ABSTRACT

A complex intervention called ‘participatory group-based care management’ was developed and carried out in Central and Eastern Finland to promote older adults’ wellbeing and quality of life. This study analyses the process of the intervention using two types of qualitative data. Firstly, during the six-month intervention, 120 reflection diaries in total were written by researchers and care managers, based on their observations of the group meetings. Secondly, 24 focus group discussions were carried out with the intervention participants. Both data were analyzed jointly by using the grounded theory method to evaluate the intervention process. Based on the data, three important elements of the intervention were social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings. These elements support older people in terms of social wellbeing, resources and capacity, experiences of meaningfulness, participation and routines, and empowerment. Contextual and intervening factors related to the intervention, group tutors, and participants, are essential for achieving outcomes. The three important elements of the intervention (social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings) appear to empower some older adults and engage some of them in activities. According to the results, the effectiveness of the intervention is based on socially and individually constructed causal pathways, but the intervention should be refined before its further implementation.

Introduction

Health and wellbeing promotion of older adults has become a key policy aim in many aging societies. Alongside traditional health promotion strategies, emphasis has been put on preventive and educative practices enhancing older people’s possibilities to maintain wellbeing and quality of life as community-dwellers. These practices may be especially relevant in addressing and preventing social problems, such as loneliness and social isolation in older age (Cattan et al., Citation2005; Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, Citation2015).

The present study undertakes a process evaluation of a group-based care management intervention in Finland. The intervention was originally designed to promote quality of life and wellbeing of older people living alone – a risk group for loneliness and other wellbeing deficits (Kharicha et al., Citation2007; Victor et al., Citation2005). The group-model was designed to be implemented within public elder care services with the help of care managers. In Finland, care management (as also referred to as case management) is the central service unit addressing non-health-specific needs of community-dwelling older people. Stemming from ‘aging in place’ policies (Sixsmith & Sixsmith, Citation2008), the main aim has been to support older people to live at home as long as possible. In practice, care management combines care and service coordination and individual work with the client. The care management process includes a comprehensive needs assessment and a personal care/service plan, which are regulated by legislation (The Social Welfare Act 1301/Citation2014; The Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Services for Older Persons 980/Citation2012).

Conceptually, care management refers to an individual working process (case management) with clients (Payne, Citation2000). Previous studies have shown that individually tailored care management processes and models do not improve older clients’ quality of life nearly at all (e.g. Fletcher et al., Citation2004; Godwin et al., Citation2016). However, some studies have found that care management practices have some potential to alleviate loneliness (Taube et al., Citation2018), as well as to increase social leisure activity (Granbom et al., Citation2017). Moreover, studies have indicated that different types of group-based social interventions can have positive effects on older people’s quality of life and wellbeing (e.g. Coll-Planas et al., Citation2017; Pynnönen et al., Citation2018; Saito et al. Citation2012).

Common features of successful interventions include adaptability, community participation and activities involving productive engagement (Gardiner et al., Citation2018). However, there is a lack of evidence concerning the effectiveness and the process of group-based care management services, but educational group interventions have proved to be effective at least in alleviating loneliness of older people (Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, Citation2015). The intervention examined in this study, ‘Participatory group-based care management,’ includes both educational (counseling) and grouping (social support) elements utilizing an inclusive and needs-based approach.

Overview of the complex intervention and the research project

In social care, most services and practice methods can be defined as complex interventions (Soydan, Citation2015), including services and programs of care/case management (Hudon et al., Citation2020). Complex interventions are described as interventions that contain several interacting components. In addition, complexity refers to the behaviors of receivers and deliverers, the variability of outcomes, the flexibility of carrying out the intervention and the number of groups or organizational levels targeted by the intervention (Craig et al., Citation2013; Skivington et al., Citation2021). Participatory group-based care management includes several components and deliverers and can be tailored to a specific group, which meets the definition of a complex intervention.

The intervention was developed and piloted in Central and Eastern Finland during 2017–2018 as part of a national consortium project Inclusive Promotion of Health and Wellbeing (PROMEQ, 2016–2019). The aim of the intervention was to enhance community-dwelling older people’s quality of life and wellbeing using a participatory and needs-based approach, and to address their social and service-related needs. The intervention was designed together with local health and social care professionals based on focus group discussions with representatives of the target group (Tiilikainen et al., Citation2019). The target group of the intervention was set at the beginning of the project: older adults (+65) who live alone and experience some form of health or wellbeing challenges, but who otherwise manage mainly well in their daily activities. A mixed method randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 392 participants (intervention group n = 185, control group n = 207) was conducted to examine the effectiveness and the process of the intervention. Participants were recruited via multiple channels, such as care management units, health care centers, pharmacies, and newspapers. Participants were randomly selected either to intervention group or control group.

