Abstract

Focusing on museums, this article illustrates how textile crafts can become a source for scholarly inquiry and can enhance more inclusive practices at museums. The empirical data comprises four museum-related projects conducted since 2017 focusing on textile craft and creativity with women in Denmark, particularly women of refugee, migrant, or second-generation migrant background. Through these cases, we unravel the potential of textile crafts as a medium and encounter for engagement in museums within a societal context, both as a professional outlook, an education, a cultural heritage, an object of research, and a pastime for pleasure and socializing. The common thread—our academic quest—is how, when, and why textile craft is entwined with female empowerment, and how textile craft, as a shared community action, can empower and represent an opportunity for museums to reach new audiences as well as use the museum space in new ways.

Introduction

this article investigates how textile craft skills can form gateways for more inclusive practices at museums. It is structured thematically around four case studies occurring between 2017 to 2024, which involved approximately 400 women from refugee and immigrant communities in Denmark, primarily from North Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern European countries that have relocated to Denmark since the mid-1960s. These groups primarily consist of women affected by the war in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the civil war in Syria that began in 2011, as well as the Russian war on Ukraine that started in 2022, which led to migration and displacement in Europe from these countries.

The four case studies are comprised of museum-centered open workshops focused on cross-cultural textile craft which served as way for museums to engage new visitors and narratives; the co-creation of textile art with textile crafters and artists that invited visitors to engage with experiences and stories about memories of home and ideas of family and happiness; a commercial partnership between museum gift shops and craft associations for refugee and migrant women; and a sequence of cultural heritage studies of textile terminology which helped to “widen the landscape” of historical and cultural interconnections across time and place and thereby inform the textile narratives in museums. The concluding remarks and perspectives provide insights into ways in which the projects have affected individual lives and stimulated longer-lasting interaction and collaborations between researchers, migrant and refugee communities, and museums in Denmark. We aim to inspire those engaged in museum work, cultural institutions, craft workshops, and social integration to experiment with textile crafts as new ways to engage in intercultural dialogues and demonstrate a living cultural heritage.

The first research project, occurring between 2017 to 2019, was CULINN (Cultural Citizenship and Innovation), led by The National Museum of Denmark and supported by the Innovation Fund Denmark, which invited people with refugee status into the museum space as an introduction to the history and society of their new host country. The goal was to facilitate networking meetings and use the museum as a community-building and cultural history site. Textile craft was used as the medium to engage people with refugee status and local people in Denmark in a dialogue within the museum.Footnote1 The second project, also from 2017 to 2019, was THREAD (Textile Hub for Refugees’ Empowerment, Employment and Entrepreneurship Advancement in Denmark). That project was supported by the Innovation Fund Denmark and led by the Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen in collaboration with Design School Kolding, Aalborg University, and University College Copenhagen.Footnote2 That project’s aim was to investigate opportunities for entrepreneurship and empowerment of refugee and migrant women through textile skills. The project involved many textile workshops supported by municipalities around Copenhagen and Kolding, as well as a close collaboration with The National Museum of Denmark.

The third project, The FABRIC of My Life, was conducted from 2019 to 2022 and funded by the European funding scheme Creative Europe. It was led by the Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen in collaboration with Design School Kolding, Deutsches Textilmuseum Krefeld (DE) and ARTEX, Hellenic Centre for Research and Conservation of Archeological Textiles (GR).Footnote3 FABRIC expanded the experiences of textile craft communities in museums by hosting a series of workshops in which migrant and refugee communities interacted with researchers through co-creating textile art pieces for museums and exhibition spaces in the partner countries of Denmark, Greece, and Germany. Finally, the fourth project, Tekstil i Tingbjerg (Textile in Tingbjerg), which started in 2020, was funded by the Danish Ministry of Culture and led by Tingbjerg Culture Centre in collaboration with knowledge partners Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen Business School, Greve Museum, and Tingbjerg Church. In this project, Danish and migrant women in the suburban municipality of Tingbjerg co-created textile art pieces with artists for public display.

There were similar initiatives in Europe involving migrants and refugees in cultural institutions before 2017.Footnote4 However, we would like to dedicate this article to the specific situation in Denmark in the years between 2017 and 2024, during which the projects were conducted, thus shedding light on circumstances shaping this time and place.

Danes’ participation in cultural institutional activities is among the highest in Europe. According to the national central authority on Danish statistics, the country’s relatively small population of nearly 6 million inhabitants has access to 384 museums with an entrance count of more than 15 million persons.Footnote5 Furthermore, 85.3 percent of Danes reported in 2015 that they took part in at least one cultural activity during the past year (cinema, live performance, or visiting a cultural site such as museums, historical monuments, art galleries, or archaeological sites).Footnote6

Approximately half the Danish population visits museums regularly.Footnote7 The other half rarely or never visit museums; even though they consider museums important institutions, they find that museums do not contain relevant information for them. Furthermore, they anticipate the museum experience to be foreign, awkward, and alienating. People with migrant or refugee status make up the majority of those who rarely or never visit museums.Footnote8 However, this article demonstrates how women from these communities, through research and outreach projects, have engaged in various ways with museums and exhibition spaces. The examples include spaces for creative co-creation as sources of inspiration and reflection, as public spaces, and as sites for commercial opportunity. We aim to demonstrate how it has been made possible to facilitate alternative access points to museums, and how the opening of new and inclusive practices requires rethinking, rephrasing, and relabeling, especially of conventional museum communication methods.

All projects were conducted in collaboration between Danish museums, textile-related craft communities, and research institutions. Participating museums were located on Sealand and in the city of Kolding; primarily, The National Museum of Denmark, but also The Workers’ Museum, FLUGT—The Refugee Museum, The Migration Museum, Design Museum Danmark, Trapholt Museum, Greve Museum, Christiansborg Palace Museum, and KØS Museum of Art in Public Spaces. One main partner of all four projects was the textile craft community Igne:Oya (Turkish for textile craft) located in Tingbjerg and Husum, which are suburbs of greater Copenhagen. The community welcomes forty to fifty women every week for shared textile craft activities, design fairs, excursions, and an annual fashion show. The textile workshops are hosted by designer and social worker Henriette Rolf Larsen. Other textile craft communities involved were the knitting circle at Tingbjerg Church, the SheWorks socio-economic enterprise in Kolding, the Fenuun workshop at Design School Kolding, and finally, embroiderers in Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, and France.

Museums as Potential Sites for Shared Languages

All projects and inquiries were driven by our interest in understanding how textile threads—whether they are woven, knitted, crocheted, or embroidered—can combine cultural narratives (historical and present), everyday dress practices, languages, and a plethora of situated contexts across borders and time in a museum. A driving force for this is a desire to engage with ongoing debates about fashion decolonization as put forward by the editors of the 2020 special issue of Fashion Theory: “If there are three pressing issues in both the academic study and the public debate around fashion at the present moment, they are sustainability, inequality, and cultural appropriation.”Footnote9 The latter is our focus in the projects included in this article. We have worked with issues of cultural appropriation along the lines of 1) the delicate power balance between researchers and the several hundred migrant and immigrant women involved in the various activities; 2) an openness to embrace textile cultural heritage as an evolving and ongoing exchange rather than a fixed cultural phenomenon; and 3) a sensitivity towards the mutual learning space that emerges between all involved parties, anchored in textile skills and practices that function as “dialogue tools” at various levels.

