Once we were walking down a road and we saw a little Ghanaian boy. He was running and happy in the happy sunshine. My husband made a comment springing from an argument we had had the night before that lasted until four in the morning… He said, “Now look, see that little boy. That is a perfect picture of happy youth. So if you were writing a poem about him, why couldn’t you just let it go at that?” …

So I said if you wrote exhaustively about running boy and you noticed that the boy was black, you would have to go further than a celebration of blissful youth. You just might consider that when a black boy runs, maybe not in Ghana, but perhaps on the Chicago South Side, you’d have to remember a certain friend of my daughter’s in high school—beautiful boy, so smart, one of the honor students, and just an all-around fine fellow. He was running down an alley with a friend of his, just running and a policeman said: “Halt!” And before he could slow up his steps, he just shot him. Now that happens all the time in Chicago. There was all that promise in a little crumpled heap. Dead forever. (Brooks, as cited in Hull et al., Citation1977, pp. 25–26)

Lest our dreams reflect the death of theirs. This is for us, at once before and after, seeking another kind of now. (Gumbs, Citation2010, p. 1)

When and Where We Enter into Curriculum StudiesFootnote1

Esther: Justin, this special issue sprung from one critical question: how could we creatively and intellectually interfere with curriculum studies’ faithful marriage to anti-Blackness? I will return to that essential question and begin addressing how the issue’s contributors engaged it momentarily. However, as a preface to my response, I will tell you a story about when and where I entered this very white field. I theorize through this narrative (Christian, Citation1988) to illustrate that I was drawn to the possibility of this special issue because—invoking the womanist gospel of our ancestor and Queen Mother, Toni Morrison (Citation1990; see also Le Fustec, Citation2011)—I wanted to freely imagine what curriculum studies could be with the white gaze and the field’s narcissistic love of whiteness parenthesized. So, I embarked upon this collaborative project wondering how we could co-create something that would “go further than a celebration of” the optic inclusion and infusion of Blackness in curriculum studies (Hull et al., Citation1977, p. 25).

My path to curriculum theorizing was sinuous in the sense that for the entire period I was a doctoral student, I did not feel a sense of belonging in this lily-white field. However, I did feel drawn to the questions about knowledge that curriculum theorists foreground and to the creative methods those of us at the margins of curriculum studies often use to produce that knowledge—here, I mean creative in relation to the poetics, aesthetics, aurality, and orality inherent in BlackFootnote2 cultural production. I completed graduate study by defending a dissertation that is, epistemologically at least, a hodgepodge of things—some, in retrospect, quite ill-suited for the inquiry undertaken. In any event, I navigated the academic job market with this dissertation in hand, eventually landing a campus interview at my current institution, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Carolina). I was astounded to be a finalist for a position that Grumet (Citation1988; Citation1989), a foundational figure in the field, was vacating. Grumet and Pinar are among those heralded as “giants” for their significant role in midwifing the curriculum studies’ reconceptualist era (Pinar, Citation2019; Pinar & Grumet, Citation2014), so perhaps I should have anticipated my imposter syndrome kicking into high gear. Yet something unexpected happened when I toured the university’s campus for the first time.

My visit to Carolina coincided with the intensification of protests to remove the confederate Silent Sam statue from campus (Deconto & Blinder, Citation2018). As such, I experienced the entanglement of anti-Blackness, race(ism), place, and knowledge production in a visceral and embodied way; I experienced it on a corporeal register. This moved me to begin imagining how I could conduct research, teach, and write as a Black woman curricularist while ensnared within that entanglement (Baszile et al., Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2018). I share that as context for my narrative, which is really one of becoming known—if only to myself—as a curriculum theorist. So without further ado, here is my brief interlude of a story, which started as a journal entry that I wrote at the end of the day described in the vignette:

The palpable presence of Black death permeates this haunted southern place (Reynolds, Citation2014). The resident ghosts are hostile as they gather. Gleefully, they encircle my body, latch onto my skin. “It stinks of slavery,” I say to my husband. I am ambling through the campus of one of the many universities in the southern United States where the unmarked graves of enslaved persons are located (McClellan, Citation2020). The morning is young. I glance around to ensure the absence of white people within earshot, then whisper into my phone, “I’m tellin’ you, it smells like slavery here.” I pause, then add, “Maybe that’s why they call this place the Dirty South—you know, the Dirty Dirty.” My husband is on the receiving end of the phone call, keeping me company as I meander. He is a perspicacious partner who often humors my dark humor. “Seriously?” he says somberly. “That’s not funny.”

Hours later, in the middle of a long day filled with all of the typical blah blah blah that comes along with multi-day job interviews at universities like this, I am parched, as if an overstuffed bale of hand-picked cotton has been forced in my mouth, absorbing all moisture. I reach into my oversized tote bag to search for the water bottle that I swiped from the lobby of The Carolina Inn. My fingers graze the plastic bottle just as I sink into a chair. A sigh of relief escapes my dry lips as wetness begins to dampen my cheeks. I am on campus still, sitting in a room not far from Madeleine Grumet’s old office. She is retiring soon, and I am replaying what I am convinced was a disastrous job talk about my research to a room full of people who will soon bid her adieu, reconceptualizing everything I thought I knew about curriculum theory. I want to think that I am confident in my knowledge of curriculum theory. I want to think that I earned my stripes as a graduate student in the Curriculum and Teaching program at Teachers College, Columbia University; that the years I spent greeting the sculpted bust of John Dewey displayed in the College’s ever-busy lobby meant something here, now, in this moment. Perhaps I should have devoted time to Dewey in my job talk, I think ruefully. I named neither Dewey nor the many other curriculum (capital T) Theorists who I discovered in graduate school—most of whom are male denizens. I did name Anzaldúa (Citation2015), Moraga and Anzaldúa (Citation2015), Christian (Citation1988), Collins (Citation2009), Dillard (Citation2007, Citation2012), hooks (Citation1996), Moten (Citation2018), Philip and Boateng (Citation2011), Sharpe (Citation2010, Citation2016), Spillers (Citation1987; see also, Pryse & Spillers, 1985), Wynter (Citation2003, Citation2010), and several others whose scholarship shape my knowledge of knowledge. I did so because, well,

It was not that [I] did not appreciate the many other readings I was doing in graduate school—Freire, Foucault, Dewey, Derrida, and many others—they were informative, thoughtful, critical, but simply could not compare to what it was like reading a language [I] actually understood and lived with and through daily. (Baszile et al., Citation2016, p. 148)

Between big gulps of water, I try to recall what I said during the dread-full question-and-answer session following my job talk. At that point, my thinking was clouded and my speech jumbled and incomprehensible—or at least, that’s what I thought. At this point, laughter is the farthest thing from my mouth and my mind is focused on a single question: am I a curriculum theorist? All I feel is dejection. I wonder if all those (white) people in that conference room not far from Madeleine Grumet’s office saw my Black being and heard my Black thoughts about (my) Black life and could not see how someone who had lived as I had and thought like I think could be, well, a thinker. If they do not see me as a thinker, then they cannot see me as a person―that is, a human. Therefore, at this point, as lukewarm water trickles down my throat, what I am really pondering is, can the subhuman think? What I mean to say is, in white thought, can the subhuman be a theorist?

