ABSTRACT

Digital tools are becoming more commonly used by older adults in daily life as well as in residential care to facilitate group activities. There is, however, limited research exploring how the participants orient to the tools and whether the choice of material affects the interaction between the participants. This study investigates the use of analogue and digital communication tools in group activities with older adults aged 70–90 with and without dementia in residential care. Interactions during group activities, in which analogue and digital pictures were used to stimulate conversations, were analyzed to identify differences and similarities in how the two different tools are used, as well as any potential differences between how the two groups (persons with and without dementia) orient to the materials. The analysis shows that the use of a communication supporting tool, be it analogue or digital, promotes conversations. However, the digital condition seems to afford shared focus around the device. The results also reveal that the two participating groups orient toward the material objects in a similar fashion. Thus, the choice of material objects used in group activities has consequences for the interaction and should be taken into account when planning for group activities involving persons with and without dementia.

Introduction

The use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is becoming more common in the aging population, as seen in studies carried out in the US (Zickuhr & Madden, Citation2012), Asia (Aung et al., Citation2022) and Northern Europe (Andersson et al., Citation2023; Koiranen et al., Citation2020). This development results from a combination of the fact that a large proportion of older adults have used ICT in their working life, as well as in their private life, and continues to do so as they become older (Hunsaker et al., Hunsaker & Hargittai, Citation2018). Because of this general development concerning digital technology among older adults, an increasing number of older adults have experience of using ICT, with smartphones and computers being commonly used tools (Marston et al., Citation2016). The same is also seen in persons living with dementia (Samuelsson et al., Citation2024) and an increase in use of ICT is also seen for persons living in long-term care institutions (Seifert & Cotten, Citation2020). It has also been demonstrated that persons living with dementia position themselves as active users and learners of tablet computers in care home settings (Ingebrand et al., Citation2022).

While some research has explored the general increase in the use of ICT in the population, other studies have explored the use of technological solutions to support self-management in specific groups or groups at risk of social exclusion. A recent scoping review (Øksnebjerg et al., Citation2020) concluded that there is an urgent need for research into all essential aspects for the deliverance of applicable, effective, and sustainable assistive technology to support self-management of people with dementia. Similarly, a study of a Swedish municipality (Tsertsidis, Citation2021) showed that older adults living with dementia did not receive sufficient support or information on the possibilities of using technological solutions to manage everyday life. In a review of research on the use of tools and strategies for enhancing communication in dementia, it was concluded that social participation and person-centered communication needs more focus and that ‘training programmes targeting dyadic interaction and supporting persons with dementia from diverse ethnic backgrounds are avenues for further research’ (May et al., Citation2019, p. 857).

Related to social aspects of daily life, an increase in the use of ICT is not only seen in individuals use of digital tools but also in the use of ICT to facilitate and support conversations in group activities in care settings or residential communities for older adults (see, for instance, Ingebrand et al., Citation2023). Digital communications support, where photographs, music, and film are used as prompts to stimulate conversations, has been seen to facilitate conversations between persons with dementia and staff (Alm et al., Citation2004). Similarly, more recent research has shown how communication support applications may enhance social inclusion and active participation in communication activities in group settings with persons living with dementia (Samuelsson et al., Citation2021). Further, it is reasonable to assume that activities focusing on communication comprising use of digital communication support are beneficial also for older adults without dementia in order to promote social inclusion and participation.

