Abstract

Recently, talk of “fake news” – and its relation to wider epistemic crises, from climate denialism to the creep of global ethno-nationalism – has renewed attention to media literacy in education. For some, revived discussions of media literacy offer protection (e.g., strategies for identifying and critiquing media bias and misinformation). For others, they offer empowerment (e.g., equipping youth to produce media messages that challenge misinformation or represent marginalized perspectives). In this article, we consider how such approaches, while often generative, retain a focus of media pedagogy that centers the actions of individual humans – namely, “literacies,” or practices associated with the interpretation or creation of media texts. This orientation, we suggest, elides more distributive agencies, human and nonhuman, that animate contemporary media contexts and their usage: the imbrication of material (hardware), aesthetic (interfaces), computational (algorithms), and regulatory (protocols/defaults) actors with wider networks of institutional governance and political economy. Drawing from theories of scalar assemblages, posthumanist performativtity, and platform studies, we demonstrate how an alternate orientation to media pedagogy – one grounded in “ecology” rather than “literacy” – provides a wider repertoire of resources for navigating contemporary media environments, including (but not limited to) the challenges wrought by post-truth politics. Importantly, we suggest that an orientation of “civic media ecology” does not obviate traditional representational concerns of media literacy, but augments them by making legible the performative entanglements that constitute and animate processes of media production and consumption.

In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries named “post-truth” its word of the year, citing a 2000-percent increase in usage over the preceding months (Wang, Citation2016). The term, which denotes a condition where truth becomes secondary to personal belief in matters of public opinion, seemed to encapsulate a disquieting current running through many of the year's political upheavals. It was not just that the Leave. EU campaign eked out a victory in the Brexit referendum, or that Donald Trump was elected to the US presidency, but that each was accompanied by coordinated disinformation campaigns, sowing distrust in the journalistic scrutiny and scientific consensus that threatened their preferred positions. Around the globe, parallel tactics were being deployed among reactionaries in France, Germany, Brazil, and Myanmar (Connolly et al., Citation2016). Most troubling about this “post-truth” politics was not the epistemic challenges wrought by public skepticism toward journalists or experts – these had histories extending well before 2016 (Arceneaux et al., Citation2016; Hofstadter, Citation1963). But at a time when such suspicions were caught up with intensifying political entrenchments (Gallup, Citation2018), the consolidation of nativist populism (Judis, Citation2018), and the disastrous realities of the refugee and climate crises (Gavin, Citation2018), “post-truth” signaled not just an epistemic threat, but a potentially existential one.

It is against this backdrop that “media literacy” has received revived attention as a priority for education research and practice in the Global North. Since 2016, it has been the subject of special issues, edited volumes, and whitepapers – each weighing how the concept might be mobilized in response to the challenges of post-truth politics (Bulger & Davison, Citation2018; Journell, Citation2019; Mason et al., Citation2018). Though the precise meaning of the term is contested (cf. Koltay, Citation2011), media literacy is most commonly understood as the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create messages across media contexts (Aufderheide, Citation1992; Christ & Potter, Citation1998; Livingstone, Citation2004). Articulations of media literacy’s promise for the present tend to stress two dimensions of this popular usage. First, it offers consumption-oriented strategies for analyzing texts, demystifying ideologies, and vetting truth-claims in print and digital media (Breakstone et al., Citation2018). And second, it offers production-oriented practices for creating messages that refute misinformation, challenge dominant narratives, and reflect marginalized perspectives (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, Citation2012). When paired together, advocates argue, these foci can provide robust pedagogical resources for navigating today’s media landscape (Alvermann et al., Citation2018) and for taking a critical stance against inaccurate and hegemonic media content (e.g., Baker-Bell et al., Citation2017; Kellner & Share, Citation2007).

Not everyone, however, is convinced of media literacy’s fitness for addressing the post-truth present. In her 2018 SXSW Education keynote, media theorist danah boyd asserted that the project of media literacy has backfired. The same consumption and production practices that advocates celebrate, she argued, are now being weaponized in reactionary agendas for climate denialism and white supremacy (boyd, Citation2018). In other words, by promoting a posture of generalized skepticism – which can be used to dismiss credible information as easily as it can fascist propaganda or racist conspiracies – practices associated with media literacy can be seen as contributing to, rather than ameliorating, the problems of post-truth politics. Echoing wider arguments in social theory over the limits of “critique” as a mode of political intervention (Latour, Citation2004; Marcus et al., Citation2016), boyd’s provocation has prompted contentious scholarly debate, with some coming to media literacy’s defense and others further sounding its death knell (Buckingham, Citation2020; Hobbs, Citation2018b) – leaving the future of media literacy in limbo.

In this article, we are less concerned with taking sides in such debates than with interrogating their premises. At issue, we suggest, is not the inefficacy of media education for engaging post-truth politics or contemporary media contexts, but rather, the inadequacy of “literacy” as the guiding idiom for doing so. We argue, first, that the contingent historical process by which media education has emerged in popular usage as a form of “literacy” has tended to tether curricular attention to the representational politics of media: that is, how media messages are created, interpreted, mobilized, or critiqued. While this has resulted in many generative and impactful resources for educators (indeed, both authors have drawn on and contributed to this tradition in literacy research; Campano et al., Citation2020; Stornaiuolo & LeBlanc, Citation2014; Stornaiuolo & Nichols, Citation2018), it also places the locus of media pedagogy on the production and consumption of texts (and, often, on the agentive actions of those engaged in such practices). In other words, the idiom of “literacy” inherits important limitations for addressing those facets of media systems that are peripheral to textualization or irreducible to representation. This includes the material, aesthetic, algorithmic, and economic activities that animate today’s connective media platforms and that overdetermine observable public crises, like post-truth politics.

We then argue, in the second half of the article, that an alternate orientation – one that revives and reworks an earlier idiom of “ecology” in media pedagogy – offers one avenue for attending to the performative politics of media and, in doing so, for navigating the present gridlocks in media education. We conceptualize this orientation using theories of scalar assemblage (DeLanda, Citation2006), posthuman performativity (Barad, Citation2003), and platform studies (Bratton, Citation2015a). What results, we suggest, is a stance of civic media ecology – a phrase that, at once, acknowledges the crucial contributions of existing civic and media education research and practice (Mihailidis, Citation2018; Mirra & Garcia, Citation2020; Morrell, Citation2012), while also gesturing to the wider range of resources that might be brought to bear in teaching, learning, and action in our emerging media environment. By articulating contemporary notions of “media ecology” alongside an attention to “civics,” a civic media ecology can help educators identify important performative dynamics of the media environment and target key sites for civic analysis and action. Importantly, we stress that such a stance does not obviate the representational concerns of “literacy,” but rather relocates them within a wider repertoire of tactics for understanding and intervening in platform ecologies. In this way, we see civic media ecology as an orientation not only for scholars interested in the interplay of digital media and literacy studies, but also for those whose work runs parallel to (yet is not always co-articulated with) these areas of inquiry. While it is outside the scope of this article to offer a full delineation of the collaborative relations a frame of civic media ecology makes possible, we highlight some of the generative possibilities we envision in our conclusion.

Making Media “Literacy”

We begin by tracing the history of how media education, in the Global North, came to adopt “literacy” as a guiding idiom and, with it, an emphasis on the representational concerns of textual consumption and production over alternate paths of inquiry. In mapping this evolution, our purpose is to be demonstrative, not definitive: there is no singular history of media education, and there are almost certainly irregularities at the edges of our account whose study would add welcome texture in a more exhaustive chronicle of the field. Our aim in this section is to show that the popular version of media education we have inherited was neither inevitable nor uncontested. These contingencies, we suggest, offer clarifying insights into why the concept can feel strained in the present media environment.

