Abstract

Stephen Rhind-Tutt of Alexander Street Press described his perspective on historical trends in the information industries, particularly publishing, and extrapolates them to the future. The presentation begins with an examination of the current challenges facing the information industries. This is followed by a definition of technology forecasting and its application to the information industries, showing how the Internet lends itself to particular types of development and the wants and needs of information customers drive change. The likely direction of such change in the information industry is outlined. Members of the industry must choose to embrace and evolve with these changes in order to remain relevant.

Stephen Rhind-Tutt prefaced his remarks by expressing his gratitude for being invited to speak and set the stage by describing his perspective. He explained that, while he is a member of the same broad industry as most of the audience, that is the library community, he recognized that many in the audience work with serials while he is focused on primary sources and streaming audio and video. He asked the audience to bear in mind his perspective as a small publisher. The purpose of his presentation was to examine the historical trends he sees in the industry and to extrapolate them to the future.

THE LANDSCAPE… CHALLENGES FACING US

One of the most striking things about the information available on the web is the rate at which it is growing. For example, as of the latest available statistics, in 2011 YouTube had more than a trillion views, that is, roughly 140 views for every person on the planet.Footnote1 Content on the web is growing at an exponential rate. That represents a huge change, which will require a change in the way those in the information industries like libraries and publishers think about delivering information resources.

Similarly striking is the lack of change in the focus of NASIG conference topics since 1990. Topics like shrinking budgets, rising journal costs, the journal as a means of scholarly communication, new roles for librarians, and “if publishers perish, what would be lost,” were topics then, and we are still examining them today. They reflect the intertwined fears of librarians and publishers and almost every part of the library community that they are at risk of being made redundant. There’s the fear that publishers will not be needed because of Open Access and because libraries will publish themselves or that reference publishers will disappear because of Wikipedia. Libraries will not be needed because content will be free or because vendors will go directly to faculty. Teaching faculty will not be needed because online learning enables millions to be taught automatically. Universities will not be needed because it is cheaper and easier to educate online. We have not been ambushed by change. We know very well it has been happening for a long time.

K. G. SchneiderFootnote2 expresses these ideas eloquently when she says:

“All technologies evolve and die,”

“every technology you learned about in library school will be dead one day,”

“you are not a format you are a service,”

“the OPAC [Online Public Access Catalog] is not the sun, it’s at best a distant planet, every year moving further away from the solar system,”

“the user is the sun, the user is the magic element that transforms librarianship from a gatekeeping trade to a services profession,”

“the user is not broken,”

“we cannot whine about how Google is taking the user away from us,”

“the user gets what the user wants,”

“your system is broken until proven otherwise,” and

“that vendor who just sold you the million dollar system because ‘librarians need to help people’ doesn’t have a clue what he’s talking about and his system is broken too.”

She is not only eloquent on the topic; her comments are only one example of a steady drumbeat of the smartest people in the information industries telling us the same thing over and over, that all technologies evolve and die. But despite that drumbeat, the industry moves slowly in comparison to consumer web companies.

What our customers want creates great opportunities. Students want to learn better, faster, and cheaper. We cannot continue charging students hundreds of thousands of dollars to attend college. If we do so only a very small number of people will get a great education. Those involved in practicing professions, whether law or medicine or other, have to perform better. For the sake of humanity, we need researchers to be able to discover the next penicillin faster, better. We need to help students learn, better, faster, and cheaper. We need faculty to teach better.

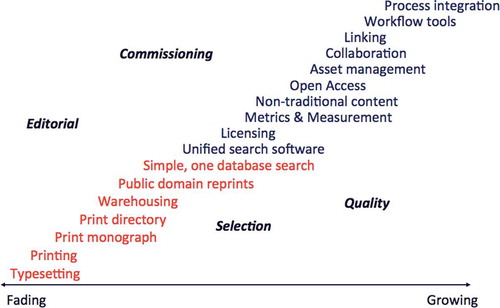

illustrates that, far from technology driving our industry to an end, it enables it to continue. In the lower left quadrant are the fading technologies, those that were once very important, but are gradually becoming less relevant. Over time, moving to the upper right quadrant, are the emerging technologies, those that are coming to the fore and enabling us to serve customers far better than we have done in the past. It is becoming more and more obvious that this is a never-ending cycle, there is always somewhere to go, always a next stage. What those in the information industries must do is run up this graph, dispense with the older technologies, dispense with the things that are less relevant, and get as fast as we can to serving our customers as we move up the chain.

