ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of digital inclusion for equitable and healthy aging. Older immigrants experience unique needs and challenges in using information and communication technologies compared to other older adults. Despite the proliferation of digital learning programs for older adults, there is minimal evidence of digital literacy learning needs and strategies relevant to older immigrants. The aim of this study is to explore learning approaches and digital engagement amongst Arabic-speaking older immigrants. This community-based qualitative descriptive study used co-designed group digital learning sessions. Two organizations supporting local ethnocultural communities in a municipality in Alberta, Canada recruited 31 older immigrants who spoke Arabic, Farsi, and Kurdish. Data collection included semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and observations of digital learning sessions. A total of seventeen learning sessions were completed with nineteen participants each attending five to six sessions. Findings highlight the iterative nature of the program sessions, the importance of catering to participants’ interests, the relevance of peer support, and language, sensory and digital variability barriers to learning. Digital literacy programs for immigrant older adults should adjust for language learning needs, maintain a flexible approach, tailor lessons to individual needs, foster social support, and address external factors such as limited digital access and transportation barriers.

Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICT) are digital tools that facilitate access to and exchange of information (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Citation2009) with smartphones being used by over 92% of Canadians (Taylor, Citation2023). Digital literacy encompasses a myriad of social practices and conceptions that enable an individual to search, find, evaluate, and compose information utilizing typing, writing, and other mediums (e.g., multimedia videos, video calling, messaging) on various digital platforms (Bawden, Citation2008). Digital literacy contributes to social inclusion, enables self-empowerment and facilitates participation in economic, educational, political, and cultural systems (Kvasny & Keil, Citation2006; Nordicity, Citation2017; Vinson, Citation2007; Wynia et al., Citation2019).

Digital literacy has become essential for the well-being of older adults (Sen et al., Citation2021). The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the significance of digital inclusion in achieving equity and fostering positive aging experiences and the ongoing digital divide experienced by older adults (Litchfield et al., Citation2021). The term ‘digital divide’ describes the disparity between individuals who utilize digital technologies to fulfill their information and communication requirements and those who do not (Ragnedda & Muschert, Citation2013). Older adults experience challenges related to a lack of connectivity through appropriate digital tools, a lack of skill and capacity to use digital devices and a lack of motivation related to the functionality and content of digital media (Davidson & Schimmele, Citation2019; Friemel, Citation2016; Olphert & Damodaran, Citation2013; Safarov, Citation2021). Other barriers that contribute to digital disengagement among older adults include negative user experiences that decrease self-confidence and increase technology-related anxiety (Steelman & Wallace, Citation2017). While there is recognition that older adults experience the digital divide and can benefit from using ICTs in a myriad of ways, there remains a lack of understanding of ways to foster digital competence and address digital learning needs. Digital learning approaches that are successful with older adults depends on individual preferences for using technologies, cultural perceptions of aging, and social dynamics (Schreurs et al., Citation2017). Ageist self-perceptions limit technology adoption and are a barrier to learning (Köttl et al., Citation2023), while the presence of social support supports uptake and learning (Tomczyk et al., Citation2022). Additionally, older adults have diverse life experiences and positionalities that shape their learning preferences which challenges the notion that there can be a single approach to enhancing digital competence in this group (Tyler et al., Citation2018; Wynia Baluk et al., Citation2023).

Canada witnessed a surge in its population in 2022, welcoming 437,180 new immigrants and a net increase of 607,782 nonpermanent residents (Statistics Canada, Citation2023). Older immigrants’ access to and use of ICTs is hindered by factors related to both age and immigrant background (Safarov, Citation2021). Older immigrants face greater challenges in the utilization of ICT compared to other groups due to limited financial resources to acquire and use digital devices, poor mainstream language proficiency, low acculturation levels, education barriers, and lack of social support (X. Chen et al., Citation2020; Fang et al., Citation2019). Recent Canadian immigrants are less likely overall to use the internet but have a higher level of online activity if they do use it (Haight et al., Citation2014). There is limited information, however, on the digital engagement of older immigrants in Canada (Salma et al., Citation2021). Older immigrants might learn to utilize ICT during their migration to leverage resources and adapt to migratory changes (Nguyen et al., Citation2022). ICTs can, also, help older immigrants overcome language and cultural difficulties by increasing access to information in their language, fostering a sense of independence, and maintaining and strengthening social relationships with co-ethnic communities and families in local and transnational digital spaces (Baldassar et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Kouvonen et al., Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Vitak, Citation2014; Wilding et al., Citation2022). The increasingly digital climate of public service provision is another consideration for addressing older immigrants’ digital literacy (Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Safarov, Citation2021).

Immigrants from Arabic-speaking countries are growing in Canada (Statistics Canada, Citation2023) with many choosing to age in place post-migration. Older Arabic-speaking immigrants report loneliness, social isolation, and lack of access to social, recreation and healthcare services post-migration especially those who are refugees, newcomers, and with lower acculturation (Ajrouch & Fakhoury, Citation2013; Elshahat & Moffat, Citation2022; Salma & Salami, Citation2020). Arabic-speaking immigrants traditionally belong to extended family models and value close interpersonal relationships (Canadian Arab Institute, Citation2013) with use of ICTs shaped by social identities and roles across local and transnational spaces (Hennebry & Momani, Citation2013). Gender, income, education, and technology infrastructure in countries of origin shape use of technologies and motivations to develop particular knowledge and skills (Salma et al., Citation2021). The digital learning approaches preferred by Arabic-speaking older immigrants might be different than the general population of older adults but there are no studies or descriptions of programs in the literature that address this despite other studies showing the importance of tailored learning approaches in diverse populations of older adults (Pihlainen et al., Citation2023).

Older Canadian immigrants continue to face loneliness, social isolation, and barriers to aging-supportive resources (Georgeou et al., Citation2023; Hawkins et al., Citation2022; Salma & Salami, Citation2020) and improving digital literacy might be one avenue to tackling these disparities. We use the term ‘immigrant’ throughout this study which is inclusive of family-sponsored immigrants, economic immigrants and refugees who have permanently settled in Canada. The focus on this paper is primarily to explore the learning processes and digital engagement of Arabic-speaking older immigrants who participated in co-designed digital learning sessions in an urban Canadian setting. Additionally, the paper outlines the co-design approach used to create an inclusive and responsive learning environment while highlighting considerations for future digital literacy programs with this population.

