ABSTRACT

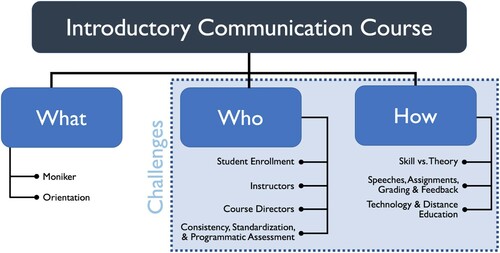

The history of the academic discipline of communication and the subsequent departments that followed are linked in some form or fashion to the evolution of the introductory communication course. Given the prominence and continued relevance of the introductory course in the communication discipline, researchers have conducted surveys for over 60 years. Using a systematic approach, this study synthesizes the cross-sectional findings from 11 basic course surveys (1956–2016). This meta-synthesis approach allowed for the creation of holistic understandings of findings observed across these studies. Specifically, the results centralized around what the course is, and how the greatest challenges in the course relate to who teaches the course and how the course is taught. The results provide insights regarding the introductory course that are intended to inform and stimulate dialogue about an effective and meaningful future for our introductory communication course.

The introductory courseFootnote1 is one of the most enduring pedagogical offerings in the Communication discipline’s undergraduate curriculum (LeFebvre, Citation2017; Sellnow & Martin, Citation2010). Given the relative permanence, the introductory communication course provides a point of entry to explore the discipline and the basic course surveys are ideal historical markers for analysis. Gehrke and Keith (Citation2015) wrote, “As events recede into the past, they become harder to research and recall. But history can do far more than that: it can illuminate the past as well as the present” (p. 2). Basic course surveys provide snapshots of points in communication history that, when pulled together, coalesce and can be focused into a clear picture of the events that define the discipline’s past, which allows those involved to make evidence-based decisions for guiding its future.

The first reference about the introductory communication course was published in The Quarterly Journal of Public Speaking (see Trueblood, Citation1915). That publication advocated the basic course should: (a) focus on public speaking and (b) function as a gateway course for other advanced communication courses. Trueblood’s (Citation1915) publication sparked a flurry of subsequent articles (see Woolbert, Citation1916) that would debate the appropriate goals of oral communication instruction and attempt to define and describe the introductory communication course.

Nearly 40 years later, Hargis (Citation1956) published the earliest survey results of the basic course for the Speech Association of America (now National Communication Association; NCA) Committee on Problems in Undergraduate Study.Footnote2 The Hargis report represented an initial attempt to identify basic course trends and characteristics of the course across the United States (US). Eight years later, Dedmon and Frandsen (Citation1964) published another national survey exploring materials used to teach the course. Another six years would pass before, Gibson, Gruner, Brooks, and Petrie (Citation1970) were charged by the Executive Committee of the Speech Communication Association with the task of again clarifying the course’s nature. Since then, the initial Gibson and colleagues’ basic course survey has been replicated and continues into the twenty-first century. These surveys, published at approximately 5-year intervals from 1970 to 2016, conformed to some degree of methodological (i.e., comprehensive cross-sectional data) similarity. Those studies surveyed samplings of individuals involved with the basic course during given time periods, which highlighted the importance of the course for the discipline. The results of these survey studies have yet to be explored in aggregate.

The purpose of this study is to collectively explore the basic course surveys. Specifically, the goals of this research effort are twofold: (1) integrate the results of the basic course surveys that span 1956–2016 and (2) interpret the results to identify trends and speculate about associated trajectories. This study accomplishes these two goals by using meta-synthesis to comprehensively analyze the findings of the past surveys.

Background to the basic course surveys

Basic course is a moniker used to describe the entry-level, typically first-year communication course. This label—basic course—initially applied by Lindsley (Citation1932) was further popularized in the national survey by Gibson et al. (Citation1970). In the Gibson et al. survey, the authors defined the basic course as:

… that course either required or recommended for a significant number of undergraduates, it is that speech course which the department either has or would recommend as being required for all or most undergraduates if the college administration asked it to name a course so required. (p. 13)

… that course, which provides the fundamental knowledge for all other speech courses. It may be a course which is mainly public speaking, interpersonal, or some other combination of speech communication variables. It teaches the fundamentals of speech communication and is the course which the department has or would recommend as a requirement for all or most undergraduates. (p. 234)

Beyond its title, the influences and impact of the introductory communication course should not be underestimated—over one million undergraduate students across the US enroll in the course yearly (Beebe, Citation2013). Indeed, the course often provides a financial foundation for many communication departments, and it serves as an introduction to the communication discipline (Gehrke, Citation2016a). Beebe (Citation2013) referred to the basic course as the “front porch” (p. 3) to the communication discipline, and suggested the course is where the discipline of communication welcomes others—students, faculty from outside the discipline, and administrators. The course introduces what is taught in communication and why communication disciplinary content and pedagogy are important, if not essential, to a comprehensive higher education experience (Morreale, Valenzano, & Bauer, Citation2017). It could be argued that no other communication course has as much impact or matters more broadly to the communication discipline than the introductory communication course (Gehrke, Citation2016b; NCA, Citation2012).

In sum, the surveys examined in this study provide a 60-year window to explore the evolution of the introductory communication course (and the discipline of communication). These surveys can serve as time-stamp records worthy of closer examination. Moreover, the value of a meta-synthesis across these surveys has the potential to yield meaningful insights about the past and future for the introductory course. Therefore, the present study posits the following research question: What trends emerged across the basic communication course between 1956 and 2016?

Method

Meta-synthesis provides a formalized, complex, and deliberate approach to interpreting an aggregate of findings that arrives at new, comprehensive insights beyond the original research (see Sandelowski, Citation2006). This methodology integrates results from a number of different, yet related descriptive and qualitative studies; however, it does not simply operate to assimilate literature reviews or provide secondary analysis of primary data (Zimmer, Citation2006). A meta-synthesis is an integration that offers more than the sum of the previous studies by generating novel interpretations and providing transformative conclusions beyond singular studies (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007). Meta-syntheses are interpretive and operate as an extension of Glaser and Strauss’ (Citation1967) grounded theory. Using a systematic approach, meta-synthesis enables the ability to generate meaning of these individual studies by considering them in aggregate, creating new holistic understandings of findings observed across studies (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2018; Major, Citation2010; Major & Savin-Baden, Citation2010). This method emerged in response to the proliferation and underuse of qualitative research findings commonly utilized in sociology, public policy, education, and health science fields (see Bondas & Hall, Citation2007; Sandelowski, Citation2006; Thorne, Citation2008). Despite its scarcity in communication scholarship, this method offers the opportunity to add depth to the dimension and interpretation of qualitative and descriptive studies of the introductory communication course (see Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007).

Procedures

Meta-synthesis delineates a set of discrete steps that researchers follow to construct greater meaning through an interpretative process (Erwin, Brotherson, & Summers, Citation2011). In this study, we employed six steps articulated by Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007).

Formulating a clear research problem and question.

Conducting a comprehensive search of relevant literature.

Conducting a careful appraisal of research studies for possible inclusion.

Selecting and conducting meta-synthesis techniques to integrate and analyze qualitative research findings from the included studies.

Presenting a synthesis of findings across the studies.

Reflecting on the process and results.

