ABSTRACT

The aim was to assess maternal feeding practices of children one to three years. A descriptive observational design was employed. The sample consisted of mothers-child dyads. A validated structured questionnaire was used. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. The nutrition status of the children at birth indicated 11.6% underweight as compared to the time of the study (7.2%), 7.9% were stunted increased to 38.0%, while wasting decreased from 11.4%–2.4%. Early cessation of breastfeeding and inappropriate complementary feeding practices were the factors influencing growth. The prevalence of underweight and wasting were low while stunting and overweight were high.

Introduction

Child growth is an important public health indicator for monitoring nutritional status within populations (Syed and Raafay Citation2010). Severe forms of malnutrition in childhood can lead to poor growth and development and have been recognized as one of the leading public health problems among children under five in developing countries (Amsalu and Tigabu Citation2008). The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF Citation2019) reported protein energy malnutrition (PEM) to be the most common nutritional problem among preschool children. A similar observation has been reported by Kalimbira, Chilima, and Mtimuni (Citation2006), who revealed that PEM in Malawi is one of the leading health problems. Chakraborty et al. (Citation2006) also reported PEM to be higher amongst children aged one to 36 months in India.

Globally, 23% of children under five are stunted, 14% are underweight and in developing countries, 7% are wasted (World Health Organization Citation2016). Some children suffer from more than one form of malnutrition, such as stunting and overweight or stunting and wasting. There are currently no joint global or regional estimates for these combined conditions (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Citation2020). The prevalence of malnutrition is still high in Africa with an estimated 30% of children being underweight and about 28% of children under five stunted (Kruger et al. Citation2012). The global trends are progressively improving: child stunting and underweight have reduced over the past two decades and the drop in poverty has been the key driver in this reduction (Ponce et al. Citation2018).

The relationship between maternal autonomy and child growth was assessed in a cross-sectional study of 422 mothers and their youngest children aged six to 24 months in the Bawku West District of Ghana (Saaka Citation2020). The study reported that healthcare autonomy better predicted child growth and dietary intake. Another qualitative study in West Africa explored socio-cultural practices and their influence on the feeding practices of 32 mothers and their children in Grand Popo, Benin (Lokossou et al. Citation2021). This study reported that mothers and children had monotonous diets with high consumption of vegetables and maize-based meals. Furthermore, food taboos, particularly during pregnancy, were revealed and those cultural beliefs were still followed by some mothers, and food rich in nutrients was pushed aside. Another study explored the association between mothers’ education and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) eight Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) core indicators in six countries in South Asia (Tariqujjaman et al. Citation2022). Their findings demonstrated a strong positive association between a mother’s education and IYCF indicators. A review in India (Sangra et al. Citation2017) revealed that the common enablers of IYCF were higher maternal socioeconomic status and more frequent antenatal care visits of more than three. Common barriers to IYCF practices were low socioeconomic status and less frequent antenatal care visits. The review showed that the factors associated with IYCF practices in India are largely modifiable and multi-factorial. These studies attest to the need to ensure that mothers/caregivers have adequate knowledge of child nutrition.

In the Limpopo province of South Africa, 23.4% of children aged one to three years were found to be stunted, 11% underweight and 5% wasted in Capricorn District (Mamabolo et al. Citation2005). Modjadji and Madiba (Citation2019) conducted a study in the same area in the Capricorn District and observed that 22% of children were stunted and 27% were underweight, while 27.4% of the mothers were overweight and 42.3% were obese. Mushaphi et al. (Citation2008) showed that stunting (18,9%), underweight (7%) and wasting (7%) were present in Vhembe District of Limpopo province. Phooko-Rabodiba et al. (Citation2019) similarly observed that there was a high (39.6%) prevalence of stunting among children under the age of 60 months, a medium prevalence of underweight, and a low prevalence of wasting in all children in Sekhukhune District of Limpopo province. They furthermore reported that most mothers/caregivers were overweight or obese. In terms of the socioeconomic status of the population, Sekhukhune is ranked lower than Vhembe and Capricorn Districts.

The South African Health Demographic Survey (SADHS) 2016 revealed that just over one-quarter (27%) of children under five were stunted nationally, 3% were wasted, while 6% were underweight and 13% were overweight (National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and ICF, Citation2019). While the Limpopo stunting prevalence was 22% (NDOH, Stats SA, SAMRC, ICF Citation2019). Modjadji, Molokwane, and Ukegbu (Citation2020) observed the prevalence of stunting (29%), underweight (13%) and thinness (6%) in the Northwest province of South Africa. Thus, the rates of malnutrition in Limpopo are comparable with other provinces and national levels. Undernourished children have lowered resistance to infection, poor wound healing, and poor clinical outcomes from disease or increased morbidity and mortality (Ibrahim et al. Citation2017). Malnourished children are more likely to die from diarrheal diseases and respiratory infections. On the other hand, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies have been associated with poor school performance and poor work capacity during adolescence and adulthood (Hoddinott et al. Citation2013). Chakona (Citation2020) conducted a study to determine maternal dietary diversity, breastfeeding and IYCF practices in five rural communities in South Africa. They observed that social circumstances including lack of income, dependence on food purchasing, young mothers’ feelings regarding breastfeeding and cultural beliefs were the major drivers of mothers’ eating habits, breastfeeding behavior and IYCF practices. Another study was conducted to describe the infant feeding practices of South African women living in Soweto and to understand from the mothers’ perspective what influences feeding practices (Wrottesley et al. Citation2021). They found that feeding practices were influenced by mothers’ beliefs that what babies eat is important for their health. In addition, family matriarchs were highly influential in mothers’ feeding practices, however, their advice often contradicted that of health professionals. Modjadji and Madiba (Citation2019) observed that having a younger mother and access to water and a refrigerator were protective against being underweight in Limpopo province. Furthermore, the nutrition knowledge and feeding practices of the mothers/caregivers were not satisfactory, as revealed in a study conducted in Limpopo province of South Africa (Motebejana, Nesamvuni, and Mbhenyane Citation2022).

