ABSTRACT

Women experiencing homelessness are marginalized not only through their housing status but also through their access and ability to manage their menstrual health. Currently, there are no existing published reviews exploring this topic. This study aimed to begin closing that gap, by systematically reviewing the literature examining women’s experiences of menstruation whilst being homeless. In June 2020 (and updated in December 2022), we conducted comprehensive and systematic searches of four electronic databases: Medline, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsychINFO, from which nine studies were found. The findings were thematically analyzed, using the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research tools (ENTREQ) guidelines. Three themes related to menstrual experiences were found: (1) challenges in the logistics of managing menstruation while homeless, (2) feelings of embarrassment, shame, and dignity linked to maintaining menstrual health, and (3) making do: how people experiencing homelessness manage challenges related to menstruation. We discuss barriers women face in getting necessary products and in accessing private, safe, and clean facilities to manage menstrual health. The study found that women living with homelessness often abandon other basic needs in favor of managing menstruation (i.e. using unsuitable materials, stealing, etc.), which furthers their risk. The findings highlight the need for future research to investigate the experiences of women who are menstruating while being homeless and what support they would find helpful. Results show that it is high time for commissioners and policy-makers to address the provision of menstrual resources as a basic human right.

Introduction

Gender-based health inequalities have serious implications for the health of women all over the world. Health inequalities disproportionately impact women experiencing homelessness (those who are living in inappropriate or temporary accommodation) who are neglected in both research and health care (Duke and Searby Citation2019). Preexisting mental health issues both precipitate homelessness and result from homelessness experience. There is a lack of evidence on specific mental health conditions which are common among this group of underserved women (Duke and Searby Citation2019). However, recent studies have shown that a quarter of women experiencing homelessness have unmet health needs (Vuillermoz et al. Citation2017), they are more likely to experience pregnancy complications (Clark et al. Citation2019), and have double the rate of disability compared to their domiciled counterparts (Guillén, Panadero, and Juan Vázquez Citation2021). Many women experiencing homelessness reported that they had given up on health services and had lower expectations from health-care providers (Vuillermoz et al. Citation2017).

Current literature urges for movement away from stigmatizing language such as ‘menstrual hygiene’ (Thomson et al. Amery, Channon & Puri, Citation2019). Subsequently, throughout this research, we have used ‘Menstrual Health Management’ (MHM); a definition more aligned with this human rights issue, in place of the historic ‘Menstrual Hygiene Management’ (WHO Citation2022).

Period poverty, described as a lack of access to sanitary products due to financial constraints (Royal College of Nursing Citation2021), is a global concern. Menstrual health management (MHM) presents significant challenges to low-income women (Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013). Research on MHM has indicated that many low-income women are regularly unable to afford needed menstrual products. As a result, many women make do with cloth, rags, or toilet paper (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2019). Challenges in affording menstrual products are exacerbated by high taxes and inaccessibility of products. Inadequate MHM provision including water and sanitation facilities in schools compromise girls’ ability to maintain period health and privacy in many low-income settings. UNICEF highlights how profound this problem is and the need for research, programming, and policy agendas to improve this issue for adolescent girls (Sharma et al. Citation2020). However, there is currently no such call from organizations to improve this issue for people living with homelessness. Poor MHM can result in negative health outcomes including infections (Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013).

To-date, research exploring period poverty is largely medicalized and serves one of the two populations: middle class, cisgender, white women in the Global North or women experiencing extreme poverty in the Global South. Crucially, the research misses menstruating people in the Global North who are socio-economically marginalized, including those experiencing homelessness (Vora Citation2020). This is particularly relevant given the key health and hygiene conditions that are often reported in homeless shelters, including insufficient ventilation systems, unhygienic bedding, and overcrowding, which can lead to problems such as tuberculosis infections and skin diseases (Moffa et al. Citation2019). Those who menstruate while homeless have to navigate an additional layer of complexity that can increase their vulnerability and to-date there have not been any published reviews aiming to understand this population’s experience. Therefore, the aim of this qualitative evidence review is to synthesize research exploring the menstrual experiences of people living with homelessness.

