ABSTRACT

This study aimed to analyze how adolescent girls residing in Kathmandu valley, Nepal, talk about food within the context of their everyday experiences. We conducted 10 in-depth and four focus group interviews. Qualitative thematic analysis based on the constructivist paradigm was used to organize the interviews. The Utilitarian domain contained health statements using biomedical language and lay theories on health. Hedonic talk emphasized the taste of food, but notions about enjoyment were limited. Collective talk constructed an ideal family. In agency talk, the interviewees described their active role in achieving a slim body. Participants were not concerned about food insecurity but about eating too much.

Introduction

The global adolescent population is larger than ever before and projected to increase in the coming decades (United Nations, Citation2015a). Improving the health of the 1.2 billion 10–19-year-old people, out of whom 90% live in low- and middle-income countries, will be essential for achieving global health and policy goals such as the United Nations Sustainable Development goals, and the specific targets included in the United Nations Secretary General’s Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (United Nations Citation2015). Currently, the main body of research on adolescent health is predominantly focused on sexual and reproductive health and HIV. However, for the most effective actions and investments, it will be essential to extend the scope increasingly to problems caused by poverty, including malnutrition encompassing obesity, overweight and underweight (Hawkes et al. Citation2020; Patton et al. Citation2016).

In many contexts, adolescent girls are the most vulnerable to poverty as well as the influences of nutrition related cultural and gender norms, which often discriminate against them (Christian and Smith Citation2018). Overweight and obesity (defined as children and youth >+1 standard deviations (SD) and +2 SD from age- and sex-specific population reference body mass index) affect one in every four adolescents globally and is of particular concern among girls (Akseer et al. Citation2017). Undernutrition rate in adolescents girls varies depending on indicator: using anemia (hemoglobin <115 g for individuals aged 10–24 years) as a sign, the global prevalence of undernutrition among adolescents girls is 24% (Azzopardi et al. Citation2019) and by underweight (<-2 standard deviations from median body mass index by age and sex) prevalence is about 5% (Akseer et al. Citation2017). Roughly speaking, overweight and obesity rates are increasing among adolescents in the Americas and Mediterranean and Pacific Regions, and undernutrition remains a major public health concern in many locations of South Asian and African countries (Akseer et al. Citation2017; Jaacks, Slining, and Popkin Citation2015).

Nepal is a low-income South Asian country where the number of adolescents stands at around 6.4 million, almost quarter of the total population (census 2011/12). Over 20% of adolescent girls are underweight and prevalence is increasing, especially in the urban areas by 1.4% annually. Only 3–5% of adolescents girls are obese (Cunningham et al. Citation2020; Jaacks, Slining, and Popkin Citation2015; Shrestha Citation2017). In Kathmandu Valley, the capital area, the overall prevalence of underweight is estimated to be 24% (Shrestha Citation2017).

While describing the overall prevalence of the problem, the percentages do not give voice to adolescent girls, which will be necessary for a more comprehensive understanding of malnutrition (Neufeld et al. Citation2022). Earlier literature has shown that there are various other factors people take into account when choosing what to eat, and a focus on malnutrition and health may lead to emphasis on a set of motives that are of limited significance for adolescent girls (Steptoe, Pollard, and Wardle Citation1995). In everyday life, food is embedded in a matrix of meanings and social, cultural, and economic relationships (Banna et al. Citation2015; Brown et al. Citation2015; Contento et al. Citation2006; Elliott Citation2014; Rathi, Riddell, and Worsley Citation2018). Thus, food is a socio-cultural product with a meaning and importance far beyond its nutritional or caloric content (Akseer et al. Citation2017; Elliott Citation2014). Food not only nourishes but it also signifies, and food choices and practices convey something meaningful about people, to themselves and to others. Socio-constructivist approach using qualitative interview data enables accessing themes related to the meaning of personal experiences and uncovering differences in conceptualizations due to cultural or contextual factors enables (Bryman et al. Citation2022; Saldana Citation2015).

There is existing but rather limited literature on determinants of adolescent girls’ food choices in low- and middle-income countries, but their own voice is seldom heard (Neufeld et al. Citation2022; Wells et al. Citation2021). We found three studies using qualitative interviews conducted in South America (Banna et al. Citation2015; Monge-Rojas et al. Citation2005; Verstraeten et al. Citation2014) and four studies in Africa (Brown et al. Citation2015; Dapi et al. Citation2007; Muryn Citation2001; Sedibe et al. Citation2014) reporting adolescent girls’ view to food and eating. Despite different geographical contexts with varying empirical findings, certain key themes emerged from these studies including (dis)satisfaction with the body, social relationships, quality of food and ability to exercise agency.