These steps provide transparency for the process; however, with any qualitative analysis, transparency is not completely possible (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). Next, our application of the six-step procedure is described in order to explicitly showcase our decision-making choices.

For step 1, we formulated a clear research problem and question. We first reflected on the usefulness of past basic course studies and concluded a need to synthesize the past studies to highlight changes over time and discover trends. Based on the identification of that problem, we posed queries to narrow our research question, such as: “Is this research question clear?,” “How, if at all, should the research question be changed?,” “Who is the audience for the results of this study and what will they find useful?” We narrowed and refined the inquiries into a singular research question. We determined our overarching problem would help clarify and explain trends in the basic course for communication educators, scholars, and administrators.

For steps 2 and 3, we first determined inclusion criteria from a comprehensive search and appraisal of relevant literature. The original conception focused exclusively on the nine replicative basic communication course studies that began in 1970 and continued approximately every 5 years through to the most recent replication in 2016. Through collaborative discussion and reviewing these studies, the focus expanded conceptually. The initial study in Citation1970 (Gibson et al.) referenced a 1965 study by Dedmon and Frandsen, which in turn, mentioned a 1956 study on the first course in speech by Hargis. These two articles operated as primary studies about the basic course, which helped to ground and shape the subsequent replicative studies. In summary, 11 studies (N = 11) were included since they each helped illuminate the introductory communication course equally from its inception until the present day; each article was treated equally regarding the relative merit of its content and findings.Footnote3

For step 4, we decided what constituted inclusion as data from the selected studies. We determined that both qualitative and descriptive findings were vital to understanding trends across the studies. Qualitative research is often defined solely by the absence of numbers; however, numbers are integral to this qualitative analysis in that the recognition of patterns in the data and deviations from those patterns would be critical to the generalization of findings (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007). As such, both descriptive statistics and qualitative findings were included in order to generate trends. Additionally, we determined where data had to be located in the studies. We decided to include data primarily derived from the findings in the results; however, we allowed for other data to be considered (e.g., title, discussion, tables, etc.).

We completed a cursory review of all the studies in order to organize the findings. We generated a comprehensive list of survey questions across each study. This process helped develop individual inferential descriptions (i.e., memos) to identify concepts and relationships between and across the studies. We then cross-referenced our memos in an effort to examine, compare, conceptualize, and categorize data through dialogue. We drafted memos for questions to generate dialogue from multiple perspectives and optimize triangulation. In practice, conducting a meta-synthesis resembles processes used in primary descriptive statistics and qualitative research (Major, Citation2010). We compared memos, and then employed a constant targeted comparison (see Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007), or a technique that resembles constant comparison in grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). We completed this iterative process across questions to gradually synthesize them (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2018). Through this process, we rendered judgments about the sameness, difference, confirmation, extension, or refutation of the findings across the basic course studies (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007).

Finally, for steps 5 and 6, we integrated and interpreted patterns and determined findings or trends of interest, which provide systematic insights across the studies of the introductory communication course. We present those findings including preliminary discussion and visual display to aid in understanding the trends.

Verification

To further ensure the validity of these findings, we conducted a modified member check. Member checks asks stakeholders to review results to verify their interpretation and perceived accuracy (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Initially, we identified contact information and sought out prior (living) basic course survey authors to operate as member checks to validate the interpretations for their representative survey contained in the meta-synthesis. Member checkers included the basic course survey authors and one publication editor.Footnote4 These individuals agreed to participate were given instructions to read through our method, results, and preliminary discussion and reflect on their original study and our meta-synthesis. We asked member checkers,

If the findings accurately reflect your study’s findings, based on your recall, information included in your article, and/or information gathered in the process of conducting the study? Are the meta-synthesis’ findings on target with what you reported as an author in the basic course survey?

Results

The findings are presented as four overarching categories that emphasized Content of the Introductory Course, Challenges with the Introductory Course, Instructors of the Introductory Course, and Pedagogy of the Introductory Course (see ). These findings focus on patterns, linkages, and trends across the studies which extended from 1956 to 2016. In these results, the findings reference the surveys by year for readability and clarity.

Content of the introductory course (What)

In order to determine, what the introductory course is, these findings begin by discussing the history of the moniker, and the course orientation. The early surveys (1956, 1965, 1970, and 1974) referred to the basic course as the “first course” in the titles of the articles. However, the term basic course first appeared as part of the basic course surveys after the Executive Committee of the Speech Association of America’s (now NCA) Undergraduate Speech Instruction Interest Group was asked to, “ … determine the nature of the basic course in speech … ” (Gibson et al., Citation1970, p. 1). Later, basic course (Citation1980) appeared in the title of the basic course surveys and has been utilized as part of the survey titles since that time. Despite the preeminence of the term basic course in the surveys and related academic scholarship, most institutions label the introductory communication course in the discipline as public speaking.

The preponderance of evidence suggests that public speaking was and continues to be the predominant orientation of the introductory course. On average, the majority of respondents surveyed throughout the years identified public speaking as the foremost communication course offered to undergraduate students. The 1956 survey reported 59 different titles for the introductory course. However, the majority (51%) either emphasized the “fundamental of speech” or “public speaking.” Of those, the majority of headings (44.6%) emphasized speech, public speaking, voice, fundamentals, oral communication, communications, oral interpretation, and communication of technical information. Some studies fragmented terms that restricted how public speaking, as an orientation of the basic course, was identified. To illustrate, early surveys (1956, 1965, and 1974) splintered terms, such as “fundamentals of speech” and “public speaking” that appear to represent the same course orientation. The open-ended responses in the earlier surveys assessed and observed greater variation in the course title and orientation.

In 1974, only four orientations were possible: public speaking, fundamentals, communication, and multiple. For instance, the Gibson et al.’s (Citation1974) survey reported public speaking as the third most prominent orientation of the basic course, the only study reporting that finding in the history of the surveys. However, that survey used the term “communication” and “public speaking” almost synonymously, which reinforces the finding of a majority course orientation focused on public speaking (if those percentages are added together). In 1980, the fundamentals and multiple orientations were dropped and combination was introduced. The 1990 survey encapsulated the hybrid or blended into the combination orientation. Given the change in course orientation due to the survey’s use of closed questions, the other orientations “pale by comparison to public speaking and the hybrid approach[es]” (Morreale et al., Citation1999, p. 9). In 2006, orientation categories appeared to be further collapsed to: public speaking, hybrid (interpersonal, group, and public speaking), interpersonal group, fundamentals, and other (including theory). The most recent surveys (2010 and 2016) limited orientations to only three options: public speaking, hybrid (covers interpersonal, group, and public speaking), or other. In 2010, the other orientation referred to any introductory course other than public speaking or hybrid, and did not delineating any specification in these responses.

Overall, findings indicated the hybrid orientation as another stable, yet less utilized orientation (see ). Percentages denoted by participants for across survey responses suggested a fluctuation of the hybrid orientation. However, variation in open-ended responses appeared to represent other forms of hybrid basic courses.Footnote5 In 1980, Gibson and colleagues reported a shift from multiple to the public speaking approach; however, percentages across surveys did not evidence this trend. When averaged across surveys, orientation represented 50% public speaking and 30% hybrid. Survey findings signified that public speaking and hybrid orientations maintained similar percentages since conception of the basic course, and public speaking as the prominent orientation throughout the years.

