ABSTRACT

Armacost Library at the University of Redlands structured the experience of an integrated library system migration to encourage agency, collaboration, and user-centeredness. Careful deliberation by library leadership and creative team-building activities enabled the library to address technological, cultural, and patron-facing changes wrought by the migration. The presenters related migration leadership to the NASIG Core Competencies for Electronic Resource Librarians and considered attributes needed to support colleagues in developing collective ownership.

Can libraries use complex projects like a systems migration to shape their organizational culture to encourage deeper collaboration, staff initiative, and team learning? Armacost Library recently explored this question during its multi-year integrated library system (ILS) migration from Innovative Interfaces Millennium to Ex Libris Alma. In this NASIG session, Paige Mann and Sanjeet Mann described how the library structured its migration to foster values of agency, collaboration, and user-centeredness, which can be called collective ownership. The presenters shared practical activities that were used with staff and related the NASIG Core Competencies for Electronic Resource Librarians to leadership attributes helpful for developing collective ownership.

Background information

Located on the traditional lands of the Serrano and Cahuilla nations, the University of Redlands is nestled in a Southern California city of 70,000 people between Los Angeles and Palm Springs. The university is a private, teaching-intensive liberal arts institution with a College of Arts & Sciences and Schools of Business, Education, and Continuing Studies. Approximately 5,000 full-time equivalent students and employees are supported by seven librarians and eight staff at the Armacost Library. The library’s mission emphasizes self-directed learning and critical pedagogy. When the library director retired in 2016, three librarians assumed interim leadership at the Provost’s request.

The library’s migration proceeded in four phases from 2015 to 2018:

During a year of strategic planning, a team identified goals for improving the library’s technology infrastructure, determined that an ILS migration was necessary, and recruited institutional support.

A team conducted several cycles of increasingly formal vendor research over a six-month period, culminating in a formal Request for Proposals (RFP), site visits by finalists, and contract negotiations with the selected partner, Ex Libris.

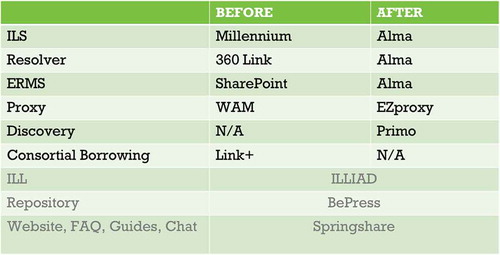

All library employees were assigned to project teams for the six-month migration phase. The library, vendors, and campus information technology (IT) staff collaborated to implement multiple systems, as seen in .

The library set up several areas of Alma, developed workflows, and assessed the effect of the migration during a year of post-migration.

Paige facilitated a migration team and was involved in two additional phases, and Sanjeet coordinated each phase of the project.

Hands-on involvement in multiple phases of the migration allowed the presenters to develop a holistic view on how system migrations affect libraries. While the library’s smaller size may have made this level of engagement possible, the presenters’ strategies for embedding collective ownership are relevant to libraries of all sizes.

Multiple dimensions of change

Systems migrations can be said to change a library in at least three dimensions: technologically, culturally, and in terms of users’ lived experiences. Technological changes such as a move to a cloud computing architecture or implementation of a new technical standard result in visible and time-consuming staff retraining. Cultural changes impact employees’ professional identities as well as the library organization’s traditions and narratives. These changes can be as drastic as migration-related personnel changes, or as subtle as the reassignment of a staff member or the creation of a new work team. Finally, migrations impact the user experience through new interfaces and changes to services offered, motivating interaction between users and library personnel.

Principles for addressing migration-related change

Libraries often struggle to cope with these dimensions of change. When Armacost Library’s leaders attended conference sessions and read articles to prepare for the migration, they were concerned by what they learned. Other libraries reported feeling frazzled by the relentless pace or were disappointed that their new system did not meet their functional requirements. Staff revealed that they felt powerless because leaders had unilaterally decided whether to migrate and to which system. Some instruction librarians resented end-user interfaces that seemed to actively undermine efforts to teach students to search critically and strategically. As the leadership team discussed their concerns, they developed a vision for how they wanted Armacost Library’s experience to be different.