Theoretical framework

The study was informed by Adult Learning Theory and the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.2). Two principles from Adult Learning Theory guided the approach to observing and exploring digital learning: (1) older adults bring a wealth of knowledge and skills accumulated over their life course, and (2) older adults will engage in learning when it is viewed as useful and of interest to their lives (Arthanat et al., Citation2019; Mubarak & Nycyk, Citation2017; Schirmer et al., Citation2023). DigComp 2.2 assisted with differentiating between five competence areas: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem-solving (Vuorikari et al., Citation2022). Each competence area contains dimensions that correlate a proficiency level to assessment indicators which can be used to design competence assessment tools and support education and training. It is important to note that safety and problem-solving are overarching competencies that are enacted within the context of the other three domains. Older adults participate in an array of social, economic, and recreational activities that require digital skills and knowledge (Chopik, Citation2016; Khvorostianov et al., Citation2012; Seifert & Schelling, Citation2018), and, hence, the DigComp framework is useful in identifying potential learning gaps and areas for development.

Methods

Research design

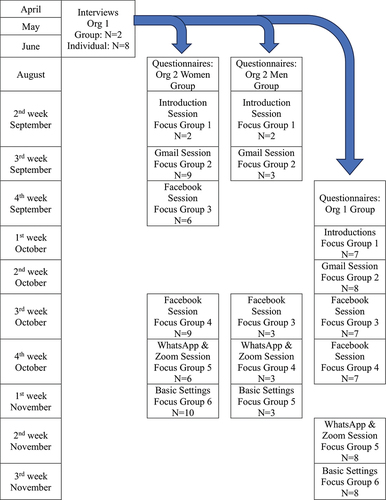

The research team utilized iterative co-design cycles in this community-based project to create group digital learning sessions for older immigrants. We utilized a qualitative descriptive methodology to inform the interviews, focus groups, and direct observation to explore their learning needs and preferences (Sumner et al., Citation2021). Utilizing a range of data collection approaches to explore older adults’ digital literacy enhances the potential for participant engagement (Sumner et al., Citation2021) and enables researchers to be responsive and empathetic toward the difficulties participants may encounter (Littlechild et al., Citation2015). The study commenced over two phases: Phase one involved semi-structured interviews (individual and group) and phase two centered on focus groups and digital learning session observations (). The research team allocated pseudonyms to all names used in this paper.

Setting and participant recruitment

Participants met the following inclusion criteria: 1) 55 years of age or older; and 2) report using ICTs in their daily lives. As this was an exploratory study, we selected not to evaluate the prior digital competence of participants. Our goal was to understand the learning processes and digital engagement among a diverse group of users. Two organizations, a social service agency and an ethnocultural organization, based in an urban municipality in Alberta, Canada, supported participant recruitment and provided space for the group-based digital learning sessions. Both organizations were chosen based on their interest in the project and their delivery of social programs to older immigrants from Arabic-speaking communities. Older immigrants were invited by service providers at these organizations via phone calls and in-person introductions. Those who reported initial interest in participating were then contacted by the research team for a detailed explanation of the study. In qualitative studies, sample size depends on data saturation where there is sufficient data obtained to provide an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon of interest in a particular context and time (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Thus, we conducted recruitment and learning sessions until we explored key areas of digital competence and yielded a strong pattern of repetitive data for analysis.

Data collection

This study received ethics approval from the research ethics board of the first author’s institution and all participants provided informed consent before data collection. All participants received an honorarium for each interview and focus group session attended to compensate for time away from work or caregiving responsibilities and transportation costs to the learning sessions. The research team was comprised of experienced qualitative researchers with some who were bilingual in Arabic.

Phase One

Ten semi-structured interviews were conducted with older immigrants about their use of digital technology and learning needs. An interview guide using DigComp 2.2 was utilized to capture the domains of digital competence (Appendix 1) and socio-demographic data was collected. Interviews lasted one to two hours and were completed from April to June 2022 at participants’ homes. Some interviews were completed in Arabic with the assistance of an Arabic-speaking team member.

Phase Two

To better understand the characteristics of participants before commencing the learning sessions, technology acceptance and mobile device proficiency of participants were evaluated using the 14-item brief version of the Senior Technology Acceptance Model (STAM) questionnaire (K. Chen et al., Citation2020), and the short 16-question version of the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (MDPQ-16) (Roque & Boot, Citation2018). The STAM questionnaire consists of four constructs that represent technology acceptance and age: attitudinal beliefs, control beliefs, gerontechnology anxiety, and health conditions. Response options are provided for 14 items in the form of a 10-point Likert scale (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree, 10 = strongly agree). The MDPQ-16 consists of eight subscales to determine the ability to perform operations on a smartphone. Two operations are allocated to each of the subscales: mobile device basics, communication, data and file storage, internet, calendar, entertainment, privacy, troubleshooting and software management. Response options are provided for 16 items in the form of a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., 1 = never tried, 5 = very easily).