Museums have traditionally been perceived as authorities. Museum Studies scholar Eilean Hooper-Greenhill argues that museums historically functioned as disciplining institutions. They not only presented objects but also controlled and defined what constituted legitimate knowledge and culture. This disciplinary role positioned museums as authorities in society.Footnote10 Museums can embody political and/or national ideals of the majority culture and therefore, must regularly engage in critical reflection of their choices and values as well as how visitors may perceive them. This change has been described by Hooper-Greenhill and conceptualized as the “post-museum.” The post-museum represents a significant shift in the understanding of museums’ roles and functions. It emphasizes interaction and the co-creation of experiences and knowledge.Footnote11 The recent dialogue-based approach that many museums have chosen is supported by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and aims to engage visitors by involving them in the co-creation and co-interpretation of history. It also aims to give visitors voice and invites them to include their personal history, while linking it to a wider international debate about the future role of museums. According to ICOM Strategic Plan:

Museums have discovered ways to add significant value to their traditional roles through creative programs, which realize the potential of their knowledge and skill to reach out to alienated and vulnerable groups in their communities, to promote intercultural dialogue, to provide experiential learning for those who have missed out on conventional education or to create programs that tap into the benefits of culture.Footnote12

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.Footnote13

Museums function as “contact zones” that bring people together across different ethnic and other socio-economic affiliations. The term was coined by Mary Louise Pratt, Professor Emerita of Spanish and Portuguese at New York University, who uses the concept for colonial encounters. They are defined as social spaces where cultures meet and sometimes clash, often in the contexts of asymmetrical relations of power such as colonialism and slavery, but also their aftermaths as they lived out in many parts of the world today.Footnote15 This was further developed by the cultural historian James Clifford who applied it to the cultural sector and coined the concept of “museums as contact zones.” Clifford uses this phrase to assess the role of the museum concerning other cultures.Footnote16 We see it as an important role of museums to create shared activities within these contact zones.

Although the concept of contact zones offers rich possibilities for dialogue and understanding, some scholars have argued for the need to critically examine power dynamics, representation, and collaboration within these spaces.Footnote17 They criticize the concept for pitting groups of people against one another or producing an “us vs. them,” majority vs. minority dynamic. We have instead attempted to reconceptualize contact zones as “third spaces.”Footnote18 In sociology, third spaces are not defined as homes and workspaces, but as locations where people meet for different purposes and activities producing coherence and a common sense of shared values. Furthermore, we made operational the idea that fashion and textile skills as a shared third language can bridge intercultural encounters, craft techniques and materials, as well as etymological wordings, ideas of taste, beauty, and styling.Footnote19

Everyday Creativity as a Frame for Cultural Encounters

It is in this similar mesh of fashion cultures, textile crafts, and techniques that this article and these projects are rooted. Thus, our inquiry draws on recent research of dress practices that favor the mundane and everyday life lived through garments and various textile objects, as well as the skills for creating a functional, appropriate, and prized wardrobe through practices of acquiring, making, mending, repairing, and redesigning. This approach is informed by the wardrobe method research and its emphasis on the majority of people and their fashion cultures, ages, ethnicities, bodies, and gender types they represent, which have been largely ignored in much traditional fashion research as well as in the diverse range of fashion mediation and representation.Footnote20 Hence, one of the key concepts and methods at the heart of our work is “everyday creativity.”Footnote21 Studies have shown that various therapeutic effects and wellness are associated with craftmakingFootnote22 and reinforce a sense of coherence and coping.Footnote23 In social psychology, everyday creativity is based on the understanding that humans, whether at home or work, “adapt and innovate, improvise flexibly.”Footnote24 Everyday creativity is thus embedded in everyday actions and yields meaning to life. As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz writes, “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun,” using an appropriate textile-technological metaphor.Footnote25 Leaving one’s home and country and most of one’s possessions behind, including status symbols, settling in a new country, and learning a new language are challenging life conditions. Yet, the focus on everyday creativity uncovers and highlights the resources of the participant women.

The knowledge, skills, and experience of the participating women formed the basis of the collaboration. Many of these women represent a majority in unemployment statistics and often suffer multiple health issues.Footnote26 The public rhetoric and media representations often see these women as a uniform group who pose a challenge to the welfare state as well as to public budgets. Immigrant women are in many ways muted as their voices are seldom heard and they are nearly absent in political decision-making bodies. However, these women are, of course, not a homogenous group but differ in national and ethnic origin, educational background, personality, lifestyle, etc. Both highly educated women and those with no formal education degrees participated in the projects. Regardless of their formal educational training and socio-economic background, most brought with them embodied knowledge, skills, and rich life stories.

This concrete and hands-on approach to the projects uncovered shared experiences of what took place when we explored everyday creativity together.Footnote27 Several studies have demonstrated the joy of being creative through textile craft and its healing and calming effect.Footnote28 Moreover, textile craft activities can enhance a sense of belonging and multicultural empowerment.Footnote29 Crafting together became a way of social engagement and extending networks, and this is particularly important in migrant communities who may miss the close contact with their extended family. As stated by Alma Sharif, one of the participants:

I saw some of the women exchange phone numbers because they realized they had something in common. It's a cool thing that they get to know new people and someone who doesn't live next door. But they have a common interest in textile craft. I often hear from people in the area that they have no family. They have no family members and have only their husbands and children. They are very lonely. It is good if we can build a network where the women can make use of each other.Footnote30

At the beginning, when we started the workshop [in 2018], there was a group of women sitting around the table with gray jackets and big scarves. I was wondering if there was someone behind those jackets. They were so quiet, said nothing, and were very humble. Then we slowly started asking them what they wanted. Fashion show! Then we put up a huge fashion show that attracted a lot of people. Now the women like to make decisions. They make demands and have ideas. They have become much stronger in the four years.Footnote31

All the hosted textile craft activities were open to anyone who expressed interest. We observed that the craft activities attracted diverse groups of people from different cultural backgrounds and social statuses, including people in vulnerable situations. Situations that might be described as chronic illness, those on sick leave, or those individuals who might suffer from psychological or psychiatric conditions and ailments. Thus, the objects themselves and textile-related skills associated with making became the tangible tools for creating, sharing, and investigating contact zones as well as a shared language through which people met and exchanged skills, knowledge, and insights.Footnote32

Methodological Reflections

Methodological implications of bias, power balance, inclusion, and exchange are integral to all research projects involving people, and certainly also between ourselves as academics and the women participants in question here. From the outset, we struggled with terminology and labels. The research funding schemes that were available to us, as well as the political focus, targeted projects geared towards vulnerable refugees who had recently arrived in Denmark, including people with a low level of integration and education. On top of that, many of the refugees were suffering from one or more chronic health conditions and thus experiencing challenges entering the Danish labor market. The textile craft activities attracted primarily refugee women; yet, they also attracted women of immigrant status who had been residents in Denmark for more than ten years, as well as second-generation migrants. Likewise, they attracted local Danes, some of whom were from strong socio-economic backgrounds, as well as Danes who were economically and/or socially vulnerable. During the craft activities, we resorted to tekstildamerne, or “the textile ladies,” as a common designation for us all: the crafting communities and the textile scholars.

The challenges of nomenclature arose again when describing activities or in advertising events in museums. Recently, the more inclusive expression “new citizen” has gained ground in Denmark, but this term is also criticized for its reference to citizenship which is notoriously difficult to obtain in Denmark.Footnote33 We have hence adopted the designation “women participants” for this article. Our research teams were also made up exclusively of women, which in turn possibly influenced and shaped the recruitment and subsequent collaborations so that primarily women participated in these activities.

We hosted workshops in museums, universities, community centers, design businesses, and design schools, with the participants continuing their craft practice at home. This increased during the pandemic. However, distance and mobility were constant barriers to shared craft activities or to undertaking excursions together. While universities and museums are often located in city centers, most migrant and refugee women live in suburban or rural areas. Suburban communities in Denmark are conceived architecturally in urban planning as entire communities (church, library, schools, municipality). This is seen in Tingbjerg, but can be found in many Danish social housing areas.Footnote34 Consequently, people living in suburban communities are centralized in their economic and social life, rarely needing to leave the area or enter the city center. Distances may be only 5 km to 25 km yet, in our experience, many remain in their communities as many are not always self-sufficiently mobile, which is further complicated by poor public transportation in rural areas. Mobility and transportation were, therefore, major obstacles in all the collaborative activities. It became important either to facilitate transportation to universities and museums or to relocate academic work outside universities and transport students and scholars to where the participants live.