Library leadership wanted to maintain the agency of faculty librarians and staff throughout the migration process, rather than having the change be driven by technology, the ILS vendor, or upper administration. Ideally, leadership would provide resources to empower front-line employees to make key decisions, and vendors would adapt their project plan and processes to fit the library’s needs. Discussing the library’s budget and negotiating with campus units for resources prepared the leadership team to compromise and collaborate for their desired system, building agency for the library and allowing the migration to go forward in the absence of additional institutional funding.

Library leadership also valued collaboration, recognizing that concepts such as shared vision and systematic thinking are crucial to everyday success at the individual and organizational level.Footnote1 This is only heightened in a systems migration, when seemingly minor details (such as values in a configuration spreadsheet) can have unexpected impact on library users and colleagues working on other areas of the library. The leadership team thought strategically about each person’s role on migration teams and developed ground rules to promote constructive interaction among team members.

Library leadership understood the principle of user-centeredness in terms of the library’s bottom line—to support campus teaching and learning. To this end, the vendor research team emphasized the user interface in their RFP and vendor demonstrations, and instruction librarians evaluated how well finalist discovery services facilitated tasks implicit in the Association of College & Research Libraries’s Framework for Information Literacy. The leadership team developed this principle through big picture discussions of how to support students and faculty and how to make their library a workplace where colleagues contributed to each other’s success.

Empathy is a necessary attribute for all involved in a systems migration. Migrating to a new system creates a lot of unknowns. As colleagues lose their expertise in the outgoing system, they may feel their authority and status in the library being stripped away. Uncertain of their place in their transitioning library, self-esteem may suffer along with a sense of safety amongst one’s co-workers.Footnote2,Footnote3,Footnote4,Footnote5

To minimize threats inherent to systems migrations, there are a few key strategies to implement: colleagues must be involved in decisions, must have meaningful responsibilities in the migration, and must be informed to reduce uncertainty and increase predictability.Footnote6,Footnote7 When employees display resistance to change, it may be a sign that leadership needs to provide additional support, rather than simply a reaction that threatens the migration project. The work of educator Eric Toshalis may be useful reading for migration managers seeking constructive responses to resistance from colleagues.Footnote8

Embedding values in the migration infrastructure

To foster success at the library, team, and individual levels, library leadership structured teams in ways that reduced silos and promoted teamwork and innovation. Three migration teams were created to focus on public services, technical services, and instruction. Recognizing the collective expertise distributed throughout the library, everyone was assigned to at least one team, and those assigned to multiple teams served as bridges of communication. These bridges were reinforced by ensuring that these team liaisons always had at least one other person serving in the same capacity. This was intended to both strengthen cross-team communication and reduce the pressures felt by any one person.

Each team was comprised of insiders and outsiders balancing day-to-day expertise with fresh perspectives, questions, and ideas. For example, the public services team included Access Services employees and a few employees outside the department. Outsiders were assigned to facilitate teams, and because these facilitators had no voting rights in team decisions, they were positioned to help teams figure out what they wanted, lead themselves, and weigh what was best for the library and its users. To foster learning of the new system and team engagement, facilitators and leaders emphasized the equal footing that everyone had in the process: no one knew more, no one knew better, we were all learning together, and we were all learning at the same time. The truth of these statements was not immediately apparent to everyone, but became more evident over time, encouraging more participation in team decisions.

To document team discussions and decisions, ensure transparency, and hold teams accountable to themselves and each other, meeting agendas and minutes were regularly updated to a shared server in the cloud. This enabled everyone in the library to easily access these documents at any time and helped project leaders use this information to configure the system.