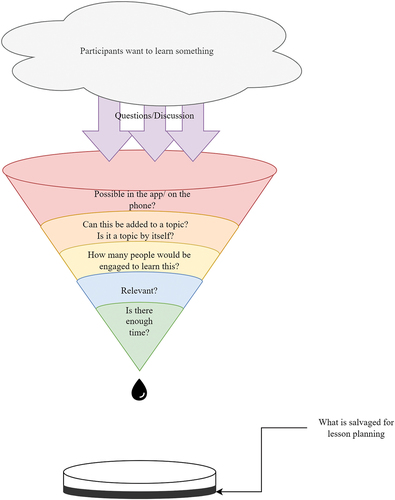

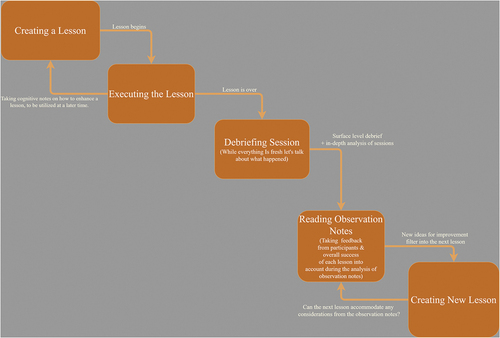

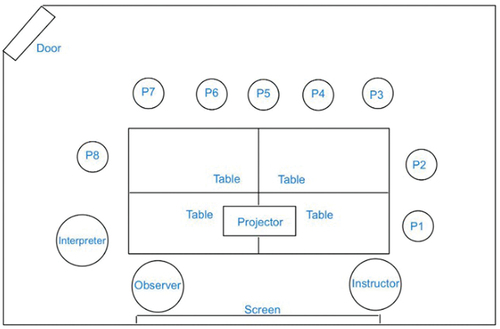

Learning sessions lasted two hours and were conducted weekly from September to November 2022. Focus groups and observation of learning sessions allowed for further exploration of the key areas highlighted in phase one by participants as desirable dimensions for digital learning. A 30- to 45-minute focus group was conducted before each learning session to explore the relevance of the educational content prepared for that session, and to generate ideas on what digital competencies should be attended to in the following sessions (Appendix 2). The second author was the instructor for the learning sessions and a 4th-year undergraduate computer engineering student in his 20s who was familiar with the technologies and applications being used in the plan for this project. He was of Pakistani/African American heritage and understood cultural expectations around respect and authority of community elders. The instructor was supported by an Arabic-speaking facilitator experienced in community-based grassroots research, the third author, from the research team to support the high number of Arabic-speaking older adults in the study. The instructor led the preparation of educational content for each session, and used a Funnel Filter Strategy to identify potential activities for future learning sessions by assessing the feasibility and teachability of the participants’ interests (Possible in the app/on the phone?), whether this interest could be incorporated into future lessons (Can this be added to a topic? Is it a topic by itself?) and the relevance of the lesson content to DigComp competencies (Relevant?) (). As each lesson was executed, the instructor diligently noted its progress, areas of participant struggle, and potential resequencing for improved coherence using a Feedback Spiral Strategy (). An observation form was developed to record learning session activities, especially the ways older immigrants navigated their devices, group dynamics during learning, and the socio-emotional responses of participants during the sessions.

Data analysis

All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For non-English interviews and focus groups, transcription occurred in Arabic and then analysis occurred initially in Arabic by two bilingual research team members. Key quotes were then translated into English for team discussion and use in knowledge dissemination. A thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014) was guided by the DigComp 2.2 to address each competency domain, and NVivo 12 software was used to facilitate the coding process. Codes and themes were developed to highlight the digital engagement of older immigrants and the learning approaches in the group-based sessions (). The strategies to uphold trustworthiness included maintaining an audit trail throughout the research process, engaging in reflexivity through ongoing meetings with research team members, and providing a rich description of the data and study context (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). With respect to personal and interpersonal reflexivity (Olmos-Vega et al., Citation2023), we report that the first and last author are nurse researchers that have conducted qualitative research and are well versed in using intersectional approaches. The last author has led research activities with the Arabic-speaking older immigrant population in this Alberta urban center for the past eight years, and led the team during the data analysis and member reflection stages. The first author led data collection with support from the third and last authors who shared the same linguistic background with the participants, and were thus tasked with interpreting and translating the data.

Table 1. DigComp key quotes and associated learning activities.

Quantitative analysis was performed using STATA 17.0 BE-Base Edition. Descriptive statistics for categorical demographic variables were presented in count and percentage; age, which is a continuous variable, was presented using mean and standard deviation. Responses to the Senior Technology Acceptance were reported using median score and inter quarter range. Further, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were performed to check the equality of medians among each category of senior technology acceptance questions between the two locations. P-values from the Wilcoxon rank sum tests were reported to indicate if the two locations had the same responses. In this study, p-value <.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

In total, 31 participants participated in this study with 19 older immigrants completing the co-designed group-based learning sessions, each attending five to six sessions. In organization one, there was a single group consisting of both older men and women, as many were couples who wished to learn together. The second organization included two separate groups, one for men and another for women. The average age of participants was 64.1 ± 7.7 years. Most of the participants were female (n = 20, 64.7%), were born in Syria (n = 16, 51.6%), identified as Arab (n = 28. 90.3%), and were Canadian citizens or Canadian permanent residents (n = 30, 93.5%), and had the highest level of education was post-secondary school (n = 11, 35.5%). Most participants had a family income of less than $20,000 (n = 21, 67.1%) and received government financial support (n = 23, 74.1%) ().

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of all participants (n = 31).

With regards to mobile device proficiency of participants, most strongly agreed that using technology was useful and would enhance their effectiveness in daily activities. Three items differed based on the source of participant recruitment: Organization two participants showed slightly higher acceptance of completing a task using technology if there is someone to demonstrate and higher gerontechnology anxiety, compared to the organization one group. No other significant differences were noted in the other senior technology acceptance items between the two groups (). No other significant mobile device proficiency level differences were evident between the participant groups (). Participants felt more comfortable navigating onscreen menus using the touch screen and finding information about their hobbies and interests on the internet. Participants reported having low confidence in data and file storage, calendar use, privacy setups, and troubleshooting and software management.

Table 3. Results on senior technology acceptance using STAM of phase 2 participants (n = 21).

Table 4. Results on mobile device proficiency using MDPQ-16 of phase 2 participants (n = 21).

We identify below three key themes that were most important in exploring the learning processes of Arabic-speaking older immigrants engaged in the digital literacy sessions: (a) the interplay of participants’ interests and attitudes, (b) the role of peer support in and out of the classroom, and (c) sensory, language, and digital variability barriers to learning.

