Abstract

To read this article, it is important to know that I am a transnational (but not transracial) adoptee and that my Taiwanese birth mother hoped my adoption would give me a “better” life in the United States. I present three interconnected arguments that introduce the concept of a nomencurriculum. The first argument is that my and others’ names are infused with multiple ideologies and aspirations. Second, I contend that names are part of a lived curriculum. Lastly, I assert that names are an analytical lens that allows me to examine lived curricula that emerges from names and namings. I do so by studying my own three namings using AsianCrit and decolonial analyses as well as how each (my English given name, Cantonese given name, and Mandarin given/chosen name) represents attempts at assimilation, erasure, and reclamation, respectively. I use critical race archival analyses and rememory of documents from my own adoption case files from Taipei District Court, the Superior Court of California, and a family study of my parents—the only extant records of my namings. Through my examination of my lived and school curricula, I highlight the global contexts and power dynamics that impact students’ self-knowledge and their resistance against official discourses. This article, then, elucidates the analytic possibility of a nomencurriculum, which contributes to the field of curriculum studies by considering the power of names and namings. The nomencurriculum provides a way for individuals to engage with their lived curricula within formalized educational spaces that tighten their senses of self and often reinforce state-sanctioned narratives.

You might only see a pile of boring forms and numbers, but I can see a story. With nothing but a stack of receipts, I can trace the ups and downs of your lives. I can see where this story’s going and it doesn’t look good.Footnote1

It took me 22 years to learn to write my name. Not the name that appears atop this article, or the one that appears on every form I fill out, but the birth name that a California superior court form stripped me of. In summer 1995, fears of military conflict between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan were at their highest in a half century. Against this backdrop, my birth mother gave me up for adoption to a Chinese American family, seeking “a better life” for me amid the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. This was a decision she called the hardest of her life. Yet, my transnational adoption story was, on paper, uncomplicated; some would call it “ideal.” I had the privilege of an expeditious pathway to US citizenship and “naturalization” in part because I was adopted through a Catholic organization in Taiwan with missionary roots. For another, I was adopted by an upper-middle class Chinese American family and was spared having the awkward conversations many transracial adoptees have with their parents about why they look different from their parents (Louie, Citation2015). I was privileged with an expeditious pathway to citizenship and grew up in San Francisco, California—home to vibrant Asian diaspora communities. I even reunited with my birth mother both in Taipei and San Francisco in 2017 and 2019. Around this time, I began to wonder about my birth name.

My education in schools governed by Catholic doctrine taught me to answer to, and clumsily write, my English name only. I later learned that I, in fact, have three names: 1) a Mandarin name given by my birth mother (張/陳創庭); 2) an English name (Kyle) by which you may come to know me; and 3) a Cantonese name given to me by a community elder when I was “naturalized” (張玉庭). My English name erased my Mandarin birth name, which I encountered later in my life after years of learning fragments of my adoption story; my Cantonese name became my “official Chinese name” signifying belonging in my adoptive family. I feel haunted by my names—especially in that my English name, when spoken, calls attention to phonetic stereotypes (namely “L deficiency”) associated with Asian diasporas. This made me hate the sound of my name—partially out of guilt for some family members’ struggle to pronounce it, and partially because it sounded misfit to my body. In this way, my names and namings reflect the tangle of assimilation, erasure, and reclamation and offer an analytic possibility that helps to locate and resist the violence of names and namings that circulates through people’s lived experiences.

When I heard the above epigraph, spoken by Deirdre Beaubeirdre (Jamie Lee Curtis), an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) case worker in the film Everything Everywhere All At Once (Everything Everywhere; Kwan & Scheinert, Citation2022), I thought about the number of interactions with nation-states that shaped my journey from a Taiwanese orphanage to our modest San Francisco home. As Deirdre sat in a drab cubicle staring down Evelyn Quan Wang (Michelle Yeoh) threatening a tax audit of her family’s laundromat, Evelyn discovers that there are many parallel universes between which she can travel to access alternate experiences, memories, and skills. As I watched Everything Everywhere, I saw in the circulation of these multiple universes an analogy for the ways global power structures can appear as a tangle of ideologies long-abstracted by and dislocated from the places that empowered the colonial-imperial powers to enact violence through mere paperwork. Yet, studying this paperwork, especially the violence of names and (re-/mis-)naming(s), makes visible the movements and operations of these power structures.

In Everything Everywhere, the multiverse is threatened by Evelyn’s daughter Joy Wang/Jobu Tupaki (Stephanie Hsu) who is forced to experience all these simultaneous universes at once. In the conflicts within the Wang family and their many parallel existences, the film questions the linearity of relationships and growth, all while being a story of a nuclear US family told through the evolution of Joy and Evelyn’s relationship. Deirdre Beaubeirdre’s quote helped me think about the multiple existences that Joy/Jobu and Evelyn live—and the multiple existences I (could have) lived had a few pieces of paperwork been filled out differently. My State of California issued delayed birth certificate, for one, binds me to the name I am forced to answer to—replacing my birth name and marking me with a swirl of imperial and colonial ideologies. That is why I needed more than two decades to learn to write my name.

The school curriculum, though, is little help in addressing the decontextualized, ahistorical erasures of communities of Color that are visible in the violent misnaming of racialized children in schools (Bucholtz, Citation2016). In fact, I argue, curricula of violence and dislocation are closely aligned especially for Asian diasporas because these erasures and refusals to learn to pronounce our names continue to push us to silently assimilate into different names that we answer to (An, Citation2020; Cridland-Hughes & King, Citation2015; Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018). Orientalism and anti-Asian xenophobia (Yellow Peril) proliferate in the absence of Asian diaspora communities and other communities of Color in US school curricula—a haunting that assures its innocence (neutrality), which is unrecognizable to the students whose lives and heritage practices defy this horror (Hsieh et al., Citation2020). Evaluating the extent to which my life has been “better” in the United States is subjective. However, the choices made by people in each context have tangibly impacted my life. Two relentlessly visible impacts are the names that people choose to call me and those people refuse to use. These names shape the lenses through which people interpret and make sense of our experiences, forming what Aoki (Citation2005) referred to as our lived curricula.

Naming is also a catalyst—an elegiac representation of someone’s life, foretelling the tight spaces they will navigate and making visible the resistances happening within namings (Lugones, Citation2003). To counteract the racialization I would face because of my Asianness and the idea that “all Asians are the same,” my parents created for me additional names that reflected their aspirations and hopes that I could conceal my “unassimilability” associated with anti-Chinese fears (Sinophobia) and Yellow Peril (Tuan, Citation1998). In this article, I argue that names and the ideologies contained within them can be mapped as a form of curriculum and an analytic possibility I call the nomencurriculum. The nomencurriculum, I argue, shows how names are curricular touchstones and technologies by which nation-states can constrain, bind, and fit people into a “standardized” paradigm recognizable to white supremacy and empire. I put forward the concept of a nomencurriculum using Latin as I analyze my transnational experiences using Asian critical race theory (AsianCrit) and decolonial theory. Doing so acknowledges that my education socialized me into the technologies of a settler colonial nation-state and responds to the violent ordering constructed by US legal language. My bending of Latin reflects my embodied in-betweenness between contexts using a tripartite portmanteau of nomen (name) + clatura (summoning) + currere ([race]course, running) that translates to “the course of summonings by name.” With names and namings as a site, I foreground the interplay of currere and clatura to identify the string of colonial harms within western nation-states and the healing potential of these analyses, rather than provide a definitive “study” of names and namings (onomastics; Hough, Citation2016).

I analyze global power structures through an analysis of my own three names (English [given], Cantonese [given], Mandarin [given/chosen]). From these names, I show ways I can discern my families’ and communities’ aspirations for my embodiment as I carry these names throughout my life. I also show the competing and simultaneous ideologies of assimilation, erasure, and reclamation as told in legal documents from my adoption and immigration files, interspersed with counternarrative. My analysis uses critical race archival analysis (Morris & Parker, Citation2019) and rememory work (Rhee, Citation2021) to acknowledge the legal contexts in which I am bound and compelled to answer to a single name that erases my transnational movement. I then explore how my curriculum of dislocation (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018) emerges from my namings, presenting lenses of analysis that flatten Asian identities to center Chineseness with harmful implications for non-Chinese members of Asian diaspora communities who are essentialized into a single label.Footnote2 I conclude by outlining how nomencurriculum invites the field of curriculum studies to engage with names and naming as curricular sites and informs how names shape individuals’ movements through educational contexts. I organize my sections with quotes from Everything Everywhere to underscore the simultaneous onslaught of ideologies in my namings and the interplay of my multiple “selves” in my lived curriculum.