A child’s ability to achieve standards in growth is determined by the adequacy of dietary intake which depends on infant and young child feeding practices, care practices and food security as well as exposure to disease (UNICEF Citation2011). Improving infant and young child feeding practices in children is critical to improved nutrition, health and development of children (Sangra et al. Citation2017). Adequate nutrition that includes exclusive breastfeeding for six months, appropriate complementary food and continued breastfeeding for at least two years and beyond are essential to improve the nutritional status of children and thus prevent child deaths((Motebejana, Nesamvuni, and Mbhenyane Citation2022). Infant and young child feeding practices affect the nutritional status of children and directly impact child survival according to Korday, Sharma, and Malik (Citation2018). Sinhababu et al. (Citation2010) found the proportion of appropriate feeding as per integrated management of neonatal and childhood illness protocol and WHO to be significantly low at 8.7% amongst children aged 12 to 23 months in India. Inappropriate feeding practices have been reported to be strongly associated with poor nutritional status in South Africa (Kleynhans, MacIntyre, and Albertse Citation2006). Furthermore, early introduction of solid feeds is associated with poor growth and risk of obesity, infections and allergies (Mamabolo et al. Citation2005).

Education for mothers and caregivers is essential to improve maternal knowledge and feeding practices. Mothers’ or caregivers’ feeding practices are influenced by knowledge, perception, cultural practices and attitudes according to the associated malnutrition found in rural Warda, Ethiopia with faulty feeding practices. They found that the intake of proteins and energy amongst children one to three years was 81% and 57% respectively.

Children one to three years of age are prime targets for intensified nutritional interventions (Labadarios et al. Citation2001). Furthermore, mothers/caregivers are targets for nutrition promotion and facilitation of healthy feeding practices. No statistics are indicating the prevalence of wasting and stunting in rural communities in Collins Chabane Municipality of South Africa. It is therefore important to investigate the current nutritional status of children one to three years in this rural region of the Limpopo Province. The study aimed to assess maternal feeding practices and nutritional status of children one to three years in Collins Chabane Municipality of Vhembe District, Limpopo Province in South Africa.

Methodology

Study design

The study employed a descriptive observational quantitative design. The study describes the growth and feeding practices of children one to three years old and the factors associated with growth and feeding practices. Furthermore, the relationship between growth patterns and feeding practices was determined.

Population and study area

The study population was mothers with children aged one to three years who use selected public primary health care clinics in Collins Chabane Municipality. At the time of the study, the area was served by 17 clinics and one health center serving 443 798 people of which 35.5% are under 16 years of age (Statistics South Africa Citation2011, Citation2023). The clinics were grouped in three clusters according to their geographic locations which are east, west and center. The health center was automatically included as the area consisted of one health center. Two clinics from each group were selected using the quota sampling method. A total of six clinics and one health center were then included in the study. The study was conducted in 2017.

Sampling design and procedure

The clinics were used as a sampling frame. Children were sampled using convenience sampling ensuring that all age groups are represented. All caregivers who gave concern for their children to be included in the study were included in the study. The exact number of children under three years attending the primary health care clinics at Collins Chabane Municipality was not readily available at the time due to demarcation politics that were going on in the Vhembe District municipality. A sample size of more than 100 subjects was targeted to allow for comparisons and statistical analysis (Anderson, Kelley, and Maxwell Citation2017; Maxwell, Kelley, and Rausch Citation2008). Thus, a total of 200 child-mother/caregiver dyads were envisaged in the study, with 50 dyads from the four age groups: 12 to 17 months, 18 to 23 months, 24 to 29 months and 30 to 36 months.

Data collection and procedure

Data was collected by the principal investigator who is a registered dietitian. Mothers/caregivers with children between one to three years were recruited from the Well Baby clinic and requested to participate in the study. Children and their mothers who satisfied the inclusion criteria of one to three years were selected. The procedure was explained by the researchers in Xitsonga language and caregivers who agreed to participate signed a consent form. Information on feeding practices was collected by using a food frequency questionnaire and a diet history. The anthropometric data measured and interviews were all done and recorded on the same day by the principal investigator. A structured interviewer-led questionnaire was adapted from that used in the preceding study (Mushaphi et al. Citation2008) and was translated into Xitsonga (the local language). The questionnaire had four sections which consisted of information on anthropometry and medical data, demographic data, and feeding practices and food frequency. General questions and a food frequency questionnaire were used to estimate children’s feeding practices and disease status. The translated questionnaire was tested on five mothers/caregivers at a hospital where the principal investigator is based.

Each clinic was visited three times, first for introductions and twice for data collection. Data was collected over four weeks. The clinic management allocated one of the consultation rooms for use. The principal investigator interviewed the participants using the local language. The whole process from recruitment, consenting process, measurements and interview took approximately one and a half hours.

