ABSTRACT

Learning how to perform the clinical breast examination (CBE) as an undergraduate medical student is an important though complex activity, due to its intimate nature. A Physical Exam Teaching Associate (PETA) - based teaching session addresses this issue and is well founded in literature, though detailed information regarding its development is missing. In this study, we address this gap by providing a comprehensive description of the design and development of a PETA-based session for teaching the CBE. A qualitative study according to the principles of action research was done in order to develop the teaching session, using questionnaires and focus groups to explore participants’ experience. PETAs were recruited, trained and deployed for teaching the CBE to medical students in a small-scale, consultation-like setup. Next, the session was evaluated by participants. This sequence of actions was carried out twice, with evaluation of the first teaching cycle leading to adjustments of the second cycle. Students greatly appreciated the teaching setup as well as the PETAs’ immediate feedback, professionalism, knowledge and attitude. In this study, we successfully designed a PETA-based session for teaching the CBE to undergraduate medical students. We recommend using this strategy for teaching the CBE.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women around the world (Sung et al. Citation2021). Triple assessment, a diagnostic procedure that combines physical examination, imaging and biopsy, is the gold standard for diagnosing breast cancer. Thus, learning how to perform the examination of the breasts and the regional lymph nodes is an important part of any medical curriculum. Due to the intimate nature, however, learning to perform the clinical breast examination (CBE) can be a confronting experience for students both male and female. When learning the CBE, students report anxiety (Pugh and Salud Citation2007), discomfort (Dabson et al. Citation2014), and a lack of confidence in their own skills (Wiecha and Gann Citation1993). This in turn has the potential to impede the students’ learning process and performance (Ambrose et al. Citation2010). Careful consideration of the teaching strategy is therefore necessary.

Physical Exam Teaching Associates (PETAs) are particularly useful for teaching intimate examinations such as the CBE. PETAs are nonprofessionals, trained to instruct a small group of students on a specific part of the physical examination by using their own body as a teaching tool. Students practice the examination on the PETA, while receiving immediate feedback on their skills. PETAs also address the communication skills needed to provide a comfortable exam in a standardized manner (Hopkins et al. Citation2021; Lioce et al. Citation2020). Thus, PETAs can create a supportive, non-threatening environment that is conducive to learning (Jha et al. Citation2010).

Jha et al. (Citation2010) conducted a systematic review in order to integrate the evidence on the role of PETA involvement in the teaching and assessing of intimate examination skills of health care professionals. They provide a summary of the evidence for the positive impact of PETA involvement in teaching CBE skills, both in terms of student satisfaction as well as improvement in technical competence. Using PETAs improves learners’ CBE skills performance (Ault et al. Citation2002; Coleman et al. Citation2004; Costanza et al. Citation1999; Pilgrim et al. Citation1993; Sachdeva et al. Citation1997; White et al. Citation2008) and professionalism (Sachdeva et al. Citation1997). Furthermore, students learning the CBE with PETAs evaluate their program positively (Ault et al. Citation2002; Costanza et al. Citation1999; Sachdeva et al. Citation1997).

Though there is ample evidence for the effectiveness of a PETA-based session for teaching the CBE, less is known about its development and implementation. Both Robertson et al. (Citation2003) and Hendrickx et al. (Citation2006) describe the development of an overarching PETA-based program for teaching various intimate examinations (breast, gynecological, urological and/or rectal examination). However, these articles provide little information regarding the development of a PETA-based teaching session specifically for the CBE. Sarmasoğlu et al. (Citation2016) explored the feasibility and efficacy of the first PETA-based CBE training in a graduate nursing program, however, only one PETA was trained and information regarding recruitment and training is largely missing. Therefore, a more detailed description of the key elements regarding the development of a PETA-based teaching session is still missing for the CBE.

