the Toronto Public Library aims to function as a community hub or ‘third space.’ It has recently expanded into community health, with one of its strategic initiatives to increase comfort and confidence with digital literacy for seniors (Toronto Public Library, Citation2019).

Previous research suggests that participation in technology training workshops or programs can help develop self-confidence, promote positive attitudes, and enhance positive social interactions in older adult populations (Ma et al., Citation2020). Further, participation in online groups has been shown to broaden peoples’ feelings of community as well as deepen existing relationships through reinforcement of close ties (i.e., creating bridging ties and strengthening bonding ties; Norris, Citation2002). Yet, during COVID-19 lockdowns, a time when this type of programming can be seen as even more essential, in-person workshops could no longer continue, with many instructors left unprepared for this new virtual teaching context (Martínez-Alcalá et al., Citation2021).

The VRCHIVE project

The VRCHIVE project was a four-week exploratory community-based initiative hosted through the Toronto Public Library. Hosting the VRCHIVE project remotely within the context of the pandemic afforded the opportunity to investigate the benefits and challenges of running a community-based VR storytelling workshop for older adults entirely remotely. The project included a pilot workshop where intergenerational pairs of grandparents and their grandchildren shared their life experiences and learned from one another while learning to use 360° VR cameras to capture personal stories, create meaningful memories and share experiences. The workshop activities were designed to keep intergenerational pairs socially and intellectually stimulated, (Iizuka et al., Citation2020; Ma et al., Citation2020), to contribute to digital literacy skills (Ma et al., Citation2020), foster a sense of community (Sum et al., Citation2009), improve psychosocial health (Zhong et al., Citation2020), encourage new methods of self-expression in a supportive environment (Kaimal et al., Citation2020), and provide equitable access to novel technology (Toronto Public Library, Citation2019).

The VRCHIVE project objectives

The overarching goals of the VRCHIVE pilot were to determine the feasibility of running a remote workshop through the Toronto Public Library where intergenerational pairs of participants are trained to create VR films. The project team sought to:

Document and evaluate the creation of a ‘VRCHIVE’ of 360° films that portrayed participants’ lives during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Identify the successes and challenges of running this workshop as well as improvements for future iterations of the workshop.

And broadly, understand the potential benefits of the workshop through identifying its effect on participants’ digital literacy skills, feelings of isolation, and relationship-building.

Materials & methods

Workshop preparation

The VRCHIVE workshop was facilitated by three members of OpenLab, an innovation center based out of the University Health Network, in Toronto Canada. Logistical support was provided by the Toronto Public Library. The pilot workshop took place online from November 4, 2020 to November 25, 2020. Preparation for the workshop took approximately three months, including adapting the original format (in-person) to a virtual program. Preparation involved (1) creating a detailed agenda that described weekly topics, group activities, homework assignments, and facilitator responsibilities ( in the Appendix), (2) creating and sharing a workbook (print and digital) for participants to use throughout the workshop (), and (3) ensuring the equipment was functional and ready to be lent from the respective library branches. Ethics approval was received from the Baycrest Research Ethics Board (REB), reference number 19–17. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. Participants who agreed to share their VR-films provided additional, separate consent.

Participants

A total of ten participants (five intergenerational pairs) were recruited by Toronto Public Library to participate in the workshop through a variety of methods: an online flyer (), an Eventbrite listing, promotion by library staff, a post on the Toronto Public Library blog, an advertisement in the library’s e-newsletter, a post on their social media, a featured listing on their website, a featured listing in the ‘What’s On’ e-publication, and by word of mouth. Age requirements for intergenerational pairs included having one youth (aged 13–18 years) and their grandparent (no age requirement). All participants were required to have a valid library card with the Toronto Public Library, an e-mail address, access to the internet, and access to a computer with a functional webcam and microphone.

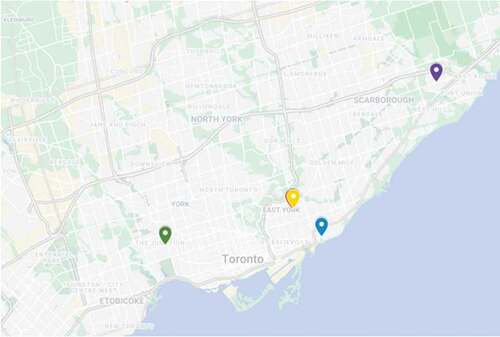

Participant demographics and contact information were collected through a self-report Google Forms survey (Appendix B). Participating grandchildren were an average age of 14 (range = 12–16) and 60% (3/5) were male. Grandparents were an average age of 72 (range = 66–84) and 60% (3/5) were male. In 60% (3/5) of grandparent-grandchild pairs, neither participant reported having ever seen a VR film before. Participants were also asked to rate their ‘level of comfort with technology as a team’ on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being ‘very low’ and 5 being ‘very high.’ Sixty percent (3/5 pairs) rated their level of comfort a 4/5 (i.e., a relatively high level of comfort) and the other 40% (2/5 pairs) rated their level of comfort a 3/5 (i.e., a moderate level of comfort). All participant pairs picked up the equipment on time from their respective local library branches, which spanned various regions of the city ().