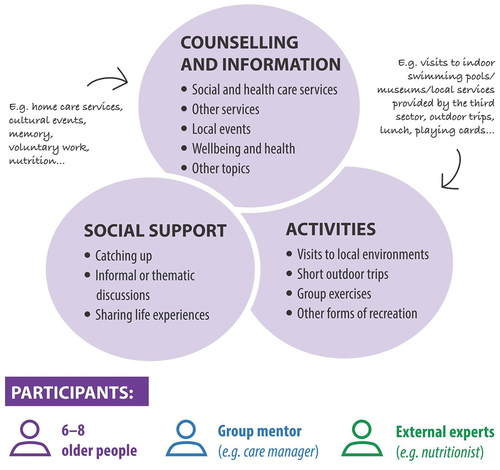

During the research project, 24 intervention groups were organized, and six to eight older people attended each closed group meeting (except for one group with nine participants). The groups remain the same during the intervention, but all participants did not attend all the group meetings. The duration of the intervention was six months including five, two- to three-hour tutored meetings. The older people were also encouraged to meet each other outside the organized group meetings. A total of 13 care managers and nine researchers were involved in tutoring the intervention groups. Any formal training for those who tutored the intervention was not organized, but all tutors were experienced with older persons and they had informal reflectional discussions with each other and with research group regarding the intervention. The content of the group meetings was planned together with the participants. The intervention consisted of social support, counseling and information, and activities (). The themes and content of the meetings varied between the 24 intervention groups depending on the needs of the participants.

In the intervention (see also Ristolainen et al., Citation2020), social support refers to the possibility to share life experiences and socially interact with others. Counselling includes information and discussions concerning social and health services (e.g. home care), other services (e.g. physical training services), local events (e.g. concerts, open lectures), health and wellbeing (e.g. nutrition, memory), and other topics (e.g. voluntary work, security). Counselling and information were provided by care managers and other specialists (e.g. dietician, third-sector coordinator) using a dialogical and reciprocal approach. Activities included visits (e.g. swimming hall, museums, library), outdoor gatherings, group exercises, and other recreation (e.g. having lunch together, playing board games) and were intended to support participation in the local environment. The research project covered costs for the activities and provided transportation for older people if needed.

Data were collected by surveys, focus group interviews and observation. The study design, trial profile and quantitative results of the RCT are reported in detail elsewhere. The primary outcome of the RCT was quality of life, measured by the WHOQOL-BREF measure (WHO Citation1996). The instrument is based on WHO’s definition of quality of life, which includes four dimensions: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. According to the results of the RCT, the intervention has no effects on quality of life, but some minor effects were found on loneliness, institutional trust, and trust in other people among certain subgroups of the participants (Ristolainen et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). This study uses the qualitative datasets collected during the trial and adds to the previous knowledge of participatory group-based care management and its effects.

Aim of the study

This study evaluates the process of participatory group-based care management in its pilot phase. Process evaluation focuses traditionally on assessing the adequacy of a program or intervention by exploring its implementation (Rossi et al., Citation2004). The process evaluation of a complex intervention can focus on various aspects, such as the context, implementation, and mechanisms of the impacts (Moore et al., Citation2015). It can be done by using a single type of data or combining quantitative and qualitative data, which offers a more comprehensive understanding of complex interventions, especially in the context of social services (Blom & Morén, Citation2010; Moore et al., Citation2015). Process evaluation may be particularly relevant when evaluating novel complex interventions in their pilot phase (Craig et al., Citation2013) and as part of trial designs (Skivington et al., Citation2021).

The process evaluation is carried out using the qualitative data collected during a mixed-method RCT. The data includes reflective diaries (written by the researchers and care managers) and focus group discussions with older people who participated in the intervention. The data is analyzed using a paradigm model based on grounded theory (see Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998), which has previously been used in some intervention studies (e.g. Palese et al., Citation2013; Wolford & Holtrop, Citation2020). In addition to formative process evaluation (Rossi et al., Citation2004), a summative perspective is included by examining the perceived outcomes of the group-based care management. In this study, we do not use a specific measure, which means that we do not define the outcomes in advance, but we investigate the process and outcomes of the intervention from a data-driven perspective. The aim of this study is to gain more understanding of the effectiveness of the intervention by clarifying the causal pathways related to the outcomes. The research questions are:

What are the most important elements of the intervention?

What are the perceived and observed outcomes of the intervention?

What kinds of contextual and intervening factors are associated with the perceived and observed outcomes of the intervention?

Methods

Sample

The sample of this study consists of participants in the intervention group (n = 185). Altogether 140 of them were present at the last group meeting, during which the data was collected by focus-group discussions. To collect data also from the absent participants, researchers telephoned those who did not attend the focus group discussions and went through the same questions individually.

Most participants lived alone at the home independently or with low-level support services such as safety phone or meal services, while a few participants (n = 7) used regular home care services. The age of the participants varied between 62 and 94 years, but only one person was under 65 years old. Most of the participants were women (82.2%).

Data

The data consist of 120 reflective diaries, 24 focus group discussions, and about 10 individual interviews with the participants who were not present in the focus group discussion. The semi-structured reflective diaries were written after each group meeting, based on the observations and notes made by researchers and care managers. The reflective diaries included information on the content of the meetings as well as observations regarding the interaction of the group, for example. Participants were also asked to provide feedback about the last meeting, which was written down in the diaries. The length of the reflective diaries varied from two to four pages.

Focus group discussions with the participants were carried out in the last group meeting. The discussion themes included participants’ experiences related to the outcomes and evaluation of the intervention and the development of the intervention. The duration of the focus group discussions was between 30 − 60 minutes. Focus group discussions were recorded and partly transcribed. Notes from the individual interviews were combined with the data from the focus group discussions.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using grounded theory, which offers a systematic and inductive way to derive theory from a complex phenomenon (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). By using grounded theory, the intervention can be examined in a more comprehensive manner: not just by focusing on the outcomes and factors impacting them, but by also exploring the reasons why these outcomes and processes appear. In this study, the theory derived from the data analysis refers to the causal pathways of the intervention and essential conditions related to it.

