ABSTRACT

Heterotopic pregnancies are rare pathological pregnancy disorders in clinical practice. However, the number of cases has increased with the widespread use of ovulation induction drugs in recent years. The clinical manifestations of heterotrophic pregnancies are diverse and easy to missed or misdiagnosed. A 33-year-old married Gravida1 Para 0 + 0 patient was admitted on December 8, 2020 with intermittent abdominal pain 18 days after uterine curettage for complete hydatidiform mole of 8 weeks gestation. She had ovulation-promoting drugs prior to the index pregnancy. Hysteroscopic-directed endometrial biopsy and laparoscopic left tubal surgery were offered to her; and she is being followed up with serial pelvic ultrasounds and β-Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin (βHCG) assays. This case study presents a case of intrauterine hydatidiform mole complicated with tubal pregnancy to highlight the problems associated with its diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Heterotopic pregnancy (HP) is rare and was first reported by Duverney during an autopsy in 1708 (Cruz, Sanchez, and Perez Citation2006). HP is a pathological pregnancy disorder in which the fertilized eggs are simultaneously implanted as intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy, and of these, 98 percent are intrauterine pregnancies combined with tubal pregnancies (Brown and Wittich Citation2012). Its incidence is about 1/30000 of natural pregnancies (Levine Citation2007). However, with the widespread use of assisted reproductive techniques, such as in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) and ovulation induction therapy, the incidence of HP has increased to 0.2 percent-1 percent (Deng Citation2016; Maruotti et al. Citation2010). Intrauterine hydatidiform mole with tubal pregnancy is rare in clinical practice, and only three cases reports have been reported in China and abroad (Li, Wang, and Yang Citation2003; Liu et al. Citation2006; Nicks, Fitch, and Manthey Citation2009). This study presents a case of intrauterine hydatidiform mole complicated with tubal pregnancy after ovulation induction and proposed suggestions for diagnosis and treatment.

Case report

A 33-year-old married Gravida1 Para 0 + 0 female patient was admitted on December 8, 2020 with intermittent abdominal pain 18 days after uterine curettage on November 20, 2020 for hydatidiform mole of 8 weeks gestation. Her last menstrual period was on September 9, 2020 and she had ovulation promoting drugs (Clomiphene Citrate) for her irregular menstrual cycle prior to the index pregnancy. The patient’s previous childbearing history included no full-term or premature delivery, no abortion, and no children. Her gynecological conditions included marital outlet, a patent vagina with no congestion of the vaginal mucosa, a smooth cervix, the uterus in an anterior position, the normal size, no tenderness, thickening, and mild tenderness in the left adnexal area, and no palpable abnormality in the right adnexal area.

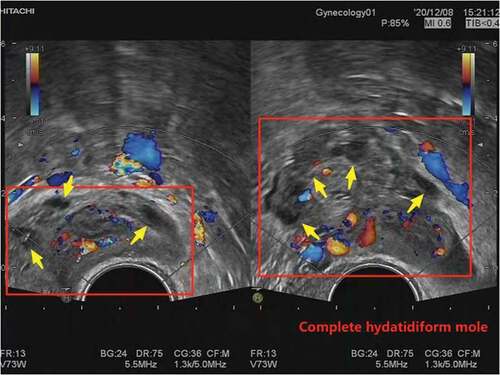

On November 20, 2020, a gynecological ultrasound revealed a solid cystic mass of about 5.8 × 2.8 cm in the uterine cavity and a blood human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) 132528 IU/L. A diagnosis as “hydatidiform mole” was made. She had uterine curettage under ultrasound monitoring on November 20, 2020 and was followed up with serial pelvic ultrasounds and βHCG assays. The histology report confirmed a “complete hydatidiform mole” (see ). The 2nd postoperative day blood βHCG was 19,700.7 IU/L. The repeat 4th postoperative day ultrasound showed that the endometrial echo was not uniform, with thickness of 0.6 cm; and a heterogeneous echo about 1.4 × 1.3 cm in size was observed beside the left ovary with unclear demarcation from the left ovary. Fourteen days after the curettage, she experienced pain in the left lower abdomen which was accompanied by small vaginal bleeding. There was neither weakness nor fainting attack. The blood βHCG changed from 5946.74 IU/L on the 10th postoperative day to 4749.88 IU/L on the 17th postoperative day.

