Abstract

Amy Fry, Electronic Resources Coordinator for Bowling Green State University (BGSU), presented a comprehensive analysis of what libraries can and should do to help users access their databases. She discussed an ongoing project to update her library's database Web pages to enhance their utility for library patrons. During her presentation she explained how she identified best practices in Association of Research Libraries member libraries, made recommendations based on these best practices, and discussed the work in implementing her recommendations. Fry also discussed a Web page usability study conducted with her colleague, BGSU's Reference Coordinator, Linda Rich.

INTRODUCTION

Amy Fry began her presentation noting that Bowling Green State University (BGSU) Libraries have developed a significant number of lists and guides for their databases and that they were in need of updating. BGSU Web pages provide database listings by subject and alphabetically. There are also separate Web pages providing a full resource record for each of their approximately three hundred databases. These individual pages provide a link to the database, brief and full descriptions, and other elements. The library uses Innovative Interface's electronic resource management (ERM) system to generate its A–Z list of databases and the full machine-readable cataloging (MARC) records for the databases. Fry decided to look at Web pages from libraries belonging to the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) to try to develop a set of best practices that could be incorporated in a redesign or enhancement of her library's pages.

BEST PRACTICES RESEARCH

Fry reviewed the pages listing or describing the databases of 114 ARL member libraries (excluding seven national and special libraries and four libraries whose pages were not accessible without logging in). She used spreadsheets to record and compare the existence of full resource records, the software used, the use of discovery or federated searching, link nomenclature, how databases were ordered in subject lists, and how icons and graphics were used. She also researched the findings of other ARL library studies.Footnote 1

The presenter showed several examples of online lists of databases from various libraries as she discussed her own findings regarding Web page construction and usage. Most libraries in her study (71.1 percent) appear to use homegrown software to generate their lists of databases. Sites using Ex Libris MetaLib come in a distant second (12.3 percent). Most libraries (97 percent) provide an A–Z list of databases. Eighty percent also provide a databases-by-subject list; 73 percent provide full resource records; and 64 percent of ARL libraries use all three methods to provide information on their databases holdings.

Fry paid special attention to how databases-by-subject pages were actually constructed and prioritized. A small majority of libraries only use alphabetical listings, while 41.8 percent used relevance rankings within a subject or topic area. Seven percent listed databases by format. Use of icons or graphics were employed by 64 (56 percent) of the libraries reviewed. Icons were used most commonly to denote access restrictions or the presence of more information. Link nomenclature most often began with the term “Databases,” but the words “Articles,” “E” or “Electronic,” “Find,” and “Research” were also used frequently.

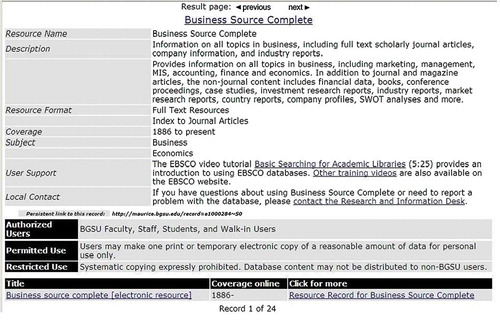

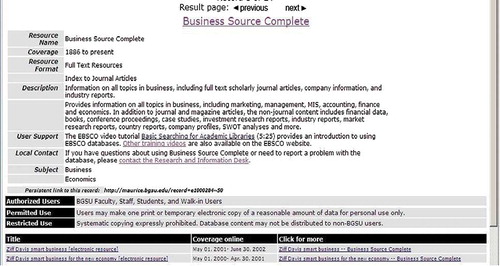

Based on this research, Fry updated BGSU's ERM resource records by reorganizing information, increasing white space, shortening text, using visual keys, and standardizing fonts. These changes can be seen by comparing to .

USABILITY TESTING

After making these changes Fry and her colleague, Linda Rich, started usability testing with students. Fry referenced Steve Krug's Don't Make Me Think!: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, Footnote 2 one of the resources used in planning the study. While most library studies address usability of online catalogs, Fry and Rich wanted to look at the usability of their electronic database pages.

Fry and Rich followed the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) definition of usability as “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”Footnote 3 Five attributes of usability are as follows:

| • | Ease of learning | ||||

| • | Efficiency of use | ||||

| • | Memorability | ||||

| • | Error frequency and severity | ||||

| • | Subjective satisfaction | ||||

Early in 2010 the researchers began preparing for the study. They were able to obtain financing to recruit students to complete the one-hour test. Participants were given $20 gift cards. Nine undergraduate students and six graduate students were recruited. Fry focused her discussion on three areas covered in the study: the home page, computer tasks, and database pages.

The Home Page

In the first portion of the study, students were given a paper copy of the library home page and were asked to highlight and explain the links they frequently used, the ones that they did not understand, and the ones that they felt were unnecessary. Nine of the fifteen students reported using the links for EBSCO and OhioLINK (the statewide catalog). About half of the participants used links for course reserves and a link called “My Library Account.” Links that were found most confusing were links to the Digital Resource Commons and ILLiad.