The research teams collaborated with “cultural brokers,” “facilitators,” and “gatekeepers” (see below) who worked as intermediaries and interpreters between the researchers and the participants. Cultural brokers are transition agents who claim double or triple identities, having Danish and migrant or refugee backgrounds, or through marriage.Footnote35 They are trusted by their peers and move more freely between the local and immigrant communities. In Tingbjerg, social worker Güler Yagci is such a cultural broker. She grew up in Türkiye in a Kurdish family but has lived in Denmark for more than thirty years. One of the participant women, Ayse Sagar, commented about Yagci’s role as a cultural broker between the Tingbjerg community and the Igne:Oya workshop:

There’s something about this place—it’s cozy, it’s fun. The people who come talk with each other. They crochet, they knit, they sew. A lot of different things happen here. It’s really cozy. It was Güler who asked me if I wanted to come.Footnote36

I have a mentor role and I am a bridge builder. I can be their extended arm. So from both sides actually—between the women and Danish society. I translate both from Danish to women’s everyday Danish and I am a cultural translator.Footnote37

Facilitators served as workshop hosts, leaders of associations, or ethnic representatives of a minority group. They are not necessarily bicultural, but instead have a deep knowledge and sometimes exclusive access to certain groups of migrant people, whom they often also represent. Some exercise gatekeeping over inclusion and exclusion within the groups as well as monitor information. We were very much aware that gatekeepers may unintentionally perpetuate power imbalances or create barriers for minority groups within the project context, as has been pointed out in a study about cross-cultural differences and implications for project management.Footnote38

We experienced that gatekeeping facilitators, as we prefer to refer to them, possess dual functions: they may close gates to protect the groups from outside threats, and they may open gates and facilitate exchange and safe exit. A crucial facilitator and gatekeeper for these projects was Danish designer and social worker Henriette Rolf Larsen from the craft group Igne:Oya who initiated new activities and encouraged the workshop participants to take part in an array of research events. She was the entry contact to the group, represented the group’s interests in meetings with the municipality, and facilitated the participants becoming empowered to make their own decisions on the activities in the workshop.

Another facilitator and gatekeeper that grew out of the THREAD project was Danish designer and social entrepreneur Solveig Søndergaard, the initiator of the enterprise SheWorks, in which she employed more than twenty women from the weekly Fenuun workshop, a THREAD activity at Design School Kolding.Footnote39 Some academics took on the roles of cultural brokers and gatekeepers when refugee women became interns at the University of Copenhagen as part of their integration program and became affiliated with the research projects for three months to two years.

Another kind of facilitator, the “institution brokers,” are people familiar with museums and what they can offer, yet with close affiliations outside the museum. This institution broker category has in recent years been fulfilled by outreach and dissemination staff in museums and experts in community-driven engagements. Alternatively, institution brokers can be museum staff with close connections to certain communities. In the projects discussed here, two of the authors, Susanne Lervad and Gitte Engholm, became institution brokers due to their multiple engagement in community work, museums, and academic institutions.

With cultural brokers, institution brokers, and important gatekeepers acting as valued facilitators for the various activities, a common experience emerged across all the projects. This included sitting together in late afternoons and early evenings for talks, technique demonstrations, museum events, or other activities and doing textile crafts together. All would bring some type of handicraft project and exchange techniques and photos of completed works (typically on cell phones). There were “touch, show, make, exchange” activities that typically went beyond the spoken word and thereby helped overcoming language barriers. Furthermore, these activities helped fill important gaps in current research about textile history through exact explorations of concepts and terms.Footnote40

The following sections describe our case studies and outline how migrant and refugee women collaborated with academics in museums around textile crafts. Textile crafts served as the third space and acted as the shared language. Each gathering was designed to draw on the skills and knowledge of the participants to creatively produce new ideas and new ways to interact with museum and exhibition spaces.

Museum-based Open Workshops with Cross-cultural Textile Craft Activities

The National Museum of Denmark experimented with formats for overcoming barriers that may prevent migrants and refugees’ visitation, as well as rethinking museum practices to make museum exhibits and events relevant to diverse populations who do not typically visit the museum, or perhaps do not have positive expectations for a museum visit.Footnote41 These formats are often called “audience development,” although they are aimed at amending museum practices, not the audiences. Hence, audience development is a task taken on by museums to reflect multivocal displays of diverse narratives with new audiences so they can find themselves represented. This requires a new museological reflection on the choices made in exhibitions, with regard to representation and traditions, which in turn provide diverse opportunities for learning.Footnote42

We believe that museums can become imaginative cultural spaces and important third spaces where creativity can be nurtured and embedded throughout. Furthermore, we believe museums can offer safe spaces for communication and interaction and for sharing memories with new audiences. Therefore, a series of workshops with opportunities for community knitting, weaving, embroidery, crocheting, and other textile activities was launched, welcoming new audiences to use the museum space for expanding social networks with other women sharing in handicrafts. While jointly working with these techniques, participants also had room to communicate with each other about techniques and results, exchanging views on ethnic identity, regional techniques, and the symbolic meaning of certain garments, textiles, and ornaments. The handicraft workshop thus operates as a Tangible Dialogue Tool (TDT), which is a mediator that enhances dialogue between the participants who may not be native Danish speakers.Footnote43 Often dissemination in museums is confined to verbal communication as guests are invited to take part in debates, listen to lectures, or take a guided tour which puts the audience in the position of passive listeners. At handicraft workshops, however, every participant becomes an expert contributing to the common sum of knowledge. Women—both local Danes and those with migrant or refugee backgrounds—were invited to participate as experts and guest lecturers teaching their skills to other participants ().

Figure 1 Sunday Pursuits textile craft workshop at The Workers' Museum, Copenhagen. Women from Tingbjerg and women from other parts of Copenhagen get together. Two groups of women who seldom meet, but when doing so, find great pleasure in exchanging knowledge about handicraft techniques. October 2019. Photo: Linda Nørgaard Andersen.

To engage participants with migrant or refugee backgrounds the Igne:Oya craft association played a crucial role in facilitation. Typically, museum marketing uses SoMe media and/or commercial advertisements, but this approach fails if the aim is to attract a new audience that rarely considers visiting a museum. Igne:Oya workshop leader Rolf Larsen facilitated the meetings as she is trusted in her community. The events were published as “Sunday Pursuits” and as special free museum events. Museum visitors signed up ahead of time, and seats were reserved quickly. In each event, a museum curator would share textile items from the collection while a participant woman, invited as a speaker would also present textile items of her choice along with a personal story or a presentation of cultural traditions.

The opportunity to view museum-housed textiles and clothing reinforced the medium as an age-old, universal, shared human experience. For example, in a workshop focused on embroidery, participants brought their example of embroidery work or tried to execute a piece of embroidery prepared in advance by the museum staff ( and ). The prepared embroidery () was part of a reconstruction of a Viking Age shirt. Historically, museums have tended to collect an aesthetic that appeals to a certain segment of the population—often characterized by high education and regular consumption of culture—such as the museum’s employees (typically ethnic Danes). However, taste and cultural consumption are formed by class affiliation, family, cultural background, and education. Hence, it was important to select motifs and patterns together with the workshop participants. In the museum’s temporary Viking exhibition, participants saw the full reconstruction of the shirt that represents Danish prehistory as well as cultural encounters and trade contacts between the Viking, Persian, and Arab merchants who traveled along the Silk Roads.