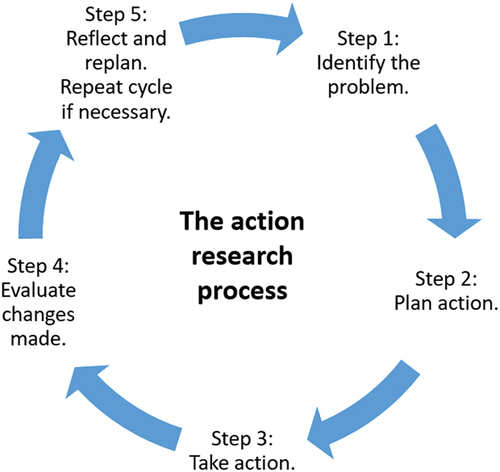

The aim of the present study was to design a high quality PETA-based session for teaching the CBE, thereby providing a detailed description of the methods of recruitment, training, and deployment of PETAs in the session. Additionally, we present the participants’ evaluation of the final PETA-based session in order to demonstrate whether participants themselves supported the main design of the teaching setup. The PETA-based session was designed using the principles of action research. Action research uses a scientific approach to identify problems and develop solutions together with those who experience these issues directly (Coghlan and Brannick Citation2005). A cyclical five-step process is used for identifying the problem, planning action, taking action, evaluating the action, and finally reflecting and replanning ().

Materials and methods

Action research

A qualitative study according to the principles of action research was conducted in order to develop a PETA-based session for teaching the CBE. The strength of action research lies in its focus on generating solutions to practical problems and its ability to empower practitioners – getting them to engage with research and subsequent development or implementation activities (Meyer Citation2000). It focuses on research in action, rather than research about action, and uses a flexible circular process that allows for continuing improvement by drawing on the participant’s experience (Coghlan and Brannick Citation2005, ). As McNiff and Whitehead (Citation2005, 3) point out, action research “is done by people who are studying themselves and their work, and asking questions about what they are doing, why they are doing it, and how they can improve it”. Action research typically draws on a variety of data collection methods such as focus groups, observation and questionnaires (Meyer Citation2000).

Development of the teaching session

The development of the PETA-based session was done in a series of two action research cycles based on the process seen in , by a content development team, consisting of three clinical skills teachers (first, fourth and fifth author) and an educational researcher (second author). The first cycle took place in the academic year 2019–2020 and consisted of a small-scale pilot study with 48 students and 6 PETAs. Evaluation of the first cycle by students and PETAs allowed us to determine challenges and make relevant changes where necessary. This led to the second action research cycle in the academic year 2020–2021, involving 144 students and 11 PETAs. Evaluation of the second cycle led to insights and recommendations for further implementation.

Study participants

The study participants were second-year undergraduate medical students starting their 8-week block on Growth and Development in a curriculum designed around principles of problem-based learning. The students had no prior education regarding CBE skills or exposure to patients with breast pathology. All second-year students were eligible to take part in the study. Following principles of self-directed learning, participation for all clinical skills training sessions is voluntary at Maastricht University, with students registering for sessions themselves. In practice this meant students could choose whether they wanted to participate in the PETA-based teaching session or the conventional manikin-based teaching session.

Evaluation of the teaching session

Both questionnaires and focus groups were used to investigate the opinions of the larger student population as well as explore the experience of a small group of students in-depth.

Following participation in the teaching session, students could fill out a voluntary and anonymous questionnaire assessing their views on the training session. The questionnaire included an overall score on a visual analogue scale, graded from 1–10, items using a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neutral, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree), and close-ended questions. Students were also offered the opportunity to comment on various aspects of the training session. The open-ended questions were analyzed thematically by the content development team (Kiger and Varpio Citation2020).

After attending the teaching session, students were invited to participate in a focus group in order to share their experiences of the session. The focus group was led by a moderator (second author), with one teacher from the content development team being present as well. Neither of these had an assessment role in relation to the students. Student participation was voluntary. No compensation was offered. An interview guide was outlined by the content development team prior to the focus group. The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used to identify themes (Kiger and Varpio Citation2020; Stalmeijer, Mcnaughton, and Van Mook Citation2014). The content team familiarized themselves with the data, generated initial codes, searched for themes and reviewed these. Themes were defined, compared and contrasted. Finally, the write-up of the report began. Data collection ceased when thematic saturation was reached. Member checking was used to check the fit between participants’ views and our presentation of them.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Dutch ethical review board for medical education (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medisch Onderwijs), file number 2020.3.3. Informed consent was obtained from all students and PETAs participating in this study.