Computer Tasks

In the second part, students were asked to do the following:

| 1. | Find a named book (given title and author last name) | ||||

| 2. | Find scholarly articles on a topic | ||||

| 3. | Find another source for scholarly articles on a topic | ||||

| 4. | Find a named database | ||||

| 5. | Find a named journal article (given an American Psychological Assocition [APA] formatted citation) | ||||

All students were able to find the named book while the researchers recorded the number of attempts to complete the task and where the task was initially started. While most students used the catalog search box on the home page, most students also needed more than one attempt to find the book. Only three of the fifteen found the book on their first try. One student required nine attempts after first beginning the search by using the BGSU Libraries catalog link.

When searching for a scholarly article on a specifically chosen topic, most students used the EBSCO link. Only one student was unsuccessful after initiating the search by choosing the e-journals link and then going on to try six more times.

For their third task in this part, students were asked to choose another resource for finding a scholarly article on their topic. Six students were successful by either selecting a known database or by selecting a known e-journal using a variety of starting points. Four students did not know how to complete the task but were able to find scholarly articles through other methods. One student searched for her topic using Google and combined it with the word “Springer.” Four students could not complete the task, choosing inappropriate subjects that led them to inappropriate databases or titles lists.

Students were asked to find a named database and most who were successful used the databases A–Z list. Students who were unsuccessful used starting points such as the e-journals link or the databases-by-subject lists.

The final task in this part of the study was to find a named article after receiving an APA-formatted citation. Seven of the students were successful when using the article title for their search; five were successful using the author for their search; and three were successful using the journal title for their search. Six students used the e-journals link as their starting point. EBSCO was the second most successful starting point. Google and EBSCO were the eventual sources for finding the actual journal article.

Database Pages

Study participants were asked to look at printouts of the databases Web pages in the third part of the overall study and mark links that they used, were confused about, or thought unnecessary. The researchers learned that students did not normally use the A–Z list of databases and very often were not sure what it contained. They were much more comfortable with the databases-by-subject lists. In the full records, students were asked to circle items that they thought were important. They circled coverage dates, full text, and even licensing information. Resource descriptions were also considered important.

Students were confused by the terms “Mobile Access” and “On-Campus Access,” but were reluctant to mark out anything as unnecessary. Most notably, however, they did mark out links to tutorials. Fry noted that students want to be able to use a database immediately and not have to deal with learning the mechanics needed to search the database.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Fry commented that the findings of their research suggested that students stick with what they know, as evidenced by the majority using EBSCO's Academic Search Complete. Unfortunately, students also mistakenly believed that all EBSCO databases would be included in a search of this particular database. Students will do what their professors tell them to do, and use Google as a backup. They will only use specific library pages if a professor tells them to do so. Students look for search boxes. One of the participants kept repeating that Google was powerful. The student proved it by using Google to find anything that the researchers asked for.

Fry suggested that Web pages with A–Z lists of databases require too much guessing to figure out the right path to finding results. While subject lists are an improvement, Fry felt that they were more useful to librarians than to patrons. However, students still associated lists with finding articles and books, but not with finding databases.

Fry offered several recommendations based on her study of ARL member libraries and the BGSU usability study. Libraries need to get specific about marketing. If students already know a particular database such as EBSCO Academic Search Complete, librarians should market and associate other databases that have commonalities with the popular database. Commercial ERM systems need to support good Web pages that provide flexibility to the library and eliminate the time-consuming process of developing homegrown database pages. Discovery layer software needs to be utilized. Fry theorized that study participants who were given the task of finding a named article would have been successful on their first try with software that combined multiple search paths.

DISCUSSION

During a brief discussion period, Fry was asked if she had noticed differences between graduate participants and undergraduate participants. She indicated that there did not seem to be a marked difference between these two groups. Differences in search strategy experience were noted between freshmen and upperclassmen. She also noted that usability had not been tested with faculty.

Several audience members had also conducted usability studies and shared some of their experiences. LibGuides were mentioned as an effective tool for database description Web pages. Too often librarians think that they know what students need and they design Web pages according to their own perceptions. Another audience member suggested that taped sessions were a good way for librarians to actually see what their patrons were doing. Fry confirmed that observation by noting that students would often ignore the middle part of the Web page when looking for what they considered the important information—a practice that would not necessarily be incorporated into Web design unless someone had been able to observe the strategy.

Fry's presentation outlined a very efficient methodology for discovering best practices by examining database pages from ARL libraries, and then comparing those findings with empirical research gained through usability testing of library Web pages with student volunteers. Fry used these findings to construct and organize the library's electronic resources lists and guides in ways that best fit the specific needs of their students.

Notes

1. Dana M. Caudle and Cecilia M. Schmitz, “Web Access to Electronic Journals and Databases in ARL Libraries,” Journal of Web Librarianship 1, no. 1 (2007): 3, doi:10.1300/J502v01n01_02; Laura B. Cohen and Matthew M. Calsada, “Web Accessible Databases for Electronic Resource Collections: A Case Study and its Implications,” Electronic Library 21, no. 1 (2003): 31–38, doi:10.1108/02640470310462399; Jay Shorten, “What Do Libraries Really Do with Electronic Resources? The Practice in 2003,” Acquisitions Librarian 18, no. 35 (2006): 55–73, doi:10.1300/J101v18n35_05.

2. Steve Krug, Don't Make Me Think!: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, CA: New Riders Publishing, 2006).

3. ISO Concept Database, https://cdb.iso.org/ (ISO 9241-11; 1998, definition 3.1; accessed December 16, 2010).