Abstract

What might femme pedagogy offer to sexuality education? Inspired by Jessica Fields’s (Citation2023) observation that femme pedagogies create intellectual, powerful, and intimate possibilities marked by love and care, we theorize how a femme pedagogy might be used to disrupt the cis-heteronormative, deficit spaces of conventional sexuality education. Centrally, we expand this pedagogy through four key concepts that routinely appear in our own sexuality research and teaching as two queer femmes: bodies, desire, joy, and love and care. In our analysis, we incorporate visual data we created alongside pre-service teachers who we taught in the course Comprehensive Sexuality Education Methods at a university in New Brunswick, Canada in 2023. We describe how art production informs what femme pedagogy looks like in our own sexuality education practice. We suggest that femme pedagogy can be used to mobilize and highlight queer sexualities in sensuous, imaginative, and creative ways—calling upon us to reconsider what sexuality education could be otherwise.

Although teaching has long been recognized as feminized labour (Noddings, Citation2010), the potential of the femme teacher offers something different, something queerer (Story, Citation2017). In North American and European contexts, femme is a queer identity that emerged from Black and Latinx/e ballroom cultures in the 1960s and 1970s (Bailey, Citation2014) and the white working-class lesbian bar scenes of the 1940s and 1950s (Schwartz, Citation2018). We align our working definition of femme with Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (Citation1997), who wrote:

Femme is queer. Drop a femme into a straight bridal shower and she’ll stand out as much as a drag queen would. Femme in the working-class, often colored, contexts I have experienced it in is brassy, ballsy, loud, obnoxious. It goes far beyond the standards of whitemiddleclass feminine propriety. Femme women, [including trans women], construct their girl-ness and construct it the way it works for us. (p. 142)

Scholar and sexuality education researcher Jessica Fields (Citation2023) noted that femme pedagogies create intellectual, powerful, and intimate possibilities marked by love and care. She wrote, “femme theory and pedagogy leans into the wounds and desires” of students and teachers (p. 8). In conversation with Fields’s thinking about the radical tenderness of the femme teacher, we theorize how a femme pedagogy might be used to disrupt the cis-heteronormative, deficit spaces of sexuality education. Femme pedagogy, we argue, is femme theory in action and offers a way to bring queer joy and pleasure into the sexuality education classroom. Unsurprisingly, queer pleasure is routinely minimized and erased in sex education (Barcelos, Citation2023)—with queer desires rendered impossible and projects of heteronormativity left largely unchallenged (Burkholder & Keehn, Citation2024). Writing together as two white queer femmes—one bisexual (Casey) and one lesbian (Melissa)—we turn a femme eye toward the narrow aims of formal schooling and ask: What is femme pedagogy? What can femme pedagogy teach us about the possibilities within sexuality education? How might femme pedagogy be used to mobilize queer sexuality and desire in schooling spaces? In this article, we draw upon visual data, including collage-making, and derive our understanding of femme pedagogy from the creative work we produced alongside 30 pre-service teachers in a class we co-taught at the University of New Brunswick in the spring of 2023. We describe what femme pedagogy looks like in our practice through four key concepts that emerged in our sexuality education methods with pre-service teachers: bodies, desire, joy, and love and care. In this article, we welcome femme pedagogy into the practice of sexuality education—and playfully flirt with queer feminine embodiment, yearning, touch, pleasures, visualities, and intimacy. We also look to problematize femme pedagogy by confronting the underlying whiteness of femme frameworks and the ways in which our own femme pedagogies have encountered complications. Ultimately, we argue that femme pedagogy, even when it encounters complications, can be used to flip sexuality scripts on their head in sensuous and imaginative ways—calling upon us to reconsider what sexuality education could be otherwise.

We are both educators in Fredericton, New Brunswick, located along the Wolastoq river within unceded and unsurrendered Wolastoqiyik territory. Casey is a university professor and researcher and Melissa is a public-school teacher and doctoral student. Our work and lives periodically (but sometimes frequently!) overlap, and during these times, we write, talk, teach, and facilitate workshops together; and, of course, we firmly root these efforts in our queer-femmeness. In the spring of 2023, we co-taught a comprehensive sexuality education methods course to pre-service teachers. During this course, we faced the challenge of teaching a pleasure-based, intersectional, and liberatory sexuality education to teachers whose own sexuality education experiences often mimicked our own—abstinence-focused, STRAIGHT, embarrassing, and certainly not joyful. We approached the class with excitement, laughter, creativity, and femme relationality. We write this article with the aim of placing femme pedagogy and sexuality education together—something that is lacking in sexuality education literature. Additionally, we follow Adam Davies and Ruth Neustifter’s (2023) observation that “fucking is political, relational, and community building and that all bodies are worthy of sexual pleasure and care” (p. 295). In our article, we seek to shake up the normative spaces of sexuality education and map out an ethos of femme pedagogy all over our work, lives, sexualities, and bodies.

Unapologetically Femme

It is important to unpack the cultural and social meanings of femme. In this article, we generally refer to femme as a subversive, complex queer identity. Whereas “feminine” is a descriptor, femme “is used in queer circles to designate queer femininity … It’s both a celebration and a refiguring” (Donish, Citation2017, para. 3)—a queering of femininity. Femmes can be any gender and sexuality, and femmeness includes more specific embodiments, like Black femme, Indigenous femme, queer femme, punk femme, high femme, low femme, femme fatale (think Killing Eve’s Villanelle), female-to-femme drag, crip femme (Jones et al., Citation2022), and fat femme (Minnick, Citation2019; A. Taylor, Citation2018; Schwartz, Citation2018, Citation2020; Shoemaker, Citation2007, Citation2010). Femme identity can also be tied to practices of community-building, healing, caregiving, emotional labour, a bodily relation to the world, rule-bending, and killjoying (Ahmed, Citation2017; Dahl, Citation2017; Hoskin & A. Taylor, Citation2019; Musgrave et al., Citation2022; Schwartz, Citation2018). Femme also has historical, cultural, and political significance that we seek to unpack below.

Problematizing Whiteness

Importantly, we want to acknowledge the concerns of one reviewer of this article who asked us to problematize whiteness and its historical connections to femme as an identity. In North American and European contexts, femme identities emerged from white working-class lesbian bars in the 1940s and 1950s, and these spaces were often racist (Duder, Citation2010). Black queer femmes, Indigiqueer femmes, and queer femmes of colour were instead forming their own cultures, queer joy, and queer scenes (A. Harris & Crocker, Citation1997), some of which flourished within the Black and Latinx/e ballroom cultures in the 1960s and 1970s (Bailey, Citation2014). Black femmes, Indigiqueer femmes, and femmes of colour continue to be marginalized by homonormative and racist conceptualizations of femininity within and outside of queer communities. As Kaila Adia Story (Citation2017) has argued, this:

prevent(s) outsiders from seeing a Black femme identity for what it truly is: a Black and queer sexual identity and gendered performance rooted in embodying a resistive femininity. It is one that transcends and challenges White supremacist, homonormative, and patriarchal ideas of femininity and queerness as White. (p. 412)

Femme as Bodily Expression

Femme is a bodily expression that disrupts the normative performances of gender and conventional beauty in powerful ways. This can include a femme’s decision to communicate their queerness through low femme undertones (Schwartz, Citation2020) and the exaggerated glamour and camp of drag, revealing that there are many ways to look/be/feel/embody femme identities. Packers, dresses, binders, canes, sneakers, bra straps, leather pants, fake eyelashes, sweatpants, wigs, and chains are all tied to femme expression because they can all be used to queer femininity. But, femme is not only tied to an appeal of aesthetics. Femme is also a bodily relation to the world (Ahmed, Citation2004; Dahl, Citation2017). Our femmeness expresses itself through our interlocking sorrows, hauntings, vulnerabilities, and shame. It emerges in our queer romances, our chosen families, our children, our queer femme joy, our generosity towards our bodies and communities, and our heartbreaks. When we gossip with our friends, share a meal, experience intimacy, and dream about our futures, this too is how we experience, embody, perform, and express being femme.