Figure 3. Participants’ local library branches. Created using image from Google Maps (Google, Citationn.d.).

Resources

Three facilitators planned and ran the workshop and one video editor (a digital media undergraduate student) volunteered to combine participants’ media clips and export the final VR films. In addition to the weekly one-hour sessions, facilitators met before and after each session for approximately 30 minutes and 15 minutes, respectively.

The VR equipment used throughout this program (i.e., lent to participants) consisted of (1) an Oculus Go VR head-mounted device (HMD), (2) a Yi 360° VR Camera, and (3) a tripod (a range of styles depending on what was readily available at the Toronto Public Library). The Oculus Go was chosen because of its affordability, portability, and comfort. Its stand-alone nature requires no external hardware and reduces simulator sickness because of its low motion latency. The Yi 360° is a small, lightweight VR camera equipped with two 180° lenses to capture 4 K 360° film. This camera automatically stitches the two simultaneously recorded 180° videos into one 360° video without any input from the user. The Toronto Public Library coordinated the distribution of equipment to participants’ local library branches for pickup before the first workshop session. Each intergenerational pair received one ‘VR-system’ containing the VR HMD, camera, and tripod.

VR-video and audio files were stored on a Google Drive that all participants and facilitators were permitted to access. Midway through the workshop, a Google Hangouts text-based chat room including all facilitators and participants was created. Final VRCHIVE films were uploaded to YouTube and organized in an unlisted playlist.

Workshop delivery

Participants engaged in 1-hour long Jitsi video-conferencing sessions once per week, from 4:00 pm to 5:00 pm, for four weeks. Each session ended with a relevant homework assignment to be completed by the following session. Throughout the four workshop sessions, participants were taught how to film 360° video, create a storyline reflecting on their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, upload files to their computer, and watch films on a VR head-mounted device. provides a summary of activities by week.

Table 1. Summary of weekly VRCHIVE workshop activities

The ‘VRCHIVE’ VR films had two components: (1) the 360° video recording of a real-life environment, and (2) overlayed audio of the participants speaking or singing. Participants filmed the visuals using the Yi 360° VR camera and recorded audio using a device of their choice, typically a smartphone. Participants had the opportunity to watch the group’s final 360° films using YouTube’s 360° feature and the Oculus Go VR HMD.

Although the workshop tools (e.g., workbook, activities) were developed before the first workshop session, the team adapted the program as needed based on experiences from the previous session(s). For example, if it appeared that more time was needed by participants to learn to use the equipment, the agenda was updated, and more time was dedicated to this activity than may have previously been planned.

Evaluation tools

A mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate the workshop from both facilitator and participant perspectives. The final VRCHIVE films were informally evaluated by the researchers to provide a rough measure of the workshop’s impact on participant learning outcomes and better understand areas where facilitators could improve instruction and the design of workshop materials for future implementations. The films were rated for completion and quality on a three-point scale with 0 being an incomplete film, and 3 being an ‘ideal’ output in terms of completion, having both grandparent and grandchild present and speaking in the film, and technical quality, (e.g., incorporating points of interest, varied camera angles, sound quality). Ratings were not shared with participants.

Additionally, facilitators recorded detailed observational notes during the sessions and debriefed privately afterward. Unique findings from these debrief sessions were transcribed. Participants were asked to complete an anonymous post-workshop online survey created through SurveyMonkey that employed multiple-choice, 5-point Likert scale, and open-ended questions (Appendix C). Likewise, participants were given the option to take part in a semi-structured phone interview (Appendix D). Phone interviews were open-ended in nature (e.g., ‘What is the most useful idea or skill that you think you’ll take away from the workshop’) and responses were transcribed. Three researchers independently reviewed and analyzed the interview transcripts, open-ended survey responses, and observation/debrief notes, using a grounded theory and open coding approach. The three sources of information examined in conjunction to triangulate findings, capture key themes, and systematically construct theory from the data with reference to the research objectives.

Results

The VRCHIVE outcomes

Workshop participation

All participant pairs (100%, 5/5) were able to complete a VRCHIVE film, which can be accessed through the VRCHIVE website. All grandchildren (100%, 5/5) attended all workshop sessions. Most grandparents (60%, 3/5) attended all workshop sessions; the remainder attended half of the sessions (20%, 1/5) or no sessions (20%, 1/5) due to unexpected COVID-19-related restrictions.