Justin, I offer that tale as a preface to articulating the two-pronged intervention that I hope this special issue makes, which is first, to surface and respond to how little discussion of whiteness happens in the field of curriculum studies (Desai, Citation2012; Gaztambide-Fernández, Citation2006; He et al., Citation2015), and second, to invite the field to more meaningfully engage the knowledge that whiteness, white supremacy, and anti-Blackness are entwined; furthermore, “anti-black racism is the fulcrum of white supremacy” (Nakagawa, Citation2012). This special issue, then, is an effort to turn the compass to critical Black studies (Brock et al., Citation2016; Rabaka, Citation2009). So, this is when and where I enter the two projects that we are discussing here: curriculum studies and this special issue. How about you?

Justin: My entry point into this special issue and the larger project of curriculum studies is best framed through a series of questions that have infiltrated my mind, perhaps as far back to second grade when my teacher, a white woman, informed my parents of her intention to recommend me for what Fitzgerald (Citation2009) referred to as “the Black prison called special education.” I was not in need of special education services. On the contrary, I needed the exact opposite, characterized by me being enrolled in the district’s Gifted and Academically Talented services after completing the standard series of assessments with the district psychologist. So, when I listen to you detail your relationship with un/belonging in this white field, and as I reflect on the multitude of ways the whiteness of curriculum and curricular spaces at every educational level (including the educators who oversee these spaces) have been antagonistic to my Blackness, I keep trying to answer—well think through rather—a series of questions. As a Black person in this world, characterized by global anti-Blackness, what does it mean to be counted, what does it mean to be visible, what does it mean to be seen? And, in an Ellison (Citation1995) sense, this is an age-old question interrogating the in/visibility politics of the Black. Leaning into such politics, I am transported to 1851 when Isabella Baumfree, whom we know as Sojourner Truth, shared: “I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me” (McKissack & McKissack, Citation1994, p. 114). Why was Sojourner’s suffering ignored, and, more so, why was her Black woman suffering even in existence, particularly as a national necessity? I think about Wilderson (Citation2017) discussing the necessity of Black suffering for this nation-state’s functioning. Wilderson (Citation2017) noted that the United States, as we know it, would cease to exist if anti-Blackness disappeared. When we cry out, who is there to hear our grief, more so, does Black grief even register on the scales of humanity? Our contemporary socio-political moment of Black (up)rising, where I see daily calls for the cop(s) who murdered Breonna Taylor to be arrested, evokes the words of Smith (Citation2017): “i reach for black folks & touch only air. your master magic trick, America. now he’s breathing, now he don’t” (p. 25). Breonna, our Black Sleeping Beauty, I am so terribly sorry that your slumber was halted by bullets instead of kisses from your true love. Just as Sojourner, as a Black woman, I know that you, Breonna, have had your entire existence made invisible. Even in death, how is it that the total climate in which we exist is so deeply anti-Black, that Breonna, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, still are not counted?

What does it mean to have one’s life—lived experiences, culture, body, etc.—understood and imaged as meaningful, on their own terms? Living on lands where “the laws of slavery subjected the enslaved to the absolute control and authority of any and every member of the dominant race” (Hartman, Citation1997, p. 24), how might my Black life be seen as a necessity for the ways that we all, Black and non-Black people, make sense of a collective lived experience? How does my Black life and the Black lives of others move from invisibility to becoming rendered as both worthy and crucial? Why does this shift matter for me, you Esther, and all of humanity? In “Trading Spaces: Antiblackness and Reflections on Black Education Futures,” an article I recently published with Warren (Warren & Coles, Citation2020), we mediated on the fungibility of Black lives that was depicted in Bell’s (Citation1992) short story “The Space Traders.” In Bell’s story, briefly summarized, humanlike beings from outer space come to the United States and offer to provide the nation-state with unlimited natural resources in exchange for the African American population. The U.S. governing bodies decide to engage in the trade, demonstrating the ways Black people have been commodified and understood through the logics of racial capitalism. Here, Black life was not seen as a contributing factor to world-making, the pulse of the nation, but rather Black life was reduced to what Césaire (Hord & Lee, Citation2016) referred to as “thingification,” characterized through their disposability. While Bell’s story is often read as an anti-Black tragedy, evoking the context of chattel slavery where Blacks were exchanged as/for goods, Chezare and I instead theorized this exchange as a tale of Black liberation. We surmised that, perhaps, the “creatures negotiating the trade were the black ancestral architects of black futures free from racial impunity, and the perennial pain and suffering characteristic of black life in the U.S.” (Warren & Coles, Citation2020, p. 2). Reflecting on that work and the central question driving this special issue—that is, “how could we creatively and intellectually interfere with curriculum studies’ faithful marriage to anti-Blackness?”—I understand the Black ancestral architects as catalyzing an interference with the nation-state’s kinship to anti-Blackness. In other words, if Wilderson (Citation2017) was correct, despite the creatures giving the United States unlimited resources, perhaps then, once the Black population left, the nation-state self-destructed. Inspired by the potential pandemonium that ensued as a result of this Black interference by The Space Traders, I wonder, how might we creatively and intellectually interfere with curriculum studies’ faithful marriage to anti-Blackness utilizing critical Black curriculum studies?

I am reminded of Hughes’ (Citation1926) poem “I, Too,” where the narrator has been relegated to eating in the kitchen, but spends this time eating well and growing strong. After time passes, the narrator understands that everyone will be ashamed for treating them like less-than-human, when they realize how truly beautifully human they are. This is the embodied interference necessary in this sociopolitical moment and the next moment of curriculum studies (Desai, Citation2012; Malewski, Citation2009), and I think we start to accomplish this with this special issue. It is also funny, because as we think about the necessary pivot towards critical Black studies, I keep wondering, is curriculum studies even deserving of the expansive beauty, life, and theoretical richness in which critical Black curriculum studies is situated? But then, I have come to know that this is exactly why a turn in this direction is necessary. Blackness can transform curriculum theorizing in a way that is neither as marginalizing nor as violent as Eurocentric orientations toward curriculum are with regard to Black humanity.

When I think about our proposal to utilize critical Black studies as a curriculum studies imperative, I also think about the myriad texts and textures of Black life that have informed my existence in/of being, so much so that this catalog, if you will, of Black life is embodied within me. The Black embodiment I refer to here is not merely an intellectual metaphor, but both historically genealogical and spiritual. Marable (Citation2006) referred to this embodiment or preservation and honoring of the Black past as a pathway to the future, as living Black history. However, given the function and reach of whiteness, I am begrudgingly reminded about the systemic ways my life, my body, serving as a cupboard of Black life or what scholar Kirkland (Citation2017) referred to as Black (textual) life, has been imaged across time and space as innately the antithesis to the all-white world of curriculum studies. This brings me to my entry point into curriculum studies, my experience of quite literally feeling like my Black boyhood was not digestible in curricular spaces and that Black people largely could not be producers or influencers of curriculum. I gained insights on the ways Blackness was positioned as indigestible to curriculum through the overabundance of white teachers, which implicitly signaled to me that Black people cannot be disseminators of knowledge as they are counter (to) curriculum, and through the ways my predominantly Black schools were considered to be inherently anti-intellectual. The whiteness of curriculum led me to think that I—Blackness personified—was out of touch with or outside curriculum. I was schooled in this logic, the idea that Blackness and Black people are outsiders on intellectual matters. That logic is an ideological tool of white supremacy. Unfortunately, curriculum studies are tethered to such ideological falsehoods, which must be disrupted. Now.