Embedding values in the team infrastructure

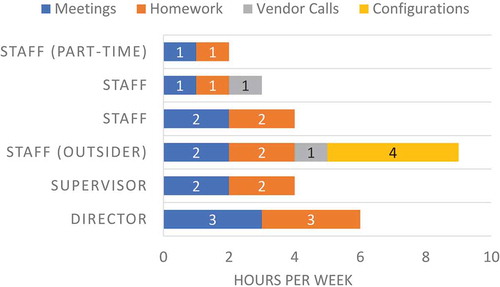

Building off the people-centered foundations at the library level, the team focused on public services operated on the principles that we each have something to contribute, that fear and anxiety are normal, that change is difficult, and as a result we all need to support one another and give each other room to make mistakes. To engender trust and cooperation, substantial effort also went into making visible what would otherwise be hidden. In one example, estimates of everyone’s weekly time commitments as they related to the migration were shared with the team. Time spent in meetings, on homework, on calls with the vendor, and work on system configurations were accounted for, as seen in . This helped team members see and compare burdens placed on part-timers, full-timers, insiders, outsiders, supervisors, and supervisees.

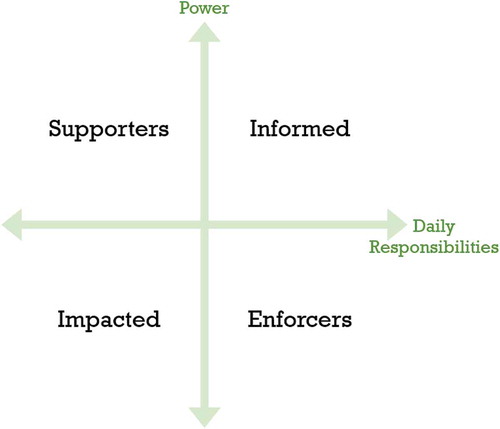

Another example involved an activity that asked everyone to take a moment to first think about the power, or lack thereof, they felt within the context of their university. Second, they were asked to think about the frequency with which they would work with the new system. Third, they were asked to plot themselves on a shared graph where the x-axis represented frequency of use, and the y-axis represented perceived power as seen in . Team members were then asked to plot other groups like IT, students, student workers, and other migration teams. This team then discussed how to rearrange everyone to accurately represent their positions and relations to one another.

This process helped the team develop a shared understanding that those who work most often with the system and its related policies were well positioned to inform team discussions regardless of their title or position at the university. In contrast, those with power (e.g., supervisors, leadership) who work less frequently with the system and related policies were positioned to support the contributions of the first group. Additionally, the team had to consider how their decisions affected others like student workers who had to enforce system decisions and policies, and students whose learning and research would be impacted by system decisions and policies. This helped clarify everyone’s roles, responsibilities, and the justifications behind them.

Another activity asked team members to periodically rate how confident they felt completing tasks they had recently learned. Responses were aggregated and shared as seen in . This clearly demonstrated that the team was not split between those who were and were not confident, but rather that confidence levels varied across a spectrum.

To maximize learning and help the team focus on its main objectives, meeting agendas were made consistent and predictable (see Appendix 2). While this offered immediate benefits, team members could also use this when later tasked with facilitating a meeting in their area of recently developed expertise. Agendas were distributed one week in advance and included the following elements: time and location of meeting, time allotted for each agenda item, person responsible for taking minutes, and that week’s homework assignment. Agendas also established a rhythm so that the team learned from and responded to team liaison reports, discussed and revised ground rules (see Appendix 3), and participated in opening and closing exercises.

The opening and closing activities used by this team were scripts written into each agenda that everyone had to follow regardless of how uncomfortable it made them. These scripts required colleagues to explicitly share their feelings with, ask for help from, and encourage one another. Although the activity was imposed, the sentiments shared were genuine, at times humorous, and well received. Aware of the difficulties ahead, the team facilitator chose to push the team past their comfort levels to find words to support one another.