Interplay of participants’ interests and attitudes

Following the DigComp 2.2, the learning sessions were prepared to ensure participants could grasp core concepts without feeling overwhelmed. Core areas of focus for learning sessions were derived from four of the digital competencies-information access and use, communication, safety, and problem solving-while the competency of digital content creation was not identified as a priority to this group (). Areas of focus were captured in the initial interviews and then nuanced learning needs were further identified during learning session observations and focus groups. The project sought to support participants’ comfort in using smartphones which was their device of choice, and so all sessions focused on mobile applications (). All phone types were allowed ranging from iPhone to Samsung and other Android phones.

Table 5. Applications and associated objectives for each learning session.

Throughout our sessions, participants shared the importance of learning certain skills that support local integration (e.g., subscribing to the local mosque’s newsletter). In particular, participants from one organization used the space to exchange and seek information related to integration and essential services from each other (e.g., discussing where to apply for senior financial services and benefits, and sharing different options for English language learning in the city). These conversations were a gateway to their discussions about needing to navigate transnational digital spheres to maintain social ties or find information in their native language. Feedback received via focus groups was positive. Participants shared their appreciation for having programming tailored to them and emphasized the importance of continuous programming that caters to the learning needs of older adults.

We learnt something in our older age.

I feel capable. I do not need to depend on anyone … when you are in a tight spot and there is no one near you to ask it is very difficult.

We want to participate in society … if my friend sends me an email, I want to learn to respond … I feel I want to express myself.

I wanted to come and learn because living alone there are a lot of times where I get stuck … no one has time or can help me if someone is waiting to communicate or when I am watching a gardening show and want to ask a question I say to myself: ‘if only I can ask a question, wouldn’t that be great?’

A person doesn’t only want to receive information, they want to engage with the information. (Organization 2, Focus group)

A crucial part of the project related to the ability of the instructor to utilize a learner-centered approach. Although the sessions would each begin with a classroom structure as seen in , the instructor frequently spent time sitting with participants and going around the table to go through each learning objective using a one-on-one approach. Some examples of the instructor working outside the scope of the program to attend to participant needs included dealing with account management, troubleshooting e-mail lockouts, and optimizing layouts on phones so participants could more easily navigate applications.

Participants mostly showed positive outlooks on digital learning and were excited to hear about new digital features and applications (e.g., how to make a Zoom meeting, how to screenshot).

One participant took a lot of the Arabic-speaking facilitator’s time as he wanted to know what Facebook was for and all the features. He drew the icon of each button on the Facebook homepage and wrote what they meant. We went through how to post, and the different features that could be added into the post. He was able to make connections between similar features on other apps. [Excerpt from observation notes; Organization 1, Week 3]

The level of engagement with the session content varied over the weeks for each participant as it depended on what they wanted to learn and their digital competence for that particular activity. Participants discussed the applications relevant to their day-to-day lives and were more focused on learning how to maximize their use. Some participants who used WhatsApp every day to communicate found the WhatsApp session most relevant and the session on e-mail and password management the least relevant. On the other hand, a couple of participants showed their skill in using e-mail but identified new interest in Facebook.

Role of peer support in and out of the classroom

Over time, participants’ relationship with the instructor and each other became a motivation to participate. Participants who were previously socially isolated built new social connections. Seeing each other’s online profiles and names allowed them to share resources. Alongside building relationships within the classroom setting, peer learning occurred in the latter sessions within each of the groups. Some instances were instigated by the instructor in an attempt to help higher-level users engage more by mentoring participants who were having more difficulties. Other instances were naturally occurring as participants would learn by listening to the instructor, then teach a peer who they saw was struggling with the activity.

Nasih asked about deleting posts. The instructor explained the types of options for privacy to Nasih and Hadi. The instructor explained to Nasih what to do and what it meant. When the instructor went to explain to Hadi, Nasih appeared to want to share that he understood and started to explain in Arabic to Hadi. He’s using his phone in Arabic and matching it to Hadi’s English format to explain each option in the order they appear on the screen. [Excerpt from observation notes; Organization 1, Week 4]

Participants reinforced each other’s attendance, which resulted in no dropouts after sessions began. Several situations unrelated to the program showed how the participants would address each other’s problems by sharing what they knew about credible information, public services, and formal social support.

Prior to starting the focus group, Aisha shared that her daughter passed away yesterday. We spent 15 minutes sitting around the table hearing her out and other participants were sympathizing with her. Aisha said that she knew that she could get support here, and that was why she came. [Excerpt from observation notes; Organization 1, Week 2]

In organization one, the older adults who were newcomers faced greater vulnerability. They expressed feelings of loneliness but found solace in forming friendships with others who shared their age and cultural background. They also found the program to be a valuable tool for both learning and social engagement. They even exchanged phone numbers with the hope of sharing information about financial resources. During our sessions, they also showed each other helpful English-learning videos they found on Facebook. In the second organization, where participants already had established relationships, their connections with one another catalyzed co-learning with their peers.

Because my children are at home, I depend on them (for technology support)

You should learn from them. Do they have time to teach you?

They are not patient with us. They take the device and do it for you. (Organization 2 – Focus Group)

Participants described how there were no family members available to help them or that family members restricted their ability to freely use their phones by presetting privacy options or managing accounts for them. While some older adults in this project were reliant on their children and grandchildren for support with their digital-related activities, the opportunity to engage with peers in co-learning sessions challenged prior ageist assumptions in the group about their capacity to learn and advance their digital skills.

Sensory, language, and digital variability barriers to learning

English was the dominant language of applications on smartphones and while these could be switched to Arabic, many participants were more familiar with the English digital terminology. Content within these applications, however, was often in the language that the participant was most fluent in. A participant who was illiterate in her first language but was beginning to learn to read English experienced difficulties in following along with the class but found images and the hands-on support helpful. Many participants highlighted the additional complexity of a language barrier when using ICTs.

I do not know how to respond [to emails] … how can I respond? If I receive an email in Arabic, I read it and can respond … but if it is in English, I do not respond.