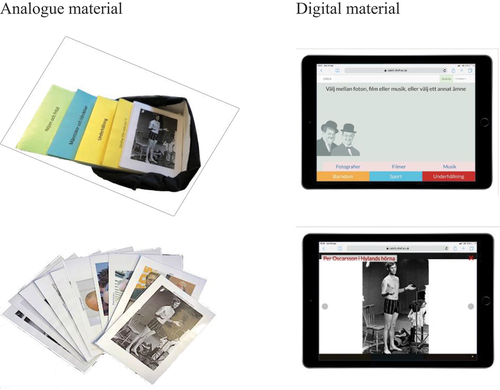

In the present study, we want to compare if there are any differences in terms of social interaction and communication depending on if older adults with and without dementia use digital communication tools or ‘analogue’ tools, in a group setting performing a conversational task, using the communicative support Computer Interactive Reminiscence and Communication Aid (CIRCA); and hence, if any of the two types of media and modalities is more beneficial for enhancing communication and social interaction. CIRCA is a web-based application created to support socialization and interaction between persons with AD and their carers (Astell et al., Citation2005, Citation2010), developed from a previous version for stand-alone devices. CIRCA is connected to a large database of pictures, videos, and music files belonging to six different main categories: childhood, sports, entertainment, recreation, people and events, and everyday life. For each main category, the photo material is sorted into five sub-categories (each item can belong to more than one category and sub-category). In the present study, we use CIRCA in its digital version as well as in an ‘analogue’ version in order to explore the differences between the use of the materials in two similar contexts. We focus on how the social interaction and communication between the participants and between the participants and the digital and ‘analogue’ tools are organized. We are especially interested in (1) if there are any differences, in the participants’ orientation toward digital and analogue communication supports; (2) if the choice of media has interactional consequences, and (3) if we can identify any differences in orientation toward the digital/‘analogue’ tools between people with and without dementia.

Material and methods

The data was collected at two residential care homes in central Sweden: one residential care home for people living with dementia, and one residential care home for people without dementia. The unit managers of each residential care home were contacted via telephone regarding the study and recruitment of participants. The contacted unit managers who showed interest received further information about the study via e-mail. Recruitment of participants was made by the unit managers. A confirmed dementia diagnosis was set as a criterion for inclusion for the group with dementia, whereas participation in the group required no known or suspected dementia. Known aphasia served as an exclusion criterion for both groups. The unit managers of each care home forwarded the e-mailed information to potential participants. The participants received information about the study verbally, by text, text supported by pictures, and in a letter of consent.

A total of eight participants were recruited: four without dementia and four with dementia. In the group of persons with dementia, there were two men and two women between 80 and 90 years of age; in the group without dementia one man and three women aged between 70 and 90 years of age participated ().

Table 1. Participants (pseudonyms) and age.

The data collection took place in two different care homes, with all participants and two study leaders sitting around a table. All conversation sessions were led by the two study leaders who acted as conversation leaders. The unit manager of the residential care home for persons living with dementia asked that one person from the ordinary staff attend three of the four sessions. The sessions took place at days and times that the unit managers considered would fit the participants best regarding alertness and not co-occur with other activities.

In each conversation session, analogue or digital communication support was used. In every other session, the communication support was analogue, and in every other session digital communication support was used. The communication support was presented by the session leaders. The web-application CIRCA was chosen as digital communication support and was presented on a tablet computer (). The analogue communication support consisted of 150 printed and laminated pictures from the different categories of pictures in CIRCA. The pictures were categorized and aimed to imitate CIRCA as much as possible (). They were printed out in the same size as the pictures on the screen in the digital material and were similar in the resolution of the images. The participants could choose from the categories Entertainment, People and events and Hobbies and spare time. In the digital sessions, the participants could also choose music or movies. After choosing the form of media, a collection of sub-categories was presented. The analogue sessions consisted of picture stimuli only. To adapt the concept of randomization in the digital communication support, where the participants chose a sub-category leading to a picture being randomly shown, the pictures in the analogue sessions were presented upside down and the participants were told to pick a random card. Even though all sessions were led by session leaders, the participants in both groups periodically used the conversation aids independently.

The data collection consisted of eight sessions, four sessions per group, which took place over a period of two weeks. All sessions were videorecorded with two video cameras of model Sony DCR-SR35 for integrated picture- and sound recording. The video cameras were mounted on tripods and placed strategically in selected places in the session room to document all communicative contributions from every participant.

During the initial analytic process, all researchers watched the recordings individually and then discussed the data jointly, and a decision was made to focus on the parts of the activities where the digital and analogue materials were equivalent in terms of content, to compare the interactional patterns of the analogue and digital setting. Hence, the focus became on the interactions that included pictures, as opposed to those in which the participants used audio- or video material (digital setting). Thereafter, the recordings were studied repeatedly and discussed in the research group, focusing on the differences and similarities seen between (a) the two material settings, and (b) the two participating groups. Transcriptions of the interactions were made to support the analytical process, according to Conversational Analytical approaches (see Appendix A for transcription conventions). The transcriptions were translated from Swedish into English after the analysis was finalized. Key sequences have been discussed in three data sessions with different experienced interactional researchers to reach consensus on the analytical focus.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by a Regional Ethical Review Board (Dnr. 2017/469–31). The illustrations of the participants are anonymized drawings from frame-grabs of the video recordings, and the names of the participants are pseudonyms.