Figure 1. The ultrasound image of the patient. B-ultrasound showed a honeycomb, small round fluid dark area, and cloud-like hypoechogenic areas in the uterine cavity (inside the red box, referred to by the yellow arrow).

The repeat gynecological ultrasound done 17 days after uterine curettage still showed the heterogeneous hyper-echogenicity mass beside the left ovary of about 3.3 cm × 2.1 cm, with unclear demarcation from the left ovary, and the faveolate hyper-echogenicity of about 1.6 × 1.3 cm was visible inside.

The regional hospital did not identify the cause of the patient’s postoperative abdominal pain. Then the patient was then transferred from a small regional hospital to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. On admission, the blood βHCG was 5125 mIU/mL, and the gynecological ultrasound showed a 3.0 × 3.5 × 2.8 cm heterogeneous echogenic mass in the left adnexal region, within which a 1.6 × 1.5 cm hyperechoic heterogeneous area with a faveolate shape was seen, surrounded by abundant blood flow signals, adjacent to the ovary.

Chest computerized tomography (CT) showed small nodules in both lungs. The patient’s pathological section from the local hospital revealed villous tissue in the submitted tissue, some villous trophoblastic cells were multipolar, and immunohistochemistry P57 in the original unit revealed positive foci of stromal cells and trophoblastic cells, considered as early complete hydatidiform mole. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed luteal cyst with hemorrhage in the left adnexal area and an ectopic pregnancy.

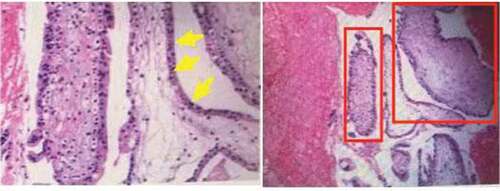

On December 11, 2020, a combined hystero-laparoscopic exploration was performed under general anesthesia. The laparoscopic view showed old hematocele in the pelvic cavity of volume of about 50 mL. The ampulla of the left fallopian tube was thickened, and a purple-blue mass of about 3 × 2 × 2 cm3 in volume was seen. Neither bleeding nor exudation was seen at the tubal fimbria. Dark red blood clots were seen attached on the surface of the left ovary and on the surface of the left posterior wall of the uterus near the ovarian ligament. The uterus was enlarged as large as more than 40 days of gestation, with smooth surface, and no mass was observed. The right fallopian tube and ovary showed no significant abnormality. Hysteroscopy showed smooth cervix, normal cervical canal morphology, and no obvious superfluous organisms. The morphology of the uterine cavity was basically normal, with decidual-like tissue in the posterior wall and tortuous thickened vessels with a small amount of blood oozing in the left uterine horn. Laparoscopic left tubal fenestration embryo extraction and hysteroscopic intrauterine tissue biopsy were performed. The histology reports confirmed the left tubal tissue as ectopic pregnancy while the contents of the intrauterine biopsy were denatured, necrotic and were considered as uterine cavity residues ().

Figure 2. Pathological section image of the patient. The perivillous trophoblasts were severely hyperplastic (the yellow arrows), and the villi were edematous and enlarged (inside the red boxes).

The pathological section and a short tandem repeat (STR) molecular test conducted at Peking University Third Hospital suggested that: (1) the uterine contents were monospermic complete hydatidiform mole. (2) the left tubal pregnancy tissue was clots and villi which were consistent with ectopic pregnancy. Forty-nine days after the laparoscopic procedure for ectopic pregnancy, the blood βHCG of the patient was retested and it decreased to normal level. She is still under follow-up.