The instructor helped participants navigate barriers at the intersections of low digital competence and low English language fluency. Having both Arabic and English on the presentation slides in each session was an opportunity to engage with class content and English-language learning. Participants showed the instructor their difficulty in managing utility bills received through e-mail, navigating mainstream information on social media sites, using the English touch screen keyboard, dealing with spam, and responding appropriately to scam calls.

You could navigate for information in Arabic, but you can’t be sure if what you found is a trusted site. Likewise, if you look it up in English, you can try to translate the information online into Arabic but it won’t be as easy to understand as if it were in Arabic to begin with.

The varying digital skills of participants and the variety of devices and digital applications they used posed challenges. While the instructor was prepared for both iOS and Android OS phones, the different phone models, button locations, application interfaces, and storage availability were obstacles that required one-on-one hands-on support for each participant. Participants were unfamiliar with ways to navigate new features or user interfaces due to underlying gaps in understanding the operation principles of their devices. Participants were given the class content in electronic and print forms so they could review and practice, but participants voiced difficulties absorbing instructions in the learning sessions. One participant highlighted the need for more time to learn.

… because when you get older, everything goes less, your thinking, your brain, you’re slow, even to walk, even to get up and everything is slow for you, 5 weeks [of learning sessions] it’s not good enough to know everything, but if we had a little bit longer, it would be good. [Organization 1, Focus group, immigrant older man]

Our participants often needed glasses or experienced difficulties reading small text sizes. While using tablets could help enlarge text and image sizes, one participant noted they were too heavy for her to hold and use at the same time, which points to issues around portability and accessibility. For many participants, being able to learn skills specific to the device they owned was important. Although tablets were offered by the researchers, the participants said they did not see the value of learning on a tablet if they did not own such a device, even if some skills were transferable to their smartphones. Another barrier to learning related to the vision and hearing needs of participants. While some participants wore glasses, others needed to be reminded to wear visual aids.

We no longer can process information easily.

It’s age, age.

Because of illness and poor eyesight. (Organization 1, Focus group)

An older man also voiced that he had a hard time hearing higher-pitched voices. Facilitators would often manipulate the mobile device for the participant and the participant would observe, then was asked to replicate the process or report on their understanding. Some participants when struggling would either give up or hand their phone to a facilitator to address the issue. The combination of sensory and language barriers to learning reinforces the need for universal design principles in designing digital learning sessions and emotional support to overcome frustration and learning-induced anxieties.

Discussion

Digital competence is an important gateway to social participation. Migration results in the disruption of social networks (Barwick, Citation2017; Ryan, Citation2011) where older immigrants can no longer rely solely on close local contacts for social connectedness and support. Digital and language barriers limit access to settlement and integration information that is readily available via ICTs (Khvorostianov, Citation2016; Millard et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Internalized perceptions of ageism limit digital learning and enhance anxiety have been seen in prior studies (Barrie et al., Citation2021). In our quantitative findings, study participants from organization two had a slightly higher desire to have someone demonstrate a skill and more gerontechnology anxiety than study participants from organization one. While we were unable to identify major differences between the two organization groups regarding learning process preferences, our qualitative observations found that the newcomer participants from organization one sought support to navigate unmet needs for information and services and viewed gaining digital skills as essential. Their experiences contrasted other study participants in organization two who have been in Canada long-term had more established social support networks. However, in comparison with organization one, study participants from organization two were mostly women, and more study participants were living alone. Although some of the older immigrant women may have established networks, they may not have engaged in the workforce and their language barriers persisted over time, which may negatively influence their ability to use ICTs independently. Thus, the difference between the study participants in both organizations may imply that accessible social support in using ICT over their life course is important to combat gerontechnological anxiety. The social environment is fundamental for learning and interacting with technology (Tsai et al., Citation2017) and heterogeneity within older immigrant populations and implications for digital learning must be explored further. As guided by the DigComp framework, the study’s learning sessions focused on access to information and communication with safety and problem-solving being major overarching competencies that drove the content of learning sessions. Digital learning needs identified across groups in this study related to two key areas: (1) their changing social support systems post-migration, and (2) digital competence intertwined with language fluency and other barriers.

Addressing social support systems for digital engagement post-migration

The findings of this study emphasize that the availability of social support is a key consideration in screening for and developing digital competence in older immigrants. Informal support by family members in acquiring digital skills is often essential for motivational and emotional reasons (Millard et al., Citation2018; Moore & Hancock, Citation2022). As echoed in the literature (Arthanat et al., Citation2019; Barrie et al., Citation2021; Schreurs et al., Citation2017), study participants faced challenges when managing digital technologies as they lacked confidence in seeking formal assistance, and experienced limited support from their families. Multigenerational households may exhibit lower levels of digital literacy and may prioritize meeting immediate needs over acquiring technological resources (Gallagher et al., Citation2019). Digital literacy programs that engage or communicate with family members alongside participants may be helpful and culturally appropriate to ensure participants can practice their digital skills and support the digital literacy of other family members.

The findings of this study revealed that facilitator characteristics were an important consideration in planning the program. This echoes other studies that emphasize that instructors must be patient, attentive, and empathetic (Moore & Hancock, Citation2022; Mubarak & Nycyk, Citation2017). Our facilitator engaged in ‘unscripted performance,’ by straying from previously scheduled teaching content to adjust to the needs of the participants (Chiu et al., Citation2019). As well, we found that the age difference between the facilitator and the study participants resembled a grandchild-grandparent relationship, thus a personable relationship was established. It is important to consider who would be best situated to engage in digital technology teaching with older immigrants, as previous studies have discussed the barriers to finding qualified and consistent educators for digital literacy programming (Detlor et al., Citation2022; Schirmer et al., Citation2023).