Table 1. Introductory communication course orientation.

Challenges of the introductory course

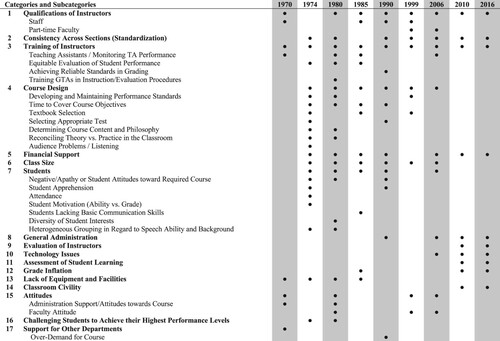

Another commonality across these surveys was an attempt to identify the problems and challenges associated with the introductory course. While the earliest surveys (1956 and 1965) had no questions about problems, all subsequent surveys attempted to identify the greatest challenges confronting the course. Clearly, the challenges identified in the surveys from 1970 to 2016 did not exist in a vacuum; rather, they evolved over time and appeared repeatedly across the surveys. Initially, respondents were asked to identify challenges (e.g., problems, concerns, or issues) without any limitations in open-ended questions. These surveys prompted numerous responses and variability among respondents. Then the most recent surveys (2010 and 2016) provided closed-ended responses from a pre-existing list, thereby limiting responses from respondents.

presents the challenges associated with the introductory communication course as identified by respondents. The most frequently identified challenges across the surveys (according to frequencies averaged across surveys) are rank ordered from most to least frequently mentioned from top to bottom. The survey years, or columns represent whether a challenge was reported within that survey year. Categories are marked with bullets, if either the category or its subcategories were represented in respondents’ responses. The top three greatest challenge categories are Qualifications of Instructors, Consistency Across Sections (Standardization), and Training of Instructors. These categories represent the highest frequencies averaged across surveys (rows) and were commonly reported in multiple surveys (columns). Notably, the challenges are largely tethered to who is teaching the course and entangled in how the course is being taught.

Instructors of the introductory course (Who)

Teaching cannot occur without students. Enrollment trends (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, and 2016), number of course sections (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016), and student course section enrollments (1956, 1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2010, and 2016) mushroomed in the late 1990s. Despite this growth, enrollment trends reported across the surveys were unclear due to (a) not having consistently asked in every study about student enrollment and (b) variability in how respondents were asked to report student enrollment.Footnote6 Regardless, survey data suggest stable or increasing numbers of undergraduate students enrolled in the basic course over time. The majority of respondents reported that course section offerings increased beyond 20 sections per semester (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Student course section enrollment increased capacity with an original ceiling of 22 (1970 and 1974) to 30 (1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999) and then back to 26 (2010 and 2016). Given the increase in course sections and course section enrollment, class size was often reported as a challenge (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, and 2006) but was not reported as such in the two most recent surveys (2010 and 2016).

These dramatic upticks in course sections and student course section enrollment correlated with a shift in the late 1970s and early 1980s to include oral communication in general education programs (see Ford & Wolvin, Citation1993; Sellnow & Martin, Citation2010). These findings indicated that enrollment has either held steady or increased. The vast majority of surveys suggested no decline in enrollment. These implications highlight that enrollment numbers oscillated between stable and increasing levels for the course across surveys. Over time, the inclusion of the basic course in general education curricula increased student enrollment, number of course sections, and student course section enrollment. The increase of students associated with the basic course had direct causal ramifications for instruction in the course.

Instruction

Two of the earliest surveys (1970 and 1974) indicated that the basic course was largely taught by associate and full-time faculty. Then during the 1980s and 1990s, responsibility gradually began to shift to junior faculty and graduate teaching assistants (1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999). Assistant, associate, and full-time faculty provided the majority of instruction (1999, nearly 58%) for the basic course. The largest switch in basic course instruction was when graduate teaching assistants (2006, 71.5%) and part-time faculty (2006, 29.5%) accounted for all the instruction reported in the basic course survey. This trend toward lower rank instructors—part-time faculty and graduate teaching assistants—teaching the vast majority of basic course instruction has been reported in both subsequent surveys (2010 and 2016).

Several reasons may account for the tenure-track faculty in communication departments migrating away from instruction of the basic course. An obvious reason is specialization in the discipline of communication (Stephen, Citation2015). As the discipline evolved, its breadth and depth of scholarly inquiry expanded, which coincided with less senior faculty being involved in teaching the basic (service) course (Handford, Citation1993). Nevertheless, the movement to employ novice teachers to provide most basic course instruction has paralleled what was reported as two of the greatest challenges for the basic course—qualifications of instructors (1970, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016) and training of instructors (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Both these concerns have had a direct impact on coordinating the basic course.

Course coordination

Despite the significant role basic course directors play in the administration and coordination of the basic course, this role has received little attention across the basic course surveys. Only two basic course surveys inquired about basic course directors (2006 and 2010). Both surveys reported that most four-year institutions have a course director (2006, 67%; 2010, 71.6%). However, across each of these surveys, a large discrepancy was reported about the rank of the director overseeing course administration and coordination. The faculty ranks that regularly reported performing the role of basic course director were assistant professors (2006, 41.3%) and then full professors (2010, 23.4%). The majority of respondents (2010, 73.7%) reported that basic course directors did not receive additional compensation.

Minimal qualifications course directors should fulfill in order to coordinate the basic course have been articulated elsewhere (see Weaver, Citation1976). The four qualifications include: (1) a degree in Communication, (2) knowledge of teaching, learning, and assessment, (3) interest in communication education research, and (4) a commitment to the development of effective instructional strategies and methods. These qualifications suggest, as Weaver reasoned, that those overseeing the basic course as directors are educated in the discipline of communication. However, it is unclear from the basic course surveys what the highest degree is for the majority of basic course directors, if these individuals are tenure track, or if their research programs centralize on communication education (or instructional communication). From the data provided across the basic course surveys, there is inadequate support to apply Weaver’s minimal qualifications related to basic course directors. This begs the question about how and whether departments can build consistency and comparability across basic course sections, given the majority of sections taught in the basic course are self-contained (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Moreover, the minority of basic course directors have been responsible for training (1999, 26.7%; 2010, 36.5%), which also could impede the development of course consistency for standardization.

Consistency and standardization

Consistent quality across course sections relates to creating a sense of continuity and comparability (Fassett & Warren, Citation2012). The actualization of course consistency is brought to fruition by basic course personnel managing content. Therefore, the hiring and training of staff is paramount and requires clear communication related to the expectations for maintaining consistency. The basic course surveys (1985, 1990, 1999, 2010, and 2016) reported that the training of instructional staff is highly inconsistent in duration and it is unclear what content is covered during training sessions (i.e., classroom management skills, content coverage, course policies, institutional policies, etc.).

The lack of consistent training was highlighted frequently as a top challenge in the basic course that relates to training of instructors (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016) and evaluation of instructors (2010 and 2016). Due to the variability in survey questions, accurate reporting of preteaching and ongoing training was difficult to decipher. That said preteacher training was the most common practice (1990, 74%) with five days allotted to preteaching sessions (2010). Few surveys reported (1985, 1990, and 1999) if course credit or course work was part of the training process. The subcategories related to teacher training issues included graduate teaching assistants monitoring graduate teaching assistant performance (1970, 1980, 1985, and 2006), equitable evaluation of student performance (1974, 1980, and 1985), achieving reliable standards for grading (1990), and training graduate teaching assistants in evaluation procedures (1980). The desired goals and outcomes of basic course training as well as what should be included in these trainings also were identified as salient issues. Clearly, if part-time faculty and graduate teaching assistants have moved to the forefront of basic course instruction, it becomes more critical to determine how teacher training should be integrated into the basic course to ensure consistency of instruction and content.