Two participant pairs (40%, 2/5) had to significantly change their filming plans due to increased COVID-19-related social distancing restrictions/lockdowns; one grandchild could no longer visit their grandparent due to increased restrictions introduced mid-way through the program, and another grandchild had to self-isolate mid-way through the program due to exposure to the virus. Despite these challenges, these pairs were still able to successfully create a VRCHIVE film. One grandchild chose to record audio of a phone interview with their grandparent which they later paired with 360° video footage. The other grandchild pivoted their concept to a recorded 360° video of themself isolating in their room with an overlayed audio clip of their self-reflection on COVID-19 isolation and previous conversations with their grandparent. This participant consented to share their VRCHIVE film, which can be viewed here.

Evaluation of the VRCHIVE videos

On a rating scale of 0 to 3 with 0 being ‘incomplete,’ and 3 being an ‘ideal’ outcome in terms of a high-quality 360° film, all (5/5, 100%) VRCHIVE films scored a 2 out of 3 (i.e., a satisfactory outcome, with some areas for improvement). The final VRCHIVE films were highly unique and personalized, for example, one participant pair decided to tell the story of their life during the pandemic through a rap. Areas where all participants (5/5, 100%) were successful included using at least two camera shots and incorporating some movement to add interest. Two participant pairs (40%, 2/5) included time-lapse effects, and one film (20%, 1/5) included background music. Use of lighting was generally well-done in all films (5/5, 100%), considering some participants filmed both outdoors and indoors. Additionally, all films (5/5, 100%) used only steady, stationary shots (as opposed to shots with first-person movement or shaking of the camera), which is important for reducing the chance of simulator sickness for the viewer. The video archive is tied together using a ‘VRCHIVE’ workshop logo on the title page of each film.

A few areas for improvement for instruction on filming were noted. In 40% (2/5) of the participant pairs, there was an unresolved technology issue where participants could not export their films in high resolution, and in 60% (3/5) of the films, the focus of the film fell on the stitch line at times, leading to avoidable minor distortions. Additionally, no films (0%, 0/5) consistently had an element of interest situated on both ‘sides’ of the 360° lens. Especially in HMD, having an element of interest is desirable to increase the chance that the viewer has something to absorb no matter which direction they are facing.

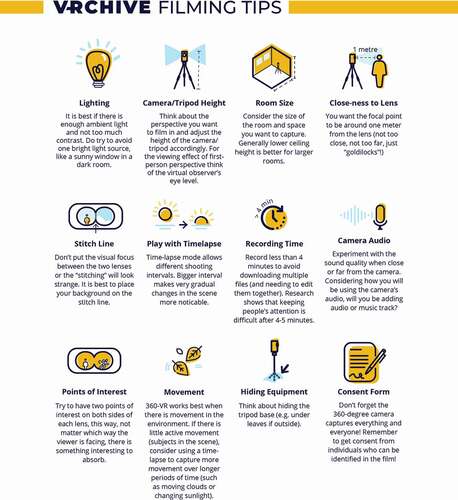

Based on these observations, the group facilitators identified several recommendations to improve the workshop outputs. First, a VRCHIVE filming tip sheet was created based on the issues described above (). Other recommendations will be addressed in the future through the creation of additional workbook pages, such as improved equipment instructions, filming tips (e.g., positioning), and a section for participants to describe how they want their film edited. Additionally, to add to the dynamism of the VRCHIVE films, facilitators should consider locating a set of royalty-free music that participants can use as background audio in their films. Lastly, the workshop logo inserted onto the title page of participants’ films served nicely to tie together the video archive, and it was recommended that future facilitators should possess the logo to be able to do the same.

Workshop outcomes: workshop format, instruction, equipment, and materials

The VRCHIVE workshop’s (1) successes and (2) challenges and improvements for future iterations were evaluated through facilitator observations discussed during debriefing sessions, as well as the post-workshop participant survey and interviews. Two grandparents and one grandchild (30%, n = 3) completed the post-workshop survey. One grandparent and one grandchild (20%, n = 2) volunteered to take part in the semi-structured phone interview. Results of the post-workshop phone interviews largely reflected the survey findings, and areas of improvement suggested by participants were often identified in facilitator debriefs.

A selection of the findings are described below. provides a summary of the key themes and suggested areas of improvement as mentioned in each distinct data collection method. was synthesized from facilitator post-session debriefing notes and lists a number of unique recommendations for conducting this remote workshop, grouped into changes to consider at the start of the session, during, and toward the end.

Table 2. Feedback mentioned in each distinct data collection method

Table 3. Facilitator suggestions grouped by session timing

(1) Successes. Participants from both generations were observed to engage and ask questions throughout workshop sessions. Notably, a unique synergy was observed within the intergenerational pairs where the grandparent tended to take a leading role with organizing and scheduling the work, while the grandchild led the learning of the technology. Overall, participant feedback from the surveys and interviews indicated that respondents felt supported to complete the project. There was also agreement across respondents and facilitators that five participant pairs (i.e., this group size) worked well for the workshop and that 1-hour long sessions were an appropriate length (100%, 3/3 survey, 2/2 interview). In terms of the remote instructional format, all surveyed participants (100%, 3/3) agreed that the videoconferencing software used (Jitsi) was an appropriate and effective format. Most participants did not experience any significant technical difficulties with any equipment.