Both data types (reflective diaries and focus group discussions or individual interviews) were used simultaneously and synthesized during the analysis process regarding those aspects that were relevant to the purpose of the study. Open coding was used in the first phase of the analysis to explore excerpts connected with the phenomenon of the effectiveness of the intervention. Through open coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998), any signs of effects or changes on/in wellbeing of older people were sought. In addition, all expressions referring to benefits or disadvantages of group meetings were considered. The expressions and longer text sections were simplified and classified into categories. Simultaneous with open coding, axial coding was performed to determine connective categories.

In the second phase of the analysis, the categories were re-arranged to explore the important elements and contextual factors related to the effectiveness of the intervention. Both axial and selective coding were used for analyzing the data to address the aim of the study (Kelle, Citation2007). Compared with the first phase of the analysis, some categories were renamed, and some new subcategories were formulated.

The paradigm model (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) was applied during the axial and selective coding by utilizing the definitions developed for intervention research (Creamer, Citation2018). The paradigm model consists of causal conditions, phenomenon, strategies, consequences, and contextual and intervening conditions. In this study, causal conditions (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) are the knowledge of how the intervention was carried out, as well as what the client´s wellbeing and needs are at the beginning of the intervention. The phenomenon here refers to the ability of the intervention to generate desired outcomes. All other components of the paradigm model stand for the phenomenon (see Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). The analysis focuses on strategies, consequences, and contextual and intervening conditions as described in by acknowledging the previously known causal conditions. During axial coding, it was considered how categories interact over time and relate to one another. Selective coding made up a phase where the components of the paradigm model were summarized and relations between different categories were analyzed in detail (see Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998).

Table 1. Use of paradigm model components in this study (applying Creamer, Citation2018; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998).

The data was initially coded by one researcher, but the codes and the course of analysis were discussed in depth several times by the research group.

Results

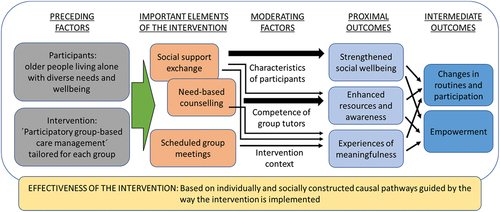

The analysis resulted in findings regarding the important elements of the intervention, outcomes, and contextual and intervening conditions (). Three important elements of the intervention were identified: social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings. The perceived outcomes were found to be both proximal and intermediate outcomes. Proximal outcomes are immediate, meaning that something is happening during or immediately after the group meeting, whilst intermediate (or distal) outcomes follow the proximal ones (see Rossi et al., Citation2004). A better understanding of causal pathways is gained by exploring both proximal and intermediate outcomes. Factors and conditions moderating the effectiveness of the intervention were related to the context of the intervention, characteristics of the participants, and the competence of group tutors. The existing understanding refers to the knowledge of both the intervention and participants.

Table 2. The main categories and sub-categories according to the paradigm model components.

The excerpts shown in the next sections are identified with the following codes. ‘G’ refers to a group, and the following number refers to the number of the intervention sub-group. ‘D’ refers to a diary, and the following number to the number of the group meeting. The code ‘FG’ refers to a focus group discussion with detailed numbers for each intervention sub-group.

STRATEGIES: important elements of the intervention

Social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings were found to be important elements of the intervention.

Social support exchange consists of three sub-categories: social contacts, reciprocal peer support and discussions, which were all regarded as meaningful for the participants. Social contacts the older people engaged in while participating in the intervention were important to them. They said that it was nice to meet and get to know other people in the same age group. Some participants arrived together in shared rides to the meetings. Secondly, the older people valued reciprocal peer support with others as very important. Both receiving support and sharing experiences and support for other group members emerged when discussing the benefits of the intervention. Peer support was observed to be happening continuously during the group meetings, including, e.g. emotional support, such as showing compassion, and encouraging each other in various matters such as asking for help when needed. The third sub-category was discussions: for some older people it was important to just talk with someone or listen to various views and stories.

Friends have all passed on, so for one as an individual it just feels like it’s nice to see people in the group. You don’t really need anything else. G17D4

It’s been really comforting to notice – as everyone “curls up” in their own ailments – that when you come here and the talk begins, oh I have osteoarthritis too and I have an artificial hip and… You get that peer-support. Your own problems feel a lot smaller then. FG18

Yeah, so, this group thing… It’s been really important… at least to me… Like you get to meet others and chat and talk about your own life experiences if you want (laughter)… FG22

Needs-based counseling refers to two sub-categories: shared knowledge and information gained during the intervention, and individual counseling offered when needed. In terms of shared knowledge and information, the older people related that they received useful information through counseling from group tutors and other specialists, as well as between group members. Knowledge-sharing was also observed in the group meetings. In addition, visits to local environments were perceived as interesting and useful. Within the intervention, some older people received individual counseling from the care manager if needed. Individual counseling included more detailed information, for example on how to apply for specific services.

There seemed to be a need for concrete information and the group members felt that it was really meaningful that we went through the housing services together. G14D3

The care manager mentioned several tips and different options for seeking help in health-related matters. The care manager also reminded that the service center provides needs assessment, that the service guide provides telephone numbers for physiotherapists, and about the option to apply for psychiatric rehabilitation at home. G9D5

The category of scheduled group meetings includes two sub-categories that emerged from the participants’ expressions describing the meetings as awaited events that made them go outside of home for meetings. Having these scheduled meetings in the calendar and going to them regularly during the intervention were seen as positive new things in their daily routines by most of the participants.