Results

Step 1: identifying the problem

In our research setting, second year undergraduate medical students learned the CBE by practicing on manikins. Optionally, those students that felt comfortable could also practice the CBE on each other. This setup posed various challenges: manikins lack realism, and not all students feel comfortable examining their peers. Hence, we wanted to explore a more standardized approach for teaching the CBE, aiming to ensure an equivalent opportunity for all students to practice the examination. Furthermore, we aimed to adopt a teaching strategy in line with a competency-based curriculum, with a focus on integration of skills.

Step 2: planning action – recruitment and training of PETAs

Because our aim was to recruit women who possessed good communication and feedback skills as well as prior experience interacting with students, we recruited women from Maastricht University’s existing pool of gynecology PETAs and simulated patients. This was done by an open application procedure. Based on the findings of Robertson et al. (Citation2003) and Hendrickx et al. (Citation2006), the following selection criteria were used. We sought motivated women with enthusiastic personalities that felt comfortable undergoing the breast examination. Importantly, they had to be capable of creating a safe learning environment as well as taking the lead in the students’ learning process. Furthermore, they had to be proficient in giving high quality feedback. Additionally, the PETAs were required to take part in the national screening program for breast cancer. PETAs with a history of breast-related disease were not excluded, provided there was one healthy breast for students to examine. Payment details were communicated prior to selection of the PETAs. Six out of twenty applicants fulfilled the aforementioned criteria and were selected for the first cycle.

The selected PETAs took part in a series of four training workshops of 1.5 hours each, under the supervision, support and guidance of the content development team (). These training workshops were designed by the development team in partnership with staff from the Maastricht Oncology Center.

Table 1. Final training course for PETAs.

The first three training workshops focused on the main aims of the teaching session, medical terminology and anatomy, as well as practice in giving feedback, history taking and the CBE. The final training session was dedicated to simulating a teaching session with student volunteers. It was important for PETAs to thus experience the setting prior to teaching the actual sessions. This enabled them to adjust their approach where necessary. A specialized nurse from the Maastricht Oncology Center examined each PETA. This was done for two reasons. First, to detect any possible palpable abnormalities, and second, to familiarize the PETA with her own anatomy and physical examination findings, so that she could help students when describing these characteristics.

Ultimately, the aim of training the PETAs was for them to become skilled in teaching the CBE and in guiding the student throughout this process. The PETAs were not trained to have expert knowledge regarding breast pathology, and this was communicated to them during their training course.

Step 3: taking action – the PETA-based teaching session

shows the composition and course of the PETA-based teaching session. Each PETA-based teaching session lasted 1.5 hours with approximately 12 students per session, and commenced with a short plenary session together with a clinical skills teacher who presented an outline of the session and briefly revised the CBE.

Table 2. The PETA-based teaching session for students.

Next, the students split into small groups of 2–3 students per PETA. After an introduction between the PETA and the students, both students performed history taking together. Next, the PETA guided the students through the CBE. Each student performed the full examination of the breasts and the regional lymph nodes, with immediate feedback from the PETA. While one student performed the examination and communicated with the PETA, the other student observed actively. Students also had the opportunity to practice on a manikin with palpable breast lumps. The clinical skills teacher rotated among the various groups to answer any questions that were out of the scope of the PETA’s knowledge. Finally, the PETA debriefed the session together with the students that were assigned to her.

Step 4: evaluation of action

After participating in the PETA-based teaching session, students could fill out a questionnaire assessing their views on the training session (for questions, see ). Two focus groups took place with five students each. We present a summary of the themes that emerged through thematic analysis of the data here.