The antithetical positioning of consistency and autonomy commonly created tension for basic course teachers. Using a Likert-type scale of great (ranged from 51% to 67%), moderate (ranged from 25% to 34%), and little (ranged from 3% to 19%), a majority of surveys reported teacher autonomy as “great” (1974, 1980, 1985, and 1990). Teacher autonomy appeared to decrease when standardization emerged (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Only once (1999) did teacher autonomy and standardization appear in the same survey as separate survey items. In that survey, respondents’ responses for “great” teacher autonomy fell to 12.8% (38.2% drop from the previous survey). As autonomy fell, the top challenge identified was maintaining consistency in quality, substance, performance, and testing standards, from section to section in multisection courses. Questions focusing on teacher autonomy stopped and inquiries about standardization emerged. The most commonly reported standardized items related to the basic course have included: learning objectives (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016), syllabus (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016), textbook selection (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016), and assignments (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016).

Consistency across sections and standardization (1974, 1980, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016) have been a weighty challenge for the basic course (Fleuriet, Citation1993). The issue of consistency across sections reached an all-time high when it was reported as the most significant challenge (2010, 55.6%). The relationships among consistency and standardization and teacher autonomy appear clear-cut; as standardization increases, teacher autonomy decreases (or disappears). But for standardization and autonomy, it becomes a question of balance: To what degree is it appropriate to maintain consistency and comparability and at the same time allow instructors a sense of autonomy (or empowerment)? The concept of course consistency and teacher autonomy directly relates to how the basic course is taught.

Programmatic assessment

Assessment of the basic communication course is a relatively new arrival to the surveys (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). The method of programmatic assessment of the basic course has transformed throughout its brief reporting history. Initially, student feedback was the most utilized form of assessment (1999, 74.5%). Competency-based assessment followed (2006, 85%) as the preferred form of assessment. However, most respondents reported that their assessment procedures for the basic course did not meet the expectations of those outside the course (2010). In addition, most respondents reported that no formal assessment process had been employed as part of the course (2016). It comes as no surprise that during this same timeframe one of the greatest challenges associated with the basic course was assessment of student learning (2010 and 2016).

Pedagogy of the introductory course (how)

Since the basic course has continued to be predominantly oriented toward public speaking, how the course is taught continues to be related to that dominant form. The nature of the course has coalesced around training in oratory with the primary purpose to foster oral communication competence. Therefore, basic course content and pedagogy has demonstrated an instructional preference for performance over theory (1956, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999). Surveys reported a ratio of theory to practice with a 40:60 split respectively (1985, 1990, and 1999); however, theory and performance were not sufficiently defined in the surveys. Theory was defined (1985) as, “lecture, discussion, lecture-discussion, films, etc., and exams and their discussion” (p. 284). The lack of definitional clarity (or accuracy) for performance and theory may have distorted responses. Relatedly, reconciling theory versus practice in the classroom was identified as a challenge for the basic course (1974 and 1980). Nevertheless, practical performances have always been associated with the basic course with those performances manifesting themselves as speeches.

Speeches, assignments, grading, and feedback

Nearly every survey (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2010, and 2016) reported the number of speeches required as part of the basic course. Across these surveys most respondents reported between one-to-ten with one-to-three or four-to-six being the most popular ranges for total number of required speeches. When reviewing the majority percentages across surveys (regardless of course orientation), the majority ranges were larger in earlier years (1970, 1974, and 1980) and then began to show a decrease in the number for speeches, more commonly ranging from three to six (1985 and 1999). In 2010 and 2016, survey findings were represented by specific numbers rather than ranges. As a result they are more evenly split between one to three and four speeches per course.Footnote7 Not surprisingly, given the dominance of the public speaking orientation, the requirement of speeches and oral assignments far outweighed written assignments (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, and 2016). Instructors who placed greater emphasis on performance stressed oral activity and those who emphasized theory appeared to evaluate students’ performance through writing-centered exercises (1985). Regardless, most respondents indicated some speeches were required.

Within the ranges of required speeches, the types of speeches associated with the basic course were reported (1956, 1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2010, and 2016), which influences topics and content covered. Informative speaking (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999) was the uppermost topic covered. Persuasive speaking followed informative speaking each of those years. In only one survey (2006), extemporaneous speaking become the foremost important topic followed by persuasive and informative speaking. Researchers modified the survey question for respondents from asking what topics receive the most attention to choosing from a list of topics presented by the researchers (2006, 2010, and 2016). After the modification of that survey question, the communication process was identified as the most important topic in the course. Informative and persuasive speaking did not appear on the modified lists as reported in the publications of the most recent surveys (2010 and 2016). Whatever the number or types of required speeches, grading and feedback are coupled with the performance of the presentations.

Speeches have always been reported as having a place in the basic course, but speeches were not the only assignments included in the curriculum. Other written assignments have been reported to play a role in the basic course classroom. The closest specification that delineates oral versus written assignments that can be offered from the surveys (1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999) examines the weight given to performances (oral activities) as compared with written activities. Oral performance was defined to mean “students overtly involved in giving speeches, debating, involved in dialogue, etc.” (Citation1980, p. 284). Ratios reported an emphasis on oral over written assignments. The largest ratios reported for oral emphasis was 80 (1980 and 1990), 70 (1985), and 60 (1999). Eventually, the ratio question was dropped as part of the survey questions instead participants were asked to report the number of assignments included as part of the basic course, such as number of speeches and written exams (2016).

Basic course grading responsibility or evaluation of student performance was reported to be completed by the instructor who taught the course each semester (1970, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Respondents also reported that the instructor was the prevailing or only source of grade evaluation and feedback (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006, and 2010). How instructors provide feedback to student presenters has evolved over time, from oral forms or critique following the presentation that included written feedback after the presentation was completed (1974, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1999) to teacher evaluation only following the presentation (2006 and 2010). Instructor and peer evaluative feedback was reported by respondents (1999) but remained a minority practice (2006 and 2010). Additionally, grade inflation was reported as a challenge for instructors of the basic course (1985, 2010, and 2016), and grading and feedback associated with the basic course more recently were influenced by advances in technology.

Technology and distance education

Nearly 300 respondents (1974) indicated that video recording of student speeches was used for one or more assignments with the intended purpose of the video to be replayed for the student speaker. Subsequent surveys reported continued integration of video capture and replay (1974, 1980, 1990, 1999, and 2006). The final survey that inquired about video, concluded that video played an “important role in student performance evaluation, especially in public speaking courses” (2006, p. 432). However, less than 40% of respondents indicated video recording was used, which indicates a lack of consistency in integration and utilization of technology for feedback and self-evaluation.