We didn’t find studies on adolescent food-talk in the Asian countries in general or in Nepal. However, in Nepal, persistent societal and gendered norms and underlying structural factors restrict adolescent girls in several life domains including food and nutrition (Madjdian et al. Citation2022).-Therefore, this study aimed at strengthening understanding of complexities related to malnutrition by analyzing how Nepali adolescent girls talked about food within the context of their everyday experiences. More specifically, we wanted to see how adolescent girls construct and make meaning of their social context and how they elaborate on identity through food-talk. Additionally, we wanted to examine if notions of undernutrition were included in the accounts.

Methods

Participants and interviews

To be eligible for the study, participants had to be young women between 14 and 18 years of age and have residence in Kathmandu Valley. There were no exclusion criteria and all the invited adolescent girls decided to participate. We used purposeful sampling (M. Patton Citation2015). We identified adolescent girls for interviews through public and private schools by contacting the teachers. In order to add experiences from participants with different backgrounds, we also enrolled participants who were school dropouts through teachers. We told the teachers the themes of the interviews, and they passed on the information to the adolescent girls they contacted for individual interviews and focus group interviews. We also told the teachers that we wanted to interview participants with varying backgrounds and that the interviews will be anonymized and read only by two researchers. After receiving verbal information about the interview themes and confidentiality, the participants gave a consent that was recorded. Participants received a small token (a notebook) to compensate for their time.

We conducted in-depth and focus group interviews with the participants using themes based on the Quality-of-Life questionnaire, a cross-culturally validated tool (The Whoqol Group 1998). The main themes of the interviews were health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and living environment. While reading the interview transcripts, we noticed that food-talk had a central place in the accounts, and it deserved a detailed analysis. Researchers read the interviews concurrently to the data collection and added some questions about unclear issues. Sample size was defined by data saturation principle, i.e. interviews were continued until nothing new was being generated under the main themes (Green and Thorogood Citation2009).

A Nepali young female researcher conducted all the interviews (LG) in Nepali language using a thematic interview guide. First, she conducted individual in-depth interviews for allowing the participants enough time to develop their own accounts on the issues important to them. Next, she conducted focus group (FG) interviews with different participants than in the in-depth interviews because we wanted to gain understanding about shared views on well-being and gain understanding of interaction dynamics (Green and Thorogood Citation2009). All the interviews were conducted at school premises, audio-recorded and transcribed.

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council 2289/2016.

Theoretical underpinnings

Already in 1961 Roland Barthes suggested that food “is not only a collection of products that can be used for statistical or nutritional studies. It is also, and at the same time, a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behavior” which point to the importance of non-nutritional aspect of food by emphasizing symbolic aspects of diet (Barthes Citation1961). Along these lines, we based the analysis on socio-constructivist paradigm which suggested that individual (Barthes Citation1961)s develop varied and multiple subjective meanings of their experiences through interaction with others as well as through their individual historical and cultural norms (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966; Lo Monaco and Bonetto Citation2019). Additionally, we assumed that the various meanings of food are communicated not only by actual food consumption but also through food-talk, the way the participants describe food choices, preparing meals, eating, and sourcing groceries in their everyday context (Antin and Hunt Citation2012; Rathi, Riddell, and Worsley Citation2016). Thus, food-talk serves as a sign for a way of living among the members of a given society constructing social identities and lifestyles (Barthes Citation1961; Lupton Citation1996). Additionally, according to social-constructivist tradition, we assumed that each text can transcend its literal sense and show an extra-textual reality (Alaszewski Citation2006).