Finding collective ownership in the NASIG Core Competencies

This project team’s refusal to settle for what was comfortable and familiar was necessary because collective ownership requires continuous and collaborative learning, backed up by institutional support for professional development. One of NASIG’s best known professional development resources, the Core Competencies for Electronic Resource Librarians, speaks to the change management principles needed for collective ownership.Footnote9

Maintaining agency in a systems migration requires the ability to manage projects (competency 5.2) and time (7.4), evaluate vendor products (3.6) and their utility (5.6), understand technology (2), and communicate persuasively by selecting appropriate evidence (3.8) and by framing one’s arguments (4.5).

Building a culture of collaboration entails effective working relationships (4.4, 5.5); skills in supervision, training, and motivation (5.1), and the ability to communicate with a broad audience inside and outside the library (4.1).

While few Core Competencies speak directly to user-centeredness, traces of this mindset can be found in personal attributes describing “dogged persistence in support of users” (7.3), flexibility and open-mindedness (7.1), and communication that “rise[s] above personal frustrations to provide the best possible services” (4.3).Footnote10

Lessons for libraries

Even with the best possible professional development, learning is still inefficient, iterative, and time-consuming, for organizations as well as for individuals. Our reaction to disappointing outcomes matters. What if we regarded unsuccessful projects with patience, as part of a longer narrative of learning that will ultimately strengthen us? What if we designed processes and workflows to establish high expectations while offering safe places to fail and learn? Armacost Library’s migration included some lower-stakes opportunities to practice upcoming challenges in miniature. For example, the replacement of an expiring server during the vendor research phase taught library leaders how to find room in the budget for a significant technology purchase and gave IT and library employees a preview of what it would be like to work together during the migration phase.

Library leaders should structure processes so that they are not making big migration decisions on their own. In Armacost Library’s project, the systems team evaluated vendors and decided on a first choice with input from other library employees. The leadership team developed the migration project structure and brainstormed concessions to offer during contract negotiations. Important sections of the migration and configuration forms went to project teams for a vote. This resulted not only in stronger buy-in but also better decisions.

Leaders also need to be aware of their own limitations and need for continued learning. Colleagues with complementary strengths can provide trusted advice and fill key roles. Those with stronger facilitation skills may facilitate migration teams; those with strong communication skills or a willingness to learn outside their own department may serve as team liaisons. Readers who want to learn more can consult Appendix 1 for a list of additional resources.

Pursuing collective ownership in libraries is not easy. When we wonder whether it is worth the effort, it may help to consider this quote from Candise Branum and Turner Maslund:

Library managers … have a high level of visibility. And we have the opportunity to set policy and influence organizational culture. By moving toward a more just management practice we will move toward more just libraries and hopefully will contribute to the creation of more just communities.Footnote11

Collective ownership is not just an effective way to coordinate and complete a migration. Collective ownership requires that all involved acknowledge the profound impact change can have on individuals and organizations, and structure themselves to contribute to one another’s success in concrete ways. To do this brings us one step closer to just libraries and hopefully a more just society.

Acknowledgments

A big thanks to our colleagues at University of Redlands: Debbie Alban, Shariq Ahmed, Trisha Aurelio, Les Canterbury, Rebecca Clayton, Gerald Collins, Emily Croft, Alton Edenfield, Lua Gregory, Gary Gonzales, Shana Higgins, Corrinne Howell, Janelle Julagay, Bill Kennedy, Chris Kincaid, Susan LaRose, Todd Logan, Eugenia Livingston, Jessica Macias, Tim Morris, Cory Nomura, Kathy Ogren, and Sandi Richey. We did it!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paige Mann

Paige Mann is STEM Librarian and Scholarly Communications Librarian, University of Redlands, Redlands, California.

Sanjeet Mann

Sanjeet Mann is Arts & Systems Librarian, University of Redlands, Redlands, California.

