ABSTRACT

Emotional intelligence includes an assortment of factors related to emotion function. Such factors involve emotion recognition (in this case via facial expression), emotion trait, reactivity, and regulation. We aimed to investigate how the subjective appraisals of emotional intelligence (i.e. trait, reactivity, and regulation) are associated with objective emotion recognition accuracy, and how these associations differ between young and older adults. Data were extracted from the CamCAN dataset (189 adults: 57 young/118 older) from assessments measuring these emotion constructs. Using linear regression models, we found that greater negative reactivity was associated with better emotion recognition accuracy among older adults, though the pattern was opposite for young adults with the greatest difference in disgust and surprise recognition. Positive reactivity and depression level predicted surprise recognition, with the associations significantly differing between the age groups. The present findings suggest the level to which older and young adults react to emotional stimuli differentially predicts their ability to correctly identify facial emotion expressions. Older adults with higher negative reactivity may be able to integrate their negative emotions effectively in order to recognize other’s negative emotions more accurately. Alternatively, young adults may experience interference from negative reactivity, lowering their ability to recognize other’s negative emotions.

Introduction

Emotional intelligence has been shown to be associated with higher levels of well-being along with overall better functioning in life (Sánchez-Álvarez, Extremera, & Fernández-Berrocal, Citation2016). There are multiple constructs to measure emotional intelligence, one of which is derived from the integrative model of “ability emotional intelligence” (Mayer & Salovey, Citation1997; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, Citation1999; Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, Citation2008; Tsaousis & Kazi, Citation2013). This measures top end individuals’ performances to (i) accurately identify emotions, (ii) demonstrate awareness of the situations that contribute to those emotions, and (iii) enact adaptive responses. This model seems to be most beneficial when assessing different cognitive domains from an objective perspective since other emotional intelligence theories such as Bar-On’s mixed model emotional intelligence theory and the trait emotional intelligence theory put less emphasis on the cognitive aspects and more on “non-cognitive” subjective ratings of the individual’s capabilities (Bar-On, Citation2004; Di Fabio & Saklofske, Citation2014; Hogeveen, Salvi, & Grafman, Citation2016; Petrides & Furnham, Citation2001). There have been moderate correlations between the two measurements using each of these models (Di Fabio & Saklofske, Citation2014). Furthermore, investigations into which specific factors affect emotional intelligence have been conducted: using the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso emotional intelligence integration model (Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, Citation2003), Cabello, Sorrel, Fernández-Pinto, Extremera, and Fernández-Berrocal (Citation2016) found that the overall “ability emotional intelligence” follows an inverted U pattern across the lifespan, indicating that age does have an impact on overall “ability emotional intelligence” while Van Rooy, Alonso, and Viswesvaran (Citation2005) reported that trait emotional intelligence tended to increase with age. Chen, Peng, and Fang (Citation2016) also found that emotional intelligence impacts the association between age and reported well-being.

One important element of emotional intelligence is emotion recognition ability and one aspect of being able to identify emotions in others is through facial expressions. Facial emotion recognition ability in humans has continued to be explored since Paul Ekman’s study that theorized that humans, across cultures, can consistently identify basic emotions in facial expressions (Ekman & Friesen, Citation1971). Emotional expressions via “facial, bodily, vocal, verbal, and/or symbolic” elements and the perception thereof, are key contributors to aiding social interaction where inferences made about the individual expresser, the self of the observer, and the corresponding circumstances which facilitate adaptive behavior (Lange, Heerdink, & van Kleef, Citation2022). Therefore, the perception of, or rather the ability to accurately recognize emotional expression, may be individually associated with one’s well-being (Carton, Kessler, & Pape, Citation1999; Hall, Horgan, & Murphy, Citation2019; Ruffman, Zhang, Taumoepeau, & Skeaff, Citation2016; Schmid Mast & Hall, Citation2018). Conversely, inaccuracies in emotion recognition ability have been associated with the inability to identify appropriate versus inappropriate behavior and higher levels of psychological distress (Csukly, Czobor, Simon, & Takács, Citation2008; Ruffman, Zhang, Taumoepeau, & Skeaff, Citation2016). Investigations of emotion recognition ability throughout the years have taken on a more nuanced view depending on characteristics of the observer, the faces being observed, and the specific emotions being perceived (Elfenbein & Ambady, Citation2002; Isaacowitz, Livingstone, & Castro, Citation2017). Specifically, when evaluating the factor of emotion recognition within the framework of emotional intelligence, one characteristic that appears to influence emotion recognition ability is age. It has been found that there is a decline in recognition for fear starting in the 40s, and for anger starting in the 50s (Calder et al., Citation2003), while others found emotion recognition ability decline starting around 60 years old (Olderbak, Wilhelm, Hildebrandt, & Quoidbach, Citation2019; West et al., Citation2012). Older adults have shown less accuracy when viewing nonverbal static pictures, specifically negative expressions (Isaacowitz et al., Citation2007; Murphy & Isaacowitz, Citation2010; Ruffman, Sullivan, & Dittrich, Citation2009; Sasson et al., Citation2010; Sullivan, Campbell, Hutton, & Ruffman, Citation2017; Sullivan, Ruffman, & Hutton, Citation2007; West et al., Citation2012). Though some studies have found that specific tasks, like those with background information or dynamic interactions between participant and stimuli, reduce some of the age effects (Richter, Dietzel, & Kunzmann, Citation2011; Sze, Goodkind, Gyurak, & Levenson, Citation2012). Others have found even when context, audio, and/or dynamic movements were added, older adults generally performed worse at recognizing emotions, especially negative emotions (Birmingham, Svärd, Kanan, Fischer, & Hsiao, Citation2018; Cortes et al., Citation2021; Lima, Alves, Scott, & Castro, Citation2014; Spencer, Sekuler, Bennett, Giese, & Pilz, Citation2016). This goes along with the trend that as adults age, they reduce their social networks to the most familiar and emotionally beneficial relationships where attention can be focused on positive situations (Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST)) (Carstensen, Citation2006; Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, Citation1999; Hh, Ll, & Fr, Citation2001; Yeung, Fung, & Lang, Citation2008). Even though older adults seem to prefer the company of familiar people, being able to accurately recognize the emotions of strangers using non-verbal cues would seem to be beneficial (Hall, Horgan, & Murphy, Citation2019).