Femme as Political

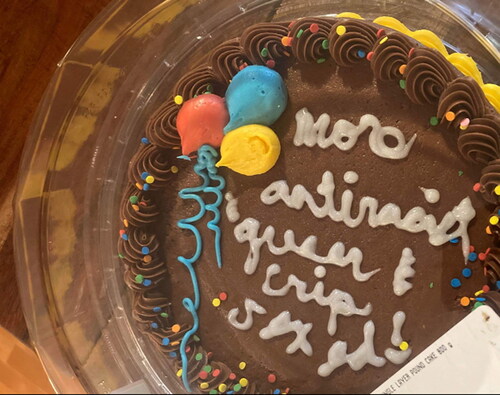

To embody a femme identity is a political act. Femme embodies a defiance towards various axes of oppression, including fatphobia, cisheteropatriarchy, queerphobia, ableism, racism, misogyny, and trans-exclusionary feminism (Lewis, Citation2012; A. Taylor, Citation2018). As Piepzna-Samarasinha observed during an interview with Miriam Zoila Pérez (Citation2014), “ableism lifts up a white, able-bodied, traditionally feminine, middle-class body as the ‘right’ way to be femme … My cane, sexy non-stiletto boots and bed life are femme now because of the labor of disability justice comrades” (para. 7). Andi Schwartz (Citation2018) has reminded us that femme is an intersectional experience, and the existence of femmes of colour, asexual femmes, femmes with disabilities, working-class femmes, and genderqueer and trans femmes disrupts the idea that femme equals white, cis, middle-class, and able-bodied. Schwartz’s framing speaks back to the historical and enduring racism and whiteness in femme movements (see also Dahl, Citation2017).Footnote3 Femme identity means that, yes, you can wear that low-cut, curve-hugging bodysuit while protesting the transphobic amendments to Policy 713 (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Citation2020). It means that after you infuse an anti-racist, queer, crip, and intersectional feminist approach into your sexuality education methods classroom with pre-service teachers, you might even inscribe these concepts on a cake for your students (see ). It also means that, as Yat/Ta explained in a femme roundtable, “you’ve got some sensitivity that doubles as strength and you are down to aestheticize it, commune over it, or fucking fuck about it” (Cecelia, Citation2016, para. 20). Together, we breathe life, beauty, care, resistance, and historical complexity into the enactment of femme identities. And we’re down to unapologetically break as many classroom rules as possible while doing it 💃💅.

Femme Failings

Critical queer theory broadly calls into question the uneven sexuality and gender categories on which conventional societies and institutions (and sexuality education classrooms) rely (Sullivan, Citation2003). It pays attention to why and how societal and institutional authorities solidify around particular bodies, identities, and visualities—especially those that are white, cisgender, thin, and able-bodied—while other bodies and identities are presented as failures (Ryan, Citation2016). We also think through how these authorities might be dismantled, despite ourselves holding many of the privileges that are normatively included in the sexuality education classroom—including our whiteness, cisness, and able-bodiedness (Fordi, Citation2023). Given the conservative nature of sexuality education (Allen et al., Citation2014; Gilbert, Citation2014)—traditional sexuality education classrooms get off on peddling abstinence, patriarchy, shame, queer panic, condom demonstrations, white bodies, and genital labelling charts—critical queer theory has been lauded as a powerful framework for reworking the rigid imaginings of these spaces (Drazenovich, Citation2015). But what about femme theory? A rejection of patriarchal femininity is femme theory’s signature gesture; femme theory disrupts those norms that insinuate that femininity is weak, passive, and perpetually in service to masculinity (Barton & Huebner, Citation2022). It also focuses its attention on femmephobic discourses within and outside of queer communities (Hoskin, Citation2017), upending femme devaluation and centring femme’s power and presence. A glance through literature on femmes reveals how femmephobia (Hoskin, Citation2019), trans-exclusionary feminism (Worthen, Citation2022), slut-shaming (Chemaly, Citation2015), whiteness (Story, Citation2017), and body-shaming (Andry, Citation2018) work together to uphold systems of oppression against feminine-presenting bodies. In turn, femme theory offers us space to imagine femininity operating separately from these systems of oppression (Blair & Hoskin, Citation2015) and shows how femme ways of being are powerful on their own terms (Barton & Huebner, Citation2022).

As Schwartz (Citation2018) has written, “queer theory and femme theory reveal that femme identity is always already a series of failures and rejections. Femme, in its queerness and excess, fails to be normatively feminine. Femme, in its femininity, fails to be normatively queer” (p. 6). It’s exactly this “femme failure” that catches our attention. In exploring the queer art of failure, Jack Halberstam (Citation2011) noted that “it quietly loses, and in losing it imagines other goals for life, for love, for art, and for being” (p. 88). In the normative sexuality education classroom—where queer sex is often positioned as a failure in relation to the projects of cis-heterosexuality or not even positioned as sex at all—we wonder how femme pedagogy might help us reimagine the traditional ways of teaching about sex, pleasure, and bodies through transformative education. Femme’s rejection of conformity, patriarchal femininity, and even normative queerness—three realities that loom in our schools at insidiously routine levels—compel us to imagine its theoretical and pedagogical potential in the sexuality education classroom.

Unsexy Sex Ed

We would be remiss if we failed to point out the current state of our province’s sexuality education programming, which forms the backdrop for this work. In New Brunswick, sexuality education emerges in Explore Your World (Kindergarten–Grade 2) and Personal Wellness (Grades 3–5; Grades 6–8; Grade 9). Students receive no formal sexuality education after Grade 9, aside from human reproduction in Biology 11/12 (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Citation2023). Thematically, New Brunswick’s sexuality education hits all the classic topics: sexual diversity, reproductive health, consent, puberty, menstruation, anatomy, and masturbation. And yet, when we surveyed 411 educators across the province as part of a SSHRC-funded study called Supports and Barriers to Teaching Sex Education in New Brunswick, we found most teachers had received no pre-service or in-service training on how to teach sexuality education. Additionally, many felt uncomfortable teaching about the very topics (particularly sexual diversity, gender identity, and pleasure) listed in the provincial curriculum (see Burkholder et al., Citation2022; Byers et al., Citation2024).

Given that sexuality education classrooms also operate within schooling systems known for policing compliance to gender scripts (Keenan, Citation2017), neutralizing student and worker sexuality (Fields & Payne, Citation2016), and standardizing queerness through strategies like Gender Sexuality Alliances (L. Harris & Farrington, Citation2014) and Sexual Orientation and Gender IdentityFootnote4 (SOGI 123; see Chan et al., Citation2023), the findings from our study are disappointing, but not surprising. After a series of follow-up qualitative interviews and participatory arts-based workshops with 43 in-service teachers from urban and rural locations across the province (see Burkholder & Keehn, Citation2023), the writing on the wall is quite clear (and very unqueer): New Brunswick’s sexuality education programming is failing to meet the needs of young people because of their complex sexualities (Burkholder & Keehn, Citation2024). For instance, there is no mention in the sexuality education curriculum about what crip-centred sex (Jones et al., Citation2022) might look like, or how Black, Indigiqueer, and racialized folks could be better centred within sexuality education. Teachers across the province, despite a lack of professional support, are maneuvering through these unsexy spaces often using a do-it-yourself (DIY) approach to their practice (Burkholder et al., Citation2022). And we’re here for this DIY approach, with the caveat that teachers need time, administrative support, and access to training and resources (Burkholder et al., Citation2022). It’s time to turn towards the disruptive and powerful practice of DIY as a primary method in queer femme pedagogy.