Figure 2 Sunday Pursuits textile craft event, on October 24, 2021, with the theme of embroidery, The National Museum of Denmark. Rubina Shaheen (left) and Samera Jamill enjoyed working with the old motifs from the Viking Age cloak found in a grave at Mammen, Denmark. On the same day, the group visited the exhibition The Raid, telling the story of the Vikings who raided locations as far away as the Mediterranean Sea and Central Asia. Photo: Gitte Engholm.

Figure 3 Detail of Viking Age motif as sample embroidery, used in a Sunday Pursuits textile craft event, on October 24, 2021, with the theme of embroidery, The National Museum of Denmark. Embroiderer Katrine Gudmundson had prepared patterns and yarns in advance, inspired by the museum collections. Photo: Gitte Engholm.

In other Sunday Pursuits sessions, the theme was “crochet,” with a participant demonstrating Turkish crochet techniques and bridal trousseau practices, and Danish Christmas and Easter decoration in crochet techniques, either self-made or from the museum collections (, , and ). The conversations around the crocheted handicraft developed into a lively discussion about mythological creatures across cultures.

Figure 4 Sunday Pursuit textile craft event, September 20, 2020, with demonstration of crochet techniques, The National Museum of Denmark. Photo: Sofie Clausager Dar.

Figure 5 Workshop on crochet at The National Museum of Denmark. Mutual admiration for each other's masterpieces. September 20, 2020. Photo: Henriette Rolf Larsen.

Figure 6 Sunday Pursuits at The National Museum of Denmark. Crochet skills are passed over to the next generation. December 2019. Photo: Henriette Rolf Larsen.

We learned from the Sunday Pursuits events that museum guides tend to primarily use verbal engagement augmented by many historical details about an object. This narrative occurs at the expense of alternative and perhaps richer narratives demonstrated through techniques and/or insights proposed by the audience through observation. Using handicrafts as a starting point created an opportunity to share cultural history, as well as to include participants’ technical, historical, and personal knowledge and memories. In this way, the museum experience becomes less abstract and more personal and relevant for participants who do not normally visit museums. Thus, the museum can position itself as less of an authority conveying its knowledge to the ignorant visitor, and instead as a space for more equitable encounters between people who might exchange cultural and historical knowledge.

Textile craft, moreover, encompasses tactile and embodied knowledge that is familiar to an audience not accustomed to museum visits. In a museum setting, encounters between people of all origins can take place on a more equal level than outside in society. As the craft experience is non-verbal, it can be communicated with movements, not words, which can give the sense of equality between participants from diverse backgrounds and skill levels. This was exemplified in the Sunday Pursuits when all participants were encouraged to bring self-made handicrafts pieces to exchange knowledge on technique and show their skills ().

Figure 7 Sunday Pursuits at The National Museum of Denmark. Participants display home-made handicrafts. September 20, 2020. Photo: Henriette Rolf Larsen.

The challenge for museums is that the institutions can be feared and perceived as foreign, thus producing a perceived barrier to encounters. In the context of this study, we found that some women participants invited to present their textile skills and traditions in the museum were afraid to enter the museum space. Other participants experienced shock and humiliation, having broken an invisible and implied rule. Unknowingly, they took a rest and sat on the steps of a staircase. In response, a museum custodian told them to leave. Hence, museums need to rethink their invitations, their style of communication as well as their barriers to access, if audiences unfamiliar with the museums’ particular cultural context are to feel welcome.

If these barriers can be dismantled, however, the official status of the institution can empower visitors and offer them a feeling of legitimacy and a sense of belonging. It is important for the museum space to offer friendly and familiar faces which can be achieved by having a host who invites participants in and helps facilitate. This is what ethnographer Katherine Robinson terms a “trusted public space that is semi-curated.”Footnote44 A trusted space assures that one does not violate unknown or unwritten norms for correct museum behavior. This is a challenge that museums are aware of but have difficulty dealing with. We tried to mitigate the insecurity and uncomfortable situations by including cultural brokers, by inviting the Igne:Oye crafters as a group, by meeting them by the museum entrance, and by assisting with transportation. These obstacles should not be underestimated by museums.

The presentations in the craft workshops generated questions and initiated discussions on what life is like in Denmark, Türkiye, Pakistan, Somalia, and other places. The participants compared experiences, displayed their knowledge and skills, and became equitable partners in discussion. A common thread in the discussion was to search for shared cultural traditions as well as similar textile techniques: “We have this tradition; do you have the same?” The participants began to show and teach one another techniques. Additionally, we observed intergenerational teaching and knowledge sharing across nationalities and ethnic groupings ().

Co-creation of Textile Art with Textile Crafters and Artists

In recent years, textile craft has found its way back to museums and has become a renewed way to engage audiences.Footnote45 In Denmark, the effect has been most visible in the context of art and design museums. The degree of creative and artistic freedom varies, from totally free knitting sessions for regular visitors, semi-structured educational activities for children and adults, to artist-led co-creation facilitated with precise guidelines. An example of the latter two was the exhibition project Stitches Beyond Borders by textile artist Iben Høj at Trapholt Museum celebrating the centennial of the re-established border between Denmark and Germany in 1920. People with embroidery skills contributed small color-coordinated embroideries, which were then assembled into an art installation; embroidery manuals and tutorials were offered for those not familiar with the craft.Footnote46

In the Fabric of My Life project, two textile artists, as well as refugee and migrant women, created collaborative exhibition pieces.Footnote47 Iranian-French artist Rezvan Farsijani handed out cotton sheets to refugee women in Paris, in the suburbs of Beirut in Lebanon, in a Palestinian refugee camp at Balga in Jordan, and to Afghan refugees in two places in Iran: in Kashan near Tehran and in the Khorasan region near the border to Afghanistan. Farsijani invited them to embroider images of love and joyful memories. The fabrics were assembled into what they all yearn for: a home, or a house, adorned from floor to ceiling with roses, hearts, children’s faces, and statements such as “Allah is great” (). The co-created artwork, Promise of Dawn, represents a house stitched together of embroidered panels. Farsijani was the conceptualizing artist who assembled, cut, and remodeled the panels.

Figure 8 Textile artist Rezvan Farsijani assembles her textile art piece in Athens, September 2021. It consisted of embroidered panels made by her creative embroidery communities of refugee women in Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, and France. Photo: Marie-Louise Nosch.

Textile designer Solveig Søndergaard asked migrant and refugee women in the Danish cities of Kolding and Tingbjerg for a photograph of happy times in their lives. The photographs were enlarged and printed on pieces of fabric, and the women embroidered and decorated the black and white photo prints with silk threads, sequins, ribbons, and beads while talking about the happy moments (). In these artworks, the reverse side of the fabric was part of the work, where each loose thread and knot told a different story from the neat, composed front side. The results are highly individual and personal, and each piece is signed by the woman who created it and whose family it represents, as can be seen in . Yet the artworks were partly made in a shared community space where it was possible to exchange ideas and inspire each other.

Figure 9 Solveig Søndergaard demonstrates an art piece signed by Sheema. Embroidery on printed fabric. July 2021. Solveig Søndergaard and refugee and migrant women in Kolding and Tingbjerg made use of their own childhood memories. From the artistic textile work project Stitched Stories. Photo: Marie-Louise Nosch.

Embroidering together gave rise to conversations about memories of childhood and textile crafts, and from where their textile skills came. Khawla, a resident in Tingbjerg who was born in Tunisia, recalled how as a little girl she made dresses for her doll from scraps of fabric. She would sit under her mother’s old sewing machine, under her mother’s legs, and make clothes for her doll while her mother was sewing clothes.Footnote48 Nehla Alkhafaji, a resident in Tingbjerg who was born in Iraq, told how she learned to sew and knit from her mother. She said: “My mother was very skilled at embroidering, sewing and knitting. She was also good at school.”Footnote49 The conversations often evolved around women’s craft skills and the passing of skills from one generation to the next.