Notes

1. Becky Schreiber and John Schreiber, Leading from Any Position: Improving Library Effectiveness and Responsiveness (workshop, Pomona, CA, December 5–6, 2011).

2. Ann-Marie K. Baronas and Meryl Reis Louis, “Restoring a Sense of Control During Implementation: How User Involvement Leads to System Acceptance,” MIS Quarterly 12, no. 1 (March 1988): 112.

3. Annette Day and Carol Ou, “Determining Organizational Readiness for an ILS Migration—A Strategic Approach,” College & Undergraduate Libraries 24, no. 1 (2017): 106.

4. Michael Dula, Lynne Jacobsen, Tyler Ferguson, and Rob Ross, “Implementing a New Cloud Computing Library Management Service: A Symbiotic Approach,” Computers in Libraries 32 (January/February 2012): 9.

5. Richard M. Jost, Selecting and Implementing an Integrated Library System: The Most Important Decision You Will Ever Make (Waltham, MA: Chandos Publishing, 2016), 41–42.

6. Shea-Tinn Yeh and Zhiping Walter, “Critical Success Factors for Integrated Library System Implementations in Academic Libraries: A Qualitative Study,” Information Technology and Libraries 35, no. 3 (2016): 33–34.

7. Baronas and Louis, “Sense of Control.” When evaluating system options, it’s useful to consider how well a vendor provides both updated and well-organized documentation. Such material will make it easier for colleagues and leaders to develop expertise in the new system, anticipate next steps, engage in decision making, and support each other’s learning.

8. Eric Toshalis, Make Me! Understanding and Engaging Student Resistance in School (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2015).

9. Core Competencies Task Force, “NASIG Core Competencies for Electronic Resource Librarians,” NASIG, http://www.nasig.org/site_page.cfm?pk_association_webpage_menu=310&pk_association_webpage=7802 (last modified January 26, 2016, accessed June 7, 2018).

10. Core Competencies Task Force, “NASIG Core Competencies.”

11. Candice Branum and Turner Maslund, “Critical Library Management: Administrating for Equity,” OLA Quarterly 23, no. 2 (2017): 30.

Appendix 1.

Additional Resources

Bregman, Emily, and Andrea Kappler. New Supervisors in Technical Services: A Management Guide Using Checklists. Chicago: American Library Association, 2007.

Gray, Dave, Sunni Brown, and James Macanufo. Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 2010.

Mitchell, R., B. Agile, and D. Wood, “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts,” Academy of Management Review 22, no. 4 (1997): 853–886.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Introduction to Planning and Facilitating Effective Meetings.” Accessed May 2, 2018. Retrieved from https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/effective-meetings.pdf

Richardson, Martin. The People Management Clinic: Answers to Your Most Frequently Asked Questions. London: Thorogood Publishing, 2006. EBSCOhost.

Sibbet, David. Visual Meetings: How Graphics, Sticky Notes & Idea Mapping can Transform Group Productivity. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Appendix 2.

Sample Agenda

Fulfillment Essentials, Part 2

March 16, 2017, 3-4pm in the CILLab

Esteemed Minute-Taker: Joseph

Homework:

FUSE Co-Leadership Worksheet

Harold: Bring 9 copies of your completed FUSE Co-Leadership Worksheet to share with the team.

Everyone: (No one knows everything, together we know a lot.) Be prepared to support co-leaders by sharing your ideas, questions, and concerns.

Appendix 3.

Ground Rules

One diva, one mic

No one knows everything, together we know a lot

Both speak up AND listen to others

We can’t be articulate all the time

Be aware of time

Be curious

Aim for consensus, majority vote when necessary

Minute takers record the multiple “whys” behind votes and opinions Consult with ARM/Primo on discussions/votes that impact all staff

(**DRAFT**) Be mindful and self-reflective about how teammates might receive our verbal and non-verbal actions (e.g. yawning)