“A Lifetime of Fractured Moments, Contradictions, and Confusion”Footnote3: Theoretical Framework

Joy Wang’s/Jobu Tupaki’s persona, a GenZ millennial nihilist, is perhaps part of a broader desire for Asian diasporic representation that “individualizes, multiplies, takes apart then wackily reassembles” responses to anti-Asian racist and xenophobic tropes like Everything Everywhere itself (Cheng, Citation2022, para. 3). Jobu’s line in the film evokes her feelings of a splintered existence that recalls the liminality and dual-domination of Asian American identity seminal to earlier generations of critical Asian diasporic scholarship (Chang, Citation1993; C. J. Kim, Citation1999; Matsuda, Citation1996; Wang, Citation1995). While deeply tied to the US context, I take up AsianCrit’s (undertheorized) commitments to transnational contexts. Decoloniality bolsters analysis of the movements of global power structures and grounds me in the contexts to which I am accountable, allowing me to build on both frameworks. I build on both by making visible the ideologies within my own namings that transcend national borders and branch across imperial worlds. I contribute to this literature by theorizing transnational contexts through examining militancy, empire, and coloniality in Asia as they relate to the proximity to modernity and whiteness embedded into naming (Iftikar & Museus, Citation2018). Necessarily, the transnational legal context (and the centering of US law) is important to this article because of the ways in which transnational adoption processes in the US are governed by multiple layers of state, federal, and international law (Bussiere, Citation1998).

AsianCrit

Asian critical race theory (AsianCrit), an extension of critical race theory (CRT), provides a framework to center Asian diasporas. Iftikar and Museus (Citation2018) laid out seven core tenets of AsianCrit: (1) Asianization; (2) transnational contexts; (3) (re)constructive history; (4) strategic (anti)essentialism; (5) intersectionality; (6) story, theory, and praxis; and (7) commitment to social justice. Asianization, transnational contexts, and story, theory and praxis ground my exploration. Jobu’s/Joy’s disassociativeness in Everything Everywhere suggests that intergenerational shifts in discourse about Asian diaspora identities need to inform AsianCrit’s evolutions. Many Asians’ and Asian diaspora communities’ new reckonings require global analysis to process encounters with racism and colonialism. These fractious contradictions necessitate theorizing the dizzying interplay of ideologies like assimilation, erasure, and reclamation.

Asianization

Iftikar and Museus (Citation2018) described how a single panethnic label (“Asian American”) is created by white supremacy and merges tropes that grew out of nativistic and racist fears of some ethnic groups. Further, this lumping of multiple communities into a singular racial identity marker enables hegemonic tropes, like the model minority myth, to “[cover] up the existence of institutional racism and [validate] US hegemonic ideologies such as color-blindness and meritocracy” (An, Citation2017, p. 133). I take up the Asianization tenet to understand multiple layers of hegemonic discourses about and within Asian diaspora communities that cause me to examine how Asianization and Sinification take up the same logic of essentialization, erasing nuance within Chinese American communities.

Transnational Contexts

The transnational contexts tenet of AsianCrit “recognizes how the forces of American imperialism and neocolonialism, globalization, and war have deeply impacted the flow of migrants between Asia and the United States” (J. Kim & Hsieh, Citation2022, p. 35). In addition to the pursuit of economic opportunity, migrations to the US have been necessitated and catalyzed by migrations and wars within Asia catalyzed in large part by Western imperialism (Goodwin, Citation2010; Lowe, Citation1996). The US government’s immigration/documentation policies and practices created the conditions in which under-equipped immigration officers splintered families with numerous romanizations of Mandarin and Cantonese names. The Chinese exclusion acts further forced migrants to become “paper sons,” claiming to be children of Chinese Americans for the “privilege” of entering the country (Lowe, Citation1996). Transnational contexts impact Asian diaspora racialization, insofar as these contexts embed the Orientalist discourse of a foreign “Other” into US law and dichotomize Asian diasporic experiences in a dual-domination structure of unassimilability (Wang, Citation1995). I use this tenet to show how transnational contexts are also visible within individuals in the case of names.

Story, Theory, and Praxis

Storytelling is an important analytic of CRT on which AsianCrit builds (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002). Delgado and Stefancic (Citation2017) wrote that storytelling facilitates a “deeper understanding of how Americans see race” (p. 44) and challenges dominant narratives about race. The story, theory, and praxis tenet of AsianCrit builds on its CRT roots and “centers Asian American experiences to offer an alternative epistemology … and can inform theory and praxis” (Iftikar & Museus, Citation2018, p. 941). Counterstorytelling centers personal and collective narratives as part of a narrative methodology and challenges the persistent essentialism, panethnic flattening, and Asianization that reproduces cycles of hyper (in)visibility (Berry & Cook, Citation2019; J. Kim & Hsieh, Citation2022; Yeh et al., Citation2022). I use this tenet to frame my own naming(s) as touchstones in my own racialization and to show how Asianization and transnational contexts operate when navigating the multiple ideologies that frame Asian diaspora experiences.

Decolonial Theory

I share in Meghji’s (Citation2022) desire to explore potential synergies between critical race and decolonial theory while resisting a need to “hierarchize or synthesize them” (p. 648). Before getting there, it is important to note that de/anti/postcolonial and deimperial theories each draw from distinct epistemological traditions and praxis projects despite sharing commitments to critique imperialism and colonialism. However, in the contrasts between decolonial and postcolonial theories, concepts that this article brings together, are important intellectual genealogies that need to be acknowledged to justify the multilateral framework, based on complementary theories, that I propose.

Fúnez-Flores et al. (Citation2022) have cautioned scholars (like me) from the Global North to avoid homogenizing or essentializing decolonial theory which, citing Lowe (Citation2015), is a pluriversal discourse and praxis that draws from multiple geographies and contexts. These contexts each contain different manifestations of the technologies of colonial nation-states, as well as the ongoing reverberations of that coloniality and settler horror (Tuck & Ree, Citation2013). Situatedness, as a result, is an important part of how scholars globally come to their critiques of colonialism and imperialism. These critiques are often products of scholars’ individual experiences within the context in which they live as these experiences relate to “collective and geopolitical projects, which at times complement, contradict, or conflict with one another” (Fúnez-Flores et al., Citation2022, p. 601). Decolonial theory emerges from a multiplicity of intellectual genealogies from Latin America and the Caribbean. This multifaceted body of theory intervenes in pursuits of resistances that dismantle “colonial domination, simultaneously allowing us to reflect upon and theorize from these sites of struggle” (Fúnez-Flores et al., Citation2022, p. 609). These sites of struggle are those at the margins made disposable by the (technologies and arrogance of) colonial powers. One such technology, Quijano (Citation2000) wrote, is the contemporary western conceptualization of race and racialization as a means of social classification. Even after successful postcolonial independence movements, global axes of power remain (b)ordered as the reverberations of coloniality rely upon nation-states organized by biological physiognomy, thereby allowing white supremacy and global imperial/colonial hierarchies to persist (Anderson, Citation1983; Leonardo, Citation2002; Subedi & Daza, Citation2008).

As I draw from this multivocal body of scholarship to analyze my own transnational movements between Taiwan and the US, I am aware of the ways that Asian contexts differ from, but are inextricably linked to, the global struggle against the multi-layered hegemonic power structures of empire, (settler) coloniality, and white supremacy (Fanon, Citation1961/1963; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018; Peña-Pincheira & Allweiss, Citation2022; Quijano, Citation2000; Said, Citation1979). Acknowledging this, it is beyond the scope of this article to rigidly categorize the bodies of often-conflated decolonial, postcolonial, and anticolonial scholarship (Fúnez-Flores et al., Citation2022). Instead, I hope to resist this conflation whilst also engaging in their shared critiques. To do so, I draw from postcolonial and decolonial scholarship situated in both Asian and US contexts that argue education and curriculum are complicit in “facilitating the process and manifesting as the product of imperialism and colonialism” (Coloma, Citation2013, p. 650).