(2) Challenges and workshop improvements. All respondents (100%, 3/3 survey, 2/2 interview) recommended that the workshop should have more sessions in total (e.g., five- or six-week program). One interview participant mentioned that a longer time frame might ease the challenge they faced with coordinating time to work on the project with their family member who lives outside the household. Additionally, all participants (100%, 3/3 survey, 2/2 interview) indicated that more time should be dedicated to VR equipment training (e.g., provide video instructions, clarify workbook instructions as the equipment manuals from manufacturers were not found to be helpful, etc.). Likewise, most participants reported that more feedback should be given regarding story development (e.g., e-mail feedback on proposed scripts, one story-telling dedicated session). It was suggested that a short Q&A period be held at the end of each session to ask questions that were not brought up naturally.

Some challenges were identified with the remote instructional format by both participants and facilitators. Facilitators reported some difficulty with providing demonstrations of the technology (i.e., pointing to parts of the VR camera over a webcam). Some (20%, 1/5) pairs had technical difficulties with their Yi 360° VR Camera’s audio function, which was rectified by the facilitators’ suggestion to reset the device parameters. Respondents had mixed (positive/neutral/negative) opinions regarding the: (1) helpfulness of the workbook, (2) ease of use for the 360° camera, and (3), ease of use for the Oculus Go VR HMD. Most participants found the VR camera easier to use than the HMD.

Facilitators identified unique gaps and recommendations regarding equipment for this workshop. For example, it was identified that a form of instant text communication (e.g., Google Hangouts) would be useful to address shared questions and potentially create a stronger sense of community within the cohort. This strategy was successfully implemented mid-way through the workshop. Facilitators also noted digital storage space as an important consideration, and that a large, dedicated storage folder (e.g., Google Drive) was necessary to hold the shared video and audio files. As the number of files will be larger when hosting multiple workshops in the future, the facilitators recommend reminding participants to download and save files they may want to keep. This way, facilitators can clear all ‘work-in-progress’ files and store only the final VRCHIVE projects in the designated folder.

In terms of equipment loaning, getting the equipment packages ready was a unique experience for the Toronto Public Library. Unfortunately, participants were not able to return the equipment for an extended period due to the library’s COVID-19 public health measures. Some reported frustration that they incurred late fees (which were of course removed from their records) and concern about added care and responsibility. Nevertheless, the process ran smoothly after new protocols were designed. As this type of public health measure may continue for some time, facilitators should help to establish clear expectations regarding equipment borrowing and cleaning to ease participant concerns.

Participant outcomes

Survey respondents were satisfied with the VRCHIVE workshop, with all (100%, 3/3) rating their overall satisfaction 4 out of a possible 5, with 5 being the ‘most satisfied.’ Participants also reported that the workshop tended to make them feel: (1) less isolated (66.7%, 2/3 survey; 50%, 1/2 interview), (2) more connected with other people (66.7%, 2/3 survey; 100%, 2/2 interview), and (3) more confident in learning to use new technology (66.7%, 2/3 survey; 100%, 2/2 interview). No participants (0%, 0/5) reported negative impacts of the workshop on their feelings of isolation, connectedness to other people, or confidence in learning technology.

Relationship strengthening & connection to others

Interviewed participants reported learning more about their grandparent or grandchild. For example, one grandchild mentioned, ‘I learned more about how, like, how her life was before, like, for example, like when polio was around, I didn’t know about that.’ Likewise, one grandparent reported, ‘I think I discovered a little bit more of [my grandchild] and what [their] interests were and what [their] likes are. [My grandchild] made all the difference … I’m just [their] grandparent. I’m around all the time. And he’s used to that, but having other people, having different ideas, and doing different stuff, you know, just opens up … ’

The workshop also allowed participants to reflect on the pandemic: ‘It certainly got both of us to think a little bit more about the impact of COVID-19 on our lives.’ Notably, when asked about their experience watching other participants’ films, one grandparent spontaneously reflected on other uses for VR in understanding others’ perspectives such as playing basketball in a wheelchair or attending an Indigenous ceremony: ‘You know what’s fascinating about VR right, is your ability to really capture people’s experiences in a very different holistic sort of way […] it gives you a different perspective […] I can see how it could be used to get people to sort of understand how other people are living or doing things […] you’re right in the middle of it and you can see it from 360°degrees […]’

In terms of forming connections with others outside their family, interviewed participants reported that it was more difficult to connect with others online rather than in person, although they were ‘still able to know everyone somewhat.’ Still, many expressed a desire to stay connected with each other, and the grandchildren in the group were observed to interact socially with each other during the sessions. When asked about the workshop’s impact on their feelings of loneliness during COVID-19, the interviewed grandchild agreed that the workshop had had an impact, while the interviewed grandparent did not, reporting that loneliness had not been much of an issue for them.