Both the co-creation process and private stitched stories raised the question of authorship and whom to name. We presented the art pieces differently along the projects: in Athens in 2021, the two textile art installations were exhibited without the names of the participating women, and in Kolding in 2022 with a catalogue including their names.Footnote50

The experiences of co-creation with textile artists continue beyond the museum space. The Culture Centre of Tingbjerg and the Tingbjerg Church collaborated to invite an annual textile artist in residence who creates art based on the inputs and skills of the participating women. Artist Bettina Andersen conducted the textile co-creating project from August 2022 to September 2023. Igne:Oya’s craft women participated as experts in crochet and embroidery (), where they partnered with the knitting circles of the local church. The co-created textile art pieces were displayed in the local institutions in Tingbjerg.

Figure 10 Fardos Mosa and Naghem Jasim (right) in the workshop creating pennants, Tingbjerg 2022. Photo: Bettina Andersen.

Andersen’s goal as house artist was to bridge the gap between craft and art and to let as many people from Tingbjerg as possible participate in the creation of three large collective textile works. Adults and schoolchildren sewed pennants with the idea that the pennants could be used in Tingbjerg for festive occasions, regardless of whether it is a communal meal in the cultural center, a Christmas event in the church, or a party at the local school. Some created festive neutral pennants, others made pennants with more personal stories embroidered on them. The pennant installation now resides in its permanent place in the Tingbjerg Culture Centre. In addition, two large patchworks were created, one for Tingbjerg School and one for Tingbjerg Church, each consisting of squares of 20 × 20 cm which could be embellished personally with embroidery. The patchwork for the school was embroidered by the local schoolchildren at Tingbjerg School. Approximately 250 to 350 people participated in the project.Footnote51

Commercial Textile Craft Products for Sale in Museums

Another link between museums and textile craft communities is the museum gift shop. The opportunity to earn money as well as to showcase skills appealed to some workshop participants and furthermore reframed the museum as a place of acceptance and prospect. The workshop Igne:Oya with its own design label Igne:Oya—made in Tingbjerg sells textile items/products in the museum shop of FLUGT—The Refugee Museum. The FLUGT museum is dedicated to sharing refugee stories. In addition to the historical records of German refugees in the aftermath of World War II, FLUGT tells the story of the last hundred years of refugees who have immigrated to Denmark. The museum aims to give refugees a voice and provide visitors with a view of the people hidden behind the headlines and statistics in the media. It asks questions such as “how does flight impact a person?” “What is ‘home’?” Based on stories of refugees from countries such as Germany, Hungary, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Syria, the museum turns statistics into stories of real people to convey universal experiences, thoughts, and emotions associated with the plight of being a human on the run.

A collaboration developed between Igne:Oya and the refugee museum, in which batches of crafted textile items were delivered for sale in the gift shop. This included finger dolls representing the Danish author Karen Blixen, Queen Elisabeth II, the Queen’s guards, and sorrow dolls (montanka dolls) from Ukraine. Products such as clutches and bags decorated with embroidery made from recycled fabrics, knitted cloth for kitchen use, crocheted accessories, and Christmas decorations are examples of popular products sold in the museum gift shop (). The museum contextualized and personalized the products with QR codes and labels adhering to the products. For some, portraits or films of the craftswoman who made the items are accessible through the QR codes. From the museum’s perspective, this link represents an opportunity to reach out to new audiences and visitors and to enhance diversity in aesthetics, crafts, and narratives.

Figure 11 Display of textile handcrafted products made by the Igne:Oya and sold in FLUGT—The Refugee Museum’s gift shop. Designer Käte Kofoed Espersen who is in charge of the merchandise sold in the museum shop comes to Tingbjerg to buy handicraft products for the museum gift shop. March 20, 2022. Photo: Anne Sørensen.

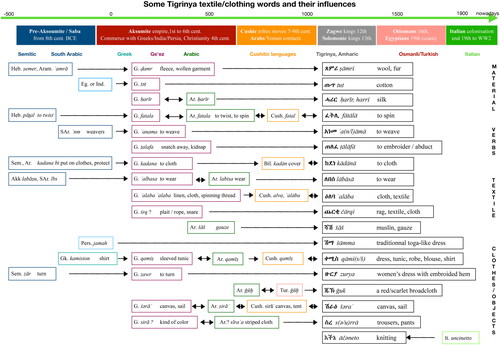

Cultural Heritage in Tigrinya Textile Terminology

In this final project, we outline how textile terminology scholars benefitted from collaboration with women participants, how they used museum exhibitions of textiles to strengthen the collaboration, and how this collaboration contributed to empowerment and academic scholarship. In 2017, two women from Eritrea with refugee status, Alem Haile and Mlete Beyene, had internships at the Centre for Textile Research for sixteen weeks. During the internship, the center’s linguist research team and the Eritrean interns and their families visited museums with textile arts and craft. They went to the Design Museum Danmark and KØS Museum of Art in Public Spaces, where they saw the historical tapestries produced at the Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris depicting the history of Denmark on display at Christiansborg Palace Museum.Footnote52 This was the beginning of a conversation and subsequent collaboration expanding into textile terminology research.

As a shared terminology tool, the Centre for Textile Research hosts the website Traditional Textile Craft with a section on multilingual textile terminology and different concepts/terms for materials and techniques such as spinning, weaving, tools (pins and shuttles), and other equipment.Footnote53 The terminology table had unfinished columns for some Arabic terms. However, it became apparent that the Eritrean women’s own language Tigrinya was an equally valuable resource. The linguists and the Eritrean women undertook weekly work sessions (). The first sessions formed a discussion on tools and materials, such as wool and silk, by exploring the material together. They documented material use, spinning, and yarn vocabulary in Tigrinya and included lessons in knitting, which the two participants did not know how to do.

Figure 12 Textile terminology session in the Centre for Textile Research, University of Copenhagen. The session participants discussed textile-related vocabulary in Arabic, Tigrinya, English, and French, aided by images and dictionaries. Photo: Jane Malcolm-Davies.

Terminologist Susanne Lervad has long voiced in her research the significant absence of adequate multilingual glossaries and databases for textile words, as these belong to a complex linguistic and semantic field. In addition, dictionaries are mostly compiled by linguists who never had first-hand experience with textiles, crafts, or clothing terminology. At the dialect level, this blind spot proves even greater. Words for clothes, textiles, needlework, techniques, knitting, and textile tools are missing in dictionaries.Footnote54 Thus, she and her colleague, linguist Christian Gaubert, devised multilingual sessions and documentation of vocabulary for knitting, tools, and materials in Arabic, Danish, English, and Tigrinya, the native language of Haile and Beyene. They collaborated with the interns to research vocabulary and exchange knowledge on textile history. To do so, Lervad abandoned traditional scholarly methods of terminological research—which takes text as the starting point—and instead interviewed the interns while knitting or sewing, as they talked about stitches, needles, knots, thread, and more. Additionally, the interns drew tools and techniques or found documentary films online and drew and marked words and concepts on charts with arrows ().Footnote55

Figure 13 A mapping exercise using a previous project exploring Arabic words for loom technology in Jordan as a starting point. Two interns spoke Tigrinya as their mother tongue and, having learned to knit during their first few days as interns, worked to build up relevant Tigrinya terminology for knitting and weaving. Photo: Christian Gaubert.

Knitting was beneficial for the women’s social well-being as it is contemplative and also provides a sense of accomplishment (). The wool and silk yarns used for knitting a traditional triangular Danish shawl were pleasant to work with and, in addition, soft and warm in the cold Nordic winter. Hours passed while talking about issues of life, families, home countries, and language, as scholars and participants exchanged experiences and views on textile-related issues. The participants asked each other: “Who taught you to knit?” “Do your children know the techniques?” “What is your way of knitting?” The discussions helped connect through an understanding of dress and how the refugees work with their clothes to adapt to their new life in Denmark.Footnote56

Figure 14 Alem Haile knitting as part of her internship at Center for Textile Research. The knitting activities were both for social interaction and to collect textile craft terminology in Tigrinya. December 2017. Photo: Susanne Lervad.

