Abstract

Sickle cell disease affects more than 30 million people worldwide, including 0.1% of the population in Lebanon. It is characterized by unpredictable and painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) that may lead to serious complications. This study describes the clinical burden of sickle cell disease in a cohort of patients treated at a comprehensive sickle cell disease referral center in Tripoli, Northern Lebanon. Patient demographics, clinical events, treatment, and survival were evaluated from a local, hospital-based registry of 334 sickle cell disease patients treated at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon, between 2009 and 2019. Mean age at sickle cell disease diagnosis and at first clinic visit was 2.9 and 8.5 years, respectively. Pain was the most common clinical event observed among all patients. Over the 10-year follow-up period, 15 (4.5%) patients died. Hydroxyurea (HU) and red blood cell (RBC) transfusions were the most commonly used therapies. One hundred and thirty-one (39.0%) patients were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital; the remaining patients were referred to and subsequently followed-up at the Nini Hospital. Eighty-seven (66.0%) Nini Hospital-diagnosed patients experienced a VOC. Seventy-four (85.0%) of these patients with a VOC event required HU during follow-up. Patients with a VOC required more RBC transfusions, cholecystectomy, and splenectomy than non-VOC patients. The high disease burden observed in this population of sickle cell disease patients illustrates a continued, unmet need to both prevent and manage VOC events and other sickle cell disease-associated complications.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease, a multi-system disorder caused by a single gene mutation, is characterized by hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusion, endothelial dysfunction, organ failure, and significant lifetime morbidity and early mortality [Citation1,Citation2]. Sickle cell disease is a disorder of global importance with both economic and clinical significance [Citation1]. Many children with sickle cell disease, specifically those born in underdeveloped countries, die undiagnosed or in early childhood from sepsis and/or acute splenic sequestration (ASS) due to a lack of access to medical care [Citation3]. Others may die later from disease complications, including stroke, acute chest syndrome (ACS), and end-organ failure or from the consequences of under-recognized chronic iron overload resulting from blood transfusions [Citation4]. Recurrent episodes of vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC), the clinical hallmark of sickle cell disease, are unpredictable and extremely painful events that can lead to serious acute and chronic complications and repeated inpatient hospitalization [Citation5–8].

Sickle cell disease affects more than 30 million people worldwide, predominantly in populations in sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Middle East [Citation9–11]. In 2016, the annual rates of neonates born with sickle cell disease were estimated at 230,000 in the African region, 43,000 in the Southeast Asian region, 13,000 in the region of the Americas, 10,000 in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 3500 in the European region and four in the Western Pacific [Citation12]. In many African countries, 10.0‐40.0% of the population carries the sickle cell gene [Citation13]. In the United States, 80,000‐100,000 individuals are affected by the disease [Citation14]. In Lebanon, the incidence of sickle cell disease is estimated at 0.1% (1/1000), with geographic clustering of the highest disease prevalence in Northern Lebanon [Citation9].

Symptomatic management and prevention of VOCs using the Hb F-reactivating agent hydroxyurea (HU) is currently the mainstay of treatment [Citation15]. In 2017, pharmaceutical-grade L-glutamine, an oral medication, was approved in the United States to reduce acute complications in children aged >5 years and adults with sickle cell disease. Subsequently, in late 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved two additional drugs for the treatment of sickle cell disease: crizanlizumab for reducing the frequency of VOCs in adults and pediatric patients aged 16 years and older, and voxelotor for the treatment of sickle cell disease in adults and pediatric patients 12 years of age and older. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative option in individuals with sickle cell disease. Due to its risks, HSCT with closely matched donors is reserved for patients with the most severe disease [Citation13].

Treatment of sickle cell disease is associated with a sizable economic burden and there is an immediate need to develop treatment options to help sickle cell disease patients achieve more pain-free days and fewer crisis events [Citation13,Citation16]. One study conducted in the United States estimated the total cost of medical care for an average sickle cell disease patient reaching age 45 years to be almost US$1 million [Citation16]. In lower-income countries, access to comprehensive disease management for sickle cell disease may be limited due to the expense and poor healthcare infrastructure [Citation2].