Discussion and literature review

The pathogenesis of heterotopic pregnancy is unclear. Based on a comprehensive literature review, the possible pathogenesis could be: pathological or physiological, or pathological factors where at least two eggs are expelled from the ovary and fertilized or one fertilized egg splits into two separate oocytes and are implanted in the uterine cavity and outside the uterine cavity, respectively. Pathological damages to the fallopian tubes such as salpingitis, tubal epithelial cell, and ciliary damage and tubal pathological stenosis are risk factors for ectopic pregnancy. Iatrogenic factors, for example, multiple egg expulsions caused by ovulation induction therapy and IVF-ET therapy in assisted reproductive technology, which can result in HP (Černiauskaitė et al. Citation2020; Kajdy et al. Citation2021). The uses of ovulation-promoting drugs and luteal progesterone supports makes estrogen and progesterone in patients to be higher than the physiological levels. The increased estrogen and progesterone concentrations in the body affect not only the implantation of embryos, but also the peristalsis of the fallopian tubes, which can result in an increased chance of false blockage of high estrogen and ectopic pregnancy. Researchers have reported a positive correlation between the increased incidence of HP and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (Fauque et al. Citation2020).

Hydatidiform mole is a disorder of embryonic trophoblastic cells. The incidence of hydatidiform mole in China is 0.78% and usually occurs in the uterine cavity. The pathogenesis of hydatidiform mole is associated with the patient’s oncogene proteins; maternal gene deletion and paternal gene overexpression are also causes of trophoblast proliferation. Two cases have been reported in patients treated with clomiphene, an ovulation-promoting drug, before pregnancy. This drug promotes the ovary to expel multiple eggs, thereby increasing the incidence of immature or empty eggs, which may be a mechanism of hydatidiform mole development as in this case report (Wang, Zuo, and Wang Citation2006). The case reported here is an HP after ovulation induction with ovulation-promoting drugs, which is the inducement and the pathological basis of HP.

HP has clinical features of intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies. Abdominal pain and sudden shock are the primary clinical symptom. The four main clinical feature of HP include: (1) uterine enlargement consistent with amenorrhea time; (2) uterine enlargement with ovarian development of two corpora lutea; (3) no withdrawal vaginal bleeding after ectopic pregnancy surgery; and (4) intrauterine pregnancy with unexplained intra-abdominal bleeding, and even shock. Liu et al. (Citation2020) found asymptomatic intrauterine combined with tubal pregnancy in 19.2 percent of patients (23 out of 120 patients). The most common symptom was vaginal bleeding (43.1 percent), and 10.8 percent of the patients were treated by blood transfusion for shock.

Current advances in the use of high-resolution transvaginal ultrasound technology provide objective means for early diagnosis of HP, and approximately 40 percent of HP patients are diagnosed by ultrasonography. Our patient was referred from a local hospital, and this may explain the difficulties encountered in the late diagnosis of the left tubal ectopic pregnancy. Other reasons for this missed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy are the ectopic gestational sac may be too small and neglected (Pramanick, Peedicayil, and Shah Citation2014) and the formation of enlarged luteinized corpus cysts from ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in patients treated with assisted reproductive technology as in this patient. The persistently high level of βHCG made us to suspect the presence of another pregnancy in this patient.

Monitoring serum βHCG levels is known to be useful in diagnosis of twin pregnancy. A significant increase in the rate of twin pregnancies occurs when serum HCG levels are >200 IU/L on day 12 after embryo transfer (Pramanick, Peedicayil, and Shah Citation2014). We used a combination of hysteroscopic-laparoscopic procedures to make diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and exclude residual hydatidiform moles in this patient. This portrays the difficulties in the diagnosis of HP as in the similar too.

Two cases of hydatidiform mole with ectopic pregnancy were reported in China. In one case, the patient was readmitted to the hospital with acute abdominal pain after uterine curettage for hydatidiform mole, which was confirmed as a rupture of a tubal pregnancy (Song and Luo Citation2013). The blood HCG was significantly elevated in the second case when reexamined after tubal pregnancy surgery. The ultrasound revealed an inhomogeneous echogenic mass in the uterine cavity, which was later confirmed to be a hydatidiform mole after uterine curettage (Li, Wang, and Yang Citation2003). In this case report presented, the first ultrasound indicated a mass in the adnexal area. After the uterine curettage for the hydatidiform mole, the patient was monitored closely. When the blood HCG was found to be elevated and the mass in the adnexal area enlarged. The patient was operated to avoid serious consequences, such as hemorrhaging and shock. The patient is now fully recovered and under postoperative care.