In their final evaluation of the internships, Haile and Beyene had encouraging and positive comments about the word and practice sessions. They prepared a presentation of their experiences for researchers at the Centre for Textile Research, explaining some of the Eritrean dress traditions and describing their work with knitting terminology. The research team and the refugees continued to be in touch via social media as well as by meeting in museums and the homes of the refugees. Lervad and Gaubert presented and published the Tigrinya vocabulary at several conferences on terminology with appropriate acknowledgment of Haile and Beyene’s contributions.Footnote57 What these encounters and language exchanges provided was an opening and enrichment of the historical and cultural landscape of textiles, uncovering previously undescribed interconnections and missing links.

Collaboration and Unequal Life Conditions

Through the collaboration between and among scholars, cultural institutions, and women with refugee or immigrant backgrounds, we aimed to explore mutually beneficial methods of learning. Even though researchers and participants differ in terms of educational background and socio-economic status—or precisely because of this—we sought to create a collaborative practice that attempted to reverse differences into opportunities. This was done by choosing themes in which refugee and migrant women participants were positioned as experts with the knowledge and skills from whom the scholars should listen to and learn from.

Refugee and migrant women often have an extensive network of other women, and they speak several languages and dialects that have not yet been explored in textile research, such as various Arabic dialects, Kurdish, Persian, Tigrinya, and, lately, Ukrainian.Footnote58 In the terminology research project, the participants acted as experts informing scholars; in exchange, scholars taught participants to knit. Even if not all women exhibited extensive textile skills, most women had parents, grandparents, aunts, and others on whose knowledge they could draw. Some participants contacted older friends and relatives via social media to help identify and translate more technical textile terminology. As a result, this team created an expansive vocabulary reference derived from women’s experiences gathered in a creative exploratory process, which also privileged individual participant’s cultures and knowledge.

Finding vehicles for the refugee participants to demonstrate their capacity for work—like the certificates of attendance and portfolios of work as facilitated in THREAD—was a good way of compensating for their lack of formalized or recognized qualifications. As the refugee women typically arrived in Denmark without formal educational papers or documentation of work experience, it turned out that some had textile skills and experience with making that they had documented on their mobile phones. By turning these images into professional portfolios, potential employers could locate their experience and level of skills, similar to the way professional designers demonstrate their work when applying for work in the Danish textile sector. Ultimately, all researchers have learned how both “languages”—words in multiple languages as well as textile crafting—are equally important components in engaging in activities with refugee and migrant women. This shared practice and understanding can help new audience groups feel included, engaged, passionate, and safe, not alienated and inferior in the museum space.

Within the new ICOM definition of museums, it will be necessary to reach out to new audiences and to facilitate their entry into museum spaces, and this requires new methods and new roles. Thus, we argue that the cultural brokers and facilitators were crucial in undertaking the projects. We also suggest introducing a third type, the institutional broker, as a bridge builder between infrequent or non-museum visitors and museums. There are certainly opportunities to engage museum staff with more diverse backgrounds to take on some of these roles.

Reflections and Perspectives

One could rightfully ask where the voices of the hundreds of women participants in the projects ended up, and what happened as we, the researchers, moved on to new projects. Only one project conducted “before and after” interviews with a very small group of women taking part in the Fenuun workshops of the THREAD project. Other than that, the focus has been to test and develop formats of inclusiveness and mutual exchange that encourage agency for women participants. While qualitative interviews about the effect of the projects on the individual lives of the women were not conducted, it was clear to the researchers, facilitators, and the cultural and institution brokers how “shared language” or the “third language” of textiles provided unique and exciting opportunities for inviting new audiences, like the women participants, to museum spaces.

Research on terminology and its use demonstrates how a seemingly everyday activity, such as crafting, can lead to completely new insights into textile history and the many interconnections across borders and time. The women enjoyed a shared understanding of aesthetics and techniques being mutually valuable and felt proud as they taught Lervad and Gaubert new terms. One word was “qamis,” which means dress, tunic, robe, blouse, and shirt.Footnote59 Being deprived of customary access to certain styles of dressing that were left behind in the old country, creating a space where all aesthetics are welcomed has been invaluable in establishing trust in the projects.

The projects provided the mediators with the knowledge and capacity for trust building, growing role models, and testing out psychological barriers to being at museums. With regards to distance, even for what might seem a short distance—from the suburb of Tingbjerg and into the city center of Copenhagen—was at first an impenetrable barrier for the women of Igne:Oya. Living in a confined suburban area, many women participants did not have solid shoes, as their outdoor activity was typically a stroll down to the neighborhood supermarket wearing slippers. However, Rolf Larsen persuaded all women to travel in public transportation or in a hired bus to visit several museums, and even to Kolding, more than 300 km from their home. It may seem difficult to understand the empowering element of taking a bus 14 km into town, but this eventually helped women to also find the confidence to give talks about their skills and crafts on numerous occasions.

A collective learning process also shows the tacit label of textile skills and everyday creativity are much more relevant language for communicating museum activities than words, especially for this audience group of refugee and immigrant women who struggle with the pressure of learning Danish or being a newcomer in Denmark. Textile crafting proved to be a good method for building trust in a space where all people crafted together regardless of title, education, cultural background, or social status. We learn from each other, taking a short break from a sometimes-hard reality. The participants emphasize the social networks created in the workshops, as reflected by Igne:Oya participant Nagrem Jasim:

I started in the textile workshop from day one. It was a bit difficult at first. I meet some other people that I don’t know. I don’t know what they do and what they can do. But little by little, we became very good friends.Footnote60

Figure 15 Nagheem Jasim started in Igne:Oya and continued in formal education in textile design in 2022. Here photographed in class at University College Copenhagen. Photo: Anne Sørensen.

I like to sew clothes, but I sew in my mother’s way, where you measure with your fingers and hand, but I want to learn it the right way. I now attend University College Copenhagen. I am studying textile design. I want to be a tailor and open my own shop. I would like to sew wedding dresses and party dresses and have many customers.Footnote62

In 2022 Jasim enrolled in a formal design education with the aim of becoming a textile designer and opening her own business.

Conclusion

The case studies presented here have each in their way expanded knowledge and cooperation beyond museums and universities, challenging us intellectually and academically to rethink museum practices, textile cultural heritage and transmission of craft, and, more generally, interdisciplinary and inter-sectoral research collaboration. In the projects, we aimed to work through mutual learning and design collaborations based on the expert knowledge that the women participants offered. This focus on skills and craft, however, did not remedy our very uneven professional situations or our unequal life circumstances. However, the craft approach is crucial to level the playing field in enabling museums as contact zones.

The textile craft workshops hosted in museums taught us that open invitations, the use of social media, or the appearance of open doors are not sufficient tools in engaging Danish refugee and migrant communities, at least not in the beginning. If we are to develop museums in an innovative manner and engage with diverse communities, it is necessary to join forces with NGOs, informal networks, and migrant organizations, and to pair up with resourceful persons and people of trust in the migrant communities.

Museums and exhibitions continue to work to underscore the universality of textile and craft techniques and to initiate conversations about textiles across cultures. Techniques for crafting can be viewed as methods for keeping cultural heritage alive, in a time with a dramatic loss of historical textile knowledge.Footnote63 Textile items in museums remind us that globally, textile cultural heritage is vanishing both as tacit and material culture and that this primarily and historically gendered knowledge has value as part of a larger cultural sustainability agenda. From an academic point of view, the four projects offer many new, concrete, and contemporary perspectives on issues that we strove to understand in the past, such as ancient textile production, training, and how to gain textile skills and pass them on.Footnote64 They also situated textile crafts in discussions of technology, aesthetics, and resources, which sheds light on other cultures, past and present.