In our study, we also observed another mechanism that is described in the literature as an effective approach for enhancing attitudes toward using digital technology: positive peer role-modeling (Schirmer et al., Citation2023). Study participants would observe their peers using technology, which enhanced their participation in the co-designed program to understand what technology has to offer and receive clear explanations and support on how to use the technology. The literature has emphasized that peer influence and teaching methods are effective ways to engage older adults in using technology (Pihlainen et al., Citation2023; Tsai et al., Citation2017; Wynia Baluk et al., Citation2023). The findings of this study mirror this phenomenon as peer-based social support was mutually beneficial for study participants to learn and reinforce skills in learning sessions. This may be attributed to how supportive environments are critical for older adults to learn and interact with digital technologies (Tsai et al., Citation2017). Unique to the existing literature, we also observed the ways peer support extended beyond digital learning to other areas of their lives such as sharing resources for newcomers or supporting a grieving group member. Even though the participants in this study had lower digital skills, their diverse life experiences enabled them to share knowledge and mutually benefit within the group. It’s conceivable that digital learning programs, which encourage older adults to tap into their collective wisdom, could empower them and foster greater acceptance of such programs.

Utilizing learning theory and managing barriers to digital competence and engagement

This study highlighted that the barriers toward digital engagement and learning are multi-faceted and intersectional. Experiences of confusion, anxiety, and lack of improvement in digital skills are often seen amongst less digitally literate older adults due to the complexities of interface design and constant updates for software applications (Bhattacharjee et al., Citation2020; Moore & Hancock, Citation2022). Beyond the anxiety and inability to keep up with the fast-paced nature of software updates, physical limitations to learning new digital skills relate to the design of technologies. Study participants required tailored support and considerations concerning how they can learn in specific settings to combat technology-related anxiety and develop digital skills. We included considerations such as giving enough time for each activity, step-by-step guidance, and accessibility features (i.e., audio-visual teaching aids). These mechanisms help maintain attention, enforce positive learning attitudes, and enhance clarity with appropriately sized text and icons (Ahmad et al., Citation2022; Mitzner et al., Citation2016; Schirmer et al., Citation2023). The creation of multiple sessions per application and ample time for repetition was essential to build competence in the domains of safety and problem-solving which require a more nuanced understanding of how hardware and software works and was a particular challenge for the study participants.

In this study, it was apparent that the interests of participants facilitated their learning, as some sessions/topics were perceived as more practically relevant than others. Sessions needed to be individually tailored because even within a group of older immigrants, there were differences in terms of purposes in technology use and support systems (Appendix 3). Similar to the literature (Millard et al., Citation2018; Mubarak & Nycyk, Citation2017), the study participants’ comfort with using technology varied due to prior exposure (work, education), and social support (family, friends, programming). Relevant to digital competence is knowing the uses and limits of technologies. Study participants often struggled with features of social media applications and did not recognize that there were ways built into applications to address their concerns. For example, blocking unwanted communication, securing safety online, and personalizing social media content are some areas where study participants were frustrated with technology without recognizing that there were solutions to these issues until discussed in the sessions. In digital technology programs for older adults, explaining concepts such as synchronization, cloud, download permissions, and other digital functions can be challenging (Moore & Hancock, Citation2022). We experienced similar difficulties that were further exacerbated by the translation of technical jargon into Arabic. We found that a native Arabic speaker may not have the language repertoire for technical Arabic digital terms that are not used in colloquial conversation. As many of the study participants had lower levels of English fluency, they possessed limited confidence in typing on English touch-screen keyboards and reading social media posts to find and appraise information online, while some study participants had low literacy in their first language as well. Through the application of Adult Learning Theory, navigating through the intersection of different literacies and digital competence levels means embedding person-centered approaches within group-based learning programs is essential for older immigrants as it recognizes the ways these skills are developed over individual life courses across pre-migration and post-migration contexts.

The DigComp 2.2 was a useful framework to guide exploring digital learning needs and strategies with older immigrants as it comprehensively captures all facets of digital competence. Often research with older immigrants focuses on whether they use or do not use ICTs and the reasons for using ICTs such as local integration or transnational engagement (Salma et al., Citation2021). There is limited analysis, however, on the nuanced ways digital competence contains or expands the benefits older immigrants can accrue from using ICTs. As immigrants continue to enter older age in post-migration contexts, considering frameworks such as the DigComp 2.2 is critical for expanding the ways we understand the digital divide. Digital literacy programs need to focus, not only on teaching digital competency at basic levels, but on the range of competencies that will allow older adults to become fully engaged citizens in an increasingly digitized world. The DigComp 2.2 allows for the design of digital literacy programs that address different areas of interest for older immigrants, which is also closely aligned to tenets of Adult Learning Theory. These programs must, also, incorporate co-design approaches such as the ones described in this study where older immigrants can learn what is most relevant to their lives and build on the rich life experiences they bring to digital co-learning environments.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides insights into the digital learning needs and preferences of older immigrants, especially those from Arabic-speaking communities. A limitation of the study was that older immigrants who were daily users of ICT were included, and thus perspectives of those who do not regularly use ICT were excluded and the diversity of ICT usage observed was restricted. The research team did not include experts in digital literacy and learning which might explain some of the challenges with coping with digital jargon and navigating diverse individual learning needs. The learning sessions, however, continued with the same group over time allowing for a more in-depth exploration of their digital engagement and learning needs. The co-design approach allowed for reciprocity and continued engagement of older participants who are often apprehensive about digital learning.

Conclusion

Older adults face barriers in learning how to use ICTs, including lack of access to learning opportunities, lack of motivation and digital anxiety. Digital literacy approaches that cater to language needs, offer flexible and individualized delivery formats, foster social support, and effectively address technology and sensory barriers can enhance positive attitudes toward technology use. Providing low-cost training opportunities can ensure equitable access to digital engagement for low-income older immigrants.