Learning new technology

Overall, survey respondents found the VRCHIVE workshop more challenging (66.7%, 2/3) and fun (66.7%, 2/3) compared to other publicly run workshops (e.g., through the Toronto Public Library or a community centre/YMCA). When asked about access to novel equipment like the VR HMDs, most respondents agreed that they would not have had the opportunity to use VR equipment if it were not for this workshop. Additionally, one grandparent reported that they were excited to create more VR films.

All interviewed participants both reported an increased level of comfort with the technology, as well as surprise at the ease of use of the VR equipment. For example, one grandparent stated, ‘Well, I don’t know technology […] And certainly, this made me feel much more comfortable […] I had no idea that the VR camera was this accessible and useful … if it had not been for this course, I wouldn’t have known how accessible it is, how easy it is to use.’ Similarly, one grandchild reported, ‘I thought it was going to be kind of hard because I’ve never really done it before […] but I noticed I managed pretty well. I was able to figure out stuff by myself without – and I didn’t expect it to be like that.’Participants reported feelings of motivation while learning to use the VR equipment due to the weekly workshop format: ‘Because it was a course, because [it was] every week, […] it encouraged us to see if we could fix [the camera] because we had to meet the next deadline, the next class, to give us something to work towards. If there hadn’t been the class I might not have bothered.’

Discussion

VRCHIVE project strengths

The global VR industry is predicted to more than double size from 2021 to 2024 (Alsop, Citation2021) and yet the typical VR consumer is still young, male, and uses the technology for gaming (Stevanovic, Citation2019). A unique strength of VRCHIVE was its ability to provide free access to cutting-edge technologies that allowed intergenerational pairs with no previous experience to create 360° films in a short period of time. The successful completion of all five VRCHIVE films, in addition to the experiences of the facilitators and feedback from participants, affirm that it is possible to run a remote workshop where intergenerational pairs of participants are taught to create VR films. Overall, participants were quite satisfied with the workshop. This pilot program demonstrated success in making participants feel more confident in learning to use new technology and more connected with other people, as well as less isolated for those experiencing loneliness due to the COVID-19. Both facilitators and participants confirmed enjoying the workshop sessions.

The authors were able to provide a detailed account of the program’s structure to serve as a model should other localities wish to implement similar programming, as well as identify solutions for several challenges and gaps related to teaching intergenerational pairs in a virtual environment. As this was the pilot iteration of the program, many initial program shortcomings can now be easily rectified, for instance, the lack of previous examples to share with participants. The most significant changes that will be implemented in future iterations of the workshop will be: (1) extending the workshop’s length by one week, (2) dedicating more time to training participants how to use the technology, and (3) designing more effective instructions to complement the in-session training (e.g., provide step-by-step video instructions participants can watch later, a filming tip sheet). Many other recommendations were iteratively implemented during this November 2020 workshop, such as weekly e-mail ‘wrap-ups’ that reminded participants about what they learned, addressed questions that were raised, and provided reminders about homework due the following week.

The program also allowed strangers to share their pandemic experiences and helped participant pairs to learn more about each other and find commonalities among both younger and older generations (e.g., reflecting on similarities between the Polio epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic). Overall, the program was successful in meeting its objectives to increase virtual social opportunities, and in cultivating older adults’ ability to fully participate in modern society (Hughes et al., Citation2017; Martinez-Alcala et al., Citation2018).

Challenges and limitations

Conducting the VRCHIVE workshop remotely during the context of COVID-19 instead of in the library was both a challenge and an opportunity. First, providing instructional training for equipment remotely was difficult when demonstrating actions (e.g., pushing a small button on the VR HMD) through a webcam with poor resolution. Although dedicating more time to training participants on the technology and creating the step-by-step video instructions described above could help to mitigate this issue, the facilitators felt that a hybrid program format would be ideal once social distancing measures are lifted. Delivering the program virtually with an in-person component for hands-on equipment training or a drop-in ‘office hour’ at the library could be the optimal way to offer the convenience of participating from home as well as adequate support for learning the technology.

Second, the interaction between participants became ‘impossible’ in two cases due to one grandchild needing to self-isolate due to exposure to the virus and the ‘stay at home order’ put in place halfway through the workshop. These two participants devised creative solutions to complete their films, though in the case of the grandchild who had to self-isolate, his grandmother was not able to be part of the film. Unfortunately, the grandparents did not attend the workshop sessions once they could no longer see their grandchild in person, and the reason why the grandparents did not attend is unknown to the authors. All participants were asked to confirm that they had access to a device and a connection to the internet before the start of the program. It is possible that the grandparents were not comfortable accessing the online workshop without assistance, or that they were relying on using their grandchild’s device for video conferencing sessions.