Table 3. Final teaching setup questionnaire: answers to closed-ended questions.

Table 4. Final teaching setup questionnaire: the open-ended questions.

Students were highly appreciative of the training session. They especially valued the safe learning environment, the PETAs’ professionalism, their immediate feedback, and the fact that they felt comfortable with the examination. Though students appreciated the small-scale setup and the overall structure of the session, they felt that information about breast pathology was missing, e.g. what happens when a breast lump is identified through the CBE.

After completion of the first action research cycle, the PETAs evaluated their own training course and the teaching session for students during a 1.5-hour debriefing session with three teachers from the content development team. They were very appreciative of the various training workshops and enthusiastic about the opportunity to guide the students throughout the CBE. They did however feel that more time was needed for practicing the CBE in their preparatory training course, especially through peer physical examination.

Step 5: Reflecting and replanning – adjustments for cycle 2

The development team jointly reviewed the evaluation data from both students and PETAs. Many insights were gained based on the steps of the first action research cycle. Because of the positive evaluation of the first action research cycle, a second, larger scale cycle was developed. The adjustments for the second cycle are summarized in .

Figure 2. Flow chart showing the sequence of actions taken for the development of the PETA-based teaching session.

Recruitment of more PETAs, leading to a total of eleven PETAs.

Training course for PETAs: based on the PETA’s evaluation, the training course was adapted to include more time for practicing CBE skills in each workshop of the course. The final training course for PETAs is shown in .

PETA-based teaching session for students: because students expressed a wish for a deeper understanding of breast pathology, a flipped classroom approach with blended learning elements (Hew and Lo Citation2018) was introduced. In the second action research cycle, the teaching session began with a preparatory e-learning assignment that the student was expected to complete prior to attending the on-campus teaching session. The preparatory assignment started with a brief explanation of the learning goals and the setup of the on-campus teaching session. Next, it followed a fictional patient with a self-discovered lump in her breast, covering history taking, an outline of the CBE with additional explanation highlighting possible signs of breast cancer, and the course of action upon referral to the breast clinic. Additionally, the assignment included information about the national screening program for breast cancer. Following the e-learning, students attended the on-campus part of the teaching session. The adjusted PETA-based teaching session is shown in .

Evaluation of the teaching session: the student questionnaire and focus group interview guide were adapted.

Action research cycle 2: evaluation of the final teaching setup

Questionnaires were completed by 118 out of 144 students, with an overall response rate of 82 percent. One focus group with five students took place, despite offering multiple opportunities to join one of three focus groups.

shows the results of the closed-ended questions of the questionnaire. The following themes emerged through analysis of the open-ended questions in the questionnaire () and the focus group data.

Students highly valued the teaching session. They especially appreciated the safe learning environment that the PETA was able to create, and the immediate one-on-one feedback from the PETA.

The PETA herself would be giving us feedback in the moment, and you have time to really communicate with her. This was nice because it could be sensitive, and it’s also a new examination for us.

It’s incredibly helpful that the person who you’re doing the examination on can guide you, (…) since they know how the examination should feel.

Furthermore, students valued the professionalism, knowledge and attitude of the PETA.

They really know what they’re doing.(Student C)

The situation was also perceived as “more serious”, because students had to examine a “stranger”. The PETA’s open attitude and relaxed demeanor throughout the examination was very helpful to students, especially in reducing their stress levels.

They make it less nerve-racking. They also give a real life experience and humanized the process.

Students also appreciated being able to practice on a “real person” and not only on a manikin.

I realized that the most important part was having an actual “human being” aspect to the training. We actually had to speak to a patient and make sure we were doing the examination correctly.

Students welcomed the small-scale consultation-like setup with both history taking and practicing the CBE.

After the training we really felt like we could perform this examination again.

One of the PETAs had a history of breast cancer and a mastectomy. Students highly appreciated the opportunity to ask her questions and to practice the CBE on the non-affected breast.