Certainly, my analysis is critical of empire and coloniality. I treat Taiwan as a settler colonial nation-state project (Wu, Citation2017) rather than only a society premised on a deimperial-anticolonial independence movement or postcolonial nation-building project (Chen, Citation2010). While I deviate from Chen’s (Citation2010) premise that complete occupation constitutes colonization, I share in what Lin (Citation2012) referred to as Chen’s desire to focus on “psychological complexes and cultural imaginations of the ex-colonized” (p. 158); the need for parallel and simultaneous processes to address this deeply rooted internalized coloniality are felt across time and space. I attend to these “reverberations” across the time and space of coloniality because doing so allows me to bring together the concepts of tight spaces (Lugones, Citation2003), haunting (Tuck & Ree, Citation2013), and dislocation (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018). Taken together, these concepts frame how namings, and curricula of names, are evidence of transnational power structures and, in my case, their interactions with US nation-state apparatuses. This multi-theoretical lens helps me to center the shared commitments and praxes across these theoretical traditions and attend to how the projects of deimperialization and decolonization must proceed together with postcolonial and anticolonial projects to heal the reverberations of epistemic coloniality (Chen, Citation2010; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018; wa Thiong’o, Citation1986).

As a child, I attended regular gatherings of Taiwanese adoptees in the San Francisco Bay Area. Long after no longer attending them, I still cannot forget the words of the other parents who assured us we have better lives. Each time we would (re)introduce ourselves, we would say our names and it would always feel like a sadistic ritual reminding me that I could never forget that I must only feel gratitude for my adoption. Of course, I am grateful for my adoptive parents, and, in each of those gatherings, I saw how names are hauntings. Tuck and Ree (Citation2013) described the “relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation” (p. 642). Part of my relentless rememberings is of the contexts from which and to which I was taken, Taiwan and the United States, and the simultaneous dislocation of being socialized within an episteme of Eurocentric modernity. Ahmed (Citation2021), extending Macgilchrist (Citation2014), discussed the colonial residue in how “colonial vocabulary is employed, reproducing power differentials that continue to create inequality, oppression and poverty” (Ahmed, Citation2021, p. 145). Departing from Yosso’s (Citation2005) concept of aspirational capital, I suggest how aspirational ideologies infiltrate discourse, which I extend to naming in its capacity to signal coloniality/modernity or development in its stasis and standardization. Haunting, in naming, is a way settler coloniality can be embedded by nation-states to signal “the management of those who have been made killable, once and future ghosts—those that had been destroyed, but also those that are generated in every generation” (Tuck & Ree, Citation2013, p. 642). The ghastly spectacle of naming, anglicizing, and categorizing reminds some that the names we may survive using are chosen for the convenience of the dominant—a wispy reminder of alienness (Day, Citation2016). Namings position us relative to hegemonic power structures and are subject to erasure as much as they can reward our conformity on a passport.

Relentless remembering, for me growing up in the Bay Area, manifested in the ways I was never allowed to forget the Chinese American culture into which I was socialized. This separation from my Taiwanese identity manifested in constant corrections and scorn for identifying otherwise; it took me years to confidently resist my assimilation into Chineseness. The multiple layers of politics that made the distinction between Chineseness and Taiwaneseness in the Bay Area necessitated different kinds of pushing back within what Lugones (Citation2003) called a tight space. Lugones (Citation2003) defined tight spaces as sites of resistance in spite of (sociopolitical) constraints. Tight spaces necessitate analyses that “sense resistance, interpret behavior as resistant, even if it is dangerous” (p. 7). Building on Lugones’s (Citation2003) argument that resistance is more than what is visible within decontextualized conceptualizations thereof, Cruz’s (Citation2011) framing centers youth agency in moving within these tight spaces despite the danger and “political climate of retribution” (p. 548). This political climate and the resistances within it are “(re)imaginings of worlds outside the violent confines of global white supremacist heteropatriarchal colonial capitalism” (Allweiss, Citation2021, p. 223) that must be sensed (i.e., felt) as resistance. I extend Lugones’s (Citation2003) and others’ (Allweiss, Citation2021; Cruz, Citation2011) uses of tight spaces in contexts of youth resistance to naming. Names, being a form of social control used by the state to surveil and sort, inherently essentialize people’s existences to Latin script on US and some other Western governmental paperwork, masking heritage languages and aspirational ideologies (resistance and conformity) many parents have for their children that can become embodied in their names.

While names and namings are spaces I argue are tightened by these hauntings, they are also entrees into different knowledges, stories, and identifications as they connect people to the contexts, communities, and traditions to which they/we are accountable. The storytelling made possible by analyzing names and namings helps to locate the violence of these seemingly innocuous state technologies like paperwork to counter the forced disconnection in being assimilated into a Western construction of a name (one given name and one surname) to which one is compelled to answer (summoning). When I say I felt separated from my Taiwaneseness, I mean that my childhood was filled with moments when identifying as Chinese felt mandatory, like celebrating Chinese, not Lunar, New Year. Each moment seemed to add to the distance and disconnection between me and Taiwan. In describing what she called a curriculum of dislocation, Díaz Beltrán (Citation2018) discussed the discursive subjectivities that center “‘First World’/Eurocentric/developed subject positions through nation–state frameworks” (p. 274) that separate people from “decontextualized, ahistorical, and oversimplified framings of culture and Western Eurocentric modernity” (p. 274).

Rather I propose that names and namings can be part of what Díaz Beltrán (Citation2018) called a healing curriculum that is grounded in “critically reflecting on our lived/living experiences” and allows people “to imagine ways in which we become pertinent to our communities” (p. 286). Díaz Beltrán (Citation2018) reflected that her experiences of her curriculum of dislocation taught her “separation from a whole” and made her “relation to others invisible” (p. 276). I resonated with this explanation of the curriculum of dislocation because it reminded me that, once categorized and sorted, people are then part of a hierarchical taxonomy that (b)orders individuals according to the nation-state’s terms. A curriculum of dislocation, as a result, frames the relentlessness, racist, and imperial violence in misnaming. Names and namings, similar to disciplines, are both assemblages of relentless categorization and relentless remembering of the hierarchical knowledge systems to which names contribute (McKittrick, Citation2021; Tuck & Ree, Citation2013). Decolonial theory complements AsianCrit in making sense of the transnational contexts given the latter’s basis in the US legal system. This theoretical merging enables theorizing how global frameworks can sustain analyses of transnational contexts within AsianCrit and make visible the simultaneity of curricula of violence and dislocation.

AsianCrit’s tenets and decolonial frameworks elucidate how global ideologies, logics, and processes necessitate global analyses of naming as curricular. In using AsianCrit, I contribute a theoretically grounded analysis that helps to make visible coloniality’s embeddedness within the ideas of transnational contexts and Asianization in AsianCrit. This visibility facilitates deeper inquiry into (my) namings as curricular within the haunting and engulfment of ambiguity within the Black–white and US–foreign binaries for Asian Americans and Asian diasporic communities in the US.