New Brunswick is Keeping a (Queer) Secret

It is a complex time to be queer and trans (and femme!) in our province. We are writing this article as the New Brunswick Conservative government participates in a profusion of queerphobic and transphobic rhetoric and political practice intended to weaken 2SLGBTQI+-inclusive practices in our local schooling system through the revision of Policy 713 (see also S. Brown, Citation2023b). In spring 2023, New Brunswick’s education minister, Bill Hogan, and premier, Blaine Higgs, announced they would be amending Policy 713 because they were concerned that teachers were using the names and pronouns of youth under the age of 16 without parental permission (Leblanc-Haley, Citation2023). Both the premier and education minister have been publicly engaging in a campaign of alarmist statements in a divisive attempt to invoke support and concern from parents and instill fear in 2SLGBTQI + communities (Green, Citation2023; Higgs, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). In a social media post in late June, Blaine Higgs tweeted out,

Minister Austin [Member of the Legislative Assembly] noted how parental consent is required for his 17-year-old son to take a field trip and Tylenol. But his 7-year-old daughter could change her name and gender with school being required to keep it secret from him. That's why we've made the necessary changes to Policy 713. (Higgs, Citation2023c)

As Bill Hogan, Blaine Higgs, and Minister Austin promote queerphobia and transphobia, we suggest that the policy was put in place by caring educators to protect queer and trans students from parents like them (Higgs Citation2023c; Sweet, Citation2023). We speak back against these oppressive political practices and misleading rhetoric, including in our sexuality education course and online (see ). Queer femme resistance, in fact, is central to our research and our lives. We call out anti-oppressive educational practice and resist the devaluation of our queer femme identities (Hoskin, Citation2021), the male “right of access” to the feminine (Hoskin, Citation2017), and the Conservative politicians and right-wing organizers who are trying to reinforce cis-heteropatriarchy to take out decades worth of 2SLGBTQI+-affirming policy and social progress in our province (Higgs, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). We see this as a direct attack on our workplace (Melissa), child’s school (Casey), the pre-service teachers we both train, and on the queer and trans youth and teachers we have worked alongside for years. This work and resistance is profoundly personal.

Figure 2. Twitter-Based Femme Pedagogy (Burkholder, Citation2023; Keehn, Citation2023b)

The amendments to Policy 713 align with other projects of patriarchy and heteronormativity put forth by the Higgs government (S. Brown, Citation2023b). Broadly, New Brunswick has recently witnessed the closure of a widely used 2SLGBTQI + health practice that provided reproductive care, including abortion access (Hansen & Harnish, Citation2020), protests at drag storytime events (S. Brown, Citation2023a), clawed-back funding on teacher professional learning in 2SLGBTQI + education (Green, Citation2023), and the government’s moral panic over New Brunswick’s sexuality education curriculum (S. Brown, Citation2023b). Casey has been engaging queer and trans youth in activism through participatory visual research and organizing in the province since 2017; her work has revealed an enduring legacy of erasure in school curriculum, structural anti-queer and anti-trans violence, and cis-heteronormative environments (Burkholder et al., Citation2021). Melissa has been teaching in rural high schools since 2010, and has observed 2SLGBTQI + youth feel the weight of these erasures but also create vibrant and unconventional queered spaces within the very same systems attempting to render them invisible (Keehn, Citation2023a). Casey’s work has also pointed to the ways that queer youth resist curricular exclusion and gender-based violence through joy and solidarity building (Pride/Swell, Citation2023) and has revealed queer folks all over our province getting together, joyfully organizing, and building community in spite of these oppressive systems. Calling out institutionalized violence—while leaning into community aid, resistance, and joy—is essential to our femme pedagogy.

Critical Femme Pedagogy

We are deeply indebted to Jessica Fields’s (Citation2023) theorizing on femme pedagogies at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Annual Meeting in 2023. During her talk, Fields explored how femme pedagogies include bringing pleasure directly into research and teaching, including in spaces that are normatively patriarchal like the classroom, the faculty, and the academy. This talk inspired us to think through what femme pedagogy looks like in our own sexuality education methods practice with pre-service teachers. We look to expand this work within the context of sexuality education through four key concepts, which are often common themes in our conversations with pre-service teachers: bodies, desire, joy, and care and love. But first, we seek to make sense of femme as a critical pedagogy.

Femme as a critical pedagogy can be used to confront power and marginalizing practices. Femme pedagogy is derived from the knowledge produced within Black and Latinx/e ballroom cultures (Bailey, Citation2014), within working-class lesbian bar and drag cultures (Nestle, Citation1992b; Schwartz, Citation2020), by the Indigiqueer folks of Turtle Island (Whitehead, Citation2022), and by sistergirls (Indigenous trans femmes; Riggs & Toone, Citation2017). In writing about the history of lesbian femme resistance, Rhea Ashley Hoskin (Citation2017) noted, “in their fight for agency, by living, building, fighting, fucking, and loving within a queer community and context, femme lesbians were able to carve out space for feminine identity expressions that veer from patriarchal norms” (p. 99). In our work, we dust off this definition of femme and rework it to embody a diversity of sexualities, genders, and bodies.

Femme pedagogy is deeply queer as it makes space for us all. Femme theorists have pointed to femme identities being traditionally devalued within the 2SLGBTQI + community (Blair & Hoskin, Citation2015)Footnote5, and femme pedagogy as a method offers a mode of resisting colonial, racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, and ableist cultural norms and educational policies (Lewis, Citation2012). But femme pedagogy also challenges the notion that queerness “looks” a particular way and joyfully relishes in bodily autonomy. It reminds us that femmes are never limited by any form of embodiment or expression and that femme identity is something that also exists beyond aesthetics and visualities; femme is about who and what we love, desire, lust for, regret, miss, and grieve (Hoskin, Citation2017).

Femme pedagogy is disruptive; it resists oppression and uplifts the sexual well-being of bodies often made invisible in settler, normative, white supremacist spaces like Canadian public schools. Femmes like to remake, rather than repeat, conventional norms of bodily aesthetics, cultural expressions of beauty, gender expression, and “feminine” behaviour (Hoskin, Citation2021), turning them into markers of queerness rather than accepting them as things to be consumed by the gaze of heteropatriarchy. Our very presence in a room can cause a rupture in mainstream femininity and owes something to the figure of the killjoyFootnote6 (Ahmed, Citation2017); our presence can be uncomfortable (we’ll call out the misogyny) and unruly (we’ll topple sexuality scripts), and it might even shake up some normative worlds (but we’ll follow it up with aftercare). We propose that femme pedagogy is “femme theory in action,” a pedagogical framing and resistive practice that can be used to interpret the complex discourses within sexuality education, point out the queerness that already exists in multitudes in the classroom, and then offer new ways of understanding the work that we do as educators and researchers in these spaces.

Participatory Visual Research

We approach our work using the resistive, disruptive, and artful practice of participatory visual research (Mitchell et al., Citation2017). Through this methodology, we use the co-production of visual texts, in our case collages, to confront, interrupt, and then subvert the status quo to form new models of understanding and representing (Mitchell & De Lange, Citation2013). What makes participatory visual research so useful is its ability to facilitate people getting together for the purpose of co-creating, flipping, displacing, and reimagining normative worlds (Muñoz, Citation2009). Collage, as a disruptive form of artmaking, “rejects … oppressive social contexts, impairing the self and its ability to imagine itself otherwise” (Hajian, Citation2022, p. 100). In our classroom, we employ these disruptive tactics artfully and with a DIY, “more is more” ethos—messy, low-fi, and freeform. We mobilize the visual and its techniques “in an eclectic and campy disruption” of sexuality, identity, and oppressive educational practice (Vaccaro, Citation2014, p. 326).

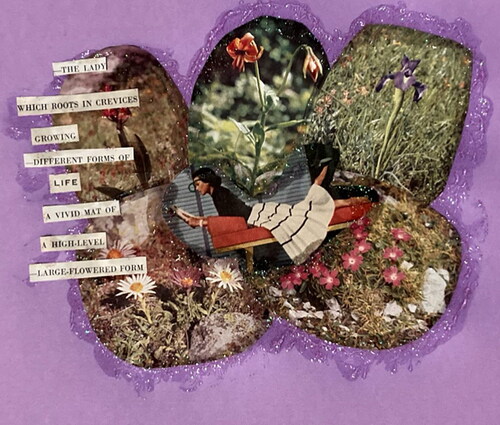

The collages we analyze in this article were produced by the two of us as we were working alongside 30 pre-service teachers in a comprehensive sexuality education methods class that we co-taught in spring 2023. We developed this course to address the need for teachers to receive formal training at the pre-service or in-service levels, which we identified as a need in our larger study (Burkholder et al., Citation2022). Over six weeks, students—pre-service teachers—explored teaching methods that centre pleasure, desire, consent, boundaries, online dating, sex work, and harm reduction through anti-racist, anti-ableist, decolonized, and queered frameworks. In each class, we produced various art pieces and media projects, including zines, collages, cellphilms, buttons, DIY menstrual pads, and soft sculpture genitals alongside the students. Our classroom space was often overrun with felt, thread and needles, colourful fabrics, glitter, and clay. Together we sewed, glued, and filmed our sexuality education curiosities, surprises, and creativities into existence (and resistance).