Data analysis

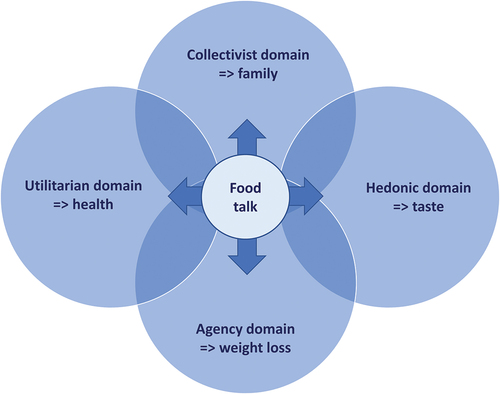

There are several overlapping research traditions that have examined food-talkfor example, studies on food choices, studies on cultural meanings of foods and consumer studies, all of which have emphasized the complexity of food-related issues. We summarized the existing theoretical literature and developed a concept map based on two continuums which we used for organizing interview excerpts (). Since there are so few studies on Asian countries, we didn’t set any geographical limitations for the literature but paid attention on the thematic upper-level concepts rather than the empirical findings. In the first continuum, food choices were considered to be driven between utilitarian and hedonic motivations. In food studies, utilitarian dimension refers to the functional or nutritional benefits of foods and hedonic dimension refers to the enjoyment and pleasure of consumption (Sarabia-Andreu et al. Citation2020). The second continuum spanned between collectivist and individualistic dimensions of food-talk. Collectivist identity is closely tied to the social system to which a person belongs, often including extended families, whereas individualists are emotionally independent and focused on personal freedom and self-actualization. (Hofstede et al. Citation2010)

We used thematic content analysis (Bryman et al. Citation2022) and moved between bottom-up (inductive, emerging themes) and top-down (deductive, using the key theoretical concepts in the concept map). The coding process involved identifying themes, categories, and their interconnections. During the first phase, both researchers read the interviews and one researcher (UA) structured the material using Atlas.ti software (version 22.0, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Germany 2022). Next, we created a joint code book for individual and focus group interviews using the software. Both researchers reviewed the codebook adding structure to it by paying attention to both manifest and latent content (Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004).

Results

We conducted 10 individual interviews (participant details in ) and four focus group interviews with five to six different participants. Age of the participants varied between 14 and 19 years and length of the interviews varied between 30 and 90 min. We did not directly ask about the socioeconomic position of the participants, but when talking about their families and living arrangements, some of the interviewees described themselves as poor, some well-to-do. Additionally, most of the participants explicitly stated to be relatively healthy.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants in the individual interviews.

Utilitarian talk: health

When the participants started discussing their everyday practices, they treated food as a necessary substance required for sustaining and making it possible to work and to study. Statements were citing nutritional aspects of foods as “facts” which the participants did not question or deliberate.

Anyway, we know we cannot live without food, so the main purpose [of eating] is for energy, to make ourselves strong and do our work. (Participant 1)

Related to this goal, the interviewees discussed energy, vitamins, nutrients, and proteins in technical and biological terms both in the individual interviews and focus groups. Interviewees also emphasized that eating fresh, self-grown vegetables, avoiding pesticides, and eating a lot of fruits are essential for health promotion.

The participants also readily talked about the discrepancy between the health “facts” and their everyday diet containing little fresh fruits and vegetables.

Interviewer: How nutritious do you think is the food you eat?

Participant: I think it is.

Interviewer: What makes you think so?

Participant: Because we eat good vegetables, so.

Interviewer: Good means?

Participant: Healthy, fresh.

Interviewer: What do you eat on a regular basis?

Participant: Rice, pulses, curry. (Participant 4)

When the interviewer first asked in the focus group interviews about health, all the participants unanimously declared to be healthy. However, when probed further, they acknowledged the negative implications of eating substandard quality food, and they considered their diets to be insufficient for sustaining health.

Interviewer: Everyone thinks they are healthy?

Everyone: Yes!

Interviewer: Why do you say so?

Participant 2: I don’t think I am healthy because sometimes I drink less water or eat late and our daily food is not regular. Sometimes in the morning if we have time and we drink tea then tea can also hamper health and sometimes if we don’t drink tea for a month then after that if we drink tea, then our stomach is upset, or some changes occurs.

Interviewer: Mmh … that’s why you think you are not healthy?

Participant 2: umm … that and again …

Interviewer: What do others think?

Participant 3: The food we need for our body, the nutrients we are not getting, because of our diet, also we are not sometimes healthy as we feel.

Participant 2: We have to eat what we need but we have to eat only a little.

Everyone: Just like that! (FGD 4)

Opinions about meat products and milk were divided because some of the participants were vegetarians. As a special concern, all the interviewees emphasized that home cooked food is healthy and eating outside home should be avoided. The participants told that eating outside home means eating “junk food” in cheap eateries.

How can we take care of health … by eating fruits, meat and milk in proper time and as per needed and not eating outside home. (Participant 1)

Hedonic talk: taste but seldom pleasure

After utilitarian talk, interviewees quickly and readily described how taste guided their everyday food practices. Respondents explained lengthy about their favorite foods and foods they disliked. Interestingly, taste was discussed completely separately from the health claims. Participants especially deliberated the role of oily and fried foods.

Mostly I like fried food items. Sometimes I eat rice with pulses, sometimes I need fried foods, sometimes I do not eat at all. (Participant 10)

Many of the interviewees were very particular about their taste preferences, but they typically gave a list of items they disliked.