Beyond video as a retrospective technological tool that provides an audience perspective for the speaker, presentational technology has advanced to support and enhance messages shared during the speaking occasion. Two- and 4-year schools reported the most widely taught technology of the basic course was PowerPoint (2006, 2010, and 2016). However, Prezi first appeared in the 2016 survey. Two-year schools reported that PowerPoint or Prezi was the most pervasive technology taught in the basic course (2016, 85.7%). That same year, 4-year schools reported PowerPoint or Prezi as the most ubiquitous technology but at a lesser majority (65.3%). Survey data did not distinguish between PowerPoint and Prezi rather the technology was grouped together. At the same time PowerPoint appeared in the surveys, the other technological event, the Internet emerged creating new questions and obstacles for basic course instructors.

The widespread reach of the Internet essentially mandated that the basic course would adapt to educate students using this new modality. Recently, respondents reported that the basic course was taught via distance education (2006, 2010, and 2016) but by only a minority of programs (2006, 20.8%). Two-year schools demonstrated the greatest implementation of distance education courses (2010, 51.5%) compared with 4-year institutions (2010, 16.4%). Unfortunately, the data are limited in regard to generalizations with only three surveys starting to assess online course delivery. Alternative forms of instruction are increasing at both two- and four-year institutions (2010 and 2016). Two-year schools appear to be more open to alternative forms of instruction and inclusion of new platforms (completely online, TV via cable, hybrid) for delivery. The training offered for teaching the basic course via distance learning fluctuated across these surveys with 9 hours being the typical amount of time committed to training instructors to teach online for both 2- and 4-year schools.

The basic course surveys identified challenges associated with distance education (2006, 2010, and 2016). Many of these issues related to the richness of teacher–student interaction, such as immediacy, peer interactions, or lack of a live audience for student speeches (2010). Other issues related to the functionality of the technology, such as student access or competent use of technology (2006, 2010, and 2016). Irrespective of the technology integrated or used to teach, the course followed higher education shifts asking about its overall influence, impact, or assessment.

Discussion

This summative discussion is presented in two parts: trends and trajectories. First, the trends section builds on insights gleaned from the meta-synthesis findings to offer insights for future basic course surveys. Second, the trajectories section identifies and puts forth several important questions related to the future of the introductory communication course. This discussion concludes with a summary of several limitations experienced in the conduct of this study.

Trends across surveys: looking backward

An exploration of trends allows a view that looks backward. Across basic course surveys meaningful insights about past trends are illuminated. For example, the prevailing moniker for the introductory course has been basic course, and since the course’s inception it has been dominated by a public speaking orientation. The three greatest trending challenges associated with the introductory course related to instructor qualifications, consistency and coordination across course sections, and training instructors. Survey trends suggested a stable or increasing number of undergraduate students enrolled in the introductory course, which coincided with the inclusion of the course in general education curricula within higher education.

As for instruction, these findings demonstrate that the teaching of the introductory course is trending away from associate and full professors. Often times senior faculty opt to focus on their specific disciplinary area of interest, instead of courses within the general education curriculum (Wehlburg, Citation2010). Instead part-time faculty and graduate students are primarily responsible for the lion’s share of introductory course instruction. The same holds true for the director role of the introductory course where the role is most frequently filled by assistant professors.

For those involved with teaching or overseeing the coordination of the introductory course, the trend of standardization has become paramount in the introductory course and perceptions of teacher autonomy has diminished. The most recent trend confronting the introductory course is how to effectively administer programmatic assessment procedures to measure learning outcomes.

The pedagogical trends of the introductory course have always coalesced around oral communication competence, thereby gravitating course instruction toward a more performance or skill-based concentration. The manifestation of these skills occurred as speeches—usually between one and four speeches per course. The most popular types of speeches are informative and persuasive. To assist in the development of oral communication competence, technology has pervaded the introductory course. For example, video replay has been used (but not consistently) to capture speeches, PowerPoint and Prezi are technologies taught to students, and the Internet has allowed the introductory course to be taught via distance education (not without its own unique set of challenges).

Sampling and survey questions

The results associated with these trends leads to a decision-oriented framework for thinking about survey questions and their characteristics as well as sampling. While the past survey studies tended to vary sampling procedures and survey question design to respond to the time and context, other approaches may now be more in order as we consider the future of the course. Revitalized and systematic sampling of the introductory course population and the desired elements (or basic units that comprise the population) would help to increase the declining response rates associated with the course surveys. Methods and techniques for identification and selection of a representative sample of those individuals most heavily involved with the introductory course would assure greater statistical inference. Additionally, increasing cooperation rates through fieldwork and appropriate follow-up procedures would heighten validity of the introductory course survey findings and its generalizability.

In order to improve sampling, we suggest targeting specific populations that are most heavily involved with the course (i.e., introductory course directors, lead faculty at two-year and four-year institutions, and instructors who are regularly involved in the basic course). The NCA’s Basic Course Division compiled a list of course directors from across the US in 2014, if the list is kept current, the names could be useful for an entry point to ensure sampling consistency. In addition to sampling, comparing trends across certain questions or surveys was difficult in this present study due to question modifications.

In future studies, critical decisions about consistency and comparability among various aspects of question characteristics, including question topic, question type and response dimension, conceptualization and operationalization of the target object, question structure, question form, response categories, question implementation, and question wording are imperative for interpreting trends across survey data (see Schaeffer & Dykema, Citation2011). Widespread and thorough discussions about question characteristics in future surveys would enable study designs to account for relationships among and across question characteristics and identify gaps in current knowledge. To contribute to these discussions and future survey endeavors, the questions outlined in are recommended for inclusion in future cross-sectional introductory communication course surveys. The development of a replicable and comparable question design across surveys with intentional sampling in mind would allow for increased trend and trajectory verification of the introductory course.

Table 2. Essential questions for introductory communication course surveys.

Trajectories for the course: looking forward

This study’s meta-synthesis highlighted several trends related to themes and topics connected with the basic course that are likely to inform disciplinary dialogue and future pedagogical and research endeavors of scholar-teachers and administrators. The implications of these trends provide insights into the position, momentum, and forward path of the course. Trajectories are put forth as questions for reflection and to provoke contemplation and dialogue to look forward. While other questions may be of interest or insight to teachers and scholars, the following questions emerged as cruxes from the summative findings of 60 years.

What should be the “moniker” used to identify the course?

The announcement headline of the Basic Communication Course Annual stated, “Now online: Basic Communication Course Annual presents the latest research on the introductory communication course” (J. P. Mazer, personal communication, January 14, 2019). The inclusion of “introductory communication course” follows suit with a trend that has occurred in the Communication Education journal that spans two editorships—Hess (2015–2017) and Dannels (2018–2020). Such adaptation to the moniker invites obvious questions: Does evolving from basic to introductory help to define the course more clearly? Should the course’s definition, last defined by Gibson, Hanna, and Huddleston (Citation1985), be updated again as well?

The metaphor of a front porch has been used to situate the importance of the course (Beebe, Citation2013). Ironically, the architectural intent of the front porch was to shift from an only interior perspective from inside the home to how the house looked from the exterior (Mugeraur, Citation1993). The front porch functioned as an intermediary, a place to see and be seen by other people. How does the moniker situate the course both within the discipline of communication and across other academic disciplines? The chasm that exists in how to most appropriately label the course may derive from the fragmented and convergent disciplinary roots, since there are departments of communication that include such fields of study as mass communication, journalism, advertising, etc. Could a rebranding of the moniker better parallel cross-disciplinary knowledge to establish a clear and coherent identity (see Eadie, Citation2011)? What are connotations and implications for how the discipline situates and trademarks its “foundation course” (Duffy, Citation1917, p. 163)? How does the label for the course communicate its purpose for learners, teachers, and administrators? Interiorly, how does the label align with the course orientation and content?