The meetings were really looked forward to. Time was always found for them if at all possible. FG18

… I’ve been able to be here and get away from home. That’s the most important when you’re alone. Like you’ve always got somewhere to go. Pretty good. And others also mentioned that when there’s somewhere to go, well you get out of the house and don’t end up staying there on your own. FG19

CONSEQUENCES: proximal outcomes

The main categories of proximal outcomes are strengthened social wellbeing, enhanced resources and awareness, and experiences of meaningfulness.

Strengthened social wellbeing consists of two sub-categories: continuity of social contacts and sense of togetherness, which are highly connected to social support as one of the key elements of the intervention. Continuity of social contacts was both observed during the meetings and reported by older people. Participants gained new social contacts, which will be maintained in the future, too. Some expressed having closer relationships. In addition, some participants contacted each other outside group meetings. The aspect of a sense of togetherness came up especially when participants spoke of their experiences as being members of the group. Sense of togetherness was connected both to belonging to a group and being together as well as to talking with people of a similar age and with similar life situations. The group tutors observed a so-called ‘good team spirit’ in the meetings and a sense of sadness when the intervention ended.

This person with a broken leg asked a person who knew about information technology if they’d help them with some computer things. They agreed a meeting at the home of the person with a broken leg… G15D4

This kind of togetherness… Like you get to be together to think about these issues… They’re the kinds of things… everyone experiences at some point. FG20

The category of enhanced resources and awareness includes three sub-categories: increased awareness of services, activities etc., continuity of support and services, as well as motivation and new perspectives. Categories are strongly connected to the information that older people received during the intervention. Increased awareness of services, activities etc. refers to important, relieving, useful, current, and interesting information about services, wellbeing, and local environments and possibilities. Participants were satisfied because they now knew who or where to contact if they need help or support. Some study participants reported sharing information outside the group with others in need. Continuity of support and services, referring to the support and services that participants were advised to apply for or become familiar with, was also identified.

One [person] waited to get the info and was happy with the information they got, and they’ve made use of it, e.g. in organizing a home visit with a physiotherapist through the service center and found that helpful. FG13

They’ve also got lots of information about different opportunities from other participants, e.g. about what Carers Finland does. And then they’ve passed this info on to friends and acquaintances. FG10

Through counseling and peer support the participants felt that they were experiencing motivation and new perspectives. Some noted that they gained motivation from other group members to improve their health and wellbeing. New perspectives were mainly connected to how they perceive and think about their own lives, while some participants reported gaining different kinds of advice and tips for their daily life and routines. These were related, for example, to problem-solving and saving money.

I forgot that… that you’ve got to take care of yourself… It’s not necessarily come from here, but this has… been the inspiration…. when [I have] listened to what others are doing… G21D3

Experiences of meaningfulness is based on three sub-categories: variation in daily routines, positive experiences and feelings, and sharing knowledge with those in need outside the group. Participating in the group meetings brought variation in daily routines. Many of the participants related that they would not have participated in similar activities alone, or that it would not have been possible to access certain places or activities without the organized group meetings. For some participants, the group meetings were valuable because of the activities carried out in the meetings, which provided important variety for their daily life at home.

The person being cared for [by a relative] lives at a different address to the group member. Every time, this group member mentions how important these meetings are to them, a break from the everyday strains and a chance to breathe. Now, they’ve also got a daughter living far away who’s got a serious long-term illness, and that’s causing concern. G12D5

Participants described positive experiences and feelings concerning the group meetings. They reported that meetings were enjoyable, rewarding, and entertaining and that they gained nice memories. Some participants said that they experienced being respected during the intervention. In addition, they shared what they considered to be new and useful information outside the group to friends and relatives. The participants were satisfied that they could share knowledge with those in need outside the group.

It feels good to have a certain kind of appreciation, like that we are being listened to and they’re asking us things. FG7

I think these have been important for me, in the sense that I’ve got … these … other old … a bit older [friends] … so I, I’ve been able to be in touch with them from here [the group]. FG20

CONSEQUENCES: intermediate outcomes

The main categories of intermediate outcomes were changes in routines and participation, and empowerment.

The changes in routines and participation includes three sub-categories: more active at leaving home and participating in events; new hobbies and activities; and some changes in health-related behavior. Some participants directly reported the first sub-category, and this was also perceived through observation during the group meetings when participants talked about their recent activities and life events. For some of the older people, participating in e.g. a cultural café or registering for volunteer education were clearly connected to the information gained from group meetings or visits made during the intervention. The intervention also encouraged some participants to be socially active, for example by inviting neighbors for a visit or asking for company when attending public events. In addition, there were some mentions regarding new hobbies and activities, as well as changes in health-related behavior. Some of the participants had started or planned to start a hobby, such as going to the gym. Some reported that they have been walking and exercising more on a daily basis. A few participants said that they have considered changing their nutritional habits.