When asked to indicate points for improvement, students indicated that separate, dedicated time would be needed for discussing the wider context of breast pathology, because their minds were occupied with practicing the CBE on an actual person. Finally, they expressed the need for a more uniform approach regarding the regional lymph node examination, as the sequence they were taught had varied between the various PETAs.

In the second action research cycle, the PETAs evaluated their own training course and the teaching session for students during a 1.5-hour debriefing session with a teacher from the content development team. The PETAs were highly appreciative of their training course. They were enthusiastic about the possibility to teach the CBE. Following their interactions with the students, they felt motivated to continue teaching in this setup. The only recommended adaptation was to include a more protocoled strategy for teaching the sequence of the regional lymph node palpation.

It was very helpful to discuss and practice examination techniques with teachers as well as other PETAs.

I appreciated the physical examination by the specialized nurse. It helped me to get to know my own body better.

Action research cycle 2: suggestions for future implementation

Many valuable lessons were learned based on the evaluation of cycle 2. We suggest the following adaptations for future implementation of the PETA-based teaching session:

Reinforcement of the need for a protocoled training of PETAs in order to avoid any inconsistencies in the PETA’s teaching

Ensuring dedicated time for an adequate discussion of breast pathology

Our intention is to do a third cycle in the action research process by adapting the session according to the lessons learned and implementing it for all our second-year medical students. The teaching session will be entirely PETA-led. The role of the clinical skills teacher was first, to explain the setup, and second, to answer any possible questions about breast pathology. Based on our experiences so far, we hypothesize that the first can be done by the PETA herself, and the second need can be met by providing a separate educational activity dedicated to breast pathology.

Discussion

The effectiveness of using PETAs for teaching CBE skills is well-founded in literature (Ault et al. Citation2002; Coleman et al. Citation2004; Costanza et al. Citation1999; Jha et al. Citation2010; Pilgrim et al. Citation1993; Sachdeva et al. Citation1997; White et al. Citation2008). Less is known about the development and implementation of such a teaching session (limited information is provided by Hendrickx et al. Citation2006; Robertson et al. Citation2003; Sarmasoğlu et al. Citation2016). We aimed to address this gap in the literature by providing a detailed description of the methods of recruitment, training, and deployment of PETAs. By going through two action research cycles, we were able to define points for improvements and adjust the initial design of both the training course for the PETAs, as well as the teaching session for students. Students highly valued the final teaching setup.

This study has a number of potential limitations. First, the recruitment of women from our faculty’s existing pool of gynecology PETAs and simulated patients. Thus, we were already familiar with these women, which in turn helped us in the recruitment and training process. This process will inevitably vary for others, depending on the design of their clinical skills curriculum and whether there is any prior experience with PETAs. Second, following principles of self-directed learning, participation for clinical skills training sessions is voluntary at our institution, with students registering for sessions themselves. This could have led to a bias, with interested students registering for the PETA-based sessions, thus influencing the results. Third, the low number of students participating in the second action research cycle focus group, despite offering multiple opportunities at different times, dates and periods in their academic calendar. Reasons given for not being able to attend were busy schedules and study-related deadlines. The main themes identified through thematic analysis of the focus group data were however consistent with the questionnaire results as well as the evaluation outcome of the first action research cycle teaching setup.

Recruitment and training of PETAs is a time-intensive process, but, at the same time, it is the key to success. Going through a thorough recruitment process with clear selection criteria enabled us to select women who possess the qualities that are necessary to become a good PETA. Developing a PETA-based teaching session means investing time and funds in a high-quality training course for the PETAs themselves, which should include plenty of opportunities to practice the CBE on peers. Additionally, providing a simulated session with students during the training course allows PETAs to experience the setting and adjust their approach where necessary before starting the actual teaching sessions. Furthermore, the training course should be protocoled in order to avoid any inconsistencies in the PETA’s teaching. Hopkins et al. (Citation2021) describe the importance of establishing standards of best practice for programs using PETAs. Those interested in developing their own program can use their guidelines to shape practices within their local context.