Appendix 3.docx

Download MS Word (23.4 KB)Appendix 2.docx

Download MS Word (18.2 KB)Appendix 1.docx

Download MS Word (17.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude and appreciation to the community organizations who have contributed generously to participant recruitment and data collection stages of the project. We are indebted to the participants of this study who generously shared their time and knowledge during the co-design process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2024.2370114

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, N. A., Abd Rauf, M. F., Mohd Zaid, N. N., Zainal, A., Tengku Shahdan, T. S., & Abdul Razak, F. H. (2022). Effectiveness of instructional strategies designed for older adults in learning digital technologies: A systematic literature review. SN Computer Science, 3(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01016-0

- Ajrouch, K. J., & Fakhoury, N. (2013). Assessing needs of aging Muslims: A focus on Metro- Detroit faith communities. Contemporary Islam, 7(3), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-013-0240-4

- Arthanat, S., Vroman, K. G., Lysack, C., & Grizzetti, J. (2019). Multi-stakeholder perspectives on information communication technology training for older adults: Implications for teaching and learning. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 14(5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1493752

- Baldassar, L., Stevens, C., & Wilding, R. (2022). Digital anticipation: Facilitating the pre-emptive futures of Chinese grandparent migrants in Australia. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(14), 1863–1879. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221075261

- Baldassar, L., Wilding, R., & Bowers, B. J. (2020). Migration, aging, and digital kinning: The role of distant care support networks in experiences of aging well. The Gerontologist, 60(2), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz156

- Barrie, H., La Rose, T., Detlor, B., Julien, H., & Serenko, A. (2021). ‘Because I’m old’: The role of ageism in older adults’ experiences of digital literacy training in public libraries. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 39(4), 379–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2021.1962477

- Barwick, C. (2017). Are immigrants really lacking social networking skills? The crucial role of reciprocity in building ethnically diverse networks. Sociology, 51(2), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515596896

- Bawden, D. (2008). Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In C. Lankshear & M. Knobel (Eds.), Digital literacies: Concepts, policies and practices (pp. 17–32). Peter Lang.

- Bhattacharjee, P., Baker, S., & Waycott, J. (2020). Older adults and their acquisition of digital skills: A review of current research evidence. 32nd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 437–443). https://doi.org/10.1145/3441000.3441053

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Canadian Arab Institute. (2013). Arab immigration to Canada hits record high. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e09162ecf041b5662cf6fc4/t/5e5c6fd9b728573d1bad10b7/1583116249563/Arab+Immigration+to+Canada+Hits+Record+High.pdf

- Chen, K., Lou, V. W. Q., & Pak, R. (2020). Measuring senior technology acceptance: Development of a brief, 14-item scale. Innovation in Aging, 4(3), igaa016. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa016

- Chen, X., Östlund, B., & Frennert, S. (2020). Digital inclusion or digital divide for older immigrants? A scoping review. In Q. Gao & J. Zhou (Eds.), Human aspects of it for the aged population. Technology and society. HCII 2020. Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 12209). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50232-4_13

- Chiu, C. J., Tasi, W. C., Yang, W. L., & Guo, J. L. (2019). How to help older adults learn new technology? Results from a multiple case research interviewing the internet technology instructors at the senior learning center. Computers & Education, 129, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.020

- Chopik, W. J. (2016). The benefits of social technology use among older adults are mediated by reduced loneliness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(9), 551–556. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0151

- Davidson, J., & Schimmele, C. (2019). Evolving internet use among Canadian citizens. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2019015-eng.htm

- Detlor, B., Julien, H., La Rose, T., & Serenko, A. (2022). Community-led digital literacy training: Toward a conceptual framework. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 73(10), 1387–1400. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24639

- Elshahat, S., & Moffat, T. (2022). Mental health triggers and protective factors among Arabic-speaking immigrants and refugees in North America: A scoping review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24(2), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01215-6

- Fang, M. L., Canham, S. L., Battersby, L., Sixsmith, J., Wada, M., & Sixsmith, A. (2019). Exploring privilege in the digital divide: Implications for theory, policy, and practice. The Gerontologist, 59(1), e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny037

- Friemel, T. N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media & Society, 18(2), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538648

- Gallagher, T. L., DiCesare, D., & Rowsell, J. (2019). Stories of digital lives and digital divides: Newcomer families and their thoughts on digital literacy. The Reading Teacher, 72(6), 774–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1794

- Georgeou, N., Schismenos, S., Wali, N., Mackay, K., Moraitakis, E., & Heyn, P. C. (2023). A scoping review of aging experiences among culturally and linguistically diverse people in Australia: Toward better aging policy and cultural well-being for migrant and refugee adults. The Gerontologist, 63(1), 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab191

- Haight, M., Quan-Haase, A., & Corbett, B. A. (2014). Revisiting the digital divide in Canada: The impact of demographic factors on access to the internet, level of online activity, and social networking site usage. Information, Communication & Society, 17(4), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.891633

- Hawkins, M. M., Holliday, D. D., Weinhardt, L. S., Florsheim, P., Ngui, E., & AbuZahra, T. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of health among older adult immigrants in the United States: An integrative review of 20 years of literature. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 755. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13042-x

- Hennebry, J., & Momani, B. (2013). Targeted transnationals: The state, the media, and Arab Canadians. UBC Press.

- Khvorostianov, N. (2016). “Thanks to the internet, we remain a family”: ICT domestication by elderly immigrants and their families in Israel. The Journal of Family Communication, 16(4), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1211131

- Khvorostianov, N., Elias, N., & Nimrod, G. (2012). ‘Without it I am nothing’: The internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media & Society, 14(4), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811421599

- Köttl, H., Allen, L. D., Mannheim, I., Ayalon, L., & Heyn, P. C. (2023). Associations between everyday ICT usage and (self-)ageism: A systematic literature review. The Gerontologist, 63(7), 1172–1187. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac075

- Kouvonen, A., Kemppainen, T., Taipale, S., Olakivi, A., Wrede, S., & Kemppainen, L. (2022). Health and self-perceived barriers to internet use among older migrants: A population-based study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 574. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12874-x

- Kvasny, L., & Keil, M. (2006). The challenges of redressing the digital divide: A tale of two U.S. cities. Information Systems Journal, 16(1), 23–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2006.00207.x

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Litchfield, I., Shukla, D., & Greenfield, S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the digital divide: A rapid review. British Medical Journal Open, 11(10), e053440. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053440

- Littlechild, R., Tanner, D., & Hall, K. (2015). Co-research with older people: Perspectives on impact. Qualitative Social Work, 14(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325014556791