At coffee we talked about the last theater visit and about going to the theater. One member of the group (who moved from somewhere else) had been inspired afterward to go out and watch a play and told that it was nice to go there because the place was already familiar, and you knew what was happening and where. G22D4

I’ve at least now got a three-month membership card for the gym. It used to be a really high threshold for me to go there. [But now] It’s been really good. I go there for an hour and a half during my trip to the shops. I’ve managed to get other older people to go there too. It’s kind of like, like I just thought that you need to be in good shape at any age. I’ve got a sort of motivation from this. It’s a new thing. FG10

It’s changed at least… like… now [I am] taking care of my own… health… and exercise… like when you hear… from others… that… when you lose the opportunity to exercise… well, it just collapses… There’s this sense of self-preservation… like you’ve gotta get moving… FG20

Empowerment as the category regarding the intermediate outcomes includes three sub-categories: feeling invigorated and strengthened, increased understanding of one’s own life situation, and providing for and trusting in the future. Participants expressed feeling invigorated and strengthened, for example in terms of being in a good mood and feeling refreshed after the meetings. Some participants related that the intervention had been a therapeutic experience and that they felt stronger than before. Through participating in the intervention, increased understanding of one’s own life situation was recognized. This was connected to the new perspectives participants obtained from the group regarding the perception of their own life situation. When listening to other participants’ life stories, some realized that they are managing quite well in their own lives.

It’s been terribly comforting to notice, too, that… like everyone has their own problems… and then when you come here and things start going like… “Oh yeah, I’ve also got osteoarthritis in my wrists, and I also have an artificial hip and … ” For me it’s the … you get that peer support … Somehow you feel much less bothered about your own problems after that … FG18

Like that I’ve been involved here, well I feel like completely different now that I’ve… heard some sensible things… and been here with You… and like I haven’t quite yet slipped into old age after all… And just that… I feel quite … positive… about myself… FG23

The focus group discussions indicated that some of the participants were providing for and trusting in the future more after the intervention because they had received information on social and health care services. Participants stated that they feel more secure when considering their future or that they are more confident about what will happen when they need more support to manage their daily living at home. Information on where to contact for advice or support was found to be especially important and created a sense of security. In addition, for some older people trust in the future was related to understanding that it is possible to cope because others are doing so despite their decreased functional ability.

That kind of feeling of being safe and secure. Like, ok, if something happens, well I can contact here or go there… FG17

I’ve gotten information and… the physical stuff too… like you… some of you use rollators and poor old me hasn’t got anything yet… It’s been useful to see that people can do that… Like I’m always really scared about… like… what about when you’ve got to start using a rollator? FG11

CONTEXTUAL and INTERVENING CONDITIONS: moderating factors and conditions

Contextual and intervening conditions were related to the intervention context, characteristics of the participants and the competence of the group tutors.

The essential conditions of the intervention context connected with the effectiveness of the intervention consist of three sub-categories: planning and accessibility, group structure and scheduling, and environment, place, and atmosphere. The sub-category planning and accessibility includes the preparation of the meetings and ensuring that participants can reach the meeting place. Care managers and study participants argued that group tutors should plan the course of the meeting beforehand and assist participants in deciding the content of upcoming meetings. In some intervention groups, the older people indicated that the time for informal discussions was too short. Moreover, the study participants reported that group tutors sometimes supported them in getting to the meetings, for example by offering a ride or giving them a motivation phone call, and that they could not have participated in the meetings without help.

One of the female group members who got a ride with the leader pointed out that she might not have gone to the group meeting if she hadn’t been encouraged by the leader and her own son, and the leader offering them a ride. G7D5

The group structure and scheduling were found to dilute the group process. Many participants reported that the meetings were too infrequent and too few and that they were therefore unable to get acquainted with each other or make closer friendships. For some, the intervention ended too early. About half of the groups (14/24) arranged a self-organized meeting after the intervention was completed. However, many groups lacked a person willing to take responsibility for convening a group meeting. Therefore, it was pointed out that continuity of group activities would require support from the group tutors. The group size was considered suitable particularly to support discussion, even for less vocal participants. In general, commitment to the group activities and meeting the group members several times was seen as an important aspect for group cohesion.

The third subcategory environment, place, and atmosphere is related to participation in the group. Firstly, it was more difficult to attend the meetings if the venues were not easy to reach. Secondly, during the group meetings, some of the participants could not follow the discussion if the room was too noisy. Instead, it was mentioned that an open, pleasant atmosphere, as well as good team spirit were important when acting and discussing in the group.

One would have liked meetings in-between the organized group meetings and was wondering if it would have required more effort to make extra meetings happen. Now it feels like every time you’ve got to re-orientate yourself to this group, but now it’s starting to feel like you’ve got to know [the group members]. G17D5

The atmosphere was again relaxed and friendly, but the place was not that favorable for catching up as there were other people around. In that way the round for sharing how everyone is doing and the general discussion were a bit more superficial than before. G14D4

According to the data, the diversity of the characteristics of participants influenced the effectiveness of the intervention in terms of three aspects: background and sociodemographic factors, functional ability and situation in life, and individual needs and personalities. The relevance of background and sociodemographic factors of the older people was somewhat emphasized in the data. The same age of group members was mentioned as important, although differences in age were experienced as significant for bringing out and sharing different views. Educational background or financial situation were not seen as important factors for the cohesion of the group. Similarities with respect to other background factors or aging-related issues between group members were found to be more important. According to the data, connective factors included e.g. remigration, disease, health problems, interests, or life experiences. By contrast, the sense of being an outsider was related to being different compared to other group members, e.g. one person had recently moved to a small town, while other members were previously familiar with each other.

The age differences haven’t been an issue because everyone is, after all, retired and living on their own. Common life experience is more important than age. FG24

Functional ability and situation in life was connected with participation in group activities as well as to the perceived benefits of the intervention. Some of the participants did not participate in the meetings if they had difficulties accessing the location due to their decreased mobility. When participating in the group, hearing loss or other functional problems excluded some participants from the discussions and complicated the course of the meeting. A difficult life situation, such as worries concerning friends, or other plans hindered participation. In contrast, some older people felt that the intervention was an important counterbalance for a difficult life situation. A few participants stated that they felt that they had been focusing too much on the difficult life situations of other participants.