Results

As described in the method section, the overall activity of each meeting with the two groups (persons in residential facilities with and without dementia) was organized around two types of material objects: pictures displayed through analogue versus digital means. Independently of the type of material object used, the participants take turns in choosing a picture and initiate discussions relating to the topic. In addition, both materials are built upon the same type of categories and pictures.

Despite these overall similarities, it was possible to identify a fundamental difference between the two settings in terms of how the participants handled the artifact, i.e., the physical card or the tablet computer. In the analogue setting, the participants typically hold up the card, with the card facing him/herself, thus making it difficult for the other participants to see the card. In a digital setting, the tablet computer is typically placed on the table, enabling all participants to see the content. The analogue card is passed on until all participants have held and looked at the picture individually, before it is handed on to the leader who puts it back into the box. In the digital setting, the tablet computer is handed over to the next participant, sometimes jointly with the leader, where the participant slides, or lifts up and hands over the tablet to the next participant. The tablet computer is passed on to one or several participants before it is handed over to the participant who is next in turn for him/her to choose a new category. Thus, in the digital setting, several participants can view the screen and thereby direct their attention toward it and participate in a discussion about the content.

This basic difference between how physical and digital artifacts were used, had at least two consequences for (a) how the picture category and final picture were chosen, and (b) how the participants organized the discussion about the content in the picture. In the following, we provide examples of the interaction that takes place when using both analogue and digital material regarding (a) how the picture is chosen, and (b) how the participants discuss the picture.

How was the picture chosen?

Regarding how the picture is chosen, the analogue setting typically included one of the leaders reading the categories and subcategories out loud, and the participant deciding on a final category. The box of categories and cards are then placed in front of the leader or participant, and the leader may hold up each category card for the participant who is in turn to pick a category, and the leader spreads the chosen category cards out for the participant to pick a card. In the digital setting, however, the tablet computer is placed in front of the participant, and one of the leaders or staff may support the participant in deciding on a final category, by reading out loud or letting the participant press the next category button. The leader or staff may also support the participant in pressing the button, through verbal (e.g., press again) or embodied directives (e.g., pointing). In the digital material, the picture is randomly shown once the final category button is chosen. These differences between how the material is handled when a card is chosen are similar in both groups (i.e., persons with as well as without dementia).

In order to further describe the differences and similarities between the different settings and groups with regard to how the picture is chosen, we draw upon two examples. The first example is taken from the residential care home with participants without dementia, during their third meeting. Previously, the group had one session where analogue material had been used and one session where they used a tablet computer. It is Olga’s turn to choose a picture for the group to discuss (see , picture a). Leader 1 brings this fact to attention verbally by saying Olga, and naming the categories for her to choose from, while at the same time placing the folder of cards near her, placed in such a way that Olga can see the category cards. During the process of choosing the category, Olga and leader 1 have their attention directed toward the folder, and they do not, e.g., look at each other. The group members are seated in an upright position, facing each other around the table. As Olga is choosing the card, the participants’ attention, in terms of, e.g., gaze and bodily positioning, is directed toward the leader, the folder of cards, or Olga. As such, the group members have their attention on the ongoing activity around the table and do not, for example, look around the room, and this is also the case throughout the sessions for both groups regardless of type of material. As Olga is engaged in choosing a final category, Agnes, who is seated next to her, is somewhat leaned forward with her gaze directed down on the table. As Olga draws a card, Agnes positions her body in a slightly more upheld position, and her gaze is directed to her right, on the card, as the card is drawn (see picture c), and Olga holds the card in her hand and studies the picture. The participants across the table have their gaze directed at Olga or on the table. Thus, the process of choosing an analogue card becomes an activity in which the leader guides one participant in choosing a card.

Table 2. Framegrabs from the digital and analogue settings displaying how the picture is chosen.

In the digital setting, the categories are chosen by navigating the different layers of categories, until the participant has chosen a sub-category, and the picture has appeared. In this second example, we turn to the residential home for persons with dementia. This example takes place 13 min in on the final session, and it is Valdemar’s turn to choose a category (see , picture b). Unlike the analogue material, the tablet computer is placed flat on the table, following the typical pattern for the two materials in both groups. Prior to the situation displayed in picture 2b, Valdemar is pressing the button, but the picture does not appear. He is then encouraged by leader 2 to press the button again. As this fails, leader 2 leans forward, across the table. He places his hand next to the tablet computer but does not touch the tablet computer. It is, however, not until the staff presses the button that the picture of Valdemar’s choice appears.