We thank Jane Malcolm-Davies for her generous help and inspiration. We are grateful for the stimulating suggestions provided by the editors and reviewers. All quotes by participants have been translated by the authors into English.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anne Louise Bang

Dr Anne Louise Bang is a Senior Associate Professor at the Centre for Creative Industries & Professions at VIA University College in Denmark. Additionally, she is a Professor II at University of South-Eastern Norway where she is affiliated with the group Research on Embodied Making and Learning. She has a background as a textile designer and weaver. Her research is experimental within textile design, materials, technology, and sustainability focusing on development of design practice. A core interest is development of tools suited for dialogue between diverse groups of people around sensuous and experiential aspects of textiles.

Gitte Engholm

Dr Gitte Engholm is curator and anthropologist at the National Museum of Denmark, where she has been responsible for the museum’s outreach programs since 2005. She has profound experience with refugees from various employments and fieldworks in refugee camps. From 2017 to 2020 she initiated the project CULINN (Cultural Citizenship and Innovation). For several years textiles, crafts, and needlework have been the key to her work for a more tactile and inclusive museum.

Susanne Lervad

Dr Susanne Lervad is a terminologist and co-director at The Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen. She studied specialized communication at the University of Southern Denmark and Université Lyon 2 in France. She is a member of the Centre de Recherche en Linguistique Appliquée Terminologie Cerla/Lyon 2, within the field of textiles—especially weaving and the configurations of verbal and nonverbal representation of concepts in terminology. She is a member of the terminology associations CIETA, DANTERM/NORDTERM and the EAFT, and the owner of, and terminology coach in, the consultancy firm Termplus Aps.

Marie-Louise Nosch

Professor Marie-Louise B. Nosch is trained in ancient history and wrote her PhD on Bronze Age Aegean textile production as documented in the Mycenaean Linear B archives of the second millennium BCE. She directed the Centre for Textile Research in the University of Copenhagen from 2005 to 2016. She has published numerous papers on ancient textile crafts, textile tools, and textile terminology, both in antiquity and on the Silk Roads. Her research includes dress history, military uniforms, and modest fashion.

Else Skjold

Dr Else Skjold is Associate Professor and director of KLOTHING—Center for Apparel, Textiles & Ecology Research at the Royal Danish Academy. She is workstream leader of textiles research in the national mission-based partnership TRACE (TRAnsition towards a Circular Economy). Her research focuses primarily on the interlink between so-called wardrobe research that investigates user experiences of garments, and sustainable and circular transition of the textiles sector. Her work is typically action-based and involves practice-based design development as well as design thinking methods for enhancing collaborative processes between various stakeholders.

Notes

1 Gitte Engholm, Mellem innovation & integrationen. Når museer møder nytilkomne borgere. (København: Nationalmuseet, 2000) and <www.CULINN.dk>

2 Jane Malcolm-Davies and Marie-Louise Nosch, “THREAD: A Meeting Place for Scholars and Refugees in Textile and Dress Research,” Archaeological Textiles Review 60 (2018): 118–24; Else Skjold, Marie-Louise Nosch, Jane Malcolm-Davies, and Anne Louise Bang, THREADs that Connect. Social Innovation through Textiles (Kolding, Designskole og Københavns Universitet, 2000). See also <https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/research-programmes-and-projects/previous-programmes-and-projects/thread/>

3 Anne Louise Bang, Marie-Louise Nosch, and Else Skjold, “The Fabric of My Life,” Formkraft 2022 (<https://formkraft.dk/en/the-fabric-of-my-life/2020/>). See also <https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/research-programmes-and-projects/the-fabric-of-my-life/>

4 Maria Vlachou (coord.), The Inclusion of Migrants and Refugees: The Role of Cultural Organisations (Almeda: Acesso Cultura, 2017), <https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2017-06/Access-Culture-migrants-refugees.pdf>

6 Eurostat: Culture Statistics (2019) Theme: Population and Social Conditions. Collection: Statistical Books, © Bruxelles: European Union, 2019, 125. Danskernes Kulturvaner (København: Kulturministeriet, 2012) <https://kum.dk/fileadmin/_kum/5_Publikationer/2012/Bogen_danskernes_kulturvaner_pdfa.pdf>

7 Mellem ballet og biografer—kultur ifølge danskerne (København: Mandag Morgen, 2019).

8 A survey of non-users in Danish museums was gathered in the report Den nationale brugerundersøgelse 2018 (Kulturministeriet, København, 2018) <https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/SLKS/Services/Publikationer/Den_nationale_brugerundersoegelse._AArsrapport_2018.pdf>

9 Toby Slade and M. Angela Jansen, “Letter from the Editors: Decoloniality and Fashion,” Fashion Theory 24, no. 6 (2020): 809–14, <https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800983>

10 Eileen Hooper Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge (Milton Park: Routledge, 1992).

11 Eileen Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture (Milton Park: Routledge, 2000).

12 ICOM Strategic Plan 2016–2022: <https://icom.museum/en/ressource/icoms-strategic-plan-2016-2022/>

14 Graham Black, The Engaging Museum. Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement (Milton Park: Routledge, 2018) and Nina Simon, The Participatory Museum (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010).

15 Mary Louise Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” Profession 91 (1991): 33–40. Amanda G. Berglund wrote her Master’s thesis based on analysis and ethnographic fieldworks in the Sunday Pursuits and she used contact zones as one of her theoretical perspectives. We are grateful for the access to her unpublished thesis: “Mødet med museet. Kontaktsoner i CULINN,” Master’s thesis (Roskilde University, 2019).

16 James Clifford, “Museums as Contact Zones,” in Routes—Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Harvard University Press, 1997), 188–220, especially 192.

17 Robin Boast, “Neocolonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited,” Museum Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2011): 56–70; Amber R. Clifford-Napoleone, “A New Tradition: A Reflection on Collaboration and Contact Zones,” The Journal of Museum Education 38, no. 2 (2013): 187–92.

18 Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day (Trowbridge: Paragon House, 1989).

19 Else Skjold, “Clothed Memories and Clothed Futures: A Wardrobe Study on Integration and Modest Fashion,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 8, no. 1 (2021): 25–43. <https://doi.org/10.1386/infs_00023_1>

20 Else Skjold, “Towards Sustainable Fashion Media,” in Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion, ed. Kate Fletcher and M. Tham (Milton Park: Routledge, 2016), 171–80.

21 Katherine N. Cotter, Alexander P. Christensen, and Paul J. Silvia, “Creativity’s Role in Everyday Life,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2nd edition, ed. James C. Kaufman and Robert J. Sternberg (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 640–52.

22 Tamlin S. Conner, Colin DeYoung, and Paul J. Silvia, “Everyday Creative Activity as a Path to Flourishing,” Journal of Positive Psychology 13, no. 2 (2018): 181–9.

23 See examples in Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

24 Ruth Richards, “Everyday Creativity: Process and Way of Life—Four Key Issues,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2nd edition, ed. James C. Kaufman and Robert J. Sternberg (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 189–215.

25 Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 5.

26 Report: Veje til beskæftigelse for flygtninge- og indvandrerkvinder (København: Nordisk Ministerråd, 2019). For a study of middle-aged to elderly migrant and refugee women in Denmark and their perspectives, see Maria Kristensen, Linnea Lue Kessing, Marie Norredam, and Allan Krasnik, “Migrants’ Perspectives of Aging in Denmark and Attitudes Towards Remigration: Findings from a Qualitative Study,” BMC Health Services Research 15 (2015): 225.