Findings

In what follows, we outline four concepts—bodies, desire, joy, and care and love—that can serve as benchmarks for embracing femme pedagogy in the sexuality education classroom, in public schools, and in teacher education programming at the pre-service and in-service levels. The four concepts routinely emerged during our analysis of the artwork we produced alongside the pre-service teachers in our Comprehensive Sex Education Methods course. After offering some contextual details on each concept, we expand on our conceptualization of each by exploring the art productions and describing how they inform what femme pedagogy looks like in our own practice.

Bodies

Formal sexuality education spaces are uncompromising on bodily expression and excessiveness. In Canadian sexuality education classrooms, bodies are often reduced to gendered genitalia, their unruliness and messiness disciplined, and their pleasure contained to polite, hetero-monogamous sex for the purpose of reproduction (Austin, Citation2022). As Leah Marion Roberts and Christine Labuski (2023) observed, the normative bodies revered in sex ed programming are “flat, sanitised and pulseless versions of the ones in the room” (p. 157), held steadily in place by the enduring heteropatriarchal ideals of settler colonialism (Wright & Greenberg, Citation2023) and the trepidations of curriculum makers. And beyond phallocentric orientations—who hasn’t awkwardly rolled a condom over a cucumber or banana in sex ed?—vulvas continue to feel the weight of culturally endorsed and settler-induced shame and stigma (Ferranto, Citation2023). It is worth noting that the bodies and sexualities of intersex, Indigenous, transgender, disabled, femme, fat, Black, brown, and queer folk exist in these spaces, but their lived realities are almost never addressed (Davies & Neustifter, Citation2023; Jones et al., Citation2022). And yet, our unruly and always uncontainable bodies continue to make their “leaky, fleshy, textured, soiled, swelling, desiring and unknowable” presence felt (Roberts & Labuski, Citation2023, p. 156).

We wonder, can thinking about bodies through femme pedagogy offer us something more? What if our bodies were recognized as sites of disruption and (un)learning? And what does one “do with the body in the classroom?” (hooks, Citation1994, p. 191). In shaking off the shame of heteropatriarchy, we imagine our bodies also shaking off the straightening scripts of sexuality education—scripts that we never consented to. In rejecting these scripts, our bodies would continue to “want more from education than education can literally hold, than it can bear to, than it wants to, than it will hold” (Zaino et al., Citation2023, p. 8).

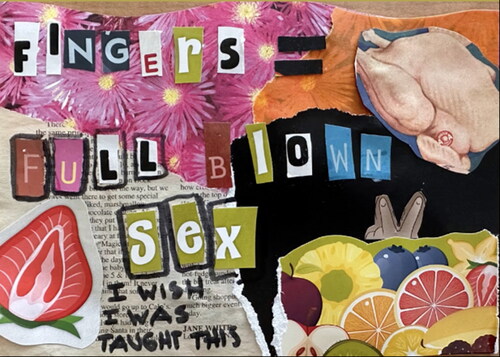

In our classroom, femme pedagogy interrupts limiting understandings of how our bodies experience pleasure, even as sexuality education programming tries to hold us otherwise. Responding to a conversation she had with Casey a few weeks earlier, Melissa created a collage to disrupt conventional imaginings of how bodies engage with sexuality (see ).

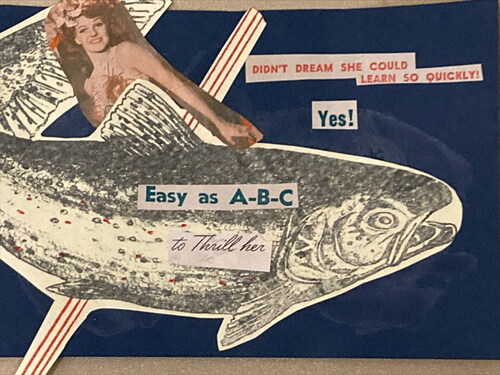

Here, she welcomes fingers as the central source of desire and rejects the idea that the penis is the only source of pleasure or penetration (Barcelos, Citation2023). It is a rendering of the body that is deeply queer: Fingers can offer a flirtatious femme flip of the hair, they can playfully and softly explore, but they can also stimulate, penetrate, form a fist, and then rub soothing lotion on spanked areas afterwards (Afrosexology, Citation2022). Casey also playfully collages together a queer rendering of pleasure in her collage titled “I Like Giving What They Like Getting” (see ).

In creating art alongside pre-service teachers, we think about how our relationships to our own femme bodies (and sexualities) are aesthetic, excessive, and profoundly threatening to the heteronormative projects of sexuality education that seek to control and compartmentalize. Our queered bodies are saturated with stories of patriarchal, anti-queer, slow violence (Higham, Citation2022), and so when we experience pleasure with them—feeling desire, falling in love, or fucking—it’s political and firmly anchored in our resistance and femme joy. Anishinaabe artist Quill Christie-Peters (Citation2018) wrote, “settler colonialism wants us to detach from our bodies, to travel so far away from them, that we do not care when they destroy our bodies” (para. 9). In the sexuality education classroom, we imagine femme pedagogy drawing us closer to our bodies, rebuilding the destruction, and carving out space to relish in queer bodily desire, fleshy satisfaction, and touch.

Desire

Despite Michelle Fine’s (Citation1988) call for the missing discourse of desire in the 1980s—almost 40 years ago—desire is still absent from the aims of formal sexuality education. This risk-based approach to sexuality includes abstinence, compulsory monogamy, pregnancy prevention, fear-based STBBI education, and phallocentric contraception as its basic key tenants (Kantor & Lindberg, Citation2020). In these spaces, consensual sexting invokes moral panic, fisting is deemed too dangerous, and any mention of pleasure generally implies hard white penises fucking “perfect” bodies (Barcelos, Citation2023; Oliver & Flicker, Citation2023). And yet, an absence of sexual pleasure creates missed opportunities for inclusive education and fails to offer a relevant, queered sexuality education (Kolenz & Branfman, Citation2019; Mark et al., Citation2021). In fact, quelling desire in academic spaces is “bad for pedagogy” (Nerhing, 2001, p. 71). In resisting discourses of childhood sexual innocence and producing spaces in which young people can actually experience and imagine desire, sexuality, and queerness! (Prioletta & Davies, Citation2022), we also ask, “is now a good time?”

Here, femme pedagogy intervenes in our practice to make space for the pursuit of pleasure now; we mobilize joy, desire, playfulness, and queerness as a transformative and imaginative disruption to the sexuality education classroom. We see femme pedagogy disruptively complicating settler-imposed monogamy (Wilbur et al., Citation2021) by both normalizing and celebrating polyamorous desires that unfold between multiple consenting people. In fact, we think it is deeply queer and liberatory to seek intimacy, date, and feel pleasure beyond the imposed binary of two. In our classroom, desire—including consensual polyamory, intimacy building, care, and sensuality—is weaved into the discourse in artful ways. Pre-service teachers explored queer pleasure in online spaces through zine production, connected desire and informed consent through drawing, collaged anal sex into conversation, and sculpted vulvas as pleasure-centres, and we did too (see ).

Joy

We seek to make more room for joy in sexuality education. Young people have named sexuality education as being boring and irrelevant to their lives (Allen, Citation2005). These youth have criticized the narrow ways in which sexuality education is discussed in classrooms (Kantor & Lindberg, 2019), with topics often being approached through heteronormative and clinical frameworks rather than through a lens of sexual well-being, excitement, and curiosity (Prioletta & Davies, Citation2022). Likewise, educators have pointed to the inherent risks associated with teaching sexuality education in schooling (Preston, Citation2019), and studies have consistently shown that this perception is often managed through flattened and lifeless programming (Barcelos, Citation2023). In our own context, joy—as an approach to sexuality education that embodies satisfaction, pleasure, well-being, laughter, and curiosity—is omitted from the official New Brunswick sexuality education curriculum, which repeatedly centres risk reduction, puberty, sexual violence, sex anatomy, STBBIs, and reproduction in the discourse (Government of New Brunswick, 2023). In conversations with in-service teachers, we notice that joy is often discussed as an emergent force within their classrooms but not as a touchstone in their practice (Burkholder & Keehn, Citation2023). We wonder: How can we move toward joy in sexuality education? In this sense, we see femme pedagogy as a joyful queer praxis. Queer joy works in tandem with femme identity; the embodiment of each seeks to rebelliously resist the comfort of cis-heteronormative culture through its very existence (Pratt, Citation1997; Turesky & Crisman, Citation2023; MacEwan University, Citation2023). In resisting lifeless sexuality education, we animate our classroom with a sense of campy playfulness, mirroring research that uses laughter and wonder to enhance sexuality education and confront oppressive norms (Kolenz & Branfman, Citation2019).