Sometimes, there’s been a clash with the group work and some other activity (e.g. a seniors’ gym class). One of the participants had prioritized our group. FG11

The third category regarding the participant´s characteristics is individual needs and personalities. Some participants related that they received precise information or support for their needs, e.g. knowledge on how to manage with a sore knee, memory problems, or loneliness. On the other hand, some participants were disappointed because they felt that they did not get what they were hoping for from the intervention. In general, various needs and personalities were seen as a type of richness, but some contrary opinions were also raised. Some of the participants did not like loud or talkative individuals because they took space from others.

One of the group members particularly enjoyed our conversations. They’re a really social, talkative person who’s currently got far too few opportunities to be herself in this kind of way, and they say that this group offers them precisely the kinds of conversations that they’ve really missed. G23D4

Competence of group tutors includes two sub-categories: group tutoring skills and situational flexibility. Generally, the older people considered that the group tutors played a significant role in leading and supervising the intervention. Group tutoring skills were seen as important e.g. in terms of the group tutors taking the role of leader in the group, ensuring that everyone can participate in discussions and guiding the direction of the discussion when needed. Situational flexibility means that group tutors should notice the variation and individuality of the group members as well as respond to the different and suddenly surfacing needs of the participants.

Good preparation and planning content in advance is really important. With good planning, you can move forward and address the content as necessary. You don’t need to use everything you’ve planned, but a good sense of the situation is required. G12D2

Discussion

In the following we summarize how the intervention under study may work and what circumstances support its effectiveness. In the discussion, we also focus on reflecting the results of this study against the results based on the RCT study (Ristolainen et al., Citation2020, Citation2022).

Summary of the results – understanding process of the intervention

The summary of the results responds to the main aim of the study, i.e. to clarify and better understand the causal pathways of the intervention. In general, the results show that the effectiveness of the intervention is based on various individually and socially constructed causal pathways. (.)

In terms of the preceding factors, essential knowledge of the preconditions relates to the intervention and participants, which also represents the complexity of the practice (see Craig et al., Citation2013; Kazi, Citation2003). During the intervention, it was confirmed that the study participants were a heterogeneous group of older people living alone. The main aim and basic elements of the intervention were known, but the content of the intervention was tailored in accordance with the needs of the group in question.

From important elements to proximal outcomes

The three important elements of the intervention (social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings) reflect the preceding knowledge of the main elements of the intervention (social support, counseling, and activities; see ). However, the activities appeared to be less important for the participants, whereas the scheduled group meetings themselves were seen as valuable elements. Social support exchange and needs-based counseling partly overlapped each other as the counseling between group members also involved peer support. In general, the multiple needs of the participants influenced the outcome that some participants experienced social support to be more important, while others were more satisfied with the counseling.

The important elements of the intervention are connected to the proximal outcomes (strengthened social wellbeing, enhanced resources and awareness, and experiences of meaningfulness), although the relations are not strict. Strengthened social wellbeing is a clear consequence of social support exchange. Respectively, enhanced resources and awareness as proximal outcomes are strongly linked to counseling, mostly in terms of receiving information on services and activities, although social support exchange also enables obtaining inspiration and new perspectives that may be beneficial resources. By contrast, experiences of meaningfulness seem to be a consequence of all three important elements.

The moderating factors depend on each other and influence the outcomes of the intervention. Whether a participant is satisfied with the intervention and experiences positive outcomes depends on their needs and expectations of the intervention. Participation in the group is influenced by the current health status and mobility of the participants and the accessibility of the intervention. In planning and conducting the intervention, group tutoring skills enhance the functionality of the intervention. Group tutors also need to be sensitive to the characteristics of each group member. There was no systematic training for group tutors, which can be seen as a shortcoming in the piloting of the intervention. The results concerning moderating factors confirm that the benefits of the intervention were individual and varied across intervention subgroups.

Connections between various outcomes

Immediate proximal outcomes may refer to the mechanisms of the intervention leading to intermediate and distal outcomes (see Wadsworth & Markman, Citation2012). We found that the proximal outcomes together resulted in two intermediate outcomes (changes in routines and participation and empowerment). First, the continuity of social contacts, awareness of services and activities, motivation and new perspectives, variation in daily routines, and positive experiences and feelings seemed to stimulate positive transitions in the older people´s routines and participation. Secondly, sense of togetherness, awareness of services and activities, motivation and new perspectives, positive experiences and feelings, and sharing knowledge with those in need were connected with empowerment. The results of perceived outcomes are partly similar to previous evaluation studies of group-based interventions targeted at older adults, for example in terms of a sense of togetherness (Pynnönen et al., Citation2018), empowerment (Savikko et al., Citation2010), and gaining motivation and new perspectives (Kajander et al., Citation2022).

The previous results from the RCT study indicated that the intervention did not improve older people´s quality of life, but it may be beneficial in terms of alleviating loneliness among the most vulnerable older people and among those who continued group meetings after the official meetings ended (Ristolainen et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). According to the analysis, the proximal outcome of strengthened social wellbeing indicates that the intervention was important for the social relations of the participants. This could also be associated with experiences of decreased loneliness.