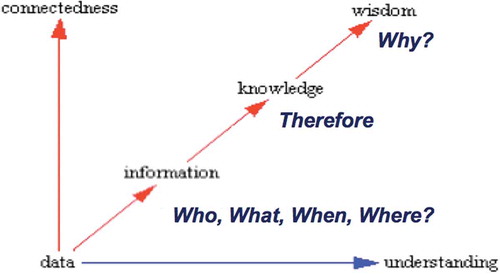

illustrates the notion that as connectedness between people and ideas and understanding both increase, systems enable us to move from perceiving data to creating wisdom. In the information industry, we are moving from a time of data to a time of information and toward a time of knowledge. In the future we are going to be moving toward wisdom. Our customers do not want to search, they want to find. Reading journals is not their primary function, their function is to learn things faster and so propel us toward wisdom. In the next 20, 30, or 40 years we are going to be in a position where systems help people to answer questions in an instant, and where information is baked into any number of online tools helping us practice, educate, learn, and understand better than ever before.

Figure 2 Somewhere to run to.Footnote3

TECHNOLOGY FORECASTING

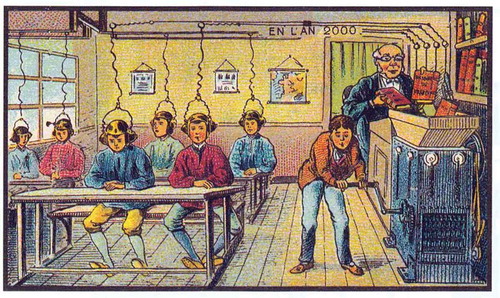

If we accept there are great opportunities and customer needs for the future, then let’s explore techniques that help us forecast how technology will be able to respond. Technology forecasting “is concerned with the investigation of new trends, radically new technologies, and new forces which could arise from the interplay of factors such as new public concerns, national policies and scientific discoveries. Many of these forces are beyond the control, influence, and knowledge of individual companies.”Footnote4 depicts a postcard created in the first decade of the twentieth century that predicts what a classroom will look like in the year 2000. Some students are pressing books into a machine while others sit at desks with caps on their heads that are wired to the machine.

Figure 3 Such future gazing may seem unscientific and a rather trivial way to plan, but if trends are measured and extrapolated, if one examines the practical benefits of new technologies and how they will likely influence each other, and if one explores unmet customer demand—one can indeed project the future with accuracy.

The transportation industry in the same era—the early twentieth century—provides instructive parallels to the information industry today. At the time there was a great deal of debate about what an automobile should be called. Nineteen-hundreds bicycle manufacturers presumably championed the word quadricycle, while carriage makers probably liked horseless carriage better. People were trying to grasp what the new thing is by framing it in the past. The same is true today with e-books and e-journals. The 1920 Rolls Royce Coupe did not include a roof over the driver’s seat. Why? By 1920 engines could comfortably cope with the added weight—it would have been easy to add one. But they did not think to—perhaps they were following an earlier paradigm when horse driven carriages could not cope with the additional weight. In the future information industry one wonders how many seemingly essential features will seem redundant. How important are book covers when most users are led by search engines to pages within a book?

And projecting the future of cars in 1900 forward was not so hard either. By 1910 it was common knowledge that future cars would be faster, safer, gas driven, and more luxurious. Fast forward to the twenty-first century, is there any question that in the next forty or fifty years cars will not only be networked but also safer, sharable, and even self-driving?

The Future is Clear Enough to Act on

The OCLC Environmental Scan report from 2003Footnote5 predicted our movement from the computing era, when we started with mainframe computing and then moved to personal computing, into the connectivity era, where we started with physical connectivity via networking, moved through logical connectivity via wireless networking and semantic indexing, to the embedded connectivity we have today that’s smart and dynamic. The move from Boolean searching to simple searching exemplifies progress in the information industries from 2003 to 2015 clearly. Boolean searching was the norm in 2000 when Google said that simple searching was important, and now publisher after publisher, OPAC vendor after OPAC vendor has embraced simple searching. It’s one of many instances over the past 12 years when the information industry was led by the consumer industry.

[The speaker displays an image.] The image illustrates some more examples. What Google did for simple searching Facebook did for social networking, and after a couple of years delay, the information industries had their own versions of social networking in the form of LibGuides and Mendeley. Napster gave birth to massive audio file sharing on the web and two years later the library version of Classical.com came out. Web-based video sharing followed a similar path.

From this perspective, the future is clear enough to act on today. Open Access is likely to continue to grow, machine-based indexing will improve, students will become more media centric. When Wikipedia started its life it had a poor reputation among academics, but that reputation has improved and is likely to continue to improve. The cost of space and storage are likely to continue to decrease and the use of mobile devices in education is likely to increase. These are trends that are predictable and it’s incumbent upon the information industries to decide what they mean for our organizations.