- Millard, A., Baldassar, L., & Wilding, R. (2018). The significance of digital citizenship in the well-being of older migrants. Public Health, 158, 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.005

- Mitzner, T. L., Rogers, W. A., Fisk, A. D., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., Czaja, S. J., & Sharit, J. (2016). Predicting older adults’ perceptions about a computer system designed for seniors. Universal Access in the Information Society, 15(2), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0383-y

- Moore, R. C., & Hancock, J. T. (2022). A digital media literacy intervention for older adults improves resilience to fake news. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 6008. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08437-0

- Mubarak, F., & Nycyk, M. (2017). Teaching older people internet skills to minimize grey digital divides: Developed and developing countries in focus. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 15(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-06-2016-0022

- Nguyen, H. T., Baldassar, L., & Wilding, R. (2022). Lifecourse transitions: How ICTS support older migrants’ adaptation to transnational lives. Social Inclusion, 10(4), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v10i4.5735

- Nordicity. (2017). Technology access in public libraries: Outcomes and impacts for Ontario communities ( Discussion paper and interim report, prepared for the Toronto Public Library). https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/content/bridge/pdfs/nordicity-full-report.pdf

- Olmos-Vega, F. M., Stalmeijer, R. E., Varpio, L., & Kahlke, R. (2023). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide No. 149. Medical Teacher, 45(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

- Olphert, W., & Damodaran, L. (2013). Older people and digital disengagement: A fourth digital divide? Gerontology, 59(6), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353630

- Pihlainen, K., Ehlers, A., Rohner, R., Cerna, K., Kärnä, E., Hess, M., Hengl, L., Aavikko, L., Frewer-Graumann, S., Gallistl, V., & Müller, C. (2023). Older adults’ reasons to participate in digital skills learning: An interdisciplinary, multiple case study from Austria, Finland, and Germany. Studies in the Education of Adults, 55(1), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2022.2133268

- Ragnedda, M., & Muschert, G. W. (Eds.). (2013). The digital divide: The internet and social inequalities in international perspective. Routledge.

- Roque, N. A., & Boot, W. R. (2018). A new tool for assessing mobile device proficiency in older adults: The mobile device proficiency questionnaire. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816642582

- Ryan, L. (2011). Migrants’ social networks and weak ties: Accessing resources and constructing relationships post-migration. Sociological Review, 59(4), 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02030.x

- Safarov, N. (2021). Personal experiences of digital public services access and use: Older migrants’ digital choices. Technology in Society, 66, 101627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101627

- Salma, J., Ali, S., & Kaewwilai, L. (2021). Migrants’ wellbeing and use of information and communication technologies. International Health Trends and Perspectives, 1(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.32920/ihtp.v1i2.1421

- Salma, J., & Salami, B. (2020). “We are like any other people but we don’t cry much because nobody listens.”: The need to strengthen aging policies and service provision for minorities in Canada. The Gerontologist, 60(2), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz184

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schirmer, M., Dalko, K., Stoevesandt, D., Paulicke, D., & Jahn, P. (2023). Educational concepts of digital competence development for older adults—a scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6269). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136269

- Schreurs, K., Quan-Haase, A., & Martin, K. (2017). Problematizing the digital literacy paradox in the context of older adults’ ICT use: Aging, media discourse, and self-determination. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42(2), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3130

- Seifert, A., & Schelling, H. R. (2018). Seniors online: Attitudes toward the internet and coping with everyday life. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816669805

- Sen, K., Prybutok, G., & Prybutok, V. (2021). The use of digital technology for social wellbeing reduces social isolation in older adults: A systematic review. SSM - Population Health, 17, 101020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.101020

- Statistics Canada. (2023). Canada’s population estimates: Record-high population growth in 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230322/dq230322f-eng.htm

- Steelman, K., & Wallace, C. (2017). Breaking barriers, building understanding: A multigenerational approach to digital literacy instruction for older adults. ACM SIGACCESS Accessibility and Computing, 118(118), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3124144.3124146

- Sumner, J., Chong, L. S., Bundele, A., Wei, L. Y., & Heyn, P. (2021). Co-designing technology for aging in place: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 61(7), e395–e409. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa064

- Taylor, P. (2023). Smartphone penetration rate in Canada 2019-2028. https://www.statista.com/statistics/472054/smartphone-user-penetration-in-canada/

- Tomczyk, Ł., Mróz, A., Potyrała, K., & Wnęk-Gozdek, J. (2022). Digital inclusion from the perspective of teachers of older adults—expectations, experiences, challenges and supporting measures. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 43(1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2020.1824913

- Tsai, H. Y., Shillair, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2017). Social support and “playing around” an examination of how older adults acquire digital literacy with tablet computers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815609440

- Tyler, M., Simic, V., & De George-Walker, L. (2018). Older adult internet super-users: Counsel from experience. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 42(4), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2018.1428472

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2009). Guide to measuring Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000186547

- Vinson, T. (2007). Dropping off the Edge: The distribution of disadvantage in Australia. Jesuit social services and catholic social services Australia. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/125821

- Vitak, J. (2014). Unpacking social media’s role in resource provision: Variations across relational and communicative properties. Societies, 4(4), 561–586. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc4040561

- Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2: The digital competence framework for citizens: With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/490274

- Wilding, R., Gamage, S., Worrell, S., & Baldassar, L. (2022). Practices of ‘digital homing’ and gendered reproduction among older Sinhalese and Karen migrants in Australia. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 20(2), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2022.2046895

- Wynia Baluk, K., Detlor, B., La Rose, T., & Alfaro-Laganse, C. (2023). Exploring the digital literacy needs and training preferences of older adults living in affordable housing. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 41(3), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2023.2239310

- Wynia, K., McQuire, S., & Gillett, J. (2019). Comparing Australian and Canadian public library systems: A qualitative investigation of older adult public library programming and services. Macsphere. http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25102

- Zhao, L., Liang, C., & Gu, D. (2021). Mobile social media use and trailing parents’ life satisfaction: Social capital and social integration perspective. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 92(3), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020905549