A key takeaway is that workshop facilitators should consider planning for proactive skills assessment, support, and follow-up for participants needing assistance with accessing either the video conferencing platform or a device capable of video conferencing. Martínez-Alcalá et al. (Citation2021) found higher drop-out rates for seniors attending remote digital skills workshops during the pandemic compared to hybrid (online and in-person) workshops and that spending time to assess participants’ technical skills is a strategy that may help to improve participation. Further, in regions where COVID-19 remains a threat and social distancing restrictions are in place, VRCHIVE participant pairs should be a part of the same household since the filming task requires participant pairs to meet each other in person.

The small sample size, low response rate, and use of anonymous questionnaires in this pilot project are important limitations to consider, particularly as they pertain to understanding the workshop’s impact on participants’ feelings of isolation and connectedness. It is unknown which participant pairs are represented in the survey results, and it also is not possible to draw conclusions from this small sample on any systematic differences between the grandparents and grandchildren in terms of their learning experience or the impact of the workshop. The low response rate did not come unexpected, as eliciting feedback in this sort of workshop can be a challenge in general. Nonetheless, informal facilitator observations of participant engagement with the workshop were in line with participant responses regarding their satisfaction with the workshop, demonstrating that the workshop demonstrated feasibility. Lastly, the study was not designed in a way to determine whether VRCHIVE’s use of immersive storytelling holds an advantage over non-immersive digital storytelling activities or other similar existing library programming.

Future directions

The next steps for this program would be to run more workshops and implement recommendations where possible. For example, resources should be improved by adding informational pages to the workbook and digitizing them for online accessibility. For the program to be sustainable and scalable to a greater number of participants, the current OpenLab facilitators would need to train Toronto Public Library staff to conduct the workshop independently. Running the program would likely require two roles: (1) one staff member to manage the technology distribution and training, and (2) another to guide storytelling efforts. Alternatively, where public health guidance permits, this workshop could be conducted as an in-person or hybrid program at select library branches, with multiple workshops taking place each year. In-person components of the program could ease the facilitation of interpersonal connections and, notably, offer hands-on equipment training. Another programming possibility that could be worth exploring for its potential to enhance interpersonal connections would be for the Toronto Public Library to form a VR ‘club’ where people of all ages would routinely meet to learn and discuss 360° filmmaking.

Data collected through post-workshop questionnaires and interviews from future implementations of the workshop will serve to provide a more detailed account of the program’s impact, strengths, and areas for improvement. Participant outcomes such as relationship strengthening, social connectedness, and technology literacy, and differences in workshop outcomes between generations, could be systematically measured through pre- and post-program testing using standardized measures. For example, the System Usability Scale (Brooke, Citation1996) is a widely used and versatile 10-item tool that could be implemented to better understand VRCHIVE’s impact on participant comfort with technology or serve as a benchmark to measure the impact of any changes in equipment or teaching strategy.

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the VRCHIVE workshop could be a valuable tool in sharing perspectives and giving a voice to seniors in underrepresented communities who face barriers accessing such technology, an idea echoed by one interview respondent. Future VRCHIVE workshops may take on specific themes, such as Indigenous perspectives on living in Toronto, first and second-generation immigrant family experiences, or the realities of caring for a loved one with dementia. These topics will serve to shed light on voices or experiences that have been historically underrepresented in our cultural narratives.

Conclusion

The VRCHIVE workshop was the first-of-its-kind at attempting to co-create VR experiences with intergenerational pairs of participants, reflecting on their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the program can be seen as a success, holding great potential to increase digital participation and psychosocial outcomes for seniors. This workshop allowed participants to strengthen existing bonds with their families while making new connections in the broader community without compromising their safety in relation to COVID-19. Due to the success of the first workshop, the team plans to build a packaged program that can be hosted online by Toronto Public Library for future implementations. The VR memory-capsule films created during the workshop are viewable on the program website and will serve as a living, growing, cultural artifact of Toronto experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Vladislav Luchnikov for editing all the participant VRCHIVE films. We would like to acknowledge the Toronto Public Library and the Center for Aging + Brain Health Innovation for their generosity in supporting this proof-of-concept initiative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alsop, T. (2021). Virtual reality (VR) - Statistics and facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/2532/virtual-reality-vr/

- Appel, L., Peisachovich, E., & Sinclair, D. (2021). CVRriculum Program: Outcomes from an Exploratory Pilot Program Incorporating Virtual Reality Technology into Existing Curricula and Evaluating its Impact on Empathy-Building and Experiential Education Opportunities. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 16(1). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=8571

- Bertrand, P., Guegan, J., Robieux, L., McCall, C. A., & Zenasni, F. (2018). Learning empathy through virtual reality: Multiple strategies for training empathy-related abilities using body ownership illusions in embodied virtual reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 5, 26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00026