Towards Critical Black Curriculum Studies

Esther: Justin, so much of what you shared resonates and connects to the content of this special issue, which reflects an incredible range of Black knowledge and wisdom firmly planted in the fertile grounds of Black intellectual traditions (Gordon, Citation2010). How the topics addressed are brought into focus—the diverse theories, methodologies, and methods employed—remind me, us, that Black people know what Blackness is, even as we study it, and even if it is also true that “‘blackness’ can be conjured in a myriad of curious ways” and “there remains a conceptual confusion around this term which deserves more attention than it is currently given” (Olaloku-Teriba, Citation2018, p. 98). Black people know Blackness intuitively on an existential level, perhaps. My hope is that this special issue ushers in a critical Black curriculum studies that is both “undisciplined” (Sharpe, Citation2016, p. 13) and unequivocally rooted in the understanding that

it is no longer acceptable merely to imagine us and imagine for us. We have always been imagining ourselves…. We are the subjects of our own narrative, witnesses to and participants in our own experience, and, in no way coincidentally, in the experiences of those with whom we have come in contact. We are not, in fact, “other”. We are choices. And to read [work] by and about us is to choose to examine centers of the self. (Morrison, Citation1988)

Justin: I am glad that in this special issue we have decided to make that choice, choosing ourselves, choosing Blackness. Through our orientation towards Black specificity (Wynter, Citation1989) where we are intentionally carving out space and demanding space for critical Black curriculum studies, I feel us breaching a necessary rupturing to the whiteness of curriculum studies. I would say that Black people have always possessed a standpoint epistemology rooted in what we refer to here as critical Black curriculum studies, a necessity for their social and educational livelihood and survivance (Vizenor, Citation2008). In other words, Black folks are aware of the ways schooling is used as a tool of suppression and yet have always broken that barrier and re/oriented or re/engaged schooling as a means to liberation (Ayers & Quinn, Citation2008; Rickford, Citation2016; Williams, Citation2007) on their own terms. As I write this, I am thinking of Sherell McArthur, a Black woman academic who documented her journey of providing supplementary curriculum to her son during the COVID-19 crisis on Facebook. McArthur referred to this Black-led and Black-centric schooling space as “The Village School,” taking the extra time at home as an opportunity to provide her son with all of the meaningful information he may not receive in a traditional, Eurocentric curriculum. Outside of this example and many others I could offer here, I think Black folks re/making curriculum and curricular spaces has looked like everything from Black kids showing up to school as their authentic selves in the face of policies that demonize their movement styles and Black aesthetics (e.g., banning certain hairstyles) to Black students advocating for better schooling conditions and suing the state for inadequate education (e.g., Gary B. v. Snyder). In the face of white people, throughout history, fiercely guarding and upholding the whiteness of curriculum, Black communities have remained steadfast. Let’s remember that in the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education I, the Ku Klux Klan experienced a revival, the White Citizen’s Council was founded, and the movie Birth of a Nation reappeared in many local theaters. Many localities and states attempted to convert their public schools into private schools since race could be used as criteria for admission, without violating the Supreme Court decision against the practice in public schools (Church & Sedlak, Citation1976). A moment in time after Brown I that always demonstrates the ways traditional curriculum is reserved for whites, exclusively, is when Prince Edward County in Virginia shut down its public school system for four years (1959-1964) in order to avoid complying with the federal courts, which would allow Black students to attend (Church & Sedlak, Citation1976). Therefore, I would venture to say that critical Black curriculum studies are codified into the souls of Black folks. I think the articles here help us become better attuned to the expansive nature of critical Black curriculum studies and what it can look like.

Esther: As we shift to synthesizing the scholarship in this special issue, I want to begin by framing “Feeling Safe from the Storm of Anti-Blackness: Black Affective Networks and the Im/possibility of Safe Classroom Spaces in Predominantly White Institutions,” which is the article that Keffrelyn Brown and I co-authored. It was a treat to collaborate with someone whose work I encountered in graduate school. I had been nerding out on her scholarship for a while—hearing the Blackness in her writing, listening to its familiarity, and basking in its warmth. So, I was delighted when over the course of this collaboration, I learned that she is just as Black and warm in the flesh. I am highlighting our collaboration to annotate that the collaborative spaces opened up by this special issue have been invigorating both interpersonally and intellectually.

Theorizing and writing with Keffrelyn also helped me crystallize why I seek out Black women mentors in academia. I grew up in Kenya, a Black space, a Black world, really—a world where in the day-to-day, whiteness was an afterthought, if a thought at all. White people may as well have been unicorns in my world, although not ghosts, because in that world, even the ghosts—vizuka—were Black. As such, the knowledge that Blackness is inherently diverse and always plural was the natural order of things. This knowledge caused much dissonance when I immigrated to the United States because I could not grasp how or why anyone could reduce Blackness to a singular thing; the very notion was nonsensical to me. I remember once saying that for me, the concept of “African woman” is both meaningful and vacuous. I have lived in this country since I was 13 years old; in terms of the day-to-day, I now likely have more in common with an African American sis—say, a Black Brooklynite sister—than a Black Kenyan dada in Nairobi. Yes, we are all affixed to Blackness, and dare I say, diasporic Africanness; yet the differences in our ways of being and knowing are varied, vast, and nuanced. Hence, circling back to the articles in this special issue, I am thrilled by the complexity of Black being and knowing surfaced. The issue is a special reminder of the lyrical aesthetics of Black writing, the marvelous heterogeneity of Black theorizing, and the freestylin’ of Black Thought—yes, I do mean that as a pun (Reeves, Citation2017).

Also, I must say that working with you on this special issue has been a joy, particularly as spring of 2020 turned to summer, and we found ourselves drowning in the pits of so much Black pain in the aftermath of the state-sanctioned murders of Ahmad Arbery, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. As someone whose introduction to the scorch of whiteness in the day-to-day was in Minnesota (Ohito, Citation2016), bearing witness to Floyd’s murder and the mourning that ensued was incredibly painful. Each murder was an embodied and emplaced reminder of the heaviness of lived Blackness in an anti-Black world. I am tired of being Black here, Justin. Here, all

I want to [do is] mourn individual niggas. It feels too enormous a task to mourn so many at once. It bears the weight of a thousand tears. A hundred shouts. I am losing my sense of life and the barrier between living and dying seems to be weakening before and behind me. I expect to share my own hashtag soon. Never being able to bury those of us who die the unnatural death it takes to become a hashtag is robbing me of my sense of individuality.

Old grief writes and protests and screams and becomes bitter and becomes a problem. Old grief struggles to get to work on time. Old grief takes a skateboard to a pig’s windshield. Old grief never dies. Old grief becomes less easy to recall but easier to feel. Old grief recesses into my bones. (Neloms, Citation2020, para. 7-8)

I am tired of mourning Black boys like Myles Frazier, whom I had the pleasure of teaching on Chicago’s South Side at what was then named Pershing West School (Behm, Citation2019)—beautiful boys, so smart, and just all-around fine fellows. I am tired of seeing all that promise crumpled into little heaps. Dead forever (Brooks, as cited in Hull et al., Citation1977, pp. 25-26).

All of these stories are piling on top of each other. They’re not isolated. There are no individuals. I can’t keep isolating them. They can’t keep isolating me. There is a living memory of a nigga being tricked or killed or robbed or raped in every place I go. There is a living memory of genocide … There is a future memory of me being without a home. There is a future memory of me being fingerprinted and booked. There is a future memory of my vigil. (Neloms, Citation2020, para. 12)

I’m tired of this relentless grief, Justin, and as a Black person in the United States, I fear that there’s no escaping its reach. I am tired of being tired.