RESPECT THE MEDIUM

A key part of technology forecasting is to understand the medium that one is working in. A carpenter works in different types of wood. He understands that cork is not a good material from which to make a table, but oak is. The architect Louis Kahn is rumored to have told his students “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And you say to brick, ‘Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.’ And then you say: ‘What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.” The material, or the medium, shapes the way it is used.Footnote6

Consider the Internet as the medium in which the information industries work. As a medium, it is atomic; that is, it favors articles over monographs, short clips rather than long films. It is also enormously pliable. At the core it is just ones and zeros—there’s nothing simpler. That same simplicity can be layered over and over again to create ever more complex functionality.

Because it’s atomic, linking is key. We in the information industries are not yet taking enough advantage of that. If you have something on the Internet that is not connected to anything else no one is ever going to find it. The interlinkages between information packets on the web are, in some ways, more important than the information package themselves.

The Internet as a medium has enormous benefits over physical books. The cost per item, per person of an electronic journal, even with an expensive “Big Deal” journal, is tiny in comparison to the cost of a book because size in this medium can be unlimited. A great deal of effort is made, for example, to make textbooks available only as integrated, single units. But the medium of the Internet enables us to split the same textbooks into learning moments that could be used independently of each other. The Internet asks us to have both long form and short form “atomic” content.

As mentioned above, it’s hard to dispense with earlier paradigms. Envisioning a journal article with associated data, video, interviews, and more is akin to calling an automobile a quadricycle. The journal publisher sees the future as a journal just like the bicycle manufacturers saw the automobile as two bicycles together with an engine. The truth is that it is something genuinely new that corresponds to the new medium. Sometimes this kind of thinking extends to functionality. A key value of the Internet medium, the ability to share, was negated by the first NetLibrary e-book models using a one user check-out model.

Sometimes in history, taking advantage of the medium has to take a step back because of societal pressure. Maybe NetLibrary was unable to get the rights to the books in its collections without limiting shareability. But in the long run the medium would win out—someone would exploit the ability of the medium to share. That is what happened—ebrary and others developed products that allowed books to be shared more broadly. NetLibrary responded and moved to a broader model of sharing. Overall there is steady, predictable movement.

WHAT THE CUSTOMER WANTS

In the long run customers get what they want. It is as true for information as it is for transport, food, or any other industry. Information is going to become free because that is what the customer wants. Customers will get all the information they want. It will be inter-connected.

And it will be integrated with the systems they want to use, whether that’s a mobile phone or lab management software. This will occur, as it has in the past, in the form of an evolution, not a revolution, as illustrated in . I’m going to discuss four of these items in more detail: non-traditional content, connectivity (i.e., linking), Open Access, and workflows.

Non-Traditional Content

The Internet allows all kinds of content to join traditional books and journals. Data sets, audio and video files, blogs, correspondence, e-mail, primary materials of all kinds—suddenly these can be studied across the academy. Unique content like archives can be made available to all.

Video is going to become increasingly important because we can do things with video online that we have never been able to do before. An avalanche of new video materials are being created every day, made possible because the cost to produce it and to distribute it has declined so much.

Historically, video has been a medium that is slow and difficult to search. You have to watch it to understand it, and watching takes time. By transcribing and fielding the content within it we can make it both searchable and allow users to digest it as quickly as they do text. This is transformative. It makes text much more persuasive and it makes video much more relevant to the academy.

Linking

Non-traditional content must be linked. In order to make sure that everyone can link to it, we must create a single database for all of our content. This presents several challenges, not least of which are not only the technical challenges that linking still presents in the form of authentication and permissions, but the philosophical opposition to making money from information. Why is there not a business model where sharing links creates financial gains? Why does Wikipedia sell mugs and t-shirts but not links from their pages to books at Amazon? Both companies would profit and the customer would get what they want: more, relevant information. There ought to be a hybrid model where the free and the fee coexist.

Alexander Street created an early example of such a model in their product Oral History Online with the aim of creating higher value links. The content of Oral Histories Online represents the personal histories of over 30,000 people. Each oral history, both those that are freely available and those that are fee-based, is semantically indexed and keyword searchable.

In the commercial world people are already charging for usage generated. The owner of a webpage that passes users to another website gets paid for doing that. Conversely, the owner of the website that is being linked to might also ask for payment in exchange for permission to link to their content.

More work on linking is needed in order to move toward a hybrid model. All websites should not be oriented toward a single discovery service. Every publisher, every library should be interlinked. If done right this will result in benefits for all parties, especially our customers.

Open Access

Does any user welcome hitting a paywall? We want our information to be free at point of access. It’s the aim of commerce profitably to meet customer needs. If that’s true and it’s true that customers want free access then surely commercial publishers will have to move to Open Access.

My company, Alexander Street, is announcing a new product called Open Music Library in an effort to support the move to Open Access and to experiment with a hybrid business model. The Open Music Library is an initiative to build the world’s most comprehensive open network of digital resources for the study of music.