- Brooke, J. (1996). SUS - A quick and dirty usability scale. In P. W. Jordan, B. Thomas, B. A. Weerdmeester, & I. L. McClelland (Eds.), Usability evaluation in industry (pp. 189–194). Taylor & Francis. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319394819_SUS_–_a_quick_and_dirty_usability_scale

- Caroll, M., & Reynolds, S. (2014). “There and back again”: Reimagining the public library in the twenty-first century. Johns Hopkins University Press, 62(3), 581–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2014.0003

- Chen, A., Ge, S., Cho, S., Teng, A., Chu, F., Demiris, G., & Zaslavsky, O. (2020). Reactions to COVID-19, information and technology use, and social connectedness among older adults with pre-frailty and frailty. Geriatric Nursing, 42(1), 188–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.08.001

- Cipresso, P., Giglioli, I., Raya, M., & Riva, G. (2018). The past, present, and future of virtual and augmented reality research: A network and cluster analysis of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2086. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02086

- Daly, J. R., Depp, C., Graham, S. A., Jeste, D. V., Ho-Cheol, K., Lee, E. E., & Nebeker, C. (2021). Health impacts of the stay-at-home order on community-dwelling older adults and how technologies may help: Focus group study. JMIR Aging, 4(1), e25779. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/25779

- Freeman, S., Marston, H. R., Olynick, J., Musselwhite, C., Kulczycki, C., Genoe, R., & Xiong, B. (2020). Intergenerational effects on the impacts of technology use in later life: Insights from an international., multi-site study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5711. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165711

- Freeman, S., Martin, J., Nash, C., Hausknecht, S., & Skinner, K. (2019). Use of a digital storytelling workshop to foster development of intergenerational relationships and preserve culture with the Nak’azdli First Nation: Findings from the Nak’azdli Lha’hutit’en Project. The Canadian Journal on Aging, 39(2), 284–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980819000588

- Google. (n.d.). [Map of Toronto]. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.google.ca/maps

- Hausknecht, S., Vanchu-Orosco, M., & Kaufman, D. (2017). Sharing life stories: Design and evaluation of a digital storytelling workshop for older adults. In G. Costagliola, J. Uhomoibhi, S. Zvacek, & B. McLaren (Eds.), CSEDU 2016. Communications in computer and information science (pp. 739). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63184-4_26

- Hausknecht, S., Vanchu-Orosco, M., & Kaufman, D. (2018). Digitising the wisdom of our elders: Connectedness through digital storytelling. Ageing and Society, 39(12), 2714–2734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000739

- Herron, R., Newall, N., Lawrence, B., Ramsey, D., Waddell, C., & Dauphinais, J. (2021). Conversations in times of isolation: Exploring rural-dwelling older adults’ experiences of isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063028

- Hewson, J., Danbrook, C., & Sieppert, J. (2015). Engaging post-secondary students and older adults in an intergenerational digital storytelling course. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 8(3), 135–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19030/CIER.V8I3.9345

- Hughes, S., Warren-Norton, K., Spadafora, P., & Tsotsos, L. (2017). Supporting optimal aging through the innovative use of virtual reality technology. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 1(4), 23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/mti1040023

- Iizuka, A., Suzuki, H., Ogawa, S., Takahashi, T., Murayama, S., Kobayashi, M., & Fujiwara, Y. (2020). Association between the frequency of daily intellectual activities and cognitive domains: A cross‐sectional study in older adults with complaints of forgetfulness. Brain and Behavior, 11(1), e01923. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1923

- Kaimal, G., Carroll-Haskins, K., Ramakrishnan, A., Magsamen, S., Arslanbek, A., & Herres, J. (2020). Outcomes of visual self-expression in virtual reality on psychosocial well-being with the inclusion of a fragrance stimulus: A pilot mixed-methods study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 589461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589461

- Leedahl, S. N., Brasher, M. S., Estus, E., Breck, B. M., Dennis, C. B., & Clark, S. C. (2018). Implementing an interdisciplinary intergenerational program using the Cyber Seniors® reverse mentoring model within higher education. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40 (1), 71–89. PMID: https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2018.1428574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2018.1428574

- Loe, M. (2013). The digital life history project: Intergenerational collaborative research. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 34(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2012.718013

- Ma, Q., Chan, A. H. S., & Teh, P. (2020). Bridging the digital divide for older adults via observational training: Effects of model identity from a generational perspective. Sustainability, 12(11), 4555. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114555

- Martinez-Alcala, C., Rosales-Lagarde, A., Alonso-Lavernia, M., Ramirez-Salvador, J., Jimenez-Rodriguez, B., Cepeda-Rebollar, R., Lopez-Noguerola, J., Bautista-Diaz, M., & Agis-Juarez, R. (2018). Digital inclusion in older adults: A comparison between face-to-face and blended digital literacy workshops. Front ICT, 5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fict.2018.00021