Conclusion

This case report provides insight into the diagnosis, and treatment of HP with the widespread development of assisted reproductive techniques, such as in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer and ovulation-promoting treatment, is increasing the risk. High index of suspicion of HP is very important for early diagnosis and treatment of HP especially when βHCG remained elevated after the initial surgery. Early detection, diagnosis, and treatment are crucial to ensure the patient’s full recovery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown, J., and A. Wittich. 2012. Spontaneous heterotopic pregnancy successfully treated via laparoscopic surgery with subsequent viable intrauterine pregnancy: A case report. Military Medicine 177 (10):1227–30. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00457.

- Černiauskaitė, M., B. Vaigauskaitė, D. Ramašauskaitė, and M. Šilkūnas. 2020. Spontaneous heterotopic pregnancy: Case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas) 56 (8):365. doi:10.3390/medicina56080365.

- Cruz, G. O., G. R. Sanchez, and L. V. Perez. 2006. Heterotopic pregnancy. Ginecologia y obstetricia de Mexico 74 (7):389–93.

- Deng, S. 2016. Emergency traps for simultaneous ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies after IVF-ET. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine 25:465–68.

- Fauque, P., J. De Mouzon, A. Devaux, S. Epelboin, M. J. Gervoise-Boyer, R. Levy, M. Valentin, G. Viot, A. Bergère, C. De Vienne, et al. 2020. Reproductive technologies, female infertility, and the risk of imprinting-related disorders. Clinical Epigenetics 12 (1):191. doi:10.1186/s13148-020-00986-3.

- Kajdy, A., K. Muzyka-Placzyńska, D. Filipecka-Tyczka, J. Modzelewski, M. Stańczyk, and M. Rabijewski. 2021. A unique case of diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy at 26 weeks – case report and literature review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21 (1):61. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03465-y.

- Levine, D. 2007. Ectopic pregnancy, 1020–47. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders Elsevier.

- Li, H., H. J. Wang, and Y. L. Yang. 2003. Ectopic pregnancy complicated with hydatidiform mole: A case report. West China Medical Journal 18 (3):400.

- Liu, H. Y., F. Z. Cao, Y. L. Zhou, and Q. Zheng. 2006. A case of missed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy combined with gravida. Chinese Journal of Misdiagnosis 6 (12):2247.

- Liu, J., W. L. Zhang, Y. Miao, Y. F. Tong, and X. F. Xiao. 2020. Clinical analysis of intrauterine pregnancy combined with tubal pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Chinese Journal of Family Planning & Gynecotokology 12 (7):34–47.

- Maruotti, G. M., L. Sarno, M. Morlando, A. Sirico, P. Martinelli, and T. Russo. 2010. Heterotopic pregnancy: It is really a rare event the importance to exclude it not only after in vitro fertilization but also in case of spontaneous conception. Fertility and Sterility 94 (3):e49. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.001.

- Nicks, B. A., M. T. Fitch, and D. E. Manthey. 2009. A case of intrauterine molar pregnancy with coexistent ectopic pregnancy. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (3):246–49. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.028.

- Pramanick, A., A. Peedicayil, and A. Shah. 2014. Bilateral tubal pregnancy willi intrauterine pregnancy in a natural conception cycle a long with liver cell failure: Case report and review of literature. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 64 (Suppl 1):50–52. doi:10.1007/s13224-013-0474-3.

- Song, H., and X. Luo. 2013. Misdiagnosis of tubal invasive hydatidiform mole rupture after miscarriage as misdiagnosed as ectopic pregnancy: A case report and literature review. Progress in Obstetrics and Gynecology 7:605–06.

- Wang, G. H., C. T. Zuo, and L. J. Wang. 2006. Co-existence of gravida and fetus after application of ovulation-promoting drugs with two case reports and review of literature. Modern Advances in Obstetrics and Gynecology 15:714–16.