I am afraid that my children will inherit this old grief. I am afraid of what that will mean for the world. It is already etched into the palms of my hands. I feel it on my skin like a fine grade of dust. I feel it most in my stomach. I feel it most in my aching muscles. I feel it most in my lungs. I feel it most when I am thinking of the future. (Neloms, Citation2020, para. 9)

I am afraid and tired. So I am grateful to have sourced joy from the process of pulling together this special issue. In many ways, the articles here are reminders that much of our wisdom and knowledge as Black people has been and continues to be invisibilized and ignored.Footnote3 For instance, the article Keffrelyn and I co-authored explores emotional knowledge (Guthrie, Citation2016) in U.S. higher education while critiquing anti-Blackness in white affect studies (Dernikos et al., Citation2020). It is troubling that only recently did literature in white affect studies (Cromby & Willis, Citation2016; Garcia-Rojas, Citation2017; Palmer, Citation2017) begin showing scholars in that lineage endeavoring to “discuss their efforts to trust embodied, affectively-invested [knowledge], accessed through their own personal and/or professional vulnerability” (Conte, Citation2020, p. 2). I am astounded by the extent to which these scholars ignore Black knowledge and knowledge producers when arriving at conclusions such as, “the more we are aware of affect in our lives, our work, and our fieldwork experiences, the more affective sensitivity we can pass along to our students and our colleagues, (re) inscribing these nuances into the culture of our academic field” (p. 3). How long have Black theoreticians known and argued for this? Let me be blunt: such (white) ignorance is emblematic of epistemic anti-Black violence. Black people have been trusting our “personal and/or professional vulnerability”—and our embodied knowledge, more broadly—since before knowledge was canonized in the west and held hostage by whiteness (Ohito, Citation2020). Put differently, we been known that! Further, we been said that, fifty ‘leven different ways, in fact. Ours is also a long history of engaging this knowledge methodologically by, for example, employing dialogue as a site for meaning-making in the Black feminist tradition (Collins, Citation2009). For all time, Black people have produced knowledge using our hands and legs and more—that is, our bodies and minds; we have painted, danced, written, spoken, sung, and rapped our theory/ies (Morrison, as cited in Stella Adler Studio of Acting, Citation2016). Black people have and continue to create knowledge all the time! Even here and now, you and I are using Black oral storytelling traditions to talk about how we created something whilst producing knowledge through polyvocal dialogic writing that puts our thoughts in conversation with those of our ancestors, elders, siblings, and other intellectual thought partners. Breathing life to an each-one-teach-one credo, we are modeling what has been taught to us and scaffolding others’ learning by writing an improvised makeshift syllabus for an imagined or dream(y) critical Black curriculum studies class. Can you imagine a class where the objective is for faculty and students come to know that improvising in teaching, in learning, “in strife, in surviving, is a fugitive, liberatory move of self-determination and self-possession” (Sierschynski, Citation2020, p. 432)?

The imbrication of Blackness, space, place, and politics that you discussed in reference to Bell (Citation1992) is foregrounded in George Sefa Dei’s foreword, “Reflecting on Anti-Blackness and Anti-Black Racism.” Our elder sets the stage for the special issue by highlighting the globality of both Blackness and anti-Black racism while illuminating the latter’s particular manifestations in Canada as contextualized by the current Black Lives Matter mo(ve)ment.

Space appears again as a theme in my co-authored article which illustrates how Black faculty and students create perceptual Black spaces that are nested within larger white spaces, such as Predominantly White Institutions (Ohito & Brown, this issue). In this article, there is a deliberate move to evoke rather than merely invoke affect as a thing with which to think and theorize—that is, as a way to know what one perhaps did not know before. The article illustrates the notion that the affective dimensions of knowledge production cannot be effectively communicated through “traditional”—which we know is code for white—and restrictive modes of academic conveyance. In our case, a certain type of writing is utilized as a method for the express purpose of situating “knowledge production in and through the body” (Baszile et al., Citation2016; see also Moten, Citation2003; Nash, Citation2019). In our article—as in Sean Hernández Adkins and Lucía Mock Muñoz de Luna’s “In the Wake of Anti-Blackness and Being: A Provocation for Do-gooders Inscribed in Whiteness”—writing is the tool used to trouble seemingly sedimented knowledge of the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of “Blackness” and “whiteness” as well as the assumed relationship between the two concepts (Ferreira da Silva, Citation2014). In that regard, these articles show writing being deployed to challenge the dominant western or “European-centered conception of knowing as a relationship between subject and object, rather than one between and among subjects located in places, times, and bodies” (Baszile, Citation2015, p. 125).

Space and place repeat as themes in Nicole Joseph’s “Black Feminist Mathematics Pedagogies (BlackFMP): A Curricular Confrontation to Gendered Antiblackness in the US Mathematics Education System.” In this article, Joseph invokes the fiction of Wakanda to interrogate Black schoolgirls’ experiences of math education as a prelude to articulating BlackFMP. Joseph defines BlackFMP as a theoretical and pedagogical framework centered on the idea of Black girls being (allowed to be) fully human in math education and the idea of math education that is responsive to Black girls’ full humanities. Joseph harkens to that imagined Black utopia in order to imagine how Black feminist ways of thinking and doing math education might position Black girls as geniuses and engage their Blackness and girlhoods as constitutive of and constituted by their mathematics identities.

Justin: In line with the ways the aforementioned articles grapple with the intersection of places, times, and bodies, there are several articles that extend our understanding of this interplay in curriculum studies by explicating how Blackness is marginalized as a result of being seen at odds with or outside the boundaries of white/Eurocentric conceptions of the body, time, and place/space. Across the pieces, the authors explicitly detail the ways Black people, in traditional curricular spaces, have re-engaged with curriculum on their terms through a decidedly Black gaze, centering Black ontologies as central, as opposed to marginal. In Brittney Cooper’s (Citation2016) TED talk, “The Racial Politics of Time,” she shared that

If time had a race, it would be white. White people own time…Those who control the flow and thrust of history are considered world-makers who own and master time. In other words: white people. But when Hegel famously said that Africa was no historical part of the world, he implied that it was merely a voluminous land mass taking up space at the bottom of the globe. Africans were space-takers. So today, white people continue to control the flow and thrust of history, while too often treating black people as though we are merely taking up space to which we are not entitled. Time and the march of progress is used to justify a stunning degree of violence towards our most vulnerable populations, who, being perceived as space-takers rather than world-makers, are moved out of the places where they live, in service of bringing them into the 21st century.

Critical Black curriculum studies, as exemplified by the articles in this special issue, forces us to confront the reality that Blackness is world-making and Black people are world-makers. This makes me think of a chant we used to say while I was a high school student in a summer acting program at the historic Black-owned and run Freedom Theater in North Philadelphia. The chant—actually a stanza from O’Shaughnessy’s (Citation1874, p. 1) poem, “Ode”—was:

We are the music makers,

And we are the dreamers of dreams,

Wandering by lone sea-breakers,

And sitting by desolate streams; —

World-losers and world-forsakers,

On whom the pale moon gleams:

Yet we are the movers and shakers

Of the world for ever, it seems

Of course, when this was written in the late 1800s, O’Shaughnessy, a white male poet, did not have Black people in mind as the movers and shakers of the world. However, when the students in the program were bouncing rhythmically in our Blackest fervor, repeating chants after Diane Leslie, our instructor, we knew deep in our souls that despite all that may come our way as Black children in this world, we would always be movers and shakers. I say this to say, in the words of Perry (Citation2020), “Let me be clear: I certainly know I matter. Racism is terrible. Blackness is not.”