Representation in Media and Literacy Education

Media education has long shared overlapping interests with literacy education. The two most common historiographies of the field trace media education’s roots through “propaganda analysis” in the US and “critical awareness” training in the UK. The former armed students with techniques to analyze news, advertisements, and films for bias and misinformation (Hobbs & McGee, Citation2014); the latter equipped them to create and critique media and cultivate more discriminating cultural tastes (Buckingham, Citation2013). Though neither lineage explicitly narrated itself as a “literacy” pedagogy, it is easy to see in each practices closely correlated with literacy: sourcing, close reading, aesthetic evaluation, ideological critique, and inquiry into textual production. Such practices remain central to present-day media education, which has, in popular usage, come to be used interchangeably with “media literacy” (Hobbs, Citation1994). The most widely adopted definition of the term continues to stress students’ capacities to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media messages (Aufderheide, Citation1992), though the cultural and political purposes for such activities have evolved.

This continuity crystalizes a pattern in the relationship between media and literacy education. They are coupled through a shared interest in representation: how symbols (words, images, multimedia texts, etc.) can be organized or interpreted to reflect, reveal, distort, or conceal realities, ideas, and ideologies. This is evinced not only in scholarly literature from both fields that asserts this commonality (e.g., Kellner, Citation1998; Luke, Citation2013; Masterman, Citation1980), but also in the historical tendency for media pedagogy to enter the formal school curriculum by way of literacy classrooms (Hobbs, Citation2007; Postman, Citation1961). This is not to flatten important differences between the two: neither “literacy” nor “media” is a monolith, and the contested meanings of the former – as an encoding and decoding of alphabetic print (Ong, Citation1982), a power-laden social practice (Street, Citation1984), or an engagement with or across media texts (New London Group, Citation1996) – have yielded a range of curricular priorities that vary in their reception of the latter. Rather, we spotlight this joint interest in representation because it helps to clarify how the emergence of “literacy” as a dominant idiom for media education has been prefigured even in some of its earliest formulations.

Media and/as Environment

Yet, the inherited histories of media education’s origins can paper over competing orientations that were concurrently in circulation. The historiography of media education has tacked closely to representational practices (e.g., the production and consumption of media messages), but contemporaneous accounts suggest other scholars and educators took a greater interest in the interplay of media and milieu. Adorno’s (Citation1950) study of “the authoritarian personality,” for example, suggested it was not media messages, but media environments that made individuals susceptible to totalitarian propaganda. Horkheimer (Citation1950) argued this explicitly, saying, “The Germans were conditioned for fascist regimentation by the general structure of society. They were used to accepted models submitted to them by radio, motion pictures, and the illustrated weekly long before they heard the Führer himself” (p. 288). Media historian Fred Turner (Citation2013), likewise, has documented the US government’s post-war investment in creating “democratic surrounds” – interactive, multimedia environments that were meant to foster more egalitarian relations between individuals and collectives. Such orientations, removed from context, may read as eccentric or paranoid today, but they demonstrate that “literacy” and representation were never the sole or inevitable means for engaging or understanding media pedagogy.

Once attuned to this “environmental” perspective, it is possible to find traces of it latent even in the established histories of media education. For instance, Leavis and Thompson (Citation1933), who originated the “critical awareness” tradition in the UK, titled their pioneering media textbook Culture and Environment. While their central concerns were overwhelmingly representational (focussed on nurturing students’ aesthetic discrimination of texts), their emphasis on “environment” gestures towards a reciprocal relationality between representational media and the social landscape. This impulse was further refined in the British Cultural Studies tradition that built on their work. Hoggart’s (Citation1958) The Uses of Literacy and Williams’s (Citation1962) Communication, for example, retained an interest in representation, but viewed it as inseparable from the “ways of living” that conditioned media texts and their usage. Such works introduced a materialist analysis of culture and industry that informed subsequent contributions to secondary and adult media education, most notably in Hall and Whannel's (Citation1964) The Popular Arts. While this tradition was not a clean break from representationalism, always retaining a strong interest in textual analysis and aesthetic discrimination, it opened the frame of media pedagogy to be more attuned to environmental dynamics that animate textual production and consumption.

The Triumph of “Literacy”

At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, theorizations of media-as-environment gave rise to several robust education programs focussed on “media ecology.” These included Marshall McLuhan’s City as Classroom textbook and Neil Postman’s The New English curriculum series. Such resources paid less attention to the representational content of media, and instead, emphasized inquiry into media environments, or the dialectical co-construction of mediating tools and social worlds (cf. Mason, Citation2016). However, these efforts were short-lived. According to his son and co-author, McLuhan’s theory-heavy textbook was too idiosyncratic for day-to-day use by teachers (E. McLuhan, personal communication, April 24, 2014), and Postman pivoted his attention to the postsecondary Media Ecology program at New York University (Gencarelli, Citation2006). The British Cultural Studies tradition fared better, finding uptake in the 1980s as Masterman’s (Citation1980) synthesis of this work became the basis for a range of transnational media education policies (e.g., Ontario Ministry of Education, Citation1987; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2011). However, the elements that were most readily absorbed into curricula were those that centred the production and interpretation of media texts – that is, representational literacy practices – and not “environmental” analysis (Nichols & Stornaiuolo, Citation2019).

This alignment was cemented in the 1990s when several well-funded initiatives worked to spread “media literacy” in US K-12 education, and the term emerged as a dominant orientation for media pedagogy (Hobbs, Citation1998). In 1992, the Aspen Institute convened a meeting of experts to consolidate a research agenda for “the media literacy movement.” The resulting report reiterated the centrality of literacy to media education. It named its principal goal as “the [expansion] of literacy to include powerful post-print media that dominate our information landscape” (Aufderheide, Citation1992, p. 1). Even more, it tied media pedagogy to a definition focussed exclusively on representational practice – “accessing, analyzing, evaluating, and creating” media messages (p. 6) – one that continues to frame popular usage of the concept to the present (Hobbs, Citation2018a; Livingstone, Citation2004).

This is not to say that “media literacy,” as a concept, has gone uncontested since then. Scholars have criticized its tendencies towards protectionism (Buckingham, Citation1998) and have questioned its inattention to the political and economic interests of media industries (Lewis & Jhally, Citation1998). But these critiques have largely centred on the content of media literacy, not its form. With few exceptions (e.g., Buckingham, Citation1993; Livingstone, Citation2008), they do not challenge the idea of organizing media education in the idiom of “literacy” or around representational practices associated with the production of consumption of media texts. Indeed, in moments when “media literacy” strains to explain some phenomenon, the most common response is not to question the focus on “literacy,” but to double-down, adding new and expansive forms of it under media literacy’s umbrella: information literacy (Koltay, Citation2011), news literacy (Mihailidis, Citation2012), digital literacy (Hobbs, Citation2010), and data literacy (Pangrazio & Selwyn, Citation2019).

The Limits of “Literacy”

Today, concerns over post-truth politics are beginning to make visible the limitations of “literacy” as a guiding idiom for navigating the emerging media landscape. Though there is increased public demand for media literacy education as an antidote for “fake news,” there is little agreement about what such an approach should look like (Bacon, Citation2018; Bulger & Davison, Citation2018). Many have argued, convincingly, that there is a need to ground media literacy in principles of civic learning and action. For some, this means nurturing “civic intentionality” by rooting media consumption and production practices in values like agency, care, persistence, critical consciousness, and emancipation (Mihailidis, Citation2018). For others, it means cultivating forms of “civic reasoning” by adopting critical reading practices to distinguish between reliable and unreliable information (McGrew et al., Citation2017). Such approaches are generative, to be sure, and they offer concrete resources that are immediately usable in classrooms. Indeed, we have used them in our own teaching and advising. But they also continue to bring a representational lens to the challenges of post-truth politics and “fake news.” That is, they position such issues either as problems of asymmetrical representations (addressable through the production and mobilization of critical counter-representations) or of misleading representations (addressable through more refined strategies for identifying erroneous content). Impactful as they are, our concern is that such orientations can overlook important dimensions of connective media technologies that are less amenable to representational analysis or civic intervention via “literacy,” yet are no less implicated in the construction of public crises, like “fake news.”