Another important aspect of emotional intelligence is emotion reactivity which stems from an appraisal the individual makes subjectively in response to an either perceived negative or positive stimulus (Lazarus, Citation1991; Levenson, Citation1999). Age also appears to be a factor in emotion reactivity levels . Some studies have found that older adults subjectively react to high arousal positive stimuli less favorably and high arousal negative stimuli more aversively, respectively, compared to younger adults (Fernández-Aguilar et al., Citation2020; Keil & Freund, Citation2009; Schweizer et al., Citation2019). Conversely, even though older adults tend to appraise stimuli as more positive than young adults (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2010), Hudson, Lucas, and Donnellan (Citation2016) found that older adults react less intensely to both negative and positive experiences, with the caveat being that the oldest adults begin to “rebound” in their positive reactivity intensity. Older adults have also reported greater subjective sadness reactivity (Gould, Gerolimatos, Beaudreau, Mashal, & Edelstein, Citation2018; Kunzmann & Grühn, Citation2005) but have also reported lower levels of “self-conscious” negative emotions like shame (Henry, von Hippel, Nangle, & Waters, Citation2018). It has also been shown that higher negative reactivity to death-related stimuli was associated with higher emotion recognition ability in older adults (Katzorreck & Kunzmann, Citation2018). Age and negative reactivity seem to have a complex relationship in how negative expressions are perceived, which is not yet fully understood (Deckert, Schmoeger, Auff, & Willinger, Citation2020). Overall, it seems that older adults appear to be more heterogenous in their reactivity response to negative stimuli than young adults (Kliegel, Jäger, & Phillips, Citation2007) and attempt to disengage from negative scenarios when possible (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2008). Along with emotion reactivity, emotion regulation has also been studied across adulthood, where older adults were less effective than young adults with “negativity reduction” emotion regulation strategies and had a more difficult time reducing their negative feelings (Livingstone & Isaacowitz, Citation2021; Schweizer et al., Citation2019). In this context, it has been suggested that older adults may find it more difficult to use negative detachment or reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy when negative stimuli cannot be avoided or changed; though positive reappraisal of negative stimuli may be easier for older adults since it seems to require less cognitive load (Opitz, Rauch, Terry, & Urry, Citation2012; Shiota & Levenson, Citation2009). The cognitive reappraisal method has not been shown to affect aspects of facial recognition (Megreya, Latzman, & Hills, Citation2020), but this has not been tested with facial emotion recognition and aging to our knowledge. The dynamic nature of these aforementioned subjective intrapersonal and objective interpersonal emotional abilities suggests there could be associations between them. Lastly, there has been research on how intrapersonal emotions affect emotion recognition ability such as social anxiety being associated with misinterpreting lower intensity emotional expression in others as negative (Button, Lewis, Penton-Voak, & Munafò, Citation2013), and depression being associated with less accurate emotion recognition (Demenescu, Kortekaas, Boer, Aleman, & Harrison, Citation2010; Kessler, Roth, von Wietersheim, Deighton, & Traue, Citation2007). However, the degree to which anxiety and depression interact with age to impact emotion recognition has not been as extensively studied to our knowledge.

Emotion recognition and emotion reactivity has been studied in conjunction with patient populations with neurological conditions (Crivelli et al., Citation2021; Werner et al., Citation2007), while emotion recognition in conjunction with emotion regulation has been studied with children (Schaan et al., Citation2019) and individuals with anorexia (Harrison, Sullivan, Tchanturia, & Treasure, Citation2009; Harrison, Tchanturia, & Treasure, Citation2010). To our knowledge there is little research on how a specific objective measure of ability emotional intelligence, such as emotion recognition, is associated with subjective emotional intelligence measures in differing age groups. Given that older adults prefer to change their approach to engaging with negative stimuli and specifically prefer to avoid negative relationships per the SST, one would expect differences in how young and older adults react to negative stimuli and how they perceive negative emotions in others since both negative stimuli and a negative face can fall under the banner of a negative situation (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2008). Furthermore, since older adults experience more complex negative and positive emotions, those who have higher negative reactivity could have better integration of emotions per the Dynamic Integration Theory (DIT), thus cognitively be able to identify emotions of others, whereas young adults may not have this integration effect (Labouvie-Vief, Citation2003). Lastly, older adults’ positivity bias may be attenuated when they cannot avoid a negative situation and may have to draw on their plethora of past experience to navigate their own and other’s emotions (i.e. changing their appraisal) as posited by the Strength and Vulnerability Integration (SAVI) theory, stating that young adults do not have as much experience to draw on when faced with negative situations (Charles, Citation2010).

In this context, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the effects and interaction of age on the association between subjective intrapersonal emotions (anxiety, depression, emotion reactivity, and emotion regulation via cognitive appraisal) and objective interpersonal emotion intelligence ability, specifically emotion recognition ability, as both objective ability and subjective appraisals within emotion intelligence may be correlated (Di Fabio & Saklofske, Citation2014; Young, Minton, & Mikels, Citation2021). To do so, we utilized the behavioral data from healthy adult individuals participating in the Cambridge Center for Ageing and Neuroscience project, from 18 to 88 years old (CamCAN; (Shafto et al., Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2017)). We identified two age groups, one comprised of young adults and the other comprised of older adults. We tested the main effects of age group and intrapersonal emotions as well as their interactions on emotion recognition ability via linear regression analyses. We hypothesized that (1) in multiple emotion recognition conditions, except for happiness, negative reactivity will predict emotion recognition in older adults but not young adults, while positive reactivity will predict emotion recognition in young adults but not older adults (Hudson, Lucas, & Donnellan, Citation2016; Katzorreck & Kunzmann, Citation2018); (2) positive reappraisal will predict emotion recognition ability in older adults, but not young adults (Livingstone & Isaacowitz, Citation2021; Schweizer et al., Citation2019); and (3) depression, but not anxiety, will predict worse emotion recognition ability in young adults but not older adults, as depression has been shown to have a more significant impact in young adults than in older adults (Kessler, Roth, von Wietersheim, Deighton, & Traue, Citation2007; Orgeta, Citation2014). As a sub-analysis, we expected possible differences of associations predicting emotion recognition ability between a “younger-old” and an “older-old” age groups (Calder et al., Citation2003).