We noticed the pre-service teachers negotiating and imagining the possibility of joy and lightness in the sexuality education space. A sexuality education rooted in happiness, fun, and humour experienced through our bodies disrupts the risk-based approach in conventional sexuality education classrooms. In thinking about the missing notion of queer joy in her own sexuality education, Casey designs a collage that playfully centres femme sexual joy and pleasure, as part of her teachings (see ).

Through artmaking, she infuses her own bi-femme experience into our practice. In doing so, Casey interrupts our province’s lackluster sexuality education with humour, playfulness, and queered desire and invites the pre-service teachers to do the same. And often, they did so by responding to our femme praxis by telling their own sexuality education stories from their childhood and animating their work with humour. Laughter, in fact, offered us a way of being present with one another (Trethewey, Citation2004). We see this as an approach to sexuality that runs counter to the individualistic, disciplined aims of New Brunswick’s sexuality education curriculum. In using humour to invite queer joy in, we also interrupt traditional power dynamics in the sexuality education space. Michael Tristano Jr. (Citation2022) observed, “our [queer] joy holds immense power. We produce joy in spite of the material realities and structures of power placed upon us” (p. 279). In our workshops and classroom, humour and joy created a means to engage with the taken-for-granted assumptions of sexuality (Trethewey, Citation2004). Much of this was reflected in the artwork we created as a collective, including when we created soft sculptures that sought to bring humour to the teaching of sexuality education (see ). As Kristen Kolenz and Jonathan Branfman (2019) articulated, laughter can be used as “a feminist pedagogical tool to build community and deconstruct oppression in the sex education classroom” (p. 572). This disruption of power—where we replace fear with joyful laughter and playful humour and co-construct the possibilities of what sexuality education can look like in schools alongside teachers—is a central part of our femme practice.

Love and Care

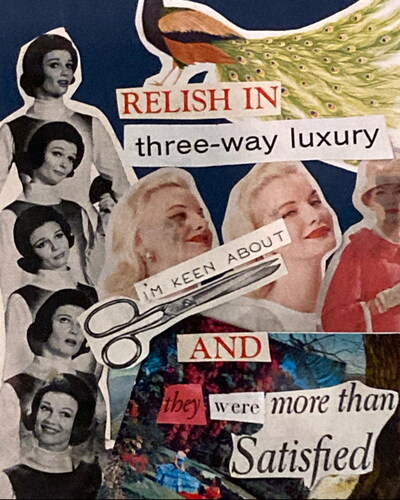

Desire and romantic love are political (Luna, Citation2014), and femme pedagogy has a particular fondness for uplifting conversations on feelings, heartbreak, and situationships (Hoskin, Citation2017). In fact, there’s nothing we love more than disrupting heteronormativity by gossiping about relationships and sexual partners (VanHaitsma, Citation2016) to bring forth bisexual and lesbian entanglements in the flesh. In recognizing this, we also navigate femme invisibility in our own dating experiences and the labours of love that are often naturalized and expected of feminine individuals (A. Taylor, Citation2022; Ward, Citation2010). Joan Nestle (Citation1992a) described how femmes draw their queer communities closer together with their sexuality and emotional labour: “Femmes poured out more love and wetness on our bar stools and in our homes than women were supposed to have” (pp. 138–139). Femme pedagogy also involves employing a feminine ethics of care (Davies & Hoskin, Citation2021). In implementing this feminine ethics of care, we depart again from the normative aims of sexuality education by centring sexual pleasure as a form of self-care (A. Brown, Citation2019), uplifting human connections over individualism (Mishra, Citation2019), and emphasizing mutual respect between bodies (Davies & Neustifter, Citation2023). Femme pedagogy “recognises teaching as care work” (Bimm & Feldman, Citation2020, para. 39) and confronts the misogynistic narratives that often devalue the emotional and support labour of queer femmes (Wong, 2017). In pouring femmeness into our own work, we position young people as seekers, recipients, and givers of love and of care (Cassar, Citation2018)—more than they are generally afforded in conventional sexuality education spaces. We throw light on the capaciousness with which they feel desire and give care beyond normative relationships. Femme pedagogy includes extending love and care toward our own bodies and toward the bodies and boundaries of our sexual partners. Sonya Renee Taylor (Citation2021) wrote, “the body is not an apology” (p. xvii), and self-love is how we “make peace with our bodies [and] make peace with the bodies of others” (p. xvii). We normalize asexual relationships, queer love, casual sexual encounters, and polyamorous possibilities while disrupting bisexual erasure (Johnson & Calafell, Citation2019; Sheff, Citation2020) in our work together and with pre-service teachers, as exemplified in Melissa’s “Relish in Three-Way Luxury” collage (see ).

Mobilizing Queer Sexualities

The tenants of femme pedagogy can help mobilize queer sexualities and desires in schooling spaces, even when uninvited and resisted. We see queerness as an embodied part of our praxis; it is reflected in our art productions as we dream about our queer lives and queer sexual futures (see ).

Femme pedagogy queers any space it enters. It disrupts shame and flirts with nonnormative approaches to the body, feelings, relationships, pleasure, and touch in sexuality education. Femme pedagogy gives an enthusiastic “YES!!” to the inclusion of fingers, fists, anal kink, sapphic desire, power bottoms (and tops), and pegging. Through femme pedagogy, we lean into everything that is normally kept at bay in government-sanctioned sexuality education, including queer sex, and we ask pre-service teachers to re-envision the nature of sexuality alongside us “to something fuller, vaster, more sensual and brighter” (Muñoz, Citation2009, p. 189).

In our femme pedagogy, we take pre-service teachers through the process of stimulating a virtual clitoris and talk about finger sex (see more at Jeunes Pousses, Citation2018), sew menstrual pads (see ) and discuss gender-affirming puberty lessons, and create DIY videos on sex toys for all bodies. In rearranging the purpose of sexuality education, we transform it into something a bit more unruly, prompting pre-service teachers to think about what sexuality is and how it is expressed across bodies, desires, and feelings. We respond to the queer deficit in sexuality education (Woolweaver et al., Citation2023) and offer up nonnormative modes of intimacy and sexuality. As Karen Elizabeth Davis (Citation1990) has reminded us, “sex is only one mode of sexuality, though it has been the privileged mode in our culture, and the measure of all others” (p. 11). In understanding that our work stands in stark contrast to the squeamish tendencies of academia and formal schooling (De Craene, Citation2017), femme pedagogy also seeks to disrupt the heteronormative shock that accompanies learning how queer bodies fuck, love, and feel—through our joy, bodies, desires, and care and love. And we find that very sexy, indeed.