To take an example from one of the most prominent of these responses, Wineburg and the Stanford History Education Group have developed the concept of “lateral reading” (Wineburg & McGrew, Citation2019), which delineates the practices of professional fact-checkers as a guiding light for all media-literate web-readers. Documenting the inability of a range of highly educated readers to determine the veracity of multiple websites, Wineburg and his team criticized what they call “vertical reading,” which examines the legitimacy of (dubious) claims based on a restricted focus on a website’s surface features (e.g., URL, graphics, design, “About” page; Breakstone et al., Citation2018). In contrast, they pose an alternative to the traditional media literacy approaches of checklists and close reading by outlining the “lateral reading” of professional fact-checkers. Fact-checkers, they suggested, read “across” rather than “down,” almost immediately leaving the focal website by opening “new browser tabs on the horizontal axis of their browsers” to see what other sources said about the original site’s author or sponsoring organization (Wineburg & McGrew, Citation2019, p. 19). By scrutinizing the claims of websites, facts, and “fake news” through the claims of other websites, they suggested, readers are better equipped to determine the truth.

In connecting readers to a range of information sources, “lateral reading” certainly offers more robust strategies than earlier media literacy practices, which often evaluated texts and text features in isolation. However, in retaining an emphasis on “literacy,” it also begs the question: does each new lateral reading not simply engender another lateral reading to check those claims, ad infinitum until readers reach some political “ground zero” (be that the New York Times, Wikipedia, or Breitbart News)? Wineburg and his team’s approach, in other words, assumes that bedrock reality is reachable through the capacities of lateral readers to navigate the representational features of networked texts. As such, it elides the performative relations that condition those texts, their networks, and the ways readers encounter both: material hardware, aesthetic interfaces, algorithmic architectures, and platform business models, as well as the human labour and natural resources required to create and sustain them (Nichols & Stornaiuolo, Citation2019). The limitations of “literacy” to account for such dynamics is not a new discovery. It is the subject of a growing literature that considers how literacy research might better attend to the non-local, non-representational, and non-human relations imbricated in acts of reading and writing (e.g., Brandt & Clinton, Citation2002; Leander & Burris, Citation2020; Nichols & Campano, Citation2017; Snaza, Citation2019). Building on such work, we suggest that the complexities of the emerging media landscape are inclusive of, but not limited to, the concerns of “literacy.” As such, our orientation to media pedagogy may require a wider repertoire of resources than “literacy,” even in its most expansive forms, can offer.

Ecological Orientations to Media

What alternate resources might be of use in accounting for the performativity of connective technologies in media education? It is to this question that we turn for the remainder of the article. We first outline a promising trajectory in media studies and science and technology studies (STS) that has revived and extended the “environmental” idiom for thinking about media technologies. We highlight three theoretical perspectives – scale, assemblage, performativity – that guide this line of inquiry and that are already in use in curriculum studies. We then examine one model from this literature, Bratton’s (Citation2015b) “The Stack,” to consider what such an orientation might offer for media education.

Media Ecology Revisited

As we have suggested, representational practices strain to address the complex interrelations that drive media systems. In fields like media studies and science and technology studies, such limitations have led scholars to revive conceptualizations of media not as communicative modes, but as dynamic environments (Fuller, Citation2005). This recent work differs in important ways from earlier articulations of “media ecology.” Where McLuhan and Postman, at times, veered into deterministic analysis of media effects (e.g., drawing comparisons between, say, books and television as discrete “environments”), more recent ecological work emphasizes the sociomaterial entanglements that condition relations in and across media ecosystems (Peters, Citation2015). For instance, one strand of this literature, platform studies, examines digital media not through sweeping claims about “the digital environment,” but by looking inward to map the layered architectures that constitute and animate specific digital contexts (Gillespie, Citation2010; Nichols & LeBlanc, Citation2020). From this perspective, analyzing social media usage means not just attending to how users produce, share, access, and interpret messages, but tracing the wider relations of human and non-human activities that condition such practices in a given environment (Leander & Burris, Citation2020; Van Dijck, Citation2013). Doing so helps elucidate how challenges, like “fake news” – which announce themselves as discrete problems, amenable to fixed, representational solutions (e.g., lateral reading, ideology critique, or counter-messaging) – are indivisible from the material, technical, and economic currents that underwrite them.

This revived environmental idiom is not only useful for looking inward, at the internal functioning of media systems, but also for turning outward, to the wider infrastructures that make those systems usable (or inoperable), durable (or fragile) (Edwards, Citation2003) and that carry uneven consequences for the people and places caught up in their tangle (Benjamin, Citation2020; Hu, Citation2015; Mukherjee, Citation2020). While the ubiquity of common media technologies, like smartphones or wi-fi, can render their infrastructures invisible to everyday users, an “ecological” orientation can help to make such relations legible. “The cloud,” for example, may conjure images of an ephemeral ether to which devices connect, but it is densely material – made possible by wireless transmitters, telecom wiring, server farms, transoceanic cable, factory labour, and natural resource extraction (Parks & Starosielski, Citation2015). Such a perspective, then, extends earlier understandings of “media ecology” to include the ways that media technologies are not only bound up with social practices or communicative contexts, but also with the life and health of oceans, flora and fauna, geological resources, and the precarity of global climate. It is, in this sense, a more literal and expansive engagement with the “environmental” dimensions of media.

At this point, some readers might wonder what this expansive perspective has to do with post-truth politics, our original point of departure. One crucial contribution of such ecological approaches, we suggest, is that they challenge the myopic focus on isolated issues like “fake news” (or algorithmic bias, or surveillance capitalism, etc.) by situating these phenomena as contingent upshots of multi-dimensional, human and non-human ecological relations. To be sure, it would be comforting if post-truth politics could be disentangled from their material, technical, and economic substrates and confronted through representational practices alone, but the scale and complexity of the issue demands a wider frame. Our media landscape is what philosopher Morton (Citation2013) called a “hyperobject” – something viscerally real, yet so large and distributed that it forces attention towards its local and observable manifestations (e.g., “fake news”) rather than its nonlocal and invisible relations (e.g., the environment that makes “fake news” possible). Where “literacy” can be invaluable for addressing the former, “ecology” offers a metalanguage that engages the latter without discounting the contributions that other idioms, like “literacy,” might offer within this larger project. Much like activists in the 1960s used the concept of “the environment” to mobilize disparate concerns (e.g., littering, pesticides, atomic fallout) into a single situation they could work to save, “media ecology” offers a frame for consolidating the distributed concerns of the present media landscape (e.g., misinformation, algorithmic discrimination, surveillance and predictive analytics, techno-capitalism, movement work and activism, environmental extraction) into something tractable, open to new ways of seeing, analyzing, teaching about, and intervening in the relations within and across media ecosystems.

Theorizing Media Ecosystems: Scale, Assemblage, Performativity

Three theoretical perspectives are frequently used to conceptualize relations in this ecological orientation to media: scale, assemblage, and performativity. One reason we see promise in this orientation for media education is that these theoretical groundings are already present in curriculum studies, including scholarship associated with literacy and media. Adopting an ecological stance to media pedagogy, in other words, does not require the invention of a new subfield or the importing of new vocabulary from another discipline; it can be taken up through the extension of resources already at hand in education research.