It will benefit users by allowing them to find, comment, follow, share, and collaborate around the discipline. It will provide links to both free and for fee content.

Workflows

Digital Science, a sister company to Macmillan and the Nature Publishing Group is a good illustration of how workflow is simply a part of the larger process of discovery. Digital Science looked at what faculty and researchers need at each step in the process in order to enable faster, better, and more efficient scientific discoveries. Then they created a system of app-like tools to help researchers at each step. Each works with the other to create a wholly more effective process. The publishing part is only one out of nine activities. And activities like sharing, getting and measuring attention, tracking research—all lend themselves to Open Access. I believe this path—developing an entire content centric ecosystem—will generate more money for publishers than selling closed journals, and so will make Open Access a de facto standard.

CONCLUSION

Consider what the reaction might have been in 1989 to the statement that by 2015 there would be a $70 billion company that would deliver billions of pages, images, and video without charge to anyone around the globe who has a $100 device that fits in your pocket; skepticism at the very least. One might expect the publishing companies of the day to have been the likely candidates to make such a thing happen—but they were not. Most of them did not do badly—they grew at varying rates, mostly in the single digits. But as Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, and many others have shown, the opportunity was there to expand enormously. With hindsight it was clear that many of the technologies that made this possible were entirely predictable. It was a question of embracing them and working to exceed customer expectations.

In the early twentieth century the carriage industry sold off harnesses, whips, and carriage robes at discount prices as automobile sales rose and carriage equipment became obsolete. They, like the information industry, had opportunities to evolve. Those that did so became manufacturers themselves, as well as suppliers and partners to the titans of their day—the big car manufacturers. The information industry has a similar choice.

As I hope I have shown today, the information industry can expand to non-traditional content types; to building connectivity between scholars and resources; to embrace larger systems and workflows; and to Open Access models. As we move towards systems that deliver knowledge and wisdom there are plenty of actionable opportunities. Or we can reject change—stone tablets are arguably the first form of writing and someone is still selling them today on Amazon!

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Rhind-Tutt

Stephen Rhind-Tutt is president of Alexander Street Press.

Sarah W. Sutton

Sarah W. Sutton is Assistant Professor, School of Library and Information Management, Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas.

Notes

1. “Statistics,” http://www.youtube.com/yt/press/statistics.html (accessed July 9, 2015).

2. K. G. Schneider, “The User Is not Broken: A Meme Masquerading as a Manifesto,” June 3, 2006. http://freerangelibrarian.com/2006/06/03/the-user-is-not-broken-a-meme-masquerading-as-a-manifesto/ (accessed October 28, 2015).

3. G. Bellinger, D. Castro, and A. Mills, “Data, Information, Knowledge, & Wisdom,” 2004. http://www.systems-thinking.org/dikw/dikw.htm (accessed July 9, 2015).

4. Technological Forecasting (2015). http://www.innovation-portal.info/toolkits/technological-forecasting/ (accessed July 9, 2015).

5. OCLC, “The 2003 Environmental Scan: Pattern Recognition,” Dublin, OH (2003). https://www.oclc.org/reports/escan.en.html (accessed October 29, 2015).

6. Oliver Wainwright, “Louis Kahn: The Brick Whisperer,” The Guardian, February 26, 2013, sec. Art and design. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/feb/26/louis-kahn-brick-whisperer-architect (accessed October 28, 2015).

Bibliography

- Bellinger, Gene, Durval Castro, and Anthony Mills. 2004. “Data, Information, Knowledge, & Wisdom”. Systems Thinking. http://www.systems-thinking.org/dikw/dikw.htm.

- Dempsey, Lorcan, Constance Malpas, and Brian Lavoie. 2014. “Collection Directions: The Evolution of Library Collections and Collecting”. Portal: Libraries and the Academy 14 (3): 393–423. publish1-replicator. 2015. “2003 Environmental Scan: Pattern Recognition”. Accessed October 29. https://www.oclc.org/reports/escan.en.html.

- Schneider, K. G. 2006. “The User Is Not Broken: A Meme Masquerading as a Manifesto”. The Freerange Librarian. June 3. http://freerangelibrarian.com/2006/06/03/the-user-is-not-broken-a-meme-masquerading-as-a-manifesto/.

- “Statistics”. 2015. YouTube. Accessed July 9. http://www.youtube.com/yt/press/statistics.html.

- “Technological Forecasting”. 2015. Innovation Portal. http://www.innovation-portal.info/toolkits/technological-forecasting/.

- Wainwright, Oliver. 2013. “Louis Kahn: The Brick Whisperer”. The Guardian, February 26, sec. Art and design. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/feb/26/louis-kahn-brick-whisperer-architect.