Concluding Thoughts

We often laugh when we imagine what New Brunswick policy and curriculum makers envision as the ideal sex life for young people in this province (and when we envision their delicate attempts at including fingering or anal or polyamory in a curricular outcome). But in recognizing that their existing conceptualizations have produced very narrow narratives on sexuality, which directly impacts the lives of youth (Roien et al., Citation2022), we offer a more emboldened, creative, and pleasurable framework to teaching sexuality education through femme pedagogy. Kathleen Quinlivan (Citation2018) has argued that an alternative and more adventurous approach to sexuality education “involves the formidable and destabilising challenge of letting go of what adults have already deemed young people need to know about sexuality and relationships” (p. 145). In letting go of the straightening, adult-driven scripts of compulsory sexuality education, we demonstrate how femme pedagogy crisscrosses with art production to add texture to a mundane and risk-saturated space. Our modest aim is to show how engaging with femme pedagogy in the sexuality education classroom can help teachers feel inspired, joyful, artful, and alive. Our hope is that young people who experiment with these methods will feel the same. And while we seek to spice up New Brunswick’s sex ed curriculum, our inquiry also comes at a time when gender and sexual diversity are being heavily scrutinized and attacked by far-right rhetoric across New Brunswick (S. Brown, Citation2023a). Within this context, exploring how we can reconceptualize sexuality education to be more playful, disruptive, and queer is increasingly urgent. As we push forward with femme pedagogy—infusing our own bodies, desire, joy, and love and care into this work—we imagine a sexuality education yet to come and ask: How can femme pedagogy help youth negotiate potential experiences with bad sex, participate in defining good sex, and enjoy flourishing sexual lives? How might we continue to shake off linear narratives and dream up a more wondrous sexuality education, even when uninvited? As the premier of New Brunswick continues to come down hard on sexuality education programming and queer and trans youth in this province, we push back even harder. We offer up opportunities for New Brunswick teachers to engage with a queerer sexuality education (see more of the work at Sexuality NB, Citation2022) and engage teachers in a pleasure-based, anti-racist, crip-centred, and disruptive alternative to the deeply uninteresting and expired sexuality education curriculum in this province. Here, we’re leaning into our queer femme praxis and inviting teachers to join us in relishing the vibrancy that is queer femme potentiality.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Casey Burkholder

Casey Burkholder (she/her) is an Associate Professor at the University of New Brunswick’s Faculty of Education. Her research program centers on work with 2SLGBTQ+ youth and pre-service teachers to agitate for social change through participatory visual research approaches, including DIY art production and participatory archiving. In choosing a research path at the intersection of resistance and activism, gender, sexuality, inclusion, DIY media-making, and Social Studies education, Casey seeks to work with community members to create solidarities, address oppressive systems and structures, and take collaborative social action from-the-ground-up. Casey previously co-edited Facilitating Community Research for Social Change: Case Studies in Qualitative, Arts-Based and Visual Research with Dr. Funké Aladejebi and Dr. Josh Schwab-Cartas (Routledge, 2022), Fieldnotes in Qualitative Education and Social Science Research with Dr. Jen Thompson (Routledge, 2020) and What’s a Cellphilm?: Integrating Mobile Phone Technology into Participatory Visual Research and Activism (Brill/Sense, 2016) with Dr. Katie MacEntee and Dr. Josh Schwab-Cartas.

Casey Burkholder

Associate Professor

Faculty of Education – UNB

Melissa Keehn

Melissa Keehn (she/her) is a New Brunswick educator and doctoral candidate at the University of New Brunswick. As part of her work to support 2SLGBTQ+ students in rural contexts, she has facilitated multiple Gender Sexuality Alliances with high school youth and serves on the New Brunswick Pride in Education Executive. Melissa’s research interests include critical studies, educational pedagogy and policy, rurality, and queer youth cultures. Her work is inspired by her own lived experiences teaching as a queer educator in rural communities, an ongoing concern over the spatial exclusions which have impacted her 2SLGBTQ+ students, and a desire for educational reform.

Melissa Keehn

PhD Student

Faculty of Education – UNB

Notes

1 As we can attest, femmes wearing dresses for other femmes is deeply nonnormative: It diverges from the social and cultural norms that tell us to style our bodies for the heteropatriarchal cis-male gaze. It is an expression of queer sensuality and sexuality.

2 The problem of whiteness in queer activism and organizing spaces was highlighted in our community by Indigo Poirer and Rebecca Salazar Leon, Fredericton-based artists and activists who co-founded BIPOC Pride in New Brunswick to disrupt the erasure of Indigiqueer, Two Spirit, Black, and queers of colour in this territory.

3 We also wish to make space for asexual femmes, as one of the reviewers of this manuscript suggested. Of course, asexual folks can also be femmes, as “an asexual person is anyone who uses the term ‘asexual’ to describe themselves. The label can only be applied internally, no one has the power to create a set of criteria which determine who ‘is’ and ‘is not’ asexual” (Collective Identity Model, as cited in Amin, Citation2023, p. 96).

4 While GSAs are often celebrated for offering “safe spaces” for queer and trans youth in schools, we are critical of these school-based initiatives (like GSAs and SOGI Education) because they do not address the real systemic violence and routine discrimination faced by queer and trans youth in schools (Chan et al., Citation2023). Further, as Anne Harris and David Farrington (2014) have argued, these initiatives often “perpetuate discourses of sameness that prevent deeper and more localised ways of addressing queerness in its many and proliferating forms” (p. 145).

5 Hoskin (Citation2017) has argued that femme devaluation remains obscure, including within queer communities, because of “its ability to masquerade as other forms of oppression, and the cultural tendency toward its naturalization” (p. 95).

6 Sara Ahmed’s (Citation2017) feminist killjoy is relevant to femme pedagogy because of its unruly and upsetting nature; it highlights what is problematic, like a sexist dress code policy or a racist sexuality education curriculum. A killjoy digs deep to expose and magnify violence—institutional or otherwise—and brings it to the surface (unsettling the comfort of the status quo and offering something different).

References

- Afrosexology [@afrosexology_]. (2022, July 9). Aftercare: After sex I’d like … [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CfzguS6O9a5/

- Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh University Press.

- Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

- Allen, L. (2005). “Say everything”: Exploring young people’s suggestions for improving sexuality education. Sex Education, 5(4), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810500278493

- Allen, L., Rasmussen, M. L., Quinlivan, K., Aspin, C., Sanjakdar, F., & Brömdal, A. (2014). Who’s afraid of sex at school? The politics of researching culture, religion and sexuality at school. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 37(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2012.754006

- Amin, K. (2023). Taxonomically queer? Sexology and new queer, trans, and asexual identities. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 29(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-10144435

- Andry, S. (2018). Deviant bodies. In J. Eric-Udorie (Ed.), Can we all be feminists? New writing from Brit Bennett, Nicole Dennis-Benn, and 15 others on intersectionality, identity, and the way forward for feminism (pp. 225–237). Penguin Books.

- Austin, A. (2022). The role of formal education in advancing the goal of reproductive justice: A case for comprehensive sexual education in Ontario (Publication No. 29072196) [Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Bailey, M. M. (2014). Engendering space: Ballroom culture and the spatial practice of possibility in Detroit. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(4), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.786688

- Barcelos, C. A. (2023). Adventures in fisting. Sex Education, 23(3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2061441

- Barton, B., & Huebner, L. (2022). Feminine power: A new articulation. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1771408

- Bimm, M., & Feldman, M. (2020, January 27). Towards a femme pedagogy, or making space for trauma in the classroom. MAI: An Intersectional Journal. https://maifeminism.com/towards-a-femme-pedagogy-or-making-space-for-trauma-in-the-classroom/

- Blair, K. L., & Hoskin, R. A. (2015). Experiences of femme identity: Coming out, invisibility and femmephobia. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.921860

- Brown, A. (2019). Pleasure activism: The politics of feeling good. AK Press.

- Brown, S. (2023a, March 11). Moncton, N.B. drag storytime event faces protest. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/9545132/moncton-drag-storytime-protest/

- Brown, S. (2023b, May 10). N.B. sex education curriculum included in review of school gender identity policy. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/9688287/n-b-sex-ed-curriculum-review-gender-identity-policy-713/

- Burkholder, C. [@CM_Burkholder]. (2023, June 10). Although within the provincial mandate, access to #gender affirming healthcare & education have declined under the @premierbhiggs government. Suggest looking [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/CM_Burkholder/status/1667672886604365824

- Burkholder, C., Byers, S., & O’Sullivan, L. (2022). New Brunswick teachers on the provision of comprehensive sexual health education in Anglophone school districts. Sexuality New Brunswick. https://www.sexualitynb.org/report

- Burkholder, C., Hamill, K., & Thorpe, A. (2021). Zine production with queer youth and pre-service teachers in New Brunswick, Canada: Exploring connection, divergences, and visual practices. Canadian Journal of Education, 44(1), 89–115. https://doi.org/10.53967/cje-rce.v44i1.4535

- Burkholder, C., & Keehn, M. (2023). “Something that is so overlooked”: Joyfully exploring queer bodies and sexualities in sex education in New Brunswick, Canada through participatory art production. Sex Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2296984

- Burkholder, C., & Keehn, M. (2024). “In some ways they’re the people who need it the most”: Mobilizing queer joy with sex ed teachers in New Brunswick, Canada. Journal of Queer and Trans Studies in Education, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.60808/nfr3-0473

- Byers, E. S., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Burkholder, C. (2024). How prepared are teachers to provide comprehensive sexual health education? American Journal of Sexuality Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2024.2344518

- Cassar, J. (2018). Exploring spaces for “love” in sexuality education curricula across the European Union. In R. A. Benavides-Torres, D. J. Onofre-Rodríguez, M. A. Márquez-Vega, R. del Carmen Barbosa-Martínez (Eds.), Sex education: Global perspectives, effective programs and socio-cultural challenges (pp. 37–60). Nova Science Publishers.