Who should be teaching the course given its role in the curriculum?

Historically, the Communication discipline has demonstrated a shift away from providing communication skills training from the most qualified of its ranks, especially over the most recent surveys (1999, 2006, 2010, and 2016). Responsibility has shifted to junior faculty and graduate teaching assistants to instruct the majority of undergraduate students associated with the course. In addition, the director’s role is currently occupied by an assistant professor majority. Such benchmarks underline a tolerance for individuals (often with the lowest levels of training and disciplinary education) to be entrusted with providing the lion’s share of the introductory communication skills training. Unfortunately, this issue has plagued the Communication discipline for some time. More than three decades earlier, Friedrich (Citation1985) made similar observations,

One might, of course, argue that the communication discipline has had little choice in or responsibility for creating a situation in which the majority of its communication skills training is provided by ill-prepared instructors. This argument might be more persuasive, however, were members of the discipline more actively working to change the situation and if a larger portion of the discipline’s intellectual energies were devoted to creating a solid theoretical and research-based foundation on which to develop training in communication skills. Unfortunately, this is not the case. (p. 248)

How does the introductory communication course introduce the breadth and depth of the discipline to students?

Beebe (Citation2013) reasoned that the introductory course “is the largest single comprehensive instructional source of information about human communication in the world” (p. 2). This meta-synthesis undeniably confirms that the primary purpose of the course is public speaking, which concentrates content and learning around oral communication skills.

The findings of this study indicate how little the core content of the introductory communication course and its assignments have changed over roughly 60 years of the basic course surveys. Even though, the world has become increasingly globalized over the past half century. Public speaking—the majority of the time translates to standing in front of an audience (usually composed of the same people each time), platform-oratory style, with the same type of speeches being presented (informative, persuasive, etc.) in the introductory communication course. The lack of adaptation to the course has the potential to be a disturbing implication of the analysis or, perhaps, these findings are an opportunity to reclaim the discipline’s heritage as “speech teachers” (Keith, Citation2011, p. 90) to reaffirm the course’s pedagogical trajectory. However, what is in doubt is how the course situates and introduces its purpose within the larger continuum of human communication. Are those involved with the course able to articulate how the course is situated in relation to the larger discipline of communication? Why is it the centralized course for introducing learners to the discipline? How does the course help learners make sense of the tiered levels of communication (see Powers, Citation1995)? Or is the course simply a tradition and homage to its foundational and historical roots? How many undergraduate students are actually being introduced to the breadth and depth of the communication discipline through the introductory communication course?

Implications for introductory communication course in general education

The current structure of formalized general education can be traced to the resurgence of the general education programs of the late 1970s and early 1980s (Gaff, Citation1983; Miller, Citation1988). The introductory communication course has been reported to be an essential feature of general education programs at most colleges and universities (i.e., Sellnow & Martin, Citation2010; Valenzano, Wallace, & Morreale, Citation2014); however, this perspective has not been consistently shared.

Bok (Citation2006) reported that oral communication instruction is a general education requirement at less than half of all undergraduate institutions. To further illustrate Bok’s point, the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA, Citation2010) examined general education programs at more than 700 institutions of higher education across the US to outline the core curriculum courses most typically provided to undergraduates. Results of the ACTA investigation identified seven key subjects included in the majority of core curricula: (1) composition, (2) literature, (3) foreign language, (4) US government or history, (5) economics, (6) mathematics, and (7) natural or physical science. Communication was not credited consistently across institutional course catalogues as a general education or core curriculum requirement to rank in the top seven key subjects reported.

In order for communication departments, chairpersons, or introductory course coordinators to secure a position among general education programs across the nation a starting place is to advocate for the value of the skills and knowledge of the introductory course. Institutional protocols and procedures can be vast and cumbersome to navigate, but if the introductory course adds value to future leaders and problem-solvers of tomorrow—it should be worth the effort. The essential aspect of the introductory course is to illustrate how the skills and knowledge of the course translates and transcends disciplinary boundaries.

A tool for engaging these critical dialogues—externally to institutional stakeholders—is found in the findings generated by the NCA Core Competencies Task Force. Former NCA President Steven A. Beebe charged the Task Force with a goal: “To investigate and identify, if possible, a set of core competencies applicable to introductory communication courses within and across a variety of communication contexts” (NCA, Citation2013, p. 2). The Core Competencies for Introductory Communication Courses (Citation2014) makes accessible “a set of core competencies applicable to introductory communication courses within and across a variety of communication contexts” (p. 4). Moreover, each of the seven competency areasFootnote8 put forth by the NCA Core Competencies Task Force relate directly to either predominant version of the introductory communication course—public speaking or hybrid.

The NCA Learning Outcomes in Communication (LOC; Citation2015) further assist in these all-important conversations that situate the value of the introductory communication course. LOC provide a tuningFootnote9 mechanism for the development of a coordinated programmatic curricula that offers a platform for identifying a common starting pitch (Beebe, Citation2016). The purpose of tuning for the discipline of communication is to educate learners in the principles and practices of competent oral communication (and demonstrate how those skills are different from written communication taught by English as well as how the knowledge and skills edified by the field transcend disciplinary boundaries). Clear introductory course LOC function as an alignment apparatus for programs and departments of communication. When appropriately implemented a unified and coordinated introductory course accurately fulfills the preliminary and intermediary functions to align overall objectives of the academic unit and meaningfully scaffold curriculum for learners. As Beebe (Citation2016) noted, tuning variation will inevitably exist across academic programs and departments; however, the process of tuning encourages introductory courses to find an adaptative (and disciplinary) harmony.

Limitations

Meta-syntheses have limitations in that they are constrained to research questions and designs offered as secondary data. As such, the new analysis may differentiate from the raw data (Major, Citation2010). Syntheses may decontextualize contexts, neglect particular findings, or ignore previous assumptions; however, the summative process and product attempt to overcome these limitations. In this study, the findings were limited to 11 studies on the overall introductory course; other studies, directly and indirectly addressing the evolution of the introductory communication course, may further highlight changes, fads, and trends of interest. Further research should explore different artifacts surrounding the introductory course and review its evolution and implementation in the discipline.