Materials and Methods

Sample Selection

The CamCAN study used an epidemiologically informed recruitment framework and is available upon request (https://www.cam-can.org/; Shafto et al., Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2017). It includes a total of 652 individuals (330 females, age range: 18–88 years). Ethical approval for the CamCAN study was obtained from the Cambridgeshire 2 (now East of England-Cambridge Central) Research Ethics Committee. Participants gave full informed consent. From this cohort, we selected two subsets of participants: one composed of young adults (N = 138; mean (sd) age = 28.66 (4.94) years; age range: 18–35 years; 77 females), and one composed of older adults (N = 303; mean (sd) age = 73.38 (7.53) years; age range: 60–88 years; 150 females). These age cutoffs were selected based on previous studies suggesting that major age changes related to emotion recognition start at approximately 60 years old (Calder et al., Citation2003; Olderbak, Wilhelm, Hildebrandt, & Quoidbach, Citation2019; West et al., Citation2012).

A power analysis showing that using a linear multiple regression analysis, a minimum sample of 81 participants total was needed to detect a modest effect size of f2 = 0.1, with a power of 80% at α = 0.05, therefore we were confident that with our final sample of 175 individuals would achieve significant findings.

Subject Exclusion

We further excluded participants: (a) who had missing data or outliers (>3 sds above the mean) in any of the variables extracted from the emotion reactivity and regulation task (detailed below; n = 81 within the young adults, n = 181 for the older adults), and (b) extreme high anxiety or depression based on the Hospital and Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, >3 sds above the mean, n = 4) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983), which has been described to have a significant impact on emotion recognition abilities (Aldinger et al., Citation2013; Fox, Russo, & Georgiou, Citation2005; Kessler, Roth, von Wietersheim, Deighton, & Traue, Citation2007; Wenzler et al., Citation2017). This resulted in a final sample of 57 young adults (mean (sd) age = 28.91 (4.96) years; age range: 18–35 years; 33 females; White: N = 54, Black African: N = 1, unknown = 2) and 118 older adults (mean (sd) age = 72.64 (7.33) years; age range: 60–87 years; 57 females; White: N = 111, Asian: N = 5, unknown: N = 2). Statistical analyses involved subsamples based on available data after excluding outliers in any of the variables related to the emotion recognition task (more or less than 3 standard deviations from the mean, see Supplementary Table S1).

Affective assessments

Participants’ level of anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the HADS (the HADS does only measure within the past week but will still be defined as trait) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). See Connolly, Young, and Lewis (Citation2021) and Shafto et al. (Citation2014) for all details related to these assessments. The participants’ emotion recognition ability was assessed using the Ekman’s emotion recognition hexagon test (Ekman & Friesen, Citation1971; Young et al., Citation1997, 2002), and their emotion reactivity and regulation were assessed using a film-based model (Schweizer et al., Citation2016; Schweizer, Grahn, Hampshire, Mobbs, & Dalgleish, Citation2013). Below, we provide a short description of each task.

Variable Selection

Emotion Recognition Task

Seven emotion recognition accuracy scores (as seen in ) were extracted from the Ekman’s Emotion Hexagon test (Young et al., Citation1997; Young, Perrett, Calder, Sprengelmeyer, & Ekman, Citation2002). This test was created using a model from the Ekman and Friesen (Citation1971) “Pictures of facial affect” series which presented each of the six basic emotions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise). These prototypical emotion images were then morphed with another basic emotion to form emotional expressions with graded levels of difficulty (expression pairs morphed together consist of happiness-surprise, surprise-fear, fear-sadness, sadness-disgust, disgust-anger, and anger-happiness). Participants were shown faces with either 70% or 90% of the target emotion and had to indicate whether the emotion being expressed was most like anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, or surprise through a six-option forced choice paradigm. There were 20 trials for each of the six emotions, and stimuli were shown for 3 s each. The number of correct responses for each of the six categories of emotion (i.e., anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise), in addition to a total emotion recognition score were extracted for further analyses (as seen in ).

Table 1. Description of the variables of interest.

Emotion Reactivity and Regulation Task

Four measures of emotion reactivity and regulation were extracted based on the task by Goldin, McRae, Ramel, and Gross (Citation2008) and adapted by Schweizer, Grahn, Hampshire, Mobbs, and Dalgleish (Citation2013) (). In this task, participants were instructed to view 38 positive, neutral, and negative film clips and rated their emotional responses after each. In addition, for some of the negative films, they were asked to reappraise the film content by reinterpreting its meaning in order to reduce the emotional impact. The experiment consisted of eight experimental blocks, each containing four experimental trials from one of the four main conditions: (1) watch neutral, (2) watch positive, (3) watch negative, or (4) reappraise negative. For each trial, participants received a prompt to indicate the valence and how they should observe the film (e.g. “WATCH NEUTRAL” or “REAPPRAISE NEGATIVE”). Following each type of film clip, participants provided ratings on a 11-point scale: they rated how negative and positive they felt while watching the films where “0” was rated as “extremely negative” and “10” was rated as “extremely positive,” respectively. From this scale, negative and positive reactivity scores were computed as the difference in ratings during the watching of negative (or positive) clips and of neutral clips (as seen in ). Additionally, negative and positive reappraisal scores were computed. These scores reflected how well people regulated their negative (or positive, respectively) emotions during the negative reappraisal condition, compared to the watch condition of negative clips ().

Anxiety and Depression Scores

Participants’ anxiety and depression scores were extracted from the HADS. The HADS has 14 items assessing for either anxiety symptoms or depressive symptoms. Participants rate either 0, 1, 2, or 3 for each corresponding statement as an answer to complete each main statement. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety and/or depressive symptoms (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983).

Statistical Analyses

Since education (de Souza et al., Citation2018; Mill, Allik, Realo, & Valk, Citation2009), sex (Campbell, Ruffman, Murray, & Glue, Citation2014; Kret & De Gelder, Citation2012; Olderbak, Wilhelm, Hildebrandt, & Quoidbach, Citation2019; Sullivan & Ruffman, Citation2004; Sullivan, Campbell, Hutton, & Ruffman, Citation2017), and age (Isaacowitz et al., Citation2007; Ruffman, Henry, Livingstone, & Phillips, Citation2008; Sasson et al., Citation2010; West et al., Citation2012) have been shown to influence emotion recognition ability, we regressed them out from each of the 13 measures selected using linear regression analyses. These residualized values were used as inputs for the following analyses.

Independent Samples T-Tests

We first investigated differences between the two age groups in the emotion recognition, trait, and reactivity and regulation variables via independent sample t-tests. Significant results are reported at p < .05, after applying a false-discovery rate (FDR) correction.