Anthropometric measurements

The birth weight of the children as recorded on the road to health charts was used. The Road to Health Chart in South Africa is a booklet that is created for children at birth to record medical history, health, immunizations, growth and development from birth to age five (Win and Mlambo Citation2020). Weight, height and MUAC for children were measured following the standard protocol of the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) (Silva and Vieira Citation2020). The weight and height of the mothers/caregivers were also measured using the standard protocols. The weight and height of the caregivers were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) and to estimate the mothers’ nutritional status. The mothers’ nutritional status was measured to control for bias introduced by confounders/modifiers.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 25.0. Anthropometric z-scores were analyzed using WHO Anthro 1.0.4. Descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized to analyze data according to age groupings. Weight-for-age, height-for-age and weight-for-height were analyzed using z-scores (31) (WHO Citation2006). A child is malnourished if their z-score is < −2, while severe malnutrition is indicated at a z-score of < −3 (28) (WHO Citation2006). Arm circumferences were analyzed using the National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS) tables (32).

Descriptive statistics that were used are the mean standard deviation, range and percentiles. The chi-square was used to compare feeding practices, anthropometric measurements and socio-economic factors. The t-test was used to determine the significance of the mean weight, length, and arm circumference and the difference between the mean standard references by age group. The results are significant if the p-value is < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Approval was sought from the higher degrees and ethics committee of the University of Venda. Permission to use the clinics was requested from the Department of Health at the Provincial Office and from the Primary Healthcare Manager. Consent forms were signed by caregivers to permit participation of themselves and their children. Data was treated with confidentiality and a code was assigned to the mother-child dyad. Children who were found to be at risk of malnutrition were referred for treatment and/or nutrition counseling.

Results

The study comprised 141 children and 141 mothers/caregivers from six local clinics and one health center. This was 70.5% of the envisaged sample. The age group above two years did not frequent the primary health facilities. The age of the children ranged from 12 to 36 months with the majority of the children (65.2%) below the age of 24 months while 34.6% were between the ages of 24 to 36 months. Regarding children’s gender, more than half (55.7%) were male and 44.3% were female. See .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (n = 141).

Most mothers (85.1%) were of child-bearing age as they were between the ages of 18 and 35 years. More than half of the mothers/caregivers (56%) were married, and 68.2% were literate as they had secondary education (grades 8–12). Most (81.1%) children were supported by their parents, with 45% of the households dependent on social grants whilst 16.2% depended on family members working in government institutions. Nearly two-thirds of households (61.7%) had an income of less than 1000.00 ZAR (55 USD) (see ).

Health profile of the children

About one-third (36.2%) of the children were reported to suffer from respiratory infections, diarrhea (13.5%), diarrhea combined with respiratory infections (22.7%), diarrhea and vomiting (22.7%), and vomiting (2.8%) while 2.1% did not have any condition.

Child growth patterns

Nutritional status of the children at birth indicated that more than half of the children were born with normal weight (57.6%), mild underweight (18.7%), stunting (7.9%), underweight (5.8%) and severely underweight (5.8%), while children who were overweight were 12.1%.

Weight-for-age at the time of study indicates that only 1.4% of the children were severely underweight. This shows that underweight has improved from 5.8% at birth to 1.4% as the children were growing. Although 44.3% of the children had normal weight at the time of study, 26.6% of the children showed a possible faltering growth problem.

Regarding stunting prevalence, detailed analysis revealed that 2.9% were severely stunted and 5.0% were stunted at birth. At the time of the study, severe stunting increased from 2.9% at birth to 20.1% and stunting increased from 5.0%–17.9%.

The prevalence of wasting was 5.7% and severe wasting (5.7%) at birth. The possible risk of overweight was 12.9% and overweight 9.3%. Analysis revealed that at the time of the study, the prevalence of severe wasting was 1.5% and wasting 0.7%. The risk of being overweight was 26.6%, overweight 15.8% and obesity 6.5%. Wasting decreased by 9.2%, obesity increased by 6.4%. overweight increased by 6.5%, and the risk of overweight increased by 6.5% from birth to the time of the study. Mid-upper arm circumference of the children indicated that most of the children were normal. See .

Table 2. An illustration of the nutritional status of children one to three years at birth and during the study (n = 141).

Feeding practices of mothers/caregivers

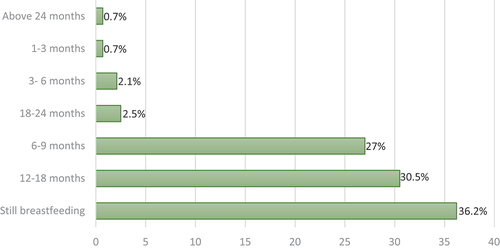

Most of the children were fed by their mothers (58.2%) with 31.9% self-feeding. Regarding the duration of child breastfeeding, 36.2% of the children were still breastfed at the time of the study with 3.2% of mothers breastfeeding beyond 18 months. Most (57.5%) mothers breastfed their children between six to 18 months (see ).

Dietary patterns of children

Concerning milk consumption, most of the children (71.6%) were not fed any milk whilst few were given pasteurized cow’s milk (15.6%). Snacks fed to babies were also assessed and findings revealed that dried chips, biscuits, sweets and sweetened drinks were most fed to the children (45.4%). Concerning the type of salt used in the household, most of the households (59%) were using iodated salt and 33.3% non-iodated salt.

Food frequency was assessed by asking mothers/caregivers how often they gave certain food to their children. As shown in , food groups mostly consumed by the children were cereals, fruits and vegetables. Detailed analysis revealed that the top ten foods mothers/caregivers gave to the children daily were stiff porridge, soft porridge, brown bread, peanut butter, fat cakes, sugar-sweetened beverages and snacks, margarines, fruit and fruit juices. Other foods given at least once or twice a week included spinach, indigenous vegetables mixed with peanuts, eggs, potatoes, cabbage, beans, fish, indigenous vegetables, soya mince soup, rice, fruits, chicken and yogurt. Traditional foods were amongst the least foods fed to the children. This pattern shows that maize is utilized daily while the accompaniment is variable. The variety seems limited and influences the children’s eating habits.