The concept of scale has proliferated in educational literature (Morel et al., Citation2019), as scholars have worked to re-evaluate long-standing arguments over the supremacy of “micro” or “macro” phenomena (Stornaiuolo & LeBlanc, Citation2016; Wortham, Citation2012). Scalar perspectives help clarify the interplay of micro-interactional moments as they cohere in macro-social situations: for instance, in the way “hyperobjects” like our media landscape are instantiated by, yet irreducible to, both local and nonlocal activities. Given their scope and complexity, scholars have studied these interrelations as multi-scalar assemblages (Beighton, Citation2013; DeLanda, Citation2006). An assemblage is an arrangement of heterogeneous parts which may cohere and become participants in larger assemblages (cf. Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987): a textbook as part of the assemblage of a classroom; a graphic interface as part of the assemblage of a social network. Importantly, these heterogeneous parts can also be understood, themselves, as assemblages constituted by other heterogeneous parts operating at other scales: a textbook, for example, is not just a static object, but a confluence of authorial labour, disciplinary knowledge production, genre conventions, corporate marketing, bookbinding instruments, and copyright regulations. Assemblage theory, as articulated by DeLanda (Citation2006), allows researchers to explore the contingent process by which phenomena are temporarily stabilized in or across scales. “Fake news,” for instance, may appear as a discrete occurrence at the scale of a user-message interaction; however, the heterogeneous pieces that comprise it are distributed throughout the multi-scalar assemblages that constitute the wider media environment (hardware, software, institutions, human labour, natural resources, etc.).

Crucially, assemblage theory also disrupts long-standing reductions that associate micro-level activity with face-to-face interactions and the macro-level with some outworking of political economy or social structure (Carr & Lempert, Citation2016). DeLanda’s (Citation2006) articulation of scalar assemblages included a series of nested layers (persons and networks, organizations and governments, cities and nations), but he stressed that assemblages often traverse these designations as they consolidate their component parts. In this way, assemblages blur historical bifurcations of micro/macro, human/non-human, and nature/culture by highlighting how these categories are mutually constituted through action. It is for this reason that “assemblage theory” has been integral in curriculum studies research that, similarly, works to interrogate or dismantle such binaries (e.g., de Freitas & Curinga, Citation2015; Snaza et al., Citation2014). The centrality of action in this process is important. Assemblages are characterized by performativity: they are always in motion, producing new relations which reiteratively condition them and their future activities. Theorizations of performativity (e.g., Butler, Citation1997) have been used in education research related to race, gender, and sexuality (e.g., Boldt, Citation1996; de Lissovoy & Cook, Citation2020), but they have also contributed more generally to the critique of “representation” as a mode of political action (Dezuanni, Citation2018; Giroux, Citation2001; Leander & Rowe, Citation2006). As Barad (Citation2003) argued, the impulse to reduce multi-scalar assemblages to matters of language, text, and representational practices is understandable, but the oversimplifications that result often obscure more than they reveal. A “posthumanist performativity,” by contrast, begins from the relational dynamics that produce such phenomena as a starting point for inquiry and intervention.

In the context of media education, theories of scale, assemblage, and performativity further clarify the difference between a pedagogy that approaches post-truth politics as a matter of “literacy” or “ecology.” Where the former tacks towards strategies and practices associated with the consumption, production, or mobilization of text, the latter locates the dynamic, multi-scalar relations which condition media environments as sites for inquiry and action. There is resonance in this second orientation with emerging education research that explores the performativity of classroom technologies, like Canvas and Class Dojo (e.g., Scott & Nichols, Citation2017; Williamson, Citation2017), and the relations of national policy, algorithmic reasoning, and embodied practice that produce “racializing assemblages” in schools (Dixon-Román, Citation2016; Dixon-Román et al., Citation2020). Though such studies focus on closed systems and platform-specific environments, they gesture to the possibilities for more expansive forms of mapping that would accord with an ecological orientation to media education.

Mapping Media Ecosystems: “The Stack” as a Case

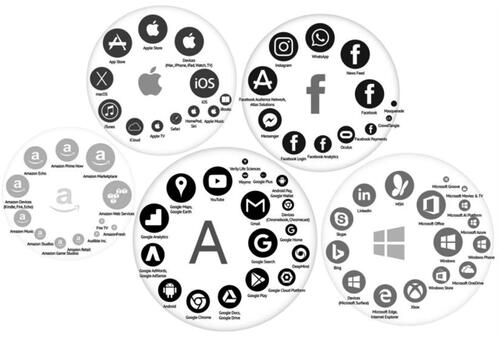

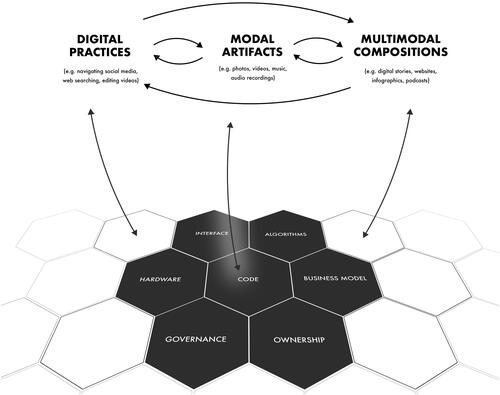

For a sense of what such mapping might look like, we can find models in the recent trend among scholars of digital media to sketch provisional “diagrams” of the relations that animate connective media environments. Van Dijck et al. (Citation2018), for example, have mapped what they term “the platform society,” charting assemblages of commercial platforms with which social and political life are increasingly entwined (). Nichols and Johnston (Citation2020), similarly, consolidate frameworks from platform studies and multimodal literacies to clarify the performative infrastructures with which observable practices, like multimodal composing, are bound (). This impulse to aestheticize network complexity is significant, we suggest, not because it produces totalizing representations of media systems (as if such a feat were possible), but because it signals a dissatisfaction with frameworks that elide the performativity of platforms. Such diagrams, then, are attempts to make visible the scales and assemblages that are overlooked when the aperture of scholarly attention to media systems is too narrow. In this section, we use one such diagram – Bratton’s “The Stack” – as a case, to consider what this widened orientation might offer to media education. We focus on Bratton’s model not because we find it to be the best, truest, or clearest map of the media ecosystem, but because it is the most expansive in the scope of what it includes in its conception of platforms, and, therefore, offers to education research and practice the broadest range of possible uses.

Figure 1. Van Dijck et al. (Citation2018) map of “The Platform Society.” Used with permission (copyright Oxford University Press).

Figure 2. Nichols and Johnston (Citation2020) map of infrastructures animating multimodal composing practices. Used with permission (copyright, the Authors).

The Stack

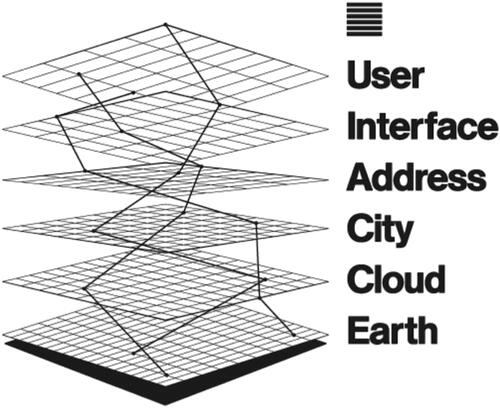

“The Stack” is a map, created by design theorist Bratton (Citation2015b), that outlines the technologies and users that interlock to form global media ecologies (). It is composed of six layers, “moving from the global to the local, from geochemical up to the phenomenological: Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface and User” (Bratton, Citation2015b, p. 66). As a diagram, The Stack helps us see relations and contingency among an ecology of human and non-human actors, layered systems and operations which overlap one another simultaneously. As a generic outline of a Stack, Bratton (Citation2014) described a profile of a user-citizen-subject (perhaps a generic person sitting with some screen) in this configuration:

Figure 3. Bratton’s (Citation2015b) diagram of “The Stack.” Used with permission (copyright MIT Press).

Using some…platform interface connected to a stable mix of IPV 4 and 6 address websites, smart objects, situated in a specific city, connected to a public/private Wi-Fi jurisdiction governed by application architectures of the global cloud platform such as Google and the Earth layer, drawing itself local hydro-electric energies as well as the coal plants that power the servers, accessed by its users. That we can say is our generic column.