Esther, I know Blackness is not terrible. Contrary to popular anti-Black ideologies and technologies, Blackness is the salve for the terrible, a body of fruitful energy and world-making verve. The world knows the beauty of Blackness. For if the world did not know, there would not be systematic efforts to slave the Black, shoot the Black, jail the Black, redline the Black, surveil the Black, disenfranchise the Black, fetishize the Black, appropriate the Black, and so on, you know. In fact, I keep thinking back to my earlier mention of Hughes’ (Citation1926) “I, Too” poem. Towards the end, the speaker says, “and, besides, they’ll see how beautiful I am, and be ashamed.” To me, there seems to be a staunch unwillingness to face Black beauty, and thus to face the shame associated with such an acknowledgment, an acknowledgment of Black humanity. An acknowledgment, a recognition that would prompt a complete restructuring of the entire world. A revolution? In Wah’s (Citation1994) documentary, The Color of Fear, a conversation in the wake of the Los Angeles riots on race relations is captured by Black, Latino, Asian, and white men. Directing his words to a white participant, Victor, a Black participant explained:

Racism is essentially a white problem. And that for you to understand what racism is about you’re gonna be so uncomfortable, you’re gonna be so different from who you see yourself to be now that you know, there is just no way to get it from where you’re sitting. And I’m not saying that you could never get it, I mean that you need to step outside of your skin and step outside of what seems really comfortable and familiar to you and launch out into some real, for you, unknown territory. And you haven’t gone out there and you haven’t gotten in proximity to Black people like you say, because you don’t have to.

In curriculum studies, a microcosm of the larger anti-Black world, there is a similar way in which the field has not had to be in proximity to Blackness. There is a reason why the rallying cry of Black Lives Matter feels so provocative, although it should not. In every aspect of living in learning, Blackness has been devalued, conceptualized as a space-taker. In many of the articles in this issue, the authors consider what a restructuring of curriculum and the world might look like if proximity or even a centering of Blackness was achieved—and here I am specifically referencing Samiha Rahman’s “Black Muslim Brilliance: Countering Antiblackness and Islamophobia through Transnational Educational Migration”; Mildred Boveda, Johnnie Jackson, and Valencia Clement’s “Rappers’ (Special) Education Revelations: A Black Feminist Decolonial Analysis”; Amir Gilmore’s “Riding On Dissonance, Playing Off-Beat: A Jazz Album On Joy”; and my own contribution, “‘It’s Really Geniuses that Live in the Hood’: Black Urban Youth Curricular Un/makings and Centering Blackness in Slavery’s Afterlife.”

At the beginning of my article, I discuss how a Black boy participant named Calvin refuses the ways “the Hood” as a Black space becomes legislated and ideologically codified as worthless, having no impact on the pace and pulse of our world. I center Calvin’s critique early on as it captures the ways U.S. educational institutions, institutions structured in/through anti-Blackness, exclude the living and learning experiences (curriculum) of Black people; this structures and sustains Black students’ relegation to being educated in the belly of the (slave) ship (Sharpe, Citation2016). To be in the belly of the slave ship, in the educational sense, means that Black students across the educational pipeline are dis/engaged and held captive by curricular space and curriculum workers, suspended in time and space, as curriculum being rooted in white supremacy and anti-Blackness only works to enclose Blackness. Through the analysis of Black youth voices, I offer insights into the possibilities of critical Black curriculum studies by illuminating how the youth engage in curricular un/makings. The youth center Black empowerment and affirm Black knowledge as a way to deconstruct anti-Black curriculum through an unapologetic centering of Black ethos.

In explicating the pedagogical practices of the African American Islamic Institute Qur’an School, an Islamic school for U.S-based Black youth in Medina Baye, Senegal, Rahman analyzes the ways the school and the broader community are structured in and through an axiomatic stance of Black Muslim Brilliance. Illuminating the ways students engage in a Black-centric transnational schooling journey, Rahman explains how the intersection of anti-Blackness and Islamophobia in U.S. schools delegitimize the life-worlds and curricular capacities of these Black Muslim students. In Medina Baye, when freed from the unique ways that anti-Blackness and Islamophobia function, Rahman unearths how being transported to such a time and space promotes the youth as critical knowledge producers and resources. Mildred Boveda, Johnnie Jackson, and Valencia Clement, “scholars with distinctive geographical and generational entry points into Hip Hop and U.S. special education,” extend the ways we understand Black students and Blackness as producers of knowledge. They do this by centering Black cultural production in relation to Hip Hop (rap lyrics and videos, specifically) in order to express how the musical genre helps curriculum workers understand the tensions between dis/ability and Black students. Namely, the authors analyze lyrics to explicate the critical ways Hip Hop artists, across time and space, have critiqued the ways U.S. curriculum structurally conflates Blackness, disability, and inferiority. Here, Hip Hop and the Black artists who see it as their duty to critique unequal schooling conditions, become an embodiment of the type of Black beholden-ness needed in critical Black curriculum studies. Similarly, in Amir Gilmore’s article, which is rooted in “Black improvisation, Black aesthetics, and Black fantasy,” we are transcended even further into the depths of Black musical aesthetics. Gilmore theorizes, through the aesthetics of a jazz album, Black boy joy as both a necessary interruption and refusal of the all-white world of curriculum studies. For Gilmore, despite the ways that schools render the plurality of Black boys/boyhood as meaningless or taking up space, if we are attentive to and center their sounds, we can support the ways they compose existence in the wake of slavery’s afterlife. Gilmore closes by sharing the idea that every Black boy has a story to sing, which demonstrates the ways critical Black curriculum studies should and must be seen as a commitment to be beholden to the songs of Blackness, to commit to telling those stories on our terms.

Esther: You know, it's absurd that in this anti-Black world, Black people are forced to not only endure the violence of injustice that materializes in schools and institutions as part of our day-to-day (e.g., Shange, Citation2019); we are also expected to self-soothe our wounds while simultaneously holding space for white people who are tiptoeing too timidly into a nascent awareness that racial injustice exists, let alone extinguishes Black life (Johnson, Citation2020; Phillips, Citation2020; Sanders, Citation2020). I appreciate greatly that the articles in this special issue carry me away from co-opted, commodified, neoliberal notions of racial justice and towards something unknown, and there, the possibilities for what Black/ness could be/come are infinite. Justin, these articles help me—us, really—escape to a place where racial justice won’t know how to find us.

If justice is a matter of relations within a specific system, then justice might very well be said system’s most powerful strategy for reinforcing its permanence. Justice might very well be reinforcement masquerading as resolution; an “I-can’t-breathe” hushed into the sleep of a broken neck; the haunting cries of broken bones flattened into a civil highway. All very modern. They say we must fix our eyes on justice, on the hilltop, on the road that leads to a bright new day. I say, where we are going, we don’t need no roads. We will break into the edges and rush into the bushes along the highway. And only the wind will whisper stories of our marronage. We will anoint the bloodied bodies of our dead ones and grieve around the sagging breasts of our old mothers. And there, in the strangeness of a gifted moon, in the generative failure of our fugitivity, in the sweltering heat of new histories and speculative futures, we will shift into another shape. And justice won’t know how to find us. (Akomolafe, Citation2020)

Justice won’t know how to find us if we break free and fly away, you know.