Table 3. The food consumption of children one to three years at birth and during the study in Vhembe District (n = 141).

Relationship among socioeconomic factors, feeding practices and nutritional status of children

below indicates wasting was positively influenced by the age of the mother, toilet facility and the source of fuel for cooking, and negatively influenced by the maternal level of education (p < .05). Stunting was not significantly associated with any socioeconomic variable in this study (p > .05). Underweight was positively influenced by the feeder of the child and the availability of storage facilities in the households (p < .05). The birth weight of the child has a positive correlation with the child’s household source of drinking water and the type of toilet facility used by the household. There was a positive influence of the household income and the availability of food in the household on MUAC (p < .05).

Table 4. Shows the association between socioeconomic factors of the nutritional status of children (Pearson’s correlation).

WAZ: weight-for-age; BAZ: body mass index for age

Wasting was negatively influenced by feeding soft porridge and fruit juice, while positively influenced by stiff porridge and margarine. Stunting was negatively influenced by feeding bread and fruits. Underweight was negatively influenced by feeding bread, fruits and cold drinks, sweets and biscuits. Birth weight z-scores were negatively influenced by feeding soft porridge and fat cakes and positively influenced by stiff porridge, potatoes and margarine ().

Table 5. The relationship between growth and feeding practices among children one to three years in Limpopo, South Africa (Pearson’s correlation, p < .05).

Multiple regression analysis using four models showed that age was the only variable associated with feeding practices. The older the mother, the better the feeding practices. See below.

Table 6. Multiple regression using maternal age and BMI and MUAC and feeding practices.

Health status of the mothers

Regarding the BMI of mothers, 62.5% had normal BMI (18.6–25 kg/m2), 18.1% were overweight with BMI above 26–29 kg/m2, 13.3% were obese (30–47 kg/m2) while few mothers (5.7%) were underweight (BMI: 16–18 kg/m2).

Discussion

The study revealed the prevalence of stunting with low levels of wasting and underweight and an increase in overweight rates. The findings showed that mothers/caregivers fed children a high starchy diet with a limited variety of foods. Associations between growth patterns and feeding practices were weak.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Findings indicated that most children in this study were from households with low income as social grants and income from domestic work contributed as the main source of support for most families. The findings are consistent with preceding findings which reported that 66% of South African children live in households that have less than 1200 ZAR (66 USD) per month (Labadarios et al. Citation2005; Phooko-Rabodiba et al. Citation2019). Low income and unstimulating household environments contribute to deficits in children’s development and health, and productivity in adulthood (Black et al. Citation2013). This can be explained by a limited intake of food by the poorest due to shortage and scarcity.

Regarding the BMI of mothers, about two-thirds of the mothers had normal weight and there were low rates of overweight and obesity. This study contradicts the findings of a previous study conducted in both the urban and rural southern Free State of South Africa which reported that one-third of the rural mothers/caregivers were normal/underweight with the majority being overweight or obese (Tydeman-Edwards, van Rooyen, and Walsh Citation2018). Kaldenbach et al., found that a double burden of malnutrition was prevalent in KwaZulu-Natal, with most mothers being overweight or obese, and many children developing stunting in the early months of life. The increasing rates of overweight and obesity in South Africa pose serious challenges for non-communicable diseases. However, there seem to be regional variations in the prevalence. One of the weaknesses of this study was the lack of comparison of mothers’ BMI and children’s z-scores. The double burden of malnutrition in the same household was thus not determined. Akokuwebe and Idemudia (Citation2022) conducted a cross-sectional survey in Nigeria and South Africa. Their multilevel analysis revealed urban-rural variations of body weights and individual-level factors among women of childbearing age.

Health profile of the children

Despite the high attendance rate of six-week immunization services in South African facilities, potential missed opportunities for early infant diagnosis are still very high (Woldesenbet et al. Citation2015). Inadequate communication between antenatal, delivery, and postnatal facilities and poor information systems have been reported as important barriers to the continuity of postnatal services in developing countries (Horwood et al. Citation2010; Reithinger et al. Citation2007).

Health problems experienced by the children during the period of the survey included respiratory infections such as coughing, diarrhea and vomiting. The Committee on Morbidity and Mortality in children under five years reported diarrhea, lower respiratory tract infections, neonatal conditions with HIV/AIDS and malnutrition contributing as primary and underlying major causes of child mortality (Victora et al. Citation2008).

Growth patterns of children

The z-scores indicated that one-tenth of children were underweight at birth compared to less than one-tenth at the time of study. This might imply that underweight decreases with age as some of the underweight children can catch up with growth. Similar findings have been reported by Mamabolo et al., (Citation2005) where it was revealed that the prevalence of underweight children under three years is 9.0% in rural Limpopo province. The SADHS of 2016 also reported a low underweight of 6% (NDOH, Stats SA, SAMRC AND ICF, Citation2016). Child feeders and the availability of storage facilities in the households were the major determinants of underweight in this study.

The present finding revealed that less than one-tenth of the children were stunted at birth and this increased five times during the time of study. The implication is that an increased number of children might experience impaired neurocognitive development, perform poorly at school and reduced productivity in later life (World Health Organization Citation2014). This prevalence was lower when compared to a study conducted earlier which reported the prevalence of stunting of almost half among children one to three years in the same geographic area (Mamabolo et al. Citation2005). The findings in this study are still higher than the stunting trends reported in the 2016 SADHS in Limpopo province of 22% (NDOH, Stats SA, SAMRC AND ICF Citation2016). Furthermore, the prevalence is also higher than the national stunting rate of 27.0% for children under five years (Statistics South Africa Citation2016).