Consequently, one plug into The Stack invokes all of its components, up and down the Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface and User layers. The performativity of The Stack is such that it cannot operate at one layer without assembling layers at other scales – “From subterranean cloud computing infrastructure to hand held and embedded interfaces, planetary-scale computation can be understood as an accidental megastructure…a global Stack” (Bratton, Citation2015a, p. 35). Over their lifetime, users may occupy millions of different columns, orchestrating by algorithm the organizational logics of each. In full, The Stack is a temporary assemblage:

At the top of any column, a User (animal, vegetable, or mineral) would occupy its own unique position and from there activate an Interface to manipulate things with particular Addresses, which are embedded in the land, sea, and air or urban surfaces on the City layer, all of which can process, store, and deliver data according to the computational capacity and legal dictates of a Cloud platform, which itself drinks from the Earth layer’s energy reserves drawn into its data centers. (Bratton, Citation2015a, p. 68)

Bratton’s Stack diagram offers an ecology of digital platforms, users, interfaces, and systems, helping us see connectedness up and down the layers. This map invokes a host of additional ethical, political, and social quandaries. Much of the existing, representation-oriented research in media literacy tends to focus on the interplay between the first two layers (a User engaging an Interface for semiotic work). Retaining this crucial dimension, and its typical focus on “literacy,” what other questions might this leave open for media education curricula and research? The Stack, we argue, makes new processes legible, still allowing us to animate the ideational aspects of messaging and circulation from User to Cloud or the phenomenology of a User scrolling the Interface of an operating system (Burnett et al., Citation2014) while demanding we look up and down the layers to see the full work of the column. For those keen on issues of digital media literacy, each layer of The Stack follows its own forms of governance and jurisdictional logics, mutually communicable with one another; what each layer of The Stack touches, it tries to organize along these lines. The Stack, while an organizational heuristic, is also fundamentally political.

Reading in The Stack

Returning to our example of the Stanford History Education Group’s vertical and lateral reading (Wineburg & McGrew, Citation2019), what might The Stack make visible that traditional conceptions of “literacy” cannot capture? Should we wish to think ecologically, how might The Stack allow us to see the imbrication of human and non-human processes and actors? As an experiment, we can imagine a traditional User, perhaps a high school student in a Philadelphia public school classroom engaging some accessible interface made available by the school (e.g., Google News) to read a questionable story in the vein of Wineburg’s concern with “fake news” (about the contemporary immigration crisis at the US-Mexico border or climate change). In this hypothetical, the assemblage of The Stack stabilizes for a moment: the User on her Chromebook clicks on Google News’ graphical user Interface, made accessible by the urban school district’s costly Comcast broadband connection, pouring data and information into Google’s US-based Cloud platform which, in turn, tailors the User’s preferences based on machine-learning algorithms, drawing Earth-layer electrons from the nearby Limerick Nuclear Generating Power Station. In other words, more than a representational engagement with reading a news story or website, a conception of The Stack elucidates multiple, performative layers – geopolitical, infrastructural, ecological – that are initiated simultaneously.

Carrying this forward, we might look to the bottom of the column to what Bratton called the Earth layer, perhaps the most overlooked portion of digital infrastructure. Media literacy (of the classroom variety) has historically bypassed questions of environmental impact at the level of infrastructure (i.e., apart from ideational pro-environment or anti-climate-denialism messaging). In our Wineburg example, thinking traditionally might include scrutinizing the environmental claims of a particular website, then looking laterally to substantiate them by way of other websites and their concomitant environmental claims. Bratton (Citation2015a) suggested this approach, however, looked only to a User and Interface assemblage (and typically only to the User and the messaging made available on the Interface). Instead, Bratton urged the “foregrounding of the geological substrate of computational hardware and of the geopolitics of mineral resource flows of extraction, consumption, and discarding” (p. 70). In addition to the massive power-dependent capacities of our hardware and software are the waste products of our infrastructure, our “digital rubbish” (Gabrys, Citation2014; see also Grusin, Citation2015), the municipal refuse of some 400 million consumer electronic products which make their way into the landfill each year in the United States. Where we think of the ephemerality of the digital (clouds, platforms, and documents as bits and bytes), it is “deep time resources” (Parikka, Citation2014) – cobalt, gallium, antimony, platinum, palladium – that make technological ephemerality possible.

Ethics in The Stack

These issues raise no easy ethical questions with regards to classroom or curricular action, particularly as they elude the representational solutions offered in traditional media literacy. The Stack is a hyperobject that we can only touch (or “read”) a small part of at a time. While our (post)industrial technological advancements have put us on a path towards anthropocentric terraforming and climate catastrophe (and we may indeed critically read about and mobilize counter-messages against with the aid of digital platforms, tools, and literacy practices), it is only by virtue of the massive interlocking technological infrastructure of satellites, weather balloons, temperature-sensitive ocean buoys, and research architecture that we are able to measure, study, or recognize this phenomenon in the first place (Latour, Citation2013). In other words, there are no unconstrained actors or uncompromised positions in The Stack: students may write powerful treatises about environmental protection, but they have little choice but to do so using servers that gulp electrons from a hydroelectric dam 50 miles away, using district-issued computers whose manufacture slowly poisons an underwater aquifer in Shenzhen, China (cf. Standaert, Citation2019). In clarifying these relations, Bratton’s diagram does not repudiate “literacy” as a valuable political practice, but does suggest that its capacities are conditioned by the performativity of the wider ecosystem in which it operates.

Bratton’s Cloud layer provides a further illustration of the ethical challenges wrought by the Stack and the limits of “literacy” as a means of addressing them. Bratton (Citation2015b) argued that contemporary media research lacks “a robust and practical theory of the political design of platforms” (p. 44), and as such, misses fundamental questions of “platform sovereignty” that arise whenever we use Cloud-based applications like Google or Facebook. “Cloud Polis,” Bratton’s (Citation2015b) term for the transnational political posturing of tech companies and their usurpation of typical governmental functions (with or without our consent), “is populated by hybrid new geographies, new governmentalities, awkward jurisdictions” which produce new “imagined communities, group allegiances, and ad hoc patriotism” (p. 122). More simply, the Cloud reflects a non-territorial politics, beyond the borders and regulations of any single nation-state, for which we must now account.

This complicates how we might think about the content of any given platform – and, by extension, what it means to critically read or respond to such messages. Bratton’s Cloud Polis operates with a governing logic that does not just connect users and messages, but produces this connectivity through apparatuses of data extraction, aggregation, and optimization. This, in turn, bolsters the value and reach of such platforms, which can be translated into political leverage for circumventing regulation and re-writing multinational law – integral processes in what scholars have termed “platform capitalism” (Srnicek, Citation2017) and “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, Citation2019). It is in these performative relations, which often occur beneath the threshold of users’ perceptions, that a pernicious object like “fake news” takes on resonance less as an informational text and more as an ecological commodity: circulating from the mind of a Macedonian propagandist to the screen of an iPhone in a US Midwest home to the resulting clickdata which is recursively folded back into the production of future propaganda – all mediated by the highly personalizing, data-harvesting algorithms of the platform itself.

What does it mean to promote “lateral reading” in schools when each time a user queries Google’s search engine, they are not only presented with results inflected by prior search histories and algorithmically determined weighting, but are also, themselves, grafted into the algorithm’s training dataset, which will be used to condition the searches of future “lateral readers”? What does it mean to encourage (or even mandate, as is the case in many contemporary classrooms) the production and circulation of critical counter-messaging via Google Classroom or social media when doing so further normalizes the “increasingly inescapable material-extraction operation” that converts these activities into profit and power for platforms and their owners (Zuboff, Citation2019, p. 80)? There are no easy answers to such questions. But thinking with The Stack, and similar diagrams of the emerging media ecosystem, helps to make such questions and their stakes legible to education researchers and practitioners. Doing so, we suggest, opens avenues for coalitional responses that the idiom of “literacy” in media education has yet to produce, but that an ecological orientation might make possible. It is to these possibilities that we now turn.