Participant: I do not like pickles, I eat all other.

Interviewer: So you eat pulses and vegetables. Which vegetables do you dislike?

Participant: I do not like eggplant.

Interviewer: What is your favorite vegetable?

Participant: Potato.

Interviewer: And vegetables you do not like?

Participant: If it is mixed with onion.

Interviewer: Any specific vegetables you do not like?

Respondent: I do not like sponge gourd, eggplant. I like all other. (Participant 1)

Another theme of hedonic consumption besides taste was pleasure. However, participants talked about pleasure only in the FGs when explicitly asked. They associated enjoyment with having meals with friends. There were no references to pleasure when they talked about family meals.

Interviewer: What things make you enjoy your life?

Respondents laughing: All of us eating lunch together [at school]. (FG2)

Collectivist talk: constructing family

In manifest talk, participants made value judgments based on the ability of their family to provide food and other commodities. For many, the uppermost feeling was gratitude about “a good family.”

They [parents] have sent me to a good school and they provided me with good clothes and good food to eat. (FGD 4, participant 4)

An exchange of ideas in FG serves as an example of the centrality of both food and family in the interviews.

Interviewer: What is important for good life?

Participant 3: Nutritious food, good environment and and … (pause)

Participant 4: sound environment at home…

Participant 3 continues: … good food and sound environment at home and if we don’t have to see the fights of mother and father and brothers also behaves properly. (FGD3)

Latent in the interviews was an ideal of a nuclear family having meals together. However, many of interviewees did not stay with their parents, and they regretted that.

Participant: I stay alone. There is my brother and sister-in-law, but we have different rooms.

Interviewer: Do your parents stay with you?

Participant: My parents stay in our village.

Interviewer: You stay with your brother and his wife, but you have separate rooms. Interviewer: Do you eat together?

Participant: No, everything is separated. (Participant 8)

However, some of the interviewees were content to live with some other relatives.

Now I am with my aunt…they give me cooked food. Before I used to stay alone, did not eat on time, sometimes I felt lazy, did not want to cook food and ate dry foods. I eat, now I get to eat on time, before I did not eat on time, so my body became tired. (Participant 8)

Another line of reflection was gender roles in the families. For many participants, mothers were the ones who made sure that there was food for the family.

Family…umm….my father’s parents always dominated, hated my mother from the beginning. I do not care much about my father. I feel that if my mother is not there, I will not even get food to eat. (Participant 2)

Besides cooking, participants told that in an ideal situation mothers should take care of home.

I don’t think I am healthy … we eat junk foods, homemade foods are not eaten properly and mothers also don’t have the time for home so we have to eat junk food mostly. (FGD1, participant 3)

Additionally, participants in a manifest manner explained that they did not go hungry, but the family had to economize. There were no accounts about lack of food.

Participant: We do not have much money, but we have meals to eat on time and we also do not have [some food items].

Interviewer: What do you have and what do you not have?

Participant: Like we do not get to eat eggs, fruits. We have other things to eat.

Interviewer: What do you get then?

Participant: Meat once a week and mushrooms and yogurt for those who do not eat meat. And we get milk daily, vegetables also and then we get pickles almost every day. (Participant 6)

Through food-talk some of the participants described even serious domestic troubles, such as drinking problems.

In our house, it is not like in other houses. We have economic problems at home, my father does not give money, he spends all on alcohol, only mother earns for the family. But we eat good enough food, nutritious. (Participant 2)

Another respondent talked about domestic violence in the context of a meal.

My father had come home drunk. It was all good at first, we were eating our meal, he was discussing something with my mother outside and suddenly he started to beat her. (Participant 4)

Agency talk: weight loss

All adolescent girls in a manifest manner described a slender body as the ideal. None of the participants wanted to gain weight but all except one talked about losing weight.

I wish I could lose some weight. I am a little overweight, so I want to lose some. (Participant 9)

Some of them even had an exact idea which body parts needed to be trimmed.

Honestly speaking, I think I would have a body size I want if I can only lose some belly fat and fat on these sides. (hand gesture) (Participant 10)

Only one of the interviewees, the youngest girl, was happy with her body.

Interviewer: What do you think about your bodily appearance?

Participant: I think I am nice.

Interviewer: Like some people think they are fat, some think they are thin.

Participant: I used to feel like that before, but not now.

Interviewer: What did you use to feel before?

Participant: I thought I was fat, but now I see there are people fatter than me. (Participant 5)

Typically, participants mentioned reducing eating as an obvious strategy for weight loss. The interviewees described having an active role for keeping slim.