The differences between the bodily positioning, with the participants typically having a more lean forward position when using digital material (see 2b and 2d) compared to the analogue setting (see 2a and 2c), are seen in both participating groups. The level of engagement in terms of several persons being physically involved in the choosing of the category is also a pattern which is typically seen throughout the digital data. Even though the categories were similar in both settings, it can be worth noting that the digital device offers categories and sub-categories upon button activation, which itself may spark curiosity. In the analogue setting, it’s typically the leader who presents and sorts the category cards until a final category card is picked by the participant.

How the discussion about the picture was organized

How the participants discuss the content is also seen to vary between the different contexts. In the digital setting the group may engage in jointly describing the content in the picture once it has appeared, whereas, in the analogue setting, the participant who has drawn a specific card is more frequently seen to describe the content, e.g., by naming the famous person in the picture, without involvement from the other participants. As such, choosing a picture, as well as discussing the content, becomes more of a joint activity in the digital setting. In both settings, the group engage in conversations relating to the category/topic. As the pictures serve as prompts for conversations, the participants are sometimes more active when starting talking about some particular images, or topics, than others. This may, for example, relate to their prior knowledge of the image, or lived experiences. Below, we draw upon two excerpts, one from each setting, to exemplify the overall differences seen in the data.

In a first example of how the discussion might unfold, we again turn to the group with dementia and an analogue setting. Valdemar has chosen a card and studies the photo after he has picked it up (, transcript A, 09 pic). The rest of the group has their gaze either directed at Valdemar or down on the table. Leader 1 is reorganizing the material, and leader 2 is, unlike the rest of the group, leaning forward with his elbows and hands resting on the table (, transcript A, pic 09). Valdemar holds the photo in his hand, with the picture facing him. He makes a verbal contribution (‘(but?) it says wedding waltz,’ , transcript A, line 10), thereby acknowledging the written description that also accompanies the photo. As the leader asks Valdemar about his experiences on the topic (, transcript A, line 11), Ragnhild, who is seated across the table, leans forward and asks leader 2 to repeat what Valdemar said was on the photo (, transcript A, line 14). As she is provided with the answer, she leans back into her chair again (, transcript A, line 20). The discussion continues as the leaders support the participants in sharing their experiences. This sequence ends with the card being passed on to Erik, which is facilitated by leader 1 who takes the card from Valdemar and passes it on to Erik, thereby indicating that it is Erik’s turn to make a contribution (, transcript A, line 23). Erik looks at the photo and says ‘there yes’ before passing it on to the leader, who in turn passes it on to Nicole. During this sequence in which the card is passed on (15 s in total), the group does not engage in any verbal discussion. Once Nicole receives the card, the discussion continues whereby leader 1 asks Nicole if she has danced the wedding waltz, and she answered ‘no’ and the card is passed on to Ragnhild (, transcript A, lines 41–42). As exemplified in this sequence, the leaders play an active role in supporting the discussion, by asking the participants about their experiences relating to the topic. In the digital setting, the participants tend to rely less on the leader’s support in both groups.

Table 3. Transcripts.

This final digital example (, transcript B) is taken from an interaction between the persons without dementia and takes place during the final session, approximately 30 min in. Agnes has just pressed the button that presents her with a new picture and leader 1 points to the text above the picture and reads the names of the famous persons out loud (, transcript B, line 5). In previous sessions, Agnes has talked about her poor eyesight, which could explain why the leader reads the names for her as the picture first appears. Isabelle, who is seated across the table from Agnes, moves the kitchen roll stand as soon as the picture appears (, transcript B, line 2). Thereafter, she leans forward and places her elbows on the table, in a similar fashion as Tage. Both Tage and Isabelle have their gaze directed at the tablet computer on the table, before leaning back in their chairs. Tage has thereby been able to study the photo, as he gives a verbal contribution in line 10 (, transcript B) where he comments on which of the two famous football players in the picture is the light-haired person. Olga, who has been looking at the picture as it appears, provides a verbal contribution relating to the topic, in relation to what she has seen on the tablet computer, by saying, ‘imagine how much money they make.’ Leader 2 responds to this comment by saying, ‘do you think so?’ (, transcript B, line 16), whereupon Olga makes reference to the football players by pointing to the tablet computer and explaining that this is probably the case with these two persons at least. The tablet computer is passed on to Olga as leader 1 and Agnes jointly slide the tablet computer across the table and Olga picks the tablet up.