The prevalence of wasting was one-tenth at birth and decreased to 2% at the time of the study. This infers that fewer children were too thin for their height. Wasted children have weakened immunity, are susceptible to long-term developmental delays, and face an increased risk of death, especially when wasting is severe (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Citation2020). The study findings are in line with the national prevalence of 3% (Statistics South Africa Citation2016). A consistent association in low-income countries has been demonstrated between maternal age, maternal level of education, sanitation and wasting (Das et al. Citation2021; Melese Citation2014; Makoka and Masibo Citation2015). This study showed no associations between wasting and maternal age, level of education and sanitation.

The prevalence of overweight at the time of the study was just above 20% from just below 10% at birth. Thus, the prevalence of overweight increases as they grow older. Jebeile et al. (Citation2022) assert that the development and continuance of obesity are explained by a bio-socioecological framework, whereby biological predisposition, socioeconomic, and environmental factors interact together to promote the deposition and proliferation of adipose tissue. The prevalence of overweight in this current study is slightly lower when compared to the 24% prevalence of overweight across under-five-year-old children in Africa (World Health Organization Citation2022).

MUAC was less than 2%, signifying the rate of acute malnutrition was low among the children. These results are in contrast with findings in some low-income settings in Africa that show a higher prevalence of MUAC in children (Engebretsen et al. Citation2008; Kinyoki et al. Citation2015). There was a positive influence of the household income and the availability of food in the household on MUAC (p < .05) in this study. Income results in higher purchasing power and a household’s ability to afford diverse foods (Nascimento et al. Citation2021).

Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices

There seems to be early cessation of breastfeeding amongst the mothers in this study group as results showed almost all the children were initially breastfed but weaned off by six to 18 months. The SADHS 2016 reported the median breastfeeding period as 13.3 months in rural areas of South Africa (NDOH, Stats SA, SAMRC AND ICF Citation2016). Thus, this study was comparable to the national trends. Infant feeding practices among mothers seem not to follow the WHO recommendation or IYCF of continued breastfeeding for two years (UNICEF Citation2011). Early cessation of breastfeeding in favor of commercial breastmilk substitutes, the introduction of liquids such as juices and poorly timed complementary feeds of poor quality seem to be common (Cai, Wardlaw, and Brown Citation2012). González-Cossío et al. (Citation2006) study found the breastfeeding rates of mothers in Mexico to be at 92.3% at initiation but they declined at one year to less than 40% of the children still breastfed. Breastmilk is a natural resource that has a major impact on a child’s health, growth and development and is recommended for at least two years of a child’s life. Breastmilk provides half or more of a child’s energy needs between six and 12 months and one-third of energy needs between 12 to 24 months (Dewey Citation2005). Breastmilk is also a critical source of energy and nutrients during illness and reduces mortality among children who are malnourished (World Health Ogarnization Citation2013).

Linear growth retardation which leads to stunting often begins in utero but is most marked during the vulnerable period of complementary feeding, the transition from a diet of breastmilk to family food (Victora et al. Citation2008). Continued breastfeeding and complementary feeds usually meet protein requirements but energy intakes may be low, and diets are almost low in critical micronutrients (Dhami et al. Citation2021; Victora et al. Citation2008). Information on child feeding practices in this study revealed that a low variety of locally available foods are fed to children but included mostly starchy foods. Foods mostly used were porridge, bread, protein foods like chicken, eggs, fish and soya mince soup, fruits and vegetables, especially traditional green leafy vegetables, cabbage and spinach.

More than half of the children were no longer breastfed and other non-human milk was not commonly fed to the children. In this study, only just over half were less than two years of age and expected to be still breastfeeding. Children who are not breastfed should be given one to two cups of milk and one to two extra meals per day (WHO Citation2001). The implications of not giving children milk will be a lack of calcium and poor bone development. Milk also provides energy, protein, and vitamins A, B and D. These nutrients are required for bone and teeth development, growth, vision, immune system and heart function. Poor milk consumption by children could lead to growth retardation (WHO Citation2001). In addition, dried chips, sweets, biscuits and sweet drinks were the most common snacks fed to children. Similar findings were reported in another study which found that children are given milk until around the age of one year and thereafter milk falls off the children’s diet and sweets and crisps are commonly fed to children at three years (Mamabolo et al., Citation2005). Age of mother was the only variable shown to influence feeding practices. Dhami et al., (Citation2019) showed that older mothers (≥25 years) in the Northern region of India were more likely to have children who met minimum adequate diet compared with younger mothers (<25 years). Quamme and Iversen (Citation2022) showed no significant link between maternal age and stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, Nankinga et al. (Citation2019) reported that maternal age of 35–49 had lower odds of stunting compared with children born to younger mothers aged 15–24 years (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56–0.86) in a study conducted in Ghana. Other studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have linked older age to better feeding practices potentially due to better nutrition knowledge, parenting experience and higher incomes (Adedokun and Yaya Citation2021; Masuke et al. Citation2021; Tesema et al. Citation2021).

This study was limited to children one to three years old attending the public health institutions in Collins Chabane Municipality because they were the accessible population. In addition, the sampling frame of clinics was probably a limitation. It is possible that some children above two years were not attending the Well Baby clinics as it often happens after the immunizations are completed. The authors also acknowledge that child growth is not only influenced by maternal feeding practices and the other confounders were not controlled in this study.