Participant: I am worried that I will get fat, so I avoid eating outside home.

Interviewer: And at home, do you avoid eating particular things, are you on a diet?

Participant: My mother used to serve me before and she used to serve large amount. Now I serve myself and eat only a little. (Participant 10)

Indirectly, concerns about body led to regulating also other walks of life besides eating. Reducing sleeping, especially daily naps, appeared to be a common habit in the accounts.

I sleep during the day. If we sleep more, we get fat and getting fatter is not good. (Participant 3)

When asked how they spent their days, the interviewees described other activities in the context of a regular meal pattern, which was also aimed at maintaining a slim body.

Participant: On a normal day, tea and biscuit or beaten rice after I get up, then we go to school. We have a break for lunch at 9:15 in school till 10, so we eat our lunch.

Interviewer: What do you have in your lunch?

Participant: Rice, pulses, curry. We then eat in our tiffin (light midday meal) and then again after we come back home and again meal at night. (Participant 1)

Lack of this patternfor example, eating cold meals and snacks or skipping meals was described as a failure, resulting in weight gain and eventually in ill health.

I eat on time, I do not eat between meals, I drink plenty of water….and what else …. I do not get ill tha(Participant 7)

Discussion: overarching nature of food-talk

The aim of this study was to examine how adolescent girls in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, construct and make meaning of their social context and identity through food-talk. Overall, the accounts extended far over food-as-nutrition and the interviews covered several aspects of identity construction. However, all the participants took up very similar issues in individual and FG interviews. Additionally, participants mostly talked about same themes as have been reported before. This allowed us to summarize the findings using the concept map based on previous literature. Furthermore, the limited number of themes suggests that far from being a marker of individual choice, food-talk is structured through cultural affiliation, as has been suggested before (Lupton Citation1996). However, there are inherent discrepancies included in the accounts and food choices appear vague and contradicting (Schaefer et al. Citation2016).

On the utilitarian versus hedonic theoretical axis, the endpoints in Nepali girls’ accounts were health and taste. Similarly, in Peru and in Italy, adolescents talked about the healthiness of home cooked foods (Banna et al. Citation2015; Guidetti, Cavazza, and Rita Graziani Citation2014). South-African adolescents considered locally grown foods, especially fruits and vegetables to be healthy (Sedibe et al. Citation2014). At the other end of the conceptual continuum, there were accounts on taste and pleasure, often contradicting the healthiness talk. Similar to Nepali accounts, centrality of food taste has often been reported for wealthy countries (Contento et al. Citation2006), but there is also some evidence for low- and middle-income countries. In Ecuador, “adolescents were enthusiastic when talking about the taste of sweet and fatty foods, while vegetables or salads were associated with unpleasant and negative taste” (Verstraeten et al. Citation2014). In Costa Rica and urban Cameroon adolescents reported preferring sweet foods (Dapi et al. Citation2007; Monge-Rojas et al. Citation2005). In Benin and Tanzania, adolescents chose their snacks primarily based on taste (Chauliac, Bricas, and Ategbo Citation1998; Muryn Citation2001). Another domain of hedonic talk is enjoyment that Nepali interviewees mention only when prompted. This is different from other contexts while, for example, in Saudi Arabia, adolescent girls told that they eat fast food primarily for enjoying the delicious taste, followed by convenience (ALFaris et al. Citation2015). In Botswana and England (Stead et al. Citation2011) adolescents enjoyed eating “junk food” at fast-food restaurants (Brown et al. Citation2015; Stead et al. Citation2011). Young women in Poland and in the United States associated food with pleasure and socializing (Lepkowska-White and Lucky Chang Citation2017). To summarize the utilitarian–hedonic axis, health and illness are complex concepts deriving influences from many sources, making healthy eating and taste “moving targets” (Calnan Citation1987).

On the collectivist versus agency axis Nepali participants talked about the need for family support, on one hand, and, on the other hand, their ability exercise agency through slim body. In food-related talk adolescents in Canada identified support from their families as critical to helping them get through life (Woodgate and Leach Citation2010). In Peru, family was consistently described as having a positive influence on food habits and skills (Banna et al. Citation2015). However, several Nepali interviewees talked also about negative issues related to family arrangementsfor example, drinking problems and domestic violence, to describe their own situation in relation to an ideal family. We have not seen similar accounts in other studies, this line of talk appears unique to Nepal.