Linear Regression Models

Second, we investigated the impact of emotion reactivity, regulation, anxiety and depression on emotion recognition ability and how age influenced these relationships. For this, we conducted linear regression analyses, using the young group as our reference group. For each analysis we used one of the seven emotion recognition scores (total correct emotion recognition, correct anger recognition, correct disgust recognition, correct fear recognition, correct happiness recognition, correct sadness recognition, and correct surprise recognition) as the dependent variable, with age group (young, older) as a fixed factor, and the emotion trait, reactivity and regulation variables (positive reactivity, negative reactivity, positive reappraisal, negative reappraisal, anxiety and depression) as covariates. For each model we included both main effect of each variable and its interaction with age group. When an interaction was statistically significant, we further investigated the difference in linear trends between the two age groups. Beta scores were from the sample and results were corrected using a FDR correction. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.1.

Supplementary Analyses

When a significant interaction with the age group was revealed, we conducted follow-up analyses to investigate whether further age differences may arise within the older group, by splitting it between a “younger-old” group (age range: 60–74, n = 78) and an “older-old” group (75–88, n = 54). To do so, we re-conducted the analyses with the three age groups and specifically tested the interaction between the younger-old and the older-old groups in order to ascertain on whether there was differing effects within very late adulthood.

Results

There was no significant difference between the two groups for any of the variables investigated after age, sex, and education had been regressed out, even at an uncorrected p-value (as seen in ).

Table 2. Description of the 13 variables within each age group.

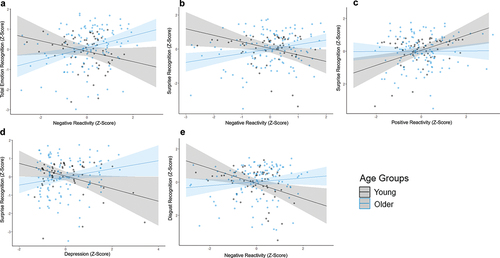

Regression analyses revealed a significant age group-by-negative reactivity interaction to predict the total correct emotion recognition score (t(171) = 3.00; p = .003 (FDR = 0.041)). In detail, there was a negative association for the young age group (Beta = −0.26; 95% CI = −0.59, 0.066) and a positive association for the older age group (Beta = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.13, 0.47; as seen in ). No other variables were statistically significantly associated with total correct emotion recognition scores after applying a FDR correction (as seen in Supplementary Table S2).

Analyses revealed a significant age group-by-negative reactivity interaction predicting correct surprise recognition (t(171) = 3.44; p = .0007 (FDR = .024)) where there was a negative association for the young group (Beta = −0.38; 95% CI = −0.71, −0.06) and a positive association for the older group (Beta = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.09, 0.44; as seen in ). Furthermore, we also found a significant age group-by-positive reactivity interaction predicting correct surprise recognition (t(171) = −2.54; p = .01 (FDR = .026)), where there was a strong positive association for the young group (trend = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.16, 0.76), but not for the older group (Beta = 0.008; 95% CI = −0.17, 0.19; as seen in ). Analyses also showed a significant age group-by-depression interaction (t(171) = 2.86; p = .005 (FDR = 0.021)) where there was a negative association for the young group (Beta = −0.35; CI = −0.68, −0.01) and a positive association for the older group (Beta = 0.22; CI = 0.01, 0.43; as seen in ). Lastly, we found a significant main effect of negative reactivity (t(171) = −3.002; p = .003 (FDR = 0.021)), positive reactivity (t(171) = 2.85; p = .005 (FDR = 0.021)), and depression (t(171) =-2.59; p = .01 (FDR = 0.026), as seen in Supplementary Table S2).

The analyses also revealed a significant age group-by-negative reactivity interaction predicting correct disgust recognition (t(171) = 2.9; p = .004 (FDR = 0.033)) where there was a negative association for the young group (Beta = −0.45; 95% CI = −0.80, −0.110) and a positive association for the older group (Beta = 0.12; 95% CI = −0.07, 0.30, as seen in ). We also detected a main effect of negative reactivity (t(171) = −2.85; p = .005 (FDR = 0.033), as seen in Supplementary Table S2).

Once FDR corrected, there were no other statistically significant results for the models related to anger, fear, happy, or sadness recognition variables (as seen in Supplementary Table S2).

Lastly, we re-conducted the analyses to test further age differences within the older group among the significant models. We did not detect any statistically significant interactions between the younger-old group and older-old group.

Discussion

The current study investigated how subjective appraisals of intrapersonal factors of emotional intelligence are associated with objective ratings of facial emotion recognition, and how these associations differ between young versus older healthy adults. To do this, we used the CamCAN dataset and analyzed factors involved in emotional intelligence, specifically, emotion traits such as anxiety and depression, subjective emotion reactivity scales, reappraisal emotion regulation scales, using an updated morphed Ekman’s emotion recognition task. We found that negative reactivity was positively associated with the total correct emotion recognition category, along with the sub-categories of disgust and surprise in older adults, while the young adults showed a negative association. With respect to surprise recognition, older adults showed a positive association with depression while young adults showed a negative association. Young adults also showed a positive association between positive reactivity and recognition of surprise, which was not the case in the older adults. Lastly, we did not detect any significant difference in these associations when we compared the early older adulthood and late adulthood, suggesting that in our sample, intrapersonal emotions impact on their ability to recognize emotions was not altered throughout late adulthood.

The total correct emotion recognition score was composed of decidedly negative emotions (anger, disgust, sadness, fear) and was most likely driven by these emotions. We believe this may explain why we found a relatively common relationship with negative reactivity as a major predictor across the total correct emotion score and some emotion subcategories. The older and young adults having shown opposite relationships with negative reactivity led us to two possible interpretations. The first interpretation is in line with the SAVI theory, which is similar to SST in that it uses some of the same principles (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2010). It posits that older adults learn through experience to avoid negative situations preemptively in order to have higher positivity and are generally involved in relationships that promote positive emotions, as they view positive stimuli as more pertinent (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, Citation1999; Charles & Carstensen, Citation2010). Based on this theory, older adults are generally more likely to appraise or evaluate stimuli as more positive rather than negative compared to young adults (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2010) and therefore, become less sensitive to and avoid negative emotional experiences (Carstensen & Mikels, Citation2005). The difference with the SAVI theory is that it posits that older adults also draw upon their more extensive past experience compared to young adults when they are faced with negative situations along with employing avoidance or situation changing strategies in the present moment (Charles, Citation2010). So, the older adults who had less negative reactivity and lower emotion recognition accuracy may have viewed negative stimuli as less pertinent to their lives in order to not have to regulate an elevated level of distress as posited by SAVI (Charles & Luong, Citation2013), thus lowering their accuracy scores on the recognition task.