Towards a Civic Media Ecology

The performativity of The Stack – and similar diagrams of the multi-scalar assemblages at work in our emergent media ecosystem – present significant challenges for curriculum and teaching. In Bratton’s depiction, each keystroke in a classroom is shot through with geopolitical, infrastructural, and environmental relations. As with other (related) hyperobjects, like climate change and capitalism, the scope of these relations can easily lead to fatigue or nihilism. This dynamic helps clarify the enduring appeal of the “literacy” idiom in media education. It allows educators to locate inquiry and instruction in the more concrete and discernible dynamics of the media environment: how users consume, produce, and mobilize texts. As we have shown, however, this emphasis on representational practices can obscure the nonlocal, non-human relations that help to constitute and animate the digital media environment. In doing so, it also undermines the larger project of media education: absent an accounting of such relations, media pedagogy cannot address, much less intervene in, the dynamics that produce “fake news,” “post-truth” politics, or other public crises for which media literacy is regularly invoked as a solution.

As the current argument about media literacy is now giving rise, on one hand, to the charge that the concept has outlived its usefulness (e.g., danah boyd’s SXSW keynote) and, on the other, to calls for more expansive “literacies” to be housed under the term’s umbrella (e.g., data, information, news, or “critical” variations that engage the hierarchies and political economy of each), we contend that the issue is not media education itself, but the limitations of “literacy” as the guiding idiom for understanding and engaging media systems in curriculum and instruction. Rather than extending the literacy idiom wider and wider – to, or even beyond, its breaking point – we suggest that a more expansive repertoire of resources is needed. One that offers possibilities for addressing both the representational and the performative politics of media. We have suggested that the idiom of “ecology” – which has a lineage in media pedagogy and is now being revived and reworked in the fields of media and science studies – offers a promising path forward. It is in the interest of merging such perspectives with existing education research that we offer civic media ecology as an orientation for confronting the pedagogical challenges wrought by new media environments. This term acknowledges the generative contributions of work that continues to make use of “literacy” in exploring the contours of representational media and civic action (e.g., Mihailidis, Citation2018), while also gesturing to the possibilities for exploring the performative environments in which such activities are embedded. As such, this stance is not meant to draw boundaries around a new field of inquiry, but to open new coalitional engagements across curriculum studies that might yield diverse combinations of tactics for teaching and learning with, within, and against media ecosystems.

“Civic” Media Ecology

Our coarticulation of “civics” alongside an environmental orientation to media serves several purposes. First, it helps to distinguish the forms of “media ecology” now unfolding in media and science studies from the pedagogical and curricular projects that might be informed by, but are not the focus of, such scholarship. While media researchers may, for instance, trace the relations between algorithmic reasoning and racialized surveillance, these contributions to theory-building are not always immediately translatable into forms of inquiry and action amenable for use in schools or informal learning contexts. A “civic” orientation, then, can help educators to identify those performative dynamics of the media environment whose inclusion in the curriculum might augment or replace existing disciplinary content and, in doing so, better grapple with the conditions in which content-area knowledge now circulates. Algorithmic surveillance, for example, could be explored across disciplines, as a historical emergence, a subject of literary exploration, and an expansion of mathematical rationality into forms of life once spared from its reach. And importantly, each of these vantage points might offer different resources for understanding and intervening in the underlying and interrelated forces that constitute contemporary surveillance practices. Rather than treating public crises, like surveillance or “fake news,” as discrete problems of uninformed users or individual bad actors, we suggest that a stance of civic media ecology helps prevent the premature foreclosure of inquiry into the wider relations that animate these observable phenomena and what possibilities they might hold for teaching and learning.

A second purpose for invoking “civics” is that we see this orientation as contributing to the existing research on civic education with regards to where civic action might reside. “Civics” as a curriculum and a concept has undergone its own recent revolution in education (Levine, Citation2015) – away from explicit instruction about the benefits of incremental liberalism and its longstanding institutional structures (Shapiro & Brown, Citation2018) and towards a “new” or “lived” civics focussed on direct political action (Korbey, Citation2019). While it is outside the scope of this article to conduct a full review of these discussions, a central feature of such developments has been a move to foreground community transformation and digital activism (Cohen et al., Citation2018). Responding to and extending such work, Mirra and Garcia (Citation2020) called for “civic literacies” anchored in youth’s capacities to articulate radical futures, often through Black speculative work that evokes worlds outside the logics of systemic racism, using the “unique affordances of disciplinary literacy practices” (p. 302) of reading, writing, and representing in a manner that is both pragmatic and aesthetic. Here we wish to suggest that, while projects in “new civics” and “civic literacies” rightly centre youth practices and radical imaginaries, these are nevertheless undergirded by digital substrata that link such “literacies” to more expansive forms and scales of activity. In Bratton’s terms, they are supported and underwritten by a temporary Stack that overdetermines the circulation and uptake of civic messages. These projects simultaneously plug any “user” into a bevy of other human and non-human actors (e.g., algorithms, search engine optimizations, Earth-layer extraction projects, Cloud-politics of click-level surveillance and national privacy laws, etc.). This raises pressing, if vexing, questions for civic learning and action. To take just one example: what does it mean when conventionally straightforward acts of civic response, like participating in a protest, may now involve one’s image or geolocation being absorbed into the training data that will be used to algorithmically predict and police future protests?

The performativity of such systems offers no easy answers for civic education, but it does point towards a wider field of action for civic potentials. If the problem of “fake news” is irreducible to the actions of individual users (be it the skillset of a tech-savvy youth, the financial or political interests of an independent or corporate propagandist, or the color-blind liberalism of a Facebook content-moderator or coder) and its resonance extends to scales that traverse the boundaries of nation-states and even threaten planetary health (e.g., in the activities of Bratton’s “Cloud Polis” and Earth-layer), then a civic media ecology can help us to think across such relations and to forge coalitional responses that attend to their varied convergences. We see potential, for example, in such a stance bringing together the rich literatures of civic, media, and literacy education with those of environmental and planetary pedagogies (Kahn, Citation2008) – all of which have addressed issues of “post-truth” politics, though rarely in conversation with one another – much less, coordinating diverse sets of tactics for civic response (e.g., Bacon, Citation2018; Breakstone et al., Citation2018; Goering & Thomas, Citation2018; Misiaszek, Citation2020). In this way we also see such a stance helping to rework “civic” understandings to the circumstances in which we find ourselves: where the need for organizing and action are both micro and macro (from the scale of code and hardware to transnational law and commerce) and where the compromised tools available to us can reinscribe localized and globalized forms of oppression (from discriminatory algorithms to the “slow violence” of environmental catastrophe on those in the Global South; cf. Nixon, Citation2011). In offering a metalanguage to engage such relations, we see a stance of civic media ecology as inviting new combinations of theories, methods, and interventionist tactics that are attuned to the complexities before us.

While the scale of these issues is dizzying and even, at times, debilitating, we see this orientation of civic media ecology as, ultimately, hopeful. More than simply mapping the relations that constitute the media ecosystem and documenting the innumerable sources of exploitation at work therein, the performativity of the system suggests that its contours are not fixed. It is open to new configurations. In other words, civic media ecology recognizes that media education need not be limited either to defensive strategies against commercial interests and propaganda or to powerful forms of counter-messaging; it can also promote investigation and action that might allow the ecosystem itself to become otherwise – in ways that are more equitable and just. Bratton (Citation2015b) stressed this sense of possibility when he noted that The Stack we have inherited is not settled or determinative; he concludes his book with an outline of “The Stack to Come” – the environmental, economic, technical, and social relations that do not yet exist, but could. Here again, we see the potential of the “civic”: while identifying and responding to forms of misinformation and misrepresentation is important, media education might also take up the more expansive challenge of conceptualizing how such relations might be altered – a form of radical imagining already at work in civic, media, and literacy literatures (Mirra & Garcia, Citation2020; Nichols & Coleman, Citation2020; Perry, Citation2020), but that is rarely extended to the sociotechnical systems in which we are embedded.