A concept that has been used for capturing stakeholder voice is agency, defined as the capability of individuals to pursue their goals (Wells et al. Citation2021). Even in the more resource constrained environments, food is one way in which adolescents exercise some agency by choosing not to consume some foods (Neufeld et al. Citation2022). At the agency's end of the continuum, there were accounts, where the participants strongly emphasized maintaining slim body. Two previous articles have reported associations between normal weight Nepali adolescent girls’ aim to reduce weight (Mahat and Scoloveni Citation2001; Pokhrel, Acharya, and Adhikari Citation2015). For women in high-income countries, there is a wealth of literature attaching negative meanings to adiposity, whereas slenderness and restrained eating signify morality, control, self-discipline, and beauty (Reischer and Koo Citation2004; Woolhouse et al. Citation2012). Since 1980s slim-body ideal has spread globally via mass media (movies, television, and internet) (Brewis et al. Citation2011). For example, in West Bengal, normal-weight urban adolescent girls perceived themselves as overweight and even some underweight girls attempted to lose weight using unhealthy eating practices (Som and Mukhopadhyay n.d.). In Korea, nearly 40% of young women with normal body mass index perceived themselves as overweight or obese (Lee et al. Citation2017). In Peru, adolescent girls mentioned concerns about body image and desire to appear “thin” affected food choices (Banna et al. Citation2015). In conclusion, there is a paradox between agency as the ability to make everyday choices, to reflect one’s own actions and dependency of family that has been observed in other contexts (Mahat and Scoloveni Citation2001; Raby Citation2002).

One key finding of the study is that in Nepali adolescent girls’ food-talk same upper-level concepts as in interviews in other locations are present. Another key is that there were no references to undernutrition or food insecurity Nepali girls’ food talk. The interviewees emphasized that there is always some food available, and they worried more about eating too much than too little. However, they reported concerns about the quality of food. These findings resonate importantly with the global discussion on malnutrition.

The strength of the study is the qualitative design that allowed detailed analysis of the participants’ experiences, values, and meanings. However, the empirical findings of this study need to be understood in the particular context of Kathmandu valley. Therefore, based on the theoretical concepts drawn from earlier literature, it may be possible to apply these thematic categories in other similar settings.

Conclusion

Nepali adolescent girls’ food-talk extends beyond nutrition and covers issues related to everyday social context and identity of the participants. Interviews with adolescent girls in Kathmandu valley do not resonate with the literature on undernutrition prevalence, but rather with slim body ideal. These qualitative findings can be used to guide more appropriate nutrition messages for adolescent girls in public health strategies.

Abbreviations

| FG | = | Focus Group interview |

| LMICs | = | Low- and middle-income countries |

| GS | = | Government school |

| PS | = | Private school |

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council 2289/2016.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to the participants who took the time for the interviews. We also thank Dr Bhushan Guragain at the Center for Victims of Torture, Kathmandu, who helped with the practical arrangements of the study. Nutriset S.A. S., Malanay, France, generously provided partial funding for the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akseer, N., S. Al‐Gashm, S. Mehta, A. Mokdad, and Z. A. Bhutta. 2017. Global and regional trends in the nutritional status of young people: A critical and neglected age group: Global and regional trends in the nutritional status of young people. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1393 (1):3–20. doi:10.1111/nyas.13336.

- Alaszewski, A. 2006. Using diaries for social research. London: Sage.

- ALFaris, N. A., J. Z. Al-Tamimi, M. O. Al-Jobair, and N. M. Al-Shwaiyat. 2015. Trends of fast food consumption among adolescent and young adult Saudi girls living in Riyadh. Food & Nutrition Research 59 (1):26488. doi:10.3402/fnr.v59.26488.

- Antin, T. M. J., and G. Hunt. 2012. Food choice as a multidimensional experience. a qualitative study with young African American women. Appetite 58 (3):856–63. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.021.

- Azzopardi, P. S., S. J. C. Hearps, K. L. Francis, E. C. Kennedy, A. H. Mokdad, N. J. Kassebaum, S. Lim, C. M. S. Irvine, T. Vos, A. D. Brown, et al. 2019. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: Tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet. 393(10176):1101–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9.

- Banna, J. C., O. V. Buchthal, T. Delormier, H. M. Creed-Kanashiro, and M. E. Penny. 2015. Influences on eating: A qualitative study of adolescents in a Periurban Area in Lima, Peru. BMC Public Health 16 (1):40. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2724-7.

- Barthes, R. 1961. Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption. Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations 5.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The social construction of reality: A Treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

- Brewis, A. A., A. Wutich, A. Falletta-Cowden, and I. Rodriguez-Soto. 2011. Body norms and fat stigma in global perspective. Current Anthropology 52 (2):269–76. doi:10.1086/659309.