Few studies examining the characteristics and outcomes of sickle cell disease patients in lower-income countries exist. The primary objective of this observational, real-world study was to understand the clinical burden of sickle cell disease in a lower-income country by documenting the characteristics, complications, treatments, and survival of a cohort of patients treated at a comprehensive sickle cell disease referral center in Northern Lebanon.

Methods

Study design and data source

Patient demographic and clinical data were extracted from electronic health records and non-electronic medical files to create a registry of sickle cell disease patients treated at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon. Missing information was retrieved from patients and their parents via telephone calls. Nini Hospital is a private, acute-care, 122-bed hospital located in Tripoli, Lebanon. This medical facility has a well-resourced, specialized sickle cell disease health service linked to a surrounding community-based care network and fully supported by a nongovernmental organization. Available data included patient demographics, hematological, genetic, and imaging data, clinic and emergency department visits, hospitalizations, clinical events, death, relevant clinical assessments, and treatment interventions (e.g. HU, transfusions, surgery, and other medications). Institutional management guidelines recommended patient health maintenance visits ranging from every 2 months to annually and as needed, depending on patients’ age and disease severity.

Study population

The study sample included pediatric and adult (up to 64 years old) sickle cell disease patients who were managed at the Nini Hospital from 2009 to 2019; this included patients who were diagnosed at the hospital or who were referred from outside the hospital network but were subsequently followed-up at the Nini Hospital. Patients were considered to have been diagnosed at the Nini Hospital if there was a gap of 60 days or less between the date of sickle cell disease diagnosis and a subsequent visit within the Nini network.

Study measures

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics included age at first visit, age at sickle cell disease diagnosis, Hb level at diagnosis, Hb F level at diagnosis among patients aged >2 years, Hb S (HBB: c.20A>T) level at diagnosis, sickle cell disease genotype, and gender. Sickle cell disease genotypes were defined as homozygous Hb S (βS/βS), Hb S/β0-thalassemia (Hb S/β0-thal), Hb S/β+-thal, Hb S/Hb D-Punjab (HBB: c.364G>C), Hb S/Hb C (HBB: c.19G>A), and Hb S/Hb O-Arab (HBB: c.364G>A). Treatments included HU, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions, iron chelation therapy, bone marrow transplant (BMT), folic acid, cholecystectomy, and cholecystectomy/splenectomy. Clinical events consisted of pain, ACS, ASS, dactylitis, joint necrosis, priapism, pulmonary hypertension (PH), sepsis, osteomyelitis, stroke, leg ulcers, hospitalizations, and death. Vaso-occlusive crisis events, defined as the composite of pain and/or ACS, were recorded if they resulted in inpatient hospitalization and were assessed only among the subset of patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital; they were not documented among referred patients because of concerns about reporting memory-dependent and potentially inaccurate data.

Statistical analyses

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous, quantitative variable summaries included the number of patients, mean, and range. Categorical, qualitative variable summaries included the frequency and percentage of patients in a specific category.

The proportion of patients receiving each therapy was described. The proportion of patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital with one or more VOC events, descriptive statistics of the number of VOC events per patient, other associated clinical events and proportion of patients requiring hospitalization at the time of each clinical event were summarized.