- Cecelia. (2016, July 18). What we mean when we say “femme”: A roundtable. Autostraddle. https://www.autostraddle.com/what-we-mean-when-we-say-femme-a-roundtable-341842/

- Chan, A., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., & Saewyc, E. (2023). Experiences of discrimination or violence and health outcomes among Black, Indigenous and People of Colour trans and/or nonbinary youth. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79(5), 2004–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15534

- Chemaly, S. (2015). Slut-shaming and the sex police: Social media, sex, and free speech. In S. Tarrant (Ed.), Gender, sex, and politics: In the streets and between the sheets in the 21st century (pp. 125–140). Routledge.

- Christie-Peters, Q. (2018, March 26). Kwe becomes the moon, touches herself so she can feel full again. GUTS Magazine. https://gutsmagazine.ca/kwe-becomes-the-moon/

- Dahl, U. (2017). Femmebodiment: Notes on queer feminine shapes of vulnerability. Feminist Theory, 18(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700116683902

- Davies, A. W., & Hoskin, R. A. (2021). Using femme theory to foster a feminine-inclusive early childhood education and care practice. In Z. Abawi, A. Eizadirad, & R. Berman (Eds.), Equity as praxis in early childhood education and care (pp. 107–123). Canadian Scholars Press.

- Davies, A., & Neustifter, R. (2023). Fat fuckers and fat fucking: A feminine ethic of care in sex therapy. Psychology & Sexuality, 14(1), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2022.2109988

- Davis, K. E. (1990). I love myself when I’m laughing: A new paradigm for sex. Journal of Social Philosophy, 21(1–2), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.1990.tb00272.x

- De Craene, V. (2017). Fucking geographers! Or the epistemological consequences of neglecting the lusty researcher’s body. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(3), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1314944

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2020). Policy 713: Sexual orientation and gender identity. Government of New Brunswick. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/ed/pdf/K12/policies-politiques/e/713.pdf

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2023). High school block: Biology 111/2. Government of New Brunswick. https://curriculum.nbed.ca/learning-areas/high-school-block/science/biology-111-2/

- Donish, C. (2017, December 4). Five queer people on what “femme” means to them. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/d3x8m7/five-queer-people-on-what-femme-means-to-them

- Drazenovich, G. (2015). Queer pedagogy in sex education. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 38(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/canajeducrevucan.38.2.07

- Duder, C. (2010). Awfully devoted women: Lesbian lives in Canada, 1900–65. UBC Press.

- Ferranto, J. (2023). Vulva education through fiber arts: The + cunt project. Art Therapy, 40(4), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2023.2206778

- Fields, J. (2023, April 15). Femme pedagogies: Curiosity, repair, and survival [Paper presentation]. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, United States.

- Fields, J., & Payne, E. (2016). Editorial introduction: Gender and sexuality taking up space in schooling. Sex Education, 16(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1111078

- Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.1.u0468k1v2n2n8242

- Fordi, S. (Host). (2023, February 21). Queering sex education (No. 3) [Audio podcast episode]. In The sex ed series. https://rss.com/podcasts/the-sex-ed-series-by-susie-fordi/835560/

- Gilbert, J. (2014). Sexuality in school: The limits of education. University of Minnesota Press.

- Green, D. (2023, May 10). Letter: Government of New Brunswick revokes support for Pride in Education. Coop Média NB/NB Media Co-op. https://nbmediacoop.org/2023/05/10/letter-government-of-new-brunswick-revokes-support-for-pride-in-education/

- Hajian, G. (2022). Revealing embedded power: Collage and disruption of meaning. Revista GEMInIS, 13(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.53450/2179-1465.RG.2022v13i2p94-104

- Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Duke University Press.

- Hansen, J., & Harnish, S. (2020, May 19). The truth about Clinic 554 in Fredericton. Coop Média NB/NB Media Co-op. https://nbmediacoop.org/2020/05/19/the-truth-about-clinic-554-in-fredericton/

- Harris, A., & Farrington, D. (2014). “It gets narrower”: Creative strategies for re-broadening queer peer education. Sex Education, 14(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2013.854203

- Harris, L., & Crocker, E. (1997). Fish tales: Revisiting “a study of a public lesbian community.” In L. Harris & E. Crocker (Eds.), Femme: Feminists, lesbians, and bad girls (pp. 40–51). Routledge.

- Higgs, B. [@premierbhiggs]. (2023a, June 22). This was my statement to media when asked about party politics and speculation of a leadership review [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/premierbhiggs/status/1671975076361543706

- Higgs, B. [@premierbhiggs]. (2023b, June 10). Susan Holt & Justin Trudeau don’t believe parents need be involved in such critical discussions as gender identity, even in [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/premierbhiggs/status/1667687687199903747

- Higgs, B. [@premierbhiggs]. (2023c, June 21). Minister Austin noted how parental consent is required for his 17 year old son to take a field trip and [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/premierbhiggs/status/1671621673831878656

- Higham, L. (2022). Slow violence and schooling. In G. Noblit (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1835

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- Hoskin, R. A. (2017). Femme theory: Refocusing the intersectional lens. Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture, and Social Justice, 38(1), 95–109. https://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/4771

- Hoskin, R. A. (2019). Femmephobia: The role of anti-femininity and gender policing in LGBTQ+ people’s experiences of discrimination. Sex Roles, 81(11–12), 686–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01021-3

- Hoskin, R. A. (2021). Can femme be theory? Exploring the epistemological and methodological possibilities of femme. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 25(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2019.1702288

- Hoskin, R. A., & Taylor, A. (2019). Femme resistance: The fem(me)inine art of failure. Psychology & Sexuality, 10(4), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1615538

- Jeunes Pousses. (2018). Clit me. https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/clitme/

- Johnson, J. A., & Calafell, B. M. (2019). Disrupting public pedagogies of bisexuality. In A. Atay & S. Pensoneau-Conway (Eds.), Queer communication pedagogy (pp. 62–72). Routledge.

- Jones, C. T., Murphy, E., Lovell, S., Abdel-Halim, N., Varghese, R., Odette, F., & Gurza, A. (2022). “Cripping sex education”: A panel discussion for prospective educators. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 11(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v11i2.890

- Kantor, L. M., & Lindberg, L. (2020). Pleasure and sex education: The need for broadening both content and measurement. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 145–148. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305320

- Keenan, H. B. (2017). Khaki drag: Race, gender, and the performance of professionalism in teacher education. In B. Picowwer & R. Kohli (Eds.), Confronting racism in teacher education (pp. 97–102). Routledge.

- Keehn, M. (2023a). (In)visible youth: Considerations for visual research in rural New Brunswick’s queer spaces. In C. Burkholder, J. Schwab-Cartas, & F. Aladejebi (Eds.), Facilitating visual socialities: Processes, complications and ethical practices (pp. 99–115). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Keehn, M. [@melissakeehn2]. (2023b, June 21). Just our daily dose of queerphobic and transphobic rhetoric coming from the NB Premier 🙄 Someone needs to take a [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/melissakeehn2/status/1671653089764360193

- Kolenz, K. A., & Branfman, J. (2019). Laughing to sexual education: Feminist pedagogy of laughter as a model for holistic sex-education. Sex Education, 19(5), 568–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1559728

- Leblanc-Haley, T. (2023, June 15). NB debrief: Review of Policy 713 puts queer and trans kids in danger, education experts say [video]. Coop Média NB/NB Media Co-op. https://nbmediacoop.org/2023/06/15/nb-debrief-review-of-policy-713-puts-queer-and-trans-kids-in-danger-education-experts-say-video/

- Lewis, S. (2012). I came to femme through fat and Black. In V. Trovar (Ed.), Hot and heavy: Fierce fat girls on life, love and fashion (pp. 48–51). Seal Press.