- Martínez-Alcalá, C. I., Rosales-Lagarde, A., Pérez-Pérez, Y. M., Lopez-Noguerola, J. S., Bautista-Díaz, M. L., & Agis-Juarez, R. A. (2021). The effects of Covid-19 on the digital literacy of the elderly: Norms for digital inclusion. Frontiers in Education, 6, 245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.716025

- Norris, P. (2002). The bridging and bonding role of online communities. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 7(3), 3–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X0200700301

- Pancani, L., Marinucci, M., Aureli, N., & Riva, P. (2020). Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1006 Italians under COVID-19 lockdown [Unpublished manuscript]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/uacfj

- Park, A. (2014). Do intergenerational activities do any good for older adults’ well-being?: A brief review. Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Research, 3(5), 181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-7182.1000181

- Peek, S. T., Wouters, E. J., Luijkx, K. G., & Vrijhoef, H. J. (2016). What it takes to successfully implement technology for aging in place: Focus groups with stakeholders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(5), e98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5253

- Perissinotto, C. M., Cenzer, S. I., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(14), 1078–1083. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

- Pew Research Center. (2017). Tech adoption climbs among older adults. https://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults

- Rueda, J., & Lara, F. (2020). Virtual reality and empathy enhancement: Ethical aspects. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 7, 506984. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2020.506984

- Sepulveda-Loyola, W., Rodriguez-Sanchez, I., Perez-Rodriguez, P., Ganz, F., Torralba, R., Oliveira, D., & Rodriguez-Manas, L. (2020). Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 24, 938–947. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7

- Sinan Zhong, Chanam Lee, Margaret J. Foster, & Jiahe Bian. (2020). Intergenerational communities: A systematic literature review of intergenerational interactions and older adults’ health-related outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 264, 113374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113374

- Stevanovic, I. (2019, December 4). 30 virtual reality statistics for 2020. Kommando Tech. https://kommandotech.com/statistics/virtual-reality-statistics/

- Sum, S., Mathews, M., Pourghasem, M., & Hughes, I. (2009). Internet use as a predictor of sense of community in older people. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2(2), 235–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0150

- Theriault, R., Olson, J. A., Kroll, S. A., & Raz, A. (2021). Body swapping with a Black person boosts empathy: Using virtual reality to embody another. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(12), 2057–2074. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/17470218211024826

- Toronto Public Library. (2019, October 30). Toronto public library’s strategic plan 2020-2024: Resilience, success and well-being for our city and its communities. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/content/about-the-library/pdfs/board/meetings/2019/oct30/07-strat-plan-2020-2024-combined-revised.pdf

- Ventura, S., Cardenas, G., Miragall, M., Riva, G., & Baños, R. (2021). How does it feel to be a woman victom of sexual harassment? The effect of 360°-video-based virtual reality on empathy and related variables. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking, 24(4), 258–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0209

- Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy, 5, 27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3

- Zak, P. (2013). How stories change the brain. Greater Good Magazine, University of California Berkeley, The Greater Good Science Center. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

Appendix

Table A1. Detailed workshop agenda

Appendix B.

Google Forms Screening Questions

E-Mail Address (open-ended)

Name of grandchild (open-ended)

Name of grandparent (open-ended)

Age of grandchild (open-ended)

Age of grandparent (open-ended)

What Toronto neighborhood do you live in? (open-ended)

Tells us: What made you excited about joining the workshop? (open-ended)

How would you rate your level of comfort with technology as a team? NOTE: This is not a barrier to join, we would just like to get an idea of the group. (Likert scale: 1 = very low, 5 = very high)

Have you ever seen a Virtual Reality video before? a) Yes b) No

Please confirm you have access to a computer/laptop. a) Yes b) No

Please confirm that you have internet connection. a) Yes b) No

Please confirm that you are able to pick up the VR equipment from a local library branch the week of Oct 26- October 30, 2020. a) Yes b) No

Please confirm that you are able to attend the weekly, online workshops on Wednesday in November from 4–5 pm and that you are also both willing to do ‘homework’ in-between classes such as writing and recording audio stories and shooting video scenes. *(Don’t worry – it’s fun homework) a) Yes b) No

Local library branch (open-ended)

Appendix C.

Post-Workshop Online Survey Questions

Appendix D.

Phone Interview Questions

What did you find most enjoyable about the workshop?

What did you find most challenging about the workshop?

Did attending the workshop make you feel more confident in learning how to use new technology?

What’s the most useful idea or skill that you think you’ll take away from the workshop?

Do you feel more connected to your family member as a result of attending the program together?

Did you learn anything new about your family member during the workshop?

Did you learn anything about yourself during the workshop?

How did you feel about watching the other participants’ films or the process of them making the films?

Did attending the workshop make you feel less lonely during COVID?

Did you feel a sense of community through the workshop?

Do you think the workshop experience may have been different if it was in person rather than online?

Do you have any feedback or suggestions about the workshop and how we should improve it for next time? More specifically, about:

equipment training

storytelling process

length of the classes

number of sessions

number of participants

facilitator support