Oppositely, older adults who scored higher on negative reactivity may have had higher accuracy for the emotion recognition task because they remained sensitive to negative stimuli. Katzorreck and Kunzmann’s (Citation2018) study supports this interpretation, where older adults who experience greater negative reactivity, specifically to death-related stimuli in their case, may have more empathic relations to perceived negativity in others, thus recognizing other’s negative emotions. Though Katzorreck and Kunzmann (Citation2018) revealed this was only the case for just death-related negative stimuli, our study suggests it may be the case for other negative stimuli, too. As for young adults, there may be more interference of comprehension for other’s negative emotions when they are more prone to higher subjective negative reactivity (Blanchard-Fields, Jahnke, & Camp, Citation1995). Conversely, some have disputed that emotion recognition ability differences in older adults arise from the dynamics undergirding SAVI and SST (Mill, Allik, Realo, & Valk, Citation2009). Alternative theories typically have to do with neuropsychological factors (Ruffman, Henry, Livingstone, & Phillips, Citation2008). One such theory that promotes neuropsychological factors as a basis is the DIT, which suggests some older adults may not have the cognitive capabilities to integrate or switch between both negative and positive emotions, so they focus on positive stimuli and emotions because it is simpler (Labouvie-Vief, Citation2003). Our findings at least in part, may be explained by the DIT, where older adults who have higher subjective negative reactivity are still able to cognitively integrate positive and negative emotions, thus being also able to recognize negative emotions in others better. In contrast, the older adults who had lower negativity reactivity and lower emotion recognition accuracy may have mainly focused on positive stimuli due to their possible diminishing cognitive capabilities resulting in a reduced ability to fully integrate negative emotions.

We also found that surprise recognition was predicted by the level of depression in each age group, where older adults showed a positive association and young adults showed a negative association. Surprise recognition shows larger levels of inter-subject variability (compared to the other emotions) as it can be viewed as either negative, complex with negative and positive, or positive. Other studies have suggested that the interpretation of surprise is related to what event the perceiver came up with in their mind that preceded the surprise reaction (i.e. was it a positive, negative, or complex preceding event) (Kohler et al., Citation2003) which could conceivably be associated with a greater variability of intrapersonal emotions that influence surprise recognition accuracy. Negative reactivity could make older adults more sensitive to the perception of the surprise emotion if they perceived the surprise expression to be negative and related to them (Katzorreck & Kunzmann, Citation2018). Young adults with higher negative reactivity may have appraised surprise differently, and incorrectly, since they are not drawing upon as many past experiences to help them distinguish a potentially complex emotion, which would be in line with the SAVI theory (Charles, Citation2010; Young, Minton, & Mikels, Citation2021). Next, older adults typically react less intensely to positive stimuli compared to young adults (Fernández-Aguilar et al., Citation2020; Schweizer et al., Citation2019). So, this ability to react more intensely to positive stimuli in young adults helped them identify an emotion like surprise if they viewed surprise as positive, where this would not make a difference in the older adults and may actually assist in their ability to maintain well-being (Grosse Rueschkamp, Kuppens, Riediger, Blanke, & Brose, Citation2020). Lastly, depressive symptoms among young adults have been shown to be associated with lower emotional intelligence, so the directionality in the surprise condition in the current study follows that trend (Navarro-Bravo, Latorre, Jiménez, Cabello, & Fernández-Berrocal, Citation2019) and older adults with mild depressive symptoms have not shown significant differences in the surprise recognition condition (Orgeta, Citation2014). It appears that mild or subclinical depressive symptoms do not affect emotion recognition ability in older adults as negatively as they do in early adulthood, at least within recognizing emotionally ambiguous stimuli like expressions of surprise. Overall, surprise recognition showed robust differences between age groups with regards to how intrapersonal emotions predict accuracy.

Lastly, older adults have been shown to have a preserved ability to recognize disgust (Hayes et al., Citation2020; Henry et al., Citation2008). Since older adults show more subjective aversive reactions to negative stimuli than young adults, we theorized that among the older adults who had a higher negative reactivity, strong aversion was experienced, and they were able to maintain the ability to recognize disgust through their subjective sensitivity to negative stimuli such as disgust. Conversely, young adults, who have typically higher physiological reactivity (such as an elevated heart rate and higher skin conductance levels) to negative stimuli than older adults (Fernández-Aguilar et al., Citation2020) may be altered by this physiological phenomenon to correctly identify disgust or they may incorrectly interpret disgust based on their limited past experiences (Young, Minton, & Mikels, Citation2021). Further studies on physiological reactivity and emotion recognition should be conducted.

The current study extracted data from a large and geographically distinct cross-sectional dataset. One limitation was that the study was not longitudinal so we could not evaluate changes over time and causality factors such as the possibility that a heightened sense of reactivity to other’s negative emotions influenced higher reactivity to negative stimuli as opposed to the vice versa effect. Another limitation is that there were only six emotions in the emotion recognition task (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise) of which the majority were negative so it would be difficult to distinguish differences in positive emotions as it seems to be too easy to distinguish happiness with the Ekman Emotion Recognition paradigm. Also, Ekman’s Emotion Recognition task may have lower ecological validity than other tasks that add context to the pictures (Wieck & Kunzmann, Citation2017). Though this experiment did morph the pictures of faces, they were more ambiguous than real life situations due to the lack of context.