Materials and methods

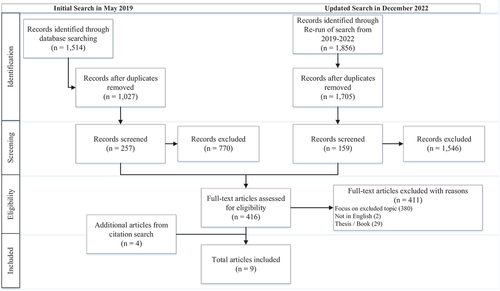

We conducted a search of four electronic databases: Medline, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsychINFO. Search terms were defined by scanning keywords from relevant papers during initial scoping searches (see Appendix for search terms). Keywords were divided into three categories: (1) population, (2) context, and (3) outcome.

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in two stages: (1) scanning of titles and abstracts and (2) full-text reviewing of studies against exclusion/inclusion criteria. Searches identified all available studies published. Limits added to all searches included studies that have been published between 2000 and 2022 in English.

The reference lists of all included studies were also scanned to identify potentially relevant studies. Search results were imported into EndNote (bibliographic software) and Rayyan (Ouzzani et al. Citation2016), where following the PRISMA (Moher et al. Citation2009) flowchart, potentially relevant titles and abstracts were screened. We then independently screened full-text articles against the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The original search of the electronic databases was conducted in June 2020 by SB, PHJ, and GO. An updated search was conducted in December 2022 by FG and JT; one new article was included which informed the development of the pre-established themes, as shown in .

Studies were included if they were empirical research, included post-menarcheal women (including adolescents) and a topic on reproductive health/menstrual practices (e.g., menstrual health) and contraception provision/use/experiences with. Focusing on women’s use and experiences (impact on menstruation, the IUD, etc.). Studies that focused on homeless populations (i.e. those who are living in inappropriate or temporary accommodation) were included.

Studies were excluded if they; did not focus on homelessness, included only menopausal women, post-menopausal and elderly populations, only male participants, or male condom use, were a thesis or with refugees only.

To assess the quality of the included studies, the Mixed-Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al. Citation2018) Sections 1 and 5, and the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research tools (ENTREQ; Tong et al. Citation2012) were chosen for quality assessment as the studies in this review were either qualitative or mixed methods. Quality assessment and data extraction were conducted simultaneously. Quality assessment was utilized to understand the quality of the included research, not to exclude papers. MMAT results showed that all studies included appropriate details to inform the qualitative synthesis, as there were no major concerns regarding the quality of the included research.

The qualitative data was analyzed using a thematic synthesis method, using the ENTREQ statement guidelines to enhance transparency. The findings from the included studies in this review have been pooled, uploaded to the qualitative analysis software NVIVO v12, and thematically analyzed based on CRD (Akers, Aguiar-Ibáñez, and Baba-Akbari Citation2009) guidance, following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) step-by-step guide to develop an overall synthesis of the findings. The findings of the included papers were coded deductively, focusing on findings related to menstrual experiences of people living with homelessness. Once reviewed among the research team, the codes were merged with similar codes and categorized under broad headings. These were further developed into three broad themes.

Quantitative data came from three of the mixed-methods studies: Budhathoki et al. (Citation2018), Boden et al. (Citation2021), and Myers et al. (Citation2018). Due to the limited amount of data, results are presented narratively.

Results

The systematic search identified nine studies conducted in four countries: the United States (n = 5), Canada (n = 1), Nepal (n = 2), and the United Kingdom (n = 1) (see Collectively, 581 participants including key informants are represented. All nine studies included women, only one study included a participant who described themself as intersex and zero studies reported any menstruators who identified as transgender or non-binary. Study designs included interviews, including three semi-structured interviews, two focus groups and three in-depth interviews. A survey and semi-structured questionnaire were used in two studies. One study used an embedded mixed-method quasi-experimental pilot study. Five of the included studies examined the menstrual experiences of people living with homelessness exclusively.

Table 1. Literature review.

The findings were qualitatively synthesized, from which three key main themes were derived: (1) challenges in the logistics of managing menstruation while homeless, (2) feelings of embarrassment, shame, and dignity linked to maintaining menstrual health, and (3) making do: how people experiencing homelessness manage challenges related to menstruation (see ).