In addition, based on the RCT study, the intervention may increase trust in other people and trust in some public institutions (Ristolainen et al., Citation2020). In terms of trust, the proximal outcome of experiences of meaningfulness included the message that the older people felt respected, which may be related to increased trust in others. In addition, trust in some institutions such as social care may be a consequence of counseling and it also corresponds with the intermediate outcome of empowerment, as the participants reported trusting in the future because of the information they gained. In conclusion, the results of the mixed method evaluation are mutually supportive.

The previously published results of the RCT showed that the effects of the intervention were mostly neutral (see Ristolainen et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). However, this study indicated that the intervention led to individually appearing outcomes which may not be quantifiable by generic scales, such as the WHOQOL-BREF used in the RCT. In addition, the results of this qualitative study may differ from the results of the RCT study because the perceived and observed outcomes found in this study were more concrete first-step wellbeing promotion outcomes compared to the outcomes measured by the WHOQOL-BREF instrument. At the same time, results showed that to achieve these outcomes the key elements of the intervention (social support exchange, needs-based counseling, and scheduled group meetings) should be implemented. For strengthening the effectiveness, the following aspects should be taken into consideration when refining the intervention and planning its implementation: 1. increasing the number of tutored group meetings, 2. ensuring transportation to group meetings, 3. supporting participants to organize meetings independently during and after the intervention period, 4. organizing systematic training for group tutors.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has several strengths and potential limitations. Data were collected from all participants through the reflective diaries after each group meeting, the focus group discussions in the last group meetings, and the interviews with those who did not attend the focus group discussions. Reflective diaries were written by the researchers and care managers based on their observations at the group meetings. Developing personal relationships with participants offered possibilities for open and frank discussions when collecting the data. However, participants’ responses may have been positively biased if they felt they must present a positive impression to the researchers and care managers (see Bartlett et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, we found that participants provided a combination of positive, negative, and neutral comments regarding the intervention. There was no possibility to differentiate between men and women in this study, but previous studies have indicated that older men have less social and practical motivations of learning compared with women (e.g. Narushima et al., Citation2013). As most of the participants were women, more knowledge is needed of men’s experiences, motivations, and perceived benefits of group-based educational interventions.

The focus groups complemented the observations, mainly because it was possible to gain a deeper understanding of the range of viewpoints among the participants. On the other hand, participants in the focus groups may have been hindered in expressing their own opinions due to the presence of others. Talkative participants spoke more in the focus group discussions, while the voice of more reserved participants was possibly not heard. Finally, the longitudinal data collection during the intervention enabled to understand how changes were initiated and maintained over time under the contextual conditions of the intervention. One limitation is the fact that the authors also participated in the planning and carrying out of the intervention. The possible bias has been carefully considered throughout the research process to increase the objectivity of the study.

The intervention is based on the social interaction between group members, which makes it difficult to evaluate the optimal conditions in which the intervention works. As Blom and Morén (Citation2010) argue, social interaction must be part of the mechanism of social interventions. However, with respect to social action and how it exerts impact within the intervention, there are many components that are not visible or observable. The results of this study showed possible causal pathways offering some understanding of the mechanisms of the intervention. Yet, in this study we did not focus on social interaction itself. This would be an interesting topic to examine in future evaluations of group-based interventions. Another relevant research topic would be the educational view; taking into consideration that older adults with different backgrounds seem to benefit by discussing and learning from each other in a group.

Conclusion

The results of the study offer more in-depth understanding of the complex relations between the important elements of the participatory group-based care management intervention and its outcomes. The results confirm the initial idea of the intervention for combining counseling (preventive care management) and social support (group-based model) to meet the diverse needs of older people living alone. The important elements of the intervention seem to empower older people and engage them in activities. As regards combining the results of this study with the results of the RCT (Ristolainen et al., Citation2020, Citation2022), the intervention as a group-based, socially supportive, and participatory method seems to strengthen the social wellbeing and participation of some older people, as well as alleviate the loneliness of those people in most challenging life situations. Secondly, the intervention as a care management method may increase trust toward the social and health care system, relieving the older persons’ sense of insecurity. Finally, the intervention should be refined based on the results of the process evaluation before its implementation.

Ethical considerations

The study was carried out with the approval of the University of Eastern Finland Committee on Research Ethics and the municipalities participating in the trial. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the data collection, with detailed information about the research protocol including a description of the randomization process. The participants were able to withdraw from the study at any stage of the project. All data have been treated confidentially.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in collaboration with the University of Eastern Finland, the University of Jyväskylä, South Karelia Social and Health Care District (Eksote), Joint Municipal Authority for North Karelia Social and Health Services (Siun sote), the city of Jyväskylä, and the city of Kuopio. The authors wish to thank the directors of older people care services and the care managers who participated in planning and carrying out the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartlett, H., Warburton, J., Lui, C., Peach, L., & Carroll, M. (2013). Preventing social isolation in later life: Findings and insights from a pilot Queensland intervention study. Ageing and Society, 33(7), 1167–1189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000463

- Blom, B., & Morén, S. (2010). Explaining social work practice – the CAIMeR theory. Journal of Social Work, 10(1), 98–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017309350661

- Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing and Society, 25(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002594

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., & Perach, R. (2015). Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: A critical review. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29(3), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.130418-LIT-182

- Coll-Planas, L., Del Valle Gómez, G., Bonilla, P., Masat, T., Puig, T., & Monteserin, R. (2017). Promoting social capital to alleviate loneliness and improve health among older people in Spain. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(1), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12284

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2013). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical research council guidance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(5), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010