Conclusion

An orientation of civic media ecology does not obviate the range of meaningful work that occurs in the “literacy” idiom, or the concerns that have traditionally been part of the popular project of “media literacy.” There is profoundly important work being done that explicitly engages the representational politics of media and the powerful counter-messages through which youth respond to such narratives and depictions (e.g., Baker-Bell et al., Citation2017; Mihailidis, Citation2018; Morrell, Citation2012; Thomas & Stornaiuolo, Citation2016). Indeed, our own work as literacy researchers interested in digital media has drawn heavily on and contributed to such conversations (e.g., Stornaiuolo & LeBlanc, Citation2014; Stornaiuolo & Nichols, Citation2018). However, even as the theories and methods that animate such scholarship provide generative responses to particular dimensions within our media environment, they are not endlessly adaptable to the full range of its scales and the performativity of its relations. Attending to such dynamics requires a more expansive repertoire of resources and tactics – one that is inclusive of, but not limited to, literacy.

Shifting the idiom of media education from “literacy” to “ecology” not only offers this expansive repertoire, but it does so by reviving and reworking an already-existing orientation from the history of media pedagogy and linking it with emerging theories in media and science studies. In the process, this stance of civic media ecology, we suggest, provides a pathway through the present gridlocks in media education by shifting the terms of debate: from a pedagogy focussed on the representational challenges of “fake news” and “post-truth” politics to one attuned to the performativity of platforms that produce not just the media environment that is, but also, through civic inquiry and activism, those to come and that might yet be.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adorno, T. (1950). The authoritarian personality: Studies in prejudice. Harper.

- Alvermann, D. E., Moon, J. S., & Hagood, M. C. (2018). Popular culture in the classroom. Routledge.

- Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., & Murphy, C. (2012). Polarized political communication, oppositional media hostility, and selective exposure. The Journal of Politics, 74(1), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238161100123X

- Aufderheide, P. (1992). Media literacy: A report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Aspen Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED365294

- Bacon, C. K. (2018). Appropriated literacies: The paradox of critical literacies, policies, and methodologies in a post-truth era. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26(147), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3377

- Baker-Bell, A., Stanbrough, R. J., & Everett, S. (2017). The stories they tell: Mainstream media, pedagogies of healing, and critical media literacy. English Education, 49(2), 130–152.

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Beighton, C. (2013). Assess the mess: Challenges to assemblage theory and teacher education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(10), 1293–1308. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.731539

- Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity. Social Forces, 98(4), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz162

- Boldt, G. (1996). Sexist and heterosexist responses to gender bending in an elementary classroom. Curriculum Inquiry, 26(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.1996.11075449

- boyd, d. (2018). What hath we wrought? [Video]. SXSW Education. https://www.sxswedu.com/news/2018/watch-danah-boyd-keynote-what-hath-we-wrought-video/

- Brandt, D., & Clinton, K. (2002). Limits of the local: Expanding perspectives on literacy as a social practice. Journal of Literacy Research, 34(3), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3403_4

- Bratton, B. (2014, October). The Stack: Design and geopolitics in the age of planetary-scale computing [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IXan6TvMqgk

- Bratton, B. (2015a). Cloud megastructures and platform utopias. In J. Geiger (Ed.), Entr’acte: Performing publics, pervasive media, and architecture (pp. 35–51). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bratton, B. (2015b). The Stack: On software and sovereignty. MIT Press.

- Breakstone, J., McGrew, S., Smith, M., Ortega, T., & Wineburg, S. (2018). Why we need a new approach to teaching digital literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(6), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718762419

- Buckingham, D. (1993). Going critical: The limits of media literacy. Australian Journal of Education, 37(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494419303700203

- Buckingham, D. (1998). Media education in the UK: Moving beyond protectionism. Journal of Communication, 48(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02735.x

- Buckingham, D. (2013). Media education: Literacy, learning, and contemporary culture. Polity.

- Buckingham, D. (2020). The media education manifesto. Polity.

- Bulger, M., & Davison, P. (2018). The promises, challenges, and futures of media literacy. Data & Society Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-1-1

- Burnett, C., Merchant, G., Pahl, K., & Rowsell, J. (2014). The (im)materiality of literacy. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 35(1), 90–103.

- Butler, J. (1997). Excitable speech: A politics of the performative. Routledge.

- Campano, G., Nichols, T. P., & Player, G. (2020). Multimodal critical inquiry: Nurturing decolonial imaginaries. In E. Moje, P. Afflerbach, P. Enciso, & N. K. Lesaux (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 5; pp. 137–152). Routledge.

- Carr, E., & Lempert, M. (2016). Scale: Discourse and dimensions of social life. University of California Press.

- Christ, W., & Potter, W. J. (1998). Media literacy, media education, and the academy. Journal of Communication, 48(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02733.x

- Cohen, C., Kahne, J., & Marshall, J. (2018). Let’s go there: Race, ethnicity and a lived civics approach to civics education. University of Chicago.

- Connolly, K., Chrisafis, A., McPherson, P., Kirchgaessner, S., Haas, B., Phillips, D., Hunt, E., & Safi, M. (2016, December). “Fake news”: An insidious trend that’s fast becoming a global problem. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/dec/02/fake-news-facebook-us-election-around-the-world

- de Freitas, E., & Curinga, M. X. (2015). New materialist approaches to the study of language and identity: Assembling the posthuman subject. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2015.1031059

- de Lissovoy, N., & Cook, C. B. (2020). Active words in dangerous times: Beyond liberal models of dialogue in politics and pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry, 50(1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2020.1735922

- DeLanda, M. (2006). A new philosophy of society: Assemblage and social complexity. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

- Dezuanni, M. (2018). Minecraft and children’s digital making: Implications for media literacy education. Learning, Media, and Technology, 43(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1472607

- Dixon-Román, E. (2016). Algo-ritmo: More-than-human performative acts and the racializing assemblages of algorithmic architectures. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 16(5), 482–490.

- Dixon-Román, E., Nichols, T. P., & Nyame-Mensah, A. (2020). The racializing forces of/in AI educational technologies. Learning, Media, and Technology, 45(3), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1667825

- Edwards, P. (2003). Infrastructure and modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems. In T. Misa & A. Feenberg (Eds.), Modernity and technology (pp. 185–226). MIT Press.

- Fuller, M. (2005). Media ecologies. MIT Press.

- Gabrys, J. (2014). Powering the digital: From energy ecologies to electronic environmentalism. In R. Maxwell, J. Raundalen, & N. L. Westberg (Eds.), Media and the ecological crisis (pp. 3–18). Routledge.

- Gallup. (2018). American views: Trust, media, and democracy. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/reports/american-views-trust-media-and-democracy

- Gavin, N. T. (2018). Media definitely do matter: Brexit, immigration, climate change and beyond. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(4), 827–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148118799260

- Gencarelli, T. (2006). The missing years: Neil Postman and the new English book series. Explorations in Media Ecology, 5(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1386/eme.5.1.45_1

- Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364.

- Giroux, H. (2001). Cultural studies as performative politics. Cultural Studies <–> Critical Methodologies, 1(1), 5–23.

- Goering, C., & Thomas, P. (Eds.). (2018). Critical media literacy and “fake news” in post-truth America. Brill Sense.

- Grusin, R. (2015). Introduction. In R. Grusin (Ed.), The nonhuman turn (pp. vii–xxix). University of Minnesota Press.

- Hall, S., & Whannel, P. (1964). The popular arts. Pantheon.

- Hobbs, R. (1994). Pedagogical issues in U.S. media education. Communication Yearbook, 17, 353–356.