“Every Rejection, Every Disappointment Has Led You Here, to This Moment”Footnote4: The Lived Curriculum

I cannot seek my alphaverse self, or versejump to another universe where I live with one of my other names. However, I wish I could refuse the disappointing curricular portrayals of people who look like me that I encountered in school. California’s social studies curriculum, for one, romanticized the Spanish colonization of California and enslavement of Indigenous people through Catholic missions (Keenan, Citation2019). For another, California also distilled Asian diaspora representation to minimalist and damage-centered narratives (e.g., railroads, Japanese incarceration) that centered East Asian Americans before subsequently enacting ethnic studies education frameworks (Rodríguez, Citation2020). These curricular narratives that uphold white supremacy and settler ideologies form what Cridland-Hughes and King (Citation2015) referred to as a curriculum of violence that enacts the spirit-murder (Love, Citation2019) of children of Color in schools; An (Citation2020) conceptually extended this curriculum of violence to analyze the experience of Asian diasporic communities in educational contexts. The in-betweennesses and multiplicities erased in the curriculum of violence that many Asian diasporic people experience is dissonant with the intersections and layers of identity we embody. He (Citation2010) referred to “the in-betweenness in exile” (p. 471). The in-betweenness(es) that exists outside the western hierarchical categorization of multiple layers of essentialism bring Asian Americans into official curricular “representation.” This simplistic representation minimizes the complications, contradictions, “hybridity and multiplicity of diaspora consciousness and diasporic space, where exile pedagogy, exile curriculum, and diaspora curriculum emerge” (He, Citation2022, p. 6). Within, and in response to, these curricular narratives are also opportunities for individuals to speak back especially in the site of names and the acts of namings (even if they are in the empire’s languages). Namings, then, can act as entrees into grasping the stories that counter the dislocating affects of curricula by placing us on the junctures where the tangle of ideologies that shape young people’s educational experiences and socializations are visible.

However, teachers work to resist these dehumanizing portrayals with their own narratives and lived experiences (J. Kim & Hsieh, Citation2022; Rodríguez, Citation2020), underscoring the importance of lived curricula in education. Aoki (Citation2005) theorized a lived curriculum in which children are surrounded by a multiplicity of curricula, beyond the school curriculum. Jardine (Citation1990), further, theorized an integrated curriculum that positions children’s lived experiences and explorations as their curriculum “vita.” Both concepts depart from traditional ideas of curriculum as prescriptive and formalized (Egan, Citation1978) or limited to school curricula (explicit, hidden, null; Giroux, Citation1983). Within the complex project of reproducing Chinese identity in school and lived curricula lie problems that impede Asian diasporas’ substantive negotiation of our own coalitions, divisions, and needs in education (Espiritu, Citation1992).

I define curricula broadly, using Aoki’s (Citation2005) and Jardine’s (Citation1990) notions of lived and integrated curricula. This broad definition of curricula positions my and others’ lived experiences and curricular encounters as part of the fullness of individuals’ existences alongside formal school curricula. For Aoki (Citation2005), lived curriculum deviates from planned curriculum in which students’ “uniqueness disappears into the shadow when they are spoken of in the prosaically abstract language of the external curriculum planners who are … condemned to plan for faceless people” (Egan, Citation2003, p. 202). That uniqueness embodies the many assets, identities, and interplays thereof that people bring into schools each day as well as their unique and complex encounters with the global systems of power that systematically shape their lived experiences. Jardine (Citation1990) added that broadening concepts of curriculum to include our spiritual and ecological encounters “exudes the generativity, movement, liveliness, and difficulty that lies at the heart of living our lives” (p. 110). These intimate connections to the earth are informed by our cultural ways of knowing and limited in the school curriculum.

Curricular violence, however, can be similarly broad. Like curricular violence against communities of Color, the curriculum of dislocation outlines how assimilationist logics foreground how curriculum reproduces harmful logics of ahistoricism and decontextualization (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018). Díaz Beltrán complements An (Citation2020) by arguing that curricular erasures and attention to transnational contexts from a US-centered perspective also require desegregating so-called “world” histories and contexts from “longstanding wounds created by imperial history” (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018, p. 275) that cause “psychological and physical violence” (An, Citation2020, p. 147) to Asians and Asian diasporic communities. Díaz Beltrán’s (Citation2018) concept of the “nowhere of global curriculum” problematizes “ideas of the ‘global’ that have been used to think about the world as ‘one place’, as ‘one global community’, as one ‘humankind’ erasing the traces of difference created by multiple histories” (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018, p. 274). Challenging this flattening also undermines western epistemology’s monopoly over the ontological boundaries of modernity and “global citizenship,” instead centering a multiplicity of stories and challenging the ordered fixity and stasis nation-states’ documentation prioritizes.

These four conceptualizations of curricula (lived, integrated, violence, dislocation) contribute dimensions of my expansive conceptualization of curriculum that identifies blockages to multiple pathways of knowing. Bringing these framings together is not to simply argue that everything, everywhere (all at once) is curricular. Instead, my conceptualization shows how names can be pathways of knowing, and all that is contained within our names can be part of our lived curricula. As a result, using curricular tools, I offer new insights into naming, the ideologies imposed upon our being, and the expectations for our embodiment of them. For me, these lived curricula are the deeply embedded presumptions of Chineseness, itself an unstable identity marker (and avatar of Asian Americanness). My exploration of my names extends these extant frameworks of haunting, (re)memory, dislocation, transnational contexts, and counterstorytelling to foreground the tensions within a person’s lived curriculum. I tell this lived curriculum through my names; my nomencurriculum is part of a larger project of rememory that challenges Asianization and Orientalist Sinophobia.

“Looking For Someone Who Could See What I See, Feel What I Feel”Footnote5: Methodology

Jobu/Joy’s characters mirror what I felt navigating my Chinese American parents’ expectations and desires for me. AsianCrit and decolonial framings of narrative show how these ideologies of assimilation, erasure, and reclamation cooperate in my namings. This led me to my own adoption paperwork to learn how I was named. I put Rhee’s (Citation2021) take on Morrison’s (Citation1987) rememory into conversation with critical race archival analysis methods (Morris & Parker, Citation2019) interspersed with AsianCrit counterstory (Kolano, Citation2016; Yeh et al., Citation2022) to theorize my own namings as part of my nomencurriculum.

My parents and I found my adoption documents while renovating our home. The documents included court documents from Taiwan and the United States, newspaper clippings, and a social worker’s home study reports about my parents’ household, accompanied by the requisite testimonies from family members and friends. The documents include both Mandarin originals and notarized English translations of documents. For this article, I selected documents that described me using my names, those that described me without using my names, and those that pertained to my names being changed. In particular, I chose documents from my file that situated me in relation to my parents and talked about the material contexts of my adoption. I selected these documents because they are the only records of my name changes and because they center the US legal context in which I live. However, I chose documents that did not compromise sensitive details about my three parents.Footnote6 I chose the Taipei District Court document titled “Release of Orphan for Immigration and Adoption,” an “Adoption Petition” filed in the Superior Court of California, and a social worker’s home study of my parents’ household, which is used to certify that the adopting family can humanely care for their prospective adoptee. After taking scans of the originals, I reviewed the documents to establish a chronology of my adoption and then read them for the legal motions they made to move me between Taiwan and the United States. I then analyzed them with particular attention to, per my theoretical framework, how the transnational circulations of power and the settler colonial contexts of my birth and adoption legally bound me to answer to my names. I kept going back and forth between my documents and pictures of my birth mother as I wrote to remind me of the humanity of the people involved, often minimized by the documents themselves. I connected with my birth mother via machine-translated text messages after a period of silence; she gave me permission to share quotes in this article. I then sought and received consent from my adoptive parents to use their names, which are referenced throughout the documents given their role as named petitioners.

I arrived at meaning by troubling the linearity of these documents using Rhee’s (Citation2021) interpretation of Morrison’s (Citation1987) rememory. Carrying multiple layers (haunting), rememory “generates different relationships between you, me, and place (time/space)” (Rhee, Citation2021, p. 3) to challenge how people read the world. Rhee (Citation2021) wrote that names “deceive you or fool you as they do not tell you anything about those pictures waiting to happen again before and for you” (p. 18). This challenges the assumption that names are static, an assumption that erases the fluidities between contexts when individuals are reduced to a single name to which they are forced to answer. I also use CRT archival analyses interspersed with counternarrative because “the end result of a CRT-informed research study that relies heavily on historical documentary, archival data, and oral history is ultimately a counter-narrative” (Morris & Parker, Citation2019, p. 30). Building on Morris and Parker (Citation2019), I center these documents, which are the only historical record of my naming, in order to speak against majoritarian and essentialized experiences of racialization created by a legal system in which racism is endemic (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002). Further, I complicate the presumed homogeneity of Chinese diasporic experiences (Yeh et al., Citation2022). Looking critically at both the documents and engaging in rememory, I argue, exposes the ideologies and hauntings of coloniality that are embodied in my names and my namings filtered through the state.