Conclusion

Hargis (Citation1956) was the first to formally ask in publication, “What is the first course in speech?” (p. 26). Since that time, others associated with the discipline have asked that same question and more will continue to ask it—because the question is important. The question contextualizes our comprehension of the course retroactively and aids in influencing proactive discussions about the future of the course. In order to be confident about answering that question, the communication discipline must be cognizant of both the strengths and weaknesses of the course, prepared to contribute equally to its growth and stability, and cautious about its immortality and concerned about how to guide its future trajectories. Unfortunately, there is no formula for maintaining and strengthening the introductory communication course, only informed and evidence-based decision-making. The continuation of the introductory course surveys and meta-synthesis of those artifacts will help to illuminate and inform those decisions.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 We acknowledge that different nomenclatures have been utilized to label the course since its inception. Over the years, the “front porch” (Beebe, Citation2013, p. 3) communication course has been labeled by an assortment of monikers—foundation course (Duffy, Citation1917), beginning course (Hollister, Citation1917), fundamental course (Forncrook, Citation1918), first-year course (Newcomb, Citation1920), elementary college course in speaking (Flemming, Citation1921), basic course (Lindsley, Citation1932), and introductory course (Page, Citation1940). Prior scholarship has relied primarily on the terminology of basic course. The conceptual difference is a contemporary distinction to acknowledge the perceptions between disciplinary outsiders and those involved in the field of communication. Largely, people perceive “basic” as a reference to being simple or simplistic (Fassett, Citation2016), and this language exacerbates the problem of credibility for the course (J. A. Hess, personal communication, December 11, 2016). We utilize basic course or basic communication course in the introduction, literature review, method, and results for consistency and tradition; however, we use introductory when providing a rationale or commentary. Change occurs incrementally as a conscious decision. As an outgrowth of these decisions, the written content that occurs as part of this manuscript’s findings begins to incorporate the use of the term introductory.

2 Although Hargis (Citation1956) is credited with being the first to formally ask, “What is the first course in speech?” the origin of the question relates directly to the conception of contemporary departments of speech (Woolbert, Citation1916). The nature of the “first course” was discussed before and since the inception in 1914 of the National Association of Academic Teachers of Public Speaking (later National Communication Association). The basic course survey study by Hargis is only a single element or entry point of a larger context of how the introductory communication course reflects not only the “front porch” but the entire house of the communication discipline.

3 Sample sizes rated from 188 (2016) to 564 (1970) and averaged 389.27 (SD = 151.02) across reported and calculable studies. Response rates varied greatly between studies. Overall, the response rates were: 50% (1956), 46.16% (1963), 63.58% (1970), 42.91%* (1974), 19.76%* (1980), 26.56% (1985), 27.61% (1990), 50% (1999), 23.53% (2006), 16.06%* (2010), and not provided or calculable (2016). Asterisks were calculated from the data by taking the questionnaires distributed and dividing by usable responses (not previously listed in the study). In 2010, Morreale et al. used stratified random sampling amongst 2- and 4-year programs separately and are not easily comparable with other studies, and reported 2-year at 54% and 4-year at 31% for a combined response of 34%.

4 We consulted with the first author’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure participation protections with this member check. The IRB determined that the project did not meet the definition of human subjects research.

5 Hybrid usually encompassed hybrid, combination, and/or multiple approaches. Distinctions between combination and multiple were not always clearly delineated. In 1980, combination refers to public speaking, interpersonal, and small group; however, multiple was not described. We collapsed these percentages. The variation in open-ended responses from survey to survey encapsulate other forms of hybrid descriptions and the variations represented hybrid descriptions. Combining these forms suggests the hybrid orientation has retain a stable percentage and status over time across basic course surveys.

6 The initial survey (1956) assessed whether the basic course was required for graduation. According to respondents, 42% of colleges or universities did require the course and 32.2% required the course to be completed for departments or majors. In 1965, 51.23% had to satisfactorily complete the basic course before their graduation. Between 1965 and 2006, questions did not explore general education as much as student status (e.g., freshman, sophomore, junior, senior) and who was completing the course. In 2006, basic course surveys began to consider the course’s participation in general education programing. The majority (50.2%) of participants reported that the course was required in their institution’s general education requirement with the majority requiring public speaking in comparison with the hybrid communication course. This percentage increased in subsequent surveys (2010, 60.5%; 2016, 79.4%). Slight variation in percentages occurred between 2- and 4-year schools. Two-year schools had higher general education requirements for the course. In addition, surveys indicated that respondents did not consistently require communication majors to complete the basic course (2006, 25.3%; 2010, 37.9%; 2016, 42.3%).

7 Unfortunately, it is difficult to explicate any trends since similar metrics (e.g., means, standard deviations, ranges, etc.) were not provided across the surveys nor delineated for each orientation of course (i.e., public speaking, fundamentals, small group, interpersonal communication, etc.) except for the 1974 survey. For instance, 1970 reported the majority without specific breakdowns; 1974 offered percentages for none, one to three speeches, four to six, seven to eight, and nine to 10; 1980 reported one to three, four to 10, and 10 plus. The groupings continued to vary depending on the survey. As a result, it may suggest that the orientation would most likely influence the number of speeches; however limited, as it exists to determine that trend. The 1974 survey delineated the number of speeches by course orientation and observed that regardless of specified orientation the majority of introductory courses taught four to six speeches, with only the “communication” course requiring slightly less with one to three speeches.

8 The seven core competencies developed by the NCA Core Competencies Task Force: (1) monitoring and presenting your self, (2) practicing communication ethics, (3) adapting to others, (4) practicing effective listening, (5) expressing messages, (6) identifying and explaining fundamental communication processes, and (7) creating and analyzing message strategies.

9 According to the Institute of Evidence-Based Change (Citation2012),

Tuning is a faculty-driven process that makes what students know, understand, and are able to do at the completion of a degree in a given discipline or professional program explicit for students, faculty, family, employers and other stakeholders … Tuning in a field provides a faculty-constructed profile that says to the world what a degree in X (bachelor’s/master’s) or preparation for a major in X (associate’s) means (pp. 1–2).

References

- American Council of Trustees and Alumni. (2010). What will they learn? A survey of core requirements at our nation’s colleges and universities. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.goacta.org/initiatives/what_will_they_learn

- Beebe, S. A. (2013). Message from the president: “Our front porch”. Spectra, 49(2), 3–22.

- Beebe, S. A. (2016). Continuing the conversation: Listening to the oboe. Communication Education, 65, 498–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1208260. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1204464

- Bok, D. (2006). Our underachieving colleges: A candid look at how much students learn and why they should be learning more. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bondas, T., & Hall, E. O. C. (2007). A decade of metasynthesis research in health sciences: A meta-method study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 2, 101–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620701251684.

- Core Competencies Group. (2014). Core competencies for introductory communication courses. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from www.natcom.org/sites/default/files/pages/Basic_Course_and_Gen_Ed_Core_Competencies_Handout_April_2014.pdf

- Dedmon, D. N., & Frandsen, K. D. (1964). The “required first course in speech: A survey. Speech Teacher, 14, 33–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634526409377336.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Carvers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6, 35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35.

- Duffy, W. R. (1917). The foundation course in public speaking at the University of Texas. Quarterly Journal of Public Speaking, 3, 163–171.

- Eadie, W. F. (2011). Stories we tell: Fragmentation and convergence in communication disciplinary history. Review of Communication, 11, 161–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2011.578257.

- Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M. J., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 186–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111425493.

- Fassett, D. L. (2016). Beyond basic: Developing our work in and through the introductory communication course. Review of Communication, 16, 125–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2016.1187449e. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2016.1187449

- Fassett, D. L., & Warren, J. T. (2012). Coordinating the communication course: A guidebook. Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martin.

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2018). A guide to qualitative meta-synthesis. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Flemming, E. G. (1921). An elementary college course in speaking. Quarterly Journal of Speech Education, 7, 189–212. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00335632109379335

- Fleuriet, C. (1993). How to standardize the basic course. In L. W. Hugenberg, P. L. Gray, & D. M. Trank (Eds.), Teaching & directing the basic communications course (pp. 155–166). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- Ford, W. S. Z., & Wolvin, A. D. (1993). The differential impact of a basic communication course on perceived communication competencies in class, work, and social contexts. Communication Education, 42, 215–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529309378929.