Conclusion

The current study showed that intrapersonal ability emotional intelligence factors impact emotion recognition ability differently in early and late adulthood, at least for negative emotions, where older adults and young adults showed opposite trends. Our study investigated how older and young adults’ emotion traits (depression and anxiety) and reactivity interact with their ability to recognize emotions in others. We found that older adults’ subjective negative reactivity was positively associated with emotion recognition accuracy and young adults’ subjective negative reactivity was negatively associated with emotion recognition accuracy. Our data specifically suggested that surprise and disgust recognition may be some of the most impacted emotions. We also found clues into how positive reactivity may play a more important role in the identification of ambiguous emotions such as surprise for young adults than it does for older adults, whereas depression had the opposite effect. These findings could offer further directions for novel interventions to help older adults remain sensitive to negative social situations in order to be able to discern non-verbal negative cues and respond appropriately when these situations cannot be avoided. It also gives further clues into investigating the age-related changes underlying dynamics of emotion reactivity and recognition given that older and young adults were differentially affected.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2023.2254658

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldinger, M., Stopsack, M., Barnow, S., Rambau, S., Spitzer, C., Schnell, K., & Ulrich, I. (2013). The association between depressive symptoms and emotion recognition is moderated by emotion regulation. Psychiatry Research, 205(1), 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.032

- Bar-On, R. (2004). The bar-on emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i): Rationale, description and summary of psychometric properties. In G. Geher (Ed.), Measuring emotional intelligence: common ground and controversy (pp. 115–145). Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers.

- Birmingham, E., Svärd, J., Kanan, C., Fischer, H., & Hsiao, J. H. (2018). Exploring emotional expression recognition in aging adults using the moving window technique. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0205341. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205341

- Blanchard-Fields, F., Jahnke, H. C., & Camp, C. (1995). Age differences in problem-solving style: The role of emotional salience. Psychology and Aging, 10(2), 173–180. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.10.2.173

- Button, K., Lewis, G., Penton-Voak, I., & Munafò, M. (2013). Social anxiety is associated with general but not specific biases in emotion recognition. Psychiatry Research, 210(1), 199–207. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.005

- Cabello, R., Sorrel, M. A., Fernández-Pinto, I., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). Age and gender differences in ability emotional intelligence in adults: A cross-sectional study. Developmental Psychology, 52(9), 1486–1492. doi:10.1037/dev0000191

- Calder, A. J., Keane, J., Manly, T., Sprengelmeyer, R., Scott, S., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Young, A. W. (2003). Facial expression recognition across the adult life span. Neuropsychologia, 41(2), 195–202. doi:10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00149-5

- Campbell, A., Ruffman, T., Murray, J. E., & Glue, P. (2014). Oxytocin improves emotion recognition for older males. Neurobiology of Aging, 35(10), 2246–2248. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.021

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science (New York, NY), 312(5782), 1913–1915. doi:10.1126/science.1127488

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

- Carstensen, L. L., & Mikels, J. A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 117–121. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00348.x

- Carton, J. S., Kessler, E. A., & Pape, C. L. (1999). Nonverbal decoding skills and relationship well-being in adults. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 23(1), 91–100. doi:10.1023/A:1021339410262

- Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration (SAVI): A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. doi:10.1037/a0021232

- Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2008). Unpleasant situations elicit different emotional responses in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 23(3), 495–504. doi:10.1037/a0013284

- Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 383–409. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448

- Charles, S. T., & Luong, G. (2013). Emotional experience across adulthood: The theoretical model of strength and vulnerability integration. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 443–448. doi:10.1177/0963721413497013

- Chen, Y., Peng, Y., & Fang, P. (2016). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between age and subjective well-being. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 83(2), 91–107. doi:10.1177/0091415016648705

- Connolly, H. L., Young, A. W., & Lewis, G. J. (2021). Face perception across the adult lifespan: Evidence for age-related changes independent of general intelligence. Cognition and Emotion, 35(5), 890–901. doi:10.1080/02699931.2021.1901657

- Cortes, D. S., Tornberg, C., Bänziger, T., Elfenbein, H. A., Fischer, H., & Laukka, P. (2021). Effects of aging on emotion recognition from dynamic multimodal expressions and vocalizations. Scientific Reports, 11(1). Article 1 doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82135-1

- Crivelli, L., Calandri, I. L., Helou, B., Corvalán, N., Fiol, M. P. … Correale, J. (2021). Theory of mind, emotion recognition and emotional reactivity factors in early multiple sclerosis: results from a south American cohort. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 0, 1–11. doi:10.1080/23279095.2021.2004542

- Csukly, G., Czobor, P., Simon, L., & Takács, B. (2008). Basic emotions and psychological distress: Association between recognition of facial expressions and symptom checklist-90 subscales. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(2), 177–183. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.09.001

- Deckert, M., Schmoeger, M., Auff, E., & Willinger, U. (2020). Subjective emotional arousal: An explorative study on the role of gender, age, intensity, emotion regulation difficulties, depression and anxiety symptoms, and meta-emotion. Psychological Research, 84(7), 1857–1876. doi:10.1007/s00426-019-01197-z

- Demenescu, L. R., Kortekaas, R., Boer, J. A. D., Aleman, A., & Harrison, B. J. (2010). Impaired attribution of emotion to facial expressions in anxiety and major depression. PLOS ONE, 5(12), e15058. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015058

- de Souza, L. C., Bertoux, M., de Faria, Â. R. V., Corgosinho, L. T. S., Prado, A. C. D. A. … Teixeira, A. L. (2018). The effects of gender, age, schooling, and cultural background on the identification of facial emotions: A transcultural study. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(12), 1861–1870. doi:10.1017/S1041610218000443

- Di Fabio, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2014). Promoting individual resources: The challenge of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 19–23. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.026

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1971). Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), 124–129. doi:10.1037/h0030377

- Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 203–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203

- Fernández-Aguilar, L., Latorre, J. M., Martínez-Rodrigo, A., Moncho-Bogani, J. V., Ros, L. … Fernández-Caballero, A. (2020). Differences between young and older adults in physiological and subjective responses to emotion induction using films. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 14548. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71430-y

- Fox, E., Russo, R., & Georgiou, G. A. (2005). Anxiety modulates the degree of attentive resources required to process emotional faces. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 5(4), 396–404. doi:10.3758/CABN.5.4.396

- Goldin, P. R., McRae, K., Ramel, W., & Gross, J. J. (2008). The neural bases of emotion regulation: reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biological Psychiatry, 63(6), 577–586. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031

- Gould, C. E., Gerolimatos, L. A., Beaudreau, S. A., Mashal, N., & Edelstein, B. A. (2018). Older adults report more sadness and less jealousy than young adults in response to worry induction. Aging & Mental Health, 22(4), 512–518. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1277975

- Grosse Rueschkamp, J. M., Kuppens, P., Riediger, M., Blanke, E. S., & Brose, A. (2020). Higher well-being is related to reduced affective reactivity to positive events in daily life. Emotion (Washington DC), 20(3), 376–390. doi:10.1037/emo0000557

- Hall, J. A., Horgan, T. G., & Murphy, N. A. (2019). Nonverbal communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 271–294. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103145