27 Ruth Richards, “Everyday Creativity: Process and Way of Life—Four Key Issues,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2nd edition, ed. James C. Kaufman and Robert J. (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 190.

28 Anne Kirketerp, Craft psykologi. Sundhedsfremmende effekter ved håndarbejde og håndværk (Hjørring: Mailand, 2020).

29 Katherine Robinson, “Everyday Multiculturalism in the Public Library: Taking Knitting Together Seriously,” Sociology 54, no. 3 (2020): 556–72.

30 Quote from CBS film Tekstil i Tingbjerg by Eva Boxenbaum and Kasper Christiansen: <https://tekstil-tingbjerg.cbs.dk/tekstilvaerkstedet-igneoya/>

31 Tråden ud af verden, three films produced by Kosmopol, by Morten Raarup and Anne Sørensen. See <https://www.tv2kosmopol.dk/traaden-ud-af-tingbjerg/to-verdener-moedes-13>

32 Anne Louise Bang, “Emotional Value of Applied Textiles—Dialogue-oriented and Participatory Approaches to Textile Design,” PhD thesis 2010 (Gabriel A/S & Kolding School of Design, Kolding, 2013); Anne Louise Bang, “The Repertory Grid as a Tool for Dialog about Emotional Value of Textiles,” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice 1, no. 1 (2013): 9–26; Anne Louise Bang, Agnese Caglio, Vibeke Riisberg, and Karen Louise Hasling, “Ways of Talking With (and About) Materials,” in Nordes 2015: Design Ecologies. Nordes Conference Series (DRS Digital Library, 2015). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21606/nordes.2015.043; Vibeke Riisberg, Anne Louise Bang, Laura Locher, and Alina Breuil Moat, “Awareness: Tactility and Experience as Transformational Strategy,” in Shapeshifting: A Conference on Transformative Paradigms of Fashion and Textile Design, ed. Frances Joseph, Mandy Smith, Miranda Smitheram, and Jan Hamon (Auckland University of Technology, 2015). https://hdl.handle.net/10292/8566; Karen Marie Hasling and Anne Louise Bang, “How Associative Material Characteristics Create Textile Reflection in Design Education,” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice 3 (2016): 27–46; Trine Møller, Louise Ravnløkke, and Anne Louise Bang, “Tangible Dialogue Tools—Mediating Between Non-verbal Users and Everyday Experts,” in Proceedings of Nordcode, Kolding, Denmark, 2016 (2016). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326904584_TANGIBLE_DIALOGUE_TOOLS_Mediating_Between_Non-verbal_Users_and_Everyday_Experts

33 “New to Denmark” is the official portal for foreign nationals who wish to visit, live, or work in Denmark: <https://nyidanmark.dk>

34 Information about Danish social housing can be found at VIVE—The Danish Centre for Social Science Research: <https://www.vive.dk/da/temaer/boligomraader/>

35 Sujin Jang, “Cultural Brokerage and Creative Performance in Multicultural Teams,” Organization Science 28, no. 6 (2017): 993–1009.

36 Quote from CBS film Tekstil i Tingbjerg.

37 Quote from CBS film Tekstil i Tingbjerg.

38 Frank T. Anbari, Erzhen Khilkhanova, Maria V. Romanova, Mateo Ruggia, Crystal Han-Huei Tsay, and Stuart A. Umpleby, “Managing Cross Cultural Differences in Projects,” Paper presented at PMI Research Conference Washington, DC 2010, <https://www.academia.edu/35684574/CULTURAL_DIFFERENCES_IN_PROJECTS>

39 < https://sheworks.dk>

40 Christian Gaubert and Susanne Lervad, “Multilingual Textile Terminology in the Thread Project,” Terminfo 1 (2019), <http://www.terminfo.fi/sisalto/the-thread-project–a-multilingual-approach-to-textile-terminology-562.html>

41 Gitte Engholm, Mellem innovation & integrationen. Når museer møder nytilkomne borgere. (Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet, 2000).

42 Lakshimi Sigurdsson and Gitte Engholm, “Danmark med nye øjne: Deltagerinddragelse og dynamiske ruter i medborgerskabsdidaktik,” Tilde Rapportserie 17 (2020): 29–46.

43 Trine Møller, Louise Ravnløkke, and Anne Louise Bang, “Tangible Dialogue Tools—Mediating Between Non-verbal Users and Everyday Experts,” in Proceedings of Nordcode, Kolding, Denmark, 2016 (2016). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326904584_TANGIBLE_DIALOGUE_TOOLS_Mediating_Between_Non-verbal_Users_and_Everyday_Experts

44 Katherine Robinson, “Everyday Multiculturalism in the Public Library: Taking Knitting Together Seriously,” Sociology 54, no. 3 (2020): 556–72.

45 Karen Grøn,” Fællesskabte kunstværker på Trapholt,” Formkraft 2022, <https://trapholt.dk/graenseloese-sting-et-kunstvaerk-skabt-i-faellesskab/>

47 Marie-Louise Nosch and Else Skjold, “From Tehran to Thisted via Textiles: Interviews with Two Textile Artists on Textile as a Successful Foundation and Privileged Ground for Co-creation and Memory,” Artex Journal 1 (2022): 67–78.

48 Igne:Oya—Made in Tingbjerg. See <https://www.facebook.com/igneoyacph/videos?locale=da_DK>

49 Igne:Oya—Made in Tingbjerg See <https://www.facebook.com/igneoyacph/videos?locale=da_DK>

50 The exhibition catalogue is included in “Newsletter 8, July 2022”: <https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/research-programmes-and-projects/the-fabric-of-my-life/>

54 Gaubert and Lervad, “Multilingual Textile Terminology in the Thread Project.”

55 Gaubert and Lervad, “Multilingual Textile Terminology in the Thread Project.”

56 See also the analysis of knitting session in a UK public library: Katherine Robinson, “Everyday Multiculturalism in the Public Library: Taking Knitting Together Seriously,” Sociology 54, no. 3 (2020): 556–72.

57 Christian Gaubert and Susanne Lervad, “Textile Terminology in the Thread Project - A Multilingual Approach,” Presentation at the NORDTERM Conference at the University of Copenhagen, June 2019 (2019): 22–4.

58 A recent result of collaboration between textile scholars from Denmark, Canada, the US, Ukraine, and a Ukrainian refugee intern: Magali-An Berthon, Sophia Hayda, Tatjana Krupa, Juliaj Lazorenko, and Marie-Louise Nosch, “Narrative and Material Tools of Resistance: Mobilising Textile Crafts, Heritage and Fashion in the Context of Ukraine’s Invasion (2022–2023),” in Euroweb Anthology, ed. Kerstin Dross-Krüpe, Louise Quillian, and Kalliopi Sarri (Lincoln, Nebraska: Zea Books, 2024).

59 Skjold et al., THREADs that Connect, 23 and 31.

60 Quote from CBS film Tekstil i Tingbjerg.

63 Camilla Ebert, Mary Harlow, Eva Andersson Strand, and Lena Bjerregaard eds. Traditional Textile Craft—An Intangible Cultural Heritage? (University of Copenhagen, 2016), <https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/conferences/2014/E-Book_Traditional_textile_crafts.pdf>

64 Marie-Louise Nosch, “How to Become a Textile Worker? Training and Apprenticeship of Child Labour in the Bronze Age,” in Textile Workers. Skills, Labour and Status of Textile Craftspeople Between the Prehistoric Aegean and the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the Workshop held at 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, ed. Louise Quillien and Kalliopi Sarri, OREA—Oriental and European Archaeology 13 (Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2020), 91–108; Feng Zhao and Marie-Louise Nosch, eds. Textiles and Dress cultures along the Silk Roads. Thematic Collection of the Cultural Exchanges along the Silk Roads (Paris: UNESCO Publications, 2022).