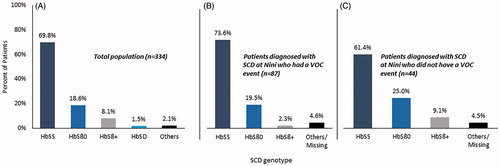

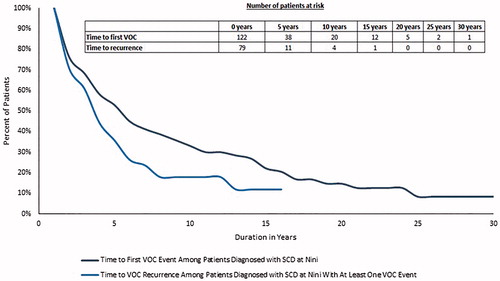

Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate two time-to-event outcomes among patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital: (i) time to first VOC event, and (ii) time from first VOC event to a second VOC event. In both analyses, patients who did not have a VOC episode were censored on their last visit date with the Nini network. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was assessed only among patients for whom the last visit date was documented, in order to appropriately censor patients. Mean cumulative count (MCC) estimation was used to estimate the average number of VOC events per patient diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the hospital over time. The MCC has been shown to accurately capture the burden of recurrent events in a population within a given time, summarizing all the events that occur in an at-risk population [Citation17].

Results

Characteristics of all patients

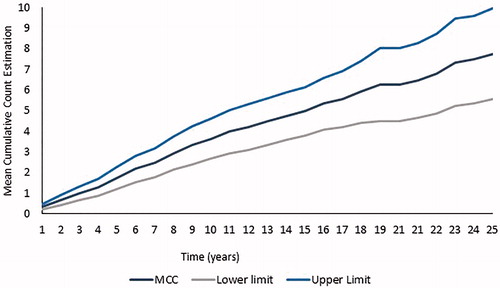

From 2009 to 2019, 334 sickle cell disease patients were treated at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon (); 52.7% of patients were male and 47.3% of patients were female. Mean age at sickle cell disease diagnosis and at first clinic visit was 2.9 years (range: 0-31) and 8.5 years (range: 0‐43), respectively. Most patients (73.4%) were aged 0‐3 years at diagnosis (). The mean number of years between sickle cell disease diagnosis and latest clinic visit date was 13.8 years (range: 0‐48.6). The mean Hb and Hb F levels (among patients aged >2 years) at diagnosis were 7.8 g/dL (range: 1.8‐14.6) and 18.2% (range: 0.5‐40.7), respectively (). The most common genotypes were homozygous Hb S (233 [69.8%]), Hb S/β0-thal (62 [18.6%]), and Hb S/β+-thal (27 [8.1%]) [. Pain (84.4%), ACS (40.4%), ASS (34.4%), and dactylitis (27.2%) were the four most common clinical events observed among all patients. Rates for other clinical events were low ().

Figure 1. Sickle cell disease genotypes in (A) the total population, (B) the subset of patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital with a VOC event, and (C) the subset of patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital without a VOC event. HbSS: homozygous Hb S; HbSβ0: Hb S/β0-thal; HbSβ+: Hb S/β+-thal: HbSD: Hb S/Hb D-Punjab; SCD: sickle cell disease; VOC: vaso-occlusive crisis.

Table 1. Characteristics of all patients.

Table 2. Clinical events during follow-up among all patients.

Treatment

Of the patients for whom HU utilization data were available (n=324), 236 (72.8%) received HU. Red blood cell transfusions were given to 280 (83.8%) patients and mostly in an episodic pattern for acute events and major surgical procedures. Only 37 (11.1%) patients received iron chelation therapy. Three patients (0.9%) underwent BMT and were cured (). All patients were treated with folic acid. Penicillin prophylaxis was also given to children until 5 years of age and to post-splenectomy patients.

Table 3. Treatment choices among all patients.

Survival

Fifteen (4.5%) patients died (), 11 of whom had homozygous Hb S, and two of whom had Hb S/β0-thal. All deaths except one were in patients older than 10 years of age. The two most common causes of death were stroke and multi-organ failure.

Characteristics of patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital

In the 131 patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital [, 66.4% had a VOC event that led to hospitalization () and these patients were more likely to be male () and of homozygous Hb S genotype [. Clinical events were comparable with those seen in the overall group (). Seventy-four (85.1%) patients with a VOC event required HU during follow-up (). Patients with a VOC event had a higher percentage of RBC transfusions, cholecystectomy, and splenectomy than the non-VOC group ().