- Harrison, A., Sullivan, S., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2009). Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(4), 348–356. doi:10.1002/cpp.628

- Harrison, A., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2010). Attentional bias, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation in anorexia: state or trait? Biological Psychiatry, 68(8), 755–761. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.037

- Hayes, G. S., McLennan, S. N., Henry, J. D., Phillips, L. H., Terrett, G. … Labuschagne, I. (2020). Task characteristics influence facial emotion recognition age-effects: A meta-analytic review. Psychology and Aging, 35(2), 295–315. doi:10.1037/pag0000441

- Henry, J. D., Ruffman, T., McDonald, S., O’Leary, M.-A. P., Phillips, L. H., Brodaty, H., & Rendell, P. G. (2008). Recognition of disgust is selectively preserved in alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia, 46(5), 1363–1370. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.012

- Henry, J. D., von Hippel, W., Nangle, M. R., & Waters, M. (2018). Age and the experience of strong self-conscious emotion. Aging & Mental Health, 22(4), 497–502. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1268094

- Hh, F., Ll, C., & Fr, L. (2001). Age-related patterns in social networks among European Americans and African Americans: Implications for socioemotional selectivity across the life span. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 52(3), 185–206. doi:10.2190/1ABL-9BE5-M0X2-LR9V

- Hogeveen, J., Salvi, C., & Grafman, J. (2016). “Emotional intelligence”: Lessons from lesions. Trends in Neurosciences, 39(10), 694–705. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.08.007

- Hudson, N. W., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2016). Getting older, feeling less? A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of developmental patterns in experiential well-being. Psychology and Aging, 31(8), 847–861. doi:10.1037/pag0000138

- Isaacowitz, D. M., Livingstone, K. M., & Castro, V. L. (2017). Aging and emotions: Experience, regulation, and perception. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 79–83. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.013

- Isaacowitz, D. M., Löckenhoff, C. E., Lane, R. D., Wright, R., Sechrest, L., Riedel, R., & Costa, P. T. (2007). Age differences in recognition of emotion in lexical stimuli and facial expressions. Psychology and Aging, 22(1), 147–159. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.147

- Katzorreck, M., & Kunzmann, U. (2018). Greater empathic accuracy and emotional reactivity in old age: The sample case of death and dying. Psychology and Aging, 33(8), 1202–1214. doi:10.1037/pag0000313

- Keil, A., & Freund, A. M. (2009). Changes in the sensitivity to appetitive and aversive arousal across adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 668–680. doi:10.1037/a0016969

- Kessler, H., Roth, J., von Wietersheim, J., Deighton, R. M., & Traue, H. C. (2007). Emotion recognition patterns in patients with panic disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 24(3), 223–226. doi:10.1002/da.20223

- Kliegel, M., Jäger, T., & Phillips, L. H. (2007). Emotional development across adulthood: Differential age-related emotional reactivity and emotion regulation in a negative mood induction procedure. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 64(3), 217–244. doi:10.2190/U48Q-0063-3318-1175

- Kohler, C. G., Turner, T. H., Bilker, W. B., Brensinger, C. M., Siegel, S. J. … Gur, R. C. (2003). Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: Intensity effects and error pattern. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(10), 1768–1774. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768

- Kret, M. E., & De Gelder, B. (2012). A review on sex differences in processing emotional signals. Neuropsychologia, 50(7), 1211–1221. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022

- Kunzmann, U., & Grühn, D. (2005). Age differences in emotional reactivity: The sample case of sadness. Psychology and Aging, 20(1), 47–59. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.47

- Labouvie-Vief, G. (2003). Dynamic integration: Affect, cognition, and the self in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(6), 201–206. doi:10.1046/j.0963-7214.2003.01262.x

- Lange, J., Heerdink, M. W., & van Kleef, G. A. (2022). Reading emotions, reading people: Emotion perception and inferences drawn from perceived emotions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.008

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Cognition and motivation in emotion. American Psychologist, 46(4), 352–367. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.352

- Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 13(5), 481–504. doi:10.1080/026999399379159

- Lima, C. F., Alves, T., Scott, S. K., & Castro, S. L. (2014). In the ear of the beholder: How age shapes emotion processing in nonverbal vocalizations. Emotion, 14(1), 145–160. doi:10.1037/a0034287

- Livingstone, K. M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2021). Age and emotion regulation in daily life: Frequency, strategies, tactics, and effectiveness. Emotion, 21(1), 39–51. doi:10.1037/emo0000672

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267–298. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00016-1

- Mayer, J., Roberts, R., & Barsade, S. (2008). Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 507–536. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3–34). New York, NY, USA: Basic Books.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R., & Sitarenios, G. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion, 3(1), 97–105. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97

- Megreya, A. M., Latzman, R. D., & Hills, P. J. (2020). Individual differences in emotion regulation and face recognition. PLOS ONE, 15(12), e0243209. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243209

- Mill, A., Allik, J., Realo, A., & Valk, R. (2009). Age-related differences in emotion recognition ability: A cross-sectional study. Emotion (Washington DC), 9(5), 619–630. doi:10.1037/a0016562

- Murphy, N. A., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2010). Age effects and gaze patterns in recognising emotional expressions: An in-depth look at gaze measures and covariates. Cognition and Emotion, 24(3), 436–452. doi:10.1080/02699930802664623

- Navarro-Bravo, B., Latorre, J. M., Jiménez, A., Cabello, R., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2019). Ability emotional intelligence in young people and older adults with and without depressive symptoms, considering gender and educational level. PeerJ, 7, e6595. doi:10.7717/peerj.6595

- Olderbak, S., Wilhelm, O., Hildebrandt, A., & Quoidbach, J. (2019). Sex differences in facial emotion perception ability across the lifespan. Cognition & Emotion, 33(3), 579–588. doi:10.1080/02699931.2018.1454403

- Opitz, P. C., Rauch, L. C., Terry, D. P., & Urry, H. L. (2012). Prefrontal mediation of age differences in cognitive reappraisal. Neurobiology of Aging, 33(4), 645–655. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.004

- Orgeta, V. (2014). Emotion recognition ability and mild depressive symptoms in late adulthood. Experimental Aging Research, 40(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/0361073X.2014.857535

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448. doi:10.1002/per.416

- Richter, D., Dietzel, C., & Kunzmann, U. (2011). Age differences in emotion recognition: The task matters. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 66B(1), 48–55. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq068