Lines of Future Flight

Justin: It is interesting to be here, in this specific moment in time and space, curating a Black-centric special issue for Curriculum Inquiry (CI) with you Esther, a dynamic Black woman who I seem to never stop learning with and from. As I think about what this issue brings for us and the larger field and how it launches us into the next moment of critical Black curriculum studies, I first and foremost think about the importance of collaboration and collectivism in the Black tradition. I think we have modeled this here in this space and elsewhere, particularly during our time as Cultivating New Voices (CNV) among Scholars of Color fellows with the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). So, in thinking about the futurity of this work, I want to underscore that it should be rooted in a beholden-ness to each other, to ourselves, and to Black communities, locally and globally. In my article for this special issue, I share Sharpe’s (Citation2016) contention that because education takes place in the belly of the (slave) ship, we must engage in the process or state of being of beholding characterized by “inhabiting a blackened consciousness that would rupture the structural silences produced and facilitated by, and that produce and facilitate, Black social and physical death” (p. 22). Accordingly, I see critical Black curriculum studies as an orientation to, or rather a desire for, Black beholden-ness, ensuring the futurity and sustainability of Black curricular life and Black curricular space/s. As critical Black curriculum theorists, how do we see our work as a responsibility to Blackness?

Words from James Baldwin and his discussion of the necessity of a blackened consciousness in an anti-Black world help me better articulate my imagining of the future of research on anti-Blackness in curriculum studies and/as being rooted in Black beholden-ness. In 1968, while on The Dick Cavett Show, Baldwin precisely captured the ways being Black in the United States naturally instills—and, more so, requires—a heightened consciousness in Black people that they must be attentive to as a matter of survival (Baldwin & Peck, Citation2017). For me, our intentional move to usher in critical Black curriculum studies in this special issue is directly aligned with theorizations of Black/ened consciousness, which Biko (Citation1998) described as Black people collectively operating to “rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude…to demonstrate the lie that black is an aberration from the ‘normal’, which is white” (p. 360). Biko further noted, Black consciousness “seeks to infuse the black community with a new-found pride in themselves, their efforts, their value systems, their culture, their religion and their outlook on life” (p. 360). Here, we see that consciousness for Black people teeters along a dual existence, where one must be deeply aware of anti-Blackness in order to survive, while also rejecting the logics of anti-Blackness to create rich, joyous lives that refuse Black suffering. In sharing how he ended up living in Paris, France, Baldwin explained that as a writer, one needs “to turn off all the antennae with which you live” to concentrate, but for Black people, “once you turn your back on this society you may die” (Baldwin & Peck, Citation2017). As Baldwin shared, leaving behind the United States and its anti-Blackness, which has been “unabated from generation to generation” (Washington, Citation1981), released him from a “particular social terror” (Baldwin & Peck, Citation2017). According to Baldwin, this social terror did not stem from the paranoia of his own mind, rather it was “a real social danger visible in the face of every cop, every boss, everybody.” Baldwin spoke of an omnipresent social terror that Black folks face, which is captured in Sharpe’s (Citation2016) cautionary note that “at stake is not recognizing antiblackness as total climate” (p. 21). Thus, when we consider the ways Black students and communities who carry out their beautiful Black lives under this regime of social terror in the wake of slavery, the critical Black curriculum studies move towards beholding is not only apropos, but an imperative in the pursuit of Black liberatory curriculum space/s—an imperative in the pursuit of Blackness.

Esther: I am hopeful that future work in critical Black curriculum studies will decenter the United States, and the west, more broadly. As you likely remember, the fact that the issue is U.S-centered was underlined by Jacqueline Scott, a member of the phenomenal CI team, during the editorial meeting in the fall of 2019. My memory of this was sparked months later as I read the words of transnational/Ghanaian-Canadian scholar George Sefa Dei (this issue). Regarding anti-Blackness in Canada, the particular places and names Dei references in the foreword to this special issue were new to me, even though I nodded my head in agreement with his analysis of the general effects of this virulent strain of violence. My point is that the particular hi/story of Black people in the United States is one of multitudes of narratives of Blackness. Ergo, because all hi/stories are emplaced, I desire more scholarship on anti-Blackness in curriculum studies that engages embodiment and spatialization as robustly as authors such as you, Gilmore, and Rahman do. I want more of this because Black/ness is more than a social construct, category of analysis, and ontological position; “blackness is like ‘darkness over the surface of the deep’ as in the biblical myth from Genesis”—that is, “primordial, yet unformed; formless, yet formable; a fecund materiality, yet also creative movement and kinetic potency” (Braziel, Citation2010, p. 22). If Blackness is limitless, then there are unlimited topics crossing Black/ness and knowledge production available for the curious curriculum worker. The ground being broken by scholars interrogating what it means to be Black and human (or not) in relation to the wider global African diaspora (Wright, Citation2015) as well as in relation to the Anthropocene (Yusoff, Citation2018), animalities (Bennett, Citation2020), post/humanisms (Jackson, Citation2020), new materialisms (Leong, Citation2016; Tompkins, Citation2016), and more indicates that

Blackness, in all its metaphors and historical submergence, reaches out to theory, then, as theory split from itself. It is the dark side of theory, which, in the end, is none other than theory itself, understood as self-reflective, outside itself. (Gordon, Citation2010, pp. 196–198)

All that to say, I am excited for more curriculum theory and curriculum studies scholarship situated primarily but not singularly at the crossroads of critical Black studies and critical curriculum studies—what we are naming here as critical Black curriculum studies.

Let me close by saying that I have been animated by the process of co-creating with you, Justin, our intellectually generous thought partners in the embryonic phase of this process, fahima indigo ife and Michael Dumas, and our incisive reviewers. I am awed by your unassuming, penetrating brilliance. I have also enjoyed and learned a tremendous amount from the CI editorial team’s collaborative pedagogical approach to publishing (Ramjewan et al., Citation2018). Many moons ago, a sister-friend wisely recommended I read John-Steiner's (Citation2006) Creative Collaboration. The book illustrates that there’s a beautifully intentional choreography to collaborations that are powered by cultivated creativity. Such collaborations are rare gems. So, for me, each such collaboration is a fugitive space, a refuge where I can source fuel for intellectual flight. For me, each is a place to practice and play with being fully Black and fully human simultaneously, a space where I can possibly and potentially acquire and produce much knowledge about how to live freely as a Black African woman, a free Black human being. Creatively and collaboratively researching, teaching, and writing about that is how we fly away, Justin. I’m tellin’ you, that’s why and how Black people will live forever.

Acknowledgements

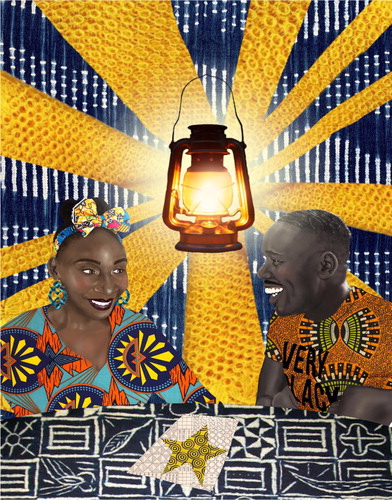

We are enormously grateful to Grace D. Player for the stunning artwork, as well as to Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández and Ligia (Licho) López López for generously providing feedback on working drafts of this editorial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Esther O. Ohito

Esther O. Ohito is an assistant professor of curriculum studies in the School of Education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the inaugural Toni Morrison Faculty Fellow at the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Center of Racial Justice and Youth Engaged Research. Broadly, her oeuvre centers Black women and girls and amplifies Black voices and knowledges. A transnational interdisciplinary scholar, she researches Blackness, race, and gender at the nexus of curriculum, pedagogy, embodiment, and emotion.