This final example provides an account of the general pattern of both groups in which several of the participants take part in viewing the picture and engage in a discussion about the topic. As previously mentioned, the tablet computer is more often placed on the table, visible to more participants. As such, the digital material can be seen to encroach upon the co-present participants’ personal (private or work-related) ‘space’ (Day & Rasmussen, Citation2019), which may encourage them to interact with it, especially those seated adjacent to the person operating it. When using the digital material, participants are mainly more leaned forward looking at the tablet computer, than they are when looking at the analogue pictures, as apparent from , pictures A 09 and B 02.

When using the analogue material, there are also several rather long pauses (e.g. A, line 23–24) when the participants silently look at the picture, whereas in the digital setting, this does not happen.

Discussion

In the present study, the main differences are seen between the different settings, analogue and digital communication support and not between the two groups, i.e., people with and without dementia. The challenges described in previous research regarding persons with dementia using digital technology (May et al., Citation2019; Tsertsidis, Citation2021), is not seen in this study where the digital technology was used to prompt casual conversations in group settings. As such, factors such as previous experience of the use of digital technology, support provided, and the reason for the use of a certain digital technology, may affect the potential challenges that arise. The advantages of digital communication tools have been pointed out in previous research (e.g., Astell et al., Citation2010), and results of the present study indicate that the digital setting is used similarly by the older participants regardless of whether they have a cognitive decline, such as dementia, or not.

In more general terms, our results indicate that when participants conduct an activity organized around a material artifact, they can make use of the artifact in many ways, and artifacts can constrain as well as facilitate some uses. At least three distinct ways of using the artifacts could be identified.

First, the participants treated the analogue card or the digital screen as transactional artifacts to be touching, grasping, holding, showing the artifactfor instance, grabbing the artifact and passing it on to another participant. Transactions of the artifact can be used as a way to direct other participants’ attention (by showing or hiding the artifact) (Clark, Citation2005), and a way to indicate that they want or have the right to have a turn or make a contribution to the activity (Day & Rasmussen, Citation2019; Day & Wagner, Citation2014).

Second, the participants treated the analogue card or the digital screen as practical artifacts to be manipulated for practical usefor instance, clicking on a tablet screen or selecting a photo among many other photos. In the case of dynamic artifacts, the manipulation and change of the artifact can open for a new class of actions or a change in the activity (Lehtinen & Pälli, Citation2021; Mikkola & Lehtinen, Citation2014).

Thirdly, the participants made use of the artifacts’ semantic possibilities: they talked about what they saw on the card or the screen, both using verbal representations as well as deictic gestures (pointing to the artifact) as part of ongoing talk (Aaltonen et al., Citation2014).

Subsequently, the different uses that the artifact opens for have consequences for the organization of the interaction. Artifact transactions can have direct consequences for the interaction as when a participant handles the artifact in such a way that others cannot see it or when changes in the artifact are used to change the topic or direction of the ongoing conversation. As demonstrated by our results, there are differences between the digital and the analogue setting, but these differences do not necessarily mean that one setting is better than the other. The use of communication supporting artifacts, be it analogue or digital, promotes conversation, but the digital condition seems to afford shared focus around the device, while the analogue pictures may enhance the possibilities for each participant to get a close look at the pictures. Thus, being aware of these differences, an activity leader may choose setting in an informed, and conscious way.

In sum, we have described a group activity focusing on conversation involving older adults aged 70–90 with and without dementia. The activity is centered around communication support, either in digital form on a tablet computer or in the form of an analogue, traditional photo. The results demonstrate that the activity promotes social interaction in both settings, but that the digital communication support enhances active and joint participation to a greater extent than the analogue pictures. These results have clinical implications for the choice of activity in elder care, as well as for the choice of using digital or analogue communication support.