“A Pile of Boring Forms and Numbers”Footnote7: My Names, Their Ideologies

Next, I explore my own namings and my adoption paperwork through my names. I find that, as a settler in both Taiwan and the United States, my names embody ideologies that reflect the desire for proximity to those who enact settler horror against the Indigenous peoples whose lands they stole in an effort to escape empire as they recreated the structures of it (Day, Citation2016). My analysis highlights the nomencurricular narrative that emerges from the weaving of narrative and document analysis of my three naming: (1) my English given name (Kyle Chong) from my adoptive parents, which reflects ideologies of assimilation and the model minority; (2) my Cantonese given name (張玉庭) from a community elder, which reflects my experiences of erasure and how my adopted Chineseness dislocated my Taiwaneseness after coming to the United States; and (3) my Mandarin given/chosen names (張/陳創庭) as a lens of reclamation, which situates me as Taiwanese but also reflects the settler colonial histories and legacies of Taiwan that have pushed me to internalize the forever foreigner trope. These three lenses, with their interplays and simultaneities, converge to outline the utility of a nomencurricular analytic as a way to examine individuals’ lived curricula.

How Did I Get These Names?

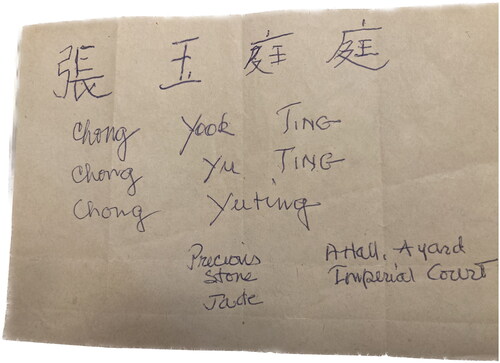

My mother named me 陳創庭 (Chen Chuang-Ting), which translates to stone foundations in a rock garden courtyard from which new life sprouts. My name both invoked the Christian Garden of Eden and the rock gardens of the Imperial Chinese aristocracy. My name legally changed to Kyle Lee Chong (a Gaelic given name) when the State of California issued my delayed birth certificate in 1996. In between these two namings was another. While there are numerous traditions for baby naming, some Chinese and Chinese American families will bestow upon children a “courtesy name,” chosen by a trusted elder or family friend. While my and my adopted parents’ memories have since faded, what we do remember was the name a community elder named King Lee gave me: 張玉庭. This name, in Cantonese, merges my father’s surname (chong) and part of my birth given name (ting), mediated by the character for jade (yook), which is itself a nod to Imperial China. Between these three names, however, are more than semantic differences; there are ideological ones that are embedded between the cracks of legal documents.

Assimilation: English Given Name (Kyle Chong)

I found it strange that my adopted father’s side of the family, like my classmates, were all given Anglo-American names like Robert, Arthur, or Gregory. To understand the extent to which assimilation is coded within my name Kyle, I show some of the legal context that gave me this name. In 1995, my adoptive parents filed a four-page adoption petition with the Superior Court of California in San Francisco. The petition alleges that I was born Chuang-Ting Chen in China (later corrected errata to “Taiwan” in a subsequent amendment). The petition, which is a template completed with the adoptee’s information, accomplishes three stated goals: 1) to state intention to adopt me; 2) to file for custody of me; and 3) to change my legal name. This petition was accompanied by the “home study” report prepared by a social worker who would describe my family to establish whether or not they could sustain me as required by California law.

Within the petition, section VII outlines the intent to adopt and establishes consent between parties to “adopt said child and to treat him in all respects as if he were their lawful child, and as such lawfully should be treated … including the right to inheritance.” The phrase “as if” I was their lawful child violently embodies much discourse about “naturalization” and the process by which someone becomes recognizably nationalized. In fact, this petition is the only document cited as supporting evidence of my naturalization. The petition, however, also shows how the Taiwanese (transnational) contexts are marginalized within the framework of US law because my right to property (inheritance) is fundamental to my legal belonging in the United States. The centrality of property in the document underscores the entanglement of the nominal political rights of democracy and capitalism (Ladson-Billings & Tate, Citation1995). My identity is reduced to that of a nameless “said child,” which positions me as the possession of my parents. In the context of the legacies of the Chinese exclusion acts in the US, the discourse of merely resembling a family highlights the immigration context of my naturalization/adoption. This ghostly namelessness seems to naturalize me with ambivalence, perhaps akin to how some Asian Americans were reluctantly assimilated and superficially “naturalized” as a result of contemporaneous political needs during World War II. Put another way, this language also invisibilizes my own experience, detaching me from the lived reality of the complex ethnoracialization that followed (Chang, Citation1993; Matsuda, Citation1996). Further, this excerpt positions me liminally within the US immigration framework of the time insofar as my Taiwanese citizenship had been renounced when I left Taiwan. This renunciation that my parents made for me left me momentarily without nationality while these proceedings were adjudicated, positioning me uncomfortably in the sociopolitically tight space of “resident alien.”

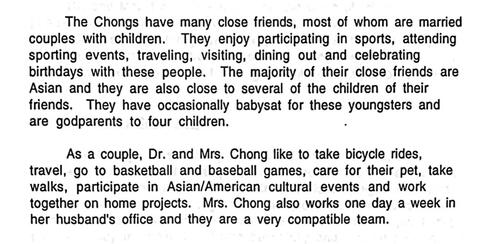

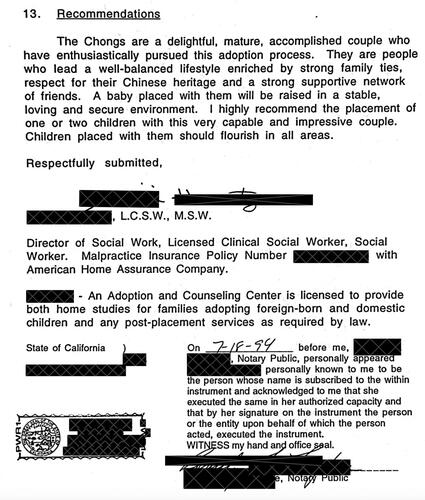

The supporting evidence that accompanied this petition included the “home study” conducted prior to my adoption in which a social worker assessed my then-potential parents’ capacity to care for me. One section of the report titled “Family Interactions and Relationships with Friends,” is emblematic of the rest (see ). In this excerpt, the clinical social worker goes to great lengths to establish my adoptive parents as an assimilated and “normal” Chinese American family. For example, she writes that:

The Chongs have many close friends, most of whom are married couples with children. They enjoy participating in sporting events, traveling, visiting, dining out and celebrating birthdays with these people. The majority of their close friends are Asian and they are also close to several of the children of their friends. … Dr. and Mrs. Chong like to take bicycle rides, travel, go to basketball and baseball games, care for their pet, take walks, participate in Asian/American cultural events [emphasis added] and work together on home projects.

Within this excerpt, the social worker makes the case that they participate in “Asian/American” cultural events, which reinforces the forever foreigner trope that literally excludes Asian diasporas from what she perceived to be US culture through the use of the slash (Jacolbe, Citation2019). Further, the report both embraces and resists Asianization by seeming to undermine my parents’ being in community with their Asian friends by seeming to center the “American” cultural events like baseball games they went to as if they engage in assimilating others. This assessment of my parents is important to my own naming because of how it positions both of them within the space of assimilation given how my adoption was supported by my parents’ degrees, financial stability, and accomplishments. These distinctions were recognizable to the nation-state as reproducing hegemonic and dominant cultural practices that catalyzed my own disidentification and dislocation (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018; Lowe, Citation1996).