Table 2. Coding framework.

Theme 1: challenges in the logistics of managing menstruation while homeless

The challenge of menstruation management is compounded by the limited access to hygienic facilities and products people who menstruate, and experience homelessness are facing. This group also experiences period poverty and may abandon other basic needs to afford to manage their monthly menses.

Lack of/limited facilities and privacy

Finding a clean, private space to participate in MHM was a common issue reflected in the findings (Sommer et al. Citation2020; Vora Citation2020). There were very few options for facilities, all described as unsanitary and/or unfit for purpose. Similarities in experiences can be drawn from those displaced by an earthquake (e.g. Budhathoki et al. Citation2018) who had the same difficulties finding a private and safe place to manage their menstrual health.

Some residents of homeless hostels are being asked to leave during the day, resulting in a reliance on public bathrooms (Gruer et al. Citation2021; Sommer et al. Citation2020). Vora (Citation2020) highlighted the need for private spaces for MHM rather than communal and public facilities. Public use facilities are of limited availability, forcing one woman interviewed in Sommer et al. (Citation2020) to change her tampon in a public outdoor space; “I’ve still multiple times … had to go pee in a corner of the subway and then put a tampon in” (IDI002)”. Customer-only public facilities, e.g. restaurant bathrooms, require the person to spend money to access facilities. Of the 32 respondents in Boden et al. (Citation2021), 29 percent reported that they do not always have access to facilitate the practice of menstrual health, and 44 percent reported that they do not always feel safe changing their menstrual products (Boden et al. Citation2021).

With limited access to facilities to change menstrual products there is an increased necessity for washing and laundry services due to leakages. Free washing and laundry services were of limited availability within the hostels which compelled those menstruating both in hostels and on the streets to frequently dispose of and replenish or go without clothing and underwear rather than washing it (Ensign Citation2000; Sommer et al. Citation2020). Lack of appropriate and safe facilities has led to toilet blockages and general bathroom uncleanliness where residents are forced to dispose of products alternatively (Sommer et al. Citation2020). Tensions arose when residents occupied the limited communal facilities for longer periods to practice MHM (Boden et al. Citation2021; Sommer et al. Citation2020). Further, Boden et al. (Citation2021) also noted women feigning illness in order to access hospital showering facilities and menstrual health products.

Limited access to menstrual health products

The way people obtained menstrual products differed based on living situations, with sheltered people more likely to purchase their own products. Those who were rough sleeping relied on service providers and alternative methods of menstrual health (Gruer et al. Citation2021); see Theme 3.1 on the practice of alternative MHM.

Sometimes services provide menstrual health products; however, included studies noted issues surrounding where this provision falls short in meeting needs (Boden et al. Citation2021; Gruer et al. Citation2021; Sommer et al. Citation2020; Vora Citation2020). Gruer et al. (Citation2021) and Vora (Citation2020) note that people could only access necessary menstrual products sporadically for a limited time. Further, preferences for one product over another (e.g. tampons over pads) could not always be fulfilled. Low-quality products also lacked absorbency, increasing the likelihood of leaks and necessitating changing of products more regularly (Boden et al. Citation2021; Gruer et al. Citation2021). Vora (Citation2020) speaks on environmental consciousness and the rights of those experiencing homelessness to a fully informed decision about the products they use. Reusable products, however, were not preferable to those in the research, namely due to the difficulties in washing them and initial cost. Vora (Citation2020) argues that to give people full autonomy to choose the right product for them, education should be provided alongside the materials.

Myers et al. (Citation2018) highlighted the need to ensure that menstrual health products are culturally appropriate. Culturally appropriate products can differ depending on region; in research by Budhathoki et al. (Citation2018) reusable cloths were offered as this is what they would use at home.

Menstruation is expensive

As discussed in Theme 1.2 when free products are supplied by services, they often do not meet the needs of those using them. Ensign (Citation2000) and Gruer et al. (Citation2021) recognized that menstruating persons experiencing homelessness often choose between one basic need over another. Forgoing food in order to purchase sanitary products was a norm, and it was sometimes necessary to shoplift in order to manage menses (Vora, Citation2020). Gruer et al. (Citation2021) also describes dependence on financial support from friends and family and public assistance funds to purchase menstrual products.