- Ruffman, T., Henry, J. D., Livingstone, V., & Phillips, L. H. (2008). A meta-analytic review of emotion recognition and aging: Implications for neuropsychological models of aging. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 863–881. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.001

- Ruffman, T., Sullivan, S., & Dittrich, W. (2009). Older adults’ recognition of bodily and auditory expressions of emotion. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 614–622. doi:10.1037/a0016356

- Ruffman, T., Zhang, J., Taumoepeau, M., & Skeaff, S. (2016). Your way to a better theory of mind: A healthy diet relates to better faux pas recognition in older adults. Experimental Aging Research, 42(3), 279–288. doi:10.1080/0361073X.2016.1156974

- Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 276–285. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1058968

- Sasson, N. J., Pinkham, A. E., Richard, J., Hughett, P., Gur, R. E., & Gur, R. C. (2010). Controlling for response biases clarifies sex and age differences in facial affect recognition. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34(4), 207–221. doi:10.1007/s10919-010-0092-z

- Schaan, L., Schulz, A., Nuraydin, S., Bergert, C., Hilger, A., Rach, H., & Hechler, T. (2019). Interoceptive accuracy, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation in preschool children. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 138, 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.02.001

- Schmid Mast, M., & Hall, J. A. (2018). The impact of interpersonal accuracy on behavioral outcomes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(5), 309–314. doi:10.1177/0963721418758437

- Schweizer, S., Grahn, J., Hampshire, A., Mobbs, D., & Dalgleish, T. (2013). Training the emotional brain: Improving affective control through emotional working memory training. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(12), 5301–5311. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2593-12.2013

- Schweizer, S., Stretton, J., Van Belle, J., Price, D., Calder, A. J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). Age-related decline in positive emotional reactivity and emotion regulation in a population-derived cohort. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14(6), 623–631. doi:10.1093/scan/nsz036

- Schweizer, S., Walsh, N. D., Stretton, J., Dunn, V. J., Goodyer, I. M., & Dalgleish, T. (2016). Enhanced emotion regulation capacity and its neural substrates in those exposed to moderate childhood adversity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(2), 272–281. doi:10.1093/scan/nsv109

- Shafto, M. A., Tyler, L. K., Dixon, M., Taylor, J. R., Rowe, J. B., (2014). The cambridge centre for ageing and neuroscience (cam-can) study protocol: A cross-sectional, lifespan, multidisciplinary examination of healthy cognitive ageing. BMC Neurology, 14(1), 204. doi:10.1186/s12883-014-0204-1

- Shiota, M. N., & Levenson, R. W. (2009). Effects of aging on experimentally instructed detached reappraisal, positive reappraisal, and emotional behavior suppression. Psychology and Aging, 24(4), 890–900. doi:10.1037/a0017896

- Spencer, J. M. Y., Sekuler, A. B., Bennett, P. J., Giese, M. A., & Pilz, K. S. (2016). Effects of aging on identifying emotions conveyed by point-light walkers. Psychology and Aging, 31(1), 126–138. doi:10.1037/a0040009

- Sullivan, S., Campbell, A., Hutton, S. B., & Ruffman, T. (2017). What’s good for the goose is not good for the gander: Age and gender differences in scanning emotion faces. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(3), 441–447. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv033

- Sullivan, S., & Ruffman, T. (2004). Emotion recognition deficits in the elderly. The International Journal of Neuroscience, 114(3), 403–432. doi:10.1080/00207450490270901

- Sullivan, S., Ruffman, T., & Hutton, S. B. (2007). Age differences in emotion recognition skills and the visual scanning of emotion faces. The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(1), 53–60. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.1.p53

- Sze, J. A., Goodkind, M. S., Gyurak, A., & Levenson, R. W. (2012). Aging and emotion recognition: Not just a losing matter. Psychology and Aging, 27(4), 940–950. doi:10.1037/a0029367

- Taylor, J. R., Williams, N., Cusack, R., Auer, T., Shafto, M. A. … Henson, R. N. (2017). The Cambridge Centre for Ageing and neuroscience (Cam-CAN) data repository: Structural and functional MRI, MEG, and cognitive data from a cross-sectional adult lifespan sample. NeuroImage, 144, 262–269. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.018

- Tsaousis, I., & Kazi, S. (2013). Factorial invariance and latent mean differences of scores on trait emotional intelligence across gender and age. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(2), 169–173. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.016

- Van Rooy, D. L., Alonso, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Group differences in emotional intelligence scores: Theoretical and practical implications. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(3), 689–700. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.023

- Wenzler, S., Hagen, M., Tarvainen, M. P., Hilke, M., Ghirmai, N. … Oertel-Knöchel, V. (2017). Intensified emotion perception in depression: Differences in physiological arousal and subjective perceptions. Psychiatry Research, 253, 303–310. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.040

- Werner, K. H., Roberts, N. A., Rosen, H. J., Dean, D. L., Kramer, J. H. … Levenson, R. W. (2007). Emotional reactivity and emotion recognition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology, 69(2), 148–155. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000265589.32060.d3

- West, J. T., Horning, S. M., Klebe, K. J., Foster, S. M., Cornwell, R. E. … Davis, H. P. (2012). Age effects on emotion recognition in facial displays: From 20 to 89 years of age. Experimental Aging Research, 38(2), 146–168. doi:10.1080/0361073X.2012.659997

- Wieck, C., & Kunzmann, U. (2017). Age differences in emotion recognition: A question of modality? Psychology and Aging, 32(5), 401–411. doi:10.1037/pag0000178

- Yeung, D. Y., Fung, H. H., & Lang, F. R. (2008). Self-construal moderates age differences in social network characteristics. Psychology and Aging, 23(1), 222–226. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.222

- Young, N. A., Minton, A. R., & Mikels, J. A. (2021). The appraisal approach to aging and emotion: An integrative theoretical framework. Developmental Review, 59. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2021.100947

- Young, A., Perrett, D. I., Calder, A., Sprengelmeyer, R. H., & Ekman, P. (2002). Facial expressions of emotion. Bury St Edmunds, England: Stimuli and Test (FEEST).

- Young, A. W., Rowland, D., Calder, A. J., Etcoff, N. L., Seth, A., & Perrett, D. I. (1997). Facial expression megamix: Tests of dimensional and category accounts of emotion recognition. Cognition, 63(3), 271–313. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(97)00003-6

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x