- Hobbs, R. (1998). The seven great debates in the media literacy movement. Journal of Communication, 48(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02734.x

- Hobbs, R. (2007). Reading the media in high school: Media literacy in high school English. Teachers College Press.

- Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. Aspen Institute.

- Hobbs, R. (2018a). Media literacy foundations. In R. Hobbs & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), International encyclopedia of media literacy (pp. 1–19). John Wiley.

- Hobbs, R. (2018b, March). Freedom to choose: An existential crisis: A response to boyd’s ‘What hath we wrought?’ Medium. https://medium.com/@reneehobbs/freedom-to-choose-an-existential-crisis-f09972e767c

- Hobbs, R., & McGee, S. (2014). Teaching about propaganda: An examination of the historical roots for media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 6(2), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2016-06-02-5

- Hoechsmann, M., & Poyntz, S. R. (2012). Media literacies. Wiley.

- Hofstadter, R. (1963). Anti-intellectualism in American life. Vintage.

- Hoggart, R. (1958). The uses of literacy. Transaction.

- Horkheimer, M. (1950). The lessons of fascism. In H. Cantril & United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Eds.), Tensions that cause wars (pp. 209–242). University of Illinois Press.

- Hu, T.-H. (2015). A prehistory of the cloud. The MIT Press.

- Journell, W. (2019). Unpacking fake news: An educator’s guide to navigating the media with students. Teachers College Press.

- Judis, J. (2018). The nationalist revival: Trade, immigration, and the revolt against globalization. Columbia Global Reports.

- Kahn, R. (2008). From education for sustainable development to ecopedagogy. Green Theory and Praxis: The Journal of Ecopedagogy, 4(1), 1–14.

- Kellner, D. (1998). Multiple literacies and critical pedagogy in a multicultural society. Educational Theory, 48(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1998.00103.x

- Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2007). Critical media literacy, democracy, and the reconstruction of education. In D. Macedo & S. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Media literacy: A reader (pp. 3–23). Peter Lang.

- Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: Media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media, Culture, & Society, 33(2), 211–221.

- Korbey, H. (2019). Building better citizens: A new civics education for all. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Latour, B. (2004). Why has critique run out of steam? Critical Inquiry, 30(2), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

- Latour, B. (2013). An inquiry into modes of existence. Harvard University Press.

- Leander, K., & Burris, S. (2020). Critical literacy for a posthuman world: When people read, and become, with machines. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1262–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12924

- Leander, K., & Rowe, D. (2006). Mapping literacy spaces in motion: A rhizomatic analysis of a literacy performance. Reading Research Quarterly, 41(4), 428–460. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.41.4.2

- Leavis, F. R., & Thompson, D. (1933). Culture and environment: The training of critical awareness. Chatto & Windus.

- Levine, P. (2015). We are the ones we have been waiting for: The promise of civic renewal in America. Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, J., & Jhally, S. (1998). The struggle over media literacy. Journal of Communication, 44(3), 109–120.

- Livingstone, S. (2004). Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies. The Communication Review, 7(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420490280152

- Livingstone, S. (2008). Engaging with media – A matter of literacy? Communication, Culture, & Critique, 1(1), 51–62.

- Luke, A. (2013). Regrounding critical literacy: Representation, facts, and reality. In M. R. Hawkins (Ed.), Framing languages and literacies: Social situated views and perspectives (pp. 136–148). Routledge.

- Marcus, S., Love, H., & Best, S. (2016). Building a better description. Representations, 135(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2016.135.1.1

- Mason, L. (2016). McLuhan’s challenge to critical media literacy: The city as classroom textbook. Curriculum Inquiry, 46(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2015.1113511

- Mason, L., Krutka, D., & Stoddard, J. (2018). Media literacy, democracy, and the challenge of fake news. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 10(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-2-1

- Masterman, L. (1980). Teaching about television. Macmillan.

- McGrew, S., Ortega, T., Breakstone, J., & Wineburg, S. (2017). The challenge that’s bigger than fake news: Civic reasoning in a social media environment. American Educator, 41(3), 4–11.

- Mihailidis, P. (2012). News literacy: Global perspectives for the newsroom and the classroom. Peter Lang.

- Mihailidis, P. (2018). Civic media literacies. Routledge.

- Mirra, N., & Garcia, A. (2020). “I hesitate but I do have hope”: Youth speculative civic literacies for troubled times. Harvard Educational Review, 90(2), 295–321. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-90.2.295

- Misiaszek, G. W. (2020). Countering post-truths through ecopedagogical literacies: Teaching to critically read ‘development’ and ‘sustainable development.’ Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(7), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1680362

- Morel, R. P., Coburn, C., Catterson, A. K., & Higgs, J. (2019). The multiple meanings of scale: Implications for researchers and practitioners. Educational Researcher, 48(6), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19860531

- Morrell, E. (2012). 21st‐century literacies, critical media pedagogies, and language arts. The Reading Teacher, 66(4), 300–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01125

- Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mukherjee, R. (2020). Radiant infrastructures: Media, environment, and cultures of uncertainty. Duke University Press.

- New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92.

- Nichols, T. P., & Campano, G. (2017). Literacy and post-humanism. Language Arts, 94(4), 245–251.

- Nichols, T. P., & Coleman, J. J. (2020). Feeling worlds: Affective imaginaries and the making of ‘democratic’ literacy classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(2), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.305

- Nichols, T. P., & Johnston, K. (2020). Rethinking availability in multimodal composing: Frictions in digital design. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(3), 259–270.

- Nichols, T. P., & LeBlanc, R. J. (2020). Beyond apps: Digital literacies in a platform society. The Reading Teacher, 74(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1926

- Nichols, T. P., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2019). Assembling ‘digital literacies’: Contingent pasts, possible futures. Media and Communication, 7(2), 1–11.

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

- Ong, W. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Routledge.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. (1987). Media literacy.

- Pangrazio, L., & Selwyn, N. (2019). Personal data literacies: A critical literacies approach to enhancing understandings of personal digital data. New Media & Society, 21(1), 419–437.

- Parikka, J. (2014). The Anthrobscene. University of Minnesota Press.

- Parks, L., & Starosielski, N. (2015). Signal traffic: Critical studies of media infrastructures. University of Illinois Press.

- Perry, M. (2020). Unpacking the imaginary in literacies of globality. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(4), 574–586.

- Peters, J. D. (2015). The marvelous clouds: Toward a philosophy of elemental media. University of Chicago Press.

- Postman, N. (1961). Television and the teaching of English. National Council for Teachers of English.

- Scott, J., & Nichols, T. P. (2017). Learning analytics as assemblage: Criticality and contingency in online education. Research in Education, 98(1), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523717723391

- Shapiro, S., & Brown, C. (2018). The state of civics education. Center for American Progress.

- Snaza, N. (2019). Animate literacies: Literature, affect, and the politics of humanism. Duke University Press.

- Snaza, N., Appelbaum, P., Bayne, S., Carlson, D., & Morris, M. (2014). Toward a posthumanist education. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 30(2), 39–55.

- Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Polity.

- Standaert, M. (2019, July). China wrestles with the toxic aftermath of rare earth mining. Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-wrestles-with-the-toxic-aftermath-of-rare-earth-mining

- Stornaiuolo, A., & LeBlanc, R. J. (2014). Local literacies, global scales. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(3), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.348

- Stornaiuolo, A., & LeBlanc, R. J. (2016). Scaling as a literate activity: Mobility and educational inequality in an age of global connectivity. Research in the Teaching of English, 50(3), 263–287.

- Stornaiuolo, A., & Nichols, T. P. (2018). Making publics: Mobilizing audiences in high school makerspaces. Teachers College Record, 120(8), 1–38.

- Street, B. V. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, E. E., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the self: Bending toward textual justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.313

- Turner, F. (2013). The democratic surround: Multimedia and American liberalism from World War II to the psychedelic sixties. University of Chicago Press.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2011). Media and information literacy curriculum for teachers.

- Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.