Relevant to menstruation, reproductive health issues may require costly medications and creams which further complicate an already vulnerable financial situation, people often going without and seeking self-treatment alternatives (Ensign, Citation2000) discussed further in Theme 3.

Difficulties in maintaining menstrual health while menstruating

Due to logistical issues related to privacy, limited cleaning facilities, toilets, and sanitary products, menstruating persons find it very difficult to maintain menstrual health. This difficulty can lead to infections (Ensign, Citation2000) and blood-stained clothing, which are challenging and expensive to amend while homeless.

Sommer et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the challenge of passing as someone who is not homeless made it more difficult when unable to maintain menstrual health. Passing as not homeless allowed them to access public and privately owned bathroom facilities to wash and practice menstrual health. Without the ability to pass, they may be turned away due to stigma attached to homelessness.

Theme 2: feelings of embarrassment, shame, and dignity linked to maintaining menstrual health

Limited ability to maintain menstrual health and deal with stained clothing and stigma results in feelings of embarrassment and shame. The concept of menstrual shame and the stigma attached to homeless female-presenting people were explored in depth by Sommer et al. (Citation2020) and Vora (Citation2020). Vora (Citation2020) describes people experiencing homelessness as being further marginalized and stigmatized by their menstruation “abject fluid comes to plague the abject body” Vora (Citation2020, 34). Leakages and stained clothing due to lack of supplies or access to facilities compounded their actual and felt isolation (Sommer et al. Citation2020). Even as a paying customer in commercial environment, women were subject to stigma around assumed drug use, which limited their access to bathrooms when staff gatekeep facilities (Sommer et al. Citation2020).

Under the the current provision of menstrual products in services, the delivery of such products by male staff can further strip women of their dignity and force disclosure of menstruating status (Gruer et al. Citation2021; Sommer et al. Citation2020). Vora (Citation2020) described the issues around perceptions of accommodation staff as akin to prison wardens made clients reluctant to speak about intimate needs such as menstrual health. As one participant in the study by Gruer et al. (Citation2021) describes;

…the humiliation is that you have to keep going back to them and asking them, and when you’re asking for, because they have police and security, so it’s not private. So you’re asking for it in front of NYPD and DHS security, and most of those are male staff. —IDI 07. (Gruer et al. Citation2021, 4)

Participants in research by Gruer et al. (Citation2021) also spoke of the rationing of free menstrual supplies to a few pads or tampons at once, forcing people to have to ask multiple times per day. Others said the embarrassment of disclosing menstrual status prevented them from obtaining the free products altogether. Embarrassment and shame were intensely experienced during these interactions, described as “putting aside one’s pride” (Boden et al. Citation2021). Anxiety and discomfort were also reported, participants felt the need to hide that they were menstruating and felt judged by others when they could not maintain their menstrual health, perpetuating this vicious cycle. As a shelter staff highlights:

… the women have to go and ask for menstrual products, and then you have the male staff smiling, smirking at them … Women feel that they’re being discriminated against, harassed, sexually harassed because they’re menstruating—IDI 07. (Gruer et al. Citation2021, 5)

Theme three: making do: how people experiencing homelessness manage challenges related to menstruation

When people experiencing homelessness are menstruating, their limited access to facilities and products forces them to experiment with creating solutions for containing blood and treating infection. These solutions may be unsafe, and people may sacrifice other basic needs.

Being creative with alternative solutions

Several of the included papers present accounts of women making do and having to be creative with menstrual health because they were unable to access or afford products like tampons and pads. For example, several women reported using sponges, clothes and cut-up t-shirts as reusable methods to soak up menstrual blood and avoid leaking through to their clothes (Budhathoki et al. Citation2018; Ensign Citation2000; Gruer et al. Citation2021; Vora Citation2020). In three papers, women reported using layered up wads of toilet paper (Boden et al. Citation2021; Gruer et al. Citation2021; Vora Citation2020). Boden et al (Citation2021) also indicated that three of twenty-seven respondents had reused a soiled disposable menstrual product.