- Creamer, E. (2018). Enlarging the conceptualization of mixed method approaches to grounded theory with intervention research. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(7), 919–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218772642

- Fletcher, A., Edmond, P., Ng, E., Stirling, S., Bulpitt, C., Breeze, E., Nunes, M., Jones, D., Latif, A., Fasey, N., Vickers, M., & Tulloch, A. (2004). Population-based multidimensional assessment of older people in UK general practice: A cluster-randomised factorial trial. Lancet, 364(9446), 1667–1677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17353-4

- Gardiner, C., Geldenhuys, G., & Gott, M. (2018). Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 26(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12367

- Godwin, M., Gadag, V., Pike, A., Pitcher, H., Parsons, K., McCrate, F., Parsons, W., Buehler, S., Sclater, A., & Miller, R. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of the effect of an intensive 1-year care management program on measures of health status in independent, community-living old elderly: The Eldercare project. Family Practice, 33(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv089

- Granbom, M., Kristensson, J., & Sandberg, M. (2017). Effects on leisure activities and social participation of a case management intervention for frail older people living at home: A randomised controlled trial. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(4), 1416–1429. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12442

- Hudon, C., Chouinard, M., Brousselle, A., Bisson, M., & Danish, A. (2020). Evaluating complex interventions in real context: Logic analysis of a case management program for frequent users of healthcare services. Evaluation and Program Planning, 79, 101753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101753

- Kajander, M., Gjestsen, M. T., Vagle, V., Meling, M., Henriksen, A. T., & Testad, I. (2022). Health promotion in early-stage dementia – user experiences from an educative intervention. Educational Gerontology, 48(9), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2022.2043618

- Kazi, M. (2003). Realist evaluation in practice: Health and social work. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209762

- Kelle, U. (2007). The development of categories: Different approaches in grounded theory. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 191–213). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607941.n9

- Kharicha, K., Iliffe, S., Harari, D., Swift, C., Gillmann, G., & Stuck, A. (2007). Health risk appraisal in older people 1: Are older people living alone an ‘at-risk’ group? British Journal of General Practice, 57(537), 271–276.

- Moore, G., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. British Medical Journal, 350, h1258–h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

- Narushima, M., Liu, J., & Diestelkamp, N. (2013). Motivations and perceived benefits of older learners in a public continuing education program: Influence of gender, income, and health. Educational Gerontology, 39(8), 569–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2012.704223

- Palese, A., Mesaglio, M., De Lucia, P., Guardini, I., Forno, M., Vesca, R., Boschetti, B., Noacco, M., & Salmaso, D. (2013). Nursing effectiveness in Italy: Findings from a grounded theory study. Journal of Nursing Management, 21(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01392.x

- Payne, M. (2000). The politics of case management and social work. International Journal of Social Welfare, 9(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2397.00114

- Pynnönen, K., Törmäkangas, T., Rantanen, T., Tiikkainen, P., & Kallinen, M. (2018). Effect of a social intervention of choice vs. control on depressive symptoms, melancholy, feeling of loneliness, and perceived togetherness in older Finnish people: A randomized controlled trial. Aging and Mental Health, 22(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1232367

- Ristolainen, H., Kannasoja, S., Tiilikainen, E., Hakala, M., Närhi, K., & Rissanen, S. (2020). Effects of ‘participatory group-based care management’ on wellbeing of older people living alone: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 89, 89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104095

- Ristolainen, H., Tiilikainen, E., & Rissanen, S. (2022). Käytännöllinen satunnaistettu kontrolloitu tutkimus osallistavan ryhmämuotoisen palveluohjauksen vaikuttavuudesta. Journal of Social Medicine, 59(4), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.23990/sa.102338

- Rossi, P., Lipsey, M., & Freeman, H. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach (7th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Saito, T., Kai, I., & Takizawa, A. (2012). Effects of a program to prevent social isolation on loneliness, depression, and subjective well-being of older adults: A randomized trial among older migrants in Japan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(3), 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.002

- Savikko, N., Routasalo, P., Tilvis, R., & Pitkälä, K. (2010). Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: Favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00191.x

- Sixsmith, A., & Sixsmith, J. (2008). Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing International, 32(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-008-9019-y

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J., Boyd, K., Craig, N., French, D., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- The Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Services for Older Persons 980/2012

- The Social Welfare Act 1301/2014.

- Soydan, H. (2015). Intervention research in social work. Australian Social Work: Applied Research Methods in Social Work, 68(3), 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.993670

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage publications.

- Taube, E., Kristensson, J., Midlöv, P., & Jakobsson, U. (2018). The use of case management for community-dwelling older people: The effects on loneliness, symptoms of depression and life satisfaction in a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12520

- Tiilikainen, E., Hujala, A., Kannasoja, S., Rissanen, S., & Närhi, K. (2019). “They’re always in a hurry”: Older people´s perceptions of access and recognition in health and social care services. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(4), 1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12718

- Victor, C. R., Scambler, S. J., Bowling, A. N. N., & Bond, J. (2005). The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: A survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing & Society, 25(6), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04003332

- Wadsworth, M., & Markman, H. (2012). Where´s the action? Understanding what works and why in relationship education. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.006

- WHO. (1996). WHOQoL-BREF introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. Field trial version. World health organization.

- Wolford, S., & Holtrop, K. (2020). Examining the emotional experience of mothers completing an evidence-based parenting intervention: A grounded theory analysis. Family Process, 59(2), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12441