Conclusion

The prevalence of underweight, wasting and MUAC were low while stunting and overweight were high among children one to three years at the time of the study when compared to the provincial and national rates. The high stunting and overweight among this age group should be targeted for intervention. Information on child feeding practices indicated that mostly starchy foods with limited non-human milk, fruits and vegetables were fed to children. Inappropriate breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices were the major determinants of poor growth in children. This necessitates an urgent call for interventions to target mother/caregiver nutrition education and empowerment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the mothers and children who participated in this study for their cooperation and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available from the corresponding author [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adedokun, S. T., and S. Yaya. 2021. Factors associated with adverse nutritional status of children in sub‐Saharan Africa: Evidence from the demographic and health surveys from 31 countries. Maternal & Child Nutrition 17 (3):e13198. doi:10.1111/mcn.13198.

- Akokuwebe, M. E., and E. S. Idemudia. 2022, Jan. Multilevel analysis of urban–rural variations of body weights and individual-level factors among women of childbearing age in Nigeria and South Africa: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (1):125. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010125.

- Amsalu, S., and Z. Tigabu. 2008. Risk factors for ever acute malnutrition in children under the age of five: A case-control study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 22 (1):21–25. doi:10.4314/ejhd.v22i1.10058.

- Anderson, S. F., K. Kelley, and S. E. Maxwell. 2017. Sample-size planning for more accurate statistical power: A method adjusting sample effect sizes for publication bias and uncertainty. Psychological Science 28 (11):1547–62. doi:10.1177/0956797617723724.

- Black, R. E., C. G. Victora, S. P. Walker, Z. A. Bhutta, P. Christian, M. De Onis, M. Ezzati, S. Grantham-McGregor, J. Katz, R. Martorell, et al. 2013. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382 (9890):427–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

- Cai, X., T. Wardlaw, and D. W. Brown. 2012. Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding. International Breastfeeding Journal 7 (1). doi:10.1186/1746-4358-7-12.

- Chakona, G. 2020. Social circumstances and cultural beliefs influence maternal nutrition, breastfeeding and child feeding practices in South Africa. Nutrition Journal 19 (1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12937-020-00566-4.

- Chakraborty, S., S. B. Gupta, B. Chaturvedi, and S. K. Chakraborty. 2006. A study of protein energy malnutrition (PEM) in children (0 to 6 year) in a rural population of Jhansi district (UP). Indian Journal of Community Medicine, Oct 1, 31 (4):291.

- Das, S., S. M. Fahim, M. A. Alam, M. Mahfuz, P. Bessong, E. Mduma, M. Kosek, S. K. Shrestha, and T. Ahmed. 2021. Not water, sanitation and hygiene practice, but timing of stunting is associated with recovery from stunting at 24 months: Results from a multi-country birth cohort study. Public Health Nutrition 24 (6):1428–37. doi:10.1017/S136898002000004X.

- Das, S., S. M. Fahim, M. A. Alam, M. Mahfuz, P. Bessong, E. Mduma, M. Kosek, S. K. Shrestha, and T. Ahmed. 2021. Not water, sanitation and hygiene practice, but timing of stunting is associated with recovery from stunting at 24 months: Results from a multi-country birth cohort study. Public Health Nutrition 24 (6):1428–37.

- de Onis, M., M. Blössner, and E. Borghi. 2012. Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990–2020. Public Health Nutrition 15 (1):142–48. doi:10.1017/S1368980011001315.

- Dewey, K. 2005. Guiding principles for feeding non-breastfed children 6–24 months of age. Children 40. Accessed May 16, 2020. http://www.who.int/child-adolescent-health.

- Dhami, M. V., F. A. Ogbo, B. J. Akombi-Inyang, R. Torome, and K. E. Agho. 2021. Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Understanding the enablers and barriers to appropriate infants and young child feeding practices in India: A systematic review. Nutrients 13, Mar 2, (3):825. doi:10.3390/nu13030825.

- Dhami, M. V., F. A. Ogbo, U. L. Osuagwu, and K. E. Agho. 2019. Prevalence and factors associated with complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in India: A regional analysis. BMC Public Health 19 (1):1–16. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7360-6.

- Engebretsen, I. M. S., T. Tylleskär, C. K. Wamani, and J. K. Tumwine. 2008. Determinants of infant growth in Eastern Uganda: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 8 (1). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-418.

- González-Cossío, T., J. Rivera-Dommarco, H. Moreno- Macías, F. Monterrubio, and J. Sepúlveda. 2006. Poor compliance with appropriate feeding practices in children under 2 y in Mexico. The Journal of Nutrition 136 (11):2928–33. doi:10.1093/jn/136.11.2928.

- Hoddinott, J., J. R. Behrman, J. A. Maluccio, P. Melgar, A. R. Quisumbing, M. Ramirez-Zea, A. D. Stein, K. M. Yount, and R. Martorell. 2013. Adult consequences of growth failure in early childhood. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 98 (5):1170–78. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.064584.

- Horwood, C., L. Haskins, K. Vermaak, S. Phakathi, R. Subbaye, and T. Doherty. 2010. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programme in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: An evaluation of PMTCT implementation and integration into routine maternal, child and women’s health services. Tropical Medicine and International Health 15 (9):992–99. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02576.x.

- Ibrahim, M. K., M. Zambruni, C. L. Melby, and P. C. Melby. 2017. Impact of childhood malnutrition on host defense and infection. Clinical microbiology reviews 30 (4):919–71. American Society for Microbiology. doi:10.1128/CMR.00119-16.

- Jebeile, H., A. S. Kelly, G. O’Malley, and L. A. Baur. 2022. Obesity in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, May 1; 10 (5):351–65. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00047-X.