Due to the severely limited availability and accessibility of toilets and washing facilities, several papers (Boden et al. Citation2021; Ensign, Citation2000; Sommer et al. Citation2020) also discussed alternative ways in which the women washed themselves or accessed showering facilities. For example, when able to access them, some used female towelettes to wash themselves (Ensign, Citation2000). Due to the extreme challenges in maintaining good MHM whilst homeless (Boden et al. Citation2021), discussed an increase in vaginal infections. Ointments to treat these infections are often expensive and therefore women turned to cheap and easily accessed/made herbal remedies (Ensign, Citation2000).

Last resorts: sacrifices to access the resources needed to manage menstruation

As a result of their lack of resources, people menstruating while homeless may be forced to make major sacrifices in order to manage their menses. Boden et al. (Citation2021) noted women were forced to weigh up the costs and benefits of prioritizing menstrual health products over other occupations such as bus fares or leisure. When women needed menstrual health products and could not access or afford them, some of the papers reported women resorting to stealing these products, termed “survival shoplifting” p. 38 by Vora (Citation2020). In addition, women sacrificed other basic needs in order to buy sanitary products including foregoing food.

What services do women living with homelessness find useful?

Research by Aparicio et al. (Citation2019) specifically focused on evaluating a particular service in Hawaii providing reproductive health services. Women noted the provision of menstrual health products and birth control products was particularly useful. Sexual health services were unanimously appreciated, specifically one-on-one sexual health sessions.

In terms of the built environment, visiting public spaces such as cafes and day centers for warmth and comfort whilst menstruating helps soothe pain and discomfort (Vora Citation2020). These spaces become particularly useful when shelters are closed during the day (see Theme 1.1).

Within their thematic analysis, Boden et al. (Citation2021) dedicated a theme to the facilitators thought to increase MHM performance. These material and contextual resources included shared information within the community about available support for MHM, knowledge of showering facilities and the sharing of menstrual health products. Of particular importance was the element of peer social support that existed in the community, although the reliance on information solely from these sources was a cause for potential misinformation (Boden et al. Citation2021).

Discussion

Three key themes were derived from this thematic synthesis exploring the menstrual experiences of managing menstruation while homeless. These findings highlight the many logistical challenges involved in managing menstruation while experiencing homelessness, including limited privacy, bathroom facilities, and access to appropriate period products. This often-led women living with homelessness to abandon other basic needs in favor of managing menstruation. The evidence suggests that menstrual support for those experiencing homelessness is sub-optimal. In cases where there is free provision of period products from shelters, these items are sporadically available and often of poor quality (requiring more). Women often resorted to drastic measures that left them at risk of harm such as stealing, putting them at further risk of increasing vulnerability and maintaining homelessness.

The findings of this review are in keeping with evidence that MHM is considerably challenging for people living in low-income settings (Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013). The association between poor menstrual health and increased rates of infections (Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013) highlights one aspect of the global disproportionate health consequences that women living in poverty experience, in this case associated with limited access to appropriate menstrual health products. These findings support the calls of a recent Lancet commission to address gender inequalities in health (Heise et al. Citation2019). The donation-based approach to providing menstrual health products for those experiencing homelessness has been critiqued (Vora Citation2020). This is partly due to access being limited due to feelings of shame and embarrassment associated with asking for appropriate products. Our findings highlight the need to stop gatekeeping and limiting these products. There is also a significant need for private, safe, and clean locations for managing menstruation and access to laundry facilities. Reframing the term MHM, from hygiene to health management highlights the importance of this as both a public health and human rights issue. Doing so might elicit the changes that are so desperately needed.