Justin A. Coles

Justin A. Coles is an Assistant Professor in the division of Curriculum and Teaching at Fordham University, Graduate School of Education. His multidisciplinary research agenda draws from critical race studies, urban education, and language and literacy to inform justice-centered educator preparation, particularly helping to inform the ways we develop counter structures to oppressive socio-political regimes in schools and society.

Notes

1 This subheading riffs on the oft-cited declaration Anna Julia Cooper made in her 1892 book, A Voice from the South. Cooper (Citation2016, p. 12) stated, “when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.”

2 Here, “Black” is code for people of African descent. Recognizing the politics of race embedded in contestable language rules specific to capitalization, grammar, et cetera, we deliberately use upper case “B” in “Black” when referring to people of African descent and lower case “w” in “white.” We defer to the cited authors’ capitalization choices in works cited.

3 Ignorance is conceptualized here as a resistance to or rejection of knowledge (e.g., Peels & Blaauw, Citation2017; Sullivan & Tuana, Citation2007).

References

- Akomolafe, B. (2020, May 26). If justice is a matter of relations within a specific system, then justice might very well be said system's most [Status update]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?id=13,03,94,68,75,89,146&story_fbid=57,26,89,72,00,26,305

- Anzaldúa, G. (2015). Light in the dark/Luz en lo Oscuro [Rewriting identity, spirituality, reality] (A. Keating, Ed.). Duke University Press.

- Ayers, W., & Quinn, T. (2008). Teach freedom: Education for liberation in the African-American tradition (C. M. Payne & C. S. Strickland, Eds.). Teachers College Press.

- Baldwin, J., & Peck, R. (2017). I am not your negro: A companion edition to the documentary film directed by Raoul Peck. Vintage.

- Baszile, D. (2015). Critical race/feminist currere. In M. F. He, B. D. Schultz, & W. H. Schubert (Eds.), The Sage guide to curriculum in education (pp. 119–126). Sage.

- Baszile, D. T., Edwards, K. T., & Guillory, N. A. (Eds.). (2016). Race, gender, and curriculum theorizing: Working in womanish ways. Lexington Books.

- Behm, C. (2019). CPD bodycams show fatal standoff before fatal shooting of bipolar man: “Myles, don’t point the gun at nobody else!” Chicago Sun Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/crime/2019/7/20/20701651/bodycam-standoff-myles-frazier-woodlawn-cpd-police-shooting-fatal

- Bell, D. A. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Basic Books.

- Bennett, J. (2020). Being property once myself: Blackness and the end of man. Belknap Press.

- Biko, S. (1998). The definition of Black consciousness. In P. H. Coetzee & A. P. J. Roux (Eds.), Philosophy from Africa: A text with readings (pp. 360–363). Halfway House: International Thomson Publishing.

- Braziel, J. E. (2010). Caribbean genesis: Jamaica Kincaid and the writing of new worlds. State University of New York Press.

- Brock, R., Nix-Stevenson, D., & Miller, P. C. (Eds.). (2016). Critical Black studies reader. Peter Lang.

- Christian, B. (1988). The race for theory. Feminist Studies, 14(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177999

- Church, R. L., & Sedlak, M. W. (1976). Education in the United States: An interpretive history. Free Press.

- Collins, P. H. (2009). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

- Conte, E. S. (2020). Letter from the editor. SEM Student News, 15(2), 1–3. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.ethnomusicology.org/resource/group/dc75b7e7-47d7-4d59-a660-19c3e0f7c83e/publications/semsn15.2.pdf

- Cooper, A. J. (2016). A voice from the south. Dover Thrift.

- Cooper, B. (2016). The racial politics of time [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/brittney_cooper_the_racial_politics_of_time?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

- Cromby, J., & Willis, M. E. H. (2016). Affect—or feeling (after Leys). Theory & Psychology, 26(4), 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354316651344

- Deconto, J. J., & Blinder, A. S. (2018, August 21). ‘Silent Sam’ confederate statue is toppled at University of North Carolina. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/21/us/unc-silent-sam-monument-toppled.html

- Dernikos, B., Lesko, N., McCall, S. D., & Niccolini, A. (Eds.). (2020). Mapping the affective turn in education: Theory, research, and pedagogies. Routledge.

- Desai, C. (2012). Do we want something new or just repetition of 1492?: Engaging with the “next” moment in curriculum studies. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 28(2), 153–167.

- Dillard, C. B. (2007). On spiritual strivings: Transforming an African American woman’s academic life. State University of New York Press.

- Dillard, C. B. (2012). Learning to (re)member the things we’ve learned to forget: Endarkened feminisms, spirituality, and the sacred nature of research and teaching. Peter Lang.

- Ellison, R. (1995). Invisible man (2nd ed.). Vintage Books.

- Ferreira da Silva, D. (2014). Toward a Black feminist poethics: The quest(ion) of Blackness toward the end of the world. The Black Scholar, 44(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2014.11413690

- Fitzgerald, T. (2009, January 10). The Black prison called “special education.” Racism Review. http://www.racismreview.com/blog/2009/01/10/the-black-prison-called-“special-education”/

- Fustec, C. L. (2011). “Never break them in two. Never put one over the other. Eve is Mary’s mother. Mary is the daughter of Eve”: Toni Morrison’s womanist gospel of self. E-rea, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.4000/erea.1680

- Garcia-Rojas, C. (2017). (Un)disciplined futures: Women of color feminism as a disruptive to white affect studies. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 21(3), 254–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1159072

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A. (2006). Regarding race: The necessary browning of our curriculum and pedagogy public project. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 3(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2006.10411576

- Gordon, L. R. (2010). Theory in Black: Teleological suspensions in philosophy of culture. Qui Parle, 18(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.5250/quiparle.18.2.193

- Grumet, M. R. (1988). Bitter milk: Women and teaching. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Grumet, M. R. (1989). Generations: Reconceptualist curriculum theory and teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718904000104

- Gumbs, A. P. (2010). “We can learn to mother ourselves”: The queer survival of Black feminism [Doctoral dissertation, Duke University]. DukeSpace. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/2398

- Guthrie, C. (2016). How does it feel: On emotional memory and difficult knowledge in education. Curriculum Inquiry, 46(5), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2016.1254415

- Hartman, S. V. (1997). Scenes of subjection: Terror, slavery, and self-making in nineteenth-century America. Oxford University Press.

- He, M. F., Schultz, B. D., & Schubert, W. H. (Eds.). (2015). The SAGE guide to curriculum in education. Sage Publications.

- hooks, b. (1996). Bone black: Memories of girlhood. Holt Paperbacks.

- Hord, F., & Lee, J. (Eds.). (2016). I am because we are: Readings in Africana philosophy (2nd ed.). University of Massachusetts Press.

- Hughes, L. (1926). The weary blues. Knopf.

- Hull, G. T., Gallagher, P., & Brooks, G. (1977). Update on “part one”: An interview with Gwendolyn Brooks. CLA Journal, 21(1), 19–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44329322

- Jackson, Z. I. (2020). Becoming human: Matter and meaning in an antiblack world. NYU Press.