Performing an intimate and sensitive examination such as the CBE for the first time can be a stressful experience. In our situation, we found that the PETA’s behavior was key in reducing students’ stress levels. This is in line with previous findings (Carr and Carmody Citation2004; Theroux and Pearce Citation2006; Wykurz and Kelly Citation2002; Wånggren et al. Citation2005). The fact that they were friendly, inviting, and enthusiastic about the possibility to teach, and the fact that they felt comfortable undergoing the CBE all contributed to the reduction of students’ stress. Additionally, the small-scale, consultation-like setup facilitated the stress-reducing interactions with the PETA. Further studies could focus on a more in-depth analysis of the stress-reducing behavior of the PETA, and which elements in a PETA’s interaction with the student could further facilitate the students’ learning process, e.g. by means of observation, qualitative interviews and focus groups with students and PETAs.

When designing a PETA-based teaching session, one should avoid addressing too many learning goals at once. In our flipped classroom teaching session students could learn about the context of breast pathology. In their evaluation, however, students indicated that separate, dedicated time would be needed for discussing the wider context of breast pathology, because they were primarily focused on practicing the CBE. In a competency-based curriculum, the ideal setup might be to provide a PETA-based session primarily focused on learning CBE skills, along with dedicated time focused on the wider context of breast pathology. Next, students could practice the examination on a patient in a guided and ethically appropriate setting.

Providing a PETA-based teaching session is both time intensive and expensive, and therefore requires committed funding. Teaching an examination as intimate as the CBE requires a careful weighing of the pros and cons of the teaching strategy. Costanza et al. (Citation1999) provides helpful insights into the costs of such a teaching program. Much can be also learned from studies that describe the sustainability of other teaching programs with PETAs (e.g. Janjua et al. Citation2018). At our faculty, we have concluded that the benefits of using PETAs outweigh the costs. We plan to continue the implementation of the teaching setup for all students. It is our hope that the information provided in this study will help medical educators and planners to develop their own PETA based teaching session for teaching the CBE.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the dedicated women who participated as PETAs and all the students who provided valuable insight into their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ambrose, S. A., M. W. Bridges, M. DiPietro, and M. K. Lovett. 2010. How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ault, G. T., M. Sullivan, J. Chalabian, and K. A. Skinner. 2002. A focused breast skills workshop improves the clinical skills of medical students. The Journal of Surgical Research 106 (2):303–07. doi:10.1006/jsre.2002.6472.

- Carr, S. E., and D. Carmody. 2004. Outcomes of teaching medical students core skills for women’s health: The pelvic examination educational program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 190 (5):1382–87. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2003.10.697.

- Coghlan, D. B., and T. Brannick. 2005. Doing action research in your own organization. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Coleman, E. A., C. B. Stewart, S. Wilson, M. J. Cantrell, P. O’-Sullivan, D. O. Carthron, and L. C. Wood. 2004. An evaluation of standardized patients in improving clinical breast examinations for military women. Cancer Nursing 27 (6):474–82. doi:10.1097/00002820-200411000-00007.

- Costanza, M. E., R. Luckmann, M. E. Quirk, L. Clemow, M. J. White, and A. M. Stoddard. 1999. The effectiveness of using standardized patients to improve community physician skills in mammography counseling and clinical breast exam. Preventive Medicine 29 (4):241–48. doi:10.1006/pmed.1999.0544.

- Dabson, A. M., P. J. Magin, G. Heading, and D. Pond. 2014. Medical students’ experiences learning intimate physical examination skills: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education 14:39. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-39.

- Hendrickx, K., B. Y. De Winter, J. J. Wyndaele, W. A. Tjalma, L. Debaene, B. Selleslags, F. Mast, P. Buytaert, and L. Bossaert. 2006. Intimate examination teaching with volunteers: Implementation and assessment at the University of Antwerp. Patient Education and Counseling 63 (1–2):47–54. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.009.

- Hew, K. F., and C. K. Lo. 2018. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: A meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education 18 (1):38. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z.