This qualitative evidence synthesis is the first to synthesize menstrual experiences of people living with homelessness. Previous reviews have investigated period poverty among low-income menstruating adults, college students, or incarcerated individuals. While these reviews continue to be fundamental to enhance education on menstrual health management, this review attempts to specifically highlight and understand menstrual health among people experiencing homelessness. Results were limited to cisgender women, excluding nonbinary and transgender populations. While there is very limited research that examines individuals experiencing homelessness who menstruate but do not present themselves as female, Chrisler et al. (Citation2016) suggests that transgender individuals experience additional challenges surrounding menstruation. Similarly, the intersection of other marginalized identities was not explored during this study, yet race, disability, and neurodivergence may have additional implications for managing menstruation while homeless. Methods of qualitative synthesis have been criticized due to the removal of context from the primary source, as well as bias due to researchers’ subjective interpretation of the data. However, multiple reviewers followed the standardized guidance for conducting systematic reviews to ensure rigorous and transparent methods to minimize bias in the results.

The findings from this review of the qualitative literature highlight a gap in research and understanding about the experiences of menstruation whilst homeless. The majority of studies identified from our search focused on sexual health (STIs and contraception) and pregnancy whilst living with homelessness. In fact, four of the included in this review also primarily focused on sexual health (Aparicio et al. Citation2019; Ensign, Citation2000; Haldenby et al., Citation2007; Myers et al. Citation2018). The literature on sexual health and homelessness is vast, with minimal focus on menstruation despite the clear difficulties related to MHM. In comparison, and despite the challenges reported by women in this review, menstruation has been neglected in research. Future research focusing on the experiences of menstruation whilst experiencing homelessness is needed to better understand how to improve provisions. Studies should explore the experiences of all people who menstruate, including members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

The findings have implications for policy, highlighting the need for free, readily available, good quality, culturally appropriate menstrual health products for those experiencing poverty and homelessness. Crucially, these products must be easily accessible, without the need for a gatekeeper to distribute them.

These findings highlight the need for a call to action for commissioners and policymakers to address the sub-optimal provision of MHM resources in homeless services as a fundamental right alongside other health provisions. There needs to be a move away from the current donation-based approach which focuses on giving women choice and culturally appropriate products. This new approach should end MHM product gatekeeping and limit access to menstrual products, washing, and bathroom facilities in services. Further research is also needed to understand how we can better serve people who may experience both homelessness and mensuration differently, e.g. LGBTQIA+/gender-queer people, younger adults/children, marginalized groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank those who have helped in the completion of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akers, J., R. Aguiar-Ibáñez, and A. Baba-Akbari. 2009. “Systematic Reviews: Crd’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care.” Centre for Reviews and Dissemination University of York. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/SystematicReviews.pdf.

- Aparicio, E. M., O. N. Kachingwe, D. R. Phillips, J. Fleishman, J. Novick, T. Okimoto, M. K. Cabral, et al. 2019. “Holistic, Trauma-Informed Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention and Sexual Health Promotion for Female Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Initial Outcomes of Wahine Talk.” Children and Youth Services Review 107:104509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104509.

- Boden, L., A. Wolski, A. S. Rubin, L. Pfaltzgraff Oliveira, and Q. P. Tyminski. 2021. “Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators to Menstrual Hygiene Management for Women Experiencing Homelessness.” Journal of Occupational Science 30 (2): 235–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2021.1944897.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Budhathoki, S. S., M. Bhattachan, E. Castro-Sánchez, R. Agrawal Sagtani, R. Bikram Rayamajhi, P. Rai, and G. Sharma. 2018. “Menstrual Hygiene Management Among Women and Adolescent Girls in the Aftermath of the Earthquake in Nepal.” BMC Women’s Health 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0527-y.

- Chrisler, J. C., J. A. Gorman, J. Manion, M. Murgo, A. Barney, A. Adams-Clark, J. R. Newton, and M. McGrath. 2016. “Queer Periods: Attitudes Toward and Experiences with Menstruation in the Masculine of Centre and Transgender Community.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (11): 1238–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1182645.

- Clark, R. E., L. Weinreb, J. M. Flahive, and R. W. Seifert. 2019. “Homelessness Contributes to Pregnancy Complications.” Health Affairs 38 (1): 139–46. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05156.

- Duke, A., and A. Searby. 2019. “Mental Ill Health in Homeless Women: A Review.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 40 (7): 605–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1565875.

- Ensign, J. 2000. “Reproductive Health of Homeless Adolescent Women in Seattle, Washington, USA.” Women & Health 31 (2–3): 133–51. https://doi.org/10.1300/j013v31n02_07.