The fact that the digital setting works well for participants both with and without dementia means that the digital communication support, which also has practical advantages, e.g. the need for preparative work in finding and choosing pictures for an activity, is less laborious, and the flexibility for adding or changing pictures during an activity is greater, and can be used with both groups of participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants for taking part in the communication sessions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaltonen, T., Arminen, I., & Raudaskoski, S. (2014). Photo sharing as a joint activity between an aphasic speaker and others. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects. Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 125–144). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Alm, N., Astell, A., Ellis, M., Dye, R., Gowans, G., & Campbell, J. (2004). A cognitive prosthesis and communication support for people with dementia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 14(1–2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010343000147

- Andersson, J., Blomdahl, F., & Bäck, J. (2023). Svenskarna och Internet 2023. [The swedes and internet 2023]. Internetstiftelsen. internetstiftelsen-svenskarna-och-internet-2023.pdf (svenskarnaochinternet.se)

- Astell, A. J., Ellis, M. P., Alm, N., Dye, R., Gowans, G., & Campbell, J. (2005). Using hypermedia to support communication in Alzheimer’s disease: The CIRCA project. In D. Schmorrow (Ed.), Foundations of augmented cognition (pp. 758–767). Elsevier.

- Astell, A. J., Ellis, M. P., Bernardi, L., Alm, N., Dye, R., Gowans, G., & Campbell, J. (2010). Using a touch screen computer to support relationships between people with dementia and caregivers. Interacting with Computers, 22(4), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2010.03.003

- Aung, M. N., Koyanagi, Y., Nagamine, Y., Nam, E. W., Mulati, N., Kyaw, M. Y., Moolphate, S., Shirayama, Y., Nonaka, K., Field, M., Cheung, P., & Yuasa, M. (2022). Digitally inclusive, healthy aging communities (DIHAC): A cross-cultural study in Japan, Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 6976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126976

- Clark, H. H. (2005). Coordinating with each other in a material world. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 507–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054404

- Day, D., & Rasmussen, A. S. (2019). Interactional consequences of object possession in institutional practices. In D. Day & J. Wagner (Eds.), Objects, bodies and work practice (pp. 87–112). Multilingual Matters.

- Day, D., & Wagner, J. (2014). Objects as tools for talk. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with things: The sociality of objects (pp. 101–124). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hunsaker, A., & Hargittai, E. (2018). A review of internet use among older adults. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3937–3954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818787348

- Ingebrand, E., Samuelsson, C., & Hydén, L. C. (2022). People living with dementia collaborating in a joint activity. Learning, Culture & Social Interaction, 34, 100629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100629

- Ingebrand, E., Samuelsson, C., & Hydén, L. C. (2023). Supporting people living with dementia in novel joint activities: Managing tablet computers. Journal of Aging Studies, 65, Article 101116. 101116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2023.101116

- Koiranen, I., Keipi, T., Koivula, A., & Räsänen, P. (2020). Changing patterns of social media use? A population-level study of Finland. Universal Access in the Information Society, 19(3), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-019-00654-1

- Lehtinen, E., & Pälli, P. (2021). On the participatory agency of texts: Using institutional forms in performance appraisal interviews. Text & Talk, 41(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2019-0121

- Marston, H. R., Kroll, M., Fink, D., de Rosario, H., & Gschwind, Y. J. (2016). Technology use, adoption and behavior in older adults: Results from the iStoppfalls project. Educational Gerontology, 42(6), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1125178

- May, A. A., Dada, S., & Murray, J. (2019). Review of AAC interventions in persons with dementia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(6), 857–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12491

- Mikkola, P., & Lehtinen, E. (2014). Initiating activity shifts through use of appraisal forms as material objects during performance appraisal interviews. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects. Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 57–78). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Øksnebjerg, L., Janbek, J., Woods, B., & Waldemar, G. (2020). Assistive technology designed to support self-management of people with dementia: User involvement, dissemination, and adoption. A scoping review. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(8), 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219001704

- Samuelsson, C., Ferm, U., & Ekström, A. (2021). “It’s our gang” - promoting social inclusion for people with dementia by using digital communication support in a group activity. Clinical Gerontologist, 44(4), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2020.1795037

- Samuelsson, C., Lindeberg, S., Majlesi, A. R., & Hydén, L.-C. (2024). [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of clinical science, intervention and technology, Karolinska Institutet.

- Seifert, A., & Cotten, S. R. (2020). In care and digitally savvy? Modern ICT use in long-term care institutions. Educational Gerontology, 46(8), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2020.1776911

- Tsertsidis, A. (2021). Challenges in the provision of digital technologies to elderly with dementia to support ageing in place: A case study of a Swedish municipality. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(7), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1710774

- Zickuhr, K., & Madden, M. (2012). Older adults and internet use. Pew Internet and American Life Project, 6, 1–23.