- Brown, C., S. Shaibu, S. Maruapula, L. Malete, and C. Compher. 2015. Perceptions and attitudes towards food choice in adolescents in Gaborone, Botswana. Appetite 95:29–35. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.018.

- Bryman, A., E. Bell, J. Leach, and J. Fields. 2022. Social research methods. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press Inc.

- Calnan, M. 1987. Health and illness: The lay perspective. London: Tavistock.

- Chauliac, M., N. Bricas, and E. Ategbo. 1998. L’alimentation hors du domicile des ecoliers de Cotonou (Benin). 8.

- Christian, P., and E. R. Smith. 2018. Adolescent Undernutrition: Global Burden, Physiology, and Nutritional Risks. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 72 (4):316–28. doi:10.1159/000488865.

- Contento, I. R., S. S. Williams, J. L. Michela, and A. B. Franklin. 2006. Understanding the food choice process of adolescents in the context of family and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health 38 (5):575–82. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.025.

- Cunningham, K., A. Pries, D. Erichsen, S. Manohar, and J. Nielsen. 2020. Adolescent girls’ nutritional status and knowledge, beliefs, practices, and access to services: An assessment to guide intervention design in Nepal. Current Developments in Nutrition 4 (7):11. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzaa094.

- Dapi, L. N., C. Omoloko, U. Janlert, L. Dahlgren, and L. Håglin. 2007. “I eat to be happy, to be strong, and to live.” perceptions of rural and urban adolescents in Cameroon, Africa. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39 (6):320–26. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.03.001.

- Elliott, C. 2014. Food as people: Teenagers’ perspectives on food personalities and implications for healthy eating. Social Science & Medicine 121:85–90. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.044.

- Graneheim, U. H., and B. Lundman. 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 24 (2):105–12. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Green, J., and N. Thorogood. 2009. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Guidetti, M., N. Cavazza, and A. Rita Graziani. 2014. Healthy at home, unhealthy outside: Food groups associated with family and friends and the potential impact on attitude and consumption. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 33 (4):343–64. doi:10.1521/jscp.2014.33.4.343.

- Hawkes, C., M. T. Ruel, L. Salm, B. Sinclair, and F. Branca. 2020. Double-duty actions: Seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. The Lancet 395 (10218):142–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32506-1.

- Hofstede, G., G. Hofstede, and M. Minkov 2010. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill.

- Jaacks, L. M., M. M. Slining, and B. M. Popkin. 2015. Recent trends in the prevalence of under- and overweight among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries: Adolescent under/overweight in LMICs. Pediatric Obesity 10 (6):428–35. doi:10.1111/ijpo.12000.

- Lee, A. C., N. Kozuki, S. Cousens, G. A. Stevens, H. Blencowe, M. F. Silveira, A. Sania, H. E. Rosen, C. Schmiegelow, L. S. Adair, et al. 2017. Estimates of burden and consequences of infants born small for gestational age in low and middle income countries with INTERGROWTH-21 st standard: Analysis of CHERG datasets. BMJ j3677. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3677.

- Lepkowska-White, E., and C. Lucky Chang. 2017. Meanings of food among Polish and American young women. Journal of East-West Business 23 (3):238–59. doi:10.1080/10669868.2017.1313351.

- Lo Monaco, G., and E. Bonetto. 2019. Social representations and culture in food studies. Food Research International 115:474–79. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.029.

- Lupton, D. 1996. Food, the body and the self. London: Sage.

- Madjdian, D. S., E. Talsma, N. Shrestha, K. Cunningham, M. Koelen, and L. Vaandrager. 2022. ‘Like a frog in a well’. A qualitative study of adolescent girls’ life aspirations in Western Nepal. Journal of Youth Studies 26 (6):705–29. doi:10.1080/13676261.2022.2038782.

- Mahat, G., and M. A. Scoloveni. 2001. “Factors influencing health practices of Nepalese adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 15 (5):251–55. doi:10.1016/S0891-5245(01)24751-8.

- Monge-Rojas, R., C. Garita, M. Sánchez, and L. Muñoz. 2005. Barriers to and motivators for healthful eating as perceived by Rural and Urban Costa Rican Adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 37 (1):33–40. doi:10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60257-1.

- Muryn, C. 2001. “Perceptions of food, health and body ideal in the context of urbanization and western influence: A study focusing on young women in Arusha, Tanzania. Norway: University of Oslo. University of Oslo, Institute of Nutrition Research.