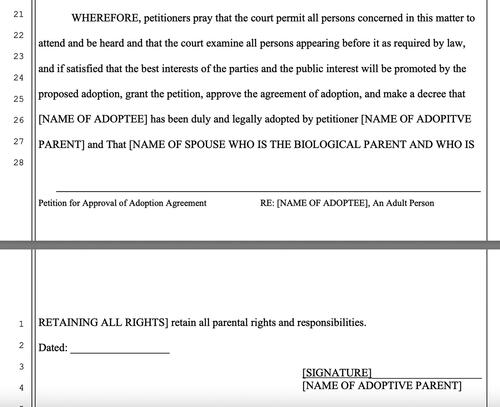

This context from both immediately before and immediately after my adoption situates the “ask” of the culminating adoption petition: the establishment of custody and a legal name change (see ). The template petition concludes by asserting:

WHEREFORE, petitioners pray the court to permit all persons concerned in this matter to attend and be heard, and that the court examine all persons thus appearing before it as required by law, and, if satisfied that the interests and welfare of the child will be promoted by the adoption proposed, grant said petition; and decree that said child has been duly and legally adopted by petitioners and that the custody of said child be awarded to the petitioners, and that said child shall hereafter bear the name _______

This petition, a document to which I do not have legally recognized access, both legally strips me of my Mandarin name and formally severs my legal ties to Taiwan, further suggesting the disidentification and dislocation separating me from my naming. My name change signifies my naturalization, which was granted after guaranteeing that assimilationist ideologies could be imposed upon me in the home study report; this process relied upon the evocation of an idealized US nuclear family that could resemble the dominant white middle class ways of being. I was nominally dislocated from sensing certain resistances to this settler colonial context by being named to blend in with those around me (Louie, Citation2015). My settler identities were played up by my being “awarded” to my parents in the form of legal custody, masking my migration behind the guise of being “as if” I was their “lawful” child. My experience, as part of my lived curriculum, solidifies my dislocation from Taiwan and clarifies how assimilationist ideologies were imposed on me through my renaming. My given name is a white name, positioning me as complicit with the assimilationist logics of Asian diasporaness and, therefore, the model minority. Assimilation and the model minority lay out a problematically simple pathway to upward socioeconomic mobility in proximity to whiteness, as is evident in this piece of my lived curriculum.

Erasure: Cantonese Given Name (張玉庭)

In the previous section, I showed how my legal name change reflected the ways I was positioned in closer proximity to whiteness than I would have been without the name Kyle. My Cantonese name, 張玉庭 (Chong Yook-Ting), reveals much about the erasure that accompanies this assimilation. While King Lee has since died, I analyze both the slip of paper he wrote naming me, the name itself, and further excerpts from the home study that show how this name and naming tracks with erasures I have experienced, reflecting my adopted Chineseness and the dislocation of my Taiwaneseness upon entering the United States.

This slip of paper, written by King Lee, is my only record of this given name (see ). Immediately apparent from this image are the simultaneous acts of assimilation and erasure. In the translation, however, is concrete evidence of the panethnic lumping and erasure that I center in this section (Espiritu, Citation1992). The translation of my name is a shift from the name that my birth mother gave me. King Lee used a more contemporary translation by interpreting the third character as a “hall, a yard, imperial court,” rather than the reference to a rock garden that my mother said she had intended. This, alongside distinctly Cantonese pronunciations, reflects how early Chinese settlers in San Francisco “hailed from many parts of China … [where] local customs varied widely from district to district as did the spoken language” (Chinn, Citation1989, p. 2). My name also contains the character for jade, a nearly ubiquitous symbol of “Chinese” culture in the context of uniquely pan-Chinese sociocultural traditions forged by early Chinese settlers to survive in a ghettoized early San Francisco Chinatown (Lowe, Citation1996).

This Sinification, or making Chinese, of my name, by way of my naming within San Francisco’s emphasis on being a haven for pan-Chinese communities (Chinn, Citation1989), shows and complicates the multiple erasures captured in my namings. Building on Díaz Beltrán (Citation2018), my curriculum of dislocation can be traced further back from my schooling experiences to my namings, but complicated by attempts in my community to name me—and haunt me—in alignment with multiple past and present imperial superiorities (Fanon, Citation1961/1963). The name itself positions me as part of a perhaps romanticized, monolithic form of Chinese culture, even as it uses a marginalized dialect (Cantonese) and is written in traditional script. The name suggests a dated longing for unification while also pulling me into a shared pan-Chinese struggle emblematic of San Francisco’s Chinatown (Louie, Citation2004). Haunted by this legacy, this naming also helps me see further evidence of singular Sinocentric constructions of Asian American panethnic identity—alongside Sinophobic (and other anti-East-Asian diaspora) racism that foreground coalition due to the unique context of shared panethnic experiences in the United States—at the expense of my Taiwanese identity (An, Citation2020; Rodríguez, Citation2020; Wang, Citation1995).

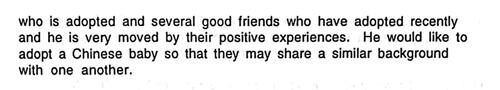

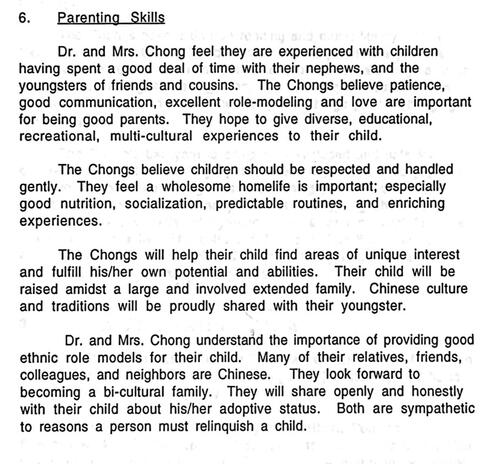

Moreover, the home study report further shows how this act of dislocation in my naming reflects my Sinification and ethnoracial flattening. The 1994 report, issued before my adoption, stated that “the Chongs are applying to adopt a baby girl from Asia” and “have been educated about the fact that their adopted child/children may not resemble them physically.” Despite these disclaimers, the report describes my adoptive parents’ desire (see ).

The social worker wrote: “[Dr. Chong has] several good friends who have adopted recently and he is very moved by their positive experiences. He would like to adopt a Chinese baby so that they may share a similar background with one another.” The report continues:

The Chongs are a delightful, mature, accomplished couple who have enthusiastically pursued this adoption process. They are people who lead a well-balanced lifestyle enriched by strong family ties, respect for their Chinese heritage and a strong supportive network of friends.

The Cantonese name my adoptive parents approved for me seemed to capture what the social worker referred to as my family ties grounded in my adoptive parents’ Chinese heritage; the name attaches me to and claims me as part of their lineage, which also affords me the privilege of conveniently passing as Chinese American. Yet, the glaring conflations of Chineseness, Asianness, and exclusion(s) from belonging in the US captured in the report haunt my second naming (see ). The report further states:

The Chongs will help their child find areas of unique interest and fulfill his/her own potential and abilities. Their child will be raised amidst a large and involved extended family. Chinese culture and traditions will be proudly shared with their youngster.

Dr. and Mrs. Chong understand the importance of providing good ethnic role models for their child. Many of their relatives, friends, colleagues, and neighbors are Chinese. They look forward to becoming a bi-cultural family. They will share openly and honestly with their child about his/her adoptive status.

The report affirms my parents’ “privilege of authenticity,” even as adopted parents, because they could share “exploration of [the child’s] identity without [their] intentions or authenticity being questioned” (Louie, Citation2015, p. 12). That is, my parents’ Chineseness (or manifestations thereof) was left unquestioned because of what surely at least some Chinese American parents experience. Díaz Beltrán’s (Citation2018) point about having to learn that white Eurocentric ways of being are not ideal offers another potential read of Louie (Citation2015), finding a contentiousness about parents educating adoptees about Chinese culture “because they removed the child from his or her birth culture before [they were] old enough to give consent” (pp. 59–60). My parents’ positionality, therefore, complicates the contours of my dislocation because of their connections to Chineseness, while also being socialized and racialized as Chinese American under white supremacy.

The social worker’s assertion that my parents would be ethnic role models for me, yet live in a “bi-cultural” family, shows the cracks and artifice of Asianness as Other; the assertion implied that nuances in our ethnic, cultural, and racial identities were inconsequential. In particular, the ambiguity implicit in their becoming a “bi-cultural” family, whether it refers to two hegemonically essentialized concepts of Chinese and US cultures, or Chinese American and so-called “Asian culture,” shows how what would become my eventual naming was part of a highly political process that reflected both my parents’ aspirations (assimilation) and fears (erasure). This excerpt shows the purity ascribed to a singular Chineseness is bound, or territorialized, to a particular geographic context which, in turn, becomes a deception that apprehends and haunts a child and locks them into an Asianized essentialism from which it is difficult to escape (Louie, Citation2004; Lowe, Citation1996; Rhee, Citation2021; Tuck & Ree, Citation2013). However, in the next section, I discuss my attempt to circumnavigate these ideologies and shift toward reclamation.