- Hopkins, H., C. Weaks, T. Webster, and M. Elcin. 2021. The association of standardized patient educators (ASPE) gynecological teaching associate (GTA) and male urogenital teaching associate (MUTA) standards of best practice. Advances in Simulation (London, England) 6 (1):23. doi:10.1186/s41077-021-00162-4.

- Janjua, A., T. Roberts, N. Okeahialam, and T. J. Clark. 2018. Cost-Effective analysis of teaching pelvic examination skills using Gynaecology Teaching Associates (GTAs) compared with manikin models (The CEAT Study). BMJ Open 8 (6):e015823. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015823.

- Jha, V., Z. Setna, A. Al-Hity, N. D. Quinton, and T. E. Roberts. 2010. Patient involvement in teaching and assessing intimate examination skills: A systematic review. Medical Education 44 (4):347–57. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03608.x.

- Kiger, M. E., and L. Varpio. 2020. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher 42 (8):846–54. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030.

- Lioce, L., J. Lopreiato, D. Downing, T. P. Chang, J. M. Robertson, M. Anderson, D. A. Diaz, A. E. Spain, and The Terminology and Concepts Working Group. 2020. Healthcare simulation dictionary –Second edition. AHRQ Publication No. 20-0019. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- McNiff, J., and J. Whitehead. 2005. Action research for teachers: A practical guide. 1st ed. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Meyer, J. 2000. Qualitative research in health care. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) 320 (7228):178–81. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178.

- Pilgrim, C., C. Lannon, R. P. Harris, W. Cogburn, and S. W. Fletcher. 1993. Improving clinical breast examination training in a medical school: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 8 (12):685–88. doi:10.1007/BF02598289.

- Pugh, C. M., and L. H. Salud. 2007. Fear of missing a lesion: Use of simulated breast models to decrease student anxiety when learning clinical breast examinations. The American Journal of Surgery 193 (6):766–70. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.12.033.

- Robertson, K., K. Hegarty, V. O’-Connor, and J. Gunn. 2003. Women teaching women’s health: Issues in the establishment of a clinical teaching associate program for the well woman check. Women & Health 37 (4):49–65. doi:10.1300/J013v37n04_05.

- Sachdeva, A. K., P. J. Wolfson, P. G. Blair, D. R. Gillum, E. J. Gracely, and M. Friedman. 1997. Impact of a standardized patient intervention to teach breast and abdominal examination skills to third-year medical students at two institutions. American Journal of Surgery 173 (4):320–25. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00391-1.

- Sarmasoğlu, Ş., L. Dinc, M. Elçin, G. Celik, and I. Polonko. 2016. Success of the first Gynecological Teaching Associate Program in Turkey. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 12 (8):305–12. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2016.03.003.

- Stalmeijer, R. E., N. Mcnaughton, and W. N. Van Mook. 2014. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Medical Teacher 36 (11):923–39. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165.

- Sung, H., J. Ferlay, R. L. Siegel, M. Laversanne, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal, and F. Bray. 2021. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71 (3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660.

- Theroux, R., and C. Pearce. 2006. Graduate students’ experiences with standardized patients as adjuncts for teaching pelvic examinations. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 18 (9):429–35. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00158.x.

- Wånggren, K., G. Pettersson, G. Csemiczky, and K. Gemzell-Danielsson. 2005. Teaching medical students gynaecological examination using professional patients-evaluation of students’ skills and feelings. Medical Teacher 27 (2):130–35. doi:10.1080/01421590500046379.

- White, C. B., P. T. Ross, J. A. Purkiss, and M. M. Hammoud. 2008. Improving medical students’ competence at breast examination. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 102 (2):173–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.03.007.

- Wiecha, J. M., and P. Gann. 1993. Provider confidence in breast examination. The Family Practice Research Journal 13 (1):37–41.

- Wykurz, G., and D. Kelly. 2002. Developing the role of patients as teachers: Literature review. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) 325 (7368):818–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7368.818.