- Johnson, T. (2020, June 11). Perspective | When Black people are in pain, white people just join book clubs. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/white-antiracist-allyship-book-clubs/2020/06/11/9edcc766-abf5-11ea-94d2-d7bc43b26bf9_story.html

- John-Steiner, V. (2006). Creative collaboration. Oxford University Press.

- Kirkland, D. E. (2017). “Beyond the dream”: Critical perspectives on Black textual expressivities … between the world and me. English Journal, 106(4), 14–18.

- Leong, D. (2016). The mattering of Black lives: Octavia Butler’s hyperempathy and the promise of the new materialisms. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 2(2), 1–35.

- Malewski, E. (2009). Curriculum studies handbook: The next moment. Routledge.

- Marable, M. (2006). Living Black history: How reimagining the African-American past can remake America’s racial future. Civitas Books.

- McClellan, H. (2020, January 28). Unmarked graves of enslaved people demonstrate Chapel Hill’s dark past. The Daily Tar Heel. https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2020/01/chapel-hill-unmarked-graves

- McKissack, P. C., & McKissack, F. (1994). Sojourner Truth: Ain’t I a woman? Scholastic.

- Moraga, C., & Anzaldúa, G. (Eds). (2015). This bridge called my back: Writings by radical women of color (4th ed.). State University of New York Press.

- Morrison, T. (1988). Unspeakable things unspoken: The Afro-American presence in American literature [The Tanner lectures on human values]. The University of Michigan. https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/m/morrison90.pdf

- Morrison, T. (1990). Playing in the dark: Whiteness and the literary imagination. Vintage.

- Moten, F. (2003). In the break: The aesthetics of the Black radical tradition. University of Minnesota Press.

- Moten, F. (2018). Stolen life. Duke University Press.

- Nakagawa, S. (2012, May 4). Blackness is the fulcrum. Race Files. https://www.racefiles.com/ 2012/05/04/blackness-is-the-fulcrum/

- Nash, J. C. (2019). Writing Black beauty. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 45(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1086/703497

- Neloms, K. (2020, June 10). No bad apples: Actors in anti-Black systems have created too much collective harm to be judged individually. RaceBaitr. https://racebaitr.com/2020/06/10/no-bad-apples-actors-in-anti-black-systems-have-created-too-much-collective-harm-to-be-judged-individually/

- O’Shaughnessy, A. (1874). Music and moonlight: Poems and songs. Chatto and Windus, Publishers.

- Ohito, E. O. (2016). Refusing curriculum as a space of death for Black female subjects: A Black feminist reparative reading of Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl.” Curriculum Inquiry, 46(5), 436–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2016.1236658

- Ohito, E. O. (2020). Some of us die: A Black feminist researcher’s survival method for creatively refusing death and decay in the neoliberal academy. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1771463

- Olaloku-Teriba, A. (2018). Afro-pessimism and the (un)logic of anti-Blackness. Historical Materialism, 26(2), 96–122. https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-00001650

- Palmer, T. S. (2017). “What feels more than feeling?”: Theorizing the unthinkability of Black affect. Critical Ethnic Studies, 3(2), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.3.2.0031

- Peels, R., & Blaauw, M. (Eds.). (2017). The epistemic dimensions of ignorance. Cambridge University Press.

- Perry, I. (2020, June 15). Racism is terrible. Blackness is not. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/racism-terrible-blackness-not/6,13,039/

- Philip, M. N., & Boateng, S. A. (2011). Zong! Wesleyan University Press.

- Phillips, H. (2020, June 4). Performative allyship is deadly (here’s what to do instead). Medium. https://forge.medium.com/performative-allyship-is-deadly-c900645d9f1f

- Pinar, W. F. (2019). What is curriculum theory? (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Pinar, W. F., & Grumet, M. R. (Eds.). (2014). Toward a poor curriculum. Educator’s International Press.

- Pryse, M. L., & Spillers, H. J. (Eds.). (1985). Conjuring, Black women, fiction, and literary tradition. Indiana University Press.

- Rabaka, R. (2009). Africana critical theory: Reconstructing the Black radical tradition, from W. E. B. Du Bois and C. L. R. James to Frantz Fanon and Amilcar Cabral. Lexington Books.

- Ramjewan, N. T., Guthrie, C., & Gaztambide-Fernández, R. (2018). Publishing as pedagogy: Essays from the 2017 Curriculum Inquiry Writers’ Retreat. Curriculum Inquiry, 48(3), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1482393

- Reeves, M. (2017, December 26). The Roots’ Black Thought on how he spit nearly 10-minute viral freestyle. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/the-roots-black-thought-on-how-he-spit-nearly-10-minute-viral-freestyle-197206/

- Reynolds, W. M. (2014). Critical studies of southern place: A reader. Peter Lang.

- Rickford, R. (2016). We are an African people: Independent education, Black power, and the radical imagination. Oxford University Press.

- Sanders, C. (2020, June 5). Opinion | I don’t need ‘love’ texts from my white friends. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/05/opinion/whites-anti-blackness-protests.html

- Shange, S. (2019). Progressive dystopia: Abolition, antiblackness, and schooling in San Francisco. Duke University Press.

- Sharpe, C. (2010). Monstrous intimacies: Making post-slavery subjects. Duke University Press.

- Sharpe, C. (2016). In the wake: On Blackness and being. Duke University Press.

- Sierschynski, J. (2020). Improvising identity, body, and race. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 20(5), 429–433. (5), https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708619830129

- Smith, D. (2017). Don’t call us dead: Poems. Graywolf Press.

- Spillers, H. J. (1987). Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics, 17(2), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/464747

- Stella Adler Studio of Acting. (2016, June 16). Toni Morrison’s final thoughts at “art and social justice” [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3hhoyTbP6A

- Sullivan, S., & Tuana, N. (Eds.). (2007). Race and epistemologies of ignorance. SUNY Press.

- Tompkins, K. W. (2016). On the limits and promise of new materialist philosophy. Lateral, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.25158/L5.1.8

- Vizenor, G. R. (2008). Survivance: Narratives of native presence. University of Nebraska Press.

- Wah, L. M. (Director & Producer). (1994). The color of fear [Film]. StirFry Seminars & Consulting.

- Warren, C. A., & Coles, J. A. (2020). Trading spaces: Antiblackness and reflections on Black education futures. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(3), 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1764882

- Washington, J. R. (1981). The religion of antiblackness. Theology Today, 38(2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/004057368103800203

- Wilderson, F., III. (2017, May 25). Irreconcilable anti-Blackness: A conversation With Dr. Frank Wilderson III [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k1W7WzQyLmI

- Williams, H. A. (2007). Self-taught: African American education in slavery and freedom. University of North Carolina Press.

- Williams, K. T. E., Baszile, D. T., & Guillory, N. A. (Eds.) (2018). Black women theorizing curriculum studies in colour and curves. Routledge.

- Wright, M. M. (2015). Physics of Blackness: Beyond the middle passage epistemology. University of Minnesota Press.

- Wynter, S. J. (1989). Beyond the word of man: Glissant and the new discourse of the Antilles. World Literature Today, 63(4), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.2307/40145557

- Wynter, S. J. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation—An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257–337. https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2004.0015

- Wynter, S. J. (2010). The hills of Hebron. Ian Randle Publishers.

- Yusoff, K. (2018). A billion Black anthropocenes or none. University of Minnesota Press.