Reclamation: Mandarin Given/Chosen Name (張/陳創庭)

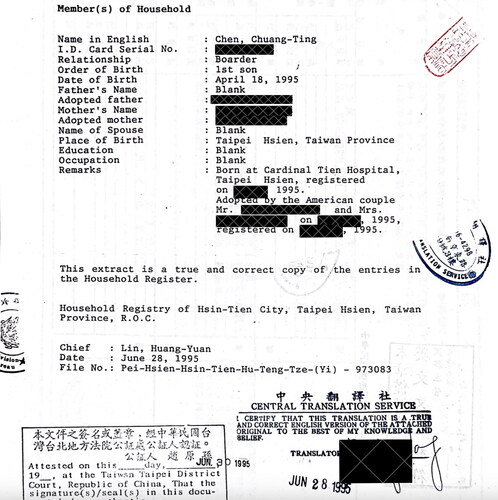

My birth family’s household certificate, filed in the Taipei City Household Registry, establishes my family relations immediately post-adoption (see ). It is important to note my privilege to even have much of this information formally documented—in particular a birth date let alone the name of my birth parent, birth time, or place of birth.

The two most important things in this form are the lines that state my “Relationship” and “Order of Birth,” which place me as a “Boarder” but also a “1st son” without a named father, which is important because Taiwan maintains some Confucian cultural practices of patrilineality and primogeniture. This name positions me ambiguously within my family in a way that is almost analogous to the liminality of Taiwanese identity itself. This form shows the extent to which my naming is ideological. First, I bear my mother’s surname, which itself literally translates to “exhibit/display,” seemingly to flaunt her irrevocable haunting in my life (Tuck & Ree, Citation2013). I say haunting because my surname is one of the old hundred names—the names of the ancient Chinese clans since time immemorial.

Second, in my given name are the words for establishing a garden or courtyard. Interestingly, the characters in my given name contain the radicals for legal courts, trauma, and knife cuts, which are fitting because this analysis is situated in the psychological violence of curriculum and the haunting trauma of law on my experience.Footnote8 I can speak with certainty to my own two interpretations of my names.

The first is a reference to the biblical Garden of Eden, and the second is an evocation of growing with my Taiwaneseness, my roots bringing me back to Taiwan. To orient my name close to the biblical Garden of Eden suggests the influence of the legacies of the Christian missionaries who cared for me and facilitated my adoption. However, this potential placement of my name in proximity to these multiple occupations of Aboriginal (Kulon, Ketagalan, Basai) lands in Taiwan shows the interplays, and leveraging, of those colonial hauntings in a profoundly difficult choice for my birth mother to position me to be adopted by parents who might give me a better life.

In this way, the tight sociocultural space that permitted me to be both “boarder” (marginalized) and “first-born son” (privileged) is tightened a bit further by naming me within the Christian world (Lugones, Citation2003). The implications of doing so suggest a simultaneity of my birth mother embracing the missionary histories in Asia and navigating the Christian adoption service that would facilitate my adoption and her own aspirations for me. This proximity to Christianity facilitated my adoption because my parents, at the time of my adoption, intended to raise me as Christian inasmuch as they selected “Christian” as the “religion child to be reared in” in the social worker’s report. In short, this interpretation of my name is an orientation to sense a subtle resistance. The Orientalist hauntings and painful histories mean even my names can be weaponized to mask the complexities of my namings. This masking makes me legible to the state institutions that act on my behalf while maintaining the idea of a global Yellow Peril that engulfs and flattens my ethnoracialization (Day, Citation2016; Liu, Citation2020).

The second interpretation is similarly uncomfortable for me but is informed by my birth mother herself. This interpretation of my name places me at odds with the Chineseness into which I was ultimately socialized and which I continue to covet. My birth mother’s explanation is that my name means to create a royal court and a happy family:

I thought about your name for a very long time, because apart from your life, this is what I can leave to you. Although I know that as soon as you have a name, you will have to apply for a certificate and leave me. … Because as soon as you have a name, it means you are going to America. But I believe you will come back to me. (personal communication, May 9, 2023)

Talking to my birth mother, I revisited the tensions of naming. My name, something she could leave me with, was subsequently erased under the guise of “naturalization,” much like the erasures implicit in my dislocation from my Taiwaneseness and disidentification through renaming (Lowe, Citation1996). The nation-state, though, has little capacity to sense (Lugones, Citation2003) the human relationship that it severed in stripping me of this name with a form. Yet, I am my birth mother’s first son; that familial bond and cultural affinity will never be captured in the legalistic documents that “legitimize” me to the nation-state. My name, then, functions as a tight space because the boundaries of Taiwanese identity are constrained, engulfed by the mainland Chinese nation-state, the Taiwanese nation-state, and the US nation-state (Chen Citation2010; Ferreira da Silva, Citation2007). Despite multiple layers of dislocation, I see the potential for my nowhere of global curriculum to problematize “standards of global citizenship that disregard relationships embodied in the everyday experiences of citizens whose histories have been marked by colonialism, imperialism and capitalism” (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018, p. 274). I live and sit between these two interpretations as they both simultaneously dislocate me in different ways within the same name.

With my analysis and counternarrative, I challenge dichotomized logics that position me liminally between multiple nation-states and the boundaries of identities. I see ghosts around me, and this ghastliness reveals itself to me every time I write the name that grants me my nationality (US citizenship) but is never fully mine. This unsettledness is my entire point: bearing and embodying our names, our nomencurricula, makes visible the impositions, aspirations, ideologies, and resistances in our namings to challenge the violence of singular signification.

The Nomencurriculum: “The Ups and Downs of Your Lives”Footnote9

Thus far, I have shown how my three names embody entwined ideologies of assimilation, erasure, and reclamation. This simultaneity forms my nomencurriculum. The nomencurriculum intervenes in recent reckonings about the impact of names and (re)namings. From schools and military bases (imperial outposts) named for white supremacist Confederates to cities enforcing the maintenance of names imposed by colonizers, names are curricular insofar as they represent the official signifier and memory of people, places, and things. By splintering the multiple names of people, places, and things into an assemblage of simultaneous ideologies, the nomencurriculum can function as a lens through which to parse whatever “best intentions” dominant forces have for us and their impacts on us. Using the nomencurriculum clarifies how names claim (naming “in honor of”) and frame (naming wars, such as the “Global War on Terror”).

Names and namings are an opportunity to counter this curriculum of dislocation because they foreground the activity of unlearning the emotional distance in theory that allows many scholars (myself included) situated in the Global North to justify or apologize for “keeping myself untouched” (Díaz Beltrán, Citation2018, p. 286). For me, the distance at which I kept myself from my work from the beginning of my career reminds me how the normalized feeling of dislocation at times leads me into a self-imposed exile to try to escape the hauntings of the empire across the contexts through which I move (He, Citation2010). To extend Díaz Beltrán’s (Citation2018) concept, the standardization of given names and patrilineal surnames, while seemingly neutral, violently erases, for example, the value of Indigenous matrilineal worldviews, an erasure that dislocates individuals from their communities (Brant, Citation2023).

The dislocation that happens as a result of names and naming also has an important racial and linguistic dimension because of the ways that languages that do not use Latin script are contorted to fit within state hierarchies. This second dislocation from even the language people use to identify themselves further suggests how naming acts as a technology of violence that tightens the spaces in which people resist the haunting across contexts. Studying names, as a result, can be a way for people to consider how school contexts are governed by dominant ideologies. To begin to resist the ways in which young people are compelled to absorb the curricular violence requires scholars and practitioners to center the sustained erasure and dominant ideologies that dislocate people simply because of the inescapability of namings, coloniality, and modernity.