Table 4. Characteristics of patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon.

Table 5. Clinical events during follow-up among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon.

Table 6. Treatment choices among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital, Tripoli, Lebanon.

Kaplan-Meier analysis and mean cumulative count estimation among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital

Overall, the median time from sickle cell disease diagnosis to the first VOC event was 4.4 years and the median time from the first VOC event to a subsequent VOC event was 2.7 years (). A linear trend of the average number of VOC events per patient diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the hospital was observed over time, and at 10 years after sickle cell disease diagnosis, patients are estimated to have an average of four VOC events ().

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier analysis. Time to first VOC event among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital and time to VOC recurrence among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital with at least one VOC event. SCD: sickle cell disease; VOC: vaso-occlusive crisis.

Discussion

This is the first study examining the burden experienced by a cohort of sickle cell disease patients specific to Northern Lebanon. Eighty-seven (66.0%) patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital had a VOC event that led to hospitalization, and patients in the VOC group had a higher percentage of RBC transfusions (89.7 vs. 61.4%), cholecystectomy (24.1 vs. 9.1%), and splenectomy (29.9 vs. 15.9%) than the non-VOC group. The majority of patients (85.1%, n=74) with a VOC used HU as a maintenance treatment. Despite being the only drug available for prevention of VOCs at time of study and having an oral formulation, adherence to HU treatment is broadly noted as a challenge among pediatric populations [Citation18,Citation19].

Rates of clinical events in this study are higher than those observed in past studies examining the Lebanese sickle cell disease population. In a 2007 study examining the Lebanese sickle cell disease population, pain, ACS, dactylitis, ASS, and joint necrosis were observed in 31.7, 14.6, 17.8, 19.7 and 11.8% of patients, respectively [Citation10]. In this study, these rates were 84.4, 40.4, 27.2, 34.4 and 16.2%, respectively. This may be attributed to the strict Nini management guidelines, which recommend patient health maintenance visits every 2 months to annually and as needed, depending on patients’ age and disease severity. With this close follow-up, it is expected that clinical events are captured more frequently and accurately than in the Inati et al. [Citation10] study where patients were followed in three centers and were not seen on a similarly strict regular basis as those in the current cohort. Another possible reason could be a difference in genetic sickle cell disease modifiers in the Northern Lebanese cohort compared with the overall Lebanese one.

Hb F has been shown to be a major modulator of disease severity in sickle cell disease, with a high Hb F level reported to ameliorate some sickle cell disease complications [Citation20,Citation21]. In this study, a higher Hb F at diagnosis (in those patients aged >2 years) was found in patients with VOC compared to those without a VOC (21.3% [range: 0.6-38.9] vs. 14.2% [range: 0.5‐28.5]). Similarly, Hb F ≥20.0% at diagnosis in patients aged >2 years was seen more in patients with VOC compared to those without VOC (60.0 vs. 22.2%). This finding is not particularly surprising as disease severity was assessed only by VOC frequency in this study. Other disease-modifying factors include the coinheritance of α-thalassemia and the β-globin gene cluster haplotypes [Citation22], neither of which were assessed in this study. The βS haplotypes among Lebanese patients with sickle cell disease have, however, been previously reported [Citation23]; most haplotypes are of African origin (90.0%), with the Benin haplotype being the most prevalent (60.0%), while only 10.0% are of Indian-Arab origin. When patients were divided into three groups according to their Hb F levels (<5.0, 5.0‐15.0, and >15.0%), surprisingly, the most severe clinical cases were associated with the highest levels of Hb F. These findings suggest that, while Hb F levels are important, they are not the only parameters that affect the severity of sickle cell disease. Also of note, the high levels of Hb F in patients with the Central African Republic haplotypes seemingly did not ameliorate symptom severity, indicating that genetic factors other than haplotypes are the major contributor to elevated Hb F levels in Lebanon [Citation23].