- Neufeld, L. M., E. B. Andrade, A. Ballonoff Suleiman, M. Barker, T. Beal, L. S. Blum, K. M. Demmler, S. Dogra, P. Hardy-Johnson, A. Lahiri, et al. 2022. Food choice in transition: Adolescent autonomy, agency, and the food environment. The Lancet. 399(10320):185–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01687-1.

- Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative research and evaluation and methods. Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Patton, G. C., S. M. Sawyer, J. S. Santelli, D. A. Ross, R. Afifi, N. B. Allen, M. Arora, P. Azzopardi, W. Baldwin, C. Bonell, et al. 2016. Our future: A lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet. 387(10036):2423–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.

- Pokhrel, S., B. Acharya, and C. Adhikari. 2015. Nutritional status and body image dissatisfaction among adolescent girls in Kaski District. International Journal of Health Sciences & Research 5:462–68.

- Raby, R. C. 2002. A tangle of discourses: Girls negotiating adolescence. Journal of Youth Studies 5 (4):425–48. doi:10.1080/1367626022000030976.

- Rathi, N., L. Riddell, and A. Worsley. 2016. What influences urban Indian secondary school students’ food consumption? – a qualitative study. Appetite 105:790–97. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.018.

- Rathi, N., L. Riddell, and A. Worsley. 2018. Indian adolescents’ perceptions of the home food environment. BMC Public Health 18 (1):169. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5083-8.

- Reischer, E., and K. S. Koo. 2004. The body beautiful: Symbolism and agency in the social world. Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (1):297–317. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143754.

- Saldana, J. M. 2015. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Sarabia-Andreu, F., F. Sarabia-Sánchez, M. Parra-Meroño, and P. Moreno-Albaladejo 2020. A multifaceted explanation of the predisposition to buy organic food. Foods 9. doi:10.3390/foods9020197.

- Schaefer, S. E., C. Biltekoff, C. Thomas, and R. N. Rashedi. 2016. Healthy, Vague: Exploring health as a priority in food choice. Food, Culture, and Society 19 (2):227–50. doi:10.1080/15528014.2016.1178527.

- Sedibe, H. M., K. Kahn, K. Edin, T. Gitau, A. Ivarsson, and S. A. Norris. 2014. Qualitative study exploring healthy eating practices and physical activity among adolescent girls in Rural South Africa. BMC Pediatrics 14 (1):211. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-211.

- Shrestha, B. 2017. Anthropometrically determined undernutrition among the adolescent girls in Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu University Medical Journal 13 (3):224–29. doi:10.3126/kumj.v13i3.16812.

- Som, M., Mukhopadhyay, S. Mukhopadhyay, N. Som, and S. Mukhopadhyay. 2015. Body weight and body shape concerns and related behaviours among Indian urban adolescent girls. Public Health Nutrition 18 (6):632–46. doi:10.1017/S1368980014001451.

- Stead, M., L. McDermott, A. Marie MacKintosh, and A. Adamson. 2011. Why healthy eating is bad for young people’s health: Identity, belonging and food. Social Science & Medicine 72 (7):1131–39. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.029.

- Steptoe, A., T. M. Pollard, and J. Wardle. 1995. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite 25 (3):267–84. doi:10.1006/appe.1995.0061.

- United Nations. 2015a. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations Press.

- United Nations, B. 2015. Every woman, every child. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016-2030): Survive, thrive, transform. New York: United Nations Press.

- Verstraeten, R., K. Van Royen, A. Ochoa-Avilés, D. Penafiel, M. Holdsworth, S. Donoso, L. Maes, and P. Kolsteren. 2014. A conceptual framework for healthy eating behavior in Ecuadorian adolescents: A qualitative study” ed. Michel Botbol. PloS One 9 (1):e87183. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087183.

- Wells, J. C. K., A. A. Marphatia, G. Amable, M. Siervo, H. Friis, J. J. Miranda, H. H. Haisma, and D. Raubenheimer. 2021. The future of human malnutrition: Rebalancing agency for better nutritional health. Globalization and Health 17 (1):119. doi:10.1186/s12992-021-00767-4.

- Woodgate, R. L., and J. Leach. 2010. Youth’s perspectives on the determinants of health. Qualitative Health Research 20 (9):1173–82. doi:10.1177/1049732310370213.

- Woolhouse, M., K. Day, B. Rickett, and K. Milnes. 2012. ‘Cos Girls Aren’t supposed to eat like pigs are they?’ young women negotiating gendered discursive constructions of food and eating. Journal of Health Psychology 17 (1):46–56. doi:10.1177/1359105311406151.