- Luna, C. (2014, July 21). On being fat, brown, femme, ugly, and unloveable. BGD: Amplifying the Voices of Queer & Trans People of Color. https://www.bgdblog.org/2014/07/fat-brown-femme-ugly-unloveable/

- MacEwan University. (2023, March 6). Celebrating queer joy. MacEwan University Campus Life. https://www.macewan.ca/campus-life/news/2023/03/news-queer-joy-23/

- Mark, K., Corona-Vargas, E., & Cruz, M. (2021). Integrating sexual pleasure for quality & inclusive comprehensive sexuality education. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(4), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2021.1921894

- Minnick, K. W. (2019). “Femme fatales of faith”: Queer and “deviant” performances of femme within Western protestant culture (Publication No. 13886221) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Denver]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2295515724?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Mishra, A. (2019). Reflections on the value of vulnerability: Towards a relational understanding of vulnerability with ethics of care. International Journal of Philosophy and Social-Psychological Sciences, 5(4), 31–38.

- Mitchell, C., & De Lange, N. (2013). What can a teacher do with a cellphone? Using participatory visual research to speak back in addressing HIV&AIDS. South African Journal of Education, 33(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412171336

- Mitchell, C., De Lange, N., & Moletsane, R. (2017). Participatory visual methodologies: Social change, community and policy. Sage.

- Muñoz, J. (2009). Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. New York University Press.

- Musgrave, T., Cummings, A., & Schoenebeck, S. (2022, April). Experiences of harm, healing, and joy among Black women and femmes on social media. Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Article 240. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3517608

- Nehring, C. (2001, September 1). The higher yearning. Harper’s Magazine, 303(1816), 64–72.

- Nestle, J. (1992a). The femme question. In J. Nestle (Ed.), The persistent desire: A femme–butch reader (pp. 138–146). Alyson Publications.

- Nestle, J. (Ed.). (1992b). The persistent desire: A femme–butch reader. Allyson Publications.

- Noddings, N. (2010). Moral education and caring. Theory and Research in Education, 8(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785103686

- Oliver, V., & Flicker, S. (2023). Declining nudes: Canadian teachers’ responses to including sexting in the sexual health and human development curriculum. Sex Education, 24(3), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2204223

- Pérez, M. Z. (2014, December 3). Femmes of color sound off. Colorlines. https://www.colorlines.com/articles/femmes-color-sound

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. (1997). On being a bisexual femme. In L. Harris & E. Crocker (Eds.), Femme: Feminists, lesbians, & bad girls (pp. 138–144). Routledge.

- Pratt, M. (1997). Pronouns, politics, and femme practice: An interview with Minnie Bruce Pratt. In L. Harris & E. Crocker (Eds.), Femme: Feminists, lesbians & bad girls (pp. 190–197). Routledge.

- Preston, M. (2019). “I’d rather beg for forgiveness than ask for permission”: Sexuality education teachers’ mediated agency and resistance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.017

- Pride/Swell. (2023). Pride/Swell+: A multi-generation art, activism & archiving project with 2SLGBTQ+ folks in Atlantic Canada. https://www.prideswell.org/

- Prioletta, J., & Davies, A. W. (2022). Femmephobia in kindergarten education: Play environments as key sites for the early devaluation of femininity and care. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491221137902

- Quinlivan, K. (2018). Exploring contemporary issues in sexuality education with young people: Theories in practice. Springer.

- Riggs, D. W., & Toone, K. (2017). Indigenous sistergirls’ experiences of family and community. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1165267

- Roberts, L. M., & Labuski, C. (2023). Bodily excess and the practice of wonder in sexuality education. Sex Education, 23(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2084062

- Roien, L. A., Graugaard, C., & Simovska, V. (2022). From deviance to diversity: Discourses and problematisations in fifty years of sexuality education in Denmark. Sex Education, 22(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2021.1884060

- Ryan, C. L. (2016). Kissing brides and loving hot vampires: Children’s construction and perpetuation of heteronormativity in elementary school classrooms. Sex Education, 16(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1052874

- Schwartz, A. (2018). Low femme. Feral Feminisms, 7, 5–14. https://feralfeminisms.com/low-femme/

- Schwartz, A. (2020). Soft femme theory: Femme internet aesthetics and the politics of “softness.” Social Media + Society, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120978366

- Sexuality NB. (2022). Supports & barriers to teaching sexuality education in New Brunswick. https://www.sexualitynb.org/

- Sheff, E. (2020). Polyamory is deviant—But not for the reasons you may think. Deviant Behavior, 41(7), 882–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1737353

- Shoemaker, D. (2007). Pink tornados and volcanic desire: Lois Weaver’s resistant “femme(nini)tease” in “Faith and dancing: Mapping femininity and other natural disasters.” Text and Performance Quarterly, 27(4), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930701573303

- Shoemaker, D. (2010). Queer punk macha femme: Leslie Mah’s musical performance in Tribe 8. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 10(4), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708610365475

- Story, K. A. (2017). Fear of a Black femme: The existential conundrum of embodying a Black femme identity while being a professor of Black, queer, and feminist studies. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 21(4), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1165043

- Sullivan, N. (2003). A critical introduction to queer theory. NYU Press.

- Sweet, J. (2023, May 19). N.B. education minister defends Policy 713 review as student rallies continue. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/nb-education-minister-responds-to-lgbtq-concerns-1.6849869

- Sylliboy, J., & Young, T. (2017). Coming out stories: Two Spirit narratives in Atlantic Canada. Urban Aboriginal Knowledge Network. https://uakn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/UAKN-Atlantic-Final-Report-Coming-Out-Research_Final-Report-2017.pdf

- Taylor, A. (2018). “Flabulously” femme: Queer fat femme women’s identities and experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 22(4), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2018.1449503

- Taylor, A. (2022). “But where are the dates?” Dating as a central site of fat femme marginalisation in queer communities. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1822429

- Taylor, S. R. (2021). The body is not an apology: The power of radical self-love. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Trethewey, A. (2004). Sexuality, eros, and pedagogy: Desiring laughter in the classroom. Women and Language, 27(1), 34–39.

- Tristano, M., Jr. (2022). Performing queer of color joy through collective crisis: Resistance, social science, and how I learned to dance again. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 22(3), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086221087671

- Turesky, M., & Crisman, J. J. A. (2023). 50 years of pride: Queer spatial joy as radical planning praxis. Urban Planning, 8(2), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v8i2.6373

- Vaccaro, J. (2014). Queer threads: Crafting identity & community. The Journal of Modern Craft, 7(3), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.2752/174967714X14111311183045

- VanHaitsma, P. (2016). Gossip as rhetorical methodology for queer and feminist historiography. Rhetoric Review, 35(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350198.2016.1142845

- Ward, J. (2010). Gender labor: Transmen, femmes, and collective work of transgression. Sexualities, 13(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460709359114

- Whitehead, J. (Ed.). (2020). Love after the end: An anthology of Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer speculative fiction. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Whitehead, J. (2022). Making love with the land. Knopf Canada.

- Wilbur, M., Small-Rodriguez, D., & Keene, A. (Hosts). (2021, October 26). Sexy sacred [Audio podcast episode]. In All my relations. https://www.allmyrelationspodcast.com/podcast/episode/4bf1a5f6/sexy-sacred

- Wong, A. (2017, October 22). Labor, care work, and disabled queer femmes (No. 6) [Audio podcast episode]. In Disability visibility. Disability Visibility Project. https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2017/10/22/ep-6-labor-care-work-and-disabled-queer-femmes/

- Woolweaver, A. B., Drescher, A., Medina, C., & Espelage, D. L. (2023). Leveraging comprehensive sexuality education as a tool for knowledge, equity, and inclusion. Journal of School Health, 93(4), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13276

- Worthen, M. G. (2022). This is my TERF! Lesbian feminists and the stigmatization of trans women. Sexuality & Culture, 26(5), 1782–1803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-09970-w

- Wright, J., & Greenberg, E. (2023). Non-binary youth and binary sexual consent education: Unintelligibility, disruption and possibility. Sex Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2217748

- Zaino, K., Brockenbrough, E., Cruz, C., Johnson, L. P., & Nicolazzo, Z. (2023). “It’s this practice of being with”: A kitchen-table talk on queer and LGBTQ+ educational justice. Equity & Excellence in Education, 56(1–2), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2022.2158400