Therefore, the nomencurriculum allows the field of curriculum studies to account for what names teach us as we move through our lifecycles and what we are taught to sense as a result of our names; these teachings are gateways to knowledge that we carry in our lived curricula. In the classroom, teachers and teacher educators have long known the importance of pronouncing students’ names correctly to acknowledge their cultural assets (Kohli & Solórzano, Citation2012) and avoid the violence of misnaming (Bucholtz, Citation2016). While avoiding racial and gendered microaggressions is of course important, the nomencurriculum also foregrounds that within the classroom everyone must answer to a single name and must be named. We are “called on” by our name and often compelled to answer. However, of equal importance is a caution that the nomencurriculum is not meant to be a means of extraction to further demand that teachers force students to share or be named in ways they do not wish to be named. Teachers must understand the vastness of chosen and given names and challenge English-centrism in their praxis without using their power to further extract cultural knowledge from students that may not be safe or affirming for them to share (e.g., deadnames). Instead, the nomencurriculum is meant to sense (Lugones, Citation2003) resistances within the tight space of names and challenge the tightness names can impose upon individuals. Moreover, the nomencurriculum pushes teachers and those who share space in educational contexts to value the stories of names and namings.

At stake is a world in which Deirdre Beaubeidre is right: a boring pile of forms and numbers alone comes to define our existence and humanity. Instead, the nomencurriculum is an invitation to look beyond the paperwork and make visible the power structures that shape our lives through the names that are given to us, along with their accompanying stories and ideologies. Examining those ups and downs and the many lives visible through our names is an exercise in what is curricular as much as how curricula impact people relentlessly and simultaneously. Further at stake are the constant reminders that the violence of misnaming reproduces fear and othering.

In exploring my nomencurriculum through archival analysis, I see how my names and parts of my lived curriculum between nation-states, settler identities, and cultural affinities are shaped by legal documents. These documents, however, tell far from the full story, which necessitates counternarrative and rememory to elucidate the contexts that show more complexity than a form or piece of government paperwork can and speak against the violence of such paperwork. Labels flatten nuance, and a name is a label. I concur with Díaz Beltrán’s (Citation2018) conclusion that “healing a curriculum of dislocation needs a contextual response to relationships that cannot be predicted” (p. 289). I extend her question “What are the stories that separate me from ‘others’?” (p. 289) by asking: What stories are inescapably captured by the otherwise curricular sites that dislocate us? In exploring my own curriculum of dislocation, I turned to my names to show how the US legal and global contexts that bring me to this work inform my ability to sense resistance and see harm in the unpredictability of my relationships to curriculum.

In part, I wrote this article to deliberate over whether or not I believed that my birth mother gave me up for adoption for a “better life.” My answer brought me to this framework of theoretical merging, revealing the importance of names in and of themselves for the field of curriculum studies. Putting AsianCrit and decolonial theory into conversation shows me that to pursue a “better” life is to pursue modernity grounded in the Eurocentrism that excluded and incarcerated Asians and Asian Americans out of economic and “nativistic” fears and white rage (Fanon, Citation1961/1963; Goodwin, Citation2010). Yet, that pursuit is very real when living in the shadow of the subaltern empire and global superpower in the PRC that has a historical score to settle in response to global Sinophobia. So, for me it is not about a better life but seeing the fluidities of living multiple lives and the rememory that emerges from seeing what might have been had I lived with a different name, recognizing the privilege I have that these names are neither deadnames nor posthumous names. They live in me. Like the ideologies and contexts I move between, it is important to sense the multiple lives created by white supremacy and settler coloniality that pass through me through these names. In the end, a nomencurriculum disrupts the linearity of the educational logics of modernity, social mobility, or history and invites a messy reckoning that lies at the heart of sitting with curricula all at once (formal, explicit, informal, null, lived, embodied, and now nomen).

“It Does Not Look Good”Footnote10 … Right Now: Conclusion

In this article, I put AsianCrit and decolonial theory into conversation to analyze my three names: (1) a Mandarin name given to me by my birth mother; (2) an English name given to me by my adoptive parents; and (3) a Cantonese name given to me by a family friend. These theoretical frames make visible the multiplicity of power structures and belongings into which I have been positioned. My analysis shows the overlaps and cracks of these power structures. This framework of analyzing names helps me track the circulations of global power in my names and outline an analytic possibility that I call nomencurriculum.

Names are part of our lived curricula. My names represent my encounters with the US immigration/adoption system, my position within my own family, and my relationship to the curriculum about Asian diasporas. Through this storytelling, this article contributes to curriculum studies scholarship by providing a framework of analysis through which students can investigate their own lived curricula, especially in the context of heightened censorship and backlash against challenges to official narratives of identity in the US.

This exploration, for me, helped me empathize with Joy Wang/Jobu Tupaki’s nihilism (and not just because I am “GenZ”) from having to endure the relentless injury of an infinity of simultaneous realities. Her personas showed the tensions of bearing and embodying names. The nomencurriculum, however, sits between Joy’s and Evelyn’s experiences and reflects the need for education to tap into the cultural assets and skills that come from versejumping, connect with our multiple simultaneous selves, and make space for Joy’s crushing feeling of bearing layers of pain and terror inflicted by white supremacy and coloniality. My own family stories run parallel to one another, intercepting and interrupting one another throughout my life. Curriculum inquiry, at the heart of this exploration, is imperative for children who look like me; it allows us to not feel the pressure to take on a “white” name in US (educational) contexts out of fear or because of the need to assimilate. Instead, I hope that theorizing a nomencurriculum can help kids learn more about themselves, as I did in this exploration, and disrupt the power structures they are named into.

The curriculum of names that we give to people, places, and things make determinations and tighten spaces. Names create a curriculum of claiming, framing, and blaming, and names signal everything, everywhere, all at once; the harm caused by the names we “give” and impose comes to contain experiences of a finite reality of white supremacy. Certainly, when even naming can act as a technology of white supremacy and settler coloniality, I feel haunted and afraid. Returning to the epigraph with which I chose to begin this article, locating violence in our names makes Deirdre Beaubeirdre’s point that piles of boring forms tell a story about us that does not look good. Yet, this is not the only story a nomencurriculum makes visible. Instead I implore you to use this framework to locate the possibilities of reclamation and resistance in this multiverse of abundance, the ups and downs of our lives, which cannot be contained in a name.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

I express my deepest thanks to Betina Hsieh, Alex(andra) Allweiss, Leanne Taylor, Andrea Louie, Grace Shu Gerloff, and Sheila M. Orr for their significant investment into my scholarship and the many conversations we had in support of this piece. The ways each of you have contributed to my thinking and the power of trusting myself and my voice throughout this piece are innumerable. I also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers. While I might not know you as well as you may have gotten to know me through reviewing this unusual manuscript, I saw how you each engaged with my work for what it could be even as you pushed and pulled on the manuscript to strengthen it. I am grateful to each of the 2023 CI Writing Fellows and mentors for tending to the soul of this piece. I also thank the Department of Teacher Education, Asian Pacific American Studies Program, and College of Law at Michigan State University for logistical supports.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kyle L. Chong (張陳創庭)

Dr. Kyle L. Chong is a transnational adoptee born in Taipei, Taiwan on Kulon, Ketagalan and Basai lands. Kyle was raised by Chinese American parents in San Francisco, CA, on the unceded lands of the Ramaytush Ohlone. His research uses Asian[CR]i[T] and decolonial analyses of race and identity circulate across borders with a particular focus on representations transnational Chinese identity across curricula and contemplate the future(s) of Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Panethnic coalition. Kyle’s ongoing research focuses on challenging essentialized representations of race in animal characters in children’s media, and educator resistances to CRT-‘bans.’ Kyle earned his Ph.D. in Curriculum, Instruction & Teacher Education at Michigan State University on the ancestral and contemporary lands of the Anishinaabeg – Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, & Potawatomi peoples and a B.A. in Politics & Government (Robert S. Trimble Distinguished Asia Scholar) from the University of Puget Sound on the traditional homelands of the Puyallup Tribe.

Notes

1 Deirdre Beaubeirdre (Jamie Lee Curtis) speaks this line to Evelyn Quan Wang and family who are subject to an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audit (Kwan & Scheinert, Citation2022, 20:38).