In a retrospective longitudinal analysis of electronic health records in the United States, 79.5% of patients experienced one or more VOC event and 9.0% of patients had one or more ACS event, a slightly higher rate than observed in this study (66.0% of patients experienced a VOC event defined as a composite of pain and/or ACS) [Citation24]. The higher mean age (39.1 years) at the time of analysis in the United States study [Citation24] than that in this study (mean age at first visit = 8.6 years) can explain this difference in VOC rate. It has been shown that as patients with sickle cell disease age, the VOC rate and other disease complications tend to progressively increase. Another study conducted in France [Citation25] following sickle cell disease patients up to the age of 5 years old noted that 42.9% of their cohort experienced a first VOC at 3 years, a lower rate than observed in the 0-3 years age group in this study. The French study defined VOC as pain and dactylitis, rather than a composite of VOC and ACS as in this study. The rate of a first episode of pneumonia/ACS in the French study [Citation25] was rather high (64.8%). Because of the difference in VOC definition, it is not surprising to see a higher overall VOC rate in patients aged 0-5 years in this study (59.5% of the total cohort) than in the French study. RBC transfusion was also the most often used therapeutic intervention by 3 and 5 years among all patients in the analysis by Brousse et al. [Citation25], similar to trends observed in this study.

It should be acknowledged that defining VOC as a composite of pain and/or ACS is different from other studies in which pain and ACS are reported separately. Differences in definitions can make between-study comparisons difficult; however, because pain and ACS are the two most common reasons for hospitalization, often coexist, and together represent the major burden in sickle cell disease, combining these clinical events provides a better estimate of disease burden, which is the primary objective of this study. Additionally, some recently conducted clinical trials have used this description [Citation26,Citation27].

Despite the high disease burden and low community resources in this Northern Lebanese sickle cell disease population, the mortality rate was relatively low, spared the less than 10 years old age group, and was comparable with developed countries. This may be attributed to early diagnosis and introduction of disease-modifying therapy, comprehensive follow-up, and regular parent/patient education about life-threatening disease complications and the importance of seeking urgent medical treatment. The full support by a non-governmental organization is an additional contributing factor to the success of this program.

A state-specific Medicaid claims analysis conducted in the United States estimated the annual cost of sickle cell disease. For an average person with sickle cell disease reaching age 45 years, annual total costs of healthcare ranged from over US$10,000 for children to over US$30,000 for adults, with total lifetime costs estimated to be almost US$1 million [Citation16]. Additional studies will be useful in examining the economic burden of sickle cell disease care in lower-income countries.

The limitations of this analysis include the retrospective nature of its methods and the small sample size due to capturing VOC events only among the subset of patients who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the Nini Hospital, with the objective of ensuring accurately censored data collection. VOC events that did not lead to hospitalization were not captured in this study. The low rate of some sickle cell disease-related clinical events such as stroke, PH, and leg ulcers warrants further investigation via disease-associated markers and genetic determinants.

With this high disease burden observed for sickle cell disease patients in Northern Lebanon, an unmet need exists to prevent and manage VOC events and other sickle cell disease-associated complications. It is hoped that novel, effective therapies will soon further brighten the horizon for this sickle cell disease population.

Author contributions

A. Inati: study concept, data collection, interpretation of results; C. Al Alam: data collection, interpretation; C. El Ojaimi: data collection, interpretation; T. Hamad: data collection; H. Kanakamedala: protocol writing, statistical plan writing, data management and analysis; V. Pilipovic: study concept, analysis and interpretation of results; R. Sabah: study concept, analysis and interpretation of results; all authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

V. Pilipovic and R. Sabah are employed by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland and Beirut, Lebanon). A. Inati reports consultancy for Novartis; honoraria from Novartis, Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), Roche (Basel, Switzerland), and Novo Nordisk (Bagsvaerd, Denmark); membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees for Novartis, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Cyclerion Therapeutics (Cambridge, MA, USA), and Roche; and research funding from Novartis, AstraZeneca (Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK), Global Blood Therapeutics (South San Francisco, CA, USA) and Octapharma AG (Lachen, Switzerland). All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gardner RV. Sickle cell disease: advances in treatment. Ochsner J. 2018;18(4):377–389.

- Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561–1573.

- Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(6):480–487.

- Darbari DS, Kple-Faget P, Kwagyan J, et al. Circumstances of death in adult sickle cell disease patients. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(11):858–863.

- Yale SH, Nagib N, Guthrie T. Approach to the vaso-occlusive crisis in adults with sickle cell disease. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(5):1349–1356, 1363–1364. Erratum: Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(2):220.

- Powars DR. Natural history of sickle cell disease–the first ten years. Semin Hematol. 1975;12(3):267–285.

- Alexander N, Higgs D, Dover G, et al. Are there clinical phenotypes of homozygous sickle cell disease? Br J Haematol. 2004;126(4):606–611.

- Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):94–101.

- Khoriaty E, Halaby R, Berro M, et al. Incidence of sickle cell disease and other hemoglobin variants in 10,095 Lebanese neonates. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105109.

- Inati A, Jradi O, Tarabay H, et al. Sickle cell disease: the Lebanese experience. Int J Lab Haematol. 2007;29(6):399–408.

- McGann PT. Sickle cell anemia: an underappreciated and unaddressed contributor to global childhood mortality. J Pediatr. 2014;165(1):18–22.

- Piel FB. The present and future global burden of the inherited disorders of hemoglobin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(2):327–341.

- American Society of Hematology (ASH): State of Sickle Cell Disease 2016 Report. [pdf] Available from http://www.scdcoalition.org/pdfs/ASH State of Sickle Cell Disease 2016 [accessed June 6 2019].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html [accessed November 11 2019].

- Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel targeted therapies. Blood. 2013;122(24):3892–3898.

- Kauf TL, Coates TD, Huazhi L, et al. The cost of health care for children and adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(6):323–327.

- Dong H, Robison LL, Leisenring WM, et al. Estimating the burden of recurrent events in the presence of competing risks: the method of mean cumulative count. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(7):532–540.

- Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Holl JL, et al. Healthcare utilization and hydroxyurea adherence in youth with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;35(5–6):297–308.

- Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Lai J-S, et al. Adherence to hydroxyurea, health-related quality of life domains, and patients’ perceptions of sickle cell disease and hydroxyurea: a cross-sectional study in adolescents and young adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):136.

- Elion J, Berg PE, Lapouméroulie C, et al. DNA sequence variation in a negative control region 5′ to the beta-globin gene correlates with the phenotypic expression of the beta s mutation. Blood. 1992;79(3):787–792.

- Jeffreys AJ. DNA sequence variants in the G gamma-, A gamma-, delta- and beta-globin genes of man. Cell. 1979;18(1):1–10.

- Kulozik AE, Wainscoat JS, Serjeant GR, et al. Geographical survey of beta S-globin gene haplotypes: evidence for an independent Asian origin of the sickle-cell mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;39(2):239–244.

- Inati A, Taher A, Bou Alawi W, et al. Beta-globin gene cluster haplotypes and Hb F levels are not the only modulators of sickle cell disease in Lebanon. Eur J Haematol. 2003;70(2):79–83.

- Bronté-Hall L, Parkin M, Green C, et al. Real-world clinical burden of sickle cell disease in the US community-practice setting: a single-center experience from the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research [abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(1):5856.

- Brousse V, Arnaud C, Lesprit E, et al. Evaluation of outcomes and quality of care in children with sickle cell disease diagnosed by newborn screening: a real-world nation-wide study in France. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1594.

- Heeney MM, Hoppe CC, Abboud MR, et al. A multinational trial of prasugrel for sickle cell vaso-occlusive events. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):625–635.

- Heeney MM, Abboud MR, Amilon C, et al. Ticagrelor versus placebo for the reduction of vaso-occlusive crises in pediatric sickle cell disease: rationale and design of a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter phase 3 study (HESTIA3). Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;85:105835.