- Gruer, C., K. Hopper, R. Clark Smith, E. Kelly, A. Maroko, and M. Sommer. 2021. “Seeking Menstrual Products: A Qualitative Exploration of the Unmet Menstrual Needs of Individuals Experiencing Homelessness in New York City.” Reproductive Health 18 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01133-8.

- Guillén, A. I., S. Panadero, and J. Juan Vázquez. 2021. “Disability, Health, and Quality of Life Among Homeless Women: A Follow-Up Study.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 91 (4): 569–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000559.

- Haldenby, A. M., H. Berman, and C. Forchuk. 2007. “Homelessness and Health in Adolescents.” Qualitative Health Research 17 (9): 1232–44. doi:10.1177/1049732307307550.

- Heise, L., M. E. Greene, N. Opper, M. Stavropoulou, C. Harper, M. Nascimento, D. Zewdie, et al. 2019. “Gender Inequality and Restrictive Gender Norms: Framing the Challenges to Health.” The Lancet 393 (10189): 2440–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30652-x.

- Hong, Q. N., S. Fàbregues, G. Bartlett, F. Boardman, M. Cargo, P. Dagenais, and P. Pluye. 2018. “The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers.” Education for Information 34 (4): 285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221.

- Kuhlmann, S. A., E. P. Bergquist, D. Danjoint, and L. Lewis Wall. 2019. “Unmet Menstrual Hygiene Needs among Low-Income Women.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 133 (2): 238–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000003060.

- Moffa, M., R. Cronk, D. Fejfar, S. Dancausse, L. Acosta Padilla, and J. Bartram. 2019. “A Systematic Scoping Review of Environmental Health Conditions and Hygiene Behaviors in Homeless Shelters.” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 222 (3): 335–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.12.004.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and PRISMA Group*, T. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” Annals of Internal Medicine 151 (4): 264–9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

- Myers, A., S. Sami, M. Adhiambo Onyango, H. Karki, R. Anggraini, and S. Krause. 2018. “Facilitators and Barriers in Implementing the Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health in Nepal Post-Earthquake.” Conflict and Health 12 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0170-0.

- Ouzzani, M., H. Hammady, Z. Fedorowicz, and A. Elmagarmid. 2016. “Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews.” Systematic Review 5 (1): 1–0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. pmid:26729230.

- Royal College of Nursing. 2021. Debate: Period Poverty. https://www.rcn.org.uk/congress/congress-events/11-period-poverty.

- Sharma, S., D. Mehra, N. Brusselaers, and S. Mehra. 2020. “Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-And Policy-Level Actions.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (2): 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020647.

- Sommer, M., C. Gruer, R. Clark Smith, A. Maroko, and K. Hopper. 2020. “Menstruation and Homelessness: Challenges Faced Living in Shelters and on the Street in New York City.” Health & Place 66:102431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102431.

- Sumpter, C., and B. Torondel. 2013. “A Systematic Review of the Health and Social Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management.” PLoS One 8 (4): e62004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062004.

- Thomson, J., F. Amery, M. Channon, and M. Puri. 2019. “What’s missing in MHM? Moving beyond hygiene in menstrual hygiene management.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27 (1): 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1684231.

- Tong, A., K. Flemming, E. McInnes, S. Oliver, and J. Craig. 2012. “Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: ENTREQ.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 12 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

- Vora, S. 2020. “The Realities of Period Poverty: How Homelessness Shapes Women’s Lived Experiences of Menstruation.” The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_4.

- Vuillermoz, C., S. Vandentorren, R. Brondeel, P. Chauvin, and W. Nishimura. 2017. “Unmet Healthcare Needs in Homeless Women with Children in the Greater Paris Area in France.” PLoS One 12 (9): e0184138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184138.

- World Heath Organization. 2022. “WHO Statement on Menstrual Health and Rights. In 50th Session of the Human Rights Council Panel Discussion on Menstrual Hygiene Management, Human Rights and Gender Equality .” https://www.who.int/news/item/22-06-2022-who-statement-on-menstrual-health-and-rights.