- Kalimbira, A. A., D. D. Chilima, and B. M. Mtimuni. 2006. Disparities in the prevalence of child undernutrition in Malawi – a cross-sectional perspective. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 19 (4):146–51. doi:10.1080/16070658.2006.11734110.

- Kinyoki, D. K., G. M. Berkley, N. B. Moloney, N. B. Kandala, and A. M. Noor. 2015. Predictors of the risk of malnutrition among children under the age of 5 years in Somalia. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001913.

- Kleynhans, I. C., U. E. MacIntyre, and E. C. Albertse. 2006. Stunting among young black children and the socio-economic and health status of their mothers/caregivers in poor areas of rural Limpopo and urban Gauteng – the NutriGro study. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 19 (4):163–72. doi:10.1080/16070658.2006.11734112.

- Korday, C. S., R. K. Sharma, and S. Malik. 2018. Assessment of nutritional status in children using WHO IYCF indicators: An institution-based study. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 5 (3):783. doi:10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20181412.

- Kruger, H. S., N. P. Steyn, E. C. Swart, E. M. Maunder, J. H. Nel, L. Moeng, and D. Labadarios. 2012. Overweight among children decreased, but obesity prevalence remained high among women in South Africa, 1999–2005. Public Health Nutrition 15 (4):594–99. doi:10.1017/S136898001100262X.

- Labadarios, D. N. S., E. Maunder, U. MacIntyre, G. Gericke, R. Swart, J. Huskisson, A. Dannhauser, H. H. Vorster, and A. E. Nesamvuni. 2005. The national food consumption survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999. Public Health Nutrition 8 (5):533–43. doi:10.1079/phn2005816.

- Labadarios, D., N. P. Steyn, E. Maunder, U. MacIntyre, R. Swart, G. Gericke, J. Huskisson, A. Dannhauser, H. H. Vorster, and A. E. Nesamvuni. 2001. The national food consumption survey (NFCS)-children aged 1–9 years, South Africa, 1999. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 14 (2):98.

- Lokossou, Y. U., A. B. Tambe, C. Azandjèmè, and X. Mbhenyane. 2021. Socio-cultural beliefs influence feeding practices of mothers and their children in Grand Popo, Benin. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, Dec; 40 (1):1–2. doi:10.1186/s41043-021-00258-7.

- Makoka, D., and P. K. Masibo. 2015. Is there a threshold level of maternal education sufficient to reduce child undernutrition? Evidence from Malawi, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. BMC Pediatrics 15 (1):96. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0406-8.

- Mamabolo, R. L., M. Alberts, N. P. Steyn, H. A. Delemarre-van de Waal, and N. S. Levitt. 2005. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and overweight in 3-year-old black South African children residing in the central region of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Public Health Nutrition 8 (5):501–08. doi:10.1079/phn2005786.

- Masuke, R., S. E. Msuya, J. M. Mahande, E. J. Diarz, B. Stray-Pedersen, O. Jahanpour, M. Mgongo, and M. A. Cardoso. 2021. Effect of inappropriate complementary feeding practices on the nutritional status of children aged 6–24 months in urban Moshi, Northern Tanzania: Cohort study. Public Library of Science ONE 16 (5):e0250562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250562.

- Maxwell, S. E., K. Kelley, and J. R. Rausch. 2008. Sample size planning for statistical power and accuracy in parameter estimation. Annual Review of Psychology 59 (1):537–63. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093735.

- Melese, Y. B. 2014. Prevalence of malnutrition and associated factors among children age 6–59 months at Lalibela Town Administration, North WolloZone, Anrs, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Nutritional Disorders & Therapy 4 (132):2161–509. doi:10.4172/2161-0509.1000132.

- Modjadji, P., and S. Madiba. 2019. Childhood undernutrition and its predictors in a rural health and demographic surveillance system site in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (17):3021. doi:10.3390/ijerph16173021.

- Modjadji, P., D. Molokwane, and P. O. Ukegbu. 2020. Dietary diversity and nutritional status of preschool children in Northwest Province, South Africa: A cross sectional study. Children 7 (10):174. doi:10.3390/children7100174.

- Motebejana, T. T., C. N. Nesamvuni, and X. Mbhenyane. 2022. Nutrition knowledge of caregiver’s influences feeding practices and nutritional status of children 2 to 5 years old in Sekhukhune District, South Africa. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, Jan; 32 (1):103.

- Mushaphi, L. F., X. G. Mbhenyane, L. B. Khoza, and A. K. Amey. 2008. Infant-feeding practices of mothers and the nutritional status of infants in the Vhembe District of Limpopo Province. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 21 (2):36–41. doi:10.1080/16070658.2008.11734159.

- Nankinga, O., B. Kwagala, E. J. Walakira, and K. Navaneetham. 2019. Maternal employment and child nutritional status in Uganda. Public Library of Science ONE 14 (12):e0226720. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226720.

- Nascimento, V. G., T. C. Machado, C. J. Bertoli, L. C. de Abreu, V. E. Valenti, and C. Leone. 2021. Evaluation of mid-upper arm circumference in pre-school children: Comparison between NCHS/CDC-2000 and WHO-2006 references. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, Jun 1; 57 (3):208–12. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmq076.

- National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and ICF. 2019. South Africa demographic and health survey 2016. Pretoria, South Africa, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC, and ICF.

- Phooko-Rabodiba, D. A., B. A. Tambe, C. N. Nesamvuni, and X. G. Mbhenyane. 2019. Socioeconomic determinants influencing nutritional status of children in Sekhukhune District of Limpopo Province in South Africa. Journal of Nutrition and Health 5 (1):7. Accessed May 11 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335292846.