- Forncrook, E. M. (1918). A fundamental course in speech training. Quarterly Journal of Speech Education, 4, 271–289. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00335631809360679

- Friedrich, G. W. (1985). Speech communication education in American colleges and universities. In T. W. Benson (Ed.), Speech communication in the 20th century (pp. 235–252). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Gaff, J. G. (1983). General education today: A critical analysis of controversies, practices, and reforms. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Gehrke, P. J. (2016a). Introduction to special issue on teaching first-year communication courses. Review of Communication, 16, 109–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2016.1193943. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2016.1195542

- Gehrke, P. J. (2016b). Epilogue: A manifesto for teaching public speaking. Review of Communication, 16, 246–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2016.1193943.

- Gehrke, P. J., & Keith, W. M. (2015). Introduction: A brief history of the National Communication Association. In P. J. Gehrke & W. M. Keith (Eds.), A century of communication studies: The unfinished conversation (pp. 2–25). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gibson, J. W., Gruner, C. R., Brooks, W. D., & Petrie, C. R. Jr. (1970). The first course in speech: A survey of U.S. colleges and universities. The Speech Teacher, 19, 13–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03634527009377786

- Gibson, J. W., Gruner, C. R., Hanna, M. S., Smythe, M.-J., & Hayes, M. T. (1980). The basic course in speech at U.S. colleges and universities: III. Communication Education, 29, 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634528009378387.

- Gibson, J. W., Hanna, M. S., & Huddleston, B. M. (1985). The basic speech course at U.S. Colleges and universities: IV. Communication Education, 34, 281–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634528509378620.

- Gibson, J. W., Hanna, M. S., & Leichty, G. (1990). The basic speech course at U.S. colleges and universities: V. Basic Communication Course Annual, 1, 233–257.

- Gibson, J. W., Kline, J. A., & Gruner, C. R. (1974). A re-examination of the first course in speech at U.S. Colleges and universities. The Speech Teacher, 23, 206–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634527409378089.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Handford, C. J. (1993). Service course or introduction to the discipline. In L. W. Hugenberg, P. L. Gray, & D. M. Trank (Eds.), Teaching & directing the basic communications course (pp. 27–32). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- Hargis, D. (1956). The first course in speech. The Speech Teacher, 5, 26–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634525609376775.

- Hollister, R. D. T. (1917). The beginning course in oratory at the University of Michigan. Quarterly Journal of Public Speaking, 3, 172–173.

- Institute of Evidence-Based Change. (2012). Tuning American higher education: The process. Long Beach, CA: Author. Retrieved from http://degreeprofile.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Tuning-Higher-Education-The-Process.pdf

- Keith, W. M. (2011). We are the speech teachers. Review of Communication, 11, 83–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2010.547589.

- LeFebvre, L. (2017). Basic course in communication. In M. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 87–90). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411.n35.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Lindsley, C. F. (1932). The basic college courses in speech. In W. A. Cable (Ed.), A program of speech education in a democracy (pp. 136–151). Boston, MA: Expression Company.

- Major, C. H. (2010). Do virtual professors dream of electric students? University faculty experiences with online distance education. Teachers College Record, 112, 2154–2208.

- Major, C., & Savin-Baden, M. (2010). An introduction to qualitative research synthesis: Managing the information explosion in social science research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Miller, G. E. (1988). The meaning of general education: The emergence of a curriculum paradigm. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Morreale, S. P., Hanna, M. S., Berko, R. M., & Gibson, J. W. (1999). The basic communication course in U. S. Colleges and Universities: VI. Basic Communication Course Annual, 11, 1–36.

- Morreale, S. P., Hugenberg, L., & Worley, D. (2006). The basic communication course at U.S. Colleges and universities in the 21st century: Study VII. Communication Education, 55, 415–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520600879162.

- Morreale, S. P., Myers, S. A., Backlund, P. M., & Simonds, C. J. (2016). Study IX of the basic communication course at two- and four-year U.S. Colleges and universities: A re-examination of our discipline’s “front porch”. Communication Education, 65, 338–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1073339.

- Morreale, S. P., Valenzano, J. M., & Bauer, J. A. (2017). Why communication education is important: A third study on the centrality of the discipline’s content and pedagogy. Communication Education, 66, 402–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1265136.

- Morreale, S. P., Worley, D. W., & Hugenberg, B. (2010). The basic communication course at Two- and four-year U.S. Colleges and universities: Study VIII—The 40th Anniversary. Communication Education, 59, 405–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634521003637124.

- Mugeraur, R. (1993). Toward an architectural vocabulary: The porch as a between. In D. Seamon (Ed.), Dwelling, seeing, and designing: Toward a phenomenological ecology (pp. 103–128). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- National Communication Association. (2012). Revised resolution on the role of communication in general education. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from www.natcom.org/sites/default/files/pages/Basic_Course_and_Gen_Ed_Resolution_in_Support_of_Communication_as_a_General.pdf

- National Communication Association. (2013). Core competencies task force report. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from www.natcom.org/sites/default/files/pages/Basic_Course_and_Gen_Ed_NCA_Core_Competencies_Report_December_2013.pdf

- National Communication Association. (2015). Drawing learning outcomes in communication into meaningful practice: Learning outcomes in communication project. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.natcom.org/learning-outcomes-communication

- Newcomb, C. M. (1920). The standardization of first year courses. Quarterly Journal of Speech Education, 6, 43–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00335632009379280

- Page, C. R. (1940). A comparative study of the introductory course in speech (Unpublished master’s thesis). Baylor University, Waco, Texas.

- Powers, J. H. (1995). On the intellectual structure of the human communication discipline. Communication Education, 44, 191–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509379012.

- Sandelowski, M. (2006). “Meta-Jeopardy”: The crisis of representation in qualitative metasynthesis. Nursing Outlook, 54, 10–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2005.05.004.

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer.

- Schaeffer, N. C., & Dykema, J. (2011). Questions for surveys: Current trends and future directions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75, 909–961. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr048.

- Sellnow, D. D., & Martin, J. M. (2010). The basic course in communication: Where do we go from here? In D. L. Fassett & J. T. Warren (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of communication and instruction (pp. 33–53). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Stephen, T. D. (2015). The scholarly communication of communication scholars: Centennial trends in a surging conversation. In P. J. Gehrke & W. M. Keith (Eds.), A century of communication studies: The unfinished conversation (pp. 107–127). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Thorne, S. E. (2008). Meta-synthesis. In L. M. Given (Ed.), SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 1 and 2) (pp. 510–513). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Trueblood, T. C. (1915). College courses in public speaking. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 1, 260–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00335631509360492.

- Valenzano, J. M., Wallace, S. P. & Morreale, S. P. (2014). Consistency and change: The (r) evolution of the basic communication course. Communication Education, 63, 355–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2014.911928

- Weaver, R. L. II. (1976). Directing the basic communication course. Communication Education, 25, 203–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634527609384627

- Wehlburg, C. M. (2010). Integrated general education: A brief look back. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 121, 3–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tl