- Ponce, N., R. Shimkhada, A. Raub, A. Daoud, A. Nandi, L. Richter, and J. Heymann. 2018. The association of minimum wage change on child nutritional status in LMICs: A quasi-experimental multi-country study. Global Public Health 13 (9):1307–21. doi:10.1080/17441692.2017.1359327.

- Quamme, S. H., and P. O. Iversen. 2022. Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa and its risk factors. Clinical Nutrition Open Science 42:49–61. doi:10.1016/j.nutos.2022.01.009.

- Reithinger, R., K. Megazzini, S. J. Durako, D. R. Harris, and S. H. Vermund. 2007. Monitoring and evaluation of programmes to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV in africa. British Medical Journal 334 (7604):1143–46. doi:10.1136/bmj.39211.527488.94.

- Saaka, M. 2020. Women’s decision-making autonomy and its relationship with child feeding practices and postnatal growth. Journal of Nutritional Science 9:e38. doi:10.1017/jns.2020.30.

- Sangra, S., D. Kumar, D. Dewan, and A. Sangra. 2017. Reporting of core and optional indicators of infant and young child feeding practices using standardized the WHO formats from a rural population of Jammu region Reporting of core and optional indicators of infant and young child feeding practices using standardized WHO formats from a rural population of Jammu region. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 6 (11). doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2017.0824721092017.

- Silva, V. S. D., and M. F. S. Vieira. 2020. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) Global: International accreditation scheme of the competent anthropometrist. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano 22:22. doi:10.1590/1980-0037.2020v22e70517.

- Sinhababu, A., D. K. Mukhopadhyay, T. K. Panja, A. B. Saren, N. K. Mandal, and A. B. Biswas. 2010. Infant-and young child-feeding practices in Bankura district, West Bengal, India. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 28 (3):294. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v28i3.5559.

- Statistics South Africa. 2011. Census 2011. Department of Statistics. Republic of South Africa. Pretoria. https://census.statssa.gov.za/assets/documents/.

- Statistics South Africa. 2016. Key indicators report 2016, department of statistics. Republic of South Africa. Pretoria. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0215.

- Statistics South Africa. 2023. Census 2022. Department of Statistics. Republic of South Africa. Pretoria. https://census.statssa.gov.za/assets/documents/…PDF file

- Syed, F. H., and S. Raafay. 2010. Prevalence and risk factors for stunting among children under 5-year community-based study from Jhangara town, Dadu Sindh. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 60:41.

- Tariqujjaman, M., M. M. Hasan, M. Mahfuz, M. Hossain, and T. Ahmed. 2022. Association between mother’s education and infant and young child feeding practices in South Asia. Nutrients, Apr 5; 14 (7):1514. doi:10.3390/nu14071514.

- Tesema, G. A., M. G. Worku, Z. T. Tessema, A. B. Teshale, A. Z. Alem, Y. Yeshaw, T. S. Alamneh, A. M. Liyew, and F. T. Spradley. 2021. Prevalence and determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. Public Library of Science ONE 16 (4):e0249978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249978.

- Tydeman-Edwards, R., F. C. van Rooyen, and C. M. Walsh. 2018. Obesity, undernutrition and the double burden of malnutrition in the urban and rural southern Free State, South Africa. Heliyon Elsevier Ltd 4 (12):e00983. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00983.

- UNICEF. 2011. Programming Guide Infant and Young Child Feeding, Unicef.Org. New York. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.unicef.org/aids/files/hiv_IYCF_programmingguide_2011.pdf.

- UNICEF, WHO and World Bank. 2020. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2020 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Geneva: WHO 24 (2):1–16. Accessed May 2, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331621/9789240003576-eng.pdf.

- United Nations Children’s Fund. 2019. Malnutrition. Accessed September 24, 2019, UNICEF: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/.

- Victora, C. G., L. Adair, C. Fall, P. C. Hallal, R. Martorell, L. Richter, and H. S. Sachdev. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 371 (9609):340–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4.

- Win, T., and M. G. Mlambo. 2020. Road-to-Health Booklet assessment and completion challenges by nurses in rural primary healthcare facilities in South Africa. South African Journal of Child Health 14 (3):124–28. doi:10.7196/SAJCH.2020.v14i3.01685.

- Woldesenbet, S. A., D. Jackson, A. F. Goga, S. Crowley, T. Doherty, M. M. Mogashoa, T. H. Dinh, and G. G. Sherman. 2015. Missed opportunities for early infant HIV diagnosis: Results of a national study in South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 68 (3):e26–32. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000460.

- World Health Ogarnization. 2013. Country Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes: Status Report 2011. Accessed April 3, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85621/9789241505987_eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2006. WHO child growth standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2014. CHILDHOOD STUNTING: Challenges and Opportunities. Geneva. Accessed May 13, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/107026/WHO_NMH_NHD_GRS_14.1_eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2016. World Health Statistics 2016- Monitoring Health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. World Health Organization. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- World Health Organization. 2022. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022: Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Food and Agriculture Organization, Jul 6.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2001. The World Health Organization’s Infant Feeding Recommendation. Accessed May 20, 2018. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/infantfeeding_recommendation/en/index.html.

- Wrottesley, S. V., A. Prioreschi, W. Slemming, E. Cohen, C. L. Dennis, and S. A. Norris. 2021, Aug. Maternal perspectives on infant feeding practices in Soweto, South Africa. Public Health Nutrition 24 (12):3602–